- 1Department of Health and Human Development, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

- 2Department of Counseling and Special Education, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, United States

- 3Department of Psychology, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, United States

- 4Department of Educational Studies, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, United States

- 5Applied Developmental Science and Special Education, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, United States

- 6Department of Educational Psychology, Counseling, and Special Education, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, United States

- 7College of Social Sciences and Humanities, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, United States

We focus on the inclusion of socially vulnerable early adolescents including students with special education needs (SEN). Building from multiple intervention and randomized control trials of a professional development model aimed at supporting teachers' management of the classroom social context, we provide an overview of the Behavioral, Academic, and Social Engagement (BASE) Model as a framework to foster social inclusion. We briefly review the conceptual foundations of this model and we present the delivery (i.e., directed consultation, the scouting report process) and content (i.e., Academic Engagement Enhancement, Competence Enhancement Behavior Management, Social Dynamics Management) components of BASE. We then briefly discuss the intervention support needs of subtypes of socially vulnerable youth and how these needs can be differentially addressed within the BASE framework.

Many students are concerned about social difficulties during the late elementary and middle school years (Graham et al., 2006; Rice et al., 2011). This is particularly true for early adolescents with special education needs (SEN) who are at increased risk for peer rejection, social isolation, and involvement in peer victimization (Frederickson and Furnham, 2004; Estell et al., 2009a; Sullivan et al., 2015). The Behavioral, Academic, and Social Engagement (BASE) Model was developed as a holistic, ecological classroom management approach that teachers can use to support socially vulnerable youth during the transition to middle school. Our goal is to describe the application of the BASE model for supporting the inclusion of distinct subtypes of students with SEN during the late childhood and early adolescent school years.

We address five aims. We begin with an overview of the social inclusion of students with SEN. Then, we build upon a person-in context dynamic systems perspective to describe the theoretical foundations of the BASE model. Next, we summarize the intervention components and practice elements of the BASE model and their linkages to key social development process variables typically experienced by early adolescents. Building on research using latent profile analysis of interpersonal competence, we discuss three distinct configurations or subtypes of socially vulnerable youth: popular aggressive; passive; and low-adaptive (i.e., multi-risk). Finally, using these configurations and associated adjustment factors as a guide, we illustrate how teachers can use the BASE model to adapt strategies and supports for each subtype. We focus on how teachers need to be attuned not only to the differential needs of sub-types of youth, but to also be aware that their management of the classroom experience of students characterized by different configurations may contribute to how subtypes of students are perceived by their classmates and their corresponding relationships and social roles in the peer ecology.

Overview of the Social Inclusion of Students With SEN

Compared to youth who do not receive special education, students with SEN have elevated rates of social difficulties. This includes increased risk for involvement in bullying both as a perpetrator and a victim (Blake et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2015; Rose and Gage, 2017) as well as feeling as though they do not belong in the classroom or school (Sullivan et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2019; Musetti et al., 2019). In addition, higher proportions of students with SEN are socially isolated (i.e., not a member of a peer group: Pijl et al., 2008; Farmer et al., 2011) or are not well liked by peers (i.e., rejected sociometric status: Estell et al., 2008; Pijl and Frostad, 2010; Bossaert et al., 2015). Further, of the students with SEN who are members of peer groups, many tend to affiliate with classmates who share their social difficulties and who may support and sustain their social problems (Estell et al., 2009a; Farmer et al., 2011; Banks et al., 2018).

Although, as a group, students with SEN are socially vulnerable and are at increased risk for poor inclusion in the classroom community, there is considerable variability in the social experiences of subtypes of youth with disabilities. For example, students with SEN are a socially heterogeneous group and are represented in a range of profiles and patterns of involvement in bullying including low or no involvement, decreasing involvement, and increasing involvement (e.g., Chen et al., 2015; Winters et al., 2020). Also, although students with SEN have elevated rates of low acceptance most do not have rejected status and many have positive social roles and reputations in the peer system (Stone and La Greca, 1990; Juvonen and Bear, 1992; Estell et al., 2008). Further, although 10–20% of students with SEN are socially isolated, the majority are members of peer groups and have close friendships that, in some cases, appear to support their adjustment in school (Pearl et al., 1998; Estell et al., 2009b). Using person-oriented analytic approaches, subtypes of youth, including students with SEN, have been identified who have distinct interpersonal competence patterns (ICPs) on teacher ratings of their academic, behavioral, and social functioning (Farmer et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2019). In turn, these ICPs are associated with different levels of school belonging and social experiences in inclusive classroom settings.

Variability in the inclusive experiences of students with SEN appears to reflect the interplay between the characteristics of students with SEN, the characteristics of the broader social system, the relationship and interactions of students with school adults, and the general functioning of the classroom ecology (Farmer et al., 2018c; Hymel and Katz, 2019; Juvonen et al., 2019). Building from a person-in-context dynamic systems perspective, it is possible to develop approaches in which teachers are attuned to the general classroom social dynamics and the experiences of students with SEN (Farmer et al., 2019). A person-in-context dynamic systems framework is critical for understanding how the academic, behavioral, and social experiences of students in the classroom come together to contribute to the social inclusion of students with SEN and their relations with their classmates. In turn, this information can be leveraged into a systematic approach for managing effective inclusive classroom ecologies.

A Person-in-Context Dynamic Systems Perspective of Inclusion

Social inclusion is not simply a process of putting students with SEN in the same general education classroom with peers who do not have SEN. On the contrary, social inclusion involves fostering the adaptive interplay between youth and contexts. This person-in-context perspective involves the integration of ecological and dynamic systems theories of youth development.

From an ecological-systems perspective, students are embedded in nested social systems including: the microsystem (i.e., proximal social settings, social roles, and relationships); the mesosystem (i.e., the interrelations among the major proximal social settings of the student); the exosystem (i.e., formal and informal social structure that do not directly contain the student, but influence the student's experiences); and the macrosystem (i.e., overall institutional structures including legal, political, and cultural factors that contribute to the other systems: Bronfenbrenner, 1977). From a dynamic systems perspective, youth develop as an integrated whole by engaging with these various ecological subsystems. Reflecting the concept of a system, the characteristics of individual students (e.g., biophysical, behavioral, cognitive, psychological, self-regulatory) are bidirectionally linked to each other and to the contexts in which they are embedded (e.g., family, peer group, classroom, school, community, culture, sociopolitical structures) such that they influence each other as they coactively contribute to the moment-to-moment functioning and adaptation of the student (Bronfenbrenner, 1996; Cairns, 2000; Smith and Thelen, 2003).

A person-in-context perspective is critical for understanding the complexity of social inclusion. Because individual and ecological factors operate together as a system, they tend to constrain each other and promote stability in patterns of behavior and functioning (Magnusson and Cairns, 1996). This means that efforts to change one factor (e.g., the student's social behavior, how peers perceive and treat classmates who are different from themselves) are likely to have a modest and short-lived impact if other factors (i.e., correlated constraints) do not change in corresponding ways (Cairns and Cairns, 1994; Farmer et al., 2021). In the classroom setting, moment-to-moment activities and interactions contribute to each student's overall experiences and functioning. There are three correlated domains of school functioning that are key for the inclusion of students with SEN in the classroom community: academic, behavioral, and social. Accordingly, building from a dynamic person-in-context perspective, it is beneficial for teachers to manage the classroom ecology in ways that approach academic instruction, behavior support, and social engagement as an integrated system of correlated factors.

The direct intervention activities that teachers are most likely to engage in involve micro- and macro-ecological systems. Accordingly, the interventions outlined in this paper focus on more proximal ecological factors. However, exo- and macro-systems are equally important for effective intervention because structural, cultural, and socio-political factors can strongly impact social inclusion. To address the contributions or constraints of exo- and macro-system factors, it is necessary to have a dynamic and malleable professional development training and support system to help tailor intervention strategies across different communities and schools. This includes identifying the strategies that are most likely to be effective in a particular setting and guiding teachers in the adaptation of the practice elements of evidence-based programs to the strengths, resources, and needs of specific students, classrooms, schools, and communities. While our discussion centers on strategies teachers use in the classroom, we briefly describe professional development approaches (e.g., directed consultation, the scouting report) that intervention or inclusion specialists can use to support general education teachers as they work to effectively tailor strategies to the needs of students and classrooms.

The Behavioral, Academic, and Social Engagement (Base) Model

The BASE model was developed from research on classroom social dynamics in elementary and middle schools as well as intervention efforts to infuse a person-in-context dynamic systems perspective into teachers' management of the instructional, behavioral, and social functioning of students in moment-to-moment daily activities (see Farmer et al., 2013, 2019 for reviews). BASE has been evaluated in multiple small-scale randomized control trials involving two or more schools during intervention development activities as well as two large-scale cluster randomized trials (CRT) with 36 rural schools across 10 states in one CRT and 24 metropolitan schools across two states in a second CRT. Findings of these evaluations suggest that teachers trained in the base model are more attuned to classroom social dynamics and students' social roles and relationships (Farmer et al., 2010a; Hamm et al., 2011a), have a greater sense of their efficacy to support students (Farmer et al., 2010b), and are more likely to use positive instructional and classroom management strategies and are less likely to use reactive negative approaches (Motoca et al., 2014).

Collectively, evaluations of the BASE model suggest that in schools in which teachers were trained in BASE strategies, students were more likely to be productively engaged in the classroom community and to have positive social experiences. Academically and behaviorally struggling students were more likely to perceive that the peer culture is supportive of positive academic effort and acheivement (Hamm et al., 2014) and to perceive that the classroom is supportive of them and that they belong (Hamm et al., 2011a). Students with behavioral risks in BASE classrooms were more likely to develop postive peer affilations with prosocial classmates (Farmer et al., 2010b) and students with SEN perceived less peer support for bullying directed agianst them (Chen et al., 2015). Further, students from racial and ethnic minorities tend to have more positive experiences in BASE classrooms. Native American students in BASE classrooms viewed the peer culture to be more supportive of academic engagement and achievement and to be less socially risky and they tended to have greater academic engagement and demonstrated improvement in academic grades and test scores (Hamm et al., 2010). Likewise, African American and Latino youth in BASE schools reported less defiance toward teachers and a greater willingness to protect peers from bullying (Dawes et al., 2020) and they perceived less discrimination from peers or teachers (Marraccini et al., under review).

The core of the BASE model is to be responsive to the strengths, needs, and opportunities of students and teachers in relation to cultural, ecological, and socio-political factors (e.g., meso-system) that impact the resources and expectations of the school community (exosystem). To ensure that the BASE model can be tailored to specific communities, schools, teachers, and students, we use a professional development model known as directed consultation (DC) and an ecological assessment approach that is known as the Scouting Report. This work is typically conducted by an intervention or inclusion specialist as a resource to support general education teachers as they work to promote and maintain an inclusive classroom environment.

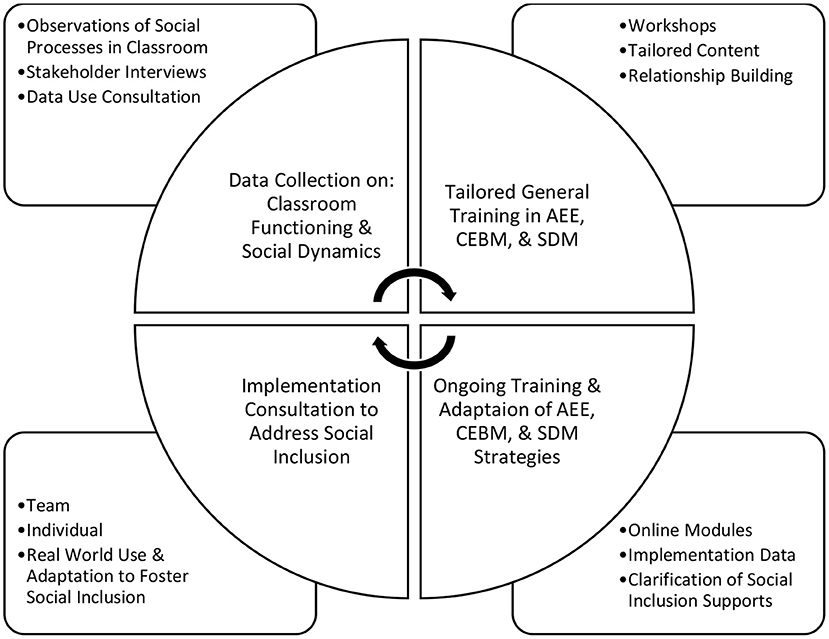

Directed Consultation

Directed consultation (DC) is a professional development and intervention support model designed to integrate practice elements of evidence-based programs (EBPs) into daily classroom activities (Farmer et al., 2013). Reflecting the need to be responsive to exo- and meso-system factors, the DC approach consists of four components that are conducted in an iterative and recursive fashion to tailor strategies to the specific features of students, classrooms, schools, and communities. As outlined in Figure 1, the DC process involves ongoing data collection; tailored general training; ongoing support; and implementation consultation (Motoca et al., 2014; Farmer et al., 2018b). The ongoing data collection component involves observations, interviews, and data use consultation to assess resources, strengths, needs, and current practices (see the scouting report below). The tailored general training component builds on information generated from the data collection and using this data to guide a series of professional development activities including workshops with tailored content and relationship building strategies that focus on matching practice elements of relevant EBPs to the resources, needs, and strengths within the classroom or other focal settings. The ongoing support component includes targeted online modules that are designed to address specific areas of need, the collection of implementation data, and guidance to address issues in implementation such as difficulty with the use of specific strategies, clarifying concerns about lack of fidelity, and resolving potential mismatches between strategies, circumstances, and needs. The implementation consultation component is a structured problem-solving process aimed at tailoring assessments and interventions to specific issues, circumstances, and contexts. These strategies are typically conducted by an intervention or inclusion specialist who uses local data and data collected in the scouting report process to guide teachers in the adaptation of the practice elements of EBPs to the circumstances that need to be addressed in the specific context. Local data may include data on trends for key variables related to students' school functioning such as discipline, school absences, academic performance, services received, involvement in bullying, and other student school adjustment variables. These data can be considered for individual students in relation to students overall and students with SEN as well data linked to individual teachers. This information can help to contextualize the overall experiences of specific students as well as the support needs of specific teachers.

The Scouting Report

The Scouting Report is a data collection approach designed to operate within the directed consultation process to clarify the general social functioning of the classroom or school, the values and systems that are in place that contribute to the overall climate and culture of the focal ecology, community strengths and constraints, current teacher practices, resources and supports available to the teacher, and the intervention support needs of focal students (Farmer et al., 2016a). A major goal of the scouting report is to link the practice elements of EBPs to developmental leverage points and processes that are most likely to have an impact in relation to the current ecology and circumstances (Farmer et al., 2013, 2018b).

For the purposes of fostering social inclusion, it is helpful to assess the general social dynamics in the classroom early in the scouting report process (Farmer et al., 2019). This can involve a variety of formal surveys and sociometric assessment procedures to determine the social relations and social functioning of specific students as well as the overall classroom (Farmer et al., 2012; McKown, 2019). However, it is possible to gain actionable information to guide the intervention adaptation process by conducting: structured interviews; observations of the general focal context; observations of synchronous social interactions between focal students and other key players in the classroom; and post-observation interviews to further clarify what was observed (Farmer et al., 2016a, 2018a).

This work should be guided by the goal of assessing the overall functioning of the peer system and clarifying patterns of social synchrony (i.e., mutual support of each other's behavior) between the focal student, the teacher, students who are prominent and powerful in the social system, and students who are socially marginalized (Farmer et al., 2016b). The scouting report begins with pre-observation interviews in which teachers, students, and other stakeholders (e.g., principal, special education teacher) are asked about how the student gets along with others in the classroom including strengths and difficulties. This is followed by observations that focus on: the placement of the focal student in the social ecology; the frequency and valence of the focal student's interactions with others; the teacher's active management of the social system; the identification of key social actors for the focal student; and the observer's impressions of the social processes that appear to influence or impact the student (Farmer et al., 2016a).

In addition, teachers are typically asked to keep weekly logs of all the peer groups they are aware of in the classroom (i.e., attunement) and to use this information to help guide instructional and behavior management strategies by effectively harnessing the power of peers in the intervention process (Farmer et al., 2019). Often social dynamics management is not the sole or primary intervention. Rather it tends to serve as a context intervention that is designed to augment, complement, and reinforce more explicit and individually focused social interventions (Farmer et al., 2018c; Bierman and Sanders, 2021). The goal is to help teachers become an “invisible hand” who infuse their knowledge of social dynamics into the moment-to-moment management of classroom activities in unobtrusive ways that facilitate important experiences and opportunities for children and youth who are socially vulnerable (Farmer et al., 2018a).

The BASE Model Theory of Change

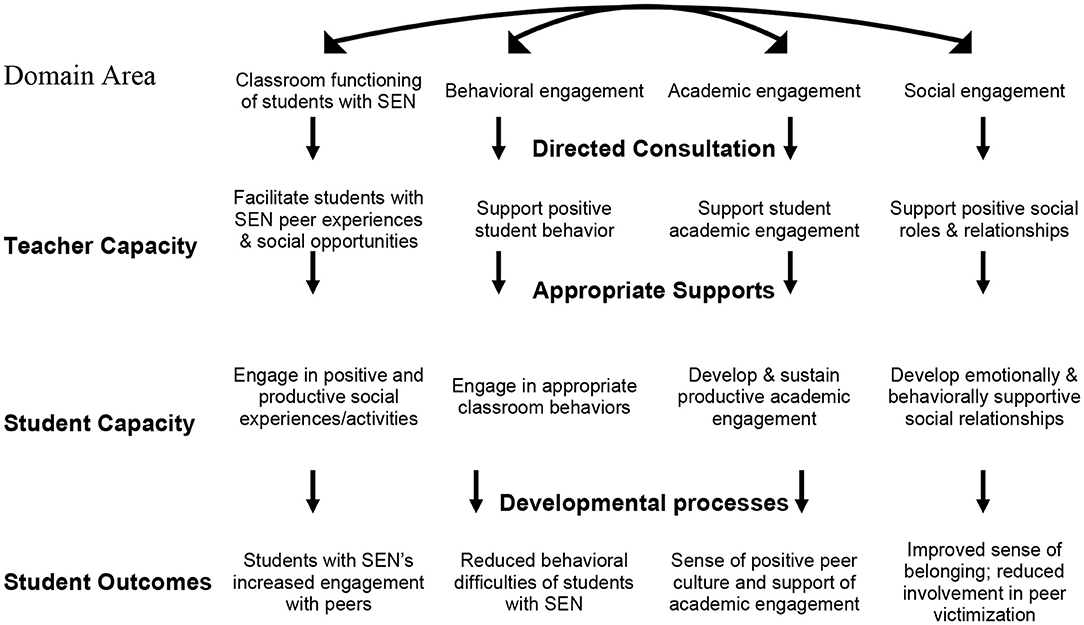

The BASE Model theory of change is shown in Figure 2. As depicted by the bi-directional arrows at the top of the model, the BASE social inclusion model involves four domains of school functioning (i.e., the classroom functioning of students with SEN, behavioral engagement, academic engagement, and social engagement) that are linked to each other and that collectively contribute to the adjustment and adaptation of students with SEN and students who experience social difficulties. The fact that these factors are linked in a dynamic system means that teachers are not intervening with them in isolation. Rather, as teacher engage in one domain they must be attuned to and cognizant of the potential impact of their efforts on other domains and they should also consider how each of the other domains may constrain or influence their efforts on the focal domain. With directed consultation, interventions specialists provide professional development training that is tailored to the context and that focuses on promoting teachers' capacities to facilitate students with SEN's peer experiences and opportunities as they manage the behavioral, academic, and social domains at the individual student and classroom contexts levels. The goal is for the teacher to provide appropriate supports at each of these domains. Accordingly, the intervention specialist monitors teachers' implementation of needed strategies and collects data on student functioning and changes in their capacity and outcomes in relation to the use of specific strategies and the impact of the classroom context. The BASE model is designed so that the focus is not only doing everything in a lock-step fashion. Rather the goal is to tailor strategies and supports to the needs of the students, the characteristics of the context and the capacities of the teachers. The three intervention components of the BASE model are presented below individually but it is expected that they are integrated in delivery and implementation with the collective goal of enhancing the classroom functioning of students with SEN and students with or at-risk of social adjustment difficulties.

Academic Engagement Enhancement

How teachers interact with and engage students in instruction not only has an academic impact, it also contributes to students' peer relations and their social identity (Vollet et al., 2017; Hymel and Katz, 2019). Peer relations and peer cultures contribute to students' academic motivation, their academic effort, and their sense of belonging in the classroom (Hamm et al., 2014; Kindermann, 2016; Wentzel et al., 2017). How teachers manage the academic context, in part, depends on their ability to leverage the social context to promote a climate where students feel safe to take academic risks, engage in instruction, and collaborate to support each other's academic success (Hamm et al., 2012; Vollet et al., 2017). When teachers are attuned to classroom social dynamics and use this information to promote an academically supportive classroom society, they are better positioned to foster the successful inclusion of socially vulnerable youth (Gest et al., 2014; Farmer et al., 2019; Hymel and Katz, 2019). The BASE model is designed to harness the power of peer processes in instruction.

Academic instruction is the central focus of school classrooms. Accordingly, the Academic Engagement Enhancement (AEE) component is the foundation of the BASE model and its overarching goal is to create a classroom culture that promotes the productive academic engagement of all students. When providing supports for students with differential needs, it is critical to engage them in non-obtrusive ways that do not call attention to their differences. This means that things should be done in a matter-of-fact manner that does not hide differences, but that makes it normal that everyone in the class has different needs (McLesky and Waldron, 2007). Working within a Tiered System of Adaptive Supports (TSAS) framework, adaptive universal supports should be provided in Tier 1. This does not mean that everyone gets the same thing (Farmer, 2020). In a TSAS model, “universal” means that the context is structured to provide adaptive differential supports tailored to promote the routine daily functioning of all students whatever their needs may be (Sutherland et al., 2018; Hymel and Katz, 2019; Farmer et al., 2021).

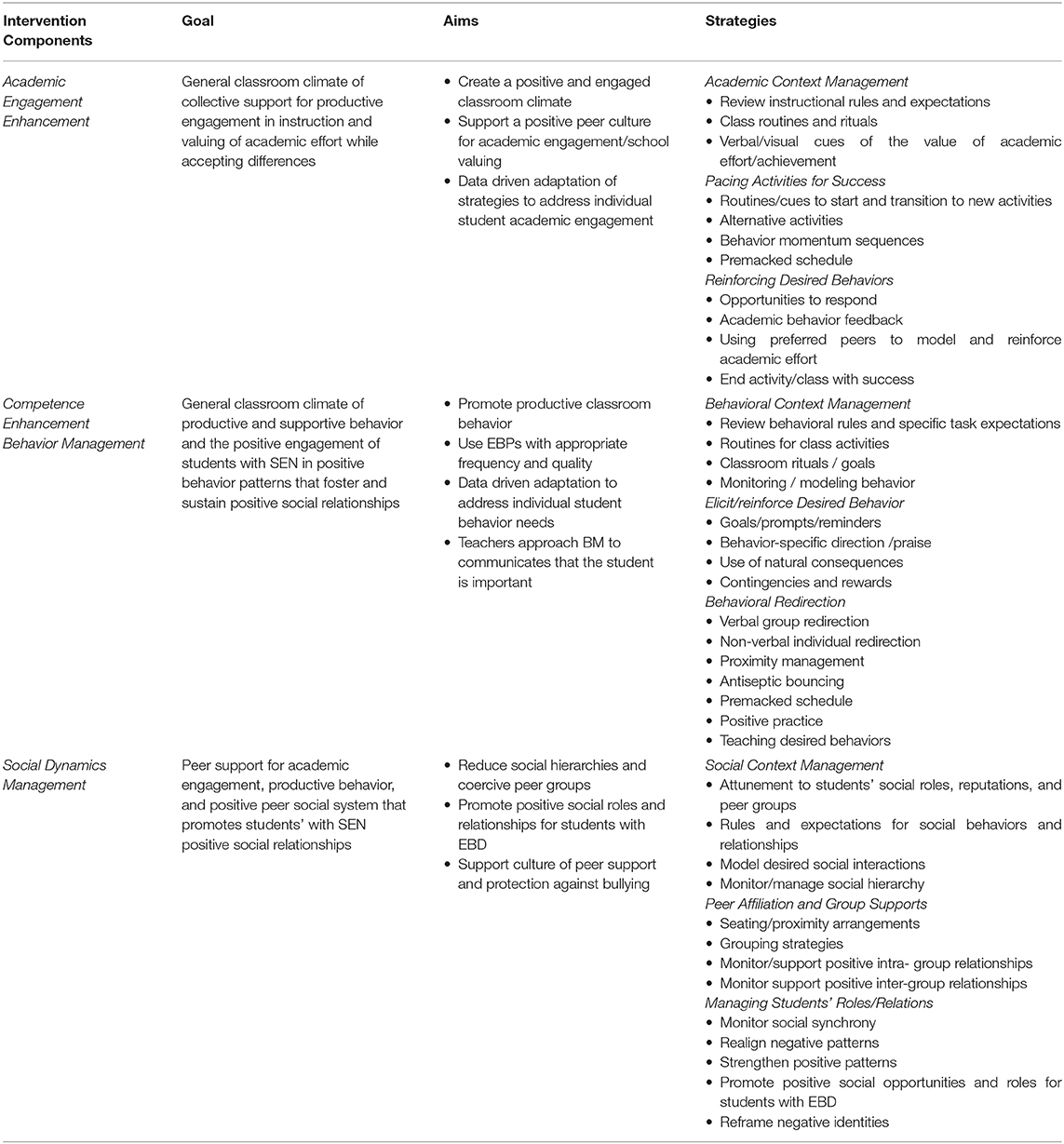

As indicated in Table 1, the aims of the AEE component are to promote a positive and engaged climate, to promote a peer culture that supports academic engagement valuing, and to use data to guide the adaptation of routine daily strategies to the needs of individual students. To achieve this, the AEE component is organized into three distinct but complementary categories of instructional management strategies: academic context management, pacing activities for success, and reinforcing desired behaviors.

Academic Context Management

Academic context management is part of the general management of the classroom and should complement the context management features of the other two BASE components (i.e., behavioral, social). There are a variety of strategies to manage the academic context. This includes: rules and expectations that are reviewed at the beginning of the instructional activity to provide the parameters for the expected behaviors and actions within a specific assignment; routines and rituals that provide an organizing framework for common tasks which communicates a sense of specialness and sacredness to specific events or processes and promotes a collective atmosphere where everyone feels a shared sense of connectedness; and verbal and visual cues to help students develop a collective positive mindset about instructional engagement by having quotes, slogans, and mission statements that communicate the value of academic effort and achievement that permeates the performance of daily activities. With each of these strategies, the purpose is to make academic life predictable, comfortable, and socially supported in ways that help all students feel like they belong and can be successful.

Pacing Activities for Success

An important part of managing the academic context involves structuring classroom experiences so that they result in successes that are meaningful and valued by students. Teachers can organize instruction and activities to ensure this is the case. To do this, it is helpful to have a range of pacing strategies that prepare the student for an activity, set the tone and mindset that the activity will be completed successfully, prompt and monitor the speed at which students are completing tasks, and break tasks down into doable parts that build toward sustained activity and success. Strategies to do this include: routines to start and transition to new activities to ensure students are prepared and to make the shift to a new task familiar, comfortable, and doable; alternative or warm-up activities for students who cannot start a new task independently and who will need individualized guided support from the teacher once the teacher has completed instruction for the larger group; Behavior momentum or high p sequencing of instructional tasks that are difficult for a student by using high probability tasks (i.e., preferred tasks the student can complete with success) to directly proceed and build up momentum to support the student's effort in low probability (i.e., less preferred tasks that the student struggles to complete successfully: Lee, 2006; Knowles et al., 2015); and a Premack Schedule or grandma's law (e.g., you can't eat your dessert until you finish your vegetables) to structure academic tasks where students work to complete a less preferred activity so they can do a high-preferred activity (Hosie et al., 1974; Billingsley, 2016).

When pacing activities, it is important to be cognizant that two distinct audiences are taking in information about the teacher's instructional interactions with individual students. These interactions communicate information to focal students (i.e., the students receiving the instruction) and classmates (i.e., students who are part of the public community in which the instruction is taking place). For focal students, they are aware of their own academic difficulties and they are aware that their instructional interactions with the teacher may impact how others view them, which, in turn, may impact their social roles and relationships. For classmates, they are receiving information about the student but they are also gathering information about how to interact with others, whether the teacher will put them on the spot, and whether it is socially safe to be academically engaged and to take risks. When teachers take the time to pace and structure activities to ensure the success of all students, they are building the foundation for a supportive community that values the dignity of others and that understands they are part of a society in which the experiences, opportunities, and roles of individuals are important for the collective.

Reinforcing Desired Behaviors

The reinforcement of desired behaviors is critical for classroom management and for creating an inclusive, supportive, and egalitarian social system. However, reinforcement is often misunderstood and in, many cases, it is not applied effectively (Shores and Wehby, 1999). Teachers frequently interpret reinforcement to mean giving a student something that is pleasant; something they should like or want. In actuality, reinforcement is “defined objectively by two facts: a contingency between a behavior and its consequences, and a strengthening of the behavior (Cullinan et al., 1983, p. 77). Desired behaviors can be reinforced in a variety of ways. The BASE model focuses on four approaches that can be incorporated in classroom management strategies to support all students while being tailored to the needs of specific students. These strategies are opportunities to respond; academic behavior feedback; using preferred peers to model and reinforce academic effort; and ending specific activities and the class with success.

Opportunities to respond (OTR) involves giving students the chance to actively answer or perform academic requests (Sutherland and Wehby, 2001). There are various approaches to OTR including individual, choral, and mixed (Haydon et al., 2010). When teachers increase OTR, students with problem behavior tend to experience corresponding increases in task engagement and correct responses, and decreases in disruptive behavior (Sutherland et al., 2003). In many respects, opportunities to respond are both a pacing strategy and a reinforcing strategy. They pace the student by providing prompts and a structure for staying engaged. They also reinforce the student's behavior as the process of answering requests increases engaged behaviors (Sutherland and Wehby, 2001).

Academic behavior feedback is not about telling students whether or not they have the correct answer. Academic feedback teaches and motivates students about how to work to get the correct answer. Students develop mindsets about their ability to complete academic tasks that can promote or impede sustained engagement in instruction. Students self-efficacy for academic success is influenced by whether they view intelligence as a fixed quantity they either do or do not possess (i.e., a fixed mindset) or a malleable quantity that reflects a growth mindset in which they believe intelligence can be increased or improved with effort and learning (Dweck and Leggett, 1988). To foster a growth mindset, learning goals, and persistent on-task behavior, teachers can communicate to students that it is okay to struggle, effort is important, and that the focus is not the correct answer but learning how to get the correct answer. When providing instructional guidance, it is critical to consider whether a prompt elicits a growth or fixed mindset and learning or performance goals, and whether the outcome reinforces productive academic behavior. Through this lens, teachers can turn perceived difficulties into positive opportunities to learn and when a student gets something wrong can say “that's great because you are learning; now let's see what happens if you try it a different way.”

Using preferred peers to model and reinforce academic effort is a strategy that recognizes that academic engagement tends to be a public event and uses the power of peers to promote students' productive effort. On one hand, students who struggle academically may be concerned about their performance and avoid engagement so others will not see their difficulties. On the other hand, students may be concerned that classmates will think it is not cool to work hard (Juvonen and Murdock, 1995; Ryan and Pintrich, 1997). It is often necessary for teachers to make academic engagement safe in two distinct ways. First, there is a need to make tasks doable by using differentiation and behavior momentum strategies to promote the likelihood of success. Second, it is necessary to help students see that engaging in instruction will not compromise their social image. When students view classmates as supportive of academic effort and tolerant of mistakes, they tend to report greater interest in school (Wentzel, 2003), have a more favorable sense of belonging (Hamm et al., 2010), and demonstrate greater academic initiative (Danielsen et al., 2010). To create this type of supportive culture and foster the productive engagement of students, it is helpful for teachers to be aware of classmates that struggling students look up to or are influenced by (a preferred peer) and use them as an ally to make instructional engagement safe and rewarding.

Ending a class on success seems intuitive and easy to achieve. This is often not the case. Teachers' and students' interaction patterns and relationships tend to be synchronized with the behavior of each influencing the behavior of the other (Farmer et al., 2018a; Sutherland et al., 2018). In some cases, a curriculum of non-instruction may occur where teachers and students develop an implicit truce in which the teacher does not expect the student to engage in activities the student is not comfortable doing and, in turn, the student will not escalate problem behavior (Gunter et al., 1993; Shores and Wehby, 1999). This approach does not promote success. It just avoids problems. In other cases, the teacher may become angry or feel a need to prove a point to the student. Rather than helping the student experience success, the teacher may challenge the student, thwart a sense of accomplishment, and promote coercive interchanges that at best alienates the student and may also prompt disruptive, aggressive, and explosive behavior patterns (Shores et al., 1993; van Acker et al., 1996). When teachers structure the beginning of class to ensure students start off productively, use momentum strategies along with supportive academic feedback and OTR to pace the student toward success, and use preferred peers and a Premacked schedule to sustain engagement, it should be possible to end an activity or class on success. The goal is to help struggling students see that they can be productive, build patterns of behavior that foster resilience, and increase the likelihood they will approach tomorrow's class ready to learn (Lee, 2006; Billingsley, 2016).

Competence Enhancement Behavior Management

The Competence Enhancement Behavior Management (CEBM) component of the BASE model centers on managing the classroom, the behavior of specific students, and the interplay between students and contexts in ways that make differences normal and behavioral supports non-stigmatizing (Farmer et al., 2006; McLesky and Waldron, 2007). This requires using EBPs and data driven practices to adapt strategies to balance the needs of specific students and the general classroom ecology (Sutherland et al., 2018). In addition, it is helpful for teachers to approach behavior management with a positive mindset, have high expectations for students, use problems as opportunities to teach desired behaviors, and communicate to students that they are worth taking the time to ensure they learn to do things correctly (Farmer et al., 2006; Milner, 2018). It is also important to structure the classroom so there are natural rewards and consequences that promote a sense of community and a mindset that we are all in this together and need to support each other. The overarching goal of the CEBM component is to foster a general classroom climate of productive and supportive behavior. To accomplish this, the CEBM component is organized into three complementary categories: behavioral context management; eliciting and reinforcing desired behavior; and behavior redirection.

Behavioral Context Management

Behavioral context management focuses on creating a predictable and supportive environment. The goal is to provide students with guides for their behavior to prevent problems, while establishing a framework and tools for helping students to navigate difficulties when they do arise (Sutherland et al., 2018). It is helpful to have rules that are few in number, can be applied to a broad range of circumstances, and are valued by students (Barbetta et al., 2005). Teachers should review rules and expectations at the beginning of each class or activity. This provides a transition point and allows the teacher to set the context and create a necessary shift in tone if the new activity is different in content, activity level, and self-regulatory demands as compared to the prior activity (Farmer et al., 2006).

For many students with SEN class does not start—it just kind of happens. Teachers can prevent this by having routines for classroom activities that make them predictable and easy to negotiate (Leinhardt et al., 1987; Emmer and Stough, 2001). Having classroom rituals and goals that add meaning, value, and special identity to an activity can foster engagement and promote a student's sense of belonging (Long et al., 2007). Further, when managing the classroom context, teachers should monitor their own behavior and model behaviors they would like to see from students. Teachers should be aware that their own behavior can create a context that prompts and escalates behavior problems and contributes to students' negative social reputations (van Acker et al., 1996; Hendrickx et al., 2016).

Evoking and Reinforcing Desired Behavior

It is common for teachers to think that a student knows what the expected behavior is and how to perform it, and are mystified when the student does not do it (Barbetta et al., 2005). Many students need goals, prompts, and reminders to initiate a behavior. When the behavior does occur, corresponding teacher responses (i.e., consequences) that reinforce (i.e., strengthen) the behavior are also needed so that it is more likely to occur in the future when antecedent circumstances are presented (Farmer et al., 2006). When students do not engage in the desired behavior, teachers need to be careful that they do not draw attention to it in a way that punishes the likelihood the student will try to do it in the future. Rather, teachers should focus on setting up the circumstances that support the future occurrence of the behavior and foster positive interactions with classmates without contributing to a poor reputation with peers. Teachers can provide behavior specific guidance in non-obtrusive ways (Simonsen et al., 2016; Gage et al., 2017) while structuring circumstances so that natural consequences reinforce the occurrence of the behavior (Long et al., 2007).

Behavior Redirection

Behavior redirection involves changing the flow of a pattern of behavior in stream as it occurs. When problem behavior begins to emerge, some teachers have a tendency to call out a student in a public manner that disrupts class, promotes a negative identity for the student that has social and behavioral consequences, and set ups a context for coercive interactions between the student and the teacher that contributes to sustained disengagement of the student from instruction and productive activities (Gunter et al., 1993; Shores et al., 1993; Hendrickx et al., 2016). The goal of behavior redirection is to prevent this from occurring by refocusing the student or class away from an undesired behavior to a neutral or desired behavior in a manner that minimally disrupts class and allows the student to remain engaged or to become involved in a productive alternative activity.

An important consideration for behavior redirection involves simultaneously keeping the class on track while changing the behavior of the student. Although strategies that single out a student should be avoided, verbal group redirection and acknowledgment of students meeting expectations can be an effective way to pull students back on task and to create a shared sense of community about appropriate behavior. This involves reminding the class about the expectation, recognizing students who are meeting the expectation, and acknowledging the whole class for meeting expectations once students change their behavior. Nonverbal individual redirection can be used to stop or reframe a behavior with eye contact, a descriptive physical gesture, or pointing toward a rule or some other cue that is in the room. Proximity management involves moving closer to the student, direct monitoring of their activities, and perhaps moving the student to another area where he or she is more likely to be productively engaged. Antiseptic bouncing involves being aware that the student is about to encounter a situation that is likely to result in difficulties and engaging the student in a different activity that takes the student away from the problem stimulus. This might involve asking a student who is becoming frustrated with an assignment to run an errand (e.g., take a book to the library) to break up the negative pattern and reset the activity in a more positive light once the student has returned and frustration has decreased. It might also be used to get a student away from an escalating situation that he or she might otherwise become involved in (e.g., sending the student to get help when two other students are arguing and beginning to fight). The goal is to keep the context manageable while giving the student a productive activity to prevent their engagement in problems.

A major consideration in redirection involves being reflective and understanding what is being communicated to the student. With redirection, students may perceive that teachers are just trying to “zing” her or him because they do not like them or are mad at them. It is critical for teachers to monitor their tone of voice and posture as well as the content of their words. Avoid arguments, but present the need for the redirection as being an important thing for the student to be able to do. When teachers make it clear they are following through on rules because they think that the student is important and because they want to ensure students learn to do what is best for the student, students can understand and value this. This is communicated through actions and fairness. Thus, it is important for teachers to understand what they feel, to manage their own emotions and behavior, and to redirect students in ways that focus on teaching and reinforcing behaviors that build the student's strengths. Students know when adults care.

Social Dynamics Management

The Social Dynamics Management (SDM) component of the BASE model centers on using knowledge of the classroom social system to harness the power of the peer group in the management of the instructional and behavioral context while fostering students' positive social roles and relationships. Classroom social dynamics refers to how classrooms are socially structured and how this structure effects and is affected by student interactions (Farmer et al., 2018c). Students coordinate their behaviors with each other, sort themselves into peer groups, create social hierarchies, and develop social roles (Adler and Adler, 1998; Ahn and Rodkin, 2014; Trach et al., 2018). Although social dynamics are peer driven, teachers can facilitate students' social experiences, opportunities, and roles (Gest et al., 2014; van den Berg and Stoltz, 2018). The goal of the SDM component is to create a classroom climate of peer support for academic engagement and productive behavior by fostering a positive social system to promote supportive social relationships for all students. The SDM component involves three categories: general social context management; monitoring and managing students' peer affiliations and group supports; and managing students' social roles and relationships.

General Social Context Management

When reviewing rules and expectations for academic activities and classroom behavior, it is helpful to review rules and expectations about social behavior and relationships. This should be brief and center on key words that signify expected behaviors and ways that students can get along and support each other. Depending on age level, terms such as sharing, being responsible for self and others, showing respect, being a good friend, and being a team player can key students into working with others to promote a productive and supportive classroom particularly when they are presented in a scaffolded manner to foster student autonomy (Baker et al., 2017; Bierman et al., 2017). This involves having expectations and concepts that are known by all, posted in visible places, valued by students, and serve as reminders about how to be supportive of and helpful to each other.

A critical aspect of SDM involves teachers' management of their own behavior (Farmer et al., 2006). By modeling desired social interactions, teachers can set the tone for how classmates view and respond to students (Shores and Wehby, 1999). Negative teacher-student relations are associated with peer difficulties (Hendrickx et al., 2016) and peer teacher support reputation contributes to students' academic and social outcomes (Hughes et al., 2014). For example, the peer relations of academically struggling students depend on whether classmates perceive that the teacher likes the student (van der Sande et al., 2017). When teachers develop positive relationships with socially struggling students and provide them with positive social opportunities, students tend to have a stronger sense of belonging and fewer behavioral difficulties (Farmer et al., 2010b; Gest et al., 2014; van den Berg and Stoltz, 2018). Therefore, it is critical for teachers to monitor their own interactions with struggling students and promote a classroom climate where peers can view them in a positive light (Trach et al., 2018).

The concept of attunement to students' social roles, reputations, and peer groups centers on teachers' awareness of the general classroom social ecology and students' placement in the peer system (Hamm et al., 2011a). When they are attuned to the ecology and students' relationships, teachers can use this information to support positive social opportunities, prevent peer experiences that contribute to behavioral difficulties, and promote injunctive peer group norms and a peer culture that reinforces academic engagement (Hamm et al., 2011b; Farmer et al., 2018a). Teacher attunement is associated with increased levels of students' sense of positive social-affective peer climate and enhances students' feelings of belonging (Hamm et al., 2011a; Norwalk et al., 2016). Yet, teachers are differentially attuned to youth who are perceived as aggressive by peers depending on whether they perceive a student has higher rates of internalizing, popularity, and friendliness features (lower levels of attunement) or higher levels of athleticism and attractiveness (higher levels of attunement: Dawes et al., 2017). Further, there is considerable variability across teachers' in terms of their attunement or awareness of students' peer group affiliations (Pearl et al., 2007). However, teachers' attunement increases significantly when they are taught about classroom social dynamics, are encouraged to observe students' social interactions in natural settings (i.e., cafeteria, hallway, playground), and are expected to keep logs about peer groups and students' social roles (Hamm et al., 2011a; Farmer et al., 2016a).

Monitoring and Managing the Classroom Social Hierarchy

Attunement to the classroom social system and monitoring dynamic relationships among students can be critical for fostering and maintaining inclusive classroom communities. In many classrooms, a peer social structure forms in which some students have higher status and peer influence than others (Adler and Adler, 1998; Ahn and Rodkin, 2014). When popularity and status is distributed hierarchically rather than in a decentralized and egalitarian manner, there is a greater tendency for bullying, social aggression, and enemy relationships across peer groups (Rodkin, 2011). Teachers can manage the social system and students' social opportunities to reduce hierarchies and promote peer ecologies where students are on more equal footing and perceive the social climate to be supportive and less threatening (Gest and Rodkin, 2011; Chen et al., 2015; Norwalk et al., 2016).

Monitoring and Managing Students' Peer Affiliations and Group Supports

Teachers can support students' positive peer relations. Propinquity (i.e., physical proximity) is a key factor that influences peer relationships. Students are more likely to develop friendships if they are in close proximity or have frequent contact with each other, and students tend to prefer to sit close to peers who are popular in the peer structure (Adler and Adler, 1998; van den Berg and Cillessen, 2015). Close proximity and frequent contact can also promote bullying, enemy relationships, or iatrogenic effects if students are on unequal footing or support problem behavior patterns in each other (Rodkin, 2011; Kornienko et al., 2018). Seating charts/proximity arrangements and grouping strategies are a primary means that teachers have available to impact students' peer opportunities and experiences. Emerging research suggests that when seating and grouping practices are carefully conducted and monitored with a focus on enhancing the behavior of struggling students, they produce positive social opportunities for the focal student without a negative impact on prosocial partner peers (Hektner et al., 2017; van den Berg and Stoltz, 2018). In addition, teachers need to monitor inter-group relationships to support positive interactions and prevent bullying relationships among youth who affiliate together. Likewise, there is a need to monitor intra-group relationships to support positive interactions and prevent enemy group relationships within and across classrooms (Rodkin, 2011; Farmer et al., 2018c).

Managing Students' Social Roles and Relationships

As teachers monitor and manage the general classroom social system and peer groups, it is necessary to keep a focus on individual students who have social risks and behavioral difficulties. To do this, it is necessary to identify and monitor patterns of social synchrony that support their behavior. Social synchrony involves interactional processes where the behavior of one person elicits and reinforces the behavior of the other person. This can occur through imitation, reciprocity, or complementarity (Farmer et al., 2018a). Teachers should identify specific peers who in some way prompt problem behaviors and/or reinforce such behaviors in the focal student (Farmer et al., 2016a). Once such students are identified, teachers can realign negative patterns by rearranging the context (i.e., change seating and grouping practices) and/or changing the behavior of supporting peers as well as the focal student (Farmer et al., 2018c). As part of this process, the focus should go beyond reducing problem behavior and identify ways to strengthen positive patterns. This can be done by changing the context, promoting more social opportunities with positive and supportive peers, and building from the student's strengths to promote new competencies. As part of this effort, it is important to be attuned to the student's social roles and reputations and to provide visible positive social opportunities to reframe negative social identities by helping peers view the student in a more positive light (Farmer et al., 2016a; Trach et al., 2018).

Interpersonal Competence Patterns and Subtypes of Socially Vulnerable Youth

Students with SEN and socially vulnerable students are a very heterogeneous group. When providing supports to foster social inclusion, it is important to avoid a “one size” fits all approach or to simply work one's way through a series of EBPs without considering the factors and processes that are contributing to an individual student's experiences. That said, it is possible to identify distinct subtypes of socially vulnerable youth, including youth with SEN, that have common social experiences and social supports needs that differentiate them from other students.

Person-oriented analysis (e.g., latent profile analysis, cluster analysis) that builds from a developmental systems conceptual framework is a valuable approach for identifying subtypes of socially vulnerable youth (Cairns and Cairns, 1994). Person-oriented approaches yield patterns or configurations of variables that operate as a “package” of developmental factors that contribute to youths' developmental trajectories and outcomes (Cairns, 2000; Bergman et al., 2009). Prior work with socially vulnerable students, including students with SEN have used teacher ratings of students' interpersonal competence in the classroom to identify distinct subtypes of youth (e.g., Cairns and Cairns, 1994; Rodkin et al., 2000; Farmer et al., 2003, 2011).

Throughout these and other studies, five configurations tend to emerge. High adaptive students (20–30% of all students; high teacher ratings across the academic, behavioral, and social domains) are generally well-integrated into the peer system, affiliate with other well-adapted classmates, and have average or high prominence (i.e., visibility) within the social hierarchy. Low-adaptive students (10–20% of students; low teacher ratings across the academic, social, and behavioral domains) tend to associate with peers who have adjustment problems and low status in the social hierarchy, are at increased risk of social isolation and, tend to be victims of bullying or bully-victims. Popular-aggressive students (10–15% of students: high teacher ratings for aggression, average to high ratings for popularity) to tend to be viewed by peers as cool and athletic, associate with other popular students, are perceived to bullies and leaders by their classmates, and tend to have elevated rates of being disliked but are unlikely to be socially isolated. Average students (30–45% of students: near the mean for each domain on teacher ratings) tend to be members of peer groups, near the class mean for social prominence and being liked by peers, and average rates of involvement in peer victimization. Passive students (10–20% of students: low average teacher ratings on academic and behavior domains with elevated ratings for shy-withdrawn and low ratings on social) tend to have elevated rates of social isolation or affiliate with passive classmates and they are at increased risk for being victimized by peers.

Although between 40 and 50% of students with SEN are identified in interpersonal risk configurations (i.e., popular-aggressive, passive, low-adaptive), the majority of students in these risk configurations are general education students (Farmer et al., 1999, 2011, 2019; Chen et al., 2019). In fact, in a recent sample of nearly 3,000 students across 26 middle schools, four times as many general education students (803) as students with SEN (197) were identified in risks configurations that are related to a range of social vulnerabilities including poor adjustment to the middle school environment, feelings of not belonging, involvement in peer victimization, and experiencing academic and behavioral difficulties (Chen et al., 2019). Accordingly, efforts to support the inclusion of socially vulnerable youth may be enhanced by focusing on students in these configurations regardless as to whether they are identified for SEN.

Using the BASE Model to Foster the Inclusion of Subtypes of Socially Vulnerable Youth

With brief teacher ratings, it is possible to screen for youth at the beginning of the school year who are at elevated risk for differential social difficulties. As indicated above, such efforts would identify three distinct types of students: passive, low-adaptive, and popular-aggressive. Students in each of these three configurations need supports to address their social needs in the classroom. But they have very different needs and, in cases where each subtype of student is in the classroom, they are likely to contribute to and exacerbate the difficulties of each other. Thus, it is beneficial for teachers to be attuned to these subtypes of youth and to provide differential supports while managing the broader social ecology.

For passive youth, their tendency is to keep a low profile, avoid situations and circumstances that draw any attention to them or their self-perceived weaknesses, and to try to stay away from classmates who will socially scapegoat them, tease them, physically bully them, or make them engage in things that they are not comfortable doing. For such students, teachers need to balance between providing them with social opportunities and supports to enhance their identity and role in the social system without putting them on the spot and actually contributing to their victimization. This means being cognizant of who they are comfortable with and who they are not comfortable with, knowing their strengths, knowing what aspects of their strengths and personality that they are comfortable showing others, and giving them the space to socially explore and develop their own identity. Being careful not to place them physically near or in working groups with peers who will bully or take advantage of them is critical. Also, engaging them in activities that are comfortable and that help them to be seen in a positive light can be important. But it must be paced and monitored. It is also important for the teacher to be aware of who the student affiliates with. Are these affiliations supportive of social engagement with others or are they synchronized in ways that constrain the student's social opportunities and, in some ways, supports their social difficulties? The goal is not to break up existing relationships or to choose students' friends, the goal is carefully monitor and expand passive students' social experiences and opportunities in ways that help them to develop relationships that are personally and developmentally meaningful to them. For passive students, there is generally not an issue with problem behavior but they may have a learning disability or some other characteristic that they are uncomfortable with or trying to hide. Without being invasive, it is important to get to know passive students and to understand their comforts and discomforts.

Low-adaptive youth are likely to struggle across the academic, behavioral, and social domains and they are likely to have difficulty regulating their behavior and understanding how their own behavior contributes to their difficulties. Therefore, such students typically need tier 2 or tier 3 adaptive supports to help them to develop new skills and competencies (Farmer et al., 2021). However, individually focused interventions alone are not likely to “fix” the student and it is necessary to have real world, in-stream context focused interventions that complement more direct and explicit instruction in social skills (Farmer et al., 2018a; Bierman and Sanders, 2021). Thus, being aware of the student's academic, behavioral, and social difficulties and how they support each other is important. Carefully managing the instructional context and pacing the student for success will be important along with understanding behavioral triggers and the peer dynamics and interactional patterns that contribute to the student's difficulties. Low-adaptive youth can be quick to explode and can become the target of peers who set them up for difficulties with the potential aim of getting them in trouble. It is imperative to carefully monitor their physical proximity and to surround them with peers who will not engage them in negative ways (van den Berg and Stoltz, 2018). It is also important to monitor these arrangements and to sometimes change them up from time-to-time as their relations with others can become strained.

It is critical to provide low-adaptive students with positive roles and experiences that build from their strengths and that gives them the opportunity to develop a new identity. Just as with academics, it is important to pace their social activities and interactions, build success, and carefully transition them into a new activity before something that was going well suddenly blows up and results in strained relations, poor reputations and identities, and coercive patterns of behavior with peers. The peer affiliations of low-adaptive students are likely to be many but short-lived, as they work themselves through the classroom until there are no classmates that are comfortable doing things with them. Pacing and creating social opportunities is important, but it is not possible to make classmates to like them or to want to do something with them. Therefore, monitoring, scaffolding, and supporting their interactions early in the school year can help to prevent long-term negative relationships. Low-adaptive students have very elevated rates of being involved in peer victimization as both a bully and a victim. Efforts to manage the social dynamics of bullying early in the school year may create a context that limits the types of coercive interchanges that typically characterize the social relationships of low adaptive youth.

In some ways, popular aggressive youth do not have social difficulties as much as they create social difficulties for others. They tend to be socially powerful and dominant leaders who use their power to manipulate the social relationships of others and they often set the tone for the behavior of many classmates, particularly the students they affiliate with (Farmer et al., 2003; Witvliet et al., 2010; Shi and Xie, 2012). Because of this power and how they use it against others, popular-aggressive youth can be highly disliked even though classmates may want to affiliate with them or be like them (Vaillancourt and Hymel, 2006; Farmer et al., 2011; Rodkin, 2011). Rather than having poor social skills, popular aggressive youth may be bistrategic controllers who competently employee aggressive and prosocial strategies as they selectively use distinct forms of aggression toward peers with different levels of status or popularity (Wurster and Xie, 2014). This means teachers must carefully monitor the interaction patterns of popular aggressive youth to determine if they are manipulating others and creating a hierarchical social system that is dominated by coercion and social struggles as students jockey for social position. Teachers themselves may be manipulated by popular-aggressive students and it is necessary to ensure they do not allow these students to create a culture that elicits and reinforces problem behavior in socially vulnerable classmates (Rodkin, 2011; Hoffman and Mueller, 2020). Thus, it is helpful for teachers to cultivate strong boundaries but positive relations with popular-aggressive students while creating opportunities for them to use their influence and leadership skills in positive and productive ways in the classroom (Shores and Wehby, 1999; Farmer et al., 2018a).

In conclusion, for all three subtypes, teachers need to be attuned to the overall dynamics of the classroom and to foster a context that is not hierarchical, that makes it safe for students to engage with others, and that rotates opportunities for all students to be in socially visible and desirable roles. But it is important to be cognizant that managing the general classroom peer ecology and social dynamics may have different leverage points and differential impact for the various subtypes. For passive students the focus is on providing a safe space where they can develop new experiences, relationships, roles, and identities that do not make it easy for them to be forgotten or scapegoated by others. For low-adaptive students, classroom context intervention efforts need to complement any individualized supports and training that they receiving related to the development of new social competencies and skills. This means continually monitoring their proximal context, reframing and redirecting difficult interchanges, providing them with opportunities for positive social experiences, and making the context predictable and one they feel they can successfully navigate rather than fight against. For popular-aggressive youth, it is necessary to guide their experiences toward positive and productive social roles and to help them use their social competencies and strengths in ways that reflect leadership in an egalitarian social system. In other words, social dynamics management means inconspicuously facilitating the social experiences of individuals and the capacity of contexts to foster a collective society where students find their own pathways to social identities, roles, and relationships that are meaningful to them and that prepare them for their futures. As the field moves forward, person-oriented approaches should be considered as one of many possible ways to help tailor intervention to the differential needs of subtypes of students who are socially vulnerable. Further, because student adaptation is correlated across multiple domains, the BASE model may help to enhance students' academic and behavioral adjustment as well as their social inclusion.

Author Contributions

TF wrote the manuscript, conceptualized the research, and directed the research. BS, KN, and MD co-wrote the manuscript and contributed to the research. C-CC contributed to the research and co-wrote parts of the manuscript. JH contributed to writing the manuscript, co-conceptualized the research, and co-directed the research. DL contributed to the writing of the manuscript and co-directed the research. AF contributed to the conceptualization, creation of the figures, and to the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Institute of Education Sciences (R305A040056; R305A160398; and R305A120812). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors' and do not reflect the views of the granting agency.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Adler, P. A., and Adler, P. (1998). Peer Power: Preadolescent Culture and Identity. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Ahn, H.-J., and Rodkin, P. C. (2014). Classroom-level predictors of the social status of aggression: friendship centralization, friendship density, teacher–student attunement, and gender. J. Educ. Psychol. 106, 1144–1155. doi: 10.1037/a0036091

Baker, A. R., Tzu-Jung, L., Chen, J., Paul, N., Anderson, R. C., and Nguyen-Jahiel, K. (2017). Effects of teacher framing on student engagement during collaborative reasoning discussions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 51, 253–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.08.007

Banks, J., McCoy, S., and Frawley, D. (2018). One of the gang? Peer relations among students with special educational needs in Irish mainstream primary schools. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 33, 396–411. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2017.1327397

Barbetta, P. M., Norona, K. L., and Bicard, D. F. (2005). Classroom behavior management: a dozen common mistakes and what to do instead. Prevent. Sch. Fail. 49, 11–19. doi: 10.3200/PSFL.49.3.11-19

Bergman, L. R., Andershed, H., and Andershed, A.-K. (2009). Types and continua in developmental psychopathology: problem behaviors in school and their relationship to later antisocial behavior. Dev. Psychopathol. 21, 975–992. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000522

Bierman, K. L., Greenberg, M. T., Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A., Lochman, J. E., and McMahon, R. J. (2017). Social and Emotional Skills Training for Children: The Fast Track Friendship Group Manual. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Bierman, K. L., and Sanders, M. T. (2021). Teaching explicit social-emotional skills with contextual supports for students with intensive intervention needs. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. doi: 10.1177/1063426620957623

Billingsley, G. M. (2016). Combating work refusal using research-based practices. Interv. Sch. Clin. 52, 12–16. doi: 10.1177/1053451216630289

Blake, J. J., Lund, E. M., Zhou, Q., Kwok, O. M., and Benz, M. R. (2012). National prevalence rates of bully victimization among students with disabilities in the United States. Sch. Psychol. Q. 27, 210–222. doi: 10.1037/spq0000008

Bossaert, G., de Boer, A. A., Frostad, P., Pijl, S. J., and Petry, K. (2015). Social participation of students with special educational needs in different educational systems. Irish Educ. Stud. 34, 43–54. doi: 10.1080/03323315.2015.1010703

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am. Psychol. 32, 513–531. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1996). “Foreward,” in Developmental Science, eds R. B. Cairns, G. H. Elder, and E. J. Costello (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), ix–xvii.

Cairns, R. B. (2000). “Developmental science: three audacious implications,” in Developmental Science and the Holistic Approach, eds L. R. Bergman, R. B. Cairns, L-G. Nilsson, and L. Nystedt (Mahwah, NJ: LEA), 49–62.

Cairns, R. B., and Cairns, B. D. (1994). Lifelines and Risks: Pathways of Youth in Our Time. New York, NY: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Chen, C.-C., Hamm, J. V., Farmer, T. W., Lambert, K., and Mehtaji, M. (2015). Exceptionality and peer victimization involvement in late childhood: subtypes, stability, and social marginalization. Remed. Special Educ. 36, 312–324. doi: 10.1177/0741932515579242

Chen, C. C.-C., Farmer, T. W., Hamm, J. V., Lee, D. L, Dawes, M., and Brooks, D. S. (2019). Emotional and behavioral risk configurations, students with disabilities, and perceptions of the middle school ecology. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 28, 180–192. doi: 10.1177/1063426619866829

Cullinan, D., Epstein, M. H., and Lloyd, J. W. (1983). Behavior Disorders of Children and Adolescents. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Danielsen, A. G., Wiium, N., Wilhelmsen, B. U., and Wold, B. (2010). Perceived support provided by teachers and classmates and students' self-reported academic initiative. J. Sch. Psychol. 48, 247–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2010.02.002

Dawes, M., Chen, C.-C., Zumbrunn, S. K., Mehtaji, M., Farmer, T. W., and Hamm, J. V. (2017). Teacher attunement to peer-nominated aggressors. Aggress. Behav. 43, 263–272. doi: 10.1002/ab.21686

Dawes, M., Farmer, T. W., Hamm, J. V., Lee, D., Norwalk, K., Sterrett, B., et al. (2020). Creating supportive contexts during the first year of middle school: impact of a developmentally responsive multi-component intervention. J. Youth Adolesc. 49, 1447–1463. doi: 10.1007/s10964-019-01156-2

Dweck, C. S., and Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychol. Rev. 95, 256–273. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

Emmer, E. T., and Stough, L. (2001). Classroom management: a critical part of educational psychology, with implications for teacher education. Educ. Psychol. 36, 103–112. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3602_5

Estell, D. B., Farmer, T. W., Irvin, M. J., Crowther, A., Akos, P., and Boudah, D. J. (2009a). Students with exceptionalities and the peer group context of bullying and victimization in late elementary school. J. Child Fam. Stud. 18, 136–150. doi: 10.1007/s10826-008-9214-1

Estell, D. B., Jones, M. H., Pearl, R., and van Acker, R. (2009b). Best friendships of students with and without learning disabilities across late elementary school. Except. Child. 76, 110–124. doi: 10.1177/001440290907600106

Estell, D. B., Jones, M. H., Pearl, R. A., van Acker, R., Farmer, T. W., and Rodkin, P. R. (2008). Peer groups, popularity, and social preference: trajectories of social functioning among students with and without learning disabilities. J. Learn. Disabil. 41, 5–14. doi: 10.1177/0022219407310993

Farmer, T. W. (2020). Reforming research to support culturally and ecologically responsive and developmentally meaningful practice in schools. Educ. Psychol. 55, 32–39.

Farmer, T. W., Bierman, K. L., Hall, C. M., Brooks, D. S., and Lee, D. L. (2021). Tiered systems of adaptive supports and the individualization of intervention: merging developmental cascades and correlated constraints perspectives. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. doi: 10.1177/1063426620957651

Farmer, T. W., Chen, C.-C., Hamm, J. V., Moates, M. M., Mehtaji, M., Lee, D., et al. (2016a). Supporting teachers' management of middle school social dynamics: the scouting report process. Interv. Sch. Clin. 52, 67–76. doi: 10.1177/1053451216636073

Farmer, T. W., Dawes, M., Alexander, Q., and Brooks, D. S. (2016b). “Challenges associated with applications and interventions: Correlated constraints, shadows of synchrony, and teacher/institutional factors that impact social change,” in Handbook of Social Influences in School Contexts: Social-emotional, Motivation, and Cognitive Outcomes, eds K. R. Wentzel and G. B. Ramani (New York, NY: Routledge), 423–435.

Farmer, T. W., Dawes, M., Hamm, J. V., Lee, D., Mehtaji, M., Hoffman, A. S., et al. (2018a). Classroom social dynamics management: why the invisible hand of the teacher matters for special education. Remed. Special Educ. 39, 177–192. doi: 10.1177/0741932517718359

Farmer, T. W., Estell, D. B., Bishop, J. L., O'Neal, K., and Cairns, B. D. (2003). Rejected bullies or popular leaders? The social relations of aggressive subtypes of rural African-American early adolescents. Dev. Psychol. 39, 992–1004.

Farmer, T. W., Goforth, J. B., Hives, J., Aaron, A., Hunter, F., and Sgmatto, A. (2006). Competence enhancement behavior management. Prevent. Sch. Fail. 50, 39–44. doi: 10.3200/PSFL.50.3.39-44

Farmer, T. W., Hall, C. M., Petrin, R. A., Hamm, J. V., and Dadisman, K. (2010a). Promoting teachers' awareness of social networks at the beginning of middle school. Sch. Psychol. Quart. 25, 94–106. doi: 10.1037/a0020147

Farmer, T. W., Hall, C. M., Weiss, M. P., Petrin, R. A., Meece, J. L., and Moohr, M. (2011). The school adjustment of rural adolescents with and without disabilities: variable and person-centered approaches. J. Child Fam. Stud. 20, 78–88. doi: 10.1007/s10826-010-9379-2

Farmer, T. W., Hamm, J. L., Petrin, R. A., Robertson, D. L., Murray, R. A., Meece, J. L., et al. (2010b). Creating supportive classroom contexts for academically and behaviorally at-risk youth during the transition to middle school: a strength-based perspective. Exceptionality 18, 94–106. doi: 10.1080/09362831003673192

Farmer, T. W., Hamm, J. V., Dawes, M., Barko-Alva, K., and Cross, J. R. (2019). Promoting inclusive communities in diverse classrooms: teacher attunement and social dynamics management. Educ. Psychol. 54, 286–305. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2019.1635020

Farmer, T. W., Hamm, J. V., Lee, D., Lane, K. L., Sutherland, K. S., Hall, C. M., et al. (2013). Conceptual foundations and components of a contextual intervention to promote student engagement during early adolescence: the supporting early adolescent learning and social success (SEALS) model. J. Educ. Psychol Consult. 23, 115–139. doi: 10.1080/10474412.2013.785181

Farmer, T. W., Hamm, J. V., Lee, D. L., Sterrett, B., Rizzo, K., and Hoffman, A. (2018b). Directed consultation and supported professionalism: promoting adaptive evidence-based practices in rural schools. Rural Special Educ. Quart. 37, 164–175. doi: 10.1177/8756870518781307

Farmer, T. W., Lane, K. L., Lee, D. L., Hamm, J. V., and Lambert, K. (2012). The social functions of antisocial behavior: considerations for school violence prevention strategies for students with disabilities. Behav. Disord. 37, 149–162. doi: 10.1177/019874291203700303

Farmer, T. W., Rodkin, P. C., Pearl, R., and van Acker, R. (1999). Teacher-assessed behavioral configurations, peer-assessments, and self-concepts of elementary students with mild disabilities. J. Special Educ. 33, 66–80. doi: 10.1177/002246699903300201

Farmer, T. W., Talbott, B., Dawes, M., Huber, H. B., Brooks, D. S., and Powers, E. (2018c). Social dynamics management: what is it and why is it important for intervention? J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 26, 1–10. doi: 10.1177/1063426617752139

Frederickson, N. L., and Furnham, A. F. (2004). Peer-assessed behavioral characteristics and sociometric rejection: differences between pupils who have moderate learning difficulties and their mainstream peers. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 74, 391–410. doi: 10.1348/0007099041552305

Gage, N. A., MacSuga-Gage, A. S., and Crews, E. (2017). Increasing teachers' use of behavior-specific praise using a multitiered system for professional development. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 19, 239–251. doi: 10.1177/1098300717693568

Gest, S. D., Madill, R. A., Zadzora, K. M., Miller, A. M., and Rodkin, P. C. (2014). Teacher management of elementary classroom social dynamics: associations with changes in student adjustment. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 22, 107–118. doi: 10.1177/1063426613512677

Gest, S. D., and Rodkin, P. C. (2011). Teaching practices and elementary classroom peer ecologies. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 32, 288–296. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2011.02.004