- 1Curriculum and Instruction, School of Education, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, United States

- 2Department of Human Development and Quantitative Methodology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, United States

As the world experienced the COVID-19 outbreak, education was one of the multiple systems that were hit hard. We explored the consequences of the reconfiguration of schooling based on the experiences of the educational stakeholders caught up in the sudden transition to virtual schooling during COVID-19. Using Bronfenbrenner’s (1976) Ecological Systems framework, we underscored the complexity of the individual’s socio-cultural world and the myriad influences that impact the individual’s growth to examine how agents involved in the educational system have dealt with this unanticipated crisis academically, personally, socially, and emotionally. People can endorse contradictory positions on the same policy. Recognizing that multiplicity of voices might bring a different perspective, we captured various voices—an administrator leading the teachers’ professional development, a public-school elementary teacher, and a parent with two kids. Using unstructured interviews, we unpacked the narratives and counter-narratives of the participants to unpack “what worked” and “what did not work” during virtual learning and teaching environment. The voices centered in this article offer a rich source of insight into challenges faced by those who are at the forefront of the educational crisis—teachers and parents. The results showed how various communities cooperated to deal with such unprecedented times while maintaining the responsibility of educating children. The key trends that emerged from our qualitative investigation were: 1) development of collaboration among teachers as they transitioned into virtual teaching, 2) flexibility of the school leaders to assist the teachers in this new instructional modality, and 3) parents’ acknowledgment of the teachers’ efforts to assist their children.

… there was a video where one person said, “Okay, the next thing you need to do is fold the eggs”. And the other person is like, “what do you mean fold the eggs? How you want me to fold the eggs? Do I mix it in the batter? Should I take a spoon or a fork? Like what do you mean, fold the eggs?” It was interesting that you could take that scene and relate it to teaching during COVID.

Introduction

These thoughts were shared by one of the educational stakeholders we interviewed about their experiences with virtual schooling during COVID-19. Although tongue-in-cheek, this drew an association between the confusion caused by sudden mandates to alter teaching practices and the bewilderment of a person trying to follow unclear cooking directions. As the world experienced the COVID-19 outbreak, education was one of the multiple systems that were hit hard. By May 2020, around 85% of schools were closed worldwide (The World Bank, 2020). This situation led to students taking online classes, alongside many parents who had either been laid off or were working from home. The teachers, many of whom are parents themselves, had to manage a new way of teaching along with maintaining family responsibilities. Educational stakeholders could not have anticipated a crisis of this magnitude and had very little time to develop strategies for dealing with it.

To mitigate the long-term impacts, many adaptations were implemented, following Centers for disease Control guidelines, as schools shifted into the online instructions. Most education departments provided a set of best practices, but those recommendations were not necessarily clear for everyone nor applicable to every school. Hence, administrators were left to devise their own standards and regulations as the crisis continues to unfold. The ambiguity of guidelines led to a confusing array of solutions, i.e., everyone started to fold their eggs differently.

Recognizing that multiplicity of voices might bring a different perspective, we captured various voices—an administrator leading the teachers’ professional development (PD), an elementary teacher, and a parent. We report their narrative and counter-narratives to underscore how they dealt with this crisis personally, socially, and emotionally while maintaining the responsibility of educating children.

Theoretical Framework

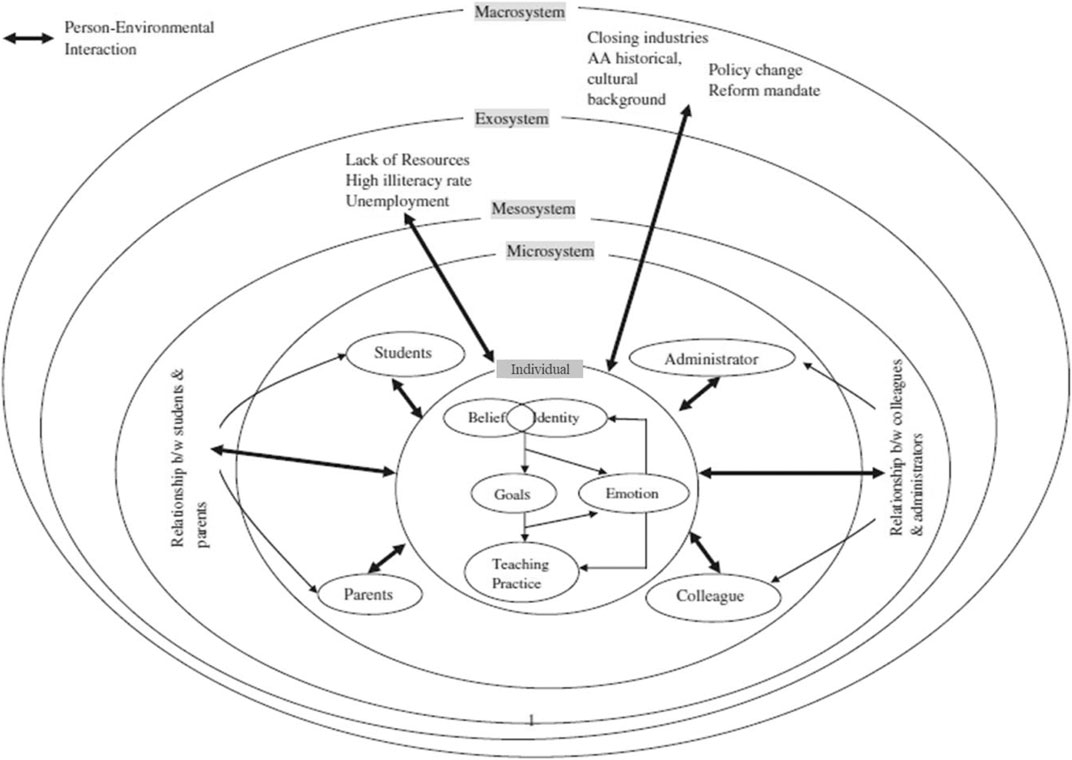

We used Bronfenbrenner, (1976) to underscore the complexity of the individual’s socio-cultural world. This framework situates the individual within an interconnected system of relationships among nested environments (Figure 1). Within the microsystem, an individual has constant interactions among others in the system. These relationships have multi-directional and reciprocal connections. Mesosystem has distal relations (e.g., teacher-student, teacher-parent, etc.) as it includes the community in which the individual is nested.

FIGURE 1. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Framework (Cross and Hong, 2012, p. 959).

An individual may or may not interact directly with the exosystem, but it cast an impact on his/her immediate setting. For instance, the shift to virtual instruction has changed the way the teachers’ practice and parents perceive schooling. The macrosystem refers to the legal, political, and economical spheres governing an individual’s life. The “school to prison pipeline” phenomenon is a prime example of the impact of governmental policies on what happens within schools and with the individual learner.

We utilized these sub-systems to comprehend the experiences of the educational stakeholders as caught up in the sudden transition to virtual schooling. Current education programs such as school choice or curriculum changes are subject to the complex dynamics of relationships between multiple stakeholders. Thus, we explored the entanglement of these relationships using Bronfenbrenner’s framework while unpacking internal (e.g., emotions) and external (e.g., relations with others) factors that influence an individual’s experiences.

The intended audience for this study is educational researchers, as we put forward the voices of the first responders within our schools teachers and parents. We realize that a policy does not lead directly to an educational impact—it first must flow through the implementation process. Hence, we assessed if the educational policies attained predetermined purposes by examining intended and actual consequences by examining stakeholders’ experiences.

Materials and Methods

The data was collected in the Fall of 2020 using unstructured interviews via Zoom. All three participants are from Midwestern United States, Leah, an administrator for teachers’ PD at the state-level; Kelly, a public-school elementary teacher; and Sarah, a parent of two school-aged children (all pseudonyms). The participants were selected using purposeful sampling. The authors designed an interview protocol so that the participants could communicate their experiences through personal stories. Each interview was video- and audio-recorded and lasted between 50 to 60 min. We chose qualitative inquiry to understand how same policies can have differential effects on the involved stakeholders. Having an open dialog with participants afforded us to comprehend the dynamics of policy implementation while foregrounding their voices situated within local contexts.

Data Analysis

The unit of analysis was the utterances of the stakeholders. We defined an utterance as a one-to-several sentence verbatim used to express one idea. To manage the magnitude of the overwhelming amount of information, we foregrounded the relevant utterances using Saldaña, (2016) descriptive coding method. Author 1 reviewed the transcripts line-by-line to identify common themes. The phrases were paired based on a common meaning using in vivo codes which allowed us to keep the interpretations close to the participants’ originally expressed meanings. To delineate any subjectivity that the authors brought to the interviews (Peshkin, 1988), the interviewees were asked to member-check the inferences (Patton, 2002).

Results

We considered each interview as an individual story providing insight into one’s lived experiences. The codes from the analysis are discussed under two main sub-themes: folding eggs to get an omelet—referring to the stakeholders’ positive experiences and folding eggs to get scrambled eggs—referring to the failure of policies to attain the intended outcomes.

Folding Eggs to Get an Omelet

Individual Level

The individuals within Bronfenbrenner’s framework constantly interacts with their own goals, beliefs, emotions, or identity which guides their actions. For the purposes of this paper, we focused specifically on emotions to assess stakeholders’ emotional turmoil as they navigated this journey.

Recent research has shown that COVID-19 has taken a toll on people’s well-being (Brown et al., 2020; Yang and Ma, 2020), which was also visible in our participants’ experience. One main response to the school shutdown by both Kelly (teacher) and Sarah (parent) was to call it a sudden shock. Both reported continuously updating themselves on the world situation and knew that things were turning bad. Initially, however, their districts were keeping the schools open until one evening they got the message to close the schools. This sudden change was hard as they had made no preparations for the next steps. Sarah shared her initial feelings of confusion,

…we got a message saying that we have confirmed reports that there is one case in XYZ district, and so we are switching to online after spring break. But we were not sure, how will that look? What will it be? (Sarah, 3:00–3:43).

Sarah expressed a sense of uncertainty about what schooling would look like on virtual platforms. Reflecting on her early experiences, Sarah said, “for the first week, I was so overwhelmed, because I didn’t want them (kids) to miss any classes. I felt that it's my role to make sure that they know what to do” (4:20–4:57). This highlights an increased pressure on parents as they had to take primary responsibility for their children’s education from a perspective different from their own but complementing that of the teacher (Cachón-Zagalaz et al., 2020). Indeed, recent research documented that parent are now seeking substantially more educational resources online compared to pre-COVID times (Bacher-Hicks et al., 2020).

Kelly described how the educational authorities raised their expectations, without acknowledging that the teachers were also trying to balance the transition in their lives. Kelly expressed feeling overwhelmed with work demands as she had to deal with an added responsibility of ensuring differentiated instruction for the families who could not afford devices necessary for online learning. Nevertheless, Kelly felt excited about learning new ways to teach,

… it’s a whole new adventure. I feel more joyful about teaching. Probably like I did at the beginning of my 29 years [of teaching] because I’m so happy to be here. It makes you appreciate what face to face learning and shared learning spaces are (31:00–31:22).

Kelly’s excitement (almost joy) about the quick transformation of the instructional delivery system was worth noting. All these new expectations triggered a range of emotions, from anxiety to excitement, in the participants’ personal and professional lives. Within Bronfenbrenner’s framework, Kelly and Sarah were positioned at a crossroads where they were adjusting to the stresses as well as managing an increased set of responsibilities.

Microsystem

Microsystem constitutes interpersonal relations experienced by an individual within a given setting. Kelly narrated her experiences that how she and her colleagues mutually understood the unknown territory in which they had been positioned. They rapidly transformed the curriculum or searched for novel ways to help students academically and socially. Being in her late fifties, Kelly was not familiar with the tech-tools, so she reached to her fellow teachers for support. She called her co-teacher, who was younger and comfortable with technology, as her savior: “… at times I had to swallow my pride a little bit and call her and say ‘I don’t know how to do this’” (7:38–7:49). Kelly’s expression of vulnerability (swallow my pride) exhibits a functional relationship to the teachers coming together.

These ideas highlight that the teachers appreciated a much more bi-directional relationship as teachers, like Kelly, leaned on their junior colleagues for technology-related assistance. They developed a community to provide quality instruction to their students. She expressed that the teachers felt comfortable with sharing resources as everyone felt adrift in the same boat. This reduced the competition among the teachers and explicated the emergence of a collective “we” or “us” owing to the shared experiences and sense of vulnerability.

Mesosystem

Kelly’s statements implicitly alluded to an existing phenomenon in the teaching profession—pedagogical solitude, a sense of isolation among teachers (Hargreaves, 2003). Research asserts that a collaborative culture can encourage teachers to support each other (Bharaj, 2019). However, cultivating such a culture depends on progressive leadership and good relationships between stakeholders (Weiner et al., 2020).

Kidson et al. (2020) reported on how principals’ roles expanded amidst COVID-19. They became mediators between the district policies and the schools’ operation in addition to being sensitive to the teachers’ exhaustion and anxiety. Similarly, Kelly alluded to the creation of a mentorship-based culture in her school and attributed it to her principal’s efforts. Kelly stated that her principal shared self-recorded lessons as exemplars and organized dry-run Zoom sessions to make teachers familiar with these new resources. Kelly was elated with the level of choices given to her,

…the school basically told us that we were free to explore and to use any tools that we wanted to. We were even allowed to use paper and pencil but were encouraged to find a virtual way to connect with the kids. They said that’s up to you (5:47–6:01).

This shows that the schools gave teachers the liberty to avoid potential confusion of learning new materials. Kelly also recognized that teachers from other schools had different experiences with their school administrators.

Within the mesosystem, the prominent theme was the emergence of a sense of support for each other. Sarah expressed how the school endorsed daily life practices with slogans like “The 3 W’s: Wear mask, Watch distance, and Wash hands”. She was glad that the school authorities catered to the students’ situational needs. For onsite classes after reopening in Fall 2020, the schools devised multiple time schedules to accommodate different commuting modalities, bus-riders, car-drop-offs, and walkers. The schools organized the lunch-hours in open-spaces, sanitized the shared classroom supplies, and kept the windows open for ventilation. Sarah also recognized that the school learned the hard way as during the initial days of reopening the situation was chaotic.

Sarah appreciated the technical support provided by schools, such as iPads for students and wi-fi/hotspot internet connectivity options. The schools also kept the parents in the loop by providing them LMS (e.g., Canvas) accounts so they could access the instructional materials to track the students’ progress, sent weekly newsletters, and organized flexible teachers’ office hours. Sarah acknowledged the efforts that the teachers put in to bringing a new perspective to education as their zeal to ensure quality learning strengthened the parents’ trust in the teachers.

Exosystem

Exosystem captures how a stakeholder's emotions are guided by their controllability and exercising of agency in relation to the environment (Cross and Hong, 2012). For instance, if a student fails to contribute to learning due to a sudden family emergency, the teacher will understand the gravity of situation and be sympathetic rather than being angry.

Kelly stated how initially she struggled to teach phonics as the parents were themselves were unfamiliar with those. Rather than reacting, Kelly decided to organize one-on-one FaceTime sessions with parents to guide them on how to work with their kids. Similarly, when Sarah realized that her son was learning wrong mathematical procedure due to hindsight of the teacher, rather than complaining, she shared that concern with the teacher to ensure that the teacher is aware of the issue. This shows that stakeholders kept an empathetic attitude towards each other and worked as collaborators, rather than pointing the errs in each other.

Macrosystem

Bronfenbrenner’s macrosystem includes the structural relationships between different agencies. Kelly’s statements clarified that the educational leaders dealt with this situation with ingenuity. School officials realized a need to make changes in their existing practices if they were expecting the same from the teachers. Hence, some districts altered the plans for teachers’ annual evaluation. This not only lightened the teachers’ burden but also exemplified how everyone contributed to deal with these unpredictable circumstances.

Similar structural changes were present also in the larger setting. Leah, the teacher-educator, stated that the higher education agencies were aware that teachers might struggle as they were asked to employ a new instructional mode,

I think their (teachers’) biggest thing is, how do I take something that I’ve done year after year that is hands-on and change it to something where they (students’) cannot touch or share. How do I make it interactive when they have to be six feet apart? (23:08–23:24)

Leah asserted that the state- and national-level teachers’ associations organized online workshops comparable to PD programs available only to members. She also shared that the upcoming conferences includes strands, like “How to Teach Effectively in e-learning Environments” to ensure that teachers share their teaching experiences and form effective communities of practice.

As captured in the message of the metaphor of “folding eggs to get an omelet”, the stakeholders mobilized available resources and innovated together to produce meaningful learning opportunities despite the lack of clear directions.

Folding Eggs to Get Scrambled Eggs

… because everyone is left to their own standards and regulations. People don’t really know what those mean. And when it comes down to a single school, every school level is different. So, some schools have been providing really good support, [while] other schools are saying, everything is so fast-paced and they can’t keep up. And so, students are struggling, and of course, the teachers are impacted. (26:45–27:09)

Leah discussed the structural differences among and within school systems. Every district was instructed to develop its own policies, hence, operationalizing the national plans fell primarily to state education departments. We realized that some aspects of this new instructional system fell short of expected results (or eggs became scrambled).

As mentioned earlier, all the interviewees initially experienced shock towards a transition to virtual instruction, but what stood out was the increased stress in the parents’ personal lives. The parents resented that their children’s daily routines were disturbed. Sarah expressed concern for a lack of routine during online schooling, which interrupted her own work-life (Dong et al., 2020).

Sarah expressed concerns that online schooling does not allow students to have a feeling of belongingness within the learning spaces, which further impacts motivation to learn. Similar concerns are expressed by Fournier et al. (2020) that a constant interaction is essential to ensure a positive academic environment. Being an educator herself, Sarah appreciated the value of education and understood the severity of situation on medical grounds but seemed worried about the long-term consequences of prolonged school closure and home confinement on children’s physical and mental health (Anderton et al., 2021). She asserted that parents expect schools to be spaces where children can form develop social skills, which is impossible to attain during virtual schooling.

Prime et al. (2020) asserted that links between parents’ well-being and children’s adjustment “… operate within a mutually reinforcing system, whereby stress and disruptiveness in one domain begets the same in another” (p. 632). Sarah’s concerns underscore the interactive relations among the sub-systems in Bronfenbrenner’s framework as her concerns are positioned at individual sub-system but are shaped by the micro-system in which her son is functioning.

What is Not Working for the Learners?

The World Bank (2020) reported that “more than two-thirds of parents of students who receive at least some online instructions are concerned about their children falling behind in school”. Sarah expressed similar experience where her son was learning wrong mathematical procedures. Being a mathematics educator herself, she recognized the error, but was worried “what if parents are not paying close attention, or a parent who is, like, not familiar with math … the kids would be struggling. But I don’t blame the teachers for this” (44:10–44:19). She asserted strongly that online learning is not a panacea and cannot be considered a permanent mode of instruction.

Kelly also shared that some of her students who lacked parental support for various reasons. Nadine Gracia (2020) reported how some groups are more severely affected by COVID-19 than others; nevertheless, all schools have been transitioned into the online-mode as precautionary measures. The data pointed to some implicit tension in the way learning conditions are generated, particularly because family situations and resources are very differently distributed such that one idea of delivering instruction cannot be generalized to everyone.

What is Not Working for the Teachers?

Schools have become the sites of political battles during the COVID-19 and teachers faced the consequences of what was happening at higher levels. As Kelly mentioned,

… it has been very interesting, not knowing what kind of background the kids are coming from, meaning how their parents feel about COVID and how we deal with it. You know, it’s funny how COVID has kind of become political in some respects. (26:09–26:23)

Kelly’s statement exemplified that the schools became an arena where in the middle of a global pandemic the question of what children should be taught was at the intersection of education and politics. Kelly acknowledged family choices but took self-initiative to teach her students about the benefits of hygiene and cleanliness. It is evident that in addition to extra pedagogical efforts the teachers struggled with treating their workspace as a battleground for political conflicts.

Leah pointed some critical ideas about the existing inequities in education by stating, “COVID has really been showing us the disparity of education, whether you’re from the high or low socio-economic neighborhoods” (37:08–37:23). This is crucial to assess if these arrangements of online instruction have led to some populations being excluded, particularly students due to differences in access to and sophistication in technology. Research by Graham and Sahlberg (2020) reported that teachers with little digital pedagogical expertise delivered online instructions but were incapable of addressing learners’ needs. Also, while teachers might try their best, there are obstacles to providing the same amount of attention and interaction via remote learning as they would in a face-to-face class. We learned from Sarah and Kelly that schools have taken some initiatives to assist learners with special needs by organizing individualized sessions in accordance with proper mandates. But our data does not allow us to delve deeper into such discussions.

Although the participants had highlighted the positive aspect of coming together to face the challenges, they also voiced their anxieties and struggles due to the lack of clear directions. Directions by the authorities that could not be translated into action as encapsulated in the phrase “fold the eggs” led to chaos. All they could do was “fold the eggs and get scrambled eggs”.

Discussion

This study assessed the complexities of individual stakeholder experiences during COVID-19. We unpacked the emotions and struggles of stakeholders using Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems framework.

We acknowledge that students are the key-figure in this whole process, therefore, through the voices of parents, teacher, and teacher educator we filtered what worked and what did not work for the learners.

All interviewees appreciated the support of other stakeholders, nevertheless, they identified certain aspects that would be helpful in moving forward. Sarah, the parent, understood the uncertainty of the situation which necessitates a sudden change of plans, but she also wished to have a more structured plan for her children’s schooling. She voiced the challenges in balancing their own professional lives with the increased pressure to manage their children’s instruction. Kelly, the teacher, was appreciative of everything her fellow teachers and the principal have done for her. One thing that she suggested is to organize tech-support for the teachers in each school, which might save a lot of instructional planning time. Leah, the teacher educator, highlighted that there is no one-size-fits all solution to such educational emergencies. She expressed the need to cater to students from diverse backgrounds and being cognizant of the socio-economic pressures that directly impact equity in terms of access and quality of education.

As we move forward toward this “new normal” in the wake of the pandemic, Shah and Shaker, (2020) observation may provide a useful perspective, “when it comes to schools as places of work, places of care, and places of learning—because they are simultaneously all three—'normal’ is not a standard to which we should aspire” (p. 36). This pandemic will no doubt further deepen the “education debt” in the United States (Ladson-Billings, 2006), hence, mitigating these amplified educational inequities will require a concerted effort by school officials, educators, and policymakers alike.

Based on our results, we recommend the inclusion of the virtual psychologists’ services, for personal and academic matters, to support the mental health or learning-related issues for the students. Additionally, these counselors can assist the stakeholders in feeling prepared with some strategies and ways to maintain their own, as well as the wellbeing of their children. Higher educational authorities must create platforms for the teachers to interact and actively engage in sharing educational resources to ensure a productive collaborative environment.

Policymakers must prioritize educational quality for all and allocate resources to promote educational equity. This will require a re-thinking of school-financing which currently relies largely on property taxes leading to huge disparities in spending based on the distribution of wealth in localities (Moser and Rubenstein, 2002). Recognizing that school-finance equity requires long-term advocacy, cities are beginning to consider innovative funding options in the short-term, such as asking billionaires to donate to public education (Tucker, 2021).

Finally, this study offers a rich source of insight into challenges faced by those who are at the forefront of the educational crisis. The students are at the pivot of the educational system, hence, a similar study to capture their voices directly would be informative for the field. This line of inquiry can be strengthened by including more voices beyond those captured in this paper (e.g., parents with full-time jobs). Also, we have focused only on one aspect of Bronfenbrenner’s framework (emotions), in future this work can be conducted to examine how stakeholders’ goals/ambitions or identity was impacted in similar situations. We argue that it is imperative to get a range of perspectives, including one person’s changing perspectives at different points in time, for the in-depth insight and rich description.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Indiana University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

PB: Conceptualization; Methodology; Software; Writing—Original Draft; Data Curation; Formal analysis; Project administration AS: Conceptualization; Writing—Review and Editing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anderton, R. S., Vitali, J., Blackmore, C., and Bakeberg, M. C. (2021). Flexible Teaching and Learning Modalities in Undergraduate Science amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Edu. 5, 609703. doi:10.3389/feduc.2020.609703

Bharaj, P. K. (2019). Does Collaboration in Teaching Situations Help in Enhancing Teacher's Job-Satisfaction?. Emerging Voices in Education 1, (1), 4–17.

Bacher-Hicks, A., Goodman, J., and Mulhern, C. (2021). Inequality in Household Adaptation to Schooling Shocks: COVID-Induced Online Learning Engagement in Real Time. J. Public Econ. 193, 104345. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104345

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1976). The Experimental Ecology of Education. Educ. Res. 5 (9), 5–15. doi:10.2307/1174755

Brown, S. M., Doom, J. R., Lechuga-Peña, S., Watamura, S. E., and Koppels, T. (2020). Stress and Parenting during the Global COVID-19 Pandemic. Child. Abuse Negl. 110, 104699. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699

Cachón-Zagalaz, J., Sánchez-Zafra, M., Sanabrias-Moreno, D., González-Valero, G., Lara-Sánchez, A. J., and Zagalaz-Sánchez, M. L. (2020). Systematic Review of the Literature about the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Lives of School Children. Front. Psychol. 11, 569348. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.569348

Cross, D. I., and Hong, J. Y. (2012). An Ecological Examination of Teachers' Emotions in the School Context. Teach. Teach. Edu. 28 (7), 957–967. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2012.05.001

Dong, C., Cao, S., and Li, H. (2020). Young Children's Online Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic: Chinese Parents' Beliefs and Attitudes. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 118, 105440. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105440

Fournier, E., Scott, S., and Scott, D. E. (2020). Inclusive Leadership during the COVID-19 Pandemic: How to Respond within an Inclusion Framework. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 48 (1), 17–23.

Gracia, J. N. (2020). COVID-19's Disproportionate Impact on Communities of Color Spotlights the Nation's Systemic Inequities. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 26 (6), 518–521. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000001212

Graham, A., and Sahlberg, P. (2020). Schools Are Moving Online, but Not All Children Start Out Digitally Equal. Available at: https://theconversation.com/schools-are-moving-online-but-not-allchild ren-start-out-digitally-equal-134650.

Hargreaves, A. (2003). Teaching in the Knowledge Society Education in the Age of Insecurity. New York, United States: Teachers College Press.

Kidson, P., Lipscombe, K., and Tindall-Ford, S. (2020). Co-designing Educational Policy: Professional Voice and Policy Making post-COVID. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 48 (3), 15–22.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2006). From the Achievement Gap to the Education Debt: Understanding Achievement in U.S. Schools. Educ. Res. 35 (7), 3–12. doi:10.3102/0013189x035007003

Moser, M., and Rubenstein, R. (2002). The equality of Public School District Funding in the United States: A National Status Report. Public Adm. Rev. 62 (1), 63–72. doi:10.1111/1540-6210.00155

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, California, US: Sage Publications.

Peshkin, A. (1988). In Search of Subjectivity. One's Own. Educ. Res. 17 (7), 17–21. doi:10.3102/0013189X017007017

Prime, H., Wade, M., and Browne, D. T. (2020). Risk and Resilience in Family Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. Psychol. 75, 631–643. doi:10.1037/amp0000660

Saldaña, J. (2016). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Thousand Oaks, California, US: Sage Publications.

Shah, V., and Shaker, E. (2020). Leaving normal: Re-imagining Schools post-COVID and beyond. Our Schools/Our Selves, 36–39.

The World Bank (2020). The COVID-19 Pandemic: Shocks to Education and Policy Responses. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/education/publication/the-covid19-pandemic-shocks-to-education-and-policy-responses.

Tucker (2021). Calling All Billionaires: S.F. Plans to Ask Philanthropists for Huge Sums to Help Schools post-pandemic. Available at: https://www.sfchronicle.com/education/article/Calling-all-billionaires-S-F-plans-to-ask-15862836.php.

Weiner, J., Francois, C., Stone-Johnson, C., and Childs, J. (2020). Keep Safe, Keep Learning: Principals’ Role in Creating Psychological Safety and Organizational Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Edu. 5, 618483. doi:10.3389/feduc.2020.618483

Keywords: COVID-19, online learning, online teaching, virtual schooling, teachers, parents, teaching-learning

Citation: Bharaj PK and Singh A (2021) “Fold the Eggs … Fold the Eggs … ”: Experiences of Educational Stakeholders During COVID-19. Front. Educ. 6:727494. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.727494

Received: 18 June 2021; Accepted: 06 August 2021;

Published: 24 August 2021.

Edited by:

Shaljan Areepattamannil, Emirates College for Advanced Education, United Arab EmiratesCopyright © 2021 Bharaj and Singh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pavneet Kaur Bharaj, cGtiaGFyYWpAaXUuZWR1

Pavneet Kaur Bharaj

Pavneet Kaur Bharaj Anisha Singh

Anisha Singh