- University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, United States

Framed by symbolic interactionism, this study used narrative inquiry to share a teacher’s story about her decision to pursue and depart the teaching profession within four years of graduating from a traditional undergraduate preparation program in the Midwest United States. The participant, “Banjo,” participated in a qualitative analysis that consisted of four interviews conducted during the first year following her departure from the field. Findings revealed several conflicts surrounding Banjo’s sense of pre- and in-service teacher identity and teacher preparation experiences that ultimately influenced her decision to leave the teaching profession. Banjo’s story provides critical insights about how to prevent similar challenges among early-career practitioners and facilitate progressive change in preservice teacher education writ large.

Introduction

For decades, research has shown that early-career teachers are at the greatest risk for leaving the field within their first 5 years of teaching (Shen, 1997; Darling-Hammond, 1999; Achinstein, 2006; Kersaint et al., 2007; Ulvik et al., 2009; Schaefer, 2013; Lindqvist et al., 2014; Schaefer et al., 2014; Kelchtermans, 2017; Newberry and Allsop, 2017; Hester et al., 2020; Perryman and Calvert, 2020; Ramos and Hughes, 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). While some research suggests that turnover is highest among beginning teachers who quickly become overwhelmed by the realities of the profession that may conflict with their preservice expectations (see Borman and Dowling, 2008; Guarino et al., 2006; Ingersoll, et al., 2014), corresponding studies suggest that high rates of teacher exodus may result from the emotional labor involved with early-career teachers’ emerging professional identities (Schutz and Pekrun, 2007; Schutz and Zembylas, 2009; Nichols et al., 2017).

The present study used narrative inquiry to learn from Banjo, a previous early childhood practitioner, as she shared her experiences as a student, preservice teacher (PST), teacher candidate, and early-career teacher, all of which influenced her decision to leave the teaching profession after four years in the field. In seeking to understand Banjo’s experiences, the researcher investigated the following questions: What stories does Banjo tell about her teacher preparation and pre/in-service teaching experiences? What factors influenced Banjo’s decision to pursue and depart the teaching profession? By interpreting, honoring, and retelling Banjo’s oral accounts of her interactions with family, friends, students, teacher educators, supervisors, and mentor teachers, Banjo’s story provides valuable insights into the factors that impacted her personal, professional, and situational dimensions of identity (Day and Kington, 2008), as well as challenged her willingness to sustain her commitment to teaching.

Theoretical Framework

This study used symbolic interactionism as a theoretical framework to better understand Banjo’s decision to pursue and depart the teaching profession within four years of graduating from a traditional undergraduate teacher preparation program. Symbolic interactionism is a distinctive approach used to study human group life and human conduct (Blumer, 1969). Researchers such as George Herbert Mead, John Dewey, W. I. Thomas, Robert E. Park, William James, Charles Horton Cooley, Florian Znaniecki, James Mark Baldwin, Robert Redfield, and Louis Wirth have used symbolic interactionism to understand how people make sense of and assign meaning to the world around them (Blumer, 1969). Zeegers and Barron (2015) connect symbolic interactionism to the idea that humans are constructors of their own actions and meanings; that is, “individuals construct their own social realities and perspectives of their world using responses from the environment and different sociocultural relationships with which they interact” (p. 61). As people make sense of their world through ongoing interactions, they employ a variety of aspects developed throughout the course of their lives in a multiplicity of contexts (Zeegers and Barron, 2015).

Symbolic interactionism emphasizes human agency—or the thoughts and actions people take to express their individual power—as a major factor in a teacher’s construction of identity (Sudtho et al., 2015). Moreover, symbolic interactionism suggests that a teacher’s construction of professional identity develops through their interactions with students, teachers, administrators, and other active agents that influence their behaviors and responses (Blumer 1969; Sudtho et al., 2015). As such, understanding a teacher’s individual identity requires in-depth observations and investigations into how teachers assign meaning in their environments (Sudtho et al., 2015).

Symbolic interactionism aligns with this study’s methodology, narrative inquiry, which “links the exploration of a teacher’s identity with that individual’s unique experiences” (Sudtho et al., 2015, p. 1155). Providing the theoretical underpinning for this study’s investigation, symbolic interactionism offered profound insights into how Banjo interpreted, constructed, and applied meanings to her personal, professional, and situated dimensions of identity throughout her experiences as a student, pre/in-service teacher, and, ultimately, a retired practitioner.

Literature Review

High turnover among early childhood educators is a long-standing problem in the United States. In 2004, the national annual turnover rate for all early childhood teachers was over 30% (National Association for the Education of Young Children, 2004). More recently, researchers at the Buffet Early Childhood Institute collected data from 166 licensed childcare centers in Nebraska and found “The average turnover rate was 26% in childcare settings, 15% in PreK settings, and 16% in K-3 settings. Within childcare, annual turnover was 36% for assistant teachers and 17% for lead teachers” (Roberts et al., 2018, p. 3).

In the context of preparing early childhood teachers for a field with high attrition, Chang-Kredl and Kingsley (2014) researched PSTs’ identity expectations and reasons for entry into the profession based on prior experiences to better understand the linkage between PSTs’ memories of “who they were” and “who they wish to be” (p. 27). Findings indicated that PSTs referred to memories of school, home, and prior work as reasons for entering the profession. As such, Chang-Kredl and Kingsley (2014) considered what the data revealed about PSTs’ identity expectations and the potential implications of those expectations on early childhood teacher preparation.

Most PSTs begin their teacher education programs with “various images of teaching and themselves as teachers” which largely develop as a result of their schooling experiences and individual concepts of self, or professional identity (Chong et al., 2011, p. 50). As PSTs interact with others in academic and professional contexts, these images, experiences, and self-perceptions begin to shape a teacher’s identity (Chong et al., 2011). Day and Kington (2008) argue that teacher identity is made up of three dimensions—professional identity, situated identity within a school or classroom, and personal identity—all of which affect one’s “sense of purpose, self-efficacy, motivation, commitment, job satisfaction, and effectiveness” (Day et al., 2006, p. 601). The professional dimension is influenced by the policies and social trends that constitute a “good” or effective teacher, the situated dimension is affected by the school and classroom environment or immediate working context, and the personal dimension is linked to feedback or expectations from family and friends outside of school (Day and Kington, 2008; Chong et al., 2011). Across all three dimensions, maintaining and controlling various emotions is an integral part of teachers’ identity work (Yuan and Lee, 2016), and such emotional labor can dichotomize a teacher’s personal identity (human being) and professional identity (“ideal” or model teacher) (Shapiro, 2010; Yuan and Lee, 2016). PSTs’ early preparation experiences begin to form their dimensions of identity which, in turn, informs their decisions about practice and what it means to be a teacher (Beijaard et al., 2004). Therefore, in order to avoid “transition shock”—or shock experienced by new teachers in the abrupt identity transition from student to young professional (Corcoran, 1981, p. 19)—it is essential for preservice programs to address PSTs’ expectations of teaching vs. the realities that often transpire, so that early-career teachers are well-prepared to effectively attend to challenging circumstances and continually develop their skills (Gratch, 2001; Kelchtermans and Ballet, 2002; Chong et al., 2011).

While previous studies on early-career teacher attrition (see Gold, 1985; Huberman, 1989; Beer and Beer, 1992; Kagan, 1992; Kushman, 1992) focus on teachers adapting to a new and stressful professional role rather than negotiating a new professional identity (Clandinin et al., 2015), recent research (see Lovett and Davey, 2009; McNally et al., 2009; Schaefer, 2013; Schaefer et al., 2014; Hong and Cross Francis, 2020) explores how early-career teachers develop and make sense of their identities using values and lessons learned from prior influences, initial teacher training, and school contexts (Flores and Day, 2006). In considering the ongoing negotiation of teacher identities across personal and professional contexts, Clandinin et al. (2009) emphasizes the importance of extending beyond support and working from a narrative view of teacher identity as stories to live by, which attend to early-career teachers’ experiences as an identity making process (Connelly and Clandinin, 1999; Mansfield et al., 2014; Clandinin et al., 2015). As narrative researchers of teacher education, Clandinin and Connelly (1998) illuminate the value of viewing teacher knowledge in terms of life history: “These stories, these narratives of experience, are both personal—they reflect a person's life history—and social—they reflect the milieux, the contexts in which teachers live” (p. 150).

Research also suggests that preservice and early-career teachers may experience challenges while attempting to reconcile learned teacher preparation practices with the realities of their in-service teaching roles and responsibilities (Chong et al., 2011; Danielewicz, 2001; Day and Kington, 2008; Smagorinsky et al., 2004; Steffy et al., 2000; Karalis Noel, 2020a). Because pre/in-service teachers hold implicit beliefs and identities about their teaching roles and responsibilities (Korthagen, 2004; Bucholtz and Hall, 2005), these identities influence teachers’ reflections about their practice and reactions to their teacher preparation experiences (Chong et al., 2011).

Methodology

This study used narrative inquiry to better understand Banjo’s decision to pursue and depart the teaching profession within four years of graduating from a traditional undergraduate preparation program. Data acquired through narrative research is generally open to interpretation which “develops through collaboration of researcher and respondent or storyteller and listener” (Joyce, 2015, p. 40). Introduced by Connelly and Clandinin (1990), narrative inquiry is used to understand personal human perspectives in an effort to build larger frames of reference to assess assumptions, guide action, and initiate social and cultural change (Gill, 2001). Further, narrative inquiry facilitates researcher-participant conversations and addresses and develops the processes and patterns that socially construct participants’ perceptions of reality (Gill, 2001). By using narrative inquiry as a method for telling and retelling the stories of novice and experienced teachers, researchers have the opportunity to discover meaning through patterns, motifs, and archetypes (Clandinin, 2007) in order to unearth new ways of knowing in teaching and learning (Witherell and Noddings, 1991; Clandinin and Connelly, 1996; Connelly and Clandinin, 1999; Clandinin et al., 2006).

This movement [toward life stories] is championed by Bruner (1986, 1987, 1990, 1991), the cognitive psychologist who has illustrated that personal meaning (and reality) is actually constructed during the making and telling of one’s narrative, that our own experiences take the form of the narratives we use to tell about them, and that stories are our way of organizing, interpreting, and creating meaning from our experiences while maintaining a sense of continuity through it all (Clandinin, 2007, p. 232).

Researcher’s Role

When the researcher met Banjo through an old college friend and learned that she would not return to teaching the following school year, the researcher recognized that Banjo had an important story to tell. As a result, the researcher created this narrative inquiry as the first step of a larger study examining teacher attrition to learn from Banjo’s experiences and use her story to provide insights about how to prevent early-career transition shock and teacher resignation. The researcher obtained IRB approval during summer 2019 and scheduled the first interview with Banjo via email, who was eager to share her story and contribute to teacher education research.

The Participant: Banjo

In the United States, where 77% of K-12 teachers are women and 82% of female teachers are white, Banjo identified with the majority (Loewus, 2017). Banjo described herself as someone who grew up with scant confidence in her ability to be successful as a student and eventual working professional. Although she described her interest in subjects such as social studies and science as a young student, as well as her interest in professional fields such as forensic psychology or pathology, she always held the belief that she would never be “smart enough” to pursue such careers. Furthermore, she explained that throughout her childhood, adolescence, and years as a college student, her parents validated her feelings of self-doubt, believing that “realistically there aren’t many things [Banjo] can do.” As a result, Banjo pursued a career in early childhood teaching because she observed that other young women were doing it, and therefore believed it would be “easy enough for someone like her” who, from her and her parents’ perspectives, was “not capable of doing much else.” In Banjo’s words, she explained, “Unfortunately, I think my decision to be a teacher was just a huge intellectual thing for me and how I felt about myself intelligence-wise. I wanted to feel confident that I knew what I was talking about, and I knew I could do the Kindergarten math.”

During her four and a half years as a teacher candidate and early childhood teacher, Banjo worked in five different schools across multiple early childhood grade levels. The first half of her student teaching experience was conducted at an urban elementary school near St. Paul, Minnesota, where she taught in a Grade 1 classroom. After working as a student employee in her university’s International Studies Office and developing an interest in teaching abroad, Banjo opted to complete the second half of her student teaching experience at an affluent private school in Ecuador where she taught Grade 3. During her first year as an in-service teacher, Banjo held dual roles as a special education paraprofessional and substitute for a first-grade teacher who was on maternity leave. At the end of her first year, Banjo transitioned from a public school to a small, under-resourced charter school located outside Minneapolis, where she taught in a blended Kindergarten and Grade 1 classroom for two years. By her fourth year, Banjo had returned to working as a substitute with students in K-12 at multiple school districts within the Twin Cities. At the end of her fourth and final year, Banjo began working at a restaurant in Minneapolis and, within the same year, began participating in our virtual, audio-recorded interview sequence.

Data Collection

Beginning in summer 2019, just two months after Banjo completed her fourth year as an early childhood teacher, the researcher audio-recorded the first of four semi-structured, 2-h Zoom interviews. The virtual, one-on-one Zoom setting ensured privacy and confidentiality between the researcher and participant. Three additional interviews were conducted at three-month intervals throughout the 2019–2020 academic year, totaling in one year of data collection. Each interview began and ended with a review of Banjo’s rights and responsibilities as a study participant, based on the approved IRB consent form.

During each interview, the researcher and Banjo discussed her experiences and perceptions as a K-12 student, PST, teacher candidate, and in-service early childhood practitioner. The researcher developed interview questions (see Supplementary Appendix A) to capture four stages of Banjo’s story: (1) Getting to Know the Participant and Decision to Teach; (2) Early Reflections; (3) Experiences as a Teacher; (4) Decision to Leave and Final Reflections. To guide the interviews, Banjo answered questions such as, “What experiences or factors influenced your decision to pursue a career in early childhood teaching?,” “Tell me about a time when you realized you did not want to remain in the teaching profession,” “Tell me about a time when your expectations of being a teacher collided with your reality of being a teacher,” and “What knowledge and/or experiences do you think could have improved your teaching practice and, with that, confidence in your teacher identity?” Following each interview, the researcher transcribed the audio-recordings in preparation for data analysis.

Data Analysis

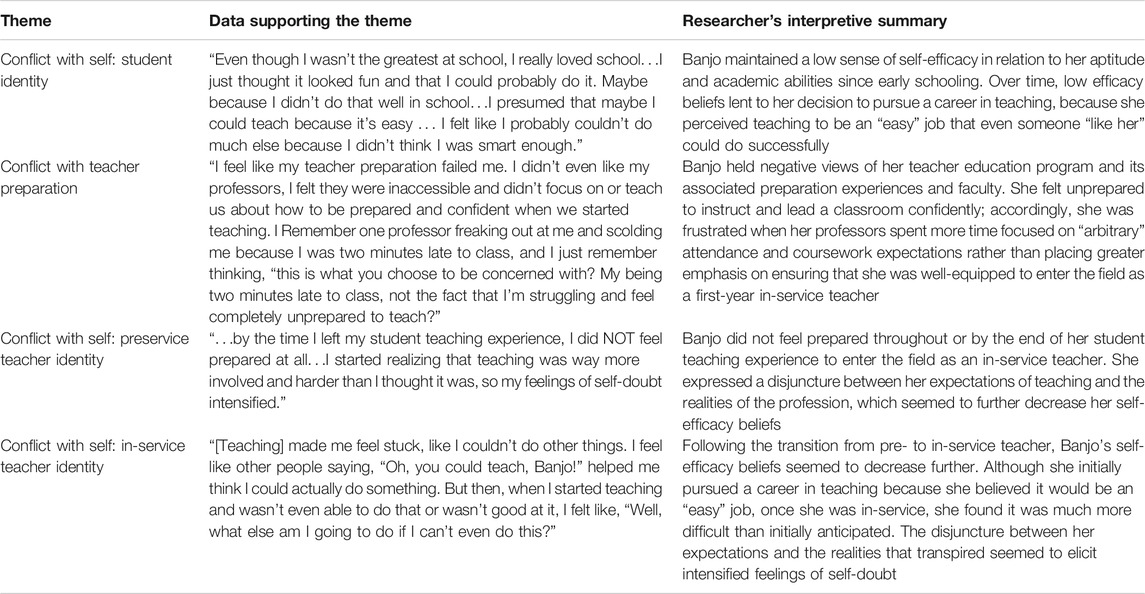

The initial analysis of Banjo’s stories began with a complete reading of all four interview transcripts. During the initial reading and first-cycle coding process, the researcher employed both descriptive coding and in vivo coding by taking notes in the margins and creating a data table (see Table 1). While descriptive coding “summarizes the topic of a text excerpt” (Saldaña, 2016, p. 4), in vivo coding “utilizes the participant’s own language as a symbol system for qualitative data analysis” (Saldaña and Omasta, 2018, p. 121). The next part of the analysis involved rereading all four interview transcripts to identify new and clearly specified examples tied to the aforementioned codes. As the researcher began to identify commonalities during the second read-through, the researcher used pattern coding for the second-cycle coding process and grouped summaries into categories such as “self-doubt,” “teacher-efficacy perceptions,” and “teacher preparation,” which the researcher also noted in the transcript margins and data table. Through the pattern coding process, several broader categorizations stemming from self-doubt, teacher-efficacy perceptions, and teacher preparation emerged and became the final four themes of the study: (1) Conflict with Self: Student Identity; (2) Conflict with Teacher Preparation; (3) Conflict with Self: Preservice Teacher Identity; (4) Conflict with Self: In-service Teacher Identity.

Trustworthiness and Ethical Considerations

The narrative researcher’s objective was to listen, learn, and report her interpretation of the facts presented by Banjo, as well as articulate her interpretations from a persuasive point of view (Riessman, 2008; Loh, 2013). To ensure quality, validity, and reliability, the researcher reviewed her data interpretations with Banjo before and after each interview, as well as during each storytelling stage of manuscript development to ensure authentic co-construction of the narrative. Upon completion of the manuscript, the researcher met with Banjo to discuss: (1) What were your general impressions of the narrative? (2) Based on our co-construction of the narrative before and after each interview, in what ways does the final narrative accurately portray your stories? Which aspects of the narrative, if any, do not accurately reflect the co-constructed reality we discussed? (3) Now that the narrative is in its final form, is there anything in the write-up that you would like to reconsider or represent differently before it is shared for publication? Since the meanings unearthed through participants’ historical truths provide “the best evidence available to researchers about the realm of people’s experience,” as the researcher and Banjo collectively constructed her reality, it was imperative to understand Banjo’s mental and emotional responses to the retelling of her experiences (Polkinghorne, 2007, p. 479).

Findings

In the context of this inquiry, findings are based on Banjo’s reflective account of her experiences after deciding to leave the teaching profession. While the storying of Banjo’s lived experiences offered the researcher valuable insight into how Banjo made sense of her decision to leave, it is critical to note that Banjo’s perspectives and interpretations shifted as she storied and re-storied her decision (and related factors) in the year following her departure. For example, although Banjo initially viewed her decision to enter the teaching profession as based on her perception of teaching as an “easy” career, as she continuously reflected, her recognition of the environmental influence (e.g., interactions with parents, observations of teachers) on her decision began to emerge. Collectively, the following emergent themes reflect authentic interpretations drawn by the researcher and verified by Banjo.

Conflict with Self: Student Identity

Banjo’s transition from a K-8 private Catholic school to a public high school was, in her words, “the world’s biggest wake up call.” Banjo expressed that the transition was a huge culture shock, as she had been used to attending a school where sex education was not taught, and chapters about evolution were skipped or cut out of science textbooks. Banjo’s first exposure to sex education and evolution at the public high school caused her to question why the curriculum looked so different from what she had learned at the private K-8 school. Despite the fact that students traveled from long distances to attend the private school, Banjo stated that all of the students looked like her and shared the Catholic beliefs she had learned and lived by throughout her K-8 years of schooling. At the public high school, however, “I was at a super diverse high school where evolution was being taught and kids were doing drugs, having sex, and getting pregnant.” For Banjo, the most eye-opening aspect of her transition was that she had been living next door to the public-school students her entire life, which she did not recognize until she was situated in a new, unfamiliar, and intimidating context.

Reflecting on her experiences as a student, Banjo discussed how when she was growing up, her family did not talk about career options: “My parents wanted us to do well in school and go to college, but we never had conversations about what we would do after college.” As a result, Banjo believed that her teachers greatly influenced her formative years, because she recalled enjoying their classes, personalities, and overall presence: “I remember thinking that my teachers always seemed to enjoy their jobs. I actually remember trying to “play school” with my brothers, where I would be the teacher and they would be my students.” As the researcher gained a better understanding of Banjo’s early experiences as a student, she became increasingly interested in the specific factors that led to Banjo’s decision to pursue a career in teaching. Banjo’s response suggested a potentially longstanding conflict with her student identity:

“I guess I became a teacher because I saw other women doing it and felt that maybe it was something I could do, too. I presumed that maybe I could teach because it’s easy, [and] I felt like I probably couldn’t do much else because I didn’t think I was smart enough. Other careers just seemed intimidating.”

Conflict with Teacher Preparation

Following through with her idea to pursue a career in teaching, Banjo enrolled in a teacher preparation program at a private, Roman Catholic university near Minneapolis. Curious to learn more about her holistic view of her teacher preparation program, the researcher asked Banjo to describe her experiences:

“There were so many things I feel I didn’t learn in college. I Understand how a lot of the stuff they didn’t teach us is stuff you’re supposed to figure out on the job—and I kind of get that—but it also made me extremely hesitant to do what I probably should have been doing while in the classroom. I just felt really unprepared. I feel like my teacher preparation failed me.”

When the researcher asked Banjo to reflect on specific experiences that contributed to her view of her teacher preparation and development of teacher identity, Banjo described a diversity course that required a research project on Hmong culture. When prompted to elaborate on the project’s relationship to her view of teacher preparation, she stated:

“We weren’t reading books about here’s what you can do when you have non-native English speakers in your class. My preparation, in my mind, was supposed to be about here’s a bunch for methods [sic] for how to teach diverse students a bunch of different early childhood subjects, but I really didn’t get much out of it.”

As another example, although Banjo appreciated that her teacher preparation program placed her in a classroom during one of her earlier semesters to observe experienced teachers, her observation of the same 30-min class once a week for five consecutive weeks resulted in her observation of identical, repeatedly taught spelling lessons. She reflected, “I think more variety would have helped. Being able to see more of what goes on during the day, spend one-on-one time with the lead teacher, and actually practice teaching would have been more useful.” Furthermore, she described a partner project where she and a fellow classmate co-taught in front of their peers:

“I didn’t get much out of it because any bad habits she had, I also had. I felt like throughout the entire program, we were all just thrown into things. We weren’t prepared for anything we participated in. Having examples of experienced teachers to follow would have been helpful to me.”

Throughout her sharing of experiences, Banjo frequently referenced classroom management as an underrepresented area of her teacher preparation. She explained that there were no course offerings related to classroom management, which was detrimental to her development and practice: “[Classroom management] is basically what your entire day is about when you’re teaching early childhood.” Banjo described having to regularly remind students to sit in their assigned seats, usher them to and from the restroom to wash their hands between activities, and teach them to use quiet voices in certain places and at specific times around the school. Yet, she repeated, “I didn’t learn anything about how to manage those behaviors during preparation.” Since classroom management seemed to be a major source of frustration for Banjo, the researcher asked her what would have been beneficial during her teacher preparation. Banjo replied, “I wish there were actual classes called “classroom Management.” Classes that taught you everything you’ll need to know about classroom management. I feel like we did one lesson on it, and I came out with a pamphlet. An actual class every year would have really benefited my preparation.”

Conflict with Self: Preservice Teacher Identity

As Banjo continued telling her story, the researcher asked her to recall details beyond her coursework and share some of her other experiences as a PST, or teacher candidate, and describe the student teaching semester. Banjo discussed how she completed the first half of her student teaching in Minnesota and the second half in Ecuador: “By the time I felt comfortable starting to manage the room on my own, I had to completely switch classrooms and contexts.” When the researcher probed about her initial Minnesota-based experience, Banjo described the negative influence that her mentor teacher had on her preservice experience. Rather than offer constructive and encouraging feedback, which Banjo desired, her mentor teacher frequently asked her why she wanted to be a teacher in the current political and economic climate. Banjo went on to compare her discouraging relationship with her mentor and developing teacher identity to a delicate object:

“My relationship with teaching is like a china teacup. You might scuff it up, but you can always polish it to get it clean again. But if you get a chip in the teacup, that’s permanent, and I guess hearing all that negativity was the first chip in my teacup.”

Banjo continued to describe her reasons for switching her teaching placement to Ecuador as well as the differences between her experiences. She recalled thinking that student teaching abroad and “having that global experience” would help her on the job market. However, when she ended up working at a high-income private school in Ecuador with students she described as “snobby and in complete control,” she reflected on the difficult transition from “having a no-nonsense, disciplinarian-type mentor teacher in Minnesota to a mentor teacher who let the kids walk all over her in Ecuador.” Furthermore, she explained that in her transition from student teaching in Minnesota to Ecuador, she had to adjust to a new country where norms and guidelines for teaching were drastically different. As a result, she “did not feel prepared at all.” Nonetheless, despite the Stark contrast between her student teaching placements in Minnesota and Ecuador, she realized that “teaching was way more involved and harder than [she] thought it was,” and thus her feelings of self-doubt intensified

Conflict with Self: In-Service Teacher Identity

When asked to describe her experience as an in-service teacher, Banjo fondly remembered several instances where she felt prepared to lead a classroom: “The only positive memories I have of feeling good about teaching are the days where I felt like I knew how to deliver a lesson.” for example, Banjo explained that once while she was subbing, another teacher in the department asked her to observe him teaching a new math lesson during a morning class. Banjo took notes of what he said and how he presented the formulas to students, and she eventually modeled his strategies when she taught the afternoon class herself. When the researcher asked her how it felt to feel prepared to teach, she replied, “My teaching was so much smoother when I felt confident and prepared like that. It felt good.” Banjo continued to explain her proclivity for observational learning:

“I learn better by watching other people do things. One time, I was subbing for ateacher who was gone, and he told me to watch another teacher teach the same lesson earlier in the day. So, I observed the other teacher, followed his model, and the kids told me I was the best sub ever. I wish I had more opportunities to observe teachers modeling lessons before I started teaching.”

On a different note, Banjo expressed her frustration with in-service teaching challenges such as inadequate—or nonexistent—opportunities for feedback and issues with attending to students’ social and emotional needs. Banjo explained that while she was supposed to be formally evaluated by her principal at least once per year, she was never observed and never received any feedback: “We all just gave up. Everything was too disorganized, and our principal couldn’t keep up with observations. Feedback was nonexistent.” In order to address some of the organizational issues, during Banjo’s second year of teaching, her school hired a reading intervention specialist. Although Banjo was hopeful that the new hire would alleviate some of her day-to-day management stressors, the usual complications persisted:

“I don’t really know what they were doing with that [reading specialist] position, because the specialist never actually worked with my kids. They were never available, so I didn’t feel like they were effective. Everything was on me, and when there were other issues at the school like handling the social and emotional needs of students, it was on me to take care of the students. I didn’t feel prepared to do that because I didn’t receive any training for that at the school or during college, but that would have been really helpful.”

Evidenced by the literature and further supported by Banjo’s refrains, there seems to be a disconnect between the expectations established during teacher preparation and the development of teacher identity throughout the practicum experience, which “fails to adequately prepare pre-service teachers for the realities of teaching and fails to provide a realistic understanding of what it means to be a teacher” (Karalis Noel, 2020a; Harlow and Cobb, 2014, p. 71).

Discussion and Limitations

Unrealistic expectations of teaching may result in discrepancies between early-career teachers’ expectations of teaching vs. the realities of school culture, which may negatively impact their early-career teacher identities and, in turn, increase the likelihood of turnover (Chong et al., 2011; Haggarty and Postlethwaite, 2012; Karalis Noel, 2020a). Associated with turnover, researchers have begun to explore emerging teachers’ emotions as an integral aspect of their identify formation (see Beijaard et al., 2004; Beauchamp and Thomas, 2009), yet the examination of how emerging teachers “construct their identities from their emotional experience during preservice education, including the teaching practicum, remains underexplored” (Yuan and Lee, 2016, p. 820). As such, researching the events and influential factors that led to an early-career teacher’s construction of identity and her ultimate decision to leave the teaching profession became the critical infrastructure of this study to initiate and sustain progressive shifts in teacher preparation.

Underpinned by symbolic interactionism, Day and Kington (2008) discuss identity as a composite consisting of interactions between personal, professional, and situational factors. In Banjo’s case, stemming from her years of schooling, her personal dimension of identity was linked to negative views of herself and her abilities. Because Banjo’s beliefs about not being able to be successful in “harder” fields were reinforced by family and friends, her confidence and perceptions of effectiveness were negatively affected before she even began her teacher preparation program. When feedback comes from family and friends and negatively impacts the receiving individual’s sense of identity, it often becomes a source of tension and provokes persistent instabilities (Day and Kington, 2008).

Banjo’s professional and situational dimensions of identity were also negatively influenced by her conception of what constitutes a “good” or effective teacher and how she viewed her own alignment with those qualities within and across teaching contexts. In comparing her pedagogy and management skills to teachers whom she observed and taught alongside, Banjo believed that effective teachers were those who knew how to manage their classrooms, inspire students through organized, engaged lessons, and came to school with excitement and enthusiasm about teaching every day. Supported by research which consistently suggests that sustaining a positive sense of effectiveness is important to maintaining motivation, self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and a commitment to teaching (Day et al., 2006; Flores, 2002; Nias, 1989; Kelchtermans, 1993; Karalis Noel, 2020a), Banjo’s perception of not aligning with effective teacher traits elicited feelings of incompetence, self-doubt, and ineffectiveness. Moreover, because Banjo frequently received negative reinforcement about the challenges associated with the teaching profession from her mentor teacher—which were coupled with nonexistent opportunities to receive positive and constructive feedback from other supervisors—Banjo’s decision to leave the field based on adverse experiences that perpetuated feelings of inadequacy, emotional vulnerability, and an impaired sense of agency was predictable (Rushton, 2004; Day and Kington, 2008; Yuan and Lee, 2016). Overall, throughout the interviews, it was evident that Banjo did not express ill will toward students or the field of education writ large. Rather, she expressed disappointment with herself and disillusionment with the mentor teachers and teacher education faculty whom she entrusted to prepare her for challenging and emotional labor-inducing classroom contexts (Yuan and Lee, 2016).

Although external factors such as negative experiences with mentor teachers and preservice preparation impacted Banjo’s identity development, it is important to consider the role of Banjo’s sense of agency; that is, her belief in having the internal power to monitor her own thoughts, feelings, and actions (Lasky, 2005; Sexton, 2008; Yuan and Lee, 2016). Past research (see Kelchtermans, 2005; Lasky, 2005; Yuan and Lee, 2016) reveals associations between teachers’ professional identities and their sense of agency, which is determined by a teacher’s ability to reflect on their professional actions and achieved through their resistance to contextual challenges (Yuan and Lee, 2016). Although early-career teachers like Banjo might confront emotionally draining challenges such as a lack of collegial support (Yuan and Lee, 2016), “by exercising their professional agency, they can actively draw upon different arrays of social positioning, experiences, and resources and enact identities that align with their own beliefs and values” (Sexton, 2008 qtd. in; Yuan and Lee, 2016, p. 822). Since Banjo’s story focused on external rather than internal factors of influence on her identity dimensions and ultimate decision to depart the teaching profession, this study would benefit from extended research to examine Banjo’s responsibility as an emerging teacher. For instance, had Banjo sought out supplemental opportunities to learn about and develop classroom management techniques, would she have felt as unprepared and incapable of employing such strategies? Or, rather than leaving the country for a global experience at a high-income private school in Ecuador, would student teaching in an urban public school or Indigenous community have enhanced Banjo’s culturally responsive pedagogy in preparation for the diverse classroom contexts in which she would be teaching post-graduation? Although research suggests that transition shock based on discrepancies between PSTs’ expectations for teaching vs. the realities of their early-career experiences is common (Chong et al., 2011; Danielewicz, 2001; Day and Kington, 2008; Smagorinsky et al., 2004; Steffy et al., 2000; Karalis Noel, 2020a), stories like Banjo’s emphasize that while teacher education programs have a responsibility to prepare teachers, the role of agency in emerging teachers’ development must be cooperatively explored.

In the end, Banjo’s story reminds us of age-old fallacies such as “Those who can’t do, teach” or “Teaching is an easy career option” and how they continue to pervade the young minds of PSTs and impact their early-career experiences. After completing a traditional undergraduate teacher preparation program and teaching in an urban context for four years, Banjo quickly decided to leave the profession and pursue vocational opportunities unrelated to education. If Banjo’s experiences had been different, i.e. had her family been more supportive of her ability to be academically and professionally successful, had her teacher preparation offered meaningful, immersive opportunities to observe and practice quality teaching, or had her mentor teacher and supervisors (e.g. principals) provided constructive and encouraging feedback, would Banjo have decided to leave the field as quickly as she did? Furthermore, her decision to leave calls to question: (1) What could Banjo have done to supplement aspects of her preparation that she felt were lacking? and (2) Understanding that PSTs may not know as much as teacher educators and mentor teachers about what they (PSTs) need to be prepared, what could teacher educators, mentor teachers, and other experienced professionals have done to prevent Banjo’s departure and the future exodus of early-career teachers who encounter shared experiences?

As with any study focused on one participant, there are limitations to unearthing generalizable information. However, further research could be conducted to gain a better sense of the personal, professional, social, and environmental factors that lead to high turnover of early childhood teachers. Questions to inform future studies may include, but are not limited to: What images of teaching and themselves as teachers have emerging practitioners developed as a result of their schooling experiences and individual concepts of self? How has/does feedback or expectations from family and friends outside of school influence emerging teachers’ identities? What are PSTs’ expectations of teaching vs. the realities of teaching that often transpire, and what can teacher educators, supervisors, and mentor teachers do to attend to these discrepancies during emerging teachers’ early-career development?

Banjo’s story reminds us that there are opportunities for progressive shifts in the way society views and talks about teaching as an “easy” career option, as well as the ways teacher educators, supervisors, and mentors remind themselves of how much influence they and their surrounding environment have on developing young teachers. While future aspiring teachers might learn from Banjo’s experiences to advocate for their own development of confident and efficacious teacher identities, teacher preparation programs and placement schools might increase their awareness of the coursework, practicum, and induction year supports that are essential to providing emerging teachers with receptive, responsive, and sustaining preparation.

Conclusion and Implications

As emerging teachers’ identities continue to develop throughout their preservice, student teaching, and initial in-service experiences, it is essential for teacher educators, supervisors, and mentors to recognize and attend to early-career teachers’ misconceptions about the profession and their ability to be successful. Furthermore, in order for teacher preparation and early-career mentorship to be receptive, responsive, and sustaining, it is imperative for teacher educators and mentors to learn about beginning teachers’ areas of concern and collaborate to initiate productive shifts in practice and identity development.

Adapted from Yuan and Lee (2016) recommendation to integrate personal and professional identity competencies in teacher education, programs could design and implement opportunities for PSTs to form an awareness and interrogate perceptions of “who they were/are” and “who they wish to be” as teachers (Chang-Kredl and Kingsley, 2014). For instance, if PSTs express concerns regarding their ability to implement culturally responsive pedagogy or articulate that a course on classroom management and ample opportunities to observe experienced teachers would facilitate their learning and, in turn, increase their confidence and self-efficacy, then teacher educators and mentors could implement these requests throughout teacher preparation and the induction year (Chong et al., 2011). Such experiences would offer PSTs opportunities to identify their pedagogical areas of strength and development, which could bridge the gap between PSTs expectations of themselves as teachers vs. the realities of their instructional competencies during the early in-service years. Given the extant literature which suggests conflicting preservice expectations and in-service realities are linked to teacher attrition (Borman and Dowling, 2008; Chong et al., 2011; Gratch, 2001; Guarino et al., 2006; Ingersoll, et al., 2014; Kelchtermans and Ballet, 2002), a proactive approach to reducing early-career teachers’ “transition shock” could lend itself to increased retention of novice practitioners (Corcoran, 1981, p. 19).

While some scholars like Yuan and Lee (2016) encourage teacher educators to model emotional practices by showing PSTs how to turn emotions into useful resources for teaching and learning, others suggest the use of emotional diaries (Zembylas, 2003), role play (White, 2009), or case studies (Gorski and Pothini, 2014, 2018; Karalis Noel, 2020a) to create “opportunities [for PSTs] to confront and reflect on their own or others’ emotional experiences, anticipate classroom situations with which they may struggle, and discuss possible strategies to cope with the emotional challenges” (Schutz and Zembylas, 2009 qtd. in; Yuan and Lee, 2016). Through various collaborative and reflective experiences, PSTs could reconcile competing notions of who they are vs. who they wish to be as teachers (Chang-Kredl and Kingsley, 2014), as well as position themselves for success as introspective early-career practitioners who are prepared to manage the inevitable challenges they will encounter during the induction year. Such authentic engagement and preparation could lead to PSTs’ increased confidence in their ability to problem solve common early-career conflicts and, consequently, increase the likelihood of their retention in the field (Karalis Noel, 2020a). In closing, by creating inquiry-based reflection opportunities for preservice and early-career teachers, teacher educators, supervisors, and mentors can better understand and attend to the needs of emerging teachers, which may contribute to the development of confident, efficacious teachers who remain in the profession long-term.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University at Buffalo Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

TKN, the sole and corresponding author on this manuscript, conceived and designed the study, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.586212/full#supplementary-material.

References

Achinstein, B. (2006). New teacher and mentor political literacy: reading, navigating and transforming induction contexts. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 12, 123–138. doi:10.1080/13450600500467290

Beauchamp, C., and Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: an overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Cambridge J. Educ. 39, 175–189. doi:10.1080/03057640902902252

Beer, J., and Beer, J. (1992). Burnout and stress, depression and self-esteem of teachers. Psychol. Rep. 71 (3_Suppl. l), 1331–1336. doi:10.2466/pr0.1992.71.3f.1331 |

Beijaard, D., Meijer, P. C., and Verloop, N. (2004). Reconsidering research on teachers' professional identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 20, 107–128. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2003.07.001

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: perspective and method. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Borman, G. D., and Dowling, N. M. (2008). Teacher attrition and retention: a meta-analytic and narrative review of the research. Rev. Educ. Res. 78, 367–409. doi:10.3102/0034654308321455

Bruner, J. (1987). “Life as narrative,” in Search of pedagogy. The selected works of Jerome Bruner. Editor Bruner, J. (New York: Routledge), 129–140.

Bruner, J. (1991). “The narrative construal of reality,” in Te culture of education. Editor J. Bruner (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), 139–149.

Bucholtz, M., and Hall, K. (2005). Identity and interaction: a socio-cultural linguistic approach. Discourse Stud. 74, 585–614. doi:10.4324/9781003106807-25

Chang-Kredl, S., and Kingsley, S. (2014). Identity expectations in early childhood teacher education: pre-service teachers’ memories of prior experiences and reasons for entry into the profession. Teach. Teach. Educ. 43, 27–36. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2014.05.005

Chong, S., Low, E., and Goh, K. (2011). Emerging professional teacher identity of preservice teachers. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 36 (8), 50–64. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.06.006

Clandinin, D. J., and Connelly, F. M. (1998). Stories to live by: understandings of school reform. Curriculum Inq. 28 (2), 149–164.

Clandinin, D. J., and Connelly, F. M. (1996). Teachers’ professional knowledge landscapes: teacher stories-stories of teachers-school stories-stories of school. Educ. Res. 25 (5), 2–14.

Clandinin, D. J. (2007). Handbook of narrative inquiry: mapping a methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Clandinin, D. J., Downey, C. A., and Huber, J. (2009). Attending to changing landscapes: shaping the interwoven identities of teachers and teacher educators. Asia-Pacific J. Teach. Educ. 37, 141–154.

Clandinin, D. J., Huber, J., Huber, M., Murphy, S., Murray Orr, A., Pearce, M., et al. (2006). Composing diverse identities: narrative inquiries into the interwoven lives of children and teachers. New York: Routledge.

Clandinin, D. J., Long, J., Schaefer, L., Downey, C. A., Steeves, P., Pinnegar, E., et al. (2015). Early career teacher attrition: intentions of teachers beginning. Teach. Educ. 26 (1), 1–16. doi:10.1080/10476210.2014.996746

Connelly, F. M., and Clandinin, D. J. (1990). Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educ. Res. 19 (5), 2–14.

Corcoran, E. (1981). Transition shock: the beginning teacher’s paradox. J. Teach. Educ. 32 (3), 19–23. doi:10.1177/002248718103200304

Danielewicz, J. (2001). Teaching selves: identity, pedagogy, and teacher education. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Darling-Hammond, L. (1999). Solving the dilemmas of teacher supply, demand, and standards: how we can ensure a competent, caring, and qualified teacher for every child. New York, NY: National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future.

Day, C., and Kington, A. (2008). Identity, well-being and effectiveness: the emotional contexts of teaching. Pedagogy, Cult. Soc. 16 (1), 7–23. doi:10.1080/14681360701877743

Day, C., Kington, A., Stobart, G., and Sammons, P. (2006). The personal and professional selves of teachers: stable and unstable identities. Br. Educ. Res. J. 32 (4), 601–616. doi:10.1080/01411920600775316

Flores, M. A. (2002). Learning, development and change in the early years of teaching: a two-year empirical study. Ph.D. dissertation. Nottingham, England: University of Nottingham.

Flores, M. A., and Day, M. A. (2006). Contexts which shape and reshape new teachers' identities: a multi-perspective study. Teach. Teach. Educ. 22, 219–232.

F. M. Connelly, and D. J. Clandinin Shaping a professional identity: stories of educational practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

Gill, P. B. (2001). Narrative inquiry: designing the processes, pathways and patterns of change. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 18 (4), 335–344. doi:10.1002/sres.428

Gorski, P., and Pothini, S. G. (2014). Case studies on diversity and social justice education. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gorski, P., and Pothini, S. G. (2018). Case studies on diversity and social justice education. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gratch, A. (2001). The culture of teaching and beginning teacher development. Teach. Educ. Q. 28 (4), 121–136. doi:10.4324/9780203209332_chapter_1

Guarino, C., Santibanez, L., and Daley, G. (2006). Teacher recruitment and retention: a review of the recent empirical literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 76 (1), 173–208. doi:10.3102/00346543076002173

Haggarty, L., and Postlethwaite, K. (2012). An exploration of changes in thinking in the transition from student teacher to newly qualified teacher. Res. Pap. Educ. 27 (2), 241–262. doi:10.1080/02671520903281609

Harlow, A., and Cobb, D. (2014). Planting the seed of teacher identity: nurturing early growth through a collaborative learning community. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 39 (7). doi:10.14221/ajte.2014v39n7.8

Hester, O. R., Bridges, S. A., and Rollins, L. H. (2020). Overworked and underappreciated': special education teachers describe stress and attrition. Teach. Dev. 3, 348–365. doi:10.1080/13664530.2020.1767189

Hong, J., and Cross Francis, D. (2020). Unpacking complex phenomena through qualitative inquiry: the case of teacher identity research. Educ. Psychol. 55 (4), 208–219. doi:10.1080/00461520.2020.1783265

Ingersoll, R., Merrill, L., and May, H. (2014). What are the effects of teacher education and preparation on beginning teacher attrition? CPRE research report #RR-82. Philadelphia: Consortium for Policy Research in Education.

Joyce, M. (2015). Using narrative in nursing research. Nurs. Stand. 38, 36–41. doi:10.1002/9781444316513.ch3 |

Kagan, D. M. (1992). Professional growth among preservice and beginning teachers. Rev. Educ. Res. 62 (2), 129–169. doi:10.3102/00346543062002129

Karalis Noel, T. (2000a). Narrative inquiry: examining the self-efficacy of content area teacher candidates. J. Teach. Educ. Educat. 9 (1), 23–60.

Karalis Noel, T. (2020b). “We can theorize in a classroom all day, but nothing beats experiencing the real thing: experiential learning in preservice preparation,” in Ideating pedagogy in troubled times: approaches to identity, theory, teaching, and research. Editors S. L. Raya, S. Masta, S. T. Cook, and J. Burdick (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing), 117–125.

Kelchtermans, G., and Ballet, K. (2002). The micropolitics of teacher induction. A narrative-biographical study on teacher socialisation. Teach. Teach. Educ. 18, 105–120. doi:10.1016/s0742-051x(01)00053-1

Kelchtermans, G. (1993). Getting the story, understanding the lives: from career stories to teachers’ professional development. Teach. Teach. Educ. 9 (5/6), 443–456.

Kelchtermans, G. (2005). Teachers’ emotions in educational reforms: self-understanding, vulnerable commitment and micropolitical literacy. Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 995–1006. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.009

Kelchtermans, G. (2017). ‘Should I stay or should I go?’: unpacking teacher attrition/retention as an educational issue. Teach. Teach. 23 (8), 961–977. doi:10.1080/13540602.2017.1379793

Kersaint, G., Lewis, J., Potter, R., and Meisels, G. (2007). Why teachers leave: factors that influence retention and resignation. Teach. Teach. Educ. 23, 775–794. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.12.004

Korthagen, F. (2004). In search of the essence of a good teacher: towards a more holistic approach in teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 20, 77–97. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2003.10.002

Kushman, J. W. (1992). The organizational dynamics of teacher workplace commitment: a study of urban elementary and middle schools. Educ. Adm. Q. 28 (1), 5–42. doi:10.1177/0013161X92028001002

Lasky, S. (2005). A sociocultural approach to understanding teacher identity, agency and professional vulnerability in a context of secondary school reform. Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 899–916. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.003

Lindqvist, P., Nordänger, U. K., and Carlsson, R. (2014). Teacher attrition the first five years—a multifaceted image. Teach. Teach. Educ. 40, 94–103. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2014.02.005

Loewus, L. (2017). The nation’s teaching force is still mostly white and female. Education Week. Retrieved from https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2017/08/15/the-nations-teaching-force-is-still-mostly.html.

Loh, J. (2013). Inquiry into issues of trustworthiness and quality in narrative studies: a perspective. Qual. Rep. 18 (33), 1–15. doi:10.1007/978-1-137-02155-7_3

Lovett, S., and Davey, R. (2009). Being a secondary English teacher in New Zealand: complex realities in the first 18 months. Prof. Develop. Educ. 35, 547–566.

Mansfield, C., Beltman, S., and Price, A. (2014). ‘I’m coming back again!’ the resilience process of early career teachers. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 20, 547–567. doi:10.1080/13540602.2014.937958

McNally, J., Blake, A., and Reid, A. (2009). The informal learning of new teachers in school. J. Workplace Learn. 21, 322–333.

National Association for the Education of Young Children (2004). NAEYC advocacy Toolkit. Retrieved from www.naeyc.org/files/naeyc/file/policy/toolkit.pdf

Newberry, M., and Allsop, Y. (2017). Teacher attrition in the USA: the relational elements in a Utah case study. Teach. Teach. 23 (8), 863–880. doi:10.1080/13540602.2017.1358705

Nichols, S. L., Schutz, P. A., Rodgers, K., and Bilica, K. (2017). Early career teachers’ emotion and emerging teacher identities. Teach. Teach. 23 (4), 406–421. doi:10.1080/13540602.2016.1211099

Perryman, J., and Calvert, G. (2020). What motivates people to teach, and why do they leave? Accountability, performativity and teacher retention. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 68 (1), 3–23. doi:10.1080/00071005.2019.1589417

Polkinghorne, D. E. (2007). Validity issues in narrative research. Qual. Inq. 13 (4), 471–486. doi:10.1177/1077800406297670

Ramos, G., and Hughes, T. R. (2020). Could more holistic policy addressing classroom discipline help mitigate teacher attrition?. eJournal Educ. Pol. 21 (1) doi:10.37803/ejepS2002

Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Roberts, A. M., Gallagher, K., Sarver, S., and Daro, A. M. (2018). Early childhood teacher turnover in Nebraska. Omaha: University of Nebraska, Buffett Early Childhood InstituteRetrieved from https://buffettinstitute.nebraska.edu/-/media/beci/docs/early-childhood-teacher-turnover-in-nebraska-new.pdf?la=en.

Rushton, S. P. (2004). Using narrative inquiry to understand a student-teacher’s practical knowledge while teaching in an inner-city school. Urban Rev. 36 (1), 61–79. doi:10.1023/b:urre.0000042736.78181.61

Schaefer, L., Downey, C. A., and Clandinin, D. J. (2014). Shifting from stories to live by to stories to leave by: early career teacher attrition. Teach. Educ. Q. 41 (1), 9–27. doi:10.4324/9780429273896-8

Schaefer, L. M. (2013). Beginning teacher attrition: a question of identity making and identity shifting. Teach. Teach. 19 (3), 260–274. doi:10.1080/13540602.2012.754159

Schutz, P. A., and Zembylas, M. (2009). Advances in teacher emotion research: the impact on teachers’ lives. New York, NY: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0564-2

Sexton, D. M. (2008). Student teachers negotiating identity, role, and agency. Teach. Educ. Q. 35, 73–88. doi:10.31901/24566322.2016/13.02.05

Shapiro, S. (2010). Revisiting the teachers’ lounge: reflections on emotional experience and teacher identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 616–621. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.09.009

Shen, J. (1997). Teacher retention and attrition in public schools: evidence from SASS91. J. Educ. Res. 91 (2), 81–88.

Smagorinsky, P., Gibson, N., Bickmore, S., Moore, C., and Cook, L. (2004). Praxis shock: making the transition from a student-centered university program to the corporate climate of schools. English Educ. 36 (3), 214–245. doi:10.1007/978-94-6300-672-9_14

Steffy, B., Wolfe, M., Pasch, S., and Enz, B. (2000). Life cycle of the career teacher. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press and Kappa Delta Pi.

Sudtho, J., Singhasiri, W., and Jimarkon, P. (2015). Using symbolic interactionism to investigate teachers’ professional identity. Pertanika J. Social Sci. Humanities 23 (4), 1153–1166. doi:10.4135/9781412979306.n259

Ulvik, M., Smith, K., and Helleve, I. (2009). Novice in secondary school—the coin has two sides. Teach. Teach. Educ. 25, 835–842. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.01.003

White, K. (2009). Using preservice teacher emotion to encourage critical engagement with diversity. Stud. Teach. Educ. 5, 5–20. doi:10.1080/17425960902830369

Witherell, C., and Noddings, N. (1991). Stories lives tell: narrative and dialogue in education. New York: Teachers College Press.

Yuan, R., and Lee, I. (2016). “I need to be strong and competent”: a narrative inquiry of a student−teacher’s emotions and identities in teaching practicum. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 22 (7), 819–841. doi:10.1080/13540602.2016.1185819

Zeegers, M., and Barron, D. (2015). Milestone moments in getting your PhD in qualitative research. Chandos Publishing.

Zembylas, M. (2003). Emotions and teacher identity: a poststructural perspective. Teach. Teach. 9, 213–238. doi:10.4324/9780429470950-3

Keywords: teacher education, teacher identity, symbolic interaction theory, preservice teacher, in-service teacher, narrative inquiry, student teacher, teacher attrition

Citation: Karalis Noel T (2021) Identity Tensions: Understanding a Previous Practitioner’s Decision to Pursue and Depart the Teaching Profession. Front. Educ. 6:586212. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.586212

Received: 22 July 2020; Accepted: 26 January 2021;

Published: 11 March 2021.

Edited by:

Heidi L. Hallman, University of Kansas, United StatesReviewed by:

Jacqueline Joy Sack, University of Houston–Downtown, United StatesChristine Beaudry, Nevada State College, United States

Copyright © 2021 Karalis Noel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tiffany Karalis Noel, dGJrYXJhbGlAYnVmZmFsby5lZHU=

Tiffany Karalis Noel

Tiffany Karalis Noel