95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 04 December 2020

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 5 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.586962

This article is part of the Research Topic The Role of Teachers in Students’ Social Inclusion in the Classroom View all 16 articles

Hanna Beißert1,2*

Hanna Beißert1,2* Meike Bonefeld2,3

Meike Bonefeld2,3This study investigated pre-service teachers' evaluations, reactions, and interventions with regard to interethnic exclusion scenarios in Germany. More specifically, we focused on pre-service teachers (N = 145, 99 female, Mage= 21.34) in the role of observers of exclusion among students. Using hypothetical scenarios in which either a German or a Turkish boy was excluded by other children of his class, we assessed teachers' evaluations of this exclusion behavior. This included evaluating how likely teachers were to intervene in the situation and what they would specifically do. The aim of this research was to examine whether the origin of an excluded student represents a relevant category for teachers' evaluations of and reactions to social exclusion. In addition, we aimed to determine whether teachers include aspects related to group functioning in their considerations. The analyses demonstrated that teachers generally reject social exclusion, with female participants rejecting exclusion even more than male participants. Further, participants evaluated the exclusion of a Turkish protagonist as more reprehensible than the exclusion of a German protagonist. Regarding the likelihood of intervention, the origin of the excluded person was only relevant for male participants; i.e., they were less likely to intervene when the excluded person was German than when the excluded person was Turkish. Analyses of teachers' reasoning revealed their strong focus on inclusion as a social norm, especially in cases of interethnic exclusion. That is, when participants reasoned about the exclusion of the Turkish protagonist, they referred to the social norm of inclusion much more than when talking about the German protagonist. In contrast, aspects related to group functioning were scarcely of importance. In terms of the specific actions that participants would undertake as a reaction to the exclusion situation, no differences related to the origin of the excluded person were found. Hence, the origin of the excluded person factored into both the evaluation of the exclusion and the likelihood of intervention, but once the decision to intervene was made, there were no differences in the specific actions. The results are discussed in light of practical implications and teacher training as well as in terms of implications for future research.

The German educational system—as many others in Western Europe and the United States—has a student population with very heterogeneous cultural backgrounds. Germany has been an immigration country for at least half a century (Oltmer, 2017). As a result, the general population and, thus, the student body are characterized by considerable cultural diversity. Unfortunately, Germany has not been overly successful in achieving integration and educational equality so far. Even though some positive development has been noted in recent years, research has extensively demonstrated that students from ethnic minorities experience various disadvantages in the educational system (Müller and Ehmke, 2016; Weis et al., 2019). For instance, they are overrepresented in lower school tracks and underrepresented in higher school tracks (Baumert and Schümer, 2002; Kristen and Granato, 2007); they drop out of school more often (Rumberger, 1995); they are recommended for lower school tracks more often (Glock et al., 2015), and their academic achievement tends to be lower than that of their native peers (Walter, 2009; Klieme et al., 2010). While a seminal body of research has focused on achievement-related disparities, little is known about the social situation of immigrants in the educational system. For instance, do students from ethnic minorities face more social exclusion in peer interactions than their native peers? Are they socially well integrated into their peer group? And what roles do teachers play in this context?

While the study of interethnic friendships has a somewhat longer tradition (Reinders, 2004; Schacht et al., 2014), in recent years, research has started to investigate exclusion behavior among students in the context of interethnic group processes. As a result, research from Germany has recurrently shown that students are much more likely to choose peers of the same race as a friend than peers from another race (e.g., Kalter and Kruse, 2015; Schachner et al., 2016). This holds especially for close friendships (Winkler et al., 2011) and is particularly evident for children of Turkish origin (Schachner et al., 2016; Carol and Leszczensky, 2019). In addition, it has been shown that social exclusion often happens based on group memberships such as race or ethnicity (Killen and Stangor, 2001; Killen et al., 2010; Abrams and Killen, 2014; Hitti and Killen, 2015). Additionally, minority groups are especially likely to be confronted with stereotypical mindsets and behavior, which can also result in the exclusion of students from ethnic minorities (Killen et al., 2013). In line with these findings, belonging to an ethnic minority has been identified as a risk factor for exclusion among peers. Plenty and Jonsson (2017), for instance, investigated social exclusion among adolescents and found that students from ethnic minorities were rejected more than majority youth.

What remains unclear is the role of teachers in this context. In general, teachers can have a strong impact on their students' attitudes and behavior. For instance, they establish rules that indicate which behaviors are acceptable in class and which are not. They are important role models for their students, especially when it comes to ethnic topics (Evans, 1992). Thus, how they interact with their students is particularly important. With the way teachers behave, they transmit their attitudes and beliefs (Muntoni and Retelsdorf, 2020). Through their behavior they transmit both explicit and implicit messages about their attitudes related to the importance of inclusion and diversity in schools (Cooley et al., 2016). In this way, teachers' reactions and responses to interethnic social exclusion can have an impact on their students' attitudes and behavior. For instance, in a study that Verkuyten and Thijs (2002b) conducted in the Netherlands with students aged between 10 and 13 years old, youth from ethnic minorities reported less exclusion and dismissive behavior when they believed that they could confide in their teacher and when they believed that their teacher would take action if they told him or her that they had been treated unfairly. Thus, it can be assumed that teachers' commitment to addressing intergroup exclusion issues and their engagement in explicit discussions about the importance of inclusion have positive effects on their students' intergroup attitudes and behavioral tendencies related to inclusion or exclusion (Cooley et al., 2016). That is, the way teachers react to interethnic exclusion situations forms and impacts their students' attitudes and behavior in a subtle way. In this way, teachers can contribute to students' moral development and help them understand moral norms such as equality, fairness, and inclusion (Cooley et al., 2016). As teachers play such an important role in their class's social system, especially in the context of interethnic group processes, and as their behaviors can contribute to positive or negative intergroup dynamics, research is needed on teachers' responses to interethnic exclusion (i.e., social exclusion including students from different ethnicities) in order to better understand the social climate in classrooms.

Although there is only little research on teachers' reactions to exclusion, there are some studies that focus on teachers' responses to bullying which include exclusion behavior (Yoon and Kerber, 2003; Bauman and Del Rio, 2006; Shur, 2006). However, we are not aware of any research that has examined teachers' reactions to interethnic exclusion among students. Therefore, many open questions remain: How do teachers evaluate interethnic exclusion and how do they deal with it? Are their evaluations of exclusion biased depending on the ethnic origin of the excluded person? Do such biases influence their behavioral tendencies?

A considerable part of a teacher's work involves evaluating students. In the context of achievement-related evaluations, it has been shown that teachers' judgments are often biased by irrelevant aspects related to their students (Glock, 2016; Holder and Kessels, 2017). Although teachers use relevant information about their students, their judgments or evaluations are often biased by information that, in fact, should be irrelevant for the respective judgment, such as a student's ethnicity (McCombs and Gay, 1988; Parks and Kennedy, 2007; Bonefeld et al., 2017). This has been shown for pre-service teachers as well as for in-service teachers (Glock et al., 2015; Bonefeld and Dickhäuser, 2018; Bonefeld and Karst, 2020; Bonefeld et al., 2020). Whereas, teachers' biased evaluations have been intensively investigated in the context of grading or other achievement-related aspects, it remains unclear whether ethnic origin is also relevant for teachers' judgments about social interactions, particularly in the context of social exclusion. Little is known about how teachers perceive, evaluate, and react to interethnic exclusion. As reactions to social exclusion might already be an important topic in teacher training, the current study investigates pre-service teachers' reactions to interethnic exclusion scenarios in Germany.

Although teachers' evaluations of their students are affected by the characteristics of the students, their own characteristics can also be important in this context (Südkamp et al., 2017). For example, a teacher's gender might be a relevant characteristic which has an impact on the evaluation of social exclusion. Previous research has shown that females (children, adolescents, and adults) tend to oppose exclusion more strongly than males (e.g., Killen and Stangor, 2001; Horn, 2003; Beißert et al., 2019). One reason for this could be gender-specific socialization. Typically, girls' socialization has a stronger focus on harmony, caring behavior, and the avoidance of interpersonal struggles (Cross and Madson, 1997; Zahn-Waxler, 2000). Further, parents have been shown to address the harmful consequences of aggressive behavior much more in the education of girls than that of boys, leading to enhanced empathy in girls compared to boys (Smetana, 1989). Based on these gender-specific socialization aspects, females might feel a stronger need to prevent exclusion and promote inclusion and, thus, might also be more likely to intervene in exclusion situations. In the current study, we want to examine whether these gender effects can also be found in teachers' reactions to social exclusion among students.

Further, a teacher's own immigration history might be particularly relevant for their evaluation of interethnic social exclusion. Prior research on teachers' attitudes has shown that teachers' own immigration history influences their evaluations regarding students of different ethnicities (Kleen et al., 2019). In terms of social exclusion, having an immigration history in the family might, for instance, enhance a teacher's empathy with an excluded student who is from an ethnic minority. Thus, research on interethnic exclusion should always take into account the participants' own immigration history.

It is in the nature of humans to organize the social world into categories (Brewer, 2001). Just as we classify plants and animals into taxonomies based on their typical characteristics, we classify people into groups. Categories help us to simplify and organize our complex world. This process of classifying people into groups is called social categorization. Whenever we perform such categorizations, we also differentiate between ingroup (a group to which we psychologically identify as being a member) and outgroup (a group with which we do not identify). According to social identity theory, people define their social identity based on group memberships (Tajfel, 1978; Tajfel and Turner, 1979). Against this background and with a view to achieving a positive social identity, people desire to identify with and belong to social groups seen as superior to others (Tajfel, 1982). Group members compare their ingroup to outgroups and positively define their ingroup to maintain their status (Tajfel, 1974; Tajfel and Turner, 1986). This preference for the ingroup is called ingroup favoritism or ingroup bias; it results in preferences that favor or promote the ingroup's status, often at the expense of other groups (Turner et al., 1979). Given this general tendency to prefer ingroup members and depreciate outgroup members, it is not surprising that exclusion is often based on group memberships such as race or ethnicity, and that ingroup-outgroup processes affect the evaluation of exclusion situations (Dovidio et al., 2005; Hitti et al., 2011; Killen et al., 2013). Furthermore, when children and adolescents have to justify exclusion, they often cite reasons related to smooth group functioning (Hitti et al., 2011; Mulvey, 2016). Hence, it is not only “raw” ingroup favoritism that promotes the exclusion of outgroup members. In many instances, children and adolescents expect outgroup members to have a negative impact on the group functioning within their ingroup.

There is extensive research demonstrating the role of ingroup-outgroup processes and group functioning for exclusion among children and adolescents. However, it remains unclear whether teachers' evaluations of student exclusion are also affected by intergroup processes such as ingroup favoritism. Furthermore, it is unclear whether teachers, as observers, also consider group functioning aspects when evaluating interethnic social exclusion among their students.

The current study investigated German pre-service teachers' reactions to interethnic exclusion scenarios. More precisely, we focused on pre-service teachers in the role of observers of exclusion among students and examined their evaluations of these situations as well as their hypothetical interventions. The study aimed to shed light on the question of whether teachers' evaluations of interethnic exclusion situations are biased by ingroup-outgroup processes based on ethnicity. More specifically, we analyzed whether the ethnic origin of an excluded student represents a relevant category for teachers' evaluations and reactions, and whether they include group functioning aspects in their considerations. In our study, we focused on students with Turkish roots because they are the largest ethnic minority in Germany (DESTATIS, 2016). Further, Turkish students are a very important group because research has shown that negative attitudes about Turkish people are widespread in Germany (Glock et al., 2013; Glock and Karbach, 2015; Bonefeld and Karst, 2020). In order to examine the aforementioned issues, the current study used hypothetical exclusion scenarios in which the excluded protagonist was either a Turkish student or a German student. We assessed how pre-service teachers evaluated the exclusion scenario as well as how likely they would intervene in such a situation and how they would specifically react.

Given that the need to belong and be accepted by others is a fundamental human need (Baumeister and Leary, 1995), it is not surprising that children, adolescents (Killen and Rutland, 2011), and adults (Beißert et al., 2019) typically reject exclusion. Thus, we expected a strong general tendency to reject exclusion (right-skewed distribution) across both protagonists. However, given the importance of intergroup processes—more precisely ingroup favoritism—in social situations, we assumed that the participants would evaluate the exclusion of a German protagonist (ingroup member) as more reprehensible than the exclusion of a Turkish protagonist (outgroup member). Further, based on prior research with children and adolescents as well as on considerations related to gender-specific socialization, we expected females to generally reject exclusion more strongly—independently of the origin of the protagonist.

It was an open question as to whether participants would differ in their reactions to the exclusion scenario depending on the respective protagonist (German vs. Turkish). For instance, were they more or less likely to intervene in situations with one protagonist or with the other? And when they decided to intervene or not, would their considerations differ depending on the excluded person?

Our ultimate objective was to explore how exactly pre-service teachers would react to the exclusion situation and whether their specific actions would differ based on the origin of the excluded protagonist.

The study included 145 pre-service teachers (99 female, Mage = 21.34, SD = 2.13) from various school tracks who were students at a university in the southwest of Germany. Within this sample, 58% of the participants had completed a school teaching internship as a mandatory part of their program. Sixteen of the participants had an immigration history in their family (i.e., at least one parent was born in a country other than Germany), but all participants were born in Germany. Three participants were excluded from the analyses because they had a Turkish background and, thus, the outgroup manipulation in the scenarios would not have worked for them. Participation was voluntary and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The study was conducted in a research lab at the participants' university. The participants were recruited personally on campus. Additionally, flyers and posters advertising the study were distributed on campus. After arriving in the lab, the participants were seated in front of a computer screen. They were informed that they were participating in a study about social issues in school. Before the assessments started, they were informed of their data protection rights and learned that participation in the study was anonymous and voluntary, and that there were no disadvantages if they decided not to participate or leave the study early without completing it. Participants had to confirm that they understood the information and were willing to participate in the study. The study took approximately 10 min per person, and the participants were given a cupcake as an incentive for participation.

The participants completed a computer-based survey including a questionnaire collecting demographical information and were then presented with a hypothetical scenario in which one student was excluded from a learning group by his classmates. The excluded protagonist had either a typical German or a typical Turkish name. The names used in the scenario had been pretested in a former study by Bonefeld and Dickhäuser (2018). The exact wording of the scenario was as follows: “While packing up after class (grade 71), you observe some students making an appointment to study together. Max/Murat would like to join the learning group. The other students tell him that he can't join.”

The study used a between-subjects design, and the participants were randomly assigned to the experimental conditions (71 were assigned the version with the German protagonist, 74 the version with the Turkish protagonist).

The participants' evaluations of the exclusion scenario were assessed with a scale consisting of three items on a seven-point Likert-type scale. The participants were asked to indicate how (1) not okay/okay, (2) unfair/fair, and (3) unjustifiable/justifiable they evaluated the scenario. A score was created indicating a participant's evaluation of the exclusion based on these three items (Cronbach's alpha = 0.84). High numbers indicate high acceptability of exclusion; low numbers indicate strong rejection of exclusion.

Additionally, participants were asked how likely it was that they would intervene in the situation if it happened in their class. This was also assessed using a seven-point Likert-type scale (very unlikely to very likely). Further, they were asked to justify their decision and to indicate what specifically they would have done (open-ended questions).

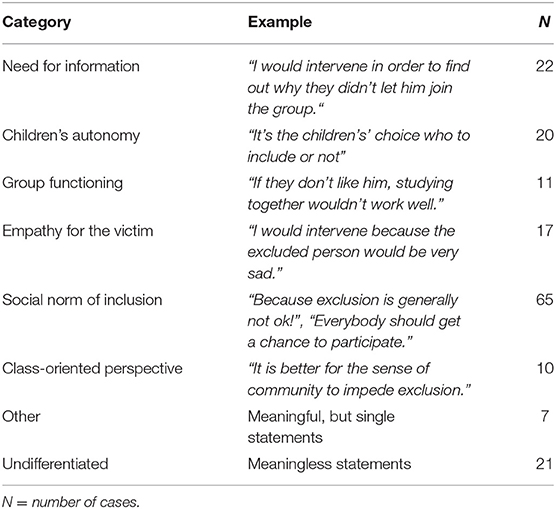

The coding systems for the open-ended questions (justification of likelihood of intervention, specific actions) were inductively developed from the surveys themselves (see Tables 1, 2 for an overview and examples). To prevent a loss of important information, coders were allowed to code up to three relevant justifications for each statement (if necessary). Coding was completed by two independent coders. On the basis of 25% of the interviews, interrater reliability was high, with Cohen's kappa = 0.85 for the justifications of the likelihood of intervention, and kappa = 0.95 for the specific actions. We included the most-used categories (all of which were used by more than 10% of the participants) in the analyses here.

Table 1. Coding system for justifications of likelihood of intervention and frequencies for each category.

Univariate ANOVAs were used to test for differences in the evaluation of exclusion and the likelihood of intervention between the two different experimental conditions (German protagonist vs. Turkish protagonist). Repeated-measures ANOVAs were used for analyses on the justifications of the decisions and on the specific actions. In order to test for differences between male and female teachers, the variable gender was included in all analyses. As participants' own ethnic background might influence their responses and reactions, their family immigration history was included in all analyses as a control variable.

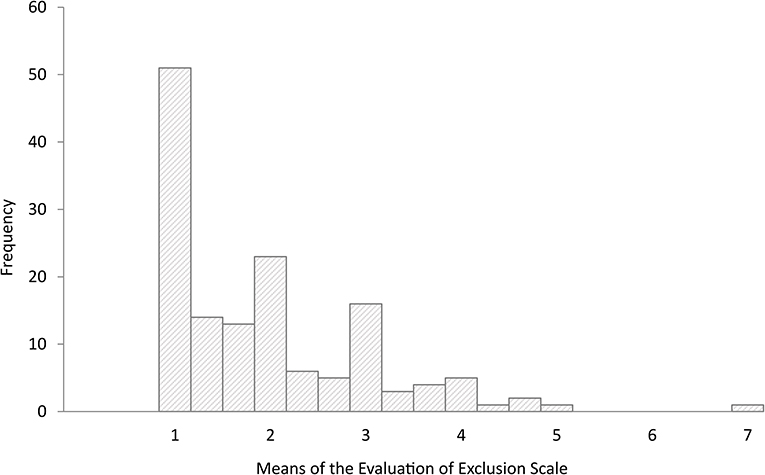

As expected, we found a general tendency to reject exclusion across both protagonists, i.e., a right-skewed distribution on the evaluation scale with a skewness of 1.43 (SE = 0.20), a mean of 1.95 (SD = 1.08), mode = 1.0, and median = 1.67. See Figure 1, for the distribution of the means of the evaluation scale.

Figure 1. Distribution of the means of the evaluation scale. Note: The scale was created by combining the three evaluation items (not okay/okay, unfair/fair, unjustifiable/justifiable) indicating a participant's evaluation of the exclusion. High numbers indicate high acceptability of exclusion; low numbers indicate strong rejection of exclusion.

In order to test for differences in the evaluation of exclusion between the two protagonists, a 2 (protagonist: German, Turkish) ×2 (gender: male, female) univariate ANOVA was conducted with the participants' immigration history as a covariate. The results revealed a main effect of the protagonist, F(1, 141) = 19.72, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.12; see Figure 2. In contrast to our expectations, the participants evaluated the exclusion of the Turkish protagonist as more reprehensible (M = 1.64, SD = 0.78) than the exclusion of the German protagonist (M = 2.28, SD = 1.24). Further, as expected, a main effect of the participants' gender was found, F(1, 141) = 14.71, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.10, revealing that female participants rejected exclusion generally more strongly (M = 1.76, SD = 0.94) than male participants (M = 2.36, SD = 1.23). No effects of participants' immigration history were found. No interaction effects were found.

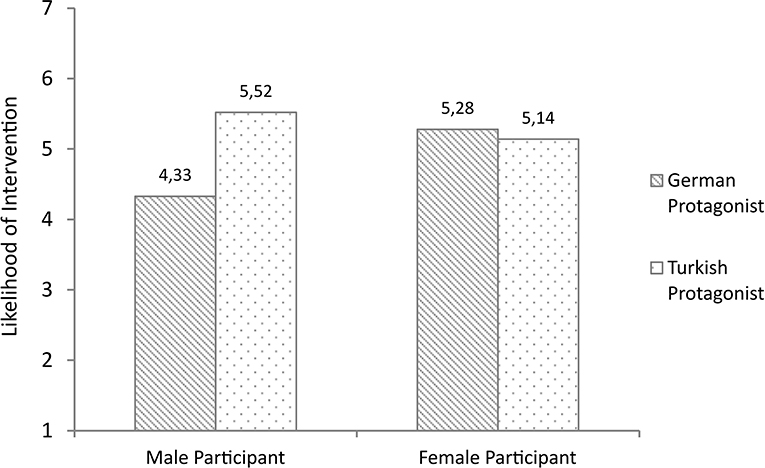

Figure 2. Likelihood of intervention as a function of participants' gender and origin of the protagonist. Note: High numbers indicate a high likelihood to intervene into the situation.

In a next step, we analyzed differences in the participants' likelihood to intervene in such a situation by conducting a 2 (protagonist: German, Turkish) ×2 (gender: male, female) univariate ANOVA with participants' immigration history as a covariate. No main effects were revealed. However, a significant interaction of participants' gender and the protagonist was revealed, F(1, 140) = 4.39, p = 0.038, ηp2 = 0.03. Specifically, male participants were less likely to intervene in the condition with the German protagonist than in the condition with the Turkish protagonist (p = 0.024), whereas female participants did not differ between the two conditions (p = 0.710); see Figure 2.

Analyses were conducted on the participants' reasoning based on the proportional use of the targeted justification codes (all of which were used by more than 10% of the participants). The resulting codes were: “social norm of inclusion,” “empathy for the victim,” “need for information,” and “children's autonomy.” ANOVAs provide appropriate frameworks for performing repeated-measures reasoning analyses because they are robust to the problem of empty cells, whereas other data analytical procedures require cumbersome data manipulation to adjust for empty cells [see Posada and Wainryb (2008), for a more extensive explanation and justification of this data analytical approach].

In order to test for differences in participants' justifications based on the origin of the protagonist, a 2 (protagonist: German, Turkish) ×4 (justification: social norm of inclusion, empathy for the victim, need for information, children's autonomy,) ×2 (gender: male, female) ANOVA was run with repeated measures on the factor “justification” and with participants' immigration history as a covariate.

We found a main effect of justification F(2.50, 342.96) = 12.23, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08. The Greenhouse-Geisser adjustment method was used to correct violations of sphericity. The analyses revealed that justifications referring to the social norm of inclusion were used much more frequently than any other type of justification (ps ≤ 0.001). This main effect was qualified by a significant interaction effect of justification and the protagonist, F(2.50, 342.96) = 3.02, p = 0.039, ηp2 = 0.02. This meant that this justification was used more often than any of the other types of justifications only when referring to the Turkish protagonist, p < 0.001. When the participants referred to the German protagonist, there were no differences in the use of justifications. Additionally, comparisons revealed that this type of justification was used considerably more often when referring to the Turkish protagonist (M = 0.50, SD = 0.48), than when referring to the German protagonist (M = 0.31, SD = 0.44), p = 0.018.

Further, there was an interaction effect of gender and justification, F(2.50, 342.96) = 6.09, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.04, revealing that female participants (M = 0.48, SD = 0.47) used justifications referring to the social norm of inclusion much more often than male participants (M = 0.24, SD = 0.42), p = 0.002). See Table 3 for all means and standard deviations. No effects of the participants' immigration history were found.

We also asked the participants what exactly they would have done if they had intervened in the exclusion situation. To analyze these specific interventions, we conducted analyses on the proportional use of the mentioned actions (all of which were referred to by more than 10% of the participants). The resulting categories were “ask for reasons,” “help to find inclusion-oriented solution,” “explain norm of inclusion,” “find alternative solution for excluded student,” and “class-based intervention.” In order to test for differences in the participants' specific actions, a 2 (protagonist: German, Turkish) ×5 (action: ask for reasons, help to find inclusion-oriented solution, explain norm of inclusion, find alternative solution for excluded student, class-based intervention) ×2 (gender: male, female) ANOVA was run with repeated measures on the factor “action” and with the participants' immigration history as a covariate.

There was a main effect of action, F(3.28, 449.22) = 17.78, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.12. The Greenhouse-Geisser adjustment method was used to correct violations of sphericity. More specifically, participants stated they would ask for reasons (M = 0.37, SD = 0.38) and try to find an alternative solution for the excluded student (M = 0.24, SD = 0.38) more than they would help to find an inclusion-oriented solution (M = 0.13, SD = 0.28), explain the norm of inclusion (M = 0.06, SD = 0.19), or aim for a class-based intervention (M = 0.08, SD = 0.26), all ps < 0.05.

There were neither main effects of the protagonist or of the participants' immigration history nor any interaction effects.

The current study investigated pre-service teachers' reactions to interethnic exclusion scenarios in Germany. More specifically, we focused on pre-service teachers in the role of observers of exclusion among students. Using hypothetical scenarios in which either a German or a Turkish boy was excluded by other children in his class, we assessed teachers' evaluations of this exclusion behavior as well as the likelihood that they would intervene in the situation, and the specific action they would take. The aim of this research was to examine whether the origin of an excluded student represents a relevant category for teachers when responding to social exclusion.

Generally and regardless of the origin of the protagonists, we found a strong tendency to reject exclusion, with female participants rejecting exclusion even more strongly than male participants. However, the origin of the excluded student represented a relevant category for participants' evaluations of the exclusion scenario. Interestingly, the effect confounded our expectations: Contrary to our anticipations, the participants evaluated the exclusion of a Turkish protagonist as more reprehensible than the exclusion of a German protagonist. Therefore, origin affected teachers' evaluations, but in contrast to our expectations, not in the sense of ingroup bias (i.e., the tendency to favor ingroup members over outgroup members).

Regarding the likelihood of intervention, the origin of the excluded person was only relevant for male participants. They were less likely to intervene when the excluded person was German than when the excluded person was Turkish. For female participants, there was no difference; i.e., they were very likely to intervene independently of the origin of the protagonist.

The origin of the protagonist was also relevant for teachers' justifications of their decisions to intervene or not. Namely, an interesting interaction was found between the origin of the excluded student and the type of justification. When the participants reasoned about the exclusion of the Turkish protagonist, they referred to a general social norm of inclusion much more than when talking about the German protagonist. In addition, when speaking about the Turkish protagonist, they referred to the social norm of inclusion more often than to any other reason. In other words, the general norm of social inclusion seems to be particularly salient when ethnic minorities are involved and an important issue for teachers. Interestingly, female participants named the social norm of inclusion even more often than male participants–for both protagonist groups.

In line with our expectations, female pre-service teachers seem to value social inclusion even more than their male counterparts. They focus more strongly on social inclusion as a general norm, reject exclusion more strongly, and are very likely to intervene in exclusion situations in order to promote inclusion. Extending previous research that typically focused on exclusion in symmetrical relationships between peers, the current data showed that these gender differences also hold for pre-service teachers as observers of student exclusion. As females have been found to be more inclusive than males at various ages and in very different kinds of relationships or situations, this seems to be something deeply rooted in the minds of girls and women. This might indicate that these differences are based on gender-specific socialization. As a consequence, a possible way of enhancing males' inclusivity would be a stronger focus on inclusion and community during their early education and socialization.

In terms of the specific actions potentially taken by participants as a reaction to the exclusion situation, we found no differences related to the origin of the excluded person. Regardless of the origin, the vast majority of the participants would have asked the group to name the reasons why it was excluding the student, and also a large number of the participants would have tried to find an inclusion-oriented solution or an alternative solution for the excluded student. Thus, origin mattered for both the evaluation of the exclusion situation and the likelihood of intervention, but once the decision to intervene was made, there were no differences in the specific actions.

All in all, we found evidence that the origin of an excluded person is a relevant category for teachers' reactions to social exclusion. The origin of the excluded student affected teachers' evaluations of the exclusion scenario and, for males, also their likelihood to intervene or not. Additionally, their underlying considerations differed based on the origin of the excluded person. However, although these differences were significant, it is important to emphasize that our participants predominantly rejected exclusion for both protagonists, and the differences were not very big. Further, the teachers in our study did not exhibit ingroup bias. In contrast, they evaluated the exclusion of the student from an ethnic minority (outgroup member) as even more reprehensible than the exclusion of a German protagonist and referred to the value of social inclusion more often when talking about the minority student.

We found it highly encouraging that pre-service teachers generally reject interethnic exclusion and show no discrimination of children with Turkish origin. Moreover, pre-service teachers reject the exclusion of a Turkish protagonist even more than for a German student. This could be due to the official educational mission and protection mandates regarding minorities, which include the integration of ethnic minorities at school (Ungern-Sternberg, 2008). Given the huge heterogeneity in German schools, this mandate might be particularly salient in teachers' minds. This is also in line with the finding that our participants referred to the general norm of inclusion much more often when reasoning about the exclusion of a Turkish student. Further, this might indicate that pre-service teachers are sensitive to the fact that exclusion based on origin is an issue in schools, and that it is important to promote inclusion as a general norm in class. Due to the strong human need to belong, social exclusion can have severe implications for health and well-being (Buhs and Ladd, 2001; Rutland and Killen, 2015). For students from ethnic minorities, exclusion can have a particularly strong impact (Ward et al., 2001; Verkuyten and Thijs, 2002a). This makes it even worse that social exclusion among children and adolescents is often based on group memberships such as ethnicity (Killen and Stangor, 2001; Abrams and Killen, 2014). Thus, it is very promising that the pre-service teachers in our study attached great importance to the norm of social inclusion in class and did not succumb to ingroup bias.

However, the question arises: What makes interethnic social exclusion different from other issues that teachers have to evaluate or react to? As described above, in Germany, children with an immigration history are disadvantaged in educational settings in many ways. Especially when performing achievement-related evaluations (e.g., grading), teachers seem to be biased by their students' ethnic origin (Bonefeld et al., 2017; Bonefeld and Dickhäuser, 2018). One possible explanation for this discrepancy between our findings regarding social exclusion and the findings of many prior studies on teacher bias in achievement evaluations is provided by the dual process models of information processing and judgment formation (Brewer, 1988; Fiske and Neuberg, 1990; Fiske et al., 1999). Such models assume that we typically process information via two routes when we make judgments about other persons: a more automatic route where we rely on obvious—but often irrelevant—cues such as social categories (in our context, for instance, the ethnic origin of a student) and a more controlled, integrating route where we review all information that might be relevant for the judgment. The automatic route is typically used for judgments related to routine tasks whereas the controlled route is typically used for non-routine activities or judgments that are considered as particularly important. In prior research it was often assumed that achievement-related judgments are, to a great extent, made via the automatized route (Glock and Krolak-Schwerdt, 2013). This is plausible because achievement-related judgments represent routine tasks in teachers' daily lives. Dealing with (interethnic) social exclusion in class, on the other hand, is something less routine and an issue that we would expect to be considered as very important given the severe consequences it can have. When integrating all relevant information in order to make a judgment using the controlled route, teachers make more accurate judgments (i.e., judgments that are less biased by social categories such as ethnicity). Therefore, this could be one reason why social exclusion is less affected by the ethnic origin of students.

Another interesting finding of this study is that group functioning aspects played only a very minor role in pre-service teachers' considerations. Previous research with children and adolescents has shown group functioning to be an important justification for interethnic exclusion (Hitti et al., 2011; Mulvey, 2016). On the other hand, in our study, only a very small number of participants (8%) mentioned aspects related to group functioning. However, teachers might not have had enough information to name group functioning as an underlying motive in the presented situations. Many of the participants stated that they would intervene in order to ask for reasons. This indicates that pre-service teachers do not want to judge the situation superficially. They want to understand the underlying motives why the student is excluded. Of course, exclusion is always harmful for the excluded person. However, some reasons might be more appropriate justifications for excluding a certain person in a certain situation than others. Smooth group functioning might be one of the more appropriate reasons to justify social exclusion. Also, prior negative behavior of a student or interpersonal struggles might be rather valid justifications for excluding someone from a certain situation, without representing a strong moral transgression in contrast to exclusion solely based on someone's origin. Many participants in our study stated explicitly that it was hard for them to evaluate the scenario and to say whether they would intervene or not, because they were provided with so little background information regarding the situation or the relationship of the protagonists. Obviously, teachers want to understand the situation more completely when making decisions about how to react appropriately. In real life, teachers typically have more knowledge about their students and know who is friend with whom, etc. This might limit the external validity of our results. However, our approach has clear benefits: The experimental approach allowed us to analyze the sole effect of the protagonists' origin, isolated from other aspects which in real life might bias teachers' evaluations or reactions. Additionally, the situations described in our scenarios are not too disconnected from everyday life. Although teachers typically know their students, they do not have knowledge about all things that happen in class and are often supposed to make instant evaluations or decisions without having additional information. However, further research should address this issue and systematically vary the background information about the situation and the excluded student.

One important restriction of our study is that our data were collected using hypothetical scenarios and self-reports which might be biased by social desirability. However, Turiel (2008) demonstrated that reasoning and evaluations by children and adolescents in hypothetical situations correspond to those in real-life situations and thus are comparable. In addition, research using a similar paradigm as the current study demonstrated that, for children, self-reports correspond with actual behavior (Mulvey et al., 2018). However, this has not been proven for adults yet. Therefore, it would be of interest for future research to connect self-report data with behavioral observations in order to determine the extent to which self-reports correspond with actual behavior. As social desirability is especially relevant regarding explicit measures of intergroup attitudes (Nesdale and Durkin, 1998; Rutland et al., 2005), it would also be interesting to see whether implicit measures of intergroup attitudes reveal different results.

Moreover, future research should also focus on in-service teachers because they already work with students and have an impact on their development and behavior. It would be interesting to see whether studies with in-service teachers replicate our findings or lead to different results. However, both research with pre-service teachers and in-service teachers can produce essential findings and have important implications for teacher training with the objective of placing well-trained staff in schools right from the start of their careers.

Further, it would be very interesting to compare different contexts of exclusion or to focus on additional ethnicities. Prior research has demonstrated that the context of exclusion (e.g., leisure time activities vs. achievement-related activities) affects judgments about peer exclusion (Horn, 2003; Tenenbaum et al., 2018; Beißert et al., 2019). But does this also hold for teachers when they evaluate social exclusion among students? And will the current findings be replicated for protagonists from other ethnicities or with a different immigration status, such as refugees? Are aspects related to group functioning possibly more relevant in some contexts or for some target persons than for others? Future studies should address these issues and systematically investigate teachers' reactions to social exclusion and include different methodical paradigms, different types of teachers, different target groups, and different contexts.

Nevertheless, in summary, our study revealed important findings regarding teachers' reactions to social exclusion in interethnic interactions. Encouragingly, pre-service teachers do not seem to underlie ingroup bias when evaluating interethnic social exclusion. In contrast they value the social norm of inclusion even more when the excluded student is an outgroup member. These findings imply that the inclusion of ethnic minorities in class be promoted by teachers. Teachers are important role models for their students, especially when it comes to ethnic topics. Thus, it is a very positive sign that they resist ingroup bias and try to establish inclusive class norms. With this, they have the potential to contribute to their students' moral development by promoting equality and social inclusion as a norm in class. Accordingly, future research should also focus on the development and thorough evaluation of prevention and intervention programs based on the current findings. Such programs should aim at raising students' and teachers' awareness of exclusion of ethnic minority students in the classroom, and teachers should be trained to successfully contribute to students' moral development and help them understand and internalize moral norms such as equality, fairness, and inclusion.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Both authors contributed meaningfully to the paper. Both authors developed the idea and the design of the study together. Both authors analyzed and interpreted the data. The first author made a first draft of the manuscript which was revised by the second author. Both authors have approved the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work and ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

This research was funded by a grant for young researches provided by IDeA Center Frankfurt.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We would like to thank the IDeA Center for funding and Julia Karbach for sharing her labs with us for this study. We thank the undergraduate research assistants Maurice Wendel, Ewelina Miczka, and Lena Bauer. We thank Amanda Habbershaw for her thorough language check. And we are grateful to all participants who supported this study.

1. ^In Germany, students in seventh grade are typically around thirteen years of age.

Abrams, D., and Killen, M. (2014). Social exclusion of children: developmental origins of prejudice. J. Soc. Issues 70, 1–11. doi: 10.1111/josi.12043

Bauman, S., and Del Rio, A. (2006). Preservice teachers' responses to bullying scenarios: comparing physical, verbal, and relational bullying. J. Educ. Psychol. 98, 219–231. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.219

Baumeister, R. F., and Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117, 497–529. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Baumert, J., and Schümer, G. (2002). “Familiäre Lebensverhältnisse, Bildungsbeteiligung und Kompetenzerwerb im nationalen Vergleich [Family living conditions, participation in education and aquisition of competencies in the national comparison],” in PISA 2000 - Die Länder der Bundesrepublik Deutschland im Vergleich, eds J. Baumert, C. Artelt, E. Klieme, M. Neubrand, M. Prenzel, U. Schiefelepp, et al. (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften), 159–202. doi: 10.1007/978-3-663-11042-2_6

Beißert, H., Bonefeld, M., Schulz, I., and Studenroth, K. (2019). “Beurteilung sozialer Ausgrenzung unter Erwachsenen: Die Rolle des Geschlechts [Evaluation of social exclusion among adults: The role of gender],” in Poster presented at the Conference on Morality (Mannheim).

Bonefeld, M., and Dickhäuser, O. (2018). (Biased) grading of students' performance: students' names, performance level, and implicit attitudes. Front. Psychol. 9:481. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00481

Bonefeld, M., Dickhäuser, O., Janke, S., Praetorius, A.-K., and Dresel, M. (2017). Migrationsbedingte Disparitäten in der Notenvergabe nach dem Übergang auf das Gymnasium [Student Grading According to Migration Background]. Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie 49, 11–23. doi: 10.1026/0049-8637/a000163

Bonefeld, M., Dickhäuser, O., and Karst, K. (2020). Do preservice teachers' judgments and judgment accuracy depend on students' characteristics? The effect of gender and immigration background. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 23, 189–216. doi: 10.1007/s11218-019-09533-2

Bonefeld, M., and Karst, K. (2020). “Döner vs. Schweinebraten – Stereotype von (angehenden) Lehrkräften über Personen deutscher und türkischer Herkunft im Vergleich [Stereotypes of (prospective) teachers about people of German and Turkish origin in comparative terms],” in Stereotype in der Schule, 1st Edn, eds S. Glock and H. Kleen (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 159–190. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-27275-3_6

Brewer, M. B. (1988). “A dual process model of impression formation,” in Advances in Social Cognition, eds R. S. Wyer and T. K. Srull (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum), 1–36.

Brewer, M. B. (2001). “Ingroup identification and intergroup conflict: When does ingroup love become outgroup hate?,” in Rutgers Series on Self and Social Identity, Vol. 3, eds R. D. Ashmore, L. J. Jussim, and D. Wilder (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 17–41.

Buhs, E. S., and Ladd, G. W. (2001). Peer rejection as antecedent of young children's school adjustment: an examination of mediating processes. Dev. Psychol. 37, 550–560. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.4.550

Carol, S., and Leszczensky, L. (2019). “Soziale Integration. Interethnische Freund- und Partnerschaften und ihre Determinanten [Social integration. Interethnic friendships and partnerships and their determinnants],” in Handbuch Integration [Handbook Integration], eds G. Pickel, O. Decker, S. Kailitz, A. Röder, and J. Schulze Wessel (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 1–14. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-21570-5_77-1

Cooley, S., Elenbaas, L., and Killen, M. (2016). “Chapter Four: Social exclusion based on group membership is a form of prejudice,” in Advances in Child Development and Behavior: Volume 51. Equity and Justice in Developmental Science. Implications for Young People, Families, and Communities, eds S. S. Horn, M. D. Ruck, and L. S. Liben (New York, NY: Academic Press Inc), 103–129. doi: 10.1016/bs.acdb.2016.04.004

Cross, S. E., and Madson, L. (1997). Models of the self: self-construals and gender. Psychol. Bull. 122, 5–37. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.5

DESTATIS (2016). Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit: Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund - Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus 2015 [Population and employment: Population with migrant background - results of the micro census 2015]. Available online at: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Service/Bibliothek/_publikationen-fachserienliste-1.html (accessed July 20, 2020).

Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., Hodson, G., and Houlette, M. A. (2005). “Social inclusion and exclusion: recategorization and the perception of intergroup boundaries,” in The Social Psychology of Inclusion and Exclusion, eds D. Abrams, J. Marques, and M. A. Hogg (New York, NY: Psychology Press), 263–282.

Evans, M. O. (1992). An estimate of race and gender role-model effects in teaching high school. J. Econ. Educ. 23, 209–217. doi: 10.1080/00220485.1992.10844754

Fiske, S. T., Lin, M., and Neuberg, S. L. (1999). “The continuum model. Ten years later,” in Dual Process Theories in Social Psychology, eds S. Chaiken and Y. Trope (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 231–254.

Fiske, S. T., and Neuberg, S. L. (1990). A continuum of impression formation from category-based to individuating processes: influences of information and motivation on attention and interpretation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 23, ed M. P. Zanna (New York, NY: Academic Press), 1–74. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60317-2

Glock, S. (2016). Stop talking out of turn: the influence of students' gender and ethnicity on preservice teachers' intervention strategies for student misbehavior. Teach. Teach. Educ. 56, 106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.02.012

Glock, S., and Karbach, J. (2015). Preservice teachers' implicit attitudes toward racial minority students: evidence from three implicit measures. Stud. Educ. Evaluation 45, 55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.03.006

Glock, S., Kneer, J., and Kovacs, C. (2013). Preservice teachers' implicit attitudes toward students with and without immigration background: a pilot study. Stud. Educ. Evaluation 39, 204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2013.09.003

Glock, S., and Krolak-Schwerdt, S. (2013). Does nationality matter? The impact of stereotypical expectations on student teachers' judgments. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 16, 111–127. doi: 10.1007/s11218-012-9197-z

Glock, S., Krolak-Schwerdt, S., and Pit-ten Cate, I. M. (2015). Are school placement recommendations accurate? The effect of students' ethnicity on teachers' judgments and recognition memory. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 30, 169–188. doi: 10.1007/s10212-014-0237-2

Hitti, A., and Killen, M. (2015). Expectations about ethnic peer group inclusivity: the role of shared interests, group norms, and stereotypes. Child Dev. 86, 1522–1537. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12393

Hitti, A., Mulvey, K. L., and Killen, M. (2011). Social exclusion and culture: the role of group norms, group identity and fairness. Anales de Psicología 27, 587–599.

Holder, K., and Kessels, U. (2017). Gender and ethnic stereotypes in student teachers' judgments: a new look from a shifting standards perspective. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 20, 471–490. doi: 10.1007/s11218-017-9384-z

Horn, S. S. (2003). Adolescents' reasoning about exclusion from social groups. Dev. Psychol. 39, 71–84. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.1.71

Kalter, F., and Kruse, H. (2015). “Ethnic diversity, homophily, and network cohesion in European classrooms,” in Social Cohesion and Immigration in Europe and North America: Mechanisms, Conditions, and Causality, eds R. Koopmans, B. Lancee, and M. Schaeffer (London: Routledge), 187–207.

Killen, M., Clark Kelly, M., Richardson, C., Crystal, D., and Ruck, M. (2010). European American children's and adolescents' evaluations of interracial exclusion. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 13, 283–300. doi: 10.1177/1368430209346700

Killen, M., Mulvey, K. L., and Hitti, A. (2013). Social exclusion in childhood: a developmental intergroup perspective. Child Dev. 84, 772–790. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12012

Killen, M., and Rutland, A. (2011). Children and Social Exclusion: Morality, Prejudice, and Group Identity. New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell. doi: 10.1002/9781444396317

Killen, M., and Stangor, C. (2001). Children's social reasoning about inclusion and exclusion in gender and race peer group contexts. Child Dev. 72, 174–186. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00272

Kleen, H., Bonefeld, M., Glock, S., and Dickhäuser, O. (2019). Implicit and explicit attitudes toward Turkish students in Germany as a function of teachers' ethnicity. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 22, 883–899. doi: 10.1007/s11218-019-09502-9

Klieme, E., Artelt, C., Hartig, J., Jude, N., Köller, O., Prenzel, M., et al. (2010). PISA 2009: Bilanz nach einem Jahrzehnt [PISA 2009: Status quo one decade later]. Münster: Waxmann. Available online at: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0111-opus-35393 (accessed July 20, 2020).

Kristen, C., and Granato, N. (2007). The educational attainment of the second generation in Germany: social origins and ethnic inequality. Ethnicities 7, 343–366. doi: 10.1177/1468796807080233

McCombs, R. C., and Gay, J. (1988). Effects of race, class, and IQ information on judgments of parochial grade school teachers. J. Soc. Psychol. 128, 647–652. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1988.9922918

Müller, K., and Ehmke, T. (2016). “Soziale Herkunft und Kompetenzerwerb [Social background and acquisition of competencies],” in PISA 2015. Eine Studie zwischen Kontinuität und Innovation, eds K. Reiss, C. Sälzer, A. Schiepe-Tiska, E. Klieme, and O. Köller (Münster: Waxmann), 285–316.

Mulvey, K. L. (2016). Children's reasoning about social exclusion: balancing many factors. Child Dev. Perspect. 10, 22–27. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12157

Mulvey, K. L., Boswell, C., and Niehaus, K. (2018). You don't need to talk to throw a ball! Children's inclusion of language-outgroup members in behavioral and hypothetical scenarios. Dev. Psychol. 54, 1372–1380. doi: 10.1037/dev0000531

Muntoni, F., and Retelsdorf, J. (2020). “Geschlechterstereotype in der Schule [Gender stereotypes at school],” in Stereotype in der Schule, 1st Edn, eds S. Glock and H. Kleen (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 71–97. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-27275-3_3

Nesdale, D., and Durkin, K. (1998). “Stereotypes and attitudes: implicit and explicit processes,” in Implicit and Explicit Mental Processes, eds K. Kirsner, C. Speelman, M. Maybery, A. O'Brien-Malone, M. Anderson, and C. MacLeod (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 219–232.

Oltmer, J. (2017). “Einwanderungsland Bundesrepublik Deutschland [Germany as an immigration country],” in Deutschland Einwanderungsland. Begriffe - Fakten - Kontroversen, eds K.-H. Meier-Braun and R. Weber (Bonn: Zentralen für politische Bildung ZpB), 225–226.

Parks, F. R., and Kennedy, J. H. (2007). The impact of race, physical attractiveness, and gender on education majors' and teachers' perceptions of students. J. Black Stud. 16, 936–943. doi: 10.1177/0021934705285955

Plenty, S., and Jonsson, J. O. (2017). Social exclusion among peers: the role of immigrant status and classroom immigrant density. J. Youth Adolesc. 46, 1275–1288. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0564-5

Posada, R., and Wainryb, C. (2008). Moral development in a violent society: Colombian children's judgments in the context of survival and revenge. Child Dev. 79, 882–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01165.x

Reinders, H. (2004). Entstehungskontexte interethnischer Freundschaften in der Adoleszenz [Developmental contexts for inter-ethnic friendships in adolescence]. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 7, 121–145. doi: 10.1007/s11618-004-0009-x

Rumberger, R. W. (1995). Dropping out of middle school: a multilevel analysis of students and schools. Am. Educ. Res. J. 32, 583–625. doi: 10.3102/00028312032003583

Rutland, A., Cameron, L., Milne, A., and McGeorge, P. (2005). Social norms and self-presentation: children's implicit and explicit intergroup attitudes. Child Dev. 76, 451–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00856.x

Rutland, A., and Killen, M. (2015). A developmental science approach to reducing prejudice and social exclusion: intergroup processes, social-cognitive development, and moral reasoning. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 9, 121–154. doi: 10.1111/sipr.12012

Schachner, M. K., Van de Vijver, F. J. R., Brenick, A., and Noack, P. (2016). “Who is friends with whom? Patterns of inter- and intraethnic friendships of mainstream and immigrant early adolescents in Germany,” in Unity, Diversity and Culture, eds C. Roland-Lévy, P. Denoux, B. Voyer, P. Boski, and W. K. Gabrenya Jr. (Reims: International Association of Cross-Cultural Psychology), 237–244.

Schacht, D., Kristen, C., and Tucci, I. (2014). Interethnische Freundschaften in Deutschland [Inter-ethnic friendships in Germany]. KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 66, 445–458. doi: 10.1007/s11577-014-0280-7

Shur, K. A. (2006). Teacher responses to children's verbal bullying and social exclusion. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Pennsylvania State University, USA.

Smetana, J. G. (1989). Toddlers' social interactions in the context of moral and conventional transgressions in the home. Dev. Psychol. 25, 499–508. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.25.4.499

Südkamp, A., Kaiser, J., and Möller, J. (2017). “Ein heuristisches Modell der Akkuratheit diagnostischer Urteile von Lehrkräften,” in Diagnostische Kompetenz von Lehrkräften. Theoretische und methodische Weiterentwicklungen, eds A. Südkamp and A.-K. Praetorius (Münster: Waxmann), 33–38.

Tajfel, H. (1974). Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Information 13, 65–93. doi: 10.1177/053901847401300204

Tajfel, H. (1978). “The achievement of inter-group differentiation,” in European Monographs in Social Psychology: Vol. 14. Differentiation between Social Groups. Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, ed H. Tajfel (London: Academic Press [for] European Association of Experimental Social Psychology), 77–100.

Tajfel, H. (1982). Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 33, 1–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.33.020182.000245

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1979). “An integrative theory of inter-group conflict,” in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds W. G. Austin and S. Worchel (Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole Pub. Co), 33–47.

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1986). “The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour,” in Psychology of Intergroup Relation, eds S. Worchel and W. G. Austin (Chicago: Hall Publishers), 7–24.

Tenenbaum, H. R., Leman, P. J., Aznar, A., Duthie, R., and Killen, M. (2018). Young people's reasoning about exclusion in novel groups. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 175, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2018.05.014

Turiel, E. (2008). Thought about actions in social domains: morality, social conventions, and social interactions. Cogn. Dev. 23, 136–154. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2007.04.001

Turner, J. C., Brown, R. J., and Tajfel, H. (1979). Social comparison and group interest ingroup favouritism. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 9, 187–204. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420090207

Ungern-Sternberg, A. von. (2008). Religionsfreiheit in Europa: Die Freiheit individueller Religionsausübung in Großbritannien, Frankreich und Deutschland - ein Vergleich [Religious freedom in Europe: The liberty to engage in individual religion in Great Britain, France and Germany – a comparison]. Jus Ecclesiasticum: Vol. 86. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Verkuyten, M., and Thijs, J. (2002a). Multiculturalism among minority and majority adolescents in the Netherlands. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 26, 91–108. doi: 10.1016/S0147-1767(01)00039-6

Verkuyten, M., and Thijs, J. (2002b). Racist victimization among children in The Netherlands: the effect of ethnic group and school. Ethn. Racial Stud. 25, 310–331. doi: 10.1080/01419870120109502

Walter, O. (2009). “Herkunftsassoziierte Disparitäten im Lesen, der Mathematik und den Naturwissenschaften: ein Vergleich zwischen PISA 2000, PISA 2003 und PISA 2006 [Disparities in reading, mathematics and science associated with immigrant background – A comparison between PISA 2000, PISA 2003, and PISA 2006],” in Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft Sonderheft: Vol. 10. Vertiefende Analysen zu PISA 2006. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, eds M. Prenzel and J. Baumertpp (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften/GWV Fachverlage GmbH Wiesbaden), 149–168. doi: 10.1007/978-3-531-91815-0_8

Ward, C. A., Bochner, S., Furnham, A., and Furnham, A. (2001). The Psychology of Culture Shock, 2nd Edn. Hove: Routledge.

Weis, M., Müller, K., Mang, J., Heine, J. H., Mahler, N., and Reiss, K. (2019). “Soziale Herkunft, Zuwanderungshintergrund und Lesekompetenz [Social status, immigrant background and reading skills],” in PISA 2018. Grundbildung im internationalen Vergleich, 1st Edn, eds K. Reiss, M. Weis, E. Klieme, and O. Köller (Münster: Waxmann), 129–162.

Winkler, N., Zentarra, A., and Windzio, M. (2011). Homophilie unter guten Freunden: Starke und schwache Freundschaften zwischen Kindern mit Migrationshintergrund und einheimischen Peers. Soziale Welt 62, 25–43. doi: 10.5771/0038-6073-2011-1-25

Yoon, J. S., and Kerber, K. (2003). Bullying: elementary teachers' attitudes and intervention strategies. Res. Educ. 69, 27–35. doi: 10.7227/RIE.69.3

Zahn-Waxler, C. (2000). “The development of empathy, guilt, and internalization of distress: Implications for gender differences in internalizing and externalizing problems,” in Wisconsin Symposium on Emotion: Anxiety, Depression, and Emotion, Vol. 1, ed R. Davidson (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 222–265. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195133585.003.0011

Keywords: social exclusion, interethnic exclusion, intergroup exclusion, teacher reactions, teacher evaluations, intergroup processes

Citation: Beißert H and Bonefeld M (2020) German Pre-service Teachers' Evaluations of and Reactions to Interethnic Social Exclusion Scenarios. Front. Educ. 5:586962. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.586962

Received: 24 July 2020; Accepted: 09 November 2020;

Published: 04 December 2020.

Edited by:

Luciano Gasser, University of Teacher Education Lucerne, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Sue Walker, Queensland University of Technology, AustraliaCopyright © 2020 Beißert and Bonefeld. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hanna Beißert, YmVpc3NlcnRAZGlwZi5kZQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.