- Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Study of Salerno, Baronissi, Italy

Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic has inevitably transformed face-to-face teaching to remote teaching (e-learning or blended) which has had psychological and social impacts on the mental health of university students.

Object: In this study, we surveyed university students with disabilities and specific learning disabilities (SLDs) on their perceptions of and satisfaction with emergency remote teaching (ERT) during the lockdown phase (March–April 2020) and following restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We compared the responses of students with disabilities and SLDs with those of normotypical students.

Methodology: A questionnaire was completed remotely: five items on the ERT were designed as ad hoc questions and five items were taken from the Short Form 12 Health Survey (SF-12) to evaluate physical and mental self-perceived health. There was a total of 163 students surveyed, 67 students with disabilities and/or SLDs and 96 normotypical students.

Results and Conclusion: Students with disabilities and SLDs were more satisfied with remote teaching than the normotypical students. In fact, only 22% of the students with disabilities or SLDs indicated that they were dissatisfied with the teaching method used due to difficulties encountered, including those related to a weak technological infrastructure. We found that among all the students, important social and emotional aspects emerged as a consequence of the absence of interactions and relationships with both faculty and peer groups.

Introduction

With the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been inevitable and ongoing psychological and social impacts on the mental health of the population (Liu et al., 2020; Marinaci et al., 2020), which necessitates immediate interventions. In particular, the academia in Italy has been affected by the radical freezing of in-person teaching activities.

The transformation from face-to-face to remote teaching under anxious and sudden conditions linked to the outbreak of the pandemic (UNESCO, 2020) was immediate, even in non-telematic university contexts, which are different from those where teaching has been practiced for some time in online (e-learning) or mixed (blended) teaching formats (Pursel et al., 2016; Shale, 2002) or different from real telematic universities (Bates, 2020). The sudden and generalized transformation from the prevailing model of face-to-face teaching to the emergency remote teaching (ERT) modality, coinciding with the start of the second academic semester, was imposed to safeguard the right to study and perform ordinary teaching and research activities. However, the different representations of learning conveyed by the two different models were not considered (Coppola et al., 2015; Marsico, 2018; Teixeira et al., 2019).

A topic of particular relevance that was amplified by the foreclosure of in-person teaching activities is the impact of ERT on students with disabilities and specific learning disabilities (SLDs), which is a steadily growing population in higher education both in Italy and internationally (Pavone, 2018). Under normal conditions, this population is already considered more fragile and demanding (Herburger, 2020).

Bao (2020), who interviewed students about online study, highlighted their concerns especially about Internet connectivity and increased problems with asynchronous teaching. Liu et al. (2020) revealed difficulties related to distance learning, especially due to the weakness of the technological infrastructure of online teaching due to the inexperience of teachers, and the home environment experienced as intrusive to privacy.

In several recent studies (Zhang et al., 2020; Thelwall and Levitt, 2020; Favieri et al., 2020), increased psychological distress associated with social distancing was found in students with and without a disability compared with a normotypical group. Additional study (Toquero, 2020) showed that youth with psychosocial disabilities have suffered more in terms of their mental health during the crisis period. The greatest difficulties found on the educational side are related to accessibility to online learning or communication tools (Zhang et al., 2020). Liu et al. (2020) also noted difficulties related to ERT, mainly due to the weakness of the online teaching technology infrastructure, teachers’ inexperience, and the home environment lacking privacy.

Thus, information gained from surveys on this ERT plan can act as a reference for in-depth reflections on the strengths and potential as well as the negative aspects of the distance model for university students, including those with disabilities and/or SLDs.

Hypothesis

We hypothesize that, although the problems related to the COVID-19 pandemic have compromised everyone’s psychophysical level, ERT has provided support for students with disabilities through technological tools and the presence, albeit virtual, of online classes.

Aim

We aim at determining the perceptions of university students toward online learning that was implemented in all Italian universities during the COVID-19 lockdown.

Our objective is to highlight the perceptions of students on their experience with ERT and dedicated services (lectures, exams, and tutoring) delivered during the lockdown phase (March–April 2020) in order to monitor the psychological health of students and to understand the strengths and weaknesses of remote teaching. The responses of students with disabilities and SLDs were compared with those of a group of developmentally normotypical students.

Methods

Procedure

A descriptive and qualitive study was conducted at the end of April 2020, after the students of all institutions had at least 2 months of experience with online learning.

The questionnaire was administered to students enrolled in the Degree Courses of the University of Salerno through an e-mail invitation containing the link to be accessed on the Survey Monkey online platform. After having read and consented to the informed consent that explained the aim of the survey and the processing of personal data, made anonymous, each student accessed the sections to be completed in the questionnaire.

During the national lockdown that occurred in March 2020, the University of Salerno guaranteed material support to all students by delivering PCs and tablets with Internet connection to guarantee similar access to ERT.

Instrument

The questionnaire used in this study consisted of n°10 questions divided into two sections. The first section collected informations about the following anamnestic and socio-demographic characteristics of the participants, such as age (years), sex (male, female), degree course and possible diagnosis of disabilities and/or SLDs. The second section consists of n°5 open-ended and so-called “filter” questions that investigate the perception of the quality of the ERT and related activities and n°5 items taken directly from the Italian version of the Short-Form Health Survey 12-SF-12 (Ware et al., 1995), an abbreviated version of the SF-36, a generic indicator of the quality of life and evaluates the subjective perception of the individual in relation to the concept of health, understood as biopsychosocial well-being and exhibits good psychometric properties in different cohorts of patients (e.g., general and disease-specific populations) (White et al., 2018).

The response modalities were mixed and included dichotomous (yes/no) questions, multiple-choice questions using both 4- and 5-point Likert-type response scales (“always” to “never” and “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”), and an open-ended response question (item #9).

The online questionnaire was created according to the CHERRIES statement (Eysenbach, 2012).

Participants

Data were collected from all Degree Courses, such as Medicine and surgery, Engineering, Communication sciences, Education sciences, Law, and Economics.

There were a total of 163 participants, of which 67 had disabilities and/or SLDs (M = 36,4%; Mean age = 23 years; SD = 3,5) and 96 had normotypical development (M = 46,9%; Mean age = 25,06 years; SD = 3,74). Specifically, of the students with special education needs, 84% had disabilities and 16% had learning disabilities.

Data Analysis

Our study is part of the “post-event” qualitative feedback survey activities. Data collected were extracted from Survey Monkey by creating a spreadsheet and imported to SPSS (IBM v.26 INC. Chicago, IL, United States). A preliminary check analysis was performed to assess possible errors, outliers, and missing data.

Frequencies, means, and standard deviations were calculated through descriptive statistics and were used to describe the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents and the elements of the questionnaires.

As a preliminary analysis, the assessment of associations between socio-demographic characteristics and SF-12 was conducted using multivariate regression models expressing standardized estimates (β) and the related 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Responses to the questionnaire were compared with percentages to detect the presence and/or absence of the variables being examined and show the number of students who have given a specific answer compared to the total number of the sample who answered the question.

The SF-12 includes both categorical and discrete elements, for which the maximum likelihood and the least squared weighted estimator of adjusted mean and variance has been adopted. The CFA determines how well the theoretical scale model fits the empirical data (structure validity or dimensionality). Following the approach of previous studies (Ware et al., 1995; Okonkwo et al., 2010) referring to different groups with both diagnoses (both patients and healthy subjects), we performed a CFA on the SF-12 responses to confirm the two-factor structure and the factors were allowed to correlate.

An open-ended question analysis was conducted using T-Lab Plus (Lancia, 2004) content analysis software. The pre-processing steps include: text segmentation, automatic lemmatization or stemming, multi-word and stop-word detection, key-term selection. The thematic analysis tools deal mostly with finding patterns of key-words within context units. all analysis units (i.e. words, text segments and documents) have been grouped either by a bottom-up or a top-down approach.

Ethical Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the Associazione Italiana di Psicologia (AIP), and all the participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki prior to participation. As there is no psychological ethics committee at the University of Salerno, ethical review and approval were not required for a study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The protocol was approved by an independent committee from the Centro di Counseling Psicologico (Psychological Counseling Center) of the University.

Results

The test of the difference χ2 between the one-factor and two-factor models was found to be significant (TRd = −105.262; Δdf = 1; p < 0.001), supporting the hypothesis of an adequate discriminant validity of the two-factor solution that supported the scoring procedure. The internal consistency of the SF-12 in the raw score was adequate, exhibiting a Cronbach’s α value of 0.892.

To accurately detect the presence or absence of the variables investigated, the participating students were divided into two groups: Group 1 (67 students with disabilities/SLDs) and Group 2 (96 students with normotypical development). Below, we provide the responses related to the questionnaire administered through a percentage comparison between the participating groups.

The differences between the groups in the responses to the items of the questionnaire administered were moderate and positive (r = 0.329; p < 0.001) and supports the a priori hypotheses of our survey.

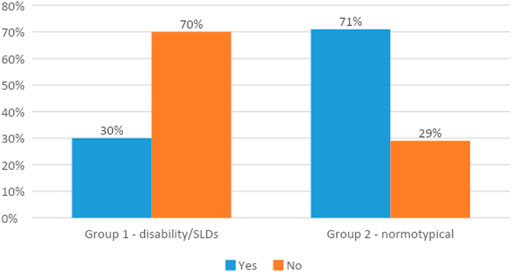

In relation to the initial question, which explored whether students made less progress than they would have liked, 71% of Group 2 reported a decrease in concentration during study compared with 30% of students with disabilities/SLDs (Group 1, see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Differences in percentage between groups relative to the item “Did you do your work or activities less carefully than usual?”.

With regard to the psychological well-being dimension, we found significant differences in that there was a higher vulnerability declared by the normotypical students compared with those in the disability/SLDs group.

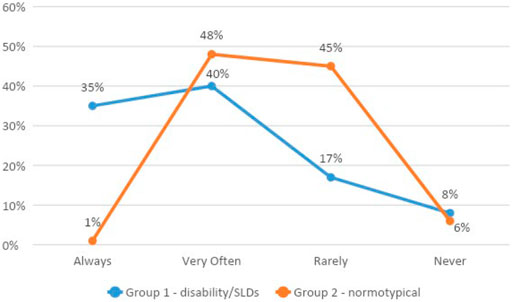

In particular, in relation to whether there was a feeling of calm and serenity during the lockdown period, only 1% of Group 2 responded “always” compared with 35% of Group 1, in which, by contrast, 40% stated “very often” (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Differences in percentage between groups relative to the item “Have you felt calm and peaceful?”.

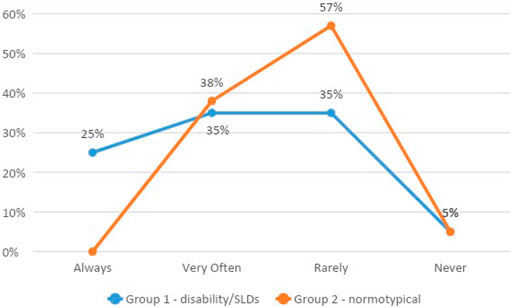

Of individuals in Group 2, 57% reported that they “rarely” felt energized versus 35% in Group 1, of which 25% indicated “always” as their answer (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Differences in percentage between groups relative to the item “Did you have a lot of energy?”.

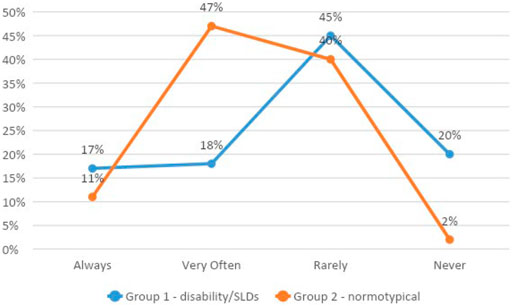

Of significance is the data that emerged in relation to the item “Have you felt downhearted and blue?” to which 47% of participants in Group 2 responded “very often” compared with 18% of the students with disabilities/SLDs (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. Differences in percentage between groups relative to the item “Have you felt down-hearted and blue?”.

Regarding the evaluation of the items related to ERT, the responses of students with disabilities/SLDs were examined, as they were the main object of the survey. Specifically, 82% felt that “distance learning was useful” and 42% stated that “they would like to continue it after returning to face-to-face learning”. For 85% of respondents “the University promptly supplied with online teaching”.

With respect to the problems encountered, 68% said they experienced at least a few. The analysis of the textual content of the open-ended item #9 showed that students with disabilities/SLDs reported often having problems with their Wi-Fi connection and experienced some difficulties with following the distance tutoring but that, in general, they had had a positive experience; the greatest difficulties concerned not having a physical relationship with teachers; being forced to stay in a closed, although familiar, environment; and, above all, not being able to interact with their peers. In addition, someone highlighted privacy issues, such as feeling shameful after being heard by their fellow students during exams or due to having their home seen through the Microsoft Teams camera.

The ERT experience was evaluated very positively, and useful strengths emerged, such as the ability to record the lecture and listen to it again, having the lecturer’s slides and notes in advance, using the computer, and avoiding the stress of traveling to attend lectures. Thirty-two percent of the students with disabilities/SLDs were satisfied with the current method of study.

Some students wished that the online mode will remain in the future as an alternative to provide accommodations for students with special needs. The most negative aspects were mainly related to the absence of comparison with peers and the lack of more continuous and immediate feedback from the teacher, as is generally the case when they are present in the classroom.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this study, we conducted a survey to evaluate the perceptions and satisfaction of university students with disabilities and specific learning disabilities (SLDs) for emergency remote teaching (ERT) during the lockdown phase (March–April 2020) and following restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We compared the responses of students with disabilities and SLDs with those of normotypical students.

The experiences of interviewed students with disabilities/SLDs with ERT were positive, although some psychological and relational difficulties were mentioned. With respect to concentration problems and, more generally, to the detection of psychological state, as a result of rapid changes in the lifestyles of most of the student population due to the pandemic, some researchers have highlighted post-lockdown issues, including anxiety, worry, fear, frustration, and insecurity. Duan and Zhu (2020) reported that these experiences may have negatively affected, for some subjects, personal well-being and academic success. Chirikov et al. (2020) obtained the same results.

With regard to social relationships, Novo et al. (2020) highlighted a relationship between students’ psychological distress and little or no social participation. Savarese et al. (2020) and Moccia et al. (2021) obtained the same results. These results and the health risk perceptions are very interesting. In a study conducted on Italian adolescents, the perception of health risk was found in only 5% of the adolescents interviewed (Commodari et al., 2020). In fact, Italian adolescents had a low perception of risk of COVID-19, and the susceptibility and perceived seriousness were also very low (Commodari and La Rosa, 2020). Ding et al. (2020) reported that normotypical students’ risk perception and the associated factors significantly affect mental health specifically, and that risk perception plays an important role in the mental health of people in a public health crisis, in particular depression, stress/anxiety and emotional distress. Cataudella et al. (2020), in addition to anxiety and distress for SLD students, highlighted low levels of well-being, self-esteem and self-efficacy, due to the lack of online inclusive accessibility standards and a lack of attention to online-specific tools.

By contrast, Miller (2002) studied the dimensions of resilience in a group of students with learning disabilities and found that one of the characteristics of resilient students is the identification of successful experiences and the ability to describe these experiences as deliberate steps in their success. Therefore, they are able to identify activities in which they might find success and use them to achieve even greater success, as in the case of ERT.

One outcome worth noting relates to the compensatory role that technological tools, which are highly valued by respondents with learning disabilities and disorders, can play for students with special needs. We think that the use of these tools led to the positive responses from the students, and as the emergency situation persists, the distance learning experience will continue.

Future Direction of Research

An interesting aspect, and one that we think we should explore in detail in further studies, is the contrasting evaluation of ERT for students with disabilities and learning disabilities compared with normotypical students. Briefly, we think that this can be attributed to the compensatory role normally played by technological tools in the undergraduate study of students with special educational needs.

Limitations

Future possibilities along this line of research are indicated by the limits of this study, such as the small number of students who participated in the survey preventing conducting inferential statistical analyses to generalize the findings to the population. Furthermore, classifying additional variables such as the SES will be useful for verifying whether socio-economic status differences affect the quality of the ERT.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Salerno-Centro di Counseling psicologico. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

GS defined the hypotheses, the research methodology and the interview program. GS and LC wrote the article and carried out the statistical analyzes. GB contributed to the editing and comments of the final draft of the article. All authors contributed to the final draft of the manuscript and agreed on the final version.

Funding

Fondi SOS SAVARESE.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bao, W. (2020). COVID ‐19 and Online Teaching in Higher Education: A Case Study of Peking University. Hum. Behav Emerg Tech 2 (2), 113–115. doi:10.1002/hbe2.191

Bates, T. (2020). Is There a Future for Distance Education?. Available at: https: www.tonybates.ca/2013/10/23/is-there-a-future-for-distance-education (Accessed august 28, 2020).

Cataudella, S., Carta, S., Mascia, M. L., Masala, C., Petretto, D. R., and Penna, M. P. (2020). Psychological Aspects of Students with Learning Disabilities in E-Environments: A Mini Review and Future Research Directions. Front. Psychol. 11, 611818. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.611818

Chirikov, I., Soria, K. M., Horgos, B., and Jones-White, D. (2020). Undergraduate and Graduate Students' Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. UC Berkeley: Center for Studies in Higher Education. Available at: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/80k5d5hw.

Commodari, E., and La Rosa, V. L. (2020). Adolescents in Quarantine during COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy: Perceived Health Risk, Beliefs, Psychological Experiences and Expectations for the Future. Front. Psychol. 11, 2480. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.559951

Commodari, E., La Rosa, V. L., and Coniglio, M. A. (2020). Health Risk Perceptions in the Era of the New Coronavirus: Are the Italian People Ready for a Novel Virus? A Cross-Sectional Study on Perceived Personal and Comparative Susceptibility for Infectious Diseases. Public Health 187, 8–14. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2020.07.036

Coppola, C., Mollo, M., and Pacelli, T. (2015). “The Development of Logical Tools through Socially Constructed and Culturally Based Activities,” in Educational Contexts and Borders through a Cultural Lens. Editors G. Marsico, V. Dazzani, M. Ristum, and A. de Souza Bastos (NY: Springer Cham), 1, 163–176. Cultural Psychology of Education. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-18765-5_12

Duan, L., and Zhu, G. (2020). Psychological Interventions for People Affected by the Covid-19 Epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry 7 (4), 300–302. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30073-0

Eysenbach, G. (2012). Correction: Improving the Quality of Web Surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J. Med. Internet Res. 14 (1), e8. doi:10.2196/jmir.2042

Favieri, F., Forte, G., Tambelli, R., and Casagrande, M. (2020). The Italians in the Time of Coronavirus: Psychosocial Aspects of Unexpected Covid-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 12, 551924. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3576804. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3576804

Herburger, D. (2020). Considerations for District and School Administrators Overseeing Distance Learning for Students with Disabilities. Crisis Response Resource. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED606081.pdf (Accessed November 25, 2020).

Lancia, F. (2004). Strumenti per l'analisi dei testi. Introduzione all' uso di T-LAB. FrancoAngeli Edizioni. Available at: https://www.tlab.it/?lang=it.

Liu, X., Liu, J., and Zhong, X. (2020). Psychological State of College Students During COVID-19 Epidemic. SSRN J.. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3552814

Marinaci, T., Carpinelli, L., Venuleo, C., Savarese, G., and Cavallo, P. (2020). Emotional Distress, Psychosomatic Symptoms and Their Relationship with Institutional Responses: A Survey of Italian Frontline Medical Staff during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Heliyon 6 (12), e05766. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05766

Marsico, G. (2018). The Challenges of the Schooling from Cultural Psychology of Education. Integr. Psych. Behav. 52 (3), 474–489. doi:10.1007/s12124-018-9454-6

Miller, M. (2002). Resilience Elements in Students with Learning Disabilities. J. Clin. Psychol. 58 (3), 291–298. doi:10.1002/jclp.10018

Moccia, G., Carpinelli, L., Savarese, G., Borrelli, A., Boccia, G., Motta, O., et al. (2021). Perception of Health, Mistrust, Anxiety, and Indecision in a Group of Italians Vaccinated against COVID-19. Vaccines 9 (6), 612. doi:10.3390/vaccines9060612

Novo, M., Gancedo, Y., and Vázquez, M. J. (2020). Relationship between Class Participation and Well-Being in university Students and the Effect of Covid-19. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Yurena_Gancedo/publication/341272288_Relationship_between_class_participation_and_well_being_in_university_students_and_the_effect_of_COVID-19/links/5eb6e429a6fdcc1f1dcb13df/Relationship-between-class-participation-and-well-being-in-university-students-and-the-effect-of-COVID-19.pdf (Accessed November 25, 2020). doi:10.21125/edulearn.2020.0842

Okonkwo, O. C., Roth, D. L., Pulley, L., and Howard, G. (2010). Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Validity of the SF-12 for Persons with and without a History of Stroke. Qual. Life Res. 19 (9), 1323–1331. doi:10.1007/s11136-010-9691-8

Pavone, M. (2018). “Postfazione. Le università di fronte alla sfida dell'inclusione degli studenti con disabilità,” in Universal Inclusion. Rights and Opportunities for Students with Disabilities in the Academic Context. Editors S. Pace, M. Pavone, and D. Petrini (Milano: FrancoAngeli), 283–298.

Pursel, B. K., Zhang, L., Jablokow, K. W., Choi, G. W., and Velegol, D. (2016). Understanding MOOC Students: Motivations and Behaviours Indicative of MOOC Completion. J. Comp. Assist. Learn. 32, 202–217. doi:10.1111/jcal.12131

Savarese, G., Curcio, L., D’Elia, D., Fasano, O., and Pecoraro, N. (2020). Online University Counselling Services and Psychological Problems Among Italian Students in Lockdown Due to Covid-19. Healthcare 8 (4), 440–456. doi:10.3390/healthcare8040440

Shale, D. (2002). The Hybridisation of Higher Education in Canada. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distance Learn. 2 (2), 1–12. doi:10.19173/irrodl.v2i2.64

Teixeira, A. M., Bates, T., and Mota, J. (2019). What Future(s) for Distance Education Universities? towards an Open Network-Based Approach. Ried 22 (1), 107–126. doi:10.5944/ried.22.1.22288

Thelwall, M., and Levitt, J. M. (2020). Retweeting Covid-19 Disability Issues: Risks, Support and Outrage. El profesional de la información 29 (2), 1–12. doi:10.3145/epi.2020.mar.16

Toquero, C. M. D. (2020). Inclusion of People with Disabilities amid COVID-19: Laws, Interventions, Recommendations. Remie 10 (2), 158–177. doi:10.17583/remie.2020.5877

UNESCO (2020). News - Emergency for global education, as fewer than half world’s students cannot return to school New York: UN. Available at: https://en.unesco.org/themes/education-emergencies/coronavirus-school- closures (Accessed 08 28, 2020).

Ware, J. E., Kosinski, M., and Keller, S. D. (1995). SF-12: How to Score the SF-12 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales. Boston: Health Institute, New England Medical Center. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242636950.

White, M. K., Maher, S. M., Rizio, A. A., and Bjorner, J. B. (2018). A Meta-Analytic Review of Measurement Equivalence Study Findings of The SF-36® And SF-12® Health Surveys Across Electronic Modes Compared To Paper Administration. Quality Life Res. 27 (7), 1757–1767. doi:10.1007/s11136-018-1851-2

Zhang, H., Nurius, P., Sefidgar, Y., Morris, M., Balasubramanian, S., Brown, J., et al. (2020). How Does COVID-19 Impact Students with Disabilities/Health Concerns?. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.05438 (Accessed November 25, 2020).

Keywords: COVID-19, lockdown, emergency remote learning, disabilites, specific learning disabilities

Citation: Carpinelli L, Bruno G and Savarese G (2021) A Brief Research Report on the Perception and Satisfaction of Italian University Students With Disabilities and Specific Learning Disabilities at the Emergency Remote Teaching During the COVID-19 Lockdown. Front. Educ. 6:680965. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.680965

Received: 15 March 2021; Accepted: 26 July 2021;

Published: 05 August 2021.

Edited by:

Jesús-Nicasio García-Sánchez, Universidad de León, SpainReviewed by:

Caterina Buzzai, Kore University of Enna, ItalyValentina Lucia La Rosa, University of Catania, Italy

Copyright © 2021 Carpinelli, Bruno and Savarese. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Giulia Savarese, Z3NhdmFyZXNlQHVuaXNhLml0

Luna Carpinelli

Luna Carpinelli Giorgia Bruno

Giorgia Bruno Giulia Savarese

Giulia Savarese