94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 28 January 2022

Sec. Language, Culture and Diversity

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.735158

We present a case study where the use of both Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) and Inquiry-Based Science Education (IBSE) can be observed and studied as a hybrid methodology applied in a non-formal context in primary education. The context is the teaching of science in a Foreign Language (English) and the aim is to determine didactic strategies that are useful for improving teaching/learning processes. It is conducted in the non-formal context of science workshops, known as Saturdays of Science. 102 children in primary education attended the workshops, at which both the CLIL and the IBSE approaches were combined and which were supervised by 17 future teachers of primary education. The workshops were observed and analysed together with the changes introduced in the methodology and in the successive improvements to the teaching experience, examining the way in which they influenced the perceptions of the children and the future teachers. These results offer useful strategies for teachers in charge of CLIL teaching in primary education.

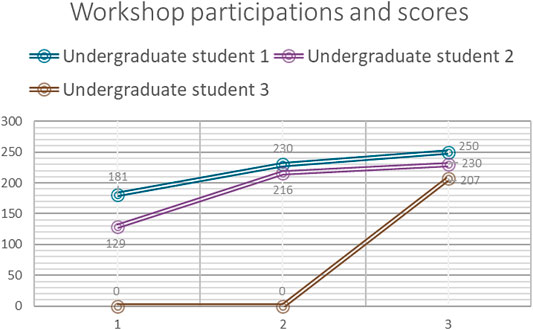

Graphical Abstract. Trend of the scores for three pre-service teachers as a function of participation in the workshops.

We present a case study where the use of both Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) and Inquiry-Based Science Education (IBSE) can be observed and studied as a hybrid methodology applied in a non-formal context in primary education. The context is the teaching of science in a Foreign Language (English) and the aim is to determine didactic strategies that are useful for improving teaching/learning processes. It is conducted in the non-formal context of science workshops, known as Saturdays of Science. 102 children in primary education attended the workshops, at which both the CLIL and the IBSE approaches were combined and which were supervised by 17 future teachers of primary education. The workshops were observed and analysed together with the changes introduced in the methodology and in the successive improvements to the teaching experience, examining the way in which they influenced the perceptions of the children and the future teachers. These results offer useful strategies for teachers in charge of CLIL teaching in primary education.

Inquiry-Based Science Education (IBSE) is a didactic strategy designed to incentivize the development of competencies (in terms of contents, skills, and attitudes), and to avoid the mere accumulation and memorization of scientific content. The strategy begins with the premise that pupils cannot understand science and the nature of the phenomena under investigation without direct experimentation (National Research Council, 2012). Working with this methodology implies that the pupils must be capable of both formulating scientific questions and defining the problem under investigation. It also entails: planning and development of investigations; analysis and interpretation of the data; use of transversal content, such as knowledge of mathematics and ICTs; scientific explanation of an event; development of models; evaluation of the results, by summarizing the available information; and communication. Thus, scientific inquiry helps pupils to learn curriculum-related contents, in which they become the leading players within the teaching/learning process, with differing forms of exploring and confronting the same problematic area (Couso-Lagarón, 2014).

Besides, within the multicultural European context, European institutions have, since 1990, been trying to promote the development of new approaches for the improvement of language competences for all citizens. In this context, CLIL proposes the teaching of subject-matter in a foreign/second language, simultaneously seeking to achieve two objectives: the learning of content and of a language (Eurydice, 2006). In this way, contents are treated in an interdisciplinary manner, which entails greater motivation on the part of the pupils and the development of critical thought (Darn, 2006; Lasagabaster and López Beloqui, 2015; Garzón-Díaz, 2018). The essence of the integrated curriculum is based on a strong dependence between language and content, the fruit of coordination and team work among the teachers involved in that teaching (Lova Mellado and Martínez, 2015; Nikula et al., 2016). Hence, a quality index that can ensure good functioning of bilingual programmes is evident when there is a high degree of coordination between teachers from linguistic and subject–matter areas (Halbach, 2008; Lova Mellado and Martínez, 2015; Sanz de la Cal et al., 2018). However, this approach when applied to the teaching of science in English implies great challenges for teachers, as Espinet et al. (2017) and Espinet et al. (2018) mentioned. Teachers imparting science in a FL have to make use of both their scientific competence and their level of language at the same time, in order to develop the official curriculum. Grandinetti et al. (2013) suggested that too much emphasis is usually placed on the linguistic competence of teachers, which has led to an erroneous conception of the principles established by CLIL, when thinking that it is only a matter of “doing it in English” (p. 355).

Grandinetti et al. (2013) proposed content-driven English-based learning tasks in science contents, following the principles underlined by Ting (2011): to know whether the input language is comprehensible for pupils, both at an oral level and in relation to the materials and the books that are used. If that were so, it would also be necessary to take account of their content; in other words, whether the content is accessible and intelligible to the learners. Were it not so in one (or in both) cases, the language or the content would have to be rewritten, in such a way as to move on to the next level.

Along these lines, joining the two approaches appears promising: on the one hand, CLIL—for the teaching of subjects in a FL—and IBSE—for the teaching of science. Because of its characteristics, the inquiry-based methodology, as well as being effective for science teaching, helps by providing a large number of opportunities in real situations for communicative interaction. The children develop skills, strategies and competencies in the FL, as well as vocabulary, grammar and spontaneity. That hybridization process strengthens the acquisition and the development of scientific literacy when “students need to use the CLIL language to communicate their findings and articulate their findings” (Garzón-Díaz, 2018, p.4).

In consequence, contextualized learning is promoted, as the activities that are developed are related with objects, processes, and experiences that occur in a specific environment (Stoddart, Pinal, Latzke and Canaday, 2002). Thus, inquiry-based and FL learning have a synergetic effect: if the language is taught in an effective way, it improves scientific learning and, in turn, the effective instruction of scientific content strengthens and stimulates the development and the learning of the language, promoting the development of superior thinking skills (Bruno-Jofré and Cecchetti, 2016; Nargund-Joshi, and Bautista, 2016; Espinet et al., 2017; Garzón-Díaz, 2018). Linguistic competences will increase when students demonstrate their science understanding in a FL and as language skills increases, subject matter knowledge will also improve (Nargund-Joshi and Bautista, 2016).

The importance of non-verbal communication to these processes may be highlighted, specifically “gestures” when the implementation of IBSE follows the principles of CLIL. Gestures permit the establishment of a connection between verbal and non-verbal forms of communication, which not only facilitate comprehension but also learning. There is evidence to indicate that gestures can strengthen the development of language in early infancy, predicting subsequent peaks in the development of a language (Farkas, 2007). In addition, when children learn a new language, they use semiotics and they establish relations between work and materials used in scientific activity, increasing and diversifying the number of functions that were used, thereby facilitating the integration of content and language (Ramos and Espinet, 2011).

It may be pointed out that there are practically no studies that explore methods of teaching science in a bilingual context in primary education in Spain. From among the few available studies, we may highlight the works of Valdés-Sánchez and Espinet (2013), Valdés-Sánchez et al. (2013), Espinet et al. (2018), in which the effectiveness of co-teaching stands out, among teachers of English and sciences, as a training tool and for the construction of didactic CLIL sequences. The SciencePro project (Izquierdo et al., 2016), together with IBSE and English learning in primary education programs (Espinet et al., 2017) all attempt to introduce improvements in the knowledge of in-service and future teachers and their aptitudes and attitudes for the teaching of the natural sciences in a FL, using active methodologies for science teaching. Further studies are needed, due to the scarcity of research, to improve pre-service primary teachers’ skills at using the IBSE + CLIL approach.

This qualitative study used a case study approach to gain a holistic perspective (Gummesson, 1991; Yin, 2003) and a deep understanding on the extracurricular activity Saturdays of Science, where the proposed CLIL + IBSE approach was used. The case is constituted by the three workshops developed in English in this activity during the academic year of 2017/18.

The previously proposed approach, merging IBSE and CLIL, was implemented in a series of workshops, integrated in an extracurricular activity known as Saturdays of Science (Greca et al., 2020). This activity, now in its eight edition, is organized by the University of Burgos one Saturday every month. The aim is to stimulate the development of scientific-technological vocations among children between 6 and 11 years old and to improve the training of its pre-service teachers following the Bachelor’s degree in Primary Education. In the workshops, who are organized and led by pre-service teachers, children develop a small experimental inquiry-based project on a topic of Spanish curriculum for science during 2-and-a-half hours. The pre-service teachers’ participation is voluntary.

In the academic year 2017/18, workshops in English were incorporated onto Saturdays of Science which also offer workshops in Spanish. The target of this study is the workshops developed in English (WL2) by pre-service teachers with a mention in English. The children who participate in them attend bilingual education schools. Over three Saturdays, the WL2 cover “forces and movement”, centred on a problem concerning catapults. A WL2 was added on the third Saturday on “chemical reactions”, hinging on a problem concerning volcanos. The workshops were initially designed to integrate the IBSE + CLIL approach. The structure is based on a brief gamified explanation of the parts of an inquiry and the presentation of a problem situation by the pre-service teachers, followed by the production of hypotheses, the planning of the experiments and their development and the extraction of some simple conclusions (groupwork completed by children with the help of the pre-service teachers). The pre-service teachers always tried to communicate in plain and simple English; the children spoke in English when some points were explained in large groups or when they addressed the teachers, but Spanish could be spoken when undertaking the tasks in small groups.

Previous to the workshops, pre-service teachers have an Innovative methods in Science Education course (where IBSE was addressed) as well as a separate Didactics of English course, where they learn about CLIL in the Bachelor’s degree in Primary Education. They receive no special training for the workshops; but they have to organize them in previous weeks. This is done in groups, in which there is always an experimented student who had already worked on Saturdays of Science. The pre-service teachers are taken and mentored by Bachelor’s Degree lecturers of Didactics of Experimental Sciences. After each session, a global evaluation and reflection were completed by the pre-service teachers along with the university teachers, in order to introduce the necessary improvements, considering the aspects that had not been worked properly, fostering the improvement in pre-service teachers’ performance skills.

Through the present study, the aim is to respond to the following questions in the above-mentioned context:

- How might IBSE + CLIL be implemented for a successful result in an extracurricular activity?

- Did the participation in this activity change the attitudes towards CLIL + IBSE approach of the Primary pre-service teacher trainees who supervise the WL2?

We studied the participants in seven workshops throughout three consecutive Saturdays of Science. Thus, the sample was composed by 17 pre-service teachers in charge of the WL2 and 102 pupils from different schools from the province of Burgos (the children were organized into groups of 15–18 pupils) (Table 1). Related to the participation, 15 pre-service teachers participated in all three Saturdays and two in only one of them. In relation to their previous experience, 5 pre-service teachers had previously participated in workshops taught in Spanish, having so previous experience of the use of IBSE in Spanish; all the rest, had no experience with IBSE at the beginning of the activity. We also interviewed two pre-service teachers who were not participating in this extracurricular activity, in order to compare their perception of the difficulties to teach science using the CLIL + IBSE approach.

In order to obtain a detailed description, various instruments were used to collect information, namely systematic observation, field notes, a survey and interviews:

Systematic observation with a view to analysing the way in which the pre-service teachers developed the workshops and the behaviour and the attitudes of the pre-service teachers and the children attending the WL2, to determine the factors that influenced the development of the sessions that combined IBSE and CLIL. To do so, an estimation scale that converted the observations into degrees of intensity, frequency, etc. was used, thereby constituting a categorical system. The scale was firstly prepared using the literature on the use of both CLIL and IBSE, performing a careful selection of the most significant features, which had to correspond to observable behaviours. In particular, we used the rubrics related to inquiry methodology proposed by the SAILS project as well as the proposals for CLIL from the works of Farkas (2007); Ting (2011), and Grandinetti et al. (2013), among others. The final scale (available in the Supplementary Material) was obtained after the analysis of the results of the first WL2 and discussion with two professionals: the coordinator of the Saturdays of Science, an expert in IBSE, and the consultant from the communicative linguistic area from the CFIE [Centre for teacher training and educational innovation] in Burgos, a CLIL specialist. The final scale has a total of 52 items, of which 33 analysed features of the pre-service teachers, dividing those items into the following sub-scales: didactic strategies, verbal language, non-verbal and paraverbal language, and scientific competence. Besides, there were a total of 19 items in connection with the pupils, through which attitude, motivation, verbal and on/verbal language and comprehension were analysed. Each one of the items was measured on a 5-point Likert type scale. If expressed as a function of the frequency of appearance of a behaviour, etc., the item was assessed as never (1); rarely (2); often (3); very often (4); and, often (5). Those items referring to the level or the competence were set as very low (1), low (2), medium (3), high (4), and, very high (5). This estimation scale was used throughout the duration of every WL2. This scale was applied in the WL2 by two of the authors of this paper: one, a pre-service teacher who participated in the workshops and the other, by the coordinator of the activity.

A field notebook: to complement the data from the scale. The most relevant aspects were noted, mainly in a descriptive style, seeking to avoid valued judgements. The field notes were taken by the researchers involved in observing the workshops. In the case of participatory observation, the notes were taken as promptly as possible.

A survey: After each WL2, the children completed a simple survey composed of five questions, four of them related to their perceptions about the WL2. The last one was a single select multiple-choice question to assess their understanding of the issues addressed at the WL2 (an example is available in the Supplementary Material). The survey was analysed using descriptive statistics.

Semi-structured interviews: Data relating to the previous ideas of the pre-service teachers, their conceptual views of both science and English, their prejudices towards both, and their assessment of the experience and the methodologies they used were obtained through a semi-structured interview, composed of 11 questions (available in the Supplementary Material), that are included in the supplementary material. The interviews were administered to a total of 7 pre-service teachers, two of whom had not and five of whom had participated in the Saturdays of Science (from the 17 that participated). The pre-service teacher involved in the systematic observation conducted the interviews, that lasted half an hour. Those interviews were analysed using thematic analysis (Paillé and Mucchielli, 2003).

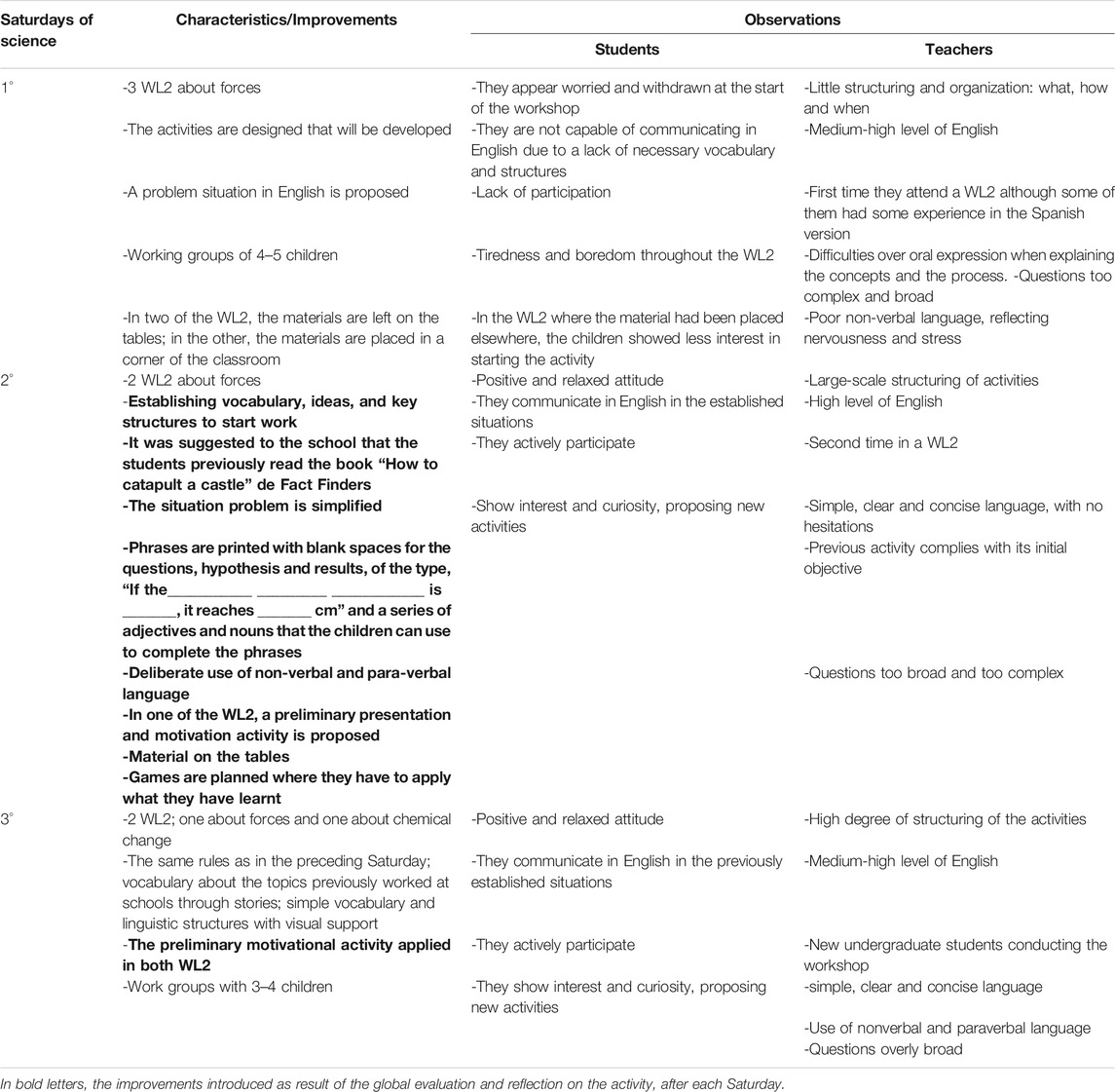

In the first place, we will present the main results obtained from the observation as well as the changes that were successively introduced after the global evaluation that followed each implementation. This global evaluation was led by the coordinator with the participation of all the pre-service teachers who were in charge of the WL2. In Table 2, the characteristics of each WL2 are detailed, as is a brief description of the behaviours and the attitudes of the pupils and the pre-service teachers. This description was obtained from the systematic observation and the field notes. Also, as indicated, Table 2 highlights the changes that were introduced for improving the WL2.

TABLE 2. Main characteristics of the WL2 of each Saturday of Science and observations from field notes and systematic observation.

As shown in the Table, in the first session, pre-service teachers hadn’t prepared a structured and dynamic session and neither linguistic visual support and, in general, they seemed not to have reflected on the English level and its interaction with the scientific activity. Neither previous work on the specific vocabulary was required to be done at the schools. As a result, students couldn’t communicate in English and were bored, increasing pre-service teachers’ insecurities. These difficulties coincide with (Grandinetti et al., 2013) as the workshops were only carried out in English without following some of the CLIL principles as no visual and language supports were planned during the workshop.

So, the changes introduced through the sessions were aligned with the proposals of Ting (2011): greater structuring of the workshops in terms of content and material distribution; selection of a simpler vocabulary adapted to the level of English of the children and greater use of non-verbal and para-verbal communicative elements. The groups were also reduced; games for evaluation were introduced as well as the use of colourful printed material for the different steps of an inquiry and for the linguistic structures related to IBSE (as the structures for formulating a hypothesis, results, and conclusion) that the children had to complete. In addition, it was suggested to the participating schools that, before attending the workshops, the children were introduced to some English vocabulary directly related to the WL2 (with a fiction or non-fiction book). All these changes aimed to reduce the gap between the levels of English of the children and the pre-service teachers. Subsequently, the self-confidence of the pre-service teachers could be noted, as well as an increase in both the participation and the motivation of the children towards the WL2. This is reflected in a substantial improvement, both of their assessment of the workshop and their comprehension of the topics that were covered, as shown in the survey. Thus, the percentage of correct responses to the knowledge questions rose from 63.4% on the first Saturday, to 84.2% on the second Saturday and 82.3% on the third Saturday. Also, 80.6% of the children said that they liked the workshop a lot on the second Saturday as opposed to 54.8% on the first Saturday (Mata-Torres, 2018).

In Graph 1, we present the evolution (through the values obtained with the estimation scale) of 3 pre-service teachers during the different WL2. They were selected because they are representative of the experience and participation of the group: Pre-service one participated in the three three WL2s and had previously participated in workshops taught in Spanish; Pre-service two also participated in the three WL2s, but had no previous experience with IBSE; and Pre-service three only participated on the third Saturday, but had previously participated in workshops taught in Spanish. On the first Saturday under analysis, out of a maximum possible score of 265, Pre-service one obtained 181 (the highest score obtained by any pre-service teachers that Saturday), while Pre-service two achieved the lowest, 129. After having introduced the modifications, the scores were seen to increase in the second WL2, rising to 230 in the first case and to 216 in the second. It is striking that as the improvements were established not only did both pre-service teachers improve, but the distance between them was reduced. Moreover, new pre-service teachers in the third Saturday that never had participated in WL2, but applying the same methodological principles, obtained scores between 207 and 213 (only Pre-service three is shown in Graph 1), similar results to those of the second Saturday. Together these results seem to show that the changes adopted since the second Saturday were useful for implementing the CLIL + IBSE efficiently, at least in this extracurricular activity.

The evolution of children’s attitudes and performance at the WL2, as result of the changes introduced, seems to indicate the relevance of the pupil profiles, both at the level of contents and FL, so that the input may be accessible. The understanding of what they are studying is not enough for the children, as they themselves must be capable of using the language in an effective manner. To do so, it is essential to previously introduce them to the vocabulary and the necessary linguistic structures within a real and authentic context as with non-fiction and fiction books, so that everybody can intervene actively in the development of the session. Equally, in order to develop inquiry-based investigations, children have to be able to follow the relevant processes. In other words, the balance must be sought between the language and the contents, maximizing the strengths of both as a result. It was noted that this approach is also adaptable to those pupils with a lower level, although the rhythm must be relaxed to do so, repeating exercises a greater number of times, with the support of existing materials.

The conscious and increasing use of non-verbal and para-verbal communicative elements by the pre-service teachers was also one of the decisive elements to increase communication and comprehension with the children and it is also reflected in the scores obtained. In particular, pre-service teachers became aware of the relevance of expressive facial gestures, that prepare pupils to observe certain nuances that cover the global meaning of the communication. Also, the relevance of the voice, the mode in which it is modulated, rhythm, repetitions, cadence, and silences play an important role when a new language is learnt, as those elements emphasize the most relevant aspects. In this sense, the pre-service teachers that participated in the WL2 tried to avoid overly rapid rhythm, extending certain words, pronouncing others with greater emphasis and repeating the number of times that it may be necessary to confirm that each and every one of the pupils who find themselves in the classroom understand the point of the work.

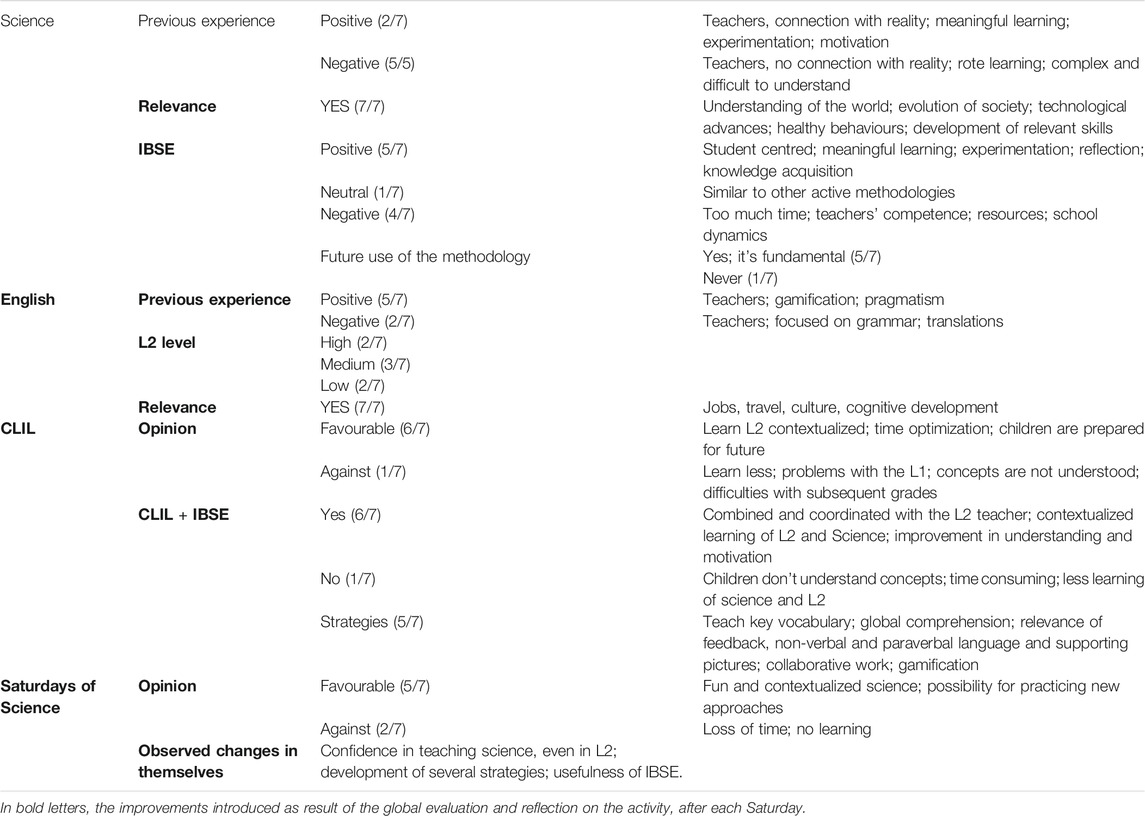

In order to answer to research question 2, we interviewed 7 pre-service students, five of whom developed WL2 and two who had not participated in Saturdays of Science. The summary of the categories obtained from the thematic analysis of the interviews are shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3. Pre-service teachers’ opinion on science, English, Content and Language Integrated Learning and Saturday of Science. The number of subjects in each category appear in parentheses.

As can be seen, the pre-service teachers had contrary experiences of science and English learning, which coincides with the narratives obtained by Espinet et al. (2018). Nevertheless, all of them considered that science is fundamental in order to understand the world that surrounds us and the functioning of life, including references to the improvement of the capability of learning to learn. But only those whose experience with science was good considered that they had a greater capability of developing teaching through IBSE, while the other group expressed greater insecurity in that respect. As for inquiry, many referred to the change that they have observed in their own conceptualization of inquiry during their time at university and, above all, thanks to the activity of Saturdays of Science, although they all continued to see the amount of time needed for its preparation as a negative aspect.

As regards bilingualism, they all agreed on its relevance in an environment characterized by globalization, but they also thought that it had not been properly implemented in Spain. In relation to the perceived level of English and the capability to develop a CLIL class, the presence of quite an extensive belief of a subjective perception stood out of not having a good enough level to be able to deliver a CLIL class, also maintained by pre-service teachers with high levels of linguistic competence. They thought that they needed a very wide range of vocabulary, as much as in their mother tongue, to be able to offer varied explanations.

On the other hand, there were those who attributed greater importance to the available methodological techniques and strategies, in particular the ones developed in the WL2. They considered that as they did not have such a high level of English, the same structures were usually repeated, which simplified comprehension:

E3: It is not that I have the best level in the world, far from it … But I think that throughout my career and … , above all, from these WL2 I have learnt many tools to face up to that job. And I believe that not having such a high level, well, you can adapt better. I don’t know, it’s as if the level is more similar, it’s not so difficult and you take care, I don’t know how to say it, everything you say and the way you say it.

Likewise, there is the perception that the teachers are not sufficiently well trained to teach in bilingual contexts, because of a lack of knowledge at a theoretical, methodological and practical level. Two clear stances were observed whenever the topic of CLIL was discussed. Some defended the approach because they consider that contextualized learning prepares children better for the future and, also, optimizes time. On the opposite side, others defended the contrary stance, focusing in the non-acquisition of contents, and neither learning the language nor the area.

All the pre-service teachers who participated in the Saturdays of Science considered that they had changed their perception of the methodologies in use, having now acquired a larger number of strategies and didactic tools which motivate them to overcome their fear of FL teaching. It was also important for them to learn from direct observation of the actions carried out by other colleagues. As the same WL2 was repeated over time, they could introduce improvements, and propose new challenges.

E5: You can change things. Like, the way to carry out the same workshop, you propose improvements and you try to see what works and what doesn’t. It’s what you have to do constantly in class, but without the need to have to wait a whole year to introduce those improvements in that topic […].

All the pre-service teachers who participated agreed that they would use IBSE for teaching science in a FL context. They even mentioned that they cannot conceive the teaching of sciences in any other way. However, among those who have not participated in the workshops, the approach is not so clear. One of them said he would not use it (E7: it is difficult enough for children to develop an inquiry, but to have to do it in English!) and the other thought that it is highly beneficial for pre-service teachers, although difficult to introduce over the long term.

This paper explores and describes a proposal of using an integrated CLIL + IBSE approach that seems to help children to work on and learn English and science at the same time (Nargund-Joshi and Bautista, 2016; Garzón-Díaz, 2018; Espinet et al., 2018). The WL2 that were developed began on each occasion with careful planning and a practical implementation, accompanied by systematic observations, and followed up with analysis and reflection by the coordinator of the activity and pre-service teachers. The results showed that the introduction of changes and their analysis in the development of WL2, in view of those improvements and the degree of their effectiveness, yielded a series of methodological principles that facilitated the development of the teaching/learning hybridization process of CLIL + IBSE. Moreover, the re-adaptation and the re-evaluation during the development of teaching practice were essential, for a swift introduction of the necessary changes and, by doing so, the maximization of the adaptation of the pre-service teachers. This methodology coincides with the proposals of Kelly et al. (2004) who stressed the importance of offering training scenarios to future teachers. It is also one of the European indicators of foreign-language teacher training quality that refers to the development of reflective practice and self-evaluation of teaching practice, which is the case of our study. The scheme proposed by Ting (2011) was useful for the re-adaption process, helping to determine which aspects must be changed and whether those aspects refer to language or to content.

With regard to the effects of participation in this activity among the pre-service teachers, pedagogical improvements in their use of the CLIL + IBSE approach have been observed in them all. Although experience is key to their development, knowledge of tools and strategies is a basic pillar. For example, the pre-service teachers’ FL language level was not raised as a key element, provided that it was sufficient to communicate efficiently. Some pre-service teachers who had a lower English level and used simpler structures that repeated assiduously, managed to make that the pupils could follow the development of the workshop with greater ease. However, pre-service teachers with a higher level were compelled to develop new skills in order to be able to adapt to the level to the pupils.

Better structured WL2 were developed after the reflection and discussion of first implementation among the pre-service teachers and the coordinator of the activity in order to improve the global communication during the WL2. Scaffolding strategies were introduced to support children’s language and also the science contents in a foreign language as they used more visual resources related to IBSE process, games for evaluation, the use of non-fiction or fiction books. As a consequence, pre-service teachers were aware of the increase of students’ participation and communication in the WL2, their self-confidence and students’ understanding of the science topics.

Moreover, the self-confidence of teachers is transferred to learners, conditioning the teaching/learning process. Taking into account both the uncertainties and the fears that are developed throughout life in relation to a FL, this aspect can be decisive (Horwitz et al., 1986; MacIntyre and Gardner, 1989). In our study, many pre-service teachers, despite having the necessary skills, underestimated their capacities, showing themselves to be insecure and doubtful during the WL2. However, these aspects improved with practice, as has been confirmed in the scores obtained from the scales. In other words, the pre-service teachers have been gaining confidence in the application of IBSE + CLIL, especially after the restructuring of the workshops that left them feeling secure. Although earlier investigations referred to the effect of a low-level of linguistic competence in the FL that can directly affect insecurity and low confidence of the teachers to develop CLIL teaching (Pena Díaz and Porto Requejo, 2008; Lorenzo et al., 2009), our results showed that a good level of FL competency is insufficient in itself. It is necessary to complement the FL competency with training in the CLIL approach applied to specific content methodologies, in this case, IBSE. It also seems important to train pre-service teachers in the use of non-verbal and paraverbal language, which are some of the most important tools to facilitate comprehension (Hillyard, 2011). Results show how pre-service teachers became aware of the importance of the expressive facial gestures, repetitions, the role of the voice as CLIL principles as they facilitate global communication. These aspects are not usually emphasized on training courses, but are instead learnt from teaching experience and through observing other teachers, to which the pre-service teachers specifically referred in the interviews.

It cannot be overlooked that WL2 are of short length and involve children from different schools and so, the capacity to adapt to the characteristics of the pupils is reduced, because each group is different and there is no prior knowledge of how a group will interact. However, the Saturdays of Science workshops were a training lab to reflect and learn about the integrative CLIL and IBSE approach and promote change in pre-service teachers from a reflective practice, as by looking closely at the potential of certain methodologies, they can realize that their use is neither utopian nor unreal in pre-service teacher education. So, it is worth stressing that this non-formal activity helped improve the feelings of the pre-service teachers towards the value and the utility of science and science education through the promotion of context-based science teaching, as proposed by Espinet et al. (2018). We would like to highlight that in 2020, this integrative CLIL and IBSE perspective for teacher training has acquired an international dimension with the approval of the European Erasmus + Project. SeLFiE: “STEAM Educational Approach and Foreign Language Learning in Europe,” led by the University of Burgos, and which will work jointly with the International Trilingual School of Warsaw (Poland), Teacher Training and Educational Innovation Centre of Burgos (Spain), University of Malta (Malta), Kveloce I + D + i- Senior Europa SL (Spain) and the University of Granada (Spain) to work together in the improvement of CLIL competencies from an integrative CLIL and IBSE approach in pre-service and primary school teachers.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because privacy restrictions. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to SM-T, c3VzbWF0NkBnbWFpbC5jb20=.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Comisión de Bioética-Universidad de Burgos. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.735158/full#supplementary-material

Bruno-Jofré, R., and Cecchetti, A. (2016). Teacher Education at the Intersection of Educational Sciences. Eur. J. Res. Reflection Educ. Sci. 4 (8), 1–6. doi:10.1007/978-981-287-532-7_10-1

Couso-Lagarón, D. (2014). “De la moda de “aprender indagando” a la indagación para modelizar una reflexión crítica”. Communication presented at the 26 Encuentros en Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales. Spain: Huelva.

Darn, S. (2006). Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL): A European Overview. ERIC. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED490775 (Accessed January 22, 2020).

Espinet, M., Valdés-Sanchez, L., and Hernández, M. I. (2018). “Science and Language Experience Narratives of Pre-service Primary Teachers Learning to Teach Science in Multilingual Contexts,” in Global Developments in Literacy Research for Science Education, (Cham: Springer) 321–337. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-69197-8_19

Espinet, M., Valdés-Sánchez, L., Carrillo Monsó, N. C., Farró Gràcia, L., Martãnez Vila, R., López Rebollal, R., et al. (2017). “Promoting the Integration of Inquiry Based Science and English Learning in Primary Education through Triadic Partnerships,” in Science Teacher Preparation in Content-Based Second Language Acquisition. Editors A. W. Oliveira, and M. H. Weinburgh (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing), 287–303. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-43516-9_16

Eurydice (Editor) (2006). Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) at School in Europe (Belgium: European Commission).

Farkas, C. (2007). Comunicación Gestual en la Infancia Temprana: Una Revisión de su Desarrollo, Relación con el Lenguaje e Implicancias de su Intervención. Psyke 16 (2), 107–115. doi:10.4067/S0718-22282007000200009

Garzón-Díaz, E. (2018). From Cultural Awareness to Scientific Citizenship: Implementing Content and Language Integrated Learning Projects to Connect Environmental Science and English in a State School in Colombia. Int. J. Bilingual Edu. Bilingualism 21, 1–8. doi:10.1080/13670050.2018.1456512

Grandinetti, M., Langellotti, M., and Ting, Y. L. T. (2013). How CLIL Can Provide a Pragmatic Means to Renovate Science Education - Even in a Sub-optimally Bilingual Context. Int. J. Bilingual Edu. Bilingualism 16 (2), 354–374. doi:10.1080/13670050.2013.777390

Greca, I. M., Diez-Ojeda, M., and García-Terceño, E. (2020). Evaluación del Impacto Social de un Proyecto de Educación no Formal en Ciencias. Educaçao e Sociedade 41, e230450–374. doi:10.1590/ES.230450

Halbach, A. (2008). Una metodología para la enseñanza bilingüe en la etapa de Primaria. Revista de Educación 346, 455–466.

Hillyard, S. (2011). First Steps in CLIL: Training the Teachers. laclil 4 (2), 1–12. doi:10.5294/laclil.2011.4.2.1

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., and Cope, J. (1986). Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety. Mod. Lang. J. 70 (2), 125–132. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x

Izquierdo, N. B., Sanz Trigueros, F. J., Calderón Quindós, M. T., and Alario Trigueros, A. I. (2016). SciencePro Project: Towards Excellence in Bilingual Teaching. Estudios sobre Educación 31, 159–175. doi:10.15581/004.31.159-175

Kelly, M., Grenfell, M., Allan, R., Kriza, C., and McEvoy, W. (2004). European Profile for Language Teacher Education: A Frame of Reference. Final Report. A Report to the European Commission Directorate General for Education and Culture. Brussels: European Commission.

Lasagabaster, D., and López Beloqui, R. (2015). The Impact of Type of Approach (CLIL versus EFL) and Methodology (Book-Based versus Project Work) on Motivation. Porta Linguarum 23, 41–57. doi:10.30827/digibug.53737

Lorenzo, F., Casal, S., and Moore, P. (2009). The Effects of Content and Language Integrated Learning in European Education: Key Findings from the Andalusian Bilingual Sections Evaluation Project. Appl. Linguistics 31 (3), 418–442. doi:10.1093/applin/amp041

Lova Mellado, M., and Martínez, M. J. B. (2015). La coordinación en programas bilingües: las voces del profesorado. Aula Abierta 43 (2), 61–110. doi:10.1016/j.aula.2015.03.001

MacIntyre, P. D., and Gardner, R. C. (1989). Anxiety and Second-Language Learning: Toward a Theoretical Clarification. Lang. Learn. 39, 251–275. doi:10.1111/j.1467-1770.1989.tb00423.x

Mata-Torres, (2018). La Enseñanza Integrada de la indagación científica en una lengua extranjera. Trabajo de Fin de Grado. Universidad de Burgos

Nargund-Joshi, N. J., and Bautista, N. (2016). Which Comes First--Language or Content? Sci. Teach. 83 (4), 24–30. doi:10.2505/4/tst16_083_04_24

National Research Council (2012). A Framework for K-12 Science Education: Practices, Crosscutting Concepts and Core Ideas. Washington: The National Academies Press.

Nikula, T., Dalton-Puffer, C., Llinares, A., and Lorenzo, F. (2016). “More Than Content and Language: the Complexity of Integration in CLIL and Multilingual Education,” in Conceptualising Integration in CLIL and Multilingual Education. Editors T. Nikula, E. Dafouz, P. Moore, and U. Smit (Bristol: Multilingual Matters).

Paillé, P., and Mucchielli, A. (2003). L’analyse qualitative en sciences humaines et sociales. Paris: Armand Colin.

Pena Díaz, C., and Porto Requejo., M. D. (2008). Teacher Beliefs in a CLIL Education Project. Porta Linguarum 10, 151–161. doi:10.30827/digibug.31786

Ramos, S. L., and Espinet, M. (2011). “The Multiple Voices of agency: Multilingual Science Classrooms for Pre-service Science Teachers,” in 2011 NARST Annual International Conference, Orlando, Florida, USA, April 3-6, 2011 (EUA).

SAILS (2020). Strategies for Assessment of Inquiry Learning in Science. Available at: http://www.sails-project.eu/(Accessed January 20, 2020).

Sanz de la Cal, E., Muñoz, R. C., and Portnova, T. (2018). “Evaluación de los programas bilingües de Secundaria de Castilla y León,” in Influencia de la política educativa de centro en la enseñanza bilingüe en España. Editors J. L. Ortega-Martín, S. P. Hughes, and D. Madrid (Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte), 79–90.

Stoddart, T., Pinal, A., Latzke, M., and Canaday, D. (2002). Integrating Inquiry Science and Language Development for English Language Learners. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 39 (8), 664–687. doi:10.1002/tea.10040

Ting, Y. L. T. (2011). CLIL Not Only Not Immersion but Also More Than the Sum of its Parts Not Only Not Immersion but Also More Than the Sum of its Parts. ELT J. 65 (3), 314–317. doi:10.1093/elt/ccr026

Valdés Sánchez, L., and Espinet, M. (2013a). Ensenyar ciències i anglès a través de la docència compartida. ciencies 25, 26–34. doi:10.5565/rev/ciencies.91

Valdés Sánchez, L., Espinet, M., Aguas, M., and Dallari, L. (2013b). La evolución de la co-enseñanza de las ciencias y del inglés en educación primaria a partir del análisis de las preguntas de las maestras. Enseñanza de las ciencias, 3588–3594.

Keywords: CLIL, IBSE, workshops, primary, pre-service, teaching

Citation: Mata-Torres S, Sanz de la Cal E and Greca IM (2022) Saturdays of Science. An Experimental Learning and Training Scenario in CLIL and IBSE: A Case Study. Front. Educ. 6:735158. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.735158

Received: 02 July 2021; Accepted: 30 December 2021;

Published: 28 January 2022.

Edited by:

Margaret Grogan, Chapman University, United StatesReviewed by:

Letizia Cinganotto, Istituto Nazionale di Documentazione Innovazione e Ricerca Educativa, ItalyCopyright © 2022 Mata-Torres, Sanz de la Cal and Greca. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Esther Sanz de la Cal, ZXNhbnpAdWJ1LmVz

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.