- 1Graduate School of Letters, Yasuda Women's University, Hiroshima, Japan

- 2Department of Social-Psychology, Yasuda Women's University, Hiroshima, Japan

- 3Center for General Student Support, Kochi University, Kochi, Japan

While the special needs education system in Japan has shifted from a segregated approach to a more inclusive one, the actual implementation of this approach may be less than ideal. The implementation of inclusive education faces several challenges, such as difficulty in meeting individual needs and lack of medical support systems in general school settings. With this in mind, we conducted a web-based survey of Japanese schoolteachers to empirically examine their attitudes and perceptions regarding inclusive education. We also sought to determine the socio-environmental and individual factors that affect the attitudes and perceptions of Japanese elementary and junior high school teachers regarding the implementation of inclusive education. Survey results showed that schoolteachers regard the idea of inclusive education as desirable, but not feasible. However, we found that schoolteachers' perceptions of the feasibility of inclusive education implementation were positively associated with their help-seeking preference if they perceived their climate as being sufficiently collegial. Based on these findings, we discuss the educational environment in which inclusive education could be successfully implemented.

Introduction

As of October 2020, 12 years after the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD; United Nations, 2006) came into force, 182 countries around the world have ratified it. Since the Japanese government ratified the Convention in 2014, Japan has taken more steps than ever to promote the social inclusion of persons with disabilities. In line with the Japanese government's aim to create an inclusive society, its educational system has likewise been shifted from a traditional and segregated system to an inclusive one that is promoted and practiced worldwide (MEXT: Ministry of Education Culture Sports Science Technology, 2012). While the practice has grown rapidly, however, it appears that the actual implementation of such a system may be less than ideal. The purpose of this study is to examine the current attitudes and perceptions of Japanese schoolteachers regarding inclusive education, and to examine the factors that could fill any possible gaps between the “ideal” and “reality” of inclusive education in Japan. A web-based survey of Japanese schoolteachers was used for this empirical examination.

There are several methods to assist students with disabilities at schools in Japan according to the severity of their disabilities. The first method is complete segregation (bunri kyoiku in Japanese), where students with disabilities go to schools specially designated for them. These types of schools account for more than 6% of the total number of elementary and junior high schools in Japan. Children without disabilities cannot enroll in such special needs schools. The second method is called the “integrated” method (togo kyoiku in Japanese), in which children with disabilities go to special needs education classes at regular public schools. These classes are set up in ~70% of elementary and junior high schools in Japan. The third method is inclusive education (inclusive kyoiku in Japanese). In this system, children with and without disabilities learn together in the same location. The aim of this system is to strengthen respect for human diversity, and enable students to develop their mental and physical abilities to the maximum extent possible as well as participate effectively in a freer society. Article 24 of the CRPD states, “effective individualized support measures are provided in environments that maximize academic and social development, consistent with the goal of full inclusion” (United Nations, 2006). In Japan, however, the implementation of inclusive education faces several challenges; even though inclusive education has been promoted, Japanese special education is still mainly conducted in a segregated way. Specifically, there are indications that special needs education is still conducted in a segregated manner (Miyoshi, 2009), and that environmental features and medical care services in general school settings are not suitable for the demands of inclusive education (e.g., Hirose and Tojo, 2002; Han et al., 2013; Takahashi and Matsuzaki, 2014). More importantly, Sato and colleagues demonstrated that implementing inclusive education is not considered feasible by most Japanese people (Sato et al., 2019). They conducted three surveys of Japanese participants (i.e., university students, general samples, and people with disabilities) to assess their attitudes and perceptions toward an inclusive education system. Their results consistently showed that all samples underestimated the feasibility of inclusive education, even though they approved of the idea of inclusive education to some extent. These findings suggest that blindly promoting and introducing inclusive education in Japan, without addressing the associated difficulties, may have undesirable consequences—not only for children who enjoy inclusive education, but also the parents and school staff.

Considering the current situation in Japan, we focused on schoolteachers' attitudes and perceptions regarding inclusive education implementation. Their negative attitudes and perceptions regarding the inclusion of people with disabilities could produce environments that limit social participation, hence creating barriers to the implementation of inclusive settings. Therefore, we first attempted to assess their attitudes and perceptions quantitatively through a web-based survey. Furthermore, this study aimed not only to clarify the attitudes and perceptions of Japanese schoolteachers regarding inclusive education, but also to identify the reasons for it and factors necessary for implementing inclusive education. The current study assumes that both environmental and individual factors are key factors for in-service schoolteachers to help them implement inclusive education. One of the individual factors of schoolteachers worth noting, which has attracted attention in educational psychology and school psychology in Japan, is the concept of help-seeking preference. Help-seeking preference refers to the extent to which individual teachers can seek help from others when they are in trouble (Tamura and Ishikuma, 2001). This concept could be crucial for schoolteachers when dealing with problems and helping each other in the field of education. Tamura and Ishikuma (Tamura and Ishikuma, 2001, 2008) noted that helping others in the educational workplace is possible if schoolteachers voluntarily ask colleagues and managers for help. However, schoolteachers' tendency to hesitate to ask for help (and to take things on by themselves) may lead to dismal consequences when difficult problems arise. Miyoshi and Fujiwara (2012) also demonstrated the importance of schoolteachers' help-seeking preferences in a Japanese context. A survey with special needs schoolteachers as its respondents showed that those with a low level of help-seeking preference received support from their colleagues less frequently. Thus, whether or not schoolteachers can build a collaborative team and promote good practices in implementing inclusive education depends on their levels of help-seeking preference.

Although help-seeking preference is an important individual factor, we must also examine environmental factors in the implementation of inclusive education. The current work situation of Japanese schoolteachers is severely demanding. As shown by the report on the Teaching and Learning International Survey (Organisation for Economic Co-operation Development, 2014), Japanese schoolteachers had the longest working time (53.9 h per week) among all schoolteachers in 34 countries and regions. Furthermore, Japanese schoolteachers' long working hours and their mental health problems might be closely related. Recently, schoolteachers' mental health problems have become a pressing issue in Japan. More specifically, the number of leaves of absence due to mental health problems has gradually increased; over the past decades, nearly 5,000 schoolteachers per year take sick leave for mental health problems (MEXT: Ministry of Education Culture Sports Science Technology, 2013). It should be noted that Japanese schoolteachers are currently overworked. Therefore, the Japanese government is attempting to reform the working environments of schoolteachers to one in which they can allocate their school work, effectively coordinate, and advise each other (MEXT: Ministry of Education Culture Sports Science Technology, 2017). In the current situation, we believe that we should not focus on individual factors (i.e., help-seeking preference) alone, but should emphasize the importance of cultivating a collegial climate in which schoolteachers, especially those with low levels of help-seeking preference, are not overburdened. Furthermore, educational psychology and school psychology in Japan have shown the crucial role of collegial climate in school settings. To illustrate, Fuchigami and his colleagues (e.g., Fuchigami, 2005; Nishiyama et al., 2009) argued that the collegial climate, wherein schoolteachers can actively exchange opinions and share information with each other, is essential in all educational activities. Therefore, creating a collegial climate in school may play an important role in implementing inclusive education.

In summary, the purpose of the current study is to quantitatively assess Japanese schoolteachers' attitudes and perceptions toward inclusive education, and determine the effects, if any, of collegial climate and help-seeking preference on these perceptions. Based on previous research (Sato et al., 2019) demonstrating that implementing inclusive education for students with disabilities is generally perceived as not feasible by the Japanese, we sought to confirm the replicability with a sample of in-service Japanese schoolteachers. Furthermore, we also attempted to examine whether or not the characteristics of individual schoolteachers (i.e., help-seeking preference), as well as the environment surrounding them (i.e., collegial climate), are factors associated with that perception.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

The web-based survey was conducted from February to March 2018, after approval from the Ethics Committee at Yasuda Women's University. The questionnaire titled “Survey on Education” was presented to the participants with a brief description and information about the study. Participants were self-selected from a pool of ~4.65 million people including elementary and junior high school teachers, drawn from a marketing company called Cross Marketing CO (http://global.cross-m.co.jp). The marketing company sent e-mail messages to potential participants working in elementary and junior high schools all over Japan, and solicited their participation with monetary incentives. A total of 270 Japanese in-service schoolteachers in public schools (187 men and 83 women, Mage = 49.11, SDage = 10.15) agreed to participate; some participants worked in elementary schools (n = 166) and others in junior high schools (n = 104).

Measures

Participants were asked to complete an online survey questionnaire, presented in Japanese, on the internet, which included questions regarding their gender, age, levels of education, prefecture of residence, and so on. They were then required to read the brief descriptions of segregated, integrated, and inclusive education, as indicated below.

Segregated education: After distinguishing children with or without disability and their type of impairment, children with special needs are educated in special needs schools, and not ordinary schools.

Integrated education: After distinguishing children with or without disability and their type of impairment, children with special needs are educated by being integrated into schools or classrooms in general education settings.

Inclusive education: Regardless of whether children are with or without disability, all of them are educated in educational settings which are created equally and comprehensively, where they learn together.

After reading each description, participants were asked to evaluate three types of education with regard to the following 4 items: (a) appropriateness, (b) desirability, (c) rightness, and (d) feasibleness. These were rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree (1)” to “strongly agree (7).” According to the distinction from previous research (Sato et al., 2019), we decided to create and use the “desirableness” score by summarizing the ratings of (a) appropriateness, (b) desirability, (c) rightness, and the “feasibleness” score based on the ratings of (d) feasibleness as it is. As measured by the seven-point Likert scale, values above the theoretical median of 4 indicate positive attitudes and perceptions, while values below 4 indicate negative attitudes and perceptions.

We also measured Japanese schoolteachers' help-seeking preferences and their perceptions of the organizational climate. Specifically, we administered the existing help-seeking preferences scale (7 items) for measuring schoolteachers' “desire for and attitude toward help,” developed by Tamura and Ishikuma (2001). This scale is highly validated to assess help-seeking preferences of teachers in Japan. This was rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from “does not describe at all (1)” to “describes very much (7).” The prompts included statements such as, “I want someone to talk to when I am in trouble,” and “I want someone to work with me to deal with a problem or difficulty” (α = 0.86). We also utilized scale for measuring organizational collegial climates (Maeda and Hashimoto, 2020) which has been validated to show that collegial climates are negatively associated with risk for burnout in Japanese schoolteachers (Hashimoto and Maeda, 2018). This scale aimed to measure how organizational climates are perceived by schoolteachers. It opened with the following statement: “We will ask you about the teaching staff (e.g., coworkers in the staff room) with whom you are familiar in your school. Please answer how you imagine the following sentences describe them.” We then asked the participants to answer eight items in order to measure the extent of their collegial organizational climate [e.g., “There are many coworkers with whom they (the teaching staff I am familiar with) can mutually discuss problems”]. This was rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree (1)” to “strongly agree (7)” (α = 0.96).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

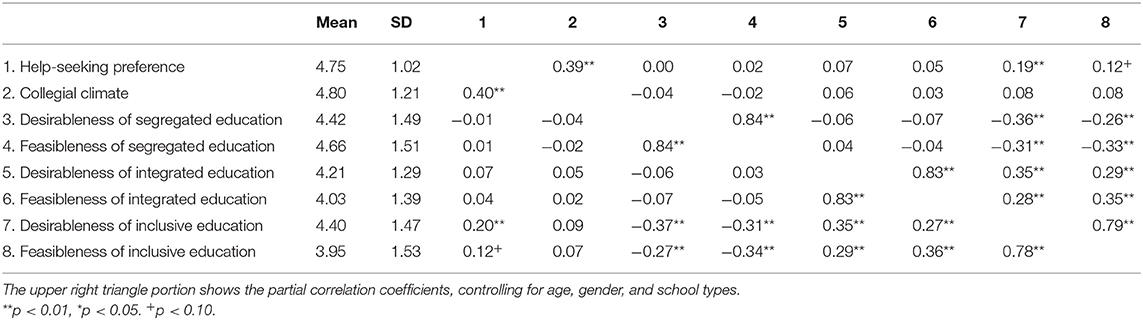

Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients between individual and environmental factors and evaluation scores of desirableness and feasibleness. As shown in Table 1, we found that the mean desirableness score, by generating the scores of appropriateness, desirability, rightness, for inclusive education was 4.40, while the feasibleness score for that was 3.95, below the theoretical midpoints. Furthermore, the result demonstrated that the general evaluation of inclusive education was negatively associated with the general evaluation of segregated education, and positively associated with the general evaluation of integrated education.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlation co-efficients between individual and environmental factors and evaluation scores of desirableness and feasibleness.

Comparison of Desirableness and Feasibleness

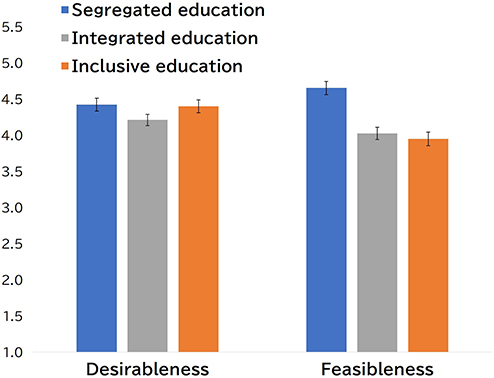

To examine the differences in the schoolteachers' evaluation of the desirableness and feasibleness scores of segregated, integrated, and inclusive education, a 2 × 3 (types of evaluation × types of education) repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed. We found that there were significant main effects of types of evaluation [F(1, 269) = 21.02, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.072], significant main effect of types of education [F(2, 538) = 7.18, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.026], and significant interaction [F(2, 538) = 38.89, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.126]. With regard to desirableness, there were no significant differences in evaluation among the types of education [F(2, 1076) = 1.66, ns., partial η2 = 0.006]; this means that Japanese schoolteachers positively evaluated the desirableness of all types of education (Figure 1). As shown in Figure 1, however, there were significant differences in evaluations with regard to feasibleness [F(2, 1076) = 18.67, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.065], and the scores for segregated education were significantly higher than those for integrated education [t(269) = 3.72, p < 0.001] and inclusive education [t(269) = 3.48, p < 0.001]. These results indicate that Japanese schoolteachers generally regard the implementation of integrated and inclusive education as not being feasible when compared with segregated education.

Figure 1. Japanese schoolteacher's evaluation scores regarding segregated, integrated, and inclusive education.

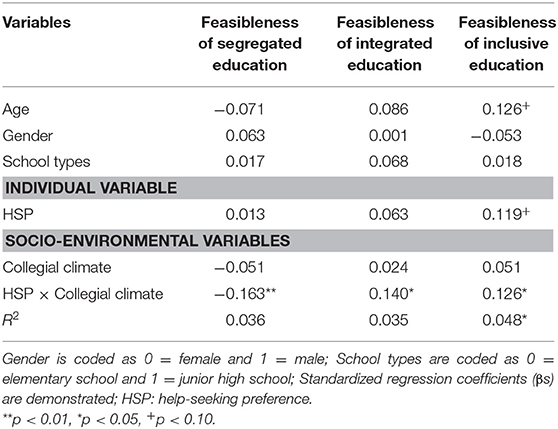

Regression Analysis Predicting the Evaluation of the Feasibleness of Inclusive Education

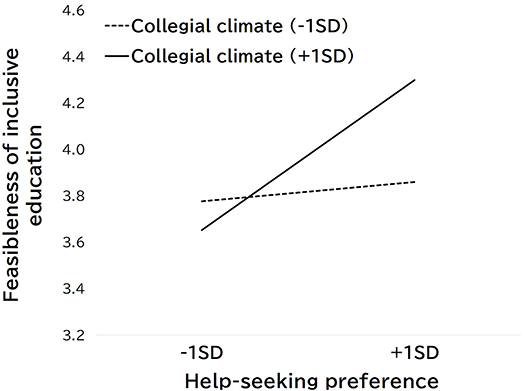

To examine whether or not individual and environmental factors affect the evaluation of the feasibleness of segregated, integrated, and inclusive education, we conducted regression analyses to predict schoolteachers' beliefs regarding feasibleness using five predictors (based on scores for age, gender, school type, help-seeking preference, and collegial climate). However, regression models for the feasibleness of segregated and integrated education did not reach statistical significance but the one for inclusive education did. As shown in Table 2, the results of regression analysis on the feasibleness of inclusive education showed a significant interaction effect between help-seeking preference and collegial climate scores (β = 0.13, p < 0.05). Simple slope analysis revealed that when schoolteachers perceived their climate as being sufficiently collegial, the positive association between their help-seeking preference and their perceptions of feasibleness regarding inclusive education implementation becomes stronger (β = 0.21, p < 0.05). In other words, if schoolteachers could not perceived their climate as being collegial, the impacts of their help-seeking preference on the score of feasibleness becomes no longer statistically significant (β = 0.03, ns.) (Figure 2).

Table 2. Regression analyses to predict feasibleness of segregated, integrated, and inclusive education.

Figure 2. Interaction effect of Japanese schoolteacher's help-seeking preference and their perceived collegial climate (Dependent variable: feasibleness of inclusive education).

Discussion

The present study revealed that Japanese schoolteachers, who play a central role in the implementation of the Japanese education system, doubt the feasibility of implementing inclusive education, even though they perceive inclusive education to be desirable. These findings are consistent with Sato et al.'s (2019) study, which found university students, general samples, and people with disabilities regard the idea of inclusive education as desirable, but not feasible. The findings of the current study are suggestive as Figure 1 demonstrates the gaps between schoolteachers' “ideal” of inclusive education and the “actual” situation. More importantly, our findings also suggest that schoolteachers' perceptions regarding the feasibleness of inclusive education are associated with their individual help-seeking preferences only if they perceive their organizational climate as being sufficiently collegial. That is, our findings suggest that creating a collegial climate among schoolteachers might play an important role in promoting inclusive education and in reducing the perception of Japanese schoolteachers that inclusive education implementation is difficult.

While the social inclusion of people with disabilities is more common on a global scale than ever before, it is worth noting that it may be more difficult to implement in East Asian countries. While our study focused on the attitudes and perceptions of inclusive education only among the Japanese, previous studies reported that schoolteachers' attitudes toward inclusive education are generally negative, especially in non-Western countries (Alghazo and Naggar Gaad, 2004; Malinen and Savolainen, 2008). In the same vein, social inclusion may be regarded as a more complex or difficult issue for people living in East Asian cultures because of the closed strong-tie relations (e.g., Sato et al., 2014; Hashimoto and Yamagishi, 2016; Yamagishi and Hashimoto, 2016; Yuki and Schug, 2020). Further studies that examine how East Asians, such as the Japanese, regard social inclusion, and more importantly, how to promote social inclusion in such cultures, should also be carried out.

In conclusion, it should be noted that our study has some limitations for consideration. Although participants who acquire teaching licenses in Japan are required to learn about special needs education and its history and therefore must have known about the differences between the three types of education, they might have had difficulty visualizing the practicalities of these educational systems because we presented them only with one-sentence explanations. A future study should check the robustness of our results with a concrete way of presenting the three types of education. In addition, we did not ask about schoolteachers' experiences in more detail (for example, their actual experiences in interacting with disabilities) because of the limited questionnaire space. Furthermore, we were unable to control the tendency to acquiesce or the social desirability tendency. However, since elementary and junior high school teachers know that the Japanese government and ministry of education have been promoting an inclusive educational system, the scores of desirableness and feasibleness on inclusive education would have been higher if the social desirability tendency existed. Therefore, our results can be considered robust in this context. However, future study designs should consider these issues. There may be other individual as well as socio-environmental and cultural factors that might play important roles in increasing the perception of feasibility of inclusive education besides help-seeking preferences and collegial climate.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the understanding of how Japanese schoolteachers perceive the ongoing implementation of inclusive education. We believe that providing evidence-based findings will help us consider practical methods for the successful implementation of inclusive education.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee at Yasuda Women's University. Written informed consent was not provided because the survey agency, Cross Marketing CO. (http://global.cross-m.co.jp), sent e-mail messages to potential participants, and encouraged their participation with monetary incentives. Those who did not agree to participate were unable to do so. Therefore, we considered that all participants agreed to participate in our survey.

Author Contributions

KM, HH, and KS contributed to the study design and wrote the whole part of manuscript. KM and HH conducted data collection and data analysis. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Funding

This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid 16K13458 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Alghazo, E. M., and Naggar Gaad, E. E. (2004). General education teachers in the United Arab Emirates and their acceptance of the inclusion of students with disabilities. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 31, 94–99. doi: 10.1111/j.0952-3383.2004.00335.x

Fuchigami, K. (2005). The Psychology of a School System. Nihon Bunka Kagakusha Co., Tokyo (In Japanese.)

Han, C., Kohara, A., Yano, N., and Aoki, M. (2013). The current situation and issues of inclusive education for special needs education in Japan: a present state analysis and comparative analysis. Bull. Faculty Educ. University of the Ryukyus 83, 113–120.

Hashimoto, H., and Maeda, K. (2018). Collaborative Organizational Climate Alleviates Teachers' Risk for Burnout: An Interaction Between Help-Seeking Preferences and Organizational Climate. Paper presented at the 40th International School Psychology Association Conference (Tokyo, Japan).

Hashimoto, H., and Yamagishi, T. (2016). Duality of independence and interdependence: an adaptationist perspective. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 19, 286–297. doi: 10.1111/ajsp.12145

Hirose, Y., and Tojo, Y. (2002). Current situation of education for children with autism in regular classes II: features of individual children and teacher needs. Bull. Natl. Institute Special Educat. 29, 129–137.

Maeda, K., and Hashimoto, H. (2020). Exploring the potential of the practice of Inochi-tendenko in current disaster prevention education: the interaction effect of teachers' attitudes toward disaster prevention education and the organizational climate in schools. Jpn. J. Soc. Psychol. 35, 91–98. doi: 10.14966/jssp.1830

Malinen, O. P., and Savolainen, H. (2008). Inclusion in the east: chinese students' attitudes towards inclusive education. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 23, 101–109.

MEXT: Ministry of Education Culture Sports Science and Technology (2012). Promoting special needs education to construct inclusive education system that formulates convivial society (Report). Retrieved from: https://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/shingi/chukyo/chukyo3/044/attach/1321668.htm (accessed April 10, 2020).

MEXT: Ministry of Education Culture Sports Science and Technology (2013). Teachers' Mental Health Measures (Final report).

MEXT: Ministry of Education Culture Sports Science and Technology (2017). White paper of MEXT. Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Tokyo.

Miyoshi, M. (2009). A study on contact between special support education and inclusive education: Possibility of establishment of inclusive education practice in Japan. Human Environ. Stud. Kyoto University 18, 27–37.

Miyoshi, Y., and Fujiwara, T. (2012). Factors influencing the use of school support systems by special needs education teachers at elementary schools in relation to workplace environment, teachers' help-seeking preferences, and experiences of support. Jpn. J. Sch. Psychol. 12, 3–14.

Nishiyama, H., Fuchigami, K., and Sakoda, Y. (2009). Interconnection of factors influencing embeddedness of school counseling and guidance: an empirical study. Jpn. J. Educ. Psychol. 57, 99–110. doi: 10.5926/jjep.57.99

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2014). TALIS 2013 Results: An International Perspective on Teaching and Learning. Paris: OECD Publishing. Retrieved from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/talis-2013-results_9789264196261-en (accessed April 10, 2020).

Sato, K., Hashimoto, H., and Maeda, K. (2019). Difficult situation of people with disabilities in Japan: feasibility of inclusive education, well-being, and social barriers from people with/without disabilities. Paper presented at the 7th Asian Congress of Health Psychology 2019, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia.

Sato, K., Yuki, M., and Norasakkunkit, V. (2014). A socio-ecological approach to cross-cultural differences in the sensitivity to social rejection: the partially mediating role of relational mobility. J. Cross-Cultural Psychol. 45, 1549–1560 doi: 10.1177/0022022114544320

Takahashi, J., and Matsuzaki, H. (2014). The changes and problems in inclusive education. Bull. Faculty Human Dev. Culture Fukushima University 19, 13–26.

Tamura, S., and Ishikuma, T. (2001). Help-seeking preferences and burnout: Junior high school teachers in japan. Jpn. J. Educ. Psychol. 49, 438–448. doi: 10.5926/jjep1953.49.4_438

Tamura, S., and Ishikuma, T. (2008). Influence factors of help-seeking preferences among junior high school teachers in Japan. Jpn. J. Counsel. Sci. 41, 224–234.

United Nations (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf (accessed April 10, 2020).

Yamagishi, T., and Hashimoto, H. (2016). Social niche construction. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 8, 119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.10.003

Keywords: disability, inclusive education, special needs education, help-seeking preference, collegial climate

Citation: Maeda K, Hashimoto H and Sato K (2021) Japanese Schoolteachers' Attitudes and Perceptions Regarding Inclusive Education Implementation: The Interaction Effect of Help-Seeking Preference and Collegial Climate. Front. Educ. 5:587266. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.587266

Received: 19 August 2020; Accepted: 15 December 2020;

Published: 14 January 2021.

Edited by:

Ann X. Huang, Duquesne University, United StatesReviewed by:

Shakila Dada, University of Pretoria, South AfricaMing Lui, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong

Copyright © 2021 Maeda, Hashimoto and Sato. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hirofumi Hashimoto, aGlyb2Z1bWloYXNoaW1vdG9Ab3V0bG9vay5jb20=

Kaede Maeda

Kaede Maeda Hirofumi Hashimoto

Hirofumi Hashimoto Kosuke Sato

Kosuke Sato