94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 23 August 2021

Sec. Higher Education

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.720565

This article is part of the Research TopicHigher Education Dropout After COVID-19: New Strategies to Optimize SuccessView all 15 articles

The COVID-19 pandemic has had an extensive impact on the global higher education sector. In a written survey, staff and students at the Lucerne School of Social Work reported how they had coped with the challenges to their teaching or respective learning situation. The initial survey was conducted during the lockdown in spring 2020, and the follow-up survey was performed in the period of relaxed sanitary measures in summer 2020. During the first wave of the survey, 51 employees and 225 students participated. In the follow-up survey, 28 employees and 117 students partook. Findings indicate that the increased workload created by the transition was stressful for both staff and students but overall was handled well. Staff and students who felt supported by the university management experienced less psychological distress. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, there has been an effort to develop hybrid forms of teaching. Because the social work curriculum contains building blocks that are difficult to implement in the form of distance learning, the transition posed challenges for both staff and students. During times of transition, university management must carefully assess the support needs of staff and students and take appropriate action.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had an extensive impact on the global higher education sector. In light of rising concerns about the current pandemic, a growing number of universities across the world either postponed or cancelled all campus events such as workshops, conferences, sports (both intra and inter university), and other activities. As of the 26th April 2020 UNESCO reported there have been 1,563,992,622 affected learners worldwide from pre-primary to tertiary education. This equates to 89.3% of all enrolled learners, globally and includes 183 country-wide closures (UNESCO, 2020). Obviously, the Swiss education system was and still is also affected by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to a sharp rise in infections, the Swiss Federal Council declared the “extraordinary situation” as early as March 16, 2020, passing an ordinance that placed massive restrictions on public life. Primary schools as well as universities had to close immediately. While elementary schools had already reopened by May 11, 2020, Swiss universities were able to resume teaching on June 8, 2020 under the condition that they apply strict public health measures. Due to the second and third COVID-19 waves, classes at the universities were again taught in the form of distance learning, in the fall. It is assumed that classes will remain restricted for an indefinite period of time.

Following the onset of the pandemic, it became necessary to hold educational sessions and meetings in the form of videoconference meetings. Videoconferencing was a critical tool that allowed universities and many businesses to continue working during a “shelter-in-place” phase. Zoom in particular helped hundreds of millions of people by making videoconferencing free and easy to use (Bailenson, 2021). However, migrating from traditional or blended learning to a fully virtual and online delivery strategy will not happen overnight and thus has been associated with many challenges (Crawford et al., 2020). In general, an entirely online course requires an elaborate lesson plan, teaching materials such as audio and video contents, as well as technology support teams. Due to the sudden emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic and its related public health measures, most faculty members had to face diverse challenges regarding online teaching, such as lack of experience with planning and conducting online courses, no time for early preparations, and lack of support from educational technology teams (Bao, 2020).

The challenge of this transition, however, did not only affect the university staff, but also the students. For both groups, the rapidly changing work and study arrangements were deemed to cause work or study-related stress, which might be affected by a number of personal stressors including having to work remotely, having to change tasks, and having to combine all of this with home-schooling children and caring for shielding elderly family members or neighbors (Der Feltz-Cornelis et al., 2020). The literature concretizes various additional problems that arise when teaching and studying at home during the pandemic: Firstly, there are a wide range of distractions from teaching and studying at home. Secondly, not all lecturers and students are able to find suitable spaces for teaching and studying. Thirdly, teaching and studying can be constrained by insufficient hardware and an unstable network at home (Zhang et al., 2020). Psychological symptoms such as worries, physical symptoms due to stress, especially stress due to remote working and living circumstances might lead to reduced work productivity related to the COVID-19 outbreak (Der Feltz-Cornelis et al., 2020). Other negative impacts include the feelings of isolation and disconnectedness that may be experienced during lockdown and remote working (Williams et al., 2020). It is therefore unsurprising that findings suggest pre-existing mental health crises in universities could worsen, not only for students but also for academics who may struggle to reconcile the increased demands with their needs at home, and who must forfeit their right to a good work-life balance (Watermeyer et al., 2021).

The changed working and studying conditions during the pandemic were not only a challenge for the wellbeing of university staff and students. The professional social work curriculum was also reaching its limits due to increased distance teaching and learning. There are compulsory elements of the curriculum that cannot be offered as part of distance learning, such as internship, which measures the capabilities or competencies of students to enable them become a qualified social worker (Azman et al., 2020). Crucial to social work education is the mutual reinforcement of academic and practical learning, which includes the process of socialization in the academic and professional community of social work, learning through exposure to complex and ill-structured social practice and through reflection on the interface between scientific knowledge, practice knowledge and service users` knowledge (de Jonge et al., 2020). The adapted forms of teaching and learning also present challenges from a didactic point of view. Research has found that when undergraduate social work students have an experience of “being known” by instructors and classmates, their motivation to learn, ask questions, and engage with course material increases (Rodriguez-Keyes and Schneider, 2013). Thus, it is apparent that there are limits to distance learning in social work education for the reasons mentioned above. However, in times of pandemic, universities for social work have no choice.

Although a vaccine first became available in December 2020, there are concerns about the long-term effects of COVID-19 on the educational sector. The pandemic has served as a “digitalization booster,” and this could be seen as a positive consequence. Nonetheless, it is necessary to consider the extent to which distance learning should be included in the social work curriculum in post-pandemic times. Furthermore, it is necessary to determine how lecturers as well as students can be supported to make the best use of these new forms of teaching and learning. Thus, the experience of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic needs to be carefully evaluated and strategies developed to inform how social work colleges can adapt after COVID-19.

In consideration of this issue, the present study will examine the experiences of staff and students at the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts–School of Social Work, Switzerland (hereafter Lucerne School of Social Work). Specifically, it will identify which work or study-related situations university staff (lecturers and scientific staff) and students experienced as challenging during the first lockdown (first COVID-19 wave) in spring 2020. The perspectives of both university staff and the students were gathered in order to understand differences and similarities in the challenges experienced. The aim of this study is to analyze the teaching and learning situation of staff and students during the first lockdown in spring 2020 and once again during the period of relaxed sanitary measures in summer 2020. Evidence is needed to inform recommendations on which structural measures can be used to support staff at the Lucerne School of Social Work so that they can best fulfill their educational mission in times of the current pandemic and the period thereafter. Moreover, strategies must be developed to ensure that students achieve good educational outcomes, even in times of a pandemic.

In April 2020, the Lucerne School of Social Work in Switzerland launched the longitudinal study “Remote work and studying during the COVID-19 pandemic” with two survey waves among university staff and students. The first survey lasted from April 23, 2020 through the end of May 2020, i.e., during the lockdown. The second survey started on June 15, 2020 and staff and students’ responses were received until August 14, 2020. This period coincided with the time of relaxed sanitary measures.

This study explores the following research questions.

1. To what extent did the workload of staff and students change during the first wave of COVID-19 in spring 2020, and the period of relaxed sanitary measures in summer 2020?

2. What challenges and opportunities did staff and students identify during that period in relation to remote work, distance learning, and distance teaching?

3. In what way(s) did the staff and students feel supported by the university management? The body of knowledge regarding the psychological and societal impacts of the pandemic and the related public health measures is growing constantly. For example, studies now indicate that there has been an increase in psychological distress for university staff and students (Der Feltz-Cornelis et al., 2020; Fornili et al., 2021). Similarly, findings from Swiss universities have revealed, that students during the lockdown were on average more depressed, slightly more anxious, more stressed, and felt more lonely than half a year earlier (Elmer et al., 2020). Therefore, using the data collected through the research project "Remote work and study during the COVID-19 pandemic", additional analysis was conducted on the following questions:

4. How psychologically distressed were the university staff and students?

5. Was there a possible association between perceived support by the University to work/study from home and the level of psychological distress?

Regarding the latter, we assumed that staff and students’ stress levels would be lower in circumstances where they felt supported by the University.

The survey has been designed and conducted using the Enterprise Feedback Suite (EFS) Survey by Questback. All employees and students at the Lucerne School of Social Work were invited to participate by email. They were informed about the purpose of the survey and about their anonymity and right to withdraw. All participants voluntarily gave their informed consent to participate. The Ethics Committee Northwest and Central Switzerland approved this study.

A total of 139 employees were registered as working at the Lucerne School of Social Work, in 2019. Of these, 79 were lecturers, 26 were scientific collaborators and 34 were administrative or technical staff (University of Applied Sciences and Arts, 2019). The responses of those who were directly involved in social work education, i.e., lecturers and scientific collaborators were considered in this study. From 105 employees (lecturers and scientific collaborators) 51 individuals participated in the first survey (response rate: 48,6%). The response rate was lower in the second survey: 28 employees took part. The response rate for the university staff is therefore 26,7%.

779 students were following an undergraduate degree course in 2019. An additional 50 students were enrolled in a master's program (hereafter all referred to as “students”) (University of Applied Sciences and Arts, 2019). Of the total 829 students, 225 participated in the first wave of the survey (27.1%). The response rate was lower in the second survey: 117 students took part. The response rate for the students is 14.1%.

In total, therefore, 276 respondents (both staff and students) took part in the survey in spring 2020 and 145 in summer 2020. Due to the relatively low response rate, it is noted that the results are not representative. The IDs of the participants were not linked. For this reason, the data from the first survey and second survey are treated as independent samples and a group comparison was carried out.

We asked participants to report on their gender (male, female, other), age, nationality, and highest achieved education (see Table 1).

The change in workload was measured with a self-constructed item “How has your work/study-related workload changed in the last 30 days?” The following answers were possible: 1) Reduction in workload 2) Additional workload due to COVID-19-related transition 3) Less capacity due to care responsibilities 4) Increased workload due to additional tasks 5) Workload remains unchanged 6) No response. Multiple answers were possible (see Figure 1).

Respondents could rate a total of five self-constructed statements using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = disagree, 2 = somewhat disagree, 3 = somewhat agree, 4 = agree, 5 = no response). 1) I feel sufficiently supported by the University to be able to work from home, 2) I have the necessary facilities to work/study from home, 3) I think the University is managing the situation related to the COVID-19 pandemic well 4) I think the University is communicating the changing conditions regarding the COVID-19 pandemic well 5) I find the University cares about my wellbeing (see Table 2).

The students could rate a total of three statements using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = disagree, 2 = somewhat disagree, 3 = somewhat agree, 4 = agree, 5 = no response). 1) I personally believe that I am adequately informed about the further process for my studies (exams, internships, etc.), 2) I feel well supported by the lecturers in continuing my studies, 3) A transition to distance learning should also be sought for the period after the COVID-19-pandemic (Sann et al., 2020) (see Table 3).

In the first survey, university staff and students were asked in an open-ended question on the one hand about the currently perceived challenges of working at home, distance teaching and distance studying (what are the challenges), and on the other hand what they experienced as positive in this regard (what works well).

In addition, the survey included a validated anxiety scale. The 4-item Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) is a rapid self-reported measure. Respondents rate their symptoms using a 4-item Likert rating scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (almost every day), and the total score ranges from 0 to 12 (Löwe et al., 2010). We used Cronbach’s α to measure the scale’s reliability – the internal consistency. The PHQ-4 is a well-validated screening instrument, demonstrating a high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.81) (Cronbach et al., 1951). The scale categorizes the severity of clinically relevant depression and/or anxiety according to the PHQ-4 score, as follows: Normal (0–2), Mild (3–5), Moderate (6–8), Severe (9–12).

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and correlations. Due to a lack of normally distributed dependent variables (e.g., psychological distress), we used Spearman rank correlation to measure the associations between “Perceived support from the University” and “Psychological distress.” For the same reason, Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare differences between two independent groups (e.g., differences in perceived support in spring and summer 2020). To investigate effect size we used Pearson`s product-moment correlation coefficient r. A correlation coefficient of 0.10 is thought to represent a small effect, a coefficient of 0.30 a moderate, and one of 0.50 a large effect (Cohen, 1988). We used IBM SPSS 27 for the statistical analyses.

The analysis of the open-ended questions on "Challenges and opportunities in relation to remote work, distance learning and distance teaching" was carried out in two steps: Firstly, the data were extracted from SPSS; secondly, categories were inductively formed for each question following the qualitative content analysis, drawing from Mayring (2007). This step was conducted in a paper-based manner. The answers were then assigned to the respective categories and interpreted. Finally, the inductive categories for both questions were compared and contrasted. The analyses were conducted separately for the group of employees and for the group of students.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the survey participants from the first survey (T1) and the second survey (T2).

Among the university staff, slightly more females than males participated (54.9% in the first survey and 53.6% respectively in the second survey). The average age was 45.2 years for the first survey and 46.5 for the second survey. 53.6 and 78.6% respectively had Swiss citizenship. It is natural to expect that all employees had a tertiary degree.

The high proportion of female students (79.1 and 80.3% respectively) who participated corresponds to the fact that the proportion of women at the Lucerne School of Social Work is 72% (University of Applied Sciences and Arts, 2019). The average age was 29.7 and 30.3 years, respectively. The relatively high average age can be explained by the fact that some of the students were already working in a profession, social work constitutes their secondary education. Most students who participated in the survey were students with Swiss citizenship (92.9 and 94.9% respectively). It is worth noting that 33.8 and 41.9% of the participating students, respectively, already had a tertiary degree.

At the time of the lockdown in spring 2020 and the relaxed sanitary measures in summer 2020, all employees of the University were employed at a minimum of 50%, which corresponds to a workload of 21 hours per week. 69.8% of the students were employed for at least 50% (n = 157), 29 students were employed between 10 and 40% (12.9%) and 37 did not work at all at the time of the survey (16.4%). However, the workload at which one is employed does not always reflect the effective workload. For this reason, staff and students were asked how the actual workload changed between spring and summer 2020. To answer this question, respondents had a total of five answers (multiple responses). Since each answer option in the respective sections refers to a percentage in relation to the total sample, the sum of each category does not have to equal 100% (see Figure 1).

What is most striking about the results is that in the spring of 2020, a total of 80.4% of the employees reported that they had managed a higher workload because of the immediate transfer to online working. Only 7.8% of faculty staff reported that they had less to do. 11.8% had extra work due to assignments directly related to the pandemic. 23.5% indicated that they had less capacity due to care responsibilities (children or relatives in need of care). Due to the closure of schools, kindergartens and daycare centers in the spring of 2020, employees often had to organize not only their own work or studies but also provide childcare and home schooling (depending on the age of their children). As of May 11, 2020, school or kindergarten classes resumed, which meant relief for parents or for family caregivers. Thus the situation appeared to have eased somewhat in the summer of 2020. However, 60.7% of employees continued to report that they had a higher workload due to online course delivery. 17.9% continued to report having less capacity to work at the University because of care responsibilities.

In spring 2020, students also experienced a significant amount of extra work due to the transition (59.1%). The situation had eased by the summer, where only 38.5% reported that they had additional workload due to COVID-19. Workloads due to care responsibilities (children or relatives in need of care) are somewhat less pronounced among students than among employees: Nonetheless, this affected 10.2% of students in spring 2020 and 3.4% in summer 2020 (see Figure 1).

Staff were asked to rate five statements about perceived support from the University in relation to home working (see Table 2). Statements were rated, on a scale from 1 (“disagree”) to 4 (“agree”). Between 46 and 48 respondents answered the total of five questions in the first survey and between 26 and 28 respondents answered the questions in the second survey (see Table 2). What is most striking is that the perceived support received from university management decreased over time (between spring and summer 2020). Currently, we can only speculate about the reasons for this. It is possible that for example, expectations for university management to take action to address the enlarged workload increased over the continued pandemic. If such responses are not forthcoming or are not considered sufficient, this can lead to staff feeling a lack of support. Working under highly volatile and possibly less than optimal conditions for an extended period adds to the frustration. It is likely that the form of communication used by university management also influences whether employees perceive that they are supported. However, a significant difference in responses between the two points in time was found for the statement “I feel sufficiently supported by the University to be able to work from home” (see Table 2), even though the effect size is small (r = 0.28). The statement that received the highest level of agreement both in spring and summer 2020 was “The University cares about the wellbeing of employees.”

The students were asked to rate three statements about perceived support from the University using a 4-point scale from “do not agree” (1) to “agree” (4).

Between 207 and 210 respondents answered the total of three questions in the first survey and between 114 and 116 respondents answered the questions in the second survey (see Table 3). Overall, the students reported feeling significantly more supported by the University in summer 2020 than they did in spring, even though effects were only small (see Table 3). This is exactly the opposite experience to that reported by university staff. A plausible reason for this is that the second survey occurred after the exam session. The tension inherent to this assessment period may therefore have eased somewhat. The students also seemed to have become more used to the situation over time. Overall, the results demonstrated that the students felt supported by the lecturers. What is particularly remarkable is that the support for the statement that distance learning should be maintained after the pandemic had increased during the summer. This result is particularly important with regard to the University’s strategy on distance learning in the post-pandemic times.

In the first survey, which was conducted in the spring 2020, university staff were asked in an open-ended question about the currently perceived challenges of distance teaching on the one hand and on the other hand what they experienced as positive in this context. 34 respondents (66.7%) answered this question. Eight inductive categories were formed and assigned to the statements, drawing upon the qualitative content analysis according to Mayring (2007), which are highlighted below (additional workload, lack of direct (informal) exchanges, technical aspects, aspects of the social work curriculum, motivated students, familiarization with new teaching formats, didactic implementation, flexibility of the colleagues).

As mentioned earlier, the additional workload associated with the transition was the biggest challenge for university staff (n = 15). Specifically, the development of didactic concepts that had to be adapted for distance teaching was mentioned. Likewise, communication with the students in a distance teaching format proved to be more time-consuming. Instead of face-to-face instruction, information was now communicated via email or Zoom meetings, which had to be organized.

Another frequently mentioned difficulty was the lack of direct (informal) exchanges with the students (n = 13). The interactive exchange was also limited via Zoom. The lecturers had the impression that the students were also inhibited from asking questions if something was unclear. It was felt to be frustrating that there were limited opportunities to observe student responses. Associated with the limited ability to directly communicate is the additional challenge of moderating and keeping a discussion going in a distance teaching format. This makes it difficult both to build relationships with students and to measure learning outcomes.

Aspects concerning technical difficulties were also mentioned and the fact that not all lecturers and students have the necessary digital literacy was also perceived as problematic (n = 6). Three respondents specifically mentioned the short time in which they had to manage the digital transition and two mentioned that they did not receive the required software licenses in time. Despite the difficulties mentioned, when asked what worked well in distance teaching ten lecturers mentioned the technology and the support provided by the IT support team.

Five respondents also stated that familiarizing themselves with new formats and dealing with new media had worked out well (“technical challenges are feasible”), and that the didactic implementation had been successful.

Since learning how to conduct conversations is an important matter relating to aspects of the social work curriculum, three lecturers stated that part of the curriculum could not be implemented in the distance format. Moreover, study excursions, by their very nature, could not be offered as a digital substitute.

When asked what worked well in distance learning, some lecturers reported that the students were accommodating and motivated (n = 10). The flexibility of colleagues or external lecturers was mentioned by two respondents. Not all indicators were mentioned as either an opportunity or a challenge. In summary the issue that concerned the university staff most was the increased workload. Furthermore, there was a clear uncertainty regarding the application of digital teaching methods. It is obvious that digitization at universities needs to be supported by IT staff. Thus, strategies regarding teaching in the context of adapted learning environments are necessary.

Alike to university staff, students were asked what they experienced as challenging in distance learning and what worked well. 194 students (86.7%) provided responses to the questions. As mentioned above, inductive categories were formed and assigned to the statements. The analysis resulted in 13 main categories (additional workload due to distance learning, direct (informal) exchanges, interactive sequences, organizational matters, exams, inconsistency in distance learning, quality of teaching and instructional design, learning outcome, self-management, independent processing of assignments and the (non-collaborative) elaboration of the course material, learning environment and other life domains, aspects of the social work curriculum, technical aspects associated with distance learning).

Overall, students reported a large additional workload due to distance learning or high demands was a notable difficulty related to distance learning (e.g., more, or excessive amounts of course content, more time required for exchanges, assignments too extensive or too numerous; n = 30). However, as an advantage of distance learning, five respondents named the fact that commuting was no longer necessary. This aspect is particularly important since many students live in other cities.

A total of 42 students indicated that they strongly missed the direct (informal) exchanges during the lockdown. The lack of or reduced (informal) exchange with students and lecturers and thus the resulting loss of support was mentioned most frequently (n = 19 students). However, 27 respondents, stated that (informal) exchange and support worked well within distance learning, for which both lecturers (n = 11) and fellow students were mentioned as a source of support (n = 15). The interactive sequences in class were partly perceived as cumbersome and exhausting (n = 47).

Many students experienced discussions in the digital classroom as difficult and perceived them as more sluggish and boring than in face-to-face classes. Group work in distance learning was also perceived as more demanding and strenuous (n = 40). However, there were also twelve respondents who felt that the opportunities for interaction in distance learning were positive.

Regarding organizational matters, especially systematic storage and access to teaching materials, a total of 34 students mentioned difficulties. In contrast, 38 students specifically mentioned these aspects when asked what had worked well in distance learning. While 17 respondents mentioned the late or short-term accessibility of teaching materials or the difficult access to materials or books as difficulties, 30 students stated that precisely this aspect worked well in distance learning.

Uncertainties regarding the exam (e.g., procedure, other related information) were mentioned as difficulties by four students. On the other hand, six students stated that the above-mentioned aspects worked well.

In relation to inconsistencies in distance learning, 10 students mentioned difficulties due to the lecturers designing the various lessons in distance learning, differently (e.g., creating different workflows).

A total of 34 students mentioned difficulties in distance learning relating to the quality of teaching and instructional design. In contrast, 68 students reported that these aspect features had worked well during distance learning. More specifically, 25 students complained that the structure, the design and/or the preparation of the teaching material had not been (equally) appropriate in all modules. In contrast, 55 students stated that this had worked well (for the majority). Five students complained that on some occasions, the lecturers' instructions had not been clear or comprehensible enough (e.g., with regard to learning objectives or assignments), whereas this was mentioned by 20 students as something that had worked well. Only one student felt that the lecturers' guidelines were too narrow. Some students also criticized the lack of oral input by the lecturers, or the insufficient feedback given on the assignments (n = 4), while three felt this had worked well.

Some students considered the learning outcome from distance learning approaches to be less effective, they perceived or at least feared a loss of quality of learning or questioned the quality of learning (n = 7). In contrast, two students stated that they were able to learn some content well or even more effectively due to distance learning.

The distance learning modality also received some criticism, or a lack of acceptance, from students due to the increased challenges associated with a greater need for self-management. A total of 38 students mentioned difficulties in terms of motivation (n = 18), self-discipline (n = 18) and concentration (n = 11). In contrast, seven students reported that self-management worked well.

The independent processing of assignments and the (non-collaborative) elaboration of the course material was perceived as a challenge by a total of 29 students (e.g., difficulties in understanding and lower retention rates). In contrast, 47 students reported that this worked well for them, and particularly appreciated the flexible scheduling.

33 students mentioned one or more difficulties relating to the learning environment and other life domains (e.g., due to distractions, other people in the house, the combination of studying and homeschooling, no suitable place of work available or insufficient equipment, not enough time for studying due to demands from other life domains). Five students explicitly mentioned long periods of screen use as problematic. The maintenance of the work-life balance or the delimitation of the different areas of life was explicitly mentioned as a difficulty by six respondents. Two students saw it as a problem that the regular (daily) structure has disappeared. On the other hand, four respondents stated that the work-life balance could also be implemented effectively during distance learning and 13 students stated that their learning environment in distance learning was advantageous.

Twelve students mentioned, among the perceived difficulties, that certain contents or modules related to aspects related to the social work curriculum were unsuitable in the context of distance learning (e.g., interviewing, study trip, practice projects). 11 students, on the other hand, were explicitly convinced that distance learning is also well suited for social work education.

51 students believed that the technical aspects associated with distance learning worked well. In contrast, 14 respondents reported difficulties in the technological aspect of distance learning. The difficulties mentioned included technical malfunctions, the technical effort in general or insufficient technical capacities or the unsuitability of specific tools (e.g., “Zoom”).

It is obvious that there are different points of view regarding the implementation of the new forms of distance learning, which were used due to COVID-19-pandemic. In general, however, the students coped well with the situation. It is also apparent that self-management-competencies had become even more important in the context of distance learning. It is therefore important to empower students to develop the appropriate competencies.

Considering the findings relating to perceived support, additional research was conducted to determine how stressed university staff and students were and whether the level of perceived support from the University had an impact on the level of psychological distress experienced by staff and students.

The level of psychological distress was assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4). On average university staff tended to show signs of mild psychological distress during the first lockdown in spring 2020 (see Figure 2). Accordingly, about half of this group showed no signs of psychological distress (n = 25; 49.0%), 15 respondents showed signs of mild psychological distress (29.4%), and three showed signs of moderate psychological distress (5.9%). In summer 2020, respondents showed less psychological distress (see Figure 2). About two thirds (n = 18; 64.3%) showed no signs of psychological distress, and nine respondents (32.1%) showed mild psychological distress according to the PHQ-4. A Mann-Whitney-U-Test was carried out to determine if there were differences in levels of psychological distress in spring and summer 2020. There was no statistically significant difference in the levels of psychological distress between both groups, U = 513.500, Z = -0.822, p = 0.411.

All in all, at both points in time, students showed higher levels of psychological distress than university staff (see Figure 2). Although 87 students (38.7%) showed no signs of psychological distress during the lockdown, 80 respondents (35.6%) experienced mild psychological distress, 19 students (8.4%) showed signs of moderate distress, and nine showed signs of severe psychological distress (4.0%). However, in summer 2020 less students showed signs of psychological distress. At this time, more than half of the respondents (n = 66; 56.4%) showed no psychological distress, 40 (34.2%) mild psychological distress, 5 (4.3%) showed signs of moderate and 1 of severe psychological distress. This difference in levels of psychological distress in spring and summer 2020 was statistically significant, U = 8,743.500, Z = −2.942, p = 0.003, r = −0.17. That is, students felt significantly more stressed during the lockdown in spring 2020. In addition, the results indicate that students felt more distressed during the lockdown in spring 2020 and in the summer 2020 than university staff, even though these differences were not statistically significant (see Table 4). However, stress levels in both groups decreased after the lockdown. A plausible explanation for this difference could be the levels of perceived support received by both groups from the University.

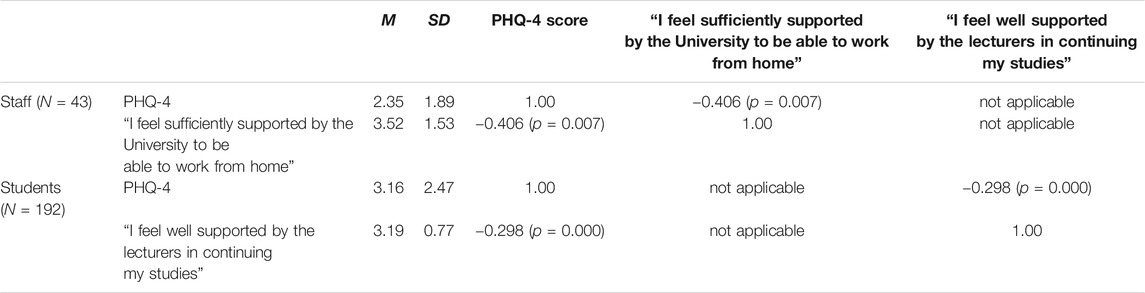

As expected, employees and students who felt more supported by the University experienced less psychological distress. Accordingly, we found a moderate statistically significant negative association between the staff’s perception of being sufficiently supported by the University to work from home and their level of psychological distress (PHQ-4) (see Table 5). For students, an association between their stress level and their feeling of being supported by lectures in continuing their studies was also negative and statistically significant but weak.

TABLE 5. Association between level of psychological stress and feeling of support by the University (spring, 2020).

Students were more stressed at both time points but felt better supported. Combined with the finding that the relationship between stress and perceived support was weak for students but moderate for staff, this suggests an important difference between the two groups: it seems plausible that to reduce work-related or work-associated distress, perceived support from the employer is more important than when it is not an employer-employee relationship. It is probably the case that other sources of support have been more important to students, such as family or friends. Accordingly, perceived support from the University was only able to reduce students' stress levels to a limited extent.

This study examined how staff workload and student educational situations changed during the first wave of COVID-19 (spring 2020) and following the first wave (summer 2020). Not surprisingly, the workload increased for both university staff and students. This result corresponds with the evidence that the teaching transition involved a heavy workload (Bao, 2020). The additional workload for the staff was primarily because courses had to be redesigned, which requires a great deal of effort (Crawford et al., 2020). As the findings of the present study indicate, employees had extremely limited time resources available for this purpose. Effective distance and online teaching requires the use of distinctive skills and abilities on the part of the qualified academic staff and the availability and skills of a learning design team to train and facilitate this implementation of distance and online courses (Davis et al., 2019). The problem with the additional workload was exacerbated for those staff and students who had to take care of children or relatives. A study also conducted at the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences which examined this particular issue, revealed that women with care responsibilities were particularly affected by the additional workload (Lanfranconi et al., 2021).

University staff already had the option to work remotely before the pandemic. However, the responses of the staff made it clear that a workplace at the University has more functions than just completing the work that needs to be done. Personal contact with colleagues and students is very important. This trend is reflected in research as well. Prior to the pandemic, the option of remote working under flexible work policies was typically used by companies to attract talented employees. When remote work is imposed rather than voluntarily chosen, and when it is implemented by individuals with limited experience of remote working, switching to remote work as the only option for employees poses a significant challenge (Li et al., 2020). The results do not provide a clear picture of whether students work more effectively at home. One plausible challenge is that some students are less well equipped for working remotely, for example because they live in shared apartments and have less space available. It is also possible that they have limited experience of distance learning.

As a tendency, it can be stated that both staff and students felt partially or rather well supported by the university management. It is striking that the perceived support from the University decreased among the university staff in summer 2020 compared to spring, while the students felt better supported in summer. Regarding the employees, it is likely that dissatisfaction tended to emerge after the increased workload could not be reduced to the desired extent. From the answers to the open-ended questions, it appears that the students appreciate the lecturers’ efforts to make the best of the situation. Nevertheless, numerous implications can be derived from the results of the open-ended questions should the pandemic situation persist. Students need the security of being able to plan their studies. Furthermore, even in times of crisis, consistency is needed regarding teaching, including the finer details of document storage, deadlines and information on the exams.

However, the changes in education also make differences in self-management-competencies between students more visible. The results suggest that some students experienced problems with self-management in the context of distance learning. This finding is in line with previous research results: Some students can study quite independently and create an appropriate rhythm of study and private activities. Others find this quite difficult because, in their own words, they lack sufficient self-discipline, concentration and time self-management skills. This group is more dependent on the regularity of lessons and the support from teachers, but in an asynchronous learning network they have to do without these benefits (de Jonge et al., 2020). It is therefore the lecturers' task to empower the students with suitable didactic concepts to acquire the corresponding competencies.

While digitization in social work education has so far been approached rather hesitantly (Smoyer et al., 2020), the pandemic acts as a digitization booster. It is likely that forms of teaching and exchange that had to be used in times of the pandemic will also be pursued in post-pandemic times. One such example being international Zoom conferences, which, in addition to saving time resources, also makes sense in terms of protecting the environment by minimizing travels. Within this context, the question is raised as to how the digital literacy and self-management-competencies for students can be enhanced to prepare them optimally for their future working lives. Despite the many advantages, exclusively digitalized social work training is not an option for the post-pandemic period. Several staff and students were concerned about the lack of direct exchange on the one hand and the form of exchange, mostly via Zoom, on the other. Some emphasized that a digitally delivered course or digital video conferencing is exhausting. Several explanations for “zoom fatigue” can be found in the literature: Excessive amounts of close-up eye gaze, cognitive load, increased self-evaluation from staring at a video of oneself, and constraints on physical mobility (Bailenson, 2021). Thus, teaching via video, e.g., Zoom, is not equivalent to face-to-face teaching. Moreover, it was clearly expressed that important components of social work training, such as interview skills training, are difficult to implement in a digital environment. It is obvious that study journeys and field practice experience cannot be conducted digitally. Considering that practical training is of central importance in social work, it can be stated here that distance learning is not the exclusive future model of training.

However, given that digitization is playing an increasingly important role in all areas of work, the fact that the pandemic has led to an increase in digital literacy among both staff and students is certainly a positive development. Thus, digital literacy is no longer a “nice to have” but indispensable competence for both staff and students. Since the pandemic is likely to be followed by a return to traditional classroom teaching, strategies need to be developed to ensure that future students can benefit from the experience and learning gained. Accordingly, the acquisition and continued use of digital literacy skills will need to be ensured within the curriculum. There are many reasons to believe that COVID-19 has created “a new normal” for the universities—one that will continue after the pandemic (Lischer et al., 2021).

An important finding of the study is that a proportion of both students and staff experienced high levels of psychological distress at both time points, with those of students being higher than those of university staff. This is surprising because overall, students indicated that they felt well supported by faculty staff. Based on the present results, we can only speculate as to why this is so. However, findings suggest that students, as well as the general population, may be experiencing psychological effects from the outbreak of Covid-19, such as anxiety, fear, and worry, among other reactions (Cao et al., 2020). Further results demonstrate that reduced social interactions, lack of social support, and emergent stressors related to the COVID-19 crisis can have a negative impact on students’ mental health (Elmer et al., 2020). However, the finding that students were more stressed than staff can also be well explained in terms of developmental psychology: Middle-aged people have more effective stress management strategies than younger people. For example, they are often more practiced at preparing for and dealing with challenging situations (Aldwin et al., 2010). This seems to be a plausible explanation. However, we do not know the extent to which these psychological symptoms were pre-existing or whether they were solely related to the COVID-19 crisis. What is important is the finding that staff and students who felt more supported by the university management experienced less psychological distress. It can be assumed that the pandemic will have longer-term implications for the stress levels of both employees and students, and the university management should give this issue due consideration. It is particularly important that the levels of well-being and psychological health of the employees is monitored from time to time and that appropriate actions are taken in response, such as occupational health management measures. Likewise, appropriate measures are needed for students who are affected by psychological distress, such as low-threshold counseling.

This study investigated university staff and students` experiences, over time and compared their responses. Thus, insights into social work education since the beginning of the pandemic are provided. However, the present study has several limitations. The response rate for the second wave of the survey was relatively low, therefore the responses cannot be regarded as representative. Thus, the results have an explorative nature. Since the data was not linked at a personal level, no intraindividual comparison between the responses of the two surveys was possible. Furthermore, data on certain variables such as course type (full-time or part-time) and year of study was not collected. Nevertheless, the group comparison provides important insights into how employees and students coped with the transition period. Within the scope of the survey, we generated evidence of how the psychological stress of university staff and students changed between spring and summer 2020. However, we do not know how the perceived stress levels of the employees has changed compared to the time before COVID-19.

Social work will need to develop new ways of dealing with the “new normal” in the post-pandemic period. It is therefore important that the experiences gained are carefully evaluated and incorporated into the didactic concepts. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, there has been an effort to develop hybrid forms of teaching (e.g., a combination of face-to-face-classes and distance learning). These will increasingly have to rely on distance learning as a complement to traditional classroom teaching, e.g., in the form of blended learning. Schools of Social Work are particularly challenged because the curriculum contains building blocks that are difficult to implement in the form of distance learning. However, the results indicate that some learning content can certainly be taught in the form of distance learning. These newly developed forms of learning should be used to empower students to acquire the digital skills they need for their future careers. Any future adjustments to the curriculum must therefore be critically evaluated. Distance learning, for example, must not be used to replace face-to-face teaching to economize. Moreover, adaptations to the learning curriculum must not involve an excessive increase in workload. University personnel need the time and resources to implement the innovative teaching practices on an evidenced-based foundation.

In addition to the implications of the study on the curriculum, implications related to employee and student well-being can also be derived. An important finding of the study is that both staff and students who felt supported by the university management were less distressed. Accordingly, it is the responsibility of university management to carefully monitor the needs of both groups in this regard and to take appropriate actions.

The dataset presented in this article is not readily available. Once we have clearance from the University’s ethics committee, data will be made accessible. Requests to access the dataset should be directed to c3V6YW5uZS5saXNjaGVyQGhzbHUuY2g=.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee Northwest and Central Switzerland. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

SL: Conceptualision, methodology, funding acquisition, project administration, writing original draft. SC: formal analysis, methodology PK: formal analysis, NS: Conceptualisation, data curation sentence point CD: Writing–original draft (supporting).

This work was supported by the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts–School of Social Work.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all employees and students who participated in the survey.

Aldwin, C. M., Yancura, L. A., and Boeninger, D. K. (2010). “Coping Across the Life Span,” in Handbook of Life-Span Development:. Editors M. E. Lamb, A. M. Freund, and R. M. Lerner (Hoboken, NJ: Social and emotional development), 298–340.

Azman, A., Singh, P. S. J., Parker, J., and Ashencaen Crabtree, S. (2020). Addressing Competency Requirements of Social Work Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Malaysia. Soc. Work Edu. 39 (8), 1058–1065. doi:10.1080/02615479.2020.1815692

Bailenson, J. N. (2021). Nonverbal Overload: A Theoretical Argument for the Causes of Zoom Fatigue. Technol. Mind, Behav. 2 (1). doi:10.1037/tmb0000030

Bao, W. (2020). COVID ‐19 and Online Teaching in Higher Education: A Case Study of Peking University. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Tech. 2 (2), 113–115. doi:10.1002/hbe2.191

Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., et al. (2020). The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Epidemic on College Students in China. Psychiatry Res. 287, 112934. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdle. Erlbaum. Conner BE. ISBN 10 0805802835.

Crawford, J., Butler-Henderson, K., Rudolph, J., Malkawi, B., Glowatz, M., Burton, R., et al. (2020). COVID-19: 20 Countries’ Higher Education Intra-period Digital Pedagogy Responses. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 3 (1), 1–20. doi:10.37074/jalt.2020.3.1.7

Cronbach, L. J. C., Greenaway, R., Moore, M., and Cooper, L. (1951). Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of testsOnline Teaching in Social Work Education: Understanding the Challenges. Psychometrika 16 (3), 297–334. doi:10.1080/0312407X.2018.152491810.1007/bf0231055520197213446

Davis, C., Greenaway, R., Moore, M., and Cooper, L. (2019). Online Teaching in Social Work Education: Understanding the Challenges. Aust. Soc. Work 72 (1), 34–46. doi:10.1080/0312407X.2018.1524918

de Jonge, E., Kloppenburg, R., and Hendriks, P. (2020). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social Work Education and Practice in the Netherlands. Soc. Work Edu. 39 (8), 1027–1036. doi:10.1080/02615479.2020.1823363

Der Feltz-Cornelis, V., Maria, C., Varley, D., Allgar, V. L., and De Beurs, E. (2020). Workplace Stress, Presenteeism, Absenteeism, and Resilience Amongst university Staff and Students in the COVID-19 Lockdown. Front. Psychiatry 11, 1284. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.588803

Elmer, T., Mepham, K., and Stadtfeld, C. (2020). Students under Lockdown: Comparisons of Students' Social Networks and Mental Health before and during the COVID-19 Crisis in Switzerland. PLoS One 15 (7), e0236337. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0236337

Fornili, M., Petri, D., Berrocal, C., Fiorentino, G., Ricceri, F., Macciotta, A., et al. (2021). Psychological Distress in the Academic Population and its Association with Socio-Demographic and Lifestyle Characteristics during COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown: Results from a Large Multicenter Italian Study. PLoS One 16 (3), e0248370. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0248370

Lanfranconi, L. M., Gebhard, O., Lischer, S., and Safi, N. (2021). Das Gute Leben im Lockdown? Unterschiede Zwischen Frauen und Männern mit und Ohne Kinder im Haushalt während des COVID-19-Lockdowns 2020: Befragung an einer Deutschschweizer Hochschule. [The Good Life During the Lockdown? Differences Between Women and Men With and Without Children Living in the Household During the COVID-19 Lockdown in 2020: Survey Conducted at a German-Speaking Swiss University]. GENDER-Zeitschrift für Geschlecht, Kultur und Gesellschaft 13, 29–47. doi:10.3224/gender.v13i2.03

Li, J., Ghosh, R., and Nachmias, S. (2020). In a Time of COVID-19 Pandemic, Stay Healthy, Connected, Productive, and Learning: Words From the Editorial Team of HRDI. Taylor Francis. doi:10.1080/13678868.2020.1752493

Lischer, S., Safi, N., and Dickson, C. (2021). Remote Learning and Students' Mental Health during the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Mixed-Method Enquiry. Prospects 5, 1–11. doi:10.1007/s11125-020-09530-w

Löwe, B., Wahl, I., Rose, M., Spitzer, C., Glaesmer, H., Wingenfeld, K., et al. (2010). A 4-item Measure of Depression and Anxiety: Validation and Standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the General Population. J. affective Disord. 122 (1–2), 86–95. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.019

Rodriguez-Keyes, E., and Schneider, D. A. (2013). Cultivating Curiosity: Integrating Hybrid Teaching in Courses in Human Behavior in the Social Environment. J. Teach. Soc. Work 33 (3), 227–238. doi:10.1080/08841233.2013.796304

Sann, U., Bongard, S., Frankenberg, E., and Motherby, C. (2020). Einschätzung von Abläufen im Studium Unter Bedingungen der Coronavirus-Pandemie. Unveröffentlichtes Manuskript, [Assessment of Study Procedures Under Conditions of the Coronavirus Pandemic [Unpublished manuscript]. Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften Fulda.

Smoyer, A. B., O’Brien, K., and Rodriguez-Keyes, E. (2020). Lessons Learned from COVID-19: Being Known in Online Social Work Classrooms. Int. Soc. Work 63 (5), 651–654. doi:10.1177/0020872820940021

University of Applied Sciences and Arts (2019). Lucerne School of Social Work: Facts and Figures 2019 Lucerne. Available at: https://issuu.com/hslu/docs/200508_hslu_fly_f_f19_factsheet_sa_170x240_6s_web.

Watermeyer, R., Crick, T., Knight, C. S. N., Goodall, J., Tampe, T., et al. (2021). COVID-19 and Digital Disruption in UK Universities: Afflictions and Affordances of Emergency Online migrationPublic Perceptions and Experiences of Social Distancing and Social Isolation during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A UK-based Focus Group Study. High. Educ. 81, 623–641. doi:10.1007/s10734-020-00561-yWilliams10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039334

Williams, S. N., Armitage, C. J., Tampe, T., and Dienes, K. (2020). Public Perceptions and Experiences of Social Distancing and Social Isolation During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A UK-Based Focus Group Study. BMJ Open 10. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039334

Keywords: distance learning, distance teaching, social work, COVID-19, stress, higher education, distance education

Citation: Lischer S, Caviezel Schmitz S, Krüger P, Safi N and Dickson C (2021) Distance Education in Social Work During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Changes and Challenges. Front. Educ. 6:720565. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.720565

Received: 04 June 2021; Accepted: 08 July 2021;

Published: 23 August 2021.

Edited by:

Ana B. Bernardo, University of Oviedo, SpainReviewed by:

Antonio Cervero, University of Oviedo, SpainCopyright © 2021 Lischer, Caviezel Schmitz, Krüger, Safi and Dickson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Suzanne Lischer, c3V6YW5uZS5saXNjaGVyQGhzbHUuY2g=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.