94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Educ. , 05 May 2021

Sec. Special Educational Needs

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.655356

The positive attitudes of teachers toward inclusive education appear to be necessary to successfully implement this policy. The present research, conducted within the French context, seeks to replicate the previous findings regarding students’ type of disability or teachers’ status and extend them by specifically examining the interaction between these two variables. We notably hypothesized that (1) teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education will be the least positive for students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), in comparison with students with cognitive disorder (CD) and students with motor impairment (MI); (2) special education teachers will have more positive attitudes than general teachers; and more importantly (3) special education teachers, in comparison with general teachers, would be less likely to express distinct attitudes depending on the students’ type of disability. An online questionnaire was completed by 311 teachers. The results replicated the previous findings by showing that teachers’ attitudes were more favorable toward students with MI than students with CD or students with ASD. In addition, taking into account teachers’ status, the results showed that if special education teachers had more positive attitudes than general teachers, they, however, expressed less favorable attitudes toward the inclusion of students with ASD in comparison with those with other types of disabilities. These results are notably discussed regarding the lay beliefs associated with students with ASD and the influence of training.

The World Conference on Special Needs Education (UNESCO, 1994) reaffirmed that every child has the right to attend class within the regular education system, to be supported in their learning, and to participate in all aspects of school life. In line with this principle, there has been an increasing trend toward including students within the mainstream system, regardless of their disabilities. This trend was triggered by legal requirements: for example, in France, since 2005 (and with the enactment of additional legislations), the education system has promoted transformations aiming to counteract the social exclusion of these students (e.g., a 3 year-old pupil with disability is now automatically registered within the closest school from his/her home and even if he/she benefits from additional support from a special education class, he/she still belongs to his/her general grade). Such policy is promising since empirical evidence has brought to light encouraging benefits for all students regarding both their academic performance and their social competence (for a review, see Ruijs and Peetsma, 2009). Nevertheless, despite these benefits, teachers continue to report encountering difficulties that prevent them from fully embracing inclusive policy (Hind et al., 2019).

Although including students with motor impairment (MI) (e.g., wheelchair-bound students) may no longer be a problem for teachers, including students with intellectual or psychological difficulties in the mainstream system can be genuinely challenging (Vaillancourt, 2017). The reluctance to include is particularly strong for students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) compared with other disabilities (Praisner, 2003; Jury et al., 2021). For example, 65% of French teachers still believe that these students should be taught in special education schools (OpinionWay survey for “Le Collectif Autisme,” conducted on March 17, 2011). The present study attempts to use these results as a springboard to expand knowledge regarding the attitudes of teachers toward inclusive education. Notably, we sought to examine, within the French context, how two well-known antecedents—students’ type of disability (e.g., ASD, CD, and MI) and teachers’ status (i.e., referring here either to general or special education teachers)—specifically interact to determine the attitudes of teachers.

Teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education, in its simplest definition, refer to the viewpoints or dispositions of teachers toward the particular “object” of inclusive education. The above-said viewpoint may consist of beliefs about teaching students with disability in inclusive settings (i.e., the cognitive component of attitudes), feelings associated with the teaching to these students (i.e., the affective component), and/or actions encouraging their inclusion (i.e., the behavioral component). It is important to study such constructs, since they could predict teachers’ involvement in inclusive practices (Sharma and Sokal, 2016).

If most teachers seem sincerely convinced of the importance of including students within the mainstream system, those same teachers sometimes associate disability with negative features and express attitudes accordingly. In other words, teachers can be openly favorable toward the inclusion of students with disability but also harbor fears about what disability represent for their teaching practices. As an illustration, some previous studies identified that teachers declare positive attitudes toward the general idea of inclusive education (for recent examples, see Krischler and Pit-ten Cate, 2018; Lüke and Grosche, 2018), all the while expressing serious concerns regarding the application of inclusive education in their own classrooms (for a recent meta-analysis, see van Steen and Wilson, 2020).

Teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education are known to be influenced by a large number of parameters (for a review, see Avramidis and Norwich, 2002). For example, they could vary as a function of educational policy in a country (Takala et al., 2012; Saloviita and Schaffus, 2016), academic support (Urton et al., 2014), or the grasp of inclusive education policy of educators (Krischler et al., 2019). Additionally, students’ type of disability also strongly influences these attitudes.

Reviewing the scientific literature, de Boer et al. (2011) presented studies showing that students with emotional and behavioral difficulties as well as those with profound and manifold learning difficulties are perceived as the most difficult to include. In the same vein, Benoit (2016) showed that the attitudes of teachers were more negative for students with behavioral difficulties or sensory disability (e.g., deaf and blind students), especially when compared with those with learning difficulties. She concluded that teachers perceived some disabilities as harder to overcome than others and therefore comparatively more reluctant to include students with such perceived difficulties. Therefore, the attitudes of teachers may depend on the extent to which instructional practices could be easily modified to accommodate the curricula (Center and Ward, 1987) as well as the severity of students’ disability.

As a first goal of the present study, based on the aforementioned results, we sought to replicate findings indicating that teachers’ attitudes depend on students’ type of disability. To be more specific, since students with ASD and cognitive disorder (CD) require more radical alteration of instructional practices (e.g., highlighting critical information, providing detailed and clear instructions on classroom assignments, preparing the student for daily or weekly activities, see Marks et al., 2003) than students with MI, we hypothesized that teachers’ attitudes toward the inclusion of students with ASD and students with CD are less positive than that of those toward the inclusion of students with MI, because they challenge the regular teaching practices. In addition, since students with ASD can exhibit behaviors affecting their relationships with teachers and peers (e.g., difficulties with communication and social interaction, persistent patterns of restricted and stereotyped behaviors), we hypothesized that teachers’ attitudes toward the inclusion of these students are less positive than that of those toward the inclusion of students with CD.

Additionally, the influence of teachers’ characteristics, specifically, age, gender, and teaching experience, has been widely studied in the literature. However, the authors indicated that the results regarding these factors are somewhat muddled and inconclusive (de Boer et al., 2011). For example, some studies have shown a difference between female and male teachers (i.e., female teachers are more favorable to inclusive education than male teachers, Vaz et al., 2015), while some others have not (see, e.g., Benoit, 2016). Nonetheless, the literature has more consistently identified a difference in teachers’ attitudes based on their teaching status. Indeed, research has highlighted that general teachers (i.e., those who teach in mainstream education) usually have less favorable attitudes compared with their special education counterparts (i.e., teachers who benefit from specialized training and teach students with special educational needs in mainstream or special education, Desombre et al., 2019). This is the case at both explicit (i.e., attitudes overtly assumed, Desombre et al., 2019) and implicit levels (more automatic responses, Wüthrich and Sahli Lozano, 2018).

Several studies have attempted to shed light on the potential causes of this difference. Notably, Desombre et al. (2019) found that general teachers express less favorable attitudes than special education teachers, and that this is partly due to their lower level of general teaching efficacy. In the same vein, Tournaki and Samuels (2016) showed that administering the same course on inclusion-based curricula improved the attitudes of both general education and special education teachers, but that positive effects continued to impact only special education teachers at least 1,5 years longer. One may therefore conclude that a better inclusive education training (this specific course was part of a curriculum dedicated to inclusive practices) allows special education teachers to significantly increase their knowledge, effectively guarding them against negative attitudes toward inclusive education (for a review of interventions that improve the attitudes of teachers, see Lautenbach and Heyder, 2019). As a second goal of the present study and based on the previous results (Wüthrich and Sahli Lozano, 2018; Desombre et al., 2019), we, therefore, expected to replicate the results showing that special education teachers harbor more positive attitudes than general teachers.

If replicating findings is particularly important (see Open Science Collaboration, 2017), the main goal of the present study is above all to explore the extent to which students’ type of disability could also influence the attitudes of special education teachers. Indeed, since these teachers are trained to deal with a variety of situations and special educational needs, we believed that their familiarity can reduce their sensitivity to specific sets of difficulties faced by the students. In other words, studying the interaction between students’ type of disability and the teachers’ status would specifically allow us to test the hypothesis assuming that special education teachers, in comparison with general teachers, would be less likely to express attitudes that vary according to students’ type of disability.

To sum up, we expected that (H1) the attitudes of teachers will be the least positive for students with ASD, in comparison with that for those with CD and those with MI; (H2) special education teachers will have more positive attitudes than general teachers; and (H3) special education teachers, in comparison with general teachers, would be less likely to express distinct attitudes depending on students’ type of disability.

It should be noted that the present study will be conducted within the French context. Congruently with the ratification of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2010, France has recently developed a policy regarding inclusive education (for more information regarding the specificities of the French system, see notably Desombre et al., 2019; Rattaz et al., 2020). Replicating previous findings in this context is important to allow comparisons with educational systems in which inclusive policies are much older (e.g., Italy, Saloviita and Consegnati, 2019).

Three hundred and fifty-one teachers from several French regions participated voluntarily in this study. However, 40 participants did not complete the demographic information section and were removed from the sample (because it was impossible to get their teaching status). The final sample (a classical convenience one) included 62 men and 249 women with a mean age of 38.41 years (SD = 9.12). Two hundred and forty-five participants were general teachers and 66 participants were special education teachers. One hundred and thirty-eight participants taught in elementary schools and 173 taught post-elementary grades (middle school and high school). Overall, participants possessed a mean teaching experience of 13.05 years (SD = 9.35). General and special education teachers did not differ in terms of age, [t(120.61) = 1.02, p = 0.31], but did have different levels of teaching experience (i.e., general teachers had more experience than special education teachers in our sample), [t(121.27) = 2.07, p = 0.04].

Participants completed a questionnaire inspired by the one developed by Mahat (2008, one of the most psychometrically sound questionnaires regarding this question, Ewing et al., 2018). In her original scale, the author proposed a measure to assess the cognitive, affective, and behavioral components of the attitudes of teachers toward inclusive education. In the present study, nine items were extracted from this questionnaire (i.e., three items for each component to recompose for each type of disability, a measure with the three subcomponents) and were slightly adapted to measure the attitudes of teachers depending on the students’ type of disability [i.e., “students with a disability” in the original items was replaced by “students with (type of disability)” in the present scale]. Thus, three items assessed the attitudes of teachers toward students with ASD (α = 0.80, M = 3.38, SD = 0.95), three items assessed the attitudes of teachers toward students with CD (α = 0.78, M = 3.79, SD = 0.86), and three items assessed the attitudes of teachers toward students with MI (α = 0.77, M = 4.38, SD = 0.71). Participants filled in the questionnaire using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree). The order of these measures was counterbalanced between participants.

To ensure that our short scale is able to highlight a general attitude toward students with disability, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted on these nine items with oblique rotation (oblimin). The Kayser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure was 0.83, and all KMO values for individual items > 0.80 reached a satisfactory threshold for conducting an exploratory factor analysis (Field, 2009). This analysis revealed that only one component had an eigenvalue over Kaiser’s criterion of 1, which explained 42.31% of the variance. All items were loaded on this factor at a satisfactory level (>0.49). This single-factor solution indicates that regardless of the type of disability of students, it seems that all items used here assessed the same concept, teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education.

Based on this preliminary analysis and since no hypotheses were formulated on the three distinct components of attitudes cited earlier, the general mean scores for the three measures were used. All material and data regarding this project can be accessed here: https://osf.io/jak6c/.

Participants were invited to participate in an online study during the spring semester of the 2017–2018 school year. The email informed them about the purpose as well as the procedure of this study. They notably learned that their participation was voluntary, they could quit the study without negative consequences, and they would not receive any financial compensation. Once consent was given, participants were asked to fill in the questionnaire. In the end, they received further details regarding the goal of this study.

It should be noted that the data for this study were collected in the context of larger projects; none of the findings from the research herein have been presented in any previous study. In this research, no data exclusions were used, all data were collected before any analyses were conducted, and all variables analyzed are reported.

Since age, gender, and teaching experiences are sometimes known to influence teachers’ attitudes according to the literature, a preliminary analysis was conducted controlling for the influence of these parameters. In this analysis, a model encompassing the status, age, gender, teaching experiences of teachers, and level of schooling in addition to students’ type of disability was tested. Since none of these variables influenced the attitudes of teachers (all p > 0.12), they were removed from the final model.

A repeated measure ANOVA was conducted with students’ type of disability as a within factor at three levels (i.e., ASD, CD, and MI) and the status of participants (general vs. special education teachers) as a between-factor. It bears noting that the Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated, p < 0.001, therefore degrees of freedom were corrected using Huynh–Feldt estimates of sphericity (ε = 0.94).

Regarding our first hypothesis, the analysis showed that students’ type of disability influences the attitudes of participants, [F(1.88, 580.62) = 125.22, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.29]. Indeed, post hoc analyses with Bonferroni correction confirmed that teachers’ attitudes toward the inclusion of students with ASD (M = 3.42, SE = 0.05) are less positive than that of those regarding the inclusion of students with CD (M = 3.84, SE = 0.05) who themselves are less positive and that of those regarding the inclusion of students with MI (M = 4.30, SE = 0.05), all p < 0.001.

Regarding our second hypothesis, the results confirmed that general teachers (M = 3.63, SE = 0.06) expressed less favorable attitudes than special education teachers (M = 4.08, SE = 0.06), [F(1, 309) = 23.11, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.07].

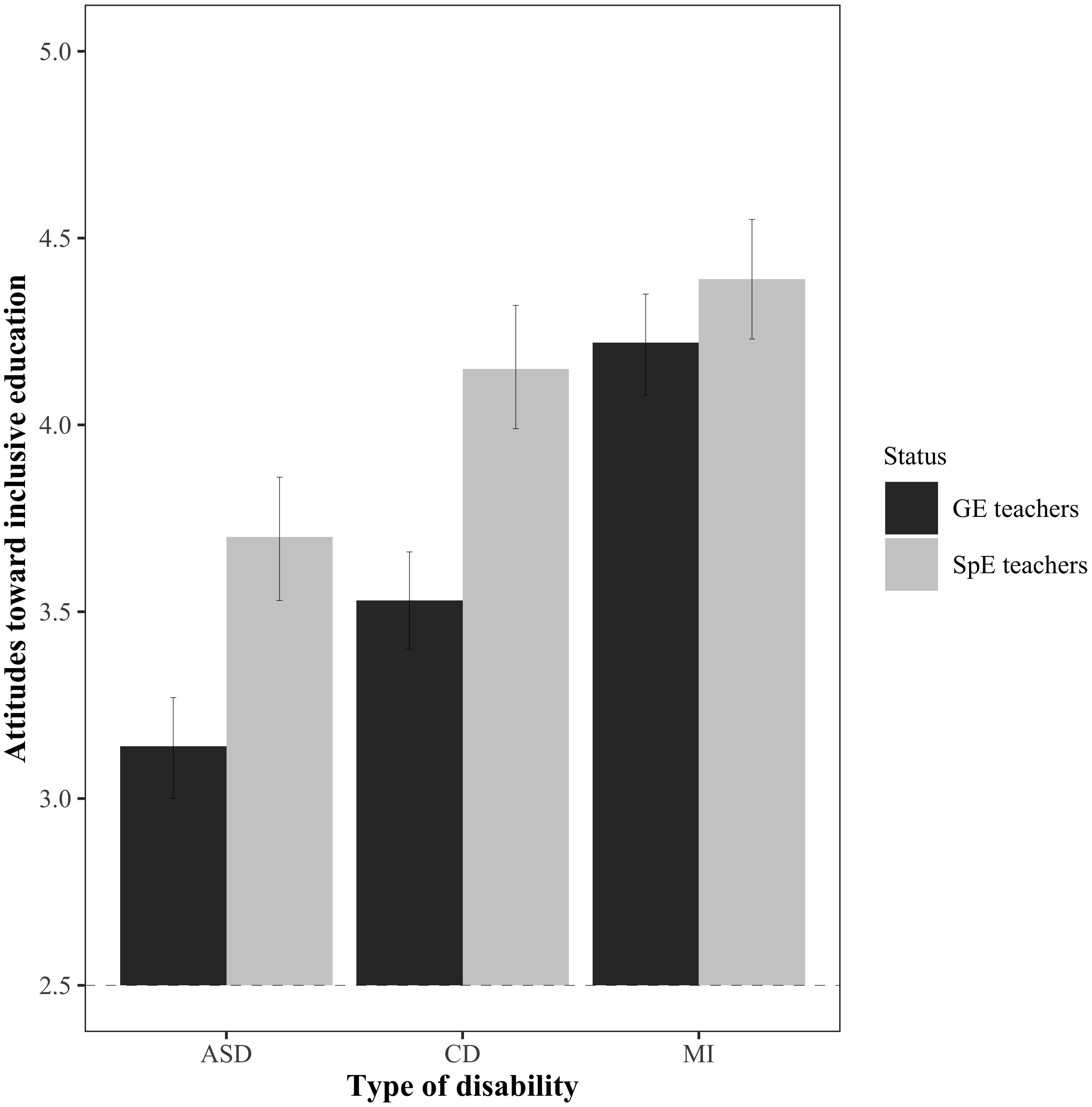

Finally, regarding our third and main hypothesis, the results indicated an interaction between the status of participants and the type of disability, [F(1.88, 580.62) = 9.49, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03]. As illustrated in Figure 1 and the post hoc analyses with Bonferroni correction, it seems that general teachers (MASD = 3.14, SEASD = 0.07; MCD = 3.53, SECD = 0.07) expressed less favorable attitudes toward the inclusion of students with ASD or CD than special education teachers (MASD = 3.70, SEASD = 0.08; MCD = 4.15, SECD = 0.08; all p < 0.001) but did not differ regarding students with MI (MGE = 4.22, SEGE = 0.07; MSpE = 4.39, SESpE = 0.08, p = 1). However, it should be noted that though general teachers produced the trend described previously (all p < 0.001), special education teachers also expressed more positive attitudes toward the inclusion of students with MI and CD in comparison with students with ASD (p < 0.001). No differences appeared between students with MI and CD for these ones, p = 0.26. Altogether, these results support our first and second hypotheses but partly the third one.

Figure 1. The mean attitudes of participants depending on their status (GE, general education teachers; SpE, special education teachers) and the type of disability of students (ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CD, cognitive disorder; MI, motor impairment). Errors bars represent 95% CIs.

Inclusion is conceptualized as an active process which is able to reduce barriers to mainstream schooling, academic, and social achievements of all students. This definition fits the systemic approach that contrasts disability and social inclusion. In this actual conception, the role of environmental factors is emphasized in the emergence of inclusion vs. the influence of impairment on the situation. The ability of impairment to create disability is more negligible when the physical and human barriers are removed (Hick et al., 2009). In this perspective, the attitudes of teachers toward inclusive education can constitute a key factor in ensuring that inclusion becomes a reality for all students (Rousseau et al., 2013), and the aim of the present research was threefold. First, we wanted to evaluate conditions favorable to teachers’ adoption of positive attitudes. Thus, we sought to verify the extent to which students’ type of disability can influence the attitudes of teachers (Avramidis et al., 2000). Due to the perceived cost associated with the inclusion of some students, we expected that the teachers’ attitudes toward the inclusion of students with CD and ASD would be less positive compared with that of those toward the inclusion of students with MI. In addition, due to the potentially disruptive behaviors of students with ASD, we expected that the attitudes of teachers toward the inclusion of these students would be less positive, in comparison with that of those toward the inclusion of students with CD. Second, we sought to replicate the earlier findings regarding the impact of teachers’ status on their attitudes and postulated that special education teachers would endorse more positive attitudes than general education teachers (see Desombre et al., 2019). Third and more importantly, we sought to test the extent to which teachers’ status can constitute a favorable environmental factor to non-differentiation between students according to their type of disabilities. Thus, we hypothesized that special education teachers would be less likely to express distinct attitudes as a function of this parameter.

Our results partly confirmed our predictions. Indeed, if our first two hypotheses appeared to be substantiated by the data, our third one seems to be only partly supported. Surprisingly, the specificities in students’ type of disability impacted the attitudes for general education teachers and special education teachers alike, as tested. More precisely, the results showed more negative attitudes toward the inclusion of students with ASD and CD than toward the inclusion of students with MI, and attitudes toward the inclusion students with ASD were more negative than those for students with CD. These results confirmed the previous research indicating that the inclusion of students with MI within the mainstream system no longer seems to be problematic, whereas including students with potential behavioral or learning difficulties, especially students with ASD, is problematic (Jury et al., 2021). However, as expected, the observed trend was not strictly identical for general education teachers and special education teachers. Indeed, the results showed a significant interaction demonstrating the benefit of specialized training, particularly in favor of students facing the most negative attitudes from teachers (i.e., students with ASD and CD). This result is particularly important and confirms the previous study, showing that teacher training constitutes a powerful tool for supporting inclusive education (Pit-ten Cate et al., 2018). This finding also vindicates teachers who justify their reluctance to include students with disability by citing their lack of training (Hind et al., 2019). Indeed, this study confirms that training can help special education teachers to see the inclusion of students with disability more favorably. Unfortunately, it appears that training is not the end-all solution since special education teachers also express distinct attitudes based on students’ type of disability (i.e., more negative attitudes toward students with ASD than students with CD and MI). How can we explain such a discrepancy within the attitudes of special education teachers since they should be the first to promote the inclusion of all students?

One possible reason of the above-mentioned result may reside in our experimental procedure. In order to apprehend the antecedents of teachers’ attitudes, we specifically decided to study and manipulate students’ type of disability; in other words, we focused attention on specific impairments. By doing so, the design probably led participants to think through the perceived difficulties, instead of the associated special educational needs. As a consequence, the attitudes of participants could have been colored by their stereotypical beliefs regarding these specific disabilities. It has notably been shown that individuals with CD are perceived as particularly kind (Sadler et al., 2012) while individuals with ASD suffer from a generally negative social representation, since they can be perceived as having a “disease” that makes them “inaccessible” (Dachez et al., 2016; see also Rohmer and Louvet, 2011).

In addition, using such broad categories could also have created confusion, notably regarding students with ASD. Indeed, ASD includes multiple forms of autism, named as “spectrum” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Some are associated with intellectual difficulties and challenging behaviors, while some others are not. Nevertheless, independent of this diversity, the overall negative lay representation of autism seems to dominate (Dachez et al., 2016). This homogenization that lies at the core of stereotypical perceptions, especially toward ASD, can reinforce the less positive attitudes observed, while, on the contrary, introducing variability can have the opposite effects (Brauer and Er-rafiy, 2011; Jury et al., 2021).

Therefore, despite their training, these culturally instilled lay beliefs can have automatically impacted the attitudes of special education teachers. Replicating the present study with vignettes (see, e.g., Poulou and Norwich, 2002; Donohue and Bornman, 2015) with more direct manipulation of students’ special educational needs instead of the nature of their disability (Krischler and Pit-ten Cate, 2018) may help to more clearly assess whether special education teachers also express distinct attitudes depending on the needs to be implemented.

However, two methodological issues, possibly limiting the present findings, should be highlighted. First, the convenience sample we used reduces the generalizability of the present findings. Second, using a shortened scale instead of the full one from Mahat (2008) could question the validity of our measures. A future study with vignettes, a probabilistic sample, and the full scale might help to strengthen the present results.

Regardless of the need for further investigation, the present research has provided valuable insights within the inclusive education field of study. It contributes to the previous findings on attitudes toward the inclusion of students with disability in a new context (i.e., France) and furthers our knowledge by showing that students’ type of disability also impacts the attitudes of special education teachers, despite their sensitivity to the issue of inclusive education. Although increasing the theoretical and practical knowledge dispensed to teachers could be a relevant way to improve the ability and confidence of teachers to teach in inclusive settings (for, e.g., see Forlin et al., 2014), these results could lead to the conclusion that boosting knowledge is not always sufficient to foster the inclusion of all students. Consequently, in order to identify potential leveraging methods to anchor the inclusive education paradigm, such results push researchers to come up with complementary alternatives to improve teachers’ attitudes. As an example, Li et al. (2019) recently proposed a module for preservice teachers designed to improve their attitudes toward students with ASD. In their study, they demonstrated that practices involving mindfulness (i.e., a receptive attention to and awareness of present events and experience, see Brown and Ryan, 2003) could help teachers to reduce their negative attitudes toward students with ASD by sustaining their basic psychological needs (i.e., autonomy, competence, and relatedness). Such results are consistent with those that showed that perceived competence and support are fundamental to developing positive attitudes (Urton et al., 2014). In the same vein, the training for both general and special education teachers could reduce the institutional categories regarding students with disability. Indeed, increasing the variability associated with this group (i.e., increase the perceived heterogeneity) could help to reduce potential prejudice regarding these students (Brauer and Er-rafiy, 2011).

As a consequence, to fully sustain an inclusive school system, a comprehensive view of the needs of both students (in terms of accommodation) and teachers (in terms of training, competence, and support) appears essential.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://osf.io/jak6c/.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

MJ and CD conceived and designed the study and collected the data. A-LP analyzed the data on the supervision of MJ. MJ drafted the manuscript. A-LP, OR, and CD provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

This study was funded by the Institut National Supérieur du Professorat et de l’Éducation—Lille Haut-de-France and the Caisse Nationale de Solidarité pour l’Autonomie (CNSA) (grant no. IReSP-17-AUT4-08).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We wish to thank Andgelina Andrieux, Jessica Delamarre, Estelle Delcourt, Nicolas Rousseau, and Emeline Vandewalle for their help in data collection.

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Avramidis, E., Bayliss, P., and Burden, R. (2000). Student teachers’ attitudes towards the inclusion of children with special educational needs in the ordinary school. Teach. Teach. Educ. 16, 277–293. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(99)00062-1

Avramidis, E., and Norwich, B. (2002). Teachers’ attitudes towards integration/inclusion: a review of the literature. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 17, 129–147. doi: 10.1080/08856250210129056

Benoit, V. (2016). Les Attitudes des Enseignants à L’égard de L’intégration Scolaire des Élèves avec des Besoins Éducatifs Particuliers en Classe Ordiniaire du Niveau Primaire. [Teachers’ attitudes towards students with special educational needs integration within elementary schools]. Doctoral dissertation. Fribourg: Fribourg University.

Brauer, M., and Er-rafiy, A. (2011). Increasing perceived variability reduces prejudice and discrimination. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 47, 871–881. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.03.003

Brown, K. W., and Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 84, 822–848. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

Center, Y., and Ward, J. (1987). Teachers’ attitudes towards the integration of disabled children into regular schools. Except. Child 34, 41–56. doi: 10.1080/0156655870340105

Dachez, J., N’Dobo, A., and Navarro Carrascal, O. (2016). Représentation sociale de l’autisme [Social representation of Autism Spectrum Disorders]. Les Cah. Int. Psychol. Soc. 112, 477–500.

de Boer, A. A., Pijl, S. J., and Minnaert, A. (2011). Regular primary schoolteachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: a review of the literature. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 15, 331–353. doi: 10.1080/13603110903030089

Desombre, C., Lamotte, M., and Jury, M. (2019). French teachers’ general attitude toward inclusion: the indirect effect of teacher efficacy. Educ. Psychol. 39, 38–50. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2018.1472219

Donohue, D. K., and Bornman, J. (2015). South African teachers’ attitudes toward the inclusion of learners with different abilities in mainstream classrooms. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 62, 42–59. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2014.985638

Ewing, D. L., Monsen, J. J., and Kielblock, S. (2018). Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: a critical review of published questionnaires. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 34, 150–165. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2017.1417822

Forlin, C., Sharma, U., and Loreman, T. (2014). Predictors of improved teaching efficacy following basic training for inclusion in Hong Kong. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 18, 718–730. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2013.819941

Hick, P., Kershner, R., and Farell, P. (2009). Psychology for Inclusive Education: New Directions in Theory and Practice. London: Routledge.

Hind, K., Larkin, R., and Dunn, A. K. (2019). Assessing teacher opinion on the inclusion of children with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties into mainstream school classes. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 66, 424–437. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2018.1460462

Jury, M., Perrin, A.-L., Desombre, C., and Rohmer, O. (2021). Teachers’ attitudes toward the inclusion of students with autism spectrum disorder: impact of students’ difficulties. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 83:101746. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2021.101746

Krischler, M., and Pit-ten Cate, I. M. (2018). Inclusive education in Luxembourg: implicit and explicit attitudes toward inclusion and students with special educational needs. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 24, 597–615. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2018.1474954

Krischler, M., Powell, J. J. W., and Pit-Ten Cate, I. M. (2019). What is meant by inclusion? On the effects of different definitions on attitudes toward inclusive education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 34, 632–648. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2019.1580837

Lautenbach, F., and Heyder, A. (2019). Changing attitudes to inclusion in preservice teacher education: a systematic review. Educ. Res. 61, 231–253. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2019.1596035

Li, C., Wong, N. K., Sum, R. K. W., and Yu, C. W. (2019). Preservice teachers’ mindfulness and attitudes toward students with autism spectrum disorder: the role of basic psychological needs satisfaction. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 36, 150–163. doi: 10.1123/apaq.2018-0044

Lüke, T., and Grosche, M. (2018). Implicitly measuring attitudes towards inclusive education: a new attitude test based on single-target implicit associations. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 33, 427–436. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2017.1334432

Mahat, M. (2008). The development of a psychometrically-sound instrument to measure teachers’ multidimensional attitudes toward inclusive education. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 23, 82–92.

Marks, S. U., Shaw-Hegwer, J., Schrader, C., Longaker, T., Peters, I., Powers, F., et al. (2003). Instructional management tips for teachers of students with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Teach. Except. Child. 35, 50–54. doi: 10.1177/004005990303500408

Open Science Collaboration (2017). “Maximizing the reproducibility of your research,” in Psychological Science Under Scrutiny: Recent Challenges and Proposed Solutions, eds S. O. Lilienfeld and I. D. Waldmen (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley), 1–21.

Pit-ten Cate, I., Markova, M., Krischler, M., and Krolak-Schwerdt, S. (2018). Promoting inclusive education: the role of teachers’ competence and attitudes. Learn. Disabil. World. 15, 49–63.

Poulou, M., and Norwich, B. (2002). Cognitive, emotional and behavioural responses to students with emotional and behavioural difficulties: a model of decision-making. Br. Educ. Res. J. 28, 111–138. doi: 10.1080/01411920120109784

Praisner, C. L. (2003). Attitudes of elementary school principals toward the inclusion of students with disabilities. Except. Child. 69, 135–145. doi: 10.1177/001440290306900201

Rattaz, C., Munir, K., Michelon, C., Picot, M. C., and Baghdadli, A. (2020). School inclusion in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders in France: report from the ELENA French Cohort Study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50, 455–466. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04273-w

Rohmer, O., and Louvet, E. (2011). Le stéréotype des personnes handicapées en fonction de la nature de la déficience. Une application des modèles de la bi-dimensionnalité du jugement social [Stereotype content of disability subgroups - Testing predictions of the fundamental dimensions of social judgement]. L’Ann. Psychol. 111, 69–85. doi: 10.4074/s0003503311001035

Rousseau, N., Bergeron, G., and Vienneau, R. (2013). L’inclusion scolaire pour gérer la diversité: des aspects théoriques aux pratiques dites efficaces [Inclusion for managing the diversity: from theory to efficient practices]. Rev. Suisse Sci. l’éduc. 35, 71–90.

Ruijs, N. M., and Peetsma, T. T. D. (2009). Effects of inclusion on students with and without special educational needs reviewed. Educ. Res. Rev. 4, 67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2009.02.002

Sadler, M. S., Meagor, E. L., and Kaye, K. E. (2012). Stereotypes of mental disorders differ in competence and warmth. Soc. Sci. Med. 74, 915–922. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.019

Saloviita, T., and Consegnati, S. (2019). Teacher attitudes in Italy after 40 years of inclusion. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 46, 465–479. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12286

Saloviita, T., and Schaffus, T. (2016). Teacher attitudes towards inclusive education in Finland and Brandenburg, Germany and the issue of extra work. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 31, 458–471. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2016.1194569

Sharma, U., and Sokal, L. (2016). Can teachers’ self-reported efficacy, concerns, and attitudes toward inclusion scores predict their actual inclusive classroom practices? Austr. J. Spec. Incl. Educ. 40, 21–38. doi: 10.1017/jse.2015.14

Takala, M., Haussttätter, R. S., Ahl, A., and Head, G. (2012). Inclusion seen by student teachers in special education: differences among Finnish, Norwegian and Swedish students. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 35, 305–325. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2011.654333

Tournaki, N., and Samuels, W. E. (2016). Do graduate teacher education programs change teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion and efficacy beliefs? Act. Teach. Educ. 38, 384–398. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2016.1226200

UNESCO (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Adopted by the World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Equity. Paris: UNESCO.

Urton, K., Wilbert, J., and Hennemann, T. (2014). Attitudes towards inclusion and self efficacy of principals and teachers. Learn. Disabil. Contemp. J. 12, 151–168.

Vaillancourt, M. (2017). L’accueil des étudiants en situation de handicap invisible à l’Université du Québec à Montréal: enjeux et défis [Accommodating students with invisible disabilities at the Universiteì du Queìbec aÌ Montreìal: issues and challenges]. La Nouvelle Revue de l’adaptation et de La Scolarisation 77, 37–54. doi: 10.3917/nras.077.0037

van Steen, T., and Wilson, C. (2020). Individual and cultural factors in teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion: a meta-analysis. Teach. Teach. Educ. 95:103127. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2020.103127

Vaz, S., Wilson, N., Falkmer, M., Sim, A., Scott, M., Cordier, R., et al. (2015). Factors associated with primary school teachers’ attitudes towards the inclusion of students with disabilities. PLoS One 10:e0137002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137002

Keywords: attitude, inclusive education, autism, teacher, special educational needs

Citation: Jury M, Perrin A-L, Rohmer O and Desombre C (2021) Attitudes Toward Inclusive Education: An Exploration of the Interaction Between Teachers’ Status and Students’ Type of Disability Within the French Context. Front. Educ. 6:655356. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.655356

Received: 18 January 2021; Accepted: 12 April 2021;

Published: 05 May 2021.

Edited by:

Brahm Norwich, University of Exeter, United KingdomReviewed by:

Elias Avramidis, University of Thessaly, GreeceCopyright © 2021 Jury, Perrin, Rohmer and Desombre. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mickaël Jury, bWlja2FlbC5qdXJ5QHVjYS5mcg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.