- Department of Inclusive and Special Needs Education, University of Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

The social participation of students with disabilities in general education is lagging behind and negative peer attitudes are often mentioned as the main barrier. Contact Theory can serve as a rationale for interventions that aim to promote positive attitudes and thereby also the social participation of students with disabilities. This review aims to elucidate to what extent the intervention components contact and information are related to both the attitudes of typically developing peers and the social participation of students with disabilities. The results indicate that interventions combining contact and information are associated with more positive attitudes and one theme of social participation (i.e., interactions). It was, surprisingly, not possible to study the mediating role of peer attitudes as no studies addressed this. In sum, Contact Theory can be validated in primary inclusive education regarding typically developing students' attitudes, but only partially regarding the social participation of students with disabilities.

Introduction

The inclusion of students with disabilities in regular schools is increasingly promoted worldwide in the last few decades. An important philosophy behind inclusive education is that the chances for an optimal social participation should be maximized in a regular-education setting (see article 24 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with a Disability, United Nations, 2006). Social participation is an important condition for students' development, because students develop social skills and gather knowledge while interacting with peers (Bedell and Dumas, 2004; Pepler and Bierman, 2018). In the context of inclusive education, social participation can be seen as an umbrella term including four themes: the acceptance of students with disabilities by their classmates (e.g., social preference, or rejection), the presence of positive social contact/interaction between students with disabilities and their classmates (e.g., by playing together), social relationships/friendships between students with and without disabilities, and the students' perception they are accepted by their classmates (e.g., social self-perception) (Koster et al., 2009). This operationalization shows that social participation is mainly about actual, overt behavior, in this case, of peers ensuring participation of the student with disabilities. Without the facilitation of typically developing peers, students with disabilities are unable to participate. Evidently, students with disabilities should also seize opportunities to participate.

Even though the enrolment of students with disabilities in regular classrooms increases the opportunities for contact with typically developing peers, social participation does not always occur spontaneously for students with disabilities (Guralnick et al., 2007; Pijl et al., 2008). Numerous international studies have shown that students with disabilities experience difficulties at all four themes of social participation in regular-education settings compared to their typically developing peers (e.g., Hestenes and Carroll, 2000; Pavri and Monda-Amaya, 2000; Cambra and Silvestre, 2003; Margalit, 2004; Odom et al., 2006; Frostad and Pijl, 2007; Koster et al., 2007, 2010; Pijl et al., 2008; Kasari et al., 2011; Chung et al., 2012; Nepi et al., 2015; Schwab, 2015; Avramidis et al., 2018). This precarious situation can take away a sense of belonging at school, and can negatively impact the self-image, self-confidence, motivation and school performance (see Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd, 2016; Bukowski and Raufelder, 2018). Consequently, a downward spiral can emerge; when students' social participation is limited, they have fewer opportunities to develop their social competence, which leads to fewer chances to (positive) social contact with their peers, and even less social participation as a result (Van Geert and Steenbeek, 2005; Carter and Hughes, 2007; Frostad and Pijl, 2007; Steenbeek and van Geert, 2008).

The attitudes of typically developing peers toward children with disabilities are often mentioned as influencing the social participation of the latter group (World Health Organization, 2007). The relationship between peers' attitudes and their facilitation of the social participation of students with disabilities has been established in several studies (Vignes et al., 2009; Godeau et al., 2010; Bossaert and Petry, 2013; De Boer et al., 2013). This indicates that attitudes are an important starting point when aiming to promote the social participation of students with disabilities. An attitude can be defined as “a psychological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some favor or disfavor” (Eagly and Chaiken, 1993, p. 1), and consists of three evaluative responses: a cognitive, an affective and a behavioral evaluative response. The cognitive attitude includes thoughts and beliefs, the affective attitude refers to one's feelings regarding the attitude object, and the behavioral attitude refers to the predisposition to act in a certain manner (behavioral intentions). The attitudes of typically developing students toward students with disabilities are predominantly neutral to negative (Rose et al., 2011; De Boer et al., 2012; Bates et al., 2015), with the youngest students being the most negative (Dyson, 2005; Nowicki, 2006; De Boer et al., 2014). According to the Theory of Planned Behavior, the affective and cognitive attitudes predict the behavioral attitude, which, in turn, predicts behavior (Ajzen, 1991; see also Ajzen et al., 2019). Thus, students' beliefs and feelings about disabilities guide their behavioral intentions, and thereby, affect their social behavior toward a peer with a disability. This means that negative attitudes toward disabilities can be seen as a barrier to the social participation of students with disabilities (Nowicki and Sandieson, 2002; Vignes et al., 2009; Bossaert et al., 2011), as typically developing students might limit behaviors facilitating social participation, or even avoid peers with disabilities.

Several factors play a role in attitude development. Already at an early age, students develop the awareness of social categories, which, when unchallenged, may lead to the emergence of explicit biases in favor of one's own category (Bigler and Liben, 2006; Killen and Rutland, 2011). This implies that students can start to develop negative attitudes from early age, especially toward people who are visibly different (Raabe and Beelmann, 2011). Furthermore, students' attitudes are shaped by their repeated direct and indirect experiences with the attitude object and the students' primary social group (i.e., peers, parents/family, and teachers) (Eagly and Chaiken, 1993; Favazza et al., 2016). Students' attitudes toward their peers with disabilities are also believed to be strongly influenced by their degree of knowledge about disabilities (Vignes et al., 2008; Ison et al., 2010).

Regarding the promotion of peers' attitudes, and thereby possibly also of the social participation of students with disabilities, both contact and information have been mentioned as important intervention components (Cambra and Silvestre, 2003; Lindsay and Edwards, 2013; Bates et al., 2015). The rationale for these two components can be found in the well-known and established Contact Theory of Allport (1954). First, Allport hypothesized that positive interpersonal contact is likely to reduce existing prejudice between the so-called ingroup (i.e., the social group with which someone identifies) and the outgroup (i.e., the social group with which someone does not identify). In order to obtain beneficial effects, the contact should allow for true acquaintance and chances to exchange knowledge. This kind of contact will allow members of the ingroup and outgroup to learn about each other and see how similar they really are (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2008). Contact that is only casual or superficial may achieve the opposite and reinforces stereotypes instead of breaking them down (Allport, 1954; Aberson, 2015). Without further acquaintance, people are more sensitive to only perceive signs that will confirm their already existing negative attitudes (e.g., confirmation bias). Allport's Contact Theory has been investigated to great extent, and direct contact has proven to be effective in reducing prejudice and promoting attitudes toward several “outgroups” (see meta-analysis by Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006). The effect of contact has also been established with regard to students' attitudes toward peers with disabilities. Positive associations between contact and students' attitudes toward peers with disabilities have been found in systematic reviews regarding both natural contact (MacMillan et al., 2014) and manipulated contact (Lindsay and Edwards, 2013). Furthermore, the meta-analysis of Armstrong et al. (2017) indicated that interventions utilizing direct contact have a moderate effect on attitudes (d = 0.55). Second, Allport believed that providing information was a valuable addition to the contact opportunities. New and reliable information can correct existing stereotypes and enables the adjustment of thoughts and beliefs, whereby positive attitudes will be promoted (Allport, 1954; see also Theory of Planned Behavior: Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975). In order to break down negative generalizations, it is important to provide information originating from different and creditable sources and to repeat this information. Otherwise new information can be distorted or forgotten when it does not match the already existing knowledge, stereotype or attitude a students has (Allport, 1954; Bigler and Liben, 2006). Data from the systematic review by Lindsay and Edwards (2013) indicates that interventions utilizing information successfully improve knowledge about disabilities. With regard to attitudes, their findings were mostly positive as well, though, limited to studies with low causal inference.

Considering the negative consequences of the difficulties students with disabilities experience in their social participation, it is important to establish how this situation can be improved. Based on the aforementioned literature, the question arises whether the Contact Theory (1954) can be applied in inclusive education, and thus whether direct contact and information about disabilities can also promote the social participation in a direct way and/or in a mediated way via attitude. Following Allport's Contact Theory, contact and information might not only be beneficial in promoting attitudes but can also positively impact negative behavior such as rejection and avoidance (i.e., negative subthemes of social participation). However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have applied the Contact Theory in the inclusive-education setting, both by investigating the impact of contact and information, and by relating to the social participation of students with disabilities as well as the attitudes of their typically developing peers. Until now, it seems that researchers have chosen only attitudes as their area of focus. Several reviews and meta-analyses confirm the importance of the contact component in promoting the attitudes toward students with disabilities (e.g., Lindsay and Edwards, 2013; MacMillan et al., 2014; Armstrong et al., 2017), yet no attention has been paid to its impact on the four aforementioned themes of social participation. Inversely, one review about educational interventions indicated that group activities and support groups for students with disabilities can successfully promote the social participation of students with disabilities (Garrote et al., 2017). However, it remains unclear whether the effects could be due to contact and/or information, since this review has no clear theoretical framework. Moreover, the authors consider the typically developing peers predominantly as co-interveners rather than co-target students, thereby ignoring the important mediating role their attitudes may play in the process of change. Clear knowledge on how the social participation of students with disabilities can be promoted, while acknowledging the influence their typically developing peers may have, is still lacking.

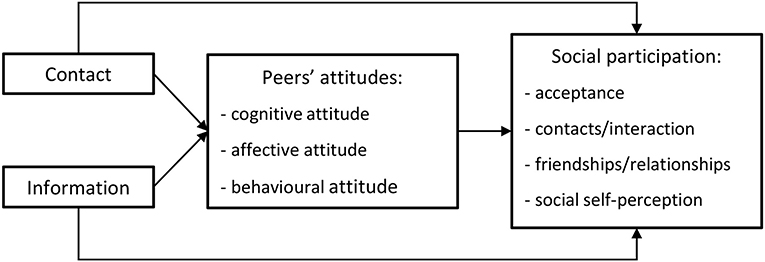

Accordingly, this study was set up to bridge these gaps in knowledge by applying the Contact Theory to the primary inclusive-education setting and to use it as a conceptual model for promoting the social participation of students with disabilities with direct contact and information (see Figure 1). The aim is to test this model systematically using the existing literature, and thereby the applicability of Contact Theory in inclusive education, by answering the following research questions:

(1) To what extent are contact with, and information about (students with) disabilities related to the attitudes of typically developing peers, and are these relationships different according to background variables?

(2) To what extent are contact with, and information about (students with) disabilities related to the social participation of students with disabilities, and are these relationships different according to background variables?

(3) To what extent are the attitudes of typically developing students toward peers with disabilities mediating between contact and information and the social participation of students with disabilities?

Figure 1. Conceptual model displaying the expected relationships between the intervention components (contact and information) and peers' attitudes and social participation.

Method

Search Procedure

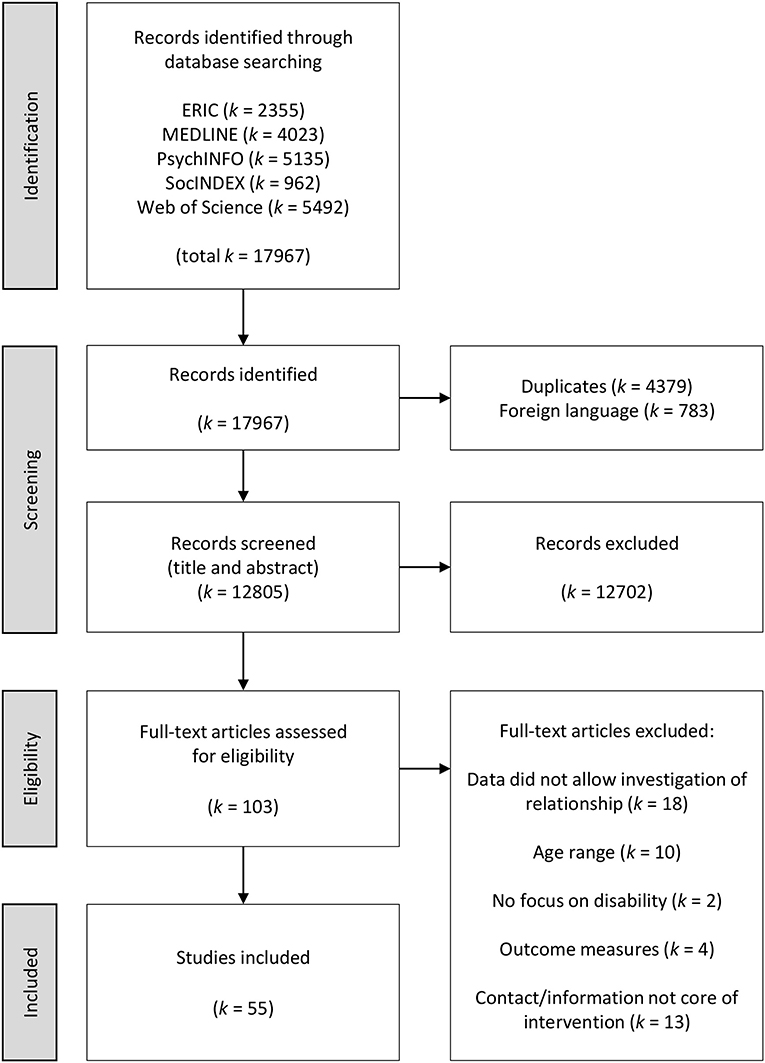

This systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). A systematic search was conducted in August 2018 using the browsers ERIC, MEDLINE, PsychINFO, SocINDEX, and Web of Science. Limits were set for publication date (onset January 1990) and source type [international scientific (peer-reviewed) journals]. The limit for publication date was driven by the ratification of the Salamanca Statement and the Framework for Action (UNESCO, 1994) and preceding educational changes. Articles written in any language other than English were manually removed.

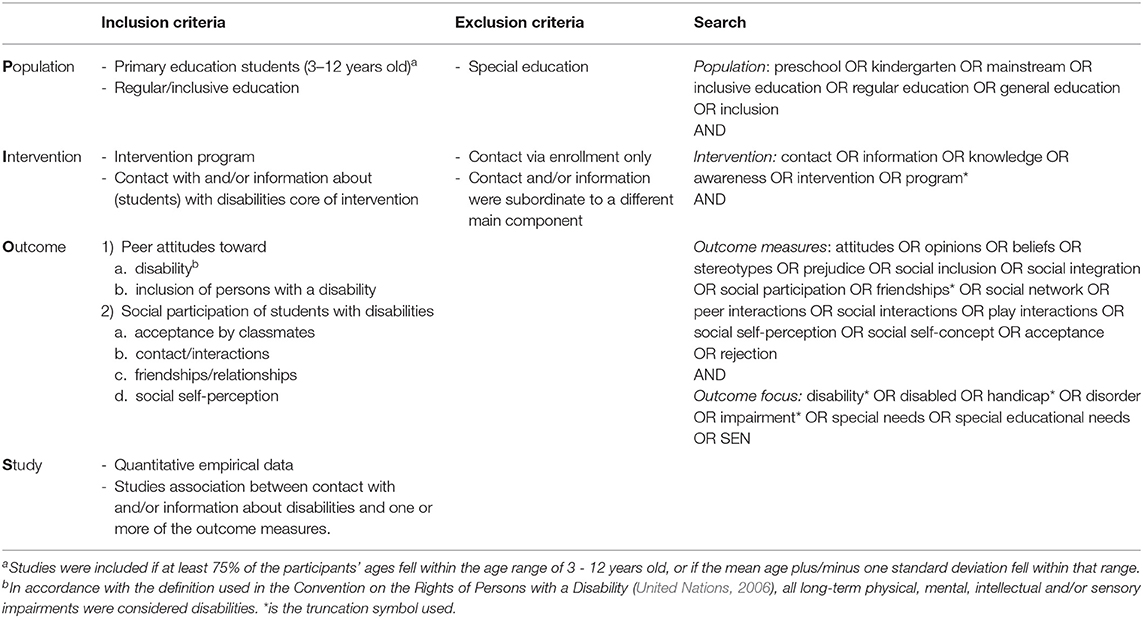

To be included in this review, a study had to investigate the association between an intervention utilizing contact with and/or information about (students with) disabilities (intervention) and one or more outcome measures related to attitudes toward (the inclusion of students with) disabilities and/or the social participation of students with disabilities (outcome) in a primary regular or inclusive education setting (population). A detailed PICOS model of the eligibility criteria as well as the utilized search term can be found in Table 1.

Selection Procedure

The search via the databases yielded 12,805 unique articles, after duplicates and non-English articles were removed. The selection procedure was carried out in two phases. First, the records were screened by reading titles and abstracts. A record was excluded in this phase when the title and/or abstract contradicted the inclusion criteria (e.g., investigation of adults' attitudes). When the title provided sufficient information for exclusion (e.g., the title mentioned the effect of medication on bowel problems), the abstract of that record was not read. After screening the titles and abstracts, 103 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Second, the full-text articles were retrieved and reviewed for eligibility. A total of 55 articles was included in this review (see Figure 2 for a flowchart of the selection process).

The first author (FR) carried out both phases of the selection procedure. To ascertain reliability, a second reviewer (EK) also reviewed a random sample of the records (10% in phase 1 and 20% in phase 2). Reviewers agreed on 99% of the records (κ = 0.73) in phase 1 and on 95% of the full-text articles (κ = 0.89) in phase 2. Any discrepancies that arose during the process were resolved through discussion among the authors.

Data Extraction

The first author extracted all relevant data from the included full-text articles using a data extraction form. First, the descriptive characteristics of the study [e.g., authors, date, country, research design, and sample (both typically developing participants and participants with disabilities)] were extracted. When applicable, data on sub studies or on different interventions were extracted separately. If studies reported on different age groups separately, only data on relevant age groups were extracted.

Second, a description of the intervention components contact and information was extracted. Something was considered contact when typically developing students were in direct contact with a person with a disability as part of the intervention (either a classmate, or someone they did not know before, such as a co-presenter with a disability). Something was considered as information when students had been provided with information about disabilities as part of the curriculum or intervention, or when the topic was formally being discussed within the school context. Indirect or extended contact (e.g., the use of storybooks about a character with a disability) was also considered as information.

Third, data on the associations between the intervention components and the outcome variables were extracted. The outcome variables fell into two categories: attitudes and social participation. With regard to attitude, a measure was classified as cognitive attitude when it reflected opinions or beliefs, as affective attitude when it reflected feelings, as behavioral attitude when a predisposition to act in a certain way was measured, or as general attitude in case the measure comprised more than one attitude component and data were not reported separately. The outcome variables were classified as social participation, when the measure reflected real behavior (e.g., interactions between students with and without a disability via observations), sociometric data about acceptance and friendships or self-reports of the social self-concept of participants with a disability. Data collected from other informants than focus students or classmates (e.g., parents and teachers) were not included in this review. In cases where more indicators of one outcome variable were present (e.g., two questionnaires measuring behavioral intentions), all indicators were extracted as separate associations.

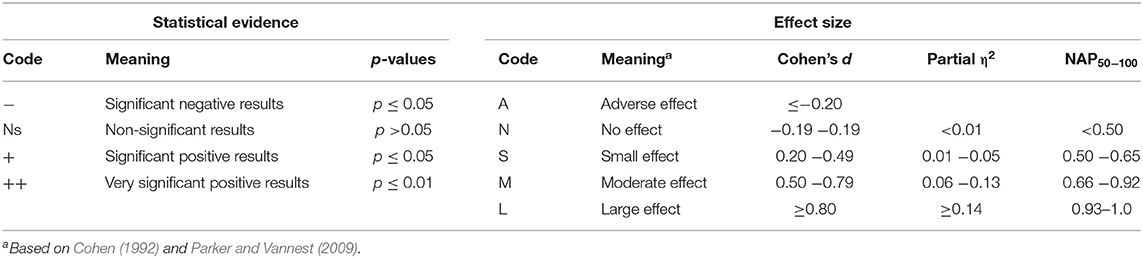

Data on the association between contact and/or information and the outcome measure(s) was extracted via both statistical evidence and effect size (see Table 2). When the effect size was not reported, it was calculated via the online calculator of Lenhard and Lenhard (2016), if the data in the full-text article allowed to. In order to get an estimate of the evidence from single and/or multiple case study designs, the value for the non-overlap of all pairs effect size (NAP) was calculated (Parker and Vannest, 2009; Parker et al., 2011). Data on both post-intervention associations as well as follow-up associations was extracted. In cases differential associations were investigated (i.e., differences due to background variables, for example age or gender), this data was extracted also. No prior selection was made with regard to these background variables; all investigated background variables were included.

Lastly, the level of evidence of each study was determined using the model of Dunst et al. (1989). In this model a distinction is made between three levels of causal inference based on study design and study characteristics: (1) low (e.g., pre-experimental designs), (2) low to moderate (e.g., quasi- and true experimental designs), and (3) moderate to high (e.g., mixed designs and multiple baseline designs). The level of evidence was assigned in correspondence with the data and the conducted analyses that covered the association(s) of interest.

Results

General Description of the Selected Studies

Sample sizes differed between studies and ranged from 46 to 576 typically developing participants in studies focusing on attitudes and from 1 to 98 participants with a disability in studies focusing on social participation. The majority of studies focused on one type of disability only, whereas 12 studies focused on multiple types of disability. The most common disability types studied were autism spectrum disorder (24%), intellectual disability (18%), and physical disability (14%). In addition, some studies did not specify which disabilities had their focus, but used general wordings like disability/special needs (5%). Several studies focused on one particular age, whereas others included a broader range of ages. Overall, all ages in the target range (3–12 years) were represented proportionally. The level of evidence (i.e., causal inference) differed between studies; 40% had low causal inference, 22% low to moderate causal inference, and 38% moderate to high causal inference.

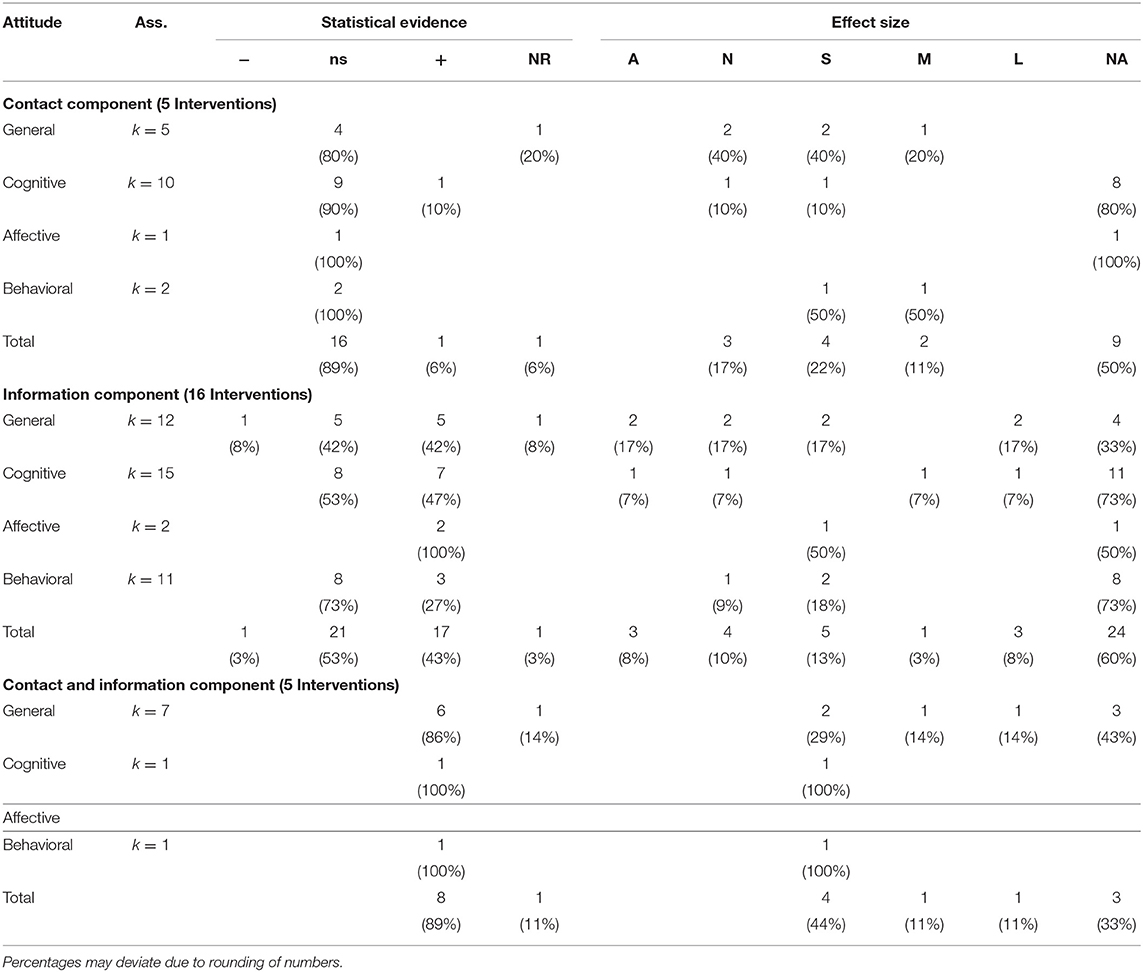

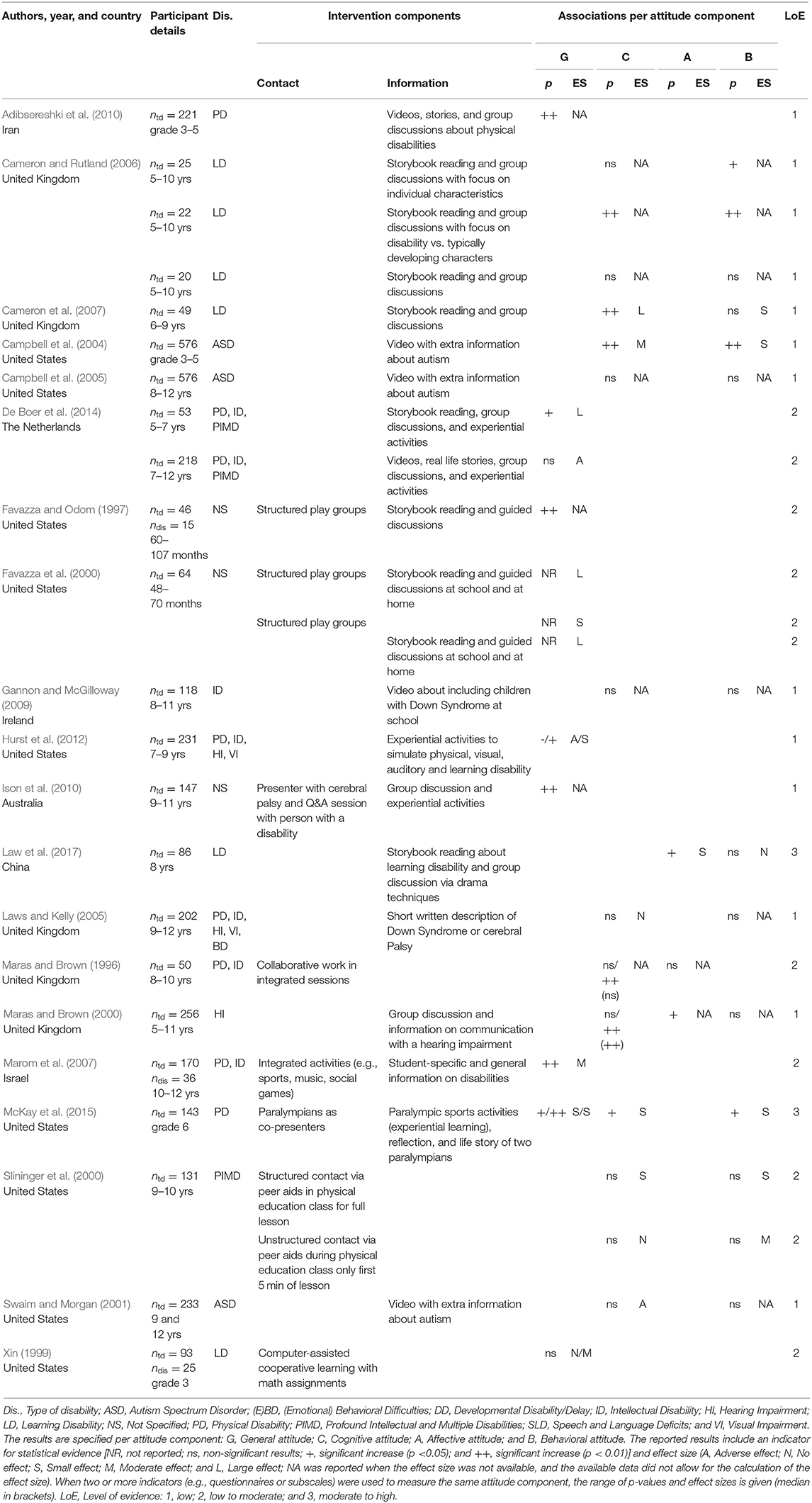

Associations Between Contact and Information and Attitudes

Overall, a differential relationship was found between the extent to which the variables contact with and information about (students with) disabilities are related to the attitudes of typically developing peers. This relationship differed according to the utilized intervention components. In total, 26 interventions—reported in 20 articles—were aimed at promoting the attitudes of typically developing peers by means of contact, information or both components. Five interventions had solely a contact component, sixteen had solely an information component and the remaining five utilized both contact and information. The outcomes concentrated on either general attitudes (k = 12) or one or more of the three attitude components: cognitive attitude (k = 14), affective attitude (k = 3), and behavioral intentions (k = 14). For a more detailed overview of the interventions, see Table 3.

Table 3. Summary of studies and interventions focusing on promoting the attitudes of typically developing peers.

A total of 67 associations1 were derived from the studies examining the immediate effect of the interventions (see Table 4). Overall, 39% of the associations indicated a significant improvement of attitude after the intervention was implemented, 1% a significant deterioration and 55% of the associations indicated non-significant results. For the remaining associations, the p-value was not reported. In more than half of the cases, the effect size was not calculable and the remainder showed a mixed picture. The majority of the effect sizes indicated some effect of the included interventions (19% small effect, 6% medium effect, and 6% large effect), but in contrast 9% of the effect sizes indicated no effect, and 4% indicated small adverse effects.

Interventions that included solely a contact component produced mainly non-significant results and no to medium effects. The associations involving solely an information component showed a mixed picture: 43% indicated positive results and 53% produced non-significant results. Effect sizes varied from small adverse to large positive effects. Interventions that utilized both contact and information produced merely positive results and small to large effects.

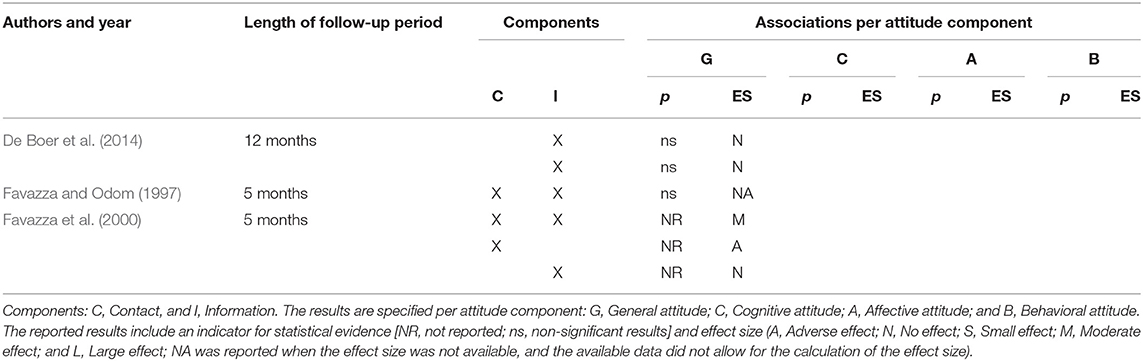

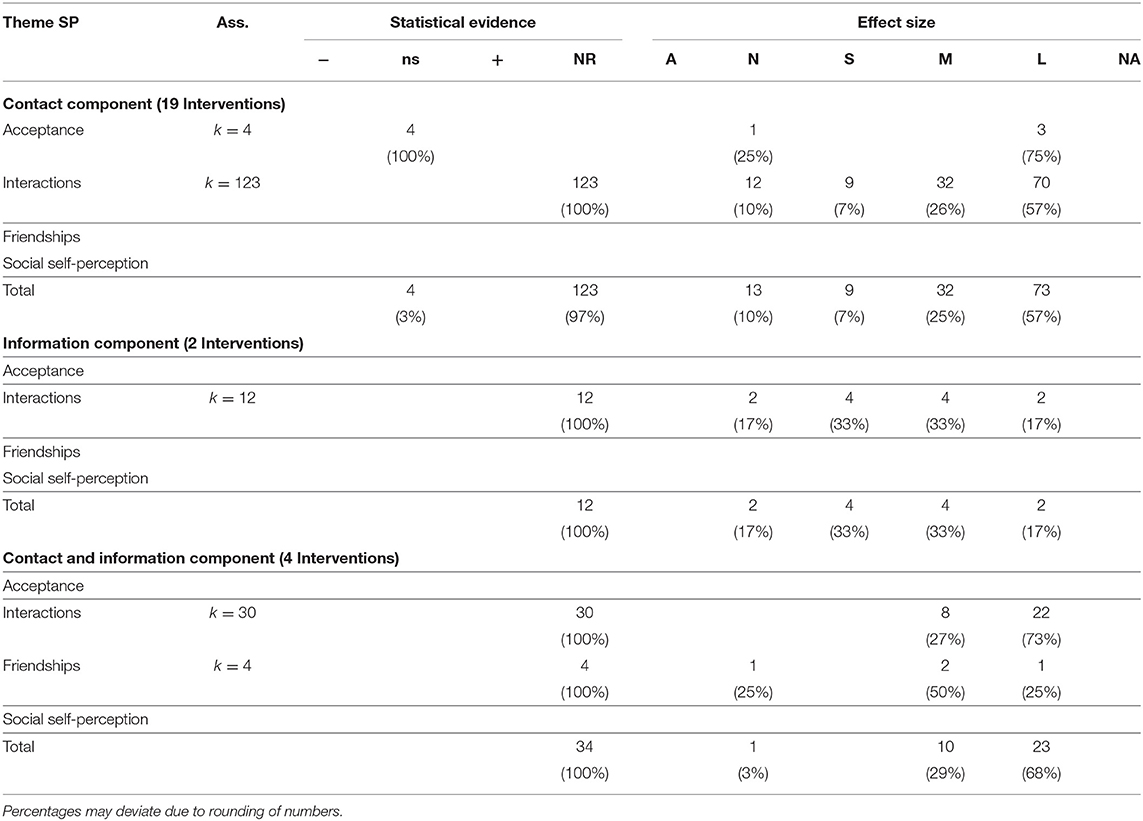

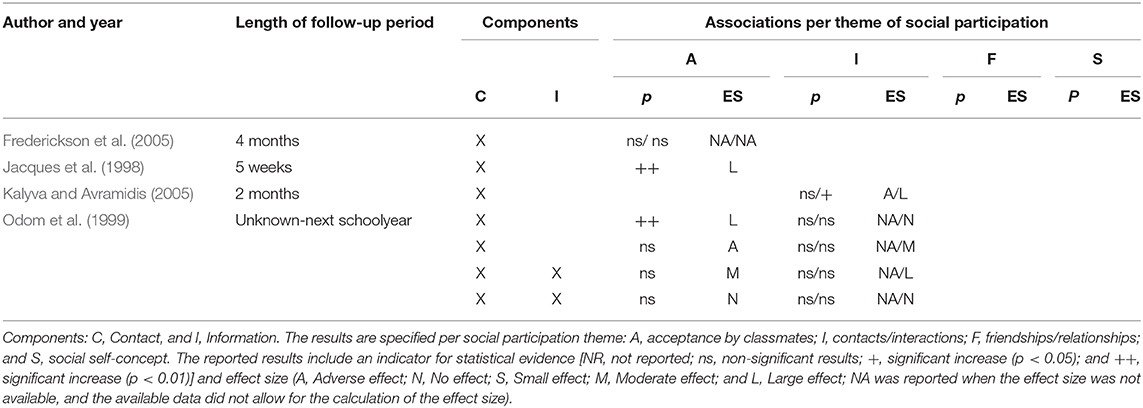

A total of six associations were derived from the studies examining the long-term effectiveness (Table 5). Only data on associations with general attitudes was available in the included articles. All available p-values indicated non-significant results. The available and calculated effect sizes showed a mixed picture: three effect sizes indicated no long-term effectiveness whereas one indicated moderate long-term effects, and another one indicated small adverse effects.

Table 5. Summary of studies examining long-term effects on the attitudes of typically developing peers.

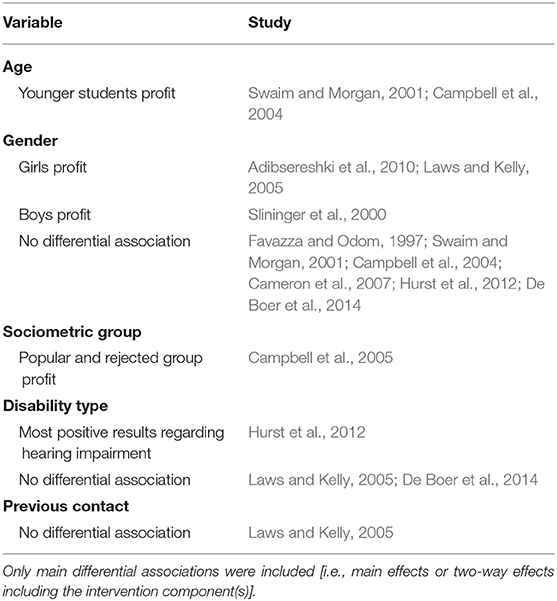

Moreover, 11 studies investigated whether the impact of contact and information on attitude differed according to background variables. The results indicate that the effect of interventions could be different according to age (k = 2), gender (k = 3), sociometric status (k = 1), and disability type (k = 1). Previous contact experiences were found not to impact the intervention effect (k = 1). However, the results regarding gender and disability type were mixed (see Table 6). With regard to gender, six studies indicated no impact by gender, two studies indicated girls benefit more from interventions utilizing solely information, and one indicated boys benefit more from interventions utilizing solely contact. With regard to disability type, two studies indicated no impact by disability type, and one indicated that best results were achieved toward hearing impairment.

Associations Between Contact and Information and Social Participation

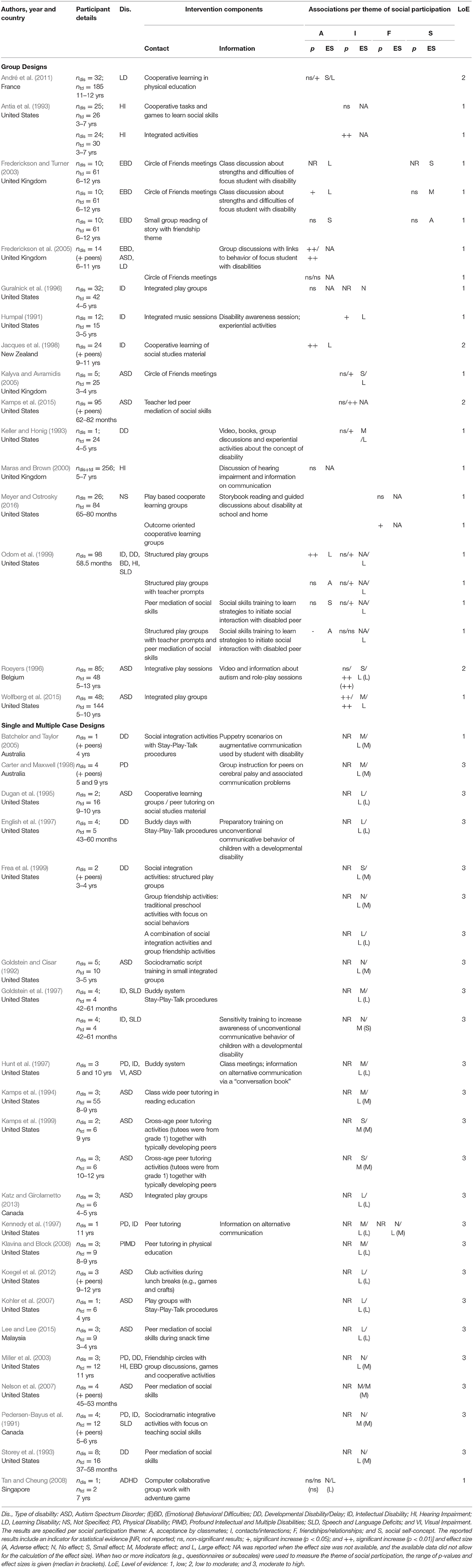

Overall, a differential relationship was found between the extent to which the variables contact with and information about (students with) disabilities are related to the social participation of students with disabilities. This relationship differed according to the utilized intervention components. In total, 48 interventions—reported in 36 articles—were aimed at promoting the social participation of students with disabilities. Of the investigated interventions, 32 had solely a contact component, five had solely an information component and the remaining 11 utilized both contact and information. The outcomes concentrated on one or more of the four themes of social participations: acceptance by classmates (k = 13), contact/interactions (k = 37), friendships/relationships (k = 3), and social self-perception (k = 3). For a more detailed overview of the interventions we refer the interested reader to consult (Table 7).

Table 7. Summary of studies and interventions focusing on promoting the social participation of students with a disability.

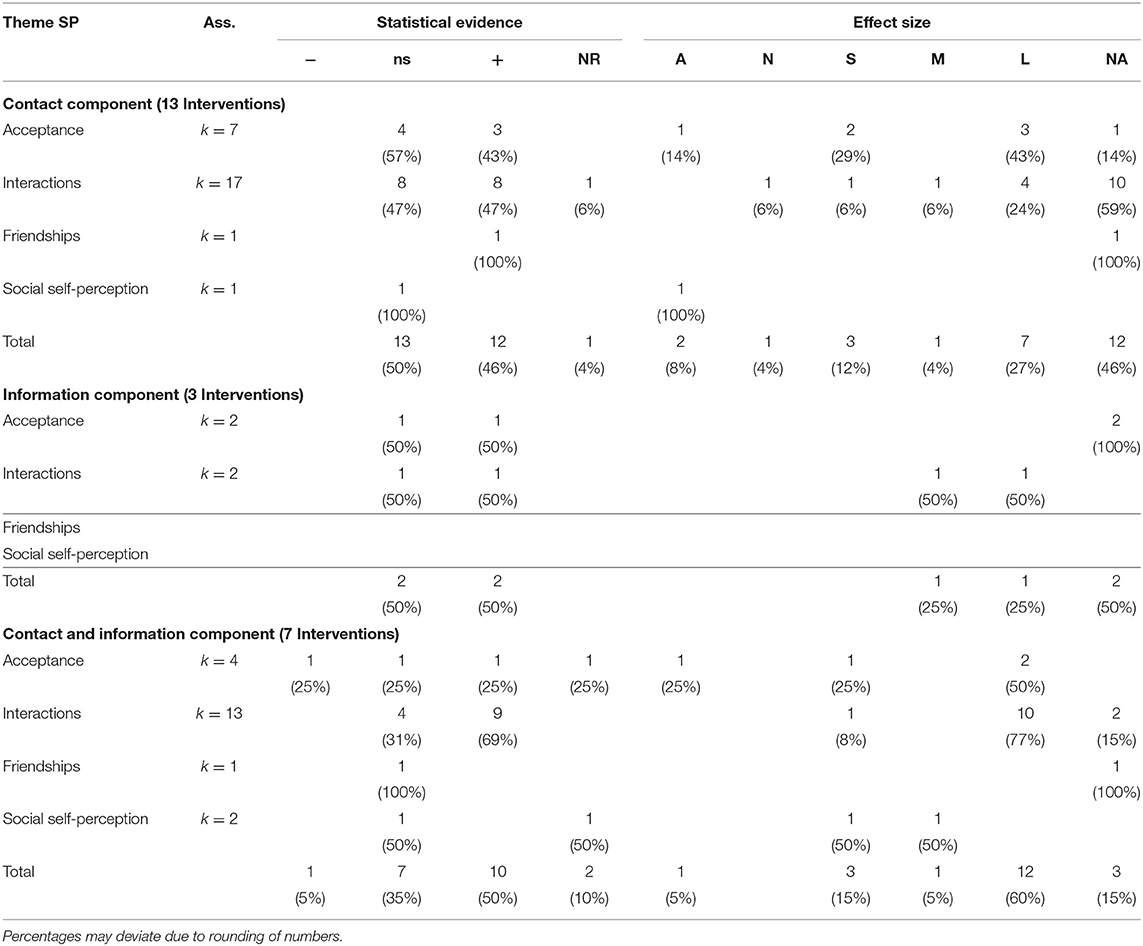

A total of 223 associations were derived from the studies examining the immediate effect of an intervention on one or more aspects of social participation studies (see Table 8). A distinction is made between group design studies (50 associations) and single or multiple case studies (173 associations). From the group design studies, overall, 48% of the associations indicated a significant improvement of social participation, 2% a significant deterioration, and 44% of the associations indicated non-significant results. The majority of the available and calculated effect sizes indicated clear effects of the included interventions (10% small effect, 6% medium effect and 40% large effect), but in contrast 6% of the effect sizes indicated small adverse effects. From the single and multiple case design studies, the great majority of the available effect sizes indicated clear effects of the included interventions (8% small effect, 27% medium effect, and 57% large effect). Only 9% of the studies indicated no effects.

Table 8A. Number of associations by intervention component and by social participation theme from group design studies.

Table 8B. Number of associations by intervention component and by social participation theme from single/multiple case design studies.

The statistical evidence derived from group design studies for interventions that included solely a contact component, solely an information component, or both components, showed a mixed picture: about half indicated positive results and the other half non-significant results. Looking at the effect sizes, however, differences were found. For interventions that used solely contact or both contact and information, the majority of associations had a large effect size, even though effects varied from small adverse to large effects. Effect sizes varied from medium to large effects for interventions with solely an information component. Nonetheless, effect sizes were not calculable in about half of the group design studies. The effect sizes that could be derived from single and multiple case studies indicated mainly large effects for interventions with a contact component (both exclusive as well as combined with information), but almost an even spread between no, small, medium and large effect for interventions with only an information component.

A total of 17 associations were derived from the studies examining the long-term effectiveness (Table 9). The outcomes focused on acceptance by classmates (seven associations) and contact/interactions (10 associations). The long-term effectiveness on friendships/relationships and social self-perception was not investigated in any of the included articles. Overall, 82% of the associations indicated non-significant results and 18% of the associations still indicated a significant improvement of social participation. The majority of the available and calculated effect sizes indicated clear long-term effects (20% medium effect and 40% large effect), but in contrast 30% of the effect sizes indicated no long-term effectiveness, and 10% indicated even small adverse effects.

Table 9. Summary of studies examining long-term effects on the social participation of students with disabilities.

No studies investigated whether the impact of contact and information on social participation differed according to background variables.

The Mediating Role of Peers' Attitudes

No studies were found that investigated the mediating role of peers' attitudes in the relationship between contact/information and the social participation of students with disabilities.

Discussion

Conclusions

Considering the global trend toward inclusive education, and that the social participation of students with disabilities is lagging behind, it is important to know how this can be improved. This study was set up to elucidate whether or not the Contact Theory can be applied in inclusive education by serving as a theoretical framework in promoting the social participation of students with disabilities. The proposed conceptual model was tested via a systematic review study to analyze if contact with and information about (people with) disabilities can promote the social participation of students with disabilities in regular education in a direct and/or mediated way via peers' attitudes. First, it can be concluded that that interventions utilizing solely contact generally do not promote peers' attitudes. Interventions utilizing solely information perform slightly better, but the best results are achieved when contact and information are combined. Second, it can be concluded that the outcomes of interventions utilizing solely contact or solely information on the social participation of students with disabilities are similar. Yet, the evidence base for the contact interventions is larger (i.e., more studies investigated this). Again, it can be concluded that interventions that combined contact and information achieved the best results. Third, we conclude that there are no studies examining the mediating effect of attitudes between contact and information and the social participation of students with disabilities. We therefore cannot answer the question whether this mediating effect holds or not.

Discussion

Rather than being a quick fix, interventions ideally establish solid and long-term improvements. Nevertheless, the endurance of the intervention effects was not often investigated. This study showed that long-term effects were only investigated in about 20% of the interventions, and while the effects in some studies lasted up to 2 months (Jacques et al., 1998; Kalyva and Avramidis, 2005), nearly all studies indicated that the positive impact of the intervention did not sustain with regard to both peer attitudes (Favazza and Odom, 1997; Favazza et al., 2000; De Boer et al., 2014) and the social participation of students with disabilities (Odom et al., 1999; Frederickson et al., 2005). This might be because both the formation of attitudes and the social participation can also be impacted by factors outside of the intervention. Although interventions aim to provide only positive contact and information, they cannot avert all unintended negative contact and information that can be present alongside or after the intervention (e.g., quarrels with somebody with a disability). This is detrimental because negative experiences are known to have a bigger impact on attitudes and social participation than do positive experiences (Barlow et al., 2012); many more positive experiences are needed to establish improvement, than negative experiences are needed to deterioration. To establish long-term and solid improvements, interventions that can be implemented over a long period, or even become part of the curriculum permanently are advised.

Furthermore, it can be questioned to what extent the findings of this review can be generalized, since not all types of disabilities have been equally studied. In line with previous findings (e.g., Garrote et al., 2017), most studies have focused on autism spectrum disorder, whereas other types of disabilities, such as sensory impairments, have been investigated to a lesser extent. This unbalanced representation of disabilities is especially evident in studies focusing on promoting social participation. Since it is known from the literature that some types of disabilities are more prone to both negative peer attitudes and difficulties regarding social participation (see Van Mieghem et al., 2018), it is unrealistic to generalize the results to the whole group of students with disabilities. More research is needed, particularly into attitudes toward and the social participation of students with sensory impairments, as well as comparisons between disability types, to be able to draw a complete picture of the effects of contact and information.

Promoting Attitudes

Different types of contact and information were utilized to promote peer attitudes, and it can be concluded that not all types were equally effective. Most positive associations between contact and attitudes were found in interventions using integrated activities and playgroups. Also introducing somebody with a disability as the co-presenter of the intervention was associated with small positive effects. Both cooperative learning/play groups and peer assistance were not associated with improved attitudes. Regarding the information component, the picture is somewhat mixed. The most important source of information appeared to be guided group discussions, as they were associated with more positive attitudes than interventions that did not include discussions. In addition, storybooks about disabilities and experiential learning (e.g., disability simulation) were positively associated with peer attitudes. For videos the results were mixed, probably due to differences in content (cf. De Boer et al., 2012; Leigers and Myers, 2015). Based on these results, it seems that integrated activities, story books and experiential learning are good ingredients when aiming to promote more positive attitudes. Furthermore, including guided group discussions is recommended to assure that the information comes across to students in the way it was intended.

The findings of the current study do not align fully with the Contact Theory. Allport proposed conditions for optimal contact: equal status, common goals, intergroup cooperation, and support of authorities (Allport, 1954; Dovidio et al., 2003; Schofield et al., 2003) and numerous studies have indicated that the beneficial effect of contact was greater when Allport's criteria were met (Brown and Hewstone, 2005; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2005, 2006). Nevertheless, in the current review, cooperative learning was not associated with positive peer attitudes. This is a counterintuitive finding, as cooperative learning is in essence ideally suited to meet the four proposed conditions. Regular integrated activities and play groups, however, were associated with positive attitudes, despite the absence of arranged cooperation. It might be that additional criteria for optimal contact are needed in performance-oriented contexts like schools where disabilities may become more apparent to certain subjects (e.g., math or competitive sports) (Odom et al., 2006). Contact forms that were associated with more positive attitudes were all more social and fun in nature (e.g., playing games). Therefore, we would like to add fun as an important condition, as it can serve as an equalizer that points out similarities between students, regardless of different abilities (Siperstein et al., 2009).

Furthermore, affective aspects have been mostly ignored in the included studies. This is remarkable since research has shown that affective processes are more predictive of actual intergroup behavior than are cognitive processes (for an overview see Brown and Hewstone, 2005). None of the included studies addressed the underlying affective mechanisms that mediate the contact-attitude relationship (i.e., intergroup anxiety and empathy: Brown and Hewstone, 2005; Aberson and Haag, 2007; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2008). While the mediating role of intergroup anxiety and empathy has also been confirmed for students' contact and attitudes toward peers with a disability in a natural context (Armstrong et al., 2016), it remains unknown whether these mediating effects also hold in interventions that aim to promote students' attitudes toward peers with a disability, utilizing contact and information. Considering the affective mediators can transfer both positive and negative affect to the attitude object (Clore and Schnall, 2005), most effect of contact would be expected in the affective component of attitude. Though, surprisingly, little attention has been given to the affective component of attitude in the included studies. Both cognitive attitude and behavioral attitude, as well as general attitudes were investigated much more often than was affective attitude. Evidently, there is a need for studies investigating intervention effects on all three components of attitudes, while also addressing the mediating affective processes, and preferably linking to social participation as well.

Promoting Social Participation

Different types of contact were utilized to promote the social participation of students with disabilities, such as cooperative learning, peer support groups (e.g., friendship circles), integrated activities and peer mediation or peer tutoring, buddy systems. All contact types were equally able to promote social participation, with the exception of sociodramatic script training. However, while contact was positively associated with interactions, the associations with acceptance, friendship and social self-perception were miscellaneous and sometimes even negative. Similarly, the provided information, which mainly focused on alternative ways of communicating with a (specific) student with a disability, was also positively related to interactions but not with acceptance and self-perception.

Although interactions are one of the four themes in the definition of social participation as described by Koster et al. (2009), they are very different in nature from the other themes. Interactions are short-term processes, which may or may not lead to the long-term emergence of the more complex themes of social participation, namely acceptance, friendships and the social self-perception of a student (Van Geert and Steenbeek, 2005; Fabes et al., 2009); in other words, interactions can be considered as the building blocks for the other themes. Given the relatively short length of most interventions it seems only logical that the most positive results were established within the interactions theme of social participation. However, we have real concerns about the predictive validity of interactions, considering how they were commonly operationalized. The majority of studies in our review focused on the more mechanical aspects of interactions, such as frequency, duration, initiations and responses, whereas other aspects of interactions are more indicative for establishing acceptance and friendships (e.g., reciprocity, intimacy, emotional expression) (e.g., Van Geert and Steenbeek, 2005; Bukowski et al., 2009). There is still a lack of research investigating the pathways from interactions to acceptance and friendships and subsequently the social self-perception of students with disabilities.

Whereas, social acceptance and friendship are voluntary in character and cannot be enforced (Howe and Leach, 2018), interactions can also be involuntary. Many interventions enforced interactions by utilizing extrinsic motivation, such as praises or rewards, to initiate and pursue social interaction with a peer with a disability (e.g., English et al., 1997; Goldstein et al., 1997; Kohler et al., 2007; Lee and Lee, 2015). While these methods produce immediate effects, they will also erode the intrinsic motivation of students to communicate with their peers with disabilities and will probably result in less interaction after de extrinsic motivation is taken away. Stimulating contact by making use of students' intrinsic motivation to interact will result is more permanent effects. Moreover, in several interventions typically developing students were prompted by teachers or assistants when no interaction took place for a predefined amount of time (e.g., Goldstein and Cisar, 1992; Antia et al., 1993; Storey et al., 1993; Frea et al., 1999; Odom et al., 1999; Nelson et al., 2007; Kamps et al., 2015; Lee and Lee, 2015). This might be a good way to start up interactions between students with and without disabilities, however, since the interaction data were often collected during intervention sessions, the positive results are most likely an overestimation of the real voluntary social interactions that took place in day to day classroom activities outside of the intervention (e.g., at the playground). When operationalizing the themes of social participation, one should keep in mind the voluntary character of its themes.

The Mediating Role of Peer Attitudes

Surprisingly, not any studies were found investigating the mediating role of peer attitudes. Many authors have suggested that negative peer attitudes are the main barrier for the social participation of students with disabilities, and, moreover, several empirical studies confirmed this relationship. Nevertheless, evidence for this mediating role of attitudes in interventions is lacking. Since attitudes and behavior are related to each other in a complex way (Ajzen and Fishbein, 2005), it remains unknown whether the social participation of students with disabilities can be enhanced via the promotion of the attitudes of their typically developing peers. Educational professionals therefore best pick interventions that include both contact and information, to strive for the best outcomes for students with and without disabilities.

Reflection on the Conceptual Model

Based on the Contact Theory, this review proposed a conceptual model (Figure 1) for promoting the social participation of students with disabilities, through direct contact and information, via peers' attitudes. Evidently, the reality is far more complex than was proposed in this model. Several theoretical frameworks provide insight into the complexity of behavior change, such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior is an effective framework for predicting and explaining behavior (Armitage and Conner, 2001), also in the field of inclusive education (e.g., Obrusnikova et al., 2011; MacFarlane and Woolfson, 2013). According to the Theory of Planned Behavior, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control also play an important role in predicting both behavioral intentions and actual behavior (see also Ajzen et al., 2019). Furthermore, the later modifications of the Contact Theory (Brown and Hewstone, 2005) nuance the impact of contact and information by acknowledging the role of underlying cognitive and affective processes. Lastly, several background factors also play a role in attitude development, such as gender (Nowicki and Sandieson, 2002; Barr and Bracchitta, 2012), personality (Sibley and Duckitt, 2008; Akrami et al., 2011; Page and Islam, 2015), culture (Sheridan and Scior, 2013; Benomir et al., 2016), knowledge about disabilities (Vignes et al., 2009; De Boer et al., 2012), and (in)direct experiences with disabilities (McManus et al., 2011; Keith et al., 2015). Rather than presenting a comprehensive model, we aimed to present a model to guide interventions aimed at promoting the social participation of students with disabilities. Therefore, a focus on malleable factors was needed. Although, it can be argued that the focus on solely contact, information, and peer attitudes is too simplistic, they are, however, malleable factors that can easily be manipulated through interventions.

Limitations

This review focused solely on the relationship between contact and information on the one hand and attitudes and social participation on the other hand. As a consequence, only the content and format of the interventions was investigated, and other factors that might have impacted the results were left out of the investigation, such as program duration, frequency and intensity (Leigers and Myers, 2015), the implementation agent (Flay et al., 2005), or the fidelity of implementation (see Carroll et al., 2007). Therefore, it is not possible to ascertain that the effects we derived from the studies were not affected by such factors. Second, in this review all data covering the relationship between contact and information and attitudes and social participation were considered as separate associations. This could have instigated an unbalanced representation of the data as the separate associations might not have been unique associations because of overlap due to multicollinearity or due to a lack of correction for disattenuation. Third, due to vague, brief and rather incomplete descriptions of the interventions, we were occasionally unable to judge whether contact and/or information were part of the interventions. Therefore, we had to exclude several, possibly relevant, studies.

Can the Contact Theory Be Applied in the Context of Inclusive Education?

Allport (1954) was convinced that both contact opportunities and information were needed to achieve attitude change and thereby intergroup social relations. As hypothesized, this review concludes that interventions combining contact and information can promote peer attitudes as well as the social participation of students with disabilities. These findings demonstrate the applicability for the Contact Theory in primary inclusive education, especially concerning the promotion of typically developing peers' attitudes. With regard to the promotion of social participation, it appears that the Contact Theory can only be partially validated, as the evidence is currently limited to its interaction theme only. Further research is needed that investigates its applicability pertaining to social acceptance, friendships and social self-perception of students with disabilities.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

FR conducted the literature search, extracted the data, and developed the first draft of the manuscript. The selection procedure was led by FR. EK assisted this process by reviewing a random sample of the record to establish the interrater reliability and discrepancies were discussed with AdB and AM. AdB, EK, and AM provided critical feedback on the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. ^In several studies, more than one indicator was used to measure the outcome variable. Therefore, the total number of associations deviates from the number of investigated interventions and the aggregated numbers of investigated outcome variables.

References

Aberson, C. L. (2015). Positive intergroup contact, negative intergroup contact, and threat as predictors of cognitive and affective dimensions of prejudice. Group Proces. Intergr. Relat. 18, 743–760. doi: 10.1177/1368430214556699

Aberson, C. L., and Haag, S. C. (2007). Contact, perspective taking, and anxiety as predictors of stereotype endorsement, explicit attitudes, and implicit attitudes. Group Proces. Intergr. Relat. 10, 179–201. doi: 10.1177/1368430207074726

*Adibsereshki, N., Tajrishi, M. P., and Mirzamani, M. (2010). The effectiveness of a preparatory students programme on promoting peer acceptance of students with physical disabilities in inclusive schools of Tehran. Educ. Stud. 36, 447–459. doi: 10.1080/03055690903425334

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Org. Behav. Hum. Decision Proces. 50, 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ajzen, I., and Fishbein, M. (2005). “The influence of attitudes on behavior,” in The Handbook of Attitudes, eds D. Albarracín, B. T. Johnson, and M. P. Zanna (New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 173–221.

Ajzen, I., Fishbein, M., Lohmann, S., and Albarracín, D. (2019). “The influence of attitudes on behavior,” in The Handbook of Attitudes Volume 1: Basic Principles. 2nd ed. eds D. Albacarrín and B. T. Johnson (New York, NY: Routledge), 197–255.

Akrami, N., Ekehammar, B., and Bergh, R. (2011). Generalized prejudice: common and specific components. Psychol. Sci. 22, 57–59. doi: 10.1177/0956797610390384

*André, A., Deneuve, P., and Louvet, B. (2011). Cooperative learning in physical education and acceptance of students with learning disabilities. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 23, 474–485. doi: 10.1080/10413200.2011.580826

*Antia, S. D., Kreimeyer, K. H., and Eldredge, N. (1993). Promoting social interaction between young children with hearing impairments and their peers. Except. Child. 60, 262–275. doi: 10.1177/001440299406000307

Armitage, C. J., and Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 40, 471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939

Armstrong, M., Morris, C., Abraham, C., and Tarrant, M. (2017). Interventions utilising contact with people with disabilities to improve children's attitudes towards disability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Disabil. Health J. 10, 11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.10.003

Armstrong, M., Morris, C., Abraham, C., Ukoumunne, O. C., and Tarrant, M. (2016). Children's contact with people with disabilities and their attitudes towards disability: a cross-sectional study. Disabil. Rehabil. 38, 879–888. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2015.1074727

Avramidis, E., Avgeri, G., and Strogilos, V. (2018). Social participation and friendship quality of students with special educational needs in regular Greek primary schools. Eur. J. Special Needs Edu. 33, 221–234. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2018.1424779

Barlow, F. K., Paolini, S., Pedersen, A., Hornsey, M. J., Radke, H. R. M., Harwood, J., et al. (2012). The contact caveat: negative contact predicts increased prejudice more than positive contact predicts reduced prejudice. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 38, 1629–1643. doi: 10.1177/0146167212457953

Barr, J. J., and Bracchitta, K. (2012). Attitudes toward individuals with disabilities: the effects of age, gender, and relationship. J. Relationships Res. 3, 10–17. doi: 10.1017/jrr.2012.1

*Batchelor, D., and Taylor, H. (2005). Social inclusion—the next step: user-friendly strategies to promote social interaction and peer acceptance of children with disabilities. Aust. J. Early Childh. 30, 10–18. doi: 10.1177/183693910503000403

Bates, H., McCafferty, A., Quayle, E., and McKenzie, K. (2015). Review: typically-developing students' views and experiences of inclusive education. Disabil. Rehabil. 37, 1929–1939. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.993433

Bedell, G. M., and Dumas, H. M. (2004). Social participation of children and youth with acquired brain injuries discharged from inpatient rehabilitation: a follow-up study. Brain Injury 18, 65–82. doi: 10.1080/0269905031000110517

Benomir, A. M., Nicolson, R. I., and Beail, N. (2016). Attitudes towards people with intellectual disability in the UK and Libya: a cross-cultural comparison. Res. Dev. Disabil. 51–52, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.12.009

Bigler, R. S., and Liben, L. S. (2006). A developmental intergroup theory of social stereotypes and prejudice. Adv. Child Dev. Behav. 34, 39–89. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2407(06)80004-2

Bossaert, G., Colpin, H., Pijl, S. J., and Petry, K. (2011). The attitudes of Belgian adolescents towards peers with disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 32, 504–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.12.033

Bossaert, G., and Petry, K. (2013). Factorial validity of the Chedoke-McMaster Attitudes towards Children with Handicaps Scale (CATCH). Res. Dev. Disabil. 34, 1336–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.01.007

Brown, R., and Hewstone, M. (2005). “An integrative theory of intergroup contact,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 37, eds M. P. Zanna (San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press), 255–343. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(05)37005-5

Bukowski, W. M., Motzoi, C., and Meyer, F. (2009). “Friendship as process, function, and outcome,” in Handbook of Peer Interactions, Relationships, and Groups, eds K. H. Rubin, W. M. Bukowski, and B. Laursen (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 217–231.

Bukowski, W. M., and Raufelder, D. (2018). “Peers and the self,” in Handbook of Peer Interactions, Relationships, and Groups. 2nd ed, eds W. M. Bukowski, B. Laursen, and K. H. Rubin (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 141–156.

Cambra, C., and Silvestre, N. (2003). Students with special educational needs in the inclusive classroom: social integration and self-concept. Eur. J. Special Needs Educ. 18, 197–208. doi: 10.1080/0885625032000078989

*Cameron, L., and Rutland, A. (2006). Extended contact through story reading in school: reducing children's prejudice toward the disabled. J. Soc. Issues 62, 469–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2006.00469.x

*Cameron, L., Rutland, A., and Brown, R. (2007). Promoting children's positive intergroup attitudes towards stigmatized groups: extended contact and multiple classification skills training. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 31, 454–466. doi: 10.1177/0165025407081474

*Campbell, J. M., Ferguson, J. E., Herzinger, C. V., Jackson, J. N., and Marino, C. (2005). Peers' attitudes toward autism differ across sociometric groups: an exploratory investigation. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 17, 281–298. doi: 10.1007/s10882-005-4386-8

*Campbell, J. M., Ferguson, J. E., Herzinger, C. V., Jackson, J. N., and Marino, C. A. (2004). Combined descriptive and explanatory information improves peers' perceptions of autism. Res. Dev. Disabil. 25, 321–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2004.01.005

Carroll, C., Patterson, M., Wood, S., Booth, A., Rick, J., and Balain, S. (2007). A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement. Sci. 2, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-2-40

Carter, E. W., and Hughes, C. (2007). “Social interaction interventions: promoting socially supportive environments and teaching new skills,” in Handbook of Developmental Disabilities, eds S. L. Odom, R. H. Horner, M. E. Snell, and J. Blacher (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 310–329.

*Carter, M., and Maxwell, K. (1998). Promoting interaction with children using augmentative communication through a peer-directed intervention. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 45, 75–96. doi: 10.1080/1034912980450106

Chung, Y.-C., Carter, E. W., and Sisco, L. G. (2012). Social interactions of students with disabilities who use augmentative and alternative communication in inclusive classrooms. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 117, 349–367. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-117.5.349

Clore, G. L., and Schnall, S. (2005). “The influence of affect on attitude,” in Handbook of Attitudes, eds D. Albarracín, B. T. Johnson, and M. P. Zanna (New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 437–489.

Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 1, 98–101. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10768783

De Boer, A., Pijl, S. J., and Minnaert, A. (2012). Students' attitudes towards peers with disabilities: a review of the literature. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 59, 379–392. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2012.723944

*De Boer, A., Pijl, S. J., Minnaert, A., and Post, W. (2014). Evaluating the effectiveness of an intervention program to influence attitudes of students towards peers with disabilities. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 44, 572–583. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1908-6

De Boer, A., Pijl, S. J., Post, W., and Minnaert, A. (2013). Peer acceptance and friendships of students with disabilities in general education: the role of child, peer, and classroom variables. Soc. Dev. 22, 831–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00670.x

Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., and Kawakami, K. (2003). Intergroup contact: the past, present, and the future. Group Proces. Intergr. Relat. 6, 5–20. doi: 10.1177/1368430203006001009

*Dugan, E., Kamps, D., and Leonard, B. (1995). Effects of cooperative learning groups during social studies for students with autism and fourth-grade peers. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 28, 175–188. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-175

Dunst, C. J., Snyder, S. W., and Mankinen, M. (1989). “Efficacy of early intervention,” in Handbook of Special Education, eds M. C. Wang, M. C. Reynolds, and H. J. Walber (Oxford; New York, NY: Pergamon Press), 259–294.

Dyson, L. L. (2005). Kindergarten children's understanding of and attitudes toward people with disabilities. Top. Early Childhood Special Educ. 25, 95–105. doi: 10.1177/02711214050250020601

Eagly, A. H., and Chaiken, S. (1993). The Psychology of Attitudes. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.

*English, K., Goldstein, H., Shafer, K., and Kaczmarek, L. (1997). Promoting interactions among preschoolers with and without disabilities: effects of a buddy skills- training program. Except. Child. 63, 229–243. doi: 10.1177/001440299706300206

Fabes, R. A., Martin, C. L., and Hanish, L. D. (2009). “Children's behaviors and interactions with peers,” in Handbook of Peer Interactions, Relationships, and Groups, eds K. H. Rubin, W. M. Bukowski, and B. Laursen (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 45–62).

*Favazza, P. C., and Odom, S. L. (1997). Promoting positive attitudes of kindergarten-age children toward people with disabilities. Except. Children 63, 405–418. doi: 10.1177/001440299706300308

Favazza, P. C., Ostrosky, M., and Mouzourou, C. (2016). The Making Friends Program: Supporting Acceptance in Your K-2 Classroom. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

*Favazza, P. C., Phillipsen, L., and Kumar, P. (2000). Measuring and promoting acceptance of young children with disabilities. Except. Children 66, 491–508. doi: 10.1177/001440290006600404

Fishbein, M., and Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Flay, B. R., Biglan, A., Boruch, R. F., Castro, F. G., Gottfredson, D., Kellam, S., et al. (2005). Standards of evidence: criteria for efficacy, effectiveness and dissemination. Prev. Sci. 6, 151–175. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-5553-y

*Frea, W., Craig-Unkefer, L., Odom, S. L., and Johnson, D. (1999). Differential effects of structured social integration and group friendship activities for promoting social interaction with peers. J. Early Intervent. 22, 230–242. doi: 10.1177/105381519902200306

*Frederickson, N., and Turner, J. (2003). Utilizing the classroom peer group to address children's social needs: an evaluation of the Circle of Friends intervention approach. The Journal of Special Education, 36, 234–245. doi: 10.1177/002246690303600404

*Frederickson, N., Warren, L., and Turner, J. (2005). “Circle of Friends” —an exploration of impact over time. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 21, 197–217. doi: 10.1080/02667360500205883

Frostad, P., and Pijl, S. J. (2007). Does being friendly help in making friends? The relation between the social position and social skills of pupils with special needs in mainstream education. Eur. J. Special Needs Educ. 22, 15–30. doi: 10.1080/08856250601082224

*Gannon, S., and McGilloway, S. (2009). Children's attitudes toward their peers with Down Syndrome in schools in rural Ireland: an exploratory study. Eur. J. Special Needs Educ. 24, 455–463. doi: 10.1080/08856250903223104

Garrote, A., Dessemontet, R. S., and Opitz, E. M. (2017). Facilitating the social participation of pupils with special educational needs in mainstream schools: a review of school based interventions. Educ. Res. Rev. 20, 12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2016.11.001

Godeau, E., Vignes, C., Sentenac, M., Ehlinger, V., Navarro, F., Grandjean, H., et al. (2010). Improving attitudes towards children with disabilities in a school context: a cluster randomized intervention study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 52, 236–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03731.x

*Goldstein, H., and Cisar, C. L. (1992). Promoting interaction during sociodramatic play: teaching scripts to typical preschoolers and classmates with disabilities. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 25, 265–280. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-265

*Goldstein, H., English, K., Shafer, K., and Kaczmarek, L. (1997). Interaction among preschoolers with and without disabilities: effects of across-the-day peer intervention. J. Speech Language Hearing Res. 40, 33–48. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4001.33

*Guralnick, M. J., Connor, R. T., Hammond, M., Gottman, J. M., and Kinnish, K. (1996). Immediate effects of mainstreamed settings on the social interactions and social integration of preschool children. Am. J. Mental Retard. 100, 359–377.

Guralnick, M. J., Neville, B., Hammond, M. A., and Connor, R. T. (2007). The friendships of young children with developmental delays: a longitudinal analysis. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 28, 64–79. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.10.004

Hestenes, L. L., and Carroll, D. E. (2000). The play interactions of young children with and without disabilities: individual and environmental influences. Early Childh. Res. Quart. 15, 229–246. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(00)00052-1

Howe, N., and Leach, J. (2018). “Children's play and peer relations,” in Handbook of Peer Interactions, Relationships, and Groups. 2nd ed, eds W. M. Bukowski, B. Laursen, and K. H. Rubin (The Guilford Press), 222–242.

*Humpal, M. (1991). The effects of an integrated early childhood music program on social interaction among children with handicaps and their typical peers. J. Music Ther. 28, 161–177. doi: 10.1093/jmt/28.3.161

*Hunt, P., Farron-Davis, F., Wrenn, M., Hirose-Hatae, A., and Goetz, L. (1997). Promoting interactive partnerships in inclusive educational settings. J. Assoc. Persons Severe Handicaps 22, 127–137. doi: 10.1177/154079699702200301

*Hurst, C., Corning, K., and Ferrante, R. (2012). Children's acceptance of others with disability: the influence of a disability-simulation program. J. Genetic Counseling 21, 873–883. doi: 10.1007/s10897-012-9516-8

*Ison, N., McIntyre, S., Rothery, S., Smithers-Sheedy, H., Goldsmith, S., Parsonage, S., et al. (2010). ‘Just like you’: a disability awareness programme for children that enhanced knowledge, attitudes and acceptance: pilot study findings. Dev. Neurorehabil. 13, 360–368. doi: 10.3109/17518423.2010.496764

*Jacques, N., Wilton, K., and Townsend, M. (1998). Cooperative learning and social acceptance of children with mild intellectual disability. J. Intellectual Disability Res. 42, 29–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.1998.00098.x

*Kalyva, E., and Avramidis, E. (2005). Improving communication between children with autism and their peers through the “Circle of Friends”: a small-scale intervention study. J. Appl. Res. Intellectual Disabil. 18, 253–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2005.00232.x

*Kamps, D. M., Barbetta, P. M., Leonard, B. R., and Delquadri, J. (1994). Classwide peer tutoring: an integration strategy to improve reading skills and promote peer interactions among students with autism and general education peers. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 27, 49–61. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-49

*Kamps, D. M., Dugan, E., Potucek, J., and Collins, A. (1999). Effects of cross-age peer tutoring networks among students with autism and general education students. J. Behav. Educ. 9, 97–115. doi: 10.1023/A:1022836900290

*Kamps, D. M., Thiemann-Bourque, K., Heitzman-Powell, L., Schwartz, I., Rosenberg, N., Mason, R., et al. (2015). A comprehensive peer network intervention to improve social communication of children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized trial in kindergarten and first grade. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45, 1809–1824. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2340-2

Kasari, C., Locke, J., Gulsrud, A., and Rotheram-Fuller, E. (2011). Social networks and friendships at school: comparing children with and without ASD. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 41, 533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1076-x

*Katz, E., and Girolametto, L. (2013). Peer-mediated intervention for preschoolers with ASD implemented in early childhood education settings. Top. Early Childh. Special Educ. 33, 133–143. doi: 10.1177/0271121413484972

Keith, J. M., Bennetto, L., and Rogge, R. D. (2015). The relationship between contact and attitudes: reducing prejudice toward individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 47, 14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.07.032

*Keller, D., and Honig, A. S. (1993). Curriculum to promote positive interactions of preschoolers with a disabled peer introduced into the classroom. Early Child Dev. Care 96, 27–34. doi: 10.1080/0300443930960104

*Kennedy, C. H., Cushing, L. S., and Itkonen, T. (1997). General education participation improves the social contacts and friendship networks of students with severe disabilities. J. Behav. Educ. 7, 167–189. doi: 10.1023/A:1022888924438

Killen, M., and Rutland, A. (2011). Children and Social Exclusion: Morality, Prejudice, and Group Identity. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. doi: 10.1002/9781444396317

*Klavina, A., and Block, M. E. (2008). The effect of peer tutoring on interaction behaviors in inclusive physical education. Adapted Phys. Act. Quart. 25, 132–158. doi: 10.1123/apaq.25.2.132

*Koegel, L. K., Vernon, T. W., Koegel, R. L., Koegel, B. L., and Paullin, A. W. (2012). Improving social engagement and initiations between children with autism spectrum disorder and their peers in inclusive settings. J. Positive Behav. Intervent. 14, 220–227. doi: 10.1177/1098300712437042

*Kohler, F. W., Greteman, C., Raschke, D., and Highnam, C. (2007). Using a buddy skills package to increase the social interactions between a preschooler with autism and her peers. Top. Early Childh. Spec. Educ. 27, 155–163. doi: 10.1177/02711214070270030601

Koster, M., Nakken, H., Pijl, S. J., and Van Houten, E. (2009). Being part of the peer group: a literature study focusing on the social dimension of inclusion in education. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 13, 117–140. doi: 10.1080/13603110701284680

Koster, M., Pijl, S. J., Nakken, H., and van Houten, E. (2010). Social participation of students with special needs in regular primary education in the Netherlands. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 57, 59–75. doi: 10.1080/10349120903537905

Koster, M., Pijl, S. J., van Houten, E., and Nakken, H. (2007). The social position and development of pupils with SEN in mainstream Dutch primary schools. Eur. J. Special Needs Educ. 22, 31–46. doi: 10.1080/08856250601082265

Ladd, G. W., and Kochenderfer-Ladd, B. (2016). “Research in educational psychology: social exclusion in school,” in Social Exclusion: Psychological Approaches to Understanding and Reducing Its Impact, eds P. Riva and J. Eck (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 109–132. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-33033-4_6

*Law, Y., Lam, S., Law, W., and Tam, Z. W. Y. (2017). Enhancing peer acceptance of children with learning difficulties: classroom goal orientation and effects of a storytelling programme with drama techniques. Educ. Psychol. 37, 537–549. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2016.1214685

*Laws, G., and Kelly, E. (2005). The attitudes and friendship intentions of children in United Kingdom mainstream schools towards peers with physical or intellectual disabilities. Int. J. Disabil. Dev Educ. 52, 79–99. doi: 10.1080/10349120500086298

*Lee, S. H., and Lee, L. W. (2015). Promoting snack time interactions of children with autism in a Malaysian preschool. Top. Early Childh. Special Educ. 35, 89–101. doi: 10.1177/0271121415575272

Leigers, K. L., and Myers, C. T. (2015). Effect of duration of peer awareness education on attitudes toward students with disabilities: a systematic review. J. Occup. Ther. School. Early Intervent. 8, 79–96. doi: 10.1080/19411243.2015.1021067

Lenhard, W., and Lenhard, A. (2016). Calculation of Effect Sizes. Psychometrica. Available oniline at: https://www.psychometrica.de/effect_size.html (accessed October 9, 2020).

Lindsay, S., and Edwards, A. (2013). A systematic review of disability awareness interventions for children and youth. Disabil. Rehabil. 35, 623–646. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.702850

MacFarlane, K., and Woolfson, L. M. (2013). Teacher attitudes and behavior toward the inclusion of children with social, emotional and behavioral difficulties in mainstream schools: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Teaching Teacher Educ. 29, 46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2012.08.006

MacMillan, M., Tarrant, M., Abraham, C., and Morris, C. (2014). The association between children's contact with people with disabilities and their attitudes towards disability: a systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 56, 529–546. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12326

*Maras, P., and Brown, R. (1996). Effects of contact on children's attitudes toward disability: a longitudinal study. J. Appl. Social Psychol. 26, 2113–2134. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1996.tb01790.x

*Maras, P., and Brown, R. (2000). Effects of different forms of school contact on children's attitudes toward disabled and non-disabled peers. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 70, 337–351. doi: 10.1348/000709900158164

Margalit, M. (2004). “Loneliness and developmental disabilities: cognitive and affective processing perspectives,” in Personality Motivat. Syst. Mental Retard. vol. 28. eds H. N. Switzky (Academic Press), 225–233. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7750(04)28007-7

*Marom, M., Cohen, D., and Naon, D. (2007). Changing disability-related attitudes and self-efficacy of Israeli children via the Partners to Inclusion Programme. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 54, 113–127. doi: 10.1080/10349120601149821

*McKay, C., Block, M., and Park, J. Y. (2015). The impact of paralympic school day on student attitudes toward inclusion in physical education. Adapted Phys. Act. Quarter. 32, 331–348. doi: 10.1123/APAQ.2015-0045

McManus, J. L., Feyes, K. J., and Saucier, D. A. (2011). Contact and knowledge as predictors of attitudes toward individuals with intellectual disabilities. J. Social Personal Relationships 28, 579–590. doi: 10.1177/0265407510385494

*Meyer, L. E., and Ostrosky, M. M. (2016). Impact of an affective intervention on the friendships of kindergarteners with disabilities. Top. Early Childhood Special Educ. 35, 200–210. doi: 10.1177/0271121415571419

*Miller, M. C., Cooke, N. L., Test, D. W., and White, R. (2003). Effects of friendship circles on the social interactions of elementary age students with mild disabilities. J. Behav. Educ. 12, 167–184. doi: 10.1023/A:1025556226951

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

*Nelson, C., McDonnell, A. P., Johnston, S. S., Crompton, A., and Nelson, A. R. (2007). Keys to Play: a strategy to increase the social interactions of young children with autism and their typically developing peers. Educ. Train. Dev. Disabil. 42, 165–181. Available online at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.459.6223&rep=rep1&type=pdf#page=53

Nepi, L. D., Fioravanti, J., Nannini, P., and Peru, A. (2015). Social acceptance and the choosing of favourite classmates: a comparison between students with special educational needs and typically developing students in a context of full inclusion. Br. J. Special Educ. 42, 319–337. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12096

Nowicki, E. A. (2006). A cross-sectional multivariate analysis of children's attitudes towards disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 50, 335–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00781.x

Nowicki, E. A., and Sandieson, R. (2002). A meta-analysis of school-age children's attitudes towards persons with physical or intellectual disabilities. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 49, 243–265. doi: 10.1080/1034912022000007270

Obrusnikova, I., Dillon, S. R., and Block, M. E. (2011). Middle school student sntentions to play with peers with disabilities in physical education: using the theory of planned behavior. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 23, 113–127. doi: 10.1007/s10882-010-9210-4

*Odom, S. L., McConnell, S. R., McEvoy, M. A., Peterson, C., Ostrosky, M., Chandler, L. K., et al. (1999). Relative effects of interventions supporting the social competence of young children with disabilities. Top. Early Childh. Special Educ. 19, 75–91. doi: 10.1177/027112149901900202

Odom, S. L., Zercher, C., Li, S., Marquart, J. M., Sandall, S., and Brown, W. H. (2006). Social acceptance and rejection of preschool children with disabilities: a mixed-method analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 98, 807–823. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.98.4.807

Page, S. L., and Islam, M. R. (2015). The role of personality variables in predicting attitudes toward people with intellectual disability: an Australian perspective. J. Intellectual Disabil. Res. 59, 741–745. doi: 10.1111/jir.12180

Parker, R. I., and Vannest, K. (2009). An improved effect size for single-case research: Nonoverlap of all pairs. Behav. Ther. 40, 357–367. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2008.10.006

Parker, R. I., Vannest, K. J., and Davis, J. L. (2011). Effect size in single-case research: a review of nine nonoverlap techniques. Behav. Modification 35, 303–322. doi: 10.1177/0145445511399147

Pavri, S., and Monda-Amaya, L. (2000). Loneliness and students with learning disabilities in inclusive classrooms: self-perceptions, coping strategies, and preferred interventions. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 15, 22–33. doi: 10.1207/SLDRP1501_3

*Pedersen-Bayus, K., McDonald, L., Kysela, G., and Tanchak, D. (1991). Increasing social integration in mainstreamed kindergartens. Early Child Dev. Care 77, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/0300443910770101

Pepler, D. J., and Bierman, K. L. (2018). With a little help from my friends: The importance of peer relationships for social-emotional development. Pensylvania, PA: The Pennsylvania State University.

Pettigrew, T. F., and Tropp, L. R. (2005). “Allport's intergroup contact hypothesis: its history and influence,” in On the Nature of Prejudice: Fifty Years After Allport, eds J. F. Dovidio, P. Glick, and L. A. Rudman (Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd), 262–277.

Pettigrew, T. F., and Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 90, 751–783. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751

Pettigrew, T. F., and Tropp, L. R. (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. Eur. J. Social Psychol. 38, 922–934. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.504

Pijl, S. J., Frostad, P., and Flem, A. (2008). The social position of pupils with special needs in regular schools. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 52, 387–405. doi: 10.1080/00313830802184558

Raabe, T., and Beelmann, A. (2011). Development of ethnic, racial, and national prejudice in childhood and adolescence: a multinational meta-analysis of age differences. Child Dev. 82, 1715–1737. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01668.x

*Roeyers, H. (1996). The influence of nonhandicapped peers on the social interactions of children with a pervasive development disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 26, 303–320. doi: 10.1007/BF02172476

Rose, C. A., Monda-Amaya, L., and Espelage, D. L. (2011). Bullying perpetration and victimization in special education: a review of the literature. Remedial Special Educ. 32, 114–130. doi: 10.1177/0741932510361247

Schofield, J. W., Eurich-fulcer, R., and Pettigrew, T. F. (2003). “When and how school desegregation improves intergroup relations,” in Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology: Intergroup Processes, eds R. Brown and S. L. Gaertner (Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers Ltd), 475–494. doi: 10.1002/9780470693421.ch23

Schwab, S. (2015). Social dimensions of inclusion in education of 4th and 7th grade pupils in inclusive and regular classes: outcomes from Austria. Res. Dev. Disabil. 43–44, 72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.06.005

Sheridan, J., and Scior, K. (2013). Attitudes towards people with intellectual disabilities: a comparison of young people from British South Asian and White British backgrounds. Res. Dev. Disabil. 34, 1240–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.12.017

Sibley, C. G., and Duckitt, J. (2008). Personality and prejudice: a meta-analysis and theoretical review. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 12, 248–279. doi: 10.1177/1088868308319226

Siperstein, G. N., Glick, G. C., and Parker, R. C. (2009). Social inclusion of children with intellectual disabilities in a recreational setting. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 47, 97–107. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-47.2.97

*Slininger, D., Sherrill, C., and Jankowski, C. M. (2000). Children's attitudes toward peers with severe disabilities: revisiting contact theory. Adapted Phys. Act. Quarter. 17, 176–196. doi: 10.1123/apaq.17.2.176

Steenbeek, H., and van Geert, P. (2008). An empirical validation of a dynamic systems model of interaction: do children of different sociometric statuses differ in their dyadic play? Dev. Sci. 11, 253–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00655.x

*Storey, K., Smith, D. J., and Strain, P. S. (1993). Use of classroom assistants and peer-mediated intervention to increase integration in preschool settings. Exceptionality 4, 1–16. doi: 10.1207/s15327035ex0401_1

*Swaim, K. F., and Morgan, S. B. (2001). Children's attitudes and behavioral intentions toward a peer with autistic behaviors: does a brief educational intervention have an effect? J. Autism Dev. Disord. 31, 195–205. doi: 10.1023/A:1010703316365

*Tan, T. S., and Cheung, W. S. (2008). Effects of computer collaborative group work on peer acceptance of a junior pupil with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Comput. Educ. 50, 725–741. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2006.08.005

UNESCO. (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Paris: UNESCO.