- Brock University, St. Catharines, ON, Canada

This paper captures the intimate, intensely lived, and storied experiences during the pandemic, on teachers’ narratives of teaching and education. The narratives illuminate deep knowledge and insight into pre-existing school systemic barriers prior to the pandemic, and how those same barriers are magnified during the pandemic in what has become a global watershed moment that calls for equity reform in school systems. A narrative theoretical framework is used, as well as an ethic of care framework that informs the study. Issues of poverty, diversity, equity, and inclusion are illuminated, with further focus on topics of technology access, streaming, resilience, and teacher-student identity and relationship. Recommendations to eradicate systemic barriers in schools are explored, highlighting suggestions for equity reform in areas that include: enhancing professional practice; building a school culture of care, and; developing partnerships and relationships.

Introduction

In the wake of our worldwide pandemic and its unexpected impact on educational policy, many diverse student populations face unprecedented and formidable challenges in their educational pathways. Such challenges stem from deeply rooted systemic barriers that have existed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which include but are not limited to: accessibility to educational resources and technology; access to Internet service and bandwidth necessary for remote (online) learning; the streaming of children and youth into non-academic pathways, and; students’ inability to succeed due to systemic barriers and implicit discrimination in school systems and society at large (Ciuffetelli Parker, 2015, Ciuffetelli Parker, 2019; DDSB, 2019; People for Education, 2020).

This paper captures the intimate, intensely lived, and storied experiences during the pandemic, on teachers’ narratives of teaching and education. The narratives illuminate deep knowledge and insight into pre-existing school systemic barriers prior to the pandemic, and how those same barriers are magnified during the pandemic in what has become a global watershed moment that calls for equity reform in school systems. A narrative theoretical framework is used, as well as an ethic of care framework that informs the study. Issues of poverty, diversity, equity, and inclusion are illuminated, with further focus on topics of technology access, streaming, resilience, and teacher-student identity and relationship. Recommendations to eradicate systemic barriers in schools are explored, highlighting suggestions for equity reform in areas that include: enhancing professional practice; building a school culture of care, and; developing partnerships and relationships.

Literature Review

In order to contextualize the present study, our review of the existing literature is organized according to four main themes: 1) Technology and access to technology; 2) Systemic barriers in school systems; 3) Resilience and marginalized students; 4) Reform practices and policies in school systems. The overarching umbrella where these themes are situated, originates from the longitudinal research program on poverty and schooling (Ciuffetelli Parker and Flessa, 2011; Ciuffetelli Parker, 2013; Ciuffetelli Parker, 2015; Ciuffetelli Parker, 2017; Ciuffetelli Parker, 2019).

In accordance with findings from the principal investigator’s larger research project, which closely examined poverty and its intersectionality with schooling, mental health, and diverse student populations (Ciuffetelli Parker, 2018; Ciuffetelli Parker, 2019; Ciuffetelli Parker and Ankomah, 2019; Craig et al., 2020), children and youth living in poverty have been significantly impacted throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite policies, declarations, and goals set in place, Canada still faces dire issues of youth and family poverty that sustain conditions of social and economic marginalization. The pandemic, unfortunately, has magnified exponentially pre-existing disparities for diverse student populations living in poverty. Data from Campaign 2000 (2020a) report card on child and family poverty in Canada calculates that more than 1.3 million children (i.e., approximately one in five children in families) lived in poverty before the 2020 global pandemic ensued here in Canada. The report card also indicates that First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples, children with disabilities, children from female led lone parent families, racialized children, and immigrant children are notable groups who are overrepresented in rates of poverty (Campaign 2000, 2020a). For instance, within the province of Ontario, one in seven families live in poverty. However, this number increases to one in three for lone parent families who are living in poverty (Campaign 2000, 2020b). Nonetheless, a recurring theme prevails: “No matter how you measure it, children in poverty are falling through the cracks” (Campaign 2000, 2020b, p. 1). Further, issues and barriers related to accessibility can significantly contribute to higher rates of poverty among children and youth in vulnerable families, including children in women-led households (especially those who have fled violence), undocumented children, children of migrant workers, and First Nations children/youth living on reserve (Campaign 2000, 2020b). While the data from the 2020 report card illustrates that urgent, thoughtful, and timely action is needed to eradicate dire poverty rates and income inequities across Canada, the onset of COVID-19 has magnified pre-existing disparities, inequities, and systemic barriers within school systems and society at large. This literature review details such barriers below.

Technology and Access to Technology

On average across OECD countries, PISA (2018; as cited in OECD, 2020c) found that 9% of 15-year-old students do not have access to a quiet learning environment within their homes. In this case, despite having access to quality Internet connection, some vulnerable children and youth are likely to appear as the most represented among those who do not have a proper, quiet, and equipped learning environment to complete school work and study in their homes. For instance, the OECD (2020a) Policy Brief reports that immigrant and Roma students who live in crowded households or camps may not only find it challenging to locate a quiet space to study, but are also more likely to lack motivation. Given the challenges of providing each student with a quiet and equipped work space, parental, familial, and peer support (for the purpose of virtual learning) has become an identified barrier to inclusive and quality remote learning (OECD, 2020a). Moreover, not all children and youth receive the same amount of parental and familial support when navigating the complexities of virtual learning in their respective home environment. The OECD (2020a) provides an example of how this particular inequity continues to pose a significant barrier, as evidenced in a study conducted within the Netherlands during school closures:

…even if nearly all parents stressed the importance of helping their children in keeping up with their study at home, students from advantaged socio-economic background received more parental support and had access to more educational resources than those from disadvantaged backgrounds. Some parents, such as parents of immigrant and refugee students, may not be able to work from home (due to their over-representation among those considered essential workers) or support their children with home-schooling due to their limited education and/or lack of proficiency in the language of instruction. In this case, the continuity of limited physical educational services and the availability of multi-languages resources, respecting hygiene and social distancing, can be key for many students (Bol, 2020; as cited in OECD, 2020a, p. 6).

As exemplified in the above excerpt, COVID-19 has exacerbated systemic barriers currently faced by marginalized, oppressed, and low-income children and youth.

In relation to COVID-19, the pandemic has shone an especially bright spotlight on a systemic issue that has existed in Canadian communities and school systems prior to COVID- 19—digital inequity (i.e., the issue of access to technology, especially that of Internet and phone connectivity). The rapid and unprecedented changes in both the educational and healthcare landscapes demonstrate that the lack of access to a digital device has become a further impediment to equity in education, student success, and achieving good mental health. Teachers in Ontario’s Northern school boards, for example, voiced that the region’s vast geography and sparse population presented a series of challenges that were not considered in Southern parts of the province (Thompson and McQuigge, 2020). Thompson and McQuigge (2020) article entitled, “Northern Ontario schools face additional challenges for reopening—and staying closed,” highlighted how the school boards’ process of developing COVID-19 contingency plans did not take into account the lack of resources in the far North. More problematic, barriers to remote learning in Northern Ontario were reported as significantly greater as many do not have Wi-Fi in their homes, albeit some residents who pay exorbitant fees to obtain Wi-Fi for the purpose of distance learning (Thompson and McQuigge, 2020).

Students profoundly experience isolation when their school doors are closed in an attempt to contain COVID-19 according to government restrictions. UNESCO (2019; as cited in OECD, 2020a) calculates that “more than 188 countries, encompassing around 91% of enrolled learners worldwide, closed their schools to try to contain the spread of the virus” (p. 2). When required to immediately pivot to virtual pandemic teaching-learning, a number of countries and school systems demonstrated a seemingly universal response to school closures with the creation of online teaching-learning platforms. Such platforms have been imperative to support teaching staff, students, and families when learning remotely. Students’ equitable access to information and communication technologies, especially digital devices, learning resources, and quality Internet access, notably varied greatly across countries. In response to digital inequities and accessibility issues, several civil society organizations and governments provided minoritized students with devices, such as computers and tablets as well as Internet access, or organized their teaching through mediums ranging from television or phones (OECD, 2020a). There have been several significant developments and partnerships with national educational media and free online learning resources to reach all learners of various circumstances and SES. For instance, students in New Zealand were offered a new online learning space, learning packs in hard copy format, and television programs for the purpose of effective remote learning (New Zealand Government, 2020; as cited in OECD, 2020a). The government of Colombia also developed an online platform that houses more than 80,000 pedagogical resources that are free of access for low-income families and, when lacking Internet connectivity, users are still able to access the online platform without having to consume any of their mobile data (Government of Colombia, 2020; as cited in OECD, 2020a). In this manner, the pandemic highlighted how equitable access to Internet and telecommunication indirectly acts as a social determinant of health (Somers et al., 2020) and is thus an integral component to ensuring equity in education for all students.

Virtual Learning for Vulnerable Students

In the report entitled, Technology in Schools–A Tool and a Strategy, People for Education (2020) write,

An undeniable reality has emerged in the COVID-19 pandemic: Technology can be a very useful tool in education, but it cannot act as a replacement for the rich learning and human development that happens in the myriad face-to-face settings and relationships that exist in schools (p. 1).

While teaching staff, students, and communities work to navigate a COVID-19 climate with an intermix of in-class and virtual teaching-learning, the existing literature reaffirms how the pandemic has amplified pre-existing social inequities and barriers that have “always been there,” most notably: students’ access to technology; the impact of poverty; discrimination, and; families’ social capital, as it relates to varied family resources to support students outside of the classroom setting and in the home, for example (People for Education, 2020).

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) November 2020 Policy Brief entitled, The Impact of COVID-19 on Student Equity and Inclusion: Supporting Vulnerable Students During School Closures and School Re-Openings, reports on the ways in which school closures have had a profound impact on all students, specifically children and youth from vulnerable populations. Such youth from vulnerable populations, who are more likely to confront additional barriers, comprise the following demographics: students from low-income and single-parent families; students from immigrant, refugee, ethnic minority, and Indigenous backgrounds; students with diverse gender identities and sexual orientations, and; students with special education needs (OECD, 2020a). Vulnerable students especially suffer and bear the brunt of systemic inequities and barriers throughout the pandemic, given their deprivation of physical learning spaces and resources that offer social and emotional supports available in schools, coupled with essential services such as school meal programs.

Similar to findings reported by the OECD (2020a), Eizadirad and Sider (2020) identify how students who enjoy financial security and/or have access to supportive home environments will find challenges related to the pandemic and virtual learning easier to overcome in comparison to students with poor/limited access to resources (or considered to have special needs). Eizadirad and Sider (2020) frame and situate such inequities as sequential “critical events” (para. 6) within the 2020 pandemic year in particular. The first critical event encompassed social movements across Canada that addressed anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism, which in turn gained significant mainstream media coverage, reporting, and advocacy work to challenge policies and practices that privilege whiteness and, at the same time, oppress non-dominant social groups (Eizadirad and Sider, 2020). The second critical event comprised school closures in mid-March of 2020, thus resulting in learning disruptions and a rapid shift to online learning with challenges surrounding access to technology and high-speed Internet connection to complete school work in a time efficient fashion. In this manner, a fundamental call to action requires an investment “in place-based learning where schools can adapt policies and practices to reflect the needs of their student demographics and surrounding community, or else we risk reproducing similar power dynamics that historically privilege whiteness at the expense of marginalizing others” (Eizadirad and Sider, 2020, para. 12).

Further to pandemic challenges surrounding the degree of ongoing parental support available in a child’s home when learning remotely, discussed in the previous section, there remains concerning inequities related to children and youth’s socio-emotional needs, which have not been met throughout the pandemic. The strong sense of belonging that students acquire in relation to their respective school community may in fact “be lost unless they can keep in touch for learning, but also social activities, such as virtual games and reading buddies, via online resources like Zoom. The lack of social contact can be particularly impactful for vulnerable students: those with broken families, abusive families, in foster care, suffering from food insecurity or lacking housing” (OECD, 2020a, p. 9). Yet suddenly, such disparities in mental health and social-emotional well-being have been profoundly highlighted by the pandemic given that many students lack access to vital necessities offered by school systems and within their communities at large, ranging from counselling to social and medical services, for example.

Growing mental health challenges, especially amid COVID-19, however, illustrate the need for a comprehensive and equity-oriented mental health strategy (Jenkins et al., 2020). In an article published in The Conversation Canada, mental health researchers conducted a national representative survey in partnership with the Canadian Mental Health Association surrounding the mental health consequences of COVID-19 in Canada (Jenkins et al., 2020). The researchers identified that increases in mental health challenges are specifically “attributed to months of physical distancing, growing job loss, economic uncertainty, housing and food insecurity and child care or school closures” (Jenkins et al., 2020, para. 4). The data is indeed pronounced for those affected by systemic oppression and food insecurity in particular, whereby “[t] his concern was magnified to affect 37 per cent of those living in poverty, 28 per cent of those with a disability, 26 per cent of racialized people and 25 per cent of Indigenous people” (Jenkins et al., 2020, para. 9). While this research reaffirms how mental health challenges are magnified for oppressed students due to aspects of their identity such as their gender, income, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, Ciuffetelli Parker (2015) stresses that it is imperative to “reframe our thinking and push past preconceived notions of class, race, culture, and stereotypes of what it means to be poor. We must focus on conditions of poverty rather than attributing the problem to students and families who experience poverty” (p. 1).

Systemic Barriers in School Systems

The relationship between socio-economics and systemic barriers in educational landscapes has garnered much attention in the wake of school closures due to COVID-19 and fundamental social justice activist global movements, such as Black Lives Matter. Nonetheless, poverty is the root cause of many systemic barriers grounded in economic inequity. It is important to note:

Coronavirus hasn’t caused the educational inequities that impact students. But it has shed a light on how our most vulnerable communities are marginalized, silenced and oppressed systemically due to lack of access to opportunities perpetuated historically, socially, economically and politically via Canadian institutional policies and practices including by schooling (Eizadirad and Sider, 2020, para. 3).

Bell hooks (1994), for instance, closely examined how African American students from low-income working families were the most vocal about issues related to socio-economics and “about issues of class” (p. 182). hooks 1994) found that African American students “express [ed] frustration, anger, and sadness about the tensions and stress they experience trying to conform to acceptable white, middle-class behaviors in university settings” (p. 182). What remains significant is that systemic barriers, ranging from students’ lack of technology to systemic biases and prejudices held against marginalized and/or oppressed youth, set the precedent for students’ access to curriculum knowledge (e.g., type of curriculum work assigned) and academic success (e.g., academic achievement in terms of grades attainment).

Jean Anyon (1980) article, “Social class and the hidden curriculum of work,” illustrates such disparities in students’ inequitable access to curriculum work based on socio-economics; that is, a child’s socioeconomic status is a precursor to the type of curriculum work they will access according to their income and family circumstances/dwellings. The article examines findings from five elementary schools in the United States, which are situated in what the author refers to as “contrasting social class communities” (Anyon, 1980, p. 67). Upon analysing data retrieved from assessment of curriculum and other materials in each classroom, classroom conversations, and interviews of students, teachers, principals, and district administrative staff, Anyon (1980) found notable differences in the type of school work assigned to low-income, middle-income, and high-income students. Foremost, students of low-income were offered curriculum that prepared them for future wage labour that is mechanical and routine in nature. In contrast, students who attended the “affluent professional school” (i.e., students of higher income) were granted rich curricular opportunities to develop linguistic, artistic, and scientific skills/expression necessary for cultivating society’s artists, intellectuals, advancements in science, and other professions. Students of middle-income were offered lessons, instruction, and assignments appropriate for employment such as paperwork, technical work, and social service in private and state bureaucracies. Reserved for students of high income was rich curricula that cultivated their knowledge of and practice related to ownership and control of the means of production in society, but also their control of physical capital. The varied differences in curriculum for student participants in Anyon (1980) study both reveals and suggests a problematic “hidden curriculum” (p. 89) for students of diverse SES: differing curricular, pedagogical, evaluation, and classroom practices were offered for low-income, middle-income, and high-income students. These varying classroom curricula and practices serve to replicate socioeconomic disparities, as they prepared students for particular educational and career trajectories aligned with their current socio-economic status. Thus, these curricular inequities illustrate how hidden barriers students from low-income must overcome have a lasting impact on their educational and career aspirations and success.

As evidenced in the study cited above, we can see that not so long ago, in the 1980’s, systemic biases and prejudices were held against the most vulnerable and oppressed students, according to factors such as SES and teachers’ (biased) expectations of student achievement based on demographics. Unfortunately, this still remains a permeating practice and lived reality for many students of diverse backgrounds and identities in Canada and beyond, where unconscious assumptions of diverse and vulnerable groups of students, many who also live in poverty, result in students being deprived of an equal education based on stereotyping and systemic discrimination. One such systemic practice has been the streaming of students away from academic pathways based on implicit bias of students’ academic achievement ability. What follows are examples of streaming practices as reported in the literature.

Streaming Low-Income and Marginalized Students in School Systems

There has been considerable literature on the systemic issue and discriminatory practice of streaming students in Ontario school systems. COVID-19 has especially highlighted the systemic inequity and barrier of streaming, particularly for Black, Indigenous, People of Colour (BIPOC). However, we can see that the biases cited in the literature extend beyond BIPOC children and youth given that such biases are attributed to student populations for many reasons: gender, age, race, ability, language, socio-economic variables, family dynamics, dwellings, home support, and students’ behaviour in the classroom. Consequently, school systems have profiled students (i.e., achieved through stereotypes and labels) whereby students with high achievement levels are polarized, juxtaposed, and contrasted to youth with low achievement levels and those who are typically streamed. For instance, consider the following labels and stereotypic profiling of students: low-income students versus high-income students; the “troublemakers” (behavioural/delinquency) who are “falling through the cracks” versus the academic “superstars” who always complete their homework; and the students with poor family support “who do not care” about their education versus the high-achieving, hard-working student who takes every effort to improve their academic performance (e.g., via tutoring). The case study of Anyon (1980) research, cited above, is not an isolated example of how academic outcomes and limited access to curricular knowledge—what we would now call as “dumbing down the curriculum”— vary because of implicit systemic biases attributed to specific student demographics and are aligned with unconscious discrimination and stereotyping educators hold about particular students. In order to contextualize such biases for diverse student demographics, we provide a review in the subsequent section of the literature review.

Cited in the literature reviewed are patterns of streaming that can be notably exacerbated for students living in poverty and low-income dwellings. In a study conducted by Parekh et al. (2011), which was based in Toronto, the researchers found that the following groups lacked access to “socially valued educational programs”: low-income students, students enrolled in Special Education, and students whose parents/guardians did not obtain a post-secondary education (p. 249). Data from the study also revealed the degree to which low-income students were overrepresented in receiving special education services coupled with their enrollment in other programming that serviced/offered few options for post-secondary education. As a result, Parekh et al. (2011) found that work-oriented programs were most notably made available in the lowest income neighbourhoods in the city of Toronto:

Unless we assume that wealthier students are inherently more academically capable, this correlation is disturbing, all the more so given the international and Ontario evidence that suggests that taking applied courses itself may not merely reproduce disadvantage, but actively exacerbate the risk of problematic academic outcomes (People for Education, 2013, p. 6).

The recurring issue here is the intrinsic connection between 1) systemic streaming that offers limited and fewer academic opportunities for students and 2) a child’s SES.

Streaming students from low-income households into less academic courses follows the impacts this has on student engagement and retention in education. Clandfield et al. (2014) make reference to a Toronto study, in which the Toronto District School Board (2012; as cited in Clandfield et al., 2014) found that 25% of students dropped out by the end of the five years of their secondary school experience, and among this group, “there were more than three times as many dropouts from families in the lowest decile (tenth) of family income as those in the highest-income decile” (Clandfield et al., 2014, p. 79).

Streaming and BIPOC Students

BIPOC students face discrimination and systemic barriers in their schooling through the practice of streaming into lower non-academic programs, unfair targeting for expulsion, and have low rates of secondary school completion (Colour of Poverty, 2019a). As documented in a comprehensive fact sheet published by Colour of Poverty—Colour of Change: “Children from poor families are half as likely to attend university as those who are well-off, and some communities of colour and Indigenous groups have very low rates of high school completion” (Colour of Poverty, 2019a, p. 2). Furthermore, 41% of chronically poor immigrants (living below the Low Income Cut-Off for 5 years consecutively) obtained degrees, while the income gap between racialized and non-racialized residents in Canada increased from 25 to 26% (Colour of Poverty, 2019b). Here in Canada, The Walrus reports on prolific data that detail anti-Black racism in Canadian education where schools can in fact be a site of harm, degradation, psychological violence, and discipline for many Black youth (Maynard, 2020). The Walrus similarly describes how the streaming of students (according to race) into lower tracks of educational opportunity is still a current practice, especially in Toronto, Canada, “where Black students make up 13 percent of the student body but only 3 percent of those labelled “gifted,” compared to white students, who are one-third of the student population but more than half of those labelled “gifted” (Maynard, 2020, para. 9). Hence, Black, Indigenous, and other marginalized students are under-represented in enriched and gifted classes (James, 2020). Black youth are streamed into lower tracks given systemic factors and prejudice, such as student records, low educational performance, and racial stereotypes and expectations held by teachers (James, 2020). Indeed, recurring patterns of systemic oppressive practices in education target BIPOC students given their overrepresentation in applied streaming, incarceration, in-school suspensions, homelessness, drop-out rates, poverty, and precarious employment (Eizadirad and Sider, 2020).

As evidenced in the data cited herein, implicit biases have been—and are still attributed—to marginalized students in school systems, while also internalized by guidance counsellors, teachers, and society at large. These biases determine students’ academic success and entrance into post-secondary institutions. With specific reference to Canadian research based in Southern Ontario, Shizha et al. (2020) investigated the ways in which newcomer students, particularly those of African origin, are discouraged from pursuing school curricula that would otherwise guide them towards their desired career aspirations. This discouragement, however, is attributed to systemic structures in schools whereby teachers and career counsellors hold negative, racist, and prejudicial stereotypes about not only African students themselves, but also their abilities, intelligence, success, and academic performance (Shizha et al., 2020). What remains significant is that the presence of institutional racism, coupled with the streaming of youth, has been profoundly accentuated by the Black Lives Matter movement and protests that voice inequities related to systemic racism of African youth. Shizha et al. (2020) assert,

The BLM protests have brought to the surface a history of systemic racism and discrimination, which permeates the politics of race and that of education. This history of discrimination is found in the ways Black students are treated by school teachers, counsellors and administrators who do not see education and career preparation as processes that matter for the future of Black students. It is these privileged gatekeepers who apply a complex process through which African students are subjected to differential and/or unequal treatment (para. 8).

Streaming and Biased Notions of Achievement

Further to the biases cited herein is the phenomena of labelling students as “academic achievers/superstars,” and “good students who complete their homework” versus those who are “dropouts” and attain low achievement scores in their schooling. Clandfield et al. (2014) publication of Restacking the deck: Streaming by class, race and gender in Ontario schools, documents how the practice of streaming based on students’ race, ability, SES, and gender, still prevails in education. The authors’ discussion on the history of intelligence testing in schools, however, is intrinsically related to the types of labels placed upon youth who are not the “high-achievers.” For instance, Clandfield et al. (2014) discuss how intelligence testing, which has been proven to be notably biased and in favour of White middle-/high-income students, “can be seen largely as an effort to devise more efficient means to sort people for their social destinies on the basis of supposedly fixed intrinsic capacities” (p. 27). In this case, the history of intelligence tests has become the basis for inferring the general intelligence of elementary and secondary students via high stakes assessment and evaluation, thus setting the precedent for labeling and streaming them in their educational trajectory. Furthermore, when serving children and youth with exceptionalities, students with Mild Intellectual Disability (MID) and Behavioural needs will be accommodated in Applied or Locally Developed level courses (i.e., workplace-directed programming), while students who are designated as Gifted will enter the regular Academic level stream with in-class enrichment curriculum (Clandfield et al., 2014). As this book makes clear, the practice of streaming students “is one way the public educational system serves to restrict access to some advanced forms of knowledge and legitimates political and economic inequality” (Clandfield et al., 2014, p. 298).

In an article published in the Harvard Graduate School of Education Magazine entitled, “The Troublemakers”, Lander (2018) writes about her experience as a secondary school teacher in the United States by responding to a permeating question in her writing:

When students act out, why do we seek out flaws in their character? Shouldn’t we instead search for the flaws in our schools and our teaching, holding us, the adults, primarily responsible? Shouldn’t we find better ways to understand the problem children, the ones we label the troublemakers (para. 1)?

The demographics of Lander (2018) U.S. History class comprised 11th and twelfth-grade students who were recent immigrants and refugees originating from more than 25 diverse countries. In her article, Lander (2018) focuses upon a student named Joe, who she describes as a funny, opinionated, and polite student. Joe also had a loud volume in the classroom and often required frequent reminders from his teacher to raise his hand when speaking aloud, as opposed to calling out during inappropriate times. Lander (2018) described how “[w]e teachers all have our Joes. Our students who consistently call out, talk back, refuse to participate or sit down or stay on task. They throw our lessons into disarray, make our heads pound” (para. 8). Lander (2018) goes on to recount the many methods teachers often employ in order to manage and support the “troublemakers” in class like Joe, such as utilizing tracking systems, implementing rewards for desired behaviour in the classroom, and deploying periodic changes in seating plans. Moreover, she highlights how schools often respond to the “troublemakers” who exhibit misbehaviour by excluding such students through practices such as timeouts, visiting the principal’s office, and assigning suspensions and expulsions (Lander, 2018). In a similar vein, Jarvis and Okonofua (2020) research closely examined the degree to which biases affect school leaders, particularly school principals’ severity of discipline in response to managing both White and Black students’ misbehaviours that occurred in the classroom. Jarvis and Okonofua (2020) investigated “whether the racial stereotyping processes that affects teachers’ roles in the disciplinary process might also apply to principals’ roles in the process by testing how race impacts disciplinary decisions” across two misbehaviours (p. 493). The study, which was based in the United States, comprised a sample of public middle and high school assistant principals across two misbehaviors. Jarvis and Okonofua (2020) found that the school principals “endorsed more severe discipline for Black students after the second misbehavior compared with White students. Because misbehaviors were held constant, we can conclude it is due to the student’s perceived race and not aspects of the misbehavior” (p. 496). Furthermore, the researchers found that Black students were not only more likely to be considered as “troublemakers” compared to other White students, but also received harsher punishments from their school administrators, such as the assignment of a greater number of detention days. This article, therefore, highlights the labelling process that is inherent to biased disciplinary actions for “troublemakers” by virtue of systemic discrimination and the legacy of labelling students. The higher rate and length at which Black students are excluded, in comparison to their White peers, also raises concerns of how these more severe patterns of punishment are impacting marginalized students’ academic success.

Resilience and Marginalized Students

The American Psychological Association (2020) defines resilience as follows: “the ability to adapt well to adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or even significant sources of stress” (para. 3). The Ontario College of Teachers (2020) also encapsulates resilience as possessing the skill to solve problems, cope with challenges, and find new opportunities. A resilience mind-set, however, “acknowledges that the infinite variety of future threats cannot be adequately predicted and measured, nor can their effects be fully understood. Resilience acknowledges that massive disruptions can and will happen” (OECD, 2020b, p. 11). In this manner, students of various backgrounds, identities, living circumstances, and ability are taught that their resiliency is testimony to their ability to overcome adversity in their personal-professional experiences. Resilience training through curriculum design and educators’ pedagogical practices serves as a supposed solution to support marginalized and vulnerable students. However, is the push for resiliency training truly conducive for all students who face systemic barriers and inequities in their schooling? Education systems themselves may actually “have become an adversity through which people must pass as part of their preparation for society” (Shafi, 2020, p. 59). In her research and examination of resilience in education, Shafi (2020) writes,

The drive for improving standards in education has led to a standardisation of education (through national curriculums), a measurement culture (through incessant national and international tests), a surveillance approach (though e.g., OFSTED), all combined with a rapidly changing society means that young people need to be resilient just to navigate the systems and structures of a formal education system (p. 60).

Indeed, the term resilience appears to have become a buzzword that “invited critics to suggest a conceptual haziness and a temporary fashionableness, which has lent support to those who argue that the word has come to mean everything, but nothing” (Shafi, 2020, p. 69). Moreover, Shafi (2020) makes it clear that the concept of resilience is “by no means a silver bullet—it cannot solve problems but it can help provide the environment for solutions to prosper” (pp. 69–70). As advocated by the OECD (2017):

Schools are not just places where students acquire academic skills; they also help students become more resilient in the face of adversity, feel more connected with the people around them, and aim higher in their aspirations for their future. Not least, schools are the first place where children experience society in all its facets, and those experiences can have a profound influence on students’ attitudes and behaviour in life (p. 3).

Therefore, in deconstructing the resilience literature cited herein, we can see that there is a critical call to action for educators to support students in developing not only the resilience to cope with daily challenges both in and outside of the classroom, but also developing the resilience to cope and then appropriately respond to systemic structures and barriers in society that prevent them from achieving their fullest potential and personal-professional aspirations.

Practices and Policies in School Systems

In Restacking the Deck, Clandfield et al. (2014) argue:

The way the system has been structured by those in power and the ways in which teachers are required to work within these prescribed boundaries are mainly at fault: the grouping, selective treatment of students, differential program streams, differential expectations, the large classes, the pressure on teachers to cover a standardized curriculum, the lack of opportunities and resources for teachers to offer innovative curricula, courses and programs to students, not to mention the multitude of regulations, policies and procedures that determine where and how teachers will carry out their duties (p. 7).

Indeed, schooling for a new normal will meaningfully and effectively manifest only when teachers and students are placed at the center and are actively involved in all phases of reformation (i.e., planning to implementation to useful assessment and evaluation for all students) and advocate for the particular needs of their school community (Clandfield et al., 2014). At no other time during this pandemic global crisis, and as the world waits in hope for a healthier tomorrow, is it ripe for a meaningful new normal of schooling for an equitable education for all students.

In relation to the unprecedented changes in education and its implications for educator providers (both pre-service and in-service), the disruption of COVID-19 “has changed education forever” (Association of Canadian Deans of Education, 2020, p. 2). Recently, the Association of Canadian Deans of Education (ACDE) released a position paper advancing that “[a]t the core of challenges and opportunities created by COVID-19 is how to reimagine a system of education based largely around physical schools, and how to prepare educators” (Association of Canadian Deans of Education, 2020, p. 2). The Association of Canadian Deans of Education, 2020 recommendations are part and parcel of its five high-level markers that ensure investment in flourishing via education and teaching in a present and post-pandemic Canada. The five markers are: 1) Responding directly to increase mental health and well-being and other needs of students and colleagues due to the pandemic; 2) Ensure the prioritization of Indigenous education equity in the national and regional COVID-19 response planning and implementation; 3) Capacities and capabilities related to ensuring ongoing professional learning for new and experienced teachers; 4) Connectedness and cohesion associated with teachers’ participation in community-based post-pandemic initiatives, in addition to in-school activities and educational research; 5) Resilience and transformation through investment in research within the field of education, human capital, embracing innovation, leadership, and knowledge transfer.

The existing literature takes into account the lived reality that high-income, privileged students whose parents have obtained higher levels of education and better-paid, prestigious jobs benefit from accessing “a wider range of financial (e.g., private tutoring, computers, books), cultural (e.g., extended vocabulary, time-management skills) and social (e.g., role models and networks) resources that make it easier for them to succeed in school” (OECD, 2016, p. 63). Students from families with lower levels of education or those severely affected by low-paid employment, chronic unemployment, and poverty (OECD, 2016), are not provided the same academic opportunities, cited above, in comparison to their affluent, higher-income peers. The findings of systemic barriers in the literature spotlight the dire need for schools to seek ways to establish human connections with their community of learners, affirm student voice and identity within virtual and face-to-face classrooms, and acknowledge students’ lived experiences, aspirations, and interests (Shah, 2019). This paper will exemplify a lived curriculum (Kitchen et al., 2011) of teachers working alongside students during COVID-19 where relational stories inform an urgent need for schools to recreate systems of care, equity, diversity, and inclusion for all.

Theoretical Frameworks

Narrative Inquiry

This research is a narrative inquiry that is school-based research (Xu and Connelly, 2010; Kitchen et al., 2011). Following Clandinin and Connelly (2000) ground-breaking work on teachers’ personal practical knowledge and the professional knowledge landscape of schools, narrative inquiry has long been an empirical research method that often focuses on the examination of how teachers come to know schooling as a lived curriculum. Connelly and Clandinin (2006) use a three-dimensional inquiry space to describe facets of narrative storied experiences as research is conducted. The three-dimensional space helps researchers attend to: 1) temporality of experiences or happenings in the school site and how the temporal past of teaching at the school community, the present of teaching during a pandemic at that same school community, and the future of teaching post-pandemic, help to shape the stories of participants; 2) sociality, or interactions with teachers and students, which help deepen the understanding of each of the stories told; and 3) place, or the topological setting where the events take shape, which aids in making each narrative tangible (Connelly and Clandinin, 2006).

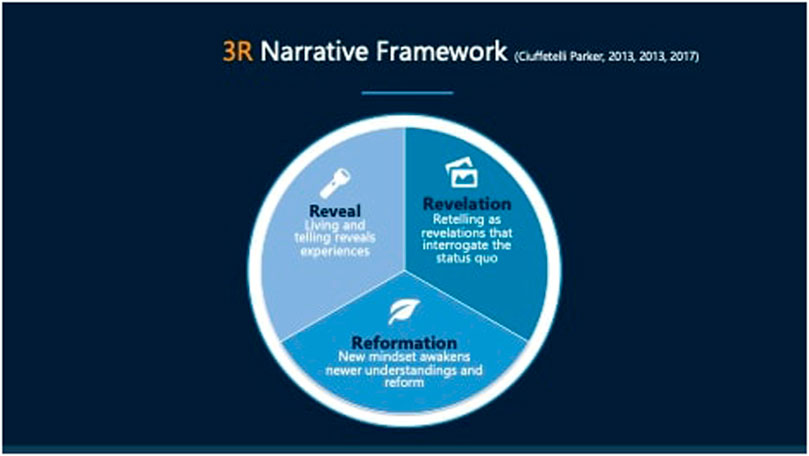

Narrative inquiry is the research form as well as the research method; that is, it is both method and phenomenon (Clandinin and Connelly, 2000). To help researchers deconstruct storied data, a 3R narrative element framework (see Figure 1) was used (Ciuffetelli Parker, 2013; Ciuffetelli Parker, 2014). Ciuffetelli Parker (2019) writes,

Narrative inquiry gives first-hand and authoritative voice to the life stories … The terms narrative reveal, revelation and reformation are useful to help burrow deeply into issues of bias and systemic barriers in educational landscapes. Observing from a wider perspective using the elements of reveal, revelation, and reformation, helps untangle how teaching and learning get enacted when assumptions also get enacted in classrooms, schools, and the larger community.

Narrative reveal is used to help excavate participants’ stories that surface in the living and telling of experiences of teaching in systems that have barriers affecting under-represented students. Narrative revelation shows, once a story has surfaced, how it can be interrogated further against systemic issues in schools, to gain further perspective of students’ and teachers’ lived curriculum, in particular in the present telling of these stories during a pandemic-hindered experience of schooling. What results is a magnified revelation on the barriers that already existed pre-pandemic. Narrative reformation shows how lived narratives of educators can begin to help reform newer understandings through an awakened mindset towards change—in this case towards change of practice in schools to begin to eradicate systemic barriers for students who lack social capacity.

Ethic of Care: Identity and Teacher-Learner Relationships

This research also uses a theoretical framework encompassing an ethic of care (Noddings, 1995). Within this realm of an ethic of care, Nel Noddings (1995) advocates for the reorganization of school curriculum to encompass teaching themes of care in the classroom. It is imperative to note that teaching such themes of care is not merely reduced to “a warm, fuzzy feeling that makes people kind and likable” (p. 676), but rather a teacher’s vocation to ensure that their students are genuinely cared for and learn to reciprocate that form of care towards others. A teacher’s curriculum design that envelops the ethic of care may be focused upon thematic units such as life stages and spiritual growth, while a theme related to “caring for strangers and global others” might include the study of poverty, war, and tolerance (Noddings, 1995, p. 676). Moreover, Noddings (1995) notes a striking reality for many educators surrounding the ways in which teaching care transcends beyond the demands or conventions of traditional hard copy books and pencil/paper pedagogy. Noddings (1995) writes,

All teachers should be prepared to respond to the needs of students who are suffering from the death of friends, conflicts between groups of students, pressure to use drugs or to engage in sex, and other troubles so rampant in the lives of today’s children. Too often schools rely on experts—“grief counselors” and the like—when what children really need is the continuing passion and presence of adults who represent constancy and care in their lives (p. 678).

Evidenced in the above passage is the fundamental importance and moral imperative of diversifying and enhancing the curriculum to meet the academic, emotional, cognitive, and psychological needs of all learners. It is through this diversification that Noddings (1995) argues how “[o]nce it is recognized that school is a place in which students are cared for and learn to care, that recognition should be powerful in guiding policy” (p. 678).

The ethic of care is also a powerful guiding policy within the field of education, as referenced in the Ethical Standards for the Teaching Profession, by the Ontario College of Teachers (2016) in Ontario, Canada. The four ethical standards—Trust, Respect, Integrity, and Care—reflect “the professional beliefs and values that guide the decision-making and professional actions of College members in their professional roles and relationships” (p. 6). The ethical standard of care is defined by the College as including “compassion, acceptance, interest, and insight for developing students’ potential. Members express their commitment to students’ well-being and learning through positive influence, professional judgment and empathy in practice” (OCT, 2016, p. 9). The emphasis placed upon an ethic of care in both accredited pre-service and in-service programs of professional teacher education (OCT, 2016), in tandem with Noddings (1995) advocacy for teaching themes of care in the curriculum, exemplifies the profound interconnection between care and commitment to student success.

Equally important is fostering and nurturing not only students’ identities but also educators’ identities, within the realm of an ethic of care. Hence, closely examining identity and its interconnection with teacher-learner relationships is an integral aspect of proactive practices during and post COVID-19. The participants in this study made this very clear as they shared their narratives. Parker Palmer (2007), The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape of a teacher’s life, advocates for such a vision of the type of compassionate teacher necessary for effective reformation practices that emphasize the importance and cultivation of both educator and student identity. Palmer (2007) asserts that “[t]eaching, like any truly human activity, emerges from one’s inwardness, for better or worse. As I teach, I project the condition of my soul onto my students, my subject, and our way of being together” (p. 2). Furthermore, Palmer (2007) posits the notion that “we teach who we are” (p. 11) and argues that the often concealed, inner landscape of an educator’s life is heavily dependent on self-knowledge. For instance, if a teacher does not know themself, how can they know their own students because, “When I do not know myself, I cannot know who my students are. I will see them through a glass darkly, in the shadows of my unexamined life—and when I cannot see them clearly, I cannot teach them well. When I do not know myself, I cannot know my subject … ” (Palmer, 2007, p. 3). Consequently, an educator’s identity is fundamental to knowing each unique student that comprises the teacher’s community of learners; advocating for students identified needs through practices that are equitable and specifically address vulnerable and oppressed students is the crux of how educator narratives are illuminated in this paper.

Method

This research used a qualitative study approach, with a focus on experiential narratives. Use of narrative telling (Connelly and Clandinin, 2006) by participants provide close-to-the-ground experiences that allowed for revelations and complexities of teachers’ and students’ lives pre-pandemic and pandemic, and situations, school and family, in the context of mixed demographic population of students (socio-economic, ethnicity, race, ability, identity, sexual orientation, etc.), and school programming. Narrative inquiry is a contributing method that represents stories of systemic barriers in school systems, in particular as it regards students living in low-income, racialized, or other marginalized contexts. Practising stories of teaching were lived and told through educator participants (Clandinin and Connelly, 2000; Ciuffetelli Parker, 2014). The narrative retellings give first-hand voice to the life stories of teachers teaching during a pandemic, in view of already existing systemic barriers that minoritized students face. In addition to the research method using narrative inquiry as phenomenon (Clandinin and Connelly, 2000), this paper uses a case-study lens that takes a qualitative close-to-the ground approach, with flexibility to address perspectives and viewpoints (Merriam, 1998). In this way, the research is also complementary in method (Connelly and Clandinin, 2006).

The larger context for this paper is derived from a multi-year research program led by the first author, consisting of over 180 participants in two district school boards within four large secondary school sites from 2015 to 2020. Research program participants in the larger project engaged in specified focus groups as well as interviews consisting of: 48 secondary school students; 24 cross-grade teachers; 12 administrators; 24 parents and; 20 community workers. The larger research project focused on poverty and its intersectionality with schooling, mental health, and diverse student populations (Ciuffetelli Parker, 2018; Ciuffetelli Parker, 2019; Ciuffetelli Parker and Ankomah, 2019; Craig et al., 2020).

This paper drills down to capture the intimate, intensely lived, and storied experiences during the late fall and winter of 2020, of educators in one of the project’s school sites. The school site is described as a suburban large high school, mixed social economic demographic (low-income, middle-income, and high-income families), mostly White students, with about 20% of the population identified as Black, Indigenous, Asian, and Indian. Educator narratives illuminate deep knowledge and insight into pre-existing school systemic barriers prior to the pandemic, and how those same barriers are spotlighted during the pandemic, which garner rapid change practice and necessities.

Participants

This paper has its focus on data collected in the COVID-19 pandemic year 2020 with two educators who were participants of the expansive research project conducted by the principal author since 2015.

Kelsie is an experienced decades-long high school teacher, finishing her last year of her career before retirement. She teaches Anthropology, Psychology, and Sociology, with an additional speciality in teaching English Language Learners and Special Education. Catherine is a veteran educator who heads the district school board’s equity and inclusive unit and is a member representing provincial assessment and evaluation for her district; as well, in her role as a consultant and liaison for K-12 schools, Catherine provides ample collaboration within and outside of K-12 school systems on topics of research, assessment, policy, and curriculum advancement.

Data Sources and Analysis

The data focuses on: one 2-h interview, one conversation, and approximately ten email correspondences between the principal investigator (first author) and participants. Also relevant is data collected from the participants in this paper from 2015 to 2020. This data provides background context and a narrative continuum of their teaching lives, as it relates to systemic barriers in schools, as well as their curriculum philosophy on students’ social capital and access due to living circumstances, race, culture, language, mental health, and ability.

The first author as principal investigator and second author as research assistant conducted the interview by Lifesize call, due to pandemic distancing protocols. The first author then followed up with telephone conversations and email correspondences with the participants for any missing details relating to questions asked. The second author transcribed the recorded interviews and both authors triangulated the data. We asked the general question: How has schooling been successful or not during this global pandemic and in already challenging circumstances for the most vulnerable students? Other examples of the focus group questions/discussions that generated narratives were:

1) If you can reflect on yourself as an educator five years ago to the educator you are today, how have you changed, or not, and what have the conditions of our rapidly changing world revealed about you as an educator or as part of what you believe about schooling and curriculum?

2) What is your experience or revelation about teaching during a pandemic as it relates to students’ accessibility to learning and pathways for secondary and post-secondary education?

3) How has this pandemic shifted the way you think about, or how your students think about issues of equity (i.e., the Black Lives Matter justice movement; diversity, inclusion, equity, poverty, race, culture, language, gender, identity, ability, etc.)?

4) How do you view accessibility for learning, especially for students as it relates to technology accessibility, curriculum accessibility, social capital? How have you processed this and enacted issues of accessibility in your teaching or work with students, colleagues, administration, parents, etc., despite challenges in school systems?

5) What reformations do teachers and society need to embrace, if any, for post-pandemic education?

A bottom-up approach was used to analyze the data (focus group interviews, transcripts, narrative reflections, field notes). Multiple data sources were sought and open-ended interview questions were used; triangulation of themes, categories, and theoretical propositions were used. The use of narratives that explored participants’ core values as a way to more deeply understand the narrative were sought. The data was analyzed by culling all sources, reading and coding the issues, coding the issue relevant meanings as patterns, and then collapsing the codes into themes (Creswell, 1998, 2005).

Limitations

Limitations of the data set of this paper includes the small sample size (from the larger research project and participants). That said, as in narrative inquiry qualitative method, “Story is not so much a structured answer to a question, or a way of accounting for actions and events, as it is a gateway, a portal, for narrative inquiry into meaning and significance” (Xu and Connelly, 2010, p. 356). Narrative inquiry pays less attention to the volume of quantifiable words and numbers, and more attention to the participants’ storied experiences as lived and told through stories on a longitudinal continuum. The stories are represented as “actions, doings, and happenings” (Clandinin and Connelly, 2000, p.79) over a longitudinal research program, and we ensure authenticity and defensibility by paying attention to understanding how this inquiry is anything more than trivial or personal. We set the data garnered against the larger research project where these same participants have been a part of over the last several years, as well as what the narrative inquiry helps us learn about the phenomenon of schooling and systemic barriers during COVID-19.

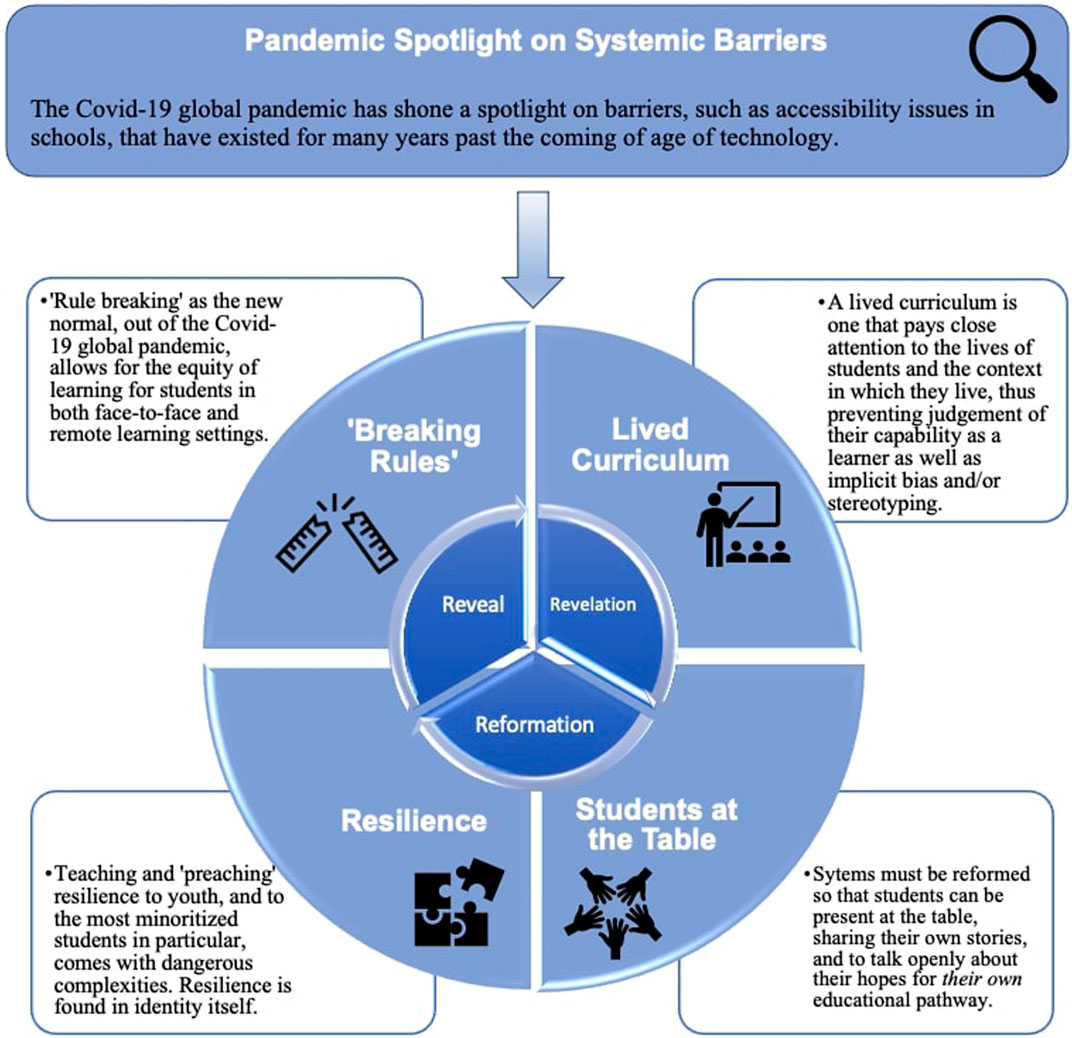

Findings: Narratives of Teaching in a Pandemic

The findings are presented in themes generated from the analysis of data (see Figure 2). The themes focus on interviews and storied responses from educators Kelsie and Catherine, while in the midst of the pandemic as they tell and share: their past and present experiences in teaching and leadership; their relationship with students and colleagues, and; how systemic barriers and accessibility in schools have been further magnified by the pandemic. While both Kelsie and Catherine engaged in sharing their storied experiences, it is Kelsie that shares in abundance her personal teaching narrative, particularly as the discussions took place in the midst of the pandemic while she was teaching in person and, as waves of the pandemic hit, remotely. Alternately, because Catherine’s role is as educator consultant, her storied perspective is in response to Kelsie’s narrative but with a system-wide point of view, memories of her teaching, and present system-based practices and policies that she oversees. The themes are titled: 1) Pandemic spotlight on systemic barriers: Uncovering what was always there; 2) Breaking rules to create a new normal; 3) Lived curriculum: Teacher-learner relationship 4) Students at the table: A move for reforming streaming practices; 5) Resilience: Connection to identity and breaking down barriers.

Pandemic Spotlight on Systemic Barriers: Uncovering What Was Always There

Kelsie identified decades-long shortcomings. Barriers, and accessibility issues for students and teachers in school systems, and how the pandemic shone a spotlight on these barriers that have existed for many years, past the coming of age of technology. She is passionate as she describes necessary tools that all students should have access to in publicly funded schools:

[W]hen we look at the timeline like thirty years, and we look at how things have changed dramatically … if we were back even ten years ago, we wouldn’t have had technology [during a pandemic]. This wouldn’t be happening. We’d all be in isolation as we would have been in 1918. Alright, so we kind of think, you know, it’s a very different approach. Umm, in school, the mandate has always been—and correct me if I’m wrong—if you are expecting students to perform in a certain way, you must provide them with the equipment, the tools necessary for them to do their learning … in the past it was a textbook. So, we always had textbooks. You provided textbooks … So if the expectation is that all students are going to have to have internet access at home [the system] is going to have to have technology, whether it’s a Chromebook, a laptop, whatever it might be, at home outside of school—then it must be provided for by the [system]. It has to be. And it has to be equal across the [school]board. We don’t want to segregate, isolate, you know, have students stand out because “well, how come she gets that and he doesn’t get that?” Right? And so, we have to sort of say, you know, when it came to textbooks everyone got a textbook. When it came to pencils, we used to actually give out pencils. Everyone got a pencil. So, you know, since we’re not spending on the textbooks, we’re not spending on the pencils and the paper, then I think we need to provide students—every student, regardless of background, regardless of socioeconomic status—with the exact same tools. And then we are leveling the playing field.

Kelsie further shares that there can be other changes made that pertain to scheduling, in particular at the high school level:

I don’t think that you can deliver during a pandemic Monday to Friday, four periods a day. That is not reasonable. It’s not healthy for the children because they’re going to be competing for time slots, and logging in, logging out, four times a day, which is just … not gonna happen. It’s gonna create more issues than not. So, I think moving to more of a post-secondary style of delivery where you are meeting once a week. Maybe Monday’s Period 1, Tuesday is Period 2 … I mean, you just have to re-imagine this so that way there is consistency.

Further, she explains why scheduling similar to post-secondary systems, as an institutional reform, is vital for student success:

There is … a schedule because children need a schedule. [Students] need to know when things are happening, and this will reduce anxiety for those that are highly anxious. But then those that aren’t anxious at all, now have anxiety, you know, concerns … because their world is turned upside down. So, I think changing it up and being open to saying, Monday’s Period 1, Tuesday is Period 2 … and Friday is … like our office hours. So, I think that there has to be a way of supporting the teacher, the student … and allowing for us to not have to be tied to a particular routine because that’s what it always has been. My quote that I use regularly with class: “If you always do what you’ve always done, you will always get what you’ve always got.” And we can’t keep doing what we’ve always done. It wasn’t working anyway, to be honest. I’ve been doing this for thirty years—it wasn’t working.

Breaking Rules to Create a New Normal

Kelsie’s values and how she thought about how to create a new way of teaching with technology, a new way of scheduling her courses in high school, and a new way of listening to student needs required, revealed that sometimes what needs to happen is a ‘breaking of the rules’ of sorts, of school working policy and traditional Eurocentric ways of schooling:

Okay. So, I kind of went against the rules. (Laughs). I was a little bit of a—yeah, that doesn’t work for me. (Laughs) … My thought process was: if students are gonna make a TikTok out of me, they’re going to do it in class. They’re still gonna do a little video of me. They’re gonna do it in class. They’re gonna do it online, they got nothing else to do!... Bring it on. You know? It didn’t make a difference to me. So, I actually went live immediately. I did meetings, virtual meetings, and I have to tell you I had at the very beginning … about 95–100 percent [student attendance].

This is not to say that Kelsie did not have complications, as she reveals her Grade 12 students’ anxieties and sadness about how the pandemic had affected their last year of high school:

Now the students … a lot of them fell apart. My Grade 12s were devastated. But … my very first meeting with them was: “Hi, everybody! We’re gonna not have class today. We’re just gonna talk about how we’re coping or not coping.” And it was a beautiful opportunity for them to look at each other. There were some tears, uh, on both ends. My side, too … that shows the humanness. It shows the impact and it also opens up the conversations for the comfortable ones saying, “I really didn’t want to get out of bed. Actually, I’m still in bed. See!” Umm, you know … it opened up the world for them and then that segued into my lessons because I teach Social Science.

It was as if Kelsie had no choice but to break the rules, despite her being a “rule follower.” She explains:

Well, I’m going to address the rule breaking. That was tough for me, alright. I am a rule follower and … when it comes to getting in trouble, I’m just like the students. No one wants to get in trouble. But I also knew … the benefit of this outweighs any type of repercussion that I would have faced because I knew that my students needed this as much as I did, too. So, there was a little bit of selfishness in this decision as well but I also knew in the long run it would benefit my students [to break the rules]. So, I think with the rule breaking, we do have to ease off a little bit on these protocols where it comes down to: you’re not allowed to go to a student’s house [to deliver a Chromebook], you’re not allowed to phone a student from your personal device [to arrange for technology home support while you are teaching some students in class and some at home]….where we have such a boundary—which is important to have boundaries but in this particular time, in a time of crisis, we [have] to throw everything out … And so that we can maintain some sense of normalcy, right?... We need to create this new normal. We need to re-imagine how we’re teaching. And we need to not have such stringent rules around that.

And I think there has to be more flexibility with regard to when we’re [teaching live], when we are accessible, and when the students will be in class if we’re [teaching] virtually. So, I think that we have to move to this flex time versus this eight o’clock till 2:15 timeline. [8 o’clock to 2:15] doesn’t work.

Rule breaking as the new normal, out of the pandemic, became Kelsie’s new normal of scheduling. What Kelsie long argued during her career as a high school teacher, such as early start times in the morning for still-developing adolescents, was something that caused tension for her during her thirty years as an educator. It took a pandemic for her revelation to rouse and a compel her to “break the rules” for the equity of learning for her students.

Lived Curriculum: Teacher-Learner Relationship

Both Catherine and Kelsie reveal their inner deep-set thinking of the teacher-learner relationship and how they both envision the making of curriculum that is both subject specific but also a lived curriculum that plays close attention to the lives of students and the context in which they live. Catherine shares this revelation:

I’ve taught every grade—K to 8—but mostly Grade 8. And when I left the classroom several years ago we were having more holistic conversations around students’ learning and achievement based on, of course, their grades but also the learning skills and work habits. And I would argue that at the time, there was this sort of shift to: “Okay. Well, if students, you know”—from the high school lens— “if students are achieving a solid B, let’s say, seventies. Then still they can do academic.” And then I saw some, you know, belief systems [shift]. What teachers believe about students can either cripple them or empower them. So, if you think that, you know, a student misbehaves, umm … they can’t get their homework done, they can’t self-regulate, how are they ever going to survive in an academic classroom?

Kelsie Adds

And that’s our job—is to be the greatest observers of all. The ones to notice … to see the person. And when I talk to my students, when I talk to my friends, I say: “I see you.” And then they know that I’m seeing their potential regardless of the mess that they’re living in, I see you. And I can see what you can bring to this table. Now, I think that’s something that … maybe it can’t be taught. It may become part of who you are as a person and how you deliver, and how you perform … And when we’re looking at offering more as an educator … I used to teach just these students. And I would teach them, and I would support them to some degree, whereas now my role has changed so dramatically that I’m not just their teacher and disseminator of information … I’m assisting them in the next step to wherever they’re going in life … It’s lovely to have this beautiful curriculum and these lovely expectations but…. if you share your stories with your students, to some degree—they see you as a person. And then seeing you as a person, they connect with you. And in connecting with you, that gives you an opportunity to be even greater and to have a greater influence. And so, I really think that’s key for new educators: don’t be afraid to show that you’re human. And don’t be afraid to show your emotion.

Students at the Table: A Move for Reforming Streaming Practices

Catherine, as a systems educator/consultant, and with a progressive pedagogy for teaching, revealed a systemic issue of streaming students that has caused ire throughout the years. She relays how several guidance counsellors mislead elementary students going into high school:

“You know, if you take applied you only have to take this course to get to academic.” No. Kids need more time to feel where they’re at and we need to really revisit what we’re doing about [streaming students into applied courses] and how we’re teaching them … because the applied classes have been offered to the kids with “behaviour problems” and the academic [courses] for the kids who “do their homework.” And that’s how it’s playing out in schools and it’s not right. And I feel really badly about that … And I’ve been playing on this de-streaming with Senior Admin for a while. And when … recommendations came out from the Minister of Education [to eliminate streaming by de-streaming students] … I forwarded it to my Superintendents that: “I wanna spearhead this work at [our district school board]. I believe in de-streaming.” I’ve been talking about de-streaming for years and no one listens to me. Because—I get it. There’s a logistical … there’s unions to work with and what not. But, I’m so glad to see [destreaming] coming and I hope it’s coming for all the right reasons, and to empower our Black and Indigenous students, and people of colour, and all students who don’t see themselves as learners. And we need to help them so they find their way, whatever it may be in life.

It is an issue of equity, and labeling, as Kelsie agrees:

And when I think back to my career teaching Grade 7 and Grade 8, making recommendations, yada yada, for students. Umm, we get into that whole we’ve pegged them at a certain spot. We’ve labelled them. They become the label, and then there’s their life … and as a Grade 8 teacher … I did my job. I did it well. I was very open and looking at the holistic child, not just the academic performance, and made recommendations based on the entire picture. I don’t know that’s necessarily the norm, even in today’s day and age. Umm, and I can only speak to my direct experience with my students and my own children who have gone through the system that feeds our school. And I’ve unfortunately witnessed some negative outcomes.

Catherine adds another revelation, in making sure and allowing students themselves at the table to make decisions about their own education pathway, especially those students who are the most marginalized and racialized in school systems:

And I’d like to add to that I think what you’re saying is sort of connected to what I’m saying. Because I work closely with our student management system operator, the documentation that is currently happening within these notes that are secured, umm, from a system level, are not the flavour of notes you would expect to read about students and you wouldn’t want to read some of these notes. And there’s the whole privacy issue. So, I think what we’re really talking about … is how do we create more opportunities for these conversations to happen with the students at the table? So, we even talk about the transition meetings eight to 9—why aren’t the kids there having a conversation? Because if we can say something about that child, the child should be at the table to explain their own learning journey, what they’re experiencing, strengths, needs … In our student voice surveys, we ask how many students have been involved in those processes and usually the reporting on that is very few. It’s about them! So, they should be at the table and perhaps alongside their families. Students [should be allowed] to talk more intimately around their needs and how we can support them? And I think that’s super important when we’re thinking about our own identities. All of us [who are] White, with lots of privilege. We can’t say that we understand when we don’t, and we shouldn’t. We need to learn. We need to listen.

Resilience: Connection to Identity and Breaking Down Barriers

Student resiliency, especially during the pandemic when all seemed exposed and highlighted as it regarded students’ needs, mental health, academic success, and well-being, was a topic taken up by both Kelsie and Catherine. Kelsie spoke of resiliency past and present:

Resiliency of the students … when I reflect back, students today compared to the past, umm... It’s a different type of resilience that we’re seeing. And I think that them being able to roll with change is really important. This [pandemic] has really kind of put things in the forefront, right? We’ve had to disconnect from everything that we have normally done and find a whole new way of re-connecting. And I think this [pandemic] has truly created an opportunity for Canadians to see how important our education system is to the fabric and the fibre of our country, of our people … And I think that this pandemic has really sort of put in the face of society, it’s like “Oh, wait. We can’t. We need you.” Right? “This doesn’t work this way without [teachers].” And I think that’s kind of like still a key element with the resilience factor that we have trained our students to become more resilient, to cope in a different way.

Catherine acknowledges Kelsie as an extraordinary educator, and provides her own understanding of the term resiliency and how it bumps up against students whose world offers little equalizing of the “playing field,” especially as it relates to student identity and educator identity:

The disclaimer on resilience for me is—I know we reduce it to a set of practices like lessons on empathy, or umm, I don’t know, maybe some sort of meditation or whatever. But if you got barriers in place like, when we talk about being in institution and system level, and barriers in schools and policies, and rules that could … block our attempt to develop resiliency in each other, in students … So, I think it’s important to remember that … Resilience sounds nice but it’s not always possible if everything else is working against us … So, it’s important to recognize, you know, within systems like publicly funded education … what are we doing in our systems and institutions that are disabling these sorts of things, like being resilient? But it’s super important, again, to know yourself as a student, a family member, the educator, a principal—whatever—to know yourself. That identity piece is huge - knowing it and then it sounds like the people who are comfortable enough, like the extraordinary educators we have here … knowing it well enough and being comfortable with it to share it, so you can build some trust and connection with your student, so they can see that to be resilient is possible while hopefully we’re breaking down any barriers for them to be able to act as resilient people.

Discussion of Findings