95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

METHODS article

Front. Educ. , 28 January 2022

Sec. Digital Education

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.677625

This article is part of the Research Topic Analytics and Mathematics in Adaptive and Smart Learning View all 8 articles

The Covid-19 pandemic has caused a great change in the world. One aspect of the pandemic is its effect on Educational systems. Educators have had to shift to a pure online based system. This shift has been sudden and without any prior warning. Despite this the Educational system has survived and exhibited resilience. The resilience of a system can be determined if the system continues to operate or function as effectively as before a change. Resilience in a system implies the ability to work and develop when the forces in the environment are unexpected, abrupt and sudden as well. The environment may change or evolve but the underlying system must keep functioning, developing and responding. Resilience is a trait in a system. It is a set of characteristics in the system that enables it to sustain itself in the face of change. A resilient system can cope and prosper in the face of change. For the domain of education, the Covid-19 pandemic served as a phenomenal change event and a wakeup call to the education fraternity. As a social system, resilience meant that the people in the educational environment continued to function albeit differently. The environment, meaning the processes, hierarchy and the intricate social ties in the system contributed to the resiliency of the system. Thus the measure of resilience in education has three major facets—people, the technology which facilitates the process and the process environment. This work aims to understand the resilience of the teachers due to the Covid-19 pandemic, especially how learning continued and what contributed to this continuity. Resilience research and understanding is as important as the pedagogical and technological aspects in an Educational system as it is a trait that encompasses the people, the socio-economic system and their relationships. In this work, we analyzed resilience as trait, its relevance in an Educational system, factors that make up resilience in an Educational system and finally the relevant research about resilience in Education during Covid-19. Based on the results of our literature review we formed a model for Educators. A survey was conducted among educators of three countries namely Malaysia, Fiji, and India to determine the essential elements of resilience that were relevant to the continuity of an educational system from the point of view of teachers. We arrived at a set of factors that are relevant to the teachers in the educational systems which can be an impetus for policy makers to focus on and develop. The major results from the study are the need for Educational systems to focus on three facets—internal, interpersonal and external aspects of teachers and strengthen factors such as support for teachers, strong academic leadership, trust of teachers, increase self-motivation, enhance communication with stakeholders and emphasize systems that enhance student-teacher communication. The future areas of research are also discussed in the work.

For decades, educational systems have rarely changed willingly and swiftly. However, the Covid-19 pandemic changed this mind-set, whereby online distance learning (ODL) and emergency remote teaching (ERT) became a normal mode of learning and physical in-class teaching and learning became abnormal.

Let us first trace the challenges faced by educational systems during the Covid-19 pandemic.

As a part of a multi-country study, Reimers and Schleicher (2020) listed the key factors ensuring the continuity of academic learning for students, supporting the students who lack skills for independent study, ensuring continuity and integrity of the assessment of student learning, ensuring support for parents so they can support student learning, and ensuring the well-being of students and of teachers.

The educational response of China’s system was studied by Xue et al. (2020) and factors such as ensuring the well-being of teachers, standardizing online teaching, motivating teachers, communication with teachers and parents and focus on the mental health of students were listed as important factors.

Pokhrel and Chhetri (2021) analyzed various publications during Covid-19 and emphasized the role of e-learning tools, mindsets of teachers and students, challenges of access, affordability, students with disability and guidance and highlighted the opportunities for creative learning that are available for the faculty. The challenges for universities in terms of access, opportunity, need for preparedness of teachers, issues in student’s difficulties to adjust, need for resources for teaching and opportunities for teachers to innovate were focused on the research spotlighted by Mseleku (2020).

In Bond (2020), the teacher focused skills, support for teachers, student focused factors such as motivation, self-regulation, support by the institutions, need for a proper learning environment and the need for peer support was discussed. The work by Carrillo and Flores (2020) summarizes the research during Covid-19 and emphasized teacher centric factors such as social presence, cognitive presence, participation in online communities, and teaching presence.

The above publications were literature reviews during Covid-19 and brought out the challenges for Educational systems and teachers. The common factors that emerged are

• Teacher centric

o Motivation

o Support (moral, health and technical)

o Training

o Strong notion of backing and trust

• Student centric

o Access

o Academic process communication

o Affordability

o Support

o Presence of teachers in terms of teaching and moral support

• Communication

o All stakeholders on overall aspects

o Teachers and students in a supportive manner

There was also a lot of focus on resilience as one of mitigating factors during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The work by Appolloni et al. (2021) focuses on the actions by institutions in Italy and highlights the resilience in the educational system in Italy. The key findings were the need for strong leadership, effective communication with all stakeholders, a sense of community among the faculty, and administrative support for the system.

Naidu (2021) advocated the need for a rethink and reengineer the educational and institutional systems to avoid future catastrophes. Giovannini et al. (2020) focused on the institutional parameters and explained that in a resilient society, not only the individuals are important but the support by institutions, well-crafted policies, social ties, etc., are crucial for success.

In Bartusevičienė et al. (2021), the student and faculty perceptions about the migration to online learning during Covid-19 were examined. The factors experienced in the transition were resources, support and competencies. The three capabilities (anticipation, coping and adaptation), and the transitions the University took were traced. The key aspects that emerged was that resilience depended on availability of resources, continuous professional development, continuous communication with teachers and students, support networks, adaptation and building the knowledge base.

Nandy et al. (2020) focused on the resilience at a Higher Education Institution (HEI) level. The focus was on the interventions the HEIs can take to address risks and transition to a post pandemic environment. Their suggested steps for HEIs to follow included identifying the factors that helped the institutions tide over the crisis, skill mapping to identify the needs of training, examine the strength and weakness of the Educational system, appreciation of faculty and documenting the lessons learned.

Beale (2020) focused on the academic resilience from a student centric view and traced factors such as self-efficacy, coordination, sense of control, composure and perseverance. Some of these factors can be postulated to focus on institutional resilience as well. In a similar vein, Sánchez Ruiz et al. (2021) analyzed student’s perceptions of educational resilience of a university and found that blended learning methodologies facilitated the university’s resilience and improved the quality of learning. In systems where the adoption of blended learning was done prior to the pandemic, the resilience and adaptation in the eyes of students was higher.

Thus we have traced the relevant publications that focus on resilience in academic environments during Covid-19.

The common factors that emerged are

• Strong leadership

• Support for faculty

• Continuous professional development

• Communication with stakeholders

• Well-crafted policies

• Sense of community

Let us examine the foundations of resilience and trace the relevant studies about resilience in education and the Covid-19 pandemic.

Resilience is a property of a system that helps the system adapt to change so as to function as effectively as before or better. Resilience studies seem to start with disruption and return to normalcy and have helped many natural systems survive over the years. In its most simplistic sense, resilience is “an ability to recover from or adjust easily to misfortune or change” (Merriam Webster). The American Psychological Association (APA) defines resilience as the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or significant sources of stress—such as family and relationship problems, serious health problems or workplace and financial stressors. The term refers to how one copes, manages emotions, and seeks support in challenging times. The APA also stresses that building resilience takes time and intentionality. In engineered systems, the major terms surveyed in literature (Cottam et al., 2019) focus on the ability to complete a mission in the face of current and future adversity. The common assumption is the ability of the system to maintain stability and keep functioning at a level of acceptability in the face of threats and perturbations.

Biggs et al. (2015) focus on the seven essential principles of resilience encompassing diversity, managing connectivity, feedback, encouraging learning etc.

The work of Kaye-Kauderer et al. (2021) focuses on resilience during the Covid-19 pandemic and explains that positive effects, cognitive reappraisal and social support can be factors which can help the individuals cope with the pandemic.

The classification of student resilience in Theron (2021) focused on a range of factors at a macro level in terms of students and educational institution. In Educational institution level, leadership, infrastructure, organizational climate, the supportive network, peer support, resilient teachers, teacher-student and student-student relationships, adaptive assessment approaches are focused on. The student resilience with respect to online education was explored by Simons et al. (2018) as internal challenges to managing studies, persistence factors such as faculty feedback, motivation and self-belief, support such as tutors, students, friends, family etc.

McIntosh and Shaw (2017) classified student resilience in terms of internal and external factors. The internal factors encompass self-management and emotional ability. The external factors focused on social integration and the support networks.

Morales-Rodríguez et al. (2021), analyzed the relation between stress and coping strategies during Covid-19. This is an interesting aspect of the university setting as the resilience, stress and coping mechanisms are together important.

The Connor Davidson resilience scale (Connor and Davidson 2003) is one of the earliest known measures providing a measure of an individual’s resilience. It has been applied in a variety of contexts in Covid-19 scenario as well (Ferreira et al., 2020; Alameddine et al., 2021; Zysberg and Maskit 2021).

An allied work in the same direction is the Academic Resilience Scale (Cassidy, 2016) providing a measure of student academic resilience to the challenges in HEIs. This comprised of major factors such as perseverance, reflection, emotion responses and measures the self-efficacy of students. Fullerton et al. (2021) focused on the personal resilience resources and their interaction in an academic setting. The focus of study was mental toughness, self-esteem, self-efficacy, optimizing, meaning in life and adaptability. The role of academic leadership on motivation, burnout and performance were correlated with academic resilience by Trigueros et al. (2020) based on a study of students. One of the important postulates in Kimhi et al. (2020) is the importance of psychological attributes on resilience and recovery from Covid-19.

In Dohaney et al. (2020) a systematic outline of capabilities of resilient Individuals and institutions are given. Flexibility, adaptability, collaboration, digital literacy, quick thinking and pedagogical soundness are the hall marks of individuals. Institutional factors are communication strategies, leadership, emergency response plans, support for faculty, community building and motivation.

Liu et al. (2017) provided a framework and theoretical basis postulating that moderate exposure to adversity seems to increase resilience which is seen as a personality trait and a time based evolution. Their multi-level model of resilience focused on the following:

1) core resilience–individual factors

2) internal resilience–interpersonal factors, and

3) external resilience–socio-economic factors

Thus we can see resilience from its definition, principles, dimensions and various studies during Covid-19. The key factors that emerged can be organized as

• Individual–positivity, motivation, self-belief, emotional ability, perseverance, self-reflection,

• Interpersonal–social support, support system, peer support, stakeholder support

• Institution–leadership, organizational climate, community building

From the above we can infer that educational resilience comes from the teachers, the system in the academic environment and the relational capital with the community. We seek to focus on the narrower subset of this and explore teacher centric resilience of the academic environment with respect to three characteristics, namely—internal, interpersonal and external factors.

The selection of the three characteristics comes from the Literature reviewed so far and summarized again in Table 1 and shown in Figure 1.

This paper adopts a view to discuss teachers’ resilience with regards the following:

• Internal which encapsulates resilience related to mindset, upskilling, motivation, positivity, reflection, and adapting

• Interpersonal–consisting of resilience related to relationships or communication with learners, between peers and with the parents/guardians.

• External resilience which includes trust, support and institutional measures.

The primary method of research was the survey method. The data for this study was collected using a survey instrument built by the authors which secured a reliability of 0.829 using the Cronbach alpha test. The survey was distributed using an online method, where teachers from Fiji, India and Malaysia were provided a link to the survey created using Google docs which addressed constructs related to their teaching experiences during the Covid-19 scenario.

A total of 102 teachers (belonging to all sections of the educational environment—tutors, teachers, educators, professors) responded to the survey which was made up of 58 percent males and 42 percent females (See Table 2). As a follow up, interviews with a cross section of teachers who responded to the survey were also carried out.

The survey was conducted at the end of January 2021 and as follow up, interviews with a cross section of teachers who responded to the survey were also carried out. This coincided with the schools/colleges reopening for face-to- face classes in some institutions while ODL and ERT mode of teaching continued in parallel in many institutions. The timing was deliberate as we wanted to study the scenario when teachers could reflect on the past year (as opposed to being in the moment during Covid-19) and give constructive thoughts on their challenges and learning.

Table 3 shows the domains of the respondents with the highest respondents in math, science, computer science and engineering (the STEM domains) representing 55%; followed by English and Language (24%) and others such as Chemistry, Geography, Social Sciences (21%), whereas Table 4 shows the countries represented by the participants and Table 5 their years of experience.

The study respondents belong predominantly to three different countries viz, India, Fiji and Malaysia. The domains the respondents belonged to were diverse. The experience levels are also diverse with educators from all the levels of seniority participating. We wanted to pursue a multi-country study with Educators from different domains and experience levels. This help us understand the factors in Education that matter and also capture a snapshot of the resilience in the Educational systems during Covid-19.

In the next section, we will show the factors in resilience that emerged from the study. The results are shown in terms of internal, interpersonal and external resilience.

For internal resilience, the responses were linked to the following parameters: mindset and upskilling or reskilling of the participants. For upskilling and reskilling, the participants were asked to respond on the upskilling and re-skilling efforts undertaken by them with regards digital and pedagogical skills with regards the following parameters:

▪ Management of administrative work online

▪ Training efforts on how to teach online

▪ Video editing skills for online learning

▪ Mindset changes undertaken with regards online teaching

▪ Skills development related to various technology skills

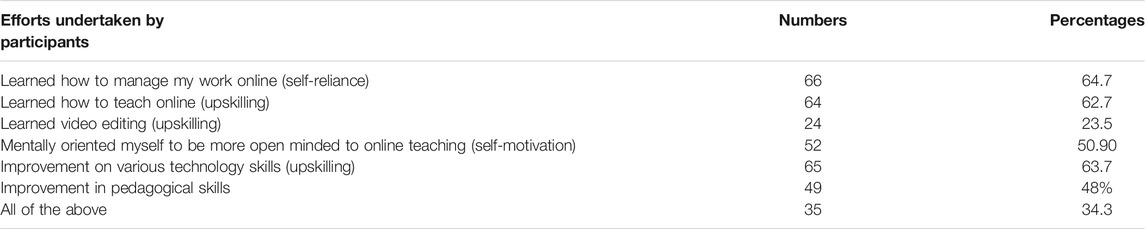

Table 6 shows the types of skills the participants improved during the transition of the teaching and learning process amid Covid-19. A large portion of the participants improved on various technology skills for teaching and learning such as learned how to teach online, learned video editing, improve various technology skills and learned how to manage my work online after the Covid-19 pandemic.

TABLE 6. Percentage improvement in techno-pedagogical skills as a result of remote teaching and learning in a Covid-19 pandemic.

The biggest change for teachers that they expressed was the mindset change. 97% of the teachers felt that this was the most important skill that was needed. This was followed by learning how to teach online which was expressed by 96% of teachers. The open mindedness part was remarked upon by 85% of the respondents followed by the pedagogical skills 82%. These are logical conclusions.

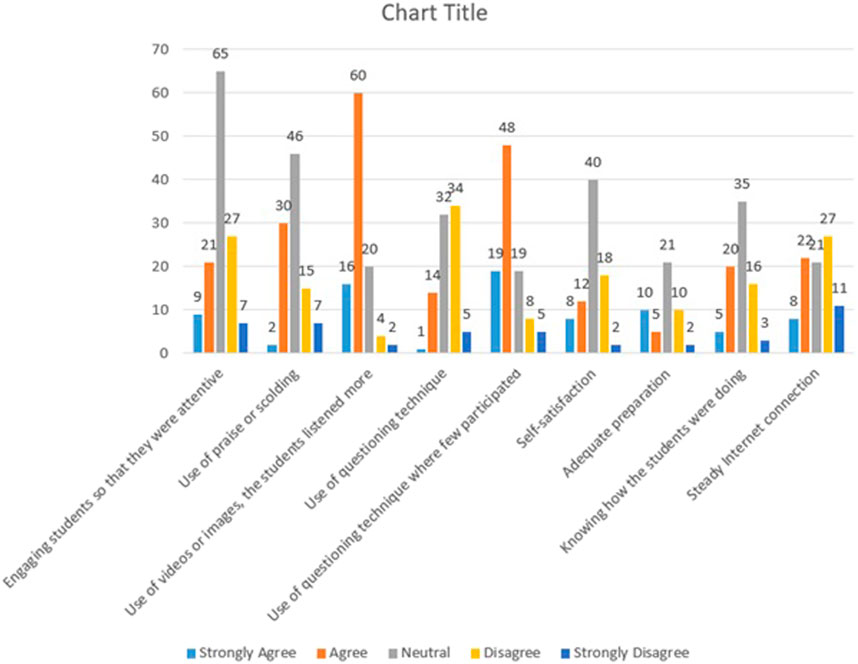

Interpersonal resilience (Table 7) in this study referred to how teachers continuously communicated with learners and connected them with their peers as well as communications with parents/guardians. manage their learners and provided support in times of difficulties.

• Engaging students so that they were attentive

• Communication with students through positive or advise based (scolding) measures

• Use of questioning techniques in classes

• Use of interactive media

The strongest interpersonal resilient attribute (Table 1) amongst the 102 teachers was the teaching methods that promoted questioning with more than 65% agreeing that this was the best method. Use of praise or scolding was not that effective with only 30% of teachers advocating the effectiveness of the approach. The methods such as dialogue and pure lecturing were also not that effective as with only 37% of the overall respondents agreeing about the methods. Interactive media based methods promoted engagement through a social presence, livening up the classes and increasing interest among students.

The result shows an interesting paradigm on inter-personal resilience viz. the major methods that showed results. Questioning is a method that showed student and teacher presence. This also meant a personal touch and empathy. The use of interactive media based methods helped the teachers in reaching students. The medium of the web could be better used with even normally reticent students engaging in classes.

External resilience is exhibited when participants are able to continue to perform when there is institutional trust in them, knowledge of latest policies/ordinances, new infrastructures are well supported and rules are well communicated, especially when the teachers were working from home (WFH).

From Table 8, it can be seen that a total of 61% of teachers agreed that the management and leaderships’ trust pushed them to be resilient to conduct their classes although they were working remotely despite the fact that the online assistance from their institutions was low (approximately 27%). When asked if the institution supported them in the teaching and learning process, during the Covid-19 pandemic, 72% said yes (see Figure 2). However, family support was seen as the highest (86%), followed by students (68%) and friends/colleagues (66%). With regards working from home, teachers managed to keep up with their resiliency in ensuring that they did not compromise on the use of innovative methods to engage learners.

FIGURE 2. Factors related to external resilience. Note. 1 = Strongly Agree and five Strongly Disagree.

From the above we can conclude that the teaching community had support from the system. They had a good range of support from the institution and the community of learners.

In this work, we have done a survey on the resilience of 102 teachers from three different countries, namely India, Malaysia and Fiji and traced the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on their resiliency to continue the teaching and learning process. We mapped the resilience according to internal, interpersonal and external factors. We will discuss the findings below.

In our work, variables such as institutional support, peer support and student support are modeled as coping mechanisms for stress. We build on Morales-Rodríguez et al. (2021) whose focus was stress and coping strategies. We seek to examine resilience as a composite trait. Our work is similar to the Connor Davidson Resilience scale (Connor and Davidson, 2003) and aspects of Connor Davidson scale are incorporated in the survey questions.

The data showed positively that teachers made an effort to upskill themselves during the pandemic. Teachers made an effort to upskill themselves in techniques to engage learners in online learning especially on how to use live session technologies, the use of mobile phones, LMS and lecture recording; learn how to edit videos and change their mindsets to ensure they were able to better serve their students. These findings are important in relation to internal resilience as they were the core attributes of online learning that impacted teaching and learning in a remote online learning environment. The findings on internal resilience corroborates with Kimhi et al. (2020), Connor and Davidson (2003), Fullerton et al. (2021), Beale (2020).

The interpersonal resilience in teaching focuses on the communication with students and the way this communication takes place. From the data, we found that around two thirds (65.6%) of respondents did adopt methods that helped drive engagement among students. The primary method of communication was questioning based techniques. One of the interesting aspects in the innovative teaching methods aspect is that more than 75% used interactive media based communication method to engage with students. These teachers also devised new strategies. Resilience also means having the ability to design ways to ensure an acceptable level of student engagement.

The data showed that the trust and support from institution, family, colleagues and students enabled teachers to exhibit a high external resilience (Figure 3). Literature shows that trust especially positive effects, cognitive reappraisal and social support can be factors which can help the individuals cope with the pandemic (Kaye-Kauderer et al., 2021). The trust is also related to the support by institutions, well-crafted policies, and maintenance of social ties, for success in the job (Giovannini et al., 2020). Further, the work by Appolloni et al. (2021) testifies that strong leadership, effective communication with all stakeholders, a sense of community among the faculty, and administrative support for the system were important to maintain external resilience.

The following are limitations of this study. The geographic scope is tilted towards Malaysia. The mitigating factor is that the study respondents were from all the domains of education not just STEM and all strata of experience and seniority.

Nonetheless, the study does provide some indicators. The indicators are that trust by institutions, support by family, institutions, friends and students are a big factor. This may have given a boost to upskilling and thus innovative methods in teaching. We were able to find this in interviews but were unable to establish this thread using data.

This work outlines teacher resilience as a factor during the Covid-19 pandemic. Given the widespread adaptation that was needed by teachers in a short period of time, it was important to understand the internal, inter-personal and external factors that affected teacher resilience during the pandemic. This is an important result. Factors of Educational resilience showcase not only the areas for educational systems to strengthen but shed light on aspects that do not make much of a difference. Trust is an important factor. Communication networks (teacher-teacher, teacher-student) help teachers a lot. The role of student champions is not a factor. Technology used in the respective domains is not a factor. The major contribution of this work is thus to showcase Teacher resilience in terms of internal, interpersonal and external categories. This aligns with the existing literature in Table 1. The factors in teacher resilience are important for administrators. Every aspect of the teaching eco-system has an implication from this study. From internal resilience, the factors of strengthening self-reliance, well-being, motivation, learning skills and technical skills are showcased. From inter-personal resilience, the need for the pedagogy to incorporate teaching presence, communication between teachers and students and technologies that can foster that emerge. One interesting dynamic of the presence is that many teachers were concerned at not being able to reach the students who could not communicate (silence, non-participation) and had limited technology. Trust and support networks for teachers are a key factor that emerged in external resilience. Strong leadership is also another factor that emerged. The results of this study cannot be generalized, but it gives a panoramic view of the importance of resilience in educational systems during a pandemic and how to be more prepared in future. This study has also thrown a few areas for further researchers to pursue. Teacher resilience and its role in enhancing learning is an area of interest. The relation between smart and innovative learning and teacher resilience is something that we could not establish in this work. Teacher resilience is a ripe area worth pursuing as a domain and our future work will seek to pursue this with data analytics as a base as well.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because The datasets have the potential to contain private data. Hence depending on approval of all the authors, we can furnish anonymized datasets. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to BS, YmliaHlhLnNoYXJtYUB1c3AuYWMuZmo=.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Alameddine, M., Bou-Karroum, K., Ghalayini, W., and Abiad, F. (2021). Investigating the Resilience of Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic A Cross-Sectional Survey from Lebanon. Res. Square 47, 777–780. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-168997/v1

Appolloni, A., Colasanti, N., Fantauzzi, C., Fiorani, G., and Frondizi, R. (2021). Distance Learning as a Resilience Strategy during Covid-19: An Analysis of the Italian Context. Sustainability 13 (3), 1388. doi:10.3390/su13031388

Bartusevičienė, I., Pazaver, A., and Kitada, M. (2021). Building a Resilient university: Ensuring Academic Continuity-Transition from Face-To-Face to Online in the COVID-19 Pandemic. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 20, 1–22. doi:10.1007/s13437-021-00239-x

Beale, J. (2020). Academic Resilience and its Importance in Education after Covid-19. Eton J. Innov. Res. Educ. 4, 1–6. Available at: https://cirl.etoncollege.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2020/11/Issue-4-2.pdf.

R. Biggs, M. Schlüter, and M. L. Schoon (Editors) (2015). Principles for Building Resilience: Sustaining Ecosystem Services in Social-Ecological Systems. Arizona. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316014240

Bond, M. (2020). Schools and Emergency Remote Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Living Rapid Systematic Review. Asian J. Dist. Edu. 15 (2), 191–247. doi:10.5281/zenodo.4425683

Carrillo, C., and Flores, M. A. (2020). COVID-19 and Teacher Education: a Literature Review of Online Teaching and Learning Practices. Eur. J. Teach. Edu. 43 (4), 466–487. doi:10.1080/02619768.2020.1821184

Cassidy, S. (2016). The Academic Resilience Scale (ARS-30): A New Multidimensional Construct Measure. Front. Psychol. 7, 1787. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01787

Connor, K. M., and Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a New Resilience Scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 18 (2), 76–82. doi:10.1002/da.10113

Cottam, B. J., Specking, E. A., Small, C. A., Pohl, E. A., Parnell, G. S., and Buchanan, R. K. (2019). Defining Resilience for Engineered Systems. EMR 8 (2), 11–29. doi:10.5539/emr.v8n2p11

Dohaney, J., de Róiste, M., Salmon, R. A., and Sutherland, K. (2020). Benefits, Barriers, and Incentives for Improved Resilience to Disruption in university Teaching. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 50, 101691. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101691

Ferreira, R. J., Buttell, F., and Cannon, C. (2020). COVID-19: Immediate Predictors of Individual Resilience. Sustainability 12, 6495. doi:10.3390/su12166495

Fullerton, D. J., Zhang, L. M., and Kleitman, S. (2021). An Integrative Process Model of Resilience in an Academic Context: Resilience Resources, Coping Strategies, and Positive Adaptation. Plos One 16, e0246000. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246000

Giovannini, E., Benczur, P., Campolongo, F., Cariboni, J., and Manca, A. R. (2020). Time for Transformative Resilience: the COVID-19 Emergency. JRC Working Papers, No. JRC120489. Joint Research Centre-Seville site. doi:10.2760/062495

Kaye-Kauderer, H., Feingold, J. H., Feder, A., Southwick, S., and Charney, D. (2021). Resilience in the Age of COVID-19. BJPsych Adv. 27, 3166–3178. doi:10.1192/bja.2021.5

Kimhi, S., Marciano, H., Eshel, Y., and Adini, B. (2020). Recovery from the COVID-19 Pandemic: Distress and Resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 50, 101843. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101843

Liu, J. J. W., Reed, M., and Girard, T. A. (2017). Advancing Resilience: An Integrative, Multi-System Model of Resilience. Personal. Indiv. Diff. 111, 111–118. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.02.007

McIntosh, E. A., and Shaw, J. (2017). Student Resilience: Exploring the Positive Case for Resilience. Unite Students Publications. Available at: https://www.unite-group.co.uk/sites/default/files/2017-05/student-resilience.pdf (Accessed June 13, 2021).

Morales-Rodríguez, F. M., Martínez-Ramón, J. P., Méndez, I., Ruiz-Esteban, C., and Ruiz-Esteban, C. (2021). Stress, Coping, and Resilience before and after COVID-19: A Predictive Model Based on Artificial Intelligence in the university Environment. Front. Psychol. 12, 647964. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647964

Mseleku, Z. (2020). A Literature Review of E-Learning and E-Teaching in the Era of Covid-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Inn. Sci. Res. Tech. 5 (10), 588–597. AvaliableAt: https://ijisrt.com/assets/upload/files/IJISRT20OCT430.pdf.

Naidu, S. (2021). Building Resilience in Education Systems post-COVID-19. Distance Edu. 42, 11–14. doi:10.1080/01587919.2021.1885092

Nandy, M., Lodh, S., and Tang, A. (2020). Lessons from COVID-19 and a Resilience Model for Higher Education. Ind. High. Edu. 35, 3–9. doi:10.1177/0950422220962696

Pokhrel, S., and Chhetri, R. (2021). A Literature Review on Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Teaching and Learning. Higher Edu. Future 8 (1), 133–141. doi:10.1177/2347631120983481

Reimers, F. M., and Andreas, S. (2020). A Framework to Guide an Education Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic of 2020. OECD. Avaliable at: https://oecd.dam-broadcast.com/pm_7379_126_126988-t63lxosohs.pdf (Accessed April, 2021).

Sánchez Ruiz, L. M., Moll-López, S., Moraño-Fernández, J. A., Llobregat-Gómez, N., and Llobregat-Gómez, J. A. (2021). B-learning and Technology: Enablers for university Education Resilience. An Experience Case under COVID-19 in Spain. Sustainability 136, 3532. doi:10.3390/su13063532

Simons, J., Beaumont, K., and Holland, L. (2018). What Factors Promote Student Resilience on a Level 1 Distance Learning Module. Open Learn. J. Open Distance E-Lear. 33, 14–17. doi:10.1080/02680513.2017.1415140

Theron, L. (2021). “Learning about Systemic Resilience from Studies of Student Resilience,” in Multisystemic Resilience: Adaptation and Transformation in Contexts of Change. Oxford University press, 232–252. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190095888.003.0014

Trigueros, R., Padilla, A., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Mercader, I., López-Liria, R., and Rocamora, P. (2020). The Influence of Transformational Teacher Leadership on Academic Motivation and Resilience, Burnout and Academic Performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 1720, 7687. doi:10.3390/ijerph17207687

Xue, E., Li, J., Li, T., and Shang, W. (2020). China's Education Response to COVID-19: A Perspective of Policy Analysis. Educ. Philos. Theor., 53 (1) 1–13. doi:10.1080/00131857.2020.1793653

Zysberg, L., and Maskit, D. (2021). Resilience in Troubled Times: Emotional Reactions of Teaching College Faculty during the COVID-19 Crisis. J. Res. Pract. Coll. Teach. 6 (1), 219–241. Avaliable at: https://journals.uc.edu/index.php/jrpct/article/view/4189/3280.

Keywords: Resilience, Covid-19, education, educational system, teacher

Citation: Raghunathan S, Darshan Singh A and Sharma B (2022) Study of Resilience in Learning Environments During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Front. Educ. 6:677625. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.677625

Received: 08 March 2021; Accepted: 14 December 2021;

Published: 28 January 2022.

Edited by:

Shashidhar Venkatesh Murthy, James Cook University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Irene Kilanioti, National Technical University of Athens, GreeceCopyright © 2022 Raghunathan, Darshan Singh and Sharma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bibhya Sharma, YmliaHlhLnNoYXJtYUB1c3AuYWMuZmo=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.