- Educational Administration & Foundations Illinois State University, Illinois State University, Normal, IL, United States

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic took the world into crisis. We saw the virus alter a multitude of spheres worldwide, including our healthcare, economies, politics, social processes, and education. In fact, the impact of COVID-19 on educational administration took our leaders into forced emergency measures. Our study aims to better understand the experiences of educational administrators under crisis to ascertain what might be learned on how educational institutions may better respond to the crisis in the future. These stories were collected from educational leaders, both from K-12 and higher education, throughout the United States. In brief, this article is framed in the theory and literature associated with the complexity of leading in times of crisis. We explore the resiliency of leadership forged in crisis and the rethinking of administrative as administration as a caring and trustful acts. Our research began as a hermeneutic phenomenological interview study, but transitions into a two-round project, where after the first interview, participants were invited to share some images that typify and speak to the experiences being educational administrators during this time. We are engaged in sensitive topics that are ongoing and changing. Moreover, throughout, we are asking for images that speak to their experiences. Across both K-12 and higher education, our results indicated varied responses, from immediate to delayed administrative action. However, albeit they looked contextually different, there are clear indications the participants valued continuous, transparent communication, authentic caring, trust, and agency. In our discussion, we elaborate on the distinction between what the institutional response was as compared to what was valued by our educational leaders. Finally, as a contribution to the field, we seek to provide guidance for future administrators in crisis based on our own experiences and the recommendations provided by our educational leaders.

Introduction

From January 10–12, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) published a comprehensive package of guidance documents for countries, covering topics related to the management of an outbreak of the novel coronavirus. Among other topics, this initial guidance included prevention and control, risk communication and community engagement, and travel advice (World Health Organization, 2020). At the same time, on January 11, 2020, the Chinese media reported the first death from the novel coronavirus (World Health Organization, 2020). Then, on January 30th, the Director-General of WHO “declared the novel coronavirus outbreak a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC), WHO's highest level of alarm” (World Health Organization, 2020). On February 11th, in order to avoid inaccuracy or stigma to a certain geographic area, animal, or group of people, WHO announced that the disease caused by the novel coronavirus would be named COVID-19 (World Health Organization, 2020). Finally, on March 11th, WHO determined the COVID-19 outbreak was now considered a pandemic. The Director-General stated, “we cannot say this loudly enough, or clearly enough, or often enough…all countries can still change the course of this pandemic…detect, test, treat, isolate, trace, and mobilize their people in the response” (World Health Organization, 2020).

In the United States (U.S.), on January 21, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first case of the novel coronavirus in the U.S. in the state of Washington. As reported, the patient returned from Wuhan, China, where the outbreak of the novel coronavirus had been ongoing since December 2019 (Centers for Disease Control Prevention, 2020a). Then, on January 30th, the CDC confirmed the novel coronavirus had spread between two people in the U.S., representing the first instance of person-to-person spread stateside (Centers for Disease Control Prevention, 2020b).

By mid-March, 2020, U.S. officials reported more than 10,750 confirmed cases of the COVID-19 viral disease and over 150 deaths (Dwyer, 2020). Arguably, as a result, the White House began daily press briefings on March 16th. At this time, the Corona Virus Taskforce (not to be confused with Space Force) was appointed by President Trump. Given these daily press briefings to reassure the American public that the US government was indeed doing their best to protect their citizens from the spread of COVID-19, President Trump took up 60% of the time that officials spoke, according to a Washington post-analysis of annotated transcripts from Factba.se, a data analytics company (as cited in Bump and Parker, 2020). On April 26th, President Trump offered politically affiliated attacks and boasts on unfounded evidence of how well his administration was doing to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, but he did not do was offer any empathy (Bump and Parker, 2020). In fact, on this day, 2,081 Americans were reported dead from COVID-19, and more than 54,000 Americans had perished since the pandemic began (Bump and Parker, 2020).

In order to mitigate the community spread of COVID-19, U.S. states and territories moved to stay-at-home orders and other mandates to contain movement within their immediate communities. In fact, from March 1 to May 31, 2020, in total, 42 U.S. states and territories issued stay-at-home orders, affecting 2,355 (73%) of 3,233 U.S. counties. “The first territorial order was issued by Puerto Rico (March 15) and the first state order by California (March 19). Eight jurisdictions issued only an advisory order or recommendation to stay home, and six did not issue any stay-at-home orders” (Moreland et al., 2020). These stay-at-home orders impacted every facet of our lives, including our places of employment and the abrupt closings of educational institutions.

Pivoting to the impact of COVID-19 on the educational landscape, at the same time Hong Kong returned to remote learning (Chor, 2020), on July 13, 2020, the Los Angeles Unified School District, the second largest U.S. school district, and so many other US K-12 school districts reported they will start the school year online (Hubler and Goldstein, 2020). Simultaneously, major international universities transitioned to mostly remote workspaces and online learning, as well.

Nearly 3 months later, on July 21, 2020, contrary to WHO guidance, President Trump continued to mislabel COVID-19 as “the China virus,” during a press conference given solely on his own, with his Coronavirus Task Force noticeably absent. In his press conference, the President downplayed the impact of the pandemic on American lives by comparing it to a global problem but made a rare statement on an uncertain future ahead (Gittleson et al., 2020). He stated, “it will probably, unfortunately, get worse before it gets better. Something I don't like saying about things but that's the way it is. It's the way – it's what we have. You look over the world. It's all over the world. And it tends to do that” (Gittleson et al., 2020). Days later, on July 23rd, the CDC released new resources and tools to support schools (Centers for Disease Control Prevention, 2020c).

Nonetheless, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. government continues an aggressive campaign to force educators and students back into the classroom. The politicization of the COVID crisis prioritizes the economy and partisan re-elections as more important than the health and safety of students and educators of the country (DeMartino and Weiser, DeMartino and Weiser, in-press). However, there are educational administrators doing their best to support their communities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Given these unprecedented events, the purpose of this study is to better understand the experiences of educational administrators during the COVID pandemic that began in early 2020. Our study aims to better understand the experiences of educational administrators under an extreme crisis to ascertain what might be learned on how educational institutions may better respond to the crisis in the future. This article is framed in the theory and literature associated with the complexity of leading in times of crisis. We explore the resiliency of leadership forged in crisis (Hutson and Johnson, 2016; Koehn, 2019) and the rethinking of administrative actions (Sergiovanni, 1994; Stefkovich and Begley, 2007) as caring (Noddings, 2002; Smylie et al., 2016) and trustful acts (Wahlstrom and Louis, 2008; Kutsyuruba and Walker, 2015). Furthermore, the findings from this hermeneutic phenomenological interview and photovoice (Wang and Burris, 1997) study are prioritized by the needs of the school, college, and universities as expressed by our educational administrators, including communicative action, caring and trust, and agency. Then, the discussion pivots to the distinction between what the institutional response was as compared to what was valued by our educational leaders. Finally, as a contribution to the field, the authors provide guidance for future administrators in crisis based on our own experiences and the recommendations provided by our educational leaders.

Theory and Literature

Educational institutions face a complex set of challenges, ranging from bureaucratic policy climates, budgetary concerns, tragedy, violence, and poverty. Given these challenges and other crises, educational leaders are expected to navigate these pools while offering meaningful communities of teaching, learning, and being (Truscott and Truscott, 2005). Educational leaders are unable to control these challenges, but they are able to provide responses that can lead to positive outcomes in schools and communities (Sutherland, 2017). In times of crisis or change, it is important to consider rethinking administration as a caring and trusting act as these facets of leadership are resources that can lead to the continuation of teaching, learning, and flourishing in educational institutions.

Leadership in Crisis

Whether an environmental disaster, random act of violence, or a pandemic, the anatomy of a crisis remains the same. Leadership in crisis is prompted by the trigger event, an unusual event in which the emergency response is not existent or damaged; the mitigation, the efforts used to help prevent or reduce the effects of the crisis; preparation, the readiness of emergency measures; response, or the immediate emergency actions; and recovery, the reconstruction of the area or organization (Kapucu and Van Wart, 2008). Given the anatomy of such events, Kapucu and Van Wart (2008) developed leadership in crisis competencies, including leadership actions, such as decisiveness, flexibility, communication, problem-solving, innovative and creative systems of thoughts, planning and organizing of personnel, motivation, team building, scanning the environment, strategic planning, networking and partnering, and decision-making.

Similarly, Hutson and Johnson (2016) explained leaders in crisis innately know to take care of the physical safety of the people involved followed by a focus on the spiritual, emotional, and psychological care of the same human beings. They called this Helpful Help. Beginning with the absence of heroic leadership, Helpful Help begins with the tasks of securing safety, providing aid, and making repairs, and proceeds from there. By challenging a traditional notion of leadership to be in charge in favor of offering and receiving humanity, “the healing leader works alongside others in the organization, not solely from a position of power or authority. Recovery can't be commanded, but it can be supported” (p. 61). Along the same lines, leaders also suffer during the crisis. Hutson and Johnson (2016) noted that leaders might be consumed with dismay, regret, and accusations of failed leadership actions. Through these shared human struggles, Helpful Help comingles and nurtures as mutual and reciprocal support to attest that these are shared concerns unified by a common purpose and care for one another.

Leaders in crisis must also be aware of the language they use to communicate during these challenging times. According to Hutson and Johnson (2016), “when leaders say they are in charge of situations that we perceive to be out of control, we know we're being protected or played. Your words matter and your implicit messages matter even more” (p. 19). For leaders, it is important to relay truthful, consistent, timely, and empathetic messages to their communities in crisis. Without these communicative interventions, communities suffer from acute fear and will act on that fear, unless the leader rapidly mitigates these fears (Hutson and Johnson, 2016). Furthermore, leaders in crisis “need to distance themselves from prevailing frights and fantasies; they need independence in thought, feeling, and deed as well as the courage to tell the truth” (p. 24). In addition to effective communication and fear mitigation, leadership in a crisis is dependent on care and trust.

Caring and trust in leadership are foundational when experiencing a crisis. Hutson and Johnson (2016) explained “when leaders care about others, it makes all the difference. Followers will care right back—for each other, for their leaders, and for themselves. Without trust, a leader is a captain without a ship, a crisis reporter with no one listening” (p. 26). Furthermore, in times of crisis, lack of trust can be caused by either a concern for the competence of others or concern about their motives (Kapucu and Van Wart, 2008, p. 734). In order to have positive outcomes after the crisis, Sutherland (2017) explained “a foundation of care and trust for the organization and leadership on the individual, stakeholder, and community levels. Whatever the outcomes may be, change occurs as a result of a crisis, and school leaders stand at the helm during change” (p. 4). As an extension of the importance of caring and trust during times of crisis, the authors pivot to educational administration as a caring and trusting act.

Rethinking Administration as a Caring and Trusting Act

When rethinking educational administration as a community, leaders and stakeholders share common place, sentiments, and traditions and form a tightly knit web of meaningful relationships. Langford et al. (2017) argue reasserting care within the institutional context must inform policy and practice. Their argument is grounded in four premises: “(1) care is a universal and fundamental aspect of all human life, (2) care involves more than basic custodial activities, (3) care practices can be evaluated, and (4) care must be central to democratic deliberation of policies” (Langford et al., 2017, p. 311–312). Furthermore, they conclude these premises offer new possibilities for educators to (re)claim institutional care as integral to the practices and policies embedded with schools, colleges, and universities (Langford et al., 2017). Given the institutional priority to center care within educational institutions, it is important to define communities of care.

By definition, Sergiovanni (1994) argues “communities are collections of individuals who are bonded together by natural will and who are together bound to a set of shared ideas and ideals. This bonding and binding are tight enough to transform them from a collection of Is into a collective we” (p. 218). These educational community relationships are primarily grouped between teachers and leaders, teachers and students/parents, parents and schools, students and teachers, and between colleagues (Tschannen-Moran, 2014; Sutherland, 2017). Furthermore, rethinking administration as a caring and trusting act begins with taking into account the voices, wellness, and safety of the entire school community. According to Stefkovich and Begley (2007) administrative caring and trust “begins with the assumption that school officials will engage in active inquiry and self-reflection in order to make decisions that are truly in the best interests of the student rather than … self-serving or merely expedient” (p. 220–221). In higher education, both relational and caring teaching resonates with statements endorsing care for students, responsiveness and caring faculty, and caring philosophies oriented toward inclusion and empowerment (Walker-Gleaves, 2019). As such, it is important to consider how caring and trust manifests in educational communities, and how the actions of educational administrators support the mission of institutional care.

Caring

Caring in administrative leadership is central both in academic and social support. The ethic of care offers a perspective to respond to complex problems faced by educational leaders in their educational institutions. Noddings (1991) stated that the first job of educational institutions is to care for our children and students. It is the duty of institutions to place care at the top of their (re)envisioned educational hierarchy. In fact, Stefkovich and Begley (2007) noted advocates for “the use of the ethic of care, students are at the center of the educational process and need to be nurtured and encouraged, a concept that likely goes against the grain of those attempting to make “achievement” the top priority” (p. 16). Furthermore, Noddings (1991) noted “caring is the very bedrock of all successful education and … contemporary schooling can be revitalized in its light” (p. 27). This bedrock serves as the foundation for the definition of caring in schools.

Smylie et al. (2016) defined caring in schools as leadership that itself is caring and cultivates caring throughout the school community. In educational institutions, leaders attended to caring to strengthen their relationships among their community members. As nurturing leaders, acts of caring modeled kind, moral, and productive standards (DeMartino, 2021). Caring leadership is used to resolve dilemmas followed by the need to revise decision-making if it does not meet the needs of the community, as well. Marshall et al. (1996) stated caring leadership was the “moral touchstone…[involving] fidelity to relationships with others that is based more than just personal liking or regard… [and emphasizing the] responsibility to others rather than to rights and rules” (p. 277–278). Likewise, Stefkovich and Shapiro (2003) conducted research with their educational leadership doctoral cohort and graduates. Their results indicated the need for communities of care, concern, and connectedness among members and an awareness of equity and diversity. Lastly, Louis et al. (2016) argued that caring in schools contributes to the development of more effective adult cultures and to student learning. Given the vastness of caring leadership, caring as authenticity and caring as support will be explored.

Caring as authenticity requires openness, transparency, and genuineness (Noddings, 1991). Fairholm and Fairholm (2000) agreed with Noddings's assertion by stating “when sensitivity is missing in the relationship, leaders impede trust” (p. 105). In educational institutions, bonds between caring administration and the greater community are built on honest and straightforward communicative and physical actions. As such, when considering the role of adults when they feel cared for by their administration, Louis et al. (2016) noted they feel “more equitable and transparent allocation of resources to support learning for all students may be a foundation for creating a school culture that is both professionally vibrant (a learning community) as well as meaningful and socially just” (p. 335). Given authentic and transparent caring in both communicative and physical administrative action, caring as support shields the school community from potential threats.

Caring as support is attention to establishing a safe and secure environment for learning (Christle et al., 2005). Caring leadership prioritizes the safety of the school environment for all stakeholders. Both personal safety and emotional safety are concerning for caring leaders. Accordingly, Louis et al. (2016) noted “that principal caring also creates a climate of personal safety, in which the risks associated with discussing how best to change classrooms and teacher instructional strategies to meet the needs of a more diverse student body are lessened” (p. 335). Protective factors by providing a positive and safe learning environment are essential for caring leaders. Since they are cared for, valued, and attended to, caring leadership leads to trust building among the school community members.

Trust

Creating, maintaining, and sustaining trust in educational institutions builds the leader's capacity to respond to the crisis in schools and universities. As such, Noonan et al. (2008) identified five facets of trust between school leadership and the greater school community as benevolence, or the acts of kindness, well-meaning, and vulnerability; honesty aligned with integrity; openness, from vulnerability to increased trust; reliability, or consistent and predictable leadership behaviors; and competence, the ability to perform leadership tasks as required. Similarly, Tschannen-Moran and Hoy (2000) stated “trust is one party's willingness to be vulnerable to another party based on the confidence that the latter party is benevolent, reliable, competent, honest, and open” (p. 556). According to Sutherland (2017), “benevolence is the belief that the other has my best interest in mind. Reliability is the belief that the other will come through for me. Competence is the belief that the other is capable of accomplishing a given task. Honesty is the belief that the other will be forthright with information and do what is right. Openness is the belief that the other will share accurate and needed information” (p. 3). These frameworks serve as a model for building trust between leadership and other stakeholders, but trust building goes both ways. In order to facilitate trust-building processes in an organization, leaders must trust their stakeholders to make positive contributions to the community.

Principal trust and respect for their faculty and staff, including personal regard, professional competence, and integrity-based actions, are integral pieces to the trust-building puzzle (DeMartino, 2021). In fact, Louis and Murphy (2017) noted “where principals trust their teachers, our study suggests that teachers are more likely to attribute a relational form of caring in return” (p. 118). Also, Kutsyuruba and Walker (2015) discussed the need to establish, maintain, and sustain trust was imperative for school leaders to exercise their moral agency and ethical decision-making. Given the different facets of trust, Mishra (1996) offered a model that represents constructive responses to the crisis as related to trust in the educational community.

Mishra (1996) based their model on three parts representing constructive responses to the crisis as related to trust. First, decentralized decision-making involves the collaboration of multiple stakeholders in the decision-making processes. Second, communication from top-down, higher-level leadership, to bottom-up, from other stakeholders, in clear, consistent, and transparent ways. Communication seemed to be the most significant factor in establishing, maintaining, and also sustaining trust (Kutsyuruba et al., 2011; DeMartino, 2021). Finally, collaboration and compromise (Sutherland, 2017) from top-down to bottom-up and between organizations is significant to building trust in a crisis. Likewise, the study of Sutherland (2017) indicated the most important factors of trust were honesty, openness, and benevolence. “When honesty, openness, and benevolence are perceived to be a problem trust was very low. Low trust behaviors undermined good communication, decision-making, and disrupted possible collaboration to solve problems” (p. 12). However, once trust was established, it was imperative for school leaders to preserve this earned trust (Kutsyuruba and Walker, 2015). One way to preserve trust is to develop significant relationships based on agency with other members within educational institutions.

Leadership and Agency

Crucial for effective leadership is for the leader, in this case, the educator to be empowered and agentic. There has been a debate for decades over the role and definition of a leader—but we squarely understand leadership as action and empowerment. This is a purposefully broad interpretation of leadership, and thus as a leader, it is necessary to understand the multiple manifestations that leadership may take in educational administration and leadership. Furthermore, the literature related to educational leadership is broad and diverse including variations between the K-12 and the higher education body of work. As this project and thus this paper considers the leadership taken under crisis by educational administrators at both the K-12 and post-secondary level, we take a broad interpretation of leadership in order to account for the differences between contexts.

Furthermore, drawing upon the work of Raelin (2016), we understand that leadership to be collaborative. Historically organizations have been structured hierarchically, where “executive managers have been counted on to make the important decisions” (Raelin, 2016, p. 27), due to an expectation that these senior level leaders are thoughts to be able to engage in more complex tasks. As such, the understanding is that the more junior members of an organization would carry out these tasks. This hierarchically organized organizational flow likely comes off as unsurprising to most as while it is based on a historical understanding of organizational leadership is still manifest in contemporary organization structures. Raelin (2016) calls for an understanding of a leadership model in a “post-bureaucratic” (Heckscher, 2011) era, which considers what leadership could be if it were to move beyond a contemporary understanding of the bureaucratic model of organizations.

This model engages a paradigm shift to rely on decision-making, not through acquiescence to authority, but through dialog and for individuals to not be defined by their jobs, but to be able to think creatively and cooperatively in order to achieve the outcomes that are better for the organization. Importantly for this project, a post-bureaucratic system is built on the expectation of change. This is vital in times of crisis. Within a post-bureaucratic system, individuals are empowered to make decisions to follow not the mission of the organization—but to understand the guidelines of action. Importantly, these are derived collaboratively, and these organizations must and do “spend a great deal of time developing and reviewing principles of action” (Heckscher, 2011, p. 103). As such, this is not a move that an organization can flip on and off but must be a continuous and ongoing effort to switch paradigms. While few if any educational organizations embody this idea, it is important to understand in order to envision both what is occurring and what could be.

Within any organizational structure, power is evident. Within organizations, this power enables certain individuals to participate and for others to opt out. It is the power that intersects with the habitus (Bourdieu, 2010) of the organization to understand how to navigate the organization. How, during a time of crisis—in which the entire educational and organizational script is flipped, does habitus manifest itself? How are these ideas shaped and reshaped by those who have organizational agency? An agency within organizations is framed by leadership in a contemporary mode of organizational theory because most organizations—especially educational organizations have not moved beyond a business-oriented model of leadership that took hold within education during the neoliberal reforms originating in the 1980s. This model of leadership disallows for flexibility and dialog, such as organizations using a post-bureaucratic model of organizational theory. As such, the agency is often hampered as it challenges the great-man theory of leadership, something that Raelin (2016) calls the heroic model of leadership. In a post-heroic model, decisions are no longer linear, but widely distributed. As such, more individual autonomy and agency are expected.

We understand agency as broadly the capacity to take action. As such, in a purely bureaucratic style of organization, there is low individual agency. We find a great disparity between the agentic empowerment in our project, and this has strong impacts on the experiences of the educators. Interestingly Amar et al. (2012) illustrate that the reason that organizations often fail “to respond to market conditions is the inability of their senior leaders to manage their organizations to the complexity and dynamism of their business environment” (p. 69). This is not to say the educational organizations need to double-down on their commitment to reflecting business, but that as Amar et al. (2012) asserts that a management style that enables leadership at all levels so as all individuals can assume leadership roles and “make decisions and manage their part of the business like the top managers” (p. 69). By again calling on the ideas of a post-bureaucratic organizational model where all members of the organization are empowered to make decisions for the betterment of the organization, following the guidelines of action supports the agency of all. These ideas are supported by some of the experiences of the educational leaders during a crisis within this project.

Materials and Methods

Using the narratives of 15 educational leaders who were selected on the basis of highlighting the different types of institutions and regions across the U.S., we spent time with these leaders from K-12 and higher education to attempt to document their experiences and images in an effort to bolster the knowledge about leadership under crisis. This institutional review board (IRB)-approved project began as a hermeneutic phenomenological project framed by standard interviews using con. Using a hermeneutic phenomenological frame enables us to focus on the “language, conversations, one's historical context, understanding, and interacting with cultural elements” (Bhattacharya, 2017, p. 100). As such, to craft better understandings of the ways the photographers engaged with the cultural elements of their lifeworlds, we used images in an adapted photovoice study, where participants were asked after the first interview to share images that typify their experiences as administrators during this crisis. Using a bricolage approach to method, in an attempt to create multiple avenues for interpretation of the data was crucial to capture a more in-depth understanding of the experiences of participants. However, anytime photos are involved in research, ethical concerns must be addressed, and we must engage in continuous and ongoing consent (Weiser, 2020). This additional element of the project adds depth and nuance to our understanding of the responses, both individual and institutional, and also local and nationally, to the pandemic. By using photos as a space to listen to people we are “dealing in voices” (Fine, 1994, p. 20) with an attempt to better comprehend experiences. However, we are careful to accompany images with narratives from the photographer so as to attempt to stop mis/disinterpretation of the images (Call-Cummings and Martinez, 2016). Moreover, visual research adds credibility to the voices of participants. Challenging power relations with images is a natural move as images are harder to disbelieve than narrative of someone. As such, we use a modified version of photovoice not only to better comprehend the experiences and narratives of these administrators, but also to use these pieces of data to back up their narratives. Using photos people help to elevate narratives and show, rather than tell, their experiences.

In using interview data, and visual data that accompanies the interview data, we coded both pieces of data to find themes. Using an open coding process, we first coded the interview data using structural coding and in vivo coding processes (Saldaña, 2015). From here, we themed the data to continue to build our understanding of the data and the experiences of the administrators. Moreover, the fieldnotes from the interviews, and analytic memos speaking to our own experiences within this project served to accompany this data. As one of the complexities of this project was the recursive nature of the project—conducting research on the experiences of educational administrators working during the pandemic, using a medium, which they were on all day, we had to attend to not only what we were asking the participants to undertake, but also its impact and toll on us.

Clarke (2005) suggested that we should ignore visual data in the contemporary era at our own analytic peril. To that end, we take the visual data as seriously as the interview data within this project. We treat the visual media, in this case, images such as photographs and memes, as a source of rich data. These points of data embody the meaning and values within our material culture. As such, the meanings were of particular significance for this project (Berger, 2014). The images were coded through descriptive and emotion coding. Descriptive coding allows us to quickly ascertain what is in the photo, and emotion coding allows us to understand the effects that are being transmitted through the image. While coding visual data, such as photographs, may be a “slippery slope” (Saldaña, 2015, p. 57), and there is a deep irony to using words to code and categorize images we agree with Saldaña who argues that we use codes to accompany the visual data—not to stand in the place of the images themselves.

Using these points of data, (a) the interviews, (b) the shared images, (c) the field notes, and (d) the analytic memos we arrived at several themes across both the K-12 and post-secondary sets of data. These themes and their relevance to education writ-large are outlined below.

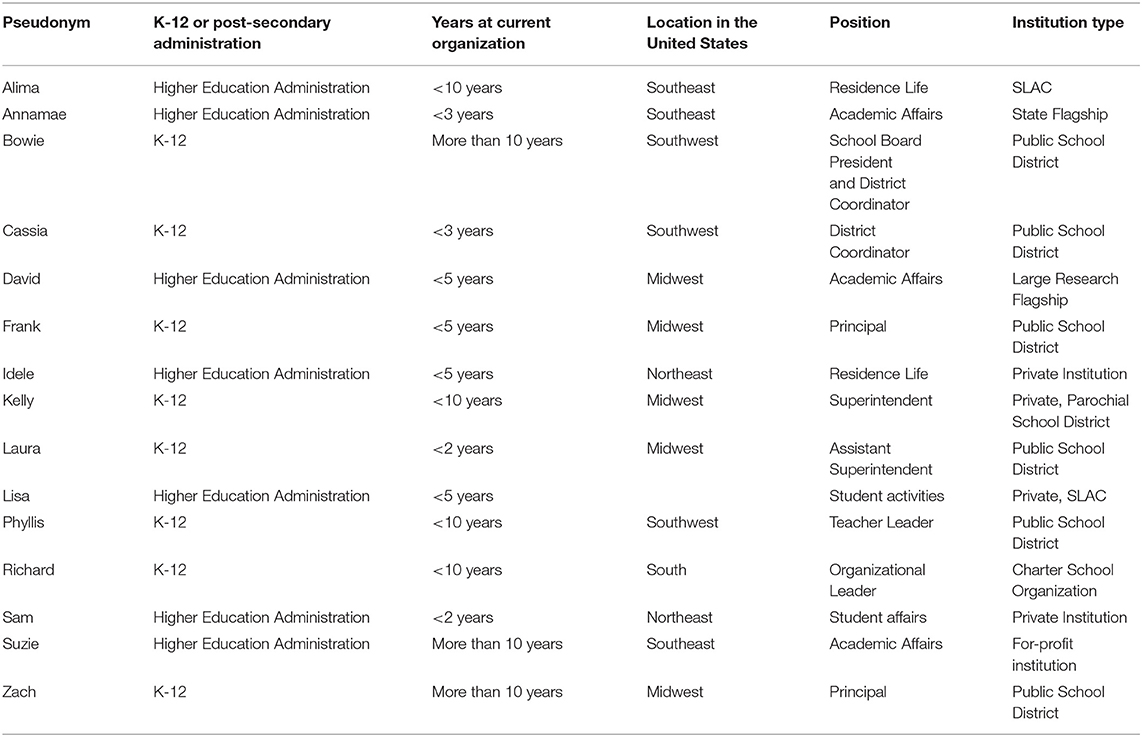

Through this project conducted interviews with 16 different educational leaders from various types of institutions and different regions of the U.S. This study specifically was only looking at educational administrators within the U.S., and while we acknowledge that this time of crisis is by no means specific to the U.S. as this was a purposeful delimitation on our part. In Table 1, we placed the names of the participants, coupled with some additional characteristics, including years of experience, location, title, and type of organization, with which we worked over the summer and into the fall of 2020 to better understand their institutional responses to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis within education. We worked with seven higher education administrators and eight K-12 administrators. We did speak with one more higher education administrator, but that data had to be removed from the study as she was an administrator at a university in Africa, and thus was beyond the scope of this project.

The participants came from all over the U.S. with a heavy emphasis on regions that were particularly hard hit by the pandemic during the time of participant recruitment, such as Florida, New York City, Chicago, and Arizona. Moreover, we also had individuals from Illinois, Massachusetts, Alabama, Iowa, and Virginia. As such, while the West Coast and the Pacific Northwest are notably absent, the participants come from a variety of different regions which are reflected in their experiences and in the responses they share with us.

Results

Communication Under Crisis

Administrators in K-12

In K-12, communication varied in terms of support, including transparency, communication with faculty and staff, and communication with students and families. Laura, a K-12 district administrator, noted her efforts to be transparent with her school administrators, teachers, and staff. When her district first went into lockdown, there were daily meetings with directors, administrators, and teacher's union representatives at the table. In these meetings, transparency ensued. In fact, she noted, “there's nothing that anybody on my staff could not ask me.” Likewise, Phyllis, a teacher leader, noted that her district had the appearance of transparency because she received frequent communication with her principal, the special education department, and the curriculum department.

On the other hand, Bowie, a school board president and educator, discussed one of the burdens that leaders in crisis face the challenges associated with transparency. After emphasizing the importance of communication, she expressed that it is the role of school leaders in crisis to not to share everything, but to be able to distinguish between what people need to know and full disclosure. She stated in a crisis moment, it is about what people need to know “because they're grappling with so much and they're trying to juggle so much. What do they need to know to allow them to continue doing what we need them to do to move the work forward?” Similarly, Frank, a school principal noted another burden carried by leaders in crisis was the struggle of rapidly changing information. He said, when delivering information to his faculty and staff, “it was here's what I know. Please know that this could change in 10 minutes.” Likewise, Zack, a school principal, described the tension of keeping his faculty and staff informed as much as possible and experiencing the physical impact of that demand. According to Zach, “keeping open lines of communication between everyone was absolutely essential and just encouraging everyone to stay connected I think, you know, it did take a toll, as well.” Given the burdens and challenges faced by these educational administrators, communication with faculty and staff was strategic.

Shifting to communication with faculty and staff, Laura focused on communication was primarily through webinars. She stated communicative efforts of her district were through bi-monthly webinars for faculty and staff to keep them in the communication loop. Likewise, Phyllis said her superintendent was posting and sending updates to the faculty and staff, “when they got big pieces of information that they were confident in.” She went on to say that the confidence of her district in relaying information was contingent on the state board of education. Given these data, the educational leaders from our study persevered when the larger organizational structures of communication broke down.

In terms of communication with students and families, Laura shared that the first 2 weeks of remote learning were dedicated to student and family check-ins. In fact, she said, “the only learning objective was to contact every single kid or family in the district by making sure to reach out to all students and families.” This effort resulted in 86% contact with students and families in her district. Also, Zach talked about finding the right way for teachers to reach out to students and families. As a school priority, he said, “we were communicating with families right away and finding out how are they doing, and so we created our own internal system before the district created their system.” Similarly, Cassia, a district level administrator, indicated the priority of her district was “to try and contact every single student in their schools and their families and their schools to make sure that they had a means to contact them.” In her district, they used community agencies as resources to contact their more mobile families. Cassia likened this to a complex telephone tree by using every resource to communicate “out to the students so that we had constant means of communication because this terrain…is like moving sand every day…So, we had to be able to get everything in place to be able to communicate out.” In sum, communication with families was a call to action to contact as many students as possible.

Administrators in Higher Education

Communication within higher education was markedly different. Often institutions were so concerned with appealing to and understanding what their peer institutions were doing that they were far slower to communicate and respond to the pandemic. This also is tied to the idea of caring. For instance, Alima, who works in a residence life shared that they “didn't want to put anything out there that they can't deliver” and that many schools would “put out there that we are working diligently and we're having everyone in the forefront of our mind,” but the school of Alima did not put any statements out there, and there was nothing but “silence.” Most concerningly, Alima shared that because she works at a small school and the community is small that the word “family” is often used to describe their community yet there was no communication with this “family” to let them know what was going on. This is an interesting dynamic of the use of the idea of family within higher education administration. This lacking communication and care illustrate how the idea of family is sometimes weaponized to guilt administrators into the idea that education is more than a job but is a calling. This perpetuation of the idea of family allows educators to do the job for less because it is more than a job, it is a passion and a calling more than just a vocation.

Alima would spend hours on the phone talking with parents, with calls averaging “30 to 45 minutes” with her just “walk[ing] them through and reassuring that it's going to be ok, yes we're still going to look at who you want to live with” but she was unable to give any specifics to these parents or students as all of the information about what was going to happen with regard to student housing had not yet been released, and all of the recommendations she would offer even though she was an office of one and was the director, her decisions had to get approved by her vice-president and the cabinet level. She says that while she may “think some of these decisions are final and this is the route we are doing, I always get nervous that until the cabinet and the president say ‘yep, this is what we're doing’ I'm afraid to say it to parents and students because if something changes I don't want them to come back and be like, ‘well, you said that this is what was going to happen’ and so I think that's been probably the biggest struggle with my staff is we know a lot of information. We kinda know where we're headed, but until we get a blessing from the cabinet it's just hard for us to give specifics.”

Lisa shared that early on in the crisis that social media was a primary platform that her institution used with regard to communication. Her work in admissions made it so that incoming students would still continue to reach out to her and her colleagues as they are the “trusted people that they've been working with and that's who they're going to come to first” for many students and parents. However, Lisa and many other front-line higher education administrators were not empowered to make decisions, and often these individuals face the brunt of frustrations for lack of action or decisions on behalf of upper administration. Most concerningly, Idele shared that decisions would be made by individuals who were in the senior leadership group, but that the front-line individuals “that were responding to it didn't have the information for their parts” of the response.

Along the same lines, David, who transitioned from a large public institution in the mid-west to a small private religiously affiliated institution in the mid-Atlantic during our conversations was able to compare and contract communication and messaging between institutions. He was excited that the new institution he was transitioning into was more transparent and open with their communication with the staff than his old institution. He shared that the communication “is so much more direct and it all comes from the same person and they really do appear to be doing everything they can to support the broader university community.” Pivoting to the darker side of communication, furloughs were a real threat to personnel employed by institutions of higher education.

As such, both Annamae and Sam shared with us about the communication of furloughs that were occurring during our interviews. Both of them were communicated to the staff via Zoom presentations that were not open for questions, and that neither of them had any insight into how decisions on these furloughs were being made. For Annamae, this was a scary thing to consider because she felt that “if anyone was on the chopping block, it would be me and some other entry staff.” This echoed the experience of Sam as well who was identified as entry-level staff. While neither of these individuals was selected to be furloughed, Sam came quite close.

For Sam, communication about furloughs took a very personal impact. Her boss called her into a private meeting and informed her that while fortunately she was not getting furloughed that she would “have a chance to save [her] office coordinator and that [she could] elect to take a different position for the year” in a completely different functional area outside of her expertise and interest in order for her office to retain the coordinator. This other position would be as a live-on residence hall coordinator. If she kept her current job, the coordinator would be furloughed. This option would remain between the director of her unit and herself, and no one else would know about it. She eventually ended up electing to not—using his terminology— “save her” and as such she was furloughed until at least January. This decision was also complex as there was no promise that should she move to residence life maintain her employment should enrollment and/or on-campus living decline. Moreover, living in a residence hall during a pandemic has its own concerns with the viral disease that spreads very fast. This abuse of power and communication is perhaps singular and extreme but is significant in how entry-level administrative staff were treated during the pandemic.

Caring and Trust

Administrators in K-12

The K-12 administrators in this study showed commitment to both caring and trust in serving their larger school communities. Caring was displayed by the school administrators in this study by accessibility, connections to their students and families, and public displays of recognition and celebration. Kelly, a district superintendent, talked about her accessibility to her school principals 24 h a day to collaboratively handle issues as they arise. Pivoting to the larger community, Laura celebrated the tenacity of her teachers during the shift to remote learning. She stated, “our teachers went above and beyond anything I could have ever asked of them.” She went on to say that there were no employment cuts made in the spring or fall semesters. In addition, Bowie talked about “do no harm” policy of her district as their driving principle. In fact, she shared that she knew of a teacher who was still meeting with students throughout the summer to maintain her connection with them and made the point to say that she was probably not the only one doing so. Phyllis, Richard, and Cassia talked about similar district initiatives to contact every student, including home visits. Frank talked about the caring school community where members of his faculty and staff “stepped up and said, give me a list of your kids. I'll check on your kids. You know, so we did our best so that kids didn't fall through the cracks.” He went on to say that his faculty and staff were supportive and creative when it came to supporting their students, faculty, and staff through celebratory events. For example, they arranged drive-through graduation parades (Figure 1) and made individual trips to every graduating senior and retiring faculty or staff persons to acknowledge their achievements and marked their property with school spirit signs. These administrators furthered their culture of care by advancing and maintaining trust with their school communities.

Trust was expressed by these school administrators by prioritizing the needs of their community over the expectations of the district. With the absence of district guidance, Zach discussed the importance of meeting regularly in a virtual format with his faculty and staff to discuss where his school community was currently and what it might look like for the coming week, “in the absence of guidance, what do we need to do to meet our students and our families and the obligations to them.” In fact, his district did not respond with guidance for about 6 weeks whereas he stated, “I think there's a lot of missed opportunities to build trust within between the administrators and the district.” Zach went on to say, the district started by prioritizing what they thought was important, such as tracking technology devices and providing guidance on faculty and staff annual evaluations (Figure 2). With this, Zach pushed back with, “to be honest, it wasn't a huge priority of mine” and centered his efforts on supporting his school community rather than keeping tabs on less important matters. Similarly, Frank expressed that as a leader, you needed to be aware of how complicated the lives of people were in quarantine. As part of his mindfulness, he said, “I was constantly reassuring them that if we were scheduled to meet at two o'clock and your kids are sitting in your lap, that's okay because mine is sitting on the floor.” Although some of these acts went against the organizational grain, these administrators embraced and maintained trust as they prioritized the needs of the community first.

Figure 2. The submitted meme of Zach depicting district expectations vs. his priorities. This figure was originally obtained from a public database.

Contrary to building a culture of care and trust, there was evidence of more punitive measures to protect the organization rather than the community. Since her district early on made the decision to return to in-person classes, Kelly elaborated on their mandatory liability waiver, “it was created through our legal department that has family signing off that they understand the risks of the pandemic and we've asked the families…to please self-report if they do have it in the home or if someone's been exposed.” In higher education, the administrators seemed less cared for leading to more distrust of their higher-level administrators and the institution.

Administrators in Higher Education

This experience with Sam and the director of her office “permanently broke that relationship from [her] boss and I, because of it, I don't trust him” anymore. Moreover, this instance was not only a clear violation of trust—but was, we argue, a botched attempt at caring. While he was attempting to save the job of another employee—an act of caring—he put the burden of this decision on the shoulders of Sam. While the boss of Sam may have had good intentions in attempting to save both jobs, both he and Sam were put into impossible situations here: the boss of Sam by the pandemic and upper administration and Sam by her boss and the pandemic. In this instance, both of them express agency in their choices, but their choices are limited by the decisions that those in power above them are making.

Idele, who worked in housing, was overly micromanaged in her role during the pandemic. This experience illustrated how upper administration did not trust her to do the job that she had been doing for years, a job that her “director doesn't even know what [she does] to make things work.” This lack of trust was a deciding factor in her deciding that it was time to move on from her role—not only from this institution but also potentially from higher education administration in general.

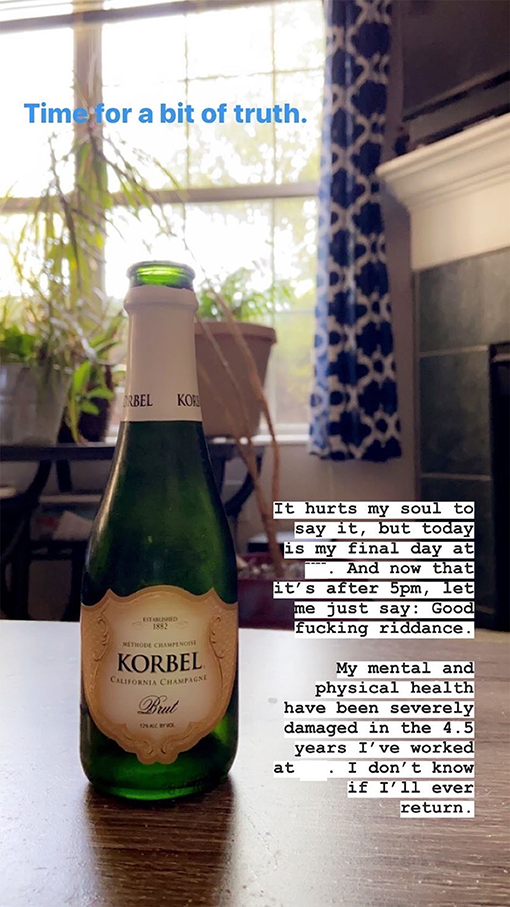

David, who transitioned from one institution to another during the pandemic, transitioned in part as he felt his previous institution did not care. He stated that “universities do not care. I'll keep it specific to public universities do not care about staff, there's zero power in being a staff person.” The on-going mental abuse that he faced at his previous institution was the driving factor for his departure. Furthermore, due to the pandemic and the experience of working from home, the first time and way that he was able to communicate that he was leaving was through Snapchat (Figure 3), which he later shared to Facebook as a screenshot to share that he was leaving. This long-standing abuse that he experienced as a staff member at his former institution is not a lone incident—many lower-level administrators experience burnout through compassion fatigue and end up leaving their institutions. Coupled with secondary trauma that much higher education and student affairs administrators experience—this can create a toxic work environment (Lynch and Glass, 2020).

Agency

Administrators in K-12

Most K-12 administrators were mindful to equip their community with agentic opportunities through such measures as seeking assistance from faculty and staff, advocating for the voice of teachers, and surveys. In her meetings with other upper administrators, she said: “that they had no issue in saying we do not know and sought assistance from their faculty and staff.” More specifically, she said, in her webinars with faculty and staff, she turned to them for input because “there's no badge of courage in educational leadership to think that you have all the answers.” This statement is incredibly powerful as there is still evidence of educational administrators leading with a top-down approach rather than an authentically collaborative approach, as Laura indicated with her metaphor. Along the same lines, when discussing her re-opening plan of district, Bowie declared, “I am just like advocating like never before for the teachers' voice in these decisions.” Also, some K-12 administrators used surveys as their primary tool to exercise agency with their faculty, staff, students, and families. Referring to her survey data, Laura stated a new teacher to the district expressed that she came from a different school district and had no idea what her superintendent looked like. And here, in her District, she was getting daily updates. Laura went on to say that all employees had access to these updates from school monitors to paraprofessionals to administrators.

On the other hand, the lack of agency for school stakeholders was closely aligned to the K-12 differences in communicative actions as Kelly and Richard utilized more of a top-down rather than bottom-up approach to working with their staff. For instance, Kelly most frequently used Zoom to communicate with her principals to take their questions and “settle them down.” Other times, Kelly used her Zoom sessions to share research with them to develop a remote learning plan as they transitioned to fully in-person classes at the onset of the fall semester. While care was given to the transition of remote special education services, Richard continuously pivoted to the actions of the CEO, implying a more hierarchal structure. As such, although directives were given, there is very little evidence that Kelly and Richard worked collaboratively with their school communities.

Administrators in Higher Education

Building on the lack of trust that many higher education administrators experienced during the pandemic crisis era—Sam, like many other administrators, was mandated to keep her camera on during meetings. This was inclusive of large division-wide meetings with an upward of 70 people. Her boss “told us directly to keep our cameras on like he expects that of us, and also not to be on our phones because there are other people that are sitting there blatantly texting.” Sam's boss mandated that his office keep their cameras on during these large meetings when they are “pretty much just sitting there listening to someone else.” Her boss stated that he thinks of this as an office-wide accountability thing, which Sam admitted to empathize with, but that she also stated that as someone who “suffers from severe anxiety, it's so weird. How much worse it is to be on a Zoom call in terms of constantly being aware of how you're looking, you're positioning or lighting and things like that – it's exhausting.” This was specifically speaking of large meetings and that during small meetings it was not an issue, but that in these spaces she felt that it was “just kind of really exposing – almost just constantly being on display.”

For Lisa and many of the higher education administrators whom we spoke with, they often received directives from the “president, the provost and those circles” and that she felt that staff were ignored in not only the decisions being made but in the plans themselves. She stated that staff “are here too and we have to physically be [on campus] and even with us trying to recruit or have visitors on campus and really not being given much direction of how to do their return and all of the policies and things like that. And then we're told, Hey, we need you to reopen, you know, in a couple of weeks for visitors figure it out. Oh, great.” This experience with Lisa is indicative of the experiences of many higher education administrators at the entry level, who were expected to be on campus with little to any input. Moreover, as was the case with Lisa, not only they were not given the opportunity for input into the decision-making process, but also they had to return to hosting visits to campus during the pandemic without any guidance other than this had to be accomplished. Likewise, Alima shared that this information was unevenly shared, that “depending on the supervisor and director there's a lot of people just kind of left sitting out in the dark just unsure of what we are doing, where we are going.” This mélange an expectation with doing a job with no input on how this job is to be accomplished or even where this job was to be done makes for a disempowering and disagentic work experience.

Discussion: Reimagined Leadership in Crisis

According to Sutherland (2017), “it is important to identify that the school and community response to the crisis as complex rather than simplistic. It is an on-going process rather than a day or week or month following the crisis” (p. 13). As a response to the complexity of leaders under crisis, developed leadership in crisis competencies, including leadership actions, such as communication, problem-solving, innovative and creative systems of thoughts, planning and organizing of personnel, motivation, team building, and decision-making are crucial (Kapucu and Van Wart, 2008). Following suit, our leaders under crisis and the structure of our project, engaging participants in the U.S from both K-12 and post-secondary institutions, we found varied responses between systems.

The most notable variations in responses from our higher education compared to our K12 participants were the timeliness and the nature of communication, the absence of caring leadership, and the lack of agency between both levels of educational institutions. As such, in this discussion, the authors elaborate on the distinction between what the institutional response was as compared to what was valued by our educational leaders. In addition, we discuss how these values guided the individual responses of our educational leaders to enhance their responsiveness to their immediate educational communities against the backdrop of an unavoidable world riddled with volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity This was also evident in the higher education administrators initially being less represented in the photovoice element, as many of them expressed fear and apprehension about this component and did not participate as often as the K-12 participants.

Communication During Crisis

Because our contemporary leaders are working in a world characterized by volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity, the pressure to make decisions in a timely, revolving, often contradicting time in the best interest and safety of their school, college, and university communities while under deep scrutiny is both exhaustive and uncertain. In fact, Hutson and Johnson (2016) offer insight for the leader in crisis by challenging the traditional notion of the leadership of being in charge in favor of collaborative support with the greater community, “the healing leader works alongside others in the organization, not solely from a position of power or authority. Recovery can't be commanded, but it can be supported” (p. 61). Put differently, this insight is a direct recommendation for leadership in crisis to move away from traditional notions of leadership to make room for more authentic collaboration between stakeholders. Furthermore, Mishra (1996) noted leaders in crisis must communicate between constituencies in clear, consistent, and transparent ways, from top-down to bottom-up. Our findings are consistent with this recommendation as our participants were often uncertain of the institution's emergency planning and clearly valued the opportunity to provide feedback to the heavy-handed emergency protocols of the institution but were not always able to do so. In K-12, communication varied in terms of support, but most administrators from this study approached communication as a more collaborative way by choosing to concentrate more on transparency, navigating the burden of transparency, and grappling with the challenges associated with the communication. For example, Laura was fully transparent when communicating with her district, whereas Phyllis believed her district seemed to be fully transparent but had some hesitations. However, both leaders felt total transparency was the best way to communicate with their constituencies.

In addition, Hutson and Johnson (2016) conveyed the importance for leaders to relay truthful, consistent, timely, and empathetic messages to their communities in crisis. However, Bowie, Frank, and Zach discussed the various burdens and challenges associated with both transparency and communication under crisis. As such, Bowie discussed the leadership burden associated with transparency. She expressed that it is the role of school leaders in crisis to not share everything but be able to distinguish between what people need to know and full disclosure. In alignment with Hutson and Johnson (2016), without these communicative interventions, we argue this is a powerful leadership skill in order to avoid hysteria and mitigate fear with the greater school community. In doing so, the district community is aware of the pertinent information to function through the crisis rather than being strapped by too much information that can lead to stalled progress. Also, Frank talked about the need to be transparent but the struggle of rapidly changing information. Similarly, Zack elaborated on the tension of keeping his faculty and staff informed as much as possible and experiencing the physical impact of that demand. These burdens and challenges associated with communicating under crisis in a rapid manner with swiftly changing information were absorbed by the K-12 administrators to support their greater school communities.

In addition, we found that higher education administrators more often expressed frustration by the lack of transparency in communication. Finally, the other most pressing element was the lack of leadership and taking action expressed by higher education administrators. Alima shared how her institution and her staff attended many meetings and engaged with conversations with other professionals across the country to “just hear what other schools are doing because we want to make sure that we're not doing anything [out of the ordinary].” Likewise, Idele stated her institution was a follower, not a leader. She indicated that her institution would watch another school in the region for a week before deciding to take their lead. She struggled with this response as she is not a “reactive person. I've a very proactive person and part of my role requires that” as she worked in a role where the work of others is dependent on her work. As such this “reactive role is definitely very, very, very hard.” This mimetic isomorphism—wherein institutions were slow to act without consulting what their peer and aspirant institutions were doing may have slowed down the administrative response to the crisis. It also added to the frustration on a macro level as another manifestation of a lack of agency. Where many higher education administrators lacked agency in their decisions in the micro day–to-day level, this serves as a manifestation where these individuals or even the leaders of the institutions did not have agency at the macro level—waiting for others to lead. There might have been other institutions, but often they were also waiting for guidance from the federal government, which never came. As such, many of the participants expressed frustration that no action would be taken until the institution examined what their peer and aspirant institutions were doing.

Caring, Trust, and Agency Under Crisis

To move from Is to collective we, caring as authenticity requires openness, transparency, and genuineness (Noddings, 1991; Sergiovanni, 1994). With the absence of district guidance, Zach encompassed this collective we by discussing the importance of meeting virtually with his faculty and staff to just talk about where his school community was at and what it looked like for the coming week. As a caring leader, Zach pushed pass the bureaucratic restraints, including technology audits and evaluations (Figure 2) and put the needs of his community at the forefront. Furthermore, in alignment with Stefkovich and Begley (2007), critical administrative self-reflection combined with empathy (Fairholm and Fairholm, 2000) builds both caring and trust within the school community. Like so, Frank was aware of how complicated the lives of the people were in quarantine. He empathetically reassured his faculty and staff that working at home blurred the lines between home and office. In doing so, he realized that children and other loved ones needed care during school hours. Finally, collaboration and compromise (Sutherland, 2017) are significant to building trust in crisis. Laura lauded the collaborative efforts of her teachers during the shift to remote learning. Along the same lines, Frank talked about the caring school community where members of his faculty and staff volunteered to make home visits and plan for community celebratory events (Figure 1).

In contrast, some of the K-12 administrators used more authority in a hierarchal way, or more top-down, than other administrators who approached communication as a more collaborative way, or more bottom-up. This lack of agency for school stakeholders was closely aligned to the K-12 differences in communicative actions as Kelly and Richard utilized more of a top-down rather than bottom-up approach to working with their staff. For instance, Kelly most frequently used Zoom to communicate with her principals to take their questions and “settle them down.” Other times, Kelly used her Zoom sessions to share research with them to develop a remote learning plan as they transitioned to fully in-person classes at the onset of the fall semester. While care was given to the transition of remote special education services, Richard continuously pivoted to the actions of the CEO, implying a more hierarchal structure. Again, though directives were given, there is little evidence Kelly and Richard worked collaboratively with their school communities. Given the hierarchal structure in districts of both Kelly and Richard, this top-down structure was not well-suited for the agency.

The higher education administrators exhibited much less agency in their experiences. This stands in stark contrast with the experiences that we heard from many of the K-12 administrators who were more often than not empowered to make decisions. These K-12 administrators expressed much more satisfaction with the way that education and their institutions were handling the crisis. As such, we believe that the differential expressions of agential power between the K-12 and higher education administrators played a pivotal role in their satisfaction and feelings of adequacy and control during the crisis. One participant, Sam, even shared with us that she had to insert the work that she accomplished on a day-to-day basis in a shared spreadsheet with her supervisor. While outside the bounds of the research project, the second author who hasmany connections to higher education administrators within the field saw this reality manifest through social media posts as well, noting that this was not indicative of one person nor one supervisor, but endemic of a lack of trust between supervisors and those they were supervising. This connects directly to the bureaucratic norms exhibited by many institutions—a maintenance of control and power over subordinates. Further, Sam and others who were forced into having their cameras on during meetings—and for some during routine working hours—have been forced into a virtual panopticon (Foucault, 1995).

Further, initially many of the higher education administrators expressed apprehension about the photovoice component of this project. They were afraid that images could expose them as speaking against their institution and may put their jobs at risk. While the use of images in research is always a risky endeavor, we strive to ensure that any images we would use could not be traced back to the photographer in question—even when some of these images have distinctive elements. This apprehension to join the visual part of the research project may also have been in response to the way that the participant expectations of the image in Zoom meetings may have been abused in their work-life as well.

Conclusion

This study contributes to the understanding of educational leadership under crisis in a school, district, college, or university. Primarily, in alignment with the former research on crisis leadership with the addition of positioning caring as an administrative act, this study revealed the importance of communication, caring, trust, and agency when navigating educational institutions in crisis. Furthermore, as a contribution to the field, using guidance from our participating administrators, we offer recommendations for future administrators in crisis based on these data. Because it is important not to put the genie back into the bottle, the COVID-19 crisis forced educational institutions to function remotely. Furthermore, it is the duty of educational administrators to build these remote capacities with the input from their constituencies with a priority on caring relationships. Also, within both K-12 and higher education, it would be in the best interest of educational futures to use this moment to reconceptualize what administration can look like in the post-pandemic era. This is certainly hard to consider still in the throes of the pandemic, but based on the narratives of these administrators in concert with considerations based on extant research we recommend a few alterations to the leadership within higher education.

First, it is a more inclusive and transparent decision-making process. This is certainly difficult to accomplish, and we believe working in a more post-bureaucratic framework (Heckscher, 2011) would be beneficial to consider. Empowering all members of the institutional structure to work within the guidelines of action to think creatively and cooperatively to achieve better outcomes for the organization. This move would address many of the issues that the administrators faced during this pandemic as suggested by Zach, and before as illustrated by David.

Second, it is impossible to ignore that for many higher education administrators, they are able to do their work just as well-remotely. The second author has explored the ways that often student–administrator affairs are forced to being on campus for their job at times in which it does not make sense for their work because the institution is adhering to a business model. Moreover, staffing an office full time when there is no need is abusive and may cause further burnout and alienation—a distinct lack of care for the individual. Faculty have long been able to work remotely and in spaces that are more conducive for their work. Perhaps this is a moment in which we need to consider the way that we can reconceptualize the working experience for many higher education administrators. For instance, many academic advisors have been able to hold more appointments and have fewer no-show students for appointments while using tools such as Zoom. If this is the case, a blended approach to working on and off-campus may be in the future. This is something that Suzie directly addressed, stating that she felt that working on campus for her and her staff would never go back to the way that it was. That when moving back to campus was happening that not everyone would come back full time. In her role as an academic administrator, she was more productive in her time working from home than she was working on campus. While she, and many others, missed their colleagues, working from home was, at times, more beneficial for their work experience.

Finally, all educators need to spend time in retrospection about the role of care, trust, and agency in their workspaces. How are administrators enacting trust with others to empower them to have the agency to adequately communicate with their teams and constituencies through an ethic of care? We heard wonderful examples of some educational leaders enacting these vital skills in their work, but this was not the case for all. This reflects a larger conversation being had in trade articles about burnout, fatigue, and alienation during this time. It is known that many teachers leave the profession after a few years and that even more are preemptively leaving the profession at a time where many schools are short-staffed. This is true of higher education administrators as well. As Mawhinney and Rinke (2019) note that this teacher attrition results in “decreased achievement for students, high financial costs for schools, and deprofessionalization for teachers”(p. 3). If we are to retain the talent and institutional knowledge that we argue is essential for an agile response during a crisis, then we need to demonstrate care for our colleagues and trust them to be empowered to make decisions.

We are putting the final touches to this manuscript in March of 2021—just over a year after a March in which many teachers, administrators, and other educational leaders used their spring break to begin a marathon of pivoting in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We are hopefully seeing the light of day with the increasing availability of vaccines. While there are many obstacles to overcome in education yet, related to COVID-19 and a host of other issues, we hope that by attending to a global issue that transcends geography and industry—capturing the experiences of some educational leaders, we can begin to use these as starting points to understand how to better respond to the crisis in the future. We know that they will happen, they are already always ongoing. As educators, we hope that this scholarship will help educational leaders reconceptualize crisis leadership to be more agile, thoughtful, and proactive, rather than being stuck in a reactive pivot model such as the one witnessed throughout 2020.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Illinois State University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

LD worked on the K-12 part of the study. SGW worked on the higher education part of the study. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This project received a grant from NASPA Region IV-East.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Amar, A. D., Hentrich, C., Bastani, B., and Hlupic, V. (2012). How managers succeed by letting employees lead. Org. Dyn. 41, 62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2011.12.008

Berger, A. A. (2014). What Objects Mean: An Introduction to Material Culture, 2nd Edn. Walnut Creek, CA: Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (2010). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology 16. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bump, P., and Parker, A. (2020, April 26). 13 hours of trump: the president fills briefings with attacks and boasts, but little empathy. The Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/13/hours/of/trump/the/president/fills/briefings/with/attacks/and/boasts/but/little/empathy/2020/04/25/7eec5ab0/8590/11ea/a3eb/e9fc93160703_story.html (accessed October 5, 2020).

Call-Cummings, M., and Martinez, S. (2016). Consciousness-raising or unintentionally oppressive? Potential negative consequences of photovoice. Qual. Rep. 21:798. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2016.2293

Centers for Disease Control Prevention (2020a). First Travel-Related Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Detected in United States. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0121-novel-coronavirus-travel-case.html (accessed October 5, 2020).

Centers for Disease Control Prevention (2020b). CDC Confirms Person-to-Person Spread of New Coronavirus in the United States. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0130-coronavirus-spread.html (accessed October 5, 2020).

Centers for Disease Control Prevention (2020c). CDC Releases New Resources and Tools to Support Opening Schools. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0723-new-resources-tools-schools.html (accessed October 5, 2020).

Chor, L. (2020). How Hong Kong Reopened Schools-And Why It Closed Them Again. NPR. Available online at: https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/07/10/889376184/photos-howhong-kong-reopened-schools-and-why-it-closedthem-again

Christle, C. A., Jolivette, K., and Nelson, C. M. (2005). Breaking the school to prison pipeline: identifying school risk and protective factors for youth delinquency. Exceptionality 13, 69–88. doi: 10.1207/s15327035ex1302_2

Clarke, A. E. (2005). Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory After the Postmodern Turn, 1st Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

DeMartino, L. (2021). “Accents of positive school leadership: applying a community framework in educational spaces,” in Positive Leadership for Flourishing Schools, eds S. Cherkowski, B. Kutsyuruba, and K. Walker (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing) 77–90.