- Department of Psychology, University of Prishtina “Hasan Prishtina”, Prishtina, Kosovo

The current study aims to identify the impact of transformational and transactional attributes of school principal leadership on teachers’ motivation for work. A sample of 357 Kosovar public middle school teachers was assessed using the Work Tasks Motivation Scale for Teachers (WTMST) and the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ). Results revealed that transformational leadership attributes, idealised influence, and inspirational motivation predict autonomous motivation in teachers; individual consideration predicts motivation for complementary tasks; and contingent reward significantly predicts motivation for student evaluations. The present study findings can serve as a support in improving the quality of education in low- and middle-income countries.

Introduction

Qualified, motivated, and empowered teachers play a central role in educating children and adults in their respective countries with the needed knowledge, skills, and values to enjoy healthy and fulfilling lives (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2018). Because they have an impact upon the educational development of individuals (Kotherja, 2013), teachers are one of the main determinants of education quality and learning outcomes (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2018). Hence, teachers should perform to the best of their abilities in educational activities so they can positively impact students’ learning (Bourn et al., 2017). However, teachers’ performance is associated with their motivation level, which not only influences their attitudes and perspectives towards work (Bush et al., 2010; Eyal and Roth, 2011) but also affects students’ outcomes and motivation to learn (Ahn, 2014; Fernet et al., 2008; Pelletier et al., 2002).

Teachers’ motivation to work is influenced by several factors, and the school principal leadership style has been found to be a major determinant of teachers’ level of motivation to work, school exhaustion, or burnout. Previous research findings have suggested that the leadership styles and practices by which school leaders lead and create the organisational climate of the school are among the main factors influencing teachers’ motivation for work (Roth et al., 2007), their motivation to perform specific tasks (Fernet et al., 2008), their autonomy and structure (Ahn, 2014), or their experienced pressure at work, thereby leading to exhaustion or burnout (Roth et al., 2007).

School principals who integrate creative insight, persistence, and energy with intuition and sensitivity to the needs of others, while inspiring them to surpass their self-interests, are known as transformational leaders (Bums, 1978; Bass and Avolio 1994). Transformational school leaders’ attributes have been found to impact teachers’ work performance (Hartinah et al., 2020), job satisfaction, and school commitment (Fuller et al., 1996); foster their intrinsic motivation, self-concept (Shamir et al., 1993), and professional growth (Kruger et al., 2007); and impact the school climate (Blatt, 2002) and student achievement (Leithwood and Jantzi, 2008).

Furthermore, within educational settings, school principals with a transformational leadership style1 can help teachers transcend their self-interests and self-centred values (Bass, 1999) through three core dimensions: vision building by initiating and identifying a vision for the school’s future, providing individual support, and providing intellectual stimulation (Leithwood et al., 1999; Geijsel et al., 2003; Leithwood and Jantzi, 2006).

Other studies have suggested that the characteristic of transformational school principal leaders, through which they inspire their staff to identify themselves with the organisation’s goals and the leader’s vision, positively impacts teachers’ autonomous motivation (Roth et al., 2007; Eyal and Roth 2011; Kanat-Maymon et al., 2020; Pelletier et al., 2002), which predicts their students’ autonomous motivation towards learning while also preventing teachers from burnout and positively impacting their self-actualisation at work (Roth et al., 2007).

When school principals employing a transformational leadership style provide teachers with individual support for professional development, teachers are positively impacted with regards to their sense of competence and self-efficacy (Geijsel et al., 2003). According to other study findings, intellectual stimulation, which invites followers to “question traditional beliefs ... and to find innovative solutions for problems” (Yukl, 1999, p. 288), was found to shield teachers from traditional and contextualised attitudes towards initiatives for change in their schools, thus motivating them to adopt to changes (Geijsel et al., 2003). Furthermore, there is also evidence that school principals’ transformational leadership attributes not only motivate teachers to implement a shared vision but also provide support for their desire for autonomy by encouraging individual efforts and offering directions based on their needs (Barnett and McCormick, 2003; Eyal and Roth, 2010).

There is also evidence that transactional school principal leadership styles impact teachers’ work. Transactional leadership comprises a wide range of leaders’ behaviours, from laissez-faire leadership (barely reacting in any situation) to active or passive management by exception (reacting only toward negative/critique-worthy behaviors), ultimately to provide contingent rewards and punishments (Gilbert and Kelloway, 2018).

According to the literature, the attributes of transactional leadership that aim to identify followers’ skills and propose compensation if a task is finished successfully (Bass, 1985) impact teacher burnout (Eyal and Roth, 2010). However, as specific attributes of school principals’ transactional leadership style (i.e., a process whereby the leader motivates his or her followers with rewards and promises while also showing acknowledgment and appreciation for their work; Bass and Steidlmeier, 1999), contingent rewards have been found to impact teachers’ motivation and prevent them from burnout (Eyal and Roth, 2010).

Other study findings have suggested that transactional leadership control practices impact teachers’ work, thus causing burnout, lower job satisfaction, and lower persistence. Still, there is also evidence that both attributes of transactional leadership styles, contingent rewards, and management by exception contribute to followers’ self-determination (Gagne ́ and Deci, 2005).

Transformational and transactional leadership are two opposing parts of a single continuum (Judge and Piccolo, 2004). Thus, they have fundamental differences that are easily observed. Transactional leaders react based on their followers’ performance and efforts with immediate rewards for the observed behaviours, and transformational leaders enlighten followers on the importance of the results and support them. Such leaders raise awareness regarding the organisation’s values as well as support followers in transforming their needs to higher levels (Bass, 1997).

Furthermore, teachers’ motivational factors were identified as mediating factors between school principals’ leadership styles and students’ learning outcomes (Leithwood and Jantzi, 2006; Leithwood and Mascall, 2008; Robinson et al., 2008; Supovitz et al., 2010). Specifically, through the transmission of a clear vision to followers in terms of developing school goals, including high academic goals, as well as obtaining staff consensus on desired outcomes, which are major influencers of the degree of teacher motivation, transformational school leaders enhance student learning (Leithwood and Steinbach, 1991; Leithwood, 1994; Leithwood et al., 1999).

Bass (1985) developed one of the most dominant theories discussed in both transformational and transactional leadership. Bass and Avolio (1994) defined transformational leaders as “leaders who integrate creative insight, persistence and energy, intuition and sensitivity to needs of the others” (p. 542). Bass (1997) agreed that transformational leaders help followers transcend beyond self-interest and self-centred values. The four crucial facets of transformational leadership are idealized influence, intellectual stimulation, individual consideration, and inspirational motivation. One of the core factors of transformational and transactional leadership theory (Bass and Avolio, 1993) is the augmentation effect, which determines what transformational leadership adds to the ultimate effect of transactional leadership. Based on the research findings through which the above theoretical model has been tested, transformational leadership has been found to predict followers’ self-concordance goals (i.e., autonomous motivation for specific goals), specifically with regards to their goal orientation (Charbonneau et al., 2001; Bono and Judge 2004).

Another theoretical framework, usually used to analyze the interplay among different factors influencing people’s motivation and satisfaction, is self-determination theory (SDT), which concludes that people are intrinsically motivated to act and that such intrinsic motivation produces internal satisfaction owing to the fulfilment of their basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness2 (Ryan and Deci, 2000, 2009). According to SDT, compliance, external rewards, and punishments, as part of the perceived locus of causality in the SDT, are influenced by contextual and external factors and may undermine self-motivation, social functioning, and personal well-being (Ryan and Deci, 2000).

The interplay among teachers’ leadership styles and motivation has also been analysed through the basic psychological needs theory, which is a subtheory of SDT (Deci and Ryan, 2000) that measures factors that can influence competence and the belief in one’s competence. Competence—as one of the three basic needs, along with autonomy and relatedness—describes the experience of efficacy while completing a task or dealing with environments (Deci and Ryan, 2000; Ryan and Deci, 2000). Competence is categorized as a motivational factor that is part of the expectancy component and is described as teachers’ beliefs in their ability to perform a task (Bandura, 1997). SDT researchers have argued that teachers’ motivation influences the types of instructional styles they employ (i.e., autonomy support, structure, and involvement), particularly those that support or thwart students’ basic needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan, 1995; Deci and Ryan 2000). Ryan et al. (1993) revealed that controlled regulation (external and introjection motivation) has the tendency to predict or be predicted by psychological consequences, whereas autonomous motivation (intrinsic motivation and identified regulation) tends to be linked with high performance, well-being, and low burnout (Gagne ́ and Deci, 2005). Kanat-Maymon et al. (2020) reported the linkage between controlled motivation as one type of motivation according to SDT and transactional leadership. Reeve (2009) mentioned the explanation for this linkage as the tendency to assess controlling motivating strategies as more effective based on the fact that their own motivation is controlled.

Even though schools across the world are an important context of development in which the needs of children should be considered, more than 80% of the world’s population of children and adolescents are considered to live in low- and middle-income countries, where resources to adequately educate these young people are insufficient (Blum et al., 2012; Sawyer et al., 2012). The following challenges are often considered when attempting to improve the quality of education among these countries: a) poor teacher training and b) lack of adequate education policies and schools that can equip students with outcomes in which their academic, physical, emotional, social, and moral development can be safely nurtured and progressed (Heart, 2011; Islami, 2018; Aliu, 2019; Fazel et al., 2014).

Although teaching as a profession is considered among the most selected careers within Kosovo, changes within the education system reforms, the large number of students, low salaries, lack of respect from the school directors, and poor physical working environments are considered some of the numerous stressors that teachers in Kosovo face (Shkëmbi et al., 2015).

According to Aliu (2019), despite the Kosovo institutional initiatives that have been undertaken to improve the quality of education (i.e., increasing teachers’ work motivation and performance by raising their salaries), this change did not result in improved quality of work or education. Meanwhile, Rama (2011) stated that teachers in Kosovo have been encouraged to enhance their teaching, while still being faced with obstacles that prevent them from recognising their abilities and/or discovering their capacities and potential to broaden their knowledge.

Improvement in the education legislation and the decentralization of competences from the national to the municipal, and institutional (school) levels—through which school directors have greater responsibilities in teacher management—are considered among the latest developments to the education system in Kosovo (United Nations Development Program, 2015). Whereas the Ministry of Education and Municipality elects the school directors, the municipality and school principal selects the teachers (Nikoçeviq, 2012). So far, findings have also suggested that school directors’ role and competences are not clearly defined, school directors have little say in the teachers’ evaluation or selection processes (United Nations Development Program, 2015), and schools are not yet autonomous in making decisions, such as staff selection itself (Aliu, 2019; Nikoçevic, 2012). Furthermore, research has also stated that Kosovo lacks involvement of teachers and school management in designing and developing the curriculum, and there is no evidence of any type of needs analysis for planning and training activities (Crighton et al., 2001; UNDP, 2015).

However, the current Kosovo Education Strategic Plan has stressed the importance of teachers’ training and professional development, the increase of managerial professionalism (Ministry of Education and Science, 2016; Aliu, 2019) and improve the quality of education. However, there is no evidence regarding the professional development of school leaders or the efficacy of teachers’ training.

Despite these studies, we found no evidence from the research in Kosovo that other factors influencing Kosovar teachers’ motivation to work have been measured. Therefore, the current study aims to identify the impact of transformational and transactional attributes of school principal leadership on teachers’ motivation towards work.

Based on existing findings from the global research, the educational leadership styles do impact teachers’ motivation for work and students’ learning. Therefore, the importance of school principals’ leadership behaviour on teachers and students should be recognised by educational leaders (Tajasom and Ahmad, 2011). In addition, educational leadership practices, through which teachers are supported on their achievement and professional advancement, are suggested to be more effective long-run motivators than working conditions and pay (Herzberg, 1966; cited in Chapman, 2003). Chapman (2003) argued that although teachers need housing, food, safety, and a sense of belonging, they also need a kind of support that encourages their types and levels of motivation, such as achievement, recognition, and career development. Furthermore, teachers’ motivation and self-determination for work have been shown to contribute directly to their autonomy and support towards students (Pelletier et al., 2002).

Studies investigating the relationship between leadership style, specifically transformational and transactional leadership style and teacher motivation across different countries (Kedah, Kuwait, and Turkey; Aydin et al., 2013; Bogler, 2001; Eyal and Roth, 2011; Raman et al., 2015), have confirmed the positive relationship between transformational and transactional leadership attributes and teachers’ motivation on the one hand (Alfahad et al., 2013) and teachers’ organisational commitment on the other (Cemaloğlu et al., 2012).

Nevertheless, other authors argued that leadership is a complex process and varies depending on the setting where it is practiced (Yukl and Becker 2006). From a specific sociocultural context that has not yet been studied, the current study findings can serve as a baseline for identifying and describing which factors are influencing teachers’ work, which can support school leaders in adapting their styles so as to conform to values and norms in their sociocultural contexts (Hallinger, 2018).

Moreover, considering the previously reported findings through which the impact of the school leadership styles has been measured, the current study results can also serve as a baseline for supporting the school leaders in improving their practices because school leadership is one of the core components supporting the improvement of the school, teacher performance, and commitment for work (Raman et al., 2015; Cemaloğlu et al., 2012).

Materials and Methods

Sampling and Procedure

The nature of the study is exploratory because it attempts to understand teachers’ perceptions about their principal’s leadership style. To ensure a more representative and nonbiased sample, we employed a stratified sampling method with a list of Prishtina schools, selecting every third school in the list. Two strata were created, and each was divided into two groups: one for large schools (more than 500) and one for small schools (less than 500 students). Prior to completing the survey, we obtained approval from the municipality educational directorate to access the schools and teachers in the municipality of Prishtina. We contacted the potential participants during their regular classes and informed them about the study’s purpose and the time required for participation. We further informed the participants that their responses would remain confidential and that they could stop participating at any time prior to data collection. Data were collected from December 2016 to February 2017. The time to complete the survey was approximately 40–45 min.

Participants

A total of 357 Kosovar public middle school teachers from the municipality of Prishtina participated in the study. The average age of the participants was 47.31 years old (SD = 11.94). Of the sample, 61.1% were female, and the remaining 38.9% were male, with varying years of work experience: 31.9% had worked for 1–9 years, 27.7% for 10–19 years, 23% for 20–29 years, 12.9% for 30–39 years, and the remaining 4.5% for 40–45 years.

Measures

The Work Tasks Motivation Scale for Teachers (WTMST) developed by Fernet et al. (2008) was used to assess the motivation level among the study participants. The WTMST consists of 15 items assessing five motivational constructs (e.g., intrinsic motivation, identified regulation, introjected regulation, external regulation, and amotivation) towards six work tasks (e.g., preparation, teaching, evaluation of students, classroom management, administrative tasks, and complementary tasks). The items were evaluated on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (does not correspond at all) to 7 (corresponds completely). The observed reliability for each of the subscales was in a good range: motivation for class preparation (α = 0.81); motivation for teaching (α = 0.82); motivation for evaluation of students (α = 0.84); motivation for administrative tasks (α = 0.86); and motivation for complementary tasks (α = 0.86).

The Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) developed by Bass and Avolio (2000) was used to assess the participants’ perceptions regarding their school principal’s leadership style. The questionnaire consisted of 45 items measuring transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership styles. A 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) was used. The observed reliability for the current sample was in a very good range (α = 0.93). The MLQ questionnaire was translated, back translated, and piloted in two phases in 2017.

Data Analysis

Data preparation and analysis were completed using IBM SPSS version 24. After data cleaning and weighting, the mean and standard deviation were calculated to provide a descriptive picture of the nature of the data. Pearson’s correlation analysis was carried out to explore whether there was a relationship between attributes of transformational and transactional leadership and autonomous and controlled motivation. The effects of transformational and transactional leadership attributes in different types of motivation (e.g., autonomous motivation for teaching, controlled motivation for evaluation of students, motivation for complementary tasks) were tested using multiple regression analysis.

Results

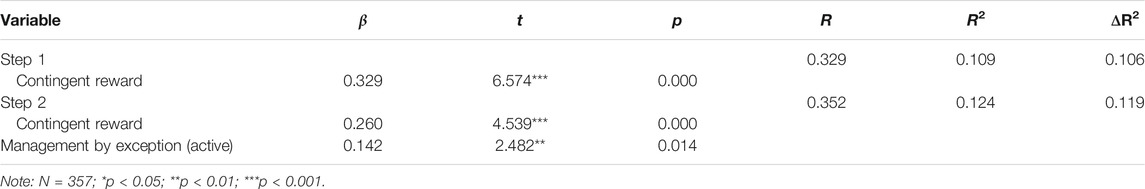

The final regression model predicting the motivation for evaluating students is shown in Table 1. A hierarchical linear regression reveals that at Stage 1, contingent reward contributed significantly to the regression model (F (1, 355) = 42.218, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.109). Introducing the management by exception (active) factor explained the variation in motivation, and thus, the change in R2 was significant (F (2, 354) = 25.004, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.124). The participants predicted that contingent rewards and management by exception (active), as attributes of transactional leadership, affect the motivation of teachers to evaluate their students (β = 6.45 and 2.52, respectively; all ps < 0.05). From the results, one can see that the regression model was significantly strengthened when management by exception (active) was presented.

TABLE 1. Summary of hierarchical regression analysis for variables predicting motivation for the evaluation of students.

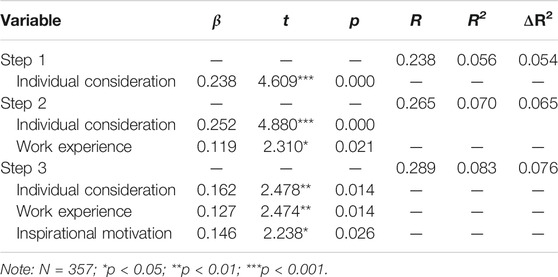

Next, a three-stage hierarchical multiple regression was conducted, with the motivation for complementary tasks serving as a dependent variable. As shown in Table 2, at Stage 1, individual consideration contributed significantly to the regression model (F (1, 355) = 21.238, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.056). Adding the work experience variable explained the variation in motivation for complementary tasks; thus, the change in R2 was significant (F (2, 354) = 13.417, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.070). In Stage 3, inspirational motivation, a transformational leadership attribute, was entered, which contributed to the variation in the motivation for complementary tasks (F (3, 353) = 10.716, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.083). The results showed an interesting link between the attributes of transformational leadership (individual consideration and inspirational motivation) and work experience with regards to motivation for complementary tasks.

TABLE 2. Summary of hierarchical regression analysis for variables predicting motivation for complementary tasks.

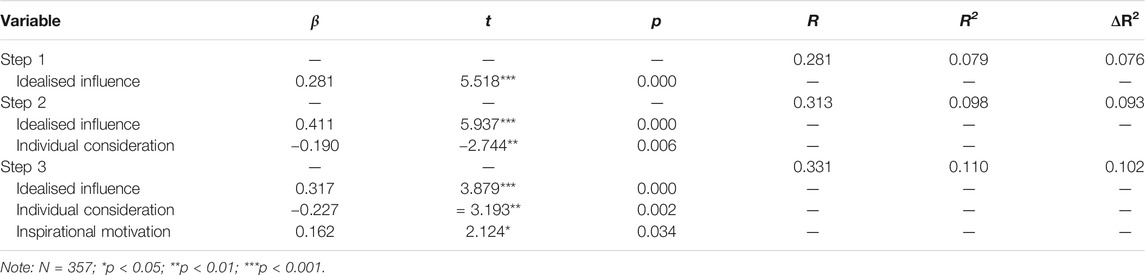

Autonomous motivation, comprising intrinsic motivation and identified regulation, was the third dependent variable tested with a three-step hierarchical regression, with autonomous motivation for teaching serving as a dependent variable. Table 3 below, which presents regression at Stage 1, reveals that idealised influence contributed significantly to the regression model (F (1, 355) = 30.444, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.079). In the second step of the regression, another attribute of transformational leadership, individual consideration, was added, which explained the variation in autonomous motivation for teaching; thus, the change in R2 was significant (F (2, 354) = 19.267, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.098). The third attribute of transformational leadership, inspirational motivation, was added in the third step of the regression, which contributed to the variation in autonomous motivation for teaching (F (3, 353) = 14.476, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.110).

TABLE 3. Summary of hierarchical regression analysis for variables predicting autonomous motivation for teaching.

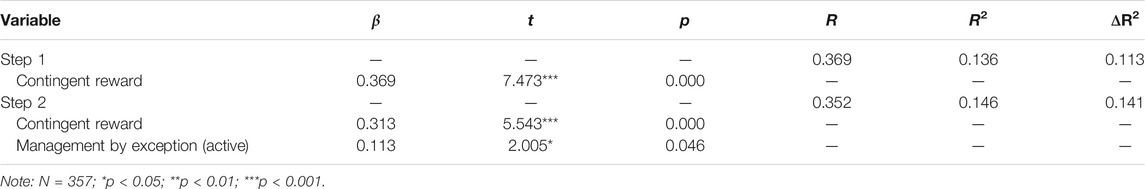

The relationship between controlled motivation and the attributes of transactional leadership [contingent reward, management by exception (active), and management by exception (passive)] were tested through a hierarchical multiple regression, which is presented in Table 4 below. Stage 1 revealed that contingent reward contributed significantly to the regression model (F (1, 355) = 55.845, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.136). In the second step of the regression, another attribute of transactional leadership, management by exception (active), was added, which explained the variation in controlled motivation for the evaluation of students; thus, the change in R2 was significant (F (2, 354) = 30.170, p < 0.000, R2 = 0.146).

TABLE 4. Summary of hierarchical regression analysis for variables predicting controlled motivation for the evaluation of students.

Discussion and Practical Implications

The current study results confirmed the impact of school principal leadership styles and practices on teachers’ work motivation. This is in alignment with previous study suggestions that school leaders’ leadership styles and practices are among the main factors in teacher’s work motivation as well as their motivation to complete specific tasks (Roth et al., 2007; Fernet et al., 2008).

Similarly to the findings of studies conducted in other worldwide contexts (Bono and Judge, 2004; Charbonneau et al., 2001; Eyal and Roth, 2010), the present study results also revealed the positive effects of transformational leadership attributes on teacher autonomous motivation, motivation for complementary tasks, and motivation for student evaluations.

The present study results suggest that the transactional leadership attributes of school principals—contingent reward, management by exception (active), management by exception (passive), and laissez-faire leadership—are also less effective compared with the transformational leadership attributes impacting teachers’ motivation to evaluate students. However, contingent reward is noted to be the only attribute of transactional leadership that results in a significant prediction of controlled motivation for the evaluation of students. In addition, it is the only measured attribute of transactional leadership style that predicts motivation for student evaluations. These results are in line with previous findings revealing that contingent reward predicts teachers’ continuance commitment. In addition, they align with study findings showing that the motivation for the delivery of a task (such as student evaluations) is predicted by contingent rewards, and task-contingent feedback is predicted by leaders, who impact teachers’ work performance (Bass and Avolio, 1994; Gagne and Deci, 2005; Cemaloğlu et al., 2012; Eyal and Roth, 2010; Gilbert and Kelloway, 2018).

The current study results confirm the influence of the leadership styles of school principals on teacher motivation for work, as well as the importance on knowing the school principals’ practices and their impact. Furthermore, the findings from this study go beyond school principals’ leadership styles and teachers’ motivation, as this relationship affects students’ evolution and academic performance (Roth et al., 2007; Robinson et al., 2008; Supovitz et al., 2010; Makgato and Mudzanani, 2019).

Given the above, while taking into consideration the important contribution of teachers’ motivation towards education quality, the current study results can serve as baseline findings which increase the awareness of educational stakeholders at multiple levels within Kosovo and other countries facing challenges with improving their education quality regarding the school principal leadership styles on teachers’ motivation for work, evaluated among the core components which can support improving school outcomes and students’ outcomes, as well as teachers’ performance and commitment to work (Cemaloğlu et al., 2012).

In addition, during the process of drafting educational policies and monitoring learning outcomes, indicators of teachers’ motivation and working environments (e.g., the support received from school directors) should be taken into account within the Kosovo education system as well as those of other low- and middle-income countries facing similar education system challenges.

Moreover, the Kosovo education system should be focused on empowering schools and teachers by making them part of the education reform process. It should also recognise teachers as professionals who can contribute to improving the quality of the education provided, and it should support them in overcoming potential barriers which will impact their professional development and motivation for work. The education system should additionally support school directors in assessing teachers’ needs and in taking the necessary steps to improve their management and leadership styles to support students’ learning and teachers’ work motivation. Furthermore, it is necessary to understand the influencing factors in teachers’ motivation as well as the various levels of teachers’ motivation to reform the education system. As Jesus and Conboy (2001) suggested, motivated teachers are more likely to implement educational reforms, and such teacher engagement is an important determinant of students’ academic success (Jesus and Conboy, 2001).

The current study results can also serve as a baseline finding for increasing awareness regarding the importance of principal support for teachers’ work motivation as a direct contributor to student learning. Thus, school leaders should consider adapting their practices by supporting teachers’ autonomous motivation, autonomy, competence, and relatedness while conducting their work tasks (Ahn, 2014). Furthermore, although school principals should also work towards improving institutional planning and instructional management (Sawati et al., 2013), autonomous motivation as a more long-lasting and promising motivation for teachers should be the principals’ target objective.

As other researchers from the field previously argued, poor management can have a negative impact on teachers’ motivation, regardless of their levels of commitment and energy (Dembélé and Rogers, 2013). Therefore, educational policymakers should direct greater focus towards school principals’ leadership practices to cultivate teachers who are motivated and prepared to meet ever-changing social needs. Moreover, policymakers and educational leaders should overcome the current challenges and improve the quality of education through better management and through designing evidence-based programmes that are specific to their respective countries.

This study provides preliminary evidence for future studies to build upon. The results, although they confirmed the impact of school principals’ leadership styles on teachers’ motivation, do not include the perspectives of school leaders and students. Further research is needed to gain a deeper understanding of the overall factors influencing school principals’ leadership styles, teachers’ autonomy and motivation to work, and students’ learning. As Schmidt and White (2004) suggested, no educational change can be successful without involving the final beneficiaries, such as teachers, students, and school administrators (Islami, 2018). Future research studies that assess school leaders’ professional development need to focus on how leaders’ overall management skills, the support they give their staff, their goal setting, and their progress monitoring can help leaders to eventually enhance their roles and improve the education quality. Previous studies on educational leadership suggest that school principals’ leadership plays a major role in educational reforms. This indicates that although the education system can provide policy directions for schools, the school system is contingent on the motivations and actions of leaders at the school level (Moos and Huber, 2007; Leithwood et al., 2008).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author Contributions

ZHD is an associate professor at the Department of Psychology, University of Prishtina Hasan Prishtina. Her research interests include multilevel factors that influence the quality of education, from preschool to higher education. Within the past years, within her research and professional work she has been continuously engaged on contributing toward assessing the factors contributing on identifying and supporting teachers motivation for work, preventing from burn out and enhancing students learning. Furthermore she has been engaged in assessing the needs and supporting the professional development of preschool teachers as well as assessing the impact of the professional development on teachers’ level of knowledge and skills, motivation to work and self-efficacy. LH is a Teaching Assistant at the Department of Psychology, University of Prishtina since 2013. Ms. Hoxha holds a PhD from Ludwig Maximilians University in Psychology with thesis “Conceptions of Kosovar employees on Creative Leadership: An exploratory design with mixed methods” and MA from Ludwig Maximilians University, in Psychology of Excellence in Business and Education and BA in Psychology from Department of Psychology, University of Prishtina. Her research work and interests include leadership, creativity, personality traits, motivational factors, parenting styles and education.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer BS declared a shared affiliation, though no other collaboration, with the authors to the handling Editor.

Footnotes

1In the leadership styles literature, transformational leadership styles are usually measured and described through four core attributes: Idealised influence and inspirational motivation are observed in leaders who not only act as role models and have a clear picture of the future and the steps needed to achieve a particular aim but also articulate these processes to their followers with confidence and fortitude. Inspirational motivation is seen as an attribute that is expressed after the idealised influence (i.e., charisma; Bass, 1999). Intellectual stimulation is another attribute of transformational leadership that is achieved in cases when leaders encourage and inspire followers to develop and maximise their potential and become more innovative and creative. Meanwhile, individual consideration is characterised by supporting and coaching followers and understanding their needs (Bass, 1999).

2Autonomy refers to the needs for choice and control, competence refers to the feeling of impacting one’s environment and achieving valued outcomes, and relatedness is the sense of belonging and the feeling of being valued by others (Deci and Ryan, 2000; Niemiec and Ryan, 2009).

References

Ahn, I. (2014). Relations between Teachers’ Motivation and Students’ Motivation: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Open Access Theses 725. doi:10.1037/e560802014-001 Available at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_theses/725

Alfahad, H., Alhajeri, S., and Alqahtani, A. (2013). The Relationship between School Principals' Leadership Styles and Teachers' Achievement Motivation. Chin. Business Rev. 12. doi:10.17265/1537-1506/2013.06.008

Aliu, L. (2019). How they can become more autonomy supportive. Analysis of Kosovo’s Education System. Friedrich Ebert Foundation Educational Psychol. 44 (3), 159–175. Available at: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/kosovo/15185-20190220.pdf.

Aydin, A., Sarier, Y., and Uysal, S. (2013). The Effect of School Principals’ Leadership Styles on Teachers’ Organizational Commitment and Job Satisfaction. Educ. Sci. Theor. Pract. 13 (2), 806–811. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1017309

Barnett, K., and McCormick, J. (2003). Vision, Relationships and Teacher Motivation: A Case Study. J. Educ. Admin 41 (1), 55–73. doi:10.1108/09578230310457439

Bass, B. M. (1999). Two Decades of Research and Development in Transformational Leadership. Eur. J. Work Organizational Psychol. 8 (issue), 9–32. doi:10.1080/135943299398410

Bass, B. M., and Avolio, B. J. (1994). Improving Organizational Effectiveness through Transformational Leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bass, B. M., and Avolio, B. J. (2000). MLQ Multifactor Leadership Questionnnaire Redwood City. Mind Garden. doi:10.21236/ada382244

Bass, B. M., and Avolio, B. J. (1993). Transformational Leadership and Organizational Culture. Public Adm. Q. 17, 112–121. Available at: www.jstor.org/stable/40862298.

Bass, B. M. (1997). Does the Transactional-Transformational Leadership Paradigm Transcend Organizational and National Boundaries?. Am. Psychol. 52 (2), 130–139. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.52.2.130

Bass, B. M., and Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Ethics, Character, and Authentic Transformational Leadership Behavior. Leadersh. Q. 10 (issue), 181–217. doi:10.1016/s1048-9843(99)00016-8

Blatt, D. A. (2002). A Study to Determine the Relationship between the Leadership Styles of Career Technical Directors and School Climate as Perceived by Teachers. Dissertation Abstracts International 63 (12), A, AAI3076358.

Blum, R. W., Bastos, F. I., Kabiru, C. W., and Le, L. C. (2012). Adolescent Health in the 21st century. Lancet 379 (issue), 1567–1568. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60407-3

Bogler, R. (2001). The Influence of Leadership Style on Teacher Job Satisfaction. Educ. Adm. Q. 37 (5), 662–683. doi:10.1177/00131610121969460

Bono, J. E., and Judge, T. A. (2004). Personality and Transformational and Transactional Leadership: A Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 89 (5), 901–910. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.901

Bourn, D., Hunt, F., and Bamber, P. (2017). A Review of Education for Sustainable Development and Global Citizenship Education in Teacher Education. Available at:https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000259566.

Bush, T., Bell, L., and Middlewood, D. (2010). Introduction: New Directions in Educational Leadership. principles Educ. Leadersh. Manag., 3–12.

Cemaloğlu, N., Sezgin, F., and KılınçÇ, A. (2012). Examining the Relationships between School Principals’ Transformational and Transactional Leadership Styles and Teachers’ Organizational Commitment. Online J. New Horizons Education 2 (2), 53–64. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1017309.pdf

Chapman, E. (2003). Alternative Approaches to Assessing Student Engagement Rates. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 8 (13), 1–10. doi:10.7275/3e6e-8353

Charbonneau, D., Barling, J., and Kelloway, E. K. (2001). Transformational Leadership and Sports Performance: The Mediating Role of Intrinsic Motivation1. J. Appl. Soc. Pyschol 31 (7), 1521–1534. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb02686.x

Crighton, J., Bakker, S., Beijlsmit, L., Crisan, A., Hunt, E., Gribben, A., et al. culture (2001). Thematic Review of National Policies for Education–Kosovo. Organisation Econ. Cooperation DevelopmentPublic Adm. Q. 17 (1), 112–121. Available at: http://search. oecd. org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The "What" and "Why" of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11 (4), 227–268. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli1104_01

Dembélé, M., and Rogers, F. H. (2013). “More and Better Teachers: Making the Slogan a Reality,” in More and Better Teachers for Quality Education for All: Identity and Motivation, Systems and Support. Editors J. Kirk, M. Dembélé, and S. Baxter, 174–180.

Eyal, O., and Roth, G. (2011). Principals' Leadership and Teachers' Motivation. J. Educ. Admin 49 (3), 256–275. doi:10.1108/09578231111129055

Fazel, M., Patel, V., Thomas, S., and Tol, W. (2014). Mental Health Interventions in Schools in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries. The Lancet Psychiatry 1 (5), 388–398. doi:10.1016/s2215-0366(14)70357-8

Fernet, C., Senécal, C., Guay, F., Marsh, H., and Dowson, M. (2008). The Work Tasks Motivation Scale for Teachers (WTMST). J. Career Assess. 16 (2), 256–279. doi:10.1177/1069072707305764

Fuller, J. B., Patterson, C. E. P., Hester, K., and Stringer, D. Y. (1996). A Quantitative Review of Research on Charismatic Leadership. Psychol. Rep. 78 (1), 271–287. doi:10.2466/pr0.1996.78.1.271

Gagné, M., and Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination Theory and Work Motivation. J. Organiz. Behav. 26, 331–362. doi:10.1002/job.322

Geijsel, F., Sleegers, P., Leithwood, K., and Jantzi, D. (2003). Transformational Leadership Effects on Teachers' Commitment and Effort toward School Reform. J. Educ. Admin 41 (3), 228–256. doi:10.1108/09578230310474403

Gilbert, S., and Kelloway, E. K. (2018). Self-determined Leader Motivation and Follower Perceptions of Leadership. Leadersh. Organ. Development J. 39 (5), 609–619. doi:10.1108/lodj-09-2017-0262

Hallinger, P. (2018). Bringing Context Out of the Shadows of Leadership. Educ. Management Adm. Leadersh. 46 (1), 5–24. doi:10.1177/1741143216670652

Hartinah, S., Suharso, P., Umam, R., Syazali, M., Lestari, B. D., Roslina, R., et al. (2020). Teacher's Performance Management: The Role of Principal's Leadership, Work Environment and Motivation in Tegal City, Indonesia. 10.5267/j.msl 10 (1), 235–246. doi:10.5267/j.msl.2019.7.038

HEART (2011). Rapid Review of Education Systems Research in Low and Middle Income Countries. Health Education Advice Resource Team. Available at:https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08a1140f0b652dd000548/Rapid-review-of-Education-Systems-Research-in-Low-and-Middle-Income-Countries-1.pdf.

Jesus, S. N., and Conboy, J. (2001). A Stress Management Course to Prevent Teacher Distress. Int. J. Educ. Management 15 (3), 131–137.

Judge, T. A., and Piccolo, R. F. (2004). Transformational and Transactional Leadership: a Meta-Analytic Test of Their Relative Validity. J. Appl. Psychol. 89 (5), 755–768. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.755

Kanat-Maymon, Y., Elimelech, M., and Roth, G. (2020). Work Motivations as Antecedents and Outcomes of Leadership: Integrating Self-Determination Theory and the Full Range Leadership Theory. Eur. Management J. 38 (4), 555–564. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2020.01.003

Kotherja, O. (2013). Teachers’ Motivation Importance and Burnout Effect in the Educational Development: Albania International Conference on Education, Epoka University. Available at: http://dspace.epoka.edu.al/handle/1/800.

Krüger, M. L., Witziers, B., and Sleegers, P. (2007). The Impact of School Leadership on School Level Factors: Validation of a Causal Model. Sch. Effectiveness Sch. Improvement 18 (1), 1–20. doi:10.1080/09243450600797638

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., and Hopkins, D. (2008). Seven strong Claims about Successful School Leadership. Sch. Leadersh. Management 28 (1), 27–42. doi:10.1080/13632430701800060

Leithwood, K., and Jantzi, D. (2005). A Review of Transformational School Leadership Research 1996–2005. Leadersh. Pol. Schools 4, 177–199. doi:10.1080/15700760500244769

Leithwood, K., and Jantzi, D. (2008). Linking Leadership to Student Learning: The Contributions of Leader Efficacy. Educ. Adm. Q. 44 (4), 496–528. doi:10.1177/0013161x08321501

Leithwood, K., Jantzi, D., and Steinbach, R. (1999). Changing Leadership for Changing Times: Changing Education Series. London: Open University Press.

Leithwood, K., and Jantzi, D. (2006). Transformational School Leadership for Large-Scale Reform: Effects on Students, Teachers, and Their Classroom Practices. Sch. Effectiveness Sch. Improvement 17 (2), 201–227. doi:10.1080/09243450600565829

Leithwood, K. (1994). Leadership for School Restructuring. Educ. Adm. Q. 30 (4), 498–518. doi:10.1177/0013161x94030004006

Leithwood, K., and Mascall, B. (2008). Collective Leadership Effects on Student Achievement. Educ. Adm. Q. 44 (4), 529–561. doi:10.1177/0013161x08321221

Leithwood, K., and Steinbach, R. (1991). Indicators of Transformational Leadership in the Everyday Problem Solving of School Administrators. J. Pers Eval. Educ. 4 (3), 221–244. doi:10.1007/bf00125486

Makgato, M., and Mudzanani, N. N. (2019). Exploring School Principals' Leadership Styles and Learners' Educational Performance: A Perspective from High- and Low-Performing Schools. Africa Education Rev. 16 (2), 90–108. doi:10.1080/18146627.2017.1411201

Ministry of Education and Science (2016). Kosovo Education Strategic Plan 2017-2021. Ministry of Education, Science and Technolgy, MEST. Kosovo. Retrieved from: http://www.kryeministri-ks.net/repository/docs/KOSOVO_EDUCATION_STRATEGIC_PLAN.pdf.

Moos, L., and Huber, S. (2007). School Leadership, School Effectiveness and School Improvement: Democratic and Integrative Leadership. in International Handbook of School Effectiveness and Improvement. Dordrecht: Springer.

Nikoçeviq, E. (2012). The Role of Capacity-Building for School Decentralization in Kosovo. Probl. Education 21st Century 41, 52, 2012. Available at: http://www.scientiasocialis.lt/pec/files/pdf/vol41/52-60.Nikoceviq_Vol.41.pdf

Rama, S. (2011). Professor's Performance for Effective Teaching (Kosovo Case). Proced. - Soc. Behav. Sci. 12, 117–121. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.02.015

Raman, A., Cheah, H. M., Don, Y., Daud, Y., and Khalid, R. (2015). Relationship between Principals’ Transformational Leadership Style and Secondary School Teachers’ Commitment. Asian Soc. Sci. 11 (15), 221–228. doi:10.5539/ass.v11n15p221

Reeve, J. (2009). Why Teachers Adopt a Controlling Motivating Style toward Students and How They Can Become More Autonomy Supportive. Educ. Psychol. 44 (3), 159–175. doi:10.1080/00461520903028990

Robinson, V. M. J., Lloyd, C. A., and Rowe, K. J. (2008). The Impact of Leadership on Student Outcomes: An Analysis of the Differential Effects of Leadership Types. Educ. Adm. Q. 44 (5), 635–674. doi:10.1177/0013161x08321509

Roth, G., Assor, A., Kanat-Maymon, Y., and Kaplan, H. (2007). Autonomous Motivation for Teaching: How Self-Determined Teaching May lead to Self-Determined Learning. J. Educ. Psychol. 99 (4), 761–774. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.761

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2009). Promoting Self-Determined School Engagement: Motivation, Learning, and Well-Being.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25 (1), 54–67. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Ryan, R. M. (1995). Psychological Needs and the Facilitation of Integrative Processes. J. Personal. 63 (3), 397–427. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00501.x

Ryan, R. M., Rigby, S., and King, K. (1993). Two Types of Religious Internalization and Their Relations to Religious Orientations and Mental Health. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 65 (3), 586–596. Available at: www.jstor.org/stable/40862298doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.3.586

Sawati, M. J., Anwar, S., and Majoka, M. I. (2013). Do qualification, Experience and Age Matter for Principals’ Leadership Styles?. Int. J. Acad. Res. Business Soc. Sci. 3 (7), 403–413. doi:10.6007/ijarbss/v3-i7/63

Sawyer, S. M., Afifi, R. A., Bearinger, L. H., Lastname, X., Lastname, Y., Lastname, Z., et al. (2012). Adolescence: A Foundation for Future Health. Lancet 379, 1630–1640. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60072-5

Schmidt, M., and White, R. E. (2004). Educational Change: Putting Reform into Perspective. J. Educ. Change 5 (3), 207–211. doi:10.1023/b:jedu.0000041040.55866.12

Shamir, B., House, R. J., and Arthur, M. B. (1993). The Motivational Effects of Charismatic Leadership: A Self-Concept Based Theory. Organ. Sci. 4 (4), 577–594. doi:10.1287/orsc.4.4.577

Shkëmbi, F., Melonashi, E., and Fanaj, N. (2015). Workplace Stress Among Teachers in Kosovo. SAGE Open 5 (4), 2158244015614610. doi:10.1177/2158244015614610

Supovitz, J., Sirinides, P., and May, H. (2010). How Principals and Peers Influence Teaching and Learning. Educ. Adm. Q. 46 (1), 31–56. doi:10.1177/1094670509353043

Tajasom, A., and Ahmad, Z. A. (2011). Principals' Leadership Style and School Climate: Teachers' Perspectives from Malaysia. Int. J. Leadersh. Public Serv.

United Nations Development Program (2015). Corruption-risk Assessment in the Kosovo Education Sector: Findings and Recommendations. Available at:https://etico.iiep.unesco.org/sites/default/files/UNDP%2520CorruptionEdu_report_ENG.pdf.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2018). International Task Force on Teachers for Education 2030: Strategic Plan 2018–2021. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261708.

Yukl, G. A., and Becker, W. S. (2006). Effective Empowerment in Organizations. Organ. Management J. 3 (3), 210–231. doi:10.1057/omj.2006.20

Keywords: school principal, leadership style, teacher motivation to work, middle school, work experience

Citation: Hyseni Duraku Z and Hoxha L (2021) Impact of Transformational and Transactional Attributes of School Principal Leadership on Teachers’ Motivation for Work. Front. Educ. 6:659919. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.659919

Received: 28 January 2021; Accepted: 17 May 2021;

Published: 02 June 2021.

Edited by:

Margaret Terry Orr, Bank Street College of Education, United StatesReviewed by:

Timothy Mark O’Leary, University of Melbourne, AustraliaBlerim Saqipi, University of Prishtina, Kosovo

Copyright © 2021 Hyseni Duraku and Hoxha. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Linda Hoxha, bGluZGEuaG94aGFAdW5pLXByLmVkdQ==

Zamira Hyseni Duraku

Zamira Hyseni Duraku Linda Hoxha

Linda Hoxha