- School of Psychology, University of Worcester, Worcester, United Kingdom

Pre-existing issues regarding the wellbeing and mental health of university students have subsequently been compounded by the global COVID-19 pandemic. Research signals that anxiety and depression symptomology has increased in university students’ following the COVID-19 outbreak, and mental wellbeing has declined. In response to concerns around mental health of students in Higher Education (HE), and to support the transition to remote working during the pandemic, we designed and implemented an 8-week wellbeing program based on positive education frameworks and practices. The online program was delivered in a West Midlands-based university in the United Kingdom, to undergraduate and postgraduate psychology students. The weekly sessions [ran through a virtual learning environment (VLE)] aimed to 1) provide students with a community and an opportunity to feel connected with other students, 2) introduce students to key concepts of wellbeing, and 3) equip students with knowledge and resources that would help sustain/improve their wellbeing. In this paper we outline how positive education, and specifically the “PERMA” wellbeing framework, has inspired the development of this wellbeing program (including the accompanying VLE webpages and sources of support) and future plans for evaluation. We further describe the content and delivery of this program alongside practical implications, lessons learned and important constraints. We situate this discussion alongside consideration of ongoing wellbeing support requirements following the pandemic and issues regarding wider integration of PERMA approaches in university contexts.

Background

Student Mental Health and Wellbeing in HE

There is a narrative in the UK, and worldwide, that the number of university students with mental health issues is increasing; HESA (Higher Education Statistics Agency) data suggests that the number of students declaring a mental health condition on entering Higher Education (HE) has doubled within the last 3-years (Watkins, 2019). It has been estimated that between 12 and 46 percent of university students experience mental health problems (Auerbach et al., 2018; Harrer et al., 2019). Academic studies have indicated that the wellbeing levels of university students are lower than those of the general population (Roberts et al., 1999; Stewart-Brown et al., 2000), that the prevalence of depression and anxiety are heightened during university study as compared to pre-university levels (Andrews and Wilding, 2004), and that anxiety starts to rise within students’ first year of study (Bewick et al., 2010). In a study of students who receive support from university counseling services, it was noted that the severity of symptoms and level of risk to self was almost equivalent to those receiving primary care treatment in the NHS (Connell et al., 2007).

Providing a partial explanation of these rates, a 2018 ONS survey of young people revealed that 18–21 year olds are most likely to experience loneliness, with loneliness also being more prevalent in those that have undergone a life change, such as a transition to university. Subsequently it was noted, in a survey of 103 UK universities, that over 32 percent of respondents reported feeling lonely on a weekly basis (N = 1,615, Dickinson, 2019).

Mental illness is associated with short- and long-term outcomes and, within academic contexts, these include lowered academic engagement, achievement and drop out (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Ishii et al., 2018), as well as higher levels of academic dissatisfaction (Lipson and Eisenberg, 2018). Thereby signaling the importance of promoting and cultivating mental health and wellbeing in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), both for students and for the continued success of HEIs.

In response to this growing concern around mental wellbeing, Universities UK has founded a Mental Wellbeing in Higher Education Group, funded research and initiatives to influence policies for wellbeing in HE (Universities UK, 2015). Student mental health and wellbeing has also been identified as a top priority by the Office for Students (Dandridge, 2018). This demonstrates that there is an increasing focus on wellbeing in HE and a call for initiatives to improve mental health and wellbeing within HE populations.

The Impact of COVID-19

ONS statistics have begun to demonstrate the impact of COVID-19 on mental health and wellbeing in the UK, including elevated levels of self-reported anxiety and loneliness and decreased levels of wellbeing (Office for National Statistics [ONS], 2020). In a 6-week study of mental health and wellbeing during the first UK lockdown (March–May 2020, N = 3077), O’Connor et al. (2020) found evidence that suicide ideation increased during the lockdown period. Although self-reported depression and anxiety did not increase over the lockdown period according to O’Connor et al.’s findings, depression was prevalent in approximately one in four respondents (23.7–26%) in comparison to 5.6% in general population studies, and anxiety was reported in one in five (16.8%–21%) of respondents in comparison to estimates of 5% in the general population. O’Connor et al. also noted that young people (aged 18–29°years) have been particularly affected by the pandemic. Similarly, Dawson and Golijani-Moghaddam, 2020 signaled clinically high levels of mental distress in their adult sample, and Groarke et al. (2020) indicated that having clinical symptoms of depression during the lockdown increased individuals’ levels of loneliness.

These worrying statistics are mirrored in university populations, with Odriozola-González et al. (2020) observing moderate to severe levels of depression in their sample of university staff and students in Spain (N = 2530). Notably, they observed that impact of the pandemic appeared to be more significant and problematic in university students as compared to staff. In the UK, Savage et al. (2020) identified that university students’ mental wellbeing decreased during the first 5 weeks of the first lockdown, and perceived stress levels increased in this same period. Parallel to the argument around mental health and wellbeing in the general population and pre-pandemic, loneliness has been proposed as an underlying contributor toward poor mental health in university students during the pandemic (Hager et al., 2020).

The partial closure of universities, remote delivery of teaching and support services, social isolation of students who are unable to return home, and the level of uncertainty regarding teaching and support are all suggested to have impacted the mental health and wellbeing of university students (Burns et al., 2020). Consequently, there has been a clear demand for universities to develop action plans to address mental health issues that have been caused or exacerbated by COVID-19 (Zhai and Du, 2020).

Whilst the impact of COVID-19 on university students’ academic performance currently remains unclear, research has suggested that the pandemic has negatively impacted on engagement with studies and work performance (Meo et al., 2020). It has further been suggested that the impact of COVID-19, on both academic studies and mental health and wellbeing, could be elevated in university students from low socioeconomic and socially disadvantaged backgrounds (Adnan and Anwar, 2020; tinor et al., 2020).

These findings signal a compounding effect of COVID-19 whereby the issues regarding mental ill health and lower wellbeing in university students have been further exacerbated by the pandemic. Further to this, experiencing crises can lead to enduring long-term effects, including mental illness (Schneiderman et al., 2005), and post-traumatic responses to epidemics have been previously documented (Hugo et al., 2015). This indicates that the effects of the pandemic are likely to be long-lasting with many suggesting that the COVID-19 pandemic could be followed by a mental health crisis, including the United Nations (Kelland, 2020; Savage, 2020). Together, the research evidence presented in this section signposts the urgency of addressing wellbeing in HE contexts, and the space and need for delivering wellbeing initiatives to university students.

Pedagogical Approach

Positive Education Approaches to Enhancing Wellbeing

Positive Psychology is considered “the scientific study of optimal human functioning [which] aims to discover and promote the factors that allow individuals and communities to thrive” (Sheldon et al., 2000, p. 1). Since its conception, there have been thousands of studies examining what these factors are (Rusk and Waters, 2013), with a vast amount of scientific research suggesting that developing individuals’ “strengths of character” and personal attributes can promote wellbeing (Park et al., 2004; Peterson et al., 2007; Harzer, 2016; Goodman et al., 2017).

Positive psychology constructs that have been related to wellbeing include resilience, gratitude, mindfulness, self-compassion and hope (Boniwell, 2012). The practice and cultivation of these traits or competencies are considered avenues to fostering wellbeing, with popular examples including mindfulness techniques, resilience programmes and grateful reflection (Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009; Waters, 2011; Donaldson et al., 2015). For instance, “counting your blessings” can instantly improve one’s mood and its continued practice can lead to sustained wellbeing over time (Seligman et al., 2005; Watkins et al., 2015). Engagement in wellbeing exercises–such as grateful recounting–can become easier with practice, whereby positive memories become more accessible and there is an upward spiral effect of experiencing positive emotion (Fredrickson, 2001; Watkins et al., 2004).

Following from this, “Positive Education” is an approach borne from the field of Positive Psychology that advocates the need to teach character and wellbeing skills in educational contexts, as opposed to focusing solely on student attainment (Seligman et al., 2009). In a “whole-child approach,” Positive Education aims to foster skills for happiness and wellbeing in conjunction with traditional academic skills (Seligman et al., 2009). It is proposed that this can be achieved through the identification and development of character strengths and skills for wellbeing and the cultivation of positive emotions and positive relationships within educational contexts (Durlak et al., 2011; Kern et al., 2015).

Central tenets for implementing Positive Education include that: (a) as a consequence of fostering character strengths, positive emotions, positive relationships, students’ learning and academic success is also enhanced (Kern et al., 2015); and, (b), all of these dimensions can be implicitly and explicitly caught and taught (Hoare et al., 2017). Positive Education approaches have become increasingly popular within school settings (Waters and Loton, 2019), to date, an extensive and growing literature has demonstrated that promoting wellbeing skills in educational contexts can improve academic engagement and achievement (Waters, 2011). Moreover, incorporating a wellbeing focus within education can aid with self-management of mental health, protect against mental ill health, and lead to improvements in life satisfaction, learning and creativity, and social cohesion and citizenship (Kern et al., 2015).

The teaching of personal skills and attributes within educational contexts is clearly not new, and schools have long since adopted formalised approaches such as socio-emotional learning, citizenship, and personal, social, health and economic (PSHE) education initiatives (Kerr, 1999; DfES, 2005; Brown et al., 2011). It is safe to say that the positive education movement is heavily inspired by humanistic approaches to learning and character education initiatives that pre-date positive education (Kristjánsson, 2012).

To date, the application of Positive Education frameworks has largely been confined to primary and secondary education with significantly fewer attempts to embed this particular wellbeing approach within tertiary organisations. (Of course, related approaches such as pastoral care and improving student-educator relationships have received considerable attention (Grant and Thomas, 2006; Hagenauer and Volet, 2014)). Academics have, however, started to set out the opportunities for embedding a focus on character strengths and skills for wellbeing within universities for the purpose of improving wellbeing and enhancing learning (Oades et al., 2011; Morgan and Gulliford, 2017). This includes arguments for integrating wellbeing into the curriculum: “the learning and teaching context should be central to efforts to support and promote student mental wellbeing; this can be achieved without compromising the academic goals of higher education” (Houghton and Anderson, 2017, p. 14).

The application of positive psychology in educational contexts has often involved the delivery of discrete interventions (Shankland and Rosset, 2017; Waters, 2011). For instance, a 2-week intervention using gratitude journals (Froh et al., 2008) or a series of mindfulness meditation practices (Broderick and Metz, 2009). Hendriks et al. (2020), p. 358) define positive psychology interventions (or PPIs) as “interventions aiming at increasing positive feelings, behaviors, and cognitions, while also using theoretically and empirically based pathways or strategies to increase well-being.” They contrast single component PPIs that target only one component of wellbeing (such as the counting blessings or mindfulness exercises mentioned above) with “multi-component positive psychology interventions” (or MPPIs) which draw on multiple types of activities and address multiple facets of wellbeing. This includes programmes that incorporate a “PERMA” wellbeing framework (see Learning environment below). It has been argued that PPIs comprising numerous components and targeting multiple facets/domains of wellbeing are more likely to lead to positive and long-lasting change (Rusk et al., 2018).

In a recent review of MPPIs (Hendriks et al., 2020), the majority of interventions were delivered online (84% of 50 studies and 6141 participants), were 8 weeks long on average, and often delivered in group settings (43%). These descriptors are mirrored in the current wellbeing program outlined in Section 4. Many MPPIs reviewed were designed for individuals with diagnoses of health conditions or mental health disorders (rather than for the general population) and often comprised psychotherapy or CBT components. There were only a very small number of examples of MPPIs with university students (e.g., Koydemir and Sun-Selışık, 2016; Uliaszek et al., 2016; Myers et al., 2017).

PERMA

Martin Seligman, (2011) PERMA framework is a prolific model of wellbeing within Positive Psychology which has been integrated within educational settings (Hoare et al., 2017). The PERMA framework considers wellbeing to be broadly comprised of five facets: Positive emotions (hedonic feelings of happiness such as joy and contentment); Engagement (feeling absorbed and engaged in life and connected to activities/organisations); positive Relationships (feeling socially integrated, cared about and supported by others); Meaning or purpose (believing that one’s life is valuable and feeling connected to something greater than oneself); and a sense of Accomplishment (making progress toward goals, feeling capable). The PERMA models suggests that we flourish through balancing the Pleasant Life (feeling good or hedonic wellbeing) with the Meaningful Life (having purpose, contribution and belonging, or eudaimonic wellbeing) (Seligman, 2011). This PERMA approach has subsequently been extended to recognise the importance of physical health in overall wellbeing; PERMA-H models include a positive health dimension thereby offering a more holistic view of wellbeing that includes practices for optimal physical and psychological health (Norrish et al., 2013; Lai et al., 2018).

Despite there being disagreement over the components of wellbeing and alternate conceptions of wellbeing proposed (e.g., Ryff (1989) theory of psychological wellbeing), there is wide agreement that wellbeing is a multi-faceted construct (Ryff, 1989; Ryan and Deci, 2001; Huppert and So, 2013). With further agreement that wellbeing includes emotional, social, psychological and functional aspects (Forgeard et al., 2011) and, more recently, physical health-related dimensions (Sears, 2013). The PERMA-H approach has been chosen here due to its explicit inclusion of physical health alongside affective, social and psychological aspects of wellbeing. Moreover, one of the underpinning tenants of the PERMA(H) model, and the subsequent measures of PERMA(H) that have been developed, is that it comprises both hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing perspectives. One of the main criticisms of PERMA(H) has been the lack of supporting empirical evidence. However, recent efforts to address this gap have supported the PERMA facets of wellbeing across over 15,000 people worldwide, including in longitudinal studies with college students (Butler and Kern, 2016; Coffey et al., 2016). In further support of the use of PERMA, theoretical and empirical research has championed its use in educational settings (Oades et al., 2011; Norrish et al., 2013). The PERMA-H model was considered, by the current authors, as accessible to all key stakeholders involved in the program.

Integration of the PERMA-H model within schools has been linked to student, educator, and parental health and wellbeing (Vella-Brodrick et al., 2014; Williams et al., 2015; Dubroja et al., 2016). Geelong Grammar School in Australia implements PERMA-H through their “learn it, live it, teach it, embed it” ethos. This approach advocates sharing of wellbeing opportunities, concepts and frameworks; active enabling of wellbeing across school activities, and enacting wellbeing through personal use of strengths and skills; explicit teaching of character strengths and wellbeing skills within the classroom; and embedding of positive education within the entire school community including in school policies and practices (Hoare et al., 2017). Other examples of PERMA (or PERMA-H) programmes in schools include “Flourish” (Gray et al., 2020), “The Flourishing Life” (Au and Kennedy, 2018), and Maytiv positive psychology school program (Shoshani et al., 2016).

Outside of schools, a positive education approach has also been recommended for universities:

“there would seem to be an opportunity for positive psychology to enhance the experience of campus life by influencing the development of a higher educational culture that understands the psychosocial determinants of wellbeing (e.g., positive emotions-traits-institutions) and seeks to create conditions that cultivate wellbeing in students and staff” (Oades et al., 2011, p.433).

Oades and colleagues advocate for the integration of the PERMA framework across classroom and formal learning environments in universities, as well as social environments, local community, within Schools/Departments, and in student halls and accommodation. Specifically, they argue for explicit approaches to enhancing student wellbeing in HE through the cultivation of positive emotion and positive relationships, engagement in learning and the local community, and making meaningful contributions to their course and university.

Pedagogical Format, Objectives and Learning Environment

Overview of the Wellbeing Program

The aim of the wellbeing program was to 1) provide students with a community and an opportunity to feel connected with other students 2) introduce students to key concepts of wellbeing 3) equip the students with tools that would help improve their wellbeing. These aims align with the PERMA framework with regards to promoting a pleasant and meaningful life, and helps to foster a positive education approach through teaching wellbeing skills alongside academic studies (e.g., Seligman et al., 2009).

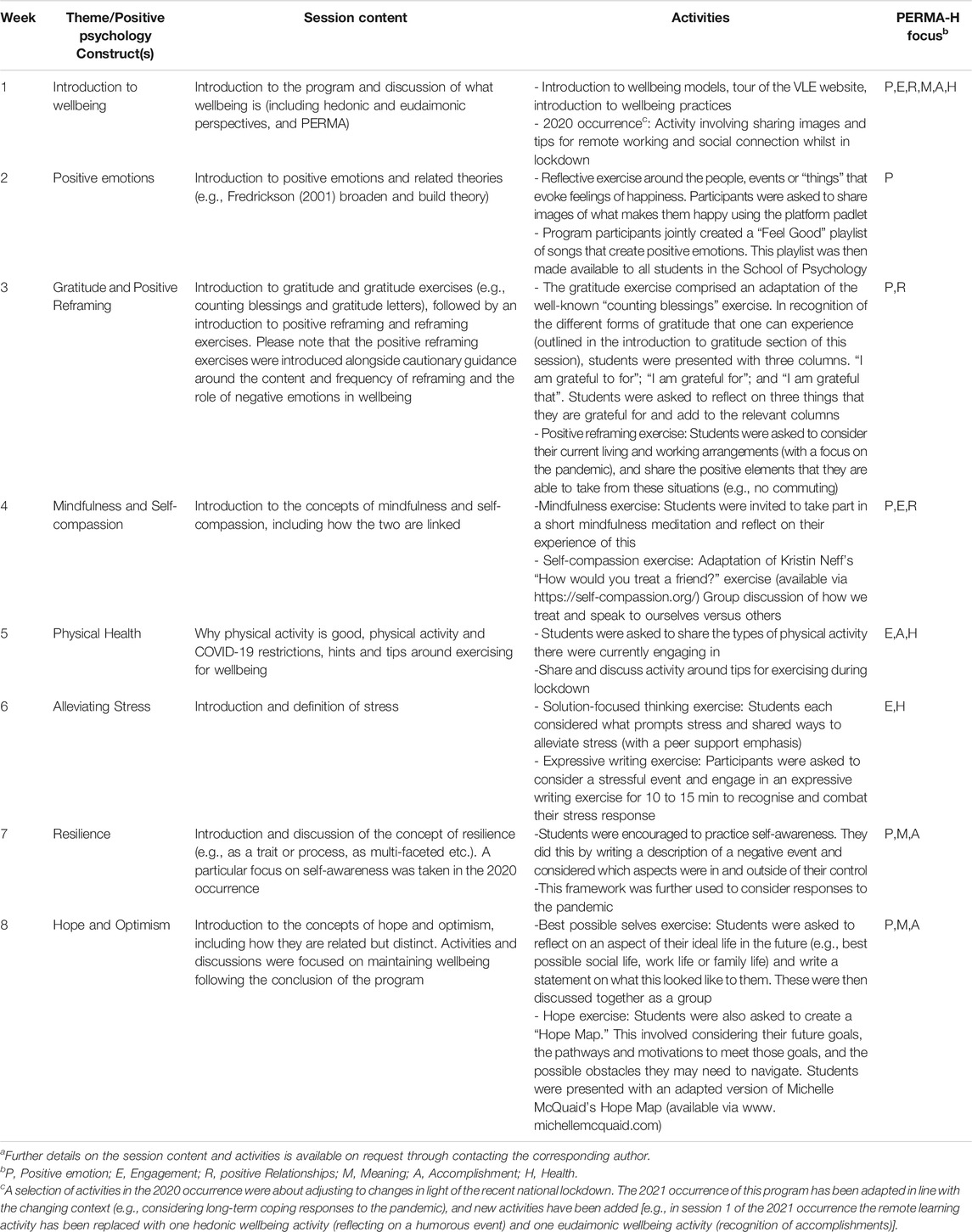

The program was organised into eight, weekly, 1-h wellbeing sessions. These weekly sessions were focused on Positive Psychology constructs and practices (see Table 1). The wellbeing sessions began with a brief presentation that included an introduction to the area and key constructs, and an overview of the activities. For some sessions, participants were encouraged to take part in the activities synchronously and share their thoughts or experiences. Other sessions included a toolkit of activities that participants could take away with them. All wellbeing sessions and activities were uploaded to a supporting VLE, where students could access the resources outside of the wellbeing sessions.

TABLE 1. Overview of weekly wellbeing sessions, activities and PERMA-H focusa.

An 8-week program was deemed suitable as previous literature has suggested positive psychology interventions typically range from 4–8 weeks (e.g. Bolier et al., 2013). Moreover, lengthy interventions contribute to high levels of attrition amongst participants (Ryan et al., 2010). The first weekly wellbeing session took place on 25th March 2020, with the final session on the 13th May 20201.

Learning Environment

The wellbeing program took place in a university in the West Midlands, UK. The university is a medium-sized, campus university with approximately 10,000 students and a larger than average proportion of mature students (over the age of 21) and students from diverse backgrounds or those entering university through access to HE routes. The wellbeing program was delivered within the School of Psychology, which consists of approximately 500 undergraduate students and 60 postgraduate taught students. Participation was on a voluntary basis and attendance was not logged.

The wellbeing program was delivered by a range of lecturing staff in the School of Psychology. The weekly sessions were delivered by staff synchronously through an online Virtual Learning Environment (VLE). The practical implications of this will be further discussed in Practical Implications and Lessons Learned.

Results to Date

This wellbeing program was implemented as an opportunity for students to enhance their wellbeing and socialisation at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. At that time, the priority and focus was on providing wellbeing support in a timely fashion rather than on setting up an evaluation of the program’s efficacy. Although anecdotal feedback indicated this intervention was a useful resource for students during the initial months of the pandemic, an evaluation of this wellbeing program is required.

Consequently, during the 2020-2021 occurrence of this wellbeing program (starting in Semester 2 of the 2020–21 academic year), an evaluation of the program will be conducted. The evaluation will involve a repeated-measures, mixed research design with pre and post quantitative surveys and follow up qualitative interviews. A control group from the same student cohort who do not opt-in to the program will be sought for comparative purposes. In the quantitative stage of the research, students will be asked to complete measures of wellbeing, anxiety, depression, academic burnout and sense of community. These measures will be completed in the week preceding the wellbeing program, and the week following the completion of the 8-week program. Following from previous positive psychology interventions and the underpinning PERMA-H framework, it is anticipated that, following the program, students’ self-reported levels of wellbeing and sense of community will increase, and that self-reported anxiety, depression and academic burnout will decrease. It is also anticipated that the magnitude of these effects will be contingent on the number of sessions students have engaged with and the degree to which wellbeing practices are performed outside of the weekly sessions.

Students who complete the program will be invited to take part in a semi-structured qualitative interview. The objective of this qualitative phase is to obtain deeper insight into the participants’ experience of the 8-week program, including perceived benefits in relation to the PERMA framework. The qualitative phase will also assist in informing future delivery of the wellbeing program by identifying any barriers or difficulties encountered during participation.

Practical Implications and Lessons Learned

The use of internet-based interventions to support wellbeing in higher education has been encouraged (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2011), with online interventions having greater feasibility in comparison to traditional face-to-face or blended delivery approaches due to the ease of accessing the programmes and its flexible engagement (e.g., Schreiber and Aartun, 2011). Moreover, online interventions have been shown to be beneficial for those who are resistant to seek help due to stigma, which makes them accessible to individuals who may have not sought support previously (Barrable et al., 2018). A recent systematic review highlighted the usefulness of internet-based interventions in accommodating the diversity of mental health conditions present in university students in addition to promoting general wellbeing (Harrer et al., 2019). It is also important to note here that during the early stages of the pandemic, the UK was in lockdown, meaning that online delivery was the only option for this wellbeing program due to the government restrictions. Therefore, the implementation of an online wellbeing program was not only a practical approach but the only feasible one. In terms of engagement in programmes during the pandemic, research has indicated that face-to-face wellbeing programmes may have encouraged more active engagement and social integration with peers (Huber et al., 2018). This indicates the importance of considering the balance between accessibility and engagement for future program delivery.

As outlined in Pedagogical Format, Objectives and Learning Environment, the wellbeing program was delivered using a VLE. The VLE was a useful platform through which students could attend the weekly wellbeing sessions but also gain extended access to the sources of wellbeing support. Offering this permanent access to materials was an important component of the program as self-management of wellbeing and mental health is a useful tool for individuals who are reluctant to seek formal support (Griffiths and Christensen, 2007). This approach sought to promote autonomy and self-facilitation of wellbeing, akin to similar online interventions (e.g., Papadatou-Pastou et al., 2019).

During the wellbeing sessions participants were encouraged to share their thoughts and experiences, ergo an associated risk with this approach was that participants might disclose information about their mental health or a mental illness which could prompt safeguarding issues and create discomfort for other students. At the beginning of the program, participants were asked to follow a set of “guidelines” with regards to appropriate disclosure. For example, students were informed that “when engaging with any discussion forums or interactive activities on this site, please refrain from disclosing information that others might find distressing” and “interaction with this site is not anonymous, therefore, any private discussions should be directed toward your Personal Academic Tutor.” Program facilitators had the responsibility of enforcing these guidelines and continually made students aware that the wellbeing program was not designed to offer specific, tailored mental health or mental illness support. Whilst the remit of the program was clearly communicated to students, this could have contradicted students’ expectations.

Relatedly, constant vigilance around students’ posts and comments was required. For each wellbeing session, a minimum of two members of staff were present; with one member of staff acting as a facilitator of the activities and the other as a moderator of the conversation to ensure that comments in the chat box were safe and appropriate (see Taylor et al., 2016). The facilitators of the program had research expertise and knowledge of the area of wellbeing, however, it is important to note that the staff were not formally trained in providing wellbeing interventions.

Staff delivering the program had ongoing, professional relationships with the students. This familiarity with staff could have encouraged student participation (Jorm and Griffiths, 2006), however, could also be viewed as a limitation with regards to the balance of power. Typically, lecturers are perceived to own the power, due to their role in directing students to complete tasks (Michail, 2011). With regards to the wellbeing intervention, lecturers as facilitators meant that the students may have viewed the sessions as another type of teaching and learning experience. This may have also had a negative impact on the extent to which students shared information with their peers in the sessions (e.g., through feeling uncomfortable or reluctant in sharing personal information with a member of staff). Because of this, participants were allowed to remain in the session to talk with peers, after the facilitators had left. Due to the aforementioned issues regarding disclosures, it is important to note that trained peer mentors were present in these discussions. To help counteract any social isolation as a result of the first national lockdown, further peer support and social connectedness was encouraged in the wellbeing sessions through the use of “Padlet”2, a chat box and the use of microphones and video during the session to facilitate conversation.

One practical implication to consider with regards to the delivery of this program was its voluntary nature. Student engagement was an important aspect of the weekly wellbeing sessions and arguably, students who are less engaged in their academic studies, may be less likely to engage in a wellbeing program (e.g., Bond et al., 2020). Crucially, these less engaged students may benefit more from a wellbeing program due to the notion that wellbeing can increase academic engagement and achievement (Seligman et al., 2009; Waters, 2011). This signposts that not all students are likely to engage and benefit from the current approach. Moreover, students’ mental health literacy may have also influenced their engagement; students who have increased knowledge of mental health literacy and wellbeing demonstrate self-management (Gulliver et al., 2010), suggesting that there may be a level of self-motivation to engage in such a wellbeing program. Consequently, those lacking self-motivation may not benefit from a program like the one we have described here.

Constraints Relating to the Program and Approach

This wellbeing intervention was designed in response to the pandemic and in a short period of time. In the UK, the lockdown restrictions began on the 16th March 2020 and the wellbeing program was implemented on the 25th March 2020. As a result of this short timescale, the staffing of the wellbeing program presented challenges at times. This was due to the wellbeing sessions being delivered in parallel with lectures, seminars and student tutorials, alongside extended assignment deadlines. At the time of the program, staff were also tasked with moving the delivery of teaching online, in addition to maintaining their duties in providing academic and pastoral support to students. This indicates implications of delivering the 8-week program on staff workload.

Resultantly, increasing student wellbeing provision in the School during this challenging time could have had knock-on (or trade-off) effects in terms of staff wellbeing. This brings into question where wellbeing programmes should be situated-at a School/Departmental or organisational level? At a School level, relationships between staff and students have already been established, which could encourage participation (Jorm and Griffiths, 2006). Alternatively, at a wider organisational level, wellbeing provision could be delivered centrally by trained staff, where this commitment is recognised in job role and workload.

The program itself was not cost-intensive as there were no financial requirements in the creation or delivery of this program (especially as staff time was not compensated in this occurrence). This should be considered an advantage to the HEI given the well-documented budget cuts to HE over the past decade. These budget cuts have changed the landscape of Higher of Higher Education and made HEIs reliant on fees provided from students, rather than on government funding (House of Commons, 2020). Consequently, budget cuts have altered the priority of HEIs to focus on the recruitment and retention of students (e.g. Calma and Dickson-Deane, 2020). There is an argument that wellbeing interventions could help with the retention of students at universities, particularly as students often withdraw university due personal reasons, including mental health (Van Bragt et al., 2011). Therefore, investing in student mental health and wellbeing support should pay dividends not only in terms of mental health outcomes but also in terms of continuation of studies, student fees and satisfaction metrics. This could be further explored in future research projects, examining the longitudinal effects of wellbeing interventions on retention.

The current wellbeing program follows an MPPI approach which is commonly utilised within positive psychology and integrated into educational contexts (Hendriks et al., 2020). However, an arguably more effective approach to cultivating wellbeing is to embed character and wellbeing enhancement into the curriculum (Hoare et al., 2017)–a suggestion that has previously been advocated within HE. For example, Houghton and Anderson (2017) have argued for a “whole-university” approach where wellbeing is incorporated into the curriculum, learning support, specific disability and mental health services, and wider university services (not dissimilar to the Healthy Universities approach, Dooris et al., 2010). Houghton and Anderson further suggest that wellbeing should be embedded into the curriculum content, so students can understand the concept of wellbeing, and within curriculum processes as to foster inclusive practices and a sense of belonging.

The aforementioned points regarding voluntary wellbeing programmes being reliant on engagement and self-motivation (Bond et al., 2020) provide further support for wellbeing being embedded into the curriculum content and processes to ensure that all students can access its benefits. This is not an easy goal to accomplish, however, as it requires an explicit joined-up approach throughout the HEI. Akin to how whole-school, multi-component approaches to mental health and wellbeing that comprise collective action appear more effective in promoting wellbeing and accounting for the complexities in school systems (Hoare et al., 2017), a whole-university approach that integrates and embeds wellbeing throughout its systems is likely to offer increased effectiveness over stand-alone programmes in HEIs. In line with Oades et al. (2011), it is our hope that HEIs will move toward a consistent integration of wellbeing frameworks, such as PERMA, across the various levels in which it works with wellbeing embedded into curricula in addition to the existing central provisions that are well established.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed to the development of this article, and to the development and delivery of the wellbeing programme outlined. BM has led on the conception and design of the wellbeing programme and the Frontiers article with substantial contribution from LS.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1It should be noted that this period coincided with the university’s examination and assessment period. During the program (March–May 2020), students were undergoing preparation of assessments and one of two assessment submission periods in the academic year.

2Padlet is an online platform where participants are allowed to post and share their thoughts, ideas and images.

References

Adnan, M., and Anwar, K. (2020). Online Learning Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Students' Perspectives. Online Submission 2 (1), 45–51. doi:10.33902/jpsp.2020261309

Andrews, B., and Wilding, J. M. (2004). The Relation of Depression and Anxiety to Life-Stress and Achievement in Students. Br. J. Psychol. 95, 509–521. doi:10.1348/0007126042369802

Au, W. C. C., and Kennedy, K. J. (2018). A Positive Education Program to Promote Wellbeing in Schools: a Case Study from a Hong Kong School. Hes 8 (4), 9–22. doi:10.5539/hes.v8n4p9

Auerbach, R. P., Mortier, P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., et al. (2018). WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: Prevalence and Distribution of Mental Disorders. J. abnormal Psychol. 127 (7), 623–638. doi:10.1037/abn0000362

Barrable, A., Papadatou-Pastou, M., and Tzotzoli, P. (2018). Supporting Mental Health, Wellbeing and Study Skills in Higher Education: An Online Intervention System. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 12 (1), 54. doi:10.1186/s13033-018-0233-z

Bewick, B., Koutsopoulou, G., Miles, J., Slaa, E., and Barkham, M. (2010). Changes in Undergraduate Students' Psychological Well‐being as They Progress through University. Stud. Higher Educ. 35 (6), 633–645. doi:10.1080/03075070903216643

Bolier, L., Haverman, M., Westerhof, G. J., Riper, H., Smit, F., and Bohlmeijer, E. (2013). Positive Psychology Interventions: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Studies. BMC Public Health 13, 119. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-119

Bond, M., Buntins, K., Bedenlier, S., Zawacki-Richter, O., and Kerres, M. (2020). Mapping Research in Student Engagement and Educational Technology in Higher Education: A Systematic Evidence Map. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High Educ. 17 (1), 2. doi:10.1186/s41239-019-0176-8

Boniwell, I. (2012). Positive Psychology in A Nutshell: The Science of Happiness: The Science of Happiness. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

Broderick, P. C., and Metz, S. (2009). Learning to BREATHE: A Pilot Trial of a Mindfulness Curriculum for Adolescents. Adv. Sch. Ment. Health Promot. 2, 35–46. doi:10.1080/1754730x.2009.9715696

Brown, J., Busfield, R., O’Shea, A., and Sibthorpe, J. (2011). School Ethos and Personal, Social, Health Education. Pastoral Care Educ. 29 (2), 117–131. doi:10.1080/02643944.2011.573491

Burns, D., Dagnall, N., and Holt, M. (2020). “Assessing the Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Student Wellbeing at Universities in the UK: a Conceptual Analysis,” in Frontiers in Education (Lausanne, Switzerland: Frontiers Media).

Butler, J., and Kern, M. L. (2016). The PERMA-Profiler: A Brief Multidimensional Measure of Flourishing. Intnl. J. Wellbeing 6 (3), 1–48. doi:10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526

Calma, A., and Dickson-Deane, C. (2020). The Student as Customer and Quality in Higher Education. Ijem 34 (8), 1221–1235. doi:10.1108/IJEM-03-2019-0093

Coffey, J. K., Wray-Lake, L., Mashek, D., and Branand, B. (2016). A Multi-Study Examination of Well-Being Theory in College and Community Samples. J. Happiness Stud. 17, 187–211. doi:10.1007/s10902-014-9590-8

Connell, J., Barkham, M., and Mellor-Clark, J. (2007). CORE-OM Mental Health Norms of Students Attending University Counselling Services Benchmarked against an Age-Matched Primary Care Sample. Br. J. Guidance Counselling 35 (1), 41–57. doi:10.1080/03069880601106781

Dandridge, N. (2018). Mental Health and Wellbeing: a Priority. Bristol, UK: Office for Students. Available at: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/news-blog-and-events/our-news-and-blog/mental-health-and-wellbeing-a-priority/ (Accessed November 11).

Dawson, D. L., and Golijani-Moghaddam, N. (2020). COVID-19: Psychological Flexibility, Coping, Mental Health, and Wellbeing in the UK during the Pandemic. J. contextual Behav. Sci. 17, 126–134. doi:10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.07.010

DfES (2005). Excellence and Enjoyment: Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning [SEAL]. Nottingham: Department for Education and Skills. Reference Number: DfES/0110/2005.

Dickinson, I. (2019). Only the Lonely: Loneliness, Student Activities and Mental Wellbeing. WONKE Blog. Available at: https://wonkhe.com/blogs/only-the-lonely-loneliness-student-activities-and-mental-wellbeing/ (Accessed November 19, 2020).

Donaldson, S. I., Dollwet, M., and Rao, M. A. (2015). Happiness, Excellence, and Optimal Human Functioning Revisited: Examining the Peer-Reviewed Literature Linked to Positive Psychology. J. Positive Psychol. 10 (3), 185–195. doi:10.1080/17439760.2014.943801

Dooris, M. T., Cawood, J., Doherty, S., and Powell, S. (2010). Healthy Universities: Concept, Model and Framework for Applying the Healthy Settings Approach within Higher Education in England. Preston, UK: UCLan.

Dubroja, K., O’Connor, M., and Mckenzie, V. (2016). Engaging Parents in Positive Education: Results from a Pilot Program. Int. J. Wellbeing 6, 150–168. doi:10.5502/ijw.v6i3.443

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., and Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The Impact of Enhancing Students' Social and Emotional Learning: A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Universal Interventions. Child. Develop. 82, 405–432. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Eisenberg, D., Golberstein, E., and Hunt, J. B. (2009). Mental Health and Academic Success in College. BE J. Econ. Anal. Pol. 9, 1–35. doi:10.2202/1935-1682.2191

Forgeard, M. J. C., Jayawickreme, E., Kern, M., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Doing the Right Thing: Measuring Wellbeing for Public Policy. Int. J. Wellbeing 1 (1), 79–106. doi:10.5502/ijw.v1i1.15

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The Role of Positive Emotions in Positive Psychology: The Broaden-And-Build Theory of Positive Emotions. Am. Psychol. 56 (3), 218–226. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.56.3.218

Froh, J. J., Sefick, W. J., and Emmons, R. A. (2008). Counting blessings in early adolescents: an experimental study of gratitude and subjective well-being. J. Sch. Psychol. 46 (2), 213–233.

Goodman, F. R., Disabato, D. J., Kashdan, T. B., and Kauffman, S. B. (2017). Measuring Well-Being: A Comparison of Subjective Well-Being and PERMA. J. Positive Psychol. 13, 321–332. doi:10.1080/17439760.2017.1388434

Grant, A. (2006). “Personal Tutoring: A System in Crisis?,” in Personal Tutoring in Higher Education. Stoke on Trent. Editors L. Thomas, and P. Hixenbaugh (Stoke-on-Trent, UK: Trentham Books).

Gray, A., Beamish, P., and Morey, P. (2020). Flourish: The Impact of an Intergenerational Program on Third-Grade Students’ Social and Emotional Wellbeing with Application to the PERMA Framework. TEACH. J. Christian Educ. 14 (1), 26–37.

Griffiths, K. M., and Christensen, H. (2007). Internet-based Mental Health Programs: A Powerful Tool in the Rural Medical Kit. Aust. J. Rural Health 15 (2), 81–87. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00859.x

Groarke, J. M., Berry, E., Graham-Wisener, L., McKenna-Plumley, P. E., McGlinchey, E., and Armour, C. (2020). Loneliness in the UK during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Results from the COVID-19 Psychological Wellbeing Study. PloS one 15 (9), e0239698. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0239698

Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., and Christensen, H. (2010). Perceived Barriers and Facilitators to Mental Health Help-Seeking in Young People: A Systematic Review. BMC Psychiatry 10 (1), 113. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-10-113

Hagenauer, G., and Volet, S. E. (2014). Teacher-student Relationship at University: an Important yet Under-researched Field. Oxford Rev. Educ. 40 (3), 370–388. doi:10.1080/03054985.2014.921613

Hager, N. M., Judah, M. R., and Milam, A. L. (2020). Loneliness and Depression in College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Boredom and Repetitive Negative Thinking as Mediators. Preprint repository name [Preprint]. Available at: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-101533/v1 (Accessed November 3, 2020). doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-101533/v1

Harrer, M., Adam, S. H., Baumeister, H., Cuijpers, P., Karyotaki, E., Auerbach, R. P., et al. (2019). Internet Interventions for Mental Health in University Students: A Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 28 (2), e1759. doi:10.1002/mpr.1759

Harzer, C. (2016). “The Eudaimonics of Human Strengths: The Relations between Character Strengths and Well-Being,” in Handbook of Eudaimonic Well-Being. Editor J. Vitterso (Cham, Switzerland: Springer), 307–322. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-42445-3_20

Hendriks, T., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Hassankhan, A., De Jong, J., and Bohlmeijer, E. (2020). The Efficacy of Multi-Component Positive Psychology Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Happiness Stud. 21 (1), 357–390. doi:10.1007/s10902-019-00082-1

Hoare, E., Bott, D., and Robinson, J. (2017). Learn it, Live it, Teach it, Embed it: Implementing a Whole School Approach to Foster Positive Mental Health and Wellbeing through Positive Education. Intnl. J. Wellbeing 7 (3), 56–71. doi:10.5502/ijw.v7i3.645

Houghton, A. M., and Anderson, J. (2017). Embedding Mental Wellbeing in the Curriculum: Maximising Success in Higher Education. Available at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/embedding-mental-wellbeing-curriculum-maximising-success-higher-education (Accessed May 10, 2017).

House of Commons (2020). Higher Education Funding in England. Available at: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7973/ (Accesesd November 11).

Huber, J., Muck, T., Maatz, P., Keck, B., Enders, P., Maatouk, I., et al. (2018). Face-to-face vs. Online Peer Support Groups for Prostate Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Comparison Study. J. Cancer Surviv 12 (1), 1–9. doi:10.1007/s11764-017-0633-0

Hugo, M., Declerck, H., Fitzpatrick, G., Severy, N., Gbabai, O. B. M., and Decroo, T. (2015). Post-traumatic Stress Reactions in Ebola Virus Disease Survivors in Sierra Leone. Emerg. Med. (Los Angeles) 5, 1–4. doi:10.4172/2165-7548.1000285

Huppert, F. A., and So, T. T. C. (2013). Flourishing across Europe: Application of a New Conceptual Framework for Defining Well-Being. Soc. Indic Res. 110 (3), 837–861. doi:10.1007/s11205-011-9966-7

Ishii, T., Tachikawa, H., Shiratori, Y., Hori, T., Aiba, M., Kuga, K., et al. (2018). What Kinds of Factors Affect the Academic Outcomes of University Students with Mental Disorders? A Retrospective Study Based on Medical Records. Asian J. Psychiatry 32, 67–72. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2017.11.017

Jorm, A. F., and Griffiths, K. M. (2006). Population Promotion of Informal Self-Help Strategies for Early Intervention against Depression and Anxiety. Psychol. Med. 36 (1), 3–6. doi:10.1017/S0033291705005659

Kelland, K. (2020). U.N. Warns of Global Mental Health Crisis Due to COVID-19 Pandemic. Cologny, Switzerland: World Economic Forum. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/united-nations-global-mental-health-crisis-covid19-pandemic (Accessed December 4, 2020).

Kern, M. L., Waters, L. E., Adler, A., and White, M. A. (2015). A Multidimensional Approach to Measuring Well-Being in Students: Application of the PERMA Framework. J. Positive Psychol. 10 (3), 262–271. doi:10.1080/17439760.2014.936962

Kerr, D. (1999). Citizenship Education in the Curriculum: An International Review. Sch. Field 10 (3/4), 5–32.

Koydemir, S., and Sun-Selışık, Z. E. (2016). Well-being on Campus: Testing the Effectiveness of an Online Strengths-Based Intervention for First Year College Students. Br. J. Guidance Counselling 44 (4), 434–446. doi:10.1080/03069885.2015.1110562

Kristjánsson, K. (2012). Positive Psychology and Positive Education: Old Wine in New Bottles?. Educ. Psychol. 47 (2), 86–105. doi:10.1080/00461520.2011.610678

Lai, M. K., Leung, C., Kwok, S. Y., Hui, A. N., Lo, H. H., Leung, J. T., et al. (2018). A Multidimensional PERMA-H Positive Education Model, General Satisfaction of School Life, and Character Strengths Use in Hong Kong Senior Primary School Students: Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Path Analysis Using the APASO-II. Front. Psychol. 9, 1090. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01639

Lipson, S. K., and Eisenberg, D. (2018). Mental Health and Academic Attitudes and Expectations in University Populations: Results from the Healthy Minds Study. J. Ment. Health 27 (3), 205–213. doi:10.1080/09638237.2017.1417567

Meo, S. A., Abukhalaf, A. A., Alomar, A. A., Sattar, K., and Klonoff, D. C. (2020). COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact of Quarantine on Medical Students’ Mental Wellbeing and Learning Behaviors. Pakistan J. Med. Sci. 36 (COVID19-S4), S43–S48. doi:10.12669/pjms.36.covid19-s4.2809

Michail, S. (2011). Understanding School Responses to Students' Challenging Behaviour: A Review of Literature. Improving Schools 14 (2), 156–171. doi:10.1177/1365480211407764

Morgan, B., and Gulliford, L. (2017). “Cultivating Gratitude: Measuring Gratitude and the Implications for Fostering Gratitude in University Students,” in Cultivating Virtue in the University: Perspectives from History, Literature, Philosophy, Theology, and the Social Sciences. Editors J. Brant, and M. Lamb (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press). doi:10.1037/t59814-000

Myers, N. D., Prilleltensky, I., Prilleltensky, O., McMahon, A., Dietz, S., and Rubenstein, C. L. (2017). Efficacy of the Fun for Wellness Online Intervention to Promote Multidimensional Well-Being: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Prev. Sci. 18 (8), 984–994. doi:10.1007/s11121-017-0779-z

Norrish, J. M., Williams, P., O'Connor, M., and Robinson, J. (2013). An Applied Framework for Positive Education. Int. J. Wellbeing 3 (2), 147–161. doi:10.5502/ijw.v3i2.2

Oades, L. G., Robinson, P., Green, S., and Spence, G. B. (2011). Towards a Positive University. J. Positive Psychol. 6 (6), 432–439. doi:10.1080/17439760.2011.634828

O'Connor, R. C., Wetherall, K., Cleare, S., McClelland, H., Melson, A. J., Niedzwiedz, C. L., et al. (2020). Mental Health and Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Longitudinal Analyses of Adults in the UK COVID-19 Mental Health & Wellbeing Study. Br. J. Psychiatry, 1–8. doi:10.1192/bjp.2020.212

Odriozola-González, P., Planchuelo-Gómez, Á., Irurtia, M. J., and de Luis-García, R. (2020). Psychological Effects of the COVID-19 Outbreak and Lockdown Among Students and Workers of a Spanish University. Psychiatry Res. 290, 113108. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113108

Office for National Statistics [ONS] (2020). Coronavirus and the Social Impacts on Great Britain Data. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandco mmunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/datasets/coronavirusandtheso cialimpactsongreatbritaindata (Accessed November 19, 2020).

Papadatou-Pastou, M., Campbell-Thompson, L., Barley, E., Haddad, M., Lafarge, C., McKeown, E., et al. (2019). Exploring the Feasibility and Acceptability of the Contents, Design, and Functionalities of an Online Intervention Promoting Mental Health, Wellbeing, and Study Skills in Higher Education Students. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 13 (1), 51. doi:10.1186/s13033-019-0308-5

Park, N., Peterson, C., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Strengths of Character and Well-Being. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 23, 603–619. doi:10.1521/jscp.23.5.603.50748

Peterson, C., Ruch, W., Beermann, U., Park, N., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2007). Strengths of Character, Orientations to Happiness, and Life Satisfaction. J. Positive Psychol. 2, 149–156. doi:10.1080/17439760701228938

Roberts, R., Golding, J., Towell, T., and Weinreb, I. (1999). The Effects of Economic Circumstances on British Students' Mental and Physical Health. J. Am. Coll. Health 48, 103–109. doi:10.1080/07448489909595681

Royal College of Psychiatrists (2011). Mental Health of Students in Higher Education. Available at: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/college-report-cr166.pdf?sfvrsn=d5fa2c24_2 (Accessed November 11).

Rusk, R. D., and Waters, L. E. (2013). Tracing the Size, Reach, Impact, and Breadth of Positive Psychology. J. Positive Psychol. 8 (3), 207–221. doi:10.1080/17439760.2013.777766

Rusk, R. D., Vella-Brodrick, D. A., and Waters, L. (2018). A Complex Dynamic Systems Approach to Lasting Positive Change: The Synergistic Change Model. J. Positive Psychol. 13 (4), 406–418. doi:10.1080/17439760.2017.1291853

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2001). On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 141–166. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

Ryan, M. L., Shochet, I. M., and Stallman, H. M. (2010). Universal Online Interventions Might Engage Psychologically Distressed University Students Who Are Unlikely to Seek Formal Help. Adv. Ment. Health 9 (1), 73–83. doi:10.5172/jamh.9.1.73

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness Is Everything, or Is it? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 57 (6), 1069–1081. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Savage, M. J., James, R., Magistro, D., Donaldson, J., Healy, L. C., Nevill, M., et al. (2020). Mental Health and Movement Behaviour during the COVID-19 Pandemic in UK University Students: Prospective Cohort Study. Ment. Health Phys. Activity 19, 100357. doi:10.1016/j.mhpa.2020.100357

Savage, M. (2020). Covid-19 Has Increased Anxiety for Many of Us, and Experts Warn a Sizable Minority Could Be Left with Mental Health Problems that Outlast the Pandemic. BBC News Article. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20201021-coronavirus-the-possible-long-term-mental-health-impacts (Accessed December 4, 2020).

Schneiderman, N., Ironson, G., and Siegel, S. D. (2005). Stress and Health: Psychological, Behavioral, and Biological Determinants. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 1, 607–628. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144141

Schreiber, B., and Aartun, K. (2011). Online Support Service via Mobile Technology-A Pilot Study at a Higher Education Institution in South Africa. J. Psychol. Africa 21 (4), 635–641. doi:10.1080/14330237.2011.10820512

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., and Peterson, C. (2005). Positive Psychology Progress: Empirical Validation of Interventions. Am. Psychol. 60 (5), 410–421. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.60.5.410

Seligman, M. E. P., Ernst, R. M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., and Linkins, M. (2009). Positive Education: Positive Psychology and Classroom Interventions. Oxford Rev. Educ. 35 (3), 293–311. doi:10.1080/03054980902934563

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish – A New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being – and How to Achieve Them. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Shankland, R., and Rosset, E. (2017). Review of Brief School-Based Positive Psychological Interventions: A Taster for Teachers and Educators. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 29 (2), 363–392. doi:10.1007/s10648-016-9357-3

Sheldon, K. M., Fredrickson, B., Rathunde, K., Csikszentmihalyi, M., and Haidt, J. (2000). Positive Psychology Manifesto. Manifesto Presented at Akumal 1 Conference and Revised during the Akumal 2 Meeting. Available at: https://ppc.sas.upenn.edu/sites/default/files/Positive%20Psychology%20Manifesto.docx (Accessed June 5, 2019).

Shoshani, A., Steinmetz, S., and Kanat-Maymon, Y. (2016). Effects of the Maytiv Positive Psychology School Program on Early Adolescents' Well-Being, Engagement, and Achievement. J. Sch. Psychol. 57, 73–92. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2016.05.003

Sin, N. L., and Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing Well‐being and Alleviating Depressive Symptoms with Positive Psychology Interventions: A Practice‐friendly Meta‐analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 65 (5), 467–487. doi:10.1002/jclp.20593

Stewart-Brown, S., Evans, J., Patterson, J., Peterson, S., Doll, H., Balding, J., et al. (2000). The Health of Students in Institutes of Higher Education: an Important and Neglected Public Health Problem?. J. Public Health Med. 22, 492–499. doi:10.1093/pubmed/22.4.492

Taylor, C. B., Kass, A. E., Trockel, M., Cunning, D., Weisman, H., Bailey, J., et al. (2016). Reducing Eating Disorder Onset in a Very High-Risk Sample with Significant Comorbid Depression: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Consulting Clin. Psychol. 84 (5), 402–414. doi:10.1037/ccp0000077

Uliaszek, A. A., Rashid, T., Williams, G. E., and Gulamani, T. (2016). Group Therapy for University Students: A Randomized Control Trial of Dialectical Behavior Therapy and Positive Psychotherapy. Behav. Res. Ther. 77, 78–85. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.003

Universities UK (2015). Student Mental Wellbeing in Higher Education: Good Practice Guide. Available at: https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Pages/student-mental-wellbeing-in-higher-education.aspx (Accessed December 15, 2020)

Van Bragt, C. A. C., Bakx, A. W. E. A., Teune, P. J., Bergen, T. C. M., and Croon, M. A. (2011). Why Students Withdraw or Continue Their Educational Careers: A Closer Look at Differences in Study Approaches and Personal Reasons. J. Vocational Educ. Train. 63 (2), 217–233. doi:10.1080/13636820.2011.567463

Vella-Brodrick, D. A., Rickard, N. S., and Chin, T-C. (2014). An Evaluation of Positive Education at Geelong Grammar School: A Snapshot of 2013. VIC, Australia: The University Of Melbourne, 14.

Waters, L., and Loton, D. (2019). SEARCH: A Meta-Framework and Review of the Field of Positive Education. Int. J. Appl. Positive Psychol. 4 (1-2), 1–46. doi:10.1007/s41042-019-00017-4

Waters, L. (2011). A Review of School-Based Positive Psychology Interventions. Educ. Develop. Psychol. 28 (2), 75–90.

Watkins, P. C., Grimm, D. L., and Kolts, R. (2004). Counting Your Blessings: Positive Memories Among Grateful Persons. Curr. Psychol. 23 (1), 52–67. doi:10.1007/s12144-004-1008-z

Watkins, P. C., Uhder, J., and Pichinevskiy, S. (2015). Grateful Recounting Enhances Subjective Well-Being: The Importance of Grateful Processing. J. Positive Psychol. 10 (2), 91–98. doi:10.1080/17439760.2014.927909

Watkins, Y. (2019). Mental Wellbeing: Let’s Find New Ways to Support Students. Bristol, UK: Office for Students. Available at: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/news-blog-and-events/our-news-and-blog/mental-wellbeing-let-s-find-new-ways-to-support-students/ (Accessed November 15, 2020).

Williams, P., Kern, M. L., and Waters, L. (2015). A Longitudinal Examination of the Association between Psychological Capital, Perception of Organizational Virtues and Work Happiness in School Staff. Psychol. Well-Being 5 (1), 5. doi:10.1186/s13612-015-0032-0

Keywords: wellbeing, mental health, higher education, positive education, PERMA

Citation: Morgan B and Simmons L (2021) A ‘PERMA’ Response to the Pandemic: An Online Positive Education Programme to Promote Wellbeing in University Students. Front. Educ. 6:642632. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.642632

Received: 16 December 2020; Accepted: 30 April 2021;

Published: 18 May 2021.

Edited by:

David Ian Walker, University of Alabama, United StatesReviewed by:

Manpreet Kaur Bagga, Partap College of Education, IndiaMatthew David Smith, Buckinghamshire New University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Morgan and Simmons. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Blaire Morgan, Yi5tb3JnYW5Ad29yYy5hYy51aw==

Blaire Morgan

Blaire Morgan Laura Simmons

Laura Simmons