- Grupo de Investigación Diversidad Funcional y Derechos Humanos, Departamento de Didáctica y Organización Escolar, Universidad de Murcia (España), Murcia, Spain

This research contributes to the knowledge and understanding of some aspects of the professional practice of primary education teachers in the Region of Murcia (Spain), and its possible effect on the creation of situations of educational exclusion. For this purpose, an instrument called EPREPADI-1 (Scale of Perception of Primary Education Teachers on their Training and Professional Practice in relation to Pupils with Disabilities) has been developed. The design and structure of the instrument includes important aspects that seek to highlight teachers’ views and knowledge of educational legislation (international, national and regional), their views on nomenclatures (such as those of persons with disabilities and inclusive education), as well as their assessment of the use of language of denial in relation to pupils with lower functional performance. Furthermore, after the statistical tests carried out for the validation of the scale (Kendall’s W test and Cronbach’s Alpha), values were obtained that give the instrument excellent validity and reliability (both for the group of experts and also for the pilot group), which is why its use and application is recommended.

Introduction

When the day comes when the only thing that I will be able to say about a person with a disability is what they have achieved in their life and not what they have not been able to achieve, it will be the moment when their reality will no longer be biased (either because their legs cannot walk, their eyes cannot see or their cognitive power is not fully developed - among many other circumstances). Undoubtedly, the last decade has been marked by social and political transformations that have advanced towards safeguarding the rights of these people (García, and Ariza, 1990; Echeíta and Duk Homad, 2008; Carbonell, 2013 and Cornejo, 2016); a clear example of this has been the ratification -by Spain in 2008- of the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (ONU, 2006). In this sense, throughout history, socio-political changes have been redefining -permanently- the life of those people who are in a situation of vulnerability due to having a low functional performance; and likewise, and with regard to this lower performance, all these people have been marked -chronologically- by numerous and very different conceptualisations (retarded, disabled, handicapped, person with disability or person with functional diversity, among others). From all these constructs, it is possible to observe the assertion of a culture biased by a disability vision which -without any doubt-associates the possible aspirations of these people with their state of health (medical-rehabilitative model), approaching that historical correspondence which understands that the better the health, the better the quality of life of the person, without taking into account the position that the person himself may take before his life (fundamental aspect for the quality of the same, as explained by the World Health Organisation-WHO).

Therefore, it seems indisputable that—despite the significant progress made in the Spanish corpus juris—society continues to forge these power relations over those who have less functional performance, by imposing demands above the wishes of the person him/herself. This situation can be observed—for example—when it is considered that their life path is different because they have a lower functional performance, wanting to predict once again what is expected of them (Schalock et al., 1989). These power relationships built in the family environment, at school—or even among their friends—lead people with low functional performance to the loss or reduction of their capacity to act, so that it could be considered that these relationships are the creators—to a large extent—of the situations of disability that these people still suffer. From this perspective, rights such as, for example, the ontological freedom inherent to every human being and which Sen (2000) considers essential for an adequate quality of life -Velandia, 2016- would be subtracted. Furthermore, it is worth highlighting the vision that the philosopher Johannes Althusius (1,557–1,638) contributes to this view by stating that “the human being has the status of a person insofar as he enjoys rights (…)” (quoted by Molina (2017) p. 126). Under this understanding, a scenario is drawn where those who have a low functional performance are relegated to the shadow of others who decide for them (either the State -at the legislative level- or their legal guardians).

Parallel to this situation, society’s attitude and perception of such people is linked to the concept of quality of life, as (Schalock and Verdugo, 2002) attest in their multimodal approach in which they cite eight dimensions of quality of life (emotional well-being, interpersonal relationships, material well-being, personal development, physical well-being, self-determination, social inclusion and rights). These categories show that in order for people to evolve in the aforementioned dimensions, they must be offered fundamental freedoms which, undeniably, are associated with the capacity to act and, therefore, the attitude and perception of the person is a determining factor for their personal, social and physical development, as well as for maintaining satisfactory interpersonal relationships, all of this with a view to inclusion and the full fulfilment of their rights. From this perspective, it is worth considering the relationship of this construct with the school context, because although the quality of life of an adult can be measured and verified through approaches such as the one presented by Schalock and Verdugo (2002) with numerous indicators (multidimensional scales focused on satisfaction, ethnographic approaches, discrepancy analysis, direct behavioural measures, social indicators, and self-assessment of the quality of life -Schalock, Verdugo et al., 2013, p.448), a child’s quality of life is contingent on the power relations that adults exercise over him or her, and he or she would be subjugated by adults to the extent that his or her rights are not fulfilled. This is what happens - on numerous occasions - with children with low functional performance; for example, when they are transferred to special education centres with the lame (and unlawful) excuse that general education centres cannot offer them a decent educational response (either due to a shortage of resources, insufficient facilities, lack of teacher training, lack of redefinition of professional practices, etc.). These statements are widely denounced in the “Report of the investigation related to Spain under article 6 of the Optional Protocol carried out by the UN Committee (2017)”, in which it is denounced that in Spain education -protected by article 24 of the CRPD-has an exclusionary and segregationist character, harming all students (regardless of their degree of functional performance). And this extreme has also been denounced by Illán and Molina (2003) when they state that Spanish educational legislation continues to be strongly committed to an outdated rehabilitative referent based on this medical model of disability.

From all of this, it is possible to glimpse a social group that is marginalised both in society (in general) with less social participation in political, economic and community life, and—more specifically—in education, maintaining ordinary and special schools, differentiated classrooms, different learning with little significance for their development in the labour market, etc. (Díaz, 2018; Monsalve, 2021). In this sense, it is essential to promote the transformation of the attitudes and perceptions that these students have socially; but it is also highly necessary to modify the teachers’ vision of this fact, given that they are the first socialising agents in children’s lives (Escudero, 2018). Teachers have been entrusted with the sweet mission of creating meaningful experiences for their students; that is why a positive attitude can lead to motivation and personal growth of students. Of course, it would be very different to maintain a submissive attitude that reaffirms inequalities due to functional diversity, which could—in any case—seriously affect the quality of life we are referring to. Therefore, the perception that teachers have of their students ends up being essential for their personal development (their training as human beings), and also for the position they adopt in their present and future lives (Molina, 2017; Álvarez, Díaz and Molina, 2021). Under these premises, a scale has been designed to determine the perception that teachers have of people with low functional performance, considering the possible link between the specific training received (at university) and their subsequent professional performance, as well as to analyse the extent to which the use of the language of denial has negative effects on students who are in a situation of disability. Furthermore, taking into consideration the social exclusion that has accompanied such people throughout human history (mainly due to the negative attitudes that low functional performance has aroused), it seems necessary to investigate the stereotypical perceptions of society towards people living with disabilities.

In this sense, the present study highlights the value of the creation of a scale of perception of primary education teachers about their training and professional practice in relation to pupils with disabilities (an instrument validated with the acronym EPREPADI-1). It is a scale based on four clearly defined thematic blocks: personal opinion about disability, knowledge about the rights recognised for pupils with disabilities, personal opinion about the professional teaching practice, and personal opinion about the semantics used in relation to the disability construct. All these categories have been developed based on the specialised literature on this subject (Molina, Vallejo and Illán, 2016; Molina, 2017; Álvarez, Díaz, et al., 2021), and for the purpose of collecting information on aspects such as the knowledge that teachers have regarding the content of current educational legislation (on quality education), their opinion on the construct of inclusive education and disability, the use (or not) of the language of denial, as well as the relationship between their perceptions of functional diversity and its subsequent transposition in their daily professional practice (as teachers).

Theoretical Framework

This study discusses students who are discriminated against on the grounds of functional diversity; and it does so with respect to two key conditioning factors. On the one hand, it discusses the knowledge that teachers have about educational legislation and the use that they make of it in their regular professional performance; and, on the other hand, it also submits to analysis the use of the language of denial that is given -by teachers-at school. In this sense, considering the teachers’ perception as a fundamental element for the development of this scale, we have reflected -firstly- on the relevance that perception reaches in the research processes in social sciences, as well as on why and for what purpose this survey (EPREPADI-1) was designed, from which we intend to give consistency to the proper development of the research. In addition, with respect to this approach, the following lines will serve to present some brief considerations about the educational regulations governing inclusive education, describing—specifically—the articles referring to students with lower functional performance (the concept on which this perception scale is based). Subsequently, emphasis is also placed on the construct of the language of denial referred to in the last block of items of the questionnaire; and all of this, subject to the theoretical investigation of the specialised literature used for its design. There is no doubt that the construct of perception is known for its use both in the social sciences and in other disciplines (for example in sociology or anthropology, among others: Sabido, 2017; Lewkow, 2014). Under this view, polysemic readings have arisen, as the term perception continues to be understood from a single perspective and, occasionally, it has come to be used to describe social aspects or conceptual discussions that (according to specialists in the field—Molina, Corredeira and Vallejo, 2012) do not have a real link with perception, sometimes leading to results that are far removed from the purpose of the study. Following this same line of thought, Vargas (1994) defines perception as:

The cognitive process of consciousness, which consists of the recognition, interpretation and significance for the elaboration of judgements around the sensations obtained from the physical and social environment, in which other psychic processes intervene, among which are learning, memory and symbolisation (p. 48).

By virtue of these words, it can be confirmed that—during its use for scientific research—perception can (and should) come to reflect what people perceive about what they may be asked about. We cannot forget that these answers—in turn—are conditioned by what the subjects have experienced, learned and/or shared in the social environments in which they live. This shows that it is absolutely necessary for researchers to specify, specify or define both the questions to be asked (i.e., that they are adequately grounded with respect to the subject matter to be investigated), as well as -necessarily- to draw up both exclusion criteria for the sample and also a catalogue of questions from which it is possible to verify the degree of adjustment between what is designed and the reality of the sample group.

Precisely because of the importance of perception for social studies, authors such as Molina, Corredeira and Vallejo (2012) explain that social perception “is the process through which we try to know and understand others” (p. 952) and, therefore, it also serves to interpret the underlying causes of people’s actions, i.e. why they act in one way or another. Likewise, as the purpose of the research is to find out the perception that teachers hold regarding their own professional practice, the scale designed is a type of survey developed following the theoretical indications for these scientific studies in the social sciences (Castro et al., 2016). By virtue of the specialised literature, having a representative number of the population, it will be possible to infer whether teachers in the Region of Murcia give due fulfilment to the exercise of their teaching work (at a general level). And—in a more particular way—it also allows us to inquire about the knowledge they have about the educational rights of children with less functional performance (referenced in the specific regulations on this matter—which they should obviously know and fully comply with), as well as to get into their opinion about their actions in the classroom (that is, about the exercise of their duties) and also in relation to the appropriate use of inclusive semantics and the legitimisation of this among their colleagues and the pupils as a whole.

Similarly, continuing with the contextualisation of the EPREPADI-1 scale, it is unavoidable to delve into some of the transformations that—in recent decades - have been taking place with respect to the international—and also national—corpus juris in the field of education (Molina, 2017; Álvarez, Díaz and Molina, 2021; Díaz, 2018). More specifically, on the regulations by virtue of which the care of students with lower functional performance is specified (transformations in the constructs that concern them, recognition of rights and duties, approval of resources for their inclusion in regular schools, etc.). Internationally, and since the approval of the CRPD (ONU, 2006), Spanish schools have been advocating a role in defence of the rights of people with disabilities (Parreño and de Araoz Sánchez Dopico, 2011). As we know, historically, the rights of these students have not been safeguarded by educational legislation (Molina, 2017) and, under this view, schools have faithfully followed what has been—capriciously—established by legislation, turning -undeniably- the passage of students with low functional performance into a series of situations of vulnerability (built on the assumption that these students are people with disabilities and that their condition is an impediment to learning). It also entails the generation of situations of exclusion, for example from those activities carried out in the classroom in which, while for the majority of the group there is a common objective and they carry out a single task, the student with less functional performance carries out a totally different task, and which -moreover- is erroneously justified from the -misunderstood- principle of individualisation of teaching. The current reality of all these students suffers from regulations, a school and professionals who are still not able to offer an educational response adapted to their needs, and this is confirmed by the latest Report of the UN Committee -2017-, which also places special emphasis on this exclusion to which students with higher functional performance are subjected, since (through the maintenance of a parallel school, differentiated contents, learning standards, standardised assessment reports, special nomenclatures, etc.) they are only allowed -through the maintenance of a parallel school, differentiated contents, learning standards, standardised assessment reports, special nomenclatures, etc.) they are only allowed—in the best of cases—to cohabit in the same classroom under the pretence of complying with the principle of integration, but—certainly - denying them the possibility of sharing and protecting this (much-vaunted) educational inclusion every time they have to leave their classroom of reference, or when they are denied access to an ordinary education centre. Despite the approval of numerous national - and also EU—regulations, in Spain (apparently) full compliance with the right to quality education is not equally guaranteed for all students. This is probably because, regardless of the ratification of high-ranking regulations, the weight of cultural tradition (professional and administrative) is infinitely more powerful than the most impeccable of articles, especially if, together with the approval of the regulation, precautionary measures and protocols of action are not established for (obvious) future non-compliance (as happens, for example, with the job offer designed for these people Albarrán Lozano and Alonso González, 2010; Gutiérrez et al., 2020). On the other hand, when we look at some data provided by other research on the perception of teachers (Colmenero et al., 2019; Ruíz et al., 2019 -among others), we can see a biased opinion in which the administration is still given a large part of the responsibility (in this opinion), highlighting that -in general-teachers do not have sufficient capacity to act in favour of these students. This is also the case with the renowned lack of resources to respond to all pupils, with the (apparent) tyranny in the overload of tasks for teachers, with the unstoppable increase in the ratio per class, or with the insignificant number of specialist teachers (in hearing and language or therapeutic pedagogy), among others. But for some authors (Molina, 2017; Álvarez, et al., 2021), the absence or low availability of all these resources would not be as substantive as the improper use that could be made of such resources, exposing—in turn—the prevalence of issues of will over technical problems (Molina, 2017, p. 172). Therefore, a brief analysis of the regulatory situation in Spain shows a scenario in which its legislation includes a whole support structure for students with low functional performance, recognising attention to student diversity in all its preambles up to the specific articles dedicated to the education of these students (Art.º 71, 72 or 73 of the OLIEQ, for example), all of which are included in the latest educational laws passed in our country (Organic Law on Education 2/2006 -LOE-, 2006; Organic Law on Education 8/2013, 2013 for the Improvement of the Quality of Education -OLIEQ-, and the Organic Law that modifies Law 2/2006 -LOMLOE-). In this sense, the Region of Murcia is a proactive community in safeguarding the rights of all pupils, and by virtue of this it proposes various regulations to promote inclusion and foster the quality of life of these pupils. By way of example, Decree 359/2009 (which establishes and regulates the educational response to student diversity in the Autonomous Community of the Region of Murcia) and the Order of June 4, 2010 (which regulates the Plan for Attention to Diversity in public and subsidised private schools in the Region of Murcia) are examples of regulations in line with this defence of rights. These regulations arise from the express desire for teachers to have a legislative framework from which to act, protecting -also- the right to education of those who have a lower functional performance (i.e., moving away from the rehabilitative vision of legislation from the last century). The procedures to be followed by teachers have become a challenge for the Administration (with the development of regulations) and for universities (with the necessary updating of their training plans), as well as for all schools and their professionals (with a significant involvement in their ongoing training, and the consequent increase in an additional administrative burden). All of this, with the aim that their teaching practices do not become a scenario -only- full of good intentions. Undoubtedly, these laws are a result of the desire to include in schools all those issues regarding attention to diversity which, it seems (and year after year), continue to be of interest to jurists. Despite this, the modifications are so slight and empty of content (with minimal changes in nomenclature and the absence of procedures to be followed by teachers) that it could be said that inclusive education and educational quality remain a chimera. As proof of this, research such as that contained in the EPREPADI-1 scale takes on special relevance and prominence insofar as its aim is to respond to both students and teachers, insofar as it is not limited to providing—only-some (superficial) answers for students, but also attaches importance to the approach that teachers must have to what actions are necessary and how to carry them out within this new socio-educational scenario of inclusion (Palacios, 2020).

Material and Methods

Instrument (Scale EPREPADI-1)

Firstly, it should be noted that the EPREPADI-1 scale has been specifically designed and developed to find out to what extent the use of the so-called language of denial has negative effects on pupils with disabilities, and to what extent it may affect their emotional balance, as well as the possible construction of situations of social exclusion in different areas (educational, social, leisure, etc.). In the same way, it also makes it possible to describe the perception of primary education teachers in the Region of Murcia with regard to people with disabilities, analysing the possible relationships that may exist between the specific training received (initial and continuous) in the field of functional diversity and subsequent professional performance.

In this sense, the instrument developed for this research is structured according to four clearly defined thematic blocks (personal opinion on disability, knowledge of the rights recognised for students with disabilities, personal opinion on professional teaching practice, and personal opinion on the semantics used with respect to the disability construct). All these categories have been designed taking into account the specialised literature (Molina, Corredeira and Vallejo, 2012; Molina, 2017; Álvarez, Díaz and Molina, 2021) and, above all, following the international, national and -particularly- Murcia Region educational regulations. The instrument is made up of sixty-four items, twelve of which are dedicated to the socio-demographic data of the participants (educational centre, type of centre, sex, age, qualifications studied, etc.); two questions dedicated to personal opinion on disability (through which qualitative information will be obtained). It also incorporates twenty-four questions (multiple choice and Likert-type) on knowledge of the rights of people with disabilities, together with another seventeen items referring to the teacher’s own professional practice, which follow the same Likert-type scale that is maintained throughout practically the entire questionnaire (with the options totally correct, partially correct, not sure, partially correct, totally incorrect). Finally, the scale closes with seven questions aimed at finding out the teachers’ opinion of the semantics used by teachers (including themselves) in relation to students with lower functional performance.

Method and Sample

The instrument developed is a perception scale subject to validation by a group of expert judges, as well as by a pilot group of professionals representative of the sample. Specifically, it has been developed to study the relationships and associations that exist between the different variables, as well as to make comparisons between the different participants in the study (primary school teachers in the Region of Murcia in the case of the EPREPADI-1 scale). According to the specialised literature (Galicia, Balderrama Trápaga and Edel, 2017), there are different formulas to validate questionnaires, in order to verify that the instrument accurately measures what is desired. In the case of this research work (which is of a non-experimental nature, dedicated -exclusively- to the validation of the EPREPADI-1 scale), a procedure has been followed in which (following Escobar and Cuervo, 2008; Boluarte and Tamari, 2017) the measurement of the validity of the content (on the one hand) and the reliability of the questionnaire (on the other) has been carried out, with the aim of optimising its subsequent applicability.

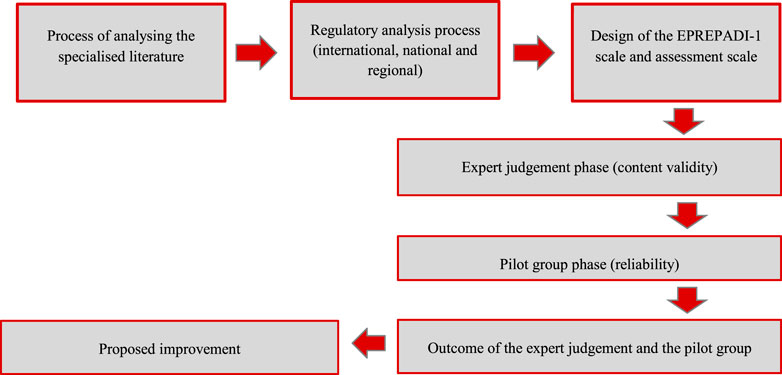

As shown in the previous image (Figure 1), and based on (Zamora et al., 2020), two phases were followed to develop the validation of the questionnaire (expert judgement, pilot group) from which the results obtained show the need to make some changes to optimise the scale. In this sense, for the development of the expert judgement phase, an ad hoc evaluation instrument was developed in which the participating judges had to provide descriptive information on their profile -as experts- (professional category, years of professional experience and current performance in management positions). For the evaluation of each of the items, four excluding criteria were defined: clarity, relevance, validity and pertinence. Thus, the experts had to evaluate each of the items of the scale according to these four criteria (previously defined) and in a range of 1–4 (1 being the lowest degree of agreement and 4 the highest degree of agreement), leaving room—also—for comments at any time. In addition, following the same scoring system, at the end of the questionnaire they were given the opportunity to make an overall assessment of the questionnaire. Once the judges’ evaluations had been analysed, and in analogy to the procedure followed by Molina, Corredeira and Vallejo (2012), the criterion used for the retention or modification of an item was the agreement of at least 75% of the judges. After applying the improvements made by the group of experts, the pilot group phase was carried out in order to complete the reliability process of the instrument.

Instrument Validity

In the process of validating an instrument, expert judgement is a technique frequently used to ascertain the degree of agreement between judges and, based on their evaluations and observations, to contribute to the objectivity of the instrument designed for the collection of information (Bruna, et al., 2019; Hernández and Pascual, 2017) before its mass application. In this sense, the inter-judge assessment takes the form of the judgement made by a group of professionals knowledgeable in the subject matter to which the instrument submitted for assessment refers, so that they can contribute their interpretations and considerations regarding the following elements of the scale: semantics, content, structure, concreteness and appearance of the items (among other conditions -Zamora, Serrano and Martínez, 2020).

For this study, and taking into account that a purposive and non-probabilistic sample has been used (Escobar and Cuervo, 2008), the selection of the judges was carried out on the basis of their professional training with respect to the subject matter contained in the EPREPADI-1 survey, their current professional performance, as well as their willingness to join the evaluation process. In this sense, the designed assessment instrument was sent for possible participation to fifteen experts, including teachers, school principals, legal specialists and doctors of education. All of them were given the opportunity to respond within a period of 15 days, which was subsequently extended (for another 15 days) to allow for a greater degree of participation. The process ended after the collaboration of five experts, which meant a differential loss of 66.7% of the participants (n = 10). The final participants included a university lecturer (experienced in special education), three teachers (head teachers) and a university lecturer (specialist in civil law), all of them with more than 20 years of teaching experience. As indicated above, the judges had to make their estimation expressed in terms of the degree of agreement—or disagreement—with regard to the pre-established criteria for the evaluation. In this sense, the definition of each of the exclusion criteria was as follows:

• Clarity (CL): this criterion refers to whether the contribution is considered “clear”, in the sense of having comprehensive, semantically correct and unambiguous wording.

• Relevance (RV): this criterion refers to whether the information input provided by the item under analysis is notable and/or distinctive for the purpose of the study (i.e. the item is—to a greater or lesser extent—relevant).

• Coherence (CH): this criterion refers to the adequacy of each item with the purpose of the research; we would then talk about whether the item is coherent with the nature or purpose of the study.

• Relevance (PT): this criterion refers to the degree to which each item, as it is written, is relevant to the research, in the sense of whether it serves (to a greater or lesser extent) to achieve the proposed objective.

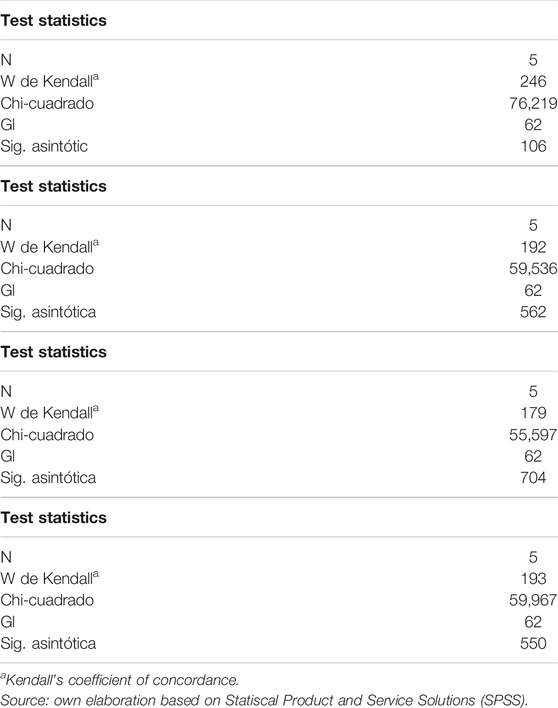

On the other hand, it is absolutely relevant to underline that the judges always responded individually and without any previous contact between them. Furthermore, Statiscal Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) version 24.0 was used for the reliability analysis. With regard to the tests carried out, descriptive statistics were calculated for each of the criteria evaluated (CL, RV, CH and PT), taking into account for the analysis -also- the opinions that the judges referred to regarding the title, instructions and general assessment of the design of the questionnaire. In turn, to test the hypothesis and the degree of inter-judge agreement, Kendall’s (non-parametric) W test was used.

Instrument Reliability

The analysis processes carried out to observe the reliability of the instruments used to collect information aim to ascertain the precision with which these instruments—in a real and consistent manner—measure what is desired. Generally, in all questionnaire validity processes, a distinction should be made between content validity and reliability, since the presence of one of these two values does not imply the obligatory presence of the other; in other words, a questionnaire may have a high reliability and yet not be able to measure what is desired. Following these criteria, for a survey to be considered suitable for the research process, it is absolutely necessary that it is both valid and that it has a high reliability index. Specifically, in the case of the EPREPADI-1 scale, the treatment of these data has been carried out in order to find out whether it is reliable in its prediction of the perception that primary school teachers have of students with lower functional performance (Santisteban, 2009; Barbero, 2010). As we know, if in reliability analyses the measurement values are arranged between the real value and the error range, an instrument will behave with greater reliability to the extent that its error value is minimised (Argibay, 2006; Martínez, et al., 2014). On this basis, the procedure to determine the reliability of the EPREPADI-1 survey has followed—as indicated in Figure 1 two-phase process (expert judgement and pilot group); in both phases the Cronbach’s alpha test was applied. This non-parametric test was carried out with the aim of assessing the internal consistency of the items (64) subjected to assessment, both by the experts and by the pilot group; that is, through this test it could be affirmed (or not) whether the construct is valid, provided that the items that make up the scale show a satisfactory correlation (which would indicate that the measures would be representative for that construct).

Results

As a direct consequence of the validity process of the EPREPADI-1 survey, the descriptive statistics of the ratings provided by each of the experts (mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values and quartiles -first, second and third-) have been analysed according to the four criteria used for the judges’ evaluation (clarity, relevance, coherence and pertinence). These calculations were also used for the evaluation of the title, instructions and design of the questionnaire. Similarly, in order to ascertain the robustness of the opinions provided by the experts, Kendall’s (non-parametric) W test was carried out. This test allows us to ascertain the hypothesis of agreement between the judges and, therefore, to observe whether there is significant agreement between the assessments made by the experts (Siegel and Castellan, 1995), knowing that a value of 1 means total agreement and a value of 0 means total disagreement (Escobar and Cuervo, 2008).

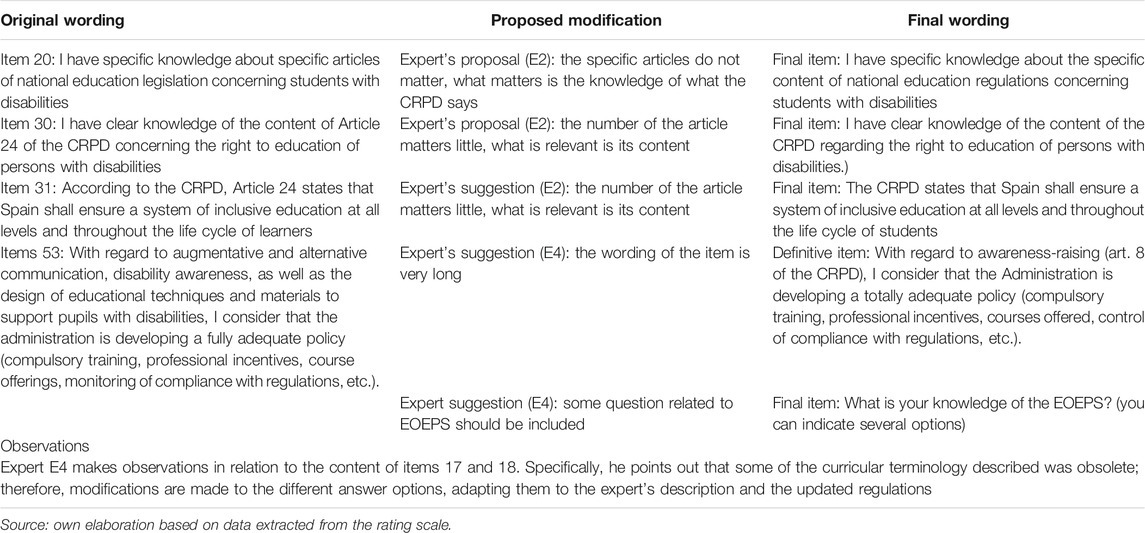

By virtue of the analysis of the descriptive statistics, we observed those items whose values were close to the minimum value (values 1 and 2 being considered as a low level of satisfaction), and also those whose values were close to the maximum value (values 3 and 4 being considered as a high level of satisfaction). Thus, it can be confirmed that those items whose codes have been evaluated with a minimum value (between 1 and 2) and which also have a high standard deviation, maintain a greater variability among the experts’ evaluations, and this is reflected—by way of example—in the following graph:

Graph 1 Mean of the Clarity Criterion.

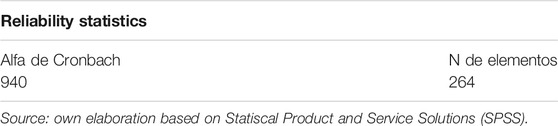

As can be seen from the data shown in the previous graph (Graph 1), the variability of the mean for the clarity criterion is greater in items C15, C16, C17, C18, C45, C50, C52 and C53; however, with the exception of items C15 and C17 (which have been rated by 40% of the experts below the levels of agreement), in no case can the variability of the standard deviation be considered significant, with all the experts showing agreement on this point. Similarly, descriptive statistical calculations have been carried out for the other criteria assessed by the judges—relevance, pertinence and coherence—without obtaining a significant standard deviation for any of the cases. This means that -for all these criteria-there has been a high level of satisfaction in the assessment of the items; the same has occurred with the rest of the items assessed (title, instructions and scale design), which have been evaluated by more than 75% of the judges with the maximum value of agreement (4).In turn, the ordinal scale of Kendall’s W coefficient of concordance was applied to determine the degree of concordance between the judges (k = 5); it should be noted that -for its analysis-the ranges indicated ut supra (when describing the test) were assigned, obtaining as a result for each of the criteria always values above the level of significance. This implies a statistically significant agreement between the experts or, in other words, that there is no significant difference between their answers.Specifically, the data resulting from the test indicate that, although for the clarity criterion the level of asymptotic significance was 0.106 (which would determine that there may be ambiguity in the level of agreement between the items assessed for this criterion), this fact is duly explained by the lower score obtained for the two items indicated in the descriptive statistics. For their part, the rest of the criteria assessed by the judges have a moderate-high level of agreement, as the data obtained were 0.565 for the relevance criterion, 0.550 for the coherence criterion and 0.704 for the pertinence criterion (Table 1). In this regard, it is absolutely relevant to point out that the difference in agreement between the judges is also necessary to confirm that there is no agreed criterion for the classification of the items (Siegel and Castellan, 1995). Furthermore, as Escobar and Cuervo (2008) point out, it is very unlikely that the results will show extreme values (0–1), with a greater dispersion being the norm.Likewise, in order to ascertain the degree to which the items of the EPREPADI-1 survey covary with each other (i.e. with the aim of measuring the internal consistency of the survey—its reliability), the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient test was carried out, The interpretation of the data obtained followed the criterion provided by George and Mallery (2003), according to which -as a guideline-an alpha coefficient below 0.5 would be unacceptable, and considered to be of good quality as of 0.7 (with values between 0.51 and 0.69 being considered questionable, depending on different variables). In the case of our scale, the result obtained would correspond to an excellent rating (α = 0.940) (Table 2); this means that the level of internal consistency is excellent and that, therefore, the items that make up the scale have a good correlation. Therefore, according to Celina and Campo-Arias (2005), it can be concluded that this scale is a valid construct (p. 574).Evidently, within the process of validation and reliability of a questionnaire, biases can also appear that are marked by the subjective evaluations made by the experts. Thus, in addition to including the possibility for the judges to make their observations for each of the items and implicitly suggesting their redefinition if they so wish, in order to reduce this type of bias we have also considered the calculation and analysis of the results of a pilot test in which the participants (24 teachers from the Region of Murcia) were randomly selected from the different primary education centres in the region (to whom an e-mail was sent inviting them to participate in this research as primary education teachers). In this sense, taking as a reference the reliability data obtained with the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient test for the scale (by the experts’ judgement), we proceeded to develop this same test with the data collected from the pilot group, thus providing - in this way—greater reliability to the instrument. As a consequence of this calculation, the excellent rating of the instrument (α = 0.863) was also reinforced, following the criteria of George and Mallery, 2003) (Table 3).Thus, after analysing the statistical tests carried out, the internal consistency of the questionnaire was confirmed, as well as the validity and reliability of the scale. In this sense, the proposal for the modification of some items by the experts is detailed below:After the redefinition of the items mentioned in the table (Table 4), based on the data studied from the pilot group as well as the confirmation -after the analysis of the expert judgement data-of the validity and reliability of the EPREPADI-1 scale, the reliability of the instrument is ratified with a highly satisfactory correlation and representative measures for the construct. In addition, and with the obvious reservations about generalisability that any pilot group entails (due to the limited representativeness for generalisation), the data extracted from the pilot group confirm the relevance of the problem under study, indicating that more than 60% of the respondents are unaware of the content of Article 24 of the CRPD (on the right to education); it is also very striking that 46% of the teachers surveyed acknowledge that they do not have (or are not sure they have) specific knowledge about educational regulations on the subject of attention to diversity. But it is equally worrying to know that more than 75% of the participants consider that the educational expectations that teachers have for their students with disabilities are not the same as those they have for the rest of their students. In short, the analysis shows that the content of the scale is fully representative for the research to be carried out. Similarly, it is important to highlight that -from a methodological point of view-this initial (validation) phase will continue with the subsequent implementation of the EPREPADI-1 survey to a representative sample of primary school teachers in the Region of Murcia (Zamora et al., 2020).

Discussion

It is obvious that administrative inefficiency and—consequently—the violation of people’s rights, are linked to such revealing data as those recently denounced by the UN (2020), in which we are warned that a third of the world’s population lives on one dollar a day, that every 5 seconds a child dies of malnutrition or that 263 million children between the ages of 6 and 16 are not in school. These data represent unquestionable challenges—at the global level—with which nations have to contend, but those who truly face the desert of administrative solitude are those who are directly affected, those who are denied the exercise of a recognised right, since the access to justice offered to them is an insurmountable barrier. On the basis of all these considerations (which have been used for the development of the scale submitted for validation), education and—therefore—the school are postulated as protagonists in the vital development of any student regardless of the high—or low—functional performance of each one. In this sense, the results expected from the massive application of the validated scale will prelude the beginning of a debate from which to review the situation of vulnerability and exclusion that students with low functional performance experience at school, as well as the participation—in this—of the Administration and teachers in the improvement of such extremes. In the same way, through this application it will be possible to represent the need to transform the school in order to provide -and not only promise-an education focused on the real needs of its students, their wishes and their own learning process in harmony with their personal growth.

Directly related to this fact, it is worth mentioning the Sustainable Development Goals, specifically the fourth goal of quality education, which states the need for all nations to achieve inclusive quality education for all. In this sense, for education to become inclusive, there must be a transformation in the understanding that still exists towards students who are discriminated against because of their functional performance, since it is not only a question of children with low functional performance sharing the classroom or common school spaces with the rest of the student body, Rather, it is absolutely necessary to carry out a paradigm shift in which the core training of teachers considers that it is just as important to transform their methodologies so that their students with lower functional performance can participate and learn, as it is for the rest of the students that they meet and share with these students who are in a situation of disability. In this way, it will be possible to eliminate some stigmas and social barriers that still hinder the fulfilment of numerous rights such as the right to education that all children have, and which—sadly—is affected by the lack of training of education professionals, the lack of full compliance with the regulations on the part of both educational centres and the educational administration itself, and -of course-by the importance of the historical trajectory that is still with us and that reveals a lack of understanding in the way of seeing low functional performance, since there is a vast majority of people (of course, also of education professionals) who do not distinguish between the need for an adaptation or support and their belief that these people will not be able to achieve or acquire the learning or skills that are proposed to them. In this perspective, educational regulations point out the need to transform this vision and also the professional practices clinging to the past, and likewise the specialised literature (Molina, 2017; Álvarez, et. Al. 2021) mentions the transformation from that medical-rehabilitative paradigm that still interprets that people with lower functional performance have to be separated or even disregarded when it is not well known how to adapt the contexts for them, and calls for the evolution towards the paradigm of human rights, through which we are all equal before the full fulfilment of rights, emphasising the existence of diversity as the means to promote opportunities in all areas and, specifically, in the equitable development of learning. In this sense, the EPREPADI-1 scale will make it possible to know to what extent the training received by teachers, together with their social perceptions, can generate discriminatory situations at school for all pupils, understanding that the exclusion of these pupils implies indirect discrimination for pupils who are not in a situation of disability.

Conclusions

According to the results obtained after the validation of the EPREPADI-1 scale, the following conclusions can be highlighted:

1. Through the execution of the process of expert judgement, it has been possible to carry out the evaluation and assessment of the content which, together with the study analysis criteria (clarity, relevance, coherence and pertinence), the validation of the scale has been carried out, obtaining correct indices for the mass application of the scale to teachers.

2. It is also necessary to explain the relevance of the selection of the profile of the experts, the design of the instrument that has served to indicate their contributions (assessments and observations), as well as the development of the data analysis tests carried out, such as Kendall’s W and Cronbach’s Alpha, both of which are decisive for the validation of the scale.

3. The implementation of the pilot test, whose selection of participating teachers has also helped the validation process of the scale, by obtaining excellent indices in the results of the Cronbrach’s Alpha test. In addition, this pilot test has allowed us to observe some findings that certainly confirm that the scale really measures what is desired for the research.

In this sense, from the tests carried out, this study shows results that indicate that the psychometric indices of the EPREPADI-1 scale are highly satisfactory in relation to the criteria already defined (clarity, relevance, coherence and pertinence). Moreover, once the concordance between the judges in their assessment for each of the items has been confirmed, it is confirmed that the survey presents a high validity and reliability for mass application. Undoubtedly, the results obtained with the application of the survey will make it possible to describe the main axes of transformation of that reality which, despite being in continuous evolution over the last 30 years, in Spanish society continues to show that marked instructive, memoristic, stereotyped and prejudiced character for those with a lower functional performance, as well as an excessive eagerness to preserve an (inherited) system that generates homogeneous beings and curtails talent, creativity and uniqueness (Molina, 2017; Etxeberria Mauleon, 2018).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Comité de ética de la Universidad de Murcia. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, YM and JS; methodology, YM; formal analysis, YM investigation, YM and JS; resources, JS; data curation, YM and JS; writing—original draft preparation, YM; writing—review and editing, YM and JS; visualization, YM and JS; supervision, JS; project administration, JS; funding acquisition, JS.

Funding

This research is funded by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities through the Help of the University Teacher Training Program with reference: FPU17/00406.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Albarrán-Lozano, I., and Alonso-González, P. (2010). Participación en el mercado laboral español de las personas con discapacidad y en situación de dependencia. Papeles de población 16 (64), 218–256.

Argibay, J. C. (2006). Técnicas psicométricas. Cuestiones de validez y confiabilidad. Subjetividad y procesos cognitivos 8, 15–33.

Barbero, M. I. (2010). Psicometría (Teoría, Formulario Y Problemas Resueltos). Madrid: Sanz y Torres.

Carbonell, J. (2013). La aventura de innovar: el cambio en la escuela. Caracas: La aventura de innovar, 1–124.

Castro, L., Antonio Casas, J., Sánchez, S., Vallejos, V., and Zúñiga, D. (2016). Percepción de la calidad de vida en personas con discapacidad y su relación con la educación. Estud. Pedagóg. 42 (2), 39–49. doi:10.4067/s0718-07052016000200003

Colmenero, M.-J., Pegalajar, M.-C., and Pantoja, A. (2019). Teachers' perception of inclusive teaching practices for students with severe permanent disabilities/Percepción del profesorado sobre prácticas docentes inclusivas en alumnado con discapacidades graves y permanentes. Cultura y Educación 31 (3), 542–575. doi:10.1080/11356405.2019.1630952

Echeíta, G., and Duk Homad, C. (2008). Inclusión educativa. REICE. Revista electrónica Iberoamericana sobre calidad, eficacia y cambio en educación 6 (2), 1–8.

Escudero, M. Z. (2018). Subjetividades e identidades en deconstrucción: la escuela como agente socializador. Antioquía (Bogotá).

Etxeberria Mauleon, X. (2018). Ética de la inclusión y personas con discapacidad intelectual. Redis 6 (1), 281–290. doi:10.5569/2340-5104.06.01.14

Galicia Alarcón, L. A., Balderrama Trápaga, J. A., and Edel Navarro, R. (2017). Content Validity by Experts Judgment: Proposal for a Virtual Tool. Ap 9 (2), 42–53. doi:10.32870/ap.v9n2.993

García, J. E., and Ariza, R. P. (1990). Cambio escolar y desarrollo profesional: un enfoque basado en la investigación en la escuela. Investigación en la Escuela (11), 25–37.

Gutiérrez, B., González, A., and Otero, A. (2020). Situación actual del empleo de las personas con discapacidad en España. CIVINEDU 2020, 669.

Illán, N., and Molina, J. (2003). La Atención a la diversidad: perspectiva histórica y tendencias actuales. Murcia: Universidad de Murcia (España).

Lewkow, L. (2014). Aspectos sociológicos del concepto de percepción en la teoría de sistemas sociales. Revista Mad. Revista Del. Magister en Análisis Sistémico Aplicado A La Sociedad 31, 29–45. doi:10.5354/0718-0527.2014.32957

Ley 8/2013 (2013). de 9 de diciembre, para la Mejora de la Calidad Educativa. Boletín Oficial Del. Estado 295, 3–64.

Molina, J. (2017). La discapacidad empieza en tú mirada.Las situaciones de discriminación por motivo de diversidad funcional: escenario jurídico, social y educativo. Madrid: Delta Publicaciones.

Monsalve, C. (2021). Diferencias Individuales, Equidad, Inclusión Educativa Y Ordenamiento Legislativo. Transformación 17 (1), 72–83. Recuperado a partir de. https://revistas.reduc.edu.cu/index.php/transformacion/article/view/e3476

ONU (2006). Convención sobre los Derechos de las Personas con Discapacidad y Protocolo Facultativo. Nueva York: ONU.

ONU (2013). Estudio temático sobre el derecho de las personas con discapacidad a la educación. España: Informe anual del Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas.

Palacios, A. (2020). ¿Un nuevo modelo de derechos humanos de la discapacidad? Algunas reflexiones–ligeras brisas-frente al necesario impulso de una nueva ola del modelo social. Revista Latinoamericana en Discapacidad, Sociedad y Derechos Humanos 4 (2).

Parreño, M. J. A., and de Araoz Sánchez-Dopico, I. (2011). El impacto de la Convención Internacional sobre los Derechos de las Personas con Discapacidad en la legislación educativa española. España: CERMI.

Ruíz, M. J. C., Palomino, M. C. P., and Vallejo, A. P. (2019). Percepción del profesorado sobre prácticas docentes inclusivas en alumnado con discapacidades graves y permanentes. Cultura y Educación: Cult. Educ. 31 (3), 557–575.

Sabido, O. (2017). Georg Simmel y los sentidos: una sociología relacional de la percepción. Revista mexicana de sociología 79 (2), 373–400.

Schalock, R. L., Keith, K. D., Hoffman, K., and Karan, O. C. (1989). Quality of Life: Its Measurement and Use. Ment. Retard. 27 (1), 25–31. doi:10.1007/BF02578420

Schalock, R. L., and Verdugo, M. A. (2002). Handbook on Quality of Life for Human Service Practitioners. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation.

Verdugo, M. A., Schalock, R. L., Arias, B., Gómez, L. E., and Jordán de Urríes, B. (2013). Calidad de vida. MA Verdugo & RL Schalock (Coords.). Discapacidad e inclusión Man. para la docencia, 443–461.

Keywords: perception, functional performance, teachers, legislation, education

Citation: Santa María YD and Saorín JM (2021) Primary School Teachers’ Perception of Low Functioning Students: Validation of the EPREPADI-1 Scale. Front. Educ. 6:724804. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.724804

Received: 14 June 2021; Accepted: 27 September 2021;

Published: 01 December 2021.

Edited by:

Nelly Lagos San Martín, University of the Bío Bío, ChileReviewed by:

Inés Lozano-Cabezas, University of Alicante, SpainMarcos Jesus Iglesias-Martinez, University of Alicante, Spain

Copyright © 2021 Santa María and Saorín. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jesús Molina Saorín, amVzdXNtb2xAdW0uZXM=

Yonatan Díaz Santa María

Yonatan Díaz Santa María Jesús Molina Saorín

Jesús Molina Saorín