- 1Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, United States

- 2Educational Administration and Policy, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, United States

- 3Educational Administration, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

Rural school leaders are met with serious challenges and opportunities to lead rural schools in times of normalcy, but these challenges are amplified during a crisis. Rural school principals in the United States faced an unprecedented crisis when school buildings closed in spring 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The measure of rural school principals and their response to this crisis is exemplified through their leadership practices. Through qualitative methods, we examined the leadership practices of rural principals through the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic and quarantine, and we found that rural principals exhibit the practices of caretaker leadership. From the findings, we used a meta-leadership frame to discuss the caretaker leadership practices of rural school principals.

Introduction

Rural school leaders are met with serious challenges and opportunities to lead rural schools. Rural school leaders face challenges that include being professionally and geographically isolated (Ashton and Duncan, 2012; Versland, 2013; Casto, 2016; Parson et al., 2016; Hansen, 2018); recruiting and retaining quality school teachers (Du Plessis, 2014; Ulferts, 2016; Hohner and Riveros, 2017; Hansen, 2018; Hildreth et al., 2018); deepening and persistent poverty among students and their families (Schaefer et al., 2016; Farrigan, 2017; Showalter et al., 2017); and facing a lack of resources (Forner et al., 2012; Barrett et al., 2015; Ramon et al., 2019). The opportunities they face include leading smaller schools in more cohesive communities with less crime (Southworth, 2004). The cohesive community structure lends to a school-community environment in which family engagement is relatively high (Semke and Sheridan, 2012) and principals are viewed as leaders and pillars of the community (Preston and Barnes, 2017). While there are challenges in rural school leadership, Surface and Theobald (2014) argued that rural schools could be ideal places to create conducive learning environments for students. The rationale behind their argument is most rural schools have a small population as well as a more personal accountability approach (Surface and Theobald, 2014), which allow students and adults to be more familiar with each other as well as create spaces for interactions. This opportunity distinguishes rural school settings from urban and suburban school settings, which tend to have a larger student population that limit adult/student relationships. With this said, frequent interaction and communication among students, teachers, community members, and administration continues to rank in the top 3% of lists for characteristics of effective principals (Surface and Theobald, 2014).

As the COVID-19 virus swept through the U.S., and schools across the country began closing their buildings, rural school leaders faced even further challenges in supporting their students. Such support was stifled by students' limited access to technology, lack of reliable internet access, transportation shortages, and inconsistent access to food (Hamilton et al., 2020). The purpose of this study is to examine the leadership experiences of rural school principals across the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic and quarantine. More specifically, our study seeks to answer the following research question:

How did the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting quarantine shape rural principals' leadership practices?

Although ~20% of America's school-aged children are educated in rural schools, less is known about the educational environment of rural schools (Lavalley, 2018). Moreover, very little is known about the conditions in which rural school leaders do their work. This study is relevant because unlike urban and suburban schools, “little is understood about rural schools and the unique challenges they face outside of the communities in which they operate” (Lavalley, 2018, p. 1). Additionally, the leadership experiences, barriers, and administrative opportunities of rural school principals have been overlooked as compared to their urban and suburban counterparts (Parson et al., 2016). Through qualitative interview data, we highlight rural school principals, the persistent challenges they faced due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and their response to such challenges.

Relevant Literature

In an effort to better understand how rural school leaders made decisions during the onset of COVID-19, we examine three broad domains: (a) rural, rural context, and rural education; (b) rural school leadership; and (c) Meta-Leadership and Situational Leadership frameworks. The first stream of research combines literature on the definitions and characteristics of rural, rural context, and rural education. First, to gain a complete understanding of the purpose of this paper and its relevant literature, it is important to understand what is meant by rural and the characteristics of its context. The second stream of research describes rural school leadership by examining characteristics, such as common challenges among rural school principals, that seemingly are expected of individuals who lead in a rural academic K-12 setting. The third and final stream of research briefly defines both meta-leadership and situational leadership frameworks.

Rural, Rural Context, and Rural Education

While there are multiple definitions of rural, this research project employs the definition according to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (2016), which defines rural less on population size and county boundaries than on the proximity of an address to an urbanized area. NCES defines rural into three territories:

• Fringe: territory that is less than or equal to 5 miles from an urbanized area;

• Distant: territory that is greater than 5 miles but less than 25 miles from an urbanized area; and

• Remote: territory that is more than 25 miles (p. 2).

The rural context refers to the circumstances in which rural schools exist. Compared to their urban and suburban counterparts, the history, economic and political trends, geographic barriers, inequities, and demographics highlight many of their differences. Some of these differences, which impact academics and academic settings, include higher rates of unemployment, underemployment, and poverty (Curtin and Cohn, 2015). According to Lavalley (2018), “more children in rural communities come from conditions of poverty than in the past,” and the population of rural America has historically been, and largely remains, overwhelmingly White (pp. 4–5). Just over one in four rural students is non-White, though this portion varies significantly by region and by state (Showalter et al., 2017).

Approximately 64% of rural counties have high rates of child poverty, as compared to 47% of urban counties (Schaefer et al., 2016). These distinctions, as well as others, reflect the schools within rural communities. There are profound academic hurdles that rural communities and rural students must overcome. Although lower literacy rates and limited access to advanced coursework and technologies plague rural contexts, rural students are earning “high school diplomas at a higher rate compared to their urban counterparts, but rural high school graduates are not attaining postsecondary degrees at the same rate as urban high school graduates” (as cited in Lavalley, 2018, p. 12).

Rural communities and schools are unique contexts that are characterized by a strong sense of place (Bauch, 2001; Schafft and Jackson, 2010; Brown and Schafft, 2011). Bushnell (1999) defines a sense of place within rural settings as “the central cohesion points of a life interconnected with other beings” (p. 81). In the past, rural communities have been mischaracterized as a “problem to overcome” and not “a setting to understand” (Burton, 2013, p. 8). However, students in rural schools tend to perform as well or outperform their suburban and urban school peers on various NAEP tests (Showalter et al., 2017). It is important to acknowledge that all these components help shape the culture of a rural community and is critical to understanding rural educational leadership.

Unique Characteristics and Issues Related to Rural School Leadership

How school leaders, specifically principals, successfully lead schools in unique geographical contexts—namely, in rural schools—continues to be understudied (Preston and Barnes, 2017). This attention to rural school leadership is significant as school leadership is informed by the particulars of the school community and its geographical setting; yet, scholarship about successful school leadership is often unrelated to situational realities and geography (Starr and White, 2008; Clarke and Stevens, 2009).

Although there is a paucity of research concerning rural education, a few studies have been conducted to address common leadership practices among rural school leaders. Among these studies, two themes emerged: rural principals lead with a people-centered focus and rural principals are change agents.

Being people-centered includes creating and maintaining healthy relationships with faculty, staff, students, and community members. Such relationships are created and sustained in a variety of ways that include, but are not limited to (a) promoting staff collaboration and capacity building (Pashiardis et al., 2011; Klar and Brewer, 2014); (b) being more accessible, as compared to urban principals, (Preston, 2012); (c) fluid communication with parents (Latham et al., 2014); and (d) nurturing positive school-community relationships (Ashton and Duncan, 2012). A change agent is an individual who supports educational, social, cultural, and behavior change in an organization. According to Preston and Barnes (2017), rural principals are in an “ideal position to lead” (p. 10). One way a rural principal exhibits tenets of a change agent is by balancing local and district needs. However, to achieve this task, rural principals must possess a deep understanding of the community's value systems, and they must be visible, accessible, and approachable.

Barley and Beesley (2007) assert that the primary role of a rural school is to serve the community. The most prominent way it serves the community is often being the major employer in the community. The school leader in a rural community is considered “public property” and on “call to the community 24 hours a day” (Lock et al., 2012, p. 70). Unfortunately, high turnover rates among rural school leadership plague rural communities for various reasons, such as isolation, budgets, salary, and community challenges. These high turnover rates impact the school community and lead to a lack of continuity in school planning and the ability to lead effectively (Arnold et al., 2005; Browne-Ferrigno and Maynard, 2005; Fusarelli and Militello, 2012; Lock et al., 2012). With these emotionally and physically challenging factors, rural school leaders are still expected to meet the daily needs of students (Southworth, 2004; Barley and Beesley, 2007; Starr and White, 2008).

Theoretical Framing

We used the tenets of a meta-leadership framework (Marcus et al., 2019) to anchor our investigation of how the COVID-19 pandemic and quarantine informed the leadership practices of rural principals. The meta-leadership framework is a useful approach to examine the leadership experiences among rural principals during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic and their response to the quarantine and school building closures. This framework recognizes the unique situation such as leading and responding during a crisis (e.g., pandemic); the impact of self-awareness and self-regulation in order to lead themselves and others to stability; and the complexities of influencing multiple stakeholders (e.g., teachers and parents), including those who are outside of their authority, such as politicians and community members (Marcus, 2006).

Relatively new to the leadership theory family, the meta-leadership framework is becoming more widely recognized and adopted, particularly for leading in emergency preparedness and response (Marcus, 2006), such as the COVID-19 pandemic and quarantine. Meta-leadership is defined by Marcus et al. (2019) through three dimensions:

1) the person or personal characteristics of principals who exhibit emotional intelligence, and who develop credibility, trusting relationships,

2) the situation and a principal's grasp of the complex problem and actions taken through communication and decision-making,

3) the connectivity and how principals build networks through partnerships, collaboration, and work with stakeholders.

More specifically, meta-leadership closely examines a leaders' self-awareness, self-regulation, and ability to make sound decisions and create a sense of safety during a time of uncertainty while discerning both the situation and what must be done in the short-term and long-term. Additionally, meta-leadership closely examines how the leader responds to a situation and how he/she connects people and organizations to create unity of effort to solve the issue (Marcus, 2006). While this leadership approach has been utilized after large and complex disasters such as the Boston Marathon bombings and the H1N1 outbreaks' responses, it is appropriate in the context of rural school leadership during the onset of COVID-19.

Within the meta-leadership framework, a leader must assess a crisis situation and respond appropriately. In essence the meta-leadership framework incorporates a more recognized leadership approach, situational leadership, to provide an avenue for leaders to offer instruction, directives, and support based upon the needs of the followers and organization (Hersey and Blanchard, 1977). A key to situational leadership is the leader's ability to adapt his/her style to meet the needs of stakeholders. Leaders face various situations every day, and they must assess and understand the situation, predict how it will unfold, make a decision, and take action (Marcus et al., 2019). In times of crises, timing is critical, and the leader must assess the situation quickly and take appropriate action. Situational leadership has been studied or applied in multiple contexts, including public school institutions (Ali, 2017) and is a vital component of meta-leadership (Marcus, 2006). Meta-leadership provides a lens through which to view rural school leaders' practices as the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting quarantine loomed large over their schools, thereby altering their day-to-day leadership practices.

Methods

In Spring 2020, the Director for the Consortium for Policy Research in Education (CPRE) at the University of Pennsylvania assembled a team of educational leadership researchers from across the U.S. to interview school principals in varying contexts about their leadership experiences during the initial months of schools closing due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The research team, comprised of 20 faculty members in different institutions of higher education conducted 120 qualitative interviews with principals in 19 different states and 100 districts between mid-April and early August 2020. Two of the authors of this study (authors one and three) were members of the research team. The interview protocol was collectively created by the team of researchers and organized to examine the issues facing school principals as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and quarantine. Interview questions focused on the following: (a) instructional responses; (b) challenges for students, families, and teachers; (c) district guidance; (e) crisis management; (f) inequities exposed by the pandemic; and (g) strategies for self-care and well-being. Moreover, the questions were designed to ask principals about their leadership experiences before the crisis and explored how their leadership decisions changed during the pandemic and quarantine. All interviews were recorded, transcribed, and shared among members of the research team. Additionally, a comprehensive list of participants was created to identify the following: (a) grade level—elementary, middle, or high school); (b) school context—urban, suburban, or rural, and (c) school location by state.

Sample

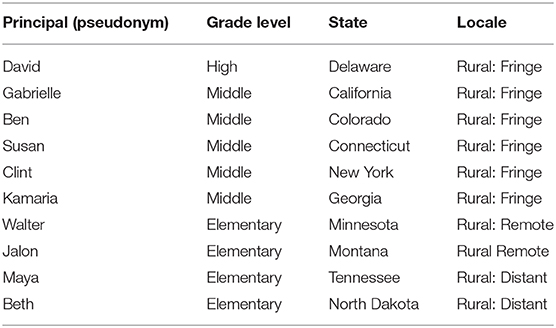

This study draws from a subset of structured interviews from the larger set of 120 interviews. We purposefully sampled principals in rural contexts for this study. Approximately 15 rural principals were interviewed in the larger study; however, only 10 of those interviews were transcribed at the time of our writing. Our sample of participants lead schools in a variety of rural contexts—rural fringe, rural distant, and rural remote. Two authors of the paper interviewed principals for the study, but those principals worked in either urban or rural contexts. Thus, the authors had no prior relationship with the participants in this rural subset of data.

Data Collection

Interviews were conducted via telephone or Zoom, and each interview lasted between 60 and 90 min. We acknowledge that conducting interviews via telephone or Zoom limits the researchers' ability to observe the context in which the leaders work and engage; however, we acknowledge that time constraints and the COVID-19 pandemic itself played a major role in how we were able to collect data. In an effort to conduct a quality interview, we followed Kvale (1996) and Roulston (2010) and conducted interviews looking for the following: (a) seek spontaneous, rich, specific, and relevant answers from the interviewee; (b) ask shorter questions and expect longer answers; (c) follow-up with interviewee and clarify meanings of answers; (d) interpret meaning throughout the interview; (e) verify interpretations of the subjects' answers in the course of the interview; and (f) ensure that the interview “self-communicates'—it is a story contained in itself that hardly requires much extra descriptions and explanations (Kvale, 1996, p. 145). Attending to the aforementioned tenets of qualitative interviewing helped us to gain confidence in the quality of the data collected from study participants.

Data Analysis

Data used in the analysis of this study were obtained from the larger U.S. dataset of qualitative interviews conducted through the CPRE. Authors sorted the data to identify principals from rural schools. From the larger dataset, we selected 10 transcripts from rural school principals across the U.S. The participants are delineated in Table 1. To ensure anonymity, a pseudonym is used for principal's name, grade level of school, and corresponding state.

After identifying the transcripts for the present study, we applied conventional content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005) to immerse ourselves in the data to obtain a sense of the leadership experiences of rural school principals during the initial months of the COVID-19 crisis. We read through the data to identify codes by highlighting common words used by the participants and then categorized the codes into clusters to identify patterns. We paid specific attention to how the COVID-19 pandemic informed the leadership practices of rural school principals. Recurrent codes included care, empathy, resiliency, connectedness, advocacy, stewardship, and ardor. We then reviewed the coded data several times to identify an overarching caretaker leadership theme and inter-related sub-themes.

We achieved credibility and trustworthiness through triangulation and dual-analyses of the data. First, we achieved data triangulation by using the same interview protocol with all participants and by collecting data from different principals in various states and in various school levels (Yin, 2018). Second, two of the authors analyzed and coded the transcripts individually. By having two different researchers code the data separately, write a separate description of the findings, and compare the analyses, we were able to identify gaps or disparities in our analysis and make corrections.

Limitations

The research process for this study has several limitations. First, the participants in the study all serve rural public schools in different states within the U.S., and principals who serve in charter schools, independent schools, and private schools within rural communities are not included. Additionally, only one rural school principal from 10 different states was included in the study; consequently, the findings cannot be generalized to all rural school principals. However, the data generated might be transferable to other rural contexts. Second, the data collected were from virtual one-on-one interviews, and the principals in the study self-reported on their own experiences and feelings during the initial months of the COVID pandemic and quarantine. We recognize that these findings may be indicative of aspirational leadership (i.e., what principals hoped to do), and many principals across the U.S. are still struggling with COVID-related problems and school issues. We also realize that including other stakeholders (e.g., teachers, parents, and students) could possibly give deeper insight into the principals' actions and responses in the Spring months, but for the purposes of this study, we did not interview these stakeholders. Finally, the meta-leader and situational leadership frameworks are limited in that the meta-leader framework is purposefully designed for crisis leadership and situational leadership is limited to the dichotomy of people and tasks. Since the focus of the study is on rural principals' responses in a time of crisis and how they analyzed the situation and responded, we feel the meta-leadership frame is appropriate for this context; however, the findings cannot be generalized to the leadership styles of rural principals in a non-crisis.

Findings

The purpose of this study was to explore how the COVID-19 pandemic informed the leadership practices of rural school principals across the U.S. Through qualitative analysis, we identified an overarching theme: rural school principals exhibit the practices of caretaker leadership. Within this larger theme, we identified sub-themes to describe the leadership practices of rural school principals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Herein, we discuss the caretaker leadership and sub-themes for this leadership practice.

Principals as Caretakers

The primary theme that emerged in the findings was caretaker leadership. Rural school principals in the COVID-19 study established themselves as caretakers of their school communities by (a) focusing on the social-emotional well-being of teachers; (b) providing social emotional support for students and families; (c) remaining a constant and calming presence within the community; (d) and showing remarkable self-reliance and resiliency. As caretakers of their schools, principals responded to the COVID-19 pandemic by assessing the situation and the needs of stakeholders and serving as advocates to meet those needs.

Social-Emotional Support for Teachers

During the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent school building closures, principals in rural communities were concerned with the socio-emotional well-being of their faculty. Gabrielle explained, “I've been working a lot with my staff–ensuring their mental health and social-emotional well-being…that's top priority.” Clint spoke of the “many layers of mental health” that needed to be addressed, and how as a caretaker, “It is my job to find support for my teachers.” Ben explained that most of his “staff members are young people and live alone—they miss their friends and their family—it's been the biggest struggle—how to navigate the isolation.” In contrast, David discussed his teachers who had small children at home and their added stress of trying to teach and take care of their kids. He commented,

So a lot of them have their own children at home, ranging in age from an infant up, and daycares closed, so I think their challenge is trying to balance their family life and trying to help their own kids with school. It was hard for them to navigate taking care of their students online and their children at home. What takes precedence—being a parent or being a teacher?

Other principals spoke of the stress that teachers experienced with technology and not being able to turn off work. Maya explained,

My teachers are working 14 hours; they're not turning off. Between the small group instruction, answering parent emails, being on Zoom calls, office hours, and then also planning a week ahead of lessons, that's been a lot for them for time management. So, I have a staff that is completely exhausted.

Kamaria also stated, “I was getting emails from teachers at 2 in the morning. I think everyone was glued to technology and they couldn't turn it off.” Many of principals asserted that their teachers had a “harder time with work-life balance” when schools moved to a virtual environment and they were “working non-stop from home.” Principals in rural areas felt responsible for monitoring and supporting the mental health of teachers, particularly teachers who were socially isolated, who were responsible for supervising their own children while teaching online, and who were having a difficult time with work-life balance.

In response to the added stress that their teachers were experiencing, principals found ways to support teachers with their well-being. Principals reached out to teachers by calling them at home to check in with them and ask them questions like “What did you do for yourself today?” and “What are you going to do so you're not on the computer for 14 h?” Maya mentioned that she sent gifts to teachers' homes to show appreciation for their hard work. Clint spoke of his leadership team doing weekly check-ins with his teachers to check on their well-being. Kamaria and Ben both discussed “fitness days” that included yoga and meditation to help teachers decompress.

Principals also mentioned the importance of community-building with teachers to support them through the building closings. Many of the principals used ZOOM meetings to support teachers by creating an open forum for raising concerns and providing an opportunity to process their feelings. Many principals mentioned that they felt the need to create space for laughter and fun to help ease staff stress. Some principals even hosted “happy hours” to provide space for staff to socialize and spend time together. Maya discussed the actions she took to care for her staff:

During our weekly check-in meetings, it's really mostly just checking in on them and seeing how they're doing. We have a little giggle together. For Teacher Appreciation Week, I collected pictures of all of them, and I created a video and it was to that new Alicia Keys song, like ‘You're doing a good job,' just to show them like that you're really superheroes and you're doing amazing things.

A primary action of leaders is taking care of the staff, and in this case, the rural school principals responded to their staff by finding ways to care for them and appreciate them during the COVID crisis. Principals felt a sense of responsibility to be a caretaker because they did indeed carry the responsibility of caring for teachers and ensuring their mental health and well-being.

Social-Emotional Support for Students and Families

Principals in the study showed great care for their students and families. In discussing her own reactions to supporting families during the COVID pandemic, Beth commented, “As a principal, you are hardwired to care. I think [in a crisis situation] it's kind of hard to worry about anything other than the people in your charge.” All of the principals expressed concern for their families and students during the spring months and the impact of virtual schooling on both parents and students. Walter explained, “Parents are overwhelmed with trying to take care of their families and support their kids in virtual school—they are stressed.” David also stated, “Parents are working multiple jobs; there is no childcare, and families are struggling. Maya added that “parents are frustrated with students being home, with technology or work packets or whatever—they are tired and emotionally exhausted—they are just done.”

In response, rural school principals were determined to maintain a connection with parents and students. Walter commented,

With the building closed, it would be easy to just move on and worry about students in the fall, but the kids still needed us. Parents still needed us, so I insured that every administrator and teacher made contact with students either by phone or video three times a week.

Clint also discussed the importance of staying connected when he stated, “Leaders keep people connected—it is important to keep connections with families.” Susan explained that she provided “outreach services” by creating a call system so every parent was contacted by a staff member once a week for “check-ins and feedback.” Gabrielle spoke of “constantly communicating” with families and helping them set-up technology or finding social supports to help with a job loss. She mentioned that “every parent was contacted by a staff member weekly.” However, this commitment to weekly parent and student contact was not easily or readily achieved by all principals. Some of the rural principals discussed “not having correct phone numbers” or “finding parents with disconnected phones.” Maya shared that many of her parents “were frustrated with the amount of phone calls. Some of my parents asked us to quit calling.”

Numerous principals also suggested that the socialization aspect of school is equally as important as the academic aspect because children learn how to develop socially through interactions with other children, and they worried that children being physically isolated from one another caused anxiety and stress. Beth stated, “Kids need one-to-one support, motivation and encouragement, but if they are in a virtual environment, they don't have the emotional support they need.” Susan spoke of the social-emotional needs of her middle school students when she said, “Middle school is a time where peers become more important than parents. I worry that kids not being with their peers in schools is having an emotional toll on them.” Other principals spoke of students being alone because parents have to work. Jalon mentioned, “parents are working and kids are home alone—we had to find ways to support them.” Ben reflected on the virtual schooling was having on students:

I think the biggest challenge is quite honestly what all of us are facing, the fear of the unknown… What does it mean? kids trying to do things. I'm a middle school principal so we're asking kids and adolescents who don't have the best… They're not the best at navigating multiple tasks, and we're asking them to own their, own education in a different way, without the supports that are offered in a school, so I think that's in itself is a challenge because we're asking kids to basically teach themselves and to have the discipline that it takes in order to be successful.

In response, principals in the COVID leadership study took the lead to reduce student isolation as much as possible by establishing virtual schools and engaging students in “fun and play.” Susan spoke of her teachers “creating interactive lessons for students…teaching students how to cook or garden…or starting fitness clubs.” Walter spoke of limiting the time students spent on a computer to ease their stress, “We really tried to keep our virtual lessons to 2 h-a-day—kids cannot not emotionally handle longer than that.” Ben spoke of “online celebrations and spirit themes for classrooms—students wearing crazy hats or PJs” to keep students engaged. Other principals found ways to make home visits and stand on the curb to talk to children and parents. Maya spoke of delivering packets and doing home checks with teachers so they could check on kids. Gabrielle and Clint both created parent packets complete with social-emotional resources to support their children, and Kamaria created a virtual network for parents to have “virtual playdates for their [elementary-aged] kids.” By maintaining connections with students and parents, principals exhibited compassion and care for their students and families.

Although principals strived to maintain connections with students and keep them connected to the school, some of the principals expressed their frustration and worries about their parents and students. Maya and Jalon both spoke of parents and students who felt like school was done in March and did not want to stay connected to their teachers. Maya stated, “Once the state decided that no grade would be given after March 18th, many of my parents and students disappeared—they were like we get a really long summer break.” Jalon added that “we worried about the kids who didn't continue—in their minds, school was over.”

Constant and Calming Presence

Since teachers, students, and parents were overwhelmed by the COVID crisis, it was important for principals to be role models and to remain calm and consistent during the disruption. Jalon stated, “My most important job was keeping my staff level headed and remaining a voice of reason. I wanted to give them perspective—to create hope.” Susan also discussed remaining calm, “…my job as the principal is to keep calm at all times—regardless of anything else, that is most important.” Maya felt that her “most important role was to be supportive and be a role model for her staff.” She stated that “if I am okay, then they are okay—they take their cue from me.” In explaining what she learned about herself as a crisis leader, Kamaria stated,

I've learned and I'm a very resilient person. Through all of this, my thought process… And I don't know, this is a new learning for me. Is something that… Again, I feel like it's why I'm in this field, I do feel like it's a calling… I'm all about people. And for me, the biggest reward was at the end of the year, and my staff just coming back and saying that there's no way that we would have gotten through this had it not been for your calm, your positivity…your constant encouragement.

By remaining calm, positive, and hopeful during the COVID-19 crisis, principals helped to guide their schools and keep schools running as efficiently as possible.

Self-Reliance and Resiliency

One of the key findings in the study is the self-reliance and resiliency of rural school principals during a crisis. Many of the principals discussed the lack of guidance and decision –making in March when schools first started closing. David explained that when the school buildings closed in late March, his district provided limited guidance of what learning would look like, and he had to “figure it out” on his own. He explained, “There were some stipulations [from the district] but I still had to figure it [teaching and learning] out—what's it actually gonna' look like…I think the amount of resiliency of principals to respond in a crisis is amazing.” Jalon spoke of the lack of decision-making from central office, and how he took it upon himself to create a plan for when the buildings would close. He explained,

People in district office and the fear of making decisions stands out most for me as problematic because weeks prior I brought it up a few times to our team, our district level team that, ‘Hey, this is something real…' And it was discarded…then when it finally hit…the main decision makers were really indecisive…people were afraid to make decisions and wanted somebody else to tell them what to do…I didn't wait, I just made decisions for my school that I thought were best.

Jalon went on to explain that he worked with his leadership team and teachers to “do some research to figure out how they would finish the year.” Clint also spoke of having to develop his own plan without much guidance from the district or state. He stated, “Yeah, I mean I think the big thing was developing a continuity of learning program…the guidance from the state was ‘how are you going to keep this going?' So I had to put that plan together and then submit that to the state.” Ben spoke of having “to create a vision for the current COVID reality and work with teachers to set reasonable goals.” Maya also explained that “we all thought we would shut-down for a few weeks and be back. When we didn't come back, me and the other principal was like ‘Now What?' We had to figure it out.” All of the participants expressed they received limited guidance from their district on how to transition to schooling outside of the building, and they all had to develop their own plan.

Many of the rural school principals explained that they already had systems in place that helped them easily transition to a virtual world when the buildings closed. All of the participants in the study spoke of having pre-established Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) of teachers, and they used PLC meetings to not only support teachers but to also collaborate with teachers on meeting students' needs. Gabrielle stated that “my staff continued to collaborate and do professional learning every day through their PLC to make sure they were on the same page.” Susan spoke of the collaborative culture of her campus and said, “She didn't worry too much…teachers were the experts and they were highly involved in the decision-making—it is just the way we operate.” She further stated that “if you do the work upfront and you have good systems, then in a crisis, it will be okay—we've got this.” Gabrielle also alluded to trusting and empowering her teachers because “they have been well-trained. They had technology training every year—they took what they knew and ran with it.” Ben spoke of the professionalism of his teachers and how he knew they could continue to deliver instruction: “My teachers really understand the power of working together and I trusted them to do it because I've seen what they can do.” By creating systems and developing teachers in their everyday work, principals ensured that they were prepared to lead during the COVD-19 pandemic.

Advocates for Resources

When the school buildings closed in the spring because of COVID-19, rural principals responded as caretakers of their communities with advocacy and compassion. Some of them advocated for technology and broadband resources so students could continue to learn, and many of them also advocated for food services so students would have meals. Finally, they responded to the needs of their communities through communication and collaboration.

One of the inequities that was exemplified during the pandemic was the lack of resources needed for students to continue learning at home. Gabrielle explained, “Our community is a disadvantaged community with 93% of our students on free and reduced lunch, and most do not have access to technology.” Principals across the U.S. in the study spoke of the challenges of providing virtual learning for all students. David explained that he had “many homeless students who lived in shelters without computers or internet, and many other students whose parents couldn't afford a computer or internet.” Maya spoke of her rural community and how there was limited internet access:

Out of 455 students, 225 had no internet—it's like half the school and worse, most of them didn't have a device. I think that is the biggest inequity—we can have the best programs in the world, but if your kids don't have a device and they don't have internet, then it's not going to work.

In response, some of the principals worked with community leaders to “negotiate cheap internet or provide free internet or they “purchased hot spots and distributed them as needed.” Gabrielle asserted:

We did some work to partner with [name of company] as well as [name of company] and [name of company] in order to ensure that all kiddos had WiFi, so we again, had to communicate that with families, there were many times where we had to over the phone, explain how do you set up that Wi-Fi connection that [company] shipped out to you and you receive it. So we did do that. We made sure every kid could connect to the internet.

Some of the principals also found ways to provide free computers for children. David explained that one of his first concerns was making sure kids had computers or devices. He mentioned that he “deployed Ipads to all the kids.” Beth spoke of “partnering with [Name of Computer Company] to give Chrome books to all kids.” Through advocacy many of the rural school principals secured computer devices and broadband for their students so they could continue learning virtually at home; however, some of the rural principals, especially the principals who serve in remote areas, could not provide devices or internet. Maya explained that her community does not have access to reliable internet and commented, “I don't even have internet in my home because it isn't available. For most of the community the only places with internet are the school and library and both are closed to the public.” Beth also asserted that internet access “isn't always about money, it is about availability—we just don't have it in my area.” These two principals provided paper packets to students.

Principals not only advocated for technology resources for students, they also found ways to provide food for students on free and reduced lunch. David commented, “My first priority was making sure kids had food to eat—I worked with the district nutrition center and the National Guard to set up food distribution for families.” Many of the principals discussed coordinating with the district to provide groceries or meals for families and advocating for food distribution centers. Gabrielle explained, “My school was not one of the sites for food distribution, so I called the superintendent and said, ‘how do we get a food distribution site set up?' Two days later, we opened up food distribution on my campus and had 600 students coming through a day to get fed.” Maya spoke of collecting non-perishables and creating grocery bags to distribute to parents three times a week. All of the principals in the study recounted the importance of supplying food and setting up distribution centers for their students and their families; however, they were not able to provide food for all students and parents because of transportation issues. Some of the principals mentioned that they didn't see many of the students they knew might need the food because these students and their families lacked transportation to get to the distribution centers. Through their advocacy, many of the principals were able to help some children and families with food supplies. Moreover, rural school principals not only made decisions that impacted teaching and learning in the buildings, but they also played a leading role in attending to the livelihood of students and parents during the onset of the pandemic.

Discussion and Implications

Through this study, we explored how the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting quarantine shaped the leadership practices of rural school principals during the Spring months of 2020. During these early months, every school in the U.S. began closing its buildings, and principals across the country faced new challenges in dealing with wide-spread fear of the virus, constantly changing information, and switching to remote learning in less than a week's time. Many of the principals also had to worry about lack of technology, teachers working from home while caring for their own children, and food insecurity of their students. We interviewed 10 rural school principals across the U.S., and we broadly defined their leadership practices during the COVID-19 pandemic as caretaker leadership and developed five interrelated sub-themes to describe such leadership. We found that as caretakers, rural school principals responded to the social-emotional needs of teachers, students, and parents, remained a constant and calming presence for their communities, were self-reliant and resilient, and served as advocates for necessary resources.

Principals lead with their heart, and they are committed to communities that they serve (Rodriguez et al., 2009). Rural school principals wear multiple hats in their school-communities: leader, caretaker, pillar, etc. As such, the rural principals that participated in this study continued the work of caring for their school-community and exemplified the qualities of a meta-leader. The rural school principals in the study exemplified the characteristics of meta-leadership as they assessed the crisis situation created by the COVID-19 pandemic and responded to the needs of their school stakeholders. Marcus et al. (2019) expressed that meta-leaders are role models, who remain level headed and calm during moments of crises and “possess a depth of emotional intelligence” (p. 106). We found that the rural school principals in the present study were a calming presence for their communities and focused on the needs of their stakeholders. With limited direction from the district or the state, rural school leaders relied on their own expertise and knowledge to take care of their staff, their students, and their parents. Their self-reliance was amplified during the pandemic as they advocated for technology and broadband resources so that students could continue to learn; they maintained strong relationships with the community by providing support to families with food and resources; and they became the safe haven for their communities through virtual check-ins with students and helping families stay connected to the school community. As the architects of school culture, principals are asked to support teachers and students during normal school operations (Glanz, 2006), but this support was amplified during the COVID crisis.

Although the leadership practices of a meta-leader are often amplified during a crisis, a meta-leader exhibits these practices in everyday routines (Marcus et al., 2019). As we think about the leadership practices of rural school principals at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and quarantine, we realize that their leadership practices, in general, did not change. This, perhaps, is due in part to leading in a rural context. Rural principals, particularly those in rural remote areas, often lead and operate with fewer resources than their suburban and urban counterparts. Therefore, although the context of schooling shifted because of the quarantine, the principals' overall caretaking of their community changed very little. For example, rural principals had to think about virtual learning for their students, realizing that broadband access is limited, at best, in many of their communities. Children who live in impoverished rural areas often lack technology resources such as computers and internet access (Ramon et al., 2019). The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) reports that over 21 million Americans lack internet access and 69% of these Americans live in rural areas (Poon, 2020). The rural principals in this study found themselves negotiating with internet companies to provide internet services for their students.

Rural principals also paid closer attention to teacher burnout due to stress of the unknown. Teachers in rural areas tend to suffer stress and burnout at higher rates than their urban and suburban peers due to low levels of professional support, professional isolation, and feelings of inadequacy in working with students who live in poverty (Hinds et al., 2015). Unlike their suburban and urban peers, rural school principals have the added burden of attracting and retaining qualified teachers to hard-to-staff schools, and they do so by caring for their teachers and nurturing them in their everyday work (Holmes et al., 2019). Community cohesiveness in rural contexts often makes up for the lack of resources that is evident in many rural communities.

The data in this study reflect the findings of 10 rural principals across the U.S.; therefore, we do not seek to generalize to all rural school principals. We do not minimize the struggles that rural school principals are currently facing because of the COVID-19 pandemic, but we offer a view of how rural school principals can respond in times of crises. Although it is not easy, principals can be meta-leaders and exhibit caretaker leadership by caring for their stakeholders; advocating for their stakeholders as much as possible; remaining calm, positive, and hopeful; and leading with compassion and understanding. The findings from this study also indicate that being a meta-leader and serving as an advocate for all stakeholders is imperative to responding well during a crisis; however, this type of leadership is required of rural principals in their daily work as a school leader. Rural principals responded as meta-leaders during the pandemic and quarantine because they are meta-leaders in their normal routines. Rural school leaders understand what it means to lead schools that are geographically isolated, and they understand the challenges of (a) retaining and supporting quality teachers; (b) working with students and families who live in poverty; and (c) providing a quality education with a lack of resources. In essence, rural school principals lead in crisis every day. Their unique context has empowered them to become self-reliant and resilient so that they can be caretakers of their school communities. We examined their leadership practices during a time of crisis, but we found that the crisis only amplified their everyday leadership practices. Ultimately, the rural school principals in this study responded to the COVID-19 pandemic, the way they would in their every day school leadership practices—they took care of their people.

Implications

In reflecting on rural school principals' leadership and care during the onset of the COVID 19 pandemic, some findings became more apparent: Some rural schools have been facing a pandemic for quite some time. To be clear, this is not to make light of the global pandemic we current face, but it is to highlight the inequities and inadequacies present in some rural schools and communities. For example, there is a lack of infrastructure for broadband access in some rural areas, and that became more evident during the pandemic. Principals found themselves negotiating with broadband companies, which should be a basic utility in a country such as the U.S. The lack of infrastructure for broadband access caused students to lag behind urban and suburban students, who have better broadband connectivity.

In addition to the lack of infrastructure for better access to the outside world, the pervasive poverty in some rural communities compounds their day-to-day life. Not only did rural principals work to make sure students had access to instruction, but they also worked to make sure families were fed. The poverty rate in rural areas is consistently high, and the onset of COVID 19 further burdened some rural residents. As research indicates, the school is the hub in rural communities, and this is evidenced in the ways that principals cared for families' daily needs at the onset of the pandemic.

Although rural communities lack infrastructure to better connect to the outside world and poverty is widespread in most rural communities, the cohesive community structure makes the connections tighter among individuals. This, in the end, is how rural schools and communities thrive. Strong school-community relationships not only enhance the learning environment in rural contexts, but it also provides a space in which stakeholders care for each other—as the principals did in our study. This level of engagement on behalf of principals makes the home-school relationship more intertwined than might occur in non-rural places and can benefit students' short-term and long-term trajectories. Moreover, this type of care as demonstrated by rural school principals, might also transfer to teachers. That, in the long run, has the potential to further shape teacher-student relationships.

As evidenced in our study, rural principals lead with their heart and are people-centered. They are regarded as pillars and politicians in their respective rural communities, and most wear those given titles with badges of honor. Thus, the leadership exhibited by the principals in this study is no different in the leadership they exhibit in their daily work—as the rural context requires it. Given the nature of rural school leadership, our study also highlights the need for educational leadership programs to broaden their concepts. To date, most educational leadership programs are developed from an urban-centric framework, thus highlighting the needs of urban schools and their communities. Few programs exist that highlight rural school leadership, although 19% of public school students are educated in rural schools [Johnson et al., 2014; National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), 2016]. Thus, a major implication of our study is to highlight the work of rural school leaders and scholars' responsibilities to provide more frames for the work of rural leaders as individuals seek paths to the position.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Pennsylvania. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

SH led the effort for this manuscript by coding data and bringing forth the original idea. JF contributed to the literature review and helped the team think about how the manuscript should be conceptualized. SW contributed to the methods section and edited the final version of the paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the principals who shared their experiences as part of the Leading in Crisis study. The study was a collaborative data collection effort organized by Jonathan Supovitz of the Consortium for Policy Research in Education at the University of Pennsylvania. The research team included: Erin Anderson (University of Denver), Bodunrin Banwo (University of Minnesota), Bradley Carpenter (Baylor University), Joshua Childs (University of Texas, Austin), Chantal Francois (Towson University), SH, (University of Tennessee, Knoxville), Lea Hubbard (University of San Diego), Maya Kaul (University of Pennsylvania), Julianna Kershen (University of Oklahoma), Hollie Mackey (University of North Dakota), Gopal Midha (University of Virginia), Daniel Reyes-Guerra (Florida Atlantic University), Nicole Simon (City University of New York), Corrie Stone-Johnson (University at Buffalo), Bryan A. VanGronigen (University of Delaware), Jennie Weiner (University of Connecticut), and SW, (Michigan State University). More about the study can be found at https://www.cpre.org/leading-crisis.

References

Ali, W. (2017). A review of situational leadership theory and relevant leadership styles: options for educational leaders in the 21st century. J. Adv. Soc. Sci. Hum. 3, 36401–36431. doi: 10.15520/jassh311263

Arnold, M. L., Newman, H. H., Gaddy, B., and Dean, C. B. (2005). A look at the condition of rural education research: setting a direction for future research. J. Res. Rural Educ. 20, 1–25. Available online at: http://www.keystone-institute.org/pdf/JRRE_05.pdf

Ashton, B., and Duncan, H. E. (2012). A beginning rural principal's toolkit: a guide for success. Rural Educ. 34, 1–13. doi: 10.35608/ruraled.v34i1.405

Barley, Z. A., and Beesley, A. D. (2007). Rural school success. what can we learn? J. Res. Rural Educ. 22, 1–16. Available online at: https://cep.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Rural-School-Success-What-can-we-learn.pdf

Barrett, N., Cowen, J., Toma, E., and Troske, S. (2015). Working with what they have: professional development as a reform strategy in rural schools. J. Res. Rural Educ. 30, 1–18. Available online at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1071136

Bauch, P. A. (2001). School-community partnerships in rural schools: leadership, renewal, and a sense of place. Peabody J. Educ. 76, 204–221. doi: 10.1207/S15327930pje7602_9

Brown, D. L., and Schafft, K. A. (2011). Rural People and Communities in the 21st Century: Resilience and Transformation. Boston, MA: Polity Press.

Browne-Ferrigno, T., and Maynard, B. (2005). Meeting the learning needs of students: a rural high-need school district's systemic leadership development initiative. Rural Educ. 26, 5–18. doi: 10.35608/ruraled.v26i3.504

Burton, M. (2013). Storylines about rural teachers in the United States: a narrative analysis of the literature. J. Res. Rural Educ. 28, 1–18. Available online at: http://sites.psu.edu/jrre/wp-content/uploads/sites/6347/2014/02/28-12.pdf

Bushnell, M. (1999). Imagining rural life: schooling as a sense of place. J. Res. Rural Educ. 15, 80–89. Available online at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.515.2927&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Casto, H. (2016). Just more thing I have to do: school-community partnerships. School Commun. J. 26 139–162.

Clarke, S., and Stevens, E. M. (2009). Sustainable leadership in small rural schools: selected Australian vignettes. J. Educ. Change 10, 277–293. doi: 10.1007/s10833-008-9076-8

Curtin, L., and Cohn, T. J. (2015). Overview of Rural Communities: Context, Challenges and Resilience. Available online at: https://www.apa.org/pi/aids/resources/exchange/2015/01/rural-communities (accessed August 25, 2020).

Du Plessis, P. (2014). Problems and complexities in rural schools: challenges of education and social development. Mediterran. J. Soc. Sci. 5, 1109–1117. doi: 10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n20p1109

Farrigan, T. (2017). Rural Poverty & Well-Being. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture - Economic Research Service. Available online at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-poverty-well-being/.

Forner, M., Bierlein-Palmer, L., and Reeves, P. (2012). Leadership practices of effective rural superintendents: connections to waters and Marzano's leadership correlates. J. Res. Rural Educ. 27, 1–13. Available online at: https://jrre.psu.edu/sites/default/files/2019-08/27-8.pdf

Fusarelli, B. C., and Militello, M. (2012). Racing to the top with leaders in rural, high poverty schools. Plann. Chang. 43, 46–56. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ977546.pdf

Glanz, J. (2006). What Every Principal Should Know About Cultural Leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Hamilton, L. S., Kaufman, J. H., and Diliberti, M. (2020). Teaching and Leading Through a Pandemic: Key Findings From the American Educator Panels Spring 2020 COVID-19 Surveys. Available online at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA168-2.html (accessed August 17, 2020).

Hansen, C. (2018). Why rural principals leave. Rural Educ. 39, 41–53. doi: 10.35608/ruraled.v39i1.214

Hersey, P., and Blanchard, K. (1977). Management of Organizational Behavior. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hildreth, D., Rogers, R. H., and Crouse, T. (2018). Ready, set, grow: preparing and equipping the rural school leader for success. Alabama J. Educ. Leadersh. 5, 39–52. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1194721.pdf

Hinds, E., Jones, L. B., Gau, J. M., Forrester, K. K., and Biglan, A. (2015). Teacher distress and the role of experiential avoidance. Psychol. Sch. 52, 284–297. doi: 10.1002/pits.21821

Hohner, J., and Riveros, A. (2017). Transitioning from teacher leader to administrator in rural schools in southwestern Ontario. Int. J. Teach. Leadersh. 8, 43–55. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1146804.pdf

Holmes, B., Parker, D., and Gibson, J. (2019). Rethinking teacher retention in hard-to-staff schools. Contemp. Issues Educ. Res. 12, 27–32. doi: 10.19030/cier.v12i1.10260

Hsieh, H.-F., and Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualit. Health Res. 15, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

Johnson, J., Showalter, D., Klein, R., and Lester, C. (2014). Why Rural Matters 2013-2014: The Condition of Rural Education in the 50 States. Washington, DC: Rural School and Community Trust.

Klar, H. W., and Brewer, C. A. (2014). Successful leadership in a rural, high-poverty school: the case of County line middle school. J. Educ. Admin. 52, 422–445. doi: 10.1108/JEA-04-2013-0056

Kvale, S. (1996). The 1,000-page question. Qualitat. Inq. 2, 275–284. doi: 10.1177/107780049600200302

Latham, D., Smith, L. F., and Wright, K. A. (2014). Context, curriculum, and community matter: Leadership practices of primary school principals in the Otago province of New Zealand. Rural Educ. 36, 1–12. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1225576.pdf

Lavalley, M. (2018). Out of the Loop: Rural Schools are Largely Left out of Research and Policy Discussions, Exacerbating Poverty, Inequity, And Isolation. National School Boards Association, Center for Public Education. Retrieved from: https://www.nsba.org/News/2018/Out-of-the-Loop.

Lock, G., Budgen, F., and Lunay, R. (2012). The loneliness of the long-distance principal: Tales from remote Western Australia. Austr. Int. J. Rural Educ. 22, 65–77. Available online at: https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=664515896186197;res=IELHSS

Marcus, L. J., McNulty, E. J., Henderson, J. M., and Dorn, B. C. (2019). Crisis, Change, and how to Lead When it Matters Most: You're it. New York, NY: Hachette Book Group.

Marcus, L. J. (2006). Meta-Leadership 2.0: More Critical than Ever. Domestic Preparedness. Available online at: https://www.domesticpreparedness.com/commentary/meta-leadership-2.0-more-critical-than-ever/.

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (2016). Selected Statistics from the Public Elementary and Secondary Education Universe: School Year 2014-15. Table 4. National Center for Education Statistics

Parson, L., Hunter, C. A., and Kallio, B. (2016). Exploring educational leadership in rural schools. Plann. Chang. 47, 63–81. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1225156.pdf

Pashiardis, P., Savvides, V., Lytra, E., and Angelidou, K. (2011). Successful school leadership in rural contexts: the case of cyprus. Educ. Manag. Admirat. Leadersh. 39, 536–553. doi: 10.1177/1741143211408449

Poon, L. (2020). There are Far More Americans Without Broadband Access Than Previously Thought. Bloomberg, IL: Bloomberg Citylab.

Preston, J. P. (2012). Rural and urban teaching experiences: narrative expressions. Alberta J. Educ. Res. 58, 41–57.

Preston, J., and Barnes, K. (2017). Successful leadership in rural schools: cultivating collaboration. Rural Educ. 8, 6–15. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1225156.pdf

Ramon, C. C., Peniche, R. S., and Cisneros-Cohernour, E. (2019). Challenges of teachers in an effective rural secondary school in Mexico. J. Educ. Learn. 8, 143–149. doi: 10.5539/jel.v8n1p143

Rodriguez, M. A., Murakami-Ramalho, E., and Ruff, W. G. (2009). Leading with heart: Urban elementary principals as advocates for students. Educ. Consider. 36, 8–13. doi: 10.4148/0146-9282.1164

Roulston, K. (2010). Reflecting Interviewing. A Guide to Theory and Practice. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. doi: 10.4135/9781446288009

Schaefer, A., Mattingly, M. J., and Johnson, K. M. (2016). Child poverty higher and more persistent in rural America. Carsey Res. Natl Issue Brief 97, 1–8. doi: 10.34051/p/2020.256

Schafft, K. A., and Jackson, A. Y. (2010). Rural Education for the Twenty-First Century: Identity, Place, and Community in a Globalizing World. University Park, PA: Penn State Press.

Semke, C. A., and Sheridan, S. M. (2012). Family-school connections in rural educational settings: a systematic review of the empirical literature. Sch. Commun. J. 22, 21–47. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ974684.pdf

Showalter, D., Klein, R., Johnson, J., and Hartman, S. L. (2017). Why Rural Matters 2015-2016: Understanding the Changing Landscape. Available online at: http://www.ruraledu.org (accessed August 17, 2020).

Southworth, G. (2004). Primary School Leadership in Context: Leading Small Medium and Large Sized Schools. Milton Park: Taylor and Francis.

Starr, K., and White, S. (2008). The small rural school principalship: key challenges and cross-school responses. J. Res. Rural Educ. 23, 1–12. Available online at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ809597

Surface, J. L., and Theobald, P. (2014). The rural school leadership dilemma. Peabody J. Educ. 89, 570–579. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2014.955753

Ulferts, J. D. (2016). A brief summary of teacher recruitment and retention in the smallest Illinois rural schools. Rural Educ. 37, 14–24. doi: 10.35608/ruraled.v37i1.292

Versland, T. M. (2013). Principal efficacy: Implications for rural ‘grow your own' leadership programs. Rural Educ. 35, 13–22. doi: 10.35608/ruraled.v35i1.361

Keywords: rural, rural principal, COVID-19, leadership, meta-leadership

Citation: Hayes SD, Flowers J and Williams SM (2021) “Constant Communication”: Rural Principals' Leadership Practices During a Global Pandemic. Front. Educ. 5:618067. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.618067

Received: 16 October 2020; Accepted: 07 December 2020;

Published: 06 January 2021.

Edited by:

Michelle Diane Young, Loyola Marymount University, United StatesReviewed by:

Sheri Williams, University of New Mexico, United StatesKimberly Kappler Hewitt, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, United States

Copyright © 2021 Hayes, Flowers and Williams. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sheneka M. Williams, d2lsbDM2NzdAbXN1LmVkdQ==

Sonya D. Hayes

Sonya D. Hayes Jamon Flowers

Jamon Flowers Sheneka M. Williams

Sheneka M. Williams