- Department of Psychology, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, United States

Bullying has been recognized as a phenomenon that detrimentally affects the lives of many, and researchers continue to explore its various influences and correlates. We examined the relationship between the global belief in a just world (BJW; a person’s tendency to believe that life is fair and people get what they deserve) and reactions to bullying. Although BJW is undergirded by a justice motive, and although previous research found that global BJW is associated with more negative explicit attitudes toward bullying in the abstract, we hypothesized that strong global BJW beliefs would instead predict more tolerance and less condemnation when participants were presented with specific behaviors that could be construed as bullying. In two vignette-based experiments, global BJW (but not personal BJW), predicted less negative reactions to bullying, and did so regardless of whether the behavior was explicitly labeled as being a case of bullying. Implications of these results are discussed.

Confronted with Bullying when You Believe in a Just World

Bullying is an injustice, and a major societal problem affecting children, adolescents, and adults (Mishna, 2012). For example, the National Center for Education Statistics and Bureau of Justice Statistics (2013) reported that 28% of students in the United States from grades six through twelve had experienced bullying or were feeling bullied; an international study involving 144 nations concluded (based on data collected from 2001 thru 2017) that in any given month, almost one in three students is bullied by a peer at school [United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2019]. One approach to addressing bullying and its prevalence involves shedding light on how people perceive it (e.g., Hunt, 2007)—that is, identifying the variables associated with people recognizing such behavior as bullying, condemning it, and feeling obligated to intervene when it is witnessed. Presumably, the more negatively people evaluate bullying, the less likely they will be to tolerate it in others, let alone engage in such behavior. Thus, correlates of how people construe bullying are of great interest.

A number of investigators (e.g., Dalbert, 2001; Garland et al., 2017; Thornberg and Wänström, 2018) have suggested that just world reasoning—the tendency to believe that good is rewarded, evil is punished, and people get what they deserve—could be associated with people’s tendency to be vigilant for and condemn acts of bullying. Very little research, however, has tested that hypothesis. The current paper describes two studies involving college students examining the relationship between the Belief in a Just World (BJW), an individual difference variable associated with just-world reasoning, and reactions to bullying.

Bullying

While bullying has attracted increased attention among researchers, its definition is not entirely straightforward. Olweus (1993) very broadly defined school bullying as “a student repeatedly exposed to negative actions by one or more students” (p. 9). But he further specified three criteria that had to be met for aggressive behavior to be classified as bullying: the aggression needs to be intentional and cause the victim distress; it needs to be repeated over time; and there must be an imbalance of power between the victim and aggressor. Not all research is guided by these criteria, however. For example, according to Oh and Hazler (2009), “Bullying can be seen in intentionally negative behaviours toward a victim through the use of physical, verbal or social harm” (p. 292), a definition that makes no mention of a power imbalance or repetition over time. To operationalize bullying in our research, we were guided by Oh and Hazler’s definition, but incorporated Olweus (1993) criterion of temporal consistency.

“Bullying” is not just an ambiguous concept for researchers, but also for everyday observers of behavior. Some of this confusion can likely be attributed to whether indirect forms of aggression, such as social ostracism and gossip (Duy, 2013; Juvoven and Graham, 2014), are (or should be) considered bullying. While cases of verbal aggression, social exclusion and peer rejection have each been linked to negative, long-term detrimental psychological effects (Bauman and Del Rio, 2006), observers tend to empathize less with victims of indirect bullying (Duy, 2013), report indirect bullying as being less serious than cases of direct bullying (Garandeau and Cillesson, 2006), and vary in whether they actually identify verbal aggression and social exclusion as bullying (Garandeau and Cillesson, 2006; Naylor et al., 2006).

But many other factors also contribute to the ambiguity of bullying. In some cases, whether an aggressive behavior is intended to cause harm can be ambiguous. What appears to one person as bullying could be seen as playful teasing by another (Kowalski, 2000). Systematic differences in the kinds of behaviors that people construe as bullying also exist. Harger (2009) found that teachers and students reported different conceptualizations of bullying. For teachers, “the focus was placed squarely on the outcomes of student behavior” (p. 80), such as whether children were crying or visibly upset, while children focused more on the perpetrator’s intentions (e.g., bullies “like to make people sad or mad”—p. 47) when assessing whether or not a behavior was bullying (see also Naylor et al., 2006). This paper will examine another possible relevant personal characteristic: the effect that a belief in a just world (BJW) has on people’s readiness to identify aggressive behavior as bullying and to react in a condemnatory way toward it.

Just-World Thinking

The just-world hypothesis, formulated by Melvin Lerner in the late 1960s (Lerner and Simmons, 1966; Lerner, 1980; Montada et al., 1998; see also Hafer and Bègue, 2005), posits a tendency to believe people’s actions are naturally inclined to result in fair and fitting consequences. Just world thinking entails believing that good actions are rewarded, and bad actions punished; it is essentially a cognitive bias to construe events in such a way that people seem to “get what is coming to them.” Although originally conceptualized as a general cognitive bias, since the 1970s research has put increasing emphasis on measuring the belief in a just world (BJW) as an individual difference. Examination of the BJW as a personal disposition began when Rubin and Peplau (1975) developed a 20-item Belief in a Just World Scale. Researchers later voiced concern, however, with its psychometric properties (Ambrosio and Sheehan, 1991; Couch, 1998). This sparked the development of additional BJW measures, including the global BJW measure developed by Lipkus (1991), which has been found to have good internal consistency and external validity across gender and culture (Reich and Wang, 2015). The measure assesses the extent to which individuals, relative to others, generally endorse just world thinking.

Lipkus et al. (1996) also constructed a measure of a personal belief in a just-world (personal BJW—e.g., “I feel that I get what I am entitled to in life;” “I feel that I earn the rewards and punishments I get”), distinct from the global belief in a just-world (global BJW—e.g., “I feel that people get what they are entitled to in life;” “I feel that people get what they deserve”). Those who express high personal BJW scores tend to believe that the world treats them fairly; those with a strong global BJW tend to believe that other people deserve their fates. Measures of these two aspects of just-world beliefs correlate positively (typically, r = 0.5 to 0.6), but are predictive of different phenomena (Lipkus et al., 1996). While personal BJW predicts positive psychosocial adjustment and subjective well-being, “it should correlate weakly or nonsignificantly with measures concerning other people” (Lipkus et al., 1996, p. 674).

The Belief in a Just World and Bullying

Dalbert (2001) argued that “the BJW is indicative of a justice motive and of the obligation to behave fairly” (p. viii). As for the justice motive, it “induces individuals to strive for justice in their own deeds and in their reactions to injustice, whether observed or experienced” (p. 19). This line of reasoning suggests that the BJW (especially global BJW) will be associated with a tendency to be alert to bullying, to negatively evaluate the bully, and perhaps even to intervene when bullying is witnessed. In fact, the first published study examining the relationship between global BJW and how bullying is evaluated—specifically, overall attitudes toward bullying—reported that high global (but not personal) BJW scores were associated with negative attitudes toward bullying (Fox et al., 2010). A number of years earlier, Kristjánsson (2004) had wondered “whether the belief in a just world can and should be encouraged through moral education in the home and at school” (p. 54). Fox et al.’s findings suggest an affirmative answer to Kristjánsson’s question.

Dalbert (2001), however, also acknowledged that if people “cannot restore justice behaviorally or by compensating the victims for their suffering, they will restore justice psychologically,” and “blame victims for inflicting the situation upon themselves” (p. 24). Minimizing the injustice being experienced by people on the receiving end of aggression is an example of what Dalbert (2001) called the “assimilation” function of BJW; in cases where one cannot directly undo or compensate for an injustice, adjusting one’s perceptions of the behavior in question might be the only alternative for maintaining just world beliefs.

Indeed, in his first experiments, Lerner demonstrated this effect by having participants watch a confederate pretending to receive electrical shocks (Lerner and Simmons, 1966). After a certain point, participants would begin to derogate the “victims” of these shocks, and derogation was greatest when the observed suffering was at its most severe. In other words, the participants found a way to construe the situation in such a way that the victims seemed to deserve being treated badly. Other research reveals that Global BJW correlates with harsh attitudes toward the elderly, the poor, the homeless, AIDS victims, murder victims, victims of floods, victims of domestic abuse, victims of traffic accidents, and the mentally ill, as well as with supporting severe punishment for juvenile delinquents (Bègue and Bastounis, 2003; Montada et al., 1998; Sutton and Douglas, 2005).

Thus, higher levels of global BJW could be associated with less negative reactions to bullying episodes, and perhaps less willingness to construe behavior as being bullying in the first place. Viewing the world as a place where people get what they deserve could lead one to conclude that people on the receiving end of aggressive behavior “got what was coming to them”—and blaming the victim is not an uncommon response to bullying (Garland et al., 2017; Thornberg and Wänström, 2018).

What, then, of Fox et al. (2010) findings? Participants in that study did not judge specific instances of aggressive interpersonal behavior. To measure attitudes toward bullying, Fox et al. had participants complete five items from Salmivalli and Voeten’s (2004) Attitudes toward Bullying scale. Specifically, these items (paired with agree-disagree scales) were: “It’s the victim's own fault if they are bullied,” “Bullying makes the victim feel bad,” “One should try to help the bullied victims,” “It’s funny when someone ridicules a classmate over and over again, “and “It’s not bad if you laugh with others when someone is bullied.” In four of these five items, some variant of the word “bully”—a word that has very negative connotations and directly implies an act of injustice—was used. Thus, participants were essentially asked to report how they felt about prototypical, unambiguous episodes of bullying. According to just-world theory, those who score high in the BJW are uncomfortable with the idea that people could experience unjust outcomes, and have a strong desire to see the world as a place where people get what they deserve. Unjust behavior such as bullying would represent a threat to that worldview (Donat et al., 2012). As a result, it would stand to reason that those with a strong BJW would respond negatively to items on the Attitudes toward Bullying scale.

In actual social interaction, however, which behaviors constitute acts of bullying may be subject to interpretation. As noted above, many can be ambiguous in terms of the intentions of the people involved and the severity of their outcomes. When people with high levels of global BJW witness unjust behaviors that could be open to being construed in ways other than “bullying” —especially behaviors that they are powerless to prevent—their desire to avoid concluding that the world is an unfair place could lead them to derogate victims and/or find other ways to excuse the behavior, despite their general feelings about bullying in the abstract.

Research Overview and Hypotheses

In the two studies described here, participants were presented with vignettes describing behaviors (both physical and verbal) that could possibly be construed as examples of bullying.1 Importantly (with the exception of one condition in Study 2), the vignettes never contained the words “bully” or “bullying;” interpretation was left entirely to the participants. A negative reaction to the behaviors described in a vignette was operationalized as (1) indicating that the perpetrator rather than the victim was responsible for the aggressive behavior, (2) condemning the perpetrator’s behavior, (3) expressing anger toward the perpetrator, and (4) empathizing with the victim.

Participants were college-aged individuals; although research on bullying primarily focuses on younger school-aged children (preschool, elementary, and middle school; see Olweus, 2002), bullying persists into adolescence and young adulthood (Asher et al., 2017; Chen and Huang, 2015; Marraccini et al., 2018; see also Coyne, 2011, on bullying in the workplace).

We hypothesized that global BJW would be negatively associated with identifying an interpersonal behavior as being an act of bullying, and negatively associated with reacting negatively to it. Hellemans et al. (2017) provided preliminary support for this hypotheses in a study involving Belgian workers; they found that global BJW was negatively correlated with the perceived severity of an act of bullying. Their research, however, utilized just a single workplace vignette. In addition, their study left open the possibility that same relationship would have been found for the personal BJW.

Personal BJW is a variable with much to contribute to a program of research on bullying. For example, Correia and Dalbert (2008) found that adolescents who scored high on a personal BJW measure were less likely than their peers to bully others. These results were in line with Lerner’s just-world theory: those with a strong personal BJW would expect to face retribution for such a violation of justice. Unlike global BJW, though, personal BJW is not expected to independently relate to beliefs about other people (Lipkus et al., 1996). We did not expect it to have a significant relationship with how people construe and react to bullying.

Study 1

Methods2

Participants A power analysis was conducted based on an effect size of r = 0.2 (midway between small and medium), to determine that 193 participants would be required to reach 80% power. The sample consisted of 202 participants recruited from the online platform Prolific.ac. Because the vignettes all involved adolescents and/or young adults, participants were restricted to those 26 years of age and younger in the United States. They ranged from ages 18–26, and the average age was 21.9 years. One hundred participants identified as male and 95 identified as female; five participants marked “Other” and two marked “Prefer not to answer” in response to the question about gender. One hundred thirty-eight participants (68%) self-identified as White, 23 (11%) as Asian, 17 (8%) as Black, 12 (6%) as Latino/a, and 10 (5%) as “Other” (two participants chose not to answer the question about ethnicity).

Materials and Measures

Vignettes The vignettes created for the study are presented in Appendix A.

Belief in a Just World (Personal) The Fox et al. (2010) 7 item adapted version of the Lipkus et al. (1996) scale measuring the belief that the world is just to oneself was used to measure the personal BJW (e.g., “I feel that the world treats me fairly,” “I feel that I get what I deserve.”) Participants rated items on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree).

Belief in a Just World (Global) The Fox et al. (2010) 7 item adapted version of the Lipkus et al. (1996) scale measuring a global belief in a just world was used to measure the global BJW (e.g., “I feel that the world treats people fairly,” “I feel that people get what they deserve.”) Participants rated items on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree).

Reactions to Bullying After each vignette, participants responded to 5 questions about each of the two protagonists (10 questions overall), all designed to assess the extent to which participants reacted negatively to the bully and his behavior. Each question was paired with a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The midpoint was marked “neither agree or disagree.” Three of these items measured how participants construed and evaluated the behaviors (e.g., “Matt’s behavior toward Chris is unacceptable;” “Chris has instigated this situation;” “Chris is responsible for what is happening to him.”). One item measured participants’ affective reactions (e.g., “I feel angry at Chris”), and another measured participants’ feelings of sympathy, (e.g., “I feel bad for Chris.”). The same ten questions (five focused on the bully, five parallel ones focused on the victim) were presented in a random order after each vignette. Participant responses to both the bully-focused and victim-focused questions were averaged to form a total “Reaction” score for each vignette, with higher scores indicating more negative reactions. (Analyses revealed essentially identical findings for the two types of questions—see the Results section). Responses were reverse coded where appropriate.

Perception of Bullying The item “I believe Scenario [insert number] is an example of bullying” directly examined whether or not the participants viewed the behaviors presented in the vignettes to be bullying. This question was also presented with a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Procedure As part of the informed consent process, participants were told that they would “be asked to read four vignettes involving social situations in which college students may find themselves,” after which they would be asked questions about the vignettes. Participants then completed the scales measuring personal BJW and global BJW (presented in random order). Next participants read the vignettes involving bullying. Each participant read one of two sets of four scenarios (see Appendix A). In each set, two vignettes described verbal behavior and two described physical behavior. The vignettes in each set were presented in a single predetermined random order. Immediately after reading each vignette, participants answered a number of questions to gauge how negatively they reacted to the behavior of the bully.

Participants were then given an opportunity to again look over the four vignettes, and they reported the extent to which they thought each one exemplified bullying. The direct questions about bullying were presented to participants last because they could otherwise have produced demand effects and affected answers to the other questions.

Results

Preliminary Analyses Scale reliability analyses of the items making up the reaction score (anger, sympathy, attribution of responsibility, etc.) justified combining them to form a ten-item measure. Because a total of eight vignettes were used, eight analyses were run, and Cronbach’s α ranged from 0.82 to 0.93. Further supporting the decision to combine all of the items was the finding that responses to the items pertaining to the bullies in the vignettes correlated highly (r = 0.80, p < 0.001) with those pertaining to the victims (after appropriate reverse scoring). In other words, negative/positive thoughts and feelings about the bullies were close to isomorphic to positive/negative feelings about the victims. Overall, then, the reaction score indexed the overall extent to which participants viewed the behavior as unprovoked, unacceptable, and/or upsetting.

The final item regarding the question of bullying was highly correlated with the reaction score (r = 0.53), and could arguably have been included in this reaction score. However, this item was analyzed separately, primarily due its conceptual status. It is the only item that directly captures whether the participants perceived the behavior as “bullying.”

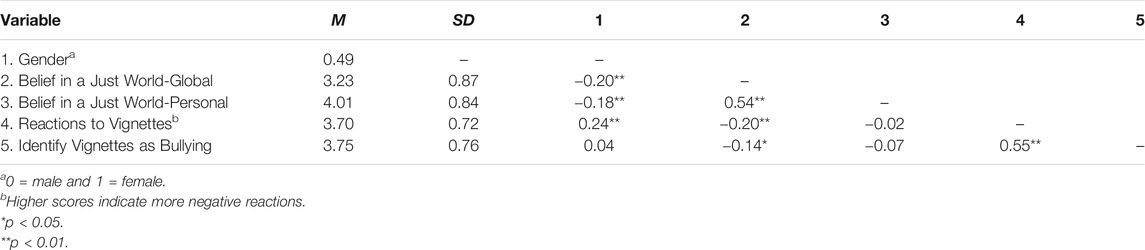

The global (M = 3.23, SD = 0.87) and personal (M = 4.01, SD = 0.84) BJW measures also each showed good internal reliabilities (α = 0.88 and α = 0.86, respectively), and correlated at a predictable level (r = 0.54; see Table 1 for all Study 1 correlations). Regarding the personal BJW, the correlation with reactions to the vignettes neared zero (r = −0.02, p = 0.80). Similarly, the personal BJW did not significantly correlate with the item assessing whether the vignettes were displays of bullying (r = −0.07, p = 0.30). As expected, then, the personal BJW was not related to participants’ responses to the vignettes.

Primary Analyses Overall, a high global BJW significantly correlated with less negative reactions in response to the bullying vignettes; in other words, high scorers attributed more blame to the victims, felt less sympathy for them, and felt less anger toward the perpetrators (r = −0.20, p < 0.01). When the items were broken down into two categories based on role, the results for negative reactions to the aggressors (r = −0.20, p = 0.005) were almost identical to the results (after reverse coding) for negative reactions to the victims (r = −0.18, p = 0.01). Global BJW also significantly negatively correlated with the final item, which assessed whether the vignettes were perceived as displays of bullying (r = −0.14, p = 0.04).

Additional Analyses Female participants reported more negative reactions to perpetrators (and thus more sympathetic reactions to victims; M = 5.82, SD = 0.60) than did male participants (M = 5.49, SD = 0.74; t (193) = 3.39, p = 0.001, d =0 .49). Similar findings have been reported in past studies (Correia and Dalbert, 2008; Fox et al., 2010). But female participants were not significantly more likely than males to identify the behaviors in the vignettes as bullying (for females, M = 5.82, SD = 0.69; for males, M = 5.76, SD = 0.82). Although the gender difference in reactions was not expected to moderate the relationship between global BJW and how participants construed the vignettes, it did have a slight effect. Global BJW significantly negatively correlated with reaction scores among males (r = −0.20, p = 0.04), but did not reach significance among females (r = −0.08, p = 0.46). However, the interaction between global BJW and gender did not reach significance (the R2 change when the interaction was entered into a hierarchical regression was 0.005, p = 0.32).

As already noted, two different sets of four vignettes were used in Study 1, and each participant was presented with only one of the sets. Although the vignettes did vary in their content, they were designed to be conceptually similar. But post-hoc analyses revealed that among participants reading and reacting to the first set, the correlation between global BJW and the “is it bullying” (perception) item was not significant (r = −0.01). Responses to the second set of vignettes were primarily responsible for the negative correlation found between global BJW and the perception of bullying (r = −0.29, p = 0.003). A similar pattern was found for the overall reaction scores (r = −0.32, p = 0.001 for Set 2, r = −0.10, p = 0.30, for Set 1).3 Potential explanations for these differences will be discussed.

Discussion

The findings of Study 1 suggest that those with a high global BJW may have a tendency to excuse and downplay the significance of the bully behavior they witness. They were more likely than other participants to blame and disparage the victims and less likely to express negative feelings about perpetrators. Similarly, global BJW predicted less agreement with the item that assessed whether the vignettes exemplified bullying—indicating that high scorers were less likely to even perceive the behaviors as bullying.

Unexpectedly, global BJW was more highly related to how participants construed one set of vignettes vs. the other. It is possible that differences in the vignettes that extended beyond their ambiguity affected participants’ responses. Prototypical bully victims are shy, anxious, submissive, and physically weak (Olweus, 1993). Overall, the victims in the second set of vignettes arguably fit that description more closely than those in the first set.

Study 2

The results of Study 1 suggest that although people with strong global BJW might condemn bullying in the abstract (Fox et al., 2010), and might, if given an opportunity, more readily come to the assistance of a bullying victim (see Dalbert, 2001), they might also express less outrage at bullying and be less sympathetic to its victims when they have no way of behaviorally restoring justice.

Fox et al.’s discussion of their findings provides an alternative account for those findings, however. They suggested that the nature of the act of injustice—specifically, its severity—is what determines whether a strong belief in a just world will lead people to derogate victims. Fox et al. hypothesized that high BJW is likely to be associated with negative reactions to bullying primarily when people are confronted with acts that are clearly unjust and harmful. Unambiguous, instantly recognizable bullying would be much more difficult to explain away or justify than ambiguous bullying. If so, Study 1’s results might be due to the behavior presented to participants being (by design) somewhat ambiguous.

To address this possibility, Study 2 attempted to disambiguate some of the behaviors and examine how explicit use of the word “bullying” might affect reactions to aggressive behaviors (particularly among those scoring high on global BJW). Study 2 used four vignettes from Study 1, but it also included a second condition in which the aggressive behavior in those vignettes was labeled as being “bullying.” The explicit use of the word “bullying” might disrupt the tendency of those higher global BJW to have more muted negative reactions to the behavior of the perpetrators. This design thus provided another opportunity for the findings and conclusion of past research to conceptually replicate; it was possible that eliminating the vignettes’ ambiguity (thus rendering the behaviors they described more obviously severe) could result in a positive relation between global BJW and negative reactions to bullying.

The goal of this study was to replicate the results of Study 1 (i.e., to replicate the correlation between global BJW and less negative reactions to bullying) and provide a more direct test of the hypothesis that a high global BJW could also lead to more negative reactions to explicit bullying. Fox et al. (2010) hypothesis would be supported by a two-way interaction between global BJW and the mention of “bullying.” More specifically:

1.The findings of Study 1 would be replicated when the vignettes did not explicitly mention “bullying.” Participants with higher global BJW scores should report less of a negative reaction to bullying, and display less of a tendency to label the behaviors as bullying.

2.When the aggressive behavior is explicitly labeled as “bullying,” the nature of such behavior should be unmistakable. If this is the case, those with a high global BJW might now condemn the behavior more harshly than those with a low global BJW.

Methods

Participants The sample consisted of 197 Prolific.ac users (approximately the same as the sample size in Study 1) between 18 and 26 years of age. The average age for participants was 21.8 years. Ninety-seven participants identified as male, and 95 identified as female; three participants marked “Other,” and two marked “Prefer not to answer.” Data from five other participants were dropped; two of these participants had missing data, and another three were dropped because the gender they reported for this study did not match the gender registered for them on the Prolific website.

Procedure and Measures The procedure and measures in Study 1 were identical to those in Study 1 with the following exceptions. All participants were presented with only the four vignettes from Vignette Set 2 (see Appendix A). For half of the participants, however, the aggressive behavior was explicitly labeled as “bullying.” “Pete again nailed Billy in the head” became “Pete continued to bully Billy, nailing him in the head;” “he has no idea how to respond. Jim now makes fun of Nick” became “he has no idea how to respond Jim’s bullying. Jim continues to bully Nick;” “He continues to let Mike know what he thinks” became “He continues to bully Mike, letting him know what he thinks;” and “He puts Justin in a headlock” became “He bullies Justin.” Thus, the mention of “bullying” was a between-subjects variable.

Results

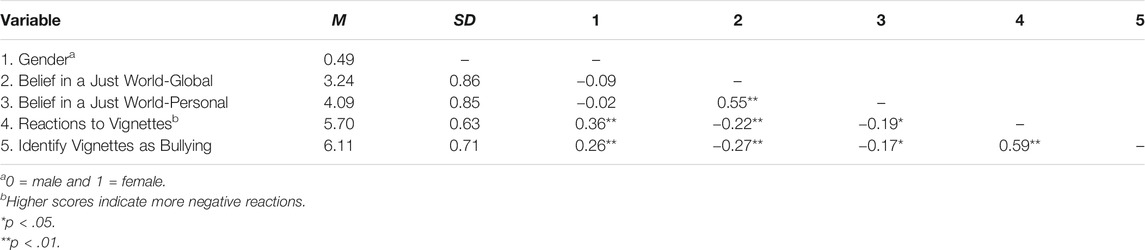

Preliminary Analyses The global (M = 3.24, SD = 0.86) and personal (M = 4.09, SD = 0.85) BJW measures each again showed good internal reliabilities (Cronbach’s α = 0.88 for both). The BJW measures correlated at r = 0.55, p <0 .001 (see Table 2 for all Study 2 correlations). The internal consistencies for the ten items in the vignette questionnaires ranged from Cronbach’s α = 0.74 to α = 0.94 for the eight vignettes.

Differences in the mean bullying ratings (“This is an example of bullying”) between the two conditions indicated that explicit use of the word “bullying” only marginally affected the ambiguity of bullying in the vignettes (for non-labelled vignettes, M = 6.02, SD = 0.71; for labeled vignettes, M = 6.19, SD = 0.71; t (195) = 1.63, p = 0.10, d =0 .23). However, a post-hoc analysis revealed that of 101 participants in the explicit bully labeling condition, 22 provided a “7” rating (the highest number on the scale) for all 4 vignettes; in contrast, of the 96 participants in the non-labelled vignette condition, only 8 did so. A chi-square analysis revealed this difference to be significant, (1, 197) χ2 = 6.90, p = 0.009.

Primary Analyses Global BJW correlated with negative reactions to the vignettes (r = −0.22, p = 0.002), replicating the results of the first study. Unlike in Study 1, in which the personal BJW showed no correlations with any measure related to bullying, the personal BJW significantly negatively correlated with this reaction score in Study 2 (r = −0.19, p = 0.007).4 However, the personal BJW did not significantly relate to reaction scores when controlling for global BJW (r = −0.09, p = 0.21), while the correlation between global BJW and reaction scores still verged on significance (r = −0.13, p = 0.06) when controlling for the personal BJW.

As in Study 1, global BJW also significantly correlated with less agreement to the “This is an example of bullying” items (r = −0.27, p < 0.001). The personal BJW correlated with these items as well, and in the same direction (r = −17, p = 0.02). However, a partial correlation analyses revealed that the personal BJW did not significantly predict this response when controlling for covariance with global BJW (r = −0.03, p = 0.71). Global BJW’s negative correlation remained significant even when controlling for covariance with the personal BJW (r = −0.22, p = 0.002). Thus, the personal BJW’s relation to how one cognitively reacts to bullying appears primarily due to its covariance with global BJW.

Of greater interest was whether global BJW would interact with the use of the term “bullying” to predict how participants would react to and label the vignettes. In the case of reaction scores, that was clearly not the case; in the condition in which the term “bullying” was used in the vignettes, global BJW’s correlation with reaction scores was (r = −0.22, p = 0.03), and in the condition that never used the word “bullying,” it was exactly the same (r = −0.22, p = 0.03). Global BJW was more negatively correlated with labeling behaviors as being “bullying” when the term was not mentioned (r = −0.37, p < 0.001) than when it was mentioned (r = −0.18, p = 0.08), as expected. However, a hierarchical regression analysis revealed that the interaction between Global BJW and condition was not significant (the R2 change when the interaction was entered was 0.007, p = 0.21).

Overall, then, Study 2’s findings replicated those of Study 1. Whether or not participants were encouraged to construe the vignettes as bullying (as opposed to describing some less unjust or severe form of behavior) did not moderate the relationship between global BJW and how the behaviors described were interpreted and evaluated.

Additional Analyses As in Study 1, female participants indicated that they condemned the behavior presented in the bullying vignettes (M = 5.92, SD = 0.57) more so than male participants (M = 5.47, SD = 0.61; t (190) = 5.27, p < 0.001, d = 0.76). Unlike in Study 1, female participants also were significantly more likely than males to identify the behaviors in the vignettes as bullying (for females, M = 6.29, SD = 0.63; for males, M = 5.92, SD = 0.74; t (190) = 3.76, p < 0.001, d = 0.55). To recall, the results of Study 1 suggested that the global BJW might relate more strongly with reactions to bullying among males than among females. In Study 2, however, global BJW was more negatively correlated with reaction scores among female participants (r = −0.25, p = 0.02) than among male participants (r = −0.12, p = 0.24). Thus, across the two studies, the relationship between global BJW and ratings of bullying behavior was not consistently moderated by gender.

General Discussion

Previous analyses of bullying have suggested a role for just world reasoning and attitudes toward bullying, but the evidence has been sparse and inconsistent. In both of the current studies, global BJW (but as expected, not personal BJW) predicted a less unfavorable reaction to the perpetrator’ behaviors. Global BJW also predicted relative disagreement with the notion that the vignettes actually displayed bullying. These results, congruent as they are with the belief that people get what they deserve (and deserve what they get), are consistent with much of the just-world literature (Hafer and Bègue, 2005); for example, Faccenda and Pantaléon (2011) found that those who indicated a high BJW also showed reduced levels of sensitivity to acts of observed injustice.

The attempt to show that the relationship between BJW and reactions to bullying would be moderated by the severity or lack of ambiguity of the behavior was nor successful. It is possible that the relatively pallid nature of behaviors described in vignettes will inevitably make them amenable to subtly different construals. But the possibility also remains that explicit attitudes toward bullying are not a reliable guide to how people will react to specific acts of aggression; indeed, it has long been recognized that explicit self-reports of attitudes can be tenuously related to people’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (Cooper and Croyle, 1984). Thus, these findings are arguably compatible with Fox et al.’s (2010) conclusion that global BJW is associated with more negative evaluations of bullying in the abstract.

These findings also can be reconciled with Dalbert’s (2001) contention that BJW reflects a justice motive—a “striving for justice in one’s own deeds and in one’s reactions to injustices” (p. 3). What they indicate is that if there is no other way for people to either behaviorally or psychologically restore justice when observing the possible victimization of a an individual (or group), as was the case in the current studies, global BJW could motivate them to discount the severity of the behavior, and be more reluctant to label it as an act of bullying. Overall, the accumulated evidence is that the role of BJW in how people react when confronted with bullying is more nuanced than it might first appear.

Limitations

The use of vignettes raises the inevitable question of whether these findings would generalize to real-world scenarios of bullying. When reading vignettes, participants are of course powerless to intervene in the events they describe. There could well be a range of circumstances in which people with high BJW would attempt to disrupt or prevent the bullying—that is, restore justice behaviorally rather than psychologically. To shed light on this issue, future research, even studies using vignettes, could include measures of participants’ behavioral intentions.

Another limitation of the current set of studies is that neither included any vignettes with female victims or perpetrators. The gender of participants did appear to influence how they responded to the vignettes. However, it is impossible to determine if this was due to the participants’ gender alone, or if the gender incongruity between participant and victims somehow contributed to the observed effect. Thus, future research should include vignettes depicting female characters in addition to vignettes depicting male characters.

Because all of the participants were from the United States, the extent to which the results are culturally specific cannot be determined. Some research has found the correlates of beliefs in a just world to vary cross-culturally (e.g., Wu et al., 2011).

Finally, the fact that participants completed the BJW measures immediately before reading and responding to the vignettes leaves open the possibility that the differences between the participants high and low in global BJW might not have emerged spontaneously—that is, they might be dependent on having just world beliefs recently primed (see discussion of this issue by Bargh and Tota, 1988). Future research should measure BJW a number of days or weeks before the presentation of the experimental materials—ideally in another context and along with a number of other measures to better disguise the focus of the investigation.

Potential Implications

Could these studies’ findings have an implications for intervention approaches to school and workplace bullying (e.g., Merrell et al., 2008)? More specifically, should BJW be encouraged and cultivated, or instead be discouraged (Kristjánsson, 2004)? The findings of the current two studies cannot provide a definitive answer to that question, but do suggest one important consideration. They indicate that in contexts in which it is not clear to individuals how to intervene in bullying behavior, and/or contexts in which individuals judge that there will be costs to doing so, global BJW will be counterproductive. Such beliefs could potentially lead people to downplay the severity of bullying behavior and engage in victim-blaming.

Nonetheless, it is reasonable to hypothesize that anti-bullying programs highlighting the potential pitfalls of the just-world effect might help bolster a link between anti-bullying attitudes and behavior. To illustrate this point, imagine that a student is educated about bullying and believes it is wrong. When that student sees a classmate getting bullied, he or she still could dismiss it either by derogating the victim or by downplaying its severity. In other words, the student would be justifying acting in a manner that clashes with his or her moral standards—essentially, engaging in what Bandura (2002) would call moral disengagement, a mental maneuver that has been found to predict bullying among boys (Gini, 2006). If students are made aware of the just-world phenomenon, however—and of how it might primarily serve the function of helping them feel less prone to getting bullied themselves—they might be more likely to catch themselves in the act of justifying the behavior, and thus be more likely to act in accordance with anti-bullying attitudes. Presumably, this would involve a greater likelihood of helping the victim. Thus, teaching people about the just-world effect could provide one overlooked remedy to the disappointing impact of anti-bullying campaigns.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://osf.io/qjgwz/?view_only=ddbdaaf0b733477199935060ddc3e859

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Syracuse University IRB, Office of Research Integrity and Protections. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

DV developed the original study idea, ran the experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the first draft. LN helped conceptualize the study, assisted with data analysis, and contributed significantly to the writing of the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1Given the lack of a concrete hypothesis in regards to gender and the effects of the study, all of the perpetrators and victims were of the same gender (male) to simplify the design.

2All vignettes, and data for both studies, can be accessed at https://osf.io/qjgwz/?view_only=ddbdaaf0b733477199935060ddc3e859

3The relationship between personal BJW and how the vignettes were construed was not similarly moderated by Set; all of those correlations remained insignificant.

4Chapin and Coleman (2017), in a highly powered study (n = 1,593 10–18-year-olds), also found that the relationship between the questionnaire item “I feel that many of the kids who are picked on bring it on themselves by the way they dress or act” and personal BJW was statistically significant.

References

Ambrosio, A. L., and Sheehan, E. P. (1991). The Just World Belief and the AIDS Epidemic. J. Soc. Behav. Personal. 6, 163–170.

Asher, Y., Stark, A., and Fireman, G. D. (2017). Comparing Electronic and Traditional Bullying in Embarrassment and Exclusion Scenarios. Comput. Hum. Behav. 76, 26–34. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.037

Bandura, A. (2002). Selective Moral Disengagement in the Exercise of Moral agency. J. Moral Educ. 31, 101–119. doi:10.1080/0305724022014322

Bargh, J. A., and Tota, M. E. (1988). Context-dependent Automatic Processing in Depression: Accessibility of Negative Constructs with Regard to Self but Not Others. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 54 (6), 925–939. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.925

Bauman, S., and Del Rio, A. (2006). Preservice Teachers' Responses to Bullying Scenarios: Comparing Physical, Verbal, and Relational Bullying. J. Educ. Psychol. 98, 219–231. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.219

Bègue, L., and Bastounis, M. (2003). Two Spheres of Belief in justice: Extensive Support for the Bidimensional Model of Belief in a Just World. J. Personal. 71, 435–463. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.7103007

Chapin, J., and Coleman, G. (2017). Children and Adolescent Victim Blaming. Peace Conflict: J. Peace Psychol. 23, 438–440. doi:10.1037/pac0000282

Chen, Y.-Y., and Huang, J.-H. (2015). Precollege and In-College Bullying Experiences and Health-Related Quality of Life Among College Students. Pediatrics 135, 18–25. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-1798

Cooper, J., and Croyle, R. T. (1984). Attitudes and Attitude Change. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 35, 395–426. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.35.020184.002143

Correia, I., and Dalbert, C. (2008). School Bullying: Belief in a Personal Just World of Bullies, Victims and Defenders. Eur. Psychol. 13, 249–254. doi:10.1027/1016-9040.13.4.248

Couch, J. V. (1988). Another Psychometric Evaluation of the Just World Scale. Psychol. Rep. 82, 1283–1286. doi:10.2466/PR0.82.3.1283-1286

Coyne, I. (2011). Bullying in the Workplace in Bullying in Different Contexts. Editors C. P. Monks, and I. Coyne (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 157–184. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511921018.008

Dalbert, C. (2001). The justice Motive as a Personal Resource: Dealing with Challenges and Critical Life Events. Critical Issues in Social justice. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-3383-9

Donat, M., Umlauft, S., Dalbert, C., and Kamble, S. V. (2012). Belief in a Just World, Teacher justice, and Bullying Behavior. Aggr. Behav. 38, 185–193. doi:10.1002/ab.21421

Duy, B. (2013). Teachers’ Attitudes toward Different Types of Bullying and Victimization in Turkey. Psychol. Schs. 50, 987–1002. doi:10.1002/pits.21729

Faccenda, L., and Pantaléon, N. (2011). Analysis of the Relationships between Sensitivity to Injustice, Principles of justice and Belief in a Just World. J. Moral Educ. 40, 491–511. doi:10.1080/03057240.2011.627142

Fox, C. L., Elder, T., Gater, J., and Johnson, E. (2010). The Association between Adolescents' Beliefs in a Just World and Their Attitudes to Victims of Bullying. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 80, 183–198. doi:10.1348/000709909X479105

Garandeau, C. F., and Cillessen, A. H. N. (2006). From Indirect Aggression to Invisible Aggression: a Conceptual View on Bullying and Peer Group Manipulation. Aggression Violent Behav. 11, 612–625. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2005.08.005

Garland, T. S., Policastro, C., Richards, T. N., and Miller, K. S. (2017). Blaming the Victim: University Student Attitudes Toward Bullying. J. Aggression, Maltreat. Trauma. 26, 69–87. doi:10.1080/10926771.2016.1194940

Gini, G. (2006). Social Cognition and Moral Cognition in Bullying: What's Wrong?. Aggr. Behav. 32, 528–539. doi:10.1002/ab.20153

Hafer, C. L., and Bègue, L. (2005). Experimental Research on Just-World Theory: Problems, Developments, and Future Challenges. Psychol. Bull. 131, 108–128. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.1.128

Harger, B. (2009). Interpretations of Bullying: How Students, Teachers, and Principals Perceive Negative Peer Interactions in Elementary Schools. Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (3378353).

Hellemans, C., Dal Cason, D., and Casini, A. (2017). Bystander Helping Behavior in Response to Workplace Bullying. Swiss J. Psychol. 76, 135–144. doi:10.1024/1421-0185/a000200

Hunt, C. (2007). The Effect of an Education Program on Attitudes and Beliefs about Bullying and Bullying Behaviour in Junior Secondary School Students. Child. Adolesc. Ment. Health 12, 21–26. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2006.00417.x

Juvonen, J., and Graham, S. (2014). Bullying in schools: The power of bullies and the plight of victims. Annual Review of Psychology 65, 159–185. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115030

Kowalski, R. M. (2000). “I Was Only Kidding!”: Victims’ and Perpetrators’ Perceptions of Teasing. Pers Soc. Psychol. Bull. 26, 231–241. doi:10.1177/0146167200264009

Kristjánsson, K. (2004). Children and the Belief in a Just World. Stud. Philos. Educ. 23, 41–60. doi:10.1023/B:SPED.0000010695.02262.fb

Lerner, M. (1980). The Belief in a Just World: A Fundamental Delusion. New York: Plenum. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-0448-5

Lerner, M. J., and Simmons, C. H. (1966). Observer's Reaction to the "innocent Victim": Compassion or Rejection? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 4, 203–210. doi:10.1037/h0023562

Lipkus, I. M., Dalbert, C., and Siegler, I. C. (1996). The Importance of Distinguishing the Belief in a Just World for Self versus for Others: Implications for Psychological Well-Being. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 22, 666–677. doi:10.1177/0146167296227002

Lipkus, I. (1991). The Construction and Preliminary Validation of a Global Belief in a Just World Scale and the Exploratory Analysis of the Multidimensional Belief in a Just World Scale. Personal. Individual Differences 12, 1171–1178. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(91)90081-L

Montada, L., and Lerner, M (1998). Responses to Victimizations and Belief in the Just World. New York: Plenum. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-6418-5

Marraccini, M. E., Brick, L. A. D., and Weyandt, L. L. (2018). Instructor and Peer Bullying in College Students: Distinct Typologies Based on Latent Class Analysis. J. Am. Coll. Health 66, 799–808. doi:10.1080/07448481.2018.1454926

Merrell, K. W., Gueldner, B. A., Ross, S. W., and Isava, D. M. (2008). How Effective Are School Bullying Intervention Programs? A Meta-Analysis of Intervention Research. Sch. Psychol. Q. 23, 26–42. doi:10.1037/1045-3830.23.1.26

Mishna, F. (2012). Bullying: A Guide to Research, Intervention, and Prevention. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199795406.001.0001

National Center for Education Statistics and Bureau of Justice Statistics (2013). School Crime Supplement. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2013/2013329.pdf

Naylor, P., Cowie, H., Cossin, F., Bettencourt, R., and Lemme, F. (2006). Teachers' and Pupils' Definitions of Bullying. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 76, 553–576. doi:10.1348/000709905X52229

Oh, I., and Hazler, R. J. (2009). Contributions of Personal and Situational Factors to Bystanders' Reactions to School Bullying. Sch. Psychol. Int. 30, 291–310. doi:10.1177/0143034309106499

Olweus, D. (2002). A Profile of Bullying at School. Educ. Leadersh. 60 (6), 12–17. doi:10.26226/morressier.5b5f433db56e9b005965bee8

Reich, B., and Wang, X. (2015). And justice for All: Revisiting the Global Belief in a Just World Scale. Personal. Individual Differences 78, 68–76. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.01.031

Rubin, Z., and Peplau, L. A. (1975). Who Believes in a Just World? J. Soc. Issues 31, 65–89. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1975.tb00997.x

Salmivalli, C., and Voeten, M. (2004). Connections between Attitudes, Group Norms, and Behaviour in Bullying Situations. Int. J. Behav. Develop. 28, 246–258. doi:10.1080/01650250344000488

Sutton, R. M., and Douglas, K. M. (2005). Justice for All, or Just for Me? More Evidence of the Importance of the Self-Other Distinction in Just-World Beliefs. Personal. Individual Differences 39, 637–645. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.02.010

Thornberg, R., and Wänström, L. (2018). Bullying and its Association with Altruism toward Victims, Blaming the Victims, and Classroom Prevalence of Bystander Behaviors: A Multilevel Analysis. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 21, 1133–1151. doi:10.1007/s11218-018-9457-7

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2019). Behind the Numbers: Ending School Violence and Bullying. Paris, France: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Wu, M. S., Yan, X., Zhou, C., Chen, Y., Li, J., Zhu, Z., et al. (2011). General Belief in a Just World and Resilience: Evidence from a Collectivistic Culture. Eur. J. Pers 25, 431–442. doi:10.1002/per.807

Appendix A

Vignettes, Study 1

Vignette Set 1

[Scenario 1] (Physical)

Mark tells Eric that he’s a fan of professional wrestling. Eric replies that he is too, and gets so enthusiastic about the topic that he starts practicing his wrestling moves on Mark. Mark is not too thrilled about this, and asks Eric to stop, but it takes a while for Eric to finally release Mark. Now every time Eric sees Mark he cries out “There’s my wrestling buddy,” and starts roughhousing with Mark. After a while Mark starts anxiously avoiding Eric, because Eric keeps persisting with this behavior—which explains all of Mark’s bruises.

[Scenario 2] (Verbal)

Chris lives in your dorm. One day, Chris mentions to Matt, a boy who lives across the hall, that he got a new car. A Ferrari. Matt questions this, and Chris grins, responding, “Want to see it? I’ll let you sit in it—and maybe if you’re lucky, I’ll even let you drive it.” Matt fires back, “You lost your dignity when you started driving your dad’s car. Keep this up, and you’ll lose something else.” From then on, Matt regularly mocks Chris when they pass in the hallway.

[Scenario 3] (Physical)

Joe lives a few doors down from you. One day, you see Joe leaving the library. Another guy named Tom, who lives on your floor, sidesteps a group of people to approach Joe. Joe doesn’t seem to notice. Tom smirks and roughly bumps into Joe. Joe tries to ignore this as he moves past Tom, but to his dismay, Tom wordlessly shoves Joe every time he spots him on campus.

[Scenario 4] (Verbal)

Jake is a student in your history class. One day, the professor announces that everyone must present on a topic in front of the class. Jake looks terrified, and today’s not his lucky day. He is chosen to go first. As Jake walks to the podium, a classmate named Doug notices sweat stains under Jake’s arms. Doug smiles and remarks, “Looks like you should’ve worn black today, little guy.” Jake quickly glances at the stains under his arms and looks alarmed. After Jake finishes his presentation, Doug looks him in the eye and says “You are so sad.” For the rest of the semester, Doug keeps making similar comments to Jake.

Vignette Set 2

[Scenario 5] (Physical)

Billy hated going to gym class, and was especially unhappy when the gym teacher decided the students should play dodge ball for a few weeks. During the first game, Pete, a player on the other team, hit Billy squarely on the side of the head with the ball. Billy saw stars. The next time the class met, right after the game began, Pete again managed to hit Billy in the head with a powerful throw. Billy asked Pete if he had done so on purpose, but Pete just looked annoyed and said “Look, this is how the game is played.” On the third day of dodgeball, Pete again nailed Billy in the head 30 s into the game.

[Scenario 6] (Verbal)

Nick is a student in your psychology class. He silently sits alone in the back corner throughout the entire course. Even during group activities, Nick sticks to himself. A classmate named Jim approaches Nick and asks if he’d like to join his group. Nick simply replies, “No”. Jim then asks Nick if that was first word he managed to utter in his life. Nick looks up, startled; he has no idea how to respond. Jim now makes fun of Nick every day before class starts.

[Scenario 7] (Verbal)

Mike lives a few doors down from you. One day, you see Mike approaching the dorm. Another neighbor from your floor named Aiden is just leaving the dorm and sees Mike. Aiden waves at Mike, but Mike does not respond. As the two pass each other, Aiden shouts at Mike, saying “Are you too much of a big shot to acknowledge me? With a face like that, you should consider yourself lucky that I even talk to you.” Mike ignores this comment, but as the year goes by, Aiden won’t let it go. He continues to let Mike know what he thinks of his personality and looks when the two encounter each other.

[Scenario 8] (Physical)

Justin is a student in your history class. He sits by himself, and spends most of his time doodling in his notebook. One day, a classmate named Sam notices one of Justin’s drawings: a beautiful woman. He laughs out loud and grabs Justin’s notebook. When Justin pleads for him to give his notebook back, Sam shoves him to the ground. Sam’s behavior toward Justin doesn’t stop there. He puts Justin in a headlock every day before class.

Keywords: bullying, belief in a just world, just world theory, aggression, violence

Citation: Voss D and Newman LS (2021) Confronted with Bullying when You Believe in a Just World. Front. Educ. 6:634517. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.634517

Received: 27 November 2020; Accepted: 02 June 2021;

Published: 24 June 2021.

Edited by:

H. Colleen Sinclair, Mississippi State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Christa Boske, Kent State University, United StatesNancy Longnecker, University of Otago, New Zealand

Copyright © 2021 Voss and Newman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Leonard S. Newman, bHNuZXdtYW5Ac3lyLmVkdQ==

David Voss

David Voss Leonard S. Newman

Leonard S. Newman