- 1International Gaming Research Unit, Psychology Department, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, United Kingdom

- 2Psychology Department, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, United Kingdom

Rising prevalence of mental disorders among children and adolescents in the United Kingdom has arguably been associated with increased levels of problematic smartphone use and social media use, rendering the need for health promotion at a school level. However, evidence on how teachers may best support media literacy and emotional wellbeing is lacking. The present study explored perceptions of adolescent online engagement and recommendations of how schools could prevent the experience of online harms during adolescence through qualitative interviews with teachers (N = 9, Mage = 39.2 years, SD = 7.74). Results were analysed using thematic analysis and provided the following themes in terms of recommendations for online harms: i) schools in transition and redefining expectations, ii) a modular approach to media and emotional literacy, iii) media and emotional literacy teacher training, and iv) encourage dialogue and foster psychosocial skills. Psychosocial skills were further analysed as critical components of perceived online harm prevention into the following categories: i) self-control and emotion regulation skills, ii) digital resilience and assertiveness skills, iii) social and emotional intelligence and metacognitive skills to encourage balanced use and emotional health. Findings corroborated the need for an increasing health promotion role of teachers and school counsellors and in the contribution of students’ cognitive and emotional development through skill acquisition. Implications are discussed for the role of educational settings in prevention of online harms, while preserving the significant benefits of digital media for education and social connection, and for the prompt identification and referral of problematic users to adolescent mental health services.

Introduction

Rising mental health disorder prevalence in children and adolescents in the UK (NHS Digital, 2018) has triggered a need to support children’s mental health and to expand the school’s role in identifying and supporting young people with resources and faster access to health services (Department of Health - Department of Education, 2017). School-based interventions for behaviour change are increasingly becoming a dynamic source for prevention of potential mental health disorders with mental health literacy as a key part of mental health promotion (Kutcher et al., 2016). Mental health literacy has been defined as a form of health literacy comprising four pillars: seeking and obtaining good mental health, understanding mental disorders and its treatment and help-seeking efficacy (Kutcher et al., 2016). Promoting mental health in schools has been found to render small to moderate effect sizes with large practical impacts and the most effective strategies being the ones employing teaching skills, positive mental health, a balance of universal and targeted approaches with an early start, and whole school approaches, amongst other factors (Weare and Nind, 2011). Education has been found to be a powerful determinant of adolescent health and interventions investing in adolescent well-being incur benefits for future adult life (Patton et al., 2016).

School-based prevention and mental health literacy (Throuvala et al., 2019; Throuvala et al., 2020) have been suggested as important ingredients in supporting students’ beneficial use of social media and embrace the positive outcomes in terms of learning and engagement (Stathopoulou et al., 2019) while reducing problematic screen time involvement and smartphone use (Subhash and Cudney, 2018; Rach and Lounis, 2021). In China, which has the highest number of smartphone users (Newzoo. Newzoo’s, 2020), various school policies on smartphone use have been implemented which differ on content, purpose and effectiveness. However, studies on the topic have revealed the complexity in handling smartphone use at school and highlight low effectiveness of smartphone use policies and similarity in teachers’ policy improvement recommendations across elementary, lower and upper school (Gao et al., 2014). However, increasing concerns regarding the wide impact that problematic internet use has on adolescents (Throuvala et al., 2021) has led to the development of policymaking (Koo and Kwon, 2014; Shek and Ma, 2014) and expert institutions have developed position papers and guidelines for screen time for young people (Picherot et al., 2018; American Psychological Association, 2019; World Health Organization, 2019; Dubicka and Theodosiou, 2020) while governments (i.e., United Kingdom) have made calls to clarify the evidence to guide policy choices (Griffiths et al., 2018). The present study therefore examines teacher recommendations for school-based prevention of online harms and perceptions of necessary skills that need to be developed within the context of prevention.

Social media and smartphone use incur benefits (e.g., enhancing social relationships), but have also been reported to be arguably implicated in a host of mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, suicidality, self-harm, negative self-perception, negative interactions, aggressive acts and exposure to harmful content (promoting self-harm or suicidality), in a dose-response relationship (Abi-Jaoude et al., 2020). However, despite evidence supporting that the more time spent online increases the possibility of exposure to risks and the development of problematic tendencies (e.g., cyberbullying) longitudinal evidence (Coyne et al., 2020) is still conflicting and highly debated (Przybylski and Weinstein, 2017; Twenge et al., 2018; Boers et al., 2019; Przybylski and Weinstein, 2019; Twenge et al., 2019; Coyne et al., 2020; Stockdale and Coyne, 2020; Twigg et al., 2020), with academic debates arguing the thresholds of normative and problematic behaviours (Bucksch et al., 2016; Boers et al., 2019; Hygen et al., 2020) and the choice of more appropriate methodological approaches in studies (Rumpf et al., 2019; Colder Carras et al., 2020; Orben, 2020).

In order to support school-based prevention of online harms and problematic uses, skill development and enhancement appears to be strongly recommended as a basic ingredient of interventions (Livingstone and Helsper, 2010; Clarke et al., 2015; Ansari et al., 2017; Rumpf et al., 2019), along with regulation, social support and other environmental changes (i.e., provision of public spaces) (Livingstone and Helsper, 2010; Clarke et al., 2015; Ansari et al., 2017). Life skills have been operationally defined “as psychosocial abilities for adaptive and positive behaviour that enable individuals to deal effectively with the demands and challenges of everyday life. They are loosely grouped into three broad categories of skills: cognitive skills for analysing and using information, personal skills for developing personal agency and managing oneself, and interpersonal skills for communicating and interacting effectively with others” (UNICEF, 2003). Such school-based learning has been supporting prevention efforts for bullying, drug abuse, competence enhancement by enhancing skills in emotional intelligence, problem solving and conflict resolution and social skills (Osher et al., 2016). However, skills are highly dependent on executive function and have cognitive and emotional components (i.e., self-regulation or attention which is a cognitive skill but influenced by learning competencies such as persistence), which are interdependent and difficult to categorize (Darling-Hammond et al., 2019). Cognitive skills such as problem-solving, responsible decision making, and perspective taking interact with emotional skills such as emotion recognition, empathy, and emotion regulation, and with social skills including cooperation, helping, and communication in supporting children’s developmental trajectory (Cantor et al., 2019). The development of skills is influenced by socializing agents (i.e., teachers, other adults), and, in turn, they develop into higher order skills across cognitive, emotional, and social domains (Darling-Hammond et al., 2019).

The development of individual interpersonal and intrapersonal skills in children and adolescents is a critical component of school curriculum for learning and development (Darling-Hammond et al., 2019), and in countries faced with high prevalence rates in internet addiction and gaming disorder (primarily South East Asian countries), skill development has been prioritized and embedded in school curricula as well as, in the design of longitudinal, large-scale, school-based, government-funded interventions (Shek et al., 2011). Efforts to instil an appropriate mix of skills to enhance individual resilience and emotional readiness to engage online appear to be complemented by efforts in the school environments and policies to detract from prolonged online engagement as a default choice and spend leisure and break time by promoting physical activity and healthy eating (Story et al., 2009; Vik et al., 2015). Rising numbers in childhood obesity and other non-communicable diseases, require coordinated and collective efforts of many different stakeholders across multiple settings (Amarasinghe and D’Souza, 2012) to promote more active lifestyles and reduce screen-time sedentary behaviours (Throuvala et al., 2020).

Research from more traditional prevention programmes, such as school-based substance use prevention, has shown that life skills programmes are effective with enhanced life skills protecting against alcohol and nicotine use (Bühler et al., 2008). These skills include competence enhancement (i.e., training in communication and interpersonal skills, critical and creative thinking, decision making and problem solving, self-awareness and empathy and coping with stress and emotions) and focusing on problem behaviour (information about substances, value clarification, norm education, etc.). It has been proposed that to address time related impacts from problematic content and addictive use, effective strategies following other primary prevention interventions include: i) a combination of parental media education skills for screen time reduction by limiting environmental access, ii) life skills training, and iii) media literacy training for older children - moving beyond only technical or use-oriented skills (Bleckmann and Mößle, 2014).

Additionally, given the increase in mental health problems in young people and the high comorbidity rates in gaming disorder with anxiety, depression and ADHD (Kuss and Griffiths, 2011; Kuss and Lopez-Fernandez, 2016; Kuss and Pontes, 2019), social skill deficits associated with specific disorders (i.e., ADHD) have been found to be associated with an increased risk for internet addiction, internet gaming and streaming (Chou et al., 2017). Lack of social and emotion regulation skills have been associated with internet gaming disorder (Wichstrøm et al., 2019; Fumero et al., 2020), internet addiction (Zegarra Zamalloa and Cuba Fuentes, 2017) and other mental health problems (Bühler et al., 2008; Clarke et al., 2015; Chou et al., 2017). The acquisition of such skills through school-based interventions has been associated with positive youth development, healthy lifestyle behaviours and reduction of poor mental health outcomes and behaviours (i.e., conduct disorders, violence, bullying, conflict) (Sancassiani et al., 2015). For example, South Korea’s efforts to prevent internet addiction has prioritized prevention education, which has become compulsory by law (Cho, 2016) with educational programmes available for primary, middle, upper school and university students. This involves self-diagnostic tools and self-monitoring records on internet and smartphone use and story narratives for younger children (pre-school and primary school children) as well as, e-learning components and guidebooks promoting self-control and action-planning. Therefore, adolescents are trained to exercise self-monitoring across time, to use self-assessment and to make a habit to control online behaviours. Parental guidance is encouraged for pre-school and first and second-grade school students (Cho, 2016).

Additionally, skill enhancement has been considered critical in treatment of gaming disorder (Torres-Rodríguez et al., 2017). Cognitive behavioural therapy approaches often used in the treatment and prevention of addictive behaviours employ executive function skills training, which involve decision-making, impulse control, perspective taking, and behavioural regulation, and appear to act as a protective factor against the development of addictions (Carr and Stewart, 2019). Therefore psychosocial skills are an important area where prevention of problematic internet use should focus on (Throuvala et al., 2019).Skill development and enhancement interventions are of particular relevance in adolescence due to being a critical period for developmental and neurophysiological changes in executive function and social cognition (Blakemore and Choudhury, 2006) where the highest gaming and social media use takes place (Anderson and Jiang, 2018), where online engagement and executive function processes interact (Allan et al., 2016). Communication and skill enhancement supports the developmental transitions of adolescence (Christie and Viner, 2005) and given the susceptibility to addictions (Balogh et al., 2013), training of various interpersonal and intrapersonal skills is considered fundamental to prevent the development or progression to addictions. For this purpose, skill training is embedded in current intervention approaches to prevention with competence enhancement focus (for universal, social and emotional skills interventions, mentoring and social action interventions) and interventions aimed at reducing problem behaviours (aggression and violence prevention, bullying prevention and substance misuse interventions) with partial evidence for effectiveness (Clarke et al., 2015).

With evidence amassing for risks for gaming disorder and problematic social media use among children and adolescents, it is timely to understand prevention priorities and skill development for media literacy education as conceptualised by secondary school teachers. Understanding priorities for prevention as defined by teachers could enhance school efforts of how best these issues could be addressed (Sohn et al., 2019). Therefore, to support schools in providing evidence-based and developmentally sensitive approaches, the present study examined United Kingdom school teachers’ views and perceptions about the nature of concerns and recommendations for online harm prevention in secondary schools in adolescence (Brennan, 2011; Sammons et al., 2014). The interviews were conducted to address the gap in the knowledge for media and emotional literacy recommendations for the prevention of online harms and the conceptualisation of the necessary skills required to develop through media and emotional literacy.

Methods

Design

The present study was analysed with thematic analysis and involved interviews with teachers from three different schools in the United Kingdom, which allowed participant accounts and experiences to emerge with the aim to gather in-depth information (Jamshed, 2014). Thematic analysis is amongst the most widely used methods to conduct a qualitative analysis (Howitt and Cramer, 2017) that provides a method of analysis rather than a methodology independent of epistemological or theoretical perspective (Nowell et al., 2017). The study followed Braun and Clarke’s (Braun and Clarke, 2006) six steps of thematic analysis, which comprise: i) familiarizing oneself with the data by transcribing, reviewing and annotating the data to reflect on initial ideas, ii) generating initial codes, iii) searching for broader level themes by sorting and grouping the codes, iv) reviewing themes by reorganising initial themes, v) defining and naming themes by capturing the essence of what each theme is about, and vi) producing the report with extracts embedded in an analytic narrative. This method of analysis allows for a reflexive approach, which acknowledges that themes do not passively emerge from the data; instead it is an active process of interpretation produced by the researcher reflecting and engaging with the analytical process (Braun et al., 2019). More specifically, data are analysed following a systematic process which leads to newly conceptualised findings (Bogdan and Biklen, 2007). Emphasis was placed primarily in teacher experience and concerns regarding adolescent online use and potential recommendations proposed to overcome challenges and perceived harms in adolescence, which could form media literacy initiatives and skill enhancement.

Participants

Participants (N = 9), aged 29–52 years (Mage = 39.2, SD = 7.74), were teachers in United Kingdom secondary education (Year 8–12) of three local schools in the East Midlands area of the United Kingdom, including a mix of an all-female school and two co-educational schools. Participants were primarily white (n = 7), black (n = 1) and Asian (n = 1), with a gender split (five females and four males) and from middle (n = 5), and lower (n = 4) socio-economic background. This study targeted teachers due to the: i) need to identify teacher perspectives and concerns regarding online adolescent problems, ii) lack of studies reflecting teacher views for prevention purposes (Dennen et al., 2020) iii) evidence of higher efficacy of intervention effects when teachers displayed greater teacher commitment (Orpinas and Horne, 2004), iv) growing need for school-based prevention strategies (Throuvala et al., 2019).

Procedure

The study’s protocol and relevant materials (i.e., discussion guide) was approved by the research team’s university Ethics Committee (No. 2017/109) and was part of a larger stakeholder study addressing concerns and recommendations for prevention of online harms. The study was suggested to the school administrators through initial emails and discussed in detail in face-to-face meetings. Subsequently, the schools communicated the study’s aims internally, recruited teachers on a voluntary basis and coordinated the timing of the interviews at school premises. The interviews were semi-structured, lasted approximately 60 min, and were audio-recorded and analysed verbatim with the use of the Nvivo 12 software. Various questions in the semi-structured interview guide were used to elicit teachers’ perceptions and views on issues faced by their adolescent students (e.g., “What impacts do you think screen time has on your students?”, “What would be the best way to address these concerns?”). Participants offered perceptions and views about prevention primarily in relation to social media use and gaming, and respective priorities for prevention. During the interviews, discussion organically reflected on core issues the teachers have encountered through their professional practice in relation to adolescents’ challenging experiences with the online environment. Teachers taught on a variety of subjects (i.e., biology, physical education [PE], personal, social, health, and economic [PSHE] education) providing a breadth of experiences through their roles. The data presented tapped into representative comments made through teacher reflections in the interviews. Data saturation was reached at the ninth interview as no new content emerged.

Data Analysis

Codes were developed by the first author and transcripts were also read and coded by another member of the research team to identify themes and ensure consistency and level of agreement. Reflexive memos and analytic notes were taken after interviews and were utilised during the transcribing phase. Reflections and analytic thoughts were also discussed with colleagues throughout the research process. Codes were developed and discussed with the rest of the members of the research group as coding developed (Maguire and Delahunt, 2017). This process was followed to ensure rigour and trustworthiness of data and assess the level of agreement (Armstrong et al., 1997; Nowell et al., 2017) despite this not being a necessary requirement in thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2018). Themes presented commonalities and in case of differential views these were discussed and consensus was reached, resulting in exclusion from the analysis or integration into one of the higher order themes. For example, in examining recommendations, following theme consolidation, a major theme, “encourage dialogue and foster psychosocial skills”, appeared to be a strong theme for media literacy recommendation. The coding system made reference to the participant number, the gender and age of the participant (i.e., IF3).

Results

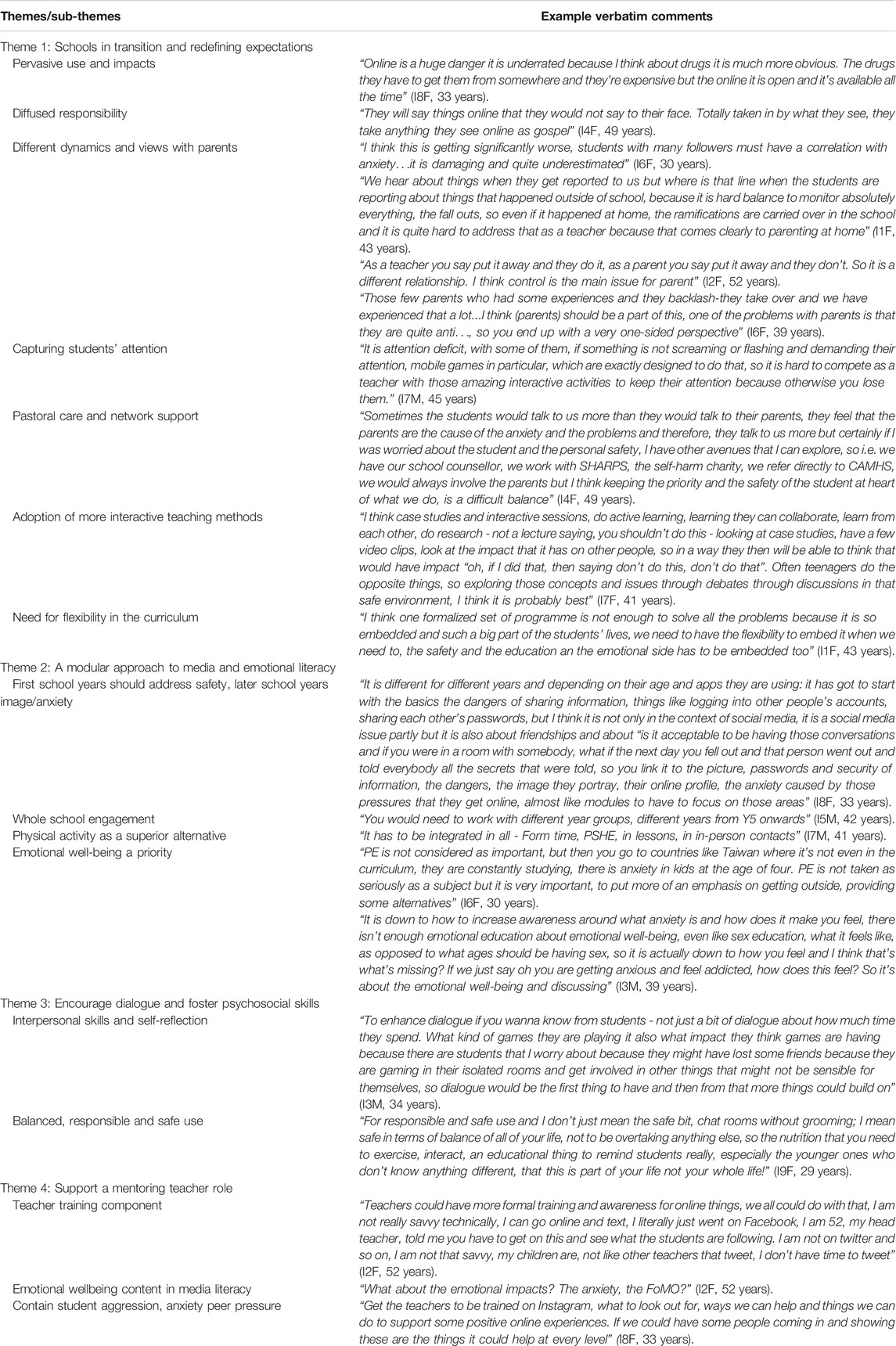

Teacher recommendations formed the following themes: i) schools in transition and redefining expectations, ii) a modular approach to media and emotional literacy, iii) media and emotional literacy teacher training, and iv) encourage dialogue and foster skills. Teacher perceptions acknowledged the need to embrace technologies and highlighted limit-setting to safeguard children and adolescents as a primary objective. Perceived benefits from online engagement were: i) platforms as a major and effective learning tool (for research purposes and use as a collaborative tool), ii) games offering positive outcomes (entertainment, brain training, use beneficial for introverted or autistic children), iii) social media forming major part of daily communications for friendship maintenance and acquisition and communication, and iv) the acquisition of important skills for future professional life. However, teachers perceived that negative views of technology overshadowed the positives and expressed concerns regarding a greater use of social platforms by students for entertainment purposes rather than learning:

“[Students] have lost sight that they can use it for learning purposes, and not just for fun, there is educational videos, information that they take for their lessons, so if there was a programme to bolster that area, that would be useful” (I3Μ, 34 years).

Teachers also acknowledged that recreational digital use is a massive part of school life with students being in constant sync with each other and with exposure starting from a very young age presenting with challenges. Perceptions of devices and online use to regulate emotions were also expressed (see Table 1) and viewed online communities as an “echo-chamber of emotions” (I6F, 30 years) triggering anxiety and emotional problems but also positive benefits, suggesting a spectrum of positives and negative influences. The following themes in terms of perceptions and recommendations emerged from the teacher accounts to support media literacy and emotional wellbeing.

Theme 1: Schools in Transition and Redefining Expectations

The first theme related to the perception of the transition within schools to embrace technologies and adopt digital learning while engaging in media and emotional literacy to minimize challenges. The first theme related also to ways the online activities pushed for new expectations of the school experience and revolved around new classroom and lesson experience. Teachers experienced a greater pressure to provide more entertaining content to emulate social media’s fast pace and impressive presentation of content. This placed a great degree of pressure on teachers who felt they were losing their pupils’ attention if they did not manage to provide this recreational dimension. As a result of this and the proliferation of media use and online delivery for teaching purposes, it was discussed that schools are in a digital transformation phase and consequences should be addressed (i.e., diffused boundaries between online learning and recreational use). Additionally, teachers raised an issue of students’ expectations to generate more engaging teaching experiences and school lessons, mediated by their extensive exposure to speedy and entertaining social media content. Teachers reported that current strategies for the delivery of Physical, Social and Health Education (PSHE) required updating: i) PSHE was currently geared towards topics about safety - with no emphasis on psycho-education content, ii) suggested that media literacy in school settings should be given equal priority to drugs if not more due to the pervasive nature and the degree of online engagement, and iii) establish rules in relation to smartphone use during school hours, iv) prevention could be provided in an interactive, engaging way:

“I think case studies and interactive sessions, I think it is the same with teaching, do active learning, learning they can collaborate, learn from each other, do research–not a lecture saying, you shouldn’t do this–looking at case studies, have a few video clips, look at the impact that it has on other people, so in a way they then will be able to think that would have an impact. Often teenagers do the opposite things, so exploring those concepts and issues through debates and discussions in that safe environment, I think it is probably best” (I2F, 52 years).

Smartphone use for recreational purposes emerged as a key use presenting with challenges, where stricter rules were required during school hours and a higher degree of compliance with school rules. This was viewed as being reinforced due to lack of clear boundaries set by parents, who were viewed by teachers as being ambivalent and partially ignorant of their children’s specific uses. This was coupled with a tendency to diffuse responsibility in relation to supporting adolescent challenges and harms due to lack of parental knowledge and being technophobic and controlling or encouraging use as a reward. Parents were viewed by Teachers as polarized and partially unaware of the extent of use or the emotional problems experienced by their adolescent children. Teachers discussed parental expectations of schools to handle the challenges faced by their children and perceived students to be more trusting towards their teachers than their parents. However, teachers, perceived themselves as being able to enforce rule-setting more than parents due to their professional role.

Teachers discussed persuasive design and structural mechanisms within social media and games driving higher engagement and exposure to aggressive operators’ marketing initiatives online, as interfering and defining students’ values and motivations and posing a further digital divide with low socioeconomic students in the use of expensive devices. Children and adolescents were perceived as not being in a position to critically evaluate the commercial messages, which influenced student choices while compromising their agency and self-regulation. Teachers acknowledged the need for consistent rule setting of smartphone use in schools. Additionally, online issues which involved students with emotional difficulties appeared to be significantly more complex to be handled and in relation to balancing the relationships with parents, such as the below incident with a student mentioned by one of the teachers:

“I think the parents are aware that she doesn’t find school appealing and they know she spends time online, and because she also faces emotional difficulties, they don’t realize the severity of that and my difficulty is the balance of gaining her trust and also managing the parents as well. So I think they are aware to a certain extent but perhaps not to the same extent because she is very open with me” (I1F, 43 years).

Parents were also viewed as needing support regarding their communication with their children in relation to online engagement, harmful content and effects (i.e., pornography exposure) via parental seminars.

Theme 2: A Modular Approach to Media and Emotional Literacy

The second theme referred to the need to adopt a stepwise developmental approach to media and emotional literacy in schools, prioritizing Years 7-8-9 for groundwork to serve as a gateway for Years 10-11-12 where the majority of the issues arise. Teachers proposed for the early school years to address safety issues and later school years to address psycho-emotional issues, such as image and anxiety-related issues arising from social media use. To support more positive online experiences and mental health literacy within schools a new pastoral and educational role was envisaged to relating to negative impacts or harms of digital engagement.

“Actually it is affecting many students, whereas the drugs and things affects a minority, so I think in terms of the self-esteem, the wellbeing, the emotional health, I see it as a huge part of what we are doing and I think spending time on it is really important” (I6F, 30 years).

This was viewed as needing a more holistic approach (i.e., to encompass also physical activity and encourage balanced nutrition). Methods of delivery for media literacy were proposed as being interactive rather than didactic, involving discussion, reflective approaches and sharing of personal real-life experiences from use of personal devices and problems experienced online:

“I think it is different for different years and depending on their age and apps they are using, and then I think it has got to start with the basics the dangers of sharing information, things like logging into other people’s accounts, sharing each other’s passwords, but I think it is not only in the context of social media or Whatsapp, that is a social media issue partly but it is also about friendships and about “Is it acceptable to be having those conversations and if you were in a room with somebody, what if the next day you fell out and that person went out and told everybody all the secrets that were told?,” so you link it to the picture, passwords and security of information, the dangers, the image they portray, their online profile, the anxiety caused by those pressures that they get online…Almost like modules to have to focus on those areas” (I7M, 41 years).

Additionally, app-delivered objective monitoring was recommended to provide students with insight regarding the extent and the duration of use as well as, the content that has been accessed. Such information was viewed as potentially encouraging discussion and openness to bring forward issues that were of priority and relevance to the students:

“It is important to have a realization of where I am at with my social media, this is how many hours they are using, this is how much sleep I am getting, how it is making me feel. Actually we are working on the “positivity project,” which works like a “barometer” actually saying ‘you know it is ok to feel down sometimes as long as you can then come back up from that’ and then equipping the girls with the skills to get back on and you could almost combine it with that as well, “How am I feeling and is it the social media that is making me feel like that and therefore what do I do about it? Does deleting social media lead to a better quality of life? Have you heard of project Reconnect? We have put that in the Year 8 tutor programme, we haven’t really launched it properly yet, and whether does switching off help my emotional wellbeing? So anything like that would be very interesting” (I1F, 43 years).

Therefore, another strategy that teachers proposed was to assess the impact of short-term abstinence periods that would potentially encourage a different outlook of digital use, the degree of dependence on devices and the balance between time spent online and offline. Ultimately, it was viewed that adolescents would be able to come to the realization that they could cope with less use of devices. Overall, teachers expressed a pressing need to balance evidence for positive uses to negative ones and relating to awareness of long-term impacts of online challenges and harms. Therefore, embracing technological change and engaging in digital literacy and emotional wellbeing topics was viewed as a priority to attend to learning outcomes and students’ daily reality:

“It is a massive priority, more of a priority than some of the things they are learning in PSHE, we go on and on about sexting, don’t do this, don’t do that, make sure you have the privacy settings, but we don’t sort of address things appropriately” (I2F, 52 years).

Theme 3: Media and Emotional Literacy Teacher Training

The third theme involved the challenging transition to an increasing pastoral role of teachers towards pupils to support more positive student online experiences while attending and providing support to the parent community. Teachers expressed concerns with issues in terms of what they wanted their students to access and what was age appropriate. Providing audio-visual methods to help with student understanding and engagement was deemed useful when discussing internet related topics. Specialized teacher training for school teachers was emphasized to support the tutor role in promoting emotional well-being beyond online safety. More specifically, a teacher training component on helping students deal with aggressive acts online and on training physical education teachers to facilitate body confidence messages along with parent training to enhance support for adolescent-parent communication for online issues and extend dialogue beyond time spent online.

“We try and help support the parents through that, with the parental seminars we are organizing, and safety talks. It is finding the balance with supporting them with the knowledge we have as a school and then on a more personal basis with the individual” (I4F, 49 years).

Additionally, teacher training was viewed as useful in detecting students who display problematic internet use or present with signs which may signal an alert for at risk students. According to teachers, gamers or students spending too much time gaming were easily spotted as they were usually sleep-deprived due to gaming until late hours. Further to an initial teacher training component, teachers suggested to be undergoing regular training adapting to the technological advances and affordances as well as, changes in popularity and preference of online platforms and services.

Theme 4: Encourage Dialogue and Foster Skills

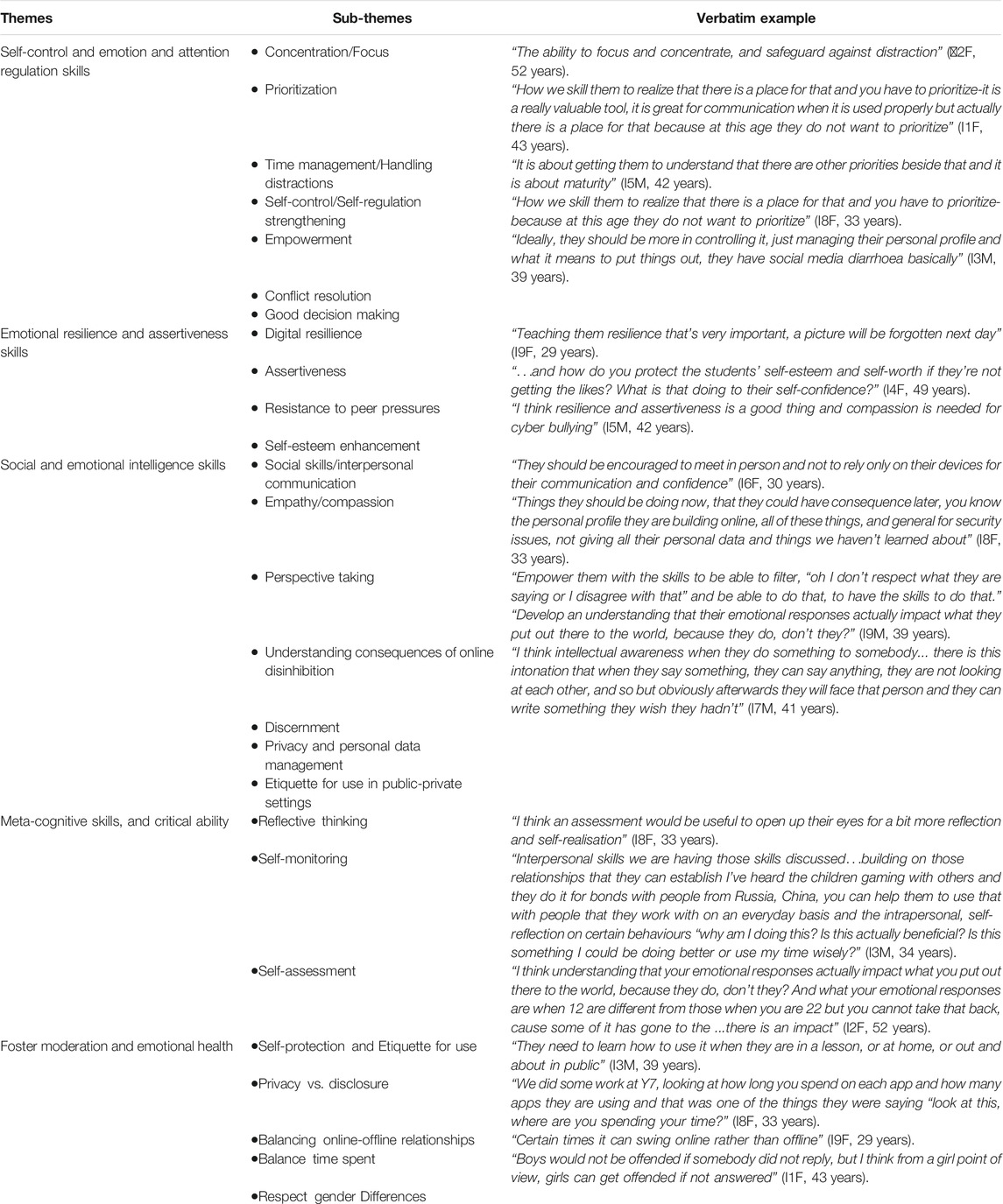

The fourth theme pertained to applying discursive approaches to emotional wellbeing and skill development rather than focusing merely on safety. Skill development was the strategy proposed as the most appropriate for adolescents to maximize opportunities and cope with screen time challenges. In order for these skills to be developed it was suggested that reflection and discourse would potentially elicit responses on a host of important topics such as students’ body image. Discursive approaches were viewed as critical to be included in formal education where students would benefit from engaging in discussion about their experiences online extending it beyond time spent and applying critical evaluation. Teachers expressed a need to endorse mental and physical health balance pertaining to emotional wellbeing – driven by awareness, self-reflection and acceptance of negative emotions; reinforcement of positive emotions and mind-set; exercising perspective taking, empathy, resisting peer pressure and encouraging metacognition about own and others’ emotional responses; control and self-regulation—by educating about value of long-term gratification vs. short-term rewards; discernment–reinforcing balance and positive use but also priorities; and iv) time management and time perception enhancement. The following skill development areas were therefore proposed to be developed within media literacy to serve as protective factors (Table 2): i) control and emotion regulation skills, ii) digital resilience and assertiveness skills, iii) social and emotional intelligence and metacognitive skills to encourage balance and emotional health.

Self-Control and Emotion Regulation Skills

The development of skills of self-control and self-regulation, as well as regulation of attention and handling distractions, managing time, were characterized as critical by teachers for empowering children and instilling an ability to control their online behaviours. Being able to concentrate on primary tasks, in class and in homework, and prioritize daily activities in relation to recreational online use was considered a key skill to practice. These skills defined choice of time spent online. Lack of self-control and self-regulation was viewed as impacting later adulthood and professional experiences by interfering with work priorities and inability to concentrate and produce deep work. Constant exposure to quick rewards and the multi-tasking and inability to immerse themselves in a single task for sustained periods was perceived as lowering the threshold of tolerance for single tasking for longer-term gains. Prevention for online harms was considered of higher importance to drugs and alcohol due to their pervasive, wide-reaching nature and persuasive design. Concerns were expressed for the social validation feedback loop—the impact of mechanisms such as likes and the acquisition of followers were viewed as a vulnerability in human psychology reducing self-control and self-regulation.

Digital Resilience and Assertiveness Skills

A second set of skills emphasized by teachers was related to resilience and the ability to be confident online or having a reasoned refusal in a situation or the resilience to de-escalate negative online communication was emphasised as a key skill:

“All of those things, not being swayed by peer pressure, resilience, things not only with the social media use but also to help them to develop across the board are recipe for success” (I4F, 49 years).

Skills for safeguarding privacy and the ability to protect their personal data was also related to issues of sexting. Additionally, teachers expressed the sharing of personal experiences could lead to active learning and assertiveness:

“I think it is already an issue and we address it from as early as Year 7 and we had discussions: how would you like it if someone would do that to you?... let’s put you in that person’s position. If you say something online and it is not very kind, how would you feel if that person said it to you? ... We had a situation where we sent out letters to parents along those lines and explained that we had got some issues, because there were girls that were really upset about things that were happening to them” (I2F, 52 years)

Social and Emotional Intelligence and Metacognitive Skills

Teachers emphasised the need for adolescents to exhibit empathy, understand and reflect on the consequences of interpersonal communication and the display of aggression or of online disinhibition by encouraging discernment in communication. Additionally, the use of self-reflection on commercial interests, or understanding of operators’ hooks and use of persuasive design or on time invested in online activities could be helpful to change attitudes. Learning “how to” self-protect and being able to draw a distinction between private use and when in a social situation or surrounded by other people was another skill emphasised as was the need to appreciate the value of face-to-face interpersonal communication rather than just the digital was another skill area proposed. Encouraging metacognition - thinking about their own behaviour - and the impact their behaviour may be having on others was viewed as necessary by monitoring and reflecting on the behaviours and the consequences.

Discussion

Schools in recent years are trying to leverage positive outcomes from online engagement for students while reducing negative influences (Subrahmanyam and Greenfield, 2008). The current study examined teacher perceptions of adolescent online uses and recommendations and relevant skills to alleviating concerns and minimise negative impacts while maximizing positive uses. Main themes regarding teacher perceptions pertained to: i) schools being in transition and redefining expectations, ii) a modular approach to digital literacy, iii) encourage dialogue and foster skills, and v) support a mentoring teacher role. Findings therefore suggested an increasing need for evidence-based training of professionals and education providers to support training needs in children’s digital education and mental health promotion, confirming previous evidence (Blum-Ross and Livingstone, 2016).

The first theme formed the perception of schools as being in a digital transition process with students facing new online challenges and harms and a need for a redefinition of the school experience and culture to facilitate the provision of digital and mental health literacy. Schools were viewed as needing to embrace mental health literacy topics requiring an expanding tutor and school role as prevention hubs. Challenges and harms in relation to adolescent digital use were conceptualized by teachers beyond online safety, with cognitive, emotional and behavioural dimensions, encompassing mental health correlates. These impacts were viewed as needing to be addressed in media and mental health literacy (Kutcher et al., 2016) in line with recent policy changes in the United Kingdom supporting mental wellbeing in schools (Department for Education, 2020). Teacher perceptions expressed suggested that a supportive school environment with the collaboration of external mental health services were the pathways to primary prevention (Throuvala et al., 2019; Throuvala et al., 2020).

Teachers suggested instead of ad-hoc/one-off interventions a more comprehensive media literacy programme embedded in the school curriculum. Skill development such as resilience, self-control enhancement and self-regulation (i.e., time management) were recommended to be part of the curriculum provision in line with findings from GD prevention and treatment (Antons et al., 2020). Given that brief interventions present with mixed effects compared to assessment-only controls (Carney et al., 2016), the strong habitual nature of online uses and the environmental context that provides constant attraction and reinforcement for engagement, which potentially weaken the effects of such intervention initiatives, embedding a modular emotional literacy curriculum in schools across years from primary to secondary education could be more promising. Therefore, a more longitudinal and systematic framework was suggested by teachers, reflecting principles of the “whole school” approach. Whole school approaches engage except from students, their parents, teaching staff and the wider community (Mentally Healthy schools, 2018) and have provided initial positive results in Europe and in East Asian countries where such approaches have been implemented and evaluated (Shek et al., 2011; Busch et al., 2013; Busch, 2014).

In the United Kingdom, and despite the scarcity of educational resources, initiatives have been implemented in this direction: a mandatory digital citizenship programme for all schools in the UK for ages 4–14 years has been recommended by the UK Children’s Commissioner (The Children’s Commissioner’s Growing Up Digital Taskforce, 2017), calls for evidence and recommendations (Griffiths et al., 2018) and mental health provision through the Teaching and Leadership Innovation Fund to support training for the delivery of whole school approaches (Department of Health - Department of Education, 2017). Since September 2020, Relationships and Sex Education (RSE), along with health education, became compulsory in all schools providing a new curriculum in secondary education across the United Kingdom, including independent schools (fee paying private schools), in response to urgent calls for media literacy and prevention of online harms, going beyond safety and security topics to cover issues relevant to adolescent mental health and wellbeing (Department for Education, 2020). Such initiatives can raise awareness for adverse online experiences and help adopt strategies to cope with challenges.

First, accounts analysed the strategies which would support the development and maintenance of these skills and would effect change at a school level using a step-wise approach: i) a basic awareness raising, ii) attitude changing by developing an understanding and reflecting on negative impacts experienced from misuse or excessive use of online activities, and iii) behaviour changing by skill development. In terms of intervention methods which should be utilized, parental views endorsed awareness-raising, reflective and discursive methods, utilizing real life examples from adolescents’ personal experiences with prior documented benefits in learning (Boyd and Fales, 1983; Kolb, 1984; Uljens and Ylimaki, 2015), rather than use of didactic/instructional or authoritative methods. Additional methods, encouraging attitude and behaviour change, such as self-monitoring and periods of brief abstinence from use were proposed with emergent empirical evidence confirming the utility of those methods (Gainsbury, 2014; Auer and Griffiths, 2015; Harris and Griffiths, 2017; Kanjo et al., 2017; Bakker and Rickard, 2018; Turel et al., 2018). It has been suggested that information, literacy education and training can play an additional role in risk reduction by alerting social media users to the risks of compulsive use and helping them to develop self-management strategies (Klobas et al., 2018).

School teachers also recommended skill development to strengthen adolescent responses against problematic smartphone use and problematic mental health challenges confirming evidence supporting skills to serve as protective factors in interventions and school contexts, including digital literacy (Walther et al., 2014; Shek and Ma, 2016; Vondráčková and Gabrhelík, 2016; Yeun and Han, 2016; Throuvala et al., 2019) and for well-being (Casas et al., 2013). Four key categories of skills were proposed as essential to empower young people and instil an ability to control their online behaviours: i) control and emotion regulation, ii) digital resilience and assertiveness, iii) social and emotional intelligence and metacognitive skills. Evidence suggests that activating traits like cognitive or affective empathy enhance willingness to assist in preventing cyberbullying (Barlińska et al., 2018) or the recognition, reasoning and processing of emotion-related information of emotion in the context of problem-solving ability (Mayer and Geher, 1996) may help to communicate constructively online and prepare young people for the demands of adult professional life. Interventions investing in the relationship of child-teacher have also demonstrated a greater understanding and reflection on own ability to perceive, understand, and generate emotions (Opiola et al., 2020). Time and distraction management have been associated with social media and smartphone use (Ophir et al., 2009; Koo and Kwon, 2014; Thornton et al., 2014; Stothart et al., 2015; Gazzaley and Rosen, 2016; Duke and Montag, 2017; Felisoni and Godoi, 2018; Lin et al., 2018). Evidence also suggests that emotion regulation has a key role in the addictive process (Marchica et al., 2019). It has been proposed that capacity for self-regulation can be optimized with the help of teachers, parents, peers and significant others (Zimmerman, 2000).

Resilience and assertiveness skills have been found to be protective factors for internet addiction and risk behaviours (Stevenson and Zimmerman, 2005; Koo and Kwon, 2014; Lin et al., 2018; Robertson et al., 2018). Given the rise in psychopathology (Twenge et al., 2010), the skills proposed by teachers to be developed to guard against excessive use appear to be part of an overall life skillset and the new vision for education, which is fostering social and emotional learning through technology (World Economic Forum, 2016). The aforementioned skills have been also proposed to be included in a life skills curriculum in schools for the reduction of mental illness supported by evidence-based methods of explicit teaching of life skills–to be taught officially as mathematics and literature (Layard and Hagell, 2015). Cognitive skills related to executive function, such as decision-making, involving impulse control, future thinking, and behavioural regulation are considered a critical part in addiction prevention and findings that a 7 week cognitive skills intervention was successful in increasing behavioural inhibition (Carr and Stewart, 2019).

Lack of social and emotional intelligence skills (i.e., discernment, empathy) such as the display of low empathy has been associated with cyberbullying perpetration, video games and problematic online behaviours (Lemmens et al., 2006; Schultze-Krumbholz and Scheithauer, 2013; Kircaburun et al., 2018; Zych et al., 2018). Emotional intelligence has been found to be critical in the identification of emotion and emotion problem solving (Mayer and Geher, 1996). Fostering social and communication skills have been also trialled in “self-discovery” therapeutic camps for GD (Sakuma et al., 2017). Additionally, discernment was discussed by parents as a key skill to be exercised given the role of design elements in games or social media celebrity advertising. Studies report that the specific architecture of YouTube seems to encourage the development of celebrity figures through para-social relationships, which reinforces further online activity (de Bérail et al., 2019).

Meta-cognitive skills and fostering moderation were finally suggested to provide reflection on behaviours and appraisal of actions through monitoring online engagement. Meta-cognitive awareness involves a higher order thinking process about one’s own reflective ability, which involves a process of self-assessment and evaluation of progress towards a goal (Pantiwati, 2013). Metacognition is being primarily developed in adolescence and is of particular importance in decision-making, associated with self-regulation and control skills (Weil et al., 2013) and has been implicated in maladaptive coping strategies (Marino et al., 2018). Recent evidence has examined the role of metacognition in addictive behaviours and in problematic internet use (Spada et al., 2008; Spada et al., 2015) and therefore developing such skills and the capacity for reflective thinking, self-monitoring, self-assessment and reframing could be a valuable target in interventions for endorsing and maintaining a balanced online engagement in adolescence, since this is the period where the emergence of self-concept and self-awareness is developing. Finally, fostering moderation in terms of time spent, between online at the cost of offline involvement driven by FoMO (Gugushvili et al., 2020), context-appropriate choices, etiquette of use in public vs. private places and ability to self-protect from not exposing content which may place an adolescent in a disadvantage (i.e., sext-sharing), appeared to be critical parameters in endorsing mindful adolescent online experiences.

In order to enable teachers and staff to transition to a mentoring role and support emotional literacy, knowledge of the online environment and teacher training are a necessary condition, consistent with previous literature (Dennen et al., 2020). Educational/counselling psychologists or other mental health professionals could be trained to deliver support to teaching staff about online issues by enabling collaboration with local mental health charities (Bowskil, 2017) and help detect need for intervention with at-risk students (Döring, 2014; Lo et al., 2018), similarly to supporting other mental health disorders (Yager and O’;Dea, 2005). Digital technologies could also assist to augment intrapersonal (i.e., resilience, self-control) and interpersonal skills (i.e., empathy, perspective taking) through feedback, social and game-based learning, amplified by teacher guidance (McNaughton et al., 2018 Nov).

Overall, findings supported positives in social media uses for education but need to address online challenges and harms in recreational use and provided recommendations in supporting adolescents. Teachers’ perceptions are currently underrepresented in research and the present study is the first study to solicit teacher views on harms and recommendations for their amelioration from a qualitative perspective contributing to a scant literature on harm reduction. As a qualitative study, the current findings are based on a small number of teachers who provided rich data on their school experiences and their perspectives on strengthening adolescents. However, the results are not generalizable given that the sample was a small group of self-selected teachers from three different schools in one geographic area in the UK and so their views are not necessarily representative. Future quantitative research could follow up and confirm the validity of these views as well as investigate school teachers’ management of harms across the various school years. Findings provided recommendations which can help guide teacher training courses and school online harms prevention curricula enhancing student safeguarding and emotional wellbeing.

Conclusion

The current study findings highlighted recommendations for online harms prevention in schools. Skill development and training in the digital environment was highlighted amongst parents/carers as a major component in media education and highlighted specific skill sets to be developed for prevention of risky online behaviours. Teachers emphasized primary prevention and universal measures in trying to minimize psycho-emotional difficulties amplified by the online environment and possibilities of risky behaviours (i.e., gaming disorder, cyberbullying prevention). Findings corroborated the need for an increasing health promotion role of teachers and counsellors and contribution in students’ cognitive and emotional development and identified areas for media and emotional literacy in the form of recommendations.

Implications are discussed for the role of educational settings in leveraging positive online experiences and for the prevention of online harms and the prompt identification and referral of problematic users to adolescent mental health services, while preserving the significant benefits of digital media for education and social connection. Policy should consider the inclusion of a modular approach to media and health literacy and the development or enhancement of control and emotion regulation, digital resilience and assertiveness, social and emotional intelligence and metacognitive skills in intervention strategies digital education curricula.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Nottingham Trent University Business, Law and Social Sciences Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

MT: Principal investigator and main author. MT: Study design, data collection, data analysis. MG, MR, and DK: Supporting the study design, analysis and supervision of the study. MG, MR, and DK: Editing the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Abi-Jaoude, E., Naylor, K. T., and Pignatiello, A. (2020). Smartphones, Social media Use and Youth Mental Health. CMAJ 192 (6), E136–E141. doi:10.1503/cmaj.190434

Allan, J. L., McMinn, D., and Daly, M. (2016). A Bidirectional Relationship between Executive Function and Health Behavior: Evidence, Implications, and Future Directions. Front. Neurosci. 10, 386. doi:10.3389/fnins.2016.00386

Amarasinghe, A., and D'Souza, G. (2012). Individual, Social, Economic, and Environmental Model: A Paradigm Shift for Obesity Prevention. ISRN Public Health 2012, 1–10. doi:10.5402/2012/571803

American Psychological Association (2019). Digital Guidelines: Promoting Healthy Technology Use for Children. American Psychological Association.

Ansari, H., Mohammadpoorasl, A., Shahedifar, N., Sahebihagh, M. H., Fakhari, A., and Hajizadeh, M. (2017). Internet Addiction and Interpersonal Communication Skills Among High School Students in Tabriz, Iran. Iran J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 11 (2), e4778. doi:10.5812/ijpbs.4778

Antons, S., Müller, S. M., Liebherr, M., and Brand, M. (2020). Gaming Disorder: How to Translate Behavioral Neuroscience into Public Health Advances. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Rep. 7, 267–277.

Armstrong, D., Gosling, A., Weinman, J., and Marteau, T. (1997). The Place of Inter-rater Reliability in Qualitative Research: An Empirical Study. Sociology 31 (3), 597–606. doi:10.1177/0038038597031003015

Auer, M. M., and Griffiths, M. D. (2015). The Use of Personalized Behavioral Feedback for Online Gamblers: An Empirical Study. Front. Psychol. 6, 1406. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01406

Bakker, D., and Rickard, N. (2018). Engagement in mobile Phone App for Self-Monitoring of Emotional Wellbeing Predicts Changes in Mental Health: MoodPrism. J. Affective Disord. 227, 432–442. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.016

Balogh, K. N., Mayes, L. C., and Potenza, M. N. (2013). Risk-taking and Decision-Making in Youth: Relationships to Addiction Vulnerability. J. Behav. Addict. 2 (1), 1–9. doi:10.1556/jba.2.2013.1.1

Barlińska, J., Szuster, A., and Winiewski, M. (2018). Cyberbullying Among Adolescent Bystanders: Role of Affective versus Cognitive Empathy in Increasing Prosocial Cyberbystander Behavior. Front. Psychol. 9, 799. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00799

Blakemore, S.-J., and Choudhury, S. (2006). Development of the Adolescent Brain: Implications for Executive Function and Social Cognition. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiat 47 (3–4), 296–312. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01611.x

Bleckmann, P., and Mößle, T. (2014). Position zu Problemdimensionen und Präventionsstrategien der Bildschirmnutzung. Sucht 60 (4), 235–247. doi:10.1024/0939-5911.a000313

Blum-Ross, A., and Livingstone, S. (2016). Families and Screen Time: Current Advice and Emerging Research. London, UK: London School of Economics and Political Science.

Boers, E., Afzali, M. H., Newton, N., and Conrod, P. (2019). Association of Screen Time and Depression in Adolescence. JAMA Pediatr. 173 (9), 853–859. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1759

Bogdan, R., and Biklen, S. K. (2007). “Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theories and Methods,” in Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theories and Methods. Fifth edition (London, UK: Pearson).

Bowskill, Τ. (2017). How Educational Professionals Can Improve the Outcomes for Transgender Children and Young People. Educ. Child Psychol. 34 (3), 96–108.

Boyd, E. M., and Fales, A. W. (1983). Reflective Learning. J. Humanistic Psychol. 23 (2), 99–117. doi:10.1177/0022167883232011

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2018). Questions about Thematic Analysis. Available at: https://www.psych.auckland.ac.nz/en/about/our-research/research-groups/thematic-analysis/frequently-asked-questions-8.html#c83c77d6d1c625135085e489bd66e765

Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., and Terry, G. (2019). “Thematic Analysis,” in Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences [Internet]. Editor P. Liamputtong (Singapore: Springer), 843–860. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_103

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3 (2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brennan, C. (2011). You Got Pwned! the Behaviour of Young People Online and the Issues Raised for Teachers. Res. secondary Teach. Educ. 1 (1), 16–20. doi:10.15123/uel.860yv

Bucksch, J., Sigmundova, D., Hamrik, Z., Troped, P. J., Melkevik, O., Ahluwalia, N., et al. (2016). International Trends in Adolescent Screen-Time Behaviors from 2002 to 2010. J. Adolesc. Health 58 (4), 417–425. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.11.014

Bühler, A., Schröder, E., and Silbereisen, R. K. (2008). The Role of Life Skills Promotion in Substance Abuse Prevention: A Mediation Analysis. Health Educ. Res. 23 (4), 621–632. doi:10.1093/her/cym039

Busch, V. (2014). The Utrecht Healthy School Project: Connecting Adolescent Health Behavior, Academic Achievement and Health Promoting Schools. Utrecht, Netherlands: Utrecht University.

Busch, V., De Leeuw, R. J. J., and Schrijvers, A. J. P. (2013). Results of a Multibehavioral Health-Promoting School Pilot Intervention in a Dutch Secondary School. J. Adolesc. Health 52 (4), 400–406. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.008

Cantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L., and Rose, T. (2019). Malleability, Plasticity, and Individuality: How Children Learn and Develop in Context1. Appl. Dev. Sci. 23 (4), 307–337. doi:10.1080/10888691.2017.1398649

Carney, T., Myers, B. J., Louw, J., and Okwundu, C. I. (2016). Brief School-Based Interventions and Behavioural Outcomes for Substance-Using Adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016 (1), CD008969. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008969.pub3

Carr, K. L., and Stewart, M. W. (2019). Effectiveness of School-Based Health center Delivery of a Cognitive Skills Building Intervention in Young, Rural Adolescents: Potential Applications for Addiction and Mood. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 47, 23–29. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2019.04.013

Casas, F., Bello, A., González, M., and Aligué, M. (2013). Children's Subjective Well-Being Measured Using a Composite Index: What Impacts Spanish First-Year Secondary Education Students' Subjective Well-Being? Child. Ind. Res. 6 (3), 433–460. doi:10.1007/s12187-013-9182-x

Cho, C. (2016). “South Korea’s Efforts to Prevent Internet Addiction,” in The Cambridge Handbook of International Prevention Science (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press), 551–573.

Chou, W.-J., Huang, M.-F., Chang, Y.-P., Chen, Y.-M., Hu, H.-F., and Yen, C.-F. (2017). Social Skills Deficits and Their Association with Internet Addiction and Activities in Adolescents with Attention-Deficit/hyperactivity Disorder. J. Behav. Addict. 6 (1), 42–50. doi:10.1556/2006.6.2017.005

Christie, D., and Viner, R. (2005). Adolescent Development. BMJ 330 (7486), 301–304. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7486.301

Clarke, A. M., Morreale, S., Field, C-A., Hussein, Y., and Barry, M. M. (2015). What Works in Enhancing Social and Emotional Skills Development during Childhood and Adolescence? A Review of the Evidence on the Effectiveness of School-Based and Out-Of-School Programmes in the UK [Internet]. Galway: World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Health Promotion Research, National University of Ireland GalwayAvailable at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/411492/What_works_in_enhancing_social_and_emotional_skills_development_during_childhood_and_adolescence.pdf.

Colder Carras, M., Shi, J., Hard, G., and Saldanha, I. J. (2020). “Evaluating the Quality of Evidence for Gaming Disorder: A Summary of Systematic Reviews of Associations between Gaming Disorder and Depression or Anxiety,” in PLoS ONE. Editor F. Naudet, 15, e0240032. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0240032

Coyne, S. M., Rogers, A. A., Zurcher, J. D., Stockdale, L., and Booth, M. (2020). Does Time Spent Using Social media Impact Mental Health?: An Eight Year Longitudinal Study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 104, 106160. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2019.106160

Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., and Osher, D. (2019). Implications for Educational Practice of the Science of Learning and Development. Appl. Dev. Sci. 24, 1–44. doi:10.1080/10888691.2018.1537791

de Bérail, P., Guillon, M., and Bungener, C. (2019). The Relations between YouTube Addiction, Social Anxiety and Parasocial Relationships with YouTubers: A Moderated-Mediation Model Based on a Cognitive-Behavioral Framework. Comput. Hum. Behav. 99, 190–204. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.007

Dennen, V. P., Choi, H., and Word, K. (2020). Social media, Teenagers, and the School Context: A Scoping Review of Research in Education and Related fields. Education Tech Res. Dev 68, 1635–1658. doi:10.1007/s11423-020-09796-z

Department for Education (2020). Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) (Secondary). London: GOV.UKAvailable at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/relationships-education-relationships-and-sex-education-rse-and-health-education/relationships-and-sex-education-rse-secondary.

Department for Education (2020). Teaching about Mental Wellbeing. GOV.UKAvailable at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/teaching-about-mental-wellbeing.

Department of Health - Department of Education (2017). Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision: A green Paper. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/664855/Transforming_children_and_young_people_s_mental_health_provision.pdf (Accessed December 4, 2017).

Döring, N. (2014). Consensual Sexting Among Adolescents: Risk Prevention through Abstinence Education or Safer Sexting? Cyberpsychology: J. Psychosocial Res. Cyberspace 8 (1), 9. doi:10.5817/cp2014-1-9

Dubicka, B., and Theodosiou, L. (2020). Technology Use and the Mental Health of Children and Young People. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Duke, É., and Montag, C. (2017). Smartphone Addiction, Daily Interruptions and Self-Reported Productivity. Addict. Behaviors Rep. 6, 90–95. doi:10.1016/j.abrep.2017.07.002

Felisoni, D. D., and Godoi, A. S. (2018). Cell Phone Usage and Academic Performance: An experiment. Comput. Edu. 117, 175–187. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2017.10.006

Fumero, A., Marrero, R. J., Bethencourt, J. M., and Peñate, W. (2020). Risk Factors of Internet Gaming Disorder Symptoms in Spanish Adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 111, 106416. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2020.106416

Gainsbury, S. M. (2014). Review of Self-Exclusion from Gambling Venues as an Intervention for Problem Gambling. J. Gambl Stud. 30 (2), 229–251. doi:10.1007/s10899-013-9362-0

Gao, Q., Yan, Z., Zhao, C., Pan, Y., and Mo, L. (2014). To Ban or Not to Ban: Differences in mobile Phone Policies at Elementary, Middle, and High Schools. Comput. Hum. Behav. 38, 25–32. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.05.011

Gazzaley, A., and Rosen, L. D. (2016). The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains in a High-Tech World. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Griffiths, M. D., Lopez-Fernandez, O., Throuvala, M. A., Pontes, H., and Kuss, D. J. (2018). “Excessive and Problematic Use of Social media in Adolescence: A Brief Overview,” Report number: SMH0091. Available at: http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/science-and-technology-committee/social-media-and-mental-health/written/81105.pdf.

Gugushvili, N., Täht, K., Rozgonjuk, D., Raudlam, M., Ruiter, R., and Verduyn, P. (2020). Two Dimensions of Problematic Smartphone Use Mediate the Relationship between Fear of Missing Out and Emotional Well-Being. Cyberpsychology: J. Psychosocial Res. 14 (2). doi:10.5817/CP2020-2-3

Harris, A., and Griffiths, M. D. (2017). A Critical Review of the Harm-Minimisation Tools Available for Electronic Gambling. J. Gambl Stud. 33 (1), 187–221. doi:10.1007/s10899-016-9624-8

Hygen, B. W., Skalická, V., Stenseng, F., Belsky, J., Steinsbekk, S., and Wichstrøm, L. (2020). The Co‐occurrence Between Symptoms of Internet Gaming Disorder and Psychiatric Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence: Prospective Relations or Common Causes? J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatr. 61 (8), 890–898. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13289

Jamshed, S. (2014). Qualitative Research Method-Interviewing and Observation. J. Basic Clin. Pharma 5 (4), 87–88. doi:10.4103/0976-0105.141942

Kanjo, E., Kuss, D. J., and Ang, C. S. (2017). NotiMind: Utilizing Responses to Smart Phone Notifications as Affective Sensors. IEEE Access 5, 22023–22035. doi:10.1109/access.2017.2755661

Kircaburun, K., Griffiths, M. D., and Billieux, J. (2018). Trait Emotional Intelligence and Problematic Online Behaviors Among Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Mindfulness, Rumination and Depression. Personal. Individual Differences 139, 208–213. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2018.11.024

Klobas, J. E., McGill, T. J., Moghavvemi, S., and Paramanathan, T. (2018). Compulsive YouTube Usage: A Comparison of Use Motivation and Personality Effects. Comput. Hum. Behav. 87, 129–139. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.038

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Koo, H. J., and Kwon, J.-H. (2014). Risk and Protective Factors of Internet Addiction: A Meta-Analysis of Empirical Studies in Korea. Yonsei Med. J. 55 (6), 1691–1711. doi:10.3349/ymj.2014.55.6.1691

Kuss, D. J., and Griffiths, M. D. (2011). Online Social Networking and Addiction—A Review of the Psychological Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 8 (12), 3528–3552. doi:10.3390/ijerph8093528

Kuss, D. J., and Lopez-Fernandez, O. (2016). Internet Addiction and Problematic Internet Use: A Systematic Review of Clinical Research. World J. Psychiatry 6 (1), 1–34. doi:10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.143

Kuss, D. J., and Pontes, H. M. (2019). Internet Addiction. Evidence-Based Practice in Psychotherapy. Vol. 41. Boston, MA: Hogrefe Publishsing Corp.

Kutcher, S., Wei, Y., and Hashish, M. (2016). “Mental Health Literacy for Students and Teachers: A ‘school Friendly’ Approach,” in Positive Mental Health, Fighting Stigma and Promoting Resiliency for Children and Adolescents (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier).

Layard, R., and Hagell, A. (2015). “Healthy Young Minds: Transforming the Mental Health of Children,” Report of the WISH Mental Health and Wellbeing in Children Forum. Available at: https://www.mhinnovation.net/sites/default/files/downloads/resource/WISH_Wellbeing_Forum_08.01.15_WEB.pdf (Accessed March 20, 2019).

Lemmens, J. S., Bushman, B. J., and Konijn, E. A. (2006). The Appeal of Violent Video Games to Lower Educated Aggressive Adolescent Boys from Two Countries. CyberPsychology Behav. 9 (5), 638–641. doi:10.1089/cpb.2006.9.638

Lin, M.-P., Wu, J. Y.-W., You, J., Hu, W.-H., and Yen, C.-F. (2018). Prevalence of Internet Addiction and its Risk and Protective Factors in a Representative Sample of Senior High School Students in Taiwan. J. Adolescence 62, 38–46. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.11.004

Livingstone, S., and Helsper, E. (2010). Balancing Opportunities and Risks in Teenagers' Use of the Internet: the Role of Online Skills and Internet Self-Efficacy. New Media Soc. 12 (2), 309–329. doi:10.1177/1461444809342697

Lo, K., Gupta, T., and Keating, J. L. (2018). Interventions to Promote Mental Health Literacy in university Students and Their Clinical Educators. A Systematic Review of Randomised Control Trials. Health Professions Edu. 4 (3), 161–175. doi:10.1016/j.hpe.2017.08.001

Maguire, M., and Delahunt, B. (2017). Doing a Thematic Analysis: A Practical, Step-by-step Guide for Learning and Teaching Scholars. Reflections, Journeys Case Stud. 8 (3), 14.

Marchica, L. A., Mills, D. J., Derevensky, J. L., and Montreuil, T. C. (2019). The Role of Emotion Regulation in Video Gaming and Gambling Disorder. Can. J. Addict. 10 (4), 19–29. doi:10.1097/cxa.0000000000000070

Marino, C., Vieno, A., Lenzi, M., Fernie, B. A., Nikčević, A. V., and Spada, M. M. (2018). Personality Traits and Metacognitions as Predictors of Positive Mental Health in College Students. J. Happiness Stud. 19, 365–379. doi:10.1007/s10902-017-9908-4

Mayer, J. D., and Geher, G. (1996). Emotional Intelligence and the Identification of Emotion. Intelligence 22 (2), 89–113. doi:10.1016/s0160-2896(96)90011-2

McNaughton, S., Rosedale, N., Jesson, R. N., Hoda, R., and Teng, L. S. (2018). How Digital Environments in Schools Might Be Used to Boost Social Skills: Developing a Conditional Augmentation Hypothesis. Comput. Edu. 126, 311–323. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2018.07.018

Mentally Healthy schools (2018). Whole-school Approach. Mentally Healthy schoolsAvailable at: https://www.mentallyhealthyschools.org.uk/whole-school-approach/.

Newzoo. Newzoo’s (2020). Global Mobile Market Report | Newzoo Platform. NewzooAvailable at: https://newzoo.com/products/reports/global-mobile-market-report/.

NHS Digital (2018). One in Eight of Five to 19 Year Olds Had a Mental Disorder in 2017 Major New Survey Finds. NHS DigitalAvailable at: https://digital.nhs.uk/news-and-events/latest-news/one-in-eight-of-five-to-19-year-olds-had-a-mental-disorder-in-2017-major-new-survey-finds.

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., and Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic Analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 16 (1), 160940691773384. doi:10.1177/1609406917733847

Ophir, E., Nass, C., and Wagner, A. D. (2009). Cognitive Control in media Multitaskers. Pnas 106 (37), 15583–15587. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903620106

Opiola, K. K., Alston, D. M., and Copeland-Kamp, B. L. (2020). The Effectiveness of Training and Supervising Urban Elementary School Teachers in Child-Teacher Relationship Training: A Trauma-Informed Approach. Prof. Sch. CounselingProfessional Sch. Couns. 23 (1_part_2), 2156759X1989918. doi:10.1177/2156759x19899181

Orben, A. (2020). Teenagers, Screens and Social media: a Narrative Review of Reviews and Key Studies. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 55, 407–414. doi:10.1007/s00127-019-01825-4

Orpinas, P., and Horne, A. M. (2004). A Teacher-Focused Approach to Prevent and Reduce Students' Aggressive Behavior. Am. J. Prev. Med. 26 (1 Suppl. l), 29–38. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.016

Osher, D., Kidron, Y., Brackett, M., Dymnicki, A., Jones, S., and Weissberg, R. P. (2016). Advancing the Science and Practice of Social and Emotional Learning. Rev. Res. Edu. 40 (1), 644–681. doi:10.3102/0091732x16673595

Pantiwati, Y. (2013). Authentic Assessment for Improving Cognitive Skill, Critical-Creative Thinking and Meta-Cognitive Awareness. J. Educ. Pract. 4, 1–9.

Patton, G. C., Sawyer, S. M., Santelli, J. S., Ross, D. A., Afifi, R., Allen, N. B., et al. (2016). Our Future: A Lancet Commission on Adolescent Health and Wellbeing. The Lancet 387 (10036), 2423–2478. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)00579-1

Picherot, G., Cheymol, J., Assathiany, R., Barthet-Derrien, M.-S., Bidet-Emeriau, M., Blocquaux, S., et al. (2018). Children and screens: Groupe de Pédiatrie Générale (Société française de pédiatrie) guidelines for pediatricians and families. Arch. de Pédiatrie 25 (2), 170–174. doi:10.1016/j.arcped.2017.12.014

Przybylski, A. K., and Weinstein, N. (2017). A Large-Scale Test of the Goldilocks Hypothesis. Psychol. Sci. 28 (2), 204–215. doi:10.1177/0956797616678438

Przybylski, A. K., and Weinstein, N. (2019). Digital Screen Time Limits and Young Children's Psychological Well‐Being: Evidence from a Population‐Based Study. Child. Dev. 90 (1), e56–e65. doi:10.1111/cdev.13007

Rach, M., and Lounis, M. (2021). “The Focus on Students' Attention! Does TikTok's EduTok Initiative Propose an Alternative Perspective to the Design of Institutional Learning Environments?,” in Integrated Science in Digital Age 2020. Editor T. Antipova (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 241–251. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-49264-9_22

Robertson, T. W., Yan, Z., and Rapoza, K. A. (2018). Is Resilience a Protective Factor of Internet Addiction? Comput. Hum. Behav. 78, 255–260. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.09.027

Rumpf, H.-J., Brandt, D., Demetrovics, Z., Billieux, J., Carragher, N., Brand, M., et al. (2019). Epidemiological Challenges in the Study of Behavioral Addictions: A Call for High Standard Methodologies. Curr. Addict. Rep. 6 (3), 331–337. doi:10.1007/s40429-019-00262-2

Sakuma, H., Mihara, S., Nakayama, H., Miura, K., Kitayuguchi, T., Maezono, M., et al. (2017). Treatment with the Self-Discovery Camp (SDiC) Improves Internet Gaming Disorder. Addict. Behaviors 64, 357–362. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.06.013

Sammons, P., Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Siraj, I., Taggart, B., Smees, R., et al. (2014). Influences on Students’ Social-Behavioural Development at Age 16 - Effective Pre-school, Primary & Secondary Education Project (EPPSE) Research Brief. Department for EducationAvailable from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/351489/RB351_-_Influences_on_students__social-behavioural_development_at_age_16_Brief.pdf.

Sancassiani, F., Pintus, E., Holte, A., Paulus, P., Moro, M. F., Cossu, G., et al. (2015). Enhancing the Emotional and Social Skills of the Youth to Promote Their Wellbeing and Positive Development: A Systematic Review of Universal School-Based Randomized Controlled Trials. CPEMH 11 (1), 21–40. doi:10.2174/1745017901511010021

Schultze-Krumbholz, A., and Scheithauer, H. (2013). Is Cyberbullying Related to Lack of Empathy and Social-Emotional Problems? Int. J. Dev. Sci. 7 (3–4), 161–166. doi:10.3233/dev-130124

Shek, D. T. L., and Ma, C. M. S. (2014). Effectiveness of a Chinese Positive Youth Development Program: the Project P.A.T.H.S. In Hong Kong. Int. J. Disabil. Hum. Dev. 13 (4), 489–496. doi:10.1515/ijdhd-2014-0346

Shek, D. T. L., and Ma, C. M. S. (2016). A Six-Year Longitudinal Study of Consumption of Pornographic Materials in Chinese Adolescents in Hong Kong. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 29 (1), S12–S21. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2015.10.004

Shek, D. T. L., Ma, H. K., and Sun, R. C. F. (2011). Development of a New Curriculum in a Positive Youth Development Program: The Project P.A.T.H.S. In Hong Kong. Scientific World J. 11, 2207–2218. doi:10.1100/2011/289589

Sohn, S., Rees, P., Wildridge, B., Kalk, N. J., and Carter, B. (2019). Prevalence of Problematic Smartphone Usage and Associated Mental Health Outcomes Amongst Children and Young People: a Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and GRADE of the Evidence. BMC Psychiatry 19, 356. doi:10.1186/s12888-019-2393-z

Spada, M. M., Caselli, G., Nikčević, A. V., and Wells, A. (2015). Metacognition in Addictive Behaviors. Addict. Behaviors 44, 9–15. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.08.002

Spada, M. M., Langston, B., Nikčević, A. V., and Moneta, G. B. (2008). The Role of Metacognitions in Problematic Internet Use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 24 (5), 2325–2335. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2007.12.002

Stathopoulou, A., Siamagka, N.-T., and Christodoulides, G. (2019). A Multi-Stakeholder View of Social media as a Supporting Tool in Higher Education: An Educator-Student Perspective. Eur. Manag. J. 37 (4), 421–431. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2019.01.008

Stevenson, F., and Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent Resilience: A Framework for Understanding Healthy Development in the Face of Risk. Annu. Rev. Public Health 26, 399–419. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357