- 1School of Medical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of New South Wales, Kensington, NSW, Australia

- 2School of Psychology, Faculty of Science, University of New South Wales, Kensington, NSW, Australia

This study evaluated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in a sample of Honours students (n = 21) and Honours supervisors (n = 41) at a major Australian university. Data were collected from voluntary, online, anonymous surveys, which included ratings of the pandemic’s impact on their 1) experience of Honours research activities, and 2) sense of relatedness, competence, autonomy, and wellbeing. Self-determination theory (SDT), which posits that the psychological needs of relatedness, competence, and autonomy lead to a sense of wellbeing, provided a theoretical framework for understanding student and supervisor experience during the pandemic. Both students and supervisors indicated significant impact of the pandemic on the students’ research projects, and the degree of perceived impact did not differ between students and supervisors. There was no relationship between the severity of impact and student or supervisor wellbeing. Student wellbeing was low, but the hypotheses that student SDT needs would not be met were only partly supported. Overall, the extent to which Honours students’ SDT needs were met predicted wellbeing; the outcome was similar for supervisors. Our hypothesis that SDT needs and wellbeing would be higher for supervisors than for students was supported. The theoretical and practical implications of these findings are discussed, including recommendations for Honours programs as we move through the current pandemic.

Introduction

The aim of this research was to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the experiences of Honours degree students and research supervisors. Prevalent in Commonwealth countries, the one-year Honours degree in Australia is the primary pathway to doctoral studies and subsequent careers in research and academia. It also serves to better prepare graduates for a diverse range of careers where critical thinking and research skills are highly valued (Zeegers and Barron, 2009; Kiley et al., 2011; Backer and Benckendorff, 2018).

The Australian Qualifications Framework (2013) states that Honours graduates should display “a coherent and advanced knowledge of the underlying principles and concepts in one or more disciplines and knowledge of research principles and methods” (p.16). Whilst the amount of prescribed coursework varies (Kiley et al., 2009; Martin et al., 2013; Backer and Benckendorff, 2018), the primary goal of the 4th-year undergraduate Honours year is research training. The research component is an intensive period, beginning with the development of a research question and culminating in the submission of the research thesis. The expected assessable output is usually a minimum of a draft journal manuscript, and often includes a substantial literature review (Kiley et al., 2009).

Each Honours candidature constitutes independent, inquiry-based learning but the individual student experience is influenced by multiple factors. For example, the degree of independence during research project design and implementation varies. Science projects (the focus of this paper) usually involve less student autonomy than do Arts and Social Sciences projects, given the constraints on laboratory resources (Kiley, et al., 2009). Even within the sciences, the nature of the research may vary from online surveys to rigorously controlled experimental manipulations that may involve complex measurement techniques. The supervision experience for the Honours student may also vary across disciplines. For example, there may be a supervisory arrangement of at least two active supervisors whereas in other instances there may only be one supervisor. Similarly, the physical research setting itself may be solitary or social with other research students and personnel.

Prepandemic, studies have suggested that students typically experience lack of confidence, and increased stress, and time management challenges (Cruwys et al., 2015). Compared to the preceding Bachelor’s degree, the Honours degree program typically involves transition from course-work based study to a self-directed research project, a mentor-mentee relationships, and can be a relatively isolating experience (Johnston and Broda, 1996). Student-supervisor interactions impact the Honours student experience and subsequent motivation for postgraduate research (Kiley and Austin, 2000). The research environment, supervisor availability, and a sense of belonging to a community within an institution are important factors promoting support and encouragement, and countering any feelings of isolation (Lovitts, 2005). Despite the challenges, at least one study indicated that students rate the Honours experience highly, especially in terms of the research skills gained and the high levels of support by fellow Honours students (Martin et al., 2013).

The Honours supervisor role confers resource, thesis writing, and research running and management support. Supervising Honours students may be perceived as more difficult than supervising doctoral candidates due to the short timeframe (9 months) during which supervisors are expected to provide intensive and time-consuming research training and supervision. These factors and a dearth of Honours supervisor training (compared to doctoral supervisor training), have the potential to lead to additional stress for the supervisor.

The beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted everyday life (e.g., Dawel et al., 2020), including higher education (e.g., Jung et al., 2021). Both students and staff have been affected, mostly adversely (e.g., through disruption to studies/work due to university campus closure, sudden transition to online educational delivery or reduction or termination of employment) as reflected by reported psychological distress, although occasionally positive aspects have been reported (e.g., advantages to studying/working remotely; e.g., Chirikov et al., 2020; Ye et al., 2020). In one of the few academic-focused studies, academics indicated that their research programs had been adversely affected by university campus and laboratory closures (Abbott et al., 2020). One of the few studies on research students indicated that both collaborative research training and professional relationship building has been negatively impacted (Wang and DeLaquil, 2020). Researchers have yet to study the impact of the pandemic on Honours students and Honours supervisors, and this paper seeks to address that gap.

The Present Study

At the authors’ university, staff and students were requested to work from home to the greatest extent possible. When campus attendance was necessary and permitted, all government restrictions needed to be adhered to, for example, physical distancing and limiting in-person meetings to no more than 2 people. This reduced opportunities for supervisors to train their students on research techniques. Honours projects involving laboratory training, teamwork in close proximity or clinical client contact were impracticable to support. This transition necessarily occurred very rapidly in mid-March 2020, 1 month after the beginning of Honours candidature. Given that the physical restrictions applied to both students and supervisors, it was expected that both samples would give similarly high ratings of the impact of the pandemic on the research project and experience. We predicted that severity of impact would be significantly associated with wellbeing for students, but not for supervisors, because Honours research is paramount to the student experience. Moreover, given that student’s would expect significant face-to-face interaction during course-work, as in their undergraduate years, it was predicted that most students would prefer to go back to in-person coursework.

We propose that Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Ryan and Deci, 2000) provides a useful theoretical framework for understanding the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Honours experience and wellbeing of students and supervisors. SDT has received extensive empirical support in a variety of contexts, including higher education contexts (e.g., Niemiec and Ryan, 2009. Baik et al., 2017a; Baik et al., 2017b). A central aspect of SDT is that there are core psychological needs, the satisfaction of which leads to increased psychological wellbeing (e.g., Sheldon and Elliot, 1999; Ryan et al., 2008). These needs are: relatedness, the feeling of being understood and cared for by others; competence, the feeling of being effective (able to get valued things done); and autonomy, the feeling of being “in control” of one’s own behaviours (i.e., one is not being constrained by external forces in one’s choice of behaviour; Ng et al., 2012). For the remainder of this article, we will refer to these as “SDT needs.”

The pandemic and related government restrictions were likely to have had several consequences for Honours students, including decreased face-to-face interaction with supervisors, fellow students, and other research staff (Wang and DeLaquil, 2020). The rapid uptake of video-conferencing technologies may not have fully compensated for this, leaving Honours students with low feelings of relatedness. We were interested in measuring three aspects of “Honours Relatedness”: relatedness with fellow students (given the findings of Martin et al., 2013), relatedness with staff members (given the increased importance of interactions with supervisors during Honours), and relatedness with the university (given the key importance to the student experience of the concept of “belonging”; Van Gijn-Grosvenor and Huisman, 2020). We predicted low levels of relatedness on all three aspects, given the impact of the pandemic on face-to-face interaction and the need to work from home. We predicted low feelings of competence because of: 1) the disconnection from face-to-face guidance by supervisors and other senior members within the research group (Wang and DeLaquil, 2020); and 2) required learning of different knowledge and skills, which may have left some students feeling less than competent to plan and manage changes to the research project. We predicted low feelings of autonomy if the nature of the research project, or of coursework assessments, needed to be changed due to COVID-19. It was expected that Honours SDT need satisfaction would predict student’s wellbeing, and that such wellbeing would be low.

It was expected that Honours supervisors would also be experiencing decreased face-to-face interactions with both colleagues and students, thus experiencing a low sense of relatedness. We were interested in measuring two aspects of relatedness: relatedness with work colleagues and students, and relatedness with the university. We predicted that academic staff could be experiencing a decreased sense of competence given potential disruption of their normal work activities. We predicted that the restrictions imposed by governments and university leadership would also bring about a feeling of low autonomy regarding their student’s Honours projects. It was expected that SDT need satisfaction would predict supervisor wellbeing and that such wellbeing would be low. However, given that the Honours experience is usually perceived as highly demanding for the student—more so than for the supervisor—it was expected that overall, supervisors would exhibit higher SDT need satisfaction and wellbeing than would students.

Both students and supervisors were asked open-ended questions regarding their experiences of the 2020 Honours year, and basic exploratory thematic analyses were undertaken to better inform recommendations for post-2020 Honours degree procedures. Additional exploratory analyses were undertaken of participant’s responses to 1) a statement regarding equity during the Honours experience, and 2) a general wellbeing scale.

Methods

Participants

Ethics approval was obtained from the UNSW Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: HREAP 3403), and participants gave their informed, written consent to take part in this study.

Students

Participants were School of Medical Sciences and School of Psychology Honours students at the University of New South Wales (UNSW, Sydney), who commenced full-time on-campus study in mid-February 2020. Out of a maximum number of 147 students (19 Neuroscience Honours, 43 School of Medical Sciences Honours, 85 Psychology Honours), a total of 21 responses were recorded; a response rate of 14.19%. Two responses were subsequently excluded from analyses for not listing degree details, so there was a total of 19 responses included in the final analyses. Participants were predominantly male (Male = 42.11%, Female = 31.58%, Not specified = 26.32%), and had a mean age of 24.64 (SD = 6.27; N = 14). The majority of students were domestic/local (Local = 73.68%, International = 5.26%, Not specified = 21.05%) who spoke English as their first language (English = 63.16%, Cantonese = 10.53%, Hebrew = 5.26%, Not specified = 21.05%). Students were from the following programs: Bachelor of Science (36.84%), Bachelor of Psychological Science (26.32%), Bachelor of Psychology (21.05%), Bachelor of Advanced Science (15.79%). Students had the following specialisations: Psychology (63.16%), Medical Science (15.79%), Pathology (10.53%), Pharmacology (5.26), Neuroscience (5.26%). All students reported that they were at the end of their candidature.

Supervisors

Participants were research academics with a Faculty appointment and currently supervising Honours students at the University of New South Wales (UNSW, Sydney). Out of a possible 168 supervisors (37 Neuroscience, 88 School of Medical Sciences, 43 Psychology), a total of 43 supervisor responses were recorded, a response rate of 25.60%. Two responses were subsequently excluded from analyses for not listing degree supervision details, so that 41 responses were included in the final analyses. Supervisors were predominantly female (Female = 41.46%, Male = 39.02%, Not specified = 19.51%), and had a mean age of 46.12 (SD = 13.31, n = 33). At the time of survey participation, supervisors were supervising students from the following degrees: Bachelor of Science (26.83%), Bachelor of Psychological Science (21.95%), Bachelor of Psychology (21.95%), Bachelor of Advanced Science (9.76%), not specified (19.51%). Students supervised were from the following specialisations: Psychology (49%), Medical Science (17%), Pharmacology (2%), Neuroscience (32%). Supervisors had supervised students for a mean of 12.94 years (SD = 10.33, range = 1–40). The mean number of students being supervised by an individual supervisor, at the time of the survey, was 1.91 (SD = 0.90, range = 1–4).

Survey Participation Procedure

Students were invited to participate in the voluntary, anonymous online survey via an announcement posted on their Honours course page in the learning management system platform Moodle. Supervisors were invited by receiving an email from a shared administrative mailbox for the Honours degree. All invitees were reminded to participate in the survey 1 week after the initial invitation. All participants were provided with a Participant Information Statement, Consent form, and web link to access and complete the survey using the Qualtrics platform.

Participants were asked to identify with an Honours degree and specialisation (as a student or supervisor) before completing 9 quantitative and 6 qualitative (open-ended) questions about the impact of COVID-19 on their Honours research project(s) and experience. The detailed wording of the impact questions can be found in the Supplementary Material. They also rated their agreement with key Honours-relevant SDT relatedness, competence, autonomy, and wellbeing statements, and this is detailed below. Participants reported key demographic information, and completed the 15-item general wellbeing scale which was used to determine their Wellbeing Profile (WB-Pro15; Marsh et al., 2020). The details and results of the WB-Pro are reported in the Supplementary Material.

Measures of Honours Relatedness, Competence, Autonomy, and Wellbeing

All participants rated their extent of agreement with several statements associated with SDT needs, using a 9-point scale, with the range: 1 (completely disagree), 2 (strongly disagree), 3 (disagree), 4 (somewhat disagree), 5 (neither agree nor disagree), 6 (somewhat agree), 7 (agree), 8 (strongly agree), and 9 (completely agree).

For students, the relatedness-to-students statement was “I was able to form positive professional relationships with other students in this program,” the relatedness-to-staff statement was “I was able to form positive professional relationships with the staff (e.g., Honours convenors, Honours committee members, teachers) in this program,” the relatedness-to-university statement was “This program built my feeling of belonging to university communities,” the competence statement was “This program built my feeling that I have the capacity to undertake what is required to reach my goals for my Honours year,” the autonomy statement was “This program allowed me to have some choice and to pursue my specific interests in the subject matter,” and the wellbeing statement was “This program built my feeling of wellbeing as a university student.” In addition, the equity statement was “Students are equitably supported to achieve their academic goals in this program.”

For supervisors, the relatedness-to-students/staff statement was “I was able to form positive professional relationships with students and staff (e.g., Honours convenors, Honours committee members, teachers) in this program,” the relatedness-to-university statement was “This program built my feeling of belonging to university academic communities,” the competence statement was “This program built my feeling that I have the capacity to undertake Honours supervision,” the autonomy statement was “This program allowed my Honours students flexibility in revising their research plan in response to COVID-19,” and the wellbeing statement was “This program built my feeling of wellbeing as an Honours supervisor.” In addition, the equity statement was “Honours supervisors are equitably supported to achieve their research supervision goals in this program.”

Because we were interested in whether participants, overall, “agree” or “disagree” (or are neutral) toward the questions, we also collapsed the response distribution into 3 bins, where scores of 1-4 constituted “agree,” a score of 5 constituted “neither agree nor disagree,” and scores of 6-9 constituted “disagree.”

Coding of Participant Responses to Open-Ended Questions

For the qualitative analysis of this research, we incorporated themes derived from common quotes from participant’s open-ended written responses represented in aggregate by the survey data. To explain patterns in participant responses, we used the systematic process of content analysis modelled by Lune and Berg (2016). For “Impact of COVID-19 on research” questions, participant’s responses in each analytic category were read and themes were identified. Then each response was re-read and coded to indicate the presence or absence of each theme (0 = absent, 1 = present). A single participant response could contain multiple themes. For each of the themes, we report the number or proportion of all participant response samples that made relevant statements. All items were rated by a primary coder (ES, in consultation with NK) and a second independent coder blind to the study hypotheses. The majority of Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) were >0.70, indicating that interrater reliability was good (see Supplementary Material: Interrater Reliability, for more specific statistics). ICCs were calculated using SPSS 27, all other analyses were conducted using Statistica (TIBCO Statistica version 13.3.0).

Student Results and Discussion

Impact of COVID-19 on Original Research Project, Assessments, and Honours Experience

All students (N = 19) reported that COVID-19 had impacted their original research project in some capacity. The reported impacts were: Minimum impact (6.67%), Moderate impact (20.00%), Significant impact (40.00%), Total impact (33.33%). When asked to elaborate on changes to their research projects due to COVID-19 circumstances (n = 16), students mentioned the need to amend projects (n = 12), the need to take time off (n = 3), work remotely/online (n = 12), concerns about the quality of their theses (n = 2) and issues with resource availability (n = 1). When outlining contingency plans if the university shut down, the majority of students reported changes to the type of data being collected; students also reported on different aspects of their planned and actual research projects, and of impact on course work and living conditions (see Supplementary Material: Additional Responses).

When asked if they would prefer to go back to face-to face coursework (n = 15), the majority of students reported yes (n = 12), and the remaining students reported that this question was not applicable to them (n = 3). This result supports the hypothesis that the majority of students would prefer to go back to face-to-face coursework.

When asked about the best part of their Honours year, students (n = 15) mentioned gaining new skills and/or knowledge (n = 5), being in the lab or interacting with lab members (n = 4), feeling accomplished after finishing (n = 3), the period before COVID-19 (n = 2), receiving feedback/learning from their supervisor (n = 2), and specific Honours level coursework subjects (n = 2). When asked about the worst part of their Honours year, students (n = 15) mentioned separation from support networks (e.g., family, friends, Honours cohort, lab members; n = 8), project changes (n = 4), issues communicating with supervisors (n = 2), uncertainty (n = 2), COVID-related delays (n = 2), and struggles with motivation (n = 2). Additional survey responses are reported in the Supplementary Material.

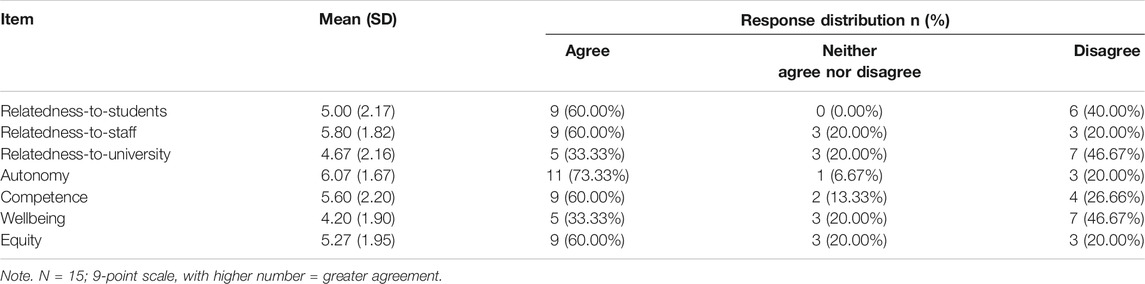

Honours Psychological Needs and Wellbeing

See Table 1 for a breakdown of means and response distributions for items regarding Honours needs (relatedness, competence, autonomy), wellbeing, and equity. The highest number of students “agreed” with the statement for autonomy, competence, relatedness-students, relatedness-staff, and equity. Thus, our hypotheses that student ratings on these variables would be low, were not supported. The highest number of students disagreed with the statements for relatedness-to-university and for wellbeing. Thus, our hypotheses that relatedness-to-university and wellbeing would be low were supported. Contrary to our expectations, ratings of the severity of the impact of COVID-19 on student’s research projects was not significantly associated with Honours-related wellbeing (Spearman’s Rank r = −0.10). The highest number of students agreed with the statement that they had been equitably treated in the program, with quality of the supervisor-student relationship being the most common “agree” comment (see Supplementary Material: Additional Responses).

TABLE 1. Means and response distributions for student agreement with honours SDT needs and wellbeing statements.

Regression Analysis

To test the hypothesis that student’s SDT needs would predict their wellbeing, we conducted simultaneous multiple regression. The overall model was significant R2 = 0.67, F (5,9) = 3.66, p = 0.044, indicating that the hypothesis was generally supported. However, neither relatedness-students (b* = −0.01, t (9) = −0.02, p = 0.987), relatedness-staff (b* = −0.07, t (9) = −0.24, p = 0.819), relatedness-university (b* = 0.05, t (9) = 0.17, p = 0.872), autonomy (b* = 0.20, t (9) = 0.68, p = 0.511), nor competence (b* = 0.75, t (9) = 2.08, p = 0.068), significantly predicted role-related wellbeing.

Supervisor Results and Discussion

Impact of COVID-19 on Original Research Project

Supervisor’s (n = 41) reported impact of COVID-19 on their student’s original research project was: Minimum impact (14.63%), Moderate impact (41.46%), Significant impact (29.27%), Total impact (14.63%).

When asked to “elaborate on changes to research projects,” the small subset that reported minimum impact (n = 6) elaborated that face-to-face testing of human subject volunteers switched to online testing (n = 3), the lab remained open (n = 1), lab closed but managed to test off campus (n = 1) or did not comment (n = 1). The remaining supervisors (n = 35) stated that the “lab closed” (n = 15), the planned experiments were halted/delayed/rescoped (n = 26) or their Honours students were prevented/banned from conducting research on campus (n = 5). When asked to outline their contingency plan (n = 36), the main themes of supervisor responses were: Working remotely (n = 10), running online studies (n = 9), analysing other/existing datasets (n = 8), conducting literature reviews and/or meta-analyses (n = 4), and having no plan or adapting as they went (n = 4). When asked to share the specific problems their Honours students encountered in 2020 (n = 38), supervisors mentioned student’s lack of interaction/connectedness with students and staff (n = 10), mental health concerns (stress, anxiety, loneliness, isolation; n = 10), difficulties surrounding remote supervision (n = 7), practical issues collecting data (n = 6), less time to conduct research and gain experience in the lab (n = 16) and lack of motivation (n = 2).

Supervisors (n = 25) reported little change in the type of research subjects used for their students projects pre-pandemic compared to during the pandemic (see Supplementary Material: Additional Responses).

When asked about the best part of their Honours supervisor experience, supervisors (n = 32) mentioned seeing their students grow and master new skills (n = 9), their student’s resilience (n = 9), and meeting and working with their students (n = 8). When asked about the worst part of their Honours supervisor experience, supervisors (n = 30) reported increased time commitment (n = 6), lack of face-to-face interaction including having provided guidance on how to perform data analysis online (n = 8), concerns for wellbeing of both staff and students including stress and burnout (n = 8), increased use of technology and associated technological issues (n = 4), and student’s negative perception of the academic profession due to stress and strain during COVID-19 (n = 1).

When asked to provide suggestions about how Honours could be improved in the future, supervisors (n = 25) reported the need for better communication—both between the university and faculties/supervisors, and between supervisors and students (n = 7); need for greater flexibility around data collection (n = 3); and the need for a more consistent response across Faculties from the University (n = 2). Individual responses (i.e., n = 1) included eliminating coursework, flexibility for individual research clusters to manage their own response to the pandemic, broader range of thesis methodologies such as systematic reviews and meta-analyses and granting students initial access to a broader range of IT programs and digital support.

When invited to make comments that may help to understand how COVID-19 impacted their capacity to supervise, supervisors (n = 24) reported (n = 1 in each case): Simultaneous increase in personal and professional demands (e.g., parenting responsibilities, editorial work); academics were not alone in facing challenges; inability to predict changes in Honours marking criteria limited their ability to advise students; ongoing budgetary concerns including salary and research funding; regular meetings are essential to determine where support is needed; humans need human interaction, online meetings are challenging to run; supervising in 2020 was more stressful; contingency plans should be encouraged for supervisors taking on Honours students. Additional survey responses are reported in the Supplementary Material.

Supervisor ratings of the severity of the impact of COVID-19 on student’s research projects was not significantly associated with Honours-related wellbeing.

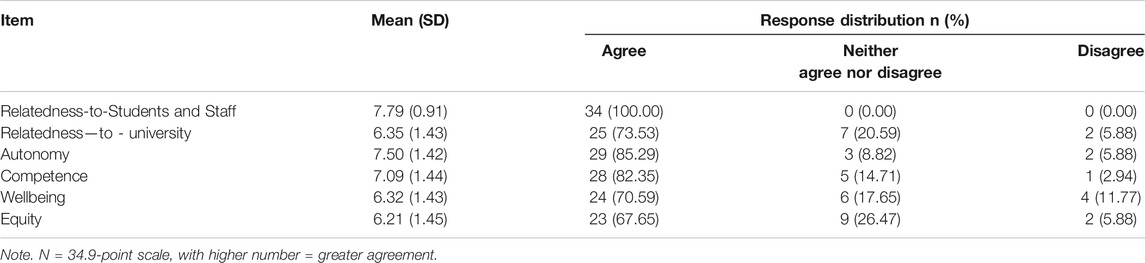

Honours-Related Psychological Needs and Wellbeing

See Table 2 for a breakdown of supervisor response distributions and means for items regarding supervisor SDT needs, wellbeing, and equity. The highest number of participants agreed with all statements suggesting that our hypotheses predicting supervisor SDT need satisfaction and wellbeing would be low, were not supported. As expected, supervisor ratings of the severity of the impact of COVID-19 on student’s research projects was not significantly associated with wellbeing (Spearmans Rank r = −0.10).

TABLE 2. Means and response distributions for supervisor agreement with honours SDT needs and wellbeing statements.

Equity

The highest number of supervisors “agreed” that Honours students were equitably supported to achieve their research supervision goals in the program. When supervisors were asked if students were equitably supported to achieve their academic goals, of the supervisors that responded to this question (n = 35), 77.14% responded “yes,” 5.71% responded “no,” and 17.14% responded “not sure.” When asked to explain their answer to this question, supervisors that responded “yes” (n = 27) reported: Students were well supported by staff, lab members, and the University (n = 7); while students missed some opportunities, they gained others (n = 4); and that sufficient compensatory adjustments were made, including adjustments to thesis marking (n = 8). Supervisors who responded “no” (n = 2) reported: Differences in individual circumstances (both student and supervisor; n = 1); research progress at time of shutdown (n = 1); and lack of face-to-face experience (reliance on Zoom; n = 1). Supervisors that responded “not sure” (n = 6) reported: Not knowing other’s circumstances (n = 1); thesis marking adjustments (n = 1); and that inherent differences in research topic, supervisor’s expertise etc. mean that all students likely don’t receive the same level of support (n = 2), although this was consistent with previous years (n = 1).

Regression Analysis

To test whether supervisor’s needs would predict their wellbeing, we conducted simultaneous multiple regression. The overall model was significant R2 = 0.49, F (4,29) = 7.03, p < 0.001, indicating that the hypothesis was generally supported. Competence was a significant positive predictor of wellbeing (b* = 0.51, t (29) = 2.85, p = 0.008). However, neither relatedness-staff/students (b* = 0.09, t (29) = 0.63, p = 0.513, autonomy (b* = −0.01, t (29) = −0.07, p = 0.948), nor relatedness-university (b* = 0.22, t (29) = 1.27, p = 0.215) significantly predicted wellbeing.

Between-Group Analyses

Impact on Research Project

As expected, a chi-square test of independence found no significant association between role (student, supervisor) and self-reported impact of COVID-19 on their original research projects, X2 (3, N = 60) = 5.03, p = 0.170.

Honours-Related Psychological Needs and Wellbeing

As expected, independent samples t-tests found relatedness-to-staff/students was significantly greater for supervisors (M = 7.79, SD = 0.91) compared to students (M = 5.60, SD = 1.77; note that relatedness ratings were averaged for this comparison), t (47) = −5.75, p < 0.001). Relatedness-to-university communities was significantly greater for supervisors (M = 6.35, SD = 1.43) compared to students (M = 4.67, SD = 2.16), t (47) = −3.23, p = 0.002. Competence was significantly greater for supervisors (M = 7.09, SD = 1.44) compared to students (M = 5.60, SD = 2.20), t (47) = −2.82, p = 0.007. Autonomy was significantly greater for supervisors (M = 7.5, SD = 1.42) compared to students (M = 6.07, SD = 1.67), t (47) = −3.09, p = 0.003, and wellbeing was significantly greater for supervisors (M = 6.33, SD = 1.90) compared to students (M = 4.20, SD = 1.43), t (47) = -4.33, p < 0.001.

General Discussion

Impact and Wellbeing

The specific measure of impact on Honours student’s research projects indicated that there was significant impact. As expected, there was no difference between student’s and supervisor’s impact ratings. The most common impacts reported by students were needing to amend projects and to work online, and by supervisors was that planned experiments were halted/delayed/re-scoped. Unexpectedly, this impact measure was not associated with student wellbeing, even though such wellbeing was, as expected, low, and lower than supervisor wellbeing. It may be that by the time students answered this survey—toward the end of their candidature–they had come to terms with the pandemic-induced changes, regardless of the extent of impact on their research program. As expected, the association between impact and wellbeing for supervisors was not significant. It should be noted that the reliability and validity of the measures used to test these hypotheses have not been established, and thus conclusions are tentative, and further research is needed. For example, the “Impact” question assumes negative impact; respondents may not have interpreted the valence of the impact in that assumed way.

The qualitative data for students (see Supplementary Material: Additional Responses) highlight other aspects of the impact of the pandemic on their research project. For example, many students reported that the worst part of the Honours year was separation from support networks due to the remote nature of the year. Whilst fear of failure, time management, and increased workload intensity are typical concerns of Honours students (i.e., pre-pandemic; Allan, 2011), student concerns reported here reflect the novel pandemic context. These concerns were likely more difficult for Honours students to cope with and seek support for, due to the rapidly evolving nature of the pandemic and lack of appropriate support resources. Supervisors reported themes of burnout and increased time commitment (i.e. increased workload) as the worst part about the year. These themes were not apparent in student responses, further suggesting that students’ lived reality of Honours was not more intense or challenging compared to their preCOVID-19 expectations. Professional support networks are usually important for experience and wellbeing of Honours students. However, during the pandemic, the student-supervisor relationship was crucially important. Overall, the need for independent learning was challenging for students due to separation from support networks, project disruptions, and lack of prior research experience.

Complementary qualitative data for supervisors highlighted other aspects of the impact of the pandemic on their research. Novel issues included the increasing need to balance practical and administrative demands with the increased needs of their students, and the transition from face-to-face research project planning and coordination to the challenge of overseeing the research project remotely. While managing such issues is not necessarily novel for Honours supervisors, the sudden and significant increase in demand for supervisors’ time and attention likely led to increased feelings of distress and burnout. Finally, although the pandemic altered mechanisms for providing supervisory support, these were perceived as equitable by most supervisors surveyed.

Need Satisfaction and Wellbeing: Theoretical Implications

According to SDT (Ryan and Deci, 2000), it was expected that students’ Honours-related psychological need satisfaction would be low. This was the case for relatedness-to-university (average “disagree” rating), but not for the other SDT needs. As expected, student wellbeing was low and lower than that for supervisors. These findings, plus the fact that overall, the needs significantly predicted wellbeing, suggest support for SDT as applied in this context. However, the finding that the needs were not individually associated with wellbeing suggests that more work needs to be done (e.g., the creation of a scale with multiple items for each SDT need).

For supervisors, it was expected that Honours needs and wellbeing would be low, however, this was not the case—ratings were most frequently within the “agree” range. Because these ratings occurred at the end of the Honours year, this finding may be reflective of supervisor’s relief in supporting their students to completion. As with the student data, although there is some support for SDT being usefully applied to this specific educational context, more work needs to be done (e.g., improving measurement validity and reliability).

The relatedness-university statement was not endorsed by students and was the least endorsed SDT need for supervisors. Note that most Honours students in this cohort would have undertaken their Bachelor degree at the same institution, and most supervisors would have been employed by the institution for many years. Thus, the stress of the pandemic experience may have contributed to these ratings.

Equity

The majority of students and supervisors agreed that students were equitably supported (for detailed summaries, see Supplementary Material). Students noted that equitable support was contingent on the quality of the student-supervisor relationship. Access to resources (including facilities and staff), and agency in assessment changes were also important. Similarly, supervisors noted that although there are likely differences in student experiences, on average these differences remained consistent despite the pandemic. Regarding the pandemic context, supervisors noted that students were well supported, and appropriate adjustments were made.

Wellbeing Profile

Our participants completed the WB-Pro (Marsh et al., 2020) as part of the general survey. Please see the Supplementary Material for details of the WB-Pro responses and how they relate to both 1) the Honours SDT needs and wellbeing variables and 2) the original report regarding age differences (Marsh et al., 2020). Findings relevant to understanding the Honours student and supervisor experience are briefly reported here.

Student average WB-Pro ratings appear to be lower than Marsh et al. (2020) sample (as reported by James Donald, personal communication, 15th March, 2021), while supervisor average WB-Pro ratings appear to be similar. Responses to the Honours wellbeing items correlated with the both student and supervisor average WB-Pro Average ratings. These WB-Pro Average ratings were higher for supervisors than for students.

Consistent with Marsh et al. (2020), we observed age differences for some dimensional factors (e.g., supervisors had higher competence ratings than students; supervisors were on average 20 years older). However, compared to Marsh et al. (2020), both students and supervisors in our sample appeared to provide lower ratings of optimism, and higher ratings of positive relationships. Amongst supervisors, the decreased lack of predictability regarding the future (e.g., job security) may have reduced optimism, whilst at the same time, there may have been an increased emphasis on positive relationships because isolation experiences highlighted the value of such relationships.

Limitations

Our conclusions are restricted by the following limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional design administered close to research submission limits our ability to make strong causal inferences about the impact of the pandemic. Future studies could examine the longitudinal impact of the pandemic on research experience and wellbeing. Nevertheless, a potential strength of the paper is that the cross-sectional surveys were conducted toward the end of the candidature for most participants, rather than retrospectively. The data are of high validity since both students and supervisors were most acutely affected during the survey participation window.

Secondly, our measures could be improved, and validity better tested by considering standard student course satisfaction ratings and student academic grade data. Thirdly, selection bias should be considered, given the small sample size. The survey link was sent to all students and supervisors in participating Honours programs, allowing for selection of a random sample. However, it is possible our sample is non-random. For example, perhaps resilient students and supervisors were more motivated to participate. Alternatively, students and supervisors whose experience was more adversely impacted may have been more motivated to participate.

Whilst we surveyed students about their experiences transitioning from on-campus to conducting research from home, and how they coped with the absence of face-to-face academic support systems, these questions were not asked of supervisors. This is a limitation; however, open-ended written survey responses from supervisors provided an avenue to address supervisor concerns and assisted in providing recommendations for supervisors to manage their Honours related activities during the pandemic (see below). We recommend future survey questions address supervisors transition to working-from-home and whether supervisor were, for example, in a carer role, and how this impacted their Honours supervisor duties.

Our small sample also prevented us from performing Honours program (e.g., Medical Sciences vs. Psychology) specific analyses, or stratifying for sex, age, or cultural background. Additionally, we did not distinguish between the testing of human subjects online compared to face-to-face, or capture the duration of disruptions to Honours experience when measuring the impact of the pandemic.

Practical Implications and Recommendations

During 2020, Honours students and supervisors surveyed in this study were expected to rapidly adjust to new strategies for conducting research, including working remotely. Moving forward, research students around the world remain concerned about whether they will be able to initiate and complete their research lab work (Blankstein et al., 2020; Elmer and Durocher 2020). In the lead up to survey participation, the College Crisis Initiative Data Dashboard (August 2020) indicated that only a quarter of the surveyed 2981 US universities and colleges planned to open their campuses in person, suggesting ongoing disruption to research training. Based on the outcomes of this study, we address practical implications for moving research projects forward and recommend strategies for addressing the situation of COVID-19 uncertainty. Explicit curricular and extracurricular environmental strategies can be put in place, including 1) online as well as face-to-face support mechanisms to strengthen relatedness with peers, supervisors, and the wider university community (note that many institutions offer totally online Honours programs; we could learn from their experience; see Rodafinos et al., 2018, and 2) opportunities to further develop self-management, which is the capacity to effectively pursue meaningful goals and to be flexible in the face of set-backs (Cranney et al., 2016), and includes skills such as time management and resilience (e.g, Stallman, 2011). Resilient individuals are more capable of dealing with uncertainty and seeking necessary social support (Ozbay et al., 2007) which should mitigate against the psychologically adverse consequences of COVID-19 (Labrague, 2021).

Based on the findings reported in this paper (including the detailed comments and suggestions provided by both students and supervisors, as reported also in the Supplementary Material), we make the following specific recommendations:

• Preparing a contingency research plan, which is entirely executable remotely, is a recommended strategy to reduce the adverse aspects of COVID-19 restrictions on the project, including the associated stress response (Ozbay et al., 2007). Key considerations in developing an appropriate contingency plan include acknowledging at the early stages that scientific research rarely goes exactly as planned, identification of possible challenges to the research methods and likely solutions, and instilling attitudes of perseverance and optimism to assist the research process.

• Prior to project commencement, discussion should occur between Honours students, supervisors, and Honours program convenors to determine if the planned research is feasible. Can the research questions be addressed, the hypotheses tested, and the experiments carried out in a COVID-safe way? If not, modifications to adjust the project questions and hypotheses could be effective in managing expectations. Strategies such as expanding the literature review to a systematic review or meta-analysis, that could comprise the entire research project if it becomes impossible to collect new empirical data, should be considered as a back-up plan, from the outset.

• Stringent accreditation standards maintained by the academic discipline may dictate the research requirements to achieve an Honours degree and the minimum requirement for further (Masters or PhD) study. Therefore, any revision of the proposed student project should be discussed with the program convenor to ensure that the student remains capable of achieving the relevant standard for degree completion.

• There are detrimental effects of working remotely, including limited ability to connect with others, and reliance on support networks external to the university for social connection and support. We recommend implementation of wellbeing interventions to ensconce students in a wider research community, including a digital platform to create a community environment, overcome the limited human interactions, and foster a social presence (Chen and Jang, 2010; Kim et al., 2011; Fiock, 2020; Munoz et al., 2021; see also https://teaching.unsw.edu.au/healthyuni-main/cc-practical-examples.

• Until the pandemic eases, line managers should take measures to lighten the load of supervisors, for example by 1) monitoring supervisor’s teaching and administrative load, and finding creative solutions to provide institutional support for Honours students, and 2) encouraging prospective Honours students to take program leave if the project requires access to campus.

• Pre-pandemic, Honours supervisors had expertise in supervising in a face-to-face setting, but little experience of how to supervise remotely (see Thorpe, 2010). Furthermore, a lack of universal online teaching experiences meant Honours students and their supervisors were unprepared for remote learning and solely online communications. Major challenges to supervision include difficulty in connecting Honours students with academic support systems remotely, loss of incidental student learning through peers, and building relationships and communicating with students solely online. Therefore, strategies that closely replicate the organic traditionally on-campus experiences need to be sourced and built into online supervision communication strategies (Fiock, 2020; Munoz et al., 2021). For example, use real-time online communication platforms such as Teams, or Slack.

• Honours supervisors could develop ways to engage and motivate students online, to reduce isolation (e.g., create an online community with synchronous e-meetings, for research collaboration), and promote self-directed learning and autonomy (e.g., gather specific feedback on a regular scheduled basis and provide avenues for students to seek additional assistance if required). Supervisors may need to provide more scaffolds for students who are less comfortable with autonomous learning, which is key to Honours progress. The long-term benefits of online reframing of the Honours supervisory approach during COVID-19 include enabling Honours supervision of a project internationally or during sabbatical leave.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to incorporate both student and supervisor perspectives on the impact of COVID-19. This dual data set provides a unique opportunity to compare student and supervisor impact perceptions and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, this study focuses specifically on the Honours program, which is an essential training ground for future researchers in a number of English-speaking countries. This is important because the Honours experience is distinct in many ways (predominantly research focussed, short timeline), although many of the same issues have been reported in doctoral training (e.g., Wang and DeLaquil, 2020). Despite the restricted conclusions drawn (e.g., due to small sample size), our findings provide interesting insights into the perceptions and wellbeing of Honours students and supervisors during the COVID-19 pandemic. If the recommendations are implemented, such measures should not only buffer the negative impact of future pandemic restrictions, but also facilitate a more constructive approach to, and productive result for the Honours experience for both students and supervisors, in both pandemic and non-pandemic times.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the UNSW Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: HREAP 3403), and participants gave their informed, written consent to take part in this study.

Author Contributions

NK, JC, and BS contributed to conception and design of the study. ES organized the database. ES performed the statistical analysis. JC, ES, NK, and BS wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the UNSW School of Medical Science’s Research Support Committee, and the UNSW School of Psychology for their generous support of this project. We also thank Catherine Viengkham for her assistance with qualitative coding, and Cristan Herbert for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.758960/full#supplementary-material

References

Abbott, J., Bancroft, H., and Murray, L. (2020). Members Experience during the Pandemic. InPsych: The Bulletin of the Australian Psychological Society Ltd. Available at: https://teaching.unsw.edu.au/HealthyUni August/September.4449.

Allan, C. (2011). Exploring the Experience of Ten Australian Honours Students. Higher Educ. Res. Develop. 30 (4), 421–433. doi:10.1080/07294360.2010.524194

Australian Qualification Framework (2013). Australian Qualification Framework Council. Canberra, Australia: National Library of Australia. Available at: https://www.aqf.edu.au/.

Backer, E., and Benckendorff, P. (2018). Australian Honours Degrees: The Last Bastion of Quality? J. Hospitality Tourism Manage. 36, 49–56. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.08.001

Baik, C., Larcombe, W., Brooker, A., Wyn, J., Allen, L., Brett, M., et al. (2017a). Enhancing Student Mental Wellbeing: A Framework for Promoting Student Mental Wellbeing in Universities. Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education. Available at: http://unistudentwellbeing.edu.au/framework/http://unistudentwellbeing.edu.au/framework/.

Baik, C., Larcombe, W., Brooker, A., Wyn, J., Allen, L., Field, R., et al. (2017b). Enhancing Student Mental Wellbeing: A Handbook for Academic Educators. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education. Available at: melbourne-cshe. unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/2408604/MCSHE-Student-Wellbeing-Handbook-FINAL.pdf.

Blankstein, M., Frederick, J., and Wolff-Eisenberg, C. (2020). Student Experiences during the Pandemic Pivot. New York: Ithaka S+R. doi:10.18665/sr.313461

Chen, K.-C., and Jang, S.-J. (2010). Motivation in Online Learning: Testing a Model of Self-Determination Theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 26 (4), 741–752. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.01.011

Chirikov, I., Soria, K. M., Horgos, B., and Jones-White, D. (2020). Undergraduate and Graduate Student’s Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. SERU Consortium, University of California - Berkeley and University of Minnesota. Available at: https://cshe.berkeley.edu/seru-covid-survey-reports.

College Crisis Initiative (2020). Davidson College (Online). Available at: https://collegecrisis.shinyapps.io/dashboard/August 24, 2020).

Cranney, J., Cejnar, L., and Nithy, V. (2016). “Developing Self-Management Capacity in Student Learning: A Pilot Implementation of Blended Learning Strategies in the Study of Business Law,” in Enabling Reflective Thinking: Reflective Practices in Learning and Teaching. Editors K. Coleman, and A. Flood (Champaign, IL: Common Ground Publishing), 354–369. Available at: http://thelearner.cgpublisher.com/product/pub.62/prod.57.

Cruwys, T., South, E. I., Greenaway, K. H., and Haslam, S. A. (2015). Social Identity Reduces Depression by Fostering Positive Attributions. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 6 (1), 65–74. doi:10.1177/1948550614543309

Dawel, A., Shou, Y., Smithson, M., Cherbuin, N., Banfield, M., Calear, A. L., et al. (2020). The Effect of COVID-19 on Mental Health and Wellbeing in a Representative Sample of Australian Adults. Front. Psychiatry 11 (1026), 579985. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.579985

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2012). “Self-determination Theory,” in Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology. Editors P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, and E. T. Higgins (Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Ltd), 416–437. doi:10.4135/9781446249215.n21

Elmer, S. J., and Durocher, J. J. (2020). Moving Student Research Forward during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 44 (4), 741–743. doi:10.1152/advan.00153.2020

Fiock, H. (2020). Designing a Community of Inquiry in Online Courses. Irrodl 21 (1), 134–152. doi:10.19173/irrodl.v20i5.3985

Johnston, S., and Broda, J. (1996). Supporting Educational Researchers of the Future. Educ. Rev. 48 (3), 269–281. doi:10.1080/001319196048030610.1080/0013191960480306

Jung, J., Horta, H., and Postiglione, G. A. (2021). Living in Uncertainty: the COVID-19 Pandemic and Higher Education in Hong Kong. Stud. Higher Educ. 46 (1), 107–120. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1859685

Kiley, M., and Austin, A. (2000). Australian Postgraduate Students' Perceptions, Preferences and Mobility. Higher Educ. Res. Develop. 19 (1), 75–88. doi:10.1080/07294360050020480

Kiley, M., Boud, D., Cantwell, R., and Manathunga, C. (2009). The Role of Honours in Contemporary Australian Higher Education. Australian Learning and Teaching Council Report. Available at: https://ltr.edu.au/resources/The%20Role%20of%20Honours%20in%20contemporary%20Australian%20Higher%20Education.pdf.

Kiley, M., Boud, D., Manathunga, C., and Cantwell, R. (2011). Honouring the Incomparable: Honours in Australian Universities. High Educ. 62 (5), 619–633. doi:10.1007/s10734-011-9409-z

Kim, J., Kwon, Y., and Cho, D. (2011). Investigating Factors that Influence Social Presence and Learning Outcomes in Distance Higher Education. Comput. Educ. 57, 1512–1520. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2011.02.005

Labrague, L. J. (2021). Resilience as a Mediator in the Relationship between Stress-Associated with the Covid-19 Pandemic, Life Satisfaction, and Psychological Well-Being in Student Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 56, 103182. available online 20 August 2021. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103182

Lovitts *, B. E. (2005). Being a Good Course‐taker Is Not Enough: a Theoretical Perspective on the Transition to Independent Research. Stud. Higher Educ. 30 (2), 137–154. doi:10.1080/03075070500043093

Lune, H., and Berg, B. L. (2016). Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. 8th ed. Boston: Pearson.

Marsh, H. W., Huppert, F. A., Donald, J. N., Horwood, M. S., and Sahdra, B. K. (2020). The Well-Being Profile (WB-Pro): Creating a Theoretically Based Multidimensional Measure of Well-Being to advance Theory, Research, Policy, and Practice. Psychol. Assess. 32 (3), 294–313. doi:10.1037/pas0000787

Martin, F. H., Cranney, J., and Varcin, K. (2013). “Student’s Experience of the Psychology Fourth Year in Australia,” in Proceedings of the Australian Conference on Science and Mathematics Education, 163–168. Available at: https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/IISME/issue/view/606/showToc.

Munoz, K. E., Wang, M.-J., and Tham, A. (2021). Enhancing Online Learning Environments Using Social Presence: Evidence from Hospitality Online Courses during COVID-19. J. Teach. Trav. Tourism, 1–20. published online: 08 Apr 2021. doi:10.1080/15313220.2021.1908871

Ng, J. Y., Ntoumanis, N., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Duda, J. L., et al. (2012). Self-determination Theory Applied to Health Contexts: A Meta-Analysis. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 7, 325–340. doi:10.1177/1745691612447309

Niemiec, C. P., and Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness in the Classroom. Theor. Res. Educ. 7 (2), 133–144. doi:10.1177/1477878509104318

Ozbay, F., Johnson, D. C., Dimoulas, E., Morgan, C. A., Charney, D., and Southwick, S. (2007). Social Support and Resilience to Stress: from Neurobiology to Clinical Practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 4 (5), 35–40.

Rodafinos, A., Garivaldis, F., and McKenzie, S. (2018). A Fully Online Research portal for Research Students and Researchers. JITE:IIP 17, 163–179. doi:10.28945/4097

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 55 (1), 68–78. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.6810.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68

Ryan, R. M., Huta, V., and Deci, E. L. (2008). Living Well: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective on Eudaimonia. J. Happiness Stud. 9, 139–170. doi:10.1007/s10902-006-9023-4

Sheldon, K. M., and Elliot, A. J. (1999). Goal Striving, Need Satisfaction, and Longitudinal Well-Being: The Self-Concordance Model. J. Pers Soc. Psychol. 76, 482–497. Available at: http://selfdeterminationtheory.org/SDT/documents/1999_SheldonElliot.pdf. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.76.3.482

Stallman, H. M. (2011). Embedding Resilience within the Tertiary Curriculum: A Feasibility Study. Higher Educ. Res. Develop. 30, 121–133. doi:10.1080/07294360.2010.509763

Thorpe, M. (2010). Rethinking Learner Support: The challenge of Collaborative Online Learning. Open Learn. J. Open, Distance e-Learning 17 (2), 105–119. doi:10.1080/02680510220146887a

Van Gijn-Grosvenor, E. L., and Huisman, P. (2020). A Sense of Belonging Among Australian university Students. Higher Educ. Res. Develop. 39 (2), 376–389. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1666256. doi:10.1080/07294360.2019.1666256

Wang, L., and DeLaquil, T. (2020). The Isolation of Doctoral Education in the Times of COVID-19: Recommendations for Building Relationships within Person-Environment Theory. Higher Educ. Res. Develop. 39 (7), 1346–1350. doi:10.1080/07294360.2020.1823326

Ye, Z., Yang, X., Zeng, C., Wang, Y., Shen, Z., Li, X., et al. (2020). Resilience, Social Support, and Coping as Mediators between COVID-19-Related Stressful Experiences and Acute Stress Disorder Among College Students in China. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 12 (4), 1074–1094. doi:10.1111/aphw.12211

Keywords: COVID-19, wellbeing, honours, self-determination theory, research supervision, student experience

Citation: Kumar NN, Summerell E, Spehar B and Cranney J (2021) Experiences of Honours Research Students and Supervisors During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Pilot Study Framed by Self-Determination Theory. Front. Educ. 6:758960. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.758960

Received: 15 August 2021; Accepted: 16 September 2021;

Published: 12 October 2021.

Edited by:

Isabel Morales Muñoz, University of Birmingham, United KingdomReviewed by:

Caroline Strevens, University of Portsmouth, United KingdomKristina Almazidou, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Copyright © 2021 Kumar, Summerell, Spehar and Cranney. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Natasha N. Kumar, bmF0YXNoYS5rdW1hckB1bnN3LmVkdS5hdQ==

Natasha N. Kumar

Natasha N. Kumar Elizabeth Summerell

Elizabeth Summerell Branka Spehar

Branka Spehar Jacquelyn Cranney

Jacquelyn Cranney