- 1Department of Educational Leadership, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, United States

- 2Department of Instructional Leadership and Professional Development, Towson University, Baltimore, MD, United States

- 3Department of Educational Leadership and Policy, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, United States

- 4Department of Educational Leadership and Policy, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, United States

Utilizing a sample of 54 interviews from a larger study of traditional public school principals' responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, we examined the degree to which principals in 19 states and representing both urban (e.g., intensive, emergent or characteristic; n = 37) and suburban settings (n = 17) and across all student levels (i.e., elementary, middle, and high), experienced and engaged in behaviors to create psychological safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. We also sought to understand how various environmental and organizational features may have influenced these conditions and thus the likelihood of learning taking place. We find principals reported varied levels of psychological safety in their schools with associated differing levels of organizational learning and responsiveness to the crisis. However, rather being grounded in environmental conditions (e.g., urbanicity, demographics, etc.), organizational factors and specifically, differences in accountability, principal autonomy, professional culture and teacher decision-making were all key in the degree of psychological safety exhibited. Together, these findings serve to expand understanding of leadership as creating conditions for learning and give insight into the degree our pre-COVID-19 system may have facilitated or stymied the ability or capacity of school leaders in different settings to support transformational learning. In this way, this research may have real and important implications for the types of support leaders and teachers require as we collectively transition into the next phase of uncertainty as many schools continue to try and re-open safely and all that lays ahead.

Introduction

While there are many striking aspects to the COVID-19 pandemic, the scale and rapidity with which educators had to respond to school closures and fundamentally shift all aspects of their work is unparalleled. School principals, tasked with leading this transition, were thrust into the role of helping faculty, staff, students, and families learn how to effectively “do school” in a highly uncertain and ever-changing environment. In this way, they were positioned to become what we might deem a “chief learning officer,” creating conditions to encourage staff to “unfreeze” (Schein, 2010) and learn new ways of serving their students’ and communities’ evolving needs. If ever there was a time and need for principals to work with teachers to engage in “higher” (Fiol and Lyles, 1985), “generative” (Senge, 1990), “strategic” (Dodgson, 1991), or what Argyris (1977, 1982) called “double loop learning,” it was seemingly during this time.

Such leadership does not exist in a vacuum; as Argyris (1977, 1982) points out, leaders must create conditions so organizational members can examine underlying assumptions regarding current practice and facilitate opportunities for new ways of thinking and doing. These efforts may be particularly necessary during times of crisis, as research indicates it is in these times of heightened ambiguity and uncertainty that we need school leaders to be oriented toward learning and create structures and systems for creative problem solving and innovation (Wooten and James, 2008; Smith and Riley, 2012). And yet, it is important to note that schools and school systems, often based on their geographic location (e.g., urban, suburban, rural, etc.), had far from equitable organizational conditions regarding their resources, performance, and vulnerability to systems of oppression (e.g., the impacts of structural racism, poverty, etc.; Kotok et al., 2017) before the pandemic started. For example, in 2017, the percent of students receiving free and reduced price lunch in suburban schools (43%) was ~20 percentage points lower than in urban schools (63%), and 15 percentage points lower than in rural schools (58%) with parallel discrepancies in student performance between suburban students and their counterparts in urban and rural settings (Logan and Burdick-Will, 2017). These disparities were felt in, and continue to shape, the impact of and response to COVID-19, with data pointing to the disproportionate lives and livelihoods taken from Black and Brown communities (Oppel et al., 2020)—still most often concentrated in urban centers (Parker et al., 2018).

Therefore, besides the clear need to attend to such injustices, these disparities also signal the different levels of uncertainty and strain schools with varied organizational conditions faced as they responded to the pandemic and learned. At the same time, research indicates that organizations most able to learn, and thus respond more effectively to crises (Wooten and James, 2004), are those in which the leader best utilizes the efforts and skills of their workforce to adapt to changing conditions and perform under pressure (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990; Dodgson, 1993). However, as organizational scholars point out (Argyris, 1982; Schein, 2010; Edmondson and Lei, 2014; Weiner, 2014), environmental pressures can make organizational learning more difficult and increase the need for leaders, and school leaders in particular (Edmondson et al., 2016), to foster a culture of learning. The question, of course, is to what degree school principals were able to fulfill this role. Were they able to, for example, create the types of learning environments which Garvin et al. (2008) describe as being places where people can feel safe to take risks, make mistakes, and learn?

This sense of “psychological safety” (Edmondson, 1999), defined as the degree to which people view the environment as conducive to interpersonally risky behaviors like speaking up or asking for help, impacts the degree to which individual and organizational learning can occur (see Edmondson and Lei, 2014 for a review). Research shows that even when people want (and like educators now, perhaps need) to change their practice, the perceived risks of such change may inhibit their ability to do so (e.g., Wanless et al., 2013). Research applying psychological safety to schools (see 2016 special issue in Research in Human Development for an overview), paints a complex portrait in which traditional professional norms, mixed leader effectiveness, and the high stakes nature of the work make creating a culture of psychological safety both critically important and extremely challenging to achieve (Edmondson et al., 2016; Weiner, 2016).

Utilizing a sample of 54 interviews from a larger study of traditional public school principals’ responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, we explore these issues directly. Specifically, we examined the degree to which principals in 19 states and representing both urban (e.g., intensive, emergent or characteristic; Milner, 2012) (n = 37) and suburban settings (n = 17) and across all student levels (i.e., elementary, middle, and high), experienced and engaged in behaviors to create psychological safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. We also sought to understand how various environmental and organizational features may have influenced these conditions and thus the likelihood of learning taking place.

We find principals reported varied levels of psychological safety in their schools with associated differing levels of organizational learning and responsiveness to the crisis. However, rather being grounded in environmental conditions (e.g., urbanicity, demographics, etc.), organizational factors and specifically, differences in accountability, principal autonomy, professional culture, and teacher decision-making were all key in the degree of psychological safety exhibited.

Together, these findings serve to expand understanding of leadership as creating conditions for learning and give insight into the degree our pre-COVID-19 system may have facilitated or stymied the ability or capacity of school leaders in different settings to support transformational learning (Drago-Severson and Blum-DeStefano, 2014). In this way, this research may have real and important implications for the types of support leaders and teachers require as we collectively transition into the next phase of uncertainty as many schools continue to try and re-open safely and all that lays ahead.

Literature Review

School Leader as Chief Learning Officer: Supporting Educators' Learning

Schools, like all organizations, must continually adapt to shifting environmental demands to remain effective (Levitt and March, 1988; Cohen and Levinthal, 1990; Dodgson, 1993). Indeed, schools have long been called upon to become “learning organizations” in which educators are pushed to continually change and learn (see Giles and Hargreaves, 2006 for a review). In this context, organizational learning is defined as “the development of new insights and understandings that have potential to influence behavior” (Hesbol, 2019, p. 35). This includes, according to Marsick and Watkins (1999), system-level learning that is continuous and facilitates enhanced knowledge, skills, and performance. One key outcome associated with schools operating as learning organizations is their ability to best serve students’ evolving needs and facilitate their success in our changing society and world (Schlechty, 2009).

As highlighted by Harris and Jones (2018), the conceptualization of schools as learning organizations finds its origins in the 1980s, with Argyris's (1982) focus on the process of organizational learning, and double-loop learning specifically, as a key mechanism for ensuring organizational efficiency and effectiveness. With the work of Senge (1990), this framing—that part of the essential work of schools is to support the adults therein (e.g., administrators and teachers) in collectively learning how to enhance their practice—gained popularity and prevalence (Paraschiva et al., 2019). It also produced detractors, with some arguing the concept is too broad and/or amorphous (Field, 2019), as well as those questioning whether the concept adequately attends to the more informal relationships and social networks shown to be necessary conditions for learning and change (Giles and Hargreaves, 2006). However, and despite what some may consider unresolved questions regarding these critiques, the concept of schools as learning organizations has again recently gained traction in research and practice alike (Kools and Stoll, 2016; Harris and Jones, 2018) and, as we argue here, can be useful in thinking about the work of schools in adapting to changing environmental conditions generally, and in crisis situations like that of COVID-19, in particular (Wooten and James, 2008; Smith and Riley, 2012).

By centering organizational learning and its role in facilitating schools' ability to successfully respond to environmental uncertainty, we can then understand a school leader's key role in creating conditions to support individual and collective learning (Leithwood et al., 2017; Harris and Jones, 2018; Robinson, 2018). In particular, scholars focused on schools as learning organizations often call upon school and district leaders to attend to ensuring school structures, systems and culture facilitate learning (e.g., Giles and Hargreaves, 2006; Fullan, 2010; Kools and Stoll, 2016). For example, research shows that leaders can facilitate organizational learning through building communities of practice (Wenger, 1998) and professional learning communities specifically (Bowen et al., 2007; Weiner, 2014; Meyers and Hambrick Hitt, 2017). Additionally, a clear compelling vision, theory of action (Dimmock, 2012), and means of effectively communicating information across the organization all support learning, particularly in times of uncertainty (Thompson, 2017; Harris and Jones, 2018; Paraschiva et al., 2019) and crisis specifically (Wooten and James, 2008; Smith and Riley, 2012).

Another important way school leaders can support organizational learning is by attending to the professional culture (Hallinger, 2011; Harris et al., 2013) and ensuring it is positive, promotes teacher collaboration, and cultivates a feeling amongst teachers that they are supported and respected in their efforts (e.g., Harris et al., 2015). This work of sustaining a professional culture needs to be explicit and frequently attended to as schools' default cultures are traditionally grounded in norms of teacher egalitarianism, autonomy (i.e., isolation), and seniority (Donaldson et al., 2008; Imants et al., 2013; Weiner, 2016) as well as hierarchical governance (Weiner, 2014)—all norms that can hinder collective learning and growth (Edmondson et al., 2016).

Additionally, given the prevalence of accountability pressures grounded in neo-liberal reforms (Weiner, 2020), to create a culture in which teachers feel they can innovate and learn often requires school leaders to buffer teachers from such pressures (Dworkin and Tobe, 2014; Cosner and Jones, 2016). Facilitating trust and a sense of internal or collective accountability in which teachers hold one another to shared expectations for meeting students' needs (Elmore, 2007; Sahlberg, 2010) are key to school leaders' efforts to enhance teachers' willingness to try new things and learn (Bryk and Schneider, 2003; Wahlstrom and Louis, 2008). Finally, and the core focus of the current research, is the need for principals to create a culture in which teachers feel safe to speak up and take interpersonal risks to facilitate learning (Le Fevre, 2014; Edmondson et al., 2016), in other words, to establish a sense of psychological safety (Edmondson, 2003).

Theoretical Framework: Psychological Safety

Psychological safety (PS) is an element of organizational culture that, as Schein and Bennis (1965) articulated over 50 years ago, supports those working within the organization to move away from default ways of doing and thinking and learn, innovate, and grow (i.e., unfreeze) and serves as one of the critical “building blocks of organizational learning [that] reinforce each other” (Garvin et al., 2008, p. 5). As more recently articulated by Edmondson (2003), we can understand PS as the “degree to which people perceive their work environment as conducive to taking… interpersonal risks” (p. 257). In this framing, interpersonal risks are those directly associated with the work of the organization and are activities that might make the actor vulnerable to professional critique, for example, if they were to speak up regarding an issue with current practice, ask for help, or admit mistakes (Edmondson and Lei, 2014; Walters and Diab, 2016). Again, as pointed out by Higgins et al. (2012), PS is one of multiple dimensions of organizational learning that needs to be simultaneously attended to build a robust culture ready and able to engage in meaningful, positive learning and change. When PS is present, in such environments, it can promote collective learning and change toward the incorporation of new behaviors that improve individual and organizational performance (Edmondson et al., 2001; Morrow et al., 2010) as well as increased voice and satisfaction (Frazier et al., 2017; Newman et al., 2017). When PS is absent, individuals will work to manage the risks of speaking up by, for example, avoiding challenging or difficult conversations with one another or leaders and thus, losing opportunities for learning and growth (Detert and Edmondson, 2005).

PS allows us to differentiate between a culture of collegiality or care where people may feel comfortable but are perhaps not pushed to learn and change and a context in which people feel supported to engage in the “risky behavior” of learning. As Helsing et al. (2008) make clear, adult learning includes loss as people, individually and collectively, let go of familiar ways of navigating the world and cross into new and unchartered territories, and hence, engage in risk-taking. At the organizational level too, real learning often requires collective engagement in the risk of moving away from known, and oftentimes inhibitory, ways of behaving and understanding the work to a better but unknown future (Argyris, 1982). Thus, and aligned with this understanding that learning—whether at the individual or organizational level—involves risk, those who study PS are clear that while the goal is to create a positive environment for learning, it must also come with push via elements such as a compelling vision for change (Schein, 2010) and a rewards and discipline system (i.e., accountability; Higgins et al., in press) clearly articulated and aligned with desired learning outcomes (Knapp and Feldman, 2012). As Schein (1999) explains, the goal of PS is not to remove all external pressures or learning anxiety, rather, it is to mitigate that anxiety so it is productive.

The key to effective change management, then, becomes the ability to balance the amount of threat produced by disconfirming data with enough psychological safety to allow the change target to accept the information, feel the survival anxiety, and become motivated to change. The true artistry of change management lies in the various kinds of tactics that change agents employ to create psychological safety. For example, working in groups, creating parallel systems that allow some relief from day to day work pressures, providing practice fields in which errors are embraced rather than feared, providing positive visions to encourage the learner, breaking the learning process into manageable steps, providing on-line coaching and help all serve the function of reducing learning anxiety and thus creating genuine motivation to learn and change (p. 61).

Given its role in helping organizational members cope with learning anxiety associated with normal levels of change, it is perhaps no surprise that scholars have long identified PS as especially important in organizations with work, like that which occurs in health care and schools, that is high stakes, complex, and often under high levels of public scrutiny (Edmondson et al., 2001; Nembhard and Edmondson, 2006; Weiner, 2014; Higgins et al., in press). Therefore, and relevant for the current study, we might understand PS as a necessary organizational condition during periods of crisis—such as the COVID-19 pandemic—in which organizational members, in this case educators, may need to learn and change quickly.

While PS has only recently been applied to the educational context (e.g., Wanless, 2016), there is strong transferability of the concept to schools and the need for teachers to feel safe to engage deeply and authentically about their practice and learn (Edmondson et al., 2016). There are also insights to be gleaned from the research outside education regarding the organizational conditions that leaders create to support or hinder PS in practice. For example, research suggests that when organizations are more hierarchical and work is more discreet than interdependent (Edmondson, 1999), less PS may be present (Nembhard and Edmondson, 2006). In contrast, when employees have the authority to make important decisions and are clear about what is and is not their job, it supports PS (Frazier et al., 2017). Reward and discipline systems too can impact PS in terms of their degree of alignment with supporting learning and the vision of improvement (Schein, 2010; Stragalas, 2010), as well as whether they are shared or individually oriented (Newman et al., 2017).

A leader's effectiveness is also shown to enhance PS (Frazier et al., 2017). This includes their ability to build strong, respectful, and supportive relationships with, and among, those in the organization (Zhang et al., 2010; Singer et al., 2015) and to engage in clear and transparent information sharing with individuals (e.g., Siemsen et al., 2009) and the larger group (Bunderson and Boumgarden, 2009). Additionally, leaders must work against hierarchical structures to reduce status gaps (Nembhard and Edmondson, 2006) and promote the idea that all community members have ideas with value and import, skills also critical in times of crisis (Smith and Riley, 2012). Connected to this point, the leader too must be willing to present themselves as fallible and invite, rather than repel, dissent (Roberto, 2002; Newman et al., 2017). While these are but a few ways leaders can use to facilitate psychological safety, together they illustrate the need for leaders to attend to PS in their work to ensure that organizational members can productively respond to change and learn, especially in times of crisis.

Methods

We employ a basic interpretive design (Merriam, 2002) focused on facilitating opportunities to understand how individuals interpret, construct, or make meaning of their world and experiences (Creswell and Poth, 2018). As per Kahlke's (2014) description that this design supports drawing on multiple methodologies, we pulled on traditions of phenomenology and its focus on examining participants' lived experiences through their descriptions, stories, and narratives (Moustakas, 1994) and embraced approaches typically deployed in organizational studies in which participants' descriptions are used to examine organizational routines, resources, and policies (Nowell and Albrecht, 2019).

Sample

Data for this analysis come from a large qualitative study of principal leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. During the spring and summer of 2020, a cross-institution team of 18 researchers, including this study's authors, conducted interviews of 120 school leaders in 19 states. Researchers used their social and professional networks to each recruit seven public school principals (2 at each of the elementary, middle, and high school levels and one other) working in traditional public schools. The result was a large and heterogeneous sample with variability across features like school size, demographics, location, and performance level. All authors were involved in all stages of the data collection—from protocol development to interviews to transcription.

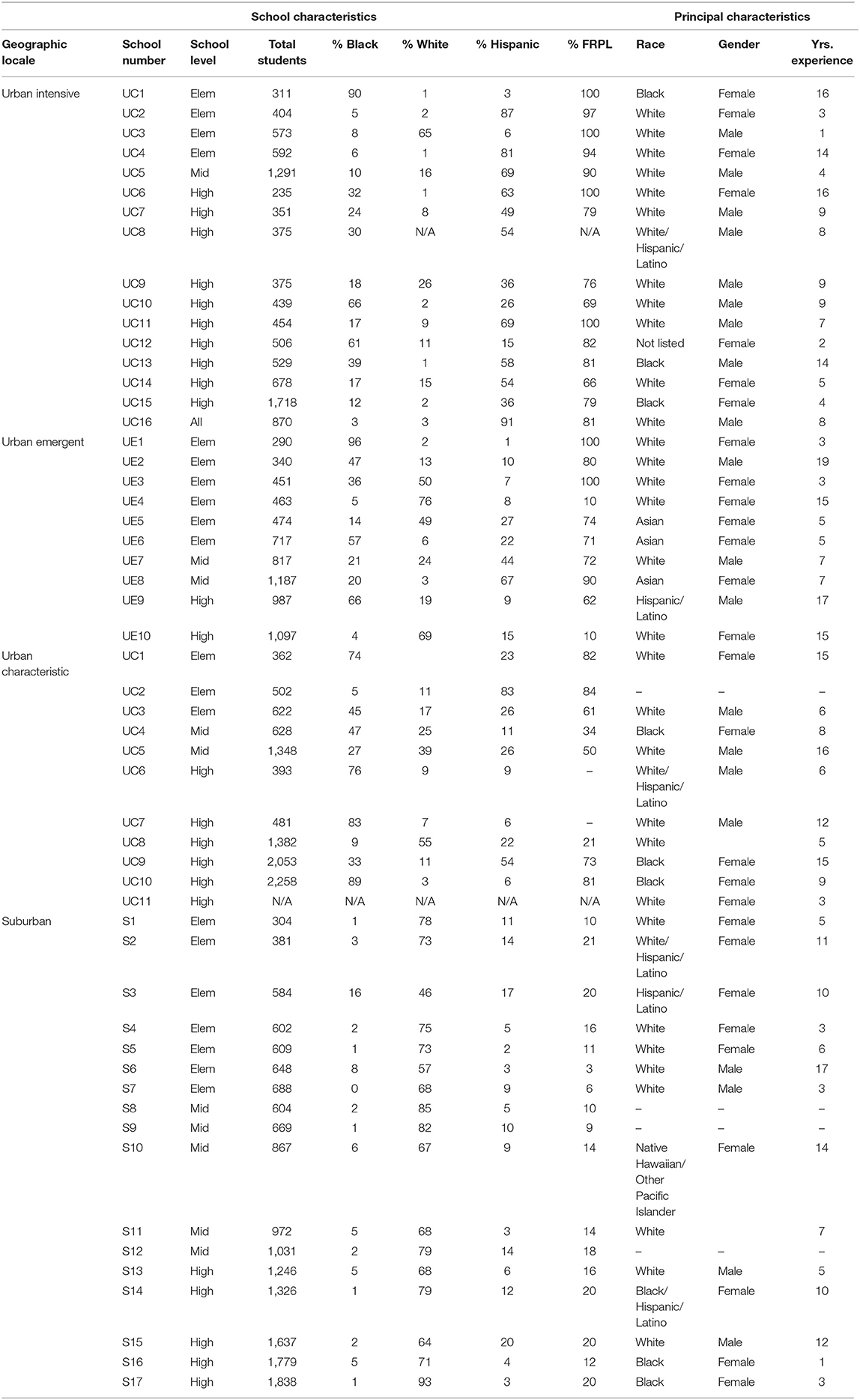

We created a sub-sample of 54 schools on which to focus our efforts. Guided by Milner's (2012) framework regarding the designation of “urban” schools as intensive, emergent, or characteristic, we identified schools that were: (1) in cities of over 1 million people (n = 16) (urban intensive), (2) in cities with <1 million people but more than 400,000 residents (n = 10) (urban emergent), and (3) those that were urban characteristic (n = 11), what Milner says are schools “not located in big or mid-sized cities but may be starting to experience some of the challenges that are sometimes associated with urban school contexts in larger areas” (p. 559) such as the proportions of English language learners or those receiving free and reduced priced lunch. As Milner points out, these schools may not geographically be placed in cities. As a contrast to this sample, we also selected schools considered suburban (n = 17) via the census and had <25% of students receiving free and reduced-price lunch (the U.S. DOE's designation of a low poverty school). Please see Table 1 below for more information regarding the demographics of the schools and their principals.

Data Collection

We used interviews as our primary source of data (Hunt, 2009). Upon agreeing to participate, principals were sent a consent form and a survey of their and the school's demographic information. Information regarding the closure policies and, if available, emergency response plans were collected as was data from the census regarding the school's community demographics.

The interview protocol was co-constructed by the researchers and asked the principals to reflect from the time immediately before school closure to the present. Principals were asked how issues as broad as familial engagement to self-care, to how and by whom decisions regarding instruction were made. While the protocol was not directly geared to psychological safety, there was strong overlap between many of the questions regarding organizational conditions and principal behaviors and the framework. Finally, interviews occurred one time, were conducted online, and ranged from 45 min to almost 2 h in length. All were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

In keeping with a basic interpretative approach, we employed thematic analysis (Boyatzis, 1998). To build our codebook we supplemented Schein's (2010) work highlighting the necessary conditions for PS along with other empirical work on this topic and the outcomes (e.g., learning, staying together, meeting external performance criteria, etc.) associated with its presence (e.g., Frazier et al., 2017). Codes included topics such as “infrastructure for teacher collaborative decision-making” and “principal engages in relationship building behaviors” and were oriented toward identifying gradations in implementation. In addition to our thematic coding, we gave an overarching rating to the degree of PS including its associated outcomes that seemed present in the school via the principal's recollections.

As a first stage of the work, we randomly selected a group of 6 interviews to collectively code and discuss. The conversation built intercoder reliability and enhanced the applicability and utility of the codebook. We thus saw our process as mirroring Hruschka et al.'s (2004) in building intercoder reliability: the segmentation of text, codebook creation, coding, assessment of reliability, codebook modification, and final coding.

Once revisions were made to the codebook, the team proceeded coding the rest of the sample, including re-coding the 6 from the first round. Each team member coded a number of interviews individually and provided designations regarding the level of PS that appeared to be present. At regular intervals, team members would double or triple code a group of interviews and then discuss the results with team members. This meant more than half the interviews were at least double coded. These processes helped maintain reliability and facilitated opportunities for team members to reflect on emergent findings and their connection to the sample writ large.

After the initial coding was completed, team members reviewed the school designations and worked to ensure collective agreement regarding how these schools were coded, why, and the assessment of their overall level of psychological safety. The resultant conversation moved the team to consolidate from five categories of the degree of PS we observed as present in the school (low, low/moderate, moderate, moderate/high, high) to three (low, moderate, high). This required redistributing a number of schools through a negotiated collective process. Finally, team members revisited transcripts of those representative of low vs. high PS to determine salient features related to our coding that appeared pivotal in their positioning on the continuum and will be discussed further in the findings section.

Limitations

This research is not without limitations. First, as this research took a holistic orientation to capturing principals' and their schools' experiences at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was not specifically designed to examine PS in schools. Second, the data collection was limited to the principal's views and recollections; we did not conduct interviews with others in the school community or observe their behaviors in situ. As a result, we were unable to gather information regarding other dimensions of might of professional culture, organizational learning, and/or teacher decision-making or how these dimensions may potentially interact with PS in situ to create support or hinder adaptation, learning, and thus responsiveness to students and communities evolving needs. Finally, though we worked to construct a sub-sample for our analysis that was appropriately representative of the phenomenon of interest—the presence of PS in schools with differing levels of environmental uncertainty at the onset of the pandemic—the original sample was not constructed for this purpose. Rather it was a convenience sample created as a result of researchers' networks, and thus shaped the representativeness of our sample in terms of how many, which types and the location of the urban and suburban schools we were able to include in our sample. With all that said, and given the critical need to mobilize to capture principals' experiences with COVID-19 in a timely manner, we feel the contributions of this work outweigh its limitations.

Findings

The purpose of this study was to understand how principals experienced and engaged in behaviors to create PS during the COVID-19 pandemic, and how their varied environmental and organizational context may have influenced these conditions. As we will discuss shortly, we find principals reported varied levels of PS in their schools and these were associated with different levels of organizational learning and responsiveness to the crisis. These differences were also grounded in varied organizational conditions such as the way accountability was meted out, the degree of principal's autonomy, the organizational culture, and the degree of educational infrastructure available to support teachers' collective decision-making. However, before we dive into a detailed discussion of these findings, we spend some time exploring the environmental conditions of the sample relative to their identified levels of PS.

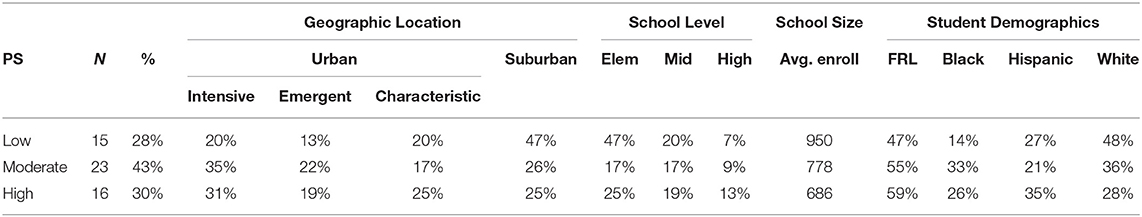

Distribution of Psychological Safety Across Environmental Contexts

As highlighted in Table 2, we explored the distribution of the sample relative to the degree of PS we coded as being present (i.e., low, moderate, high) and the school's geographic location (i.e., urban intensive, urban emergent, urban characteristic, or suburban), size as well as some elements of the demographic makeup of the student body. While these numbers are purely descriptive, they provide some early insights into how and in what ways environmental elements of the schools may be related (or not) to the principal's ability to foster a culture of psychological safety.

As highlighted in the table, the distribution of our rankings for the degree of PS in a given school was fairly even across the sample. We characterized 43% of the schools as exhibiting moderate PS, 28% of schools as having low PS, and 30% as exhibiting high levels of PS. When we then looked at the environmental conditions for each group we find, in regards to geographic location, that 47% of those schools ranked as exhibiting low PS were located in suburban areas. In contrast, 31% of the schools ranked as having high PS were in urban intensive areas. This suggests geographic location may be a less powerful predictor of PS than perhaps imagined given the environmental uncertainty often thought to be associated with urban locations.

Shifting to school level, size, and demographics, first, elementary schools comprised almost half, 47%, of the schools with low PS. The rest of the school-types (middle, high) were more evenly distributed across the rankings. Bigger schools tended to be ranked as having lower levels of PS and vice-versa. Schools ranked with the highest levels of PS also, on average, served the highest percentage (59%) of students receiving free and reduced-price lunch when compared to schools ranked with the lowest levels of the construct. Finally, schools with low PS ratings also had the highest percentages of white students. Schools rated more highly regarding PS tended to serve larger percentages of Hispanic students (average 35%), while schools rated as having moderate PS served the largest percentage, on average, of Black students (33%).

Taken together, the distribution of the differently rated schools across these environmental conditions suggests conditions traditionally associated higher levels of uncertainty (e.g., urbanicity, percent of students in poverty, etc.; Kraft et al., 2015), do not seem strongly concentrated in any one of our ratings of PS. Moreover, as pointed out by other researchers (e.g., Johnson et al., 2012; Simon and Johnson, 2015) teaching in a school with more Black and brown students (i.e., an environmental condition often due to housing discrimination and schooling patterns) is less of a factor in shaping educator's views of the working conditions than the organizational features within a given school. Indeed, it was suburban schools, with lower levels of poverty and more white students, that were more likely to be rated as having low levels of PS. Therefore, and while the confirmation of such findings requires further and more rigorous statistical analysis, our observations regarding these environmental features suggest the answers regarding differences in their degree of PS may be more rooted in organizational than environmental features. In the following, we provide insights into our investigation of the shared organizational conditions of schools with differing degrees of PS as a first step toward better understanding where these differences may lie.

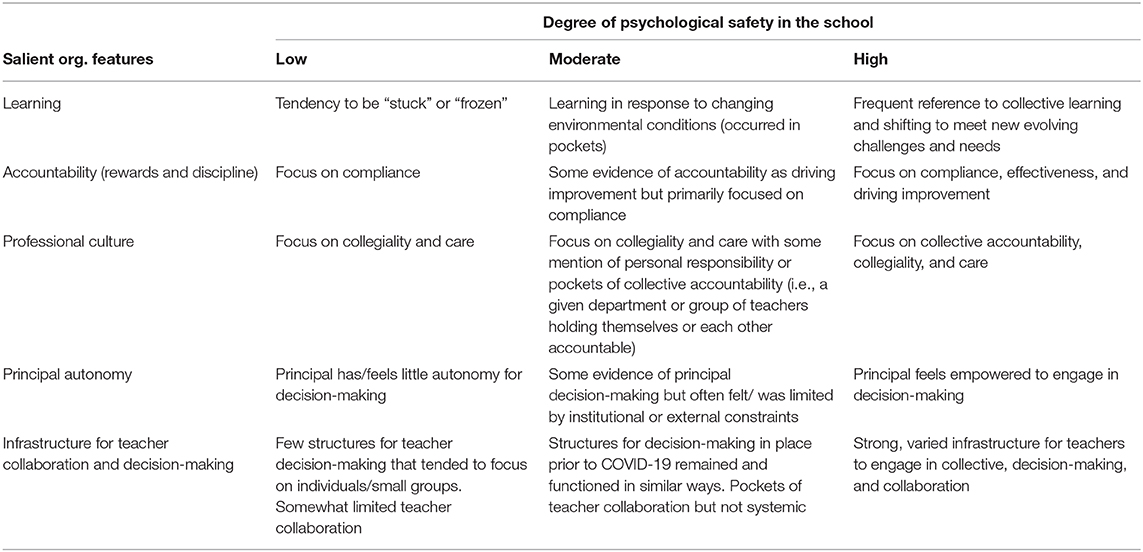

Differences in Organizational Conditions for Psychological Safety

While we identified many nuanced differences in the organizational conditions across the schools. Per the principals' descriptions, five organizational conditions emerged as particularly salient relative to PS. These elements (e.g., learning, accountability system, professional culture, principal autonomy, infrastructure for teacher decision-making and collaboration) and how they manifest in the daily lives of educators in these schools are described in greater detail in Table 3 below.

In the following section, we provide examples of the above salient organizational conditions in the schools we identified as exhibiting low or high levels of psychological safety. We do so as the schools with moderate PS tended to sit between these two poles and we felt this approach was the most useful and efficient means to illustrate our findings.

Organizational Learning

We begin with the end in mind with the observed differences in the desired outcome of PS- organizational learning. As described above, organizations with high levels of PS promote collective learning and change, ultimately leading to improved organizational performance (Edmondson et al., 2001; Morrow et al., 2010). Such growth allows organizations to “unfreeze” (Schein, 2010) when facing a challenge. Given that, due to COVID-19, teachers were forced to engage in at least one dramatically different way (i.e., in-person to remote), we might say all were forced to learn. With that said, after a period of shifting to their new modality, some principals reported that their schools continued to adapt to their changing environments and students' needs and while others shifted their mode of delivery but little else, even when data suggested current efforts were not working as desired.

Low PS Schools: More Frozen Than Fluid

In schools identified as having low PS, principals described teachers having difficulty shifting and/or enhancing their practice to meet students' needs after switching to remote learning. For some teachers, this difficulty was rooted in using technology, and what seemed to be a lack of institutional support to facilitate growth in this area. For example, S71 told of a veteran teacher who got stuck in the transition to Google classroom, and, as a result, was asked to retire rather than return for Fall 2020.

She [the teacher] goes, you know how much I struggled with just uploading documents? And I said, “I do”…again, not about her age, but about her efficacy. To me, it's an efficacy issue and you could be a hundred or you could be 25 and have the same issues of technology. And if it's not in your wheelhouse, this type of instruction and a pandemic is, so not gonna be your cup of tea.

While S7 was clear this teacher's experience was more the exception than the rule, this trend, that groups of teachers in schools identified as having lower levels of PS were unable to adjust their practice to meet the new virtual environment, frequently occurred, and extended from modality to content. UC5, for example, spoke about the variable ways his teachers responded to the need to change how and what they were delivering to students. He recalled how the eighth-grade teachers, now without an end of year exam to attend to, were like, “Now, what the hell do we do because the test got canceled?” As a result, courses were a “boring experience” for students with little innovation or change.

Other principals too talked about how teachers' thinking regarding how to encourage greater participation, engagement and student learning in the remote learning space was often stuck. S17 described her teachers as having difficulty learning how to best connect with students and families in this new landscape. As she explained, when students were struggling in math, teachers had difficulty figuring out how to best address students' needs.

They [math teachers] were struggling and they will usually know the reason why they [students] were not responding… I told the teachers, “You can't just email once and say, okay, this kid is out. You've got to follow through with the calls and you've got to do all that thing.” So, um, that was, that was difficult because high school teachers, a lot of, they're not like elementary teachers, elementary teachers are talking to parents every week. And then, usually, high school teachers call when there's something wrong.

The difficulty teachers exhibited were particularly pronounced with students identified as having disabilities. Principals in schools with lower PS told of how, given the constraints, they largely failed to serve this student population during closure. UE3 said,

What was most interesting though were our families with kids with disabilities because they are used to their kids receiving special education services and speech services. That wasn't necessarily possible for all in the same way as this. That was a gap I couldn't close. We just didn't have a way to do that.

S6 provided a similar response regarding their approach,

We didn't do anything…so unique that we should win an award for. I mean, I, I think it's just being from a leadership perspective, being present, being aware, being accessible…advocating when we could, you know, to central office or, “Hey, what about this? When can we do that?” And so on.

Across these examples, the sense of paralysis in the moment is evident. These leaders were faced with improbable challenges but were unable to incorporate new forms of learning. Rather, they relied on old forms of learning which created difficulty in supporting students and teachers through the change process.

High PS Schools: Adapting Together to Shifting Needs

In high PS schools, principals adjusted quickly to an evolving environment. They restructured educational practice to remote learning environments, while also ensuring teachers were continually adapting their practice to meet students' evolving needs. As UE5 stated, “We were adjusting to the needs of the kids, to the engagement data…and my student support team was more unified in terms of the outreach they did to students via phone and meetings.” Principals too discussed shifting their staffs' expectations to adhere to the changing educational environment. For example, S13 expressed “…we started saying things like, ‘Take your plan, cut it in half, and then cut it in half again, and then you might have something to work with.’ I'm like, ‘You have to remember that you’ve got to meet your kids where they are.” Similarly, UI16 told of how, after settling in to the new platform to deliver instruction, the real work of teacher and student learning began.

We went from kids constantly being in groups and constantly being in partners. You go online and suddenly you're like posting asynchronous tasks, and then… you're having office hours where kids are suddenly individual agents and hating it, right? And it took us a few weeks before we're like, “God, this really feels like soulless in some ways. It feels like kids are so disconnected. Oh yeah. Because they're not working together. Right.” And so… really trying to dig into some structures…right away everyone talks about like Zoom Breakout Rooms and like, yeah, cool. But I think there needs to be a ton more structure in place in the same way we would in the building. ’Cause kids don't just, like, get together and just start collaborating. It takes a lot of work to make that happen. And how is that transferred to the remote world? And so, yeah, I think those are probably some of the key pieces that we've been underlining.

In further contrast to the low PS schools, this focus on meeting students where they were and constantly adjusting instruction in response, also happened in regards to serving special education students. For example, UC6 discussed his school's strategy when it came to their special education students,

We sat with the special education team, we had all 35 of our special ed kids and said, “Here's what they all need. Here's what their schedules are. Let's plug people in where we can…” So that's what we did, we just kind of made sure the kids were covered… “This one has the IEP, this is what it says, Here's what we need, okay, we're going to put a part in that group, you guys are going to work with those three or four groups of people” and then we present the staff so they would know which co-teacher would be in the room with them. And then when they were able to create break out groups, they could have that para or that teacher with a group of kids they really needed to work more closely with, so we just tried to do more common-sense things like that.

Other principals in high PS schools also shared that a priority was centered around providing specific learning services for their special education students. UI9 stated, “The success with the special education students came when teachers would just sit down and have a chat with a student for an hour…” Even though principals recognized this approach was unsustainable over time, they did all they could to temporarily meet the need for teachers to provide individualized learning experiences for their special education students with plans to keep adapting over time as the conditions changed.

Accountability (Rewards and Discipline)

Organizations with high levels of PS provide a compelling vision for change (Schein, 2010) and a rewards and discipline or accountability system clearly articulated and aligned with desired learning outcomes (Knapp and Feldman, 2012). As described earlier, such organizations create conditions that mitigate learning anxiety associated with internal and external pressures (Schein, 1999). Given that, in all of the schools in which we focused our inquiry, there were moratoriums on student testing and, in most, on formal teacher evaluation, this period may have been one in which different and new accountability systems were leveraged to better facilitate learning. And yet, in our analysis, we find that only schools with high PS made such moves while the low PS schools tended to orient themselves toward ensuring teacher compliance rather than adaptability or effectiveness.

Low PS Schools: Compliance and a Lack of Clarity

Unclear accountability standards around student attendance, engagement, and assessment defined the months between March and June for all 15 schools with low levels of PS. For example, school leaders struggled with whether and how to monitor students' presence or absence from online instruction. According to UC5, “attendance and grading was very muddy. Nobody knew, how do I know how to mark a kid present or absent?” Similarly, UE3 said, “If attendance is measured by heads participation, because the position was that teachers connected with kids twice a week. That was kind of how attendance was counted. If that's how it's counted, then we had well over 95%.”

Leaders in these schools also focused primarily on ensuring teachers delivered the right amount and type of instruction rather than whether the instruction was of high quality. Indeed, principals in schools with low PS indicated they were unable, due to state policy or union rules, to engage in classroom observations to see how things were going and/or to hold teachers accountable to enhance their approach. S1 shared, “No, I'm not observing teachers because if they were not observed in person, we were not supposed to observe them.” UI15 too said,

The MOU with [the Union] stated that principals, like all evaluation, everything stopped. We weren't able to push into any teacher's class to observe what they were doing…we couldn't just join a Zoom call… That was a little problematic because I was blind. I couldn't really help on that level.

Other leaders indicated that despite being able to attend teachers' sessions, they felt unwelcome in classrooms and relied on invitations to observe instruction. UC5 described a process of,

redefining, monitoring instruction with them. So, we made a schedule of whatever teachers were teaching live, “Just invite us so we can go in,” but it was almost like, “Please invite me so I can supervise you…” And so, clearly those who didn't want to be supervised, were not eager to send out those invitations.

In some cases, leaders faced with this sort of response simply ceased observing teachers. UE3 said, “I made a conscious decision not to just…pop into classrooms. No, I'm not for that.” S5 said observations “just dropped off. Canceled.”

High PS Schools: Accountability for Compliance, Effectiveness, and Improvement

Principals in high PS schools generally reported receiving clearer messages about what teachers and students should be accountable for and how and these accountability systems promoted adaptability. For example, in discussing the messaging their school received regarding student attendance and performance, UE1 recalled,

In the beginning it was like monitor, monitor, monitor, and then I think when I saw our superintendent she was like “Look, we have to realize that the dynamics are different. So, for some of our kids that can't log on, give them credit for doing the work.”

When a lack of clarity regarding accountability did exist, principals in high PS schools worked to buffer teachers from this uncertainty by creating clear guidelines. Often, these new structures and systems were jointly constructed with teachers and again seemed oriented toward adaptability and grace given current conditions. For example, as UI13 explained,

The first thing that we did once we started remote instruction was to create metrics of student engagement participation. We put everything that could represent student engagement, from checking their email, to being present in a live remote class, to submitting an assignment, counted all of that and figured out what the average number of engagement points were per kid. Then, we were able to see where our student was in terms of overall engagement. So, 100% was average. Plenty of people, they got 400% and some kids who had zero. Then, looking at that vs. number of assignments turned in, we could tell that if a kid was failing a class, was it because they weren't engaging? Or was it because they weren't doing their work? And that was just … It's a simple distinction but it was an important one to know so that we could figure out what kind of intervention we had to offer.

In this case, and with many of the principals in High PS schools, we see the extension of accountability from a means of ensuring compliance to a tool for supporting effective instruction and learning—in this case, to provide targeted interventions to students based on needs. This was true for S16's school as well, where teachers tracked.

whenever a student wasn't engaged…I think we had about 60 kids who were very, very minimally engaged…The rest of them were engaged weekly, if not daily. But still 60 kids is a lot of kids. So, our Dean spent a ton of time reaching out to those kids. We got notified every Friday. Our admin intern…was working on the attendance and then she would call home. If there was no call home, they would potentially do a home visit, knock on the door, try to re-engage the student in the learning.

This theme, that the accountability structure should be responsive to students and teachers changing realities was picked up in other interviews. Principals spoke to the delicate balance of ensuring students were held accountable and that current hardships such as hunger, grief and/or a lack of parental support were acknowledged and attended to. As S8 explained, “we're not gonna hold kids at harm, their grade isn't gonna go from an A to an F because you're [parents] not there to support them.” Similarly, S13 said,

What we've been doing is using our counselors and our paras and our security monitors, so kids who are more at risk or less likely to engage, we don't do attendance. We do engagement, and…if kids aren't engaged, we'll start with a phone call… I'm coaching teachers on the difference between saying, “Hey, you didn't do this assignment. If you don't do it by Friday, you're gonna get a zero,” to, “Hey, I noticed you haven't checked in a week. Is everything okay? Is there anything I can do to help you out? I'm concerned about you and I care about you. Let me know how you're doing and we can talk.”

Additionally, in contrast to the principals in low PS schools, principals in high PS schools, whether required or permissible by the union and/or district, all mentioned attending teachers' virtual sessions in some capacity. As UE5, explained, “Teachers never knew when you were going to pop in. Except they had to accept you once you joined the class. Outside of that, it could be in the middle, it could be toward the end, it could be in the beginning. They knew that we were going to show up.”

Professional Culture

Organizations with high levels of PS are defined by a culture where people feel supported and pushed to engage in the interpersonally “risky behavior” of learning and change, whereas those with lower levels of PS can often be characterized as collegial and/or caring but lacking in terms of a collective push to learn and change.

Low PS Schools: Collegiality and Care

In low PS schools, professional culture included an ethos of collegiality and care where leaders engaged in empathetic behaviors to comfort staff during an intensely challenging period but lacked the additional features of collective accountability and collaboration that would support risk-taking or deep learning. In some instances, the shift to virtual school put the lack of strong professional culture in the spotlight. When asked about how they kept teacher morale up, S6 shared, “Yeah. You know, and I guess in retrospect, we didn't do anything to measure it…I don't have a, a clear baseline…to take a look at some of the things.” In S7's school, teacher trust was low. S7 said, “I would call them, I would check in on them. And I'd say, “What are you doing for you today?” Would you make random phone calls? They'd be like, “Why are you calling?”

In other contexts, leaders referred to holding happy hours or other social events to keep spirits up. S2 said,

We did have like a staff, a couple staff happy hours, where staff would send in like a post that made them laugh out loud. Then I compiled them in a video and it was basically like a blooper reel, we would watch that together.

UE8 too said,

Sometimes I would just do a recorded message to them on Fridays where I just sang the praises of our teachers. I was like, “Guys, I know this is a heavy lift, I see what you're doing, I appreciate what you're doing. I know that like me, you have young children at home and you're balancing this work as well as making sure your students, your children are doing the work that's been assigned to them, and I appreciate you. It's making a difference.”

Beyond these efforts to bolster spirits, however, little changed in these organizations. Little to no evidence of collective accountability with teachers pressing each other to learn in new ways was present.

High PS Schools: Collegiality, Care, and Collective Accountability

In schools with high levels of PS, collective accountability for instruction permeated the professional culture as much as empathy and collegiality. Nearly every principal explained that demonstrating empathy, in the form of listening, was a critical dimension of their leadership. UI14 explained,

As a leader, I feel like I have to stay open-minded, but my own opinions don't matter right now. I have to take myself out of that picture and just hear and allow others to express how they [teachers] feel. I have to put my armor down, I have to really take that armor off and not meet everything confrontational or defensive, even if it is something directly at what I did or how I led. I have to allow those conversations to be had, and I have to be able to be self-reflective on those, because I can only grow from this. And when I grow, I feel my entire staff, my community, my students will have that chance to grow with me.

Some principals developed infrastructures to individually check-in with staff throughout the week. UE1 explained, “I created telecaptains. We had six leaders in the building. So each telecaptain was only responsible for nine people, so they had to have check points with those nine people…every day.” This principal too recognized that checking in went beyond strictly professional issues,

People are worried, people don't know about their job security, it's a lot. So, for me, I really want to make sure that the people in our building are okay, how are they feeling? I've had some teachers sit and just really stress about what they're going through, their spouses have lost jobs, they've had layoffs.

Equally prevalent in empathetic leadership behaviors was the principal's commitment to asking the staff, often individually, what they needed. UC2 explained that an important leadership aspect during school closures was “supporting the teachers, putting them at ease, and… and constantly saying, ‘What do you need, how can we support? We actually met with coaches and the teachers one on one. The biggest thing for me was to support the teachers.”

Beyond collegiality and empathy, most principals in schools with high levels of PS also highlighted how their staff pushed one another to work hard and press for change (i.e., they exhibited collective accountability). For example, UI13 asserted,

We have a very dedicated group of teachers and support staff. People know what they're doing. They have a lot of autonomy… there's a lot of shared decision-making and flat hierarchy and things are managed through teacher teams… They take things very seriously. People are proud of their work. There's a lot of staff cohesion.

Principals also recalled the ways teachers' collaboration toward enhancing practice intensified during the pandemic, especially as they witnessed teachers familiar with technology support less experienced colleagues. S3 explained, “My staff is absolutely incredible. In times of crisis, like creative things happen. Teachers were collaborating, they're working together ’cause in every grade level team, you have the super techie people and then you have the more traditional people. So they were really working together, sharing resources.”

Principal Autonomy

PS is fostered when employees, and, in this study, principals, have the authority and autonomy to make important decisions and are clear about what is and is not their job (Frazier et al., 2017).

Low PS Schools: Hands Tied

In schools with low levels of PS, principals felt their autonomy over curriculum, scheduling, and technology distribution, among other things, was highly constricted and often by their district and/or union. For example, in the low PS schools, leaders indicated they had little to no discretion over the parameters of teachers' instruction. UI15 and UI2, both in the same strongly unionized state, described the union's role in defining teachers' work. UI2 said,

Teachers were required to have at least one hour of office hours, where they will communicate or be available for parents or students to answer any questions. Around at least an hour a day…as principals, we were given the liberty of having one staff meeting per week and one department meeting per week as well. With established expectations of sending the agenda, I think 24 hours before, and ensuring that we were working on the goals for the school and as a district.

Here it is worth mentioning, there were other principals in the same state and in other states with equally strong unions who felt far less constricted. As such, it would send the wrong message to suggest that the union or, as we discuss next, the district, was the sole cause for these principals' limited autonomy.

Indeed, some principals felt their district dictated what teachers did during the day. As S2 shared,

A lot of the decision making came from the district office…we had daily elementary admin meetings every single morning. The assistant superintendent and the elementary curriculum coordinator attended those meetings. I would say those were not necessarily decision-making meetings. They were more, “Here's the decision that we've made and we're telling you what it is.” I feel like some of the autonomy I was used to having in my job went away when this happened.

Likewise, S6 described “central office, especially the curriculum office had…to take charge of the whole instructional program because at the elementary level, our elementary teachers were not that well-versed in using the online platform.” In all instances, leaders in schools with low PS described feeling they were not empowered to make important decisions during this time.

High PS Schools: Principal Autonomy in Action

Principal autonomy over various elements of school practice was a dominating feature in schools with high degrees of PS. In some cases, principals described how they embraced decision-making once district or state leaders set a general framework for school operations. For instance, as districts communicated to principals that schools would now deliver instruction remotely, district leaders provided frameworks for principals to make decisions about the intricacies of those plans. UC2 recalled that in the days leading up to the school closures, district leaders communicated, “Your job is to make sure that, um, teachers work together. However, you guys want to do it, it's left up to the principals.” Similarly, UC3 recalled decision-making goals made with other principals in the region,

The way we did it was, and sort of aligning with the directors from the state, we created these basically virtual learning plans, and it's basically acknowledging, we can't service your child the same way we would do before, so we're gonna develop plans for each child to help them to access… the virtual learning.

In these cases, principals in high PS schools took action on internal practices in a climate where the district seemed to encourage either independent or collaborative decision-making.

In other cases, several principals in schools with high PS remarked they took control over decision-making when district authorities were slow to enact policies or when district decisions were insufficient in meeting their school's needs. These examples often emerged at the start of the school closures when schools and districts faced the most uncertainty about how to proceed. In one stark example, UI9 decided to, without district permission, distribute devices to students the week before schools closed.

We just started getting a system to give out all of our computers, our laptops. … That felt a little weird ’cause we were like, “We aren't gonna see these laptops again,” but we were kinda like…“doesn't matter.” We know the kids aren't gonna be coming back. Without the laptops, they're not gonna be able to function at all, so we started just passing out the laptops to kids that needed them and recording who took them. … then the [district] was like, “Here's the official permission slip” for when we give out tech, and I was just like… “we're not gonna start doing this permission slip.”

In some cases, principals confronted their district leaders about decisions they made that departed from area-wide expectations. For example, S3 explained,

I did go rogue a few times, of, like, we're not going to be rule followers right now, and we're gonna do our own things. So, you know, I did come clean with my superintendent who was like, “You can't do that.” I'm like, “Yeah, I just did. And that's why it's working.” The whole county shut down for two days for distance learning and we had no gaps at my school.

These examples reflect almost gut decisions that principals believed were best suited to support students' learning and well-being.

Infrastructure for Teacher Collaboration and Decision-Making

Leaders can facilitate organizational learning through building professional learning communities (Bowen et al., 2007; Weiner, 2014; Meyers and Hambrick Hitt, 2017) and conveying and communicating a clear compelling vision and theory of action, especially in times of uncertainty such as during the COVID-19 pandemic (Dimmock, 2012; Thompson, 2017; Harris and Jones, 2018; Paraschiva et al., 2019).

Low PS Schools: Limited Decision-Making

In low PS schools, there were few structures for teacher decision-making, a focus on individuals, and limited collaboration. In most instances, leaders either had no forms of professional learning communities or structures that brought only some teachers together (e.g., department, grade-level and/or faculty meetings), and simply shifted these meetings to become virtual without other modifications to support greater flexibility or teacher empowerment. As S6 explained, “We use basically the same structures that we've always had…they were just virtual.”

In other instances, pockets of more substantial collaboration and professional engagement emerged but were limited. For example, UC5 described how in their school,

In social studies, for the most part, it was, unfortunately, “go on Google Classroom, complete the equivalent of a digital worksheet, look these answers up in the textbook, fill it out, submit it.' My civics team did a little better job of mixing in videos and other stuff like that. But that's very much what it was. Science took a team approach. So a student would, on any given day could login and get live help from a teacher. Not necessarily their teacher, but like one of the science teachers on their grade.

In nearly every instance, leaders in schools with low PS described a proliferation of meetings (often weekly) rather than genuine collaboration or shared decision-making. Interestingly, two leaders described embracing an even more autocratic approach, entirely limiting teacher decision making, albeit in the name of shifting burdens away from teachers. UC1 said, “And so I will, I guess, you know, looking back at it, it's probably more, um, I wanna say autocratic, but I was more, I was more saying to them, here's what I want to have happen and how you make it happen is fine.” Similarly, S7 said,

I'm not an autocratic leader by any stretch of the imagination. In times of crisis and particularly crisis management I think that, um, sometimes having a vision and a directive, and I always think it's important that I think is especially important during this kind of, um, well, it's just so bizarre. Everything that's happened just during this time we needed to do that.

Across the schools with low PS, teacher decision-making and collaboration were limited and often pro forma.

High PS Schools: Infrastructures for Teacher Collective Decision-Making

Strong systems for teachers to engage in collective decision-making and collaboration was a prevalent feature of schools that exhibited high levels of PS. Several leaders relied on pre-existing routines such as academic department teams, professional learning communities, and grade-level teams but did so in ways that supported modifications to meet the staff's shifting circumstances. UI13 explained,

I think more than anything, the thing that's gotten us through is the fact that teacher teams are autonomous, that they have agency, that people are willing to be creative and go along with the shared decisions of the group even when they're a little outside the box.

Drawing upon pre-existing infrastructures built for flexibility and change meant school leaders could support staff members with a range of needs. UI14 explained that decision-making for remote instruction resided in academic department meetings and were for,

teacher leaders and school leaders to share best practices, technology, to talk about what was working. A lot of it was sharing best practice. Coming up with common schedules that worked for kids, communicating about kids' needs, doing some online visitation of classes. Sharing data and… the stories behind the data as far as attendance and engagement. We trusted the systems we had already around curriculum and student support.

Other principals discussed how they also devised new routines to support teaching and school policies. While most of the existing routines at UE7's school supported staff during school closure, a new Remote Learning Leadership Team of school leaders and a teacher with expertise in virtual learning,

drove the final decisions and planning. We used a collaborative approach where we would draft, then we'd have listening sessions with the stakeholder groups, and then we come back and refine the draft and then present the conclusion. So, the remote learning leadership team was a really important move that we made.

The process that UE7 describes of developing structures to receive feedback from staff on instruction and policies before making final decisions was a salient feature of schools with high PS. For example, S8 recalled that weekly staff meetings enabled meaningful decision-making. “We really felt like we needed to create a system and structure in order to have very cognizant check-ins with our staff… And each of our six leaders had like 12 staff members to individually check in with each week.” These routines, coupled with a weekly survey, enabled the leadership team to design meaningful professional development sessions responsive to staff needs.

Discussion and Implications

In this study we sought to understand how, during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, principals created, or failed to create, psychological safety in their schools and how these efforts and their outcomes may have varied across contexts. We find, as indicated in other research focused on teachers' working conditions (Johnson et al., 2012; Simon and Johnson, 2015), organizational features appeared to trump environmental ones, in terms of promoting PS and learning. These organizational conditions—including the nature of accountability, the degree of principal autonomy, the professional culture, and teacher decision-making infrastructure–were particularly important in facilitating teachers' ability to innovate, make mistakes and learn (i.e., engage in PS).

Before discussing these findings and some of their implications, another contribution of this work is its use of PS as a guiding framework. Still underutilized in the field of education, PS provides opportunities, as Higgins et al. (2012) and Wanless (2016) call for, to increase our focus on adult learning within schools and consider the conditions that might serve to hinder or promote such learning, particularly in times of crisis when such learning is essential (Wooten and James, 2008; Smith and Riley, 2012). Moreover, by situating PS as a key element of schools' professional culture and the need for leaders to regularly attend to it, such work can foster new conceptualizations of school leaders, not just as facilitators of student learning, but as facilitators of adult learning and development as well. We hope our study and these possibilities will inspire others to use PS in their research and particularly when looking to better understand school improvement and positive change in times of calm or crisis.

Shifting to the findings, first, there was a good deal of heterogeneity in the PS and learning that occurred across our participants' schools. This may be somewhat surprising given that all schools simultaneously faced the same crisis (albeit with different levels of severity) and that COVID-19 required all educators to shift the delivery system of schooling (e.g., in person to remote). Moreover, as we considered whether environmental factors, and specifically, urbanicity and the needs of students served, as determinants of schools' degree of PS, we found a lack of strong evidence of these factors' impact. If anything, schools traditionally deemed to have less environmental uncertainty (i.e., suburban, well-resourced, predominately white) were more likely to be rated as having low PS. Beyond reinforcing Authors' (2013) findings that PS tended to vary across schools in a singular district, this inquiry may also indicate a potential lack of adaptability of better-resourced schools in responding to adversity and/or an overdependence on the students rather than teachers to produce effective outcomes (Sandy and Duncan, 2010). Clearly, more research is needed to understand these outcomes, including studies that provide opportunities for more sophisticated statistical analyses to examine these phenomena.

Second, high and low PS schools responded differently to states' decision to suspend external accountability measures in the spring. In low PS schools, instruction seemed to reflect a more compliance orientation at best, and an absence of teacher feedback at worst. Yet in high PS schools, leaders seemed to embrace the absence of external accountability measures by joining with staff to develop new guidelines for teaching students in a virtual climate focused on providing their learners with meaningful experiences and seeing teachers in practice. As research shows the limited success external accountability measures have in promoting deep learning among adults and students before the pandemic (e.g., Dee and Keys, 2004; Podgursky and Springer, 2007), and because our analysis reveals that schools with high PS continued to facilitate learning without them, this study provides further evidence a new path forward regarding accountability in schools is needed.

Third, in terms of professional culture, we found that while principals across our sample described their school's culture as caring and collegial and acted in ways that promoted these norms, a practice aligned with effective leadership in crisis (Smith and Riley, 2012), what distinguished high and low PS schools' professional culture was the presence of collective accountability and collaboration. In high PS schools, staff members were said to expect more from their colleagues. Through infrastructures designed for collaboration, teachers supported each other to improve their remote instructional practices. Our findings align with research emphasizing the import of collective accountability for professional learning (Elmore, 2007; Sahlberg, 2010) and alongside PS specifically (Schein, 1999; Higgins et al., 2012, in press). Such findings, and aligned with the need for more anti-racist efforts in schools (Swanson and Welton, 2019), again promote the need for schools to move away from a culture of “nice” in favor of rigorous but supportive conversations that press for change.

Fourth, in high PS schools, several principals–almost reflexively–took action to support students' well- being and learning, even when new district policy countered their choices. In the schools with low PS, principals repeatedly discussed feeling disempowered in the presence of district or union leaders' decisions that dictated various elements of school practice. These differences in how principal autonomy was constructed and utilized is shown to have important implications for principals' feelings of efficacy as well as their ability to facilitate the learning and growth of their teachers (Weiner and Woulfin, 2017; Weiner, 2020). However, autonomy must be coupled with both district-level infrastructure and professional support to ensure greater effectiveness for principals as they grapple how best to take action (Tulowitzki, 2013; Weiner and Woulfin, 2017).

Finally, our findings reinforce research that leaders can cultivate learning through organizational routines such as professional learning communities (Bowen et al., 2007; Weiner, 2014; Meyers and Hambrick Hitt, 2017) and communities of practice (Wenger, 1998). Infrastructure designed to gather staff input on key school decisions or to facilitate collaboration on instruction impacted the degree to which schools possessed PS. In high PS schools, principals either adapted existing infrastructure to capture teacher input or devised new systems to ensure staff's voices were included in school policies and practices. In schools with low PS, principals recounted inconsistent approaches to sharing best practices and adapting to the virtual learning environment, largely due to the lack of infrastructures that would regularly support shared opportunities to deepen teacher learning. Such findings show once again that although organizational routines are needed to facilitate learning, they are not sufficient for this to occur. Collectively, these findings reveal the critical role principals and organizational conditions play in promoting psychological safety and learning, two vital aspects of ensuring adult learning during turbulent and hopefully, calmer times ahead.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this article are not readily available because the IRB does not allow those outside the study to access the raw data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Jennie Weiner, amVubmllLndlaW5lckB1Y29ubi5lZHU=.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Pennsylvania IRB. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in all aspects of the research and writing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the principals who shared their experiences as part of the Leading in Crisis study. The study was a collaborative data collection effort organized by Jonathan Supovitz of the Consortium for Policy Research in Education at the University of Pennsylvania. The research team included: Erin Anderson (University of Denver), Bodunrin Banwo (University of Minnesota), Bradley Carpenter (Baylor University), Joshua Childs (University of Texas, Austin), Chantal Francois (Towson University), Sonya Hayes, (University of Tennessee, Knoxville), Lea Hubbard (University of San Diego), Maya Kaul (University of Pennsylvania), Julianna Kershen (University of Oklahoma), Hollie Mackey (University of North Dakota), Gopal Midha (University of Virginia), Daniel Reyes-Guerra (Florida Atlantic University), Nicole Simon (City University of New York), Corrie Stone-Johnson (University at Buffalo), Bryan A. VanGronigen (University of Delaware), Jennie Weiner (University of Connecticut), and Sheneka Williams, (Michigan State University). More about the study can be found at: https://www.cpre.org/leading-crisis.

Footnotes

1. ^The naming convention is the geographic location of the principal's school (S, suburban; UI, urban intensive, etc.) and the number associated with their information in Table 1.

References

Argyris, C. (1982). Reasoning, Learning, and Action: Individual and Organizational. San Franscisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bowen, G. L., Ware, W. B., Rose, R. A., and Powers, J. D. (2007), Assessing the functioning of schools as learning organizations. Child. Sch. 29, 199–208. doi: 10.1093/cs/29.4.199

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Bryk, A. S., and Schneider, B. (2003). Trust in schools: a core resource for school reform. Educ. Leadersh. 60, 40–45.

Bunderson, J. S., and Boumgarden, P. (2009). Structure and learning in self-managed teams: Why “bureaucratic” teams can be better learners. Organ. Sci. 21, 609–624. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1090.0483

Cohen, W. M., and Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 35, 128–152. doi: 10.2307/2393553

Cosner, S., and Jones, M. F. (2016). Leading school-wide improvement in low-performing schools facing conditions of accountability: key actions and considerations. J. Educ. Admin. 54, 41–57. doi: 10.1108/JEA-08-2014-0098

Creswell, J., and Poth, C. (2018). Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Dee, T. S., and Keys, B. J. (2004). Does merit pay reward good teachers? evidence from a randomized experiment. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 23, 471–488. doi: 10.1002/pam.20022

Detert, J. R., and Edmondson, A. C. (2005). “No exit, no voice: the bind of risky voice opportunities in organizations.,” Harvard Business School Working Paper (Cambridge, MA). 05–049. doi: 10.5465/ambpp.2005.18780787

Dimmock, C. (2012). School-based Management and School Effectiveness. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315824727

Dodgson, M. (1993). Organizational learning: a review of some literatures. Organ. Stud. 14, 375–394. doi: 10.1177/017084069301400303

Donaldson, M. L., Johnson, S. M., Kirkpatrick, C. L., Marinell, W. H., Steele, J. L., and Szczesiul, S. A. (2008). Angling for access, bartering for change: how second-stage teachers experience differentiated roles in schools. Teach. Coll. Rec. 110, 1088–1114.

Drago-Severson, E., and Blum-DeStefano, J. (2014). Leadership for transformational learning: a developmental approach to supporting leaders' thinking and practice. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 9, 113–141. doi: 10.1177/1942775114527082

Dworkin, A. G., and Tobe, P. F. (2014). “The effects of standards based school accountability on teacher burnout and trust relationships: a longitudinal analysis,” in Trust and School Life: The Role of Trust for Learning, Teaching, Leading, and Bridging, eds D. van Maele, P. B. Forsyth, and M. van Houtte (Heidelberg: Springer), 121–143.