- 1Norwegian Centre for Learning Environment and Behavioural Research in Education, Stavanger, Norway

- 2Regional Centre for Child and Youth Mental Health and Child Welfare Department of Mental Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Trondheim, Norway

Attending school on a regular basis and to complete school is usually seen as a precondition for academic, emotional, and social learning and development. However, some students struggle with school attendance problems (SAPs) caused by a myriad of reasons. Homeschooling is a topic of concern in long-term or problematic SAPs cases. Some scholars claim that school absenteeism might increase and be maintained during homeschooling, while others argue that homeschooling may reduce student’s anxiety associated with school attendance. Anyway, homeschooling is often an intervention for academic learning and/or as a part of gradual reintegration to school for SAP students. Moreover, homeschooling/home education/home tuition is not a new phenomenon and is an intervention for students with long-term sickness. When schools in many countries closed from the middle of March 2020 caused by the Covid-19-pandemic, all students were given homeschooling. This gave us the opportunity to investigate homeschooling more closely in a large sample. In the current study, teachers’ thoughts, and experiences of homeschooling for students with SAPs prior to the pandemic, are investigated. The main aim was to gain more insight and knowledge about homeschooling: does it work for SAP students? Practical implications of homeschooling for SAP students are discussed.

Introduction

Attending school on a regular basis and to complete school is usually seen as a precondition for students’ academic, emotional and social development. However, some students struggle to attend school caused by many different reasons. A myriad of types of school attendance problems (SAPs) exists. Common for these students is that they have unexplained or unjustified reasons for their absences, which are associated with impairment psychologically, socially and academically both in the short- and long-term run. Some students with long-term SAPs receive homeschooling for academic learning and/or as a part of gradual reintegration to school. However, homeschooling is a topic of concern as it might maintain absenteeism. Therefore, this is a controversial topic (Kearney, 2016). Some (e.g., McShane et al., 2004; Melvin and Tonge, 2012) argue that students should not do any schoolwork at home to prevent that the student get an understanding that they can ‘attend school’ from home. Others (e.g., Kearney, 2016) argue that schoolwork at home could be given to reduce anxiety about falling behind academically and to make school-time at home like ordinary school days. Homeschooling is desired by some parents as they want to reduce their child’s stress and anxiety associated with school attendance in the short-run (e.g., Fortune-Wood, 2007; Wray and Thomas, 2013). Even though these symptoms disappear or decrease during homeschooling, symptoms may increase when the student returns to school. From the parental perspectives, some want homeschooling as an alternative to school return (Wray and Thomas, 2013). Since most studies published about homeschooling are from parental perspective, teachers’ perspectives are missing. When schools were closed during the COVID-19 pandemic, this gave us an opportunity to investigate homeschooling for a large group of students with SAPs as seen from their teachers’ perspectives.

Teachers immediately gave their students homeschooling through various digital solutions, tools, and skills, when all schools in Norway closed in the middle of March 2020 (like in many other countries), including students struggling with SAPs before the closing. No national guidelines for teachers about how to conduct homeschooling existed, however, the curriculum and the Education Act were still applicable; only the way of teaching changed. Teachers and students had to adapt to distance learning, web-based lessons, completing tasks and projects at home and other challenges like how to maintain contact. As stated by INSA (2020), “School is not out: it is only different”. The aim of this explorative study was to investigate teachers’ experiences of homeschooling during the COVID-19 pandemic for students with SAPs. Given that home-schooling is a controversial topic related to SAP students, we more specifically wanted to investigate whether teachers perceived homeschooling as something SAP students benefitted from or not.

School Attendance Problems

School absenteeism refers to both authorized and unauthorized absence (e.g., Reid, 2008; Malcolm et al., 2003; Reid, 2008). Authorized absence is when students have permission from an authorized representative of the school, and includes a satisfactory explanation, often due to illness, holidays, or emergencies in the family. Unauthorized absence is not recorded as illness or permission from the school and includes all unexplained or unjustified absences (Dalziel and Henthorne, 2005). This is usually seen as SAPs. Many types of SAPs exist, such as truancy, school refusal, school reluctance, specific lesson absence, post registration absence, school withdrawal and school exclusion (e.g., Heyne et al., 2019; Havik and Ingul, 2021). Despite the numerous types, definitions and risk factors associated with SAPs, it is common that these students are absent from school. In this study, we did not define a specific type of SAPs. We wanted to investigate teachers’ experience of homeschooling for students with any type of undocumented or unjustified SAPs. Teachers were introduced to the survey and asked to participate if they had at least one student in their class with SAP based on adapted criteria from Kearney (2008): 1) absent from school more than 2 days in the last 2 weeks before schools closed with no documented absence and/or 2) more than 15 percent undocumented absences since Christmas (10 weeks).

Homeschooling

Parents can decide to provide education for their children at home for several reasons (Department for Education, 2014). There are several reasons for parents wanting their child to be educated at home. The most common reasons as reported by parents being concern about the school environment, to provide religious or moral instruction and dissatisfaction with the academic instruction available at other schools (NCES (2009). There has been a concern that for some parents the reason for homeschooling might be to disguise child abuse and neglect. In some countries, “parent associations” promote homeschooling for students who struggle to attend school (Knox, 1989). A “homeschooling movement” has developed from a small parent-led effort to national movements in the US and the United Kingdom (Evans et al., 1993; Carroll, 1996; Bell, 1997). The number of homeschooled children is more than two percent of the total number of school children in the US (Isenberg, 2007). In the United Kingdom, the number of children recorded by local authorities as “home educated” has doubled in the last 6 years (Staufenberg, 2017). In Norway, only a few students were given home education in 2019–20 in line with the Educational Act § 2–13. However, not all these cases are registered in Norway (Beck, 2009). Moreover, homeschooling during the COVID-19 pandemic differs from regular home education/home tuition, because all students had homeschooling and it was not motivated by parents’ or students’ problems or needs. The aim of the study is to investigate teachers’ perceptions of how students with SAP before the onset of the pandemic responded and handled homeschooling. This is interesting given that doing schoolwork at home often is considered as an intervention for students with SAPs and/or as part of preparation for gradual school return (e.g., Carroll, 1996; Thambirajah et al., 2008). No systematic evaluation has compared gradual exposure and full-time increase, except a recent study from Japan showing that a rapid return approach might be effective for adolescent school refusers who are unwilling to attend individual therapy sessions (Maeda and Heyne, 2019). The findings from a classical study by Blagg and Yule (1984) showed that a combination of homeschooling and psychotherapy was least effective for school return, while behavioral therapy, with rapid return to school, was most effective. Standard treatments for anxiety-based school refusal are relaxation training, gradual reintroduction and exposure to school and cognitive behavioral therapy (King et al., 2000), family therapy or parent training (Kearney and Beasley, 1994; Place et al., 2000), medication/pharmacotherapy (Bernstein et al., 1990; Lauchlan, 2003; Kearney, 2007), or behavioral approaches (Kearney and Silverman, 1990).

Homeschooling for students with SAPs is a controversial topic (Kearney, 2016). Some scholars praise homeschooling for refusers (Stroobant and Jones, 2006), while others do not recommend homeschooling because it might promote avoidance (Melvin and Tonge, 2012). Stroobant (2008) suggests that some mothers and their children engage in homeschooling as an acceptable and effective solution for students who dislike and avoid school. Nevertheless, many scholars do not recommend homeschooling as a long-term solution because anxiety about returning to school might increase and maintain avoidance and must be evaluated regularly (e.g., Heyne and Sauter, 2013; Ek and Eriksson, 2013). Some researchers also consider homeschooling to be one of many different characteristics of school withdrawal, as homeschooling is a solution sought by some parents to keep their child safe and at arms distance to fear- or harmful situations in school, or because they are critical towards the school, teacher and/or education (Thambirajah et al., 2008; Kearney, 2008).

When a child refuses to attend school, the family is in a very stressful situation, and some parents want homeschooling for their child to reduce these stressors. In response to school refusal, a gradual return to school as quickly as reasonably possible is often recommended. This may be explained by the fact that attending school is related to students’ social, academic and psychological development and is part of socialization into adulthood. These developmental processes might stop or slow down during homeschooling, even though homeschooling might lead to sufficient academic learning. Therefore, school refusers rarely get the opportunity to be home educated (Fortune-Wood, 2007). A study among parents of school refusers in the United Kingdom, found that most of the parents wanted to continue with home education because their child thrived academically and socially from it, but in most cases home education was a last resort (Wray and Thomas, 2013). The findings indicate that the symptoms associated with school refusal mostly disappeared or were reduced when home education was provided. This is in line with findings from Knox (1989), who proposed that home education “virtually eliminates any mental illness” (p. 150) and Fortune-Wood (2007), who found that symptoms “either disappear completely with no aftereffects or decline considerably” (p. 137). Wray and Thomas (2013) examined parental perspectives and concluded that schools and mental health professionals should be required to suggest home education as an alternative to school return and to inform parents about the possibility of home education. Because Wray and Thomas’ study considered parental views only, some important aspects are missing, such as symptoms of mental illness, social functioning outside the home and long-term consequences of these. Although these symptoms disappear or decrease when the stressors are removed, they may increase when students are faced with stressors in school at a later occasion.

Homeschooling and the Vicious Circle

Homeschooling is usually not recommended as a regular intervention for SAP students. When students’ complete schoolwork at home, some might think this situation is a regular intervention and they might easily fall into a negative cycle which is difficult to break (Wijetunge and Lakmini, 2011). The vicious or negative cycle represents the way SAPs are maintained when students’ anxiety about attending school increases over time when the student stays at home having homeschooling (Thambirajah et al., 2008). First this model posits that students lose opportunities to improve peer relations and social functioning and may experience social isolation as a long-term consequence. Second, students’ levels of anxiety and depression may increase when they avoid anxiety-provoking situations, such as situations in school. This may result in an avoidance-reinforcement cycle that becomes self-perpetuating over time. Third, students may fall behind in their schoolwork, which may make the return to school more difficult because it reinforces the fear of failing in school (Thambirajah et al., 2008). Students who are homeschooled may be able to do schoolwork at home without experiencing stress, anxiety, or worries about different situations in school and they may manage to fill the academic gaps and thus reduce their anxiety about falling behind academically, which may make the school return easier. However, attending school is important for more than academic functioning and learning, as the social aspects of school are of importance. The most common concern for homeschooling is socialization, because of isolation and a lack of social interaction due to the SAP the process of socialization and development of social skills might slow down (Romanowski, 2006; Ray, 2013). However, they might participate in activities in their leisure time that benefit their social development and to some extent compensate for the isolation during daytime (Romanowski, 2006). Moreover, because not all social interactions at school are positive (e.g., bully victimization) (Havik et al., 2014; de Carvalho and Skipper, 2019), staying home from school might protect and be a good short-term solution until bullying has stopped.

When schools were closed during the pandemic, all students had homeschooling and they stayed at home most of the time. Social isolation might therefore be a consequence for many students. The degree to which social isolation is true, depends partly on teachers’ facilitation of students’ work in teams or groups or other peer interactions on digital platforms, as well as how they socialize outside of school hours. Moreover, students with SAPs often are vulnerable to social isolation in general, have fewer friends at school or have conflictual relations, social anxiety and/or a lack of social skills (Egger et al., 2003; Heyne et al., 2011; Ingul and Nordahl, 2013; Havik et al., 2014; Blote et al., 2015). Therefore, even if homeschooling increases their academic skills and they perceive to achieve academically for the first time, their anxiety might increase upon school return. The social aspects of school are especially important for older students. Therefore, different aspects must be considered when evaluating homeschooling for students with SAPs, such as academic functioning, social functioning and the development of anxiety and/or depression when students do not physically attend school.

The introduction has shown that there is a disagreement in the literature about homeschooling for SAP students. Some point out that these students should not do schoolwork at home to prevent that an understanding that they can “attend school” from home and thereby increase school absence. However, there is no documentation of academic and social long-term effects of this perspective. Others argue that homeschooling may reduce anxiety associated with attending school, this research is mainly from parental perspectives and there is no documentation of long-term consequences related to socialization and mental health problems. Therefore, the aim of the current study is to investigate how teachers, who have close relations with their students, experience homeschooling for SAP students, during the period of closed schools. The main aim of this explorative study was to investigate teachers’ experiences of homeschooling during COVID-19 for students with SAPs to shed light on the difficult issues involved, such as which effects homeschooling have on academic and social functioning, stress and the further development of symptoms. The research questions were as follows:

RQ1: How are the SAP student relations to school, class and teacher and their characteristics?

RQ2: What are teachers’ perceptions and experience with SAP students’ participation, development, mood and quality of life during homeschooling?

RQ3: What are teachers’ general thoughts and experiences with homeschooling for SAP students?

Methods

Procedure

A questionnaire was developed to address different aspects of homeschooling related to students with SAPs to obtain insight into teachers’ experiences with SAP students. Three teachers participated in a prequestionnaire developed by the authors. These teachers provided constructive feedback to improve the questionnaire. The final version of the questionnaire consisted of open questions and questions where alternatives were provided. The teachers were given information about the aim of the study and that none of their answers would be recognizable, in line with requirements from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data for an anonymous survey. The questionnaire was structured in three parts: the first part included general questions concerning all students and homeschooling, the second part was related to one student with SAPs in the teacher’s class and the third part was about other students with SAPs in the teacher’s class1. This article use teachers responses from the second part of the questionnaire and the main aim was to investigate teachers’ experiences and perceptions of homeschooling during COVID-19 for their student with SAPs, and more specifically to highlighting the three research questions: The SAP students’ relations to school, class and teacher and their characteristics (RQ1); Teachers’ perceptions and experience with SAP students’ participation, development, mood and quality of life during homeschooling (RQ2); Teachers’ general thoughts and experiences with homeschooling for SAP students (RQ3).

All schools closed in Norway on March 13th and they gradually opened from April 27th for students in grade levels 1 to 4 (age 6–9). For 5th to 10th graders (age 10–16), schools gradually reopened from May 11th; however, many schools maintained a combination of education at home and at school until the end of the school year. The present study was conducted in the Norwegian school context, where 10 years of schooling is compulsory and free from the age of 6–16. The Nordic countries aim to build a “Nordic Education Model” comprising a compulsory school system and “A School for All”, indicating that classrooms exhibit variance and diversity in students and that equal opportunities are provided for all students (Blossing et al., 2014).

We sent an e-mail to all schools in Norway on April 24th asking them to distribute the e-mail to all teachers who had students with SAPs in grades 5–10 (schools were still closed for these grade levels at this time). We asked the teachers to answer a web-based questionnaire within the next 2 weeks. The teachers were given information about the aim of the study and the questionnaire on the first page and they were asked to answer the questionnaire anonymously by providing only their gender and the county where they worked. Moreover, they were informed that participation in the study was voluntary. Teachers were encouraged to answer the open-ended questions briefly and concisely and were informed that they could contact one of the researchers via provided e-mail addresses if they had any questions or comments. We received feedback from some schools and teachers that they were not eligible to participate because they had no students with SAPs, worked in a special unit/school and therefore were not able to participate, or had too much work related to distance learning and homeschooling and thus had no time to participate. Some stated that this was not the only inquiry they had received about participation in a research project and hence did not prioritize this study.

We asked the teachers to send their name and e-mail address in a separate e-mail to one of the researchers if they were willing to provide more information later. This e-mail address was not connected to their answers. Eight teachers sent an e-mail and were willing to participate further. This gave us the opportunity to perform member checks or respondent validation. An e-mail with a draft version of the results section (for the qualitative data) was sent to these eight teachers (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). They were asked to read the draft and to provide feedback, to ensure that their experiences were included and recognized. Only one teacher responded and confirmed the findings and opinions. The research steps were transparent regarding the description of the participants, the study procedure, and the analyses. This is important to allow others to judge whether the findings are transferable to other settings. Internal validity or credibility is important in establishing trustworthiness (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Sample

The web based SurveyXact was open for 2 weeks. A total of 238 teachers answered the entire survey, 252 provided partial answered and 422 participated only in the first section of the questionnaire (the general questions) or stated that they had no students with SAPs and were thus removed from the sample. Of the teachers who partially completed the survey, four were removed from the sample (three were from special schools/units and one had no SAP student). The total number of teachers in the sample was 248. Seventy-five percent were female teachers, which reflects the reality of primary and lower secondary schools in Norway, where 75.1 percent of teachers are female (SBSS, 2019). The sample consisted of teachers from all 11 counties of Norway and 8 to 45 teachers participated from each county. We have no other information about the teachers. All schools in Norway were invited based on one criterion: teachers with at least one student in their class with SAPs. Because the sample was not random, we cannot generalize and draw conclusions about all teachers in Norway; thus, the findings might be biased.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire had no link between the answers and computers’ IP addresses, in line with the requirements from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data for an anonymous survey. This research project was not subject to notification since no personal or sensitive personal data were collected and the project did not include any audio, video, or pictures of people. This study is therefore not a subject to General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Analyzing Quantitative Data

The quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS. The data were descriptive and consisted of only one item for each theme. Multiple response analyses (SPSS) were used for the most common reasons for SAPs and how the teachers kept in touch with the student.

Analyzing Qualitative Data

Qualitative data (the open-ended questions of the questionnaire) were analyzed using thematic analysis, which is an accessible and theoretically flexible approach (Aronson, 1994; Braun and Clarke, 2006; Lambert and O’Halloran, 2008). This method is useful when searching for themes or patterns and is more descriptive than interpretive, inspired by Moustakas’ (1994) transcendental or psychological phenomenology. This type of phenomenology focuses on the description of the informants’ experiences (Creswell, 2007). Six steps were followed: familiarizing with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes and producing the article (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The teachers’ comments were carefully discussed, analyzed, and categorized by both researchers.

Results

The results are presented in line with the three research questions: RQ1: How are the SAP students’ relations to school, class and teacher and their characteristics? RQ2: What are teachers’ perceptions and experience with SAP students’ participation, development, mood and quality of life during homeschooling? RQ3: What are teachers’ general thoughts and experiences with homeschooling for SAP students?

Relations to School, Class, and Teacher, and Their Characteristics

Teachers were asked to choose one (1) student in their class when answering the following questions of the survey. A total of 71.8 percent were main teachers and 28.2 percent were subject teachers. The number of lessons per week these teachers taught the student, showed variation from 1 to more than 21 lessons a week.

27.4 percent of the students were in primary school (grade level 5–6) and 72.6 percent were in lower secondary school (grade level 8–10). There were more boys than girls in the sample (107 girls and 141 boys). In primary school, 30 were girls and 33 were boys and in lower secondary school, 77 were girls and 103 were boys. Table 1 show the lessons taught per week and about the SAP student.

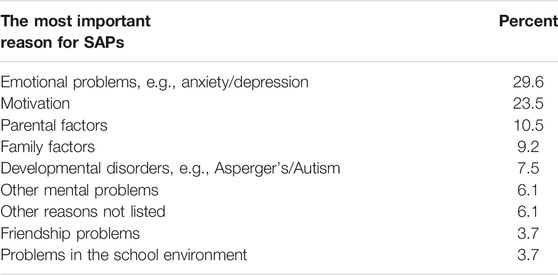

The teachers were asked to choose the definition of SAPs that was most appropriate for their student; A, B, or both (explained above). A total of 33.9 percent chose definition A (“absent from school more than two days in the last two weeks before schools closed with no documented absence”), 21.4 percent chose definition B (“more than 15 percent undocumented absence since Christmas”), and 44.8 percent of the teachers chose both A and B. They were also asked to rate the three most important reasons for their students’ absence (the most important reason, “1”; second most important, “2”; third most important, “3”). They chose between the following reasons: emotional problems (e.g., anxiety/depression), motivation, parental factors, family factors, problems in the school environment, friendship problems, developmental disorders (e.g., Asperger’s/Autism), other mental problems, or other reasons not listed. Some of the teachers rated more than one of the reasons as “1”, “2” and “3”. These teachers might not have been able to choose the most important reason because reasons are often complex, or they did not understand the question correctly. The most important reason (“1”) is shown in ranking order in Table 2. Emotional problems were the most important reason reported by the teachers, while motivation was second most important. The least frequent reasons were friendship problems and problems in the school environment.

The analysis of gender differences for the most important (“1”) reason for SAPs indicated that reasons related to motivation (26.7 percent among boys vs. 19.5 percent among girls) and developmental disorders (10.6 percent among boys vs. 3.8 percent among girls) were more important among boys than girls. Among girls, teachers reported friendship problems (5.3 percent among girls vs. 2.5 percent among boys), problems in the school environment (6 percent among girls vs. 1.9 percent among boys) and emotional problems (36.3 percent among girls vs. 24.8 percent among boys) more often than among boys. Motivational reasons for SAPs were reported as more important by teachers among lower secondary school students, while problems in the school environment were more commonly reported among primary school students. For students who did not attend homeschooling, the most important (“1”) reason for SAPs was related to motivational issues.

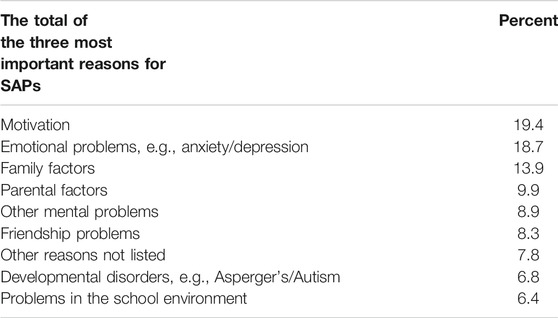

Because SAPs are usually complex and caused by a myriad of reasons, it is relevant to add the three most important reasons for SAPs. The ranking order (the total of 1–3) is shown in Table 3. The most frequently reported reasons were motivation and emotional problems, while problems in the school environmental and developmental disorders were least reported.

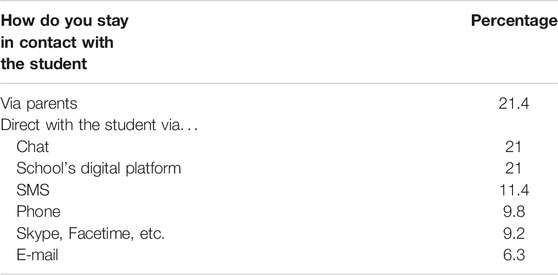

The teachers were also asked how often they kept in touch with the student during homeschooling. The results were “daily or more often”: 29.8 percent; “2–3 times a week”: 38.3 percent; “weekly”: 21.4 percent; and “more seldom”: 10.5 percent. They were also asked how they stayed in touch with the students and they could choose more than one answer. Table 4 shows their responses in ranked order.

Teachers’ Perceptions and Experience With SAP Students’ Participation, Development, Mood, and Quality of Life During Homeschooling?

A total of 79.8 percent of the students participated during homeschooling, while 20.2 percent (50 students) did not. The number of students not participating in homeschooling increased gradually from 5th to 10th grade (0.4 percent in 5th grade and 7.3 percent in 10th grade). Regarding the number of students in each grade level, 8 percent did not participate in 5th grade, 13 percent in 6th grade, 13 percent in 7th grade, 17 percent in 8th grade, 23 percent in 9th grade and 29 percent in 10th grade. There were no gender differences related to participation in homeschooling.

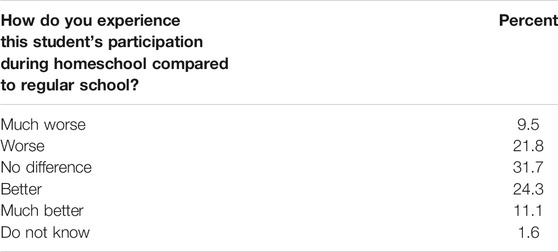

Teachers rated their experiences of their students’ participation in homeschooling compared to regular school attendance. The findings indicate that teachers very slightly perceived better/much better participation during homeschooling (35 percent) than worse/much worse participation (31 percent) (Table 5). There were no significant gender differences; however, teachers reported that more boys than girls participated better/much better during homeschooling (42 percent boys and 27 percent girls).

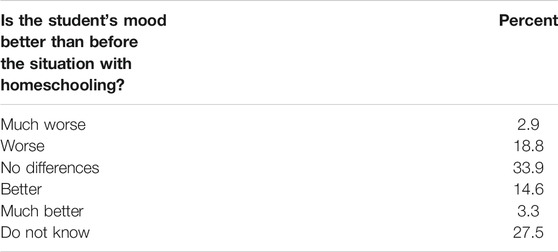

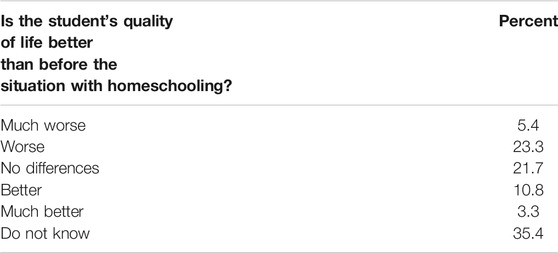

Teachers rated their experiences of the student’s mood and quality of life during homeschooling compared to regular school attendance. The findings indicated that most teachers did not experience any differences, or they did not know. The majority of teachers perceived the student’s mood and, in particular, the student’s quality of life during homeschooling as worse (Tables 6, 7). There were no significant gender differences, however, teachers reported better ratings for boys (32 percent of the boys and 11 percent of the girls had a better mood, and 18 percent of the boys and 9 percent of the girls had better quality of life during homeschooling).

Teachers’ General Thoughts and Experiences With Homeschooling for SAP Students

Forty-nine teachers wrote that they experienced “no changes” during homeschooling for their SAP students. Some of the teachers provided more insight:

“The student does very little while at school and this is the same during homeschooling. The difference is that it is more visible how little he really does now.”

“The student is often tired and sleeps a lot. This did not change.”

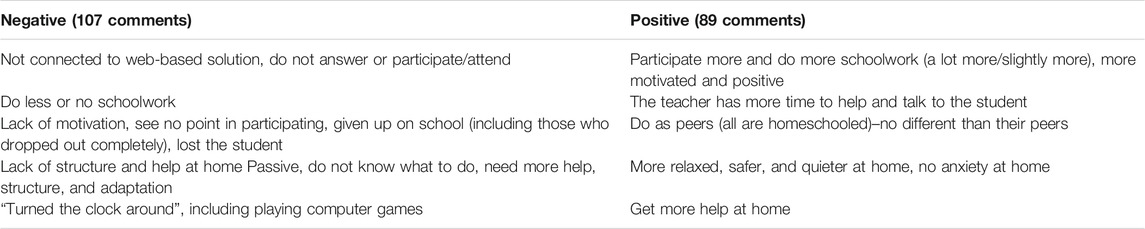

The findings indicated that teachers experienced their students’ participation during homeschooling differently. Teachers had more negative comments (107) than positive comments (89), as described below. See the Appendix for an overview of the results.

Negative comments: Most of the negative comments were that the student was not connected to the web-based solutions, did not answer when the teacher contacted them, or they did not participate. Many teachers commented that the student did less or no schoolwork. Some teachers noted a decrease or lack of motivation and believed that the student saw no point in participating in homeschooling. A few of the teachers wrote that the students dropped out completely (“lost the student”).

Some teachers mentioned that the parents did not manage to follow up with their child or to structure their child’s schooldays or other challenges at home, which the teachers were more able to do at school. Therefore, the student did not know what to do and was passive and needed more help, adaptations, close monitoring, structure, close relations and communication than the teachers were able to give during homeschooling. Issues related to lack of structure at home were that the student “turned around the clock”, was awake during the nights, stayed in bed during the day and did not get up in the morning, often related to computer games (one mentioned reading books):

“It is worse because the student usually attended school every day before homeschooling. The student was truant for some lessons while in school, but it was easier to get in touch with the student. It is now easier for the student to avoid school by not answering digitally or not to do the schoolwork.”

“At school we managed to push and motivate the student, but the parents do not manage this.”

“He does nothing. When he was at school, I could follow him up closely.”

“Relations are much needed, confirmations and encouragement along the way and help to get started. Now he does not get started and gives up quickly.”

“The whole family ‘turned the clock around’ and sleeps during the day.”

Some teachers reported a combination of negative and positive comments, such as that the student participated well in the beginning and reduced effort after the Easter holiday. Moreover, a few teachers commented that the student participated better after a while and after talking to and involving the parents.

Positive comments: Most of the positive comments referred to the student’s greater participation during homeschooling, more schoolwork completed (varying from a lot more to slightly more), or a more positive mood and greater motivation for schoolwork. Moreover, a few teachers commented that the student was not different (did the same) than their peers while they all had homeschooling. Another comment made by a few teachers was that during homeschooling, they had more time to help and talk to the student. Some teachers commented that the student was more relaxed at home, had no anxiety, was quieter and safer at home and received more help at home:

“The parents now understand how little she participated in learning and they are therefore stricter with her at home. Now she has less possibility not to attend or to blame sickness since she is already at home.”

“He now participates in 90 percent of the class’s arrangements, but usually he participates 10–20 percent; the effort is the same, but the attendance is different.”

“He does not physically need to leave the house and I reach him via Teams and it is much easier to keep his motivation and help him to deliver and do the tasks.”

“He does more at home because he has one-to-one help (grandmother).”

Discussion

The discussion part is in line with the three research questions. Fists we discuss; How are the SAP students’ relations to school, class and teacher and their characteristics? (RQ1). Secondly, we discuss; What are teachers’ perceptions and experience with SAP students’ participation, development, mood and quality of life during homeschooling? (RQ2). And last, we discuss; What are teachers’ general thoughts and experiences with homeschooling for SAP students? (RQ3).

Relations to School, Class, and Teacher, and Their Characteristics

Most of the students were in lower secondary school (72.6 percent), which is in line with previous research indicating that preadolescents and adolescents struggle more with SAPs and that these problems are often more complex among older students (e.g., Elliott and Place, 1998; Heyne et al., 2002; Heyne and Sauter, 2013). Furthermore, the results indicated that the number of students with SAPs gradually increased with grade level, from 5.2 percent in 5th grade to 25 percent in 10th grade. The sample might be biased regarding the students’ gender because teachers reported more boys (56.9 percent) than girls. Previous research indicates no difference regarding gender among different types of SAPs (e.g., Egger et al., 2003; Heyne and King, 2004; Reid, 2005; Veenstra et al., 2010).

Most teachers maintained the connection with the student during homeschooling several times a week or daily. Approximately 10 percent had less than weekly contact, while 30 percent had daily or more frequent contact with the student. Approximately 38 percent had contact with their student 2–3 times a week and 21 percent had weekly contact. Furthermore, teachers most frequently kept in touch via the parents, directly with the student via the school’s digital platform or via chat. The frequency of contact might also be related to the teachers’ role; 72 percent were the main teachers and they usually have more frequent contact with the students than subject teachers do. The main teachers also have more responsibility for students and for the school-home communication. Moreover, it is important to note that there were no national guidelines about how to conduct homeschooling or how to stay in touch with the students (e.g., how, or how often).

The student characteristic regarding the most important reason for SAPs, indicated that emotional and motivational problems were the two most important reason reported by these teachers for attendance problems, while friendship problems and problems in the school environment were the least frequent reported reasons. These findings will be included in the next sections of the discussion.

Teachers’ Perceptions and Experience With SAP Students’ Participation, Development, Mood, and Quality of Life During Homeschooling?

The results indicate that 20.2 percent of the students did not participate at all during homeschooling. However, these students might have been absent from school totally or often before schools closed. The number of students who did not participate during homeschooling increased gradually from 5th to 10th grade. One explanation for this decrease with age, might be that adolescents often have more severe problems. In addition, parents might not structure or guide adolescents as they do when children are younger, leading to older students doing their schoolwork with less supervision from parents, making absence easier and more likely. This is related to parental involvement. Parents who are more involved in their children’s education, influence the child’s growth and development and these children do better in school and reduce absenteeism (Sheldon, 2003; Hill and Tyson, 2009; Ingul et al., 2012). However, parents’ involvement decreases with students’ age (Eccles and Harold, 1996). This may be caused by parents’ decreased ability to assist their child with homework in lower secondary school, which is characterized by increased hierarchy and bureaucracy compared with primary school. In addition, students have an increasing need for autonomy as they grow older (e.g., Hill and Tyson, 2009; Hill et al., 2018). Parents’ involvement might be even more important when schools are closed and parents should be more responsible for their children’s education during homeschooling.

Motivational problems were mentioned as one of the most important reason for SAPs by the teachers in this sample and were the most frequent reason for SAP among students who did not participate at all during homeschooling. Some of these students might be motivated to attend school as they might attend school only to meet their friends. Keeping the motivation during homeschooling might be challenging, when there are less interactions with teachers and peers and they receive less direct help and instructions. Moreover, e.g., academic disengagement, lack of concentration and academic ability are associated with truancy (e.g., Malcolm et al., 2003). Therefore, in general, to do schoolwork might be boring and challenging for students with motivational problems. Moreover, some students may lack concentration at school or have behavioral problems or ADHD; they may therefore work better at home, which is quieter and more structured than school. Some students might also request and receive more help and structure from their parents than they do from their teachers because teachers have many students in their class.

The teachers were asked to rate their experiences of the student’s participation during homeschooling compared to regular school attendance. These results indicate that more teachers (24.3%) experienced homeschooling as better than regular school for SAP students. However, it is important to note that many teachers did not notice any differences (31.7%) in the student’s participation during homeschooling, and some (21.8%) reported less participation from the SAP student. The qualitative findings indicate that more teachers had negative than positive comments, but they experienced students’ participation very differently. Moreover, some teachers wrote both positive and negative comments for the student. This might be explained by the fact that homeschooling was delivered differently as there were no guidelines to follow and that some of the tasks were more structured and easier for them to do. Previous research indicates a need for tailored interventions for each SAP student because they have different risk and protective factors (e.g., Kearney and Bates, 2005; Heyne, 2006). This is also relevant for homeschooling as it is for regular schooling. It is important to note that teachers reported that more boys than girls participated better/much better during homeschooling. One explanation for this might be the gender gap in computer science and technology and the finding that girls at an early age have less interest and self-efficacy in technology than boys do (e.g., Master et al., 2017). Because homeschooling is mainly conducted through digital platforms, this might be more motivating for boys than girls.

Teachers’ ratings of students’ mood and quality of life might explain the more holistic experience of homeschooling for these students. More teachers thought that the student’s mood was worse/much worse than better/much better; however, most of them did not notice any difference or did not know. Twice as many teachers stated that the student’s quality of life was worse/much worse than better/much better during homeschooling. However, most of the teachers did not know and some did not notice any differences.

These findings indicate that many teachers perceived homeschooling to be worse than attending school for the SAP students’ quality of life. It is important to have a holistic view and not focus only on students’ participation in school activities since their mental health, well-being and social functioning are important. Many factors may contribute to students’ functioning while at home, such as parental, family, peer/friend, and individual factors. Moreover, parents are an important source for their children’s mood and quality of life and they often have more information about their children than teachers do. A study that examined parents’ perspective indicated that well-being was improved in the short and long term when school refusers had homeschooling (Wray and Thomas, 2013). Therefore, teachers and parents might not agree in all aspects of homeschooling. Previous studies indicate that parents are generally more positive about homeschooling than the teachers in the current study. Homeschooling is by most scholars not recommended as a regular intervention for SAP students, because the students easily fall into a negative or vicious circle which is difficult to break (Thambirajah et al., 2008). All the aspects of the cycle might not be in the parents’ minds when they see homeschooling as a good alternative, they are maybe more here-and-now noticing a decrease in anxiety levels and increase in quality of life for their child. Additionally, their child might be doing more schoolwork than before, all in all appearing to be a positive development compared to the experience of stress, anxiety, or worries they experienced while their child was at school. But the parents might not be aware of the potential long-term consequences and functional impairment associated with SAPs. However, if the students perceive to be on top academically during homeschooling, it might be easier to return to school as they do not perceive to be academically behind their peers, maybe for the first time. But in line with the negative or vicious circle, absence might be maintained as students’ anxiety about attending school increases in the long run when the student stays at home (Thambirajah et al., 2008). This might be further escalated as homeschooled students often experience a lack of socialization (lack of social interaction and development of social skills), which is the most common and disturbing concern for homeschooling (Romanowski, 2006; Ray, 2013).

Teachers’ General Thoughts and Experiences With Homeschooling for SAP Students

The most common negative comments from teachers were that the students did not connect to the web-based solutions or did not answer the teacher and that the student participated less or did not do schoolwork. This might be related to some of the other comments of the teachers, such as a lack of structure and help at home, the student’s need for close monitoring, help and adaptation, a lack of motivation to participate or do schoolwork and the fact that some students “turned the clock around” and slept during the school day. Individual work at home might be challenging for many students because they need help structuring their school day at home, which might be why some dropped out completely or did not participate. Since motivational issues were one of the most common reasons for SAPs, these students might need closer monitoring and adaptation than the teacher was able to provide during homeschooling; this might be further reinforced if parents are not involved in their child’s schoolwork. This might indicate that homeschooling is a challenge if the student has motivational issues in general. Other activities might be more appealing, such as playing computer games or sleeping during the day.

Some teachers mentioned that homeschooling was initially positive for the student but became negative and that the students reduced their effort after the Easter holiday, approximately 1 month after homeschooling started. This might be because the students were tired of homeschooling and it became more difficult to keep up with the structure and complete schoolwork at home and mostly alone. Another reason could be a lack of variation during and between schooldays. Students’ reduced effort might also be explained by a new interest; it might initially be exciting not to attend school and do schoolwork at home. Moreover, it might be more difficult to connect after the Easter holiday, which lasts for 10 days in Norway. However, a few teachers mentioned the opposite: it took a while until the student was connected and participated and then the student often did so in close cooperation with the parents. This indicates the need for parental involvement in children’s schoolwork during homeschooling and suggests that school-home cooperation is an important aspect during homeschooling.

Teachers’ positive comments were the opposite of the negative comments. Most of the comments were that students participated more, did more schoolwork, were more positive and motivated and asked for more help from the teacher. This might be explained by the fact that some SAP students fear situations or activities in school (e.g., Kearney, 2008) and might be related to emotional problems (e.g., anxiety/depression) which were the most frequent teachers reported reason for SAP for these students. Moreover, some teachers perceived the student to be safer and more relaxed, that it was quieter at home and that the student had no anxiety while doing schoolwork at home. This is in line with previous findings from parental views regarding home education (Knox, 1989; Fortune-Wood, 2007; Wray and Thomas, 2013). If attending school creates fear and being at school means being afraid most of the time, it is understandable that some students have less energy, motivation and concentration at school and for learning. Fear and anxiety tend to increase and expand with avoidance; thus, homeschooling is not a good solution in the long run. Moreover, students might fall into the negative or vicious circle, which might be difficult to break (described above) (e.g., Thambirajah et al., 2008). This might result in prolonged absence when schools reopen, Therefore, a gradual school return is usually warranted. However, in line with a study by Maeda and Heyne (2019), their findings indicate that rapid school return is effective for adolescent school refusers. Moreover, if a student has anxiety or fear about attending school, standard treatments are relaxation training, gradual reintroduction and exposure to school and cognitive behavioral therapy and/or family therapy (e.g., King et al., 2000).

Another explanation for teachers’ positive experiences of homeschooling might be that some students received more help at home, as indicated by a few teachers. This might be related to parents’ involvement in their child’s schoolwork at home (e.g., Hill and Tyson, 2009). Moreover, some parents worked at home during the pandemic, lost their job or were temporarily laid off and therefore had more possibilities to help and be involved in their children’s schoolwork. A few teachers commented that they had more time to help and talk to their student during homeschooling, indicating that some teachers perceived that they were more able to help and structure homeschooling for students than when school was running as normal.

Another positive comment from a few teachers was that during homeschooling, the students were the same as their peers because they all had homeschooling. Most students want to be like the others and not being different from others is important for school refusers from their parents’ views (Havik et al., 2014).

Strengths and Limitations

One strength of the current study is that it was conducted while schools from 5th to 10th grade level still were closed and all students were given homeschooling. This provides ecological validity because the answers were based on the teachers’ recent experiences. Another strength is that a few teachers were asked to read the draft and provide feedback to ensure that their experiences were included and recognized. Because only one teacher answered and confirmed the findings, we do not know whether the other teachers agreed with the draft, making the internal validity somewhat uncertain.

Another strength is that the teachers had experiences with SAP students based on a previously mentioned common definition of SAPs. However, one limitation is that the definition is wide and covers many types of SAPs. This might explain the variation in teachers’ answers, suggesting that what works for one type of SAP might be worse or unhelpful for another type. Teachers were asked to rank the three most important reasons for their students’ SAPs. The main reasons reported by these teachers were students’ emotional problems (e.g., anxiety and/or depression) and motivation, while school environmental factors and friendship problems were least reported. In a study among Swedish teachers, teachers perceived family factors to be the most important reasons for school absenteeism (Gren-Landell et al., 2015). Moreover, many parents of school refusers feel blamed for their child’s problems by the school (Havik et al., 2014) and students, parents and schools blame each other for truancy (e.g., Kinder et al., 1996; Kinder and Wilkin, 1998; Malcolm et al., 2003). Reid (2002) noted that schools might blame parents for absence so that schools have no responsibility for the absent student. Because the reasons reported by the teachers in this study might not be correct or precise, we did not analyze the data based on the reasons for SAPs.

Another limitation of this study is that only teachers participated, and other perspectives, such as those of parents and students themselves, should be included. However, a strength is the number of participating teachers. Because school closure was a first-time situation, it was not convenient to use preestablished categories. Moreover, the aim was to obtain in-depth insight into teachers’ experiences with homeschooling. By using preestablished categories, we might have lost some of the rich information from the teachers.

Some of the teachers were subject teachers (28.2 percent), which might indicate that they did not know the student as well as the main teachers did, as they may not have a holistic understanding of the SAP student. In addition, the number of lessons they taught the student according to the timetable varied, which might indicate that they did not know the student or that they taught several subjects and lessons in the same class. However, as many as 66 percent of teachers taught SAP students more than 5 h each week.

It is important to note that this study was conducted after only a few weeks of closure. If a similar study was done among teachers at schools that were closed or partly closed for a longer time, or after schools reopened, the results may have been different.

Practical Implications and Conclusion

Homeschooling may have been provided differently among schools and teachers because schools were closed for the first time in history and no national guidelines existed. The results of this study indicate that homeschooling might not be a good solution for all students with SAPs as seen from teachers’ perspectives. Twenty percent of the students in this sample did not participate at all and this number increased from 5th to 10th grade level. Moreover, other SAP students participated but did not do schoolwork, indicating that homeschooling might be counterproductive for some. Findings also indicate that homeschooling is less suited for older students, which might be related to less parental involvement, a need for a stronger cooperation between school and home during homeschooling and the need for schools to inform and instruct parents on how to help their child. Moreover, cooperation between school and home might be even more important during homeschooling than during regular schooling. This was described by a few of the teachers in situations where the student did not work until the teacher contacted the parents. Some students received extensive help and structure at home, while others did not.

Because homeschooling does not fit all SAP students, tailored assessment and interventions for each SAP student are warranted, because they have different challenges and resources and schooldays and schoolwork are structured differently. The in-depth answers from teachers were slightly more negative than the quantitative data. However, when students’ mood and quality of life were included, the qualitative and quantitative data were more aligned. This indicates that other factors than schoolwork are important for students’ well-being; home-related and individual factors are also important when doing schoolwork at home. Moreover, teachers might not be able to follow up students as closely as necessary when they are not physically together with their students.

Based on the reasons for SAPs, the findings indicate that homeschooling might work differently for different reasons for SAP students. Motivation and emotional problems (e.g., anxiety/depression) were most frequently reported reasons for SAP by teachers in this study. When students have motivational issues related to schoolwork, it might be difficult to get started with schoolwork at home. This might be even more difficult for older students, who often receive less help and structure from their parents. The findings also indicated that students who did not participate in homeschooling had more motivational issues than those who participated. When students are absent from school due to a lack of motivation, homeschooling might not be a good intervention. For other students, homeschooling might be a relief for emotional symptoms, but this might be a mixed blessing because avoidance rarely results in symptom relief in the long run. However, it might indicate that gradual return and a slow increase in attendance are needed upon returning to school, as this might reduce the risk of students feeling overloaded and overwhelmed upon returning, which may make them unable to cope.

The study also indicates that teachers did not recognize school environmental problems or friendship problems as important reasons for SAPs for the students. This is an important finding as these factors are closely associated with SAPs. When teachers do not recognize school-related factors for SAPs, such as how students perceive their school environment and peer relations, they might not be able to identify and adapt school factors for the student, even when teachers are in a position to do so. However, teachers reported school environmental factors and peer problems, in addition to emotional problems, to be more important reasons for SAPs for girls than for boys, while motivation and developmental disorders were more important for boys than for girls. These findings indicate that girls and boys might need different interventions. However, we believe that assessing reasons for SAPs is more important than the students’ gender.

Homeschooling was perceived differently by teachers for their SAP students and therefore, homeschooling should not be recommended as an intervention for all SAP students. For some, homeschooling is positive because it reduces symptoms of emotional difficulties in the short run, makes it easier to concentrate and increases their quality of life. This could indicate that homeschooling should be recommended for this group of students. However, socialization is also an important part of attending school and emotional difficulties often decrease when students are absent from school for a prolonged period. Therefore, we do not recommend homeschooling as a permanent intervention for students with SAPs. Nevertheless, these findings provide input on how school life can be adapted (e.g., small groups for students with emotional difficulties, fewer stressors and more specific practical tasks for students with concentration difficulties), which will be investigated in more detail in another article. The findings also indicate that all individual and contextual factors must determine the final intervention for each SAP student, including homeschooling as an intervention.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

The first draft of the manuscript was written by TH, and JI contributed feedback and comments on all versions. Both authors analysed the data, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, orclaim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1The questionnaire is in Norwegian and is available by contacting the corresponding author.

References

Bernstein, G. A., Garfinkel, B. D., and Borchardt, C. M. (1990). Comparative Studies of Pharmacotherapy for School Refusal. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 29 (5), 773–781. doi:10.1097/00004583-199009000-00016

Blagg, N. R., and Yule, W. (1984). The Behavioural Treatment of School Refusal-Aa Comparative Study. Behav. Res. Ther. 22 (2), 119–127. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(84)90100-1

Blossing, U., Imsen, G., and Moos, L. (2014). The Nordic Education Model. “A School for All” Encounters Neo-liberal Policy, Policy Implications of Research in Education. New York, United States: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7125-3

Blöte, A. W., Miers, A. C., Heyne, D. A., and Westenberg, P. M. (2015). “Social Anxiety and the School Environment of Adolescents,” in Social Anxiety and Phobia in Adolescents. Development, Manifestation and Intervention Strategies. Editors K. Ranta, A. La Greca, L. J. Garcia-Lopez, and M. Marttunen (New York, United States: Springer International), 151–181. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-16703-9_7

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3 (2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Carroll, H. C. M. (1996). “The Role of the Educational Psychologist in Dealing with Pupil Absenteeism,” in Unwillingly to School. Editors I. Berg, and J. P. Nursten (London United Kingdom: Gaskell).

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative Inquiry And Research Design: Chosing Among Five Approaches. 2nd ed. California, United States: Sage Publications.

Dalziel, D., and Henthorne, K. (2005). Parents'/carers' Attitudes towards School Attendance. London: DfES Publications.

de Carvalho, E., and Skipper, Y. (2019). We're Not Just Sat at home in Our Pyjamas!": a Thematic Analysis of the Social Lives of home Educated Adolescents in the UK. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 34, 501–516. doi:10.1007/s10212-018-0398-5

Department for Education (2014). The Right to Education in Child Welfare and Health Institutions, and at home in the Event of Long-Term Illness Udir-6-2014. Available at: https://www.udir.no/regelverkstolkninger/opplaring/Elever-med-sarskilte-behov/Udir-6-2014/5/.

Eccles, J. S., and Harold, R. D. (1996). “Family Involvement in Children’s and Adolescents’ Schooling,” in Family-School Links: How Do They Affect Educational Outcomes. Editors A. Booth, and J. F. Dunn (Milton Park, United Kingdom: Routledge), 3–34.

Egger, H. L., Costello, E. J., and Angold, A. (2003). School Refusal and Psychiatric Disorders: a Community Study. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 42 (7), 797–807. doi:10.1097/01.CHI.0000046865.56865.79

Ek, H., and Eriksson, R. (2013). Psychological Factors behind Truancy, School Phobia, and School Refusal: A Literature Study. Child. Fam. Behav. Ther. 35 (3), 228–248. doi:10.1080/07317107.2013.818899

Elliott, J. G., and Place, M. (1998). Children in Difficulty: A Guide to Understanding and Helping. Milton Park, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Evans, I., Okifuji, A., Engler, L., Bromley, K., and Tishelman, A. (1993). Home-school Communication in the Treatment of Childhood Behavior Problems. Wcfb 15 (2), 37–60. doi:10.1300/J019v15n02_03

Fortune-Wood, M. (2007). Can't Go Won't Go: An Alternative Approach to School Refusal. Cardiff, United Kingdom: Cinnamon Press.

Gren-Landell, M., Ekerfelt Allvin, C., Bradley, M., Andersson, M., and Andersson, G. (2015). Teachers' Views on Risk Factors for Problematic School Absenteeism in Swedish Primary School Students. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 31 (4), 412–423. doi:10.1080/02667363.2015.1086726

Havik, T., and Ingul, J. M. (2021). How to Understand School Refusal. Front. Educ. doi:10.3389/feduc.2021.715177

Havik, T., Bru, E., and Ertesvåg, S. K. (2014). Parental Perspectives of the Role of School Factors in School Refusal. Emotional Behav. Difficulties 19 (2), 131–153. doi:10.1080/13632752.2013.816199

Heyne, D., Sauter, F. M., Van Widenfelt, B. M., Vermeiren, R., and Westenberg, P. M. (2011). School Refusal and Anxiety in Adolescence: Non-randomized Trial of a Developmentally Sensitive Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. J. Anxiety Disord. 25, 870–878. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.04.006

Heyne, D., Gren-Landell, M., Melvin, G., and Gentle-Genitty, C. (2019). Differentiation between School Attendance Problems: Why and How? Cogn. Behav. Pract. 26 (1), 8–34. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.03.006

Heyne, D., and King, N. J. (2004). “Treatment of School Refusal,” in Handbook of Interventions that Work with Children and Adolescents: Prevention and Treatment. Editors P. M. Barrett, and T. H. Ollendick (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons), 243–272.

Heyne, D., Rollings, S., King, N. J., and Tonge, B. (2002). School Refusal. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell.

Heyne, D., and Sauter, F. M. (2013). “School Refusal,” in The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of the Treatment of Childhood and Adolescent Anxiety. Editors C. Essau, and T. H. Ollendick (Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley), 471–518.

Heyne, D. (2006). “School Refusal,” in Practitioner’s Guide to Evidence-Based Psychotherapy. Editors J. E. Fisher, and W. T. O’Donohue (New York, United States: Springer), 600–619. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-28370-8_60

Hill, N. E., and Tyson, D. F. (2009). Parental Involvement in Middle School: a Meta-Analytic Assessment of the Strategies that Promote Achievement. Dev. Psychol. 45 (3), 740–763. doi:10.1037/a0015362

Hill, N. E., Witherspoon, D. P., and Bartz, D. (2018). Parental Involvement in Education during Middle School: Perspectives of Ethnically Diverse Parents, Teachers, and Students. J. Educ. Res. 111 (1), 12–27. doi:10.1080/00220671.2016.1190910

Ingul, J. M., Klöckner, C. A., Silverman, W. K., and Nordahl, H. M. (2012). Adolescent School Absenteeism: Modelling Social and Individual Risk Factors. Child. Adolesc. Ment. Health 17 (2), 93–100. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00615.x

Ingul, J. M., and Nordahl, H. M. (2013). Anxiety as a Risk Factor for School Absenteeism: what Differentiates Anxious School Attenders from Non-attenders? Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 12 (25), 25–29. doi:10.1186/1744-859X-12-25

INSA (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on School Attendance Problems: Our Response. Available at: https://insa.network/images/pdf/2020-04-07_INSA_RESPONSE_COVID-19.pdf.

Isenberg, E. J. (2007). What Have We Learned about Homeschooling? Peabody J. Education 82 (2-3), 387–409. doi:10.1080/01619560701312996

Kearney, C. A. (2007). Forms and Functions of School Refusal Behavior in Youth: an Empirical Analysis of Absenteeism Severity. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 48 (1), 53–61. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01634.x

Kearney, C. A., and Silverman, W. K. (1990). A Preliminary Analysis of a Functional Model of Assessment and Treatment for School Refusal Behavior. Behav. Modif 14 (3), 340–366. doi:10.1177/01454455900143007

Kearney, C. A. (2008). An Interdisciplinary Model of School Absenteeism in Youth to Inform Professional Practice and Public Policy. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 20, 257–282. doi:10.1007/s10648-008-9078-3

Kearney, C. A., and Bates, M. (2005). Addressing School Refusal Behavior: Suggestions for Frontline Professionals. Child. Schools 27 (4), 207–216. doi:10.1093/cs/27.4.207

Kearney, C. A., and Beasley, J. F. (1994). The Clinical Treatment of School Refusal Behavior: A Survey of Referral and Practice Characteristics. Psychol. Schools 31 (2), 128–132. doi:10.1002/1520-6807(199404)31:2%3C128:AID-PITS2310310207%3E3.0.CO;2-5

Kearney, C. A. (2016). Managing School Absenteeism at Multiple Tiers: An Evidence-Based and Practical Guide for Professionals. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Kinder, K., Wakefield, A., and Wilkin, A. (1996). Talking Back: Pupil Views on Dissatisfaction. Slough, United Kingdom: National Foundation for Educational Research.

Kinder, K., and Wilkin, A. (1998). With All Respect: Reviewing Disaffection Strategies. Slough, United Kingdom: National Foundation for Educational Research.

King, N., Tonge, B. J., Heyne, D., and Ollendick, T. H. (2000). Research on the Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of School Refusal: A Review and Recommendations. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 20 (4), 495–507. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00039-2

Knox, P. (1989). Home-based Education: an Alternative Approach to 'school Phobia'. Educ. Rev. 41 (2), 143–151. doi:10.1080/0013191890410206

Lambert, S., and O'Halloran, E. (2008). Deductive Thematic Analysis of a Female Paedophilia Website. Psychiatry Psychol. L. 15 (2), 284–300. doi:10.1080/13218710802014469

Lauchlan, F. (2003). Responding to Chronic Non-attendance: a Review of Intervention Approaches. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 19 (2), 133–146. doi:10.1080/02667360303236

Lincoln, Y. S., and Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. California, United States: Sage Publications.

Maeda, N., and Heyne, D. (2019). Rapid Return for School Refusal: A School-Based Approach Applied with Japanese Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 10, 2862. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02862

Malcolm, H., Wilson, V., Davidson, J., and Kirk, S. (2003). Absence from School: A Study of its Causes and Effects in Seven LEAs. NFER/DfES. The SCRE Centre. Glasgow, United Kingdom: University of Glasgow.

Master, A., Cheryan, S., Moscatelli, A., and Meltzoff, A. N. (2017). Programming Experience Promotes Higher STEM Motivation Among First-Grade Girls. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 160, 92–106. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2017.03.013

Mcshane, G., Walter, G., and Rey, J. M. (2004). Functional Outcome of Adolescents with ‘School Refusal’. Clin. Child Psychol. P. 9 (1), 53–60. doi:10.1177/1359104504039172

Melvin, G. A., and Tonge, B. J. (2012). “School Refusal,” in Handbook of Evidence‐based Practice in Clinical Psychology. Editors P. Sturmey, and M. Hersen (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons). doi:10.1002/9781118156391.ebcp001024

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological Research Methods. California, United States: Sage Publications.

NCES (2009). 1.5 Million Homeschooled Students in the United States in 2007. Washington D C, United States: Issue Brief from Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. (NCES 2009–030). Available at: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2009/2009030.pdf.

Place, M., Hulsmeier, J., Davis, S., and Taylor, E. (2000). School Refusal: A Changing Problem Which Requires a Change of Approach? Clin. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 5 (3), 345–355. doi:10.1177/1359104500005003005

Ray, B. D. (2013). Homeschooling Associated with Beneficial Learner and Societal Outcomes but Educators Do Not Promote it. Peabody J. Education 88 (3), 324–341. doi:10.1080/0161956X.2013.798508

Reid, K. (2008). The Causes of Non-attendance: an Empirical Study. Educ. Rev. 60 (4), 345–357. doi:10.1080/00131910802393381

Reid, K. (2005). The Causes, Views and Traits of School Absenteeism and Truancy. Res. Education 74, 59–82. doi:10.7227/RIE.74.6

Romanowski, M. H. (2006). Revisiting the Common Myths about Homeschooling. The Clearing House: A J. Educ. Strateg. Issues Ideas 79 (3), 125–129. doi:10.3200/TCHS.79.3.125-129

SBSS (Statistics Norway) (2019). Pupils in Primary School. Available at: https://www.ssb.no/statbank/table/12282/tableViewLayout1/.

Sheldon, S. B. (2003). Linking School–Family–Community Partnerships in Urban Elementary Schools to Student Achievement on State Tests. Urban Rev. 35 (2), 149–165. doi:10.1023/A:1023713829693

Staufenberg, J. (2017). Home Education Doubles, with Schools Left to ‘pick up Pieces’ when it Fails. Schools Week. Available at: https://schoolsweek.co.uk/home-education-doubles-with-schools-left-to-pick-up-pieces-when-it-fails/.

Stroobant, E. (2008). “Dancing to the Music of Your Heart: home Schooling the School Resistant Child. A Constructivist Account of School Refusal,”. Doctoral thesis (The University of Auckland¸ Auckland, New Zealand). Availabe at: https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/2292/2429/02whole.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y.

Stroobant, E., and Jones, A. (2006). School Refuser Child Identities. Discourse: Stud. Cult. Polit. Education 27 (2), 209–223. doi:10.1080/01596300600676169

Thambirajah, M. S., Granduson, K. J., and De-Hayes, L. (2008). Understanding School Refusal. A Handbook for Professionals in Education, Health and Social Care. London, United Kingdom: Jessica Kingsley.

Veenstra, R., Lindenberg, S., Tinga, F., and Ormel, J. (2010). Truancy in Late Elementary and Early Secondary Education: The Influence of Social Bonds and Self-Control- the TRAILS Study. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 34 (4), 302–310. doi:10.1177/0165025409347987

Wijetunge, G. S., and Lakmini, W. D. (2011). School Refusal in Children and Adolescents. Sri Lanka J. Child. Health 40 (3), 128–131. doi:10.4038/sljch.v40i3.3511

Wray, A., and Thomas, A. (2013). School Refusal and home Education. J. Unschooling Altern. Learn. 7 (13), 64–85.

Appendix Teachers’ experiences of the SAP student.

Keywords: homeschooling, COVID - 19, scool attendance problems, teachers’ experiences, explorative study

Citation: Havik T and Ingul J (2021) Does Homeschooling Fit Students With School Attendance Problems? Exploring Teachers’ Experiences During COVID-19. Front. Educ. 6:720014. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.720014

Received: 03 June 2021; Accepted: 05 October 2021;

Published: 26 October 2021.

Edited by:

Shaljan Areepattamannil, Emirates College for Advanced Education, United Arab EmiratesReviewed by:

Tasneem Amatullah, Emirates College for Advanced Education, United Arab EmiratesElizabeth Bartholet, Harvard Law School, Cambridge, United States

Copyright © 2021 Havik and Ingul. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Trude Havik, dHJ1ZGUuaGF2aWtAdWlzLm5vJiN4MDIwMGE7

Trude Havik

Trude Havik Jo Magne Ingul

Jo Magne Ingul