- Department of Curriculum and Instruction, Texas A&M University-Commerce, Commerce, TX, United States

In the United States, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, schools and testing centers were forced to close on-site locations. With teacher candidates no longer able to complete clinical teaching or take certification exams in person, states created new recommendations for facilitating a pathway to teacher certification. Specifically, 19 states provided guidelines that allowed educator preparation programs (EPPs) flexibility in how teacher candidates completed existing certification requirements. By analyzing summaries of these states’ guidelines, themes of time, technology, flexibility/non-flexibility, and EPPs emerged. Using a comprehensive lens, this brief examines the role and implications of each of these themes in teacher certification during these unprecedented times.

Introduction

Following the White House declaration of a national public health emergency on March 13, 2020 (U.S. President, 2020), educators across the United States scrambled to find innovative ways to complete the final months of the school year. Education programs and policies were either suspended or amended to meet the conditions of the health crisis, forcing educators to use virtual instruction and at-home delivery systems. This historic disruption impacted both K-12 and higher education, presenting unique challenges to teacher education. To address these challenges, educator preparation programs (EPPs) adopted remote systems as a means to help teacher candidates fulfill certification requirements.

Traditional teacher certification in the United States requires teacher candidates to have a college degree, education-related coursework, clinical teaching experience, and passing scores on Praxis exams (National Council on Teacher Quality, n.d.). While those completing teacher candidacy during the 2019–2020 academic year were able to continue their coursework during the pandemic, the availability of traditional clinical settings and testing centers changed. Therefore, states updated guidelines to address these two areas specifically. Thirty-three states fully or conditionally waived Praxis exam requirements for certification, with the rest either providing no guidance or no change in terms of certification exam requirements (Deans for Impact, 2020b). Additionally, many suspended traditional clinical requirements for candidates applying for certification in the spring of 2020. Nineteen states did not change on-site clinical teaching requirements for the 2019–2020 academic year (Deans for Impact, 2020b). Instead, they offered new flexibilities to support teacher candidates in meeting those requirements.

This brief synthesizes the policy guidelines these 19 states developed to maintain new teacher certification requirements during the pandemic, as summarized in the Deans for Impact COVID-19 Teacher Preparation Policy Database (2020a) listed on the Deans for Impact (2020c) page for educator preparation. In our analysis we examined the language in the embedded summaries linked to each of the states included in the Deans for Impact database. Throughout this brief, when we mention “teacher certification,” we are referring to a teacher candidate’s initial certification, rather than an additional certification. In this brief, we identify key themes in the guidelines, discuss major implications, and make actionable policy recommendations for sustaining quality teacher preparation in times of crisis and unpredictability.

States’ Guidelines for Meeting Existing Clinical Requirements: the Role of Time, Technology, Flexibility/No-Flexibility, and EPPs

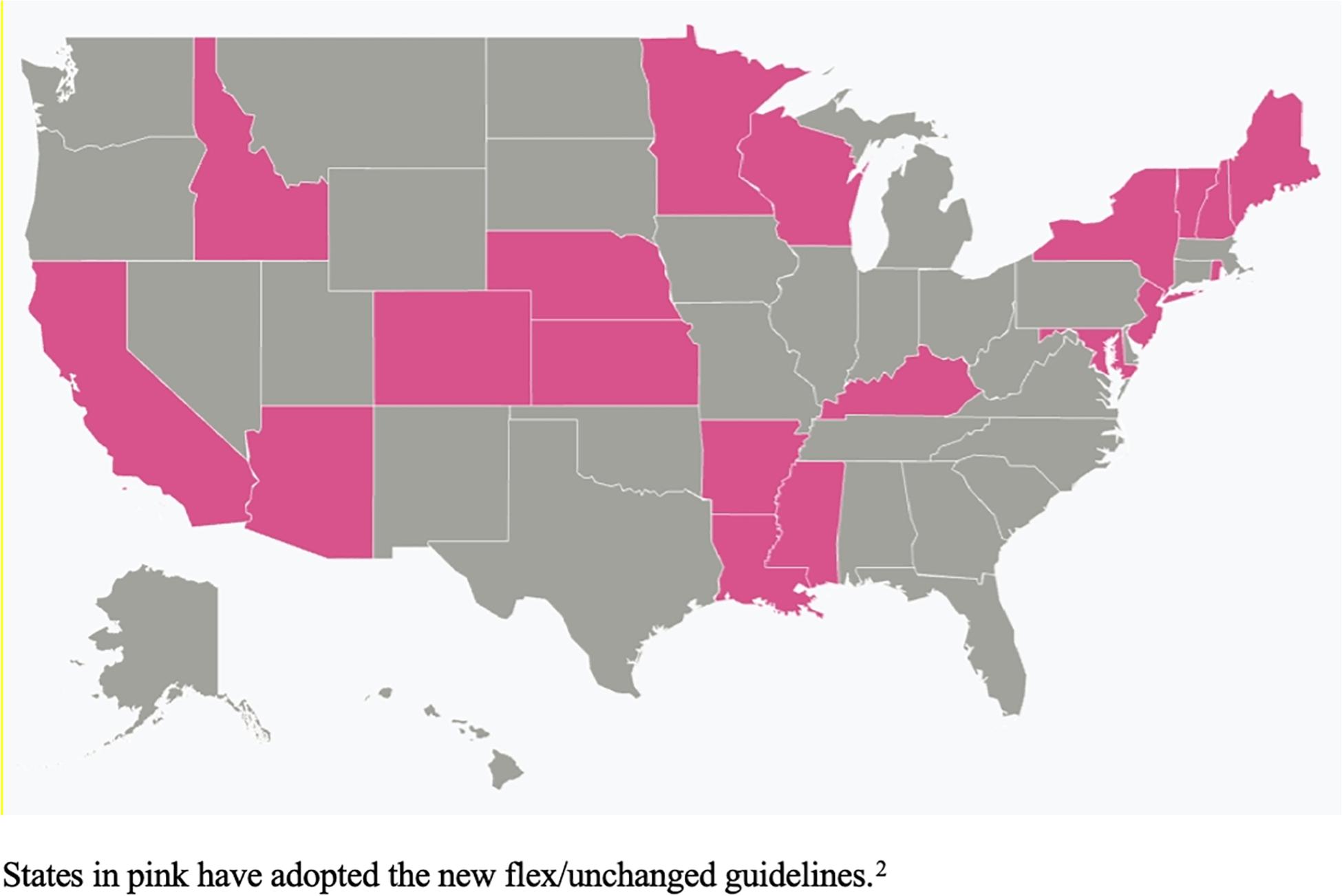

During the pandemic, states granted university-based EPPs more authority to modify their programs and determine teacher candidates’ eligibility for certification (Education Commission of the United States, 2020). The Deans for Impact (2020b) teacher preparation guideline database labels the 19 states where existing on-site clinical requirements remained unchanged for 2019–2020, but teacher preparation programs were given new flexibilities to support candidates in meeting those requirements, as “Unchanged/New Flex.”1 Figure 1 provides a map of the states that adopted these guidelines. Although this category implies a bit of an oxymoron, it also suggests that state policymakers wanted to keep their traditional standards; yet, they recognized that it would not be feasible for teacher candidates to complete on-site clinical teaching when schools were closed. In contrast, states that did not adopt unchanged, new flex guidelines instead waived clinical teaching regulations, conditionally modified clinical teaching expectations, or did not change any rules for on-site clinical teaching for the remainder of the academic year.

Time, technology, flexibility, and EPPs were recurrent themes in the clinical experience guidelines produced by the 19 states. Supplementary Appendix Table 1 contains excerpts from the states’ guideline summaries, provided in the Deans for Impact (2020b) database, which illustrate each of these themes. In the following sections, we discuss each theme and present related implications.

States in pink have adopted the new flex/unchanged guidelines. The authors used the Travelmapper mobile app (Bingkodev, 2020) to create this map.

Time

The importance of extending time limits to complete certification requirements is evident in the language used to discuss both testing and clinical experiences. In 16 of the 19 state guideline summary documents, several references were made to deferrals, extensions, and term waivers to adjust or expand time limits, typically between six months to a year. Three summary documents (Maine, Nebraska, and New Jersey) did not refer to extended time in completing certification. Instead, they described flexibility in other ways. Yet, these states maintained a flexible stance toward certification by accepting substitute qualifications as defined by “alternative experiences” or plans specifically designed for a given candidate.

Most of the guidelines explicitly mentioned time limits to open a testing window subject to the testing vendor’s ability to provide at-home testing. Still, temporary certification extensions were also made to facilitate placing teacher candidates who were recommended by their universities or EPPs in a position to get hired by school districts, with the understanding that additional professional development and support might be needed during induction and their first year of teaching. Such hiring placements, however, do not appear to be made without restriction, as California’s “variable term waiver,” or Utah’s alternate authorization for academic year one, are examples of provisional certification for an inductee during the first year of teaching.

Technology

Technology emerged as an important means for supporting teacher candidates in their on-site clinical teaching experience. In 16 of the 19 state policy summary documents, references were made to using technology to facilitate certification, teaching, and professional development. The language used to name technology as a means for continuous learning included, “remote learning,” “digital platforms,” “online,” “virtual,” “non-traditional,” and “alternative experiences.” Although “non-traditional” and “alternative” experiences are not synonymous with the use of technology, additional information within selected states’ guidelines implied technology was used (e.g., edTPA and KPTP). edTPA and KPTP are portfolio assessments requiring teacher candidates to submit video clips and analysis of their teaching performance in lieu of taking an exit Praxis exam. Minnesota, New Jersey, and New York included the educative Teacher Performance Assessment (edTPA) (Stanford Center for Assessment, Learning and Equity, n.d.) in their guidelines; whereas Kansas mentioned its assessment tool, Kansas Performance Teaching Portfolio (KPTP), which was described in the summary as an “innovative and adaptive opportunity for candidate learning” (Kansas State Department of Education, 2020, p. 11).

Based on this example, we determined that what state guidelines intended to say, but may not have explicitly specified, is that alternative ways of teaching and learning may include many forms of technology. Policy summaries that alluded to using creative technologies in the same document with another more specific reference to web-based technology (i.e., digital or online), led us to interpret this language broadly, and include terminology such as “innovative,” “alternative,” or “creative” in the technology theme. Kansas, for example, identified their KPTP as “an innovative and adaptive opportunity,” Maryland will accept a “creative initiative,” California notes “atypical opportunities to connect,” Kentucky mentions “non-traditional instruction,” and New York uses the term “distance education” in similar contexts related to field experience. The vagueness of these non-descript phrases implies that technology is a broad category that includes many ways for teachers to experience clinical teaching and mentoring beyond video conferencing, for example.

Flexibility/No Flexibility

Flexibility emerged as a theme across the guidelines in two dichotomous, yet interrelated ways. Although Deans for Impact (2020b) created the category “Unchanged, New Flex” to illustrate states’ attitudes toward clinical teaching during a health pandemic, our analysis of the language used across the summary documents reveals that some form of flexibility was implemented in other areas of certification across all 19 states. For instance, 14 of the 19 states’ summaries mentioned some kind of limitation to flexibility, as indicated by the five states in our sampling that did not change their licensing requirements. California, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, and New York modified their teacher license by adding provisions to accommodate first-year teachers under variable term waivers or short-term, non-renewable emergency certificates.

This contrast (flexibility vs. no flexibility) supports the idea that these 19 states chose to maintain their standard certification policies; yet, recognized the need to be flexible about how these policies were met. Their intent in offering EPPs and teacher candidates’ alternatives for accomplishing the tasks required for teacher certification is communicated in various ways, but mostly in connection with adjusted timelines. The District of Columbia, for example, offered extended opportunities to find modified clinical teaching experiences. Arkansas and Colorado provided options for EPPs to evaluate candidates on a “case-by-case basis” and other states allowed candidates the opportunity to seek experiences comparable to on-site teaching and mentoring “in lieu” of the standard face-to-face classroom fieldwork. The conditional language used across the policy summaries for these 19 states further suggested that policymakers considered their certification requirements (i.e., assessment by Praxis or portfolio, mentoring, and clinical teaching) necessary and important elements of teacher preparation; yet, also recognized that the unusual and uncertain conditions created by school closures called for creative and innovative measures for accomplishing them. Flexibility is also supported by the use of conditional language (i.e., may, can, should), which implies that a guideline is suggested, or encouraged, but not enforced.

EPPs and Support

The role of EPPs is central to providing the support and flexibility called for in these state guidelines. These summaries indicate that state education boards or teacher licensing agencies established the guidelines for testing and may determine the number of clinical teaching hours necessary to demonstrate competency in teaching. However, the language found in the summary documents indicated that EPPs and institutions of higher education (IHE) have full autonomy for fulfilling those expectations. All of the 19 states, except Maryland, identified EPPs or IHEs as the governing power in moving teacher candidates through the system. Instead of naming an EPP, Maryland specified working in partnership with “Professional Development and Partner Schools.” Thus, EPPs were responsible for administering clinical teaching programs with whatever flexible decisions were necessary during the health crisis. This implies that EPPs must follow state regulations for certification; yet, have the power to modify these regulations with limited oversight in times of crisis.

We included support in this theme alongside EPPs because we noticed a close relationship between the kind of support named and the role that EPPs have in delivering services to support teacher candidates. Of the 19 states we analyzed, 11 states identified some form of support required to facilitate clinical teaching and/or training teacher candidates. In some cases, EPPs were named to support candidates through “remote options,” help candidates apply for “alternative authorizations,” or “help candidates meet expectations” during pre-service. However, Kentucky and Minnesota also named EPPs to work with teachers during their induction to teaching in their first year of service. Although the word “support” specifically appeared in approximately half of the summaries we reviewed, the overall themes of flexibility and time across the documents imply that teacher candidates require additional support completing certification during the unprecedented interruptions to their programs and that EPPs are instrumental to facilitating the transition to new or modified forms of training.

Implications of States’ Teacher Certification Guidelines

Based on guidelines from the 19 states that did not change their clinical requirements, but offered flexible ways to meet them, we have developed a list of implications affecting teacher candidates, new teachers, mentor teachers, administrators, and policymakers.

Path to Certification

The guidelines reviewed in this brief, given the context, have provided sufficient flexibility, thereby enabling teacher candidates to serve as teachers without delay. In this respect, these guidelines have been successful because they have, at the very least, facilitated the process and created a clear pathway to certification. The commitment to keeping standards for teacher certification in place, in spite of the challenges imposed by school closures, demonstrates a commitment to growing the body of highly qualified new teachers. Depending on the state, within 6–12 months, teachers will move from being provisionally to fully certified as they complete any remaining requirements. Enabling these new teachers to assume a standard teaching role will undoubtedly help alleviate the current teacher shortage, which could be exacerbated amid uncertainties related to the COVID-19 pandemic (Griffith, 2020; Hunt Institute, 2020).

Our analysis of the flexibility these 19 states provided EPPs suggests that the clinical teaching experience is highly valued. To demonstrate how some states created alternative and creative methods for engaging pre-service teachers in meaningful clinical teaching experiences, we have provided examples from selected states. For instance, at the onset of the pandemic, the Kansas State Department of Education included a statement of obligation to student teachers in their Continuous Learning Task Force Guidelines, which explicitly recommended supporting the “newest members of the profession” by including them “as much as possible” in “innovative roles… through virtual meetings under the direction and supervision of the cooperating teacher” (Kansas State Department of Education, 2020, p. 10). This call for innovation and flexibility demonstrates an unwavering commitment to developing new teachers in spite of crisis conditions.

Several states allowed provisions for EPPs to evaluate the completion of clinical teaching requirements for their teacher candidates on a case-by-case basis. For example, according to the (Idaho State Board of Education, 2020) COVID-19 School Operations Guidance (2020), “students need to work with their postsecondary program providers on any remaining requirements they may need in order to meet their program requirement for this school year” (p. 2). Other states demonstrated flexibility by explicitly allowing remote or virtual opportunities to complete clinical requirements. Colorado, for example, required that “all hours must be met to achieve license” and allows EPPs the “flexibility to ensure continuity of instruction via online learning experiences, including video observation requirements” (Deans for Impact, 2020a). Likewise, the California Alliance for Inclusive Schooling (CAIS) provided teacher candidates a statewide series of “Active Education Webinars” on a variety of topics, not limited to, and including, positive behavior supports, culturally responsive teaching, evidence-based literacy practices, and differentiated instruction, to replicate face-to-face teaching experiences ordinarily developed by teaching alongside a mentor teacher (California Alliance for Inclusive Schooling [CAIS], n.d.).

Varied Teacher Certification Requirements

In allowing for flexible approaches to meeting certification requirements, states have increased EPPs’ authority to interpret guidelines and act accordingly. This will certainly result in varied clinical teaching experiences. This variability is further compounded by EPPs’ ability to alter requirements for each teacher candidate at their discretion. With few explicit requirements and limited accountability, this may lead to teachers with different levels of preparedness.

Clinical Teaching Gaps

Since teacher candidates were forced to use alternative means to fulfill part of their clinical teaching, some teachers may have gaps that will need to be filled to become effective teachers and pass required certification exams. Having already completed their teacher preparation programs, EPPs will no longer be responsible for their graduates’ success. Thus, the responsibility will fall largely on new teachers, teaching mentors, administrators, and other instructional support faculty.

A Trend Toward “Unchanged, New Flex” Guidelines

Currently, nearly half of US states have not yet adopted the “Unchanged, New Flex” guidelines which allow flexibility in achieving states’ existing clinical teaching requirements. Instead, these states’ clinical teaching guidelines remain unchanged, waived, or offer no guidance. These alternatives to “Unchanged, New Flex” have been applied as a means to allow teacher candidates to earn their certification when face-to-face clinical experiences and certification tests were not possible. While these responses have provided a solution for the time being, they may not be feasible long term or indefinitely. Over time, these responses may leave teacher candidates unprepared, and/or create teacher certification requirements which cannot be achieved. Consequently, if schools and testing centers do not open their doors quickly, more states will be forced to follow “Unchanged, New Flex” guidelines to allow teacher candidates flexibility in meeting existing teacher certification requirements. In fact, three states (Georgia, Illinois, and Texas), have already transitioned to “Unchanged, New Flex” guidelines for clinical teaching for the 2020–2021 academic year (Deans for Impact, 2020b).

Recommendations

States, districts, schools, and EPPs can help ensure quality teacher preparation during times of crisis or uncertainty by following the recommendations listed:

• Proactively designing quality alternative clinical teaching experiences. Although states are responsible for mandating alternative clinical experiences (Deans for Impact, 2020a), EPPs are charged with their implementation. EPPs can better prepare for such mandates by proactively developing virtual alternative teaching experiences for times in which in-person teaching is not possible (TNTP, n.d.). In doing so, EPPs should carefully consider how they can prepare teacher candidates using alternative means without compromising the quality of their clinical teaching experience. This will require, among other things, an understanding of best practices, thorough planning, and creativity. States can support the work of EPPs by creating databases to house, curate, and share best practices (TNTP, n.d.).

• Clearly defining terms and using shared language to articulate quality clinical experiences. Prior to the pandemic, the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (AACTE) called for the creation of a common language in teacher preparation and clinical practice (American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education [AACTE], 2018). Given the new guidelines, states, districts, schools, and EPPs must work together to define what an “alternative” clinical experience is and looks like. Given the current language, this is clearly open to interpretation and can relate to different aspects of clinical experiences, such as guided student teaching, residency practice, and mentor coaching through digital connectivity. The use of shared language and definitions will help to reduce variability in the interpretation of the guidelines and teacher preparation quality.

• Supporting new in-service teachers. Once teacher candidates have become certified, schools and districts should quickly adopt a plan to address variability in teacher preparedness and to fill in any gaps. We should not assume teaching experiences alone will be adequate to prepare new teachers to pass certification exams and become effective teachers. Instead, an immediate and intensive approach will be needed to address teachers’ areas of weakness. States can provide additional support through targeted professional development and induction programs (Deans for Impact, n.d.).

Looking Toward the Future

At the time of submission, numerous COVID-19 cases across the United States remain. While many school buildings and testing centers have reopened, we cannot predict if/when they will close again as a result of the current pandemic or due to a future disturbance. These obscure circumstances have highlighted the need for policymakers and EPPs to be prepared for any future challenges which may disrupt traditional teacher certification processes. To address these potential obstacles, the language in teacher preparation policies must allow the flexibility for teacher candidates to complete their clinical teaching and certification exams face-to-face or using alternative means, amid such disturbances. With so many unknowns, we anticipate guidelines nationwide will continue to change and will add language specifying how to meet teacher certification requirements. In turn, these guidelines may evolve into policies that will force us to reconsider how teachers are certified.

Author Contributions

JR, KM, and LS conceived the presented idea. LS conducted the research and analysis. JR and LS wrote the initial manuscript. KM revised the manuscript for clarity, accuracy, and consistency. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2020.583896/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

- ^ 19 states classified as “unchanged/new flex” for the 2019–2020 academic year in Deans for Impact (2020b) database: Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, District of Columbia, Idaho, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont.

References

American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education [AACTE] (2018). A Pivot Toward Clinical Practice, Its Lexicon, and the Renewal of Educator Preparation: Summary Brief. Available online at: https://aacte.org/resources/research-reports-and-briefs/clinical-practice-commission-report/ (accessed July 15, 2020).

Bingkodev (2020). Travelmapper - Travel Maps, Tracker & Planner App. Playstore, Version 1.9.6. Available online at: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=au.com.bingko.travelmapper&hl=en_US (accessed July 15, 2020).

California Alliance for Inclusive Schooling [CAIS] (n.d.). California Alliance for Inclusive Schooling (CAIS) Active Education Webinars For California Teacher Candidates. Available online at: https://www.ctc.ca.gov/docs/default-source/commission/files/covid-19-cais-webinars.pdf?sfvrsn=193e2cb1_2 (accessed September 1, 2020).

Deans for Impact (2020a). Colorado State-Level Policy Guidance: Spring 2020). Available online at: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1mjrpdZIYy888E1pYLXA9VKnSQ5t-JNQfuoDQFqZBblE/edit (accessed September 1, 2020).

Deans for Impact (2020b). COVID-19 Teacher Preparation Policy Database. Available online at: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1SnNKv38kfGHgEIWlz-VWZ4ejo9MTSmXoMLPrSp5AFu8/edit#gid=1485679140 (accessed July 15, 2020).

Deans for Impact (2020c). Resources. Available online at: https://deansforimpact.org/resources/covid-19-resources/ (accessed July 10, 2020).

Deans for Impact (n.d.). Responding to COVID-19: Three Recommendations for Educator-Preparation Policy. Available online at: https://deansforimpact.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Three-recommendations-for-ed-prep-policy_Responding-to-COVID-19.pdf (accessed July 10, 2020).

Education Commission of the United States (2020). COVID-19 Update: State Policy Responses and Other Executive Actions to the Coronavirus in Public Schools. Available online at: https://www.ecs.org/covid-19-update/ (accessed July 15, 2020).

Griffith, M. (2020). The Impact of the COVID-19 Recession on Teaching Positions. Available online at: https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/blog/impact-covid-19-recession-teaching-positions (accessed July 10, 2020).

Hunt Institute (2020). Educator Preparation and New Teacher Licensures During COVID-19. Available online at: http://www.hunt-institute.org/resources/2020/05/educator-preparation-and-new-teacher-licensures-during-covid-19/ (accessed July 10, 2020).

Idaho State Board of Education (2020). COVID-19 School Operations Guidance. Available online at: https://www.sde.idaho.gov/coronavirus/SBOE/COVID-19-Guidance-3-27-2020.pdf (accessed September 6, 2020).

Kansas State Department of Education (2020). Continuous Learning Task Force Guidance. Available online at: https://www.ksde.org/Portals/0/Communications/Publications/Continuous%20Learning%20Task%20Force%20Guidance.pdf (accessed September 5, 2020).

National Council on Teacher Quality (n.d.). What Makes Teacher Prep “Traditional” or “Non-Traditional”?. Available online at: https://www.nctq.org/dmsView/NCTQ_-_What_Makes_Teacher_Prep_Traditional_or_Non_Traditional (accessed July 15, 2020).

Stanford Center for Assessment, Learning and Equity (n.d.). edTPA. Available online at: https://scale.stanford.edu/teaching/consortium (accessed October 21, 2020).

TNTP (n.d.). Teacher Preparation and Licensure During the COVID-19 Epidemic: Recommendations for State Leaders. Available online at: https://tntp.org/assets/documents/Teacher_Preparation_and_Licensure_Recommendations_for_State_Policy_Makers-TNTP.pdf (accessed July 10, 2020).

Keywords: COVID-19, teacher education, clinical teaching, teacher certification, school closures, policy guidelines, pandemic, education

Citation: Slay LE, Riley J and Miller K (2020) Facilitating a Path to New Teacher Certification Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Unpacking States’ “Unchanged-New Flex” Guidelines. Front. Educ. 5:583896. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.583896

Received: 15 July 2020; Accepted: 12 October 2020;

Published: 03 November 2020.

Edited by:

Jane McIntosh Cooper, University of Houston, United StatesReviewed by:

Ana Luiza Bustamante Smolka, Campinas State University, BrazilBalwant Singh, Partap College of Education, India

Copyright © 2020 Slay, Riley and Miller. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laura E. Slay, bGF1cmEuc2xheUB0YW11Yy5lZHU=

Laura E. Slay

Laura E. Slay Jacqueline Riley

Jacqueline Riley Karyn Miller

Karyn Miller