95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

Front. Educ. , 26 March 2021

Sec. Leadership in Education

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.642861

This article is part of the Research Topic Education Leadership and the COVID-19 Crisis View all 21 articles

School leadership during the pandemic serves as the contextual backdrop for this conceptual article. Specifically, we believe the preparation of today’s school leaders must be re-examined to consider the inclusion of frameworks that consider not only how principals might navigate extreme crises but also how they look after themselves and their wellbeing in ways that may curb the chronic stress that often leads to professional burnout. In this article, we tie together three bodies of literature – crisis management, leadership in turbulence, and self-care – and introduce a conceptual framework that may help us reconsider the preparation of today’s school leader. These bodies of literature, while not yet broadly studied in education, are key to our understanding of how school leaders can successfully practice their new day-to-day practices after experiencing turmoil under the COVID-19 pandemic.

This generation of school leaders has been forced to confront a number of significant crises. For example, over the last two decades, school leaders have been called to navigate the tragic circumstances surrounding school shootings (e.g., Sandy Hook, Parkland, and Santa Fe), the devastating effects of hurricanes (e.g., Katrina, Harvey, and Sandy), and the general upheaval caused by societal turmoil (e.g., teacher walkouts, racial injustices, and school closures). Yet, because of the severity and nuance of these crises, leaders might benefit from specialized preparation to traverse the sundry conditions associated with leading a school and school community during a pandemic. Nevertheless, during the 2020 spring break, district and school leaders received word that their schools would not physically reopen, as local and state governmental agencies suggested schools should transition to online platforms to reduce the rapid spread of the COVID-19 virus.

As schools were asked to close, principals were tasked with serving a diverse range of roles such as chief communicator to school communities, provider of technology, launcher of an online learning platform, logistics manager for food distribution, tracer of the virus, and emotional support for anxious faculty, students, and caregivers. The abrupt interruption of school as “usual” quickly shifted to the “new normal,” where the stressors associated with school leadership increased dramatically. This is particularly significant, as even before the pandemic, scholars had drawn attention to the rising number of principals leaving the profession due to professional burnout attributed to increasingly demanding working conditions (Darmody and Smyth, 2016; Wang et al., 2018; Carpenter and Poerschke, 2020).

School leadership during the pandemic serves as the contextual backdrop for this conceptual article. Specifically, we believe the preparation of today’s school leaders might benefit from the inclusion of frameworks that consider how principals might navigate extreme crises and how they look after themselves and their wellbeing in ways that may curb the chronic stress that often leads to professional burnout. In the following sections, we tie together three bodies of literature – crisis management, leadership in turbulence, and self-care – and introduce a conceptual framework that may help us reconsider the orientation of today’s school leader to address unexpected and threatening events. While not yet broadly studied in education, these bodies of literature are critical to our understanding of how school leaders can successfully practice their new day-to-day practices after experiencing turmoil under the COVID-19 pandemic.

The purpose of crisis management is to design strategies that help organizations return to normal after a crisis or a risky, unsafe, unexpected event defined by its need for ongoing attention. Often, especially in business, crisis management is studied using cases where a mishap has occurred within or because of the organization (e.g., Coldwell et al., 2012; Jacques, 2012). However, in public services, such as in politics or education, crises regularly include external events that require an immediate response with a plan designed to address a threat and restore organizations and communities (e.g., Cohen et al., 2017). While crisis management, and in turn crisis leadership, might appear to provide an opportunity to prompt reform, the overall purpose is to return to normal rather than to promote change, which poses a challenge when attempting to transition a crisis response into sustained transformation (see Boin and ‘t Hart, 2003). Because crisis management is studied as a reaction to a disastrous internal event, this literature is connected to risk management and risk assessment. This connection explains the importance assigned to discussions about how to train leaders and staff to avoid organizational crises and how to reduce and evaluate risk once it occurs (McConnell and Drennan, 2006; Muffet-Willett and Kruse, 2009). Common crisis management strategies include goal development and environment analysis, strategy development and evaluation, and strategy implementation and control (Burnett, 1998; Jin et al., 2017). Crisis management research has been critiqued as overly focused on processes (i.e., operations and finance), so scholars have expanded the study of crises to the role of the leader (Jacques, 2012).

The concept of crisis leadership has stemmed from crisis management research. Perhaps, the most prominent role of a leader during a crisis is to claim responsibility for communication. A leader is responsible for communication at critical moments, particularly early in the crisis or pre-crisis, sometimes at the height of the crisis, and when transitioning out of the crisis (Ulmer, 2001; Demiroz and Kapucu, 2012; Jin et al., 2017). Due to the extreme nature of crises, leaders need to communicate with the community and stakeholders proactively and prepare to engage with media (Lerbinger, 1997; Jin et al., 2017). A leader should portray a singular, cohesive message to prevent confusion, demonstrate involvement, and openly invite constant feedback from community members and stakeholders within the sensitive context (Lucero et al., 2009; Boin et al., 2010). Communication is not the only responsibility of leaders during a crisis. Muffet-Willett and Kruse (2009) explain that leaders who are effective in routine, day-to-day situations are not necessarily successful in a crisis. In fact, due to the nuance of unexpected and risky events, scholars and practitioners question how to train leaders for these unsafe and unfamiliar circumstances. Leaders in a crisis must make decisions in an unknown and complex environment containing possible severe threats while under increased stress and scrutiny (Muffet-Willett and Kruse, 2009). Boin et al. (2005) identified five critical tasks of crisis leadership: sensemaking to diagnose the situation, decision making for a strategy, coordination of implementation, meaning-making to motivate others to move beyond the situation, accounting giving to achieve closure by taking responsibility and learning from response efforts. Further, scholars have emphasized the importance of values and ethics as the foundation for how leaders engage others during a crisis (see Seeger and Ulmer, 2003; Bauman, 2011; Ulmer, 2012). Overall, leaders must address safety, psychological stress, a plan for stability as well as restoration, and work laterally with the community and other organizations (e.g., Marcus et al., 2006; Demiroz and Kapucu, 2012; Dückers et al., 2017).

Much of the crisis leadership literature, whether in business, communication, or public administration, focuses on responding to a crisis. Because of this focus, many scholars connect actions to outcomes that signal a movement toward resolve. For example, in business, strategies are related to a company’s reputation or share prices (Coldwell et al., 2012; Varma, 2020). In communication, the purpose, source, extent, and dissemination of information are related to the preparedness to manage a crisis (Neely, 2014; Houston et al., 2015; Jin et al., 2017). While communication is essential during a crisis, leaders who regularly practice open, two-way communication to build relationships, transparency, and decision-making capability with an ethical orientation are more prepared to navigate threats and unfamiliar circumstances (O’Keefe, 1999; Fairbanks et al., 2007; Cohen et al., 2017). Communication is a central leadership practice that transcends pre- and post-crisis. However, communication from formal leaders or a within-organization strategy is not enough to restore communities affected by a crisis.

Communities must develop resilience when faced with potentially harmful circumstances. “Community resilience denotes a community’s ability to lead itself in order to overcome changes and crises” (Cohen et al., 2017, p. 119). Along with the expansion of leadership as an inclusive interest, community resilience also consists of collective efficacy, cohesion, place attachment, infrastructure, and resources (Cutter et al., 2008; Ungar, 2011; Cohen et al., 2013, 2017). A community’s satisfaction with its public administration has been found to influence resilience (Cohen et al., 2017). Yet, this perception of confidence through effective communication may not completely address the challenges that confront community members most devastated by a crisis. Community members most affected by traumatic events may not have the ability to recover on their own (Dückers et al., 2017). Therefore, an explicit focus on the care of these individuals is necessary for restoration.

Values, ethics, and spirituality help explain leaders’ intentions behind how they resolve a crisis (Pruzan, 2008; Bauman, 2011; Crumpton, 2011). In best practice, a leader uses shared values to create a common vision and virtue to guide decisions. Further, spiritual leaders respect others’ values, have concern for others, and utilize listening, introspection, and reflection (Reave, 2005). More specifically, Bauman (2011) argues for the “ethic of care” to acknowledge harm, apologize, and express emotion for those affected, and act to make amends. While not every crisis is caused by a business or organization, the ethic of care still applies to external events. It deliberately focuses on reaching the individuals impacted by the circumstances.

This deliberate attention is also found in the overlap of crisis leadership and psychosocial needs. Dückers et al. (2017) argue for leaders to meet psychosocial needs within plan-do-study-act cycles of improvement while progressing through the stages of crisis management. They have identified several characteristics of psychosocial supports such as assessing needs and problems, considering risk and protective factors, utilizing and strengthening existing capacities, providing information and basic aid, promoting a sense of safety, calm, efficacy, connectedness to others and hope, positive social acknowledgment of experiences, evaluation of supports, and implementing lessons to improve continually. This overlapping approach allows leaders to build a community of supports to surround individuals who may not recover from a crisis on their own.

Crisis leadership, as a theoretical and research concept, has not been studied as extensively in education. Many education scholars discuss “crisis” and “leadership” in terms of schools struggling, or a crisis, to recruit, train, and retain effective leaders (e.g., Malone and Caddell, 2000; Rhodes and Brundrett, 2005). Fewer scholars have used crisis leadership to explain how educational leaders address an unforeseen and threatening event requiring ongoing attention. For example, Smith and Riley (2012) extend traditional crisis management theory, defined as two-way communication, to cycle through the steps of detection, preparedness, resolution, recovery, and learning, to include key attributes of crisis leadership in education. They categorize these critical attributes as communication skills, procedural intelligence, decisive decision making, creative/lateral thinking, synthesizing skills, empathy and respect, intuition, flexibility, and optimism/tenacity. Like scholars outside of education, they argue that the main challenge for effective leadership during a crisis is preparing and training leaders for the unknown and harmful circumstances (Smith and Riley, 2012). Similar leadership attributes are discussed by Sutherland (2017); however, he emphasizes the need for trust to build collaboration within the community affected by the crisis. Finally, Mutch (2015) identified three sets of factors influencing leaders in a crisis, dispositional, relational, and situational, which was used to analyze how principals handled an emergency, such as a major earthquake.

Natural disasters have been used within education to understand how leaders respond to emergencies (e.g., Lee et al., 2008; Mutch, 2015). Scholars have also studied leaders’ responses to more indirect or silent unfamiliar and pressing circumstances, such as homelessness, to describe moral, resourceful, and lateral decision making (see Shields and Warke, 2010). Most explicitly, the U.S. Department of Education (2007) has offered traditional crisis management guidance in planning documents that outline action steps for each stage of prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery. This national crisis planning is designed to direct schools facing a crisis such as natural disasters, terrorism, and pandemics. Since the start of COVID, the Center for Disease Control, states, and school districts across the United States have also created similar crisis management guidance specific to the pandemic.

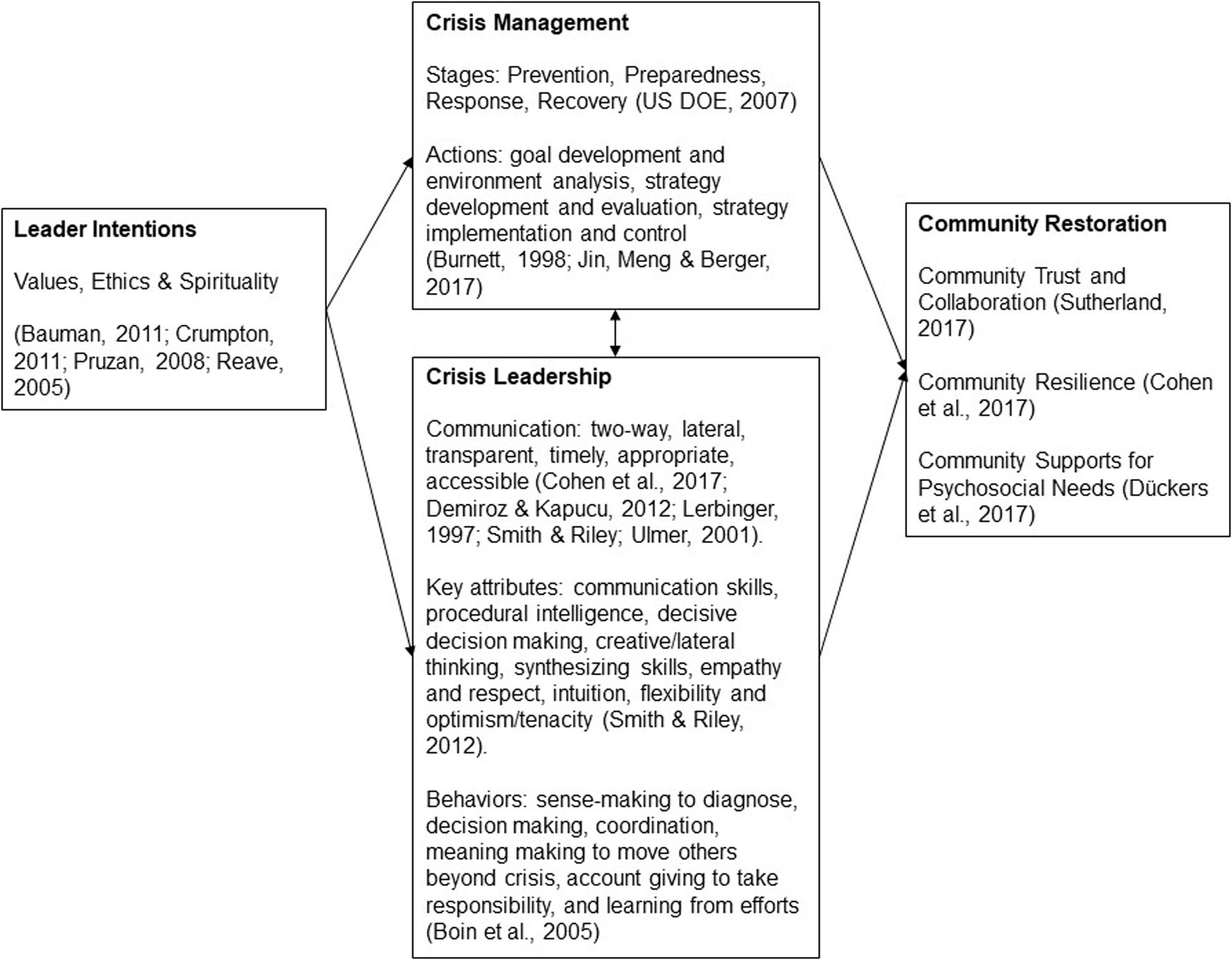

During the COVID-19 pandemic, scholars have quickly published conceptual and informative articles to guide educational leaders, policymakers, and other researchers on navigating the threats specific to this context. In this case, scholars have discussed tensions between school autonomy and levels of government (Eacott et al., 2020), the roles of leaders and teachers (Kidson et al., 2020; Pollock, 2020), emergency response plans (Moyi, 2020), costs for online learning (Iyiomo, 2020), technology infrastructure (Ahmed et al., 2020), inequities for special education students (Nelson and Murakami, 2020), and the value of communal caring (Stasel, 2020). These topics are examples of issues or tasks germane to crisis leadership that has manifested during COVID-19. Understanding crisis leadership theory can help school leaders, policymakers, and researchers more purposefully comprehend leader intentions and pinpoint management stages and strategies as well as leadership responses to reach the outcome of community restoration (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Synthesis of intentions, characteristics and purpose of crisis management/leadership across disciplines as a framework for school leaders.

Turbulence is a term taken from air travel that describes flight conditions caused by changes in air pressure. Turbulence can produce anxiety and fear in passengers, especially when the changes are particularly extreme. All leadership experience conflict, change, and competing priorities – turbulence (Putnam, 1991). Milton Friedman, Nobel Prize-winning economist, wrote, “Only a crisis – actual or perceived – produces real change” (1962, p. ix).

Turbulence constrains and sometimes catalyzes organizational behavior and performance. Organizational environments can be decomposed into three main categories: munificence, complexity, and dynamism. Munificence describes the economic resources a private or public organization has at its disposal. Complexity refers to the heterogeneity or homogeneity of the external conditions that affect an organization. Dynamism is the change over time in munificence and complexity. These three elements influence how an organization will experience turbulence and determine how extreme the turbulence might be (Boyne and Meier, 2009).

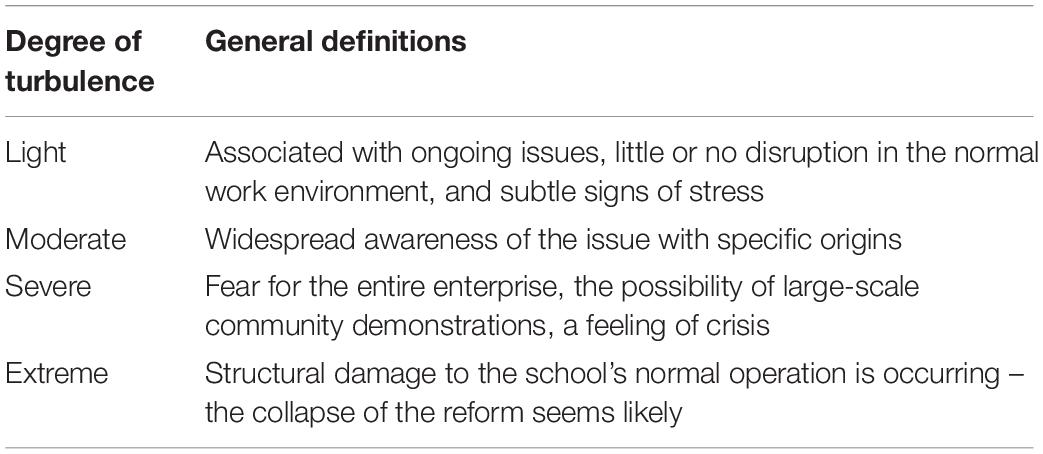

Steven Gross has developed and expanded turbulence theory (Gross, 1998, 2002, 2006, 2020; Gross and Shapiro, 2004; Shapiro and Gross, 2013) over the last three decades. Borrowing from air travel, Gross describes four levels of turbulence. Light turbulence is common and can be handled easily. Causes of light turbulence could be regional isolation or minor communication limitations. Moderate turbulence refers to issues that might be more widespread such as the rapid expansion of the organization. Moderate differs from light turbulence in that moderate turbulence is not part of normal operations and most likely has everyone’s attention in the organization; however, with focused effort, moderate turbulence is manageable. Severe turbulence threatens the existence of initiatives. An example of severe turbulence might be a conflict in the values of an organization. In severe turbulence, typical leadership or administrative practices seem insufficient, and new approaches are needed. Extreme turbulence threatens the existence of the entire organization. This typically occurs when cascading pressures lead to the collapse of the organization. Multiple internal and external turbulence elements that might not be explicitly identifiable can lead to organizational collapse (see Table 1).

Table 1. Types of turbulence (based on Gross, 1998, 2002, 2020; Gross and Shapiro, 2004).

Literature across public and private sectors demonstrates a perception that turbulence is increasing (Putnam, 1991; Wheatley, 2002; Marta et al., 2005; Salicru, 2018; Taysum and Arar, 2018). As organizations increasingly deal with turbulence, researchers are identifying increasing overlap between spirituality and work (Wheatley, 2002), the use of storytelling to manage the associated challenges (Salicru, 2018), and the effects of planning (Marta et al., 2005). Due to turbulence, leaders respond to questions that have historically been answered through religious traditions: How do we find meaning in our lives? How do we cope with uncertainty? Why are we doing this work? How can we act with courage and integrity? What are our values (Wheatley, 2002)?

As leaders and members of organizations sense increased complexity and adaptive challenges (Heifetz, 1994), they are also attempting to make sense of turbulence through storytelling. Humans connect with others through storytelling and, therefore, find meaning and stability through stories (Salicru, 2018). Both storytelling and looking for deeper meaning through spirituality are ways of coping with increasing turbulence.

Regardless of organizational context, planning is an additional way to manage turbulence. Plans require people to identify elements of their organizational environment and context to leverage opportunities for improvement. Additionally, plans provide a framework for responding to adaptive challenges, and increasing turbulence typically leads to improved planning activity. However, severe and extreme turbulence can render plans useless if external changes alter the environment to the extent that the plans are irrelevant. The composition of a group developing plans becomes particularly relevant during times of turbulence. Heterogeneous groups develop higher-quality plans than homogenous groups when multiple changes were introduced. However, homogenous groups produced higher-quality plans when no change occurred. “Thus, diversity apparently helps groups cope with change, particularly in terms of quality, when plans must be developed for addressing the kind of novel, ill-defined problems” (Marta et al., 2005, p. 111). These collaborative and diverse groups used for decision-making are essential to create and to continue to adapt plans to respond to turbulence.

Schools’ responses to turbulence are similar to those of organizations in other sectors. Turbulence can be caused by external pressures, conflicting values, disjointed communities, poor working conditions, and ineffective communication (Gross, 1998). Turbulence occurs in micro-level issues such as day-to-day policies, procedures, and experiences, as well as macro-level issues such as externally imposed organizational changes (Myers, 2014). These conditions rarely occur in isolation and could result in a cascading effect that increases the sense of turbulence (Gross, 2006, 2020; Shapiro and Gross, 2013). According to turbulence theory, positionality, stability, and the cascading nature of crises influence an organization’s and an individual’s experience with turbulence (Gross, 2006). First, positionality refers to where a person sits, or their specific role or groups (i.e., teachers, principals, etc.), within the turbulence (Norberg and Gross, 2019). Second, cascading is defined as the ways in which multiple situations compound to determine their impact or severity (Norberg and Gross, 2019). Finally, stability indicates the organization’s sensitivity to turbulence based on the fragility or strength of its foundation (Norberg and Gross, 2019). For example, when these three drivers interact in a school, a principal will possibly view external pressures or communication differently than a teacher would. Additionally, the internal stability of the organization would increase or decrease the effect of cascading crises that create severe and extreme turbulence.

While turbulence is experienced differently based on position and micro and macro-level issues, research generally demonstrates that turbulence has a negative effect on performance in schools (Boyne and Meier, 2009; Beabout, 2012; Gross, 2020). In fact, turbulence’s negative effect on performance is compounded by internal organizational change. Particularly in severe or extreme turbulence cases, significant internal organizational changes compound the adverse effects of turbulence. Leaders can mitigate those negative effects of turbulence in the external environment by maintaining internal structural stability. Additionally, schools “may be able to dampen the extent of volatility through creating networks of environmental actors in other organizations, especially those on which they are dependent for resources” (Boyne and Meier, 2009, p. 820). These networks can help schools navigate turbulence while maintaining some internal stability. Additionally, internal stability and the ability to survive and even thrive through turbulence is dependent on the grassroots participation of teachers and staff (Taysum and Arar, 2018).

Given the increasingly complex environments for schools, turbulence is inevitable for school leaders (Fullan, 2009). The roles of the people experiencing the turbulence will significantly influence their responses (Gross, 2006; Myers, 2014). The cascading effect of multiple elements of turbulence requires significant leadership acumen and capacity. Some researchers have suggested that the school leader must consider when to intentionally elevate the level of turbulence within an organization to create urgency and accelerate change (Shapiro and Gross, 2013; Myers, 2014). This seems contrary to the notion that internal stability should be maintained to survive turbulence; however, the degree of turbulence matters. School leaders who can use light, moderate, or even more severe turbulence to help others see a need for change or catalyze grassroots support can be successful. Accepting some level of turbulence does not mean that leadership should de-stabilize a school. In fact, the schools’ relative instability could enhance a leaders’ ability to be flexible in ways that allow them to turn turbulence into opportunities (Shapiro and Gross, 2013; Myers, 2014).

School leaders who can build a positive frame around turbulence are likely to be more effective. A principal who believes that risk-taking creates a certain level of turbulence is more likely to build confidence among teachers, administrators, and the school community (Myers, 2014). Turbulence leads to perturbance. When school communities begin to experience turbulence and come together to make decisions, they begin to ask what comes next. This questioning of what is next is perturbance. Leaders interested in improving schools should foster perturbance while minimizing the harmful effects of severe and extreme turbulence (Beabout, 2012).

Similarly, flux can be an opportunity to move an organization forward (Gross, 1998, 2006), particularly if leaders effectively network with key people outside of their schools to better understand the turbulence’s intensity and source. Knowing community leaders, state and local policymakers, and others who might understand contextual factors has a significantly positive effect on performance (Goerdel, 2006). Using networks to get early warnings through environmental scanning about shifts, particularly in munificence and complexity, could be a complementary strategy to help schools navigate turbulence (Boyne and Meier, 2009).

Mentoring, particularly mentoring in ethical leadership, can help leaders bring turbulence into moderate ranges where the effects can be more manageable. When mentors help leaders use a range of ethical lenses (e.g., ethic of justice, ethic of care, ethic of critique, or ethic of profession), leaders can more effectively manage turbulence (Gross and Shapiro, 2004). This type of mentoring and these ethical considerations identified in Standard Two of the Professional Standards for Educational Leaders (National Policy Board for Educational Administration, 2015) ground leaders in ways that stabilize schools even in times of crisis.

Turbulence also affects students. Elevating student voices to participate in response to turbulence builds efficacy and can improve school conditions. Conditions can improve in at least three ways. First, students can provide fresh ways of seeing issues because of differences in their positionality (Shapiro and Gross, 2013). Second, based on cases from the United States and Australia, student voice can increase tension and focus on pressing issues. Third, increasing agency and collective student efficacy can reduce organizational turbulence and individual turbulence during adolescence. Turbulence can “be a force for positive change and needed energy to launch an emerging adult into the wider world beyond home and school” (Mitra and Gross, 2009, p. 538). The use of student voice, networks outside of schools, and mentoring in ethical leadership can transform turbulence into change.

Overall, Gross(2020, p. 47) recommends a five-step process for leading through turbulence. First, leaders should reflect on the causes of turbulence. Second, as a part of their reflection, they should determine the role of the three drivers of turbulence – positionality, cascading crises, and stability. Third, identify the general level of turbulence. Fourth, decide whether to escalate or de-escalate the turbulence. Fifth, organize and effectively communicate constructive advice that responds to turbulence. If leaders do this, they are more likely to develop an effective systemic response to turbulence.

While the self-care industry continues to grow at an astronomical pace, school leaders’ self-care is often reserved for private conversation, not a subject to be conflated with job expectations or professional effectiveness. The normed silence on topics such as self-care and wellbeing in the workplace is particularly problematic for school leaders. Today’s principals are one of our nation’s most stressed and burned-out cohorts of professionals, leaving the field at alarming rates (Yan, 2020). As highlighted by Ray et al. (2020), school leaders, in place of self-care, often embrace the role of the caretaker for others, choosing to “adopt a disposition of self-sacrifice” which may provide short term benefit to those they serve but is not a sustainable professional disposition (p. 435).

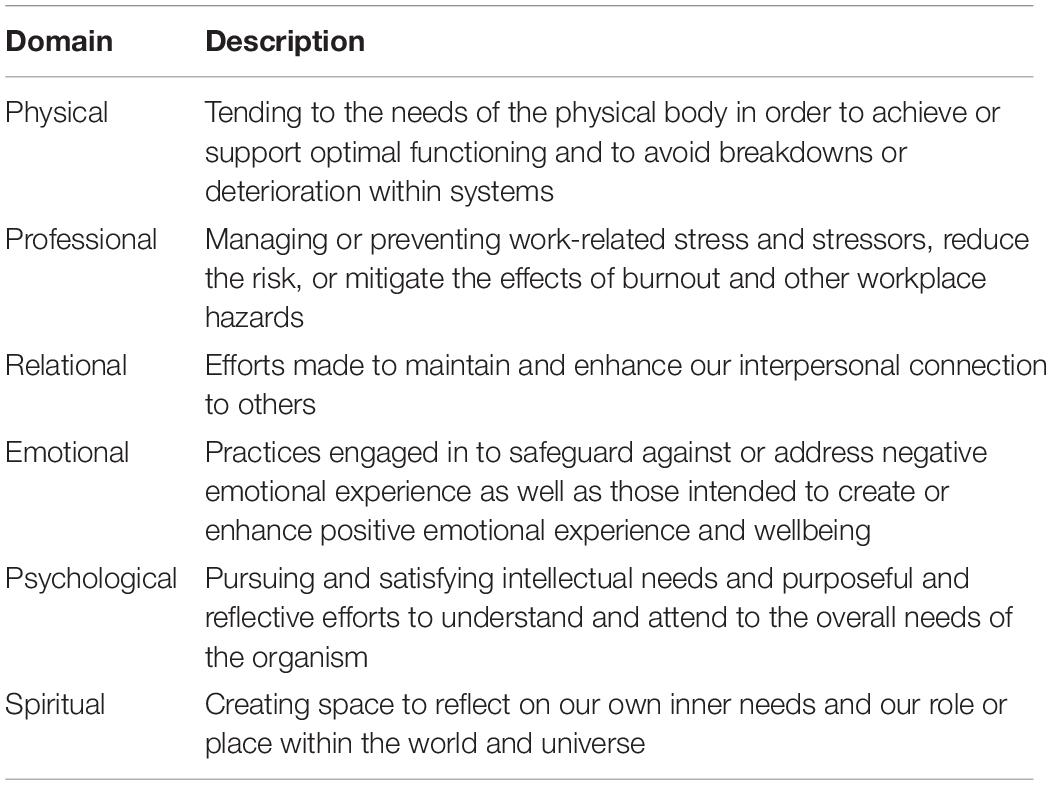

While the field of education and educational leadership is woefully behind in its empirical examination of the importance of self-care and its practitioners, the areas of nursing and social work have made steady progress. Butler et al. (2019) outline two specific aims of self-care: (a) to “guard against, cope with, or reduce stress and related adverse experiences” and (b) to “maintain or enhance wellbeing and overall functioning” (pp. 107, 108). The authors then propose six self-care domains largely founded upon Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs (see Table 2). By presenting a broad range of domains, the authors acknowledge that professional life is inhabited across multiple contexts and embodied spaces (e.g., home, work, social, etc.). Butler et al. (2019) highlight the interplay amongst each domain while identifying the conceptual link that ties each frame together as “mindful attention” and “intentional action” to self-care needs and activities in both work and private settings.

Table 2. Six domains of self-care (Butler et al., 2019).

The nursing and social work fields have led the empirical and theoretical examination of self-care. Each, which houses many jobs often labeled as “helping professions” (Skovholt and Trotter-Mathison, 2014), have long recognized the need to address the burnout-related effects of the accumulated stressors associated with working in high-intensity contexts. As a result, researchers in both fields have launched many studies focused on self-care interventions to alleviate their clinical practitioners’ burnout and turnover.

In nursing, up to 37% of nurses were identified as having experienced burnout (McHugh et al., 2011). Much like the social work field, nurses are often exposed to workplace-specific stressors for long periods, which ultimately affects wellbeing and reduces commitment to task performance (Akkoç et al., 2020). In terms of self-care, the nursing field has identified how deliberate attentiveness to a broad array of self-care domains such as body, mind, emotions, and spirit are empirically sound ways to address stress-induced issues associated with clinical nursing.

Social work is also grappling with the consequences associated with the increasing burnout of their professionals. For example, social workers are often negatively affected by workload, rewards/wages, resources, time limitations, etc. that often influence a social worker’s perceived job satisfaction (Wilson, 2016). Additionally, social workers are more likely than other professions to be impacted by the complexities associated with compassion fatigue, secondary trauma, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Wagaman et al., 2015; Wilson, 2016).

The increasing turnover of school leaders is of growing concern to school districts and educational leadership scholars. This concern is with good reason, as principals, second only to teachers, are a primary factor in students’ academic success (Young et al., 2007). Goldring and Taie (2018) and the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) estimate that school leaders’ turnover rates are nearing 18% nationally. In light of this number, many scholars have been working to determine precisely why principals leave (Fuller and Orr, 2008; DeAngelis and White, 2011; Snodgrass Rangel, 2018; Grissom and Bartanen, 2019), and a growing number of scholars have begun to examine how self-care specific interventions that may help prevent principal turnover (Mahfouz,2018a,b; Carpenter, 2020; Liu, 2020; Ray et al., 2020). To date, no known study has directly incorporated self-care theory into its examination of possible interventions for school leaders. The Ray et al. (2020) comes closest, as its purpose was to examine how principals were able to attend to self-care practices amidst the array of job-embedded demands of today’s school leader.

The Consortium for Policy Research in Education (CPRE) recently conducted a study to examine school leaders’ responses to the critical incidents induced by COVID-19 during mid to late March of 2020 (CPRE website). As a part of that study, three scholars (Anderson et al., 2020) examined how school leaders addressed their wellbeing during a time of such immense stress for communities, school leaders, teachers, and students. They found that principals experienced high levels of stress due to the litany of tasks associated with closing down schools, launching online-only instruction, monitoring sickness, delivering food and other school-provided services, and ensuring students could access the Internet. Principals also had difficulty separating their work from their home life, as working from home suddenly transitioned to living at work (Anderson et al., 2020).

While the Anderson et al. (2020) study highlighted several ways in which principals sought to attend to self-care (exercise, spiritual foundations, and time with family), there was no consensus as to the importance of self-care, nor the ability to prioritize self-care amongst the range of duties associated with leadership during the crisis. Subsequently, it is perhaps time that the field of educational leadership incorporates the scholarly body of work in social work and nursing to launch a more significant number of qualitative and quantitative studies that would seek to determine the role of self-care for school leaders.

The events surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic have magnified the need to frame and study the work of school leaders as navigators of crisis. While school leaders have faced extreme challenges leading up to the pandemic, natural disasters, racial injustice, fights for funding, professional shortages, among others, the broader conceptualizations of the field have understood leadership in terms of guiding academic success rather than recognizing a more prevalent role as caretakers of much larger social and health crises. Through crisis leadership and turbulence theory, we can continue to expand these broader conceptualizations of educational leadership to include a primary focus on the restoration of the profession and the communities served through a movement toward self-care, and in turn, flourishing, the realization of this restoration and care. Table 3 summarizes the goals and characteristics of these bodies of literature to frame how leaders might tackle pressing challenges.

As stated in the introduction, school leaders have faced numerous crises over the last several decades. While the pandemic was undoubtedly the most universal crises faced by school leaders, it will certainly not be the last time a nation and its schools will be forced to respond to an external set of factors requiring dexterity in the face of extreme circumstances. With this in mind, we suggest leadership preparation programs author and implement a three-pronged curricular strand that provides conceptual frameworks necessary for leaders to successfully navigate during stress-specific contexts associated with crisis and turbulence while maintaining their overall health and wellbeing. Further, we argue that educational leadership programs’ standards should move beyond an intense focus on instruction alone and reorient to also value the work of school leaders as caretakers of impending turbulence from either longstanding crises or unexpected, emergency events. Crisis leadership theory describes how leaders can reduce risk, navigate planning to return to normal, and reach community restoration. Turbulence theory provides a framework for transforming these circumstances into change and improvement for our schools and communities. Self-care literature explicates what needs are associated with wellbeing so that we can build a flourishing profession, school, and community. Taken together, leaders can use crisis leadership and turbulence theory to guide their efforts to embed self-care, or more extensively, flourishing, as a central purpose of schools. This new focus requires a movement beyond simply learning successful leadership practices but a careful examination of intentionality, or the ethics, values, and spirituality, which guide the “how,” “why,” and “what” of leadership in schools. The leader who can address uncertainty, care for others and restore crises is motivated by her desire to lead for flourishing.

In conclusion, we synthesize four main lessons from these frameworks to apply to how we train and support educational leaders as they navigate crises in schools.

Leaders who maintain open, two-way, transparent, and ethical communication can prevent and reduce threats. While situations and context may change and become unpredictable, encouraging transparent and collaborative approaches to communication creates consistency before, during, and after a crisis. Further, turbulence theory promotes the communicative vehicle of storytelling as way to allow humans to find shared meaning. Through sharing and soliciting the stories of crisis participants, leaders surface the perceptual understandings of actors and highlight narratives that provide stability amid crisis response. Storytelling is also a form of communication that can promote spirituality and a sense of shared ethics, which may promote trust, stability, and shared values for the community.

Leaders need to focus on the collaborative process of defining shared values within their community. These values, guided by ethical frames, can serve as the foundation for the construction of a common vision to guide decision making. By centering community resilience as a focus, stakeholders are empowered to own and lead the restoration of their communities and organizations. Leaders can fortify self-directed communities by addressing the psychological needs and care of others. The use of mentoring to support the use of ethical lenses helps to establish these shared values, resilience, and care.

The nature of crises and turbulence requires leaders to question what is next. The questioning of what is next orients leaders and stakeholders toward the collaborative planning of action steps that may in fact reduce risk and extend into progress toward restoration and positive change. Leaders can analyze select action steps using dispositional, relational, and situational frames as they move through each stage of crisis. Importantly, leaders must focus on building collaborative and diverse groups during the creation and adaption phase of planning, including highly diverse networks of actors and grassroots participation from teachers, staff, student voice, and community stakeholders.

Due to the stressful and extreme circumstances inherit during crisis and turbulence, leaders and the surrounding community should attend to the physical, professional, relational, emotional, and psychological aspects of self-care to avoid burnout and mitigate the adverse effects induced by the chronic stressors associated with threatening and unexpected events. Leaders must normalize the practice of and discussions about wellbeing. Further, leaders should develop interventions for themselves and others that focus on a holistic imagining of wellbeing that includes the various aspects of body, mind, emotional, and spiritual health.

AU took primary responsibility for the final completion of the manuscript. BC organized the project and facilitated the creation of the manuscript’s outline. JE participated in each phase of the manuscript development. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ahmed, N., Bhatnagar, P., and Shahidul, M. (2020). COVID-19 and unconventional leadership strategies to support student learning in South Asia: commentaries from Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. CCEAM 48, 87–93.

Akkoç, İ, Okun, O., and Türe, A. (2020). The effect of role-related stressors on nurses’ burnout syndrome: the mediating role of work-related stress. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care. 1–14 doi: 10.1111/ppc.12581 [Epub ahead of print].

Anderson, E., Hayes, S., and Carpenter, B. (2020). Principal as Caregiver of All: Responding to Needs of Others and Self. CPRE Policy Briefs. Available online at: https://repository.upenn.edu/cpre_policybriefs/92 (accessed November 9, 2020).

Bauman, D. C. (2011). Evaluating ethical approaches to crisis leadership: insights from unintentional harm research. J. Bus. Ethics 98, 281–295. doi: 10.1007/s10551-010-0549-3

Beabout, B. R. (2012). Turbulence, perturbance, and educational change. Complicity Int. J. Complex. Educ. 9, 15–29. doi: 10.29173/cmplct17984

Boin, A., and ‘t Hart, P. (2003). Public leadership in times of crisis: mission impossible? Public Adm. Rev. 63, 544–553. doi: 10.1111/1540-6210.00318

Boin, A., ‘t Hart, P., McConnell, A., and Preston, T. (2010). Leadership style, crisis response and blame management: the case of Hurricane Katrina. Public Adm. 88, 706–723. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01836.x

Boin, A., ‘t Hart, P., Stern, E., and Sundelius, B. (2005). The Politics of Crisis Management: Public Leadership Under Pressure. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511490880

Boyne, G. A., and Meier, K. J. (2009). Environmental turbulence, organizational stability, and public service performance. Adm. Soc. 40, 799–824. doi: 10.1177/0095399708326333

Burnett, J. J. (1998). A strategic approach to managing crisis. Public Relat. Rev. 24, 475–488. doi: 10.1016/S0363-8111(99)80112-X

Butler, L. D., Mercer, K. A., McClain-Meeder, K., Horne, D. M., and Dudley, M. (2019). Six domains of self-care: Attending to the whole person. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 29, 107–124. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2018.1482483

Carpenter, B. W. (2020). The reframing of self-care as altruistic: an interruption of self-denial. UCEA Rev. 61, 1–4.

Carpenter, B. W., and Poerschke, A. (2020). “Leading toward normalcy and wellbeing in a time of extreme stress and crises,” in The School Leadership Survival Guide: What to Do When Things Go Wrong, How to Learn from Mistakes, and Why You Should Prepare for the Worst, eds J. S. Brooks and T. N. Watson (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing), 363.

Cohen, O., Goldberg, A., Lahad, M., and Aharonson-Daniel, L. (2017). Building resilience: the relationship between information provided by municipal authorities during emergency situations and community resilience. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 121, 119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2016.11.008

Cohen, O., Leykin, D., Lahad, M., Goldberg, A., and Aharonson-Daniel, L. (2013). The conjoint community resiliency assessment measure as a baseline for profiling and predicting community resilience for emergencies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 80, 1732–1741. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2012.12.009

Coldwell, D. A. L., Joosub, T., and Papageorgiou, E. (2012). Responsible leadership in organizational crises: an analysis of the effects of public perceptions of selected SA business organizations’ reputations. J. Bus. Ethics 109, 133–144. doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-1110-8

Crumpton, A. D. (2011). An Exploration of Spirituality Within Leadership Studies Literature. Available online at: https://docplayer.net/9390460-An-exploration-of-spirituality-within-leadership-studies-literature.html (accessed December 2020).

Cutter, S. L., Barnes, L., Berry, M., Burton, C., Evans, E., Tate, E., et al. (2008). A place-based model for understanding community resilience to natural disasters. Global Environ. Change 18, 598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.07.013

Darmody, M., and Smyth, E. (2016). Primary school principals’ job satisfaction and occupational stress. Int. J. Educ. Manage. 30, 115–128. doi: 10.1108/IJEM-12-2014-0162

DeAngelis, K. J., and White, B. R. (2011). Principal Turnover in Illinois Public Schools, 2001–2008. Policy Research: IERC 2011-1. Champaign IL: Illinois Education Research Council.

Demiroz, F., and Kapucu, N. (2012). The role of leadership in managing emergencies and disasters. Eur. J. Econ. Polit. Stud. 5, 91–101.

Dückers, M. L., Yzermans, C. J., Jong, W., and Boin, A. (2017). Psychosocial crisis management: the unexplored intersection of crisis leadership and psychosocial support. Risk Hazards Crisis Public Policy 8, 94–112. doi: 10.1002/rhc3.12113

Eacott, S., MacDonald, K., Keddie, A., Blackmore, J., Wilkinson, J., Niesche, R., et al. (2020). COVID-19 and inequities in Australian education–insights on federalism autonomy, and access. CCEAM 48, 6–13.

Fairbanks, J., Plowman, K. D., and Rawlins, B. L. (2007). Transparency in government communication. J. Public Affairs 7, 23–37. doi: 10.1002/pa.245

Fullan, M. (2009). The Challenge of Change: Start School Improvement Now!, 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Fuller, E., and Orr, T. (2008). The Revolving Door of the Principalship. Implications from UCEA. East Lansing, MI: University Council for Educational Administration.

Goerdel, H. T. (2006). Taking initiative: proactive management in networks and program performance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 16, 351–367. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mui051

Goldring, R., and Taie, S. (2018). Principal Attrition and Mobility: Results from the 2016–17 Principal Follow-up Survey (NCES 2018-066) (Technical Report). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Grissom, J. A., and Bartanen, B. (2019). Strategic retention: principal effectiveness and teacher turnover in multiple-measure teacher evaluation systems. Am. Educ. Res. J. 56, 514–555. doi: 10.3102/0002831218797931

Gross, S. J. (1998). Staying Centered: Curriculum Leadership in a Turbulent era. Alexandria, VA: The Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Gross, S. J. (2002). Sustaining change through leadership mentoring at one reforming high school. J. Serv. Educ. 28, 35–56. doi: 10.1080/13674580200200170

Gross, S. J. (2006). Leadership Mentoring: Maintaining School Improvement in Turbulent Times. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Gross, S. J. (2020). Applying Turbulence Theory to Educational Leadership in Challenging Times: A Case-Based Approach. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315171357

Gross, S. J., and Shapiro, J. P. (2004). Using mulitple ethical paradigms and turbulence theory in response to administrative dilemmas. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 32, 47–62.

Houston, J. B., Spialek, M. L., Cox, J., Greenwood, M. M., and First, J. (2015). The centrality of communication and media in fostering community resilience: a framework for assessment and intervention. Am. Behav. Sci. 59, 270–283. doi: 10.1177/0002764214548563

Iyiomo, O. A. (2020). Managing the costs of online teaching in a free secondary education programme during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Nigeria. CCEAM 48, 66–72.

Jacques, T. (2012). Crisis leadership: a view from the executive suite. J. Public Affairs 12, 366–372. doi: 10.1002/pa.1422

Jin, Y., Meng, J., and Berger, B. (2017). The influence of communication leadership qualities on effective crisis preparedness strategy implementation: insights from a global study. Commun. Manage. Rev. 2, 8–29. doi: 10.22522/cmr20170118

Kidson, P., Lipscombe, K., and Tindall-Ford, S. (2020). Co-designing educational policy: professional voice and policy making post-covid. CCEAM 48, 15–22.

Lee, D. E., Parker, G., Ward, M. E., Styron, R. A., and Shelley, K. (2008). Katrina and the schools of Mississippi: an examination of emergency and disaster preparedness. J. Educ. Stud. Placed Risk 13, 318–334. doi: 10.1080/10824660802350458

Lerbinger, O. (1997). The Crisis Manager. Facing Risk and Responsibility. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Liu, L. (2020). Examining the usefulness of mindfulness practices in managing school leader stress during COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Sch. Adm. Res. Dev. 5, 15–20. doi: 10.32674/jsard.v5iS1.2692

Lucero, M., Tan Teng Kwang, A., and Pang, A. (2009). Crisis leadership: when should the CEO step up? Corporate Commun. 14, 234–248. doi: 10.1108/13563280910980032

Mahfouz, J. (2018a). Mindfulness training for school administrators: effects on well-being and leadership. J. Educ. Adm. 56, 602–619. doi: 10.1108/JEA-12-2017-0171

Mahfouz, J. (2018b). Principals and stress: few coping strategies for abundant stressors. Educ. Manage. Adm. Leadersh. 48, 440–458. doi: 10.1177/1741143218817562

Malone, B. G., and Caddell, T. A. (2000). A crisis in leadership: where are tomorrow’s principals? Clear. House 73, 162–164. doi: 10.1080/00098650009600938

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 50, 370–396. doi: 10.1037/h0054346

Marcus, L. J., Dorn, B. C., and Henderson, J. M. (2006). Meta-leadership and national emergency preparedness: a model to build government connectivity. Biosecur. Bioterr. 4, 128–134. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2006.4.128

Marta, S., Leritz, L., and Mumford, M. D. (2005). Leadership skills and the group performance: situational demands, behavioral requirements, and planning. Leadersh. Q. 16, 97–120. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.04.004

McConnell, A., and Drennan, L. (2006). Mission Impossible? Planning and preparing for crisis. J. Conting. Crisis Manage. 14, 59–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5973.2006.00482.x

McHugh, M. D., Kutney-Lee, A., Cimiotti, J. P., Sloane, D. M., and Aiken, L. H. (2011). Nurses’ widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout, and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. Health Affairs 30, 202–210. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0100

Mitra, D. L., and Gross, S. J. (2009). Increasing student voice in high school reform: building partnership, improving outcomes. Educ. Manage. Adm. Leadersh. 37, 522–543. doi: 10.1177/1741143209334577

Moyi, P. (2020). Out of classroom learning: a brief look at Kenya’s COVID-19 education response plan. CCEAM 48, 59–65.

Muffet-Willett, S., and Kruse, S. (2009). Crisis leadership: past research and future directions. J. Bus. Contin. Emerg. Plan. 3, 248–258.

Mutch, C. (2015). The impact of the Canterbury earthquakes on schools and school leaders: educational leaders become crisis managers. J. Educ. Leadersh. Policy Pract. 30:39.

Myers, E. L. (2014). Taming turbulence: an examination of school leadership practice during unstable times. Prof. Educ. 38, 1–16.

National Policy Board for Educational Administration (2015). Professional Standards for Educational Leaders. Reston, VA: National Policy Board for Educational Administration.

Neely, D. (2014). Enhancing community resilience: what emergency management can learn from Vanilla Ice. Austr. J. Emerg. Manage. 29:55.

Nelson, M., and Murakami, E. (2020). Special education students in public high schools during COVID-19 in the USA. CCEAM 48, 109–115.

Norberg, K., and Gross, S. J. (2019). Turbulent ports in a storm: the impact of newly arrived students upon schools in Sweden. Values Ethics Educ. Adm. 14:n1.

O’Keefe, D. (1999). How to handle opposing arguments in persuasive messages: a meta-analytic review of the effects of one-sided and two-sided messages. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 22, 209–249. doi: 10.1080/23808985.1999.11678963

Pollock, K. (2020). School leaders’ work during the COVID-19 pandemic: a two-pronged approach. CCEAM 48, 38–44.

Pruzan, P. (2008). Spiritual-based leadership in business. J. Hum. Values 14, 101–114. doi: 10.1177/097168580801400202

Putnam, H. D. (1991). The Winds of Turbulence: A CEO’s Reflections on Surviving and Thriving on the Cutting Edge of Corporate Crisis. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Ray, J., Pijanowski, J., and Lasater, K. (2020). The self-care practices of school principals. J. Educ. Adm. 58, 435–451. doi: 10.1108/JEA-04-2019-0073

Reave, L. (2005). Spiritual values and practices related to leadership effectiveness. Leadersh. Q. 16, 655–687. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.07.003

Rhodes, C., and Brundrett, M. (2005). Leadership succession in schools: a cause for concern. Manage. Educ. 19, 15–18. doi: 10.1177/089202060501900504

Salicru, S. (2018). Storytelling as a leadership practice for sensemaking to drive change in times of turbulence and high velocity. J. Leadersh. Account. Ethics 15, 130–140. doi: 10.33423/jlae.v15i2.649

Seeger, M. W., and Ulmer, R. R. (2003). Communication and responsible leadership. Manage. Commun. Q. 17, 58–84. doi: 10.1177/0893318903253436

Shapiro, J. P., and Gross, S. J. (2013). Ethical Educational Leadership in Turbulent Times: (Re)solving Moral Dilemmas, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203809310

Shields, C. M., and Warke, A. (2010). The invisible crisis: connecting schools with homeless families. J. Sch. Leadersh. 20, 789–819. doi: 10.1177/105268461002000605

Skovholt, T. M., and Trotter-Mathison, M. (2014). The Resilient Practitioner: Burnout Prevention and Self-care Strategies for Counselors, Therapists, Teachers, and Health Professionals. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203893326

Smith, L., and Riley, D. (2012). School leadership in times of crisis. Sch. Leadersh. Manage. 32, 57–71. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2011.614941

Snodgrass Rangel, V. (2018). A review of the literature on principal turnover. Rev. Educ. Res. 88, 87–124. doi: 10.3102/0034654317743197

Stasel, R. S. (2020). Learning to walk all over again: insights from some international school educators and school leaders in South, Southeast and East Asia during the COVID crisis. CCEAM 48, 95–101.

Sutherland, I. E. (2017). Learning and growing: trust, leadership, and response to crisis. J. Educ. Adm. 55, 2–17. doi: 10.1108/JEA-10-2015-0097

Taysum, A., and Arar, K. (eds) (2018). Turbulence, Empowerment and Marginalisation in International Education Governance Systems. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing. doi: 10.1108/9781787546752

U.S. Department of Education (2007). Practical Information on Crisis Planning: A Guide for Schools and Communities. Available online at: https://www2.ed.gov/admins/lead/safety/emergencyplan/crisisplanning.pdf (accessed December 10, 2020).

Ulmer, R. R. (2001). Effective crisis management through established stakeholder relationships. Manage. Commun. Q. 14, 590–615. doi: 10.1177/0893318901144003

Ulmer, R. R. (2012). Increasing the impact of thought leadership in crisis communication. Manage. Commun. Q. 26, 523–542. doi: 10.1177/0893318912461907

Ungar, M. (2011). Community resilience for youth and families: facilitative physical and social capital in contexts of adversity. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 33, 1742–1748. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.027

Varma, T. M. (2020). Responsible leadership and reputation management during a crisis: The cases of delta and United Airlines. J. Bus. Ethics 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10551-020-04554-w

Wagaman, M. A., Geiger, J. M., Shockley, C., and Segal, E. A. (2015). The role of empathy in burnout, compassion satisfaction, and secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Soc. Work 60, 201–209. doi: 10.1093/sw/swv014

Wang, F., Pollock, K. E., and Hauseman, C. (2018). School principals’ job satisfaction: the effects of work intensification. Can. J. Educ. Adm. Policy 185:73.

Wheatley, M. (2002). Leadership in turbulent times is spiritual. Front. Health Serv. Manage. 18:19–26. doi: 10.1097/01974520-200204000-00003

Wilson, F. (2016). Identifying, preventing, and addressing job burnout and vicarious burnout for social work professionals. J. Evid. Inform. Soc. Work 13, 479–483. doi: 10.1080/23761407.2016.1166856

Yan, R. (2020). The influence of working conditions on principal turnover in K-12 public schools. Educ. Adm. Q. 56, 89–122. doi: 10.1177/0013161X19840391

Keywords: leadership preparation, crisis leadership, turbulence theory, self-care, wellbeing, COVID-19, school leadership

Citation: Urick A, Carpenter BW and Eckert J (2021) Confronting COVID: Crisis Leadership, Turbulence, and Self-Care. Front. Educ. 6:642861. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.642861

Received: 16 December 2020; Accepted: 22 February 2021;

Published: 26 March 2021.

Edited by:

Michelle Diane Young, Loyola Marymount University, United StatesReviewed by:

Diana G Pounder, The University of Utah, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Urick, Carpenter and Eckert. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Angela Urick, QW5nZWxhX1VyaWNrQGJheWxvci5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.