- 1Department of Education Management, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- 2Department of Islamic Education, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- 3Department of Madrasah Ibtidaiyah Teacher Education, State Islamic University Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- 4School of Education and Science, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, China

- 5Department of Physical Education, Health, and Recreation, Universitas Muhammadiyah Bangka Belitung, Bangka Belitung, Indonesia

- 6Department of Education Management, Fatoni University, Pattani, Thailand

The consensus on professional teachers is known to be mostly determined by external parties, especially the government. This prompts professionalism to be considered as an indicator for the need of a great performance in educational sector. However, this consensus method of assessment is of a great disadvantage, because it negates the scope of professionalism. This study aims to use students’ perspectives in conceptualizing the characteristics of professional teachers. Fifteen students were selected as subjects from secondary schools in Yogyakarta city, Indonesia. Two interviews were conducted via electronic media (email and zoom), in order to share their experiences about the characteristics of professional teachers in schools. Also, an interpretive phenomenological analysis was used to analyze the data, in order to understand the participants’ point of view. The results showed that interpersonal relationships, pleasant personalities, and teaching skills, represented the main characteristics of great teachers, according to the students perspectives. These results recommended the importance of emphasizing teacher-student interpersonal relationships, in order to achieve sustainable professional programs.

Introduction

Professional teachers are known to play an important role in determining learning outcomes (Osmond-Johnson, 2015; Harisman et al., 2019), and guaranteeing the success of educational programs. The problem of teacher professionalism is considered to be the main issue in educational system (Wardoyo et al., 2017; Rusznyak, 2018). Therefore, the process of encouraging more professionalism has become the primary policy for solving various problems in Indonesia. For example, the Indonesian government formulated Law No. 14 of 2005 on teachers and lecturers, as part of the reform of education. Professional teachers are also described to be competent, by effectively and efficiently carrying out their roles as educators (Dessler, 2011). Moreover, the spearhead of educational qualities is found to depend on the professionalism and performance of teachers (Gunawan et al., 2020). Therefore, professionalism is reportedly a driving force for educational change (Coombe and Stephenson, 2020).

The consensus on teacher professionalism has been debated for more than two decades (Alsalahi, 2015), as it is often considered to be controversial and difficult to understand (Vu, 2016). Reviewing this consensus is found to be very important, in order to understanding the core problems of education (Atkins and Tummons, 2017). In mainstream theory, the concept of teacher professionalism is divided into two, namely managerial and independent (Leung, 2012; Evans, 2014; Dehghan, 2020). Managerial professionalism is based on the characteristics expected from teachers, as determined by competent authorities and officials, e.g., the government or the Ministry of Education. Meanwhile, independent professionalism is the method by which teachers view their practices, knowledge, beliefs, and skills. Also, it deals with the methods by which they critically reflect on these features, based on past experiences as learners, to achieve goals, abilities, and future directions (Leung, 2012). Independent professionalism is also a process that starts from the bottom, as well as personal and self-oriented, while the managerial is top-down, institutional, and externally-oriented (Dehghan, 2020). According to Bourke et al. (2013) and Nairz-Wirth and Feldmann (2019), managerial professionalism was traditionally categorized, which is most common in countries with new prominent public management systems (Bourke et al., 2013). When associated with mainstream theory, the concept of teacher expertness in Indonesia was grouped into managerial professionalism, where the bad impact indicated that educators and students were locked in old inherent routines and practices (Nairz-Wirth and Feldmann, 2019). This is due to the perception of professional teachers being influenced by many factors, such as cultural background (Chandratilake et al., 2012). Most previous studies argued that Indonesian teachers tend to perceive their professions as a non-autonomous type, as they often rejected being viewed autonomously. Moreover, most of them have been found to emphasize on pedagogic competence (Savira and Khoirunnisa, 2018). Teachers also rate their profession more as a civil servant, compared to being an autonomous educator. This situation led them to place their compliance with the government, due to being a priority. The situation is also based on long historical background, regarding the formation of teachers’ identities formed by the government (Savira and Khoirunnisa, 2018). Baskin. (2007), further explained that even though the teaching profession does not have an impact on high economic status, it is observed to have a great social status in Indonesia.

The problems of teacher professionalism are known to be caused by many factors. Evans (2008) and Evans (2011) explained that there is no strong consensus on professionalism, as its measurement is often determined by external parties. Sachs (2016) also criticized that the consensus is dominated by external forces (especially the government), as it is also considered to be a strategy in mobilizing teaching power. This also applies in the aspect of consensus in Indonesia, where it is mostly formed by the Teacher and Lecturer Law No. 14 of 2005 (Republik Indonesia, 2005). The law emphasizes on the qualifications and competencies a teacher should have, according to the level of education in charge. According to Sachs (2016), such consensus is only based on indicators and performance demands. This is found to have a bad impact, due to reducing the deepest meaning of the professionalism concept. Therefore, considering new perspectives to increase the legitimacy and accountability of teacher professionalism is very important (Beauchamp and Thomas, 2009; Sachs, 2016).

This study aims to use students’ perspectives to construct a professional teacher consensus, in order to resolve these problems. According to students, the approach is also important to generate new insights, about the figure of a professional teacher. This perspective also provides students with detailed insights into their sentences, complex analysis from multiple aspects, and specific secondary school contexts (Sweetman et al., 2010). Also, the participants are middle school students from Yogyakarta, a city on Java Island in Indonesia that is known for its culture and pupils (Hasanah et al., 2019). The majority of people in this city have lifestyles that are in line with Javanese culture, regarding religiosity and prioritization of social life (Hasanah and Supardi, 2020).

Literature Review

Professionalism is known to have various meanings in the world of education (Evetts, 2011; Sachs, 2016). It emphasizes on knowledge, experience, autonomy, and responsibility, which leads to certain professions and behaviours, in order to improve the quality of services provided (Cerit, 2012). Professionalism also deals with a commitment to work at high standards (Agezo, 2009). Evetts (2011) defined it as a process of how work is regulated and controlled. However, Hall and McGinity (2015) with Torres and Weiner (2018) emphasized on the shift of people from a job carried out by policyholders, over to that of a top-down professionalism, where management and organizations held more power. Tschannen-Moran (2009) also described teacher professionalism as a set of personal characteristics.

Professional teachers are characterized by various indicators, such as commitment, collaboration, assistance, mutual respect, and participation (Tschannen-Moran, 2009). Other previous studies observed that professionalism was closely related to the qualifications that should be met for the job, and how the society views the teaching profession (Demirkasimoǧlu, 2010). Furthermore, this emphasizes on the practice of lecturers both inside and outside the classroom, as well as their ability to meet student expectations. The teachers’ professionalism is also viewed as a reference, in the efforts to improve teachers’ qualifications and expertise. Hargreaves. (2000) further explained that the development consists of four stages 1) Pre-professionalism: teaching is observed as a simple and technical profession in this process. 2) Autonomous professionalism: the teaching profession emphasizes on the autonomy of teachers at work. 3) Collective professionalism: this is the emergence of a professional learning culture, which leads to the evolution of school collaboration. 4) Post-professionalism: the schools and teaching professions are questioned and redefined in this process.

Lai and Lo (2007) also explained that professionalism contained elements of knowledge and deep understanding, such as learning strategies, responsibilities, and authorities, in order for teachers to make innovations in carrying out their profession. Professionalism was built on competence, collaboration, and leadership. Meanwhile, Timperley and Alton-Lee (2008) explained that it was related to the commitment in taking responsibility for student learning. Citing several previous studies, Cansoy and Parlar (2017) stated that the main indicators of teacher professionalism were courage, autonomy, and responsibility. However, Appel (2020) emphasized on its three most important elements, namely knowledge, autonomy, and responsibilities.

The Importance of Reconstructing the Professional Teacher Consensus

This consensus has always been an interesting topic in educational policy developments, due to greatly determining the quality of education (Alsalahi, 2015; Gunawan et al., 2020). Also, the meaning of professionalism contains complexity, both as work tools and concepts, which are related to social politics and power (Vu, 2016; Amirova, 2020). Moreover, promoting this professionalism was considered as a strategy to overcome various problems in learning practice (Rusznyak, 2018). The mapping against previous studies showed that the consensus on professional teachers was more determined by external authorities, especially the government (Evans, 2011). The problem of professional consensus also depended on the autonomy of teachers and the authority to self-regulate, in order to carry out their duties (Kolsaker, 2008). As explained by Hargreaves and Connor (2018) and Sachs (2016), autonomy and professional self-regulation are the absolute standards of a profession. Therefore, a new perspective on teacher professionalism was needed (Beauchamp and Thomas, 2009; Sachs, 2016). However, this study aims to use student perspectives to construct a professional teacher consensus. The consensus about professional teachers in this study refers to the agreement on the characteristics and indicators of professional teachers that are jointly constructed by a group of people. The consensus generated by the students’ voices can complement as well as criticize the conventions that have been formed previously. This is also very important, due to the perspectives being expected to provide students with detailed views in their sentences, complex analysis from multiple sources, and specific secondary school contexts that shaped experiences about the professional teacher (Sweetman et al., 2010). These perspectives also offer the opportunity to engage secondary school students as co-experts, a data collection procedure used to enhance adolescents’ views, without being contaminated by adult contexts. Moreover, the concept of a great teacher (Benekos, 2016; Holbrook, 2016; Robertson-kraft and Zhang, 2018) is used to maintain neutrality in the data collection process. This concept also makes it easier for the knowledge of students, compared to the use of more normative and professional techniques, as well as class bias (Sachs, 2016).

Methods

Research Design

This study used an interpretive phenomenology approach (Smith et al., 2009; Creswell, 2013), due to its attempt to understand the meaning of a great teacher. Therefore, the themes indicated in the research data were the subjective views of students. The interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) is known as one of the most effective and qualitative analytical method, used for understanding new and emotionally charged topics (Smith and Osborn, 2008; Smith and Osborn, 2015). Science is also very suitable in investigating and explaining students’ experiences, during the conceptualization of professional teachers in their schools. IPA also offers detailed data analysis, in order to understand each case of study according to its merits, before advancing to the general cross-case analytical method (Smith et al., 2009). According to personal experiences, science was suitable for completing this study. This was due to having a deeper understanding of students’ perceptions, regarding the conceptualization of professional teachers.

Participants

The participants were determined using the purposive sampling technique (Springer, 2010; Merriam and Tisdell, 2015; Robson and McCartan, 2016). These samples were also students at the secondary school level in Yogyakarta City, and their selection was carried out through the following criteria, 1) Students should be from one of the high schools in the Yogyakarta city, 2) Students should be willing to participate until the final stage, 3) Student selections should be based on the recommendation of the principal/vice principal, with the consideration of having the ability to answer questions, 4) Consideration about the ability to behave objectively.

The total number of participants were 15 (10 women and 5 men), with age ranging between 16 and 19 years (mean age = 17.2 years). These age groups were within the period of adolescence, which is often a population between 10 and 19 years (WHO, 1999). This was because the students in Indonesia were based on the elementary (7–12 years), as well as junior and senior high (13–15 and 16–18 years) school ages, respectively (Kemendikbud, 2021). However, a student is either 1–2 years early or late in entering formal education, leading to being below or above the general school age range. According to the APA (2016), all names were also written via the code P1-P15, in order to ensure the confidentiality of participants. Also, before the process of data collection, participants received sufficient information about the objectives and background of the study. All fifteen participants were found to express consent, as they were also provided with an option to withdraw from the study at any time. However, the participants were not compensated, due to their voluntary participation.

Research Procedure

The research experts coordinated and collaborated with the school authorities, namely the principal, vice and deputy principals, as well as the staff, in order to select students according to the selection criteria. Furthermore, an interview schedule was prepared, which was in accordance with the APA guidelines (Smith et al., 2009). These interviews were repeatedly conducted through electronic mails and zoom meetings. This indicated that seven students were interviewed only once (via mails), while the others were analyzed twice through mails and zoom meetings. The difference in the number of interviews was based on the expanded data of each participant. After the initial analytical process, the interview data were found to still need further deepening and expansion. After these, the interview guidelines that had been prepared based on the main indicators of professional teachers were used. Moreover, these guidelines were discussed with experts and had received input before being used. After being revised according to the expert’s input, the interview guideline was ready to be used for data collection. Based on this study, the interview guide contained 6 questions as follows,

1. The most enjoyable experience while studying at this school.

2. Positive experiences with teachers while studying at this school.

3. What do you think are the indicators of a great teacher?

4. Which teacher had the most positive influence on your life? Reasons?

5. What makes this teacher different from others?

6. What qualities (teaching ability, personality, attitude, etc.) does the teacher have that others lack?

This open practice was also observed to be carried out flexibly. Meanwhile, the interview through zoom meetings were recorded automatically and the results were transcribed carefully. In addition, the shortest and longest interviews lasted for 18 and 45 min, respectively.

Data Analysis Technique

Data analysis was carried out by the following two stages: The first stage, this was carried out by the open coding of the raw interview data (Robson and McCartan, 2016). According to the open coding process, a deep reading of all data was conducted, resulting in the collection of respondents stories (Smith et al., 2009). Afterwards, this was accompanied by a systematic reading, which used side comments to identify various emerging themes and sub-themes. Moreover, the open coder aims to identify instances, when explaining characteristics of a great teacher. The second stage, based on the use of analytic coding, the connection of various similar codes (and breaking them) was carried out in this process, in order to obtain conclusions from the results of the first stage (Robson and McCartan, 2016). After these, the emergence of themes was observed. These themes were also revised, recombined, and grouped into a more complete description of the student’s experience. At this stage, three themes were found in this study, namely teacher-student interpersonal relationships, great teacher personality, and teaching skills. The teacher-student interpersonal relationships had several codes, such as “my teacher motivates me,” where a participant stated that “When a teacher provides advice, students become motivated…He is a great teacher.” A great teacher’s personality also had several codes such as “my teacher has a pleasant personality,” where a participant stated that “I like certain subjects because the teacher’s nature brings fun material.” Also, these theme tables were created by the first and second experts, via the comparisons of respective notes. Moreover, the tables were further revised at the end of the procedures, by the first expert (Smith et al., 2009).

Results

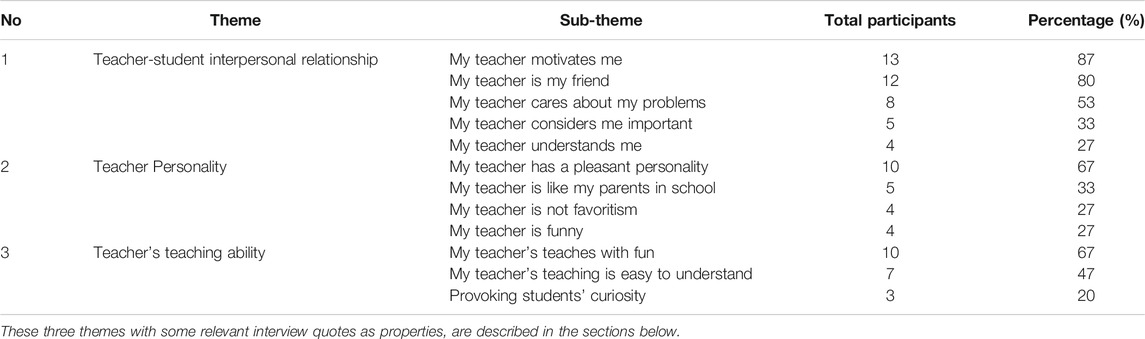

This study was found to have determined that the student perceptions of great teachers varied considerably. The results indicated three important themes, each consisting of several sub-themes. The first theme was the teacher-student interpersonal relationship, which consisted of five sub-themes. Therefore, the data coding are described in Table 1.

Interpersonal Relationships With Students

The first theme that emerged was the great teachers’ interpersonal relationships with students. This relationship was also characterized by the teacher’s ability to act as friends to students, as well as motivate and understand them. Moreover, the teacher made students feel important, and cared about the problems they encountered. Generally, this teacher-student interpersonal relationships was reported by 100% of the respondents (n = 15).

My Teacher Motivated Me

This sub-theme was further stated by 13 students, as the codes that emerged was also observed to vary. Also, this aspect was based on whether teachers were motivated to study hard/rise from adversity, keep working, become a better person, or achieve goals. Moreover, P1 stated that a great teachers inspire students to be motivated in life, and channel their behaviours towards a more positive direction.

When an educator provides advice and education to students in order for them to become motivated and excited, as well as channel their behaviours in a more positive direction, such person is known to be a great teacher (P1, 15–18).

According to another opinion, P1 also explained that a great teacher should also have the ability to motivate students, in order for them to rise from problems.

In that way, Bu (teacher’s name) taught that failing many times is not a problem, as long as I still have the zeal to rise back up and try to be better. Since then, I did not worry anymore during physics lessons, as my motivation to learn had also increased. Also, I was motivated to be a fun person like Bu (teacher’s name) (P1, 53–57).

Furthermore, P3 also stated that their teachers in school were great personalities, with one teacher being mentioned. This teacher was mentioned due to having the ability to motivate many students, in order for them to achieve their goals. Moreover, P3 stated that,

I feel that two of the most patient and wonderful people in the world after my mother were my teachers. They are extraordinary, regarding their motivation of students towards the achievement of their dreams (P3, 15–17).

Many other students also shared similar views, for example,

“Sir [teacher’s name] and Mrs. [teacher’s name], taught me how to work, as well as provided motivation to continue working and remain productive in the midst of other activities” (P1, 8–10). “I learned a lot from him, especially how to always smile, enjoy, and be enthusiastic, even though things hurt within” (P3, 39–41).

My teacher is My Best Friend

This sub-theme was mostly expressed by respondents, as 80% of them (n = 12) stated that a great teacher should act as a friend. This enabled the teachers to be communicated with, want to listen to their students, and joke around. P3 stated that,

A great teacher should be friendly with students, as well as not acting harshly and pressurizing them (P3, 17–18).

With a view to strengthen P3’s opinion, P9’s report was about being very happy to be at his present school, due to being in chemistry with the great teachers.

Chemistry here is in the form of teacher friendliness towards students, without any reduction of respect. I think when students feel comfortable as friends with the teachers, they tend to open up on what is not understood or have other anxiety that requires the role of the teacher (P9, 37–42).

Similar experiences were also reported by other students. Teachers that were willing to listen in order to be confide in, had provided positive experiences for P6 at school.

My positive experiences with teachers are actually much, one of which is often confiding in them regarding lessons and activities that are related to school (P6, 10–11). At that time, Bu [teacher’s name] treated us to a meal while chatting about many things. As it turned out, I, Bu [teacher’s name], and my seniors liked the author of the same novel. At that time, we shared stories and exchanged titles for good novels (P1, 29–32).

My Teacher Cares About My Problems

More than half of the respondents (n = 8) reported that besides playing a role during learning in the classroom, great teachers also cared about the problems encountered by students. Based on their beliefs, the students’ academical success was also related to their lives outside the school. Therefore, the teacher also played a role in understanding and assisting the problems encountered by students outside the classroom. P6 also had an unforgettable experience at school, due to the care and solution received for problems encountered.

The influential teacher in my life is Mrs. [teacher’s name], a teacher that cared about my problems when I wanted to leave school, due to the environment not meeting my expectations. Even when I started feeling uncomfortable, Mrs. [teacher’s name] kept building a mindset for me, in order not to be caught up in the problem. She also helped in dealing with all problems I encountered (P6, 14–18).

In line with P6, P5 also stated that the teacher’s caring experience was felt during a dispute with classmates. Moreover, P5 reported that,

I once had a problem with my classmates, as I felt ignored when I hang out with them. By being opened to my teacher, I explained al I felt. My teacher guided and directed me by willing to help follow up on problems I experienced (P10, 11–15).

Other students also shared similar experiences (P5 and P9 for example) and reported that,

Bu [teacher’s name] listens to all the difficulties we encounter, and always supports us. The teacher continued to provide information and helped us when there were problems or difficulties that was encountered (94–96). She also listens and provides solutions when my friends and I get into trouble (P9, 97–101).

My Teacher Thinks I am important

About One-third of the respondents (n = 5) reported that a great teacher assumes that students are important. P14 shared an experience about trying to quit lessons at school, even though the despair was not only related to education (e.g., social and family matters). This situation was caused by some factors, including family frustrations and economic conditions. In the interview, P14 explained that,

Actually, it started with a problem I encountered outside of school. Finally, I was unable to focus on the lessons at school and was no longer accepted by my friends as before. My life is ruined. (P14, 23–26).

According to the interview with P14, the academic journey at school did not meet the initial expectations. Problems such as laziness, absence, incomplete assignment, and forgetting school schedules were also encountered. Moreover, P14 reported that,

Luckily, I met my homeroom teacher in high school. Even though at first my teacher also immediately saw me as a lazy student, this view changed the next time I had the opportunity to talk about my condition. One motivation that kept me thinking positively was that “no matter what state you are in, you still have a future. Some of his motivations made me feel that I was an important part of learning in the classroom” (P14, 32–38).

The story of P14 was also experienced by several other students, although it was not quite the same. For example, when asked about a great teacher, P3 stated that,

“Bu [teacher’s name] never underestimated all her students, even though they were stupid” (P3, 8–12).

My Teacher Understands Me

This was observed to be very important, as it was mentioned by more than a quarter of students (n = 4). The sub-theme was based on teachers understanding students’ different abilities, conditions, and emotional feelings.

The teachers that build good chemistry with the students, tends to understand them, which in turn results in a sense of mutual understanding when the closeness is well established (P9, 42–46).

Several other students also reported similar experiences, as P4, P5, and P12 stated that,

Teachers that understood their students tends to adapt to each of them, because of their different abilities (P4, 3–4). The teacher understands my friends and I. Also, the way he treats us (P5, 22) results in a case of mutual understanding, while getting him involved in the learning process (P12).

Teacher Personality

Teachers’ personality was the second theme of the student responses. This theme consisted of four sub-themes, namely, 1) my teacher has a pleasant personality, 2) my teacher is like a parent at school, 3) my teacher is not favoritism, 4) My teacher is funny. Generally, the teacher’s personality themes were expressed by 13 respondents.

My Teacher has a Pleasant Personality

This sub-theme was mostly mentioned by the students (n = 10). Some of the relevant codes, for example, were relaxed, friendly, patient, fun, cheerful, and never angry. According to P1, personality was an indicator of a great teacher.

Bu [teacher’s name] was relaxed, friendly, patient, understanding, and made virtual meeting light and comfortable. The class atmosphere was often very friendly without chaos. The virtual class felt relaxed, yet still systematic (P1, 69–72).

The same thing was shared by P4 through interviews,

She is always a cheerful person when starting lessons, therefore, my friends and I were more excited to learn. When some do not carry out their homework, she does not get angry, yet provided advice and opportunities to students. She often reminded us to carry out our homework (P4, 18–22).

A similar statement was also explained by several other students. According to them, a teacher was pleasant, patient, and friendly, helped in increasing their interest in certain subjects.

Besides being interested in a certain subject because they are really interesting, the nature of the teacher was mostly the reason students made it their favourite. (P3, 19–21). I am most happy with Sir [teacher’s name] lessons, because he was the most patient teacher, during my studies from elementary to high school (P5, 2–3). The personality of Bu [teacher’s name] was humble towards her students. She always says hello when she meets them and does embrace all (P10, 32–34).

My Teacher is Like a Parent at School

This sub-theme was mentioned by one-third of the respondents (n = 5). As reported by several respondents, teachers in high schools were required to have the ability to act like their parents at home.

He is very responsible for me, and like a parent at school. He was a strict person, yet also joked a lot (P4, 16–18).

A similar statement was also explained by P9 as follows,

The most important thing is that a great teacher should build chemistry with students, and also consider acting as their parents in schools (P9, 29–31).

My Teacher is Not Favoritism

This sub-theme was found to be mentioned by 4 students only. Being impartial, fair, and not discriminating against students were codes that often occurred. P8 and P10 stated that,

Great teachers are fair in anything. When a student does not understand, it should be explained again. However, when there is a smarter student, favoritism should not occur (P8, 5–6). Great teachers do not differentiate between their students, because all of them have abilities in their respective fields (P10, 7–9).

My Teacher is Funny

According to the students, being funny was also an indicator of a great teacher. The teacher with a funny and humorous personality was also mentioned by 4 students. The trait was also an ice breaker for students, during learning. This indicated that the learning process should not be rigid, stretchy, too serious, and tedious. During the interview, P3 stated that,

“The teacher I like the most is Bu [teacher’s name], because she is a funny person. In the middle of the delivery of subject matter, she always inserts certain jokes, which allows the class comes alive again. Sometimes, some friends were often sleepy because of studying during the day, and after hearing her jokes, they became awake again” (P9). The teacher here is very entertaining with little jokes in class, especially when it was a stressful day, in order not to make us sleepy. Even though sometimes students act too far, the teacher does not act tough (P3, 34–36).

Teacher Teaching Ability

The teachers’ teaching ability was a theme also mentioned by all respondents (n = 15). Also, three sub-themes were identified in this themes, namely 1) my teacher teaches with fun, 2) my teacher’s teaching is easy to understand, 3) my teacher’s teaching provokes students’ curiosity.

My Teacher Teaches With Fun

This sub-theme was found to be mentioned by 10 respondents. Codes were also found to be formed in this aspect, such as the funny teacher, atmosphere is enjoyable, students feel comfortable, learning while playing, and teaching is not boring. P1 further stated that,

Bu [teacher’s name] built pleasant teaching and learning atmosphere, which provoked me and my friends to actively ask, answer, and discuss. Based on this condition, my friends and I understood the basic concepts of the learning material (P1, 63–66).

The same thing was stated by P2. According to this respondent, history lessons were difficult, due to being delivered by a pleasant teacher, where the learning process eventually turned into a funny atmosphere.

Actually, history is a complicated subject, yet it was fun in the 11th-grade (P2, 10–12).

Statements describing the pleasant experiences of the teachers were also delivered by P8, P10, and P11. For example, some of their responses were,

“The teaching method should be able to make students comfortable with the subject being taught” (P8, 6–7). “During class, the teacher was also relaxed, which made the learning atmosphere enjoyable” (P2, 102–103). “The atmosphere was enjoyable, with a teaching method that was not rigid, stressful, and boring” (P10, 30–32). “The teacher likes to provide group/individual quizzes while playing, therefore, making it easier for lessons to be accepted” (P11, 28–30).

My Teacher’s Teaching is Easy to Understand

Some of the codes that appeared in this sub-theme were understanding the material presented, the lesson is easy to understand, the students understood, it is very easy to accept, and the learning samples were absorbed by students. P4 stated that,

When the teacher explained the lesson, it was easy to understand. The learning methods used are also different, prompting students not to get bored quickly (P4, 10–11)

P11 also reported that the teacher was one of the best, because learning processes were easily accepted.

The way Bu [teacher’s name] teaches is very easy to accept. Even though the subject taught is chemistry, which was difficult, Bu [teacher’s name] always made it interesting, by providing sufficient materials in class (P11, 21–24).

A similar experience was also reported by several other students (P1, P5, and P7), for example,

The teacher’s teachings are practical and easy to understand” (P7, 29). “His teaching ability is very good and made all students anticipate the class. This ensured the effective absorption of the material provided (P11, 34–35).

Provoking Students’ Curiosity

This sub-theme was mentioned by 20% of the respondents (n = 3). The interview with P1 is described as follows,

During the quiz session, Bu [teacher’s name] often provoked me and my friends with questions. The fact that I wanted to know the reasons for such recurrence, sparked my curiosity and desire to explore more things (P1, 72–74).

According to P1, the quizzes that were often made by the teacher resulted in more curiosity, which also prompted the interest to explore more about school lessons. Similar experiences were also reported by several other students (P7 and P13),

When teaching, Sir [teacher’s name] makes me and my friends feel challenged to continue learning, because the class that was being conducted really made us curious (P7, 12–16). Bu [teacher’s name] has a funny and challenging way of teaching. Every time I finish the lesson I am still curious about the continuation of tomorrow’s material (P13, 24–26).

Discussion and Conclusion

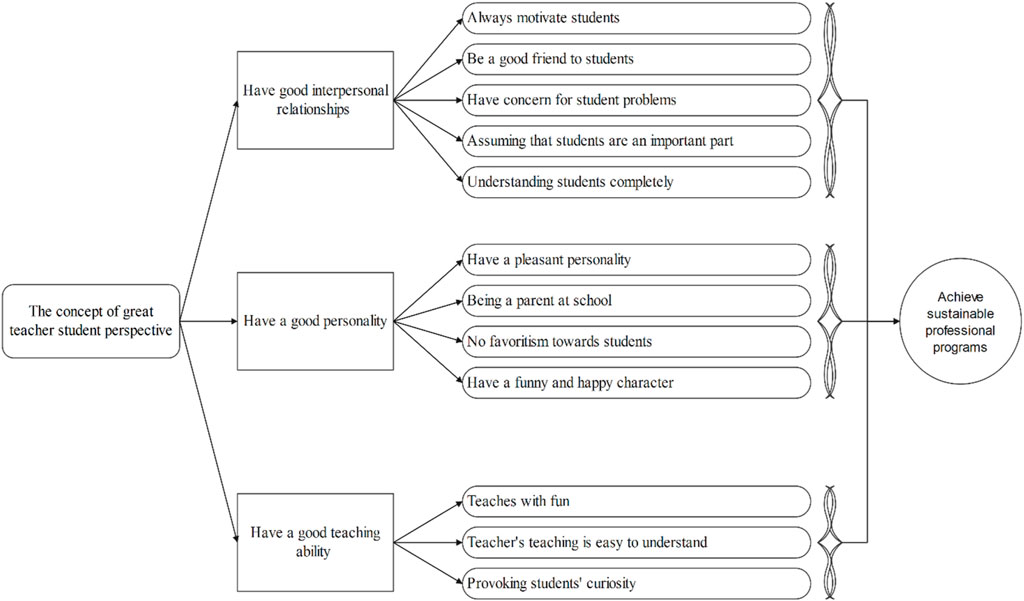

This study aims to explore students’ perceptions of professional teachers, according to their experiences in school. The concept of a great teacher according to the students’ perspective can be seen in Figure 1. Based on this investigation, three main themes, namely teachers’ interpersonal relationship, personality, and teaching ability, with twelve sub-themes were identified.

Interpersonal Relationships With Students

The ability to establish interpersonal relationships with students was a priority for adolescents, in order to perceive a great teacher. This interpersonal relationship was characterized by the ability to motivate, act as friends, consider students important and care about their problems, and create conditions where learning processes are easily understood. These sub-themes showed that for students, the characteristics of great teachers depended on the dynamics of their mental development. Even though great teachers were not sufficiently shown in the form of teaching expertise in the classroom, the ability to immerse themselves in the youthful world was very much important. Besides dealing with subject matters at school, they often contend with adolescents’ development, with all its dynamics.

These results corroborate several previous studies, which highlighted the importance of interpersonal relationships between teachers and students. Several previous studies suggested that teachers that had the ability to build good relationships with students, contributed to students’ motivation (Hamre and Pianta, 2005; Buyse et al., 2008; Koca, 2016), self-esteem (Spilt et al., 2011), daily welfare level (Seligman, 2012), mental enhancement (Wubbels and Brekelmans, 2005), participation (Thijs and Koomen, 2008), and achievement in school (Roorda et al., 2011). One of the sub-themes in this result (the teacher’s ability to show a caring attitude towards students), also had a profound impact on students’ psychology. There were also significant effects on the welfare of those that were cared for by teachers (Lavy and Naama-Ghanayim, 2020). When students know that others care about their conditions and needs, their self-esteem increases, while having the impression that their presence was important to others. Also, when students know that they have a positive relationship with their teachers, their attachment to school tends to become stronger (Martin and Collie, 2018). The method teacher’s use in building interpersonal relationships with students is also very influential on emotions (Mainhard et al., 2018). Therefore, these results also supported the previous thesis, which stated that teachers functioned as meaningful adult figures for adolescent life, in order to make students feel valued (Lavy and Naama-Ghanayim, 2020).

A basic component of this interpersonal relationships was the students’ perception that teachers cared and supported them. Caring is known to be a core element in creating this type of relationship (Orkibi and Tuaf, 2017). Caring teachers showed affection for students, listened to their opinions, understood, motivated, and made learning interesting for them (Noddings, 2013). Teachers that cared about students were more responsive to their feelings, which in turn led to protection, safety, and support (Mayseless, 2015). The need for attention was also very important for adolescents, due to this age being related to the school hierarchy (Karna et al., 2010). Therefore, students need a sense of security to step out of their “comfort zone”, into an environment full of uncertainty (Mayseless, 2015). Several empirical evidence also proved that students that felt valued and cared for by their teachers in school, were able to achieve better cognitive, affective, and psychomotor results (Kunter et al., 2013; McGrath, 2015; Vandenbroucke et al., 2018). Therefore, valuing and caring for students was the teacher’s main role in the learning process. This also helped to create development and happiness (Noddings, 2012). The need for attention was also a basic human emotional desire, which supported individual comfort and development (Lavy and Naama-Ghanayim, 2020).

Besides being good for students, the ability to build interpersonal relationships was also important for the professional development of the teachers. Furthermore, the great teachers that built positive interpersonal relationships with students, helped in improving welfare, and vice versa (Butler, 2012; Klassen et al., 2012). Moreover, this interpersonal relationship played an important role in increasing emotional experiences (Hagenauer et al., 2015), as well as involvement and motivation in the classroom (Henry and Thorsen, 2018). Also, quality interpersonal relationships were characterized by closeness, warmth, low conflict, respect, and low levels of dependence (Hummer et al., 2010; Claessens et al., 2016; de Hong et al., 2018). When they are more connected with their students, teachers were also observed to teach with enthusiasm and fun (Aldrup et al., 2018). Therefore, building good interpersonal relationships with students was the main identity of professionalism (Prøitz, 2015).

The Teacher has a Pleasant Personality

The second result also stated that a pleasant personality was an important indicator of a great teacher. Teachers with a pleasant personality were enthusiastic, patient, friendly, and calm. Also, the presence of these teachers were often anticipated by students. This results also confirmed the studies of Miron and Mevorach (2014)and Benekos (2016) which stated that when students were told to describe a good teacher, they discussed more about the qualities that reflected the educator’s personality (enthusiastic, easy to contact, humble, pleasant, funny, inspiring, and energetic) than the pedagogical skills.

Several studies also showed that teachers’ personality contributed 27% to student learning motivation (Jahangiri, 2016). Personality is known as the unique psychological qualities that influences individual behaviours, thoughts, and feelings (Roberts and Jackson, 2008). It also plays a role in increasing the effectiveness of teachers’ work (Holmes et al., 2015). A good teacher’s personality towards students was more important than teaching knowledge and skills. This personalities towards students includes commitment, responsibility, and enthusiasm, which are used in developing the teaching profession at the core of teachers’ professionalism (Capen, 2017).

Teacher Teaching Skills

According to respondents, great teaching skills were described by teachers that taught in a funny and easy-to-understand manner. Moreover, this was observed to increase the curiosity of the students. When told to confirm the description of the great teacher’s teaching skills, students also emphasized on the method being used to convey the materials (in a funny way).

Teachers that taught with fun were the sub-themes most mentioned by students. This was due to the emotions they had, which also affected the students. These teachers had an impact on students, due to the provision of an enjoyable and comfortable learning process (Becker et al., 2014). The delivery method in class also had an impact on students’ positive emotions, such as the feelings of enjoyment and pride (Goetz et al., 2013). Moreover, teacher teaching skills improved students’ control and academical achievements (Muntaner-Mas et al., 2017). The teachers that taught with enthusiasm and fun also improved motivation and student learning outcomes (Kunter et al., 2013; Keller et al., 2014).

There is No Code on Teacher as a Role Model and Teacher Professional Competence

Furthermore, there was no code about the great teachers being a role model. This result was surprising, as none of the students perceived that a great teacher was an example in their life. Moreover, this result also contradicted most of the previous studies, which stated that one of the indicators of professionalism was a teacher being a role model to students (Hadisaputra et al., 2018; Jimung, 2019; Ramdan and Fauziah, 2019; Suyatno et al., 2019). Ramdan and Fauziah. (2019), for example, stated that a teacher should have the ability to be a role model for students in attitude and personality, honesty, discipline, responsibility, and religion. According to the Regulation of the Indonesia Minister of National Education Number 16 of 2007, this indicator was also observed as the main characteristic of teacher personality competence. This regulation was concerned with Academic Qualification Standards and Teacher Competencies, which stated that educators should also be a role model for students and the society.

The next surprising result was the absence of codes, which also pointed to the importance of teacher professional competence. According to classroom learning, students focused more on the methods used in presenting materials (funny, friendly, simple, or easy-to-understand manners), which also represented the pedagogical competence. Meanwhile, the teachers’ mastery of the material being taught was included in the professional competence, as stated in the Regulation of the Minister of National Education of Indonesia Number 16 of 2007. This regulation was also concerned with Academic Qualification Standards and Teacher Competencies, which explained that professional competence was all about mastering the material, structure, concepts, and scientific mindset that supported the subjects being taught. Therefore, the results of this study did not support generalizations, especially the Regulation of the Minister of National Education of Indonesia Number 16 of 2007. This difference was probably due to the emotional condition of adolescent students, where the adequacy of meeting emotional needs was prominently felt, compared to the mastery of subject matter in school. Moreover, this consensus was observed to be in line with previous studies, which emphasized more on commitment to work (Timperley and Alton-Lee, 2008; Tschannen-Moran, 2009), ability to innovate in learning (Lai and Lo, 2007), and responsibilities in carrying out duties (Appel, 2020). Therefore, a good teacher’s personality seemed more meaningful to students than the mastery of materials presented to them. Also, the teachers’ personalities, such as commitment, responsibility, and enthusiasm, were at the core of professionalism (Capen, 2017). However, these results need to be the object of future studies, in order to identify more valid evidence.

The results indicated that students’ perspectives on a great teacher relied on the educator’s ability to build interpersonal relationships, as well as possess pleasant personalities and good teaching skills. This embodied the qualities that should be possessed by a professional teacher (Kim et al., 2021). Therefore, implications for the professional development of teachers was futuristically necessary and essential. These were in line with Kuhlee and Winch (2017), which indicated the importance of teacher professionalism not being interpreted as a universal value. This was due to the variations of professionalism notions in different contexts.

Based on teacher professional development in Indonesia, the results became an additional “homework”, which was quite complicated for teachers and the Ministry of Education. This was because previous studies explained that teaching was not an autonomous profession in Indonesia, due to being prioritized to comply with the government (Savira and Khoirunnisa, 2018). Based on this perception, teachers were less flexible in developing their professionalism features, especially accommodating students’ expectations regarding quality. This was because teachers prioritize top-down demands from the authorities, leading to a bad impact due to being locked within ingrained routines (Nairz-Wirth and Feldmann, 2019).

Practical Implications

Several practical implications were also applied as a follow-up to this study. Firstly, the main objective of the study was to resolve the issues of consensus, which was only based on external perspectives, especially those made by the government. Furthermore, future consensus on professional teachers needs to include student perspectives. As described by Aldrup et al. (2018), considering the voices of students was a promising solution to reducing various problems in education. Also, the second implication was the importance of emphasizing interpersonal relationships in teachers’ educational programs (both in the implementation of undergraduate and science education in the faculties of teacher training, as well as teacher professional education/PPG) and professional development services (Claessens et al., 2016). Moreover, undergraduate education providers also need to provide adequate interpersonal relationship methods, due to their experiences playing a key role in developing professionalism (Chang and Park, 2019). Finally, the description of a great teacher that represented the voices of students, should be elaborated in compiling competency indicators. Therefore, professional teacher consensus was more legitimate in the perspective of students.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Universitas Ahmad Dahlan. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

SS, WW, AP, DF, and AS: Conceptualization; Methodology; Writing Original Draft; Data Curation; Formal analysis; Project administration. ZN: Conceptualization; Writing Review and Editing.

Funding

Research funding supported by Universitas Ahmad Dahlan, Indonesia, Project Number: PD-360/SP3/LPPM-UAD/V/2021.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ahmad Dahlan University, for funding this research, as well as the principal, teachers, and students that helped during the data collection.

References

Agezo, C. K. (2009). School Reforms in Ghana: A challenge to Teacher Quality and Professionalism. IFE PsychologIA: Int. J. 17 (2), 40–64. doi:10.4314/ifep.v17i2.45302

Aldrup, K., Klusmann, U., Lüdtke, O., Göllner, R., and Trautwein, U. (2018). Student Misbehavior and Teacher Well-Being: Testing the Mediating Role of the Teacher-Student Relationship. Learn. Instruction 58 (June), 126–136. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.05.006

Alsalahi, S. M. (2015). Stages of Teacher's Professionalism: How Are English Language Teachers Engaged? Tpls 5 (4), 671–678. doi:10.17507/tpls.0504.01

Amirova, B. (2020). Study of NIS Teachers' Perceptions of Teacher Professionalism in Kazakhstan. ije 8 (4), 7–23. doi:10.22492/ije.8.4.01

APA (2016). Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major: Version 2.0. Am. Psychol. 71 (2), 102–111. doi:10.1037/a0037562

Appel, M. (2020). Performativity and the Demise of the Teaching Profession: the Need for Rebalancing in Australia. Asia-Pacific J. Teach. Edu. 48 (3), 301–315. doi:10.1080/1359866X.2019.1644611

Atkins, L., and Tummons, J. (2017). Professionalism in Vocational Education: International Perspectives. Res. Post-Compuls.. 22 (3), 355–369. doi:10.1080/13596748.2017.1358517

Baskin, B. (2007). “Vigor, Dedicafion, and Absorpfion: Work Engagement Among Secondary English Teachers in Indonesia,” in annual AARE Conference, Fremantle, Perth, November 25-29, 2007.

Beauchamp, C., and Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding Teacher Identity: An Overview of Issues in the Literature and Implications for Teacher Education. Cambridge J. Edu. 39 (2), 175–189. doi:10.1080/03057640902902252

Becker, E. S., Goetz, T., Morger, V., and Ranellucci, J. (2014). The Importance of Teachers' Emotions and Instructional Behavior for Their Students' Emotions - an Experience Sampling Analysis. Teach. Teach. Edu. 43, 15–26. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2014.05.002

Benekos, P. J. (2016). How to Be a Good Teacher: Passion, Person, and Pedagogy. J. Criminal Justice Edu. 27 (2), 225–237. doi:10.1080/10511253.2015.1128703

Bourke, T., Lidstone, J., and Ryan, M. (2013). Teachers Performing Professionalism: A Foucauldian Archaeology. Sage Open 3 (4), 2158244013511261. doi:10.1177/2158244013511261

Butler, R. (2012). Striving to Connect: Extending an Achievement Goal Approach to Teacher Motivation to Include Relational Goals for Teaching. J. Educ. Psychol. 104 (3), 726–742. doi:10.1037/a0028613

Buyse, E., Verschueren, K., Doumen, S., Van Damme, J., and Maes, F. (2008). Classroom Problem Behavior and Teacher-Child Relationships in Kindergarten: The Moderating Role of Classroom Climate. J. Sch. Psychol. 46 (4), 367–391. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2007.06.009

Cansoy, R., and Parlar, H. (2017). Examining the Relationships between the Level of Schools for Being Professional Learning Communities and Teacher Professionalism. Malaysian Online J. Educ. Sci. 5 (3), 13–27.

Capen, S. M. (2017). The Context of Teacher Professionalism: A Case Study of Teacher Perceptions of Professionalism at the University Laboratory School. Honolulu, USA: University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

Cerit, Y. (2012). Educational Administration: Theory and Practice Okulun Bürokratik Yapısı Ile Sınıf Öğretmenlerinin Profesyonel Davranışları Arasındaki Ilişki. Kuram ve Uygulamada Eğitim Yönetimi 18 (4), 497–521.

Chandratilake, M., Mcaleer, S., and Gibson, J. (2012). Cultural Similarities and Differences in Medical Professionalism: A Multi-Region Study. Med. Educ. 46 (3), 257–266. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04153.x

Chang, J., and Park, J. (2019). Developing Teacher Professionalism for Teaching Socio-Scientific Issues: What and How Should Teachers Learn? Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 15, 423–431. doi:10.1007/s11422-019-09955-6

Claessens, L., van Tartwijk, J., Pennings, H., van der Want, A., Verloop, N., den Brok, P., et al. (2016). Beginning and Experienced Secondary School Teachers' Self- and Student Schema in Positive and Problematic Teacher-Student Relationships. Teach. Teach. Edu. 55, 88–99. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2015.12.006

Coombe, C., and Stephenson, L. (2020). Professionalizing Your English Language Teaching. Basingstoke, UK: Springer Nature.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

de Jong, E. M., Koomen, H. M., Jellesma, F. C., and Roorda, D. L. (2018). Teacher and Child Perceptions of Relationship Quality and Ethnic Minority Children's Behavioral Adjustment in Upper Elementary School: A Cross-Lagged Approach. J. Sch. Psychol. 70, 27–43. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2018.06.003

Dehghan, F. (2020). Teachers' Perceptions of Professionalism: a Top-Down or a Bottom-Up Decision-Making Process? Prof. Dev. Edu. 46 (1), 1–10. doi:10.1080/19415257.2020.1725597

Demirkasımoğlu, N. (2010). Defining “Teacher Professionalism” from Different Perspectives. Proced. - Soc. Behav. Sci. 9, 2047–2051. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.12.444

Evans, L. (2014). Leadership for Professional Development and Learning: Enhancing Our Understanding of How Teachers Develop. Cambridge J. Educ. 44 (2), 179–198. doi:10.1080/0305764x.2013.860083

Evans, L. (2008). Professionalism, Professionality and the Development of Education Professionals. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 56 (1), 20–38. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8527.2007.00392.x

Evans, L. (2011). The 'shape' of Teacher Professionalism in England: Professional Standards, Performance Management, Professional Development and the Changes Proposed in the 2010 White Paper. Br. Educ. Res. J. 37 (5), 851–870. doi:10.1080/01411926.2011.607231

Evetts, J. (2011). A New Professionalism? Challenges and Opportunities. Curr. Sociol. 59 (4), 406–422. doi:10.1177/0011392111402585

Goetz, T., Lüdtke, O., Nett, U. E., Keller, M. M., and Lipnevich, A. A. (2013). Characteristics of Teaching and Students' Emotions in the Classroom: Investigating Differences across Domains. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 38 (4), 383–394. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2013.08.001

Gunawan, I., Pratiwi, F. D., Setya, N. W. N., Putri, A. F., Sukawati, N. N., Santoso, F. B., et al. (2020). “Measurement of Vocational High School Teachers Professionalism,” in 1st International Conference on Information Technology and Education (ICITE 2020), Malang, Indonesia, November 7, 2020, 67–72.

Hadisaputra, S., Hakim, A., MuntariGito, H., and Muhlis, M. (2018). Pelatihan Peningkatan Keterampilan Guru IPA Sebagai Role Model Abad 21 Dalam Pembelajaran IPA. Jurnal Pendidikan Dan Pengabdian Masyarakat 1 (2), 274–277.

Hagenauer, G., Hascher, T., and Volet, S. E. (2015). Teacher Emotions in the Classroom: Associations with Students' Engagement, Classroom Discipline and the Interpersonal Teacher-Student Relationship. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 30 (4), 385–403. doi:10.1007/s10212-015-0250-0

Hall, D., and McGinity, R. (2015). Conceptualizing Teacher Professional Identity in Neoliberal Times: Resistance, Compliance and Reform. Edu. Pol. Anal. Arch. 23 (8). doi:10.14507/epaa.v23.2092

Hamre, B. K., and Pianta, R. C. (2005). Can Instructional and Emotional Support in the First-Grade Classroom Make a Difference for Children at Risk of School Failure? Child. Dev. 76 (5), 949–967. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00889.x

Hargreaves, A. (2000). Four Ages of Professionalism and Professional Learning. Teach. Teach. 6 (2), 151–182. doi:10.1080/713698714

Hargreaves, A., and O’Connor, M. T. (2018). Solidarity with Solidity: The Case for Collaborative Professionalism. Phi Delta Kappan 100, 20–24. doi:10.1177/0031721718797116

Harisman, Y., Kusumah, Y. S., and Kusnandi, K. (2019). How Teacher Professionalism Influences Student Behaviour in Mathematical Problem-Solving Process. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1188 (1), 012080. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1188/1/012080

Hasanah, E., and Supardi, S. (2020). The Meaning of Javanese Adolescents’ Involvement in Youth Gangs during the Discoveries of Youth Identity: A Phenomenological Study. Qual. Rep. 25 (10), 3602–3626. doi:10.46743/2160-3715/2020.4409

Hasanah, E., Zamroni, Z., Dardiri, A., and Supardi, S. (2019). Indonesian Adolescents Experience of Parenting Processes that Positively Impacted Youth Identity. Qual. Rep. 24 (3), 499–512. doi:10.46743/2160-3715/2019.3825

Henry, A., and Thorsen, C. (2018). Teacher-Student Relationships and L2 Motivation. Mod. Lang. J. 102 (1), 218–241. doi:10.1111/modl.12446

Holbrook, M. B. (2016). Reflections on Jazz Training and Marketing Education: What Makes a Great Teacher? Marketing Theor. 16, 429–444. doi:10.1177/1470593116652672

Holmes, C., Kirwan, J. R., Bova, M., and Belcher, T. (2015). An Investigation of Personality Traits in Relation to Job Performance of Online Instructors. Online J. Distance Learn. Adm. 18 (1), 1–9.

Hummer, D., Sims, B., Wooditch, A., and Salley, K. S. (2010). Considerations for Faculty Preparing to Develop and Teach Online Criminal justice Courses at Traditional Institutions of Higher Learning. J. Criminal Justice Edu. 21 (3), 285–310. doi:10.1080/10511253.2010.488108

Jahangiri, M. (2016). Teacher’ Personality and Students’ Learning Motivation. Acad. J. Psychol. Stud. 5 (3), 208–214.

Jimung, M. (2019). Pengaruh guru sebagai role model terhadap motivasi penerapan PHBS siswa di SMP Freater Parepare. Jurnal Kesehatan Lentera ACITYA 6 (2), 40–45.

Kärnä, A., Voeten, M., Poskiparta, E., and Salmivalli, C. (2010). Vulnerable Children in Varying Classroom Contexts: Bystanders' Behaviors Moderate the Effects of Risk Factors on Victimization. Merrill-Palmer Q. 56, 261–282. doi:10.1353/mpq.0.0052

Keller, M. M., Goetz, T., Becker, E. S., Morger, V., and Hensley, L. (2014). Feeling and Showing: A New Conceptualization of Dispositional Teacher Enthusiasm and its Relation to Students' Interest. Learn. Instruction 33, 29–38. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.03.001

Kemendikbud (2021). Peraturan Menteri Pendidikan Dan Kebudayaan Republik indonesia Nomor 1 Tahun 2021 Tentang Penerimaan Peserta Didik Baru Pada Taman Kanak-Kanak, Sekolah Dasar, Sekolah Menengah Pertama, Sekolah Menengah Atas, Dan Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan. Available at: http://dindikptk.net/permendikbud/PERMENDIKBUD_1_2021_PPDB.pdf.

Kim, L. E., Oxley, L., and Asbury, K. (2021). What Makes a Great Teacher during a Pandemic? J. Edu. Teach. 47 (1), 1–3. doi:10.1080/02607476.2021.1988826

Klassen, R. M., Perry, N. E., and Frenzel, A. C. (2012). Teachers' Relatedness with Students: An Underemphasized Component of Teachers' Basic Psychological Needs. J. Educ. Psychol. 104 (1), 150–165. doi:10.1037/a0026253

Koca, F. (2016). Motivation to Learn and Teacher-Student Relationship. J. Int. Edu. Leadersh. 6 (2), 1–20.

Kolsaker, A. (2008). Academic Professionalism in the Managerialist Era: A Study of English Universities. Stud. Higher Edu. 33 (5), 513–525. doi:10.1080/03075070802372885

Kuhlee, D., and Winch, C. (2017). “Teachers’ Knowledge in England and Germany: the Conceptual Background,” in Knowledge and the Study of Education: An International Exploration (United Kingdom: Symposium Books), 231–254.

Kunter, M., Klusmann, U., Baumert, J., Richter, D., Voss, T., and Hachfeld, A. (2013). Professional Competence of Teachers: Effects on Instructional Quality and Student Development. J. Educ. Psychol. 105 (3), 805–820. doi:10.1037/a0032583

Lai, M., and Lo, L. N. K. (2007). Teacher Professionalism in Educational Reform: The Experiences of Hong Kong and Shanghai. Compare: A J. Comp. Int. Edu. 37 (1), 53–68. doi:10.1080/03057920601061786

Lavy, S., and Naama-Ghanayim, E. (2020). Why Care about Caring? Linking Teachers' Caring and Sense of Meaning at Work with Students' Self-Esteem, Well-Being, and School Engagement. Teach. Teach. Edu. 91 (May), 103046. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2020.103046

Leung, C. (2012). “Second/additional Language Teacher Professionalism: What Is it,” in Symposium 2012 (Sweden: Stockholms Universitet), 11–27.

Mainhard, T., Oudman, S., Hornstra, L., Bosker, R. J., and Goetz, T. (2018). Student Emotions in Class: The Relative Importance of Teachers and Their Interpersonal Relations with Students. Learn. Instruction 53, 109–119. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2017.07.011

Martin, A. J., and Collie, R. J. (2018). Teacher–student Relationships and Students’ Engagement in High School: Does the Number of Negative and Positive Relationships with Teachers Matter? J. Educ. Psychol., 1–49. doi:10.1037/edu0000317.1

Mayseless, O. (2015). The Caring Motivation: An Integrated Theory. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Merriam, S. B., and Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Miron, M., and Mevorach, M. (2014). The “Good Professor” as Perceived by Experienced Teachers Who Are Graduate Students. J. Edu. Train. Stud. 2 (3), 82–87. doi:10.11114/jets.v2i3.411

Muntaner-Mas, A., Vidal-Conti, J., Sesé, A., and Palou, P. (2017). Teaching Skills, Students' Emotions, Perceived Control and Academic Achievement in university Students: A SEM Approach. Teach. Teach. Edu. 67, 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.05.013

Nairz-Wirth, E., and Feldmann, K. (2019). Teacher Professionalism in a Double Field Structure. Br. J. Sociol. Edu. 40 (6), 795–808. doi:10.1080/01425692.2019.1597681

Noddings, N. (2013). Caring: A Relational Approach to Ethics and Moral Education. Berkeley: Univ of California Press.

Noddings, N. (2012). The Caring Relation in Teaching. Oxford Rev. Edu. 38 (6), 771–781. doi:10.1080/03054985.2012.745047

Orkibi, H., and Tuaf, H. (2017). School Engagement Mediates Well-Being Differences in Students Attending Specialized versus Regular Classes. J. Educ. Res. 110 (6), 675–682. doi:10.1080/00220671.2016.1175408

Osmond-Johnson, P. (2015). Supporting Democratic Discourses of Teacher Professionalism: The Case of the alberta Teachers' Association. Can. J. Educ. Adm. Pol. 171 (1), 1–27.

Prøitz, T. S. (2015). Learning Outcomes as a Key Concept in Policy Documents throughout Policy Changes. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 59 (3), 275–296. doi:10.1080/00313831.2014.904418

Ramdan, A. Y., and Fauziah, P. Y. (2019). Peran Orang Tua Dan Guru Dalam Mengembangkan Nilai-Nilai Karakter Anak Usia Sekolah Dasar. Pe 9 (2), 100. doi:10.25273/pe.v9i2.4501

Republik Indonesia (2005). Undang-undang Republik Indonesia Nomer 14 Tahun 2005 Tentang Guru Dan Dosen. Available at: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Home/Details/40266/uu-no-14-tahun-2005.

Roberts, B. W., and Jackson, J. J. (2008). Sociogenomic Personality Psychology. J. Pers 76 (6), 1523–1544. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00530.x

Robertson-Kraft, C., and Zhang, R. S. (2018). Keeping Great Teachers: A Case Study on the Impact and Implementation of a Pilot Teacher Evaluation System. Educ. Pol. 32 (3), 363–394. doi:10.1177/0895904816637685

Roorda, D. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., Spilt, J. L., and Oort, F. J. (2011). The Influence of Affective Teacher-Student Relationships on Students’ School Engagement and Achievement: A Meta-Analytic Approach. Rev. Educ. Res. 81 (4), 493–529. doi:10.3102/0034654311421793

Rusznyak, L. (2018). What Messages about Teacher Professionalism Are Transmitted through South African Pre-service Teacher Education Programmes? Saje 38 (3), 1–11. doi:10.15700/saje.v38n3a1503

Sachs, J. (2016). Teacher Professionalism: Why Are We Still Talking about it? Teach. Teach. 22, 413–425. doi:10.1080/13540602.2015.1082732

Savira, S. I., and Khoirunnisa, R. N. (2018). “Understanding How Teacher Perceived Teaching Professionalism,” in In 1st International Conference on Education Innovation (ICEI 2017) (Atlantis Press). 173, 294–297. doi:10.2991/icei-17.2018.77

Seligman, M. E. (2012). Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Smith, J. A., and Osborn, M. (2015). Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis as a Useful Methodology for Research on the Lived Experience of Pain. Br. J. Pain 9 (1), 41–42. doi:10.1177/2049463714541642

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., and Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method, and Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Smith, J. A., and Osborn, M. (2008). “Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis,” in Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods. Editor I. J. A. Smith. 2nd ed. (Los angeles, CA: SAGE Publications), 53–80.

Spilt, J. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., and Thijs, J. T. (2011). Teacher Wellbeing: the Importance of Teacher-Student Relationships. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 23 (4), 457–477. doi:10.1007/s10648-011-9170-y

Suyatno, S., Jumintono, J., Jumintono, J., Pambudi, D. I., Mardati, A., and Wantini, W. (2019). Strategy of Values Education in the Indonesian Education System. Int. J. Instruction 12 (1), 607–624. doi:10.29333/iji.2019.12139a

Sweetman, D., Badiee, M., and Creswell, J. W. (2010). Use of the Transformative Framework in Mixed Methods Studies. Qual. Inq. 16 (6), 441–454. doi:10.1177/1077800410364610

Thijs, J. T., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2008). Task-related Interactions between Kindergarten Children and Their Teachers: the Role of Emotional Security. Inf. Child. Develop. 17 (2), 181–197. doi:10.1002/icd.552

Timperley, H., and Alton-Lee, A. (2008). Reframing Teacher Professional Learning: An Alternative Policy Approach to Strengthening Valued Outcomes for Diverse Learners. Rev. Res. Edu. 32, 328–369. doi:10.3102/0091732X07308968

Torres, A. C., and Weiner, J. (2018). The New Professionalism? Charter Teachers' Experiences and Qualities of the Teaching Profession. epaa 26, 19. doi:10.14507/epaa.26.3049

Tschannen-Moran, M. (2009). Fostering Teacher Professionalism in Schools. Educ. Adm. Q. 45 (2), 217–247. doi:10.1177/0013161x08330501

Vandenbroucke, L., Spilt, J., Verschueren, K., Piccinin, C., and Baeyens, D. (2018). The Classroom as a Developmental Context for Cognitive Development: A Meta-Analysis on the Importance of Teacher-Student Interactions for Children's Executive Functions. Rev. Educ. Res. 88 (1), 125–164. doi:10.3102/0034654317743200

Vu, M. T. (2016). The Kaleidoscope of English Language Teacher Professionalism: A Review Analysis of Traits, Values, and Political Dimensions. Crit. Inq. Lang. Stud. 13 (2), 132–156. doi:10.1080/15427587.2016.1146890

Wardoyo, C., Herdiani, A., and Sulikah, S. (2017). Teacher Professionalism: Analysis of Professionalism Phases. Ies 10 (4), 90. doi:10.5539/ies.v10n4p90

Keywords: adolescent, great teacher, interpersonal relationship, professional teacher, student’s voice

Citation: Suyatno S, Wantini W, Prastowo A, Nuryana Z, Firdausi DKA and Samaalee A (2022) The Great Teacher: The Indonesian Adolescent Student Voice. Front. Educ. 6:764179. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.764179

Received: 25 August 2021; Accepted: 28 December 2021;

Published: 21 January 2022.

Edited by:

Cheryl J. Craig, Texas A&M University, United StatesReviewed by:

Jason DeHart, Appalachian State University, United StatesPaige K. Evans, University of Houston, United States

Copyright © 2022 Suyatno, Wantini, Prastowo, Nuryana, Firdausi and Samaalee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Suyatno Suyatno, c3V5YXRub0BwZ3NkLnVhZC5hYy5pZA==

Suyatno Suyatno

Suyatno Suyatno Wantini Wantini

Wantini Wantini Andi Prastowo

Andi Prastowo Zalik Nuryana

Zalik Nuryana Dzihan Khilmi Ayu Firdausi

Dzihan Khilmi Ayu Firdausi Abdunrorma Samaalee

Abdunrorma Samaalee