- School of Education and Professional Studies, Griffith University, Gold Coast, QLD, Australia

The number of international students enrolled in Australian high schools has increased dramatically over the last decade. However, limited research has investigated the unique needs and experiences of these students. In response to a general lack of knowledge relating to this population, a sample of 225 international high school students (93 males, 129 females, and 3 other) enrolled in years 10–12 in Australian independent schools were surveyed to investigate their social wellbeing. The survey included measures of social wellbeing, online and face-to-face connectedness, sense of belonging to their home country as well as in Australia, and the strength of their school connectedness, with the aim of identifying the most significant factors that predicted social wellbeing. Although all the factors made some contribution to social wellbeing, the strongest predictors were a sense of Australian belonging and school connectedness. We also investigated the students’ perceptions around connectedness to their social community and face-to-face and online environments, as well as whether there were any links between online connectedness, social wellbeing, and belonging. While no statistically significant relationships were revealed for online and face-to-face connectedness and their impact upon students’ social wellbeing and sense of belonging, the findings revealed the nature of positive and online experiences and the fact that while risks of online activities were substantial, in general, participating in online activity brought about more benefits than harm. Additionally, an unexpected finding revealed that, over time, the international students’ sense of belonging and social wellbeing steadily decreased, which indicates an increased need for support for these students as they progress through the student life in Australia.

Introduction

Australia has seen major growth in international education over the last 20 years (Marginson, 2007; Meadows, 2011; Australian Government, 2018a) to the point where it represents one of the nation’s highest service exports, contributing $40 billion to Australia’s national economy in the last fiscal year (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020). While the majority of growth has been in tertiary/post-compulsory education, the numbers of international students enrolled in Australian primary and secondary schools have also been on the rise. Indeed, in 2019, there were approximately 25,000 international students studying in Australian schools (Department of Education, Skills and Employment, 2020). This growth in enrolments has been paralleled by a rise in the research that focuses on international education, including increasing interest in the challenges associated with catering to the educational, social, and emotional needs of these students (Sawir et al., 2007; Chu et al., 2010; Barry et al., 2017). The focus of this previous research has been primarily on young adult students enrolled in tertiary education, with little that addresses the needs of high school-aged international students. Although there are commonalities between the two broad groups (for example, the realities of living and studying in an unfamiliar country) in terms of both age range and developmental needs, the two cohorts are very different.

In this article, we report the findings of the lead author’s PhD study, which is part of a larger Australian Research Council (ARC) funded study, aimed at addressing this gap in the literature, by focusing on this younger and differently vulnerable cohort. This project titled International Students in Secondary Schools was explicitly designed to investigate the experiences of this student population in order to understand their overall experiences. In this article, the focus is on social wellbeing. According to Keyes (1998), social wellbeing can be defined as “the appraisal of one’s circumstances and functioning in society” (p. 122). While the term (and its associated issues) is often subsumed by broader categories of “student wellbeing” or “psychological wellbeing,” social wellbeing actually focuses on a quite specific aspect of psychological health, that is, on an individual’s feelings of social integration, social acceptance, social contribution, social actualization, and social coherence. Social wellbeing is a particularly important contributor to overall wellbeing in adolescents, as they derive much of their sense of self-worth from the social evaluations of their peers and important adults. The consideration of social wellbeing therefore draws attention to the strength of the social connections (Chu et al., 2010) and the factors that impact upon the social wellbeing of international high school students, such as a sense of belonging and various forms of connectedness, including online and face-to-face. Research has shown that a strong or robust sense of social wellbeing impacts upon young people’s security, comfort, and affect and contributes to positive functioning in adulthood (Newton-Howes et al., 2015; Chervonsky and Hunt, 2019). In focusing on the social wellbeing of international high school students, this article provides educators with new, important insights into the experiences and needs of a population rendered twice vulnerable due to their age and their status as international students.

The article is divided into four sections. In the first section, a brief overview of the context of the research is provided and the relevant literature is briefly discussed. In the second section, there are details of the research design, with an overview of the purpose-built instrument that was used to collect data on issues relating to social wellbeing, connectedness, and belonging. A short outline of the theoretical resources that underpinned the research design and data analysis is also provided. The findings are then outlined in the third section before finishing in the final section with some conclusions and recommendations for further research and practice.

Background and Literature

First, it is important to acknowledge that this article reports on the research undertaken in Australia where international education, as noted above, is one of the largest non-resources export and the largest services export industries (Australian Government, 2015). Though growth in enrolments has been hurt by the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of the currently enrolled students exceeds 708,000 (Department of Education, Skills and Employment, 2020). The current numbers are the result of a long history of national investment in this field of activity. In 1951, under the Columbo Plan, Australia encouraged international education partnerships, a period of investment which provided a mechanism for Australia to exercise soft power and diplomacy (Lowe, 2015) and achieve multiple goals in terms of understanding and establishing relationships with diverse countries (and their economies). Since that time, successive federal governments have continued to see the international students as both an important source of revenue and a bridge between Australia and their origin nations, a desire reflected in the current policy which asserts that “relationships developed through international education help maintain international trade, investment and goodwill” (Australian Government, 2015, p. 6). Government priorities have been paralleled by the policies of the educational leaders (in schools and university) who have commonly argued that the cultural exchange offered by the international students enrolled in Australian schools and universities benefits the individuals, the institutions, the communities, and the nation by fostering globally connected communities, increasing cultural awareness, and generating intercultural capacity (for an example of this kind of rhetoric, see Robertson, 2011).

Despite all the regularly asserted benefits that flow from international education, the international students occupy a complicated position in the educational landscape of Australia. On the one hand, “they,” as an often-undifferentiated student group, are valued for the fees they pay, the connections they help to foster, and the “diversity” they bring to the community (Australian Government, 2015). On the other hand, this same group of students is often the target of discrimination and alienation (Marginson et al., 2010), particularly where there is some perception that they are diluting a local identity, failing (or refusing) to accept local customs, and/or taking resources (including university enrolment places, jobs, or accommodation) away from the local communities and domestic students (Mills, 2018).

The overall vulnerability of the international students population has been powerfully illustrated by events relating to the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. This crisis has prevented many international students from entering Australia to begin or continue their studies and has prevented others from completing a lengthy and expensive education. Others who were in Australia when the pandemic was officially declared found themselves isolated in their community and unable to return home. The closure of university and school campuses, restrictions on travel, and ultimately the closure of borders coupled with widespread loss of employment have created a uniquely stressful set of experiences for the international students (Bamford, 2020). The governments responded to the loss of employment and the experiences of isolation with various forms of support for the local businesses and domestic students. However, few of these benefits were directed to the international students. Indeed, in the midst of the crisis, Australia’s Prime Minister urged the international students with financial problems to “return to their home countries” (Gibson and Moran, 2020). This blunt comment highlights the juxtaposition that the international students experience between being welcome for the fees they contribute and at the same time being regularly devalued and subjected to overt and covert racism (Mills, 2018; Mwenge, 2018). In this case, the comments were directed at students in universities, but it is reasonable to argue that the international students in all contexts navigate a similar risk: the potential to be treated primarily (although not always so deliberately) as commodities, not as people (Paltridge et al., 2013).

This commodification of the international students and the impact this has upon their mental health and overall wellbeing have been identified in literature in various forms and contexts. This article, and the project it relates to, is informed specifically by literature that has mapped major influences and threats to students’ social wellbeing, including friendships, racism, and online activity. We acknowledge wellbeing has different interpretations and is linked to different concepts.

Literature Review: International High School Students and Issues of Wellbeing, Connectedness, and Belonging

The literature relating to international students is diverse, but much of it focuses on issues that might be broadly thought of as student experiences (positive and negative, face-to-face, or online) and their relationship to, or impact upon, the phenomenon referred to as “student wellbeing” (Gomes et al., 2014). The researchers drawing upon the resources of psychology have consistently argued that wellbeing is fundamentally tied to the social connections such as family, peers, and community. Baumeister and Leary (1995), for example, have argued that relatedness is a fundamental human need essential for psychological wellbeing, but it is particularly important in adolescence and the transition to young adulthood as the social connections outside the family take on increased importance. In students, the absence of fulfilling and meaningful social connections in school has a detrimental effect on wellbeing (Alharbi and Smith, 2019; Bharara et al., 2019; Gomes et al., 2015; Keyes, 1998) and is associated with loneliness (Sawir et al., 2007), anxiety, and depression (Osterman, 2000; Arslan, 2017). These kinds of insights have impacted upon the educational policy, with many school-based frameworks now emphasizing the need for students to be included in, connected to, and respected by their school community. One example of this is the Australian Government’s Wellbeing Framework which argues that wellbeing involves inclusion:“All members of the school community are active participants in building a welcoming school culture that values, diversity, and fosters positive, respectful relationships,” and student voice: a position that allows students to “feel connected” and “use their social and emotional skills to be respectful, resilient and safe” (Australian Government, 2018b, p.1).

While these have relevance to all students, inclusion and connection for student wellbeing (and we would argue, social wellbeing) take on increasing importance for the international students. Tran and Gomes (2016) argued that connectedness is a central experience for students while in the host country. This view is supported by a research by Gomes et al., 2014, who found that maintaining connectedness to family and friends is important for the wellbeing of the international students studying in Australia. They noted that studying abroad places strain on the quality of these social connections even when they are using social media, chat, and video calls. “Virtual” connection may be an inferior substitute for having those loved ones and friends nearby, and online may not offer the same depth of experience as face-to-face. As compensation, the international students develop new social networks and relationships in Australia, which are also vital in feeling part of the community and connected to others. Lee and Robbins (1995) argued that a core element of social connectedness is a sense of togetherness with peers, and its absence is felt as a sense of “social distance” and isolation. Therefore, having a strong sense of connectedness with others and creating friendships is regarded as an important component of a positive international student experience and directly impacts student wellbeing (Hendrickson et al., 2011).

This body of literature has also shown that the inclusion and connection are not always experienced in positive ways. Indeed, much of the literature that focuses on international students in higher education emphasizes the potential for students who are, in the strictest sense of the term, included in an environment, to feel disconnected and alienated. In other words, there is an important difference between being connected and feeling a sense of belonging. Connectedness refers to the existence of social connections and relationships with others, but a sense of belonging extends to a sense of acceptance and being part of the community (Sumsion and Wong, 2011; Australian Catholic University, 2018). Thus, the students may feel estranged even in the presence of social connection and these feelings matter in important ways. As Atri et al. (2007) have shown, the international students’ sense of belonging was highly predictive of psychological wellbeing, and experiences of prejudice and racism served to undermine that wellbeing.

This highlights the importance of looking beyond the simple measures of “inclusion” or connection to consider the nature of the student experience through the lens of “belonging” (Sumsion and Wong, 2011; Yuval-Davis, 2006). While supportive social connections are important, acquiring a sense of belonging requires not only connection but also acceptance. While true for all people, belonging takes on an increased priority for the international students, as they already feel a sense of difference during the acculturation process (Berry 2005; Cho and Haslam, 2009) due to the high degree of stress experienced during this period (Ye, 2006; Yeh and Inose, 2003). The link between students’ sense of connectedness and their feeling of belonging is captured by a growing literature that explores the politics of belonging: focusing on the ways in which individuals learn, navigate, and are impacted by the physical, legal, and ideological barriers and boundaries which determine who “belongs” and who does not in any geographical, political, and educational situation (Antonsich, 2010; Yuval-Davis, 2006, 2011; Halse, 2018). This growing literature shows us that belonging plays a pivotal role in fostering wellbeing (Akhtar and Kroener-Herwig, 2017) and that “belonging” is always in flux, never settled (Yuval-Davis, 2006; Sumsion and Wong, 2011). The complex interplay between inclusion, connection, and belonging is illustrated within three strands of the literature relating to the international students’ experiences of friendship formation (and associated experiences of loneliness), the international students’ experiences of racism (and risks to wellbeing), and the international students’ use and experiences within online environments.

Barriers to Connection, Social Wellbeing, and Belonging

Research, primarily undertaken in post-school settings, has shown that the international students are interested in forming new connections and new friendships, particularly with domestic students, and that these friendships have important consequences (Sawir et al., 2007). Friendship formation facilitates acculturation and adaptation to the host country, as well as positive academic performance (Glass, 2014; Hommes et al., 2012; Hendrickson et al., 2011). Similarly, friendship formation leads to lower levels of stress and greater opportunities for language learning (Gareis, 2012; Rienties and Tampelaar, 2013).

But while international high school students are routinely embedded in environments where they have access to potential friends (i.e., these students are with other young people in classrooms, school grounds, and often boarding schools), friendships do not automatically develop. Commonly reported barriers to new friendship formation for the international students include issues of language competency (Li and Zizzi, 2018) and familiarity with cultural norms (Williams and Johnson, 2011). These language and cultural barriers convey the sense that the international students are “different” to their local peers and this leads to isolation, exclusion, and often experiences of racism (Baak, 2018; Fahd and Venkatraman, 2019).

Racism is a recurring theme within the international students literature, though there is often a reluctance to acknowledge it by educators (Lee and Rice, 2007). Australia is not immune to this (for a review, see Marginson et al., 2010), with studies finding that the international students experience racism in Australia on a regular basis (Fahd and Venkatraman, 2019; Lawson, 2012; Marginson et al., 2010). Racism can be expressed in diverse ways, including overt acts of racism and hostility such as name calling, expletives, physical threats, and assaults, but it may also be expressed covertly in indirect and subtle ways through snide comments, looks, and avoidance (Dovchin, 2020). While greater attention has been given to overt racism encountered by students, research has highlighted that covert racism is far more prevalent and is even more damaging to cultivating a sense of belonging (Harwood et al., 2018). While racism experienced by university students has been widely reported, it seems that these kinds of experiences might also be commonplace in the high school environment (Mansouri and Jenkins, 2010).

When attempts to form friendships with domestic students are rebuffed or seem unobtainable, the international students often opt to form friendships with students from their own country of origin or other international students sharing similar cultural habits or values (McFaul, 2016; Robinson et al., 2019). Early difficulties forming friendships also tend to persist over time rather than being resolved. Of course, friendship formation requires effort by both the international students and their domestic peers, but when the international students encounter initially negative experiences and are rebuffed, this discourages further efforts (Vaccarino and Dresler-Hawke, 2011). Literature has also shown that the international students do not always have access to the same kinds of non-educational contexts (community, leisure, religious, or diverse extracurricular activities) within which domestic students might develop friendships. This can be tied to issues such as students’ access to groups, a lack of time, finances or transport, or, in many cases, the impact of living in a boarding school (Glass, 2014; Glass and Westmont, 2014).

Experiences of loneliness are very common for the international students. Sawir et al. (2007) reported high levels of loneliness are experienced by up to two-thirds of Australian international students, which has mental health consequences for these students. The authors reported that this results in high levels of depressive symptoms and reduced feelings of wellbeing. Thus, the availability (or lack thereof) of local face-to-face friendships contributes to perceptions of disconnection and loneliness, which results in lower wellbeing for international high school students in Australia (Sawir et al., 2007). This represents another potential pathway by which connection might contribute to both a sense of belonging and ultimately student wellbeing.

To summarize, the literature focused on the international students’ experiences in general, consistently drawing attention to the risk that students studying in Australian high schools may experience a lack of connection, a sense of isolation, and feelings that they do not belong, all of which can impact upon an overall sense of wellbeing. These insights informed the design of the research reported in this article and the survey that generated the data. It is also important to acknowledge here that international high school students—like teenagers across the planet—not only exist in face-to-face environments but also spend considerable time online. Thus, in order to conduct a significant investigation into their sense of wellbeing, it was necessary to attend to online and face-to-face environments. The key issues in the literature which are centered on the relationship between rates and forms of online activity and issues of connection, belonging, and wellbeing are discussed below.

Young People, Online Activity, and Links to Connection, Belonging, and Wellbeing

The ways in which teenagers and young people experience online worlds are the subject of a large body of scholarship, which is not possible to review in depth here. However, there are two important dimensions that are directly relevant to this study. The first is that “being online” has multiple forms, encompassing text and image based social media, video streaming, and other modalities (Finger, 2017). This range of activity takes on increasing importance for international high school students, as it supports communication with their established friendship and family networks abroad. The second is that online activity can have both positive and negative consequences (Ito et al., 2010; Third et al., 2017) and thus can impact on social wellbeing in various ways.

Much has been written about the potential for online spaces to offer young people new ways to develop a positive sense of self (e.g., Greenhow et al., 2009; Tran and Gomes, 2016) and for emotional expression (e.g., Prieto-Welch, 2016). Research has also shown that online spaces can be experienced as sites of risk (Best et al., 2014; Espinoza and Juvonen, 2011). Young people report experiences of online harassment, bullying, and intimidation (Hamm et al., 2015), as well as less overtly negative experiences such as being left out, ignored, or excluded from online groups (Whittaker and Kowalski, 2015). The literature that relates to the international students and online activity also draws attention to the benefits and the risks associated with the online space.

Positive Aspects of Online Activity in terms of Connectedness, Belonging, and Wellbeing of the International Students

The subset of literature exploring the relationship between the online activity and the international students highlights a number of positive benefits. Research has highlighted that connecting to family and friends in their home countries is very important and beneficial to the international students (Sawir et al., 2007). Alfarhoud et al. (2016) argued that this fosters a sense of connection with their home country, their families, and friends; hence, they advocate for access to social media during class-time because it can reduce frustration during the acculturation process and feelings of homesickness. The importance of this connectedness to family and friends as a protective factor in buffering against loneliness and acculturative stress cannot be overstated, as it facilitates a sense of belonging that is sometimes lacking in their face-to-face relationships. McCarthy (2013) has also piloted friendship formation interventions with the international students, showing them how they can use social media to strengthen existing and make new friendships. Additionally, many students report that connecting online is beneficial in terms of helping them manage emotions (Harvey et al., 2017), which also positively impacts upon their wellbeing (Saha and Karpinski, 2018). However, further research is needed to determine how online activity can benefit high school-aged international students, as well as the ways they engage connectedness and how this impacts upon their sense of belonging and social wellbeing.

Negative Aspects of Online Activity in terms of Connectedness, Belonging, and Wellbeing of the International Students

Despite presenting many opportunities, not all online experiences are positive and supportive (Tynes et al., 2013). Consistent with the wider literature around the risks associated with online activity (risks that may be exacerbated for minoritized students such as students of colour), research focused on international cohorts has found that online engagement can actually exacerbate existing feelings of exclusion and discrimination for the international students in Australia (Zhao, 2017). Furthermore, Rowan et al. (2021) have reported that “being online” can be experienced by some as a place of alienation and exclusion mirroring that experienced face-to-face. One important example of this is when students access media articles and reports which refer to the international students in negative ways, perpetuating negative stereotypes and racism (Paltridge et al., 2013; Yi and Jung, 2015). Added to these already detrimental dialogues, the recent comment by the Australian Prime Minister, in which he urged the international students to return home during the current COVID-19 crisis (Gibson and Moran, 2020), can only further exacerbate these negative feelings for the international students. The expression of such viewpoints in the media communicates tangible messages of not only who feels valued and who does not feel valued but also who belongs and who does not belong. Furthermore, such portrayals perpetuate negative messages and discriminatory comments across the community and the media (Robertson, 2011), reducing the sense of belonging for the international students.

Research Questions in the Present Study

Given these prevailing issues as identified through the review of the literature, this article contributes to developing new knowledge by addressing the following research questions:

• What factors impact upon the international students’ social wellbeing?

• How does online and face-to-face connectedness impact upon social wellbeing?

Theoretical Framework

The literature reviewed above emphasized the importance of focusing on the extent to which the international students, who are literally included in various school and home settings, do (or do not) feel a sense of connectedness to others, and an overall sense of belonging, in both online and face-to-face contexts. The research reported in this project draws upon theoretical resources associated with the politics of belonging to shape the investigation. Yuval-Davis (2006) proposed a framework for considering the issues of belonging called the politics of belonging, which comprises three distinct analytical levels.

“The first level concerns social locations; the second relates to individuals’ identifications and emotional attachments to various collectivities and groupings; the third relates to ethical and political value systems with which people judge their own and others’ belonging/s” (Yuval-Davis, 2006, p. 199).

In the context of education, Sumsion and Wong (2011) expanded on this framework with their cartography of belonging and applied it to early childhood education in order to argue the importance of analyzing belonging in specific contexts. They identified ten specific dimensions of belonging, as well as three axes which offered different lenses for viewing the construct of belonging. These axes were termed categorization, resistance and desire, and performativity. The axis of categorization encompasses the process of “inclusion and exclusion in numerous national, local, cultural, social and personal agendas” (Sumsion and Wong, 2011, p. 34). Categorization raises questions about who belongs and is accepted and who are instead seen as others or outsiders (Yuval-Davis, 2006.) The axis of resistance and desire examines belonging in terms of power-relations (Sumsion and Wong, 2011). Those who “belong” occupy higher social positions, while those with a lower social standing are excluded. These inequities can be opposed, however, and resistance involves contesting and challenging those notions of belonging, while desire is the hope for meaningful change. The axis of performativity describes the daily tasks and everyday actions that contribute to a sense of belonging. In essence, it is about the way that we perform belonging and “the stories people tell about themselves and others about who they are (and who they are not)” (Yuval-Davis, 2006, p. 202).

Having presented these axes, Sumsion and Wong (2011) then identified ten dimensions of belonging: emotional, social, cultural, spatial, temporal, physical, spiritual, moral/ethical, political, and legal belonging. The axes provide a framework for interpreting these ten dimensions; however, Sumsion and Wong (2011) highlighted the importance of the interplay between these dimensions and axes. According to Sumsion and Wong (2011), we can move in and out of one or all of these dimensions and axes depending on the context and the place. However, not all ten dimensions of belonging are pertinent to the current research questions and the population under investigation. Therefore, this article is guided by and focuses primarily on the social, emotional, and cultural dimensions of belonging and their relationship to fostering students’ social wellbeing. In the following section, we report on how, and in what ways, students are connected (online, face-to-face, and school connectedness), how this relates to feeling a sense of belonging (both to their Australian “homes” and to their home country), and the subsequent effect on students’ social wellbeing. The instrument draws upon the previously constructed measures of connectedness, belonging, and social wellbeing.

Method

Participants and Procedure

A convenience sample of 225 international students (93 males, 129 females, and 3 other), enrolled in years 10–12 across independent high schools in Queensland and New South Wales states, Australia, were recruited to participate in the study. The students were provided with the opportunity to participate online or in person within the presence of the researcher or the teacher (where more convenient). However, all participation was conducted using an online survey platform (Qualtrics).

Participants were eligible to participate in the study, if they were considered mature minors by Australian standards. This meant that, in order to be eligible, all students had to be over the age of 16 years. All international students who were considered as long-term students, meaning that they were in Australia for a period of longer than 1 year, were eligible to participate. Ethical approval for the study was gained by the committees of both Deakin University and Griffith University.

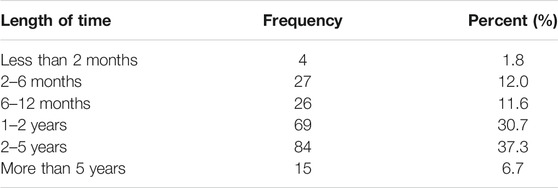

The students were asked to identify the country they considered home (which could include Australia). The most common responses were China (63.6%), Papua New Guinea (7.1%), Australia (6.7%), and Japan (5.8%). Students were asked where they usually lived before moving to Australia and while in Australia. The majority of students had lived with their family in their home country (87.1%) followed by a small number at boarding school (6.7%). While here in Australia, accommodation included homestay (42.7%), boarding school (28%), with a parent (10.2%), with their whole family (9.3%), with relatives or close friends (6.7%), and other living circumstances (3.1%). The duration students had spent in Australia is given in Table 1.

Data Analysis. The quantitative data were analyzed in a range of ways appropriate for the nature of the data and the questions being investigated. Differences between face-to-face and online friendships and connectedness were analyzed using independent samples t-tests. To analyze the research question about predictors of student social wellbeing, correlation and multiple regression were employed.

Materials

Fundamentally, the data for the current study was collected through a questionnaire with closed and open response items. The instrument was developed in conjunction with the broader project team and was responsive to the project research questions. Specifically, the questionnaire was designed to capture the international students’ sense of social wellbeing, belonging, and connectedness in online and face-to-face environments. To address these related but diverse phenomena, the instrument was developed by drawing on a range of other scales, and some items and sections were drawn directly from other instruments. The details of the questionnaire are outlined in Table 1. Additionally, demographic items were included measuring student age, time spent in Australia, and home circumstances. Thus, the instrument developed for this study was able to provide insights into the participants’ experiences. However, as the present publication is a part of a larger research program and only a subset of the data is reported here.

The specific measures analyzed and reported in the present study were as follows:

• Student social wellbeing: Items were adapted from the Social Integration and Social Acceptance subscales developed by Keyes (1988) which measure social wellbeing. These items were adapted for clarity to accommodate the adolescent reading levels. Student social wellbeing was measured using 20 items, using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree.” Example items included “You feel close to other people in your Australian community” and “You feel that people in Australia are welcoming.” Reliability for student social wellbeing was high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95).

• Home belonging: Student’s sense of belonging to their home country was measured using items adapted from Carroll et al.’s (2017) Social Connectedness Scale: Family subscale. The scale had been specifically developed for use with high school students to measure the degree to which the students felt that they belonged and were accepted. Minor wording changes were made for participant readability. This section was comprised of 11 items on a 5-point Likert scale. Example items included “We spend time together” and “I feel valued.” Reliability for the home belonging scale was high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95).

• Australian belonging: Student’s sense of belonging here in Australia was also measured using the same items from Carroll, Bower, and Muspratt’s (5-point Likert) Social Connectedness Scale: “We spend time together” and “I feel valued,” with minor wording changes to reference how they felt here in Australia. Reliability was also similarly high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94).

• Face-to-face and online connectedness to friends: The quality of student friendships and their social connections was measured using Carroll et al.’s (2017) Social Connectedness Scale: Friendship subscale. The 15 items measured the extent and quality of social connections and friendships, with example items including “I share similar interests with my friends” and “I have a friend that I trust with my deepest secrets.” The students completed one version of the scale for their face-to-face friendships and one version for online friendships and connections. Reliability was high for the face-to-face (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.97) and online versions (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96).

• School connectedness: The degree to which the students felt connected to their school community was measured using items from Carroll et al.’s (2017) Social Connectedness Scale: School subscale. School connectedness was measured using eight items, examples of which include “I like being asked to talk about my home country” and “I am treated fairly at school by other students.” Reliability was also high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92).

• Technology and social media usage: Student’s usage of technology and social media was investigated through more open questions that focused on the types of social media platforms used (e.g., Facebook, Email, etc.) and the purposes that the students used technology and Internet for (e.g., browsing the web, sharing how they are feeling, etc.). Commonplace online activities were measured using items from the Media and Technology Usage and Attitudes Scale (Rosen et al., 2013). Here, the students were asked to answer the questions “social media helps me” (e.g., maintain connections with my family, deal with loneliness, etc.). These items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale with the responses being as follows: (1) strongly disagree, (2) disagree, (3) neither agree nor disagree, (4) agree, and (5) strongly agree.

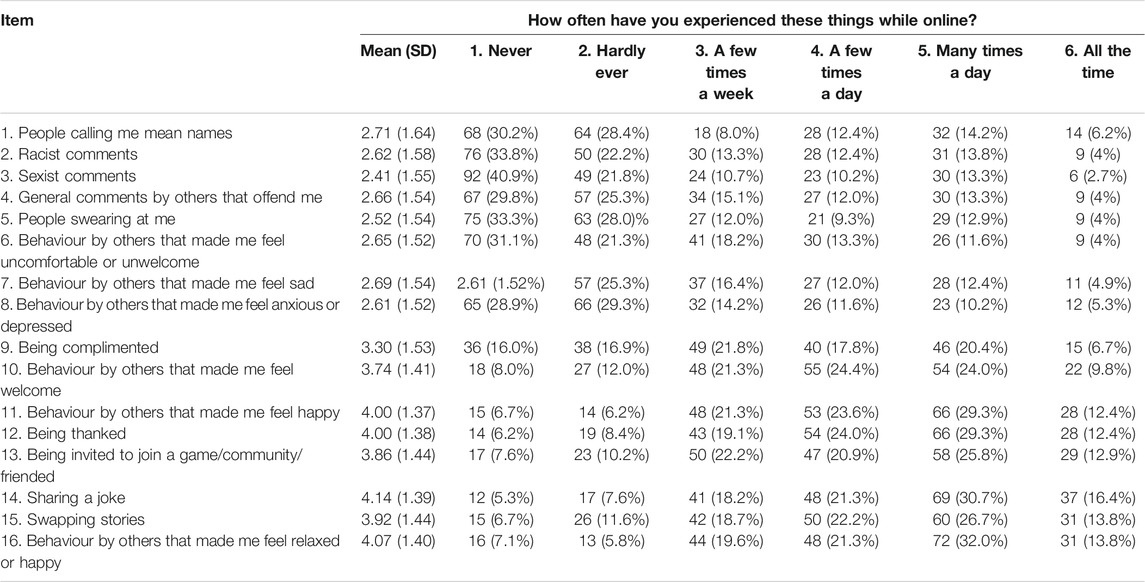

• Positive and negative online experiences: A checklist of both positive and negative online experiences was provided to measure the frequency with which the international students encountered certain behaviors. Positive experiences included behaviors that made the students feel welcomed and happy. Negative experiences included behaviors such as being called names, as well as racist or sexist comments. The responses were measured on a 6-point Likert scale, with the responses being as follows: (1) never, (2) hardly ever, (3) a few times a week, (4) a few times a day, (5) many times a day, and (6) all the time. As a guide for interpreting these responses, a mean score of 2 indicates that the behavior is hardly ever encountered, while scores of 3 and above indicate that the behavior is more frequent.

Results

The survey sought to investigate the student’s perception of connectedness to their social community in face-to-face environments and connectedness experienced online, which contribute to a student’s sense of belonging and social wellbeing. So, in reporting the results, attention is paid not only to what students do and how they connect but also the nature of these connections and how these relate to each other. Furthermore, in discussing these quantitative findings, the theoretical perspectives provided by the politics of belonging (Yuval-Davis, 2006) and the cartography of belonging (Sumsion and Wong, 2011) are employed to theoretically ground the analysis and interpretation.

Predictors of Social Wellbeing

The primary outcome of interest was students’ social wellbeing. To measure students’ social wellbeing, the sample used the entire social wellbeing scale range, with average responses falling between 1.15 and 5.00. The mean item response of 3.62 (SD = 0.60) suggests that the participants were neither extremely high nor low on social wellbeing.

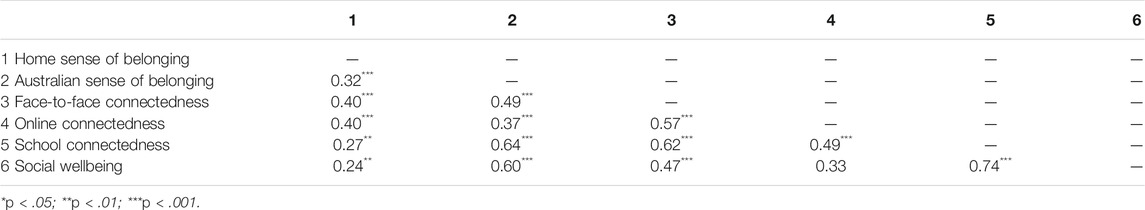

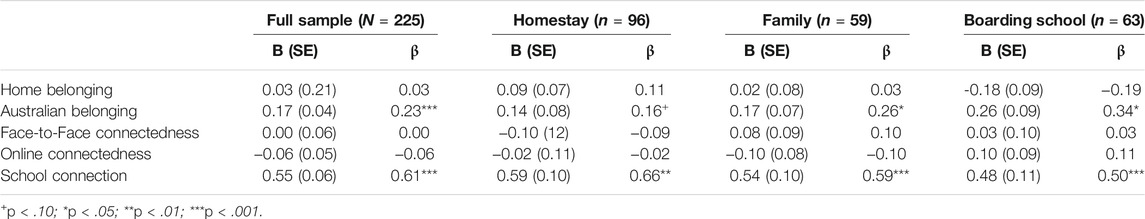

To investigate the contributions of student belonging (to their home country and in Australia) and the role that face-to-face and online connectedness played in fostering social wellbeing, a standard multiple regression was employed. Included as predictor was school connectedness, as this might also provide a buffer against stress. Table 2 presents bivariate correlations between belonging to their home country and in Australia, connectedness in face-to-face and online environments, and social wellbeing. As can be seen from the correlations, the most potent contribution to social wellbeing appeared to be their sense of Australian belonging and acceptance (r = 0.60) and their connection to their school (r = 0.74). However, all measured factors, except for online connectedness factor, showed a moderately sized positive correlation to social wellbeing.

These interpretations were upheld by the multiple regression analysis (see Table 3). When all the predictors were entered together, students’ sense of belonging and acceptance in Australia and their connection to their host school emerged as the strongest predictors of social wellbeing. These results were observed in the full sample, as well as for the three categories of student (homestay, family, and boarding school). In each case, school connection exerted a marginally stronger effect than belonging and acceptance in Australia.

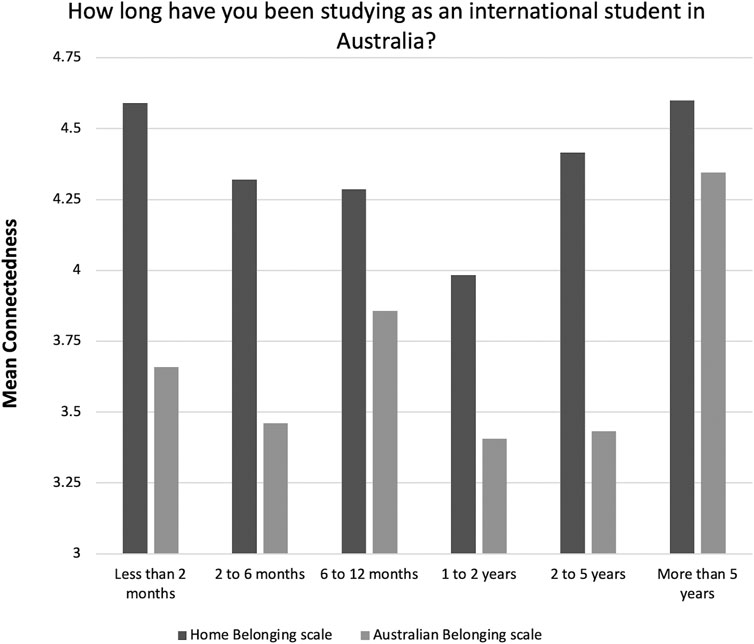

Changes in Student Social Wellbeing at Different Points in Time

Figure 1 shows students’ sense of belonging to their home country and in Australia relative to the amount of time they had been in Australia, showing a steady decline in their sense of home belonging in the initial year upon arrival to Australia, followed by a steady increase after 2 years of being in Australia. Interestingly, their sense of belonging in Australia declines in the first 6 months after arriving to Australia. After being in Australia between 6 and 12 months, their sense of belonging in Australia increases. However, their sense of Australian belonging drops again to the lowest point, after being in Australia between 1 and 2 years. After being in Australia between 2 and 5 years, there is almost no change in their sense of belonging in Australia. However, only after the 5-year period does students’ sense of belonging in Australia rise again and approach that of their country of birth.

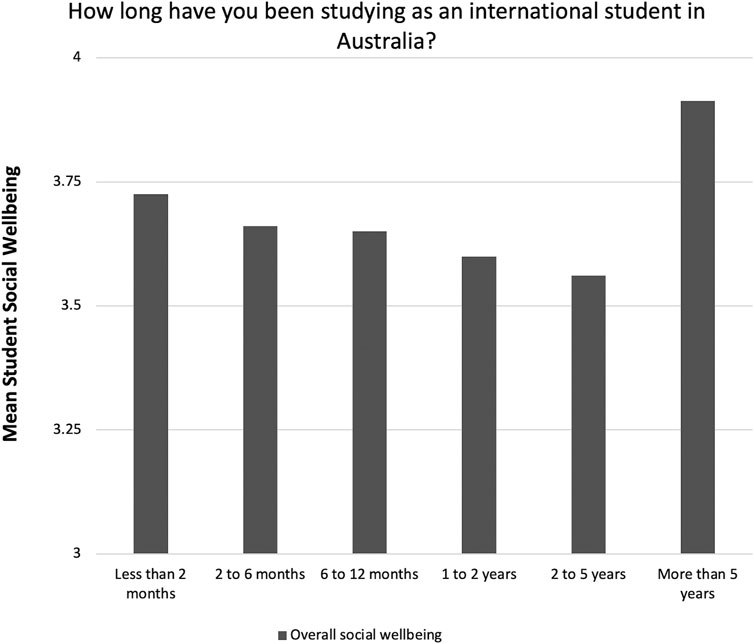

Figure 2 presents differences in the students’ social wellbeing vis-à-vis the time they have spent in Australia. This data is particularly concerning, as it shows a gradual but fairly steady decline in self-reported social wellbeing at different points in time, with the largest decline for students studying in Australia for 2 to 5 years. More hopefully though, students who have been studying in Australia for 5 years or longer report a substantially higher level of social wellbeing—even higher than that for commencing students.

Internet and Social Media Usage of the International Students

The international students used the Internet and social media for a variety of tasks, and on any given day they would generally browse the web, search for information, use apps, listen to music, watch video clips, read emails, and use social media. These do not appear to differ from the typical pastimes of adolescents. However, the majority of the students also watched English language television shows and movies on at least a weekly basis (64.9%), as well as television and movie content from their home country (68.4%), which included watching shows in their first language. In addition, the students also reported that they used the Internet in order to make voice and video calls to others on at least a weekly basis (71.1%).

What was particularly interesting was the fact that a considerable number of students reported using social media for emotional expression by making a status update or blog entry on at least a weekly basis (63.3%), to cheer themselves up (68.4%), to cheer up other international students (72.8%), or to vent or voice their concerns about the problems they are experiencing (62.9%).

The social media landscape is rapidly expanding, with new forms of social media emerging annually. As the medium used for communication may be varying over time, the frequency of use of each of the popular mediums highlighted that email was used extensively (70.4%), with also strong use of Instagram (66.1%), WeChat (64.3%), Facebook (30.2%), and video chat (29.7%). The follow-up survey questions sought to identify whether there were different patterns of social media usage with friends and peers, as well as those used with family.

Online Experiences of the International Students

Although there were no significant and strong statistical links between students’ social wellbeing, sense of belonging, and online connections, recognizing that the students encounter both positive and negative experiences online, we asked the students to report how frequently they experienced both good and bad things while online. The students reported online experiences on a 6-point Likert scale (see Table 4). All positive experiences scored higher than the scale midpoint of 3, while negative experiences were generally below, indicating that they were less frequently encountered. Frequencies of responses have been given so that the reader can see the percentage of the students reporting negative experiences. The one exception was behavior by others which made the students feel anxious or depressed, which appeared more common (M = 3.3). What is important to note here is the fact that while many reported positive experiences, there were also a sizeable number of students who reported negative experiences, and it is crucial that the aggregating effect of the summarized data does not diminish the negative experiences of some participants.

Connectedness in Face-to-Face and Online Environments

The students’ self-reported measures of connectedness were compared to see whether the international secondary students reported a difference between their face-to-face connectedness and online connectedness across the survey items. For three of the measures of connectedness, there was a significant difference between the online and face-to-face connections. These three items were as follows:

“my friends understand me”: t (224) = 2.16, p = 0.002, and d = 0.28; “my friends really listen to what I have to say”: t (224) = 2.04, p = 0.042, and d = 0.27; and “I have a friend that I trust with my deepest secrets”: t (224) = 3.23, p = 0.001, and d = 0.43. For these specific items, the students reported having higher connectedness with their online friends than they did with their friends in Australia with whom they connect face-to-face.

Discussion

Considering the results outlined above, in this final section, we now provide a discussion of the findings, structured by the study’s research questions outlined previously.

Research Question 1

• What factors impact upon the international students’ social wellbeing?

When looking at the extent to which a sense of belonging and connectedness predicts the international students’ social wellbeing, the results of the multiple regression indicated that Australian belonging and school connectedness were the most important predictors. When the students felt like they belonged and were accepted in Australia, they reported a greater sense of social wellbeing. In addition, the findings also revealed that when the students felt that they were connected to their school community, they also reported a greater level of social wellbeing. This is consistent with the position of Sumsion and Wong (2011), where social connectedness is linked to a sense of belonging, as indicated in the cartography of belonging where they state “social belonging is associated with group membership, affinity and attachments beyond the emotional attachments in close networks of family and friends” (p. 42). They further emphasized the importance of social belonging and that of being part of a community and being able to contribute to it.

Although there were still significant bivariate correlations between online connectedness, home belonging, and face-to-face connectedness (indicating their importance), the multiple regression showed that they had a much smaller impact than the above-mentioned predictors. This does not negate their importance (for example, in our sample, we found that online connections are used for emotional expression and regulation) but rather that Australian belonging and school connectedness explained the greater degree of social wellbeing. This has important implications, as the way international students are treated in the community and schools is an aspect which schools, other institutions, and the wider community have some control over. Meanwhile there is less control once the students engage in online activity. Moreover, the school community was the strongest predictor (see Table 5), as it had a greater effect compared to even belonging in Australia. This is an important finding as it draws attention to the fact that schools can indeed make very meaningful contributions to the social wellbeing of the international students in their care, should they ensure to provide appropriate resources and care to address this. This is further discussed in the implications section of this discussion.

We also investigated whether there were differences in the nature of the international students’ online and face-to-face friendships. In general, the students reported similar quality friendships online and face-to-face. Therefore, there was no particular preference for online or face-to-face friendships. However, there were three items where the international students reported having stronger online friendships: for the items “my friends understand me,” “my friends really listen to what I have to say,” and “I have a friend that I trust with my deepest secrets.” The direction of the difference was unanticipated, as generally adolescents report greater quality of face-to-face friendships (Reich et al., 2012). One explanation could be the fact that vulnerable international students who lack meaningful peer connections are forced to seek them out online, but it is not clear whether these were established online connections from their home country or whether they were seeking out new ones online. This is a line of questioning that could be explored in future studies.

In addition, it was clear that these online and face-to-face friendships provided significant support for the international students during their time in Australia, with moderately sized significant bivariate correlations between friendship connections and the students’ social wellbeing. However, the results of the multiple regression highlighted that home belonging and school connectedness played an even greater role in fostering the students’ social wellbeing than their face-to-face and online connectedness. It may be the case that successful formation of these peer friendships leads indirectly to social wellbeing through the pathway of belonging (Berry, 2005; Cho and Haslam, 2009). It also suggests that achieving a positive sense of connection to the school environment and fostering a sense of belonging to the Australian community are vital for achieving positive student outcomes. Undoubtedly, the acculturation process is a period of high stress (Yeh and Inose, 2003; Ye, 2006) but close connections with schools can be a protective factor for the international students during this time. This research finding differs somewhat from previous research, which had highlighted the peer and social connections as being more important for the international students (Hendrickson et al., 2011; Hommes et al., 2012; Glass, 2014). When the students feel like they really belong to the school and to the Australian community, they report much greater levels of social wellbeing. This suggests one way that the schools hosting the international students can have a powerful contribution to the students’ social and emotional wellbeing while under their care. It prompts us to consider availability of access to mental health and other services for the international students, particularly those facing language and cultural barriers. It also suggests a direction for future researchers to follow, as this is currently under-researched.

Moreover, when examining whether there were changes in the students’ sense of belonging (both to their home country and to the Australian community), an unexpected finding revealed that the students in the initial two months report comparatively high sense of belonging. However, their sense of belonging to their home country drops precipitously after this period and generally declines in the first two years. This coincides with a general declining trend in the overall students’ social wellbeing (see Figure 2). While we cannot establish causation from a correlational design, it is quite consistent with the literature on the pressures of acculturative stress and its negative effect on social wellbeing which has been previously documented (Berry, 2005; Ye, 2006). The students also report an initial decline in their sense of belonging in Australia which rebounds after six months (see Figure 1). However, it again drops considerably after 1–2 years of being in Australia and remains low until eventually climbing in those students who remain in Australia for five years or longer. While we cannot draw any firm conclusions as to why the declines occur at this time, we can hypothesize why these may be occurring. Great efforts are generally undertaken to make the international students feel welcome upon arrival, but after this initial “welcoming” such efforts possibly reduce as students “appear” to be fitting in. However, our research has identified that this is actually a critical period for the international students as they experience not only a reduced sense of belonging to home but also a reduced sense of belonging here in Australia. It is at this time that further support is needed for the students as they navigate this difficult period during which their overall social wellbeing also declines. Real and concerted efforts to support these students are required, and they need to be genuine rather than unintentionally tokenistic.

Research Question 2

• How does online and face-to-face connectedness impact upon social wellbeing?

While no statistically significant finding was revealed between the international students’ online connectedness, social wellbeing, and belonging, we did find that the international students reported experiencing greater positive online and social media experiences than negative ones. This would be consistent with other researches on Australian high school students indicating online and social media experiences to be normative for students in this age range (Allen et al., 2014). However, we did note that some behaviors such as being sexist or racist or offensive comments were still reported by the students in the sample and, of course, the positive experiences do not negate these negative ones, and “online” is not always a welcoming community as it can also be a place of occasional exclusion (as noted by Sumsin and Wong’s (2011) axis of categorization).

Overwhelmingly though, the social and emotional benefits of online and social media platforms are such that we would caution against restricting access to the social media platforms or other forms of connecting to family and friends. Alfarhoud et al. (2016) argued that this takes on an increasing importance for the international students though as it fosters a sense of connection with their home country and existing support networks (friends, family, and culture). It is also consistent with the emphasis Sumsion and Wong (2011) place on social and emotional connections, as online and social media platforms allow them to still communicate with those that are back in their home country. Also identified in our results were the ways in which the students used social media for emotional expression, as well as to console other international students experiencing similar stresses and hardships. Thus, access to social media is important not only for friendship formation but also for emotional regulation and seeking support when needed. This is consistent with the previous studies that have highlighted how provision of access to social media is essential to adolescents under stress (Egan and Moreno, 2011; Michikyan et al., 2015). From the perspective of Sumsion and Wong (2011) and, more specifically, the dimensions of social and emotional belonging, these findings demonstrate the degree to which the online activity facilitates social and emotional belonging for the international students: it is able not only to maintain existing social ties but also to facilitate emotional expression and help the international students find supportive and caring social relationships online when they are lacking in face-to-face relationships. Sumsion and Wong (2011, p.42) noted that this emotional belonging “is associated with acceptance” and goes beyond the group membership and affinity provided by social belonging. These perspectives are particularly important for the schools and policy makers to be mindful of, as they often impose arbitrary decisions on the amount, and type, of access to the Internet, but they lack the perspective of an isolated international student studying in a different country.

In addition, overall, online and social media experiences appear to be a protective factor for the students, with the only negative behavior reported as being quite frequent being “behaviour by others that made me feel anxious or depressed.” However, the specific behaviors were not identified; follow-up interview questions in future studies could focus on trying to identify more specific examples of the types of behavior that contributes towards these feelings. We also note that all students must be supported if they have negative online experiences. In our sample, even the minority that note negative, and often daunting, experiences online highlight the tension between the benefits and risks of online activity for adolescents. We also know that one poor experience among many good experiences can cause significant harm. This cannot be lost in the aggregation of the data.

Furthermore, we found that the students use a range of online and social media platforms considerably and for a variety of purposes including maintaining language and cultural ties with their home country in the form of music, television, and movie content, as well as maintaining social connection with friends and family abroad to reduce feelings of loneliness and isolation. A research finding though for this population was the high degree to which the students used online connection for emotional expression, with the majority of students making status updates or blog entries (68.4%) on at least a weekly basis, to console or to cheer up other international students (72.8%), or to voice concerns about the problems they are experiencing (62.9%). The majority of international students reported using these as an outlet for emotional expression publicly (Best et al., 2014), which may act as a buffer for the stresses they experience, as well as a way to elicit social support (Egan and Moreno, 2011). Importantly, they also used them to console other international students—a behavior which has not been previously identified. Given that, for many, there are restrictions on the amount or even the availability of access to social media for students, this may have some implications which are addressed further in the implications section of the discussion.

We also note that the online connections were rated significantly higher than the face-to-face connections for the three items surrounding emotional expression with friends. While educators may have concerns about the appropriateness of access to social media, for this particular subgroup of international students, it highlights just how important access to social media is for their social and emotional wellbeing. This is consistent with Sumsion and Wong’s (2011) social, emotional, and cultural dimensions of belonging, as well as the axis of performativity, where students “perform” belonging (Sumsion and Wong, 2011), in order to foster a greater sense of belonging. Furthermore, this importance they place on online connectedness and social media further emphasizes the strong interplay between the performance of belonging and how the online engagements can contribute towards their social, emotional, and cultural belonging.

Limitations of the Study and Areas for Further Research

It is important to acknowledge here that this article seeks to provide an overview of the findings that have emerged from the first custom built survey of international high school students’ social wellbeing. Our focus is thus on presenting the findings and identifying the key areas of interest and concern. Further articles will explore some of the most pressing issues in more depth. We also acknowledge that the cross-sectional design of the study provides a “snapshot” in time of students’ belonging, connectedness, and social wellbeing across the students who had been in Australia for as little as two months to as long as five years or longer. As it is a cross-sectional study, and we have not really tracked over time to clearly show changes, it would be desirable to include more responses from those who have been in Australia for a longer period or to track over time. Furthermore, as somewhat of a convenience sample, it cannot necessarily be assumed that the decline observed in connectedness and social wellbeing over time generalizes more broadly to other international high school students. That said, the sample size was good, and it provides a starting point for future studies to investigate this effect longitudinally.

Conclusion and Recommendations

As identified in previous research, the social connections are of utmost importance to students, and the absence of forming strong social connections in school can have detrimental effects on students’ wellbeing (Keyes, 1998; Gomes et al., 2015; Alharbi and Smith, 2019; Bharara et al., 2019). Thus, this focus on factors that impact upon social wellbeing takes on even greater importance in relation to the international students who are studying away from home and are in need of forming new social ties such as friends, peers, and their school and local community. Therefore, it is not surprising that this research has found that not only are the elements of Sumsion and Wong (2011) social dimension identified as those that are most important when it comes to the international students’ sense of belonging, but also the emotional dimension, as research has shown, is very strongly connected to belonging and social wellbeing (Tran and Gomes, 2016).

As this research has found, the students’ experiences of belonging are shaped by many factors, including face-to-face and online connections to friends and family. The contribution of belonging and connection was strongly associated with greater students’ social wellbeing. Furthermore, this study has found that a sense of belonging to the Australian community and a sense of connection to the international students’ host school were identified as the most powerful contributions to the students’ social wellbeing, which generally declined the longer the students remained in Australia. Therefore, and not surprisingly, it is recommended that the international high school students receive greater support from the schools as well as the Australian community in making them feel not just welcome but also an accepted part of the community. Simply being included is not the same as feeling a genuine sense of belonging and acceptance. Fostering a genuine sense of belonging to the Australian community and developing a strong connection to host schools can play a pivotal role in improving the social wellbeing of the students. The international students are particularly vulnerable after the first six months of arrival in Australia, and additional interventions aimed at helping them feel more welcome and accepted are crucial; but these need to be genuine and not unintentionally tokenistic. Overwhelmingly, the benefits and the affordances provided by access to social media and online platforms outweigh the risks, but we also note that for some students they can still experience these online communities as hostile and excluding, for example, racist, sexist, and offensive comments. These also do not negate the importance of creating warm, supporting face-to-face environments for the international students here in Australia.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Griffith University and Deakin University. Participants provided informed consent by completing and submitting the survey responses.

Author Contributions

AH and LR contributed to the conception and design of the study. AH conducted the data collection, carried out the analysis, and wrote the draft of the manuscript. PG provided expert feedback on the analysis of data. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision and read and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This project has been supported by funding from the Australian Research Council Discovery Grant Scheme (ARC DP160103181), by a Griffith University Doctoral Scholarship, by the Griffith Institute for Educational Research, and by the School of Education and Professional Studies at Griffith University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The data for this article derives from the Australian Research Council Discovery Project: International students in secondary schools (ARC DP160103181). The research team comprises Chief Investigators J. Blackmore, C. Beavis, L. Tran, and L. Rowan; Partner Investigator C. Halse; Research Fellows T. Mccandless, C. Mahoney, and C. Moore; and doctoral candidates T. Hoang, M. Chou-Lee, and A. Hurem.

References

Akhtar, M., and Kroener-Herwig, B. (2017). Coping Styles and Socio-Demographic Variables as Predictors of Psychological Well-Being Among International Students Belonging to Different Cultures. Curr. Psychol. 38 (3), 618–626. doi:10.1007/s12144-017-9635-3

Alfarhoud, Y. T., Alahmad, B., Alqahtani, L., and Alhassan, A. (2016). The Experience of International Student Using Social media during Classes. Int. J. Educ. 8 (2), 32. doi:10.5296/ije.v8i2.9224

Alharbi, E., and Smith, A. (2019). Studying-away Strategies: A Three-Wave Longitudinal Study of the Wellbeing of International Students in the United Kingdom. Eur. Educ. Res. 2 (1), 59–77. doi:10.31757/euer.215

Allen, K. A., Ryan, T., Gray, D. L., McInerney, D. M., and Waters, L. (2014). Social media Use and Social Connectedness in Adolescents: The Positives and the Potential Pitfalls. Aust. Educ. Develop. Psychol. 31 (1), 18–31. doi:10.1017/edp.2014.2

Antonsich, M. (2010). Searching for Belonging - an Analytical Framework. Geogr. Compass 4 (6), 644–659. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2009.00317.x

Arslan, G. (2017). Social Exclusion, Social Support and Psychological Wellbeing at School: A Study of Mediation and Moderation Effect. Child. Ind. Res. 11 (3), 897–918. doi:10.1007/s12187-017-9451-1

Atri, A., Sharma, M., and Cottrell, R. (2007). Role of Social Support, Hardiness, and Acculturation as Predictors of Mental Health Among International Students of Asian Indian Origin. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 27 (1), 59–73. doi:10.2190/iq.27.1.e

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2020). International Trade in Goods and Services. Australia. Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/5368.0 (Accessed August 14, 2020).

Australian Catholic University (2018). Scoping Study into Approaches to Student Wellbeing. Available at: https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/appendix_1_literature_review.pdf (Accessed July 7, 2020).

Australian Government (2018a). Australian Student Wellbeing Framework. Available at: https://www.education.gov.au/national-safe-schools-framework-0 (Accessed September 11, 2019).

Australian Government (2018b). End of Year Summary of International Student Data 2018. Canberra: Australia. Available at: https://internationaleducation.gov.au/research/International-Student-Data/Documents/MONTHLY%20SUMMARIES/2018/International%20student%20data%20December%202018%20detailed%20summary.pdf (Accessed September 11, 2019).

Australian Government (2015). National Strategy for International Education. Available at: https://internationaleducation.gov.au/International-network/Australia/InternationalStrategy/Documents/Draft%20National%20Strategy%20for%20International%20Education.pdf (Accessed September 11, 2019).

Baak, M. (2018). Racism and Othering for South Sudanese Heritage Students in Australian Schools: Is Inclusion Possible? Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 23 (2), 125–141. doi:10.1080/13603116.2018.1426052

Bamford, M. (2020). International Students Face Life-Changing Decisions as COVID-19 Takes its Toll. ABC Radio Sydney. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-05-12/coronavirus-impact-on-international-students/12224752 (Accessed May 17, 2020).

Barry, M. M., Clarke, A. M., and Dowling, K. (2017). Promoting Social and Emotional Well-Being in Schools. Health Educ. 117 (5), 434–451. doi:10.1108/he-11-2016-0057

Baumeister, R. F., and Leary, M. R. (1995). The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117 (3), 497–529. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Berry, J. W. (2005). Acculturation: Living Successfully in Two Cultures. Int. J. Intercultural Relations 29 (6), 697–712. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013

Best, P., Manktelow, R., and Taylor, B. (2014). Online Communication, Social media and Adolescent Wellbeing: A Systematic Narrative Review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 41, 27–36. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.001

Bharara, G., Duncan, S., Jarden, A., and Hinckson, E. (2019). A Prototype Analysis of New Zealand Adolescents' Conceptualizations of Wellbeing. Intnl. J. Wellbeing 9 (4), 1–25. doi:10.5502/ijw.v9i4.975

Carroll, A., Bower, J. M., and Muspratt, S. (2017). The Conceptualization and Construction of the Self in a Social Context-Social Connectedness Scale: A Multidimensional Scale for High School Students. Int. J. Educ. Res. 81, 97–107. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2016.12.001

Chervonsky, E., and Hunt, C. (2019). Emotion Regulation, Mental Health, and Social Wellbeing in a Young Adolescent Sample: A Concurrent and Longitudinal Investigation. Emotion 19 (2), 270–282. doi:10.1037/emo0000432

Cho, Y.-B., and Haslam, N. (2009). Suicidal Ideation and Distress Among Immigrant Adolescents: The Role of Acculturation, Life Stress, and Social Support. J. Youth Adolescence 39 (4), 370–379. doi:10.1007/s10964-009-9415-y

Chu, P. S., Saucier, D. A., and Hafner, E. (2010). Meta-analysis of the Relationships between Social Support and Well-Being in Children and Adolescents. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 29 (6), 624–645. doi:10.1521/jscp.2010.29.6.624

Department of Education, Skills and Employment (2020). International Student Data: Monthly Summary – May 2020. Australian Government, Canberra. Available at: https://internationaleducation.gov.au/research/International-Student-Data/Documents/MONTHLY%20SUMMARIES/2020/May%202020%20MonthlyInfographic.pdf (Accessed July 13, 2020).

Dovchin, S. (2020). The Psychological Damages of Linguistic Racism and International Students in Australia. Int. J. Bilingual Educ. Bilingualism 23 (7), 804–818. doi:10.1080/13670050.2020.1759504

Egan, K. G., and Moreno, M. A. (2011). Prevalence of Stress References on College Freshmen Facebook Profiles. CIN: Comput. Inform. Nurs. 29 (10), 586–592. doi:10.1097/ncn.0b013e3182160663

Espinoza, G., and Juvonen, J. (2011). The Pervasiveness, Connectedness, and Intrusiveness of Social Network Site Use Among Young Adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behav. Soc. Networking 14 (12), 705–709. doi:10.1089/cyber.2010.0492

Fahd, K., and Venkatraman, S. (2019). Racial Inclusion in Education: An Australian Context. Economies 7 (2), 27. doi:10.3390/economies7020027

Finger, G. (2017). “Digital Technologies and Junior Secondary: Learning with and about Digital Technologies,” in STEM Education in the Junior Secondary, 197–219. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-5448-8_10

Gareis, E. (2012). Intercultural friendship: Effects of home and Host Region. J. Int. Intercultural Commun. 5 (4), 309–328. doi:10.1080/17513057.2012.691525

Gibson, J., and Moran, A. (2020). As Coronavirus Spreads, 'it's Time to Go home' Scott Morrison Tells Visitors and International Students. ABC News Online. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-03/coronavirus-pm-tells-international-students-time-to-go-to-home/12119568.

Glass, C. R. (2014). International Student Adjustment to College: Social Networks, Acculturation, and Leisure. J. Park Recreation Adm. 32 (1), 7–25.

Glass, C. R., and Westmont, C. M. (2014). Comparative Effects of Belongingness on the Academic success and Cross-Cultural Interactions of Domestic and International Students. Int. J. Intercultural Relations 38, 106–119. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.04.004

Gomes, C., Berry, M., Alzougool, B., and Chang, S. (2014). Home Away from home: International Students and Their Identity-Based Social Networks in Australia. J. Int. Students 4 (1), 2–15. doi:10.32674/jis.v4i1.493

Gomes, C., Chang, S., Jacka, L., Coulter, D., Alzougool, B., and Constantinidis, D. (2015). “Myth Busting Stereotypes: The Connections, Disconnections and Benefits of International Student Social Networks,” in 26th ISANA International Education Association Conference, Melbourne, 1–4.

Greenhow, C., Robelia, B., and Hughes, J. E. (2009). Learning, Teaching, and Scholarship in a Digital Age. Educ. Res. 38 (4), 246–259. doi:10.3102/0013189x09336671

Halse, C. (2018). Interrogating Belonging for Young People in School. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Hamm, M. P., Newton, A. S., Chisholm, A., Shulhan, J., Milne, A., Sundar, P., et al. (2015). Prevalence and Effect of Cyberbullying on Children and Young People. JAMA Pediatr. 169 (8), 770. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0944

Harvey, T., Robinson, C., and Welch, A. (2017). ‘The Lived Experiences of International Students Who’s Family Remains at Home’. J. Int. Students 7 (3), 748–763. doi:10.5281/zenodo.570031

Harwood, S. A., Mendenhall, R., Lee, S. S., Riopelle, C., and Huntt, M. B. (2018). Everyday Racism in Integrated Spaces: Mapping the Experiences of Students of Color at a Diversifying Predominantly white Institution. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 108 (5), 1245–1259. doi:10.1080/24694452.2017.1419122

Hendrickson, B., Rosen, D., and Aune, R. K. (2011). An Analysis of friendship Networks, Social Connectedness, Homesickness, and Satisfaction Levels of International Students. Int. J. Intercultural Relations 35 (3), 281–295. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.08.001

Hommes, J., Rienties, B., De Grave, W., Bos, G., Schuwirth, L., and Scherpbier, A. (2012). Visualising the Invisible: A Network Approach to Reveal the Informal Social Side of Student Learning. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 17 (5), 743–757. doi:10.1007/s10459-012-9349-0

Ito, M., Baumer, S., Bittanti, M., Boyd, D., Cody, R., Herr-Stephenson, B., et al. (2010). Hanging Out, Messing Around, and Geeking Out: Kids Living and Learning with New media. Cambridge/London: MIT Press.

Lawson, C. (2012). Student Voices: Enhancing the Experience of International Students in Australia. Canberra: Australian Education International. Available at: http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/219558 (Accessed March 2, 2020).

Lee, J. J., and Rice, C. (2007). Welcome to America? International Student Perceptions of Discrimination. High Educ. 53 (3), 381–409. doi:10.1007/s10734-005-4508-3

Lee, R. M., and Robbins, S. B. (1995). Measuring Belongingness: The Social Connectedness and the Social Assurance Scales. J. Couns. Psychol. 42 (2), 232–241. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.42.2.232

Li, S., and Zizzi, S. (2018). A Case Study of International Students' Social Adjustment, Friendship Development, and Physical Activity. J. Int. Students 8 (1), 389–408. doi:10.32674/jis.v8i1.171

Lowe, D. (2015). Australia's Colombo Plans, Old and New: International Students as Foreign Relations. Int. J. Cult. Pol. 21 (4), 448–462. doi:10.1080/10286632.2015.1042468

Mansouri, F., and Jenkins, L. (2010). Schools as Sites of Race Relations and Intercultural Tension. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 35 (7), 93–108. doi:10.14221/ajte.2010v35n7.8

Marginson, S. (2007). Global Position and Position Taking: The Case of Australia. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 11 (1), 5–32. doi:10.1177/1028315306287530

Marginson, S., Nyland, C., Sawir, E., and Forbes-Mewett, H. (2010). International Student Security. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511751011

McCarthy, J. (2013). “Online Networking: Integrating International Students into First Year University through the Strategic Use of Participatory Media,” in Multiculturalism in Technology-Based Education: Case Studies on ICT-Supported Approaches (Salamanca, Spain: IGI Global), 189–210. doi:10.4018/978-1-4666-2101-5.ch012

McFaul, S. (2016). International Students' Social Network: Network Mapping to Gage Friendship Formation and Student Engagement on Campus. J. Int. Students 6 (1), 1–13. doi:10.32674/jis.v6i1.393

Meadows, E. (2011). “From Aid to Industry: a History of International Education in Australia,” in Making a Difference: Australian International Education (Kensington, N.S.W.: University of New South Wales Press), 50–80. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/1 0536/DRO/DU:3004501 8 (Accessed February 19, 2020).

Michikyan, M., Subrahmanyam, K., and Dennis, J. (2015). Facebook Use and Academic Performance Among College Students: A Mixed-Methods Study with a Multi-Ethnic Sample. Comput. Hum. Behav. 45, 265–272. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.033