- 1Center for Education Integrating Science, Mathematics, and Computing, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, United States

- 2Department of Educational Studies, St. Mary’s College of Maryland, St. Mary’s City, MD, United States

Although teaching self-efficacy is associated with many benefits for teachers and students, little is known about how teachers develop a sense of efficacy in the early years of their careers. Drawing on survey (N = 179) and interview (N = 10) data, this study investigates the sources of self-efficacy in a national sample of teachers who participated in the Noyce program. All teachers completed an online survey that included both the Teacher Sense of Efficacy Instrument and open-ended items prompting them to reflect on the sources of their self-efficacy. Ten teachers participated in semi-structured follow-up interviews. Enactive mastery experiences were the most common source of self-efficacy identified by teachers, followed by social persuasions and vicarious experiences. Physiological and affective states were identified infrequently and more often related to negative experiences that lowered self-efficacy than to positive experiences. Beginning teachers identified more negative enactive experiences than either Novice (2–3 years experiences) or Career teachers. In interviews, teachers described how the sources combined or interacted to influence their self-efficacy. Findings contribute to better understandings of the sources of self-efficacy with implications for how best to support teachers at different stages of their careers.

Introduction

As researchers have sought to understand factors influencing teacher effectiveness, many have explored teaching self-efficacy, defined as the teachers’ beliefs about their capability to carry out the professional tasks of teaching (Tschannen-Moran and Hoy, 2001). Research conducted over several decades provides a growing body of evidence linking teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs to the quality of instruction, student achievement, and student motivation (Klassen and Tze, 2014; Klassen et al., 2011; Zee and Kooman, 2016). In their synthesis of 165 studies of teaching self-efficacy, Zee and Kooman (2016) found associations between positive teaching self-efficacy and students’ academic outcomes, patterns of teacher behavior and practices related to classroom quality. Moreover, teaching self-efficacy has been shown to be related to factors underlying teachers’ psychological well-being. Teachers who believe in their capabilities tend to be more satisfied, more committed to the profession and less susceptible to burnout (Brown, 2012; Aloe et al., 2014; Chesnut and Burley, 2015; Zee and Kooman, 2016). Thus, by understanding teaching self-efficacy and how it develops over the course of teachers’ careers, researchers and practitioners gain insight into a powerful influence on outcomes at both the classroom and individual teacher levels.

Given the benefits of a healthy teaching self-efficacy, scholars have called for research exploring the sources of these beliefs (Klassen et al., 2011; Morris et al., 2017). What types of information, experiences, and interactions shape teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs? In his social cognitive theory, Bandura (1997) hypothesized that individuals interpret information from four sources when evaluating their self-efficacy: 1) enactive mastery experiences, which involve attainment of goals through direct action; 2) vicarious experiences, which occur through an observation of a model (or oneself) completing a task, 3) social persuasions, which consist of messages from others, and tend to differentially influence self-efficacy based on the contents of the feedback and the perceived standing of the person providing the feedback; and 4) physiological and affective states like mood, stress, and anxiety. It is important to note that sources of information can be combined when making judgments about self-efficacy. For example, individuals draw on both direct and vicarious experiences when they make referential comparisons to a perceived group norm.

Enactive mastery experiences, which involve the attainment of goals through direct action, are typically the most potent source of self-efficacy and are especially powerful when an individual accomplishes a task they view as demanding (Bandura, 1997). When teachers perceive their teaching as successful, they are likely to believe in their instructional capabilities. Likewise, when teachers perceive that they have been unsuccessful, they may doubt their teaching ability. Vicarious experiences involve observing a model perform a task and can be a particularly powerful source of self-efficacy when a task is still novel and when the model being observed is perceived as similar to oneself. Thus, teaching efficacy beliefs may be most influenced by vicarious experiences in the earliest stages of teachers’ careers when many teaching tasks are still novel. Social persuasions in the form of evaluative feedback represent another source of self-efficacy beliefs. The influence of feedback depends, in part, on the degree to which the person offering feedback is considered credible and sincere. Teaching self-efficacy may be unaffected by “empty praise” or feedback from observers for whom teachers have little trust or respect. Bandura (1997) also suggested that self-efficacy beliefs are more easily altered by negative feedback than by positive feedback. Self-efficacy may also be informed by physiological and affective states including mood, anxiety, and stress.

The Sources of Teaching Self Efficacy

Attempts to study the sources of teaching self-efficacy have been somewhat limited in scope (Klassen et al., 2011; Morris et al., 2017). In their review of research on the sources of teachers’ self-efficacy, Morris et al. (2017) described a number of limitations in this body of work. Rather than direct measures of the sources of teachers’ self-efficacy, many researchers have used elements of teacher education or professional development experiences as proxies for the four hypothesized sources in quantitative studies. When direct measures have been used, they have often been inconsistent with Bandura (1997) descriptions. For instance, many researchers operationalized mastery experiences as the quantity of teaching experiences (e.g., years teaching, opportunities for teaching) or affective appraisals, such as rating of overall satisfaction with performance. Few scholars have examined how teachers interpret the actual outcomes of their direct actions (e.g., enactive experiences) when evaluating their self-efficacy. Qualitative research typically provides more detailed accounts of the sources of teachers’ self-efficacy, yet relatively few researchers have asked teachers to describe how particular teaching experiences influence their self-efficacy. Morris et al. (2017) also noted that less research has been devoted to sources outside of mastery experiences and that few studies have been designed to assess all four sources. One exception is a recent cross-cultural study by Yada et al. (2019) that explored the sources of self-efficacy among Japanese and Finnish teachers. Consistent with previous research, this study found that in both countries, mastery experiences were the strongest contributor to self-efficacy. Interestingly, Japanese and Finnish teachers differed in how verbal persuasions predicted self-efficacy and other sources were identified as influencing Japanese teachers’ self-efficacy. A final limitation had to do with the samples used in these studies; the studies more often focused on preservice teachers than practicing teachers, and the majority of participants taught at the elementary or early childhood level. This is notable given evidence that teachers’ self-efficacy and levels of stress differ for practicing and secondary teachers (Geving, 2007; Rots et al., 2007; Wolters and Daugherty, 2007; Klassen and Chiu, 2011).

Self-Efficacy and Teacher Experience

The relationship between the teaching experience level and self-efficacy remains unclear. In large-scale studies, bivariate correlations between years of teaching experience and self-efficacy tend to be nonsignificant or weak (e.g., Kim and Burić, 2020; Tschannen-Moran and Johnson, 2011). However, in a longitudinal study, George et al. (2018) found that teachers’ self-efficacy increased across all dimensions of self-efficacy as they progressed from their first to fifth year of teaching. Similarly, in their large-scale cross-sectional study, Wolters and Daugherty (2007) found that teachers with more experience reported higher self-efficacy. Conversely, teachers with low self-efficacy early in their careers may be more inclined to leave the profession (Hong, 2012). Klassen and Chiu (2010), on the other hand, identified a curvilinear relationship between teaching experience and self-efficacy across 1,430 practicing teachers. Across all dimensions, teaching self-efficacy peaked at approximately 23 years of experience before declining. They speculated that this decline in the later years – which may explain the overall weak correlations between experience and self-efficacy – may be due to the loss of enthusiasm Huberman (1989) described toward the end of a teaching career.

Few scholars have explored differences in teachers’ self-efficacy at different points in their careers, and the existing research has been undermined by problematic measures. Research from teacher education and professional development programs indicates that learning pedagogical skills and having a chance to apply them in an authentic setting can improve self-efficacy (Tschannen-Moran and McMaster 2009; Bruce et al., 2010). Pfitzner-Eden (2016) reported that mastery experiences were strong predictors of changes in self-efficacy for preservice teachers who had completed a teaching practicum but not for those who had only engaged in an observation practicum. However, mastery experiences in the study were assessed as general appraisals of success rather than the accomplishment of instructional goals. Consistent with Morris et al. (2017) description of the development of self-efficacy, these general appraisals mediated the relationship between other sources and teaching self-efficacy. As such, the inclusion of the variable obscured the direct contribution of the other sources to teaching self-efficacy.

Research on preservice teachers’ experiences may offer clues as to how teachers develop a sense of efficacy once employed. In their longitudinal study, Woolfolk Hoy and Burke-Spero (2005) found that teachers’ self-efficacy rose during their teacher education program but declined after their first year of teaching. Individuals may draw on different sources of information in evaluating their instructional capabilities as they leave teacher education and begin working in schools. Such a transition involves a change in context and more opportunities to perform instructional tasks, both of which can alter the relative potency of the sources (Bandura, 1997). This can lead to seemingly contradictory findings when making comparisons across groups. For example, Klassen and Chiu (2011) reported that practicing teachers were more likely than preservice teachers to report that teaching was stressful, but had higher self-efficacy for classroom management.

Little is known about how the sources of teaching self-efficacy differ for practicing teachers at different stages in their careers. In interview studies, mastery experiences and social persuasions have emerged as powerful sources during instructors’ early experiences (Mulholland and Wallace, 2001; Morris and Usher, 2011). These were often intertwined; given that there are few objective markers of mastery in teaching, perceptions that instructional goals are achieved were confirmed by the social appraisals of others. Woolfolk Hoy and Burke-Spero (2005) reported that affective appraisals of success (i.e., satisfaction with past performance) and perceived support from others were positively associated with changes in self-efficacy during the first year of teaching. However, teachers’ referential comparisons, in which they evaluated their success against their colleagues’, had no such influence, perhaps due to the lack of opportunities to observe others once hired. Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy (2007) compared novice teachers (≤3 years of experience) to career teachers (>4 years of experience) using similar measures of support and satisfaction with instructional performance. In this study, career teachers reported higher self-efficacy for instructional strategies and classroom management. For both groups, satisfaction with performance predicted their teaching self-efficacy. However, overall perceptions of interpersonal support predicted self-efficacy only for career teachers, and the support of colleagues and community negatively predicted novice teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs. Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy (2007) suggested that this may reflect the tendency of struggling new teachers to seek out support from others.

Whereas these findings offer a glimpse into the development of teaching self-efficacy, they also lead to more to questions than answers. Namely, what are the actual sources of teachers’ beliefs? The purpose of this study is to begin to develop such understandings about the sources of self-efficacy among a population of teachers participating in the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Noyce Scholarship program. Two research questions guided the study:

1) What sources of self-efficacy are identified by Noyce teachers?

2) How do self-efficacy and the sources of self-efficacy vary according to Noyce teachers’ experience levels?

Methods

This study, which is one strand of a larger research program focused on Noyce teachers, follows an explanatory sequential design (Creswell and Clark, 2017) in which qualitative data were collected to develop a deeper understanding of survey findings. Specifically, interviews were utilized to further describe and explore the sources of self-efficacy and possible interconnections among teacher experience, self-efficacy and the sources of self-efficacy.

Participants

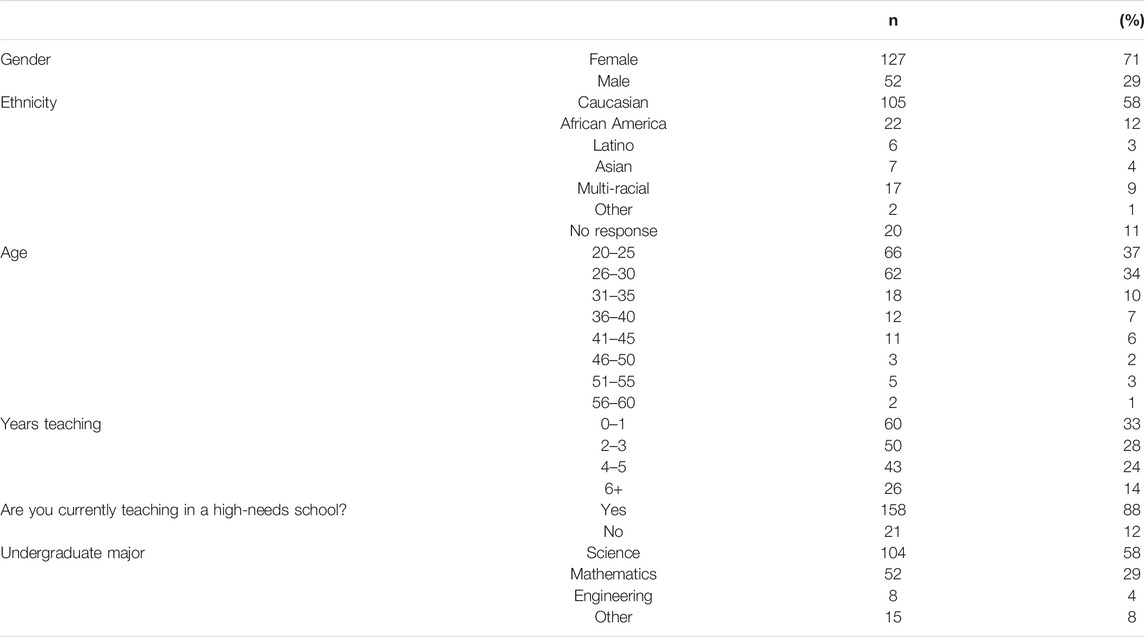

Survey participants were 179 teachers who have participated in the Robert Noyce Teacher Scholarship program (“the Noyce program”). The Noyce program provides grants to university-based teacher education programs seeking to recruit and support STEM majors and professionals as K-12 teachers in high-need school districts. The Noyce program defines high-need districts with schools in which the majority of students are eligible for free and reduced price lunch programs, greater than 34% of teachers do not have a degree in the field in which they teach, and/or there is a teacher attrition rate over 15 percent for the previous three school years. Researchers compiled a database of Noyce programs and sent emails to each program inviting them to forward study information to teachers who had completed their program within the last 5 years. This email recruitment strategy resulted in a sample of teachers representing 47 Noyce programs in 30 states. As the larger study for which survey data were collected focuses on recent Noyce participants, the majority of survey participants (n = 153) are considered “early career” teachers who have been full-time classroom teachers for 5 years or less. In order to ascertain variations in self-efficacy according to teachers’ experience levels, the current study divides the survey sample into three groups: “Beginning Teachers” in their first year of teaching (n = 60), “Novice Teachers” with 2–3 years of teaching experience (n = 50), and “Career Teachers” with at least 4 years of teaching experience (n = 69). See Table 1 for survey participant demographics.

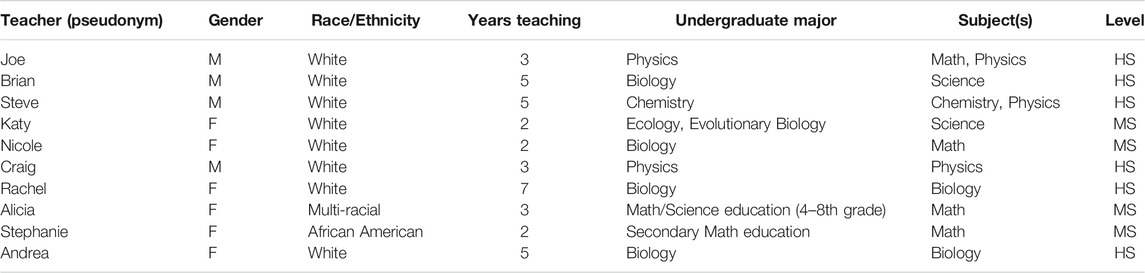

A purposive sample of interview participants (n = 10) was recruited from a pool of survey participants indicating willingness to participate in a follow-up interview. Using a maximum variation strategy (Miles et al., 2019), the research team selected interview participants representing a range of experience and self-efficacy levels and, to the extent possible, a sample balanced with regard to subject area (math or science), teaching level (middle or high school), and gender. Note that because interview participants were recruited from the sample of teachers completing the survey the previous year, the interview sample does not include beginning teachers in their first year teaching. To protect participant confidentiality, all interview participants are identified using pseudonyms. See Table 2 for interview participant demographics.

Data Sources

Survey

The survey was administered online to Noyce teachers during the second half of the academic school year. As described below, the survey included a self-efficacy scale and open-ended items prompting teachers to reflect on the sources of their self-efficacy. Teachers were also asked to provide demographic data (age, gender, race/ethnicity), information on their teaching experience (years of teaching experience, subject taught, level taught), and educational background (undergraduate major).

The Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy Scale

Tschannen-Moran and Hoy (2001) Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy Scale (TSES) was utilized to measure self-efficacy beliefs. The TSES asks teachers to rate their agreement with self-efficacy items along a 9-point continuum (with anchors at 1 - Nothing, 3- Very Little, 5 - Some Influence, 7 - Quite A Bit, 9 - A Great Deal). It includes three subscales measuring teachers’ self-efficacy for instructional strategies, classroom management, and student engagement. The TSES has been widely utilized and is generally accepted as a valid and reliable measure of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs (Klassen et al., 2011; Zee and Koomen, 2016). Because teachers were completing the TSES as part of a much longer survey, this study used the twelve-item short form of the instrument. Tschannen-Moran and Hoy (2001) reported strong evidence of construct validity and reliability values (alphas) of 0.90 and for each of the subscales ranging from 0.81 to 0.86.

Open-Ended Items

Following the TSES, two open-ended prompts adapted from Morris and Usher (2011) were used to elicit teacher reflections on the sources of their self-efficacy:

1) What experiences in your professional life as a teacher have made you more confident in your teaching ability? Please explain why these experiences made you feel more capable as a teacher.

2) What experiences in your professional life have lowered your confidence in your teaching ability? Please explain why these experiences made you feel less capable as a teacher.

Teachers’ responses to open-ended survey items ranged in length from a few words to several paragraphs, with most responses including three to four sentences in response to each question.

Interviews

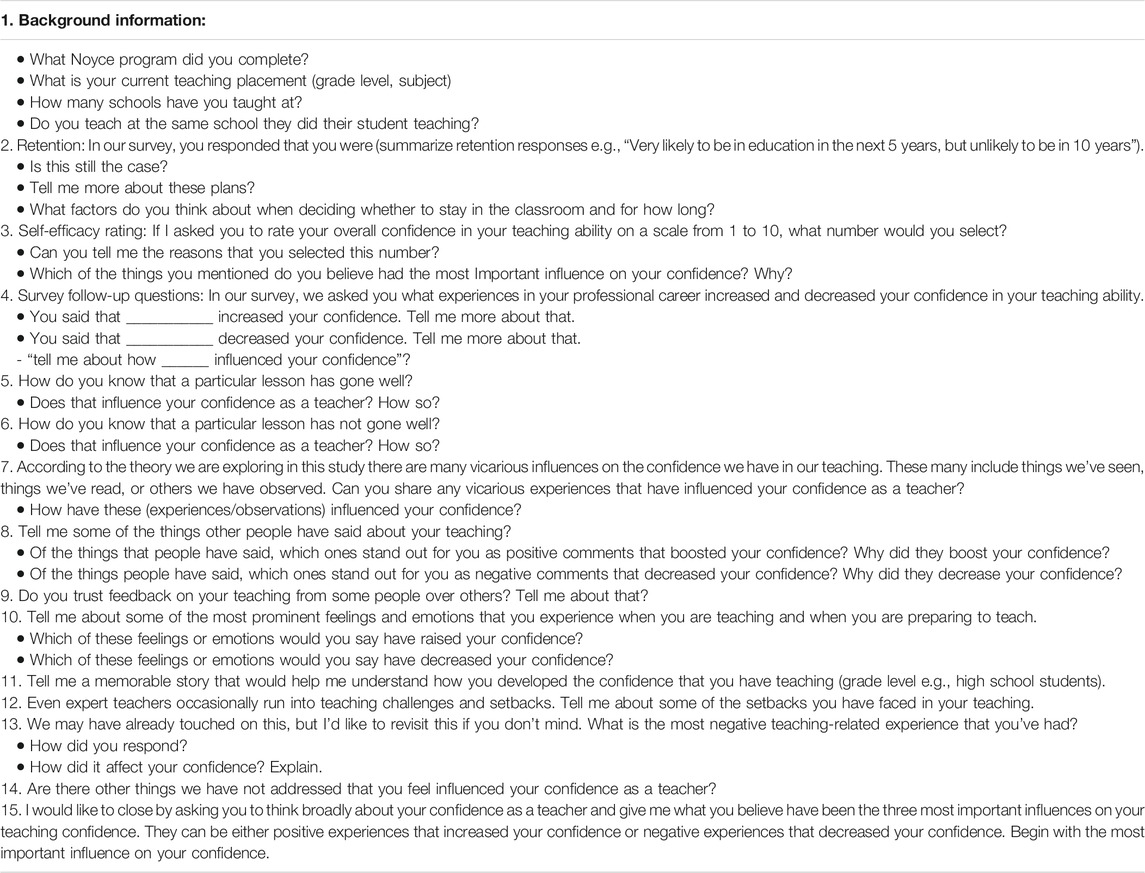

Ten semi-structured interviews lasting approximately 60 min were conducted by one of three members of the research team during the school year following survey administration. Interviews were conducted by telephone during a 1-month period. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis. Interviews utilized a protocol adapted from Morris and Usher (2011) designed to elicit teachers’ accounts of the sources of their self-efficacy (see Table 3). The protocol included both prompts designed to tap the hypothesized sources of self-efficacy as well as questions that allowed teachers to reflect more broadly on the sources of their self-efficacy.

Data Analysis

TSES data were analyzed using guidelines suggested by Tschannen-Moran and Hoy (2001), with average scores calculated across all items and for items within each sub-scale. One-way ANOVAs and independent samples t-tests were used to compare teachers’ scores on the TSES and TSES sub-scales by gender, subject area, and experience level (Beginning, Novice, Career).

Responses to open-ended items were subjected to sequential qualitative analysis (Miles et al., 2019). The initial codebook consisted of Bandura (1997) definitions of the sources along with specific guidance from the self-efficacy literature concerning the types of responses to be coded to each source. To identify instances related to increases or decreases in self-efficacy, the codebook included both positive and negative codes for each of the sources. Note that, because we coded for both positive and negative examples, we describe results using the term “enactive experiences” rather than “mastery experiences,” which are inherently positive. Additional codes were iteratively added and refined to code for other experiences teachers described as increasing or decreasing their confidence. Using the NVIVO software program, responses were coded by two coders who convened after coding a subset of the data to refine the codebook and establish reliability (>90%). Although the vast majority of responses could be coded to at least one source, twenty-three (6%) did not provide sufficient detail to code. Following coding, we created a database of dichotomous entries (0 = No; 1 = Yes) indicating whether each teacher identified each of the sources of self-efficacy. Chi-square tests of independence were calculated to explore the frequency with which teachers’ identified each of the sources by experience level, gender, subject, and whether teachers teach at a high-need school.

Interviews were coded and analyzed by one researcher using a codebook adapted from the one used to code open-ended survey items. In addition to applying theory-driven codes aligned to the sources, interview coding and analysis sought to identify salient patterns, themes, and stories illustrating how teachers’ experiences shaped their self-efficacy beliefs. Following coding, partially-ordered and case-ordered matrices (Miles et al., 2019) were constructed to describe patterns in the sources of self-efficacy identified by interview participants.

Results

This section first summarizes the self-efficacy and sources of self-efficacy identified by Noyce teachers then describes variations in self-efficacy by teacher experience level.

Self-Efficacy

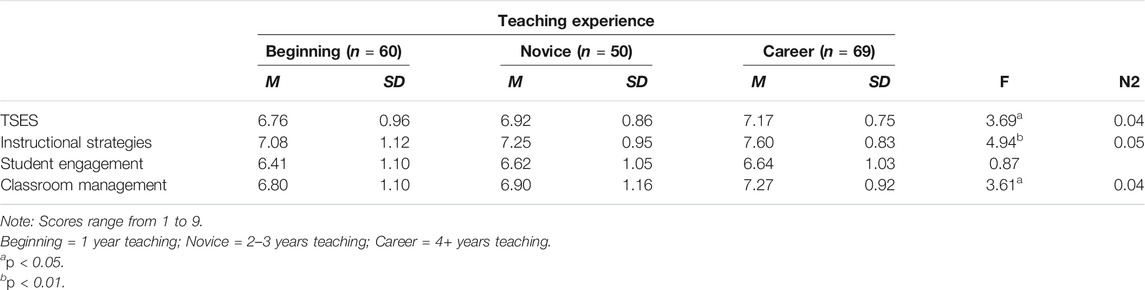

Overall scores on the TSES ranged from 4.2 to 9.0 with an average of 6.9. Table 4 presents TSES data by experience level (Beginning, Novice, and Career). One-way ANOVAs indicated significant but modest differences in average TSES scores, F (2,176) = 3.69, p < 0.05, instructional strategies, F (2,176) = 4.94, p < 0.01, and classroom management, F (2,176) = 3.61, p < 0.05 by teacher experience level. Tukey’s HSD tests showed that Beginning teachers had lower overall self-efficacy and self-efficacy for instruction and classroom management than Career teachers. Average TSES scores and TSES subscale scores did not differ significantly by subject area (Math, Science, Both Math/Science, or Other), level (elementary, middle, or high school), gender, or whether respondents teach in a high need school.

TABLE 4. Means, standard deviations, and one-way analyses of variance in teaching self-efficacy by teaching experience.

The Sources of Self-Efficacy

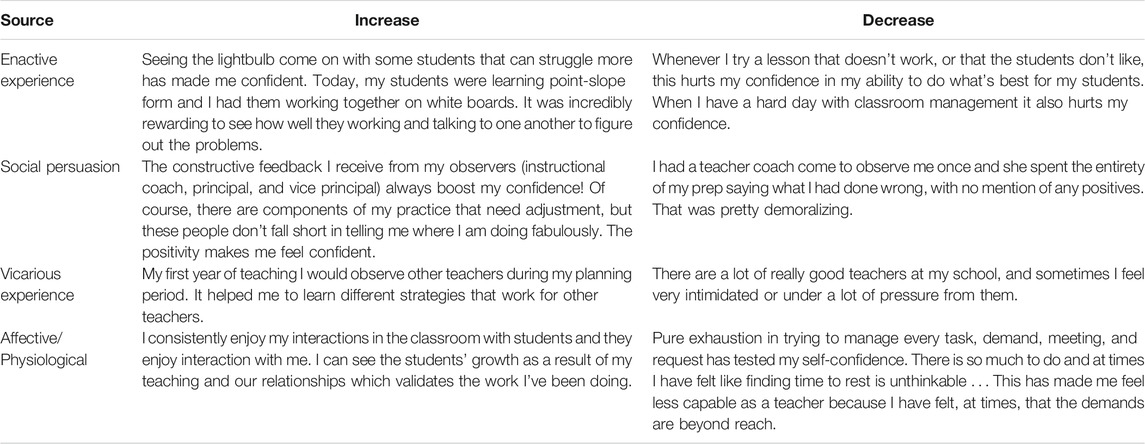

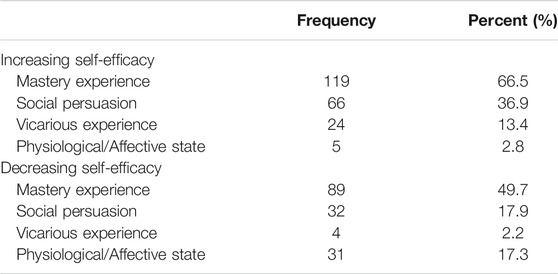

Consistent with Bandura (1997) assertion that enactive mastery experiences typically represent the most potent source of self-efficacy, these types of experiences were the most commonly cited, with 67% of teachers describing positive mastery experiences as a source of increased self-efficacy and 50% describing negative enactive experiences (e.g., failures, mistakes) as a source of decreased self-efficacy (see Table 5). Social persuasions were also reported frequently in open-ended survey responses, followed by vicarious experiences and affective and physiological states. Teachers were more likely to identify mastery experiences, social persuasions, and vicarious experiences when reflecting on increases in their self-efficacy than they were when describing experiences that decreased their self-efficacy. Notably, this was not the case for affective/physiological states, which only occurred in 5 (3%) teachers’ reflections on experiences increasing their self-efficacy but 31 (17%) teachers’ descriptions of experiences that decreased their self-efficacy. See Table 6 for illustrative quotations for each of the sources of self-efficacy.

TABLE 5. Frequency of sources identified in open-ended survey responses as increasing or decreasing teaching self-efficacy.

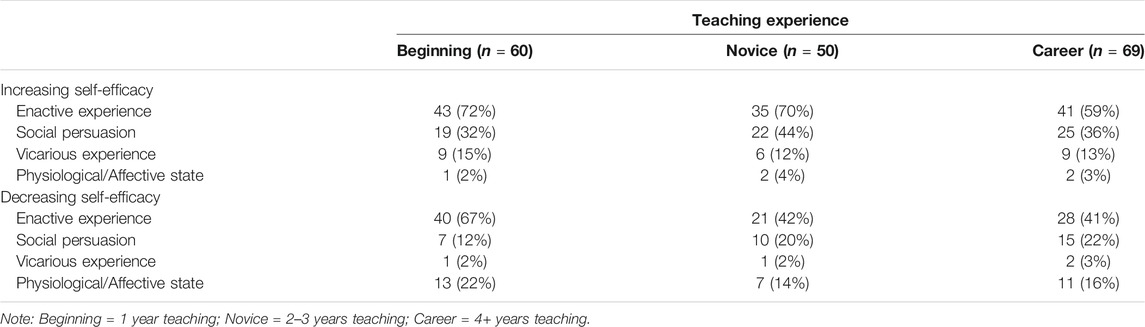

Chi-square tests of independence were calculated to determine whether the frequency with which teachers identified each of the sources in open-ended survey responses (coded with binary 0–1 values) varied by teacher experience level (Beginning, Novice, Career), gender, subject area, and whether teachers currently teach at a high need school. Beginning teachers were more likely to report negative enactive experiences (e.g., failures, mistakes; 67%) that lowered their self-efficacy than Novice (42%) or Career teachers (41%),

TABLE 7. Frequency and percentage of teachers identifying sources of self-efficacy by experience level.

Consistent with Bandura’s assertion that people integrate multiple sources of efficacy-relevant information in forming their self-efficacy beliefs, many teachers shared experiences reflective of multiple sources. Of the 179 teachers in the sample, 49 (27%) described multiple sources when discussing experiences that increased their confidence and 26 (16)% described multiple sources when discussing experiences that decreased their confidence. These instances included both examples in which teachers listed various sources as well as examples in which teachers described experiences that integrated more than one source. In light of the frequency with which teachers cited and integrated multiple sources, the following summary presents qualitative findings related to each source while also including examples illustrating combinations of the sources of self-efficacy.

Enactive Experiences

Teachers’ reflections on enactive experiences often focused on successes and failures related to student learning and performance. As in the following survey response from Chris, teachers commonly discussed how students’ earning good grades or performing well on assessments affirmed their beliefs in their teaching ability:

The success that my students had on the end of year State Regents exams made me confident in my teaching ability. You are always a little unsure in your first year whether you are missing something, or spending too much time on certain topics or not enough on others, so to get good results reaffirms your teaching methods.

Conversely, many teachers described how students’ poor performance lowered their teaching self-efficacy. In the following survey response, a teacher described how looking at her students’ poor grades made her “feel incapable of teaching”:

I feel incapable of teaching when I look at my students’ grades and see that many of them are struggling. I provide multiple chances for my students to make up work and they still choose to let their grades slip. Even though I know I have done everything I can to assist them in passing and understanding content, I still struggle with watching them fail.

In addition to measures such as grades and test scores, teachers shared more subjective observations related to student learning. One theme that emerged from both open-ended survey responses and interview data was the occurrence of “light-bulb moments” in which teachers observed a student suddenly come to understand a new concept. In the following survey response, a high school mathematics teacher drew a direct connection between her confidence in her teaching ability and one of these “light-bulb moments”:

I feel more confident in my teaching abilities when I see a student have that light bulb moment. For example, if a student did not understand a concept the previous year or the even the first time I taught it, I feel it is encouraging when they say “Oh, now I get it!”

Other teachers highlighted observations related to student engagement and classroom management as either increasing or decreasing their self-efficacy. For example, in her survey response, one middle school science teacher wrote:

When a lesson goes really well and all students are very engaged and are using appropriate language to talk to each other about the content, this makes me feel really good and like I am doing something right. I know that I provided them enough information and support for them to understand the topic and that I chose something interesting enough to get their attention.

Teachers tended to discuss classroom management as a challenge that decreased their self-efficacy more often than they described classroom management successes increasing their self-efficacy. Several anecdotes about classroom management challenges coupled mastery experiences and affective states, often with teachers describing how frustrated or exhausted they felt when they “lost control” of their classroom.

Consistent with findings in Morris and Usher (2011) study, there were many examples of teachers framing negative teaching experiences in adaptive ways that did not seem to lower their self-efficacy. Joe described how positive experiences were fortifying, stating that on days when his lessons go well “it kind of gives you a reason to keep working through the tougher days.” He went on to discuss how he draws on these positive experiences he has “in the bank” to cope with challenging days:

There are days where you’re like, ‘Wow. That really didn’t work at all. I really need to revisit that’, but you have in the bank those days that worked really well, so you’re more motivated, I guess, to try and improve and compare the things that went well in that lesson, to maybe some of the things that didn’t go so well, and try and change the lesson for the next time that you teach it.

The tendency to reflect on negative teaching experiences opportunities for problem-solving rather than deficits in teaching ability is apparent in Alicia’s inclination to take lackluster student performance as a “cue” to reflect on “mis-instruction”:

I would know that a lesson has not gone as well as I thought it had when on the exit ticket I see that my high flyers did not do as well. That’s my cue to look for patterns of mis-instruction, write them down, think about how to reteach it or how to further explain something.

Although this type of adaptive framing was most common among experienced teachers with relatively high self-efficacy, Katy and Nicole, both second year teachers with lower than average self-efficacy, also framed negative teaching episodes as learning experiences. Katy described her reaction to lessons that do not go well, saying, “I mean, I kind of like those, because then I learn from them, you know?” Similarly, Nicole explained how “being humble enough to admit when the lesson sucks actually increases my confidence probably more than having a lesson that is successful because it gives me more information about trying different things.”

In discussing how negative enactive experiences lowered their self-efficacy, teachers primarily identified patterns of persistent failure, such as consistent low student performance over time or high proportions of students performing poorly, rather than isolated episodes. For example, in her survey response, one high school mathematics teacher shared that “students in my class consistently score low on their summative assessments. This makes me lose confidence over whether or not I am effectively communicating the information in the chapters.” Another high school mathematics teacher who struggled with student engagement shared in her survey response that she doubted her teaching ability when “multiple students in a single class were failing and none of my tactics to get them to complete work was working.”

As evident in this teacher’s reference to none of her tactics working, teachers described instances when students failed in spite of their exerting great effort as particularly detrimental to their self-efficacy. Brian explained how his confidence in his teaching ability decreased when no matter what he tried, some students “just don’t get it”:

When the kids don’t get it and when I can tell that the wheels aren’t spinning. I’m going to be honest, I can try 50 different things and there are a few kids that no matter what I try, no matter how much I do, they just don’t get it.

Similarly, several teachers described how not being able to explain students’ poor performance lowered their self-efficacy. For instance, one high school science teacher noted in her survey response that “I have had many instances where students unexpectedly fail a test or assignment, and I cannot explain why. This always makes me feel like I have done something to fail them.”

A number of science teachers described how expectations to teach outside their area of expertise, teach multiple science disciplines, or switch between disciplines precipitated negative enactive experiences that lowered their self-efficacy. For example, Steve, who majored in chemistry, noted that “my first couple years of teaching I was changing subjects pretty quickly,” adding that it was “definitely a setback, after spending a year or two in developing a curriculum, and then just being thrown into a new subject where I hadn’t taught for a while and wasn’t as confident.” This shifting context for science teachers may explain why they were more likely than math teachers to identify negative mastery experiences.

Interview data suggest that our open-ended survey data may not necessarily capture how enactive experiences interacted with other sources of self-efficacy. When asked to elaborate on survey responses that focused on enactive experiences, several teachers added information indicative of other sources. Consider the following survey response provided by Stephanie:

I was able to give a professional development on anchor charts where I was recognized for bridging the gap for ELLs. This made me feel capable because I felt like my actions truly made an impact for my students.

Although Stephanie referenced receiving recognition, this response was coded as a mastery experience because it focuses on the achievement of “bridging the gap for ELLs” and draws an explicit connection between her successful enactive experience (providing professional development) and feeling capable in her teaching. However, when Stephanie elaborated on this response in her interview, social persuasions became a more prominent source:

During those observations, they were really impressed with what I was doing, and they asked me to share it with the whole team, because that was something that the whole staff was not doing….they told me that they were impressed by the anchor charts, by the visuals that I would supply during the lesson plan, during the lesson, the kinesthetic movements that I would do with the kids, and at some point, the principal came up to me and told me that she would like to do a professional development on different teaching styles, and that what she really wanted to do was help the staff learn how to bridge the gap for the ELL learners.…So they were really impressed by it. The staff really enjoyed it and a lot of them have been emailing me and asking me to help them with anchor charts for their classroom, graphic organizer, worksheets for their class, how to translate documents.

Stephanie acknowledged her success working with ELL students but foregrounded social persuasions, noting several times that observers were impressed and referencing validation of her efforts by her principal and others. Thus, in this example, Stephanie’s teaching self-efficacy is bolstered through both her successful deployment of strategies with ELL students (mastery experiences) and, perhaps even more so, through positive feedback from other teachers and administrators (social persuasions). In other interview studies, instructors have similarly described relying on social persuasions to evaluate their achievements (Phan and Locke, 2015; Morris and Usher, 2011).

Social Persuasions

The social persuasions teachers described most often took the form of positive or negative feedback from other teachers, administrators, students, or parents. As illustrated in the following survey response from a high school mathematics teacher, participants commonly described how receiving recognition for their teaching boosted their confidence:

Within my first months as a teacher, I was honored to be observed as an effective teacher during instructional rounds. I receive regular coaching observations that consistently show high marks for engagement and classroom culture. My Student Perception surveys report scores higher than my district and school averages. This strong positive feedback is validating, and it has helped me to feel confident that my efforts are noticed, appreciated, and effective.

Similar to Stephanie’s account above, this teacher’s response focuses on social persuasions (being identified as an effective teacher, student perception surveys, positive feedback) while also alluding to mastery experiences (success with student engagement and classroom culture). Indeed, social persuasions and mastery experiences tended to be a powerful combination, occurring in many of the most fervent accounts of positive experiences increasing teachers’ self-efficacy. For example, Andrea described an observation debrief with her principal as a particularly positive social persuasion, stating, “hearing from another adult that they learned something and they enjoyed my lesson made me feel like I could conquer the world.”

Teachers also shared examples of negative feedback or comments lowering their teaching self-efficacy. These instances often occurred in conjunction with observations conducted as part of teacher evaluations. In some cases, teachers described how receiving negative feedback precipitated a strong emotional response. For example, in her survey response, one high school science teacher explained how a walkthrough during her first year of teaching occurred “during a really bad moment in the classroom” and resulted in her feeling “like I was seen and judged at my worst,” adding that “I felt powerless to avoid being put into that situation again.”

Although teachers cited feedback from other teachers and administrators most often, they often mentioned feedback from multiple people and frequently highlighted feedback from students as particularly influential. In the following survey response, a middle school math teacher described how eliciting feedback from students increased his self-efficacy:

Having open and candid discussions with my students about their preferences has helped me gain confidence in my teaching. During those discussions, my students and I reflect on my efforts in teaching and their efforts in learning to find a happy medium where students are able to learn effectively.

In addition to informal student feedback, a number of teachers noted that their self-efficacy is influenced by formal feedback conveyed through student surveys. For example, Katy describes how she was “fairly confident” in her self-efficacy for classroom management based on the results of her school’s quarterly Learner Perceptions Survey. The dataset also includes numerous examples of teachers receiving positive feedback conveyed by former students, with students attributing their successes or the application of knowledge or skills to their experience in a teachers’ class.

Open-ended survey prompts were not designed to elicit reflections on the trustworthiness of social persuasions; however, all ten interview participants described factors that influenced how much they trusted feedback received from various sources. The most common factor teachers cited was the expertise of the person providing feedback, often sharing perceptions of administrators’ or colleagues’ experience in their subject area. For example, Steve explained how his respect for his colleagues and administrators’ influenced how much he trusts feedback stating, “there are teachers, at my school, who I respect as fellow educators. So, hearing them complement something that I’ve done means a lot more than teachers who I have less respect for.” He added that the same is true of administrators, noting that he tends to trust feedback from administrators who have a science background more readily than those who do not. In his reflection on student feedback, Steve shared how he weighs feedback provided by students according to their effort, another tendency that was recurring in the dataset:

There’s students whose feedback matters to me more than others. There is a student who’s doing well and trying really hard in class, probably more trying hard in the class than anything else. Hearing feedback from them telling me I did a good job means a lot more than a student who doesn’t really do much or a student who is sort of naturally skilled.

Vicarious Experiences

Relative to enactive experiences and social persuasions, vicarious experiences were mentioned less often. Teachers who did reference vicarious experiences most often shared observations of colleagues or mentors or strategies modeled in the context of professional development (e.g., conferences, PLCs). In the following reflection, Alicia described how her experience observing in a “random classroom” and co-teaching mathematics vicariously influenced her teaching:

I feel like I’ve been exposed to a lot of teaching styles. With the three years that I’ve been teaching, I’ve taken a lot of time out of one of my free periods to just sit in random classrooms and observe different teaching styles. Within my classroom, there are two teachers that teach two different maths, regular 8th grade math and then algebra, which is me. So when I’m not teaching, the other teacher is teaching, and through her, I’ve learned to be more detailed in my explanations … I’ve learned a lot just through watching a lot of teachers teach.

In another interesting example from the survey data, one middle school math teacher recounted filming and watching her own teaching, an activity Bandura (1997) identified as self-modeling:

Filming my teaching and watching my growth throughout my first year as a teacher, this made me feel more confident because it shows evidence of my improvement. Sometimes it’s hard to feel that I am improving since there is so much to learn as a first year teacher. However, when it is on film, the evidence cannot be denied and this makes me feel proud of my accomplishments although I know I still have room for improvement.

The influence of video self-modeling on self-efficacy has been explored in studies of parents, athletes, and students (e.g., Schunk and Hanson, 1989; Marcus and Wilder, 2009; Middlemas and Harwood, 2020). However, this vicarious experience has remains largely unexamined in the context of teaching, where studies have instead focused on the vicarious influence of watching others teach (e.g., Posnanski, 2002; Palmer, 2011). Bandura (1997) noted that self-modeling can provide unique information about one’s enactive attainments. As indicated by this participant, watching oneself may be particularly powerful in the early years of teaching when improvements are more obvious.

Vicarious experiences also informed referential comparisons in which teachers compared their performance to that of others. In survey responses, one teacher described feeling less confident when “students have compared my teaching to another teacher who they preferred” and another shared that “there are a lot of really good teachers at my school, and sometimes I feel very intimidated or under a lot of pressure from them.” Teachers also noted that referential comparisons could either increase their confidence or make them question their instruction. Joe explained:

I think you sort of naturally draw comparisons, and when you’re watching them teach, you are also able to watch the students a little bit more in-depth, because you don’t have to worry as much about what you’re presenting, and you can see when something really resonates with the students. So if that’s something that you also do, it reaffirms your beliefs in how you do things. Whereas, on the other hand, if it’s something that falls flat and doesn’t really resonate with the kids, you’re like, “Okay. I know that I need to avoid that in the future.”

Although vicarious experiences were identified less frequently than enactive experiences and social persuasions, there were teachers who described referential comparisons as the most important factor influencing their self-efficacy. For example, Craig admitted that comparing himself to less effective teachers is the “the thing that increases my confidence the most”:

Like I said, I think the thing that increases my confidence the most is comparing myself to other teachers, which I don’t think is necessarily a good thing. But it’s reassuring when I feel down on myself and I’m like, “I’m not a great teacher,” and then I look at the teachers around me and I’m like, “Okay, well relatively speaking, I guess I’m a really good teacher.”

By comparing his own performance (enactive experiences) with those of others he observed (vicarious experiences), Craig obtained what he felt was a more accurate assessment of his capabilities.

Affective or Physiological States

Although affective or physiological states were rarely mentioned as increasing self-efficacy, 17% of teachers referenced affective or physiological states when discussing experiences that decreased self-efficacy. Examples of physiological/affective states cited by teachers included feelings of exhaustion/fatigue, stress, feeling “burned-out,” and negative mental states (e.g., depression, anxiety). Most often, teachers described negative affective or physiological states in connection with attempts to cope with difficult students, colleagues, or administrators. For example, in his survey response, one high school science teacher cites stress arising from administrator expectations as the primary experience lowering her confidence: “At times there is much negativity and uncertainty of support or clear expectations from admin. This has resulted in times of stress, which has led to feeling insecure in my ability to perform to the best of my ability.”

A number of teachers recounted how their early teaching experiences were “exhausting” or “overwhelming,” often connecting these negative states to the feeling that they were failing their students. For example, one high school science teacher discussed his feeling of being overwhelmed by the demands of teaching in a high needs school:

Trying to help everyone can be overwhelming. My time in a high-needs school was exhausting as my natural habit is to help everyone. I still do this. But the problems with my students are so complex or rooted in years of abuse, mobility, etc. When students get expelled or drop out it feels like failure.

This teacher provides another example of how different sources, in this case enactive experiences and physiological and affective states, are often intertwined in efficacy judgments.

Female teachers referenced affective and physiological states more frequently and described more acute examples than male teachers in both surveys and interviews. Four female teachers and one male teacher told stories recounting incidents evoking a strong emotional response. For example, after describing how the lack of support from her previous administration “ruined how I thought of myself as a teacher,” Andrea stated:

It took an emotional toll but also kind of spiritual toll because if you feel like every day when you get to work that you’re not important and that you’re not a beneficial teacher, it makes you not want to do it anymore.

Andrea’s response reflects how physiological states may be both a source and an effect of teachers’ self-beliefs (Bandura, 1997; Kim and Burić, 2020).

Teaching Experience

Beginning teachers were more likely to report negative enactive experiences (e.g., failures, mistakes) as decreasing their self-efficacy than novice or career teachers. Many of these negative enactive experiences pertained to early experiences with classroom management. Although teachers at various experience levels reflected on classroom management, teachers in their first 3 years of teaching tended to describe more serious challenges; experienced teachers discussed challenges managing the behavior of individuals or small groups of students or occasional lapses in classroom management rather than more global challenges. In a survey response, one high school science teacher shared this reflection on struggles with classroom management during her first year:

My first year of teaching made me feel helpless about the behaviors of my students and my ability to have a respectful classroom or a place where students can come to peacefully learn. The students were not motivated and they fed off of each other to make a difficult environment for everyone else and I didn’t always know how to handle it or how to correct it.

In contrast, in a survey response, one experienced teacher shared that:

While I am able to build relationships, I still feel like at times I struggle with classroom management and that lowers my confidence in my teaching ability. It tends to be a handful of students that will push the limits.

When career teachers described experiences that lowered their confidence, many referred to challenges in their first years in the classroom rather than recent experiences. For example, one high school science teacher described the consequences of early struggles with classroom management:

My first year teaching I struggled immensely with classroom management. Especially with the two physical science classes that I taught. I had a rough year and was fired as a result. I seriously doubted if I could teach and manage a classroom the way that I had envisioned.

Similar to this retrospective reflection on enactive experiences, regardless of experience level, teachers tended to focus on vicarious experiences occurring early in their careers. This is not surprising given that vicarious experiences are considered especially powerful when a task is still novel (Bandura, 1997). Many beginning teachers referred to preservice teaching experiences, such as one survey respondent who stated simply “student teaching gave me an example and model of effective teaching.” A number of more experienced teachers described early vicarious experiences that involved observing mentors. For example, in his survey response, one high school science teacher shared, “early on, team teaching with more experienced teachers allowed me to observe effective teachers in action and implement strategies that they use.”

Although survey responses describing affective and physiological states were brief and generally did not vary according to teacher experience level, in interviews, teachers described an evolution in their approach to managing affective and physiological states. For example, Rachel provided the following account of how she responded to a “bad day” as a beginning teacher versus her current approach to coping with challenges:

I used to cry on the whole ride home. So, if I had a bad day, I taught an hour away from where I lived. I would cry for the whole hour home. Now, I feel like it’s more of a I can look at it more critically. This went bad. This is why. I need to change X, Y, and Z for next year. So, as opposed to being just kind of depressed and bummed, I feel like I have the tools to make a change so it’s not depressing anymore. It’s kind of more like I take it as feedback as opposed to someone screamed at me saying my lesson sucked. It’s more of something to build from as opposed to just depressing.

Notably, as in Rachel’s account of crying for the entirety of her commute, teachers typically described strong emotional responses or more acute examples of physiological states rather than mild or moderate levels of arousal, which are thought to promote improved performance (Teigen, 1994).

Discussion

The primary purpose of this study is to investigate the sources of self-efficacy identified by Noyce teachers and interconnections between self-efficacy, the sources of self-efficacy, and teacher experience. Analysis of self-efficacy data coupled with qualitative survey and interview data lends insight into the experiences teachers find most meaningful when reflecting on and evaluating their teaching ability.

Teachers with more experience reported higher self-efficacy for instructional strategies and classroom management, but not for student engagement. This finding is consistent with other studies comparing practicing teachers with different amounts of experience (Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy, 2007; Wolters and Daugherty, 2007). Once removed from teacher education programs, new teachers must contend with managing a classroom and deploying multiple instructional strategies on their own for the first time. As described by interviewees, teaching during a practicum is a somewhat limited and protected experience that reflects only a fraction of the demands of full-time teaching. This may be why, as Woolfolk Hoy and Burke-Spero (2005) found, teachers’ self-efficacy decreases between the end of teacher education and the first year of teaching. As teachers accumulate more experience managing classrooms of their own, they may feel more capable as instructors. Alternatively, these trends – both in this study and in the wider literature – may reflect attrition of those who do not believe they can teach well. That self-efficacy for student engagement did not change at different levels of experience may indicate that, even with limited previous experiences, teachers entered their career with a relatively stable sense of their ability to motivate students. Thus, these findings lend support to previous research underscoring the importance of providing continuing support for early career teachers as they make the transition from pre-service to full-time teaching positions, particularly when it comes to developing proficiency with classroom management and instructional delivery.

Teachers with less experience were also more likely to identify negative enactive experiences (i.e., instructional failures, mistakes) when reflecting on the sources that decreased their self-efficacy. This seemingly conflicts with findings by Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy (2007), who suggested that other sources are more salient for novice teachers because they have had fewer mastery experiences. However, this finding may instead point to the problems inherent in measuring enactive experiences only as positive affective appraisals (i.e., “satisfaction with your professional performance this year”; Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy, 2007). Bandura (1997) did indeed note that other sources can be more powerful when a task is novel and individuals have had few opportunities to perform that task. However, the task is no longer novel for teachers who have already had some experience teaching a classroom of their own. Their experiences differ from those of preservice teachers who are just beginning to teach. No longer do they observe teaching models on a regular basis (vicarious experiences) nor receive the abundance of feedback (social persuasions) typical of a teaching practicum. Instead, as documented in our interviews, teaching in a class of one’s own provided the most powerful information that one was, or was not, capable. Scholars have suggested that teachers may begin to feel less capable when struck by the complexity of teaching in an authentic setting (Rushton, 2000; Woolfolk Hoy and Burke-Spero, 2005). Our quantitative and qualitative findings provide evidence that feelings of failure during these early instructional experiences can have a particularly profound influence on teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs. Critically, when considering the implications of teachers’ early enactive experiences, it is important to remember that self-efficacy reflects teachers’ perceptions of their ability rather than actual performance. For teachers in our study who shared negative enactive experiences, lower self-efficacy wasn’t necessarily an inevitable result of failures or mistakes made in their early teaching experiences but rather a reflection of how they interpreted efficacy-relevant information related to failures or mistakes. Indeed, consistent with previous research (Morris and Usher, 2011) some teachers framed failures more adaptively as learning experiences that did not threaten their overall teaching self-efficacy. The rather profound, lasting influence that negative enactive experiences had for some teachers suggests that continuing support aimed at guiding early career teachers to reflect on and perhaps even reframe negative teaching experiences may be a promising approach to protecting teachers’ sense of efficacy at the early stages of their careers.

Vicarious experiences were identified less frequently than enactive mastery experiences and social persuasions for teachers at all experience levels. According to Bandura (1997), vicarious experiences tend to be most influential when a task is still novel, which may explain why vicarious experiences were relatively rare within our dataset and often described as occurring during preservice teaching experiences. In other studies, preservice teachers have similarly described teaching models as powerful sources of self-efficacy during teacher education, in that they model effectiveness and the skills to become effective (e.g., Gunning and Mensah, 2011; Siwatu, 2011). However, little is known about the influence of vicarious experiences for practicing teachers who no longer benefit from an assigned in-class mentor. Prior to this study, no published research existed in which the vicarious experiences of practicing teachers were quantified. In interviews following professional learning experiences, practicing teachers have described feeling more capable after seeing a colleague teach well, particularly when they gained pedagogical knowledge from the experience (Bruce et al., 2010; Palmer, 2011; Chong and Kong, 2012). However, consistent with Bandura (1997) descriptions, these experiences could also lead to referential comparisons in which teachers’ self-efficacy improved with favorable comparisons but diminish when they viewed others as more capable (Bruce and Ross, 2008; Locke et al., 2013). For some teachers in our study, such comparisons had a profound impact on their pedagogical knowledge and sense of efficacy. Taken together, our findings suggest that for practicing teachers, observations of colleagues are most influential when used to judge one’s relative mastery of instructional skills and knowledge.

That physiological and affective states were described least frequently is consistent with previous studies in which teachers were interviewed (Palmer, 2011; Morris and Usher, 2011; Mulholland and Wallace, 2001). Morris et al. (2017) suggested that this may be due to the difficulty of recalling something that is ongoing rather than a more salient event. In both surveys and interviews, female teachers in the study were more likely than male teachers to describe physiological and affective states that influenced their sense of efficacy. In previous research, preservice and practicing female teachers have similarly reported provided higher ratings of stress (Klassen and Chiu, 2010; Klassen and Durksen, 2014). The differential influence of stress on practicing teachers’ self-efficacy has been unclear, however. Klassen and Chiu (2010) found that female teachers reported higher stress related to student behaviors, which in turn predicted lower teaching self-efficacy across all measured dimensions. Their higher workload stress, however, was paradoxically associated with higher self-efficacy for classroom management. Findings from the present study provide more evidence of the gendered influence of stress on self-efficacy and suggest that relationships with school administration can be an additional source of stress for female teachers. Moreover, the qualitative approach allowed a richer understanding of how enactive experiences can be inextricably tied to teachers’ physiological and affective states. Future research can investigate the causes of differences in reported stress levels by gender. It is likely that the differential pressures, expectations, and even discrimination or harassment faced by female teachers have implications for their physiological and affective states. It is also plausible that, due to traditional notions of masculinity, differences in reporting reflect that men are more reluctant to express or even acknowledge vulnerable feelings (Levant et al., 2003).

Teachers reflections and stories also highlight the complexity of self-efficacy beliefs and the constellation of sources teachers draw upon when making determinations about their teaching ability. We found clear evidence of each of the sources of self-efficacy postulated by Bandura (1997) and the frequency with which teachers identified the various sources conformed to what we might expect based on social cognitive theory and previous research. For instance, given that mastery experiences are thought to be the most potent source of self-efficacy, we would have been surprised if they were not the most commonly cited source by teachers in our study. At the same time, the ways in which teachers referenced and often integrated multiple sources, especially when asked to elaborate in interviews, remind us that there is no simple formula by which teachers’ experiences are translated into self-efficacy beliefs and that self-efficacy beliefs are not cultivated in a vacuum. Indeed, many survey responses and narratives foregrounded contextual factors and the particularities of their teaching circumstances when describing experiences related to the sources of self-efficacy. Future research should further explore the ways in which contextual factors and the level and sources of support teachers receive influence their appraisals of self-efficacy. For instance, our finding that science teachers more frequently report negative mastery experiences than math teachers appeared to be due, at least in part, to the frequency with which science teachers are asked to teach new subjects that may or may not align with their previous education and pedagogical training. This finding points to a particular need to carefully consider the ways in which frequent changes in teaching placements may influence science teachers’ self-efficacy and whether there may be ways to better prepare science teachers for the likelihood of teaching multiple subjects in their first years of teaching.

Although we hope this study will be instructive for a broad audience of teacher educators and researchers, it is not without limitations. We sought to include a diverse sample representing numerous Noyce programs across the country; however, certain characteristics of Noyce programs and the teachers who participate in them, such as their focus on recruiting and supporting STEM majors, along with our relatively small sample mean that the results of this study should be considered within the context of the Noyce program. Additionally, the study’s reliance on cross-sectional data limits the degree to which we can draw conclusions about the differential influence of the sources of self-efficacy over the early years of teachers’ careers. Longitudinal qualitative research that traces how the sources of self-efficacy manifest over the course of teachers’ careers would advance our understanding of the relationship between teaching experience and the sources of self-efficacy. Finally, although open-ended survey items may provide more useful data on the sources of self-efficacy than some of the more simplistic measures used in previous research (e.g., retrospective ratings of mastery, time spent teaching), teachers’ responses did not always draw clear connections between the sources identified and their appraisals of their teaching ability. The second phase of our study in which we conducted in-depth interviews was intended to address limitations in the open-ended survey methodology. Indeed, we found that qualitative interviews generated much richer accounts of the sources of self-efficacy identified by Noyce teachers.

Conclusion

This study offers potential implications for theory, practice, and research relevant to self-efficacy and the preparation of early career teachers. Previous research on the sources of practicing teachers’ self-efficacy has largely been devoted to examining changes following professional development (e.g., Bruce et al., 2010; Chong and Kong, 2012). Few scholars have examined how the influence of the sources naturally evolves during a teaching career. This study is unique in that it is the first mixed-methods study to explore this evolution across all four sources identified by Bandura (1997). Thus, this study adds to the field’s current understanding of the sources of teaching self-efficacy and the ways in which the sources may combine or interact to influence teachers’ self-efficacy after they enter the field. Given the relative importance of early enactive experiences and social persuasions, those who educate and supervise teachers can work to develop environments that support, rather than discourage, novice teachers when they fail. Research that further explores the influence of particular experiences on teachers’ self-efficacy at different stages of their career can inform what administrators can do to foster self-efficacy and how induction programs can best support new teachers.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because Data sharing is limited by IRB approved participant consent forms. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to amVzc2ljYS5nYWxlQGNlaXNtYy5nYXRlY2guZWR1.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Georgia Institute of Technology Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

JG, MA, and CC designed the study. JG led the collection and analysis of data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MA and CC developed the online survey, assisted with interview data collection and analysis. DM wrote sections of the manuscript and advised on data collection and analysis. MA, CC, and DM reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have made a substantial contribution to the work and have agreed to the published final manuscript.

Funding

This project is funded by the National Science Foundation, grant #1660597. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in these materials are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge CEISMC Research Coordinator, Ms. Emily Frobos for her assistance with this research.

References

Aloe, A. M., Amo, L. C., and Shanahan, M. E. (2014). Classroom Management Self-Efficacy and Burnout: A Multivariate Meta-Analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 26, 101–126. doi:10.1007/s10648-013-9244-0

Brown, C. G. (2012). A Systematic Review of the Relationship between Self-Efficacy and Burnout in Teachers. Educ. Child Psychol. 29, 47–63.

Bruce, C. D., Esmonde, I., Ross, J., Dookie, L., and Beatty, R. (2010). The Effects of Sustained Classroom-Embedded Teacher Professional Learning on Teacher Efficacy and Related Student Achievement. Teach. Teach. Edu. 26, 1598–1608. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2010.06.011

Bruce, C., and Ross, J. (2008). A Model for Increasing Reform Implementation and Teacher Efficacy: Teacher Peer Coaching in Grade 3 and 6 Mathematics. Can. J. Edu. 31 (2), 346–370. doi:10.2307/20466705

Chesnut, S. R., and Burley, H. (2015). Self-efficacy as a Predictor of Commitment to the Teaching Profession: A Meta-Analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 15, 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2015.02.001

Chong, W. H., and Kong, C. A. (2012). Teacher Collaborative Learning and Teacher Self-Efficacy: The Case of Lesson Study. J. Exp. Edu. 80, 263–283. doi:10.1080/00220973.2011.596854

Creswell, J. W., and Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

George, S. V., Richardson, P. W., and Watt, H. M. (2018). Early Career Teachers' Self-Efficacy: A Longitudinal Study from Australia. Aust. J. Edu. 62 (2), 217–233. doi:10.1177/0004944118779601

Geving, A. M. (2007). Identifying the Types of Student and Teacher Behaviours Associated with Teacher Stress. Teach. Teach. Edu. 23, 624–640. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2007.02.006

Gunning, A. M., and Mensah, F. M. (2011). Preservice Elementary Teachers' Development of Self-Efficacy and Confidence to Teach Science: A Case Study. J. Sci. Teach. Edu. 22, 171–185. doi:10.1007/s10972-010-9198-8

Hong, J. Y. (2012). Why Do Some Beginning Teachers Leave the School, and Others Stay? Understanding Teacher Resilience through Psychological Lenses. Teach. Teach. 18 (4), 417–440. doi:10.1080/13540602.2012.696044

Hoy, A. W., and Spero, R. B. (2005). Changes in Teacher Efficacy during the Early Years of Teaching: a Comparison of Four Measures. Teach. Teach. Edu. 21, 343–356. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.01.007

Kim, L. E., and Burić, I. (2020). Teacher Self-Efficacy and Burnout: Determining the Directions of Prediction through an Autoregressive Cross-Lagged Panel Model. J. Educ. Psychol. 112 (8), 1661–1676. doi:10.1037/edu0000424

Klassen, R. M., and Chiu, M. M. (2010). Effects on Teachers' Self-Efficacy and Job Satisfaction: Teacher Gender, Years of Experience, and Job Stress. J. Educ. Psychol. 102, 741–756. doi:10.1037/a0019237

Klassen, R. M., and Chiu, M. M. (2011). The Occupational Commitment and Intention to Quit of Practicing and Pre-service Teachers: Influence of Self-Efficacy, Job Stress, and Teaching Context. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 36, 114–129. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.01.002

Klassen, R. M., and Durksen, T. L. (2014). Weekly Self-Efficacy and Work Stress during the Teaching Practicum: A Mixed Methods Study. Learn. Instruction 33, 158–169. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.05.003

Klassen, R. M., Tze, V. M. C., Betts, S. M., and Gordon, K. A. (2011). Teacher Efficacy Research 1998-2009: Signs of Progress or Unfulfilled Promise?. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 23, 21–43. doi:10.1007/s10648-010-9141-8

Klassen, R. M., and Tze, V. M. C. (2014). Teachers' Self-Efficacy, Personality, and Teaching Effectiveness: A Meta-Analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 12, 59–76. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2014.06.001

Levant, R. F., Richmond, K., Majors, R. G., Inclan, J. E., Rossello, J. M., Heesacker, M., et al. (2003). A Multicultural Investigation of Masculinity Ideology and Alexithymia. Psychol. Men Masculinity 4, 91–99. doi:10.1037/1524-9220.4.2.91

Locke, T., Whitehead, D., and Dix, S. (2013). The Impact of “Writing Project” Professional Development on Teachers’ Self-Efficacy as Writers and Teachers of Writing. English Aust. 48 (2), 55–69.

Marcus, A., and Wilder, D. A. (2009). A Comparison of Peer Video Modeling and Self Video Modeling to Teach Textual Responses in Children with Autism. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 42 (2), 335–341. doi:10.1901/jaba.2009.42-335

Middlemas, S., and Harwood, C. (2020). A Pre-match Video Self-Modeling Intervention in Elite Youth Football. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 32 (5), 450–475. doi:10.1080/10413200.2019.1590481

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., and Saldana, J. (2019). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd Ed.. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Morris, D. B., and Usher, E. L. (2011). Developing Teaching Self-Efficacy in Research Institutions: A Study of Award-Winning Professors. Contemporary Educational Psychology 36(3), 232–245. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.10.005

Morris, D. B., Usher, E. L., and Chen, J. A. (2017). Reconceptualizing the Sources of Teaching Self-Efficacy: A Critical Review of Emerging Literature. Educational Psychology Review 29, 795–833. doi:10.1007/s10648-016-9378-y

Mulholland, J., and Wallace, J. (2001). Teacher Induction and Elementary Science Teaching: Enhancing Self-Efficacy. Teach. Teach. Edu. 17, 243–261. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(00)00054-8

Palmer, D. (2011). Sources of Efficacy Information in an Inservice Program for Elementary Teachers. Sci. Ed. 95, 577–600. doi:10.1002/sce.20434

Pfitzner-Eden, F. (2016). Why Do I Feel More Confident? Bandura's Sources Predict Preservice Teachers’' Latent Changes in Teacher Self-Efficacy. Front. Psychol. 7, 1–16. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01486

Phan, N. T. T., and Locke, T. (2015). Sources of Self-Efficacy of Vietnamese EFL Teachers: A Qualitative Study. Teach. Teach. Edu. 52, 73–82. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2015.09.006

Posnanski, T. J. (2002). Professional Development Programs for Elementary Science Teachers: An Analysis of Teacher Self-Efficacy Beliefs and a Professional Development Model. J. Sci. Teach. Edu. 13, 189–220. doi:10.1023/A:1016517100186

Rots, I., Aelterman, A., Vlerick, P., and Vermeulen, K. (2007). Teacher Education, Graduates’ Teaching Commitment and Entrance into the Teaching Profession. Teach. Teach. Edu. 23 (5), 543–556. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2007.01.012

Rushton, S. P. (2000). Student Teacher Efficacy in Inner-City Schools. Urban Rev. 32, 365–383. doi:10.1023/A:1026459809392

Schunk, D. H., and Hanson, A. R. (1989). Self-modeling and Children's Cognitive Skill Learning. J. Educ. Psychol. 81, 155–163. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.81.2.155

Siwatu, K. O. (2011). Preservice Teachers' Culturally Responsive Teaching Self-Efficacy-Forming Experiences: A Mixed Methods Study. J. Educ. Res. 104, 360–369. doi:10.1080/00220671.2010.487081

Teigen, K. H. (1994). Yerkes-Dodson: A Law for All Seasons. Theor. Psychol. 4 (4), 525–547. doi:10.1177/0959354394044004

Tschannen-Moran, M., and Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher Efficacy: Capturing an Elusive Construct. Teach. Teach. Edu. 17 (7), 783–805. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

Tschannen-Moran, M., and Hoy, A. W. (2007). The Differential Antecedents of Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Novice and Experienced Teachers. Teach. Teach. Edu. 23, 944–956. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2006.05.003

Tschannen-Moran, M., and Johnson, D. (2011). Exploring Literacy Teachers' Self-Efficacy Beliefs: Potential Sources at Play. Teach. Teach. Edu. 27, 751–761. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2010.12.005

Tschannen‐Moran, M., and McMaster, P. (2009). Sources of Self‐Efficacy: Four Professional Development Formats and Their Relationship to Self‐Efficacy and Implementation of a New Teaching Strategy. Elem. Sch. J. 110, 228–245. doi:10.1086/605771

Wolters, C. A., and Daugherty, S. G. (2007). Goal Structures and Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy: Their Relation and Association to Teaching Experience and Academic Level. J. Educ. Psychol. 99 (1), 181–193. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.181

Yada, A., Tolvanen, A., Malinen, O.-P., Imai-Matsumura, K., Shimada, H., Koike, R., et al. (2019). Teachers' Self-Efficacy and the Sources of Efficacy: A Cross-Cultural Investigation in Japan and Finland. Teach. Teach. Edu. 81, 13–24. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2019.01.014

Keywords: teacher self-efficacy, self-efficacy, teacher beliefs, STEM teacher education, sources of self-efficacy

Citation: Gale J, Alemdar M, Cappelli C and Morris D (2021) A Mixed Methods Study of Self-Efficacy, the Sources of Self-Efficacy, and Teaching Experience. Front. Educ. 6:750599. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.750599

Received: 30 July 2021; Accepted: 15 September 2021;

Published: 30 September 2021.

Edited by:

Evely Boruchovitch, State University of Campinas, BrazilReviewed by:

Christine Pleines, The Open University, United KingdomKathryn Holmes, Western Sydney University, Australia

Copyright © 2021 Gale, Alemdar, Cappelli and Morris. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jessica Gale, amVzc2ljYS5nYWxlQGNlaXNtYy5nYXRlY2guZWR1

Jessica Gale

Jessica Gale Meltem Alemdar

Meltem Alemdar Christopher Cappelli1

Christopher Cappelli1 David Morris

David Morris