94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 08 March 2021

Sec. Special Educational Needs

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.609523

Tally Lichtensztejn Tafla1*

Tally Lichtensztejn Tafla1* Decio Brunoni1

Decio Brunoni1 Luiz Renato Rodrigues Carreiro1

Luiz Renato Rodrigues Carreiro1 Alessandra Gotuzo Seabra1

Alessandra Gotuzo Seabra1 Leandro Augusto da Silva2

Leandro Augusto da Silva2 Daiane Cristina de Souza Bastos3

Daiane Cristina de Souza Bastos3 Ana Claudia Rossi3

Ana Claudia Rossi3 Pedro Henrique Araujo dos Santos4

Pedro Henrique Araujo dos Santos4 Maria Cristina Triguero Veloz Teixeira1

Maria Cristina Triguero Veloz Teixeira1The identification of mild Intellectual Disability (ID) usually occurs late when the demands intrinsic to literacy reveal the typical signs to the educators. The study had two phases. The first phase aimed at developing a computation system (framework), named DIagnosys, an instrument designed to help educators identify students with characteristics compatible with ID, and to describe the operational, tactical, and strategic levels. The second phase verified the framework predictive sensitivity, using an artificial intelligence algorithm. For that purpose, the framework was applied in 51 teachers and their 1,758 students of 2nd and 4th grade, and their respective parents. We collected data using a checklist of signs compatible with ID, the Brief Problem Monitor (teacher and parent versions), the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, and medical evaluation. The statistical analysis using a Confusion Matrix showed an accuracy of 82 and 95% for teacher and parent checklists, respectively. The decision-making model showed high indexes of sensitivity, providing evidence that teachers can be protagonists of the teaching-learning process mobilizing the parents to use the health care services.

Intellectual disability (ID) is characterized by deficits in intellectual functions such as reasoning, problem solving, planning, abstract thinking, judgment, academic learning and learning from experience, as well as deficits in adaptive functions that hinder a variety of skills required to acquire personal independence and social responsibility in the various contexts in which a person lives (American Psychiatric Association—APA, 2013). It has a general prevalence in the population of approximately 1%, with variations according to age. Severe ID has a prevalence of about six in a thousand children (6:1,000) according to the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) of the American Psychiatric Association—APA (2013).

The signs of ID are heterogeneous and associated with multiple causes and levels of severity, which is important to establish the level of support/assistance needed, for resource allocation, the selection of individuals for research, and even for legal purposes (McNicholas et al., 2018). Prior to the DSM-5, the level of severity in ID was defined predominantly according to intellectual quotient (IQ) (Armstrong et al., 2012). After the DSM-5 publication, the levels of ID severity were established based on the assessment of adaptive functioning, making them compatible with the guidelines of organizations such as the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities and the World Health Organization (World Health Organization-WHO, 1992; American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities—AAIDD, 2006). Adaptive functioning involves adaptive reasoning in conceptual, social, and practical domains (American Psychiatric Association—APA, 2013). Deficits in adaptive functioning are characterized by limitations in the performance of daily activities, difficulties in responding to environmental changes, as well as by their effects on social participation and independence in different contexts, such as at home, at school, at work and in the community (American Psychiatric Association—APA, 2013; Oakland et al., 2013).

The emergence of signs of ID occurs in the childhood, but their identification may be early or late, depending, frequently, on the severity of the condition. Generally, in more severe cases, the first signs become evident before the start of formal education and those with less severe ID signs are usually identified later when formal education begins. For children with mild ID, signs become apparent due to the presence of deficits in the adaptive and intellectual functioning skills required for academic learning, personal independence, and social responsibility (Assis et al., 2009; (American Psychiatric Association—APA, 2013; Delobel-Ayoub et al., 2015; Bertelli et al., 2016). Thus, identification of mild ID usually occurs late, when the demands intrinsic to literacy reveal the typical signs of ID to the educational teams (Alles et al., 2019).

In countries such as the United States, government policies include routine assessment and preventive intervention for a variety of behavioral problems and cognitive deficits in children with signs of neurodevelopmental disorders, as ID for example (Rotholz et al., 2013). Brazilian public policies recommend ID diagnosis in childhood, at an early stage, as the main clinical characteristics manifest during the first years of life (Brazil, 2016; Mansour et al., 2017). However, the application of screening policies for ID identification in Brazil is still ineffective, with few epidemiological studies (Malta et al., 2016). Inclusive education is internationally recognized for providing equitable quality education to all children, especially children with ID (Kurth et al., 2018). The mild levels of ID may not be identifiable until school age, when the difficulty with academic learning becomes apparent (American Psychiatric Association—APA, 2013). However, teachers are often unable to discern between learning difficulties, borderline intellectual functioning and other factors, such as transitional difficulties of the schooling process, school adaptation, literacy, socio-emotional difficulties, immaturity, and factors related to the family environment (Ares et al., 2020). In the meantime, the teacher can try different teaching strategies, often without success and delaying or stalling the child’s development. Because of that, children with mild ID, but without formal diagnosis, are often excluded from adequate inclusive educational services in Brazilian schools.

Recent Brazilian studies (e.g., Batista and Pestun, 2019) have adopted the response to intervention model (Berkeley et al., 2020) as an alternative to the Brazilian school system to identify students with learning disabilities and to decrease the disproportionality in education. This model recommends periodic monitoring of children’s performance in order to improve learning, consolidating the function of social transformation of teachers in basic education. However, when learning disabilities are a result of neurobiological factors, like ID, students need a diagnostic assessment to be provided with inclusive educational services.

Brazilian epidemiological study (Malta et al., 2016) verified the distribution of disabilities using a national health survey of 205,000 inhabitants (children, adolescents, and adults) in all five regions of Brazil (North, Northeast, Central-West, Southeast and South). The prevalence of ID in the population was 0.8%, with no significant differences in terms of age, race/ethnicity, and region (Malta et al., 2016). Although the study used a subjective measure of evaluation, based on the reports of parents, the results highlight the need to expand access to prevention, diagnosis and early intervention for ID, associated or not to other disabilities (Malta et al., 2016). Brazil does not fully meet mental health needs in early childhood, through failure to implement public policies (Tomaz et al., 2016; Januário et al., 2017; Tafla, 2019).

In Brazil, the main health guidelines and legislation for people with ID are available in the National Health Policy for People with Disabilities (Brazil, 2010). However, there is a lack of studies that evaluate the effectiveness of implementation of these policies for issues such as prevention, promotion, diagnosis, and treatment (Tomaz et al., 2016). Supervision of child health and neurodevelopmental indicators in Brazil is part of pediatric childcare actions; however, Brazilian studies showed the urgent need to implement programs to help reduce unmet mental health needs, inequalities, and increase planning strategies to reduce barriers for mental care in the childhood (Paula et al., 2014; Fatori et al., 2019).

Brazilian pediatricians are responsible for the early identification of developmental delays in a child, and, consequently, to provide early diagnosis and intervention. However, the evaluation of ID signs does not always lead to a concrete diagnosis, because not all pediatricians incorporate developmental surveillance into routine practice (Eickmann et al., 2016). When a child with mild signs of ID starts formal schooling, but still does not have a diagnosis, the teacher can be an important educational agent to identify characteristics or behavioral patterns compatible with ID and communicate it to the parents. The child could, thus, receive a formal diagnostic assessment in the health services and proper support at school including special educational according with their needs.

The main manifestations of children with ID at school include deficits in the skills and behaviors necessary for peer relationships, deficits in cognitive skills (logical thinking, attention, and memory), difficulties in acquiring reading and numeracy skills, social skills deficits, difficulties in academic group activities, and difficulties in solving interpersonal problems (American Psychiatric Association—APA, 2013; Pereira et al., 2015; Maturana et al., 2019). These are typical manifestations of ID, which worsen with developing age and increasing demands from the social and school environment. The teacher can help to identify children with characteristics and behaviors compatible with ID, provided that the educational system offers adequate training and instruments that facilitate the identification of students potentially affected by ID. On the other hand, to avoid overloading of the teacher, innovative solutions are necessary. One problem was to develop an appropriate instrument that could enable basic education teachers to do an initial screening of ID signs, that allowed them to refer potential ID children to specialized health services for a proper diagnosis. If teachers had these tools, children should receive specialized assessments and care corresponding to their needs, both in health and educational systems (Li-Grining et al., 2010; Teixeira et al., 2020). Teachers play a fundamental role in countries such as Brazil, not for the diagnosis of ID per se—for which health care teams are responsible—, but for the identification of students with characteristics compatible with ID, in order to start a multidisciplinary action directed at the student. One innovative solution to implement assessment and decision-making process models to identify students with neurobehavioral characteristics compatible with ID is the computer technologies that model all the stages of the assessment process and test its accuracy by comparing it with gold-standard tests (Durkin et al., 2015).

Currently, concepts such as Big Data are being used more and more frequently in decision-making processes in education and other areas (Gandomi and Haider, 2015). The proliferation of computer systems for process modeling, and their deployment in different sectors of economy, education and health has caused significant changes in the way data are collected, stored and analyzed (Silberschatz et al., 2006; Turban et al., 2010). Education has already profited from Big Data environments to develop, for example, programs to stimulate learning skills (Zeide, 2017). One type of computational system that has shown significant progress are database management systems (DBMS), both in the respect of data storage and mining (Han et al., 2011; Silva et al., 2016). These DBMS function as a resource for the creation of fact or transaction repositories and, consequently, can be sources for data analysis with a focus on the generation of management reports for tracking or monitoring tasks and actions in a wide range of areas of human knowledge (Pesantes et al., 2014).

In Brazil, some studies have applied these systems to the educational sector. Digiampietri et al. (2016) used a computing environment to identify students at high risk of dropout, based on their school history in first year and other factors. Jarske et al. (2016) analyzed the results obtained from a word reading competency test using data mining techniques and developed clustering algorithms to detect groups of students who tended to make errors, either by marking all questions as correct, or by marking them all as incorrect.

For the scope of the present study, the need that has to be tackled is to identify students with cognitive and/or behavioral characteristics compatible with ID in elementary education in Brazil. For this purpose, innovative technologies, such as computer systems, can provide a decision-making model using artificial intelligence algorithms. Therefore, the present study aimed to develop and apply a framework, named DIagnosys. We use the acronym DI in the name because as a reference to Intellectual Disability (Deficiência Intelectual, in Portuguese). The specific objectives were: 1) to develop a framework (DIagnosys) to help the elementary school team to identify students with characteristic compatible with ID, and to describe the operational, tactical, and strategic levels; and 2) to apply the framework and verify its predictive sensitivity. The study had two phases that will be described below with the respective methodological procedures and results.

Phase 1. Development of the framework DIagnosys.

The framework DIagnosys has three levels—operational, tactical, and strategic—each one with specific modules, as shown in Figure 1. From bottom-up levels, the operational level comprises four modules: DIagnosys Teacher, DIagnosys Student, DIagnosys Checklist and DIagnosys ETL (extraction, transformation, and loading). These modules are responsible for the processes of registering teachers and students; evaluation of the student; and extracting, transforming, and loading data from the results of the student evaluation. The tactical level consists of the DIagnosys Manager Module that allows the monitoring of the process of implementing the student assessment by teachers using the checklist and BPM-T, specialized evaluation through intellectual functioning assessment (WASI), checklist and BPM-P filled by parent and medical evaluation. The strategic level is composed of the DIagnosys Analytics module that is responsible for implementing the artificial intelligence algorithm.

For the implementation and processing modeling of the framework we used a Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN) method. This is widely used in software engineering for process modeling and validation from the generation of a prototype to completion of the application (Dijkman et al., 2008). The BPMN provides a standard notation easily understood by non-computer science experts. Consequently, BPMN served as a common language to bridge the communication gap that often occurs between business process design and implementation.

For the operational level of the framework, we developed a flowchart (Figure 2). It was essential to establish what to do when a teacher identified a student with characteristics compatible with ID, how the parents got involved in the process as well the school’s special educational support team and how to proceed to an outcome with the case. The Figure 2 details the phases of the entire process, whose theoretical model was published in a previous study (Teixeira et al., 2020). In summary, the complete process has as input students from the public educational system and, as an output, a report with the diagnosis of ID. In this study, the authors have assumed the role of the mental health service (Health service, in Figure 2) to do the diagnostic assessment (Report with the Results of the Evaluation) and test completely the process of the Operational Level of framework.

The operational module process is represented in the flowchart of Figure 2 and begins with teachers, that were previously trained in recognizing of characteristics compatible with ID, filling the checklist. The details of this training were published in a previous study (Teixeira et al., 2020). According with Figure 2, if less than two items are given the frequencies “sometimes’, ‘often’ or ‘very often’, the student is monitored by the teacher. However, if two items are given the frequencies ‘sometimes’, ‘frequently’ or ‘very often’, the school’s special educational team execute a neuropsychological and emotional-behavioral assessment of the student with the participation of parents. Thus, if two items are completed in the parents’ checklist and the WASI test shows IQ <70, regardless of having emotional and behavioral problems, the student is referred to health services to medical diagnostic evaluation. If not, the student will be monitored by the teacher who will be attentive to changes in behavior in the classroom. To apply the DIagnosys framework, teachers and the schools’ special educational team (that counts with a psychologist to assess the intellectual functioning) participated, as well as a multidisciplinary team (authors of the study, that conducted the diagnostic evaluation of the students with characteristics compatible with ID replacing the mental health service as described in Figure 2). When the ID is confirmed, the model provides a report to the teacher outlining the main guidelines to be followed in the classroom, according to Teixeira et al. (2018).

The tactical level comprises the DIagnosys Manager module. This module was used to monitor and follow up the entire process at the operational level. The DIagnosys Manager controls registrations (students and teachers) as well as the situation of each step of the process, as shown in Figure 2.

The strategic level comprises the DIagnosys Analytics module of Figure 1. The details of this module can be seen in Figure 3. It begins with the extraction, transformation, and loading of the data collected as well as the application and validation of an artificial intelligence algorithm. Exploratory analyses are initially carried out based on these data, and then the artificial intelligence algorithm relates the characteristics compatible with ID obtained by the teacher and parent checklists with the diagnosis of the specialized team. The algorithm had the objective to test the predictive sensitivity of the recognition by teachers of characteristics compatible with ID in students. The algorithm was not the final decision maker for the diagnosis, since the formal diagnostic process was conducted by health care professionals. However, the use of the DIagnosys framework in the present study simulated the whole process to test all its stages, from the identification of the students to the final diagnostic assessment made by a multidisciplinary team, which in this case was composed by the authors of the study, instead of professionals from the health care system.

Part of this strategic level is the modeling of the predictive algorithm, which uses a dataset that contains the characteristics of a given problem and the desired response to the same problem to adjust the artificial intelligence algorithm, allowing the algorithm to make inferences about future situations (Han et al., 2011; Silva et al., 2016). This artificial intelligence algorithm was used to verify its role in the recognition of children with ID and not as a final decision maker of the diagnosis. The assumed accuracy level was 80% or more (Han et al., 2011; Silva et al., 2016) simulating the use of the algorithm in operation. In the study, the positive characteristics compatible with ID identified in the teacher and parent checklists were used as signs of the disorder and the response was the clinical confirmation of the diagnosis. The algorithm uses learning resources from the 22 cases recorded in the data set. Therefore, the artificial intelligence algorithm is able to infer what the diagnosis of the case under analysis might be if the first signs of the disorder are known.

The algorithm tested in this study was based on Association Rules (Han et al., 2011). The mechanics of the algorithm aim to assess the intersections between the characteristic of a dataset to find patterns and trends. The algorithm assumes that the presence of one characteristic implies the presence of another. For this, in the study, each checklist of student was treated as a characteristic, which were either 0 (absent/ characteristic—that the student presented ‘never’ or ‘rarely’) or 1 (present/characteristic—that the student presented, ‘sometimes’, ‘often’ and ‘very often’), and the diagnostic of the student (yes, with ID, and no, without ID). The A Priori algorithm is classically used in data mining to discover the Association Rules (Han et al., 2011). The operation takes place using a data set that, in this algorithm, are called transactions, which must be represented by a transaction identifier (TID). Therefore, for context of this work, each student is a transaction, and it has its own TID; and the characteristic are considered as items of TID or simply i and the values indicate the occurrence of (1) or not (0) of the item in the transaction, as explained previously. The A Priori algorithm is performed in two distinct modules. In the first, the number of times that each item separately appears as a TID is initially checked. Based on a minimum number of occurrences, the most frequent items are selected and then combined iteratively. Each combination is checked for the number of occurrences, and any combinations that do not satisfy a minimum frequency are eliminated. The frequency of each item in the dataset is called SUPPORT and is defined as:

(1) where X and Y are sets of items, called itemsets. The representation n(X∩Y) comes from set theory and signifies the number of elements resulting from the intersection of X with Y. Consequently, U is the universal set and n(U) is the total number of transactions that constitute the dataset. Initially the algorithm checks the items separately, and subsequently the combinations are checked. In both situations, the occurrence of the isolated or combined items is calculated. Combinations occur if minimum support (smin) is not reached. This value must be within a range between 0, when no item is present in the transaction set, and 1, in other words: 0 < smin ≤1. The result of the a priori algorithm is to present rules of the type IF-THEN. Therefore, the objective is to assume that for an item being the premise, the occurrence of a second item is obtained as a conclusion. It is also common for the generated rule to be represented by X → Y, which reads: X implies Y.

The rules generated from the A Priori algorithm must satisfy two main requirements: The rules formed must occur with a certain frequency and must be reliable. Therefore, rules with items that rarely occur are discarded when calculating the SUPPORT. In a complementary way, the generated rules must have a certain degree of validity and, therefore, must have minimal precision. The precision is calculated by CONFIDENCE index defined as:

(1) The confidence can also be interpreted as the probability P of a set of items occurring, given that one of the items occurred. That is:

(1) The CONFIDENCE index varies between 0, no probability of both itemsets occurring, and 1, maximum probability. These values are usually presented as a percentage. However, the minimum confidence must be defined as: 0 < cmin ≤ 1. The CBA Algorithm (classification based on rules) used in this research is based on the a priori algorithm. The difference is that in the data set the class attributed is assigned, and the analysis of the rules is done assuming Y only the diagnosis characteristic (Chen et al., 2006; Thabtah and Cowling, 2007; Aljuboori et al., 2016). The purpose of the CBA, in the context of this research, is to generate rules from the associations checklist items that make it possible to establish the predictive model by checking the sensitivity indicators of the items (from the rules) compared to the diagnosis (Han et al., 2011). Based on the framework DIagnosys we tested the predictive sensitivity of the algorithm to identify students with ID.

Phase 2: Results of predictive sensitivity of the framework.

The education system in Brazil for children aged 6–17 comprises elementary school (ages 6–14) and high school (ages 15–17). The setting of the study was a public educational network of a city from São Paulo state, Brazil, that has 20 elementary schools. The students in this study were specifically from 2nd grade (around 7 years old) and 4th grade (around 9 years old). The study included at least one 2nd grade teacher and one 4th grade teacher from each of the two class periods (morning and afternoon since these schools are part time) of all 20 schools. There were five schools in which the 2nd or 4th grade classes operated only in one period (morning or afternoon). Therefore, using probabilistic random selection, the initial sample comprised 73 teachers (2nd grade teachers n = 36, 4th grade teachers n = 37). Of these 73 teachers, 25 did not agree to participate, then a new random selection was carried out, totalizing a total sample size of 78 (including 5 extra teachers to predicted sample loss). However, 27 (34,6%) of the 78 teachers did not agree to participate. Then, the final sample comprised 51 teachers (2nd grade teachers n = 27, and 4th year teachers n = 24), including at least one 2nd grade and one 4th grade class per school, with a total number of 1,758 students.

Students already identified as having special educational needs according to the school records were not included in the study. The study procedures were carried out in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Mackenzie Presbyterian University (CEP/UPM No. 56001316.6.0000.0084).

a) Checklist containing 16 statements (items) that cover characteristics compatible with ID described in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association—APA, 2013) and statements about the expression of the disorder in classroom context to help the teacher in the identification of students. For the responses it was used a Likert scale with frequencies (‘never or rarely’, ‘sometimes’, ‘often’ and ‘very often’). The checklist was evaluated psychometrically by 3 experts to assess content validity. All experts had a PhD in human development, as well as clinical and teaching experience with ID. The criteria used for the content analysis of the items were objectivity, clarity and precision, as described by Pasquali (2010). We verified adequate indexes in the content analysis validity and these results as well as the checklist were published in a previous study (Teixeira et al., 2020).

b) Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) (Yates et al., 2006), that evaluates intellectual functioning of individuals from 6 to 89 years. The WASI comprises four subtests: vocabulary and similarities compose the Verbal Intelligence Quotient (VIQ), while block design and matrix reasoning compose the Performance Intelligence Quotient (PIQ). In addition, all four subtests are combined to form the Full-Scale IQ-4 Subtests. WASI provides a valid resource to measure intelligence and its possible disability in a quick and effective way. Content validity was demonstrated through the correlation with other measures and the validity construct was supported by the intercorrelations of the WASI subtests, by the IQ scales and factor analysis. The instrument was used in different clinical groups to demonstrate clinical validity, including estimation in intellectual disability (Yates et al., 2006). The advantages of WASI consist of its fast administration, good correlation with the complete versions of the Wechsler Scales and application in a wide range of ages (Yates et al., 2006).

c) Brief Problem Monitor (BPM) (Brief Problem Monitor-Teacher Form For Ages 6–18/BPM-T and (Brief Problem Monitor-Parent Form For Ages 6–18/BPM-P] (Achenbach and Rescorla, 2001), that assesses emotional and behavioral problems with three scales: internalizing, externalizing and attention problems. BPM-P and BPM-T are short-form versions of Child Behavior Checklist For Ages 6–18/CBCL and Teacher’s Report Form For Ages 6–18/TRF, respectively (Achenbach et al., 2011). The T scores of each scale is divided into two classifications: normal (T score is ≤64) and high (T score ≥65) (Achenbach and Rescorla, 2001; Achenbach et al., 2011; Bordin et al., 2013).

d) Medical evaluation. Anamnesis with parents to obtain information about the nuclear family, parental consanguinity, gestational history with scrutiny of 50 risk factors for fetal harm, milestones of the child development and health complications, up to the current age, observation of the child’s morphological phenotype, measuring head circumference and basic neurological factors such as communication, collaboration, understanding, locomotion, balance, and motor coordination.

Initially 51 teachers were selected, as it was described in “Sample and data collection”, with 27 teachers from 2nd grade and 24 from 4th grade, and a total sample of 1,758 students. Having signed the consent term, teachers participated in a 20-hour-course offered by the authors of the study, that provided information about ID that would be later instrumental in the recognition of signs compatible with ID in the students. After that, teachers filled the checklist only for students in which they recognized characteristics compatible with ID. According to the operational level of the framework, if two items are given the frequencies ‘sometimes’, ‘frequently’ or ‘very often’, the student should be assessed. For that, the parents of the indicated students were invited to participate and signed the consent term. After that, the school’s special educational team conducted the neuropsychological and emotional-behavioral assessment of the student.

Students with at least two items indicated by the parents in the checklist and the WASI test below IQ <70 were received a diagnostic evaluation by a medical professional. When the ID was confirmed also in the medical diagnostic evaluation, the student was referred to the city’s mental health system.

Descriptive analyses were conducted to characterize the student sample. The WASI, BPM-T and BPM-P data collection instruments were corrected according to their specific standardization. The Likert scale of each checklist was recoded dichotomously, with 1 indicating the presence of signs of ID, when the scale responses were ‘sometimes’, ‘often’, or ‘very often’, and with 0 when the responses were ‘never’ or ‘rarely’. To generate the predictive models that checked the sensitivity of the checklist items compared to the diagnosis, the Classification Based on Associations (CBA) algorithm (Aljuboori et al., 2016) was used. To produce the models, algorithms were established to identify the checklist items that could be classified as predictors of ID diagnosis. The choice of item parameters for filtering the rules adopted a confidence index (CI) of 80% or more (Han et al., 2011; Silva et al., 2016).

In this section we present the results of the application of the framework DIagnosys to verify its predictive sensitivity.

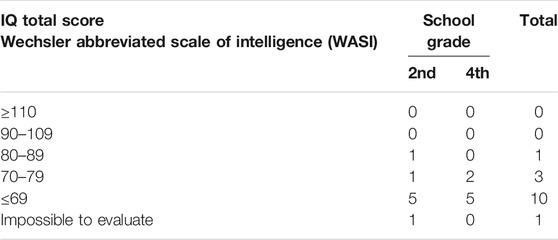

Of a total of 1,758 eligible students from the 51 classrooms, teachers identified 22 students with characteristics compatible with ID, and 15 had a confirmed diagnosis by our team after all the steps in Figure 2. Table 1 shows the distribution of the IQ classification, according to the WASI test, of the 15 students that had confirmed ID diagnosis, in each school grade. Of the total sample, the highest number (n = 10) had IQ≤ 69, and three were 70–79 IQ range. One child presented disruptive behavior and severe intellectual impairment, and the assessment was not possible.

TABLE 1. Distribution of Intelligence Quotient (IQ) classification by school grade of students with ID confirmed (n = 15).

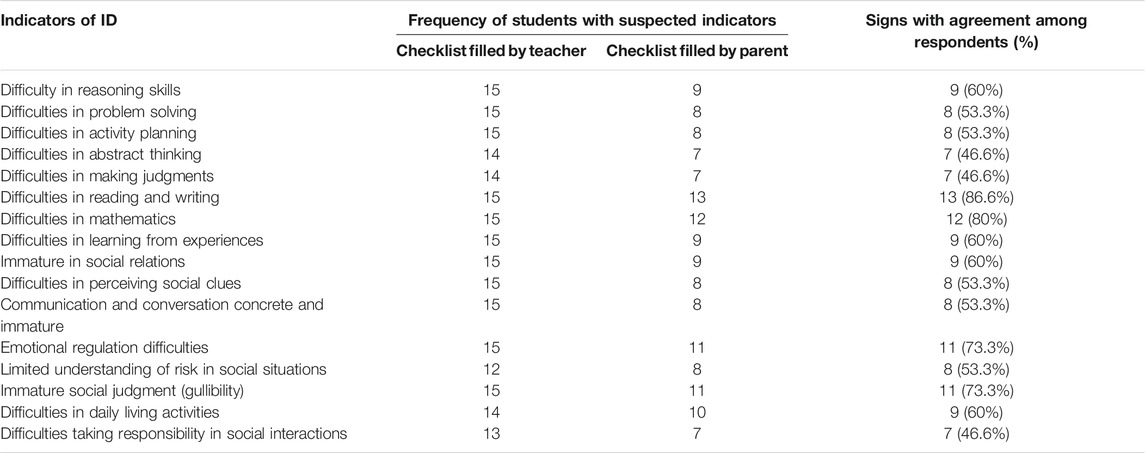

Of the children who were confirmed to have ID diagnosis, 46% were in the 4th grade, which is a late diagnosis for the age. Once again, this shows that mental health problems are not identified by pediatricians and health professionals in Brazil during the monitoring of these children in early childhood, even with the recommendation by the Ministry of Health (Brazil, 2016). Table 2 shows the checklist items completed by the teacher and the caregiver, related to the characteristics compatible with ID of the 15 students, according to DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association—APA, 2013).

TABLE 2. Distribution of items assigned as characteristics compatible with ID according to the checklists completed by the teacher and parent/caregiver (n = 15).

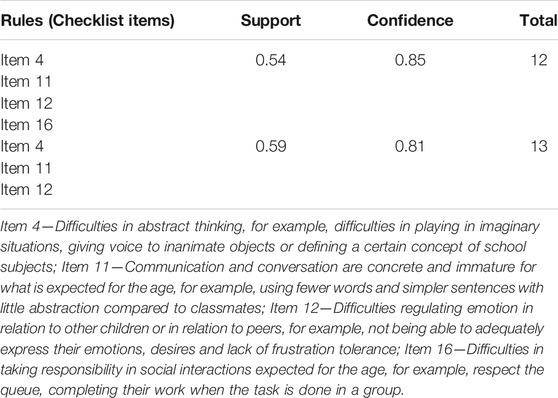

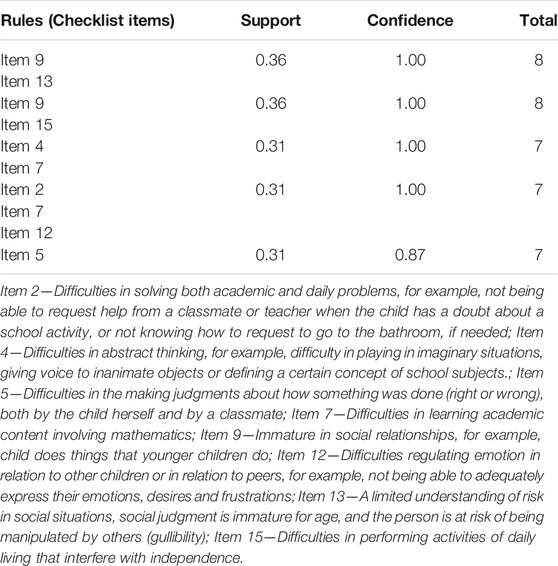

As a result of the CBA (Classification Based on Association Rules) algorithm, two or more rules were found, both from parents’ and teachers’ responses to checklists. According with Table 3 in 54% of the times that items 4, 11, 12 and 16 appeared together on the teacher ID checklist, the CONFIDENCE index for the student to actually have an ID diagnosis was 85%; when items 4, 11 and 12 appeared together, which occurred 59% of the time, the CONFIDENCE index was 81%. Items 4, 11 and 12 were checklist characteristics that showed a high probability of indicating a diagnosis for ID. These items describe, respectively, difficulty in abstract thinking, concrete and immature communication for their age, and difficulty in emotional regulation in relationships with other children through the expression of emotions and feelings—difficulties described as being in the social area according to the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association—APA, 2013). It was remarkable to note that teachers can be an educational agent of the teaching-learning process and improve the parent’s awareness about the child difficulties, when this is not previously done by pediatricians, especially in cases of mild to moderate ID.

TABLE 3. Items of the ID checklist completed by teachers which generated rules of the sensitivity predictor algorithm compared to the diagnosis.

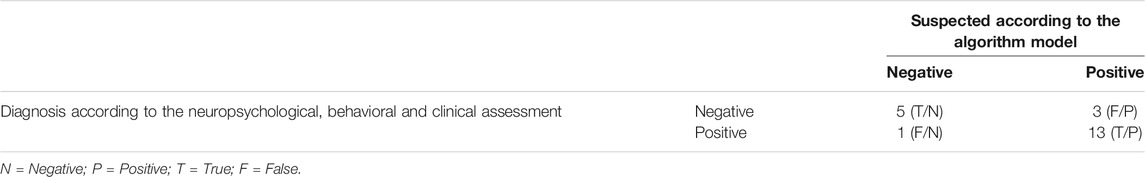

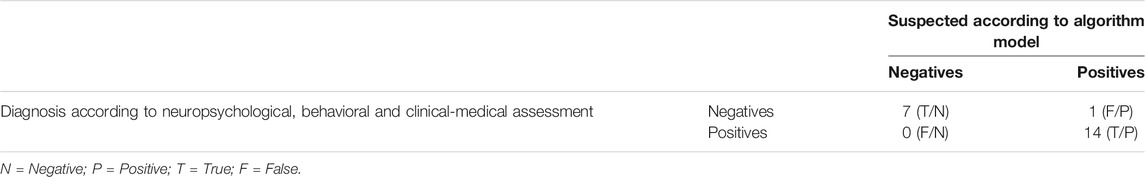

A confusion matrix was also generated (Han et al., 2011; Silva et al., 2016), which analyzed the accuracy of the algorithm model, by matching the positive diagnosis made through the neuropsychological, behavioral and clinical-medical evaluation, and the prediction model of the algorithm from the teachers’ ID checklist. This matrix showed that the proposed model had an accuracy of 82%, as shown in Table 4, identifying only one false-negative and three false-positive cases. The model proved to be an accurate predictor for 13 students, that is when positive scores indicated that the child will most likely have ID and, in fact, these 13 students confirmed the diagnosis. The false negative (1 student) and false positive cases (3 students) showed that the model still needs to be improved by increasing the sample number considering the phenotypic variability that characterizes ID at different levels of severity.

TABLE 4. Confusion matrix for comparing false-positive and false-negative cases by matching the model developed using the algorithm (from the teachers’ checklist) with results from the neuropsychological, behavioral and clinical-medical evaluation.

The ID checklist for parents generated more homogeneous rules (table 5). In 36% of the cases when items 9 and 13, and items 9 and 15 were marked together, the confidence index of the diagnosis confirmed as positive was 100%. When items 4 and 7, and items 2, 7 and 12 were indicated together in the ID checklist, which occurred 31% of the times, the confidence index for a positive diagnosis was also 100%. Only when item 5 was indicated alone, which occurred 31% of the times, did the confidence for an ID confirmation drop to 87%.

TABLE 5. Items from the ID checklist completed by parents which generated rules of the sensitivity predictor algorithm compared to the diagnosis.

The Confusion Matrix generated for the parent checklist showed an accuracy of 95%, as shown in Table 6, without false-negatives, and only one false positive. Items 7 and 9 of the checklist proved to be the most sensitive according to the parents for the subsequent diagnosis of ID. These items describe problems in skills related to learning academic content involving mathematics, and immaturity in social relationships—doing things that younger children do. These items correspond, respectively, to the conceptual and social domains described in DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association—APA, 2013), which may indicate greater sensitivity on the part of the caregivers responsible for identifying the child’s difficulties in such domains.

TABLE 6. Confusion matrix for comparing false-positive and false-negative cases by matching the model developed by the algorithm (from the parent checklist) with results from the neuropsychological, behavioral and clinical-medical evaluation.

Confusion Matrix accuracy index generated by the parents’ checklist (95%, Table 6) was higher than the index generated by the teachers’ checklist (85%, Table 4). As it is the case in other countries, (Núñez et al., 2019), in Brazil public policies recommend pedagogical practices adopt the use of homework in all levels of education (Resende et al., 2018). Homework has two basic forms: a) activities related to the educational curriculum for fixation of learning skills through exercises and reading practice; b) educational activities that involve parents and other family members to enrich the curriculum with everyday activities. This enables parents to actively participate in the education and reinforce the learning of skills by their children. It also enables parents to identify whether children have skills that match the completion of homework activities. On the other hand, parents can also assess the level of adaptive functioning of the child to accomplish social or practice demands of everyday life in family environment. Thus, parents can have a privileged role in the recognition of adaptive deficits both in academic functioning and in social and practical areas related to the identification of behavioral patterns compatible with ID (American Psychiatric Association—APA, 2013). It is likely that this privileged position contributed to the higher accuracy of the Confusion Matrix generated by the parents’ checklist, even though teachers were the ones who received special training. However, the study showed that, despite this higher accuracy level, parents of the sample did not seek for help in mental health facilities. Previous Brazilian studies show that the lack of access to mental health services as well low level of education of parents can hinder the recognition of deficits as possible neurodevelopmental disorders (Paula et al., 2014; Fatori et al., 2019).

According to previous studies, parents may recognize behaviors compatible with ID, but deny them for fear, especially in cultures in which disabilities can be highly stigmatized (Robertson et al., 2012.; Ali et al., 2013). Additionally, although parents are able to identify characteristics compatible with ID, they refrain from considering these behaviors as difficulties or deficits, but, instead, as children’s peculiarities, which would explain the low indication of problems according to the parents found in the present study. Even so, parental concern is considered a useful clinical tool in the diagnosis, being the first agent in terms of noticing the condition and seeking medical services (Robertson et al., 2012; Bertelli et al., 2016). Teachers also perform an essential role in relation to students with characteristics compatible with ID.

It is important to note that the use of the DIagnosys framework is a challenge since, while, students with special educational needs are entitled to educational and health assistance, programs aimed at identifying and supporting these students are still scarce in Brazil. Therefore, despite the Brazilian public policies recommend early ID diagnosis in childhood (Brazil, 2016; Mansour et al., 2017), students often remain undiagnosed even at school age. Furthermore, although parents can identify characteristics compatible with ID (see their answers in the checklist), they do not consider these behaviors as difficulties or deficits, but, instead, as children’s peculiarities. In this scenario the school team is extremely important, not for the diagnosis of intellectual disability (ID) per se, but for identification of students with characteristics compatible with ID, in order to start a multidisciplinary action directed at the student. Having a diagnosis is crucial for the ulterior psychological and educational development of children with ID, since it entitles them to access specialized health and educational services.

Therefore, this study provided teachers with tools to carefully observe students with characteristics compatible with ID and, based on these observations, they can refer them to specialized health services for a formal diagnostic evaluation. Also, this study offers an opportunity for the teacher to inform parents about the child’s difficulties at school, so that they use health services for an adequate diagnosis avoiding student stigmatization at school. Only after the confirmation of the diagnosis, children are covered by the Brazilian law and can receive specialized educational assistance at school. In this way, students can receive suitable care, be properly assessed if necessary, and take part in health and education systems that can offer conditions for their development, not only at a cognitive and academic level, but also in terms of social and emotional development and support for the students’ families.

The study verified the sensitivity indicators of a decision-making model for the identification of students with ID by elementary school teachers, with the aid of a computer system. One of the main objectives of the study was to apply the framework DIagnosys in educational network to verify its predictive sensitivity. The results revealed that, of a total of 1,758 eligible students, 22 were identified by the teachers as showing characteristics compatible with ID. These students started the formal education without any type of diagnostic assessment or curricular adaptation, because the Brazilian legislation requires a medical diagnosis so that the student with ID can receive the benefits of special education. Despite a sample loss of 30% of students, 15 of the students identified by the teachers were confirmed to have ID through a medical and neuropsychological examination (46% in the 4th year and 56% in the 2nd year, with 66.6% of the total of students with IQ ≤69 by the WASI). A late diagnosis can have a significant impact on school performance, and it is often associated with impaired adaptive functioning and delay in the development of social skills. The students had emotional and behavioral problems according to parents and teachers. Teachers recognized a greater number of characteristics compatible with ID in students who had a confirmed diagnosis than did the parents.

The ID checklist developed for the study showed to have enough sensitivity to identify cases of ID. However, there is a limitation regarding a diagnosis of ID using the DSM-5 recommendations, since a gold standard assessment of adaptive behaviors, such as ABAS-3, for example, was not used (Harrison and Oakland, 2015). The items on the ID checklist completed by the teachers and parents that showed the greatest predictive power in comparison to the diagnosis were related to the DSM-5 criteria of ID in the conceptual and social domains. The results highlight the need for public policies that recommend the monitoring of the cognitive and emotional-behavioral functioning of school-age children. A limitation of the study is the size of the teacher sample, but despite this, it can set objectives for future studies aimed at the development of predictive models with other checklists with even greater reliability and sensitivity compared with the clinical diagnosis of other neurodevelopmental disorders as dyslexia, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, or Autism Spectrum Disorder. As it was done with the teachers, parents should also receive training to identify characteristics compatible with neurodevelopmental disorders in their children.

Despite the small sample size, the results of CBA algorithm were acceptable, since with only 22 children of a eligible sample of 1,758, the algorithm correctly identified 85% of ID cases, with a satisfactory screening by the teachers. Since the final diagnostic decision is to be made by a team of experts, the cases that were wrongly classified by the algorithm (false negative or false positive) will be assessed by this team for the formal medical diagnosis. The results of this stage were not part of this study due to the suspension of in-person classes in Brazilian schools because of the COVID-19 pandemic. This step is scheduled to take place in February 2021.

A further limitation of the study is that the children identified were not followed up in the mental health services of the municipality to establish whether they received the necessary care and interventions. However, despite these limitations, the study shows the possibilities of a more effective use of public education services, so that students with characteristics compatible with ID could receive early assessment and intervention to ensure cognitive development, social and school functioning that provide more benefit for their family, social and academic life.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Mackenzie Presbyterian University (CEP/UPM NÂo. 56001316.6.0000.0084). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

TT: Investigation, Writing—Original Draft. DB: Formal analysis, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing. LC: Methodology, Resources, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing. AS: Methodology, Resources, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing. LS: Methodology, Software, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing. DB: Software, Writing—Original Draft. AR: Methodology, Software, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing. PS: Investigation, Writing—Original Draft. MT: Term, Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding acquisition.

This study was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES/ Master-Fellowship), the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo/FAPESP (grant number 01063, 2018), and the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico/CNPq (Grant Number 408808, 2016).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Achenbach, T. M., McConaughy, S. H., Ivanova, M. Y., and Rescorla, L. A. (2011). Manual for the ASEBA brief problem monitor (BPM). Burlington, VT: ASEBA, 1–33.

Achenbach, T. M., and Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the Aseba school-age forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: ASEBA.

Ali, A., Scior, K., Ratti, V., Strydom, A., King, M., and Hassiotis, A. (2013). Discrimination and other barriers to accessing health care: perspectives of patients with mild and moderate intellectual disability and their carers. PLoS ONE 8 (8), e70855. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070855

Aljuboori, A., Meziane, F., and Parsons, D. (2016). “A new strategy for case-based reasoning retrieval using classification based on association,” in Machine learning and data mining in pattern recognition. Lecture notes in computer science. Editor P Perner (Berlin: Springer). doi:10.1007/978-3-319-41920-6_24

Alles, E. P., Castro, S. F., Menezes, E. C. P., and Dickel, C. A. G. (2019). (Re)Significações no Processo de Avaliação do Sujeito Jovem e Adulto com Deficiência Intelectual. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial 25 (3), 373–388. doi:10.1590/s1413-65382519000300002

American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities—AAIDD (2006). World’s oldest organization on intellectual disability has a progressive name change.

American Psychiatric Association—APA (2013). Diagnostic and statistical Manual of mental disorders. Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA.

Ares, E. M. T., Souto, P. M. I., Gómez, S. L., and Torres, R. M. R. (2020). Neurodevelopmental difficulties as a comprehensive category of learning disabilities in children with developmental delay: a systematic review. Anales De Psicología/Annals Psychol. 36 (2), 271–282. doi:10.6018/analesps.347741

Armstrong, K., Hangauer, J., and Nadeau, J. (2012). “Use of intelligence tests in the identification of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities,” in Contemporary intellectual assessment: theories, tests and issues. Editors D. Flanagan, and P. L. Harrison (New York: The Guilford Press).

Assis, S. G., Avanci, J. Q., and Oliveira, R. D. V. C. D. (2009). Desigualdades socioeconômicas e saúde mental infantil. Revista de Saúde Pública 43, 92–100. doi:10.1590/S0034-89102009000800014

Batista, M., and Pestun, M. S. V. (2019). O Modelo RTI como estratégia de prevenção aos transtornos de aprendizagem. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional 23, e205929. doi:10.1590/2175-35392019015929

Berkeley, S., Scanlon, D., Bailey, T. R., Sutton, J. C., and Sacco, D. M. (2020). A snapshot of RTI implementation a decade later: new picture, same story. J. Learn. Disabil. 53 (5), 332–342. doi:10.1177/0022219420915867

Bertelli, M. O., Munir, K., Harris, J., and Salvador-Carulla, L. (2016). “Intellectual developmental disorders”: reflections on the international consensus document for redefining “mental retardation-intellectual disability” in ICD-11. Adv. Ment. Health Intellect. disabilities 10 (1), 36–58. doi:10.1108/amhid-10-2015-0050

Bordin, I. A., Rocha, M. M., Paula, C. S., et al. (2013). Child behavior checklist (CBCL), Youth self- report (YSR) and Teacher’s report form (TRF): an overview of the development of the original and Brazilian versions. Caderno de Saúde Pública 29 (1), 13–28. doi:10.1590/S0102-311X2013000500004

Brazil. (2010). Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas Estratégicas. Política Nacional de Saúde da Pessoa com Deficiência. DF: Secretaria-Executiva. Brasília, 12p.

Brazil. (2016). Cartilha para apresentação de propostas ao Ministério da Saúde. DF: Secretaria-Executiva. Brasília, 172p

Chen, G., Liu, H., Yu, L., Wei, Q., and Zhang, X. (2006). A new approach to classification based on association rule mining. Decis. Support Syst. 42 (2), 674–689. doi:10.1016/j.dss.2005.03.005

Delobel-Ayoub, M., Ehlinger, V., Klapouszczak, D., Maffre, T., Raynaud, J.-P., Delpierre, C., et al. (2015). Socioeconomic disparities and prevalence of autism Spectrum disorders and intellectual disability. PLoS ONE 10 (11), 113. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141964

Digiampietri, L. A., Nakano, F., and Lauretto, M. (2016). Mineração de Dados para Identificação de Alunos com Alto Risco de Evasão: Um Estudo de Caso. Revista De Graduação USP 1 (1), 17–23. doi:10.11606/issn.2525-376X.v1i1p17-23V

Dijkman, R. M., Dumas, M., and Ouyang, C. (2008). Semantics and analysis of business process models in BPMN. Inf. Softw. Technol. 50 (12), 1281–1294. doi:10.1016/j.infsof.2008.02.006

Durkin, M. S., Elsabbagh, M., Barbaro, J., Gladstone, M., Happe, F., Hoekstra, R. A., et al. (2015). Autism screening and diagnosis in low resource settings: challenges and opportunities to enhance research and services worldwide. Autism Res. 8 (5), 473–476. doi:10.1002/aur.1575

Eickmann, S. H., Emond, A. M., and Lima, M. (2016). Evaluation of child development: beyond the neuromotor aspect. Jornal de pediatria 92 (3), 71–83. doi:10.1016/j.jped.2016.01.007

Fatori, D., Salum, G. A., Rohde, L. A., Pan, P. M., Bressan, R., Evans-Lacko, S., et al. (2019). Use of mental health services by children with mental disorders in two major cities in Brazil. Psychiatr. Serv. 70 (4), 337–341. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201800389

Gandomi, A., and Haider, M. (2015). Beyond the hype: Big data concepts, methods, and analytics. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 35 (2), 137–144. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2014.10.007

Harrison, P. L., and Oakland, T. (2015). Adaptive behavior assessment system manual. 3rd ed. Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Januário, S. S., Peixoto, F. S. N., Lima, N. N., et al. (2017). Mental health and public policies implemented in the Northeast of Brazil: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 63 (1), 21–32. doi:10.1177/0020764016677557

Jarske, J. M., Seabra, A., and Silva, L. A. (2016). “O uso de mapas auto-organizáveis como ferramenta de Análise Exploratória para Testes Cognitivos destinados a medir o Desempenho Escolar CBIE,” in Anais dos Workshops do V Congresso Brasileiro de Informática na Educação. doi:10.5753/cbie.wcbie.2016.1009

Kurth, J., Miller, A., Toews, S. G., Thompson, J., Córtes, M., Dahal, M., et al. (2018). Inclusive education: perspectives on implementation and practice from international experts. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 56, 471–485. doi:10.1352/1934-9556-56.6.471

Li-Grining, C. P., Votruba-Drzal, E., Maldonado-Carreño, C., and Haas, K. (2010). Children’s early approaches to learning and academic trajectories through fifth grade. Dev. Psychol. 46 (5), 1062–1077. doi:10.1037/a0020066

Malta, D. C., Santos, M. A. S., Stopa, S. R., Vieira, J. E. B., Melo, E. A., and Reis, A. A. C. (2016). A Cobertura da Estratégia de Saúde da Família (ESF) no Brasil, segundo a Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde, 2013. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva. 21 (2), 327–338. doi:10.1590/1413-81232015212.23602015

Mansour, R., Dovi, A. T., Lane, D. M., Loveland, K. A., and Pearson, D. A. (2017). ADHD severity as it relates to comorbid psychiatric symptomatology in children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD). Res. Dev. Disabil. 60, 52–64. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2016.11.009

Maturana, A. P. P. M., Mendes, E. G., and Capellini, V. L. M. F. (2019). Schooling of students with intellectual disabilities: family and school perspectives. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto) 29, e2925. doi:10.1590/1982-4327e2925

McNicholas, P. J., Floyd, R. G., Woods, I. L., Singh, L. J., Manguno, M. S., and Maki, K. E. (2018). State special education criteria for identifying intellectual disability: a review following revised diagnostic criteria and Rosa's Law. Sch. Psychol. Q. 33 (1), 75–82. doi:10.1037/spq0000208

Núñez, J. C., Regueiro, B., Suárez, N., Piñeiro, I., Rodicio, M. L., and Valle, A. (2019). Student perception of teacher and parent involvement in homework and student engagement: the mediating role of motivation. Front. Psychol. 10, 1384. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01384

Oakland, T., Iliescu, D., Chen, H.-Y., and Chen, J. H. (2013). Cross-national assessment of adaptive behavior in three countries. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 31 (5), 435–447. doi:10.1177/0734282912469492

Paula, C. S., Bordin, I. A. S., Mari, J. J., Velasque, L., Rohde, L. A., and Coutinho, E. S. F. (2014). The mental health care gap among children and adolescents: data from an epidemiological survey from four Brazilian regions. PLoS ONE 9 (2), e88241. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088241

Pereira, A. M., Araújo, C. R., Ciasca, S. M., and Rodrigues, S. D. D. (2015). Avaliação da memória em crianças e adolescentes com capacidade intelectual limítrofe e deficiência intelectual leve. Revista Psicopedagogia 32 (99), 302–313. doi:10.14393/ufu.di.2019.2142

Pesantes, M., Becerra, J. L., and Lemus, C. A.(2014). “Method to design a software process architecture in a multimmodel environment. An overview,” in Agile estimation techniques and innovative approaches to software process improvement. Editors et al. (Hershey, PA: IGI Global), 219–242.doi:10.4018/978-1-4666-5182-1.ch013

Resende, T. F., Canaan, M. G., Reis, L. S., Oliveira, R. A., and Souza, T. C. S. (2018). Dever de Casa e Relação com as Famílias na Escola de Tempo Integral. Educação Realidade 43 (2), 435–456. doi:10.1590/2175-623662458

Robertson, J., Hatton, C., Emerson, E., and Yasamy, M. T. (2012). The identification of children with, or at significant risk of, intellectual disabilities in low‐and middle‐income countries: a review. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 25 (2), 99–118. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3148.2011.00638.x

Rotholz, D. A., Moseley, C. R., and Carlson, K. B. (2013). State policies and practices in behavior supports for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities in the United States: a national survey. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 51 (6), 433–445. doi:10.1352/1934-9556-51.6.433

Silberschatz, A., Korth, H. F., and Sudarshan, S. (2006). Sistema de Banco de Dados. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Silva, L. A., Peres, S. M., and Boscarioli, C. (2016). Introdução à Mineração de Dados com aplicações em R. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Tafla, T. L. (2019). Indicadores de sensibilidade de dois modelos de tomada de decisão para identificação de alunos com Transtorno do Espectro Autista e deficiência intelectual no ensino fundamental I. [Master’s thesis]. São Paulo, SP: Mackenzie Presbyterian University.

Teixeira, M. C. T. V., Carreiro, L. R. R., Seabra, A. G., da Silva, L. A., Rossi, A. C., Tafla, T. L., et al. (2020). Modelo de tomada de decisão para uso de professores do ensino fundamental na identificação de Autismo e Deficiência Intelectual. ETD-Educação Temática Digital 22 (1), 106–126. doi:10.20396/etd.v22i1.8655539

Teixeira, M. C. T. V., Schmidt, C., Faria, K. T., Pires, R. A. D., and Carreiro, L. R. R. (2018). “A Deficiência Intelectual no contexto educacional: orientações para a atuação de professores da Educação Básica,” in Distúrbios do Desenvolvimento: estudos interdisciplinares. Editors C. A. H. Amato, D. Brunoni, and P. S. Boggio (São Paulo, SP: Memnon), 233–241.

Thabtah, F. A., and Cowling, P. I. (2007). A greedy classification algorithm based on association rule. Appl. Soft Comput. 7 (3), 1102–1111. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2006.10.008

Tomaz, R. V., Rosa, T. L., Van, D. B., and Melo, D. G. (2016). Políticas públicas de saúde para deficientes intelectuais no Brasil: uma revisão integrativa. Cien Saude Colet 21 (1), 155–172. doi:10.1590/1413-81232015211.19402014

Turban, E., Rosa, T. L., Van, D. B., and Melo, D. G. (2010). Tecnologia da Informação para Gestão: Transformando os Negócios na Economia Digital. São Paulo, SP: Bookman.

World Health Organization-WHO (1992). International statistical classification of disease and related health problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). Geneva: World Health Organization.

Yates, D. B., Trentini, C. M., Tosi, S. D., Corrêa, S. K., Poggere, L. C., and Valli, F. (2006). Apresentação da escala de inteligência Wechsler abreviada (WASI). Avaliação Psicológica 5 (2), 227–233. doi:10.14393/ufu.di.2001.46

Keywords: business process management system, data analytics, artificial intelligence, decision-making process, intellectual disability

Citation: Tafla TL, Brunoni D, Carreiro LRR, Seabra AG, Silva LAd, Bastos DCdS, Rossi AC, Santos PHAd and Teixeira MCTV (2021) DIagnosys: An Analytical Framework for the Identification of Elementary School Students with Intellectual Disability. Front. Educ. 6:609523. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.609523

Received: 10 November 2020; Accepted: 13 January 2021;

Published: 08 March 2021.

Edited by:

Gregor Ross Maxwell, Arctic University of Norway, NorwayReviewed by:

Nina Klang, Uppsala University, SwedenCopyright © 2021 Tafla, Brunoni, Carreiro, Seabra, Silva, Bastos, Rossi, Santos and Teixeira. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tally Lichtensztejn Tafla, dGFmbGEudGFsbHlAZ21haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.