- MIOS Research Group, Department of Communication Studies, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

Combining the transactional model of stress and coping and expressive writing theory, this research studied whether writing on one’s personal experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic may improve young people’s emotional reactions to the situation. A standard expressive writing instruction was compared to a positive writing instruction (writing about the positive aspects) and a coping writing instruction (writing about previous experiences and how these are helpful to cope with the situation). The results showed that participants in the positive writing instruction experienced a significantly higher positive change in feelings in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic in comparison with participants in the other writing instructions. This relationship was not mediated by the relative contents of writing. The results can help in designing online social support interventions for coping with the COVID-19 pandemic and stressful events in general.

1 Introduction

The affordances of social support websites (e.g. accessibility, anonymity, mutual social norms to share the negative) make social support from peers more accessible for young people who feel reluctant or unable to seek support in an offline context (Schouten et al., 2007; Choi and Toma, 2014; Vermeulen et al., 2018; Prescott et al., 2019). Compared to social media, which also offer the possibility for support, the social support websites we address here are specifically developed to offer forums to allow young people to interact with peers to find informational and emotional support in times of stress. They may address a certain topic (e.g. health concerns) or a variety of topics that are important to the life phase of young people (e.g. health concerns, but also sexuality, peer and family conflicts, etc.). These forums are mostly text-based and anonymous, which results into narrative-like messages that we will refer to as personal narratives.

Research has showed that the use of these kind of forums on social support websites have positive effects on adults’ well-being (e.g. Rains and Young, 2009; Rains et al., 2015; Yang, 2018), but there may be risks for young people. Young people’s tendency to focus on the negative aspects of their experiences may put users of social support websites at risk for increased negative emotions (Choi and Toma, 2014; Kramer et al., 2014; Batenburg and Das, 2015; Taylor et al., 2016; Rimé et al., 2020). More research is needed on how we can improve the content and interface design of social support websites to overcome this pitfall.

According to the transactional model of stress and coping, emotions and stress in relation to an event result from one’s cognitive appraisals of the situation (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). If the individual believes that a situation has a significant negative impact on one’s well-being (primary appraisal) and does not believe to be able to cope with the specific stressor (secondary appraisal), the situation will have a negative effect on one’s emotions and stress level (Greenaway et al., 2015; Ben-Zur, 2019). One can expect that it may be better to help young people to reappraise a stressful event by focusing on the positive aspects and consequences of the stressful situation. Expressive writing theory, i.e. a psychotherapeutic writing intervention on one’s deepest emotions and thoughts, has already proven to help to reflect more effectively on negative experiences which results in positive effects on people’s well-being (Frattaroli, 2006).

In this study we theorize that expressive writing instructions on social support websites could possibly help young people to reflect more effectively on their negative experiences, change their cognitive appraisals and, consequently, their emotional reactions in relation to a negative experience. However, expressive writing theory has not often been applied to the context of social support websites. Moreover, the effects of expressive writing theory on young people’s well-being are still understudied (Travagin et al., 2015).

In an online experiment with 156 Flemish adolescents and young adults, participants were asked to write about their experience with the lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic in one of three conditions: a standard expressive writing instruction (writing about one’s emotions, thoughts and coping strategies in relation to the lockdown); a positive writing instruction (focusing on the positive aspects of the lockdown); and a coping condition (focusing on previous experiences and how these are helpful to cope with the lockdown). Participants’ positive and negative feelings in relation to the lockdown were measured before and after the writing instruction to measure change in feelings.

This research is one of the first to apply the transactional model of stress and coping and expressive writing theory to the context of online support seeking. Combining these theories may help to explain under which circumstances writing about a stressful event, in this case the COVID-19 pandemic, in a social support context affects young people’s emotional reactions towards the situation. This study can help to design online interventions to provide social support and emotional relief to young people.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Social Support Websites for Sharing Personal Narratives About Stressful Events

During the COVID-19 pandemic, especially young people in adolescence and young adulthood are emotionally effected by the governments’ measures to stop the spreading of the virus (Shanahan et al., 2020; Magson et al., 2021). Due to a lack of offline social support during the COVID-19 pandemic, Flemish social support websites for sharing personal experiences about stressful events with peers have massively increased in popularity with young people (De Maeseneer, 2020; Torbeyns, 2020).

Meta-analyses have demonstrated that the use of social support websites has significant positive effects on various well-being outcomes, such as perceived social support, quality of life and self-efficacy in coping with stressful events (e.g. Rains and Young, 2009; Rains et al., 2015; Yang, 2018). However, the effects of social support websites to young people’s well-being is scarce (Ali et al., 2015) and these effects may be different for young people. Young people may have the tendency to dwell on the negative aspects of their experiences and the negative emotions that result from it, and as a result, may become overwhelmed with their own negative emotions (Choi and Toma, 2014; Taylor et al., 2016; Rimé et al., 2020). Especially young adolescents may not have developed all cognitive and emotional skills to reflect effectively about distressing events (Travagin et al., 2015; Taylor et al., 2016). Longitudinal research also found rumination and worry may eventually result in more symptoms of depression and anxiety with adolescents (Young and Dietrich, 2015).

As an additional layer to this problem, research on social support websites warns that this negativity bias may not only leave writers, but also readers and responders, with even more anxiety and stress (Rains and Wright, 2016). Research shows that users may be influenced by negative social comparison processes (i.e. identifying with peers’ negative experiences; Batenburg and Das, 2015) and therefore may come to identify themselves more with the problems they experience rather than having a clearer and more positive perspective on it (Lawlor and Kirakowski, 2014). It may also lead to co-rumination, in which young people extensively discuss and speculate about problems they have in common, while focusing on negative feelings and consequences (Rose, 2002). Research on private conversations on social media found that co-rumination was associated with depressive symptoms amongst adolescents between 12 and 19 years old (Frison et al., 2019). Other research on the effect of emotional contagion on social media shows that the negative tone of messages posted by users may influence the tone of others’ messages in a negative way (Kramer et al., 2014). For this same reason, research on online social support for young people with mental health problems suggests that it is important to be cautious when pairing users with similar health conditions (O’Leary et al., 2018; Andalibi and Flood, 2021).

Due to the possible negative effects of sharing a personal experience on social support websites, more research is needed on how writing about a stressful event, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, may relate to young people’s emotional reactions towards the stressful event. Moreover, it is important to find ways to improve young people’s reflections upon distressing events on social support websites.

2.2 Changing Emotional Reactions to a Stressful Event: Cognitive Appraisals and Expressive Writing Instructions

According to the transactional model of stress and coping (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984) emotions in relation to a situation result from one’s cognitive appraisals of the situation (Greenaway et al., 2015; Ben-Zur, 2019). A primary appraisal reflects whether or not the individual believes that the event has a significant impact on one’s well-being (Greenaway et al., 2015; Ben-Zur, 2019). Some may perceive an event to be a threat to their wellbeing (threat appraisal), while others may find challenges that have a positive effect on their well-being (challenge appraisal), at the present moment or in the future. A secondary appraisal occurs when someone believes to be able to cope with the specific stressor or not (Greenaway et al., 2015; Ben-Zur, 2019). In turn, coping with a stressful event is viewed as a continuing process reappraisal of the situation and the available coping resources (Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck, 2016).

One promising way to change one’s appraisals of a stressful situation is an expressive writing instruction. It can be defined as “an individually focused intervention designed to improve emotional expression and processing during adaptation to stressful situations and, as a consequence, improve psychological and physical health” (Pennebaker, 2004; Travagin et al., 2015, p. 43). A standard expressive writing instruction implies that someone writes about his/her deepest thoughts and emotions, which allows to reorganize thoughts and gain new insight (Pennebaker and Seagal, 1999). It was found to come with positive outcomes on well-being, such as enhanced mood, lowered depressive symptoms and anxiety and even better physical health (Frattaroli, 2006).

Multiple studies have tried to examine under which circumstances expressive writing is most beneficial, including the content of the narrative that is written (e.g. Frattaroli, 2006). For example, writers who use a high number of positive-emotion words, a moderate number of negative-emotion words and more cognitive words (e.g. think, believe, realize) in their narratives tend to benefit the most in terms of their physical health and emotional functioning (Smyth, 1998; Pennebaker and Seagal, 1999; Burton and King, 2004; Pennebaker, 1999). Most of this research was examined with adult samples and research on the effects of expressive writing to young people’s well-being is scarce (Travagin et al., 2015).

Although the primary purpose of sharing a personal narrative about a stressful situation on a social support website is to receive advice and emotional support from others, writing a personal narrative on these websites also lends young people the opportunity to deeply reflect on their experiences. Expressive writing theory therefore seems to be an interesting theory to apply within the context of social support websites. One study found that the writing of personal narratives on social support websites was a motivation for use itself and an important factor in sustained use of these websites (Ma et al., 2017). They therefore suggests to take the effects of expressive writing into account when designing an online social support platform (Ma, et al., 2017).

Combining the transactional model of stress and coping and expressive writing theory, we may expect that if we can change the way young people appraise and write about a negative event on social support websites, we may possibly change their psychological reactions to the situation itself. This research will therefore examine whether different expressive writing instructions focused on changing primary and secondary appraisals of a stressful event, in this case the COVID-19 pandemic, may affect young people’s emotional reactions to the stressful event in question. This study may therefore test the possible usefulness of these theories for redesigning social support websites for young people.

RQ: Can different expressive writing instructions focused on changing primary and secondary appraisals of a stressful event affect young people’s emotional reactions to the stressful event in question (e.g. the COVID-19 pandemic)?

2.3 Expressive Writing Theory and Primary Appraisal: Improving One’s Positive Feelings in Relation to the Stressful Event by Focussing on the Benefits

According to appraisal theory, the first step to changing one’s emotional reaction to a stressful situation is to learn to perceive the situation as an opportunity to one’s well-being (Greenaway et al., 2015; Ben-Zur, 2019). Since young people may have the tendency to focus on the negative aspects (e.g. Duprez et al., 2015), it may be important to help them to find the positive in their distressing experiences. Based on expressive writing theory we can assume that helping young people to explicitly reflect on the positive aspects of an experience may help to reappraise the stressor.

Writing about benefits is understood to “restructure previous maladaptive cognitive schemas and perspectives” (Facchin et al., 2014, p. 133). In other words, it may be an effective strategy to reappraise a stressful event. However, the effects of writing about benefits is not often studied with young adults and adolescents. Two studies on writing with young adults have shown writing about benefits may be more effective than a standard expressive writing instruction (i.e. writing on thoughts and emotions) (McCullough et al., 2006; Lichtenthal and Cruess, 2010). One research with adolescents showed that a task of writing about the positive aspects of a stressful situation positively impacted their self-concept compared to a standard expressive writing and neutral writing instruction (Facchin et al., 2014).

We hypothesize that a positive writing instruction (i.e. writing about the positive consequences of a stressful situation) may result in a higher positive change in feelings in relation to the lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic compared to a standard expressive writing condition (i.e. writing about one’s thoughts and emotions in relation to a stressful event). Furthermore, we hypothesize that writing relatively more about the positive aspects and consequences than the negative aspects and consequences will mediate the positive relation between the positive writing instruction and a positive change in feelings.

H1: A positive writing instruction will result in a higher positive change in feelings in relation to lockdown compared to a standard expressive writing condition.

H2: The relative number of positive aspects and consequences compared to negative aspects and consequences described in the narrative will mediate the relationship between a positive writing instruction and a positive change in feelings.

2.4 Expressive Writing Theory and Secondary Appraisal: Positive Self-Affirmation of One’s Coping Abilities by Focussing on Previous Successful Coping Strategies

According to appraisal theory, the second step to changing one’s psychological reaction to a stressful situation is to believe in one’s own coping abilities in relation to the situation. Based on expressive writing theory we can assume that helping young people to reflect on their previous successful coping efforts may help to reappraise one’s coping self-efficacy.

The idea of self-affirmation suggests that writing may help to affirm one’s values and actions, which will influence one’s self-concept and promote effective coping (Taylor et al., 2016). Previous research on expressive writing theory has hypothesized that writing may help to reflect upon one’s coping strategies (e.g. How did I cope before? How can I cope better?) which in turn may improve one’s self-efficacy in coping (Facchin, 2010; Frattaroli, 2006).

For example, a study on expressive writing with pre-adolescents showed that more positive self-affirmation (e.g. positive personality traits and personal values) resulted in less anxiety over time (Niles et al., 2016). In relation to one’s own believes in coping, a study on expressive writing with adolescent girls showed that the participants described more adaptive and less maladaptive coping strategies after 3 sessions of writing about a personal problem (Vashchenko et al., 2007).

Based on the transactional model of stress and coping we expect that a positive affirmation of one’s coping abilities may positively influence how someone feels in relation to a negative event. However, the previous study (Vashchenko et al., 2007) did not confirm that asking people to write about coping strategies resulted in higher emotional well-being. In this study we will therefore examine how writing on the effectiveness of one’s coping strategies may explain the effects of a coping writing exercise on feelings in relation to a negative event.

We hypothesize that a writing instruction focused on coping (i.e. writing about previous experiences and how these are helpful to cope with the lockdown) may result in a higher positive change in feelings in relation to the lockdown due to COVID-19 pandemic after writing compared to a standard expressive writing condition (i.e. writing about one’s feelings in relation to a stressful event). Furthermore, we hypothesize that writing relatively more about the effectiveness of one’s coping strategies may mediate the positive effect of the positive writing instruction on change in feelings.

H3: A writing instruction on coping will result in a higher positive change in feelings in relation to the lockdown after writing compared to a standard expressive writing instruction (i.e. writing about one’s feelings in relation to a stressful event).

H4: The relative effectiveness of one’s coping strategies described in the narrative will mediate the relationship between a coping writing instruction and a positive change in feelings.

Given the instruction to write about positive aspects and previous successful coping efforts may result in writing about relatively more positive feelings too. The use of positive-emotion words was found to moderate the relation between writing about a positive experience and well-being (Burton and King, 2004). Previous research showed that writing about positive emotions more than about negative emotions may have a positive effect on one’s emotional well-being over time (Pennebaker and Seagal, 1999). On the contrary, using relatively more negative emotion words may have negative effects over time (e.g. more feelings of anxiety; Niles et al., 2016). We will therefore take the relative number of positive emotions into account as a third mediating variable in our analyses.

3 Materials and Methods

3.1 Participants

An online survey in Qualtrics was distributed amongst Flemish adolescents and young adults between 14 and 25 years old. The survey was distributed within the personal network of the researchers and posted on de webpages of two Flemish social support websites for adolescents and young adults. The sampling procedure further explained in the procedures resulted in a sample of 156 participants. The mean age of the participants was 20,19 (SD = 3,115). About 86% of all participants were female.

3.2 Procedure

Participants were asked to write about their experiences with the lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The study took place during the Belgian lockdown (approximately from the 14th of March to the fourth of May 2020), during which schools, cafés and restaurants were closed, organized sports and leisure activities were prohibited and social contacts were restricted to a maximum of four close contacts per household. In accordance with European legislation (FRA European union agency for fundamental rights, 2014) the ethical research committee of the University of Antwerp granted permission to collect data from adolescents aged 14 years or older without parental consent.

Research on expressive writing often asks participants to write about a personal recent or past traumatic experience, which results in a wide variety of narratives, both in context, content and emotionality (Travagin et al., 2015). Meta-analysis has shown that an expressive writing intervention is more effective when it concerns recent or “undisclosed” events which are still being emotionally processed by the writers (Frattaroli, 2006). In this research, participants needed to write about the same distressing situation which was a current undisclosed event. This allowed to keep the variances in the narratives to a minimum.

In a similar study on expressive writing, participants were asked to write on their experiences for 10 min or more (Green et al., 2017). Considering the online and voluntary nature of young people’s participation in this study, we preferred not to ask participants to write for 10 min or more, but instead, participants were asked to write at least 10 sentences in order to make sure that they wrote a narrative. Participants wrote on average 27,753 words (SD = 113.49 words). Only participants who wrote narratives counting 150 words (i.e. average number of words for 10 sentences) or more were taken into account. This resulted in a sample of 156 participants and narratives.

Two experimental expressive writing instructions were compared to a standard expressive writing instruction. The three conditions are shown below. In the first condition, which we will refer to as the “standard writing instruction,” a standard expressive writing instruction was presented. This instruction was adapted from Facchin et al. (2014) and translated into Dutch. Participants were asked to write about how they experienced the lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic, which emotions they felt, what their thoughts were and how they tried to deal with these emotions and thoughts. Since previous research already proved expressive writing instructions to be beneficial to writers’ well-being, this research mainly had the purpose to study the effect of adapted expressive writing instructions (positive or coping instruction) on change in emotions and the mediating effect of the specific content of writing.

In the second or “positive writing instruction” the participants were presented the same instructions as in the standard condition, but above that they were explicitly asked to focus on the positive aspects of the lockdown and which advantages it may have for them now and in the future. This condition was based on previous research on benefit-focused writing with adolescents (Facchin et al., 2014). In the third condition or “coping writing instruction” the participants were also presented a standard expressive writing instruction. Above that, they were asked to focus on previous experiences and how they may have taught them something that helps them to cope with the lockdown.

Before and after writing the participants needed to fill out questions on their emotions in relation to the lockdown to measure the change in feelings due to the writing instruction. Previous research on expressive writing found that writers may experience a significant lower positive emotions and more negative emotions after the writing instruction (Pennebaker and Seagal, 1999). In this study, we did not want to measure young people’s general mood, but rather their feelings in relation to the stressful situation.

Standard writing instruction: Write at least 10 sentences on how you experience the lockdown due to the coronavirus (How do you feel about it? What are your thoughts? How do you deal with these thoughts and emotions?). (Extra instruction for the experimental conditions is inserted here). It is very important that you write about your deepest feelings and thoughts. Take your time. Don’t worry about grammar and spelling. This story will remain confidential and will only be used for the purposes of this research.

Positive writing instruction: (…) Concentrate on the positive aspects (Which advantages does this situation have for you? Which advantages may it have in the future?). (…)

Coping writing instruction: (…) Concentrate on previous experiences and how they may have taught you something that is helpful to cope with this situation (What happened? How did you cope with thoughts and emotions? And how do these experiences help you now?). (…)

3.3 Measures

3.3.1 Change in Feelings in Relation to the Lockdown

A pre- and post-measure of positive and negative emotions in relation to the lockdown were assessed by means of a PANAS emotion scale. A comparable measurement was used in other research on expressive writing instructions (e.g. Green et al., 2017). The scale was introduced using the following sentence “What feelings do you currently experience regarding the lockdown due to the coronavirus?“. Participants needed to score 8 positive and 9 negative emotions on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely). The scales showed good reliability for both the pre-measure (α = 0.85) and post-measure of feelings (α = 0.85). The difference between feelings before and after writing was calculated and used as the dependent variable in part 1 and 3 of the analyses.

3.3.2 Relative Number of Positive Emotions, Positive Aspects and Effectiveness of One’s Coping Strategies

By means of a quantitative content analysis, we calculated the number of positive and negative emotions, positive and negative aspects of the lockdown and statements about the effectiveness and ineffectiveness of coping strategies participants wrote in their narratives. To identify coping strategies, we based our content analysis on the items in the brief COPE (Carver, 1997). Examples of the codes used for this quantitative analysis are listed in the Supplementary Material. Subsequently these scores were used to calculate three variables: the relative number of positive emotions, the relative number of positive aspects and relative effectiveness of coping strategies (e.g. number of positive emotions/number of negative emotions). These scores were coded on a scale from 1 to 10.

3.4 Data Analysis

First, we conducted a quantitative content analysis on the narratives emerging from the writing instructions (see Supplementary Material). This analysis was used to construct three relative content variables (see measures). Secondly, we used IBM SPSS Statistics Version 25 for all three parts of the quantitative analysis. In the first part of the quantitative analyses, we tested hypothesis 1 and 3 by means of an ANOVA analysis. In the second part of the analyses, we tested hypotheses 2 and 4 by means of mediation analysis in PROCESS (version 3.4.1) based on techniques developed by Hayes (2013). A mediation analysis not only shows how the writing instruction directly influences change in feelings as the dependent variable, but also the indirect effects of the writing instructions as a result of the precise contents of writing that affect change in feelings. Therefore our dependent variables are constructed as follows: positive or coping writing condition (1) and standard writing condition (0). Age was taken into account as a covariate in all analyses because of the understanding that emotional and cognitive resources to reflect effectively upon a distressing event may vary between young adolescence and young adulthood, which in turn may change the effectiveness of the writing instruction (Travagin et al., 2015; Taylor et al., 2016). Gender was not taken into account as a covariate, due to an uneven division between male and female participants.

4 Results

4.1 Manipulation Check

By means of a one-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), we first conducted a manipulation check for the experimental writing conditions. Pairwise comparisons between the three writing conditions revealed that narratives written in a positive writing condition scored higher on relative positive aspects than narratives written in the standard expressive writing condition (MD = 1.62, SD = 0.38, p < 0.001) and the coping writing condition (MD = 1.25, SD = 0.38, p < 0.010). Narratives written in the coping condition scored higher on previous experiences and coping efforts than narratives written in the standard condition (MD = 1.60, SD = 0.29, p < 0.001) and positive condition (MD = 1.47, SD = 0.31, p < 0.001). These differences confirm that the manipulations for the positive and the coping condition have worked.

4.2 Analyses Part 1: Investigating the Difference in Change in Feelings

To test hypothesis 1 and 3 we conducted an ANOVA analysis to measure the difference for change in feelings between the three writing instructions. Change in feelings was taken into account as the dependent variable. The conditions were included as a fixed factor (i.e. positive, coping and standard) and age as a covariate.

The mean score of feelings in relation to the lockdown before writing was 3.92 on a scale from 1 to 7 (SD = 0.85), reflecting that the situation was experienced as moderately stressful. The analysis found a significant difference for change in feelings between the three writing conditions [F (2,153) = 4.33, p < 0.050]. More precisely, the positive writing condition resulted in a higher positive change in feelings compared to the standard expressive writing condition (0.21, SD = 0.07, p < 0.010). Hypothesis 1 is therefore accepted. There was no statistically significant difference between the coping writing condition and the standard expressive writing condition (0.073, SD = 0.68, p = 0.29). Hypothesis 3 is therefore rejected. Age did not show a significant relation to change in feelings [F (2,153) = 1.66, p = 0.20].

4.3 Analyses Part 2: Mediation Analysis of the Conditions and Their Contents

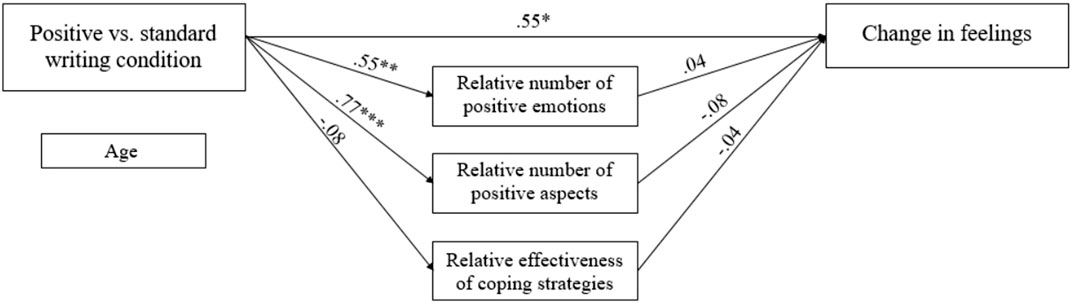

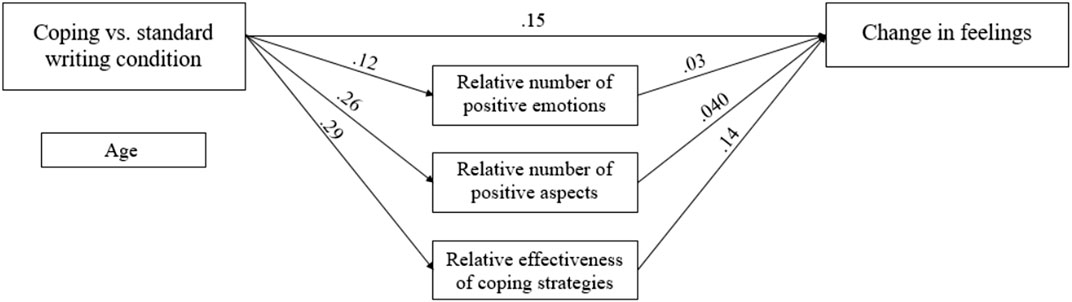

To test hypothesis 2 and 4, we used the macro PROCESS to estimate conditional indirect effects (Model 4–5,000 bootstrap intervals–BC 95% confidence intervals). Two mediation models are tested. The conditions (i.e. positive vs. standard and coping vs. standard writing condition) were taken into account as independent variables. Change in feelings was included as the dependent variable. Relative number of positive emotion words, relative number of positive aspects and relative effectiveness of coping were taken into account as mediating variables. The standardized results of these model can be viewed in Figures 1, 2.

A mediation model with the positive writing condition as the independent variable (positive writing condition = 1; standard writing condition = 0) found that there was a significant positive direct relationship between the positive writing condition and change in feelings (b = 0.546, S.E. = 0.09; BC 95% CI [0.05 to 0.39]). Relative number of positive emotions (b = 0.55, S.E. = 0.25; BC 95% CI [0.206 to 1.195]) and relative number of positive aspects (b = 0.77, S.E. = 0.40; BC 95% CI [0.84 to 2.43]) were significantly higher for the positive writing condition compared to the standard writing condition. Relative effectiveness of coping was not significantly different for the positive writing condition in comparison with the standard writing condition (b = −0.08, S.E. = 0.14; BC 95% CI [−0.34 to 0.22]). Age was not related to the relative content variables, nor to change in feelings. There was no direct relationship between the relative number of positive emotions (b = 0.04, S.E. = 0.04; BC 95% CI [−0.06 to 0.09]), positive aspects (b = −0.077, S.E. = 0.02; BC 95% CI [−0.06 to 0.03]) or effectiveness of coping (b = −0.04, S.E. = 0.06; BC 95% CI [−0.13 to 0.09]) and change in feelings. Thus, the positive relationship that was found for the positive writing condition and change in feelings was not mediated by either of these relative content variables, and therefore also not by relative number of positive aspects. Hypothesis 2 is therefore rejected.

A mediation model with the coping writing condition as the independent variable (coping writing condition = 1; standard writing condition = 0) found that there was no significant relationship between the coping writing condition and change in feelings (b = 0.15, S.E. = 0.07; BC 95% CI [−0.08 to 0.19]). Relative number of positive emotions (b = 0.12, S.E. = 0.20; BC 95% CI [−0.28 to 0.53]), relative number of positive aspects (b = 0.258, S.E. = 0.27; BC 95% CI [−0.18 to 0.91]) and relative effectiveness of coping (b = 0.29, S.E. = 0.03; BC 95% CI [−0.08 to 0.64]) were not significantly different for the coping writing condition in comparison with the standard writing condition. Age was not related to the relative content variables, nor to change in feelings. There was no relationship between the relative number of positive emotions (b = 0.03, S.E. = 0.04; BC 95% CI [−0.07 to 0.09]), positive aspects (b = 0.04, S.E. = 0.03; BC 95% CI [−0.04 to 0.06]) or effectiveness of coping (b = 0.141, S.E. = 0.04; BC 95% CI [−0.02 to 0.13]) and change in feelings. Thus, the content of writing of the coping writing did not mediate the effect on change in feelings. Hypothesis 4 is therefore rejected.

5 Discussion

5.1 General Discussion

Starting from the transactional model of stress and coping and expressive writing theory, this research aimed to investigate whether writing instructions focused on changing young people’s appraisals of a stressful situation may affect their emotional reactions towards the situation at hand. In an online experiment, participants were asked to write about their experience with the Belgian lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic in one of three conditions: a standard expressive writing instruction (writing about one’s emotions and thoughts in relation to the lockdown and one’s coping strategies); a positive writing instruction (writing about the positive aspects of the lockdown); and a coping writing instruction (writing about previous experiences and how these are helpful to cope with the lockdown). Participants’ positive and negative feelings in relation to the lockdown were measured before and after the writing instruction to measure change in feelings.

The mediation analysis for the comparison between the positive writing condition and the standard writing condition showed that the positive writing instruction was associated with a higher increase in positive feelings compared to the standard writing condition. However, the analysis did not show a mediating effect of the relative content variables. The difference in change in feelings between the writing conditions could therefore not be explained by the content of writing. In other words, the positive writing condition seemed to occur with a relatively higher increase in positive emotions compared to the other writing conditions, regardless of the actual content of writing by the participants. This was not in correspondence with previous research, which suggested that a high number of positive-emotion words and a moderate number of negative-emotion words results in a higher positive change in well-being outcomes (Pennebaker and Seagal, 1999). Age did not have a significant effect on the effectiveness of the positive writing instruction, nor the actual content of writing. In other words, instructing young people to write about the positive aspects and consequences of a stressful event could be equally beneficial to both younger adolescents’ as young adults’ emotional well-being.

There may be different explanations to the positive relationship between the positive writing instruction and positive change in emotions and the absence of a mediation effect of the content of writing. First, there may be other mediating variables that we have missed out in this study. Previous research for example already found that the use of cognitive words mediated the positive effect of a positive writing instruction compared to a standard expressive writing instruction (McCullough et al., 2006). Secondly, the instruction itself may already have elicited a positive change in emotions. Our society teaches us that optimism—or focusing on the positive—is an effective coping strategy and will always yield more positive results than pessimism - or focusing on the negative. Possibly the instruction itself may have triggered a positive expectation with participants so that the actual content of writing did not make a difference anymore. At last, the positive change in emotions may not result from writing about the positive aspects of the lockdown, but rather from not writing about the negative aspects of the lockdown. It is possible that merely by trying to come up with positive aspects and consequences may as a result leave less space to focus on the negative aspects (as well as the negative emotions that result from it) which in turn will buffer against the negative effects of focusing on the negative.

The mediation analysis for the comparison between the coping writing condition and the standard writing condition did not show a difference in change in feelings. Although the manipulation check revealed that there were significant differences in the content of writing for both writing conditions, the content of writing could not explain the absence of a difference in change in feelings. This may be due to the fact that all writing conditions instructed participants to reflect on their coping strategies and that an additional instruction to reflect on previous experiences and how these may help to deal with the lockdown may not have made a difference. This matter is further discussed in the limitations.

5.2 Limitations and Further Research

This research also has some limitations that need to be discussed. In relation to the sample, we could not control for gender differences in the effects of writing due to an uneven division in male and female participants. Emotional regulation through writing may have different effects for boys and girls. The sample size was relatively small and may not have represented all young people between the ages of 14 and 25 years old. Further research should ensure an even division in gender and a more representative sample.

Our interest in young people’s coping strategies in relation to the lockdown have lead us to ask participants in all three expressive writing instructions to write about their coping strategies. This may have caused the differences between the coping writing instruction (i.e. writing about previous experiences and how these are helpful to cope with the lockdown) and the standard expressive writing condition to be non-significant. Moreover, writing on previous experiences may still have been hard for the youngest in our sample (14–15 year old adolescents), who generally do not have as much life experience as the oldest in our sample (24–25 year old young adults). Writing about coping strategies in relation to the lockdown would have been an interesting experimental writing condition on itself. Further studies should research whether writing about coping strategies could result in positive effects on one’s feelings or coping self-efficacy in relation to a stressful event.

Research on expressive writing often includes a follow-up measure of the dependent variable days or weeks after the initial study to measure whether the effects of the writing instruction last in the long term. Because of the anonymous and online nature of this study, we could not include a follow-up measure.

At last, due to time limitation the writing instructions presented in this study were not tested within the controlled environment of a social support website. Therefore we can only make assumptions on the applicability of these writing instructions in this context. Further research should study the effects of similar writing instructions as well as the acceptability of this feature with users within an existing or a fictitious social support website for young people. Examples on these kind of study designs can be found in literature on communication studies (e.g. Kim and Shyam Sundar, 2014; Kim and Sundar, 2015; Kim et al., 2018) and psychology (O’Leary et al., 2018; Andalibi and Flood, 2021; Smith et al., 2021).

Communication studies on this theme are generally more focused on the precise medium’s affordances or interface cues that have psychological correlates which mediate users’ engagement with the medium and its content. In this way, communication studies can explain why a certain feature of the medium, in the form that it is presented, works. Studies on this theme in psychology are generally more attentive to vulnerable groups and therefore in addition focus on the practical feasibility and acceptability of the mediums features by its users. Psychological studies therefore can tell under which circumstances and for whom a certain feature is most desirable. Further studies should try to combine both perspectives when researching the affordances and interface features of social support websites.

5.3 Practical Implications

Online and offline interventions for young people during the COVID-19 pandemic could focus on helping young people to see the positive in their experiences in order to change young people’s emotional reactions towards the situation. On the basis of this study, we recommend to encourage young writers on social support websites to focus more on the positive aspects and consequences of a stressful event. Expressive writing instructions as were used in this study may be a good starting point.

If writing instructions seem too intrusive, another possibility is to present users with a prompt after they have written their personal narrative. For example, before posting a pop-up message may stimulate writers to revise their personal narrative: “It might be helpful to not only reflect on the negative, but also on the positive. Are there positive aspects and consequences to the situation that you did not think of before? If so, you can still add these to your narrative if you want.” Both in the case of writing instructions and prompts, it may be advisable to explain to users why more positive narratives may be helpful to readers as well. For example: “Readers may be looking for the positive notes in your narrative. This may help them to reflect on their own experiences in a more positive way as well.” This may possibly motivate users to follow the advice by the website.

Although reflecting on the positive sides of a negative experience may be more effective to young people’s well-being, social support websites still need to stay a space on which young people can share the negative without too many restrictions. The suggestions made in this study do not have the intention to restrict young people in their personal emotional expression. More research is needed to test the acceptability of these features with users in the controlled environment of a social support website.

Conclusion

In times of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, young people may turn to social support websites to find support with similar others. Young people’s tendency to focus on the negative aspects of their experiences may put them at risk for increased negative emotions and co-rumination. More research is needed on how writing about a stressful event in an online context may relate to young people’s emotional reactions towards a stressful event. Moreover, it is important to find ways to improve young people’s reflections upon distressing events on these websites.

Applying the transactional model of stress and coping and expressive writing theory to the context of social support websites, this study found that an expressive writing instruction focused on positive aspects and consequences may be an effective strategy to help young people to change their emotional reactions towards a stressful event, in this case a lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, the positive relationship that was found in this study was not mediated by the precise content of writing (i.e. relative positive emotions, positive aspects and effectiveness of coping strategies). A possible explanation may be that the instruction itself may already have elicited a positive effect, resulting from the expectation that optimism is an effective coping strategy and is always rewarded. It is also possible that discussing positive aspects and consequences to a stressful event leaves less space to focus on the negative aspects and consequences which may buffer against possible negative effects on emotions.

Online and offline interventions for young people during the COVID-19 pandemic could focus on helping young people to see the positive in their experiences in order to change young people’s emotional reactions towards the situation. On the basis of this study, we recommend to encourage young people on social support websites to focus more on the positive consequences and less on the negative consequences of a stressful event by means of specific writing instructions, prompts or other interface adaptations.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available the data are based on sensitive personal narratives written by minors. Therefore the data are not publicly accessible and not available by request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The ethical research committee of the University of Antwerp granted permission to conduct this study. In accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements, there was no written consent from legal guardians required for minors 14 year and older to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

SM, PhD researcher: Research project conception, data collection, data analysis, discussion about article conceptualization, first draft preparation, reviewing and editing of final drafts. KP and HV, full professors: Research project conception, discussion about article conceptualization and editing of first drafts. These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Council of the University of Antwerp (The use of online personal narratives to improve adolescents’ coping with psychological distress, BOF-DOCPRO 2018, 36938).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.755896/full#supplementary-material

References

Ali, K., Farrer, L., Gulliver, A., and Griffiths, K. M. (2015). Online Peer-To-Peer Support for Young People with Mental Health Problems: A Systematic Review. JMIR Ment. Health 2 (2), e19. doi:10.2196/mental.4418

Andalibi, N., and Flood, M. K. (2021). Considerations in Designing Digital Peer Support for Mental Health: Interview Study Among Users of a Digital Support System (Buddy Project). JMIR Ment. Health 8 (1), e21819. doi:10.2196/21819

Batenburg, A., and Das, E. (2015). Virtual Support Communities and Psychological Well-Being: The Role of Optimistic and Pessimistic Social Comparison Strategies. J. Comput-Mediat Comm. 20 (6), 585–600. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12131

Ben-Zur, H. (2019). “Transactional Model of Stress and Coping,” in Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Editors V. Zeigler-Hill, and T. K. Shackelford (Springer International Publishing), 1–4. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_2128-1

Burton, C. M., and King, L. A. (2004). The Health Benefits of Writing about Intensely Positive Experiences. J. Res. Personal. 38 (2), 150–163. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00058-8

Carver, C. S. (1997). You Want to Measure Coping but Your Protocol’ Too Long: Consider the Brief Cope. Int. J. Behav. Med., 4 (1), 92. doi:10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6

Choi, M., and Toma, C. L. (2014). Social Sharing through Interpersonal media: Patterns and Effects on Emotional Well-Being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 36, 530–541. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.026

De Maeseneer, W. (2020). TV-gezicht James Cooke Lanceert Digitaal Jongerenplatform Om Taboes Bespreekbaar Te Maken: ‘Schooltelevisie 2.0’ [TV Personality James Cooke Launches Digital Youth Platform to Discuss Taboos: 'School TV 2.0']. VRT NWS. Retrieved from: https://www.vrt.be/vrtnws/nl/2020/10/21/educatief-platform-edtv/. (Accessed October 28, 2020).

Duprez, C., Christophe, V., Rimé, B., Congard, A., and Antoine, P. (2015). Motives for the Social Sharing of an Emotional Experience. J. Soc. Person. Relation., 32 (6), 757–787. doi:10.1177/0265407514548393

Facchin, F., Margola, D., Molgora, S., and Revenson, T. A. (2014). Effects of Benefit-Focused versus Standard Expressive Writing on Adolescents' Self-Concept during the High School Transition. J. Res. Adolesc. 24 (1), 131–144. doi:10.1111/jora.12040

FRA European union agency for fundamental rights (2014). Child Participation in Research. Fra.europa.eu. Available at: https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2019/child-participation-research#publication-tab-0 (Accessed October 28, 2020).

Frattaroli, J. (2006). Experimental Disclosure and its Moderators: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 132 (6), 823–865. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.823

Frison, E., Bastin, M., Bijttebier, P., and Eggermont, S. (2019). Helpful or Harmful? the Different Relationships between Private Facebook Interactions and Adolescents' Depressive Symptoms. Media Psychol. 22 (2), 244–272. doi:10.1080/15213269.2018.1429933

Green, M. C., Kaufman, G., Flanagan, M., and Fitzgerald, K. (2017). Self-esteem and Public Self-Consciousness Moderate the Emotional Impact of Expressive Writing about Experiences with Bias. Personal. Individ. Differ. 116, 212–215. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.057

Greenaway, K. H., Louis, W. R., Parker, S. L., Kalokerinos, E. K., Smith, J. R., and Terry, D. J. (2015). “Measures of Coping for Psychological Well-Being,” in Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Constructs. Editors G. J. Boyle, D. H. Saklofske, and G. Matthews (Academic Press), 322–351. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-386915-9.00012-7

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press, xvii–507.

Kim, H.-S., and Shyam Sundar, S. (2014). Can Online Buddies and Bandwagon Cues Enhance User Participation in Online Health Communities? Comput. Human Behav. 37, 319–333. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.039

Kim, H.-S., and Sundar, S. S. (2015). Motivating contributions to online forums: Can locus of control moderate the effects of interface cues? Health Communication. doi:10.1080/10410236.2014.981663

Kim, J., Gambino, A., Sundar, S. S., Rosson, M. B., Aritajati, C., Ge, J., et al. (2018). Interface Cues to Promote Disclosure and Build Community: An Experimental Test of Crowd and Connectivity Cues in an Online Sexual Health Forum. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact., 2(CSCW) 90, 1-90:18. doi:10.1145/3274359

Kramer, A. D. I., Guillory, J. E., and Hancock, J. T. (2014). Experimental Evidence of Massive-Scale Emotional Contagion Through Social Networks. Proc. Nation. Acad. Sci. 111 (24), 8788–8790. doi:10.1073/pnas.1320040111

Lawlor, A., and Kirakowski, J. (2014). Online Support Groups for Mental Health: A Space for Challenging Self-Stigma or a Means of Social Avoidance? Comput. Human Behav. 32, 152–161. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.11.015

Lazarus, R., and Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company, Inc.

Lichtenthal, W. G., and Cruess, D. G. (2010). Effects of Directed Written Disclosure on Grief and Distress Symptoms Among Bereaved Individuals. Death Stud. 34 (6), 475–499. doi:10.1080/07481187.2010.483332

Ma, H., Smith, C. E., He, L., Narayanan, S., Giaquinto, R. A., Evans, R., et al. (2017). Write for Life: Persisting in Online Health Communities through Expressive Writing and Social Support. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 1 (CSCW), 1–24. doi:10.1145/3134708

Magson, N. R., Freeman, J. Y. A., Rapee, R. M., Richardson, C. E., Oar, E. L., and Fardouly, J. (2021). Risk and Protective Factors for Prospective Changes in Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Youth Adolesc. 50 (1), 44–57. doi:10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9

McCullough, M. E., Root, L. M., and Cohen, A. D. (2006). Writing about the Benefits of an Interpersonal Transgression Facilitates Forgiveness. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 74 (5), 887–897. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.887

Niles, A. N., Byrne Haltom, K. E., Lieberman, M. D., Hur, C., and Stanton, A. L. (2016). Writing Content Predicts Benefit from Written Expressive Disclosure: Evidence for Repeated Exposure and Self-Affirmation. Cogn. Emot. 30 (2), 258–274. doi:10.1080/02699931.2014.995598

O'Leary, K., Schueller, S. M., Wobbrock, J. O., and Pratt, W. (2018). “"Suddenly, We Got to Become Therapists for Each Other": Designing Peer Support Chats for Mental Health,” in Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, April 21, 2018, 1–14. doi:10.1145/3173574.3173905

Pennebaker, J. W., and Seagal, J. D. (1999). Forming a story: The Health Benefits of Narrative. J. Clin. Psychol. 55 (10), 1243–1254. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199910)55:10<1243:AID-JCLP6>3.0.CO;2-N

Pennebaker, J. W. (2004). Theories, Therapies, and Taxpayers: On the Complexities of the Expressive Writing Paradigm. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 11 (2), 138–142. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bph063

Prescott, J., Hanley, T., and Ujhelyi Gomez, K. (2019). Why Do Young People Use Online Forums for Mental Health and Emotional Support? Benefits and Challenges. Br. J. Guidance Counselling 47 (3), 317–327. doi:10.1080/03069885.2019.1619169

Rains, S. A., and Young, V. (2009). A Meta-Analysis of Research on Formal Computer-Mediated Support Groups: Examining Group Characteristics and Health Outcomes. Hum. Commun. Res. 35 (3), 309–336. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2009.01353.x

Rains, S. A., Peterson, E. B., and Wright, K. B. (2015). Communicating Social Support in Computer-Mediated Contexts: A Meta-Analytic Review of Content Analyses Examining Support Messages Shared Online Among Individuals Coping with Illness. Commun. Monogr. 82 (4), 403–430. doi:10.1080/03637751.2015.1019530

Rains, S. A., and Wright, K. B. (2016). Social Support and Computer-Mediated Communication: A State-of-the-Art Review and Agenda for Future Research. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 40 (1), 175–211. doi:10.1080/23808985.2015.11735260

Rimé, B., Bouchat, P., Paquot, L., and Giglio, L. (2020). Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, and Social Outcomes of the Social Sharing of Emotion. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 31, 127–134. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.08.024

Rose, A. J. (2002). Co–Rumination in the Friendships of Girls and Boys. Child Develop. 73 (6), 1830–1843. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00509

Schouten, A. P., Valkenburg, P. M., and Peter, J. (2007). Precursors and Underlying Processes of Adolescents' Online Self-Disclosure: Developing and Testing an "Internet-Attribute-Perception" Model. Media Psychol. 10 (2), 292–315. doi:10.1080/15213260701375686

Shanahan, L., Steinhoff, A., Bechtiger, L., Murray, A. L., Nivette, A., Hepp, U., et al. (2020). Emotional Distress in Young Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence of Risk and Resilience from a Longitudinal Cohort Study. Psychol. Med., 1–10. doi:10.1017/S003329172000241X

Skinner, E. A., and Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2016). The Development of Coping. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Smith, C. E., Lane, W., Hillberg, H. M., Kluver, D., Terveen, L., and Yarosh, S. (2021). Effective Strategies for Crowd-Powered Cognitive Reappraisal Systems: A Field Deployment of the Flip*Doubt Web Application for Mental Health. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 5, 37. doi:10.1145/3479561

Smyth, J. M. (1998). Written Emotional Expression: Effect Sizes, Outcome Types, and Moderating Variables. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 66 (1), 174–184. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.17410.1037//0022-006x.66.1.174

Taylor, E., Jouriles, E. N., Brown, R., Goforth, K., and Banyard, V. (2016). Narrative Writing Exercises for Promoting Health Among Adolescents: Promises and Pitfalls. Psychol. Viol. 6, 57–63. doi:10.1037/vio0000023

Torbeyns, A. (2020). Jongeren Hebben Nauwelijks Nog Ruimte Om Te Ventileren [Young People Hardly Have Room to Vent Anymore]. De Standaard. Retrieved from: https://www.standaard.be/cnt/dmf20200428_04937832 (Accessed December 7, 2021).

Travagin, G., Margola, D., and Revenson, T. A. (2015). How Effective Are Expressive Writing Interventions for Adolescents? A Meta-Analytic Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 36, 42–55. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.003

Vashchenko, M., Lambidoni, E., and Brody, L. R. (2007). Late Adolescents' Coping Styles in Interpersonal and Intrapersonal Conflicts Using the Narrative Disclosure Task. Clin. Soc. Work J. 35 (4), 245–255. doi:10.1007/s10615-007-0115-3

Vermeulen, A., Vandebosch, H., and Heirman, W. (2018). #Smiling, #venting, or Both? Adolescents' Social Sharing of Emotions on Social Media. Comput. Hum. Behav. 84, 211–219. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.022

Yang, Q. (2018). Understanding Computer-Mediated Support Groups: A Revisit Using a Meta-Analytic Approach. Health Commun. 35, 209–221. doi:10.1080/10410236.2018.1551751

Keywords: coping, COVID-19 pandemic, emotional well-being, expressive writing, narrative, social support, young people

Citation: Mariën S, Poels K and Vandebosch H (2022) Think Positive, be Positive: Expressive Writing Changes Young People’s Emotional Reactions Towards the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Educ. 6:755896. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.755896

Received: 09 August 2021; Accepted: 17 December 2021;

Published: 01 February 2022.

Edited by:

Angela Mazzone, Dublin City University, IrelandReviewed by:

Estelle Smith, University of Colorado Boulder, United StatesMavadat Saidi, Shahid Rajaee Teacher Training University, Iran

Copyright © 2022 Mariën, Poels and Vandebosch. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sofie Mariën, c29maWUubWFyaWVuQHVhbnR3ZXJwZW4uYmU=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Sofie Mariën

Sofie Mariën Karolien Poels

Karolien Poels Heidi Vandebosch†

Heidi Vandebosch†