94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 25 November 2021

Sec. Leadership in Education

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.643196

This article is part of the Research Topic Emotions and Leadership in Organizations and Educational Institutes View all 21 articles

Simone Schoch1*

Simone Schoch1* Roger Keller1

Roger Keller1 Alex Buff1

Alex Buff1 Jasper Maas2

Jasper Maas2 Pamela Rackow3

Pamela Rackow3 Urte Scholz4

Urte Scholz4 Julia Schüler5

Julia Schüler5 Mirko Wegner6

Mirko Wegner6Basic psychological need satisfaction is essential for the wellbeing of teachers and motivation at work. Transformational leadership contributes to the development and maintenance of a respectful, constructive atmosphere, a supportive working climate, and has been suggested to be a crucial factor for the satisfaction of the need for relatedness of employees. Transformational leadership is also considered as an ideal leadership style in the school setting, but most studies did not distinguish between individual and team effects of this leadership behavior. In the present study, we applied the dual-focused model of transformational leadership and focused on social processes to address the question of whether individual- and group-focused transformational leadership behavior contribute differently to satisfaction of the need for relatedness of teachers. Based on longitudinal data with three measurement points across one school year of N = 1,217 teachers, results of structural equational models supported the notion of the dual effects of transformational leadership: Individual-focused transformational leadership was directly positively related to change in satisfaction of the need for relatedness of teachers. The relationship between group-focused transformational leadership and change in satisfaction of the need for relatedness was mediated by received social support from team members. These findings emphasize the importance of school leadership behavior of principals for satisfaction of the need for relatedness of teachers. The satisfaction of the need for relatedness is, therefore, not only satisfied through the direct interaction between the school principal and the individual teacher but also through interactions of the school principal with the whole team. Our results confirm that school principals should focus their leadership behavior both on individual need satisfaction of teachers as well as on team development.

Teaching is considered as a particularly challenging profession involving a wide range of job demands such as dealing with work overload, school class heterogeneity, cooperation within and outside the school, and administrative tasks (e.g., Brägger, 2019; Keller-Schneider, 2018; Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2018). The motivation, well-being, and health of teachers are important preconditions to meet these demands and to fulfill the educational mandate (Nieskens, 2006; Sieland, 2006). According to the Self-Determination Theory (Deci and Ryan, 1985; Deci and Ryan, 2000), individuals experience wellbeing and motivation when their basic psychological needs are satisfied. There is a significant amount of research in the educational setting indicating that psychological need satisfaction of teachers is positively associated with effective teaching (Holzberger et al., 2014; Moè and Katz, 2020), work engagement, job satisfaction, commitment, well-being, enjoyment, and happiness at work (Collie, 2016; Aldrup, 2017; Rothmann and Fouché, 2018).

Another substantial body of literature shows that leadership behavior—and transformational leadership, in particular—is essential for the psychological need satisfaction of individuals (Gagné and Deci, 2005; Hetland, 2011; Kovjanic, 2013; Stenling and Tafvelin, 2014). Moreover, according to the Self-Determination Theory (Deci and Ryan, 1985; Deci and Ryan, 2000), social support was found to be a key predictor of satisfaction of the need for relatedness (e.g., Aldrup et al., 2017; Leow et al., 2019).

Current research in educational settings emphasizes diverse leadership styles (e.g., shared leadership, distributed leadership, instructional leadership, transformational leadership, sustainable leadership) that focus on different outcomes including teaching quality, goal attainment, lifelong learning, or teachers’ commitment, and effort toward school reform (e.g., Berkovich, 2018; Geijsel, Sleegers, Leithwood, and Jantzi, 2003; Schratz et al., 2016; Taşçi and Titrek, 2019). Although a variety of conceptual models have been focused over the past 35 years of research into educational leadership, transformational leadership was one of the dominating approaches as it was considered to be ideal leadership and relevant to schooling challenges of the 21st century (Hallinger, 2003; Berkovich, 2018). However, most studies have not distinguished between individual and team effects of transformational leadership. In this study, we examine the association between the transformational leadership behavior of school principals and the need satisfaction of teachers. Furthermore, we aimed to identify the underlying mechanisms of the link between transformational leadership and need satisfaction of teachers. By focusing on social processes, we address the role of social support as a mediator and satisfaction of the need for relatedness as a social outcome.

Transformational leadership is defined as the ability of a leader to motivate followers to transcend their own personal goals for the greater good of the organization (Bass, 1996). The concept of transformational leadership assumes that leadership may well be shared, coming from the principals as well as from teachers (Leithwood and Jantzi, 2000). The dual-focused model of transformational leadership addresses exactly this issue (Wang et al., 2010): The model differentiates aspects of leadership behaviors directed 1) toward individual team members, and 2) toward a team as a whole. The dual-focused model of transformational leadership assumes two independent dimensions of leadership behavior that enables a transformational leader to address a single team member (individual-focused transformational leadership) and an organizational unit as a group (group-focused transformational leadership) (Kark and Shamir, 2013; Wang et al., 2010). Thus, the present research focuses on the differentiated impact of individual- and group-focused leadership on the need satisfaction of the teachers.

Individual-focused transformational leadership behavior aims at developing the abilities and skills of individual employees, improving their self-efficacy and self-esteem, and empowering them to develop their full potential (Wang et al., 2010). To achieve these aims within a school context, the school principal influences teachers by taking an interest in them as individuals, understanding their skills, abilities, and needs, and providing them with customized coaching and mentoring (Kark and Shamir, 2013; Leithwood et al., 1998). By focusing on the individual, a transformational leader tailors his or her behavior to the specific person. In contrast, group-focused transformational leadership behavior aims at communicating the importance of group goals, developing shared values and beliefs, and inspiring unified efforts to achieve group goals. Furthermore, it refers to leadership behaviors that aim to communicate a group vision, to emphasize group identity, and to promote team-building (Leithwood et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2010). To achieve the aims of group-focused transformational leadership, the school principal influences the whole group of teachers by exhibiting similar behavior toward different members of the group (Yammarino and Bass, 1990). By focusing on the group, a transformational school leader tailors his or her behavior to all members of a team.

There is general agreement, based on the accumulated research evidence in the educational setting, that transformational leadership is associated with many positive outcomes, such as greater teacher motivation, commitment, effort, organizational effectiveness, and student outcomes (Eyal and Roth, 2011; Geijsel et al., 2003; Leithwood and Jantzi, 2005; Leithwood and Sun, 2012). According to Bass (1990), a central consequence of transformational leadership is the satisfaction of the needs of employees. A transformational leader, for example, is defined as a person who “seeks to satisfy higher needs and engages the full potential for the follower” (Burns, 1978, p. 4). Behavioral components such as individualized support, intellectual stimulation, and personal vision suggest that transformational leadership is grounded in understanding the needs of individual employee (Hallinger, 2003). Needs, in turn, are central aspects of the Self-Determination Theory (Deci and Ryan, 1985, Deci and Ryan, 2000). The Self-Determination Theory postulates three universal, innate basic psychological needs that are essential for optimal human functioning: the need for autonomy, the need for competence, and the need for social relatedness. The need to form and maintain relationships is considered a central human need (Baumeister and Leary, 1995) and was found to be particularly important for teachers (Butler, 2012). In the present study we therefore focus on the satisfaction of the need for relatedness. The need for relatedness involves feelings of respect, understanding, and connectedness which result from strong interpersonal relationships (Deci and Ryan, 2000).

With the focus on satisfaction of the need for relatedness of followers, empirical studies in the non-school setting have shown direct positive associations with transformational leadership (Hetland et al., 2011; Kovjanic et al., 2013; Kovjanic et al., 2012; Stenling and Tafvelin, 2014). The authors concluded that transformational leadership might satisfy the need for social relatedness by taking the individuality of their followers into consideration, and simultaneously strengthening team spirit by communicating common visions.

Social support is central to social interaction (Knoll and Kienle, 2007) and refers to the qualitative aspect of helping between two parties. Importantly, there are different types of supportive interactions. Perceived or anticipated social support describes the support that a person thinks is potentially available in their social network when help is needed (Knoll and Kienle, 2007). Studies indicate that perceived social support is a stable rather than modifiable characteristic (e.g., Sarason et al., 1987). Perceived social support is also independent from the behavior of a specific network member and, therefore, not a good indicator for supportive interactions (Knoll and Kienle, 2007). In contrast, received social support is the retrospective report of actual support transactions from specific network members (Uchino, 2009; Schwarzer, 2010). As the expectation of being supported (i.e., perceived social support) does not inevitably correspond with the concrete support received in a challenging situation (Uchino 2009), the present study focuses on received social support from teacher colleagues. In school settings, teachers name social support from colleagues among the most important factors to cope with work-related stressors (e.g., Schaarschmidt and Fischer, 2001).

Several studies highlight the significance of social support for the satisfaction of the need for relatedness of followers (e.g., Fernet et al., 2013; van den Broeck et al., 2010, Vansteenkiste, Witte, Soenens, and Lens, 2010). Receiving social support is assumed to generate an energizing and motivational process by satisfying basic psychological needs (Gagné and Deci 2005; Bakker et al., 2014).

An important consequence of transformational leadership is creating a positive climate in a school and a culture of care, respect, and cooperation (Yu et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2010). Social support among teachers is a key component for creating a good climate in a school (Schaarschmidt and Fischer, 2001; Eckert et al., 2013; Rothland, 2013). Several studies from non-school settings found that transformational leadership is positively associated with helping behavior among team members, which is closely related to social support (Podsakoff et al., 2000; Zaccaro et al., 2001; Kozlowski et al., 2009). Thus, it can be expected that school principals who apply transformational leadership can enhance social support among teachers at their school.

However, previous studies have not considered the dual effects of transformational leadership that unfold through the dyadic interaction of the leader with individual followers, as well as through interactions between the leader and the whole team.

According to Wang et al. (2010) individual-focused transformational leadership behavior consists of four different dimensions: communicating high expectations, follower development, intellectual stimulation, and personal recognition. School principals showing individual-focused transformational leadership behaviors, therefore, encourage teachers to set high goals and display confidence in their abilities to achieve these goals, help them to find their individual strengths, challenge them to think about old problems in new ways, and acknowledge improvements in the quality of their work. Individual-focused transformational leadership is found to be positively related to individual performance (Wang et al., 2010), individual skill development (Dong et al., 2017), individual needs (Klaic et al., 2018), and individual teacher efficacy (Windlinger et al., 2019). The evidence, to date suggests that individual-focused transformational leadership is primarily related to individual outcomes, and therefore, the individual-focused transformational leadership behavior of school principals should be directly positively related to satisfaction of the need for relatedness of teachers.

Group-focused transformational leadership behavior consists of three dimensions: emphasizing group identity, communicating a group vision, and team-building (Wang et al., 2010). Specifically, school principals showing group-focused transformational leadership behaviors display pride in the achievement of the groups, highlight the common interests and values among team members, encourage team members to be proud of their team, communicate a clear direction of where the team is going, and support teamwork among team members. Group-focused transformational leadership is found to be positively related to knowledge sharing and creativity within the team (Dong et al., 2017), group identification (Wang and Howell, 2012), and collective teacher efficacy (Windlinger et al., 2019). Moreover, group-focused transformational leadership is found to help group members realign their values according to the vision and goals of the group, thereby encouraging cooperation toward achieving the vision and goals of the group (Jung and Sosik, 2002). Group-focused transformational leadership also requires followers to help each other to facilitate the progress of the group (Wang et al., 2010). For example, being a role model for followers (a typical example of group-focused leadership) was found to create an overall bond between group members such as followers who promote social support within the group (Lyons and Schneider, 2009). In another typical group-focused leadership behavior, individuals who belong to a group with a shared group vision were found to be more likely to support each other (Haslam and Van Dick, 2011). Evidence to date clearly demonstrates that group-focused transformational leadership is primarily related to group-related outcomes, and therefore, it is the group-focused dimension of transformational leadership that should play a prominent role in enhancing social support among teachers.

Most studies in the field of education did not differentiate between individual- and group-focused transformational leadership (for exceptions, see Kark and Shamir, 2013; Windlinger et al., 2019). In consequence, there is limited evidence for differential effects of individual-focused (i.e., dyadic interactions of leaders with individual team members) and group-focused transformational leadership (i.e., leader–team interaction) in the school setting. The present study focuses on social processes and examines different mechanisms of individual- and group-focused transformational leadership behavior on the satisfaction of the need for relatedness of teachers. Based on existing research, we expect a direct effect of individual-focused transformational leadership behavior on satisfaction of the need for relatedness and indirect effect of group-focused leadership mediated by social support of team members. Thus, we advance the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. Individual-focused transformational leadership is positively related to the satisfaction of the need for relatedness of teachers (direct effect).

Hypothesis 2. The association between group-focused transformational leadership and teachers’ satisfaction of the need for relatedness is mediated by received social support from team colleagues (indirect effect).

Figure 1 shows the hypothesized relationships between individual- and group-focused transformational leadership, social support, and satisfaction of the need for relatedness.

FIGURE 1. Hypothesized paths between dual-focused transformational leadership, social support, and satisfaction of the need for relatedness.

The hypotheses were examined in a sample of teachers at primary (pupils aged 5–12 years) and lower-secondary (pupils aged 13–15 years) compulsory school level in the German-speaking part of Switzerland. Eligible for participation were teachers that met the following criteria: Teaching primary or lower secondary school level, having a minimum workload of 10 lessons per week, and working at a school with a formal school principal. The participants were recruited through cantonal teacher organizations, and they registered individually for participation by giving written informed consent. By applying this recruitment method, a wide range of teachers with different school principals could be recruited, preventing a nested data structure.

After providing informed consent, the participants completed online questionnaires. Data collection took part at three measurement points across the school year 2017/2018: The first questionnaire (T1) was assessed in September 2017 at the beginning of the school year, the second (T2) mid-school year in January 2018 (T2), and the third (T3) May 2018 almost at the end of the school year. The completion of each questionnaire took 45 min on average. All participants received a voucher worth 25 Swiss francs for each completed online questionnaire as compensation.

In total N = 1,365 participants gave written informed consent. Of these, n = 146 participants were excluded: n = 110 participants did not fulfill the criteria of participation, further n = 38 persons were excluded because they did not have the same school principal during the entire period of data collection (T1–T3). The final sample consisted of N = 1,217 participants (79% women, M = 43.44 years, SD = 11.23, age range 22–65 years). In some of the analyses further participants were excluded because of missing values in all variables included in the analyses. Mean employment level was M = 79% (SD = 19%) of a full time equivalent and the mean teaching experience of the sample was M = 17.81 (SD = 10.87) years. 73.1% of the participants were teaching at primary school level, 22.8% at lower-secondary school level, and 4.0% taught both at primary and secondary school level. Although the study did not aim to obtain representative data, the sample corresponded largely to the population of teachers in the German-speaking part of Switzerland in the school year 2016/2017 (Federal Statistical Office, 2018).

Individual and group-focused transformational leadership. Individual- and group-focused transformational leadership was measured with an adapted version of the German version of the Dual-Level Transformational Leadership Scale (Klaic et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2010) at T1. In contrast to the most common instrument used in education leadership research [Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) (Leithwood and Jantzi, 2005)], this instrument differentiates clearly between individual- and group-focused transformation leadership. The original scales of individual-focused level of transformational leadership consist of 18 items (e.g., “My supervisor shows confidence in my ability to meet performance expectations”), and the group-focused level of transformational leadership consists of 16 items (e.g., “My supervisor says things that make us feel proud to be members of this team”). The response scales ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (frequently, if not always). In total, four items were excluded because content validity was not given as they did not fit the educational context, i.e., three items from the individual-focused level and one item from the group-focused level. Both the individual- and the group-focused level therefore consisted of 15 items. Cronbach’s α was 0.91 for individual-focused level of transformational leadership (M = 3.02, SD = 0.95) and Cronbach’s α was 0.91 for group-focused level of transformational leadership (M = 3.13, SD = 0.96).

Received social support from team colleagues. At T2, the well-established instrument “Berlin Social Support Scales (BSSS)” (Schulz and Schwarzer, 2003) was used. The original scale was slightly reformulated to better fit the school setting and to take into account school team colleagues as providers of social support. The original scale consists of 13 items. The three negatively worded items were excluded because they did not load on the intended factor but constituted a separate factor—a phenomenon that appears to be rather common for negatively worded items (Barnette, 2000). Furthermore, one item was excluded because content validity was not given, as it did not describe an action of support. The adapted scale consisted of nine items. A sample item was “My colleagues assured me that I can rely completely on them.” The response scale ranged from 1 (not true) to 6 (absolutely true). Cronbach’s α was 0.93 (M = 4.69, SD = 1.07).

Satisfaction of the need for relatedness. Satisfaction of the need for relatedness of teachers at work was assessed with the subscale “satisfaction of the need for relatedness” from the German version of the Work-related Basic Need Satisfaction scale (Van den Broeck et al., 2010) at T1 and T3. The scale consisted of six items. A sample item was “At work, I feel part of a group.” The response scale ranged from 1 (not true at all) to 5 (absolutely true). Cronbach’s α was 0.82 at T1 (M = 3.97, SD = 0.76) and 0.84 at T3 (M = 3.94, SD = 0.79).

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS 26 and Mplus 8 (Muthén and Muthen, 2017). To analyze the different models, we used the robust maximum likelihood estimation (MLR), which is robust against violations of normality assumptions (Marsh et al., 2018). Full informational maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) was used to handle missing data (Graham and Coffman, 2012).

As shown above (see measures section), three out of four scales contain a relatively large number of items, which leads to a very large number of model parameters to be estimated when modeling the overall model. In order to reduce the number of the model parameters to be estimated, we used the item parceling method (Little et al., 2002) to build the indicators for the latent constructs used in our analyses. For each scale three parcels were built using the balancing approach (Little et al., 2002; Little, 2013).

To identify the model and to determine the metric of the latent variable, “factor coding” was used (Little, 2013). Accordingly, we fixed the means of the latent constructs to zero, and the variances of the constructs to one.

Model fit was assessed using the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). A model fit can be seen as good if CFI and TLI ≥0.95 and RMSEA and SRMR ≤0.05 (Little, 2013; Brown, 2015).

The postulated indirect effect was estimated by means of bias-corrected bootstrap method (MacKinnon et al., 2004). As recommended, we used a large number of bootstrap resamples (10,000) (Geiser, 2012).

As satisfaction of the need for relatedness was measured twice (T1 and T3), we tested longitudinal measurement invariance of this construct. We tested configural invariance (factor loadings and intercepts of indicators are freely estimated across two waves), metric invariance (factor loadings of corresponding indicators are identical across two waves) and scalar invariance (factor loadings and intercepts of corresponding indicators are identical across two waves) (Little, 2013). Thus, comparisons across this series of increasingly restricted models starting from an unrestricted model (i.e., configural invariance) provided information on the level of invariance that could be achieved.

As recommended, we did not use the Chi2 difference test to evaluate measurement invariance because it is overly sensitive to sample size (Marsh et al., 1988; Meade et al., 2008). Instead, we followed the guidance of Cheung and Rensvold (2002) who recommend a change of >−0.010 in CFI as an indication of non-invariance provided an adequate sample size is obtained.

The fit of the configural, metric, and scalar invariance models was good to excellent. The loss of fit in the metric and scalar invariance models in terms of ΔCFI was below the recommended cutoff value (Table 1). As such, it can be concluded that the satisfaction of the need for relatedness scale showed longitudinal scalar invariance.

Table 2 shows the Pearson’s correlations between all latent variables of the model. All variables were significantly correlated and consistent with theory. According to Cohen (1988) there were strong correlations between individual- and group-focused transformational leadership (r = 0.838), between satisfaction of the need for relatedness at T1 and T3 (r = 0.815), and between received social support at T2 and satisfaction of the need for relatedness at T1 (r = 0.566) and T3 (r = 0.600), respectively.

We included individual- and group-focused transformational leadership at T1, received social support from team colleagues at T2, and satisfaction of the need for relatedness at T1 and T3 in our longitudinal structural equation model to test the hypothesized paths between individual- and group-focused transformational leadership and satisfaction of the need for relatedness. As satisfaction of the need for relatedness at T1 was included in the model in order to control for prior need satisfaction, the effects of all other predictor variables are allowed to be interpreted as effects on satisfaction of the need for relatedness at T3 (i.e., change in satisfaction of the need for relatedness) (Trautwein, 2007, Study 2).

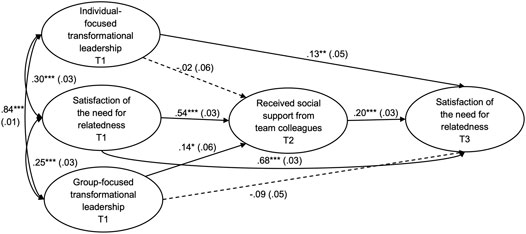

Figure 2 shows the structural equation model with all tested direct effects (standardized coefficients, β). When interpreting standardized regression coefficients, Keith (2015) recommends to categorize β < 0.10 as being small, β > 0.10 and β < 0.25 as being moderate, and β > 0.25 as being large. The fit of the model was good: χ2 = 184.756, df = 77, p < 0.001, Cfit = 1.000, CFI = 0.991, TLI = 0.988, RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.034 (0.028, 0.040), SRMR = 0.020.

FIGURE 2. Structural equation model with standardized estimated values of the relationship between individual- and group-focused trasformational leadership, received social support, and satisfaction of the need for relatedness with standardized regression coefficients. All coefficients are standardized, and their corresponding standard errors are in parentheses. Nonsignificant paths are shown as dashed lines; N = 1215. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.01.

As hypothesized in Hypothesis 1, there was a moderate significant direct positive effect from individual-focused transformational leadership on change in the satisfaction of the need for relatedness of teachers (β = 0.13, p < 0.01). Moreover, as predicted, the indirect effect on change in the satisfaction of the need for relatedness of teachers mediated by received social support from team colleagues was not significant, β = −0.003, p = 0.81 [95% CI (−0.025, 0.019)].

Confirming our Hypothesis 2, there was a small significant indirect effect from group-focused transformational leadership on change in teachers’ satisfaction of the need for relatedness mediated by received social support from colleagues β = 0.03, p < 0.05 [95% CI (0.008, 0.054)]. The indirect effect was explained by a moderate positive effect from group-focused transformational leadership on received social support from team colleagues (β = 0.14, p < 0.05), which in turn was moderately positively related to change in teachers’ satisfaction of the need for relatedness (β = 0.20, p < 0.001).

Furthermore, satisfaction of the need for relatedness (T1) was a powerful predictor for received social support from team colleagues (T2) (β = 0.54, p < 0.001). The strong effect between T1 and T3 satisfaction of the need for relatedness (β = 0.68, p < 0.001) indicates that satisfaction of the need for relatedness is stable over time. Even though these effects are large, transformational leadership (T1) and received social support from team colleagues (T2) still contributed moderately to the change in the need satisfaction of teachers in the hypothesized way.

Previous research has shown that teaching is a challenging profession involving a broad range of job demands (e.g., Brägger, 2019; Keller-Schneider et al., 2018; Lee and Nie, 2014; Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2018). The motivation, well-being, and health of teachers are essential preconditions to meeting these demands (Nieskens, 2006; Sieland, 2006). To stay healthy and motivated, basic psychological need satisfaction is essential (e.g., Ryan and Deci, 2000). Prior studies outside the educational setting found that transformational leadership is positively associated with psychological need satisfaction (Hetland et al., 2011; Kovjanic et al., 2013). Transformational leadership is also considered as an ideal leadership style in the school setting (Hallinger, 2003; Berkovich, 2018), but most studies did not distinguish between individual and team effects of this leadership behavior. In the present study, we focused on social processes and addressed the question of whether individual-focused and group-focused transformational leadership behavior contributes differently to the satisfaction of the need for relatedness of teachers. We argued that individual-focused transformational leadership is directly related to the satisfaction of the need for relatedness of teachers, whereas the association between group-focused transformational leadership and satisfaction of the need for relatedness is mediated by received social support from team colleagues. Applying longitudinal structural equation modeling, the results supported our hypotheses.

Taken together, the current findings provide several insights into the role of the transformational leadership behavior of school principals and received social support for the need satisfaction of teachers. Our results support first findings within educational settings showing that transformational leadership can be differentiated into individual- and group-focused leadership behaviors (Windlinger et al., 2019). The current results indicate that this distinction is important for the psychological need satisfaction of teachers. Consistent with the dual-focused transformational leadership model, we were able to show two different mechanisms. 1) Individual-focused transformational leadership behavior (i.e., personal recognition, follower development) is directly related to the satisfaction of the need for relatedness of teachers. In other words, the greater an interest the school principal takes with a teacher as an individual (by empowering individual teachers to develop their full potential, enhance their abilities and skills, acts as a coach or a mentor, or shows personal recognition), the more likely the teacher is to experience satisfaction of their need for relatedness. One reason for the direct effect of individual-focused transformational leadership on the satisfaction of the need for relatedness of teachers might be that teachers experience individual leadership behavior as social support from the school principal. Future studies need to investigate the extent to which the two constructs differ or whether they probably measure the same aspect of the leadership-follower interaction. 2) Group-focused transformational leadership, in turn, is indirectly related to the satisfaction of the need for relatedness of teachers and mediated by received social support from team colleagues. In other words, the more a school principal communicates a clear group vision (such as emphasizing group identity and promoting teambuilding), the more likely a supportive working climate will develop that is positively related to satisfying teachers’ need for relatedness.

To the best of our knowledge, recent research applying the dual-focused model of transformational leadership (e.g., Klaic et al., 2018; Wang and Howell, 2012; Windlinger et al., 2019) have focused on individual- and group-focused outcomes that are independent. Extending these findings, we were able to show that individual- and group-focused outcomes are in fact related to one another (i.e., the group-focused outcome of received social support predicted the individual-focused outcome of satisfaction of the need for relatedness). These finding supports the assumption that transformational leadership is often coming from the principal as well as from the team (Leithwood and Jantzi, 2000). Transformational leadership, thus, makes use of several sources of leadership (Hallinger, 2003).

Future studies should investigate the associations of other group-focused effects (e.g., group identification, team fit, or team performance) with individual need satisfaction, or even with other individual-focused effects (e.g., well-being, satisfaction of the need for autonomy, or self-efficacy).

Moreover, the present findings give further insights in the antecedents of received social support from team colleagues. First, as discussed above, group-focused but not individual-focused transformational leadership is an antecedent of received social support. Second, the effect from satisfaction of the need for relatedness (T1) to receive social support (T2) indicates that the more a need for relatedness of teachers at T1 is satisfied, the more social support she/he receives from the team colleagues at T2. One reason could be that the satisfaction of the need for relatedness makes a person more sociable in a team, which, in turn, leads to team members providing more social support to these individuals. In line with this argumentation, research has shown that social relatedness is experienced, if certain group characteristics are fulfilled (e.g., Ryan and Deci, 2020). These characteristics, in turn, also favor social support. Future studies are needed to examine systematically whether the satisfaction of the need for relatedness is not only a consequence but also an antecedence of received social support. Taken together, our findings demonstrate that the dual-focused model of transformational leadership can also apply in the school setting, i.e., the satisfaction of the need for relatedness can be satisfied not only through the direct interaction between the school principal and the individual teacher but also through interactions of the school principal with the entire team. In future studies, it would be interesting to include other leadership styles. In addition, it would be important to focus on antecedents of transformational leadership, such as personal prerequisites of school principals such as motivations, self-efficacy beliefs, capacities, personality characteristics (Leithwood and Jantzi, 2005), and self-awareness (Titrek and Celik, 2011), as well as variations in the context in which school principals work (Leithwood and Jantzi, 2005).

The main strengths of this study are its use of the dual-focused model transformational leadership behavior, the longitudinal design, and the large sample size. The dual-focused model allowed us to differentiate the effects of individual- and group-focused transformational leadership on individual need satisfaction in the educational setting. By applying longitudinal analyses, we were able to show effects of transformational leadership behavior on changes in the need satisfaction of teachers. Finding these changes in need satisfaction even for a long-time period of approximately 9 months strengthens our findings. Moreover, by covering almost the whole school year, the present study gives valuable insight in the work and leadership reality of teachers across the school year. Although the longitudinal design also required study participants to fill out three online surveys across one school year, which was time consuming, the dropout rate was very low. This led to a large sample size of over a thousand teachers and to the best of our knowledge is one of the largest teacher samples in the German speaking part of Switzerland.

Several limitations do, however, exist and should be kept in mind when interpreting the findings of this study. Although we used a longitudinal design to test the associations between transformational leadership and need satisfaction, conclusions about casual effects cannot be drawn. Future research should test these associations by using an intervention study, in which, randomly chosen groups of school principals would receive transformational leadership training compared with a group receiving no training. Further, our results are based solely on self-report questionnaires from one source (i.e., teachers), which may introduce common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). However, we decided to choose self-reports as we were interested in the interpretation of individuals of the reality rather than in objective measures of transformational leadership, social support, and need satisfaction. Interpretations of individuals are most likely to influence their internal motivational mechanisms (e.g., psychological need satisfaction). Moreover, “objective” indicators may also have shortcomings, such as bias, halo, and stereotype effects of observers (Kerlinger and Lee, 2000).

The present findings underline the importance of transformational leadership behavior for the need satisfaction of employees (Hetland et al., 2011; Kovjanic et al., 2013) and the positive association between received social support and psychological need satisfaction (e.g., Fernet et al., 2013; van den Broeck, Vansteenkiste, 2010). By applying the dual-focused model of transformational leadership, we highlight the importance of both leadership behavior of principals and social support of team members for the need satisfaction of teachers at work. We were also able to examine a social process in leadership research. We conclude that by actively considering the dual dimensions of transformational leadership (i.e., individual- and group-focused) school principals can both directly and indirectly contribute to the need satisfaction of teachers. The indirect effect is explained by received social support from team colleagues. In short, individual consideration, as suggested by Bass and Riggio (2006), is an effective but, by no means, the only leadership strategy. We recommend that school principals focus their leadership behavior on both the individual need satisfaction of teachers and on team development. Team building strategies should, therefore, promote a supportive working climate. Finally, our results highlight that teachers can only benefit from social support if they are willing to accept the support from their team colleagues.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences of the University Zurich (Approval Number 17.6.9). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

SS, RK, JM, PR, US, JS, and MW conceptualized the study. SS, RK, and JM conducted the data collection. SS and AB analyzed the data. SS and RK wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript.

This research was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant 100019M_169788/1; Project “Why does Transformational Leadership Influence Teacher’s Health?—The Role of Received Social Support, Satisfaction of the Need for Relatedness, and the Implicit Affiliation Motive”).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aldrup, K., Klusmann, U., and Lüdtke, O. (2017). Does Basic Need Satisfaction Mediate the Link between Stress Exposure and Well-Being? A Diary Study Among Beginning Teachers. Learn. Instruction 50, 21–30. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.11.005

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., and Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2014). Burnout and Work Engagement: The JD-R Approach. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 1 (1), 389–411. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091235

Barnette, J. J. (2000). Effects of Stem and Likert Response Option Reversals on Survey Internal Consistency: If You Feel the Need, There Is a Better Alternative to Using Those Negatively Worded Stems. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 60 (3), 361–370. doi:10.1177/00131640021970592

Bass, B. M. (1990). From Transactional to Transformational Leadership: Learning to Share the Vision. Organizational Dyn. 18, 19–31. doi:10.1016/0090-2616(90)90061-s

Baumeister, R. F., and Leary, M. R. (1995). The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117 (3), 497–529. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.117.3.49710.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Berkovich, I. (2018). Will it Sink or Will it Float. Educ. Management Adm. Leadersh. 46 (6), 888–907. doi:10.1177/1741143217714253

Broeck, A., Vansteenkiste, M., Witte, H., Soenens, B., and Lens, W. (2010). Capturing Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness at Work: Construction and Initial Validation of the Work-Related Basic Need Satisfaction Scale. J. Occup. Organizational Psychol. 83, 981–1002. doi:10.1348/096317909X481382

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford publications.

Butler, R. (2012). Striving to Connect: Extending an Achievement Goal Approach to Teacher Motivation to Include Relational Goals for Teaching. J. Educ. Psychol., 104(3), 726–742. doi:10.1037/a0028613

Cheung, G. W., and Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating Goodness-Of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance. Struct. Equation Model. A Multidisciplinary J. 9 (2), 233–255. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., Perry, N. E., and Martin, A. J. (2016). Teachers’ Psychological Functioning in the Workplace: Exploring the Roles of Contextual Beliefs, Need Satisfaction, and Personal Characteristics. J. Educ. Psychol. 107 (4), 788–799. doi:10.1037/edu0000088.1

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York: Human Behavior Press.

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The "What" and "Why" of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11 (4), 227–268. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Dong, Y., Bartol, K. M., Zhang, Z.-X., and Li, C. (2017). Enhancing Employee Creativity via Individual Skill Development and Team Knowledge Sharing: Influences of Dual-Focused Transformational Leadership. J. Organiz. Behav. 38 (3), 439–458. doi:10.1002/job.2134

Eckert, M., Ebert, D., and Sieland, B. (2013). “Wie gehen Lehrkräfte mit Belastungen um? Belastungsregulation als Aufgabe und Ziel für Lehrkräfte und Schüler,” in Belastung und Beanspruchung im Lehrerberuf. Editor M. Rothland (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden), 191–211. doi:10.1007/978-3-531-18990-1_11

Eyal, O., and Roth, G. (2011). Principals' Leadership and Teachers' Motivation. J. Educ. Admin 49 (3), 256–275. doi:10.1108/09578231111129055

Federal Statistical Office (2018). Lehrkräfte nach Bildungsstufe 2016/17 (öffentliche Schulen). Neuchatel: Federal statistical office. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/kataloge-datenbanken/tabellen.assetdetail.5146144.html.

Fernet, C., Austin, S., Trépanier, S.-G., and Dussault, M. (2013). How Do Job Characteristics Contribute to Burnout? Exploring the Distinct Mediating Roles of Perceived Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness. Eur. J. Work Organizational Psychol. 22 (2), 123–137. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2011.632161

Gagné, M., and Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination Theory and Work Motivation. J. Organiz. Behav. 26, 331–362. doi:10.1002/job.322

Geijsel, F., Sleegers, P., Leithwood, K., and Jantzi, D. (2003). Transformational Leadership Effects on Teachers' Commitment and Effort toward School Reform. J. Educ. Admin 41 (3), 228–256. doi:10.1108/09578230310474403

Graham, J. W., and Coffman, D. L. (2012). “Structural Equation Modeling with Missing Data,” in Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling. Editor R. H. Hoyle (New York, NY, US: The Guilford Press), 277–295.

Hallinger, P. (2003). Leading Educational Change: Reflections on the Practice of Instructional and Transformational Leadership. Cambridge J. Education 33 (3), 329–352. doi:10.1080/0305764032000122005

Haslam, S. A., and Van Dick, R. (2011). Social Psychology and Organizations. (May), England,UK: Routledge. 325–352. doi:10.4324/9780203846957

Hetland, H., Hetland, J., Schou Andreassen, C., Pallesen, S., and Notelaers, G. (2011). Leadership and Fulfillment of the Three Basic Psychological Needs at Work. Career Dev. Int. 16 (5), 507–523. doi:10.1108/13620431111168903

Holzberger, D., Philipp, A., and Kunter, M. (2014). Predicting Teachers' Instructional Behaviors: The Interplay between Self-Efficacy and Intrinsic Needs. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 39 (2), 100–111. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.02.001

Jung, D. I., and Sosik, J. J. (2002). Transformational Leadership in Work Groups. Small Group Res. 33 (3), 313–336. doi:10.1177/10496402033003002

Kark, R., and Shamir, B. (2013). “The Dual Effect of Transformational Leadership: Priming Relational and Collective Selves and Further Effects on Followers,” in Transformational and Charismatic Leadership: The Road Ahead: 10th Anniversary Edition. Editors B. J. Avolio,, and F. R. Yammarino (Bingley, NY: Emerald), 67–91. doi:10.1108/s1479-357120130000005010

Keith, T. Z. (2015). Multiple Regression and beyond: An Introduction to Multiple Regression and Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd ed. New York and London: Routledge.

Keller-Schneider, M., Yeung, A. S., and Zhong, H. F. (2018). "Supporting Teachers’ Sense of Competence: Effects of Perceived Challenges and Coping Strategies", Teachers and Teacher Education: Global Perspectives, Challenges and Prospects. Editor L. A. Caudle (New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers), 269–289. https://www.novapublishers.com/catalog/product_info.php?products_id=64352.

Kerlinger, F. N., and Lee, H. B. (2000). Foundations of Behavioural Research. 4th ed. Fort Worth: Harcourt.

Klaic, A., Burtscher, M. J., and Jonas, K. (2018). Person-supervisor Fit, Needs-Supplies Fit, and Team Fit as Mediators of the Relationship between Dual-Focused Transformational Leadership and Well-Being in Scientific Teams. Eur. J. Work Organizational Psychol. 27, 669–682. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2018.1502174

Knoll, N., and Kienle, R. (2007). Self-report Questionnaires for the Assessment of Social Support: An Overview. Z. Für Medizinische Psychol. 16, 57–71.

Kovjanic, S., Schuh, S. C., Jonas, K., Quaquebeke, N. V., and van Dick, R. (2012). How Do Transformational Leaders foster Positive Employee Outcomes? A Self-Determination-Based Analysis of Employees' Needs as Mediating Links. J. Organiz. Behav. 33, 1031–1052. doi:10.1002/job10.1002/job.1771

Kovjanic, S., Schuh, S. C., and Jonas, K. (2013). Transformational Leadership and Performance: An Experimental Investigation of the Mediating Effects of Basic Needs Satisfaction and Work Engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 86, 543–555. doi:10.1111/joop.12022

Kozlowski, S. W. J., Watola, D. J., Nowakowski, J. M., Kim, B. H., and Botero, I. C. (2009). “Developing Adaptive Teams: A Theory of Dynamic Team Leadership,” in Team Effectiveness in Complex Organizations: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives and Approaches. Editors E. Salas, G. F. Goodwin, and C. S. Burke (New York, NY: Psychology Press), 113–155.

Lee, A. N., and Nie, Y. (2014). Understanding Teacher Empowerment: Teachers' Perceptions of Principal's and Immediate Supervisor's Empowering Behaviours, Psychological Empowerment and Work-Related Outcomes. Teach. Teach. Education 41, 67–79. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2014.03.006

Leithwood, K., and Jantzi, D. (2005). A Review of Transformational School Leadership Research 1996-2005. Leadersh. Pol. Schools 4 (3), 177–199. doi:10.1080/15700760500244769

Leithwood, K., and Jantzi, D. (2000). Principal and Teacher Leadership Effects: A Replication. Sch. Leadersh. Management 20 (4), 415–434. doi:10.1080/713696963

Leithwood, K., Jantzi, D., and Steinbach, R. (1998). Leadership and Other Conditions Which foster Organizational Learning in Schools. Organizational Learn. Schools 34 (2), 67–90. doi:10.1177/0013161x98034002005

Leithwood, K., and Sun, J. (2012). The Nature and Effects of Transformational School Leadership. Educ. Adm. Q. 48 (3), 387–423. doi:10.1177/0013161X11436268

Leow, K., Lynch, M. F., and Lee, J. (2019). Social Support, Basic Psychological Needs, and Social Well-Being Among Older Cancer Survivors. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 92 (1), 100–114. doi:10.1177/0091415019887688

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., and Widaman, K. F. (2002). To Parcel or Not to Parcel: Exploring the Question, Weighing the Merits. Struct. Equation Model. A Multidisciplinary J. 9 (2), 151–173. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1

Lyons, J. B., and Schneider, T. R. (2009). The Effects of Leadership Style on Stress Outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 20 (5), 737–748. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.06.010

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., and Williams, J. (2004). Confidence Limits for the Indirect Effect: Distribution of the Product and Resampling Methods. Multivariate Behav. Res. 39 (1), 99–128. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4

Marsh, H. W., Pekrun, R., Murayama, K., Arens, A. K., Parker, P. D., Guo, J., et al. (2018). An Integrated Model of Academic Self-Concept Development: Academic Self-Concept, Grades, Test Scores, and Tracking over 6 Years. Dev. Psychol., 54, 263–280. doi:10.1037/dev0000393

Marsh, H. W., Balla, J. R., and McDonald, R. P. (1988). Goodness-of-fit Indexes in Confirmatory Factor Analysis: The Effect of Sample Size. Psychol. Bull. 103 (3), 391–410. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.391

Meade, A. W., Johnson, E. C., and Braddy, P. W. (2008). Power and Sensitivity of Alternative Fit Indices in Tests of Measurement Invariance. J. Appl. Psychol. 93 (3), 568–592. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.568

Moè, A., and Katz, I. (2020). Emotion Regulation and Need Satisfaction Shape a Motivating Teaching Style. Teach. Teach., 1–18. doi:10.1080/13540602.2020.1777960

Nieskens, B. (2006). “Ergebnisse der Gesundheitsforschung für Lehrkräfte und Schulen,” in Lehrergesundheit - Baustein einer guten gesunden Schule. Editors L. Schumacher, B. Sieland, B. Nieskens, and H. Brauer (Hamburg: DAK Schriftenreihe), 19–50.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: a Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88 (5), 879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Paine, J. B., and Bachrach, D. G. (2000). Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: A Critical Review of the Theoretical and Empirical Literature and Suggestions for Future Research. J. Management 26 (3), 513–563. doi:10.1177/014920630002600307

Rothland, M. (2013). “Beruf: Lehrer/Lehrerin - Arbeitsplatz: Schule Charakteristika der Arbeitstätigkeit und Bedingungen der Berufssituation,” in Belastung und Beanspruchung im Lehrerberuf. Editor M. Rothland (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden), 21–39. doi:10.1007/978-3-531-18990-1_2

Rothmann, S., and Fouché, E. (2018). “School Principal Support, and Teachers' Work Engagement and Intention to Leave: The Role of Psychological Need Satisfaction,” in Psychology of Retention: Theory, Research and Practice. Editors M. Coetzee, I. L. Potgieter, and N. Ferreira (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland), 137–156. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-98920-4_7

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 55 (1), 68–78. Retrieved from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11392867. doi:10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation from a Self-Determination Theory Perspective: Definitions, Theory, Practices, and Future Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 61 (April), 101860. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Sarason, B. R., Shearin, E. N., Pierce, G. R., and Sarason, I. G. (1987). Interrelations of Social Support Measures: Theoretical and Practical Implications. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 52 (4), 813–832. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.4.813

Schaarschmidt, U., and Fischer, A. W. (2001). Bewältigungsmuster im Beruf: Persönlichkeitsunterschiede in der Auseinandersetzung mit der Arbeitsbelastung. Goettingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

Schratz, M., Wiesner, C., Kemethofer, D., George, A. C., Rauscher, E., Krenn, S., et al. (2016). Schulleitung im Wandel: Anforderungen an eine ergebnisorientierte Führungskultur. In Nationaler Bildungsbericht Österreich 2015. 2. Fokussierte Analysen bildungspolitischer Schwerpunktthemen. Editors M. Brunoforth, F. Eder, K. Krainer, C. Schreiner, A. Seel, and C. Seel. (Graz: Leykam), pp. 221–262. doi:10.17888/nbb2015-2-6

Schulz, U., and Schwarzer, R. (2003). Soziale Unterstützung bei der Krankheitsbewältigung: Die Berliner Social Support Skalen (BSSS). Diagnostica 49 (2), 73–82. doi:10.1026//0012-1924.49.2.73

Schwarzer, R., Knoll, N., and Rieckmann, N. (2010). “Social Support,” in Health Psychology. Editors J. W. Kaptein, and J. Weinmann. 2nd ed. (Oxford: Blackwell), 283–293.

Sieland, B. (2006). “Veränderungspotenziale und Veränderungshindernisse am Beispiel der Gesundheitsförderung im Schulkollegium,” in Lehrergesundheit - Baustein einer guten gesunden Schule. Editors L. Schumacher, B. Sieland, B. Nieskens, and H. Brauer (Hamburg: DAK Schriftenreihe), 75–110.

Skaalvik, E. M., and Skaalvik, S. (2018). Job Demands and Job Resources as Predictors of Teacher Motivation and Well-Being. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 21 (5), 1251–1275. doi:10.1007/s11218-018-9464-8

Stenling, A., and Tafvelin, S. (2014). Transformational Leadership and Well-Being in Sports: The Mediating Role of Need Satisfaction. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 26 (2), 182–196. doi:10.1080/10413200.2013.819392

Taşçı, G., and Titrek, O. (2019). Evaluation of Lifelong Learning Centers in Higher Education: A Sustainable Leadership Perspective. Sustainability 12 (22), 22. doi:10.3390/su12010022

Titrek, O., and Celik, Ö. (2011). Relations between Self-Awareness and Transformational Leadership Skills of School Managers. New Educ. Rev. 23 (1), 175–188.

Trautwein, U. (2007). The Homework-Achievement Relation Reconsidered: Differentiating Homework Time, Homework Frequency, and Homework Effort. Learn. Instruction 17 (3), 372–388. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.02.009

Uchino, B. N. (2009). Understanding the Links between Social Support and Physical Health: A Life-Span Perspective with Emphasis on the Separability of Perceived and Received Support. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 4 (3), 236–255. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01122.x

Wang, X.-H., Howell, J. M., and Howell, J. M. (2012). A Multilevel Study of Transformational Leadership, Identification, and Follower Outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 23 (5), 775–790. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.02.001

Wang, X. H., Howell, J. M., and Howell, J. M. (2010). Exploring the Dual-Level Effects of Transformational Leadership on Followers. J. Appl. Psychol. 95 (6), 1134–1144. doi:10.1037/a0020754

Windlinger, R., Warwas, J., and Hostettler, U. (2019). Dual Effects of Transformational Leadership on Teacher Efficacy in Close and Distant Leadership Situations. Sch. Leadersh. Management 40 (0), 64–87. doi:10.1080/13632434.2019.1585339

Yammarino, F. J., and Bass, B. M. (1990). Transformational Leadership and Multiple Levels of Analysis. Hum. Relations 43 (10), 975–995. doi:10.1177/001872679004301003

Yu, H., Leithwood, K., and Jantzi, D. (2002). The Effects of Transformational Leadership on Teachers' Commitment to Change in Hong Kong. J. Educ. Admin 40 (4), 368–389. doi:10.1108/09578230210433436

Keywords: transformational leadership, psychological need satisfaction, social support, school principals, teachers

Citation: Schoch S, Keller R, Buff A, Maas J, Rackow P, Scholz U, Schüler J and Wegner M (2021) Dual-Focused Transformational Leadership, Teachers’ Satisfaction of the Need for Relatedness, and the Mediating Role of Social Support. Front. Educ. 6:643196. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.643196

Received: 04 January 2021; Accepted: 01 November 2021;

Published: 25 November 2021.

Edited by:

Osman Titrek, Sakarya University, TurkeyReviewed by:

Timothy Mark O’Leary, University of Melbourne, AustraliaCopyright © 2021 Schoch, Keller, Buff, Maas, Rackow, Scholz, Schüler and Wegner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Simone Schoch, c2ltb25lLnNjaG9jaEBwaHpoLmNo

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.