94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 28 April 2021

Sec. Leadership in Education

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.550058

This article is part of the Research TopicWays of Seeing Women’s Leadership in Education: Stories, Images, Metaphors, Methods and TheoriesView all 20 articles

Cartooning and graphic facilitation (the latter of which includes developing visuals in real time with groups) offer increasingly popular yet highly subjective approaches to public engagement, organizational development, communication, research, and research dissemination. Values-based cartooning can provide an ethical framework for those undertaking and commissioning these kinds of practices, and it has been employed by the author as a method for accessing and representing diverse perspectives and experiences for more than two decades. This article is situated within the author’s experience as a practitioner undertaking a range of commissions and partnerships relating to education in the United Kingdom. What follows is a critical examination of three contexts where values-based cartooning has been used to represent women’s leadership within education: within research into women’s experiences of working and studying in a higher education institution, within grassroots movements led by teachers and school leaders, and within broader campaigns that have educational value. This involves negotiation of complex social issues while developing visuals, including how to treat gender, race, and intersectional identities within word/image combinations. Questions are raised about the purposes of visual practice, the roles and responsibilities of practitioners, and the conditions of production, audience, and social media. What are the benefits, limitations, and risks of values-based cartooning in relation to the visual representation of women’s leadership in education? What is the value of portraying the kinds of leadership that exist at different levels, including outside of formal, professional roles and beyond classroom practice and systems leadership? And finally, how should visual practitioners respond to conflicting values, risk, failure, and nuance in relation to women’s leadership, where there is strong desire and need for positive, strengths-based depictions? The author considers her positionality in relation to the type of work undertaken and asks whether this kind of visual practice may in fact represent a particular form of leadership that warrants further inquiry. This article will be of interest to educators, researchers, facilitators, artists, cartoonists, campaigners, graphic and visual facilitators, practice-based researchers, and those who commission and evaluate visual methods.

I remember sitting up straight with my back to the conference, facing a large pinboard covered in glaring white paper, my right arm raised as I held a well-worn paint brush soaked in cadmium. I was balanced on the edge of a maroon velvet chair, not at all ladylike with my feet and knees wide apart, comfortable trousers, sensible flat shoes solid on a recently vacuumed carpet. As a graphic recorder, my role was to visually capture key themes from the Learning Together alumni event, an inclusive educational program led by two women, Drs. Amy Ludlow and Ruth Armstrong. This bold collaboration brought together universities and prisons, students inside and outside of the criminal justice system, a network of committed organisations and individuals.

I was listening to the speakers intently. I had drawn Learning Together’s logo (a giant fingerprint) and quoted author, actor, and prison activist Bryonn Bain, his caricature with burnt umber skin tone, black t-shirt, and flat cap centered on the page. He held a giant rose by the stem, its thorns challenging the participant’s poetic words, which were handwritten around it. Underneath him, I had begun drawing a woman wearing a scarlet A-line skirt. I was just about to blend the red folds of fabric when the terrorist attack took place. I do not want to describe the horror of what happened next, except to say that someone told us to stay in the room, then someone told us to run. I could think only of what might happen to my daughter if something happened to me. This was not my first experience of violence.

I will not name the educational leader I was representing at that moment, because, unlike with Bryonn Bain, I do not have her permission. The act of identifying and making people visible through research and/or visual practice is complex, risky, and ethically loaded.

Over the next twenty-four hours, the picture of what actually happened became both clearer and increasingly blurred, the pixels in my mind contaminated. I learnt that conference participant Usman Khan had attacked people, had killed educators Saskia Jones and Jack Merritt. Mothers, fathers, a girlfriend, siblings, friends, and colleagues had lost people they loved. I was sickened by the media’s hunger for sensationalism, astonished by the stories of the men who saved our lives, stressed by conflicting accounts of what happened. I read Islamophobic tweets, opportunistic, knee-jerk political responses, a tabloid newspaper article attacking a leading academic for her work with ex-offenders.

I saw that the enthusiastic tweets I had posted about the event prior to the attack had been published in the Daily Mail, alongside a photograph of Usman Khan surrounded by police (Webber, 2019). I was identified and trolled. My words and my doctorate were ridiculed through the editor’s intentional juxtaposition of word and image. I felt isolated, painfully aware of the lack of entitlements and protections afforded to those who work for themselves. I felt single.

Over time, a blanket of bitter smog crept across my brain, the once vibrant images and connections in my head now grayscale, full of noise, dust, and scratches. A once gentle, sensory wave of watercolor now has the look of a virus spreading. A heavy, aching paralysis crept across the hand I draw and write with. My treasured camera, I am told, is lost, my artwork destroyed. I know that the sharp, chisel-tip pens and corrupted paint pallet recovered from the “scene” can be used to represent grief, violence, and hate, just as graphically as they can capture and spread love, hope, and humanity. I can no longer seem to finish my drawings or mark my students’ essays.

I begin this interdisciplinary, practice-based discussion with a personal perspective on an experience I had while undertaking formally commissioned work at an alumni celebration for Learning Together, University of Cambridge, at Fishmongers Hall, London Bridge, on 29 November, 2019 (Armstrong and Ludlow, 2020). Tragically, a terrorist attack at this event resulted in the deaths of two beautiful, young, and talented educators, along with the death of the conference participant who carried out the attack and the injury and suffering of many others.

When the Metropolitan Police eventually return some my belongings, each item is separately bagged and carefully labeled. My dented, disorganized paint pallet had been with me for years, and I use it once again as I listen to other people’s stories and perspectives, noticing shared values, common themes, connections, and contrasts across communities, organizations, movements, disciplines, and sectors. I record “Community Conversations: Tackling Youth Violence in Lambeth,” a conference lead by Ros Griffiths and Margaret Pierre. We begin with a two-minute silence for all the young people who have been lost through violence, followed by a powerful presentation from Tracey Ford, who founded the JAGS Foundation in response to the murder of her son James at the age of seventeen. Hundreds of young people fill the town hall, engaging in intergenerational conversations calling for action to address the root causes of violence: poverty, discrimination, exclusion, domestic violence, unprocessed trauma, toxic masculinity, a lack of opportunity, a lack of support. The role of teachers, youth workers, and community leaders who understand the realities of these young people’s everyday lives is described as “pivotal.” As a middle-aged woman, I reflect on the way young people engage, learn, play, create, connect, and collaborate in 2020, and I consider the importance of teaching, learning, and practicing critical-thinking skills in relation to visual communications.

The terrorist attack had a direct impact on my visual practice and ability to write this article. Clouded with PTSD, I struggled to develop my original abstract and tried to bully this piece into an objective shape, but it slipped out of my grasp every time I deleted references to that day. This article, the unfinished artwork from the Learning Together event, and a subsequent article in The Guardian (Mendonça, 2019a) are now a part of my portfolio. The experience is included here because it now informs not only what I do as a researcher, cartoonist, and teacher but also influences how I read and reflect on previous work and scholarship. Through the writing of this article I take stock. I am grateful for my life, for the diversity of my family, friends, and colleagues. I consider the roles, responsibilities, and biases of a leader in the fields of graphic facilitation and cartooning. I simultaneously appreciate the opportunity to write such an article and wince at the foolishness of undertaking another unpaid commitment, as a self-employed single mother during a global pandemic.

Until recently, contemporary scholarship on visual and arts-based methods (Pink, 2013; Kara, 2015; Leavy, 2015; Mannay, 2015; Rose, 2016; Mitchell et al., 2017) has tended not to include detailed discussion of graphic or visual facilitation, graphic recording, or associated practices. These methods have been used within academic research for decades, but are often not adequately acknowledged, contextualized, or even credited; only now are they beginning to be taken more seriously within the academy. Comics scholarship, which can include cartooning in its widest sense, is now thriving across many parts of the world. Through my research I have brought this type of visual practice, which unlike many approaches to illustration involves writing and facilitation skills as much as drawing skills, into the realm of cartooning and comics studies (Mendonça, 2016). My PhD research into values-based cartooning included a case study that involved drawing and writing with and about single pregnant women aged between 16 and 52 years of age (Mendonça, 2019b). It sought to develop a critical visual practice that recognizes and critically examines “the particular and special knowledge of the practitioner” (Gray and Malins, 2004: 22). My interest here relates particularly to the role of the independent visual practitioner. In recent years, graphic facilitation and associated visual practices have enjoyed a sharp rise in popularity. Individuals and partnerships bring their own beliefs, knowledge, skills, and “hands” to diverse contexts, including situations where views may be polarized or even extreme. As such, serious consideration of ethical concerns in practices that include cartooning is now vital.

The aim of this article is to consider how values-based cartooning might contribute to, and/or raise questions about, ways of seeing women’s leadership in education. What are the insights, challenges, and gaps? And what does it mean to depict the kinds of leadership that exist at different levels, including outside of formal, professional roles and beyond classroom practice, school, and systems leadership? I consider the extent to which seeking to understand and visually represent leadership may also involve demonstrating a form of leadership. This kind of leadership—which may be the result of collaboration and which may be present in the work of students, teachers, researchers, community groups, self-advocates, and others as well as that of independent visual practitioners—is less easy to define, yet potentially impactful.

Understanding visual practice as a form of leadership calls into question the way the arts, visual analysis, and practice may be undervalued, oversimplified, or ignored within the discourse around leadership in education. Building on David Sibbet’s (2012) work on visual leadership, which offers theory and tools for organizational change, I propose leadership through visual practice, where values are actively explored, negotiated, and communicated through facilitation, dialogue, writing, and imagery, and where ethical concerns are reflected within the visual and textual content and tone of artwork as well as the behavior of the practitioner. Here, an individual’s contribution across multiple contexts, communities, organizations, movements, disciplines, and sectors is considered as a singular, unique, intertextual body of work, a new narrative reflecting a process of ongoing learning, offering a privileged strategic overview, representing more than simply an endless series of minor, one-off supporting roles. If we are to consider leadership through visual practice, whether that be via values-based cartooning or another creative method, it requires critical attention not only through art education, comics scholarship, books on literature, or visual facilitation but through our exploration of what leadership constitutes, and how it is to be taught, commissioned, evaluated, and developed.

In order to examine the questions above, I begin with a brief overview of my journey to independent and critical visual practice and introduce the concept of values-based cartooning. Following this, I offer examples of three different kinds of spaces where I have employed values-based cartooning to create visual and textual representations of women’s leadership in education. For the purposes of analysis, the focus here is on my own practice, which I frame as values-based cartooning, an approach that existed long before I coined the term.

The three examples demonstrate values-based cartooning as a research method for examining the experiences and perspectives of women working and studying in higher education; as a visual approach in support of grassroots movements (mainly within English primary and secondary education); and finally, within campaigns with educational aims that exist outside of the formal education system. Following on from this, I reflect on what it means to practice values-based cartooning at a time when many women’s stories continue to lack visibility. It is a moment when Covid-19 is profoundly impacting lives, when the rights of women around the world are being eroded, and when eugenics, extremism, nationalism, sexism, racism, ableism, homophobia, transphobia, and ageism find their way into our visual and wider culture in both ever more subtle and more aggressive ways. The title of this article references Afua Hirsch’s 2018 book, Brit(ish): On Race, Identity and Belonging, a text celebrated within many of the networks included in this article. The word “line” of my title refers to a line of reasoning, to our ancestral lineage, but also to the line of the hand as it draws, paints, and writes, whether that line partitions or connects, conceals, censors, simplifies, or uncovers, whether it offends, inspires, or delights, whether it disrupts, decolonizes, or preserves. Firstly, I situate myself as a researcher and independent visual practitioner and seek to clarify the approach taken within this article.

Historian Olivette Otele, born in Cameroon and raised in Paris, has spoken of the knowledge she had as a child being dismissed by a classroom teacher and cites the values and confidence instilled in her by her grandmother as key for maintaining the legitimacy of such knowledge and inspiring further research (Channel 4, 2020). Growing up in a loving, mixed-heritage family (Pakeha and Anglo-Indian) in Otautahi Christchurch, Aotearoa New Zealand, gave me a unique lens through which to view life; we had whanau “overseas,” we knew about kofta and kulfi long before any South Asian restaurants appeared in town. Like so many others we were raised by parents who themselves had grown up with contrasting cultural vocabularies and understandings of the world, parents who learnt from each other, and fought to have their relationship accepted. Our family tree produced mysterious, uncomfortable stories of poverty and privilege, spice trades, empires and religious conversion; an earthquake in Quetta, an ambush at Gandamak, a great grandfather who disappeared to Portugal with the family fortune, leaving his wife and children in Karachi.

My way into the arts was initially autodidactic, building skills and confidence as I experimented with visual practice within roles that did not require drawing, namely social care, advocacy, and disability rights. A lack of formal art education was due in part to receiving misjudged, soul-destroying advice from teachers in 1970s/80s Aotearoa New Zealand, which went exactly as the late Sir Ken Robinson (2006) described in his talk “Do schools kill creativity?”: they said, “Don’t do art, it won’t help you to get a good job.” Those of us who do not get what we need from school education often actively seek knowledge and learning opportunities from less formal settings, activities, and relationships, which may be viewed as positive or problematic. The kind of teaching and learning in these spaces involves innovation and improvisation within less restrictive contexts, along with a different approach to risk. As such, I take a broad view of education and of ways of seeing and depicting women’s leadership in education. For me, leaders in education include the writers, the photographers, the comedians, musicians, actors, film makers and cartoonists, the freelancers, the lecturers on zero-hour contracts, the youth workers, nurses, support workers and activists, the interfaith forums, the survivors who campaign to stop violence against women and girls, the bereaved children, mothers, grandmothers, siblings, partners, and friends working with local communities for a better world. I think of those students, artists, and leaders who may have found the formal education system difficult, inflexible, discriminatory, and stifling, yet continue to find ways to learn, inspire, and educate, whether or not they have been employed or funded to do so.

As an adult living in London, I worked on mental health, learning disabilities, and equalities and human rights. It was not until my late thirties, when I had already worked as a visual practitioner for a decade, that I undertook my first degree, a BA (Hons) in Fine Art. This was at a time when graphic facilitation was rarely understood or taught within art schools; the advice given to me by the course leader prior to our degree show was to “keep your cartoons out of it.” It was a theory tutor, Dr. Dan Smith-Byrne, and a short course tutor, Dr. Katarzyna Murawska-Muthesius, who encouraged me to write about cartooning and the representation of women, despite the dismissal of my visual practice. When I found myself pregnant, self-employed, and single, it was my Masters in Citizenship Studies tutor, Dr. Ursula Murray, who convinced me that I still belonged at Birkbeck, and that research that involved single pregnancy and cartooning could be considered legitimate, interdisciplinary, and of value to the world. In order to earn a living, I soon mastered the art of breastfeeding while drawing against the wall at conferences and meetings. Single mothering has informed my visual practice, research, teaching, and learning ever since, and has helped me to further understand and question the ways in which systemic discrimination and micro-aggression can exclude and undermine people, their experiences, and knowledge.

Long before Covid-19 lockdowns, single mothers have been required to juggle the presence of children with creative and working practices, with teaching and learning (Ajandi, 2011). Many face financial challenges and, as Ella Davis (2020) points out, discrimination at work and judgment for “not meeting the standards of a family with twice the resources.” Throughout the last ten years, my daughter has (without my permission) drawn onto the walls of tiny rented flats, the inside of a Honda Jazz, my clothes, her skin, onto commissioned artwork, other people’s research at conferences, and university library books. Together we have read children’s books and watched animations (repetitively, relentlessly), at times despairing at stereotypical, predictable representations. We have sought out more interesting work, drawn our own characters, constructed our own stories. My daughter was physically present—active, chatting, writing, drawing, and critiquing my work—during the development of all of the graphics included within this article. Motherhood and childhood were ever-present.

As an independent graphic facilitator and cartoonist, my practice involves research with communities, staff and students, organizational development, training on public engagement, university lecturing, facilitating person-centered planning, and workshops with primary and secondary schools, arguably free of the constraints of the curriculum (Galton, 2010). As such, the examples presented here traverse what may be defined as formal and informal educational settings. Over more than twenty years, I have generated a visual and textual portfolio from more than one thousand commissions and partnerships, connecting across different parts of Britain’s voluntary and public sectors and contributing to the work of European and global organizations. Completed or half-drawn, cropped, annotated, photographed, and amplified, these representations sit alongside each other, and alongside other people’s work, whether that be on social media threads, profiles, and websites, in faded, dog-eared policy documents, within online academic conferences, strategy consultations, or teaching materials, rolled up in the corner of offices, or pinned to the walls of care homes and prison visiting rooms. This article is written through the lens of a visual practitioner, one who has represented multiple examples of human rights abuses and systemic failures. Echoes of ever-present inequalities haunt my work (Mendonça, 2020), just as they haunt our lives; and as Covid-19 has highlighted, the impacts of these inequalities are all too often experienced by our elders and young people, by disabled people of all ages, by women and LGBTQ+ people, and particularly by those from Black, Asian, and other racially minoritized communities (Cooper, 2020).

Throughout this article I have used “artist” and “visual practitioner” interchangeably, but there are some differences. Artists, particularly independent artists, are often associated with initiating creative responses that invite us to question the world as it is, or as we see it. As an artist and researcher, I seek out topics of interest, collaborations, and campaigns that resonate with my values, hopes, and fears for the world. My PhD research, for example, provided creative space in which to develop graphics and graphic narratives that explored the values around single pregnancy; this work, at times controversial, was unlikely to be commissioned through traditional routes. However, I also accept more straightforward contracts as a visual practitioner, in which I am agreeing to deliver the aims of a research project or organization. In some instances, for better or for worse, the boundary between these two ways of working becomes blurred; values-based cartooning, introduced below, includes all of these approaches.

Within arts scholarship women and LGBTQ+ artists have been marginalized, feminist interventions and social and political factors undermined. Griselda Pollock writes that art historical discourse “accords itself the right to choose who and what is to be considered as worthy of being studied, conserved, exhibited. It uses the highly selective criteria of value, imagined as self-evident and neutral, to create for itself an image of creativity and culture as a narcissistic mirror of those who do and preserve this selecting” (Pollock, 2013: xxv). More recently, within her stand-up show Nanette (which includes a brief review of the work of Pablo Picasso), the comedian, writer, and actor Hannah Gadsby (2018) makes an impassioned demand for an end to the dominance of white, straight, male perspective and power: “I believe we could paint a better world if we learn how to see it from all perspectives, as many perspectives as we possibly could. Because diversity is strength. Difference is a teacher. Fear difference and you learn nothing.”

Despite being historically, culturally, and theoretically significant, cartoons and comics have until recently had their relevance and value undermined in an art world that positions art practice within a hierarchy (Sabin, 1996; Beaty, 2012). Knowledge of cartooning is necessary in order to contextualize contemporary visual practices and their reception as well as to invite and commission work in an informed way. Cartooning was employed to undermine women’s agency and leadership during the fight for suffrage, via portrayals of “hysteria,” “unnatural” behavior, and “bad” motherhood. In Nazi Germany cartoons were used to dehumanize Jews and disabled people. In Britain cartoons justified policies promoting the institutionalization of learning-disabled people, while in the United States they promoted their sterilization. Offensive, sexist, racist, homophobic, ableist, and gender-violent cartoons and comics continue to be published by both alternative and mainstream news outlets. This is not without serious risk, as can be seen with the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons in Denmark in 2005, the Charlie Hebdo shooting in Paris in 2015, and more recently with the killing of history teacher Samuel Paty in Paris.

But cartooning also has a history of subverting dominant mainstream narratives, of using caricature, humor, fantasy, and drama to undermine, educate, question, campaign, and provoke, at times providing a direct challenge to stereotypical representations of women’s lives and bodies at the hands of women cartoonists. Due to its combination of word and image, cartooning can engage with intersectional identities (including less visible identities); describe structural discrimination, complex narratives, and processes; and highlight attitudes at an individual, community, and societal level. Research into the female cartoonists of the past has been undertaken by the likes of Robbins and Yronwode (1985), Lisa Tickner (1987), Diane Atkinson (1997), and Macfarlane and Young (2003), among others. The last decade has seen a welcome rise in the publication of research highlighting previously hidden histories relating to girl, women, and LGBTQ+ comics creators, educators, commissioners, and readers (Chaney, 2011; El Refaie, 2012; Gibson, 2015; Aldama, 2020; Streeten, 2020). This includes the pioneering and prolific nineteenth-century cartoonist Marie Duval (Grennan et al., 2018 and 2020). Likewise, a growing body of work is examining race (Howard and Jackson, 2013; Ayaka and Hague, 2014; Diamond, 2018); race, gender, and sexuality (Earle, 2019); and disability and illness (Czerwiec et al., 2015; Foss et al., 2016; Oliver, 2020) within comics.

Graphic (or visual) facilitation, David Sibbet explains, “uses imagery and metaphor as a way to draw out and portray profound group thinking about patterns of organization and group process – helping people literally ‘see what they mean’” (Sibbet, 1997: 3). Graphic facilitation involves visualizing concepts and discussions for groups, often in real time, through combinations of words and images; it is an iterative process requiring dialogue, cartooning, and collaboration (Mendonça, 2021). It is used within teaching and learning, public engagement, organizational development and co-production, as well as in research design, analysis, and dissemination (Mendonça, 2016). It can result in powerful insights, innovation, and “explicit group memory” (Ball, 1998) and raises significant ethical issues (Mendonça, 2019b). While drawing and writing are important here, enabling, structuring, and responding to challenging conversations also requires contextual knowledge and skillful facilitation. Many choose to separate the role of visual facilitator, who facilitates and interacts directly with people while developing visuals, from that of visual recorder, sketch-noter, info-doodler, or scribe, who may listen and record without interaction (Sibbet, 2002; Brown, 2014; Agerbeck et al., 2016). Within longer-term projects that connect and cross-pollinate, and within work that involves representing complex systems, relationships, subjects, and concepts with significant levels of engagement, these distinctions can become less obvious.

Values-based cartooning may include graphic facilitation or recording at an event (virtually or in person), but also involves more traditional ways of working outside of meetings. It is a collaborative, social practice that requires interaction, including with those who have multiple perspectives and lived experience of the topics, systems, communities, and organizations being represented. It involves a process of checking back and developing visuals that aim to stimulate further discussion. Values, both shared and conflicting, influence the visual practitioner’s decisions about subject, purpose, role, process, and participation, along with who and what is represented. How, when, where, and indeed whether the work is shared are also taken into consideration. It is a mode of working that requires the negotiation of ethical concerns and conflicting agendas, and engaging with powerful emotions.

Values-based cartooning is underpinned by six principles: openness and clarity of purpose; self-awareness; listening, observing, and emotional engagement; contextual knowledge; representing diverse experiences; and critical thinking. It requires an engagement with the nuances of power and privilege, along with a commitment to asset-based approaches and strengths-based representations. This means asking questions about whose voices and images are included or excluded; whether, when, and where to represent negative perspectives and experiences; and whether what was observed and heard is in fact “true,” “accurate,” or “good.” Importantly, there is also a question about the practitioner’s (and the commissioner’s) own values and knowledge, and how these influence what is likely to be heard, understood, valued, or ignored. For example, what might it mean for a visual facilitator to record keynote presentations while missing a challenge made by a participant who holds very little power within a particular context? And what is an individual practitioner prepared to “say” in their own hand? What is the significance of choosing to include comments made during the tea break, posted on social media, or hastily added to the “chat” during a Zoom or Teams meeting? Or choosing to omit a perspective considered offensive or inaccurate? Is it acceptable for the visual practitioner to ask questions, invite comments from someone who hasn’t yet contributed, to challenge the process or dominant line of argument? Values-based cartooning can be a powerful and engaging tool for teaching and learning as it requires critical thinking skills, listening and observing, analyzing, selecting, deconstructing, and reconstructing, conceptually as well as visually. The extent to which it may connect with or differ from approaches to values-based education (Hawkes, 2006; Biesta, 2010) and values-based leadership (Busch and Murdoch, 2014) may be worthy of further investigation. Before discussing selected examples of visual practice, a note about the representation of women’s leadership in education.

The lack of representation of women, particularly women of color, in formal leadership roles across education is an ongoing concern (Mirza, 2008; Fuller, 2017; Miller and Callender, 2018; Manfredi et al., 2019). Improving the visibility of women’s leadership, in education and beyond, is one way that visual practitioners can highlight the contributions made by, and the barriers facing, women and seek to counter depictions that exclude, undermine, objectify, and misrepresent. However, being a leader with increased visibility comes at a cost for many women, including the risk of high levels of abuse (Gorrell et al., 2018; Rheault et al., 2019; Spring and Webster, 2019). This can be seen in the experience of the 2019 Secretary of State for Education, Nicky Morgan, who spoke out about the increase in and extremity of abuse and threat over recent years (Scott, 2019); MP Diane Abbott, who received “almost half of all the abusive tweets sent to female MPs in the run-up to the general election,” including hundreds of racist letters a day (Elgot, 2017); and also in the case of Jo Cox, MP for Batley and Spen and a campaigner for education equality and improving support for children with autism, who was killed in 2016 by a White supremacist (Jones, 2019).

Those in the business of developing and commissioning visual approaches may have conflicting views about what kinds of images and stories of women’s leadership are needed right now. Overly negative portrayals can undermine achievement and progression and discourage aspiration and ambition in others. And rarely do images of women’s leadership include the sleep-deprived, menopausal headteacher trying to juggle an unexpected childcare crisis with an unannounced OFSTED inspection. Understandably, there is significant demand for positive representations and quotations that celebrate women overcoming barriers, bravely leaning in or leaning out, speaking out, and achieving success. Social media feeds off photographs of glamorous, youthful, slim, sporty, and exceptionally happy-looking women reaching the summits of mountains, along with beautifully stylized illustrations of contemporary women, occasionally using very old-fashioned looking wheelchairs. These images may be aesthetically pleasing and representative of some marginalized communities and cultures, yet they still require critical attention and raise questions about purpose, message, and audience. In the field of comics scholarship, Martin Barker (1989) has argued that, while drawing conveys identity, when people read a story, they relate to the way a character behaves not simply how they are drawn. This is a useful challenge to those attempting to create and commission visual work that seeks to disrupt dominant narratives, engage with nuance and complexity, address gaps, highlight inequalities, and inspire change. An illustration recently commissioned by the United Kingdom government for a Covid-19 lockdown social media advertisement drew widespread criticism for stereotyping women during the pandemic by depicting women (including at least one drawn with brown skin) cleaning, ironing, home-schooling, and looking after children, while a man sat on the sofa. The illustration also includes a girl holding a broom. It could be argued that the image accurately reflects the situation facing many women who have lost their jobs during the pandemic and/or continue to undertake the majority of work associated with raising children. However, given the lack of any visual or textual critique of the scenes depicted, the illustration simply reinforces a sexist, unimaginative, and unhelpful narrative about gender roles. In response to the image, Mandu Reid, leader of the Women’s Equality Party, said, “The government needs home-schooling on the impossible realities of Covid parenting, otherwise it will be more than their artwork that is stuck in the 1950s” (Topping, 2021).

Illustrations that include anonymous characters with different skin tones, clothing, and hairstyles may go some way to addressing under- and misrepresentation, but how useful are these images if women’s leadership, creativity, views, and agency are absent, and the challenges women continue to face remain hidden? Here I include, for example, the experience of negotiating motherhood, caring responsibilities, and career progression (O’Reilly, 2010; Castaneda and Isgro, 2013; Marsh, 2019); issues around disclosing disabilities and chronic illnesses (Brown and Leigh, 2020); and the stress and mental-health needs associated with leadership roles, as described by Viv Grant (2015) and Alison Kriel (2018), both of whom promote staff and student well-being within their consultancy work. It is crucial we find ways to fund and develop more nuanced visual and textual strengths-based representations that demonstrate not only women’s agency and accomplishments but also the diversity of their opinions, contexts, backgrounds, and experiences, and their perceptions of risk, failure, loss, and learning.

Leaders in education whom I have represented over the years include pioneering teacher and writer Beryl Gilroy (1924–2001), HM Chief Inspector of Education Amanda Spielman, and learning-disabled actor, director, and poet Ellen Goodey. However, the educators currently being discussed in our home include Mrs Rees from Class 10 and three fictional characters: Roshni Singh, the Gobleian librarian and skillful giant-bug fighter in Hollowpox: The Hunt for Morrigan Crow (Townsend, 2020); Miss Hardbroom, the fierce deputy head and potions teacher in the recent television adaptation of The Worst Witch, played by Raquel Cassidy; and Tala (voiced by Rachel House) in Moana, the protagonist’s indigenous grandmother who teaches her people’s history and transforms into a whaitere (enchanted stingray) upon her death. Such examples of women’s leadership may be less well known to adults but of great significance to children. Jessica Townsend’s work, for example, enables conversations with children about contemporary issues such as immigration, racism, discrimination, exclusion, and leadership during a pandemic. Fictional characters and narratives are of particular interest here due to the cultural referencing, intertextuality, anonymizing, and fictionalizing present within values-based cartooning, enabling innovative approaches to participant engagement and visual storytelling within research, education, and campaigning. The following describes three approaches where values-based cartooning has resulted in representations of women’s leadership in education.

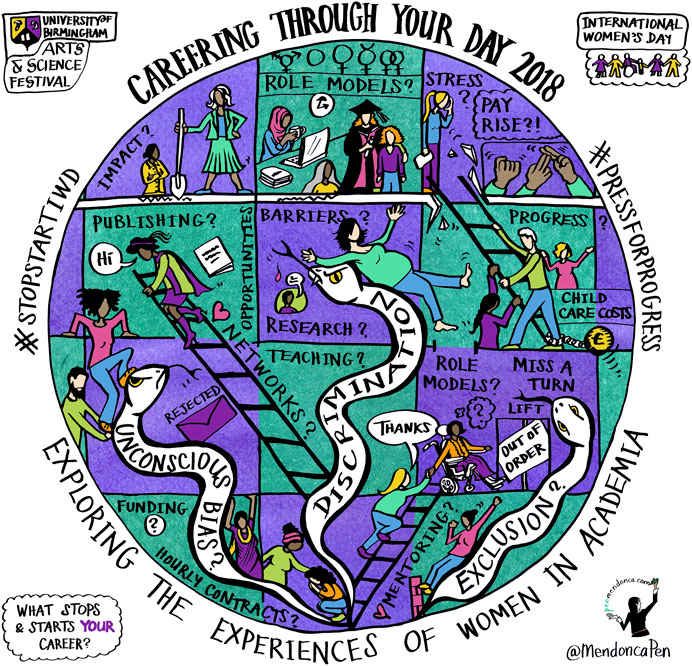

In 2018, alongside Professor Jo Duberley and Equality and Diversity Advisor Sheena Griffiths, I undertook research into the experiences of women working and studying at the University of Birmingham. We began with a conversation about the values and knowledge underpinning the project (see Ledwith and Manfredi, 2000; Manfredi et al., 2019). Figure 1 was included within festival promotions, posted on social media, and displayed across the university in order to build interest in the project. It was then used to stimulate discussion within nine graphically facilitated sessions. Participants were invited to critique and deconstruct the image, and then to create their own, which in turn informed the research. Here my identity, approach, and independent status influenced the nature and level of participant engagement. One participant, Lorraine Mighty, English for Academic Purposes Program Manager, described how values-based cartooning “created a safe and equitable space where all voices were valued and graphically represented with care” (although all methods have limitations, and some people simply choose not to engage). An Athena SWAN meeting and an International Women’s Day event featuring Professor Kalwant Bhopal and Dr. Sarah Aiston were also graphically recorded. The one hundred participants, mostly women, included the university’s BAME Women’s Network, students, post-docs, professional services staff, lecturers, researchers, professors, and managers.

FIGURE 1. Careering Through Your Day 2018: Exploring the Experiences of Women in Academia. Pen Mendonça. 2018.

Experiences were initially framed within conversations about games: snakes and ladders, mazes, and kaleidoscopes. Questions were raised about the ladder as a metaphor for careers; some spoke of the rules changing as your career progressed, of not being able or not being able to afford to play the game, of being dealt the wrong cards, or being on an uneven playing field. Narratives included micro-aggression, pregnancy discrimination, motherhood, delayed motherhood and non-motherhood, the impact of being less mobile or of going part-time on academic career progression, and leadership across multiple institutions and countries. This led to deeper discussion about agency and structures, intersectionality, mentoring, networking, and flexible working.

Jo, Sheena, and I used the graphics to undertake analysis, identifying themes and solutions relating to recruitment, retention, targeted support, resource allocation, and individual behavior. A visual summary and joint presentations then stimulated further conversation at a subsequent event for all participants and interested parties. Graphics were then included and contextualized on the university’s website (birmingham.ac.uk) and displayed in large scale at the Careering Through Your Day exhibition. This work was then used to build a successful bid for an AdvanceHE grant for the project “Drawing it out: Using values-based cartooning to explore and address racial micro-aggression in HE.”

This formally commissioned work with the University of Birmingham recognized values-based cartooning as a research method worthy of investment and critical examination. I, the visual practitioner, was involved from the outset as the project was conceived and as its values, purpose, and design were agreed. I facilitated and recorded each session and exhibited and co-presented the research. The visual process and outputs were interrogated rather than simply accepted; the graphics had value well beyond providing illustration for a conference, an article, a tweet, or a website. To this day they are still displayed on office walls, in classrooms, on websites, as screen savers, and curated within articles like this. In a sense they have taken on a life of their own as they continue to stimulate discussion about gender equality in higher education and to invite critique within new contexts.

Between 2016 and 2018, Dame Alison Peacock and Julie Lilly commissioned me to graphically record a series of regional and national @BeyondLevels #LearningFirst events (Mendonça, 2016). While women leaders such as Professor Sam Twiselton and Mary Myatt were drawn and named, the main focus of my role was to depict concepts and concerns. Arguably Peacock and Lilly’s leadership was represented within all of the graphics I developed, even where their names and images were absent; within visual practice a title, hashtag, logo, symbol, color, or image may be all that is needed to link content to a leader, team, organization, or community.

#WomenEd began in England in 2015, connecting, supporting, and empowering women in education. Now led by a team of seven strategic leaders—Jules Daulby, Keziah Featherstone, Liz Free, Lisa Hannay, Natasha Hilton, Parmjeet Plummer, and Vivienne Porritt—#WomenEd has a community of nearly thirty thousand people in twenty-eight networks and across eighteen countries. Since 2016, #WomenEd has informally embraced and formally commissioned graphic recording within its work, including a graphic in 2017 that summarized the eight values underpinning this work, which has since been widely shared on social media, within presentations, and on websites. This includes elements separated out from large-scale graphics. It is worth reiterating here that my work is regularly published in fragmented or unfinished form.

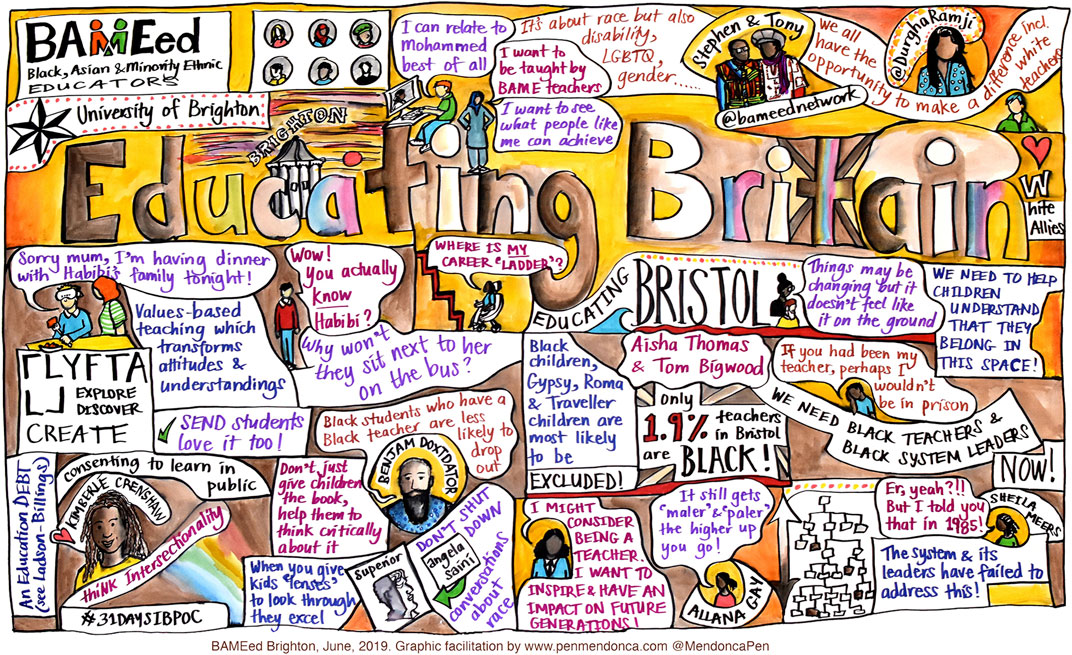

Since #WomenEd began, a number of new, connected movements have emerged, including LGBTed, MaternityCPD, DisabilityEd, DiverseEd, and the BAMEed (Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic Educators) Network. The latter was founded by Allana Gay, Amjad Ali, and Penny Rabiger and is described as “a movement initiated in response to the continual call for intersectionality and diversity in the education sector” (BAMEed Network, 2020). At an early BAMEed conference in Bolton in 2017, I recorded a keynote by pioneering health expert and educator Professor Dame Elizabeth Anionwu. Following this, my BAMEed graphics increasingly included caricatures of conference participants alongside speakers, acknowledging multiple perspectives and leadership across all levels of the formal education system. Intentionally expanding the focus beyond those who delivered keynote presentations reflects the inclusive nature of the events and invites interaction and collaboration with participants. Figure 2, from a 2019 conference, includes three named speakers, three named participants, a well-known academic who was referenced during a presentation (Kimberlé Crenshaw), and two individuals who featured on videos shown at the event. In addition, fifteen fictional characters illustrate and express ideas that were discussed during the event. Participants at BAMEed events in particular tend to take photographs and selfies in front of the graphics, sharing them with friends and colleagues across multiple platforms. All too often participants, speakers, and readers claim, “you never get to see that.”

FIGURE 2. Educating Britain. BAMEed: Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic Educators. Large-scale graphic developed live at the BAMEed conference, University of Brighton. Pen Mendonça. 2019.

This graphic provides a record of perspectives, observations, workings-out, connections, and interactions at a particular point in time, which may not exist elsewhere. As I write this article, I notice a mistake in the bottom left corner, next to rainbow stripes intentionally painted between sections of brown. “#31DAYSIBPOC” should read “#31DAYSBIPOC” (BIPOC is an abbreviation for Black Indigenous People of Color). The typo here serves as a reminder of the speed and pressure under which this image was developed, completed, and shared. This kind of work is largely unbriefed and results in a mix of visual outputs heavily influenced by the different contexts and conditions in which they were produced. Operating outside of properly funded, branded visual communication strategies clearly has drawbacks, yet this organic and iterative approach allows creative space for practitioners, leaders, and participants to shape visuals in the moment, resulting in dynamic, responsive work that has helped to promote grassroots initiatives; to explore and communicate their values, aims, energy, and color; and to highlight important forms of leadership. The work discussed above includes unpaid as well as paid commissions—sporadic, informal collaborations with women and others, many of whom voluntarily lead initiatives in addition to the formal senior leadership roles they hold within the field of education. The following explores campaigns with educational aims that exist outside of the formal education system, where women’s leadership also thrives.

Griselda Pollock (2013: xxvii) asks, “If a child is taken into a museum to learn about either its heritage or what is deemed the cultural heritage of the country in which the child is living and sees only valued representations of work by straight, white men, and only encounters representations of women and ethnic or sexual others in roles of servitude, domestic, rural or sexual, what sense of its own self does it internalize?” All too often institutions, including governments, schools, colleges, universities, and museums, fail to acknowledge diverse histories, leading us to a narrow, romanticized, and inaccurate reflection of the rich, colorful, complicated, at times punishing world we live in. The damage mis- and underrepresentation causes affects all of us. This was highlighted by pioneering Black British publisher Verna Wilkins at the University of Newcastle conference “Diverse voices? Curating a national history of children’s books,” held in 2017 (Pearson et al., 2019). More recently, Baroness Lola Young (2020) has reminded us that “Bringing into the open those uncomfortable stories that don’t fit neatly into the dominant historical narrative is still a struggle; ‘invisible’ histories are frequently banished to the margins, their heroes and pioneers relegated to footnotes.” Values-based cartooning offers one approach that practitioners, artists, researchers, and commissioners can use to try and address this.

Resistance, campaigns, and activism have always existed, but their history is rarely taught. The extraordinary work that has been undertaken within and outside of the education system to try to address the narrow focus of the curriculum is too extensive and diverse to cover within this piece. Olivette Otele (2020) provides powerful arguments for the teaching of resistance: “Integrating stories [of Black resistance] in primary and secondary curriculums would allow most young Britons and their parents to understand that people of African descent were instrumental in achieving their own liberation. It would also demonstrate how collaborations between these communities and activists from different backgrounds worked, evolved and brought about positive change.” The following campaigns sought to educate as well as influence policy (including educational policy), and to celebrate and highlight the contributions that women and others from racially minoritized groups have made to British society, in spite of racist and patriarchal structures and attitudes.

Activism often requires a quick response as political landscapes change; as language, approaches, and priorities evolve; as partners join or leave. Where those involved are working together informally and under pressure, there is rarely time for meeting face-to-face; for shaping a long-term, well-paced, properly funded visual communication strategy; or for briefing, checking, redrafting, or reflecting on artwork. Some of the work that follows was developed on scraps of recycled paper with children’s art materials while on the phone; it was shared in-between heating up spaghetti hoops, writing a PhD, and making enough money to pay the rent. The next three examples, South Asian Heritage Month UK, Banknotes of Colour, and 100 Great Black Britons, are connected through shared values and leadership. They exist within a long and dynamic narrative of challenge, which includes the work of organizations such as the Black Cultural Archives, the Runnymede Trust, and the Mary Seacole Trust, but also that of individual teachers, teaching assistants, leaders, networks, independent consultants, and campaigners. Within the work that follows, I am making connections between different contexts and campaigns, noticing opportunities and synergies, as well as gaps, absences, differences in approaches, and priorities. Here, I had a different relationship with my colleagues: I was part of a team of people, contributing what we could within our limited time and with limited resources. Values-based cartooning here was undertaken as an artist seeking to make a personal contribution, rather than as a visual practitioner working to a commission.

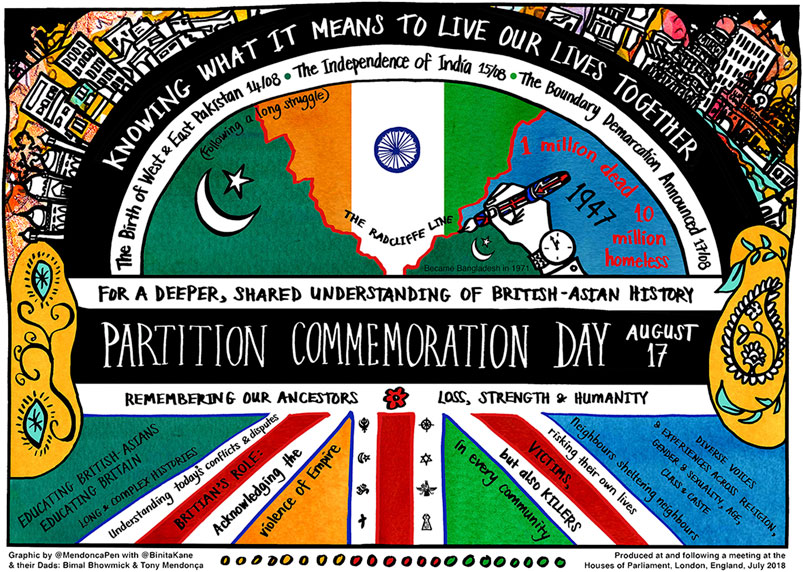

The Partition Commemoration Project and Britain’s South Asian Heritage Month (co-founded by Dr. Binita Kane and Jasvir Singh OBE in 2019) consider the 1947 partition of British India and the birth of Pakistan (and later Bangladesh) to be one of the most important historical events of the twentieth century, shaping much of modern-day multicultural Britain (Asian Today, 2019). The graphic in Figure 3 seeks to acknowledge the extent of the accompanying displacement, violence, loss, and trauma—and Britain’s role within this, including the hastily drawn Radcliffe Line (represented here with a white hand wearing a watch and holding a Union Jack pen). Here, in the words of the graphic itself, we acknowledge the experience of “neighbors sheltering neighbors, risking their own lives. Victims, but also killers, in every community.” This kind of challenging, contemporary, interfaith work—which brings together diverse voices, experiences, family histories, and values across religion, gender, sexuality, age, class, and caste boundaries—is crucial in that it celebrates the lives of British Asians while also confronting over-simplistic, inaccurate, politically convenient views of the past and the way these views shape our understanding of the present and our relationships, attitudes, and actions.

FIGURE 3. Partition Commemoration Day, 22 August. Developed by Pen Mendonça and Binita Kane, with their dads, Tony Mendonça and Bimal Bhowmick. 2018.

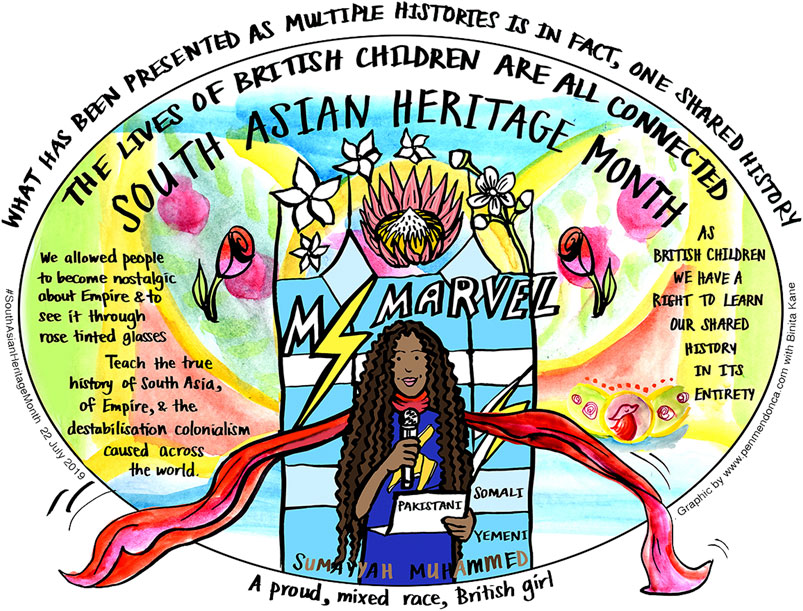

At the parliamentary launch of South Asian Heritage Month, speakers from a spectrum of communities made contributions, including educator Dr. Priya Atwal, who raised concerns about young people’s knowledge of and interest in studying this history. Student Sumayyah Muhammed, age twelve, reminded us of the leadership that exists in the next generation. Despite the diversity and achievement of the leaders speaking at this event, I chose to only depict Sumayyah. In Figure 4, she is surrounded by statements from her extraordinary presentation along with flowers from each of the countries of her mixed heritage and colors borrowed from the visual identity of the campaign, designed by Rooful Ali. She has been playfully dressed like Kamala Khan (a sixteen-year-old, middle-class, Muslim, Pakistani-American comic-book character who is/becomes a superhero called Ms. Marvel) because of her love of the Ms. Marvel comics (created by G Willow Wilson and Adrian Alphona). Sumayyah’s critique of colonialism and structural racism is arguably more complex than some of Ms. Marvel’s early storylines, which may at times have reinforced stereotypes while attempting to subvert them (Berlatsky, 2015).

FIGURE 4. South Asian History Month: The Lives of British Children Are All Connected. Words by Sumayyah Muhammed. Pen Mendonça. 2019.

Sumayyah identifies as a proud, mixed-race British girl of Pakistani, Somali, and Yemeni descent, a fan of comics with a critical eye on the presentation of global and British histories. She does not allow me to fix her within a convenient stereotype of a young British Asian. Yet values-based cartooning, by its nature, often requires slipping into the messy and dangerous world of stereotyping, as the artist attempts to make characters and concepts recognizable, while also seeking to communicate strengths, agency, context, and inequalities. As Pitcher (2014: 41) suggests, “The acceptance of the necessity of stereotyping is a useful way of thinking about the terms of encounter with cultural difference. … While the stereotype never really ‘belonged’ to the other group, the process of engagement can help to make this apparent to us.” It could be argued that aspects of the work shared here risk reinforcing negative stereotypes and/or oversimplifying complex identities and ideas about gender, race, and leadership. Celebrated cartoonist Will Eisner (1996: 17), whose approach to the representation of women can be highly problematic, frames the stereotype as “an accursed necessity.” Engaging with rather than simply avoiding a stereotype can be useful for cartoonists, who are required to know about stereotypes if they wish to represent or subvert them. In his discussion of the assessment of racial caricature within South African comic and satirical art, Andy Mason (2015: 53) points out that acceptability will depend on intention, context, and the attitudes of readers: “Whether [racial caricature] can function as a locale of positive representation, is a question that evades generalisation, to be reconsidered in each instance it is encountered.” Through the graphic of Sumayyah, values-based cartooning enabled me as an artist to celebrate the glorious complexity of mixed-heritage identities and global family stories, with their inevitable mysteries, shared and conflicting perspectives, heroes and antiheroes. Whether, and how, others will read this graphic, will largely depend on their reading and/or esthetic preferences, along with their own understanding of British, Asian, and world histories.

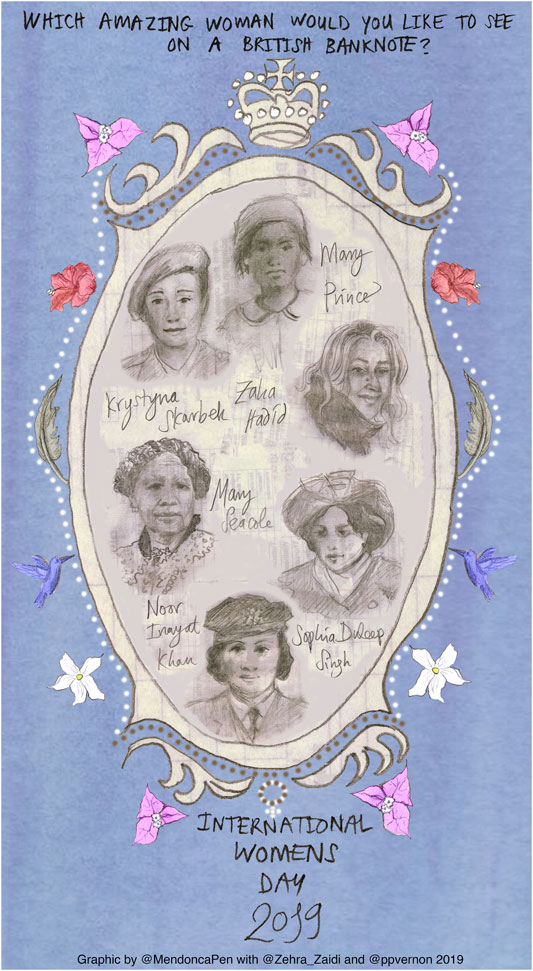

The second example involves a campaign to address the lack of representation of racially minoritized leaders on British banknotes. In 2018, the Bank of England invited the public to nominate historical figures to be included on the new £50 note. Of the 989 “eligible” nominations, only one percent were from racially minoritized groups (Zaidi, 2019), which raised questions about the nature and accessibility of the nomination process as well as of public understanding of British and world history. By mid-2019, 130,000 people had signed a petition to have Mary Seacole featured on the new £50 banknote, and 15,000 had signed a petition for British Muslim war heroine Noor Inayat Khan, who was posthumously awarded the George Cross in 1949, to be on the banknote.

As the pressure mounted on the Bank of England from multiple lobby groups, Zehra Zaidi (lawyer, activist, and founder of We Too Built Britain) and Dr. Patrick Vernon OBE (social commentator, campaigner, and cultural historian) joined forces to lead the Banknotes of Colour campaign, which aimed to highlight the positive contribution that different racially minoritized individuals have made to Britain. This partnership represented a coming together of British Asian and Black British campaigns from different parts of the political spectrum. Over the course of the campaign, potential candidates were discussed and debated on Twitter, on television, in dining rooms, and in classrooms; 220 leaders and celebrities signed a letter in The Times, 100 cross-party politicians wrote to the Governor of the Bank of England, and MP Helen Grant presented a Private Member’s Bill in Parliament. My Banknotes of Colour graphics, including one produced for International Women’s Day 2019 (Figure 5), were shared on social media, included within blogs, published as part of petitions running in the Metro, and appeared in The Guardian alongside an article by Afua Hirsch (2019). In June 2019, it was announced that the extraordinary mathematician Alan Turing, prosecuted for his homosexuality in the 1950s, was to feature on the new £50 note. In response to the campaigns above, the Royal Mint released a new 50p coin engraved with “Diversity Built Britain” during Black History Month UK (Gov.uk., 2020). The Art Newspaper recognized the role of both women’s leadership and cartooning within the Banknotes of Colour campaign (Harris, 2020a), however, in 2021 there remains no representation of any leading historical figure from a non-White background on British legal tender, and a significant lack of women.

FIGURE 5. Which Amazing Woman Would You Like to See on a British Banknote? Graphic developed for the Banknotes of Colour campaign. Drawn with a child’s pencil on the back of a booking form for an after-school club. Pen Mendonça. 2019.

The killing of George Floyd by a White policeman in the United States in May 2020 led to more than 200,000 people protesting across Britain in the name of Black Lives Matter, and to a renewed interest in anti-racist work. The final example included here is the 100 Great Black Britons campaign. In 2002, the British public voted for their top one hundred Great Britons. Out of a total of one hundred nominations only thirteen women were put forward, and these included the Queen and the late Queen Mother (Wells, 2002). In response to the predominantly White list, and particularly to the absence of Black women, Drs. Angelina Osborne and Patrick Vernon launched 100 Great Black Britons, with British-Jamaican nurse and businesswoman Mary Seacole (1805–1881) being voted number one in 2004. Seventeen years later, against the backdrop of the rise of far-right ideologies, extremism, the “hostile environment” policy, and Brexit, Osborne and Vernon relaunched the campaign and schools’ competition. As part of this I developed and shared dozens of images for the campaign, graphically recorded the selection panel meeting, and eventually drew each of the one hundred leaders selected into a single image (Figure 6), which has been shared widely on social media and reproduced as a poster. The articles, television interviews, school lessons, assemblies, conversations, and imagery generated as part of this campaign prompted celebration and passionate debate, highlighting less well-known names and histories. The book 100 Great Black Britons (Vernon and Osborne, 2020) was launched during Black History Month. At the time of writing, well over a thousand schools have participated in the schools’ competition.

FIGURE 6. 100 Great Black Britons. Pen Mendonça. Drawn with help from Tony, Gill, and Autumn Mendonça. 2020.

Osborne is an independent researcher and heritage consultant with an interest in enslavement and proslavery discourses, and in the history of community and education activism. She is, of course, a leader in education, as is Yvonne Davis, the retired headteacher leading the campaign to get the 100 Great Black Britons book and poster (Figure 6) into every secondary school in England (Boyce, 2020). I have yet to draw either of these women, yet through values-based cartooning, and writing about practice, I am able to credit and represent their extraordinary leadership.

Campaigns, initiatives, and movements such as these exist outside of the national curriculum, yet inevitably find their way into classrooms, staffrooms, offices, board rooms, and policy discussions. Leading and supporting them involves enormous dedication and unpaid work over years, decades, even lifetimes, often building on and benefiting from what previous generations have done. Examples of this are evident within intertextual visual practices, for example, my work with the Windrush Generation (Harris, 2020b) and the Majonzi Fund (majonzi-fund.com) sometimes makes visual reference to the pioneering graphic design of the late British Caribbean creative Jon Daniels. Leaders may find support from our institutions and communities, or may be undermined, ignored, and discriminated against by those with privilege and power. They may be forgotten, denied credit for their achievements, exposed to bullying, or subject to abuse from those who oppose their campaigns. At an event for the Leo Academies Trust (online due to the pandemic), I took a long time completing my drawing of the late Jo Cox and her sister Kim Leadbeater, whose inspirational leadership since Jo’s death has led to fragmented communities coming together across the country. In their home town of Batley, I captured the diverse voices of young women as they call for all children to be taught about misogyny, and for everyone to stop underestimating girls (see the #RealPeopleHonestTalk event led by Near Neighbors Co-ordinator at Wellsprings Together, Kaneez Khan). Time and time again I listen as talented, deeply committed women leaders warn about the failures of the criminal justice system, the impact of disparity, discrimination, austerity, school exclusions, and social isolation, and I observe the way they generously offer solutions, innovating both within and outside of formal educational settings. But as I reflect on the representation of women’s leadership in education, I am also aware of the need to depict the sexism, racism, ableism, and ageism that continue to stifle and control it. I consider the impact of risk, threat, and abuse on women’s agency and leadership. I think about the serious harm and pain patriarchal structures and violence continue to cause women and girls, LGBTQ+ young people and adults, men and boys. As I write this article, an exhibition celebrating 100 Great Black Britons has been vandalized (Thorburn, 2020). Images, including of Mary Seacole, have been sprayed with black paint. Their faces are no longer visible; a kind of visual violence has occurred, a hate crime. The photographs that document this vandalism tell us a different story of Britain, one that those leading these campaigns today and throughout history have been acutely aware of.

Our bodies, lives, and leadership have always been subject to problematic depictions, undermined within objectified and sexualized imagery, or limited to the maternal or socially approved. While we now see more diverse positive representations of gender and race (particularly following the death of George Floyd), many gaps remain. This includes portrayals of the leadership by women impacted by Britain’s hostile environment policy (Gentleman, 2019), such as members of the Windrush Generation and their families, refugees, asylum seekers, and undocumented migrants, many of whom have not been able to exercise their human rights or access healthcare, information, support, or safe spaces during the pandemic. In England, images and stories of older people as care home residents have dominated the news; all too often we see limiting representations that undermine their experiences as pioneers, leaders, artists, and thinkers who helped to shape the world we live in today. There remains a distinct lack of visual stories about women and non-binary leaders of all backgrounds, who may be aging, unwell, may have visibly disabled bodies, invisible disabilities, learning disabilities, illnesses and health conditions, fat bodies, muscular bodies, mothering bodies, mental-health needs, learning disabilities, or even just “bad hair.” These gaps are noticeable within mainstream cartooning and illustration, where child-like, conventionally attractive, and stretch-mark free representations of adult women remain overwhelmingly popular with both publishers and readers. At times the perceived need to promote “progressive” or “appealing” images of women has the unintended consequence of reducing the visibility of the everyday, whether joyful, hopeful, healthy, humorous, mundane, frustrating, isolating, traumatic, or exhausting—the very aspects of women’s experience that bring into focus both the true nature of our lives, relationships, and jobs and the structural inequalities that impact on our agency and well-being. However, the field of comics and graphic novels offers alternative stories and approaches, many developed by women and LGBTQ+ creators, some of whom have self-published. Comics scholarship and interdisciplinary research provide conceptual frameworks for understanding this kind of work.

As we have seen, there is at times a tension between an organization’s desire to increase positive representations of marginalized groups and the need to reflect the current situation in order for it to be understood and addressed. Visual practitioners, and those commissioning or collaborating with them, can find themselves caught in this dilemma. Our attempts at increasing visibility may unintentionally serve to reinforce existing structures and behaviors. The current desire for organizations to celebrate and promote diversity (which is regularly assumed to be an inherently positive act) can result in misleading visual representations of participation and leadership. I call this the “diversity gloss,” a layer of engaging visual/textual material that enhances image and reputation in relation to diversity, inclusion, and equality, perhaps exaggerating the real picture, masking enduring gaps and problems, and potentially further marginalizing those who experience discrimination, who struggle to be heard, seen, respected, supported, included, employed, or promoted.

There can be a temptation to make statements about the kind of drawing style or approach to representation that apparently works, or doesn’t, that is acceptable, recognizable, or not. Such assumptions can lack evidence and reflect our own histories and preferences as readers and audiences. The report Reflecting Realities (Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE), 2020) rejected the style of illustration where characters’ faces are featureless in its vital and informative study of ethnic representation within children’s books. The suggestion was that “The nature of such an illustration style creates a homogeneity that eliminates the ability to categorise ethnicity. Such a choice undermines the validity of the submitted title in terms of it being recognised as an example of representative and inclusive literature, particularly if such a portrayal is the only indicator of ethnic minority presence in the book” (21). This view relates to the complex nature of evaluating ethnic representation within children’s books. The work included in this article is not designed for a children’s book; it offers a different kind of narrative and often integrates figures with other imagery and text that adds context, narrative, and voice. However, the CLPE report is of interest here as much of my practice, which includes collaborations with children and educators, contains characters with featureless faces. I note that my own ethnicity, and that of many of my family members, friends, and colleagues, can be difficult to categorize, attracting that curious, unsettling stare, the disbelieving tilt of the head, and direct verbal challenge as people try desperately to marry the identity you claim with the ethnicity they “read” within your face, your skin, your hair, clothing, language or accent, your name, taste, or way of life. Here they draw on their own cultural vocabulary and values, their experiences and understandings of world and family histories.

Developing criteria for the purposes of research is always challenging, requiring a process of selection and rejection, and at times masking important contextual considerations, changing meanings, and trends. Where such criteria are interpretated as recommendations, they may have the unintended consequence of limiting experimentation and creative expression. I would question the assertion that stories that involve characters with featureless faces as a tool for ethnic representation should not be recognized as a possible example of representative and inclusive literature, particularly as readers draw on their own rich cultural and visual vocabularies, which today are very likely to include cartoons, comics, and animation. Within my work with communities, schools, and clubs, children and young people regularly contribute to visuals by drawing and writing alongside me, often adding characters and narratives from popular animations, symbols and designs from their cultural vocabulary, mimicking and adapting my drawing style in order to add their own meaning, story, and voice to the graphic.

Google “visual or graphic facilitation or recording” and you will find examples of stunning artwork, however, you will also see repetition after repetition of commonly used icons and page layouts, generic cartooning styles, and marks made onto white canvases with the same pens and software programs. While having a number of commonly used visuals is helpful to both visual practitioners and audiences, it is worth questioning the value of replicating standardized imagery and designs across very different contexts and content. Drawing only on existing approaches and recommended icons comes with risk. Much like the process of selecting words for a dictionary, as beautifully described in The Dictionary of Lost Words by Williams (2020), such recommendations are subjective rather than neutral or necessarily transferrable. Visual practice must constantly adapt and evolve if it is to be relevant. Leadership through visual practice requires looking beyond the recommended icons and approaches; even when such work may appear successful, fashionable, and profitable, it requires adaptation, taking risks, making mistakes, being open to new learning, research, and collaboration—developing and connecting ideas, initiatives, words, and imagery in new ways that reflect our diverse and changing world.

My independent visual practice has been used and celebrated across multiple communities and organizations; however, it has also attracted sharp criticism over the years from some design educators and leaders in the field of illustration. This work, which is about writing and facilitation as much as it is about drawing, is made first and foremost for the leaders, participants, and communities I collaborate with. It is them to whom I am accountable; whether the graphics meet the criteria for an illustration prize or win the praise of design critics is of less importance. The drawing and writing style, tone, content, and symbolism developed over my career represent intentional attempts at realigning the concept of leadership with less masculine, less White, and less corporate-looking imagery, color, language, and line. I connect word, lettering, color, and image, seeking to provide new meaning within a wider portfolio. I replace straight lines with thrilling curves, neat boxes with waves of overlapping—at times contradictory—statements. I enhance white canvases with gorgeous shades of brown, and wallow in the pure joy that comes with scribbling dark letters, allowing grey-blue shadows to merge into flowering vines. These visuals include Persian paisley, Arraiolos rugs, Maasai shuka, Ghanaian Kente, Heer Bharat embroidery, fedora hats, and second-hand Swandri shirts. Inspiration comes from many places—a dress worn by a participant, a story, a call to action, a debate, poem, or song. For some this mix of styles and ideas is liberating, inclusive, accessible, nuanced, and scholarly, for others my work seems chaotic, confusing, text-heavy, ugly, and distracting—an unnecessary assault on the fundamental, traditionally accepted Western “rules” of graphic design.

Like so many of my colleagues across the globe, I deconstruct and reconstruct, experiment, find my own way to understand, analyze, question, and communicate through visual practice. This is an incredibly exciting field to be part of as visual practitioners and artists work in new contexts and new talents from increasingly diverse backgrounds challenge, deepen, and develop visual practice, drawing on contemporary and traditional influences. Visual practitioners around the globe are speaking about their work, writing critically about practice, teaching and mentoring others, sharing insights (see ifvp.org for example). Many women and LGBTQ+ practitioners have significant experience of working within and alongside marginalized communities (see Bradd, 2019, on cultural safety) and a great deal to offer the world at this moment. Linda Tuhiwai Smith warns of “a dominant perspective that has assumed the right to tell the stories of the colonised and the oppressed [that they have] re-interpreted, re-presented, and re-told through their own lens” (Smith, 2019). Asking questions about who it is that gets to facilitate or record stories, when, and why, is an essential element of a values-based approach. In our enthusiasm to hear and amplify voices and to support change, it is important to consider both leadership and allyship through visual practice, and to find out what this means to those we connect with, so we can learn from and contribute to reciprocal relationships. As we have discussed, there are always ethical issues to consider, and as such it is necessary to develop a collaborative, inclusive, respectful approach, where practitioners and commissioners ask questions of themselves, reflect on purpose and impact, the limits of their knowledge, their visual, verbal, and handwritten language. The range of perspectives and experiences within any community or organization may complicate such processes, and can leave practitioners and commissioners with uncomfortable dilemmas. Collaboration and coproduction can help address this, particularly where independent artists and visual practitioners are afforded creative spaces in which they feel they can breathe, stretch, question, and innovative, so that new learning, partnerships, approaches, and opportunities can emerge.

Today, the pandemic is having a dramatic impact on migration and travel, on citizenship, our sense of belonging and identity, and our tendency toward othering, particularly in Covid-19-hit Brexit Britain, but also in less obvious, relatively Covid-safe places like Aotearoa New Zealand, where the “other” includes citizens who have tested positive for Covid-19 as well as citizens returning from countries significantly impacted by the pandemic. The lines I draw are riddled with influences and life experiences, some obvious, some not. These influences mean that there are certain lines that my mind will edit, that my hand simply will not draw or write. No matter how objective we seek to be, all visual practitioners’, artists’, researchers’, and writers’ work is both tainted and enhanced by the roads we have traveled, whether paved in Hokitika gold or obstructed by trolls. We select and highlight based on our values, motivations, experiences, levels of skill, contractual agreements, and need to survive financially, but selecting one idea or response also involves discarding others. We make mistakes, learn, change our minds, and develop our practice. Our lines may be visionary, promotional, critical, or crooked; they reflect the kind of collaborations we seek and/or are offered, the stories we research, choose, or are prepared to hear, see, read, or engage with emotionally. They expose the lenses we try to focus through and reveal the limits and wealth of our knowledge, relationships, and experiences. Being a researcher, a cartoonist, and a graphic facilitator requires a heightened awareness of one’s own subjectivities, whether in relation to accessing and representing stories, facilitating dialogue, negotiating verbal and visual communication, handwriting text, or making seemingly minute creative choices on the spur of the moment. High levels of creative decision-making bring into focus the responsibilities of the role. As historian David Olusoga (2020) has explained, “If your job is to tell stories, especially if your job is to tell other people’s stories, then examining your own thinking is absolutely critical.” Through values-based cartooning and other visual methods, we can explore these ideas further.