- University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

Teaching is a profession dominated by women. Principalship, on the other hand, is an arena populated by men. This study, which reports from the Republic of Ireland, reveals the challenges and opportunities encountered by ten women, from a cross-section of school type and contexts, as they pursued a path to principalship. The nature of their personal contexts in addition to career ambitions formed in some cases earlier, in others later, in their teaching lives, acted as informants along their professional trajectories. Leadership is identified as a male prerogative, thereby providing additional hurdles for women as they cross the bridge to an arena that operates cultural climates conducive to male working practices. The women, in this study, articulated how national culture, organizational practices, and personal obligations all acted in tandem to assist or hinder in configuring their labyrinthine career aspirations.

Introduction

Postprimary teaching in the Republic of Ireland is a profession dominated by women. Yet despite their numerical advantage, they are proportionally unrepresented at the principalship level. This phenomenon reflects international trends to promote men to the most senior positions within schools despite their lack of proliferation within the teaching ranks (Coleman, 2003; Fuller, 2009; Fitzgerald, 2014). This study, which reports from a life story perspective, seeks to examine the career paths of female teachers who aspire to the position of postprimary principal in the Republic of Ireland. It is concerned with exploring the enabling and constraining influences which inform and direct the route to senior leadership. The aim of the research therefore was to bring a light to shine on how women’s experiences are “socially, culturally and politically constructed in specific contexts” (Aspland, 1999, p.110). Thus, an interpretivist framework which sought to explore the central research question “What is the perspective of the aspirant principal cohort on becoming a postprimary principal in the Republic of Ireland?” was employed as the research paradigm. The women in this cohort interpreted the contextual variables informing their career decisions as playing a role in raising their awareness of the experiences they had encountered in the course of their professional and personal lives and the significance of such experiences for their career trajectories.

Cultural Context: Leadership and Career

The dearth of female school leaders across many countries persists despite their numerical advantage within teaching ranks and their successful leadership of teachers at the middle management level (MacRuairc and Harford, 2011). Teachers’ careers are subject to both internal and external forces that act as informing agents in the career decision-making process—accommodating idiosyncratic circumstances that dictate paths chosen or rejected at different junctures throughout the teacher’s professional life. The diverse subjective experiences through which women teachers live act to emphasize different career informing agents at various career junctures which alter as perspectives change to accommodate new realities. Gronn (1999) suggested that those who seek and attain school leadership roles do so as a consequence of their own understanding of what school leadership means—a culturally determined viewpoint—and an appreciation of their own self-efficacy. His genderless hypothesis assumes that males and females experience career similarly, an argument strongly refuted by those scholars who consider that the career paths of men and women tend to be divergent (e.g., Hall, 1996; Coleman, 2005, Coleman, 2011; Eagly and Carli, 2007; McLay, 2008). Coleman (2005) noted the differing influences on male and female principalship aspirants; more females include their families in their decision-making. Women are also more likely to experience a greater variety of middle management positions. Men tend to consider principalship earlier in their careers, consolidating findings that contend that women teachers are less likely to plan their careers (Ibid).

Cultural, structural, institutional, and personal influences all exert pressure to fulfill societal expectations of career and career choice. Ball and Goodson (1985, p.11) noted that “the concept of career must take into account both the objective and subjective aspects of the incumbent’s experience. By definition individual careers are socially constructed and individually experienced over time”. Career routes chosen are affected by, among others, cultural attitudes affecting socialization processes which ensure that women remain subjected to male-dominated workplace practices (Norris and Inglehart, 2000). A true understanding of women’s career trajectories can only be gleaned if the multitudinous layers of influence are recognized and scrutinized (Cubillo and Brown, 2003). In navigating a pathway through all the extenuating circumstances which inhabit the lives of female teachers’ career labyrinths, interpretations remain a constant feature; experiences previously faced can affect how a current situation is perceived or what strategies need to be employed to traverse the current terrain; actions alter as a consequence of previous social engagements and how the individual experienced the encounter; and attitudes too provide useful indicators when attempting to predict outcomes. National culture is a potent force in determining how leadership is understood and who embodies the attributes and talents to execute senior roles within organizations. As Moorosi (2017, p.5) observed “it is perhaps worth acknowledging that the concept of culture in educational leadership has received some attention, albeit not enough”. In examining female career trajectories in educational domains in the Republic of Ireland, Lynch et al. (2012, p.33) concluded that “men have held and continue to hold a disproportionate number of senior posts across all sectors of education”. Following the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922, the established values and ethos of the Catholic Church were placed at the center of a nascent political system. Historical legacies of the church-state relationship, which acted synonymously in determining how schools were governed, who was employed therein, and the focus of curriculum content, assured maintenance of the status quo for many years. “The Catholic Church was well satisfied from the early years of Independence that its educational interests were safeguarded by the administrative and curricular structures of the State” (O’Donoghue and Harford, 2011, p.19). Members of the Catholic clergy-priests, brothers, and nuns occupied many positions within primary and secondary schools especially as teachers and principals; lay people in the same roles did not enjoy the same status; the merging of a Catholic identity with a national identity had a deep and lasting impact on Irish society and was especially restrictive of the role and freedom of women. This extension of the Catholic Church’s jurisdiction consolidated leadership as a male dominion and further relegated women to more subordinate roles. National culture shapes and sways societal expectations of how men and women execute their roles (Gallos, 1989), placing men in more dominant positions such as leadership while relegating women to more submissive positions, thus depicting organizational practices in need of change. At the national level, modes of practice, within and across organizations, are now concentrated on measurable outcomes, and effective schools are ones which attain high standards in these goals. The bureaucratic demands of such policies, along with many facets of principalship, have operated to exponentially increase the workload of school principals thus deterring many women from applying for the position. Eagly and Carli (2007) argued that the microclimates that exist within organizations formulate cultural and social structures that act, whether intentionally or unintentionally, to impede women’s career progress; the long family unfriendly hours do not appeal to many women who take up the mantle of the second shift at home, a place noted by Kellerman and Rhode (2007, p.11) as “being no more an equal opportunity employer than the workplace”. Leadership, in still being seen as a male prerogative (Fitzgerald, 2003; Lumby, 2009), inhibits females at the application stage. It is not that women are seen as being “wrong” for the role, it is just that being a headteacher and a man are synonymous in the eyes of some who make the appointments. Coleman (2005) noted that barriers to principalship accession are prevalent during the selection process; interview panels tend to be male dominated, a consequence of “bringing in attitudes from business and the wider world that impact negatively on women”. National culture, too, acts as a dictate of personal influences which exert pressure to fulfill societal expectations of career and career choice. In observing that the primary observation of a person is in relation to sex, Eagly and Carli (2007, p.85) concluded “classifying a person as male or female evokes mental associations or expectations about masculine and feminine qualities”. The personal element of people’s lives plays an unrecognized part in influencing and determining career paths selected or rejected. In particular, the following act as compelling indicators when considering application for postprimary principalship (Lahtinen and Wilson, 1994; Coleman, 1996; Young and McLeod, 2001; Shakeshaft et al., 2007; Keohane, 2010; Smith, 2011b).

• Gender socialization—

Understanding how socialization affects young males and females, their perceptions of the world they inhabit and the opportunities available to them are relevant to the understanding of who takes up the mantle of leadership and why. Leadership is a position “invested with power” (Eagly and Carli, 2007, p.146), a location not familiar to too many women. Women consciously or unconsciously adapt to societal expectations of their behavior which advocates an occupational status that complies with society’s norms and values, occupying positions which generally do not rival men for power or position (Keohane, 2011).

• Confidence

“Confidence is very important for successful promotion and lack of confidence has been particularly linked to women” (Coleman, 2002, p. 15). Those who lack self-confidence to make the initial steps in application for principalship are defined by Smith (2011b) as protégées who depend on colleagues to highlight their strengths. They exhibit a reluctance to put themselves forward for promotion unless encouraged to do so by more senior members of staff, on whose advice and support they depend for career guidance. In this way, more senior colleagues can be a determining force for the protégée, informing the decision-making process and the ultimate attainment of occupational advancement. Such colleagues can act as informal mentors and offer solace and counsel when applications for principalship have not been successful, thus supplying the impetus for pursuing the desired career objectives even when success seems elusive (Smith, 2011b). At the same time, Smith (2011b) cautions that “by soliciting direction from senior colleagues the protégée to an extent abdicates responsibility for her career development” (p.20), thus not extending her personal agency to its capacity.

• A paucity of mentors and role models

Currently, the roles of mentors and role models are considered to be of great importance to potential school leaders. On this, Coleman (2002) advocated the importance of mentoring and considered the lack of role models for aspiring headteachers to be a critical issue. The proliferation of men in principalship posts at the postprimary level suggests that women need to draw on other sources of inspiration and motivation to encourage career development. Addressing this, Keohane (2011, p. 9) noted that “men are more likely to be mentored in organizations than women and that if senior women are unwilling to assist their younger female colleagues and the men are not sympathetic, you don’t get mentored”. Coleman (2011, p. 63) sums up the imperativeness of this argument for mentors and role models for women when she notes that “mentoring, coaching and the existence of role models are vital tools for the support and development of women who are attempting to access senior positions”.

• Kinship duties to both immediate and extended families

A significant component of any discussion which explores the career opportunities pursued or side-lined by women is that of domestic responsibility (Coleman, 2002; Lumby, 2016; Smith, 2016). Responsibility to those who fall under the remit of “care-dependent” means that many women approach career progression with conflicting emotions; there is, on the one hand, the elation associated with possible newer demands and challenges, in addition to the affirmation evoked on realizing that one is capable of carrying out the associated duties of the new position. However, the flipside of the coin is a reminder of the logistical challenges many women face on their domestic fronts if they are to aspire to or accept leadership opportunities (Kellerman and Rhode, 2007; Keohane, 2010).

Research Design

This research study is concerned with Irish female postprimary teachers who aspire to the post of principal. It is part of a larger study of Irish women and principalship, in addition to the aspirant cohort, those who have acceded to the post of principal including those who have no interest in pursuing principalship as a career objective. The research methodology employed endeavored to explore and examine the career informing agents which support or counteract the career paths of female teachers as they pursue a path to principalship. As a starting point, a statistical audit of the ratio of males to females at principalship in the postprimary sector revealed that the main pattern emerging from the analysis is that, in every rubric, the majority of the principals are male (Department of Education and Skills, 2019). Female representation is 42.7%, accounting for 309 out of 723 principalships across the state.

Selection of the Research Methodology

A qualitative approach was selected, using a life story perspective, as it enabled the researcher to more fully interrogate the multifaceted lives of the study cohort. Its aim was to construct a life story angle on the perspectives the women identify. A qualitative research, as Ballantine and Roberts (2014, p. 40) noted, “allows the researcher to respond to new ideas that come up during the research”, while Charon (2004, p.3) concludes that perspective “is an absolute basic part of everyone’s existence and it acts as a filter through which everything around is perceived and interpreted”. It was vital that the research questions were formulated to permit the interviewees to develop their responses in an open-ended manner, providing them with the opportunity to interpret and make sense of the events and interactions which shaped their viewpoints. The conversations, which focused on the perceived obstacles and perceived enablers which shaped the women’s career paths, were guided initially by the following questions:

a. Their intentions with regard to the principalship and what reasons they gave for holding them

b. What strategies they used with regard to their intentions

c. The significance they attached to their intentions

d. Their intended outcomes following pursuance of their strategies and intentions

Participants

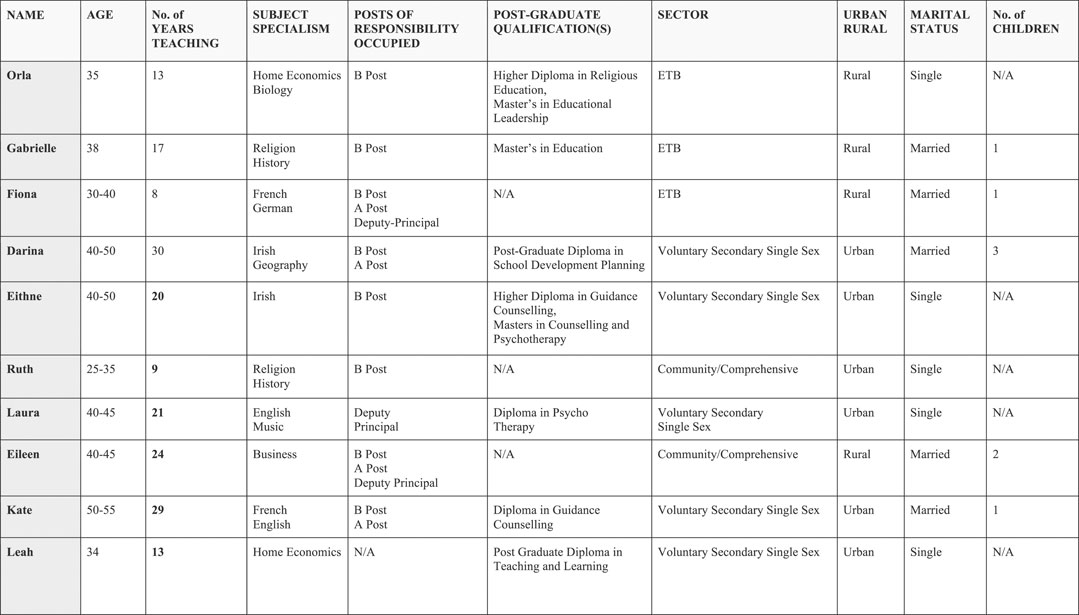

The ten interviewees, whose perspectives are articulated in this study (Figure 1), were difficult to secure; the cohort generally felt uneasy about declaring their interest in applying for principalship and emphasized the need for total anonymity. All respondents, except one, were accessed via advertisements placed in relevant teacher media. Some, on completion of the interview, offered to contact friends or colleagues in professional organizations whom they knew were also seeking principal posts. All interviews took place away from the women’s place of work in an effort to safeguard the promise of anonymity. The women were drawn from the four provinces of the Republic of Ireland (Ulster, Munster, Leinster, and Connaught) and represented all postprimary educational sectors (voluntary secondary, community/comprehensive, and educational and training boards (ETB)). Diversity of school context was also a target to ensure equal representation of all socioeconomic spheres. The respondents desire to become principal was not an initial goal, one that was premeditated and carefully planned, but rather having established themselves in their schools as credible teachers and bedded down as professionals; their attention had turned to using management structures to enhance pupil opportunities. Their motivations for seeking principalship emanated from a range of different perspectives; many of them expressed the centrality of the well-being of their pupils to their lives and their desire to do their best for them. A frustration with the management structure in their schools was also identified by some in this particular cohort as a motivating factor that convinced them to pursue a senior management track and thus be in a position where they could lead effectively and in the best interests of the pupils in their school. Their average age was 41 tallying with the study by Huberman (1989) which noted that some women carve out a career path during the diversification or reassessment phase. This phase, occurring between ages thirty to forty, is, as noted by Sikes (1985), characterized by elevated levels of ambition and self-confidence; “many teachers are at their peak” (p.48). Fifty percent of the women in this cohort of the study are single and have no children. Five are married, three have just one child, one has two children, and one has three children. Of the ten, four had already applied for principalship unsuccessfully. These women qualified as teachers in the years that witnessed a “particularly rapid period of change and transformation in Irish society” (Flood, 2011, p.44). Those women who were at a later stage in their professional careers were a mixture of single and married; those who were married noted that their children were now of an age that more easily facilitated the advancement of their careers, while those who were single noted that any roles undertaken to date or postgraduate courses followed had been taken to enhance their ability to become more effective teachers and/or mentors to their pupils.

FIGURE 1. Aspiring principal cohort. The women in the aspiring cohort had a broad range of teaching experience in an array of subjects but had yet to attain a principalship.

Data Gathering and Analysis

The data were gathered over a period of six months in order to reflect proportionally the cumulative nature of the many tensions shaping the lives of female teachers both in the public and private spheres. The researcher, aware of the many demands that characterize the daily lives of her interviewees, facilitated their schedules—each participant was interviewed in a place of her choosing and at a time convenient for her. All willingly gave of their time in a relaxed and convivial atmosphere as it was important to allow the women scope to express what was important and significant for them. The interviews were recorded on a digital voice recorder and then transcribed. Open coding on three separate occasions followed so as to ensure consistent and accurate reflection of the women’s voices. The researcher was, at all times, conscious of being true to her participants telling of their life stories and the need for trustworthiness of the data collected. Coding the data assisted in the identification of particular emerging themes and permitted focused attention on the relevant aspects of the study, reading, rereading, and listening many times to the recorded interviews familiarized the researcher with the responses and ultimately shaped the analysis.

Impediments and Facilitators

This section presents the findings from the study, evidencing women who demonstrated “a high level of personal agency...able to exert influence and effect change...and they are not discouraged from continuing to seek promotion after making unsuccessful applications” (Smith, 2011a, p.4). However, a significant feature of teachers’ engagement with the study was a concern with privacy. The group members were, by and large, conscious of their self-imposed, although not revealed, disassociation from their colleagues by positioning themselves in what Gronn and Lacey (2004) determined is a “vulnerable space”. Not wanting others to know of their career ambitions was caught up in the idea of failure—should they be unsuccessful in their applications for principal, how then would their colleagues and management perceive them, and how would their career prospects win their schools be altered or reevaluated. The challenges and supports which formed their career decision-making intentions and strategies were identified as perceived obstacles, most notably

• Poor career planning or lack of opportunities for progression

• Poor leadership practices that limit opportunities for colleagues to experience leadership or exercise teacher leadership

• Perspectives that juggling principalship with a family was problematic

And perceived enablers which focused on

• Perspectives on mentors and role models

• Perspectives on supportive partners or families

• Holding posts of responsibility and having further qualifications forming the basis of the data analysis

Perceived Obstacles

Poor Career Planning or Lack of Opportunities for Progression

A career pathway is an established, hierarchical sequence of commonly held positions that leads to increased visibility and scope of responsibility (Ortiz, 1982). Men typically follow a career pathway that moves vertically and directly through the various stages of educational management (Shakeshaft 1989).

Sperandio and Polinchock (2016) noted that the nature of career pathways is a factor contributing to women’s inequitable representation in educational leadership.

Fiona set out to formulate a career path almost from the very beginning of her teaching career.

“My aim always was to, once I got started, work up towards special duties and I suppose eventually assistant principal was in the back of my head. I never had a time frame on it or anything like that but I knew that I would want to look for opportunities to progress within my career… felt that I would like to work towards deputy principalship and I would have been open with my principal and deputy at the time and talk to them about it”. Fiona was keenly aware of what she termed “the quiet encouragement” of the colleagues she worked with along the way who helped her compensate for what she deemed to be the lack of opportunities for progression.

Her evidence contrasts with that of Darina, Eileen, and Kate whose career paths were of a more labyrinthine nature, putting family responsibilities ahead of any professional aspirations. Darina now feels in a position where she can pursue the post of principal without any inconvenience to her family. Her children are now young adults and a lot more adept at tending to their own needs. Her husband, a deputy principal, a post he applied for at Darina’s instigation, has no interest in principalship and is quite happy to support Darina in her ambition.

Women often find themselves clustered into “caring” roles and pastoral roles which can have impact on their perceived suitability for leadership positions (Cubillo and Brown, 2003).

Ruth recalled commencing her career in the area of special educational needs, an area she was quite comfortable in because of her own family background:

How I got involved with special needs was from an early age, from childhood I’ve always been surrounded by special needs, my own sister has spina bifida...I’ve been surrounded with family members with Down’s syndrome, my own cousins have a very rare genetic disease.

Having been unexpectedly given a special needs class while in college in the United States, Ruth found no difficulty in teaching a special needs group. However, her love of special needs and ability to make a difference as a SEN and resource teacher diminished her standing among the rest of the student population. She reflected,

It’s taken a lot of hard work and you know, patience, everything, to establish myself here in the school. Because when I started off here in the school...I was just here for one month doing teaching practice. And so again you were just coming in, the students would have known straight away that you were a student teacher, so they would have changed their names...then when I started out actually teaching here in the school I worked mainly in the resource department so it’s quite hard when you were going into classes maybe to supervise yourself or to discipline on the corridor. I always remember one student passing comment at me one day, he said, but you’re not a teacher here in the school you only work in the SEN department.

Fiona and Ruth’s testimony consolidates the concepts of benevolence and power and how both are distributed within organizations often impeding career strategies for women. Promotional opportunities, on the other hand, are a feature of the male teacher’s professional occupation; when one goal has been attained, the next will be kept firmly in sight. As Sikes (1985, p.48) noted “those, men in particular, who are following the career path, will be working towards major goals, deputy principalship, principalship...the amount of time and energy they devote to their pursuit maybe detrimental to other aspects of their life”.

Poor Leadership Practices That Limit Opportunities for Colleagues to Experience Leadership or Exercise Teacher Leadership

As countries work towards the reform of education systems, the focus has increasingly turned towards the multiple forms of leadership activity in schools (MacRuairc and Harford, 2011). A number of women in this cohort commented on what they viewed as poor leadership practices that limited their opportunities to experience leadership or exercise teacher leadership. Ruth, Orla, and Eileen spoke extensively about their experiences of working with principals who did not evidence good practice. Their desire to accede to principalship was born out of desire to make a difference, to make schools as positive working environments for those who came to school every day. On this, Eithne noted,

I'm not so much interested in the role of principal just to be a principal, that doesn’t really interest me as much as the type of school it is, the philosophy, the ethos of the school and could I work there, could I fit in there kind of thing. It’s really about the children, making a difference to their lives. That’s why I want to be involved at this level.

Many of the women in this cohort, however, felt over-looked and marginalized, aware of opportunities where they could demonstrate leadership but felt they were not being recognized by the leadership in their school, which made them less open to contributing to the larger leadership agenda. Ruth recounted “I had suggested a way of improving communications in the school between management and staff was to get a white board and to put it in the staffroom. And I had mentioned it to one or two staff members, who said it was an excellent idea, you should go and suggest it. So, when I went and suggested it, I was told, oh no, that wouldn’t be possible and I said but why not, it’s something very simple, it’s straightforward, and if it improves communication in the school, then that’s money well spent. That September we came back and lo and behold, the white board was there in the staffroom. But the Deputy Principal told everyone it had been her idea… there was no mention of me”.

Orla too commented on the lack of collegiality and distributed leadership she had encountered and its impact on her feelings about pursuing a leadership route:

I wouldn’t like it if I was myself to pull rank on staff members and make them feel “Well I’m deputy principal I can make this decision over you”, I don’t think that’s fair. You are working with adults, they are all very good, most of them, in their jobs. They are leaders in their own classroom and they are trying to get the best out of students’ management has to get the best out of their team, I do think management should see their staff as a team.

Observing leadership to be an overly administrative, bureaucratic role and not one which stemmed from a teaching and learning nucleus, some interviewees felt the role would take them away from colleagues and from the heartbeat of the school, towards more administrative and largely bureaucratic exercises.

They also alluded to the isolation they perceived and indicated a lack of alignment with how many of their respective principals played out the office of principal. It was clear from the interviews that these women’s perceptions of what constituted leadership and what constituted good leadership practices impacted on their desire to remain invested in pursuing a leadership path.

Perspectives That Juggling Principalship with a Family Was Problematic

Although significant advances have been made in the last decade in the area of legal and policy reform, it is still the expectation that women take responsibility for childrearing (Coleman, 2011; Smith, 2016). As Smith (2016, p.85) noted “powerful social discourses of motherhood continue to find expression in the restrictive parameters within which many women make their life and career decisions”. This is not to suggest that women can and do exert agency (Smith, 2011a), but this agency is typically exercised in challenging contexts, working within particular constraints. As previously noted, fifty percent of the cohort of women in this study do not have children and are not in relationships. Those who have children have relied on childminders, crèche, or family support to accommodate their career ambitions. Fiona, her husband, and her daughter currently live with Fiona’s parents during the week and return to their own family home at weekends. This arrangement permits both Fiona and her husband to pursue their career paths with equal vigor; Fiona’s husband has the same commute time from her parents as from their family home; Fiona is near to school and her parents mind her young son. She noted that when they are back in their own home at weekends, the household chores and child-minding are equally divided among both partners. Gabrielle has availed of a childminder to look after her children since her first child was born. She has three relatively small children and as her school is over an hour’s commute from her home, having someone reliable and consistent has meant that she is able to leave for work in the mornings free from worry about how well her children will be cared for. Comparably, Darina employed a variety of strategies to help cope with the demands of a career and children. She took time off to be with her first child for as she noted,

...my first child was really unwell, very sick, you know in danger of dying initially, so school for me wasn’t very important at the end of my first maternity leave. I said I’d sell my house and live in a caravan. Luckily all that cleared, and I went back. And when I had baby minder number one...she was amazing...then I had a temporary person for two tears who was also very good. It was a filler-in and then I had a third person, which was the real reason I stayed at work. I had her for the last fifteen years.

Ruth commented on the sacrifices she made in her personal life in order to pursue her career:

Even when I was in a long-term relationship for five and a half years, knowing the person ten years, I was extremely career focused, even when I went out with that person. Much to their annoyance at times, to the point that, they would turn to me and say, well when we get married, I'll stay at home and mind the kids and you can continue to work. And I said no, it’s not going to work like that; you’re going to work as well. If you’re in a relationship, you have to think about it carefully in terms of if you have children and family needs. I think sometimes with males, if they are in relationships with families, I think they can sometimes leave that work to the wife.

One of the most over-riding issues to emerge from this cohort, and indeed the other two cohorts, was the acceptance that principalship was not congruent with family responsibilities and that choosing to pursue a principal path would impact on one’s capacity to invest in family life, resulting in compromises and role juggling.

Perceived Enablers

Perspectives on Mentors and Role Models, Including the Significance of Family Members Who Had Worked in Teaching

Commenting on the significance of role models to women, Coleman (2011, p.39) notes that “a lack of female role models is not helpful to women who aspire to leadership”. She also advocates the importance of women-only networks that benefit women in providing informal mentoring and coaching, as well as role models for junior women. Sperandio and Polinchock (2016: 187) noted that having role models whom women could emulate “helped the women assume their leadership roles and develop their aspirations to advance in educational administration”. The women in this study spoke at length about the role models, both professional and personal, who had inspired them along the way. A number commented on their mothers or grandmothers and this key influence in their professional journey. As Smith (2016) noted, motherhood has been and continues to be identified as a major factor influencing women teachers’ and headteachers’ life and career choices.

Orla commented,

My mother was big into education. She believed it was the tool. She always encouraged me to, you know, get on well at my books and in college and she still does to this day. She is delighted if something goes well for me and my father likewise. I came from a background where the money was there to send me to college; I was one of the lucky ones.

Ruth identified her desire to become a teacher as having originated from the influence of her grandmother who instilled in her a long-term intent to make a difference to the lives of young people:

My grandmother was a teacher and I guess that shaped my understanding of the role significantly. I went into teaching because I remember my grandmother recalling stories of when she was a teacher and I was really struck by the way in which she made a huge difference to the lives of pupils particularly around their life changes. Over time, I have grown to just love working with students and kind of getting them to reach their goals. I wanted to teach originally, it started off with PE, then eventually I picked religion and history. I wasn’t one of these people who went and did an arts degree course, I always knew that teaching was always something that I wanted to do, and I had felt very strongly about this from a young age. In particular I wanted to make a difference to the lives of teenagers, just as my grandmother had.

The enduring significance of role models and in particular, female role models for this cohort of women was indisputable.

Perspectives on Supportive Partners or Families

The ties to family obligations, particularly to childrearing, have been cited extensively as an obstacle to women in the pursuit of leadership positions (Coleman, 2002, Coleman, 2011; Kellerman and Rhode, 2007; Smith, 2007; Keohane, 2010; Lynch et al., 2012). As Coleman (2011, p.4) reminds us “family responsibilities are thus identified as one of the main reasons for women’s subordinate positions in the labor force. The other remains the continued stereotyping of women as supportive and subordinate rather than being in charge”.

A number of women in this cohort commented on the importance of supportive partners in allowing them the space to engage with their professional objectives. Gabrielle and Fiona’s husbands both supported their career decisions.

He would just be saying “Go for everything”. He just supports me like he just couldn’t believe I wouldn’t get the job! Gabrielle.

Support from family and partners make it all possible… twenty four seven they’re there for, childcare or anything else and I think even if it wasn’t a case of having the two and a half year old at home, in whatever way they could support us and encourage any of us to further our careers. They would always support us if we were saying we were going for a certain job or thinking about this or that. They’d very much be involved in what we are all doing Fiona.

Both Fiona and Gabrielle employed modification strategies to accommodate their career developments at different junctures:

My husband would have a very good understanding of what I do, of why I have wanted to push myself on over the last few years and he would, you know, the minute I would talk about the special duties role, “Well you’re going to go for that aren’t you”. He’d be very, very supportive in that sense. To the point where, the last couple of years he’s been talking about maybe going back to do some training. He said, “we’ll get you settled and sorted first and then I’ll take my turn when the time comes and when our little boy’s a little bit older”. Fiona

The personal component of people’s lives plays an unrecognized part in influencing and determining career paths selected or rejected. Those for whom the barriers prove problematic do not simply remain impassive, but rather employ strategies to manage their dilemmas.

Holding Posts of Responsibility and Having Further Qualifications

All respondents had sought and attained official posts of responsibility, i.e., management roles within the school for which they received monetary recompense. These roles were perceived by the respondents as necessary constituents of a CV when applying for the position of principal. This had been performed as a desire to “skill-up” in their chosen specialist area or as a means of making themselves more eligible candidates for principalship. There was no single preferred option. Eithne realized very early in her teaching career that her true vocation lay in the area of guidance and counseling. To that end she pursued a Higher Diploma in Guidance Counseling and a B.Sc. in Counseling and Psychotherapy. Darina had completed a Diploma in School Development Planning. She had taken on the direction of a very large-scale project in school and felt that “it would give me some guidance”. It was through guiding and directing the project, for which she had volunteered, that Darina realized that the tasks of principalship were within her capabilities. Fiona, who had attained the most senior management position of all the aspirants, did not as yet hold a postgraduate qualification. Her career path to date had not been impeded by the lack of a postgraduate qualification. This begs the question, is it a box ticking exercise and/or a means of deterring potential candidates from principalship application? Gabrielle commented on the financial difficulties she had experienced due in particular to her husband having been made redundant. She pursued a Postgraduate Diploma in Educational Management in order to make herself more attractive to the gatekeepers. Orla commented on the “hidden qualifications”, through networking that she saw as advantageous to her pursuit of a principalship. She became heavily involved in the local branch of her trade union. Despite the demands it places on her time, she believed the benefits were significant, not least the insights it provided into the working of other school sectors and the sense of confidence it gave her in her own ability to undertake the role of principal:

I am constantly on the phone dealing with people’s problems. I have a lot of communication with schools and with various people working in schools and with HR in the ETB and with area reps to try and sort out problems from that perspective. I have learned an awful lot by being in the union especially about other sectors. In the ETB, there is a lot of people who are principals and deputy principals that have come from adult ed and further education systems. All of this to me is really important, builds my credibility, and shows I know the landscape.

The women in this cohort emphasized that professional development was a priority for them and that they saw the intrinsic value in holding a postgraduate qualification over and beyond their initial degree. They also identified the significance of such professional development opportunities in affording them a greater understanding of the roles they occupied, especially those who were working as guidance counselors. Equally they recognized the necessity of holding such postgraduate qualifications to enhance their eligibility and currency in their ambition to become principal.

Conclusion and Discussion

Aspiring to principalship necessitates resocializing oneself into a space few other people in the staff occupy, placing oneself as Gronn and Lacey (2004) note in a “vulnerable space”. They further note that aspirant principals are likely to be preoccupied with factors to do with ambition, career goals, motivation, what they may want to do and why, and whether or not they believe they “have what it takes’ to do what they want to do”. This research evidenced women who demonstrated “a high level of personal agency...able to exert influence and effect change...and they are not discouraged from continuing to seek promotion after making unsuccessful applications” (Smith, 2011a, p.14).

Key results from this research include the challenges these women experienced integrating into their respective schools, dealing with current management structures and juggling both work and domestic responsibilities. Many of them expressed the centrality of the wellbeing of their pupils and their desire to do their best for them. Five of the ten women in this cohort did not have children and those who did had parents and spouses who were willing accomplices to their career aspirations. The support that the women received from their families enabled them to declare their interest in advancing their careers and to strive to attain their goals, many of which included active pursuance of posts of responsibility and/or engagement in enhancing their resumes via further professional qualifications. Evetts (1994) and Gronn (1999) considered the adoption of coping strategies to assist in the navigation of the career labyrinth. While barriers exist to impede the progress of women in the workplace, many of which have their origins in institutional practices and socially defined cultures; how they are negotiated and/or overcome is not solely dependent on their initiators. In keeping with Smith’ (2011b) results, aligned with the aspiring head teachers she identified as “planners”, this cohort exhibited high levels of self-motivation and a strong awareness of their professional identities. Smith (2011b) further observes that “aspiring women principals are, in their own estimation, self-driven and self-motivated...are motivated by a desire to effect change at a whole school level, are willing to continue applying for promotions after unsuccessful job applications...see career as a very important part of their lives and take strategic approach to career progression” (p.12). The women’s voices evidenced a passion for their profession regardless of circumstance—for many, their decision had been a culmination of numerous experiences that had led eventually to a conscious decision to seek a more senior position, building on their roles and opportunities to date within the schools in which they taught. One of the aspirants, who had worked in the private sector prior to commencing teaching, commented on how “natural” it felt to her to seek additional responsibility, as this would have been the climate in the private sector where she had initially cut her teeth. Another aspirant reflected that her relatively targeted approach to becoming principal was based on a “stepping-stone” framework, developed incrementally and underpinned by a commitment to postgraduate qualification and professional development opportunities. All the women sought or were offered experiences that enhanced their desire to occupy the post of principal. Some of the narratives profiled struggle with integrating into their respective schools and others with current management systems of organization, such as Ruth and Kate whose frustration with senior management practices in their own schools prompted them to plan a career path with principalship as their end goal.

Having children or duties of care to family of origin has been cited by many scholars as a hindrance to full participation in positions of leadership. As Kellerman and Rhode (2007, p.11) insist “women are, and are expected to be, the primary caregivers, especially of the very young and the very old”. Five of the ten women interviewed did not have children; those who did had parents and spouses who were willing accomplices to their career aspirations. The support that the women received from their families enabled them to declare their interest in advancing their careers and to strive to attain their goals, many of which included active pursuance of posts of responsibility and/or engagement in enhancing their resumes via further professional qualifications.

Implications for Practice and Future Research

• Context is crucial to the development of women principals. There is a leadership shortage at the principal level, and to lack the will to support female candidates navigating their career labyrinths is to lack a fundamental sense of pragmatism. Some counties in Ireland have a very uneven ratio of male to female principals. Context in these cases clearly makes a difference—the issue becomes one of what cultural values are being espoused that discourage female teachers from applying for principal positions. Women’s choices take place in a context, not a vacuum. The gendered nature of teaching as a potential extension of the domestic sphere and leadership as a separate locale differentiated by sex, a place where women are numerically disadvantaged, prompted Kate to comment “any male principals I know through any work that I have done have families, like they have a wife and kids, but female principals don’t seem to”.

• Women teachers need mentors and role models. Mentors make a difference to women. Women need support to apply for more senior positions. They need to be intentionally mentored. Mentoring should not be left to chance. While some of the principals in this study who worked in the ETB sector noted the advantage of having access to a variety of principals when they needed advice, others noted their isolation. Principalship can be a lonely position. No other member of staff inhabits that space; therefore, no one truly understands the difficulties and dilemmas of the role within the school. Every school has its own microclimate; so principals, while having similar experiences, work in unique contexts. In the Republic of Ireland, there is currently no mechanism that offers potential candidates for leadership the scope to engage with it prior to applying for a position. This has far-reaching consequences for women teachers; the lack of opportunity to spend time getting to know what principalship is about from within or to engage with programmes with no financial imperative may deter potential candidates from applying. Echoing Fuller (2017, p. 60) who noted the challenges to women’s leadership in England “with respect to policy-making, investment is needed in women’s leadership development in some geographical areas more than in others”.

• Balanced relationships are critical to the career success of partners. If one partner feels that he or she is taking more responsibility for private sphere activities than the other, discontent both at home and in the workplace will replace harmony and order. Societal understandings of sex roles have not altered enough to permit both men and women equal opportunities both at home and in the workplace. Those who toil in the private sphere—mostly women—are often punished for attempting to inhabit both arenas. Two of the women in the study noted the difficulties job-sharing posed when timetables offered facilitated neither work nor home.

• Acknowledging that gender is a fundamental component of human identity—since it informs actions and social practices and leads to internal self-monitoring—is to understand the origins of bias and the implications of it for women who wish to occupy principal positions especially in male-dominated school settings.

• The Department of Education and Skills (DES) needs to be instrumental in modeling equality of access to senior management positions. While the current Minister for Education, Norma Foley, is a woman, six of her ten most senior advisers are men. Schools, as organizations, act as role models for young men and women. Research on gender equity at all levels within Irish education needs support and assistance from the DES so as to garner a diversity of perspectives and grow a talent pool of school leaders which are representative of both genders in society.

Crossing the bridge to leadership is more problematic for women than for men as the hurdles are more numerous and often present with greater frequency.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the School of Education, University College Dublin. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable data included in this article.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Additional Points

The purpose of this research is to explore the relationship between gender and educational leadership with a specific focus on examining the informing agents which act as determinants of the career paths of female teachers. As this is a relatively under-researched area in the Republic of Ireland and a growing international phenomenon, it is imperative that the career paths of those who aspire to principalship are explored and scrutinized so as to identify the enablers and obstacles that support or hinder their career ambitions. It is only in doing so, in addition to identifying the contextual constructs encountered by the women, that their road map can take on a less labyrinthine configuration and become more conducive to supporting their professional goals.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Aspland, T. (1999). A research journey: struggling with the evolution of a methodological pastiche. Educ. Res. Perspect. 2 (26), 105–126.

Ballantine, J. H., and Roberts, K. A. (2014). Our social world - introduction to sociology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Charon, J. M. (2004). Symbolic interactionism: an introduction, an interpretation, an integration. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Coleman, M. (1996). Barriers to Career progress for women in education: the perceptions of female headteachers. Educ. Res. 38 (3), 317–332. doi:10.1080/0013188960380305

Coleman, M. (2003). “Gender and educational leadership,” in Leadership in education. Editors M. Brundett, N. Burton, and R. Smith (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 36–54.

Coleman, M. (2005). ‘Gender and headship in the twenty-first century’. Project report. Nottingham, England: National College for School Leadership.

Cubillo, L., and Brown, M. (2003). Women into educational leadership and management: international differences? J. Educ. Admin. 41 (3), 278–291. doi:10.1108/09578230310474421

Department of Education and Skills (2019). Post-primary school statistics. Available at: https://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Statistics/Data-on-Individual-Schools/.

Eagly, A. H., and Carli, L. L. (2007). Through the labyrinth. Brighton, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing.

Fitzgerald, T. (2003). Changing the deafening silence of indigenous women's voices in educational leadership. J. Educ. Admin. 41 (1), 9–23. doi:10.1108/09578230310457402

Fitzgerald, T. (2014). Women leaders in higher education: shattering the myth. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Flood, P. (2011). “Leading and managing Irish schools: a historical perspective,” in Leading and managing schools. Editors H. O’Sullivan, and J. West-Burnham (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 43–58.

Fuller, K. (2009). Women secondary head teachers. Manag. Educ. 23 (1), 19–31. doi:10.1177/0892020608099078

Gallos, J. (1989). “Exploring women’s development: implications for career theory, practice and research,” in Handbook of career theory. Editors M.B. Arthur, D. T. Hall, and D. Rousseau (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press), 110–132.

Gronn, P., and Lacey, K. (2004). Positioning oneself for leadership: feelings of vulnerability among aspirant principals. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 24 (4), 405–424. doi:10.1080/13632430410001316516

Gronn, P. (1999). The making of educational leaders. Management and leadership in education. London, United Kingdom: Cassell.

Hall, V. (1996). Dancing on the ceiling: a study of women managers in education. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kellerman, B., and Rhode, D. L. (2007). “‘Women and leadership: the state of play’ in kellerman,” in Women and leadership: the state of play and strategies for change. Editors B. Kellerman, and D. L. Rhode (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 1–64.

Keohane, N. O. (2011). “The future of women’s leadership,” in Address to rhodes scholars. Oxford, United Kingdom: Rhodes House.

K. Lynch, B. Grummell, and D. Devine (Editors) (2012). New managerialism in education: commercialisation, carelessness and gender. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lahtinen, H. K., and Wilson, F. M. (1994). Women and power in organizations. Executive Dev. 7 (3), 16–23. doi:10.1108/09533239410058828

Lumby, J. (2016). “Culture and otherness in gender studies: building on marianne coleman’s work,” in Gender and leadership: women achieving against the odds. Editors K. Fuller, and J. Harford (Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang), 83–114.

Lumby, J. (2009). Collective leadership of local school systems. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 37 (3), 310–328. doi:10.1177/1741143209102782

MacRuairc, G., and Harford, J. (2011). “Teacher leadership: awakening the sleeping giant,” in Beyond fragmentation: didactics, learning and teaching. Editors B. Hudson, and M. Meyer (Leverkusen, Germany: Verlag Barbara Budrich), 205–220.

McLay, M. (2008). Headteacher career paths in UK independent secondary coeducational schools. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 36 (3), 353–372. doi:10.1177/1741143208090594

Moorosi, P. (2017). “Overview :the status of women in educational leadership: global insights,” in Women leading education across the continents: finding and harnessing the joy in leadership. Editors R. McNae, and E. Reilly (Lanham, MD: Rowan and Littlefield), 3–7.

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2000). Cracking the marble ceiling: cultural barriers facing women leaders. A Harvard University Report.

O’Donoghue, T., and Harford, J. (2011). A comparative history of church-state relations in Irish education. Comp. Educ. Rev. 55 (3), 315–341. doi:10.1086/659871

Ortiz, F. I. (1982). Career patterns in education: women, men and minorities in educational administration. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Shakeshaft, C., Browne, G., Irby, B. J., Grogan, M., and Ballenger, J. (2007). “Increasing gender equity in educational leadership,” in Handbook for achieving gender equity through education. 2nd Edition, Editor S. Klein (New Jersey, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 105–130.

Sikes, P. (1985). “The life cycle of the teacher,” in Teachers’ lives and careers. Editors S. J. Ball, and I. F. Goodson (London, United Kingdom: The Falmer Press), 27–60.

S. J. Ball, and I. F. Goodson (Editors) (1985). Understanding teachers: concepts and contexts. Lewes: The Falmer Press.

Smith, J. (2011a). Agency and female teachers' career decisions: a life history study of 40 women. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 39 (1), 7–24. doi:10.1177/1741143210383900

Smith, J. M. (2007). Life histories and career decisions of women teachers unpublished doctoral thesis. West Yorkshire, United Kingdom: University of Leeds.

Smith, J. M. (2011b). Aspirations to and perceptions of secondary headship: contrasting female teachers' and headteachers' perspectives. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 39 (5), 516–535. doi:10.1177/1741143211408450

Smith, J. M. (2016). “Motherhood and women teachers’ career decisions: a constant battle,” in Gender and leadership: women achieving against the odds. Editors K. Fuller, and J. Harford (Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang), 83–114.

Sperandio, J., and Polinchock, J. (2016). “Roads less travelled: female elementary school principals aspiring to the school district superintendency,” in Gender and leadership: women achieving against the odds. Editors K. Fuller, and J. Harford (Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang), 175–207.

Keywords: teachers’ lives, gender, career, leadership, challenges, supports

Citation: Cunneen ME (2021) Crossing the Bridge to Leadership: Exposing Ambition Among Challenges. Front. Educ. 6:532253. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.532253

Received: 03 February 2020; Accepted: 25 January 2021;

Published: 22 March 2021.

Edited by:

Victoria Showunmi, University College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Catherine Ann Simon, Bath Spa University, United KingdomElizabeth C. Reilly, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Copyright © 2021 Cunneen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mary Elizabeth Cunneen, bWFyeS5jdW5uZWVuQHVjZC5pZQ==

Mary Elizabeth Cunneen

Mary Elizabeth Cunneen