- Department of Public Health Education, North Carolina Central University, Durham, NC, United States

The benefits of debate as an effective pedagogical tool in higher education are well-published. It fosters students’ development of critical thinking, collaboration, creativity, and communication skills. This paper describes a conceptual model of debate categories: in-class debate, co-curricular debate, and tournament debate. It proposes six levels of debate for faculty to employ to create engaged active learning experiences. It is a case study written from the perspective of faculty who served as debate coaches over a four-year period. It shares lessons learned and best practices for recruiting and preparing undergraduate students for a co-curricular debate competition, a subject that is missing in the literature.

Introduction and Literature Review

Collegiate debate is a widely implemented teaching method in higher education across several disciplines including: accounting (Camp and Schnader, 2010) argumentative writing (Dickson, 2004), economics (Vo and Morris, 2006), marketing (Roy and Macchiette, 2005), mathematics and statistics (Stewart and Stewart, 2014), nursing (Doody and Condon, 2012; Hanna, 2014) political science (Omelicheva, 2005), psychology (Elliott, 1993; Budesheim and Lundquist, 1999), public health (Nelson-Hurwitz and Buchthal, 2019), and technology (Scott, 2008). In addition, its popularity is growing in pharmacy (Peasah and Marshall, 2017; Hanna et al., 2018; Hogan and Dunne, 2018; Viswesh et al., 2018) and medicine (Koklanaris et al., 2008; Nguyen and Hirsch, 2011). Collegiate debate is favored because it promotes student learning and simultaneously builds essential skills. The Partnership for 21st Century Learning refers to these skills as the four Cs: communication, collaboration, creativity, and critical thinking (P21, 2006). Experts suggests that educators combine technical and specialized skills with more strategic communication skills to create the kind of workers needed in the 21st century (National Consortium for Public Health Workforce Development and the deBeaumont Foundation, n.d.). In their survey of 431 U.S. employers, representing over two million employees across multiple fields and industries, a quarter of respondents indicated that their four-year college graduate new hires lacked skills in these areas (P21, 2006). Previous research indicates that debate addresses the four Cs which can foster a competitive edge for students as they prepare to transition from their undergraduate studies to employment (Elliott, 2015).

Pedagogical Framework

Debate Pedagogy

Debate provides an alternative to traditional lecture-based pedagogy, focusing the attention on the learner through assigned advocacy, research, argumentation, and teamwork. Vo and Morris (2006) explain when debate is used as a supplement to lecture, it creates an environment that converts students from receivers to engaged participants. Shulman (2005) posits that “learning begins with student engagement” (p.38) Debate provides for active learning (Grocia, 2018) and team-based learning (Nelson-Hurwitz and Buchthal, 2019) and it enhances civic education (Zorwich and Wade, 2016). Team-based learning has been highly successful in higher education when compared to the traditional lecture-based format “as evidenced by changes in student self-reported understanding of course content and increases in assessment-based content knowledge” (Nelson-Hurwitz and Buchthal, 2019, p.2). Debate, which has been used in civic education for well over a century (Keith, 2007), enhances civic engagement “by supporting the development of critical thinking and communication skills” (Zorwick and Wade, 2016, p. 438). Scott (2008) believes that the process of debate promotes “listening, researching, problem solving, reasoning, questioning, and communicating” (p.40). Through debate, educators create space for disagreement, assigned advocacy and structured argumentation as a way to “increase student civility, knowledge and tolerance for dissent” (Moore, 2011, p.145). We describe a conceptual model for categorizing collegiate debate.

Conceptualizing Collegiate Debate

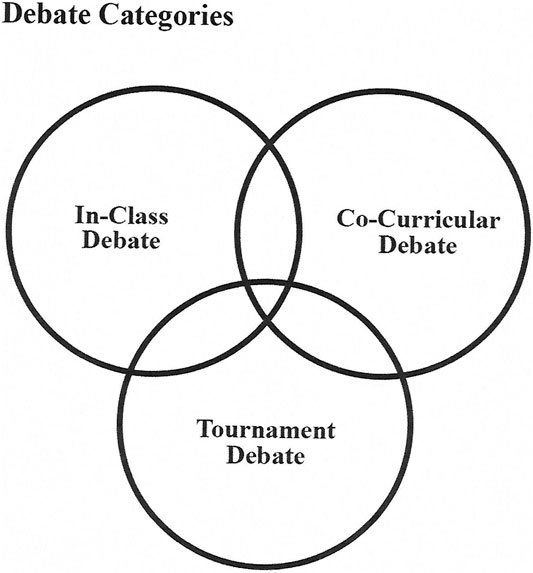

A review of the literature suggests that collegiate debate can address a range of curricular needs. We describe debate in three categories: in-class debate, co-curricular debate, and tournament debate. Figure 1 illustrates the non-linear, dynamic and overlapping relationship of the categories. In-class debate can be a door to co-curricular and tournament debates. Tournament debates can strengthen students’ skill sets in co-curricular and in-class debates. In each category, students learn to: recognize debate format and style, conduct research, collaborate with peers, develop affirmative and/or negative arguments, deliver persuasive arguments, and receive evaluative feedback. There are some differences between the debate categories that we will discuss here.

In-class debate is the first category and it is commonly discussed in the literature, however it may be underutilized in higher education (Omelicheva, 2005). We define in-class debate as an activity that occurs within a specific course for enrolled students. Students are required to participate in the in-class debate as part of their grade. These debates tend to take place during class time. This type of debate is usually a supplement to a traditional-based lecture on topics which align with course material. For example, in a public health education course students may have a debate about health care reform (Nguyen and Hirsch, 2011), health literacy (Temple, 1997), or drug abuse (Gibson, 2004). The overall quality of the in-class debate is evaluated by faculty and, perhaps the students too. Faculty, who want to incorporate a debate into their course curriculum, may also consider mock debate (Nicaise and Brown, 1997), guided debates (Hanna, 2014), or convince the professor (Nichols, 2012). Tessier’s (2009) work examines a series of debate formats and how each impacts student learning. Hanna (2014) writes that, “the purpose of in-class debates is not to produce winners or losers; rather to examine a question from all angles in a scholarly manner” (p. 352). In summary, the literature offers a variety of materials including debate formats, sample questions, resolution statements, response sheets, and assessments.

The second category is co-curricular debate. Previous research describes co-curricular engagement as, “a range of out of class activities, including community service, Greek life, student government, honor societies, sports teams, employment, and clubs” (Glass et al., 2017, p. 899). We add co-curricular debate to this list. Compared to in-class debate, co-curricular debate is voluntary and the topics are not course-specific. Although the students do not earn a grade, judges score their performance and the winners are acknowledged (e.g., prize, trophy, certificate). We further define co-curricular debate as occurring within an intramural setting, so for a topic like health care reform, it invites students from other disciplines (e.g., public health education, criminal justice, political science, social work, etc.). This interdisciplinary approach allows students to develop a greater respect for diverse perspectives in our multicultural society (Chikeleze et al., 2018) and to “draw connections” between local community and larger political issues (Leek, 2016).

The third category is tournament debate. We define tournament debate as activity that carries no academic credit, participation is voluntary, and is extramural. These debates occur at a host university and involve a high level of coordination to manage various competitive speech events for teams representing universities around the country and/or world. This type of debate is reserved for students who desire to hone their written and verbal skills through rigorous, nationally-recognized competitions. Similar to co-curricular debate, students earn scores from judges on their performance, and winners are acknowledged (e.g., prize, trophy, certificate). In comparison to in-class debate and co-curricular debate, tournament debate is more likely to have coaches who are trained in forensic science and maintain a membership roster greater than five students. It is not uncommon for tournament debate teams of this nature to receive financial support from their institution or grant funding to cover travel and other related expenses (i.e., fees, dues, hotel/lodging, meals, and transportation).

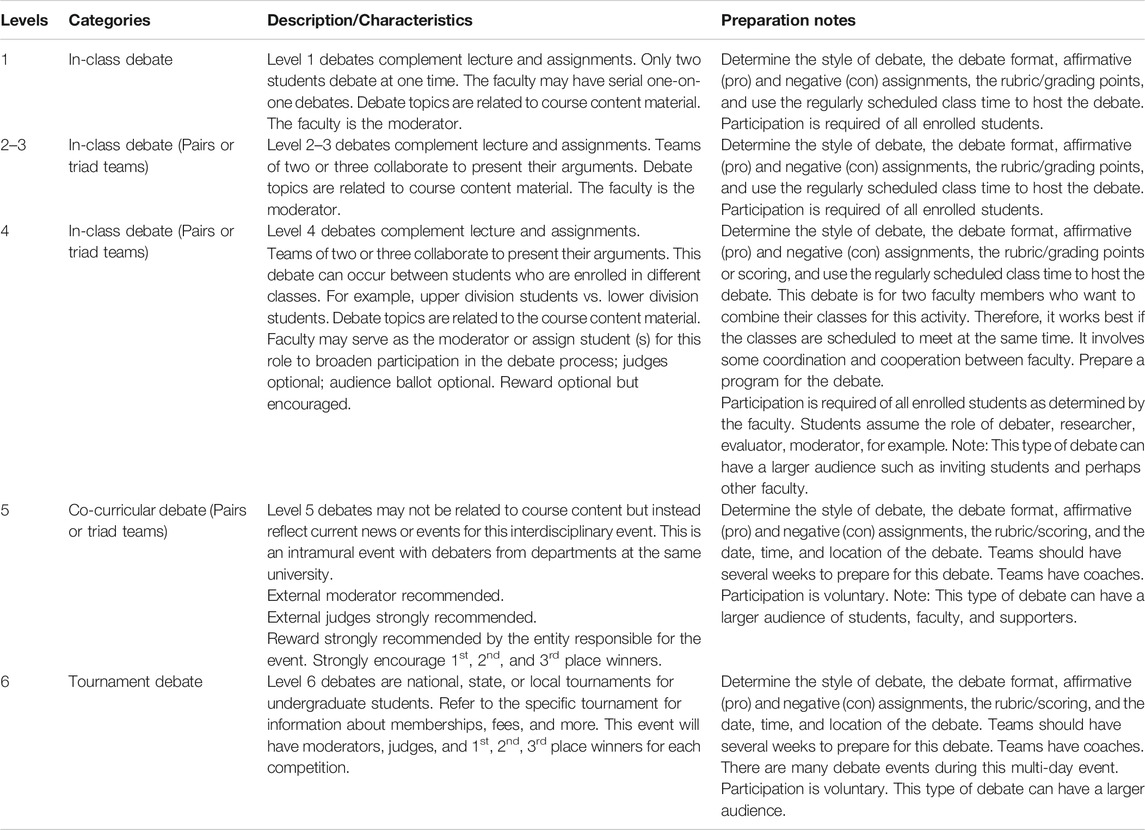

Using the three categories of debate, Table 1. displays six levels of collegiate debate. It includes the level, category, description and faculty preparation notes. The levels are ranked from 1 to 6. Levels 1–4 are variations of the in-class debate. Level 5 is the co-curricular debate. Level 6 is the tournament debate. Next, we will briefly examine tournament participation in higher education.

Tournament Participation in Higher Education

In 2015, the organizers of the Conference on Speech and Debate conducted a baseline survey to assess the status of debate in American higher education. Of the 212 debate programs in the database, 102 responded to the survey. The results indicate that the majority (80%) of debate programs had 11–50 members. At the time the survey was completed the type of institutions participating in tournaments were as follows: flagship campus of a university system (34%), branch campus of a university system (9%), regional university (12%), community college (11%), liberal arts college (29%), and other (5%). The average debate program competes in 12 tournaments per year. (Hlavacik et al., 2016). Examples of well-known tournaments include: National Debate Tournament (NDT), Cross-Examination Debate Association (CEDA), National Parliamentary Debate Association (NPDA), American Parliamentary Debate Association (APDA), National Forensic Association (NFA), and the International Parliamentary Debate Association (IPDA). Each tournament hosts several debate style competitions for students to showcase their skills (e.g., Parliamentary, Extemporaneous speaking, Lincoln-Douglass, Mock trial).

We did not find reports that specifically mentioned the participation of historically, black colleges and universities (HBCUs) in tournament debates. However, we reviewed a 2004 report published for the American Forensic Association that focused on the lack of diversity in higher education debate competitions. The results were encouraging. Although the participation of European whites outnumbered that of other racial/ethnic groups, the authors noted consistent gains among non-whites and among women as coaches and on teams. They noted that depending on the debate style, non-white participation hovered between 9%–25% and referred to these statistics as “substantial” (p. 181). Lastly, the authors recommended diverse leadership in forensic science to represent the growing demographic of society (Allen et al., 2004). Still, this report was published more than 15 years ago and to understand the current status of women, non-whites, and HBCUs in tournament debate a follow-up study is needed.

We are enthusiastic to highlight the efforts of Dr. Christopher Medina, the first Executive Director of the National HBCU Speech and Debate League that launched in 2018. He is quoted as stating, “Debate is probably the most powerful educational activity ever created. [Debate] is a profound pedagogy that provides students with skills and educational opportunities which can be used throughout a student’s life, regardless of their chosen career path.” Retrieved December 12, 2020 (https://theundefeated.com/features/wiley-college-create-hbcu-speech-debate-league/). Since its inception, the National HBCU Speech and Debate League has been held at Wiley College (2018), Tennessee State University (2019), and Prairie View A & M University (2020). Dr. Medina’s initiative addresses inclusion on the national level, but what about the state and local levels? Cates and Eaves (1996) suggest that one way to diversify forensic science is through campus speech contests. We agree and further stipulate that collegiate debate is particularly relevant for underrepresented students because it provides an engaging experience to build the four Cs. As we encourage faculty to employ in-class debates, we also invite them to consider campus-wide debate competitions. Here we present our observations on the most significant challenges faculty coaches are likely to face–recruiting students and preparing them to debate. We share our lessons learned and highlight best practices from four years of collegiate debate competitions.

Background: HBCU Case Study

In spring 2014, the College of Behavioral and Social Sciences (CBSS) announced a new initiative, an inaugural debate competition to demonstrate students’ ability to communicate effectively in a contest between Departmental units. The event was titled, The Great Debate inspired by the 2007 film, The Great Debaters. The film is about the real-life events of the 1935 historic debate win by Wiley College over the University of Southern California (USC). It is a compelling film (Black et al., 2007).

CBSS was the largest of four undergraduate academic programs on the campus. It consisted of nine units: Human Sciences, Nursing, Psychology, Public Health Education, Kinesiology and Recreation, Criminal Justice, Political Science, Public Administration, and Social Work. The Departmental units were invited to participate. Each unit had to identify faculty to coach and the coaches had to recruit three majors to form a qualifying team. We had 2-3 faculty (two females and one male) coaches for the co-curricular debates at our university in 2014, 2015, 2017, and 2018. The College did not host the debate in 2016. For the structure of The Great Debate to work, CBSS had to have commitment from a minimum of four teams for three rounds of competition.

• Round 1 (Preliminary)—Department X and Department Y

• Round 2 (Preliminary)—Department A and Department B

Winners of Round 1 and Round 2 announced; coin toss; brief intermission

• Round 3 (Advanced)—The Great Debate Winners

Coaches and debaters knew their preliminary Round resolution statements, their position (affirmative/pro or negative/con), and the Round 3 resolution statements. If a team advanced to Round 3, then they learned which position to argue with a coin toss on debate night. Therefore, coaches had to prepare their team to effectively argue either side of the resolution statement. We describe the strategies we used to recruit and prepare novice undergraduates to debate competitively within a six-week timeframe.

Recruiting Students

Each year we were tasked to recruit a new team in order to participate in CBSS competition. In 2014 and 2015, we communicated with our majors about the competition via email and in-person. We scheduled a Debate Team Interest Meeting and then shared that information flyer with them through our Majors’ listserv. We also attended the Majors’ meeting to discuss it and respond to questions. These strategies were successful with recruiting a team. However, in 2017, these strategies alone were not enough to get students’ attention. In hindsight, we believe the absence of a 2016 debate competition played a role; it was as if we lost momentum. When we asked students about joining the debate team, they told us that they needed a better understanding of the time commitment (i.e. meetings and practice). To respond to the students, we hosted a mock debate as a “try-out” for the debate team. We believed that if students participated in the mock debate then they would get firsthand experience about the level of effort it takes to develop and deliver a well-written argument. There were two unintended consequences from the mock debate. It seemed as though the mock debate changed students’ perceptions of the debate team from an optional activity to a coveted opportunity to represent the Department by earning a spot. In other words, the mock debate raised the profile. In addition, the mock debate was beneficial for us, as coaches. It gave us a chance to preview the skill sets of the students; to witness their preparation as well as their extemporaneous responses. Prior to the mock debate, we informed the participants of the debate topic and the resolution statement. We also provided them with a guided notes sheet to assist them in developing their arguments. We asked them to arrive on time dressed in business casual attire. The mock debate proved to be a best practice strategy to recruit for the debate team. In 2018, our alumni debaters were engaged in their internships and preparing for graduation. Similar to what we had experienced in the past, we needed to recruit a new team. We began by using the previous strategies, however student interest was low. We asked our faculty to recommend students and/or refer students to us, and although students contacted us, ultimately they did not join the debate team. We were short on ideas except one. We decided to approach students one-on-one who were enrolled in our classes that semester. We focused on students who were in good academic standing and who had demonstrated that they were willing. All three students agreed to join the debate team. It was not until weeks later, during the debate preparation phase that our debaters shared with us how much it meant to them for us to express belief in them. It was the singular action that motivated them to join the team. The most important lessons learned from our experiences with recruiting were to schedule an interest meeting, manage all of the logistics of that, and to connect with the students directly to better understand their hesitancy. Overall, we learned to adapt our recruitment strategies.

Preparing Debaters

As challenging as it was to recruit the students, we now had to figure out how to coach them without any previous debate team experience of our own. The first thing we did was to have a coaches meeting to determine our availability to meet with our team. The most important task for preparing for a debate is to set a regular meeting schedule. We learned that it was better to meet with our team after we, the coaches, met to draft a Debate Team Calendar. We presented it to them pre-populated with days and times, asked about competing responsibilities, and edited it as necessary. Weekly debate meetings are necessary. We recommend meeting twice a week. Our meetings were during the day on Tuesdays and then again on either a Thursday or Friday evening of the same week. Day time meetings were brief (30–40 min) as the team and the coaches had class meetings to attend. The evening meetings were longer (4:30 p.m.–6:30 p.m.). Every meeting had an agenda that we modified as necessary at the start. We strongly recommend securing a reliable location for your team meetings. We reserved a small conference room with a large table, for plenty of seating, and a white board with dry erase makers, pens, notebooks, color markers, and poster paper to support brainstorming sessions. In 2014 and 2015, we met with the team up to the night before the competition. This strategy left little time to relax and reflect. In 2017 and 2018, instead of the coaches meeting with the team, we strongly encouraged the debaters to come together to meet. We believed that it was very important for them to collaborate without us, to trust each other, listen to each other, and to rely on each other. In fact, our 2018 team shared that they, often met virtually, using technology apps such as FaceTime © and Group Me ©. Overall, we believe that the time that they spent together gave them an opportunity to bond and fuel their debate night performances.

We knew that in order for our evening meetings to be productive and supportive, we needed to anticipate and plan for meals. We, the coaches, voluntarily shared the responsibility for bringing snacks, drinks, and food for meetings. It allowed us to take breaks and then regain our focus on the debate preparation. We were a team of colleagues who supported each other and our debaters, so although we did not receive individual financial compensation, we recognized the benefits to our students and we did not allow this to be a barrier.

In 2014 and 2015, we video-recorded our rehearsals to allow students to critique their performance (not a popular method among the students). We also randomly put them on the spot (mixed reviews on this method). Based on our experience, two of our best strategies were role-playing and using materials/resources (e.g. guided notes, binders, and Blackboard ©. One of the coaches has a background in communication and this was her favorite method. She readily would use the counter position to get the debaters engaged. The students often had very good responses that they incorporated into their notes. Role-playing also ushered in moments of fun, laughter, and overall enjoyment which added a meaningful dimension to the experience for us all.

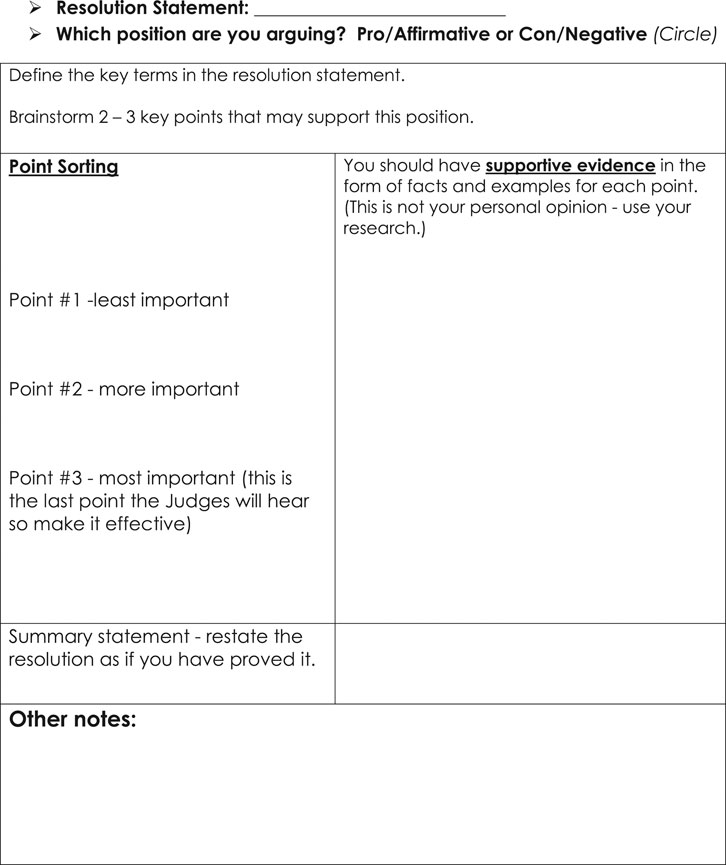

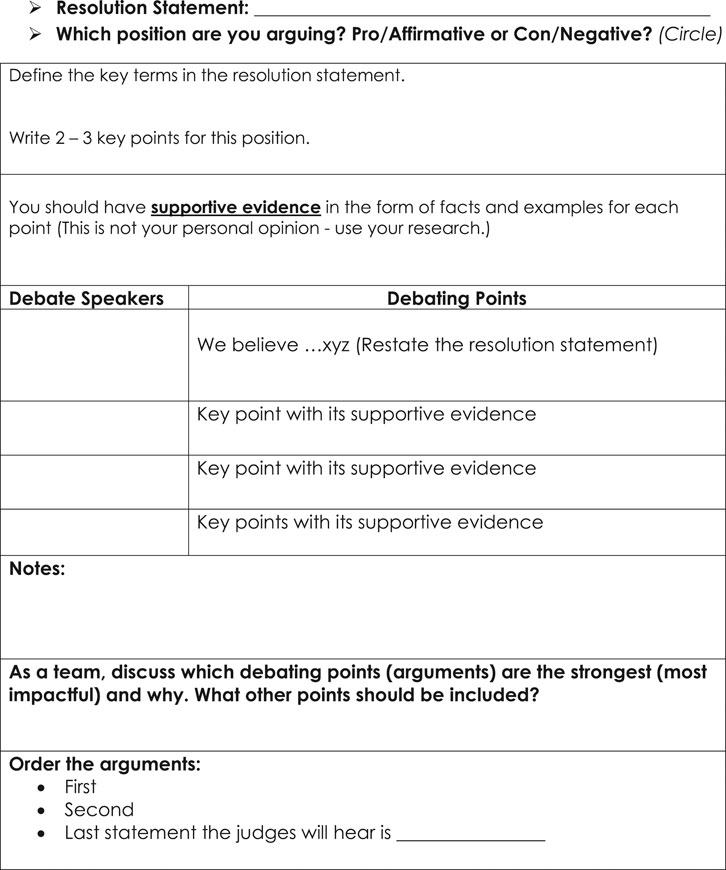

We recognized that although students had volunteered to debate, they may have had little, if any, experience with debating. We had to familiarize them with the terminology and provide guidance. As a result, we developed two guided notes sheets. Figure 2 is the Debater Guided Notes Sheet. Its purpose was to promote introspective, critical thinking on the topic/resolution statement so that when we met as a team, everyone could contribute to the discussion. Figure 3 is the Team Guided Notes Sheet. Its purpose was to combine or situate the ideas from the debaters during meetings. We also used it to assign arguments to ensure equal speech participation. We identified each debater’s strengths and used that knowledge to assign arguments.

The guided notes sheets gave the students an understanding of how to build and sort arguments. We learned in 2014 and 2015, that our debaters were often arriving at the meetings after having come from elsewhere (i.e., workplace, gym, etc.) so they may not have the notebook that they used for the debate team. To address this issue, in 2017 and 2018, we provided 3-ring binders to each debater. The 3-ring binder included the Debate Team Calendar, the agendas, the resolution statements, and the guided notes sheets. The debaters added their own research and other materials as the weeks progressed. We believe that the guided notes sheets and binder set the expectation for the debaters to be prepared and engaged in the process.

We used the University’s learning management system (LMS) Blackboard © (Bb) in 2017 and 2018 to manage all materials and communication for the debate team. In Bb the debaters were assigned the “student role” and the coaches were assigned “the instructor role”. In addition to the administrative benefits of using Bb, like fewer emails, it gave us a hub for our research materials such as, YouTube videos, data charts and tables. We especially liked to post YouTube videos on public speaking, the debate styles, and research content. For example, for an argument related to the #Me Too Movement we posted interviews of its founder, Ms. Tarana Burke and the University’s sexual harassment policy as part of the background research. We also used our Bb course after the Debate to upload judges’ feedback in the form of scoring sheets and comments. We recommend that coaches at other institutions use their LMS system to organize materials for easy access by debaters and coaches.

The last best practice is, perhaps the most obvious for a debate team, we decided to wear a uniform. Uniforms build a sense of belonging and teamwork. In 2017, the debate team consisted of two males and one female. They decided to wear polo shirts and black bottoms (pants/skirt). One of our coaches is an expert embroiderer and so he ordered the polo shirts for us all and stitched the logo and the team name on them. The 2018 team was all females and because the theme was about #Me Too and the gender roles, they decided to wear white tops black skirts and neck ties.

Conclusion

We were immersed in the experience of coaching our students. We did not plan or pause to create an instrument to objectively measure the four Cs: critical thinking, collaboration, creativity, and communication. In the future, we will conduct pre and post-test surveys to better quantify their growth in these areas. We also plan to conduct interviews to capture their debate team experience. We hope to maintain a team, have a team captain, and schedule competitive events with nearby institutions. Yet, in this moment, we offer what we witnessed as we supported our teams to participate in the collegiate debate.

We watched as our teams upgraded their technical writing skills to develop compelling opening and closing statements. They used critical thinking skills every time they listened, huddled, and then intentionally selected the appropriate arguments to counter what they heard - in rehearsal and on stage. During role-play they learned to articulate on-the-spot, not by giving their opinion alone but supporting it with evidence. In fact, they learned how to argue well for issues that they did opposed personally, urging them to see things from another point of view. Because they were prepared to argue either side of the resolution, they listened for key words and then quickly passed notes to signal which of them should take the microphone next. They critiqued one another’s speeches. They infused their speech with just the right dose of popular culture, music, movies and television to add interest to their prepared statements. They creatively added colloquialisms, slang, jargon, the use of rhythm, and words spoken in unison to add drama, make arguments memorable and capture the attention of the audience and the judges. They delivered non-verbal communication gestures and facial expressions to embody their message. They elevated their professionalism and rose in confidence. They trust each other. They had moments of fun and moments of doubt and they had us to support them the whole way. Throughout the process, we watched them gain an appreciation for the power of their words and the ways to communicate them effectively. We realize now that we were not just preparing them for a collegiate debate but to compete on the next level.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We, the coaches, dedicate this paper to the NCCU Public Health Education Debate Team Participants in 2014, 2015, 2017, and 2018.

References

Allen, M., Trejo, M., Bartanen, M., Schroeder, A., and Ulrich, T. (2004). Diversity in United States forensics: a report on research conducted for the American forensic association. Argument. Advocacy 40, 173–184. doi:10.1080/00028533.2004.11821605

Black, T., Forte, K., Winfrey, O., Roth, J., and Washington, D. (2007). The great debaters, Chicago, IL: Harpo Films.

Budesheim, T. L., and Lundquist, A. R. (1999). Consider the opposite: opening minds through in-class debates on course-related controversies. Teach. Psychol. 26 (2), 106–110. doi:10.1207/s15328023top2602_5

Camp, J. M., and Schnader, A. L. (2010). Using debate to enhance critical thinking in the accounting classroom: the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and U.S. tax policy. Issues Account. Educ. 25 (4), 655–675. doi:10.2308/iace.2010.25.4.655

Cates, C., and Eaves, M. (1996). Reaching new campus audiences: conducting a campus speech contest as a non-tournament activity. South. J. Forens. 1, 104–111.

Chikeleze, M., Johnson, I., and Gibson, T. (2018). Let's argue: using debate to teach critical thinking and communication skills to future leaders. J. Leader. Educ. 18, 123–137. doi:10.12806/V17/I2/A4

Dickson, R. (2004). Developing “Real-World intelligence”: teaching argumentative writing through debate. English J. 94 (1), 34–40. doi:10.2307/4128845

Doody, O., and Condon, M. (2012). Increasing student involvement and learning through using debate as an assessment. Nurse Educ. Pract. 12, 232–237. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2012.03.002

Elliot, L. B. (1993). Using debates to teach the psychology of women. Teach. Psychol. 20 (1), 35–38. doi:10.1207/s15328023top2001_7

Gibson, R. (2004). Using debating to teach about controversial drug issues. Am. J. Health Educ. 35 (1), 52–53. doi:10.1080/19325037.2004.10603606

Glass, C. R., Gesing, P., Hales, A., and Cong, C. (2017). Faculty as bridges to co-curricular engagement and community for first-generation international students. Stud. Higher Educ. 42 (5), 895–910. doi:10.1080/03075079.2017.1293877

Grocia, J. E. (2018). What is student engagement? New Direct. Teach. Learn. 2018 (154), 11–20. doi:10.1002/tl.20287

Hanna, D. R. (2014). Using guided debates to teach current issues. J. Nurs. Educ. 53 (6), 352–355. doi:10.3928/01484834-20140512-04

Hanna, L. A., Barry, J., Donnelly, R., Hughes, F., Jones, D., Laverty, G., et al. (2018). Using debate to teach pharmacy students about ethical issues. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 78 (3), 57–58. doi:10.5688/ajpe78357

Hlavacik, M., Lain, B., Ivanovic, M., and Ontiveros-Kersch, B. (2016). The state of college debate according to a survey of its coaches: data to ground the discussion of debate and civic engagement. Commun. Educ. 65 (4), 382–396. doi:10.1080/03634523.2016.1203006

Hogan, S., and Dunne, J. (2018). Evaluating the effectiveness of a focused debate on the development of ethical reasoning skills in pharmacy technician students. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 82 (6), 660–669. doi:10.5688/ajpe6280

Keith, W. M. (2007). Democracy as discussion: civic education and the American forum movement. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Koklanaris, N., Mackenzie, A. P., Fino, M. E., Arslan, A. A., and Seubert, D. E. (2008). Debate preparation/participation: an active, effective learning tool. Teach. Learn. Med. 20 (3), 235–238. doi:10.1080/10401330802199534

Leek, D. R. (2016). Policy debate pedagogy: a complementary strategy for civic and political engagement through service-learning. Commun. Educ. 65 (4), 397–408. doi:10.1080/03634523.2016.1203004

Moore, T. J. (2011). Critical thinking and disciplinary thinking: a continuing debate. Higher Educ. Res. Dev. 30, 261–274. doi:10.1080/07294360.2010.501328

National Consortium for Public Health Workforce Development and the deBeaumont Foundation (n.d.). Building skills for a more strategic public health workforce: A Call to Action.

Nelson-Hurwitz, D. C., and Buchthal, O. V. (2019). Using deliberative pedagogy as a tool for critical thinking and career preparation among undergraduate public health students. Front. Public Health 7, 1–8. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2019.00037

Nguyen, V. Q. C., and Hirsch, M. (2011). Use of policy debate to teach residents about health care reform. J. Graduate Med. Educ. 376, 378. doi:10.4300/JGME-03-03-32

Nicaise, M., and Brown, J. (1997). Evaluating student learning with mock debates. Contemp. Educ. 68 (2), 131–135.

Nichols, Ms. (2012). Convince the professor- classroom debate with a twist. Teach. Theol. Relig. 15 (1), 41–42.

Omelicheva, M. Y. (2005). “There’s No debate about using debates! Instructional and assessment functions of educational debates in political science curricula conference papers – American political science association,” in presented at the 2nd annual APSA Conference on teaching and learning in political science, Washington, DC, 1–40.

P21, (2006). The conference board, corporate voices for working families, & society of human resource managers are they really ready to work?. Washington, DC: P21.

Peasah, S. K., and Marshall, L. L. (2017). The use of debates as an active learning tool in a college of pharmacy healthcare delivery course. Currents Pharm. Teach. Learn. 9, 433–440. doi:10.1016/j.cptl.2017.01.012

Roy, A., and Macchiette, B. (2005). Debating the issues: a tool for augmenting critical thinking skills of marketing students. J. Marketing Educ. 27, 264–276. doi:10.1177/0273475305280533

Scott, S. (2008). Perceptions of students’ learning critical thinking through debate in a technology classroom: a case study. J. Tech. Stud. 10 (2), 115–119. doi:10.21061/jots.v34i1.a.5

Shulman, L. (2002). Making differences: a table of learning. Change 34 (6), 36–44. doi:10.1080/00091380209605567

Stewart, S., and Stewart, W. (2014). Teaching Bayesian statistics to undergraduate students through debate. Engl. J. 94 (1), 34–40. doi:10.1080/14703297.2013.791553

Temple, M. A. (1997). Using debate to develop health literacy. J. Sch. Health 67 (3), 116–117. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.1997.tb03427.x

Tessier, J. T. (2009). Classroom Debate Format – effect on student learning and revelations about student tendencies. Coll. Teach. 57 (8), 144–152. doi:10.3200/ctch.57.3.144-152

Viswesh, V., Yang, H., and Gupta, V. (2018). Evaluation of a modified debate exercise adapted to the pedagogy of team-based learning. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 82 (4), 345–353. doi:10.5688/ajpe6278

Vo, H. X., and Morris, R. L. (2006). Debate as a tool in teaching economics: rationale, technique, and some evidence. J. Educ. Business 81 (6), 315–320. doi:10.3200/joeb.81.6.315-320

Keywords: communication1, critical thinking2, collaboration3, creativity4, debate5, undergraduate6, health education7, pedagogy8

Citation: Wordlaw L, Harrell KJ and Romocki LS (2021) Recruiting and Preparing Undergraduate Students for a Collegiate Debate: An HBCU Case Study. Front. Educ. 6:562328. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.562328

Received: 18 May 2020; Accepted: 16 February 2021;

Published: 20 April 2021.

Edited by:

Ida Ah Chee Mok, The University of Hong Kong, Hong KongReviewed by:

Krista Mincey, Xavier University of Louisiana, United StatesChristopher Thompson, Monash University, Australia

Copyright © 2021 Wordlaw, Harrell and Romocki. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: LaShawn Wordlaw, bC53b3JkbGF3QG5jY3UuZWR1

LaShawn Wordlaw

LaShawn Wordlaw Kevin J. Harrell

Kevin J. Harrell LaHoma Smith Romocki

LaHoma Smith Romocki