- 1David Yellin College of Education, Jerusalem, Israel

- 2The Mofet Institute, Tel-Aviv, Israel

- 3Achva Academic College, Arugot, Israel

- 4Beit Berl College, Kfar Saba, Israel

The current study deals with participation in inter-institutional Communities of Practice (CoP) (Wenger, 1998) as a form of professional learning for experienced teacher educators who hold leadership positions in their institutions. In these CoPs, collaboration between teacher educators and policymakers resulted in expansive learning, which is the creation of new practical and theoretical knowledge, and a change of practice rather than adoption of knowledge constructed elsewhere. The current study describes three such communities, the expansive learning cycles that each of them triggered, and shared characteristics that may have contributed to these outcomes. The multiple case study methodology was employed. Data sources were interviews with thirteen participants (coordinators, Ministry of Education representatives and additional members from each CoP), and documents (such as meeting minutes and research papers) that were produced in each CoP. The findings show that expansive learning occurred due to a shared vision, reflective and critical dialogue, trusting relationship, and mutual support among participants. Furthermore, the inter-institutional composition of the CoPs, and the influential position of the participants within their respective organizations enabled them to introduce coordinated changes that transformed their practice at the individual, organizational and national levels.

Introduction

Teacher education has significant influence on teachers’ quality (European Commission, 2013). Since most teacher educators acquire their profession in their practice (Goodwin et al., 2014), their in-service professional learning is crucial (Lunenberg et al., 2014; Vannassche et al., 2015). Teacher educators’ practice is embedded in narrow, as well as in wide contexts (Vannassche et al., 2015). Therefore, their professional learning is not only significant in the context of their individual practice, but also in the wider context of teacher education.

In many instances, the terms “professional learning” and “professional development” are interchangeable, but clear distinctions may be made between the two (MacPhail et al., 2014). Professional learning refers to informal learning opportunities such as informal conversations with colleagues that are part of the daily routine of the workplace, whereas professional development refers to more structured upskilling opportunities such as formal courses.

The current paper deals with one of the prevalent modes of teacher educators’ professionalization-participation in professional communities of practice (CoPs). These may take diverse forms such as Professional Learning Communities (cf. Avidov-Ungar, 2018; Hadar and Brody, 2018) or Communities of Research (cf. Willemse et al., 2016). Although CoPs are often organized by the workplace, the contents of learning are not determined in advance. Below, we will refer to CoPs as a form of professional learning.

Teacher educators’ CoPs have attracted some research, but their outcomes, as well as the relations between CoPs and their wider work contexts, have received scant attention in the literature (Hairon et al., 2017). One of the reasons for this lacuna could be the prevalent conceptualization of teacher educators’ professional learning as an individual or small group endeavor (Guberman et al., 2020). However, CoPs could be sites in which “expansive learning” is initiated and nurtured (Engeström and Sannino, 2010). Expansive learning is the construction of new practical and theoretical knowledge, and transformation of practices, as opposed to acquiring and implementing knowledge from external sources.

The current study deals with a unique type of CoP: inter-institutional CoPs (Wenger, 1998; Wenger-Trayner et al., 2015). In these CoPs, experienced teacher educators who hold leadership positions in their institutions collaborate with policymakers and other stakeholders. The current study describes the CoPs, the expansive learning that each one triggered: their novel conceptualizations and the changes they introduced, and indicates common characteristics that may have supported these outcomes. Such CoPs can contribute to the transformation of education at regional, as well at national levels.

Theoretical Background

Characteristics of Communities of Practice

A CoP is a group of professionals who meet on a regular basis to examine their professional knowledge and practice, aiming to improve these (Wenger, 1998; Wenger and Wenger-Trayner, 2015). CoPs may either consist of members sharing the same professional practice, or of those who have different professions but who share a domain of interest: “CoPs–not in the simple sense of having the same practices, but in the more complex sense of forming heterogeneous learning partnerships to transform existing practices” (Wenger-Trayner et al., 2015. p. 97).

CoPs differ from teams of professionals engaged in specific tasks, or staff meetings. Participants of CoPs are committed practitioners who enjoy professional discretion and view their membership as part of their professional identity and vision (Roberts, 2006; Stoll et al., 2006). That shared vision “ignites members” imagination’ (Wenger-Trayner et al., 2015, p. 106), encourages them to “step out of their comfort zones” (p. 116) and inspires their activities. To achieve their shared vision, CoP members focus on improving their professional practice. Their practice is the basis of discussions, and the forum in which conceptualization and new knowledge is created, applied and examined (Wenger, 1998; Stoll et al., 2006). CoP members share their practice with each other, engage in reflective discourse and receive honest and critical feedback (Andrews and Lewis, 2007). During discussions, implicit knowledge becomes explicit and is linked with knowledge from additional sources (Wenger, 1998; Stoll et al. 2006). Communication among CoP members is continuous and results in a quick dissemination of ideas, information, and innovations, as well as requests for help (Wenger, 1998; Stoll et al., 2006). Social interactions within CoPs are based on trust that is built over time. Successful CoPs manage to strike the balance between mutual support and trust on the one hand, and critical discussion of members’ practices on the other hand. Hierarchical power relationships within CoPs, as well as competitiveness and antagonism among members, prevent the development of trust and may ultimately harm the learning process (Thompson, 2005; Roberts, 2006). CoP members share common norms, values and working patterns. A repertoire of tools and products is an expression of the learning and the unique contribution of the CoPs and is one of the salient characteristics of their distinct entity (Wenger, 1998; Stoll et al., 2006). Nonetheless, there is a continuous flow of people and ideas in and out of CoPs. Wenger-Trayner and his colleagues (2015) believe that interaction and knowledge sharing with external parties and member turnover are natural and even desirable processes that prevent stagnation. However, sudden and significant changes in the number of participants, as well as a high turnover rate endanger CoPs’ existence (Thompson, 2005; Stoll et al., 2006).

In the 1990s, CoPs became one of the most recommended models for ongoing professional learning of educators. Professionals involved in CoPs can be teachers, teacher educators, school principals and other stakeholders (MacIver and Groginsky, 2011). Some communities operate out of one institution (Margolin, 2011; Hadar and Brody, 2018) whereas others are inter-institutional (Dickson and Mitchell, 2014). The current study focuses on inter-institutional CoPs comprised of teacher educators and policymakers and on expansive learning processes that occurred in the course of their work.

Expansive Learning

Engeström (1999) coined the term “Expansive Learning” to describe the creation of new professional knowledge, as opposed to the acquisition of existing knowledge previously unknown to the learners. Expansive learning involves a three-pronged change: a transformed pattern of activity, a corresponding new theoretical conceptualizations, and an enhanced agency of the professionals who are involved in creating this theoretical and practical change (Engeström and Sannino, 2010).

In contrast with “action,” “activity” is the collective and coordinated engagement of groups, organizations or communities toward achieving certain objectives or goals. Teacher education can be viewed as an activity system aimed at providing high quality preparation for student teachers and in-service professional development for teachers. Teacher education is divided among multiple activity systems such as teacher educating institutions, schools, and the Ministry of Education. Each of these systems has rules, norms, tools and division of labor, and the objects of their activities are either closely inter-connected or shared (Engeström, 2001; Bakhurst, 2009).

Engeström and his associates (Engeström and Sannino, 2010; Sannino et al., 2016) identify several components in expansive learning processes: Expansive learning begins when professionals discover inherent contradictions, gaps or an undesirable state of affairs that impede their activity. Such discoveries result in questioning, critical examination and analysis of current practices and assumptions, in order to understand how undesired outcomes are formed. The analysis can result in the modeling of a new solution, examining and improving the new model, and implementing it. Reflecting on the process, consolidating and generalizing the new practice may follow. These components are not a fixed sequence of events, and are not necessarily part of all expansive learning processes. The process is fraught with misunderstandings, lacunae, conflicts, and unexpected outcomes. It is heavily influenced by the personal characteristics of the participants, their existing knowledge and goals, and their values, emotions and habits.

Expansive learning develops gradually occurring as a cyclic process in organizations’ “proximal development zone” (Vygotsky, 1978): A new circle opens when existing, stable achievements that were formed in the previous cycle are called into question. The outcome is not guaranteed, and it is quite possible that disagreements and other constraints will lead to the failure of the entire process. However, these failed processes may become a source of inspiration for others.

In order to achieve expansive learning, Change Laboratories are often employed. Change Laboratories are formative interventions that focus on transformations in object-oriented activities of work organizations, typically in times of crisis. In addition to external intervention experts, the participants in the Change Laboratories are committed members of the relevant organization(s) with a high sense of agency. Together, they analyze current practices and identify inherent contradictions that prevent their activity system from attaining its goals (the “first stimulus”). These contradictions may be found within a single activity system, or among objects of interconnected activity systems of different stakeholders. As they try to resolve these contradictions, participants create artifacts and generate ideas that help them change their work environment (the “second stimulus”). Some of these ideas turn out to be particularly fruitful (“germ cells”) as they open up rich and diverse possibilities of conceptualization, practical application and development of characteristics of expansive learning (Sannino and Engeström, 2017; Sannino, 2020). However, a single Change Laboratory intervention may be too short for expansive learning to take place (Sannino and Engeström, 2017).

Change Laboratories Versus Communities of Practice

Like Change Laboratories, CoPs also have the potential to promote expansive learning. The open, critical and inquisitive qualities of CoPs’ discourse, as well as the participants’ commitment to a shared vision, are conducive to questioning and expressing a willingness to experiment with new ideas that are part of the expansive learning process. In comparison with Change Laboratories, CoPs’ continuous activity over a long period enables them to design models and experiment with their ideas, sustain successful changes and further develop their conceptualizations and work patterns. For example, Haapasaari and Kerosuo (2015) describe such a CoP that operated in a single organization. After intensive, but short-term intervention, this CoP was able to sustain changes and further develop them. CoPs are usually formed to achieve continued improvement and are not necessarily reacting to acute crises, as is often the case with Change Laboratories. Furthermore, CoPs do not require external intervention experts. Inter-institutional CoPs can be exceptionally fertile ground for expansive learning because they bring together individuals with varied points of view and enable dissemination of new ideas to a wide swathe of stakeholders. They can achieve collaboration and coordinate between different activity systems. In an illustration of this advantage, MacIver and Groginsky (2011) reported on an inter-institutional CoP of stakeholders in education from Colorado, United States who collaborated to tackle an acute problem of high-school dropout. Together, they identified contradictory practices that exacerbated the problem within activity systems (such as schools’ suspension of truant students) and between inter-connected activity systems (such as schools and social services’ privacy policies that prevented information sharing). Then, they introduced coordinated changes into their respective organizations, resulting in lower dropout rates.

The current paper deals with expansive learning cycles that were triggered by three inter-institutional CoPs whose members were teacher educators and other stakeholders, mainly policymakers from the Ministry of Education. These CoPs operated in the premises the MOFET Institute in Israel.

The Study Context: Inter-institutional Communities of Practice in the MOFET Institute

The MOFET Institute is a nonprofit organization set up by the Ministry of Education in Israel to encourage professional learning of teacher educators who work in academic teacher-educating institutions: colleges and universities. CoPs for teacher educators who hold similar educational leadership positions in various teacher educating institutions are among the many services MOFET offers (Golan and Reichenberg, 2015). The main aim of these CoPs is to provide a framework for professional learning that is adapted to the needs of senior teacher educators, who do not often have colleagues with similar job remits within their respective institutions. In some of these CoPs, policymakers, as well as other stakeholders such as representatives of non-governmental organizations and school principals also participate. After a short description of each CoP we will ask the following questions:

1. What expansive learning processes occurred in each CoP and how did these contribute to their domains of interest?

2. Which of the CoPs’ characteristics may have contributed to their expansive learning?

Methods

This is a multiple case study that adopts the “learning from success” approach (Schechter et al., 2004). A case study is based on the assumption that specific cases, unique as they may be, can provide important insights about humans or organizations. A multiple case study enables researchers to explore a phenomenon through the common characteristics of individual cases (Stake, 2006). “Learning from success” is a method that aims to describe successful cases of practitioners’ actions and to use the tacit knowledge they employed to make explicit formulations that can be implemented in teachers’ practice (Schechter et al., 2004).

Data Sources

CoPs

Two criteria were used to select CoPs for this study: 1. Inter-institutional communities, whose members include teacher educators and policymakers from the Ministry of Education (with the possible addition of representatives of other stakeholders), 2. Communities that have been fully active for more than three years. Six communities met these two criteria, and we chose to focus on three with which we had close acquaintance and access (see below). 1) A CoP of heads of support centers for students with learning disabilities; 2) a CoP of leaders of students’ practical teaching experience within the (PDS) partnership model; and 3) a CoP of leaders of beginning teachers’ internship and induction.

Participants

The description of the three CoPs is based on interviews conducted with thirteen interviewees: four coordinators (The PDS CoP was headed by two coordinators), three Ministry of Education representatives (one for each CoP) and two additional members from each CoP. All the names mentioned below are pseudonyms.

Authors’ Positioning

The study was initiated by the fourth author, who at the time was in charge of MOFET’s CoPs. She noticed that some of the CoPs operating out of MOFET are very influential, attract members from different institutions and have high attendance rates over a long period, whereas others fail to thrive. She therefore asked the co-authors to study the success of some influential CoPs.

One of the authors (O.D.) coordinates the CoP of support centers for students with learning disabilities and is a former participant in the other two CoPs. She was therefore very familiar with both CoPs. Naturally, her familiarity with the CoPs may have influenced data interpretation. Two of the authors (A.G. and O.A.) had previously been coordinators of two of MOFET’s CoPs. This positions the first three authors as colleagues of the interviewees, having no relationships of authority with any of them. CoP coordinators are appointed and remunerated by MOFET, whereas for the other participants, membership is part of their job in their respective institutions. To minimize the effect this may have had upon the interviews, the fourth author, R.S. did not participate in them. It is also important to realize that CoP coordinators have leadership positions within their respective organizations and receive a relatively small part of their salary (up to 12.5%) for this role. They all have tenure, and are therefore entitled to a full position and salary, whether or not they coordinate a CoP or take on other responsibilities.

Interviews

All the interviewees were asked to describe the CoPs from their point of view: the goals of the CoP, the main issues they dealt with and the activities they performed over the years. The interviewees explained how their own activities, as well as those of prominent participants they identified, contributed to the CoPs, and the effects the CoP had on their own professional learning, their institution and on wider contexts. They were asked about the relationships between teacher educators, policymakers and other participants (where relevant) within the CoPs. Finally, they were questioned about difficulties they encountered and how they dealt with them. The interviews were conducted in Hebrew.

Documents

We examined all the documents produced by both communities: minutes of the CoP meetings, annual summaries, research papers, position papers, books and legislative proposals. The minutes and annual summaries were produced by CoP coordinators as part of their work routine. They are available to the public on their respective internet sites (in Hebrew). Position papers and legislative proposals were produced by CoP members as tools they used to change their work environment (“second stimuli” in the terminology used by Sannino and Engeström, 2017). Research papers fulfilled the same role and in addition, they were produced to share CoP members’ new conceptualization with their colleagues in the academia. Together, the documents enabled us to follow the discussions held at CoPs’ meetings, their conceptualizations and how they changed over time, as well as the changes introduced by the CoPs that were implemented in practice.

Data Analysis

Thematic analysis was used to analyze the interviews (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Shkedi, 2019). During the first phase, each interview was analyzed separately. From each interview, we extracted excerpts that referred to the goals of the CoP, its work methods, composition and social relations, its development, significant events that happened over the years, difficulties and challenges, as well as outputs the CoP produced. Combining deductive and inductive approaches, we looked for themes that characterize CoPs, expansive learning, as well as other themes that emerged from the data. During the second phase, we built a thematic and historical account of each CoP by triangulating information received from the different sources: the interviewees, minutes of meetings and publications. We used the minutes of meetings and annual summaries to complete our knowledge about the issues the CoPs discussed and the activities they performed. All other publications provided information about theoretical conceptualizations the CoPs constructed, as well as significant changes in practice. We gave the resultant “thick” case descriptions of the CoPs to some of the interviewees to ensure that they accurately reflected what they had said, and that the whole description was consistent with their perceptions of their CoPs. During the third stage, we focused on events we perceived as incidents of expansive learning: incidents in which the CoPs transformed current practices and constructed new conceptualizations. We tried to identify shared characteristics that could have led to expansive learning. Throughout this process, we held joint discussions with all four researchers to ensure credibility and achieve consensus.

Findings

In this section, we describe the activities and expansive learning processes that occurred in each CoP. We then look for shared characteristics of CoPs that could have supported expansive learning.

Heads of Support Centers for Students with Learning Disabilities

Background and Initial Contradictions

Members of this CoP are heads of support centers in higher education institutions’ for students with learning disabilities. Other stakeholders who take part in this CoP are policymakers from government ministries (education, health and social welfare), non-governmental organizations’ representatives and former students. The CoP has existed for more than fifteen years and meets nine to ten times during the school year, with about 30 people attending each meeting.

The CoP coordinator presented its vision in a document distributed in September 2008 by the MOFET Institute, to explain what the CoP does, and to attract additional participants: “Currently… there is no doubt in academia in Israel that a student with learning disabilities should be provided with study options on a par with all other students… However, there is not enough knowledge sharing and collaboration between different support centers. The participants we interviewed shared this vision of equity and inclusion. For example, Alice, the representative of the Ministry of Education in the CoP said: “Being a participant turned me into an ambassador promoting this issue in the Ministry of Education, in the Knesset [Israeli Parliament] and in every forum in which I participated.”

One of the main objects of academic institutions is to provide high quality education to students. The support centers operate as units in academic institutions to help students with learning disabilities complete and graduate from academic studies. The conflict of motives within, and between, these activity systems arises from two conflicting conceptualizations of higher education goals (Snoek at al., 2003): “Individualistic-pragmatism” defines the goal of higher education as preparing students for the requirements of a knowledge-based competitive economy. Institutions must compete for students, research funds and their academic reputation in order to survive. In contrast, “Social coherent idealism” aims at striking a balance between supporting individuals’ aims and those of society as a whole. In democratic societies, “idealism” includes educational institutions’ commitment to social justice and equity. This inherent contradiction leads to a set of secondary contradictions, such as the conflict between higher education institutions’ roles as gatekeepers of the professions they teach and educators, as well as conflicts concerning academic institutions’ reputation: Strict adherence to demanding policies may result in high attrition and low recruitment. On the other hand, low standards may harm the institutions’ academic level, lead to low recruitment, and even loss of official recognition. In the realm of teacher education, institutions that align themselves with the “Individualistic-pragmatism” approach cannot claim they provide high quality preparation for teachers, if they cannot help their own struggling students.

The secondary contradictions were evident when the heads of the support centers shared their concerns and difficulties in CoP meetings. For example, a protocol documenting a CoP meeting that took place on February 19, 2008 recorded a dialogue in which one of the participants expressed her doubts whether a student with dyslexia could become a good teacher and should be certified by her academic institution:

Tina: When the class is not functioning… and the teacher is not good [and] writes with spelling mistakes ... I do not want this teacher.

Dalia: The connection you made between spelling errors and dysfunction is a stigmatizing generalization. When all the students fail, it is clear that the teacher is not good… But we need to discuss the core of the profession and examine whether the student with the learning disabilities is not good at the core.

It is evident, that back in 2008, some of the participants did not wholeheartedly identify with the CoP’s vision, and felt there was a contradiction between their role as support providers and their role as gatekeepers of the teaching profession. In a meeting that took place four years later, on November 25, 2012, the CoP participants were more confident, but they felt that their supervisors were doubtful:

Amy: When I am summoned to stakeholders, I am perceived as a money wasting factor… The head of the teaching and learning center told me: “whenever I see you–I see problems…” I wish to be perceived as a solution and not as a problem-a solution that saves money to the system and prevents dropouts… I have to initiate the submission of reports, but there is not too much interest in them.

Irene: I also feel that the [support] center is an economic problem. It exposes the fact that there are people with problems in the institution. They prefer to see the outstanding [students] rather than the miserable ones.

Diane: Our president, when he hears “learning disabilities,” his hair stands on end.

The CoP Coordinator Recalls:

Many support centers’ supervisors felt… alone... Some were corrective teaching specialists, but they were not experts in adults with learning disabilities. Even those who were, had never learned how to be administrators. Their relationships with the academic institution were unsatisfactory. During the first years, support centers were controversial due to skepticism concerning the suitability of students with learning disabilities to academic studies. They often received negative messages expressing the dissatisfaction of college or university heads with the growth and development of the support centers… fearing that the university’s name would be associated with learning disabilities. The mass influx of students with learning disabilities to higher education in a specific academic institution could deter other students from enrolling.

Sharing those concerns was the first stimulus that explicitly exposed the conflicting motives toward students with learning disabilities: On the one hand, the wish to help them succeed, and on the other hand, fears that it could lower professional standards and be harmful to the academic institution.

The Second Stimulus

During the first years, the CoP participants shared their doubts and difficulties, as well as professional knowledge. For instance, many of the meetings that took place in 2008 dealt with preparing students with learning disabilities for the workplace. The meetings contributed to participants’ wellbeing and professional learning:

We have inclusion, empathy, giving… I may invite other professionals who are interested. This is not a closed clique. On the contrary, we are encouraged to invite more people. I like to go to meetings… I feel I am not alone. I receive counseling and support (Ada, a support center head).

Initially, the CoP did not generate a solution to the conflict. The turning point was the participants’ decision to perform and publish case studies of students who were helped by their centers and attained significant academic and professional accomplishments. They thought these stories would prove that students with learning disabilities could be supported without lowering academic or professional standards. This idea turned out to be the “second stimulus:” external symbolic artifacts, with the help of which the participants tried to gain control of the problematic situation (Sannino and Engeström, 2017; Sannino, 2020). Working toward identifying and describing success stories was introduced into the CoP’s schedule at the beginning of the 2009/2010 academic year.

While working on their respective case studies, it became apparent that the support centers’ staff possessed extensive tacit knowledge, which became explicit when discussed. Working methods, which led to successful outcomes, had been tried out over the years intuitively and unsystematically. These methods that were not previously recognized as such, had now been identified and integrated as routine working practices. Naturally, many of these practices involved students with learning difficulties who were making use of the centers. For example, the CoP members realized that support center staff had to be available to help students outside of standard working hours and also to be willing to meet them at other venues, not only at the support centers’ offices. Staff availability increases students’ confidence that staff members believe in their ability to succeed and attach high value to students’ success. Other practices involved recruiting help from other stakeholders within the institution and introducing systemic changes. For example, in one of the institutions, the support center succeeded in raising the grades of students who turned to the center for help in English. Following their success, the English department decided to refer all struggling students to the center. This, and similar stories from other institutions in other disciplines, led the CoP participants to the realization that their work could be promoted if they were proactive in reaching out to teachers, explaining what learning disabilities are, and asking them whether they had students who needed help. They realized that with this proactive approach it was easier to get teachers’ consent for special accommodations, such as ignoring spelling mistakes. In the same meeting that took place in November 2012, ten of the thirteen participants took it upon themselves to perform tasks that would enhance the centers’ impact, through actions directed at other stakeholders in their respective institutions. For example, one participant distributed flyers explaining what learning disabilities are, organized a college event with a lecture and a stand-up show about attention deficit disorders and produced a film for the college’s internet site that describes the center’s services. This minutes of the meeting also attest to the participants’ commitment to the CoP’s work. The success stories and the extracted operating principles were published in a book (Shemer et al., 2016). They provided the CoP participants with improved tools to perform their roles. Furthermore, they resulted in changing the CoP’s object from teaching students with learning disabilities to recruiting, guiding and coordinating between different stakeholders: Mainstream students were recruited to serve as mentors to students with learning disabilities and their work was supervised by the support centers. The centers disseminated information about learning disabilities to other teachers and the institutions’ administrators. Teachers were asked to collaborate in referring students to the centers and providing them with adjusted teaching and assessment, according to centers’ guidelines and explanations. Legislators, policymakers from the Ministry of Education and academic institutions’ administrators were asked to introduce supportive policies and secure budgets. The systemic work transformed the CoP members’ personal positioning from undervalued and isolated teachers into acknowledged professionals who work collaboratively, endowing them with a new sense of agency (Engeström and Sannino, 2010): “[The CoP] raised the position’s status [i.e. the position of support center’s head], put us on the map, it is important and not obvious” (Ann, a support center head).

The Second Cycle of Expansive Learning: Multiple Disability Centers

The above-mentioned expansive learning cycle resulted in the institutionalization and professionalization of the support centers’ activities. Currently, every higher education institution has a center, and their existence is no longer viewed as a threat to institutions. This development took place in higher education institutions’ zone of proximal development (Sannino and Engeström, 2017): the previously existing restricted centers flourish and their work is now coordinated with that of other stakeholders. However, the support centers’ success in making academic studies accessible to students with learning disabilities raised awareness about the needs of other excluded populations. It seemed that by ignoring other populations, the centers undermined their own vision of equity and equal opportunities for all students. This inherent contradiction could be noticed only after the success of the previous cycle. Discussions about turning support centers into multiple disability centers began a few years ago, and opinion was divided. Some members argued that the centers specialized in learning disabilities and that expansion would harm staff professionalism. Others argued that no one else is equipped to provide a solution for students with multiple disabilities and that it is only natural for the centers to provide support for the entire range of special needs. In order to enhance the centers’ ability to support all students, the CoP invited representatives of multiple organizations that provide help to students with different needs. These members helped to bridge professional gaps. Eve, a participant from the Ministry of Education noted:

I believe that the addition of a director of a project that supports students with mental health issues to the CoP was a welcome addition, and may have lowered concern about working with this population… I feel that directors of support centers for students with learning disabilities are often forced to deal with people with mental health issues and this meeting helped them…

The National Insurance Institute encouraged this transformation, as the CoP coordinator explained: “The National Insurance Institute held professional training for “accessibility supervisors…” It offered funds for building, expansion and equipment to centers that agreed to handle multiple disabilities.” These means are part of the efforts to overcome the inherent contradiction of having support centers only for students with learning disabilities (the second stimuli). The centers’ activity have been vastly transformed and most of them provide services to students with physical disabilities and mental health issues, in addition to students with learning disabilities. However, the transformation is not completed yet. Discussions currently revolve around additional populations that the centers could assist.

Due to the expanded role of the support centers, some of the CoP discussions are no longer relevant to all of the participants. The CoP tried to handle the problem by setting up ad-hoc working groups. Others felt that adding new members leads to repetition of issues, fatigue and frustration:

The very high turnover rate in this field is not easy for me. New members join and ask questions and I no longer have the patience for this. We are a limited nucleus of people who have been involved in this field for a long time and while it is nice that new members join, it is also a bit tiring. (Ada, a support center head).

To summarize, the main achievements of this CoP are conceptualizing the support centers’ operating principles, consolidating their practices, and expanding their services. The object of the support centers changed from teaching students with learning disabilities to helping students with multiple disabilities and coordinating services with a wide array of stakeholders.

Leaders of Students’ Practical Teaching Experience within the Partnership Model

Background

The partnership model between higher education institutions and schools (PDS-Professional Development Schools) is guided by two basic principles: Student teachers are heavily involved in different aspects of their school’s educational work, and all the partners in the teacher education process: student teachers, pedagogical counselors, teacher mentors, and other involved parties participate in professional learning (Darling-Hammond, 2006). The CoP was set up fifteen years ago at the MOFET Institute by teacher education colleges that started to work according to this model in an exploratory manner. The CoP met six times during the school year, with up to 30 people attending meetings. The CoP members dealt with shared challenges, such as selecting partner schools and involving them in teacher education.

Expansive Learning

The PDS initiatives try to solve the dissonance between closely inter-related activity systems: teacher preparation by higher education institutions and schools’ expectations of teachers. Historically, his contradiction emanates from the “academization” of teacher education (Robinson, 2017), and is therefore shared by many institutions worldwide. The vision of PDS initiatives is to provide teacher preparation that addresses practical needs through extensive practice in schools and collaboration between schools and academic institutions (Teitel, 2003). The schools’ activity expands to educating student teachers, whereas the academic institutions’ activity expands to providing professional development to in-service teachers. In Israel, the first PDS initiatives lacked a supportive infrastructure, and modes of operation were not consolidated. According to the coordinator:

The goals were to develop knowledge about partnership models. To have a dialogue with decision makers at the Ministry of Education… to encourage teacher education colleges to adopt partnership models, and to have a framework to discuss problems that interfere with the execution of partnership arrangements. We were learning by reading papers and research, as well as from partnership models worldwide. We tried to produce the principles of partnership between academia and the education field in the Israeli context. We were looking to forge a path and for partners to join us on the journey.

The second coordinator adds that the CoP goals were: “meeting people from different colleges. PDS models are applied somewhat differently in different places. So, to share ideas, expose difficulties… on the one hand, and learn from successes on the other hand.”

The CoP members published their distinct models and accumulated knowledge in academic publications. Research findings indicated that student teachers who participated in the PDS model were better prepared teachers with a higher retention rate. Nonetheless, it was very difficult to maintain the model since it is time consuming and requires a lot of extra work for all those involved. The CoP had representatives of the Ministry of Education, but they worked in the teacher education department, and their work was not coordinated with that of other ministry departments. The latter initiated projects that required teachers to participate in numerous professional development activities. Concurrently, a national teaching reform was launched that required teachers to spend more time on individual tutoring of pupils. These requirement left no time for meetings with student teachers and teacher educators.

The CoP authored a position paper, and presented it to the Ministry of Education. This publication was the second stimulus, attempting to overcome the contradictions between the activity systems of the Ministry, schools and teacher educating institutions. For example, the position paper stated that designated time slots for students, teachers and academic supervisors’ meetings should be assigned, and that mentor teachers should receive professional preparation and remuneration. In 2016, the Ministry of Education initiated a program based on the PDS model. The Ministry acknowledged the contribution of the CoP’s experience and publications in its policy paper (the “Academy-Classroom” project), and accepted many of the requests that appeared in the position paper (including those cited above). By implementing this model, policymakers took over the leadership of the process from the CoP, which ceased operations in 2017, the second year in which the Ministry of Education’s program was implemented.

The PDS model changes schools, teacher educating institutions and the government’s activity systems. Schools become partners in teacher education, in addition to teaching pupils. Teacher educating institutions take part in school teachers’ professional learning and student teachers are integrated into school staff. The PDS model that was dependent upon the goodwill of individual schools and teacher educators who decided to collaborate, is now mandated, budgeted, regulated and monitored by the Ministry of Education.

Leaders of Beginning Teachers’ Internship and Induction Units

Background

The high attrition rate of beginning teachers is a persistent challenge that bothers all stakeholders in education (Craig, 2017). The professional literature indicates several factors that could increase beginning teachers’ perseverance. The most prominent factors are: Intensive pre-service practical experience (Ingersoll et al., 2014); mentoring (Ingersoll and Strong, 2011); and support of beginning teachers by the school principal and other teachers (Thomas et al., 2019).

In 1990, the Israeli Ministry of Education decided to support first year teachers through an internship program. Over the years, the support expanded to cover the first three years in the profession. Teacher education colleges established “transition into teaching” units that are responsible for supporting beginning teachers and for training mentors. The heads of internship programs CoP was established in 1996. Currently, the participants of the CoP are heads of internship, induction and mentor training programs, as well as heads of the “transition into teaching” units from all teacher educating institutions in Israel. The CoP coordinator is the administrator in charge of beginning teachers in the Ministry of Education. The CoP meets 9–10 times during the school year, with 60–70 people attending each meeting. This poses a difficulty, since the larger the CoP, the harder it becomes to provide a solution for each member’s individual needs. This CoP tried to solve this issue by working in sub-groups.

The CoP’s vision, as it appears on its internet site, is “to ascertain that high quality [beginning teachers] integrate and persevere in teaching.” Although membership in this CoP is compulsory, many practitioners have adopted the CoP’s vision. A participant named Helen said: “It is a deeply moving experience to meet so many peers who are so highly-motivated to ensure the optimal absorption of beginning teachers.” This quotation reveals Helen’s identification with the CoP’s vision, as well as her belief that other participants are equally committed.

The CoP initiated projects that aim to raise stakeholders’ awareness of beginning teachers’ difficulties and improve the support they receive: annual competitions of beginning teachers’ stories and posters, as well as a competition for the “best absorbing schools” award. The CoP coordinator consults with the participants before new policies are set. She notes: “‘Policies are decided upon in the CoP and each member is responsible for implementing them in his/her college. Having the chance to be part of a policy-making team strengthens the members’ commitment to participate.”

The CoP is characterized by the good ambience of professional friendships in which members can talk about their difficulties and receive help. Mary, a participant, said “It is lonely for me… in the college. Within the CoP, I can meet the other coordinators and Ministry of Education representatives. They give advice and support for a wide range of issues. They understand me.”

Expansive Learning

Teacher attrition is a complex challenge that does not result from a single cause. One contradiction that the above mentioned methods of supporting teachers’ induction does not address is that teacher educating institutions are disconnected from absorbing schools following the students’ graduation. Even in institutions in which students are provided with extensive practical experience, the schools in which they gain their experience are not the same schools in which they work after graduation. Thus, teacher preparation is “generic,” whereas teachers’ induction takes place in a specific context. Similar to the previous example, this contradiction also emanates from the “academization” of teacher education (Robinson, 2017).

The “second stimulus” was the “Multi-player Induction Team” (MIT) model developed in 2012 by one of the teacher educating colleges (Beit-Berl College) that participates in this CoP. According to this model, interns and beginning teachers are introduced into a school or a community as a group. Beginning teachers’ workshops take place at the absorbing school or community, and are facilitated by the college. They are attended by mentor teachers, pedagogical counselors, beginning teachers and additional stakeholders, such as representatives of the local authority, the school principal, homeroom teachers or the school counselor. This model positions beginning teachers as a focus of interest, expands the support they receive, and allows for immediate treatment of problems they encounter (Thomas et al., 2019). MITs empower and encourage beginning teachers to contribute as a group to their school or community, thus strengthening their sense of autonomy and professional efficacy (Ryan and Deci, 2000). The partnership between the teacher educating institution and the absorbing school or community contributes to closing the gap between the two, and encourages both institutions to introduce changes into their preparation and absorption practices, respectively. The MIT model changes the teacher education activity system from pre-service preparation of student teachers to include graduates’ induction into absorbing schools, and expands their interfaces with inter-connected activity systems (schools and local authorities).

The MIT model was introduced to the CoP in 2015. By the end of 2016, there were six teacher education colleges that had established MITs. This project was supported by the European Union from 2017 to 2019 (https://proteach-project.macam.ac.il). Further support is currently provided to nine colleges that have MITs to prepare mentors within this model (https://promentors.org/).

Shared Characteristics that may have Contributed to CoPs’ Expansive Learning

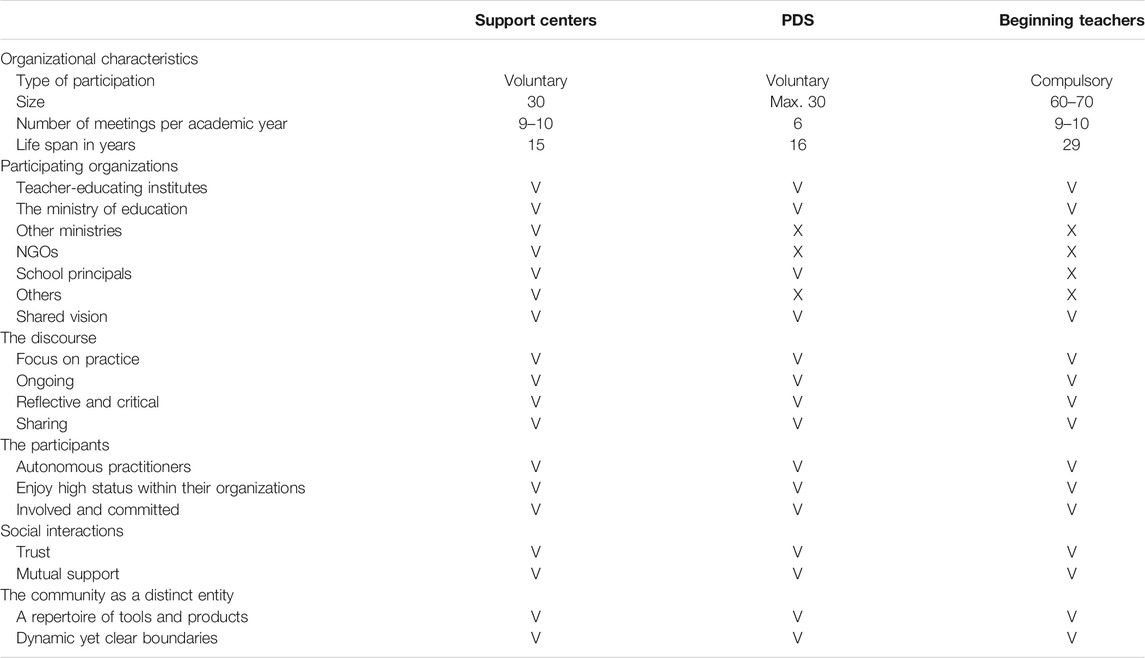

At first sight, the three CoPs are very different from each other in their visions, domains of interest, and the nature of expansive learning they achieved. However, Table 1 reveals similarities, some of which could be conducive to expansive learning.

The CoP members were committed to the shared vision: providing higher education to students with special needs and bridging the gap between teacher preparation and schools, in order to improve beginning teachers’ absorption and retention. The members attested that the CoPs provided them emotional support and knowledge. Based on mutual trust that developed over time as a result of the support the CoPs provided, the members held open and honest discussions that focused on practice, including inherent conflicts in their activity systems. Being committed to the vision, they were willing to step out of their comfort zones and try to implement new ideas, such as reaching out to other teachers in their institutions or to school principals and providing professional learning opportunities to teachers. These ideas were further explored during the CoPs’ regular and frequent meetings. As mid-level administrators and policymakers, they were able to introduce changes into the units they led, in addition to changing their own practices. The three CoPs included various stakeholders from different organizations. This inter-institutional composition is important, not only because the members are exposed to different views and realms of knowledge, but also because it enables the CoPs to introduce coordinated and complementary changes of practice simultaneously. Therefore, although the number of members in each CoP was viewed as too large by some of the interviewees, it may have helped in disseminating changes originating in CoPs to a large number of organizations. The participating organizations had complementary roles. This is particularly true of teacher-educating institutions and the Ministry of Education. The Ministry of Education provided regulatory support to educational initiatives, whereas teacher educators implemented policies and provided feedback to policymakers. The CoPs’ publications are part of their repertoire, and disseminate their conceptualizations to other institutions and stakeholders.

Discussion

The current study describes three CoPs that led to learning at the individual, organizational and public level. In the following, we discuss the CoP characteristics and expansive learning processes shared by the three communities, and then deal with the theoretical implications of this study and the empirical implications for teacher educators’ professional learning.

Expansive Learning Triggered by Communities of Practice

The CoPs' participants were practitioners who enjoy professional autonomy and who were attempting to improve their practice. Each of the three CoPs had a shared vision that inspired the members’ work: providing equal academic opportunities to students with special needs in the first CoP, and bridging the gap between teacher preparation in academic institutions and retention of high quality teachers in schools in the other two (Wenger, 1998; Stoll et al., 2006; DuFour et al., 2008). The members were able to disclose and share their difficulties (Andrews and Lewis, 2007) because of the trusting relationship within the CoPs, which is an outcome of long-term cooperation and mutual support (Stoll et al., 2006). The participants’ commitment encouraged them to step out of their comfort zones and look for ways to achieve their vision (Wenger-Trayner et al., 2015). Working collaboratively over a long period is needed in order to devise, try out, improve and conceptualize changes (Sannino and Engeström, 2017). The inter-institutional composition of both CoPs was important not only because members were exposed to different views and realms of knowledge (Engeström, 1999; Engeström and Sannino, 2010), but also because it enabled the CoPs to introduce coordinated and complementary changes of practice simultaneously. Being mid-level administrators and policymakers, the members were able to introduce changes into the units they led (Wenger-Trayner et al., 2015), in addition to changing their own practices, thereby gaining a new sense of agency (Engeström and Sannino, 2010). Expansive learning cycles were triggered by all the CoPs. The object of the support centers’ activity changed from teaching students with learning disabilities to helping students with multiple disabilities and coordinating services with a wide array of stakeholders. In the case of the other two CoPs, the object of teacher educating institutions changed from preparing student teachers to collaborating with schools in teacher preparation, beginning teachers’ induction and in-service teachers’ professional learning. Governmental departments realized they need to be more involved, supporting change processes with suitable policies and budgets, instead of hoping that academic freedom and market forces would suffice. Changes were therefore observed at the national, institutional and individual levels. New conceptualizations concerning support for students with special needs and teachers’ preparation, induction and professional learning have emerged and been published.. The CoPs’ publications are part of their repertoire (Wenger, 1998). They enable dissemination and further examination of their new conceptualizations by other stakeholders.

Theoretical Implications

When we first embarked on a theoretical analysis of the change processes triggered by each of the CoPs, we believed they were similar to Cultural-Historical Activity Theory’s third-generation studies (Sannino and Engeström, 2017), since closely inter-connected activity systems were involved that transformed from being compartmentalized practices and expertise into becoming collaborative work named “knotworking” (Engeström and Sannino, 2020, p. 10).

The PDS model CoP was different from the other two, since its successful attempt to transform teacher preparation led to the cessation of its operation. Participant turnover was evident in all the CoPs, as could be expected in view of their long period of operation. One of the Non-Governmental organizations that took part in the support centers CoP ceased to operate after a few years. Changes in participating individuals and organizations is in alignment with the “fourth generation” activity systems, in which multiple organizations attempt to tackle persistent challenges. Such attempts entail “the involvement of a wide variety of actors at multiple levels–local, regional, national and possibly global” (Engeström and Sannino, 2020, p. 11). In our case, attempts to improve teacher education involved individual teacher educators, schools, teacher educating institutions and the Ministry of Education. During their activities, “some organizations merge or redefine their responsibilities. Yet we also see that these shifts are promptly dealt with: replacements and new actors step in, organizations regroup to compensate for gaps” (ibid). As Engeström and Sannino (2020) acknowledge, the theory of “fourth generation” activity systems is still under construction. We hope that this process takes into consideration conceptualizations developed by Wenger-Trayner and his colleagues (2015). Specifically, we believe that in order to address meaningful and persistent challenges, collaborative action of multiple individuals and organizations is required. In such cases, CLs may be insufficient due to their short duration and cost, as well as the large number of heterogeneous parties involved and the lack of cohesiveness among them. Our findings show that inter-institutional CoPs consisting of committed representatives of multiple stakeholders that operate over a long period can replace CLs as change agents.

Teacher Educators’ Professional Learning

It is currently agreed that teacher educators’ career-long professional learning is crucial for high quality teacher education (European Commission, 2013; Lunenberg et al., 2014; Vannassche et al. 2015). However, professional learning is predominantly viewed as the responsibility of individual teacher educators. Although some institutions provide professional learning opportunities to their staff, these opportunities are not coordinated, and institutional involvement is minimal (Griffiths et al., 2014; Meeus et al., 2018; Guberman et al., 2020). As a result, different paths of professional learning may come at the expense of each other, as is often the case in the main areas of teacher educators’ professional learning: teaching, research and educational leadership (Griffiths et al., 2014; Guberman and Mcdossi, 2019; Smith and Flores, 2019).

Teacher educators who have educational leadership roles within their respective institutions are in a particularly vulnerable position with respect to their professional development, because they work in isolation, without colleagues with similar roles and concerns. Inter-institutional CoPs offer them an opportunity for professional learning together with others who have similar positions in other institutions, in which they are active in initiating practical experimentation and theoretical conceptualization (MacPhail et al., 2018). Furthermore, such CoP participants can provide coordinated and institutionalized professional learning opportunities for teacher educators within their respective departments. These opportunities may combine changes in conceptualizations and practice that are examined through practice. Thus, inter-institutional CoPs have a potential of transforming the currently fragmented landscapes of teacher education (Flores, 2016) into coherent ones.

Establishing inter-institutional CoPs is not an easy task. In the current study, the CoPs’ members and the organizations they represented had a shared vision, but they were also competing with each other over students, academic and public reputation. Under these circumstances, the already difficult challenge of building a trusting relationship was even more challenging (Thompson, 2005; Roberts, 2006). However, we believe that the potential gains outweigh the difficulties.

The study limitations are the small number of CoPs examined and the interpretative nature of the analysis. We suggest a close scrutiny of the CoPs’ discussions to observe how mutual relationships and change processes develop within CoPs over time. The expansive learning which occurred in these and in other, similarly structured CoPs, encouraged the Ministry of Education to initiate new CoPs consisting of policymakers and heads of academic programs. We suggest that these also be studied to examine whether expansive learning occurs in them as well.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the MOFET Institute IRB. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

Ainat Guberman wrote the main paper. Interviews were conducted by AG, OU and OD. All authors participated in collecting data about the CoPs and documents they produced as well as data analysis

Funding

This work was supported by the MOFET Institute.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Andrews, D., and Lewis, M. (2007). “Transforming practice from within: the power of the professional learning CoP,” in Professional learning communities: divergent, depth and dilemmas. Editors L. Stoll, and K. S. Louis (Maidenhead: Open University Press), 132–148.

Avidov-Ungar, O. (2018). Professional development communities: the perceptions of Israeli teacher-leaders and program coordinators. Prof. Dev. Educ. 44 (5), 663–677. doi:10.1080/19415257.2017.1388269

Bakhurst, D. (2009). Reflections on activity theory. Educ. Rev. 61 (2), 197–210. doi:10.1080/00131910902846916

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3 (2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Craig, C. L. (2017). International teacher attrition: multiperspective views. Teach. Teach. 23 (8), 859–862. doi:10.1080/13540602.2017.1360860

Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Powerful teacher education: lessons from exemplary programs. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley.

Dickson, J., and Mitchell, C. (2014). Shifting the role: school-District superintendents’ experience as they build a learning CoP. Can. J. Educ. Adm. Pol. 158, 1–31. Available at: https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/cjeap/issue/view/2823

DuFour, R., DuFour, R., and Eaker, R. (2008). Revisiting professional learning communities at work: new insights for improving schools. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. J. Educ. Work 14 (1), 133–156. doi:10.1080/13639080020028747

Engeström, Y. (1999). “Innovative learning in work teams: analyzing cycles of knowledge creation in practice,” in Perspectives on activity theory. Editors Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen, and R. L. Punamäki (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 377–404.

Engeström, Y., and Sannino, A. (2020). From mediated actions to heterogenous coalitions: four generations of activity-theoretical studies of work and learning. Mind Cult. Activ. doi:10.1080/10749039.2020.1806328

Engeström, Y., and Sannino, A. (2010). Studies of expansive learning: foundations, findings and future challenges. Educ. Res. Rev. 5, 1–24. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2009.12.002

European Commission (2013). Supporting teacher educators for better learning outcomes. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission.

Flores, M. A. (2016). “Teacher education curriculum,” in International handbook of teacher education. Editors J. Loughran, and M. L. Hamilton (Singapore: Springer), 187–230.

Golan, M., and Reichenberg, R. (2015). “Israel’s MOFET institution: “CoP of communities” for the creation and dissemination of knowledge of teacher education,” in International teacher education: promising pedagogies. Editors S. Pinnegar Series, J. C. Craig, and L. Orland-Barak (Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald), Vol. 22C, 299–316.

Goodwin, A. L., Smith, L., Souto-Manning, M., Cheruvu, R., Tan, M. Y., Reed, R., et al. (2014). What should teacher educators know and be able to do? Perspectives from practicing teacher educators. J. Teach. Educ. 65 (4), 284–302. doi:10.1177/0022487114535266

Griffiths, V., Thompson, S., and Hryniewicz, L. (2014). Landmarks in the professional and academic development of mid-career teacher educators. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 37 (1), 74–90. doi:10.1080/02619768.2013.825241

Guberman, A., and Mcdossi, O. (2019). Israeli teacher educators’ perceptions of their professional development paths in teaching, research and institutional leadership. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 42 (4), 507–522. doi:10.1080/02619768.2019.1628210

Guberman, A., Ulvik, M., Macphail, A., and Oolbekkink-Marchand, H. (2020). Teacher educators’ professional trajectories: evidence from Ireland, Israel, Norway and the Netherlands. Eur. J. Teach. Educ., 1–18. doi:10.1080/02619768.2020.1793948

Haapasaari, A., and Kerosuo, H. (2015). Transformative agency: the challenges of sustainability in a long chain of double stimulation. Learn. Cult. Soc. Int. 4, 37–47.

Hadar, L. L., and Brody, D. L. (2018). Individual growth and institutional advancement: the in-house model for teacher educators' professional learning. Teach Teacher Educ: An International Journal of Research and Studies, 75 (1), 105–115.

Hairon, S., Goh, J. W. P., Chua, C. S. K., and Wang, L. (2017). A research agenda for professional learning communities: moving forward. Prof. Dev. Educ. 43, 72–86. doi:10.1080/19415257.2015.1055861

Ingersoll, R., Merrill, L., and May, H. (2014). What are the effects of teacher education and preparation on beginning teacher attrition?. Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania.

Ingersoll, R. M., and Strong, M. (2011). The impact of induction and mentoring programs for beginning teachers: a critical review of the research. Rev. Educ. Res. 81 (2), 201–233. doi:10.3102/0034654311403323

Lunenberg, M., Dengerink, J., and Korthagen, F. (2014). The professional teacher educator: roles, behaviour, and professional development of teacher educators. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense.

MacIver, M. A., and Groginsky, S. (2011). Working statewide to boost graduation rates. Phi Delta Kappan 92 (5), 16–20. doi:10.2307/27922504

MacPhail, A., Patton, K., Parker, M., and Tannehill, D. (2014). Leading by example: teacher educators’ professional learning through communities of practice. Quest 66 (1), 39–56. doi:10.1080/00336297.2013.826139

MacPhail, A., Ulvik, M., Guberman, A., Czerniawski, G., Oolbekkink-Marchand, H., and Bain, Y. (2018). The professional development of higher education-based teacher educators: needs and realities. Prof. Develop. Edu. 45 (5), 1–14. doi:10.1080/19415257.2018.1529610

Margolin, I. (2011). Professional development of teacher educators through a "transitional space": a surprising outcome of a teacher education program. Teach. Educ. Quart. 38 (3), 7–25.

Meeus, W., Cools, W., and Placklé, I. (2018). Teacher educators developing professional roles: frictions between current and optimal practices. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 41 (1), 15–31. doi:10.1080/02619768.2017.1393515

Roberts, J. (2006). Limits to communities of practice. J. Manag. Stud. 43 (3), 623–639. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00618.x

Robinson, W. (2017). “Teacher education: a historical overview,” in The Sage handbook of research on teacher education. Editors J. Husu, and D. J. Clandinin (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 1, 49–67.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25 (1), 54–67. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Sannino, A., and Engeström, Y. (2017). Co-generation of societally impactful knowledge in Change Laboratories. Manag. Learn. 48 (1), 80–96. doi:10.1177/1350507616671285

Sannino, A., Engeström, Y., and Lemos, M. (2016). Formative interventions for expansive learning and transformative agency. J. Learn. Sci. 25 (4), 599–633. doi:10.1080/10508406.2016.1204547

Sannino, A. (2020). Transformative agency as warping: how collectives accomplish change amidst uncertainty. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. doi:10.1080/14681366.2020.1805493

Schechter, C., Sykes, I., and Rosenfeld, J. (2004). Learning from success: a leverage for transforming schools into learning communities. Plan. Changing 35 (3-4), 154–168. doi:10.1080/13603120701576274

Shemer, O., Rosenfeld, J. M., Dahan, O., and Daniel-Hellwing, A. (2016). What have we actually done? Success stories of support centers for students with learning disabilities. Tel Aviv, Israel: Mofet and Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institution.

Shkedi, A. (2019). Introduction to data analysis in qualitative research. Singapore: Springer International Publishing.

Smith, K., and Flores, M. A. (2019). The Janus faced teacher educator. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 42 (4), 433–446. doi:10.1080/02619768.2019.1646242

Snoek, M., Baldwin, G., Cautreels, P., Enemaerke, T., Halstead, V., Hilton, G., et al. (2003). Scenarios for the future of teacher education in Europe. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 26 (1), 21–36. doi:10.1080/0261976032000065616

Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., and Thomas, S. (2006). Professional learning communities: a review of the literature. J. Educ. Change 7 (4), 221–258. doi:10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8

Teitel, L. (2003). The professional development schools handbook: starting, sustaining, and assessing partnerships that improve student learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Thomas, T., Tuytens, M., Moolenaar, N., Devos, G., Kelchtermans, G., and Vanderlinde, R. (2019). Teachers' first year in the profession: the power of high-quality support. Teach. Teaching. 25 (2), 166–188.

Thompson, M. (2005). Structural and epistemic parameters in communities of practice. Organ. Sci. 16 (2), 151–164. doi:10.1287/orsc.1050.0120

Vannassche, E., Rust, F., Conway, P., Smith, K., Tack, H., and Vanderlinde, R. (2015). “InFo-TED: bringing policy, research and practice together around teacher educator development,” in International teacher education: promising pedagogies. Editors C. Craig, and L. Orland-Barak (Brinkley, United Kingdom: Emerald Books), 341–364.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: learning, meaning and identity. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Wenger, E., and Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015). Communities of practice: a brief introduction. Available at: http://wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/ (Accessed November 19, 2018).

Wenger-Trayner, E., Fenton-O’Creevy, M., Hutchison, S., Kubiak, C., and Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015). Learning in landscapes of practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

Keywords: communities of practice, teacher educators, professional development, policy formation, educational policy, expansive learning, workplace learning

Citation: Guberman A, Avidov-Ungar O, Dahan O and Serlin R (2021) Expansive Learning in Inter-Institutional Communities of Practice for Teacher Educators and Policymakers. Front. Educ. 6:533941. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.533941

Received: 10 February 2020; Accepted: 08 January 2021;

Published: 22 February 2021.

Edited by:

Jukka Husu, University of Turku, FinlandReviewed by:

Maria Antonietta Impedovo, Aix-Marseille Université, FranceJaako Hilppö, University of Helsinki, Finland

Copyright © 2021 Guberman, Avidov-Ungar, Dahan and Serlin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ainat Guberman, ainatgub@gmail.com

Ainat Guberman

Ainat Guberman