- Department of Early and Middle Grades Education, West Chester University, West Chester, PA, United States

Seven weeks into our Spring 2020 semester, the Covid-19 pandemic was wreaking havoc on the world. The pandemic caused immediate shutdowns to schools and universities fundamentally changing how we plan for, teach, guide, and work with students. This paper explores how two first-year Assistant Professors navigated the challenges we faced and the learning opportunities we embraced while continuing our work as teacher educators amid a pandemic-induced shutdown. We employed collective self-study to examine our experiences while transitioning to remote learning with pre-service teachers using Moore’s (2012, 1993, 1989) transactional distance theory as an analytical framework to review our work as teachers in an online setting. We found that educators need to be open to continuous enhancements of instructional practices, there is a need to develop ways to equalize positions between the instructor and students, and we need to be conscious of opportunities students have to demonstrate creativity in their work. As part of this review, we developed and used a Four R’s Professional Inquiry Model (Recognition, Reflection, Reaction, Results) based on Moore’s work to help make meaning of our findings and recommendations for other practitioners.

Introduction

Seven weeks into our Spring 2020 semester, our university shifted to “alternate modes of instruction for the remainder of the semester.” While the Covid-19 pandemic was wreaking havoc on the world medically, it had also reached the classroom door, fundamentally changing how we plan for, teach, guide, and supervise our students. This paper explores how we, Crystal and Mike, both first-year Assistant Professors, navigated the challenges we faced and the learning opportunities we embraced while continuing our work as teacher educators amid a pandemic-induced shutdown.

Although much is written about educational change, schools’ and universities’ professional culture has remained static (Cuban, 1993; Fullan, 2016; Ryan, 2017; Delpit, 2019). However, the immediate change imposed on the world by the Covid-19 pandemic forced all educators to act and react instantaneously. As we experienced the wrath of the shutdowns created by the Covid-19 pandemic, we both noted how this impacted our work as teachers and teacher educators, changing everything about our day to day work. It created a critical incident that caused us to change our teaching practices and the way we fostered our student teachers’ work. With this inquiry, we explore what we can learn from our experiences through the following question: What can we learn about our practices as teacher educators and student teaching supervisors by using distance learning theory to examine our work as schools moved to remote learning during the Covid-19 pandemic?

As experienced educators, we feel adept at integrating technology into our typical face-to-face teaching. Additionally, we understand that integrating technology creates opportunities for educators to examine their work and how different tools and resources can enhance learning (Ruggiero and Mong, 2015). However, despite increased professional learning, additional professional resources, and access to technology resources, we understand progress in this area has been slow as a result of individual teachers’ willingness, aptitude, and attitude toward technology (Brandao, 2015; Ruggiero and Mong, 2015; Farjeon et al., 2019). The pandemic has caused educators at all levels to make immediate and drastic changes to our practices. We were no longer integrating technology; instead, we had to rely on technological tools and applications to provide us with new learning spaces. We could no longer enter our schools, universities, and classrooms. Moore’s theory of transactional distance (2012, 1993, and 1989) provided us with a means to examine our understandings and perceptions regarding this sudden transition to remote learning.

Theoretical Framework

In this paper, we use Moore’s transactional distance theory as an analytical framework to review our work as teachers in an online setting. Transactional distance theory addresses teaching and learning in contexts other than typical face to face classrooms (Garrison, 2000; Gorsky and Caspi, 2005; Moore, 2012; Huang et al., 2015). In particular, Moore (2012) challenges us to look at and think about teaching and learning in separate locations “as a significantly different pedagogical domain” (p.67). Transactional distance theory asks us to consider the interplay between teachers, students, and content in environments where the teachers and students are physically separated from one another (Moore, 2012). While the “distance” between students and instructors may be far apart, Moore’s theory looks at the perceived psychological distance that is created by the interplay between the structure of a course and dialog with and among the students and instructors (Moore, 2012; Huang et al., 2015). As Gorsky and Caspi (2005) put it, “the essential distance in distance education is transactional, not spatial or temporal” (p.2). This emphasizes the teaching that occurs in an online space through three facets of instruction, including dialog, structure, and learner autonomy.

Moore notes that the pedagogical constructs of structure and dialog are critical to diminishing students’ perception of transactional distance in online courses (Garrison, 2000; Shannon, 2002; Falloon, 2011; Moore, 2012). Structure connotes how the course is designed, including objectives, teaching strategies, presentations, materials, and assessment (Garrison, 2000; Moore, 2012; Huang et al., 2015). The course structure can be rigid or flexible or move between the extremes based on the content, interactions between the student and or the needs of the students (Huang et al., 2015; Moore, 2012; Shannon, 2002). In order to offer variety and individualization that will best support each learner, the structure must be more forgiving (Huang et al. (2015). In addition to structure, Moore’s theory talks of the importance of dialog or constructive interpersonal exchanges that helps the learner solidify their understanding of the content (Gorsky and Caspi, 2005; Moore, 2012). There is no one fixed conception about how dialog occurs, and given that there is an ever-increasing amount of tools teachers and students can use to communicate online, it is critical to ensure that the opportunities for interaction are promoting student understanding (Garrison, 2000; Gorsky and Caspi, 2005; Moore, 2012). The level of interaction between teacher and learner will determine the degree of learner autonomy (Garrison, 2000). Ultimately, productive dialog lives in the learning spaces between the conversations students hold with one another and those students have with their teachers (Gorsky and Caspi, 2005; Moore, 2012).

According to Moore, the interplay between structure and dialog and transactional distance are also mediated by the student’s ability to exercise learning autonomy (Garrison, 2000; Moore, 2012; Huang et al., 2015). “The greater the transactional distance, the greater responsibility is placed on the learner” (Garrison, 2000, p.8). Here the instructor needs to consider the learner’s ability to manage their learning, recognize if the format is working or not for students, and make meaningful adjustments to promote student learning (Garrison, 2000; Shannon, 2002; Moore, 2012). At one end of the spectrum, the student would be driving their learning, while at the other end, the teacher would have complete control over the way students experienced content delivery (Garrison, 2000; Moore, 2012). Transactional distance theory informed our practice as we adopted new methods to compensate for imposed distance constraints. In particular, we used it as a lens through which we could examine our work when all teaching and supervision moved online due to the Covid-19 pandemic. It was essential that we examine the degree of learner autonomy that resulted when student teachers were removed from the classroom environment and placed in remote learning rooms. This online learning atmosphere required new methods for communicating with our students, as well as newly learned online pedagogy for both the professor and students, ultimately creating unforeseen structural barriers.

Literature Review

Online Learning

Online learning is increasingly becoming a popular educational option for students at all levels. It encompasses a multitude of learning platforms, instructional delivery methods, and media to engage students with the content (Keengwe and Kidd, 2010; Salmon, 2011; Moore, 2012; Korhonen et al., 2019). While “technology” itself is often associated with innovation, the literature suggests that as we are moving into the third decade of the 21st-century technology is a critical factor in innovative online learning and related to instructional practices (Salmon, 2011; Moore, 2012; Black, 2013; Shearer, 2013; Arason, 2019). Instructional decisions determine how students will interact with the content and with each other to promote learning (Falloon, 2011; Salmon, 2011, 2019; Shearer, 2013; Huang et al., 2015). Given the self-directed nature of online learning, instructors must ensure that they have established clear goals and expectations to scaffold students’ learning as they interact with assignments (Falloon, 2011; Salmon, 2011; Huang et al., 2015; Delen and Liew, 2016; Kim et al., 2019; Korhonen et al., 2019). The literature also notes the challenges some students face with being fully responsible for regulating their learning online (Falloon, 2011; Salmon, 2011; Delen and Liew, 2016; Kim et al., 2019; Korhonen et al., 2019). This requires instructors to be mindful of concepts of time and motivation related to online learning (Salmon, 2011).

A key aspect of designing effective online learning involves providing ample opportunities for collaboration and communication between students as they work with and process new content (Moore, 1993, 2012; Falloon, 2011; Salmon, 2011; Kim et al., 2019). Carefully designed collaborative learning opportunities allow students to interact with each other creatively as they explore and process the content (Moore, 1993, 2012; Salmon, 2011; Kim et al., 2019). These types of experiences promote meaningful dialog amongst students, creating virtual connections that can push and nurture each student’s learning (Moore, 1993, 2012; Falloon, 2011; Salmon, 2011, 2019; Shearer, 2011; Huang et al., 2015). In particular, instructors want to create open-ended spaces where students can explore concepts, share their thinking or emerging understanding and receive timely feedback from their peers and the instructor (Falloon, 2011; Salmon, 2011, 2019; Huang et al., 2015). Facilitating an environment where students are free to and expected to communicate with one another helps students who are learning remotely develop relationships and a sense of community, thus lessening the sense of distance in an online environment (Falloon, 2011; Salmon, 2011, 2019; Moore, 1993, 2012).

Supervising Student Teachers and Online Supervision

Student teaching is the culminating experience for all pre-service teachers allowing them full-time experience within a school to try and test what they have learned about teaching in practice (Cuenca, 2013; Feher and Graziano, 2016). University supervisors play an essential role in helping to negotiate a space that connects the university to the school, all the while helping to facilitate the students’ process of understanding, learning from, and making meaning of their daily work (Cuenca, 2013; Elfer, 2013; Thurlings et al., 2014; Graziano and Feher, 2016; Diacopoulos and Butler, 2020). Relationships are critical to gain the trust of the student-teacher and their school mentor teacher (Cuenca, 2013; Elfer, 2013; Liu et al., 2018). Investing in a relationship with the student is essential as part of the feedback process that supervisors employ will guide student teachers as they reflect on and learn about their work as teachers (Thurlings et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2018; Diacopoulos and Butler, 2020). This process also involves helping teacher candidates learn to make sense of their teaching within a particular environment and recognize the different pulls and pressures that may impact the way they are performing in the classroom (Diacopoulos and Butler, 2020).

When looking at supervising student teachers in the online environment, some structural barriers need to be considered. Until the Covid-19 pandemic, there were no universal online teaching experiences that all teacher preparation programs provided for their students and supervisors. Most programs do not provide students or supervisors with any exposure to or experience teaching online (Feher and Graziano, 2016; Graziano and Feher, 2016; Rice and Deschaine, 2020). This becomes critical while working to provide feedback in an online learning environment. These environments require a different way of thinking about planning lessons and engaging students, highlighting a lack of knowledge and experience university supervisors possess (Feher and Graziano, 2016; Graziano and Feher, 2016; Rice and Deschaine, 2020). In online settings, instruction and supervision rely on clear and consistent communication, a focus on how the learner may be receiving and interpreting content, and ways to help students see the responsibility they have in online settings in processing their learning (Graziano and Feher, 2016; Liu et al., 2018; Rice and Deschaine, 2020). The key is to discover and use methods that help both the supervisor and pre-service teachers look at and explore the lesson and its impact using all tools available in a virtual setting (Liu et al., 2018).

Methodology

In this paper, we employed “collective self-study” (Samaras and Freese, 2006; Samaras, 2011) to examine our experiences while transitioning to remote learning with pre-service teachers. This form of systematic inquiry allowed us to look critically at our work during this challenging time, generate knowledge about our teaching, and transform our practices (LaBoskey, 2004; Samaras, 2011). During this research, Crystal and Mike were both first-year assistant professors at a large public university located just outside a major city. While we taught some different courses during the semester, we both were supervising student teachers during the time of the shutdown. Self-study allowed us to share and compare commonalities in our work as well as provide objective feedback on the work we did in different courses. We were both the researchers and the researched, allowing us to engage in individual and collaborative inquiry simultaneously (LaBoskey, 2004).

To critically examine our practices, we used a variety of qualitative methods to generate and collect data. Our data included: reflective narratives about our experiences, a review of evaluations of online lessons, reflective journals kept during the semester, documents we created and shared for our class sessions, and several virtual meetings where we discussed our insights into our work. Additionally, we both completed a written reflective interview in response to prompts that asked us to examine our work as teacher educators and student-teacher supervisors during this global shutdown. Each of these captured the complexity of our work, allowed us to interrogate our practices, examine them critically, and identify places for improvement and a more profound understanding (LaBoskey, 2004).

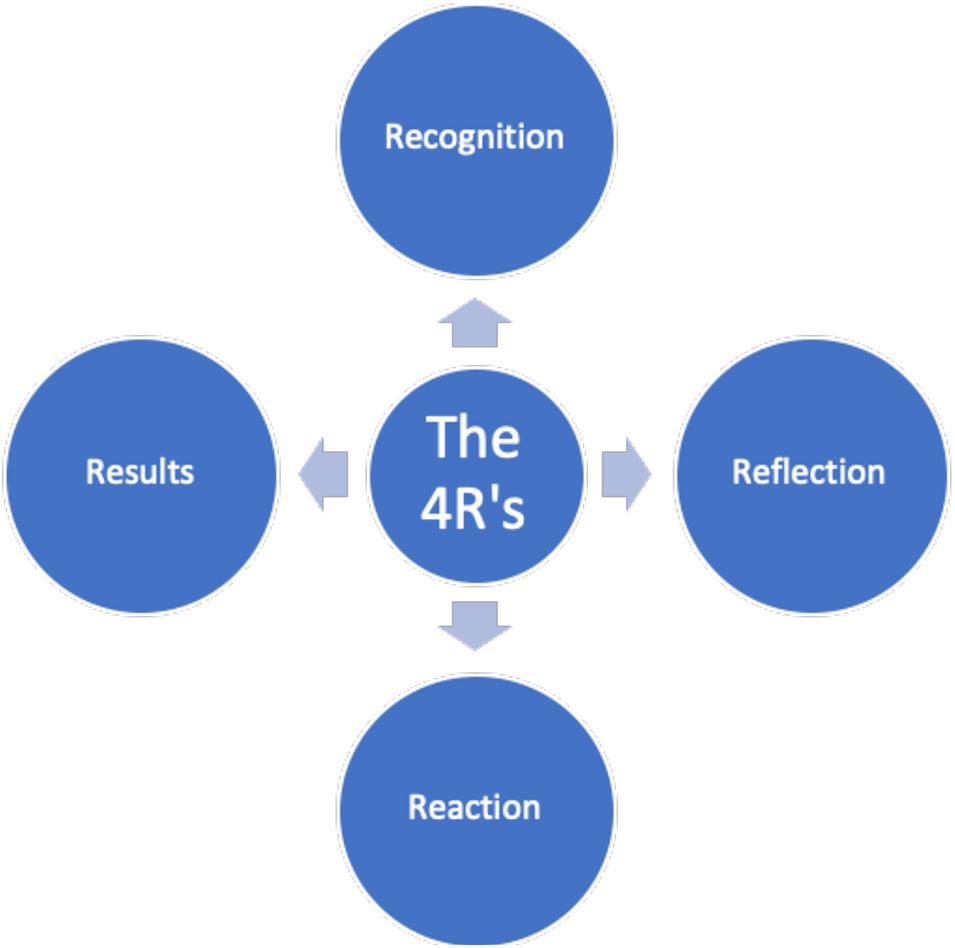

We analyzed the data inductively using the constant comparative method (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) and looked for emerging themes (Bogdan and Biklen, 1998). As part of this review, we developed and used a Four R’s Professional Inquiry Model (Recognition, Reflection, Reaction, Results) based on Moore’s (2012, 1993, 1989) work to help make meaning of our findings. In this model, teachers recognize students’ needs and adjust instruction, reflect on lesson components, structure, and learning environments, and react by adapting and modifying practices. Through those actions, we see results that demonstrate ways we moved our practice to work toward a common goal with clear learning intentions. This model helped us make meaning of our data by examining the challenges we faced, the decisions we made, and the ways we found growth opportunities. Garrison (2000) might see this as a way we used theory to understand our practice better and make thoughtful and meaningful teaching decisions. As we worked to understand our teaching during this time, we noted ideas that could enhance our work as teacher educators. Additionally, based on our experience, we posit that this same model could be used by other educators to evaluate their work in both virtual and face to face settings.

For this paper’s intent, we wanted to obtain an informed understanding of the learning environments created and presented by the challenges of Covid-19. The Four R’s model, as shown in Figure 1, helped us to process our thinking during the semester and examine further the core themes that emerged from the analysis of our journals, student work, lesson plans, reflections, and collaborative reflective interview.

As part of our review, we examined ways our lesson planning process evolved, responding to successes, challenges, and student needs during continuous changes. We also noted how our supervisory practices developed, working to support student teachers as they, too, made this immediate transition to remote teaching. In particular, we note a deepening understanding of what it means to teach and learn. Throughout our paper, we interweave our narratives to describe our findings. This is deliberate as it allows us to authentically share our work as teachers during this challenging time and helped us to grow our understanding of our practices.

Findings

Moore’s (2012, 1993, 1989) pedagogical theory in distance education influences the understandings and perceptions regarding remote learning. Moore’s original model examines (1) dialog between the instructor and the learning, (2) flexibility of structure, and (3) learner autonomy. We needed to consider the pedagogical theory of transactional distance or communication space as we examined the impact of the Covid-19 shutdown on our work as educators. Huang et al. (2015) expanded Moore’s work by including interpersonal closeness among learners and between the instructor and learners when examining transactional distance. Using this to structure our inquiry, the following themes emerged from our data: Innovation in Survival Mode, From Supervision to Collaboration, and Igniting Creativity.

Innovation in Survival Mode

Changing instructional methods can be a daunting task, especially when face to face teaching is the preferred method of delivery. Not only did this create panic among education students, but professors as well. We all went through a process that included feelings of doubt, anxiety, and panic (Crystal’s Reflection, June 2020).

On March 10, 2020, we all received an email from our university president that stated that our university would close and we would move to alternate modes of instruction for the remainder of the semester. As Mike reflected, “On March 10, 2020, I don’t think that I really knew what was happening and how it would impact my work and my life.” When examining our thoughts and work just as things were shutting down, we noted a theme emerging that we simply call “Innovation in Survival Mode.” This theme reflects our feelings of uncertainty, doubt, and fear related to our teaching and the many other factors that were impacting our students and ourselves as we just tried to make things work during this critical moment. This theme highlights the need for innovation, reflection, openness, and understanding as educators during times of significant change. In particular, we had to find ways we could reimagine instruction and connection during these unprecedented times. Moore (2012, 1993, 1989) might see this as our way of reacting to the great transactional distance caused by the circumstances imposed on our work and lives by trying just to make everything continue to function.

Reimaging Instruction

During this time, we had to be okay not knowing how things would work out, and not knowing how to answer almost any questions. As Mike reflected, “How do I take my EGP 400 course that I worked so hard to make interactive and push it online? and How can I support and supervise my student teachers?” Crystal noted, “Not only did students need to transition from campus housing to home environments, they had to wrap their heads around not being within a campus setting nestled among academia support systems.” The rapid shutdown indeed increased the distance everyone perceived at this time. Despite all of the changes, we felt a responsibility and saw an opportunity to innovate to help keep things functioning for our students and us.

We had to process uncertainty quickly, evaluate how it could work with our students, and make rapid adjustments to our practices. The rapid changes caused us to actively tinker with our understandings, beliefs, and practices (Martinez and Stager, 2013). We were testing and iterating all in real-time, challenging the way we approached our work. Mike journaled.

All of this is causing me to think about the value of learning activities and makes one wonder if you really do need to do everything in person all the time. Is there a place for sharing information and having students do something with it on their own time? Can learning only happen in the set period we give them? (April 2, 2020).

During this period, students shared feedback, challenges, and successes with us, helping us reimagine and refine our work. Moore (2012, 1993, 1989) and Shannon (2002) might say we worked to develop flexible structures that were responsive to our students’ needs, ourselves, and ultimately met the goals of our courses. While teaching in survival mode, we noted an increase in our willingness to make rapid changes rather than when we were teaching in a traditional model. The circumstances caused us to invite more feedback and ask how things were going, more than we had previously. In this sense, survival mode teaching appeared to decrease transitional distance in some instances.

We had to accept that our teaching methods had to change immediately to accommodate student learning online. Remote learning required a shift to asynchronous learning or some form of hybrid instruction. This required us to learn about the potential of new technology applications that might motivate our students (Salmon, 2011). However, there were glitches, as Mike wrote in his journal on April 3, 2020,

There were the technology glitches related to the asynchronous portion of EGP400. Apparently, Edpuzzle was freezing for some students, and the Discussion board was not operating - I guess when you put conditions on it like they have to respond to 3 others, D2L won’t allow students to respond first. Live and learn. I resolved the issue with the discussion board, but Edpuzzle was a mystery because it worked for me, and it appears as if some students were able to complete the work.

Our class structures needed to be flexible enough to allow for rapid changes when what we had planned fell flat or simply did not work. Moore (2012, 1993, 1989) might see this is a way we tried to mitigate any distance that may have been unintentionally created by design decisions we made as we transitioned to remote teaching.

The immediate shift to online instruction made us feel as if we were building the ship as we were flying it. Mike reflected, “Small tasks like having students turn and talk or talk around the table were seemingly impossible. Anything that took 5 min in the classroom would take 15 online….” When teaching in a more traditional classroom, the instructor can continuously read the room and drive the pace, guiding students to move on or change course immediately; this is impossible to do as students are working autonomously. Plans we had that we knew would be successful in a face to face setting would simply not work online. Structuring online courses requires a thoughtful design that ensures that all tasks and assignments are purposeful and framed explicitly.

As everything changed, we both found that we needed to be mindful of essential learnings as we worked on lessons for our courses. Online learning places much responsibility on the learner. It is critical that we, as instructors, know what experiences will support students in developing the essentials skills and knowledge for our courses. To do this, we had to identify clear goals for each class session, work ahead to create content, video recordings, and ensure all assignments were posted and ready for students. Being prepared and ready to teach looked different, just as the learning experience looked different for our students. Garrison (2000) might see this as a way we started to reimage our role as teachers in online instruction.

The changes we made required that students take greater ownership of their learning and the ability to monitor, manage, and process remote learning experiences. This shifted the learning structure that a majority of our students had come to expect in their college courses. In survival mode teaching, self-directed learning became an essential component. Students needed to examine assignments, allot time for completion, and study outside of the classroom without direct access to or supervision by a professor. Giving students autonomy did not prepare them for additional responsibility (Moore, 2012, 1993, 1989). Mike journaled, “I had them (students) work in breakout rooms on a collaborative jigsaw activity, but I noticed some confusion over the directions and the students’ ability to process and make sense (of directions and content)” (April 1,2020). These students then opted to do nothing, rather than try to problem-solve or ask for help.

Additionally, students who were accustomed to face-to-face learning immediately had to adjust to new structures online. Crystal reflected, “In this age of technology-rich environments, one might assume that all students like to learn through digital activities, but many students commented on their dislike of such engagement methods.” Moore (2012, 1993, 1989) might see this as a way our structures were not working for our students. Whereas we assumed “digital natives” would figure things out quickly, we found that we needed to be extremely specific and explicit in our directions to guide students through remote learning. Being open to this need led us to refine the ways we presented learning activities and reevaluate the specific value of each to ensure it met particular goals.

Reimagining Connection

Crystal and Mike also both taught and supervised student teachers during this semester. Survival mode supervision required us to modify everything that previously worked in the brick and mortar classroom environment. As Crystal reflected,

Before Covid-19, we used the Danielson Framework to evaluate student teachers in the classroom setting. Feedback, a tool used in classrooms through direct conversations, had to move online … Not only was this a change in the process, but it also now involved feedback on remote learning sessions through Zoom or other online platforms.

In order to survive the moment and help our student teachers, we collectively explored ways to create digital learning opportunities for K-8 students. This created a space where we were simultaneously learning with our students and providing feedback to them on their remote teaching. Survival mode encouraged us to create spaces where student teachers could share, reflect on, and talk about their work with K-8 students. We started to look at lessons in a 360-degree fashion, talking about the planning process, how it was presented to students online, how students reacted and responded to the online assignments, and examine samples of student work. While all of these things should happen in theory, the circumstances created by working in survival mode seemed to give us more opportunities to dig into each student’s work. As Mike noted, “I am enjoying the ability to spend some more one on one personalized time with each intern talking about their teaching, how they are thinking through their plans and the ways that they are managing their relationships with their mentors and other colleagues” (personal journal, April 10, 2020). Moore (2012, 1993, 1989) might see this as another way we minimized transactional distance with our student teachers while supporting them in learning from their experiences as virtual educators (Cuenca, 2013).

We could spend time facilitating this work in our seminars; however, that individualized support was difficult to provide in our other courses, each with approximately 30 students enrolled. Mike wrote about this challenge in his journal on April 10, 2020,

The university talked about academic integrity and rigor while also trying to be sympathetic to students’ needs. The challenge is when I reach out to students, I only hear back from a few … but if I do not hear anything, I am not sure what to think - especially if they submit “work” that checks the box but really doesn’t meet expectations.

Many of our students were not prepared to manage their learning in a space that provided them with less everyday interaction with their peers and their professors. Mike reacted to this in his journal, noting, “I am struggling with knowing if I am giving too much work, not enough work or just work … but I sense that my students are struggling” (April 14, 2020). We needed to reinvent ways to check in with students, get more specific feedback, and invite opportunities for them to seek out assistance as needed. Moore (2012, 1993, 1989) would note that we needed to adjust the structure of our courses to try and match the needs of our students and their ability to manage and regulate their learning.

We recognized that our roles had to change to support students as they rapidly moved to remote learning. Students, too, were just learning to survive these new educational and life conditions. We had to facilitate spaces where students could learn to become comfortable with different ways of interacting with the content, their classmates, and their professors. The new methods of instruction and supervision resulted in us finding ways to increase collaboration among student groups during each of our class sessions. We used Zoom Breakout Rooms, discussion groups, Google Docs, Padlet, Flipgrid videos, and other tools to promote collaboration with peers or teachers. Moore (2012, 1993, 1989) might see that by doing this, we made changes to our structures that helped support students as autonomous learners by encouraging dialog in multiple ways. Crystal put it this way in her reflection:

When asking questions in class, it is rare to hear from all 30 students. However, when using a discussion board online, we were fortunate to read and receive insightful comments regarding readings and discussion posts. This allowed a majority of our students to have a voice, something that did not happen in face-to-face situations. Shy students that often did not participate flourished in this environment.

Rethinking ways students could communicate and share their learning demonstrated a growth opportunity for our teaching. Some online tools like Flipgrid allowed us to see and hear more students’ voices and ideas than we would typically in a more traditional setting. As Mike reflected, “While the students did not seem to interact as positively in breakout rooms - often complaining about work or their lives, they did respond to each other on the Discussion boards and Flipgrid.” Students’ responses to one another demonstrated that they had actually “heard” what their classmates said, which is also often lacking in discussions in face-to-face settings. It was necessary to take advantage of this promising aspect of online instruction and infuse these types of learning opportunities creatively into our teaching.

As we worked to recreate communication spaces in our online learning environments, we recognized the importance of the types of questions we asked and the directions we gave. In a face to face setting, teachers can ask quick check questions or walk around the room, scan student work, listen in to groups, and monitor progress to assess how things were going for students. Teachers and students both had to make sense of this new environment and construct new ways of acting and interacting with each other to develop new knowledge (Martinez and Stager, 2013) and successfully survive our current circumstances. Moore (2012, 1993, 1989) might see the challenges in the format as a factor that increased transactional distance, while our efforts to use multiple platforms to support connections was a way we reviewed our structures to decrease the transactional distance. Survival mode teaching required that we were comfortable with continuous learning and iteration, understanding that our students had to be open to these factors as well.

From Supervision to Collaboration

Reimagining our roles as student teaching supervisors occurred in many phases, beginning with the responsibility of counseling our students to remain calm and try to make sense of the situation. Mike wrote, “In my conversations with the interns, many are really experiencing a loss related to schools closing until June, not having the ‘solo’ week they had thought about and then all of the changes to graduation, etc.” (personal journal, April 21, 2020). This required additional conversations with our students and their mentor teachers to create and facilitate new learning spaces and opportunities. However, not one of us had ever truly experienced anything like this before. Students, mentors, and professors were figuring this out together, changing the dynamic from one of mentoring and supervision to one of collaboration between all parties.

The transition to remote learning environments required a shift in thinking for student teachers, classroom teachers, and professors. As Crystal reflected, “I recognized the necessity to support student teachers as they … developed lessons that would typically be taught face-to-face. Together, we had to search for platforms that would support learning among elementary students.” This takes creativity, time, and task management; three areas that are not always accessed because of other commitments. Ted Dintersmith (2018) might see this as a way the circumstances forced us to challenge the rigidity of practicing what was always done in schools. Many use technology in their instruction, but not as a full-blown pedagogical method of delivery. However, as Mike noted, our student teachers faced these challenges boldly, “I am super impressed with the work that the majority of them are doing, how they are supporting their mentors and the creative ideas they have come up with for engaging their students in the online environment” (Journal, April 2, 2020). Our students were not dancing around technology or using it to add pizazz to a lesson. They were using technology as a tool to create authentic online learning opportunities for their students. In fact, during most conversations with mentor teachers, they noted ways that the student teachers were helping and supporting the “mentors” as everyone was learning together. Typical dynamics between the supervisor, mentor teacher, and student-teacher were shifting as we were all collaborating and learning from our practices together.

Transitioning to a remote learning classroom made us realize that we needed to support student teachers as they transitioned to online teaching. Together we had to explore ways to create online lessons that helped K-8 students to be self-directed learners. Something new to all of us. As Crystal reflected, “To ensure students were rewarded with appropriate lessons during remote teaching, pre-service teachers had to take a deep dive into pedagogical elements that supported online learning. Furthermore, in order to support student teachers, I had to become familiar with pedagogy that would engage student learning on digital devices.” We worked with our students to search for applications that would support learning among elementary students. These interactions yielded productive discussions over email, text, phone calls, and Zoom meetings.

Student teachers needed to feel comfortable taking risks as they challenged their conventional thinking about classroom lessons and their position as student teachers. Mike reflected, “Most of the interns were trying to make sense of this experience based on where they had been in a typical Face to Face setting - for ex. to take over reading, or math, etc., I felt as if they now needed to have a chance to find spaces for themselves, highlight their talents, and take on the challenge.” Through our work, we encouraged students to be comfortable with learning from their practice, which we encouraged all the time but seemed more natural now since everyone involved was in the same boat. Our students were on an equal footing with their mentors and us as we explored how to move all types of learning experiences online. Moore (2012, 1993, 1989) might see that being collaborators impacted the way we structured our seminars, communicated with each other, and certainly helped to lessen the transactional distance between our student teachers and us.

Supporting these types of shifts required an open dialog exploring questions related to pedagogy, reaching students, core instructional goals, and learning. We had to be comfortable and prepared to work with our students in this new setting, acknowledging the challenges and knowledge gaps that our students experienced (Feher and Graziano, 2016). As Mike wrote,

I have really enjoyed these conversations with the interns, as I feel like they are demonstrating some creativity and real willingness to try and think outside of the box, given the circumstances. But this one was - well - depressing. While there was nothing inherently wrong with her lesson, and everything she shared made sense and demonstrated the best that she could offer to her students, given all of the constraints, she was still upset. She said, “I feel like I’m not teaching them. I could be doing so much more. I should be doing so much more” (personal journal, April 14, 2020).

We could relate to these feelings deeply since we, too, were experiencing this with our classes. While it was clear we were all working autonomously to meet the varied needs of our students, the communal bonds we formed with our student teachers promoted a more in-depth exploration of our practices and what it means to be a teacher.

Online learning provided more opportunities for professors to engage in conversations (virtually) with students and hear more directly from each student about what they were experiencing, thinking, needing, and wondering. In a way, these conversations strengthened our connections and allowed us to become thought partners as we grappled with challenges and questions together. In this scenario, no one had the “right” answers or any answers at all. This helped to create safe spaces to try and test ideas, admit when things were not working, explore why, and make the necessary changes. The honest dialog we had was not as students and professors but as fellow teachers. This allowed us to lessen the transactional distance we were all experiencing and better individualize to meet the needs of all of our students (Huang et al., 2015).

What resulted from this collaborative adventure was a new fondness for online learning, a willingness to take risks, and the recognition that we need to try to help our student teachers develop a greater sense of agency. Pre-service teachers had to shift their mentalities from face-to-face instruction and the rewards that come with it to an online environment where one had to motivate students through a screen. We all had to reimagine what teaching could and should look like in this new environment. Mike reflected, “I had to be okay with the fact that the interns may not be ‘taking on the whole day’ and be supporting students by holding office hour (tutoring) meetings, creating online asynchronous activities, or virtual Morning Meetings.” By working together with our students, we encouraged each other to try new methods and collectively reflect on our teaching, which would not have happened in a typical semester. This is another example of how pedagogical changes we made helped reduce the transactional distance between and among our students and us. In viewing student teachers as collaborators Garrison (2000) might say we implemented changes to our structures that promoted productive authentic dialog that was driven autonomously by students’ immediate needs and interests related to their online teaching. Ultimately, this process helped us understand that it is possible to create a learning community online and focus on content delivery (Kim et al., 2019).

Igniting Creativity

Most student teachers did take opportunities and run with them. Many demonstrated creativity and boldness in the lessons they worked on, creating videos, interactive presentations, virtual field trips, and ongoing connected virtual learning experiences. The student teachers used presentation tools, virtual experiments, videos, Nearpods, Flipgrids, Educreations, screencasting applications, and many other tools. The teachers recorded audiobooks and also facilitated virtual read alouds (Mike’s reflection).

As we processed Moore’s (2012, 1993, 1989) theory of transactional distance, we noted that one way to lesson transactional distance in online teaching was to look at the interplay of structure, dialog, and learner autonomy through the lens of creativity. This involved the way we looked at our teaching and how we worked with our student teachers as they developed lessons for K-8 students. Crystal reflected, “Remote learning strategies can be engaging activities that would not work in a face-to-face environment.” The immediacy of the changes required us to change our thinking as we were tinkering with our online teaching practices. It also created a space for our student teachers to demonstrate a level of creativity and autonomy that did not exist when working with their mentors and students in the typical classroom.

Creativity and variety were crucial to the establishment of an online learning community with all of our students. Rice and Deschaine (2020) note that when guiding pre-service teachers, we need to think about instructional design rather than instructional delivery and focus on how we will build relationships with students in the online space. Crystal reflected, “The technologies available to today’s online teachers are varied and robust. However, students can become dissatisfied with their screen-mediated conversations.” As we examined our online instruction, we noted how this experience challenged our conceptions of teaching and learning. We had to identify critical skills and knowledge while exploring different modes of communication and interaction using various online applications.

While teaching never seems static, making this immediate shift to online instruction created a vibrant opportunity for authentic professional inquiry. Through this process, we had to explore what was truly meaningful to help our students learn. As veteran educators, we both had lots of knowledge of what works in a face to face setting, but little idea of how this might be designed expertly for online learning. We questioned our work and needed to construct answers swiftly to best support student understanding and growth. Mike reflected, “I had to think about what assignments were critical to helping students construct knowledge. Is busy work important just to have students identify what they “know,” or should I stick with process-oriented assignments?” Given all the uncertainty, we noted that we were generating and testing new ideas more than we ever would have during a typical semester. When looking at our plans and class structures for each week, we had to be creative and adapt to respond to the results of previous class sessions. Our student teachers were experiencing the same thing, as they worked to find ways to reach their young students and help them continue to learn. As instructors, we all needed to be thoughtful and creative about the opportunities we provided for students to interact with the content and each other.

Remote learning offered a more significant opportunity for our student teachers to demonstrate creativity and boldness in their teaching. Earlier in this article, we noted how positions equalized as we all switched to remote learning, meaning there was indeed a sense of collaboration between us, our student teachers, and their mentors. We were all working together to make things work for children. Our typical “seminar” sessions became collaborative brainstorming sessions, where students and professors shared ideas, challenges, and successes. These were truly spaces for authentic inquiry that led to creative ideas that we all felt would try to meet the needs of our students, no matter their age. In a sense, we created teaching playgrounds where we all played with different ideas, tools, and structures. As we reflected on this experience, we both noted that even though there were so many challenges and constraints, there was a sense of liberation, creativity, and opportunity that this time presented, something that we noted had not existed during previous semesters.

Additionally, our student teachers benefited from the fact that schools and districts were freed from the constraints of standardized testing. This freedom provided mentor teachers with the opportunity to allow their student teachers to be more creative and thoughtful about the types of lessons that they were preparing for their students. We noted that when we spoke with students during this time, they told us that some mentor teachers shared that they were now able to create units and learning opportunities that would have been restricted by the time given to test preparation. When reviewing our reflections on our interactions with our student teachers, while all lamented the loss of “what could have been,” they also felt that this time allowed them to explore and be more creative than they had been during the first part of the semester. As Mike journaled after a lesson conversation with a student teacher, “I have really enjoyed these conversations with the interns as I feel like they are demonstrating some creativity and real willingness to try and think outside of the box given the circumstances.” Moore (2012, 1993, 1989) might see this as a way we need to work to create more flexibility in our typical structures to motivate creative, autonomous learning.

Discussion

In this paper, we used Moore’s (2012, 1993, 1989) theory of transactional distance and a tool we call the 4 R’s to examine our work as teacher educators when the doors of schools and our university shut and all of our instruction moved abruptly online. In this model, teachers recognize students’ needs and adjust instruction, reflect on lesson structure, and react by adapting and modifying practices. Through these actions, we see results that demonstrate how we moved our practice. For our work, we looked at Moore’s (2012, 1993, 1989) critical elements of structure, dialog, and learner autonomy as we looked at our online instruction through the lens of each of the 4 R’s construct.

As a result of our examination, we found it is especially important that educators recognize ways that online teaching should be and is different from face-to-face instruction. Instructional design is instructional delivery in online education (Moore, 2012; Huang et al., 2015; Rice and Deschaine, 2020). We need to purposefully design structures that focus on relevant content and the importance of community building. Additionally, we need to provide varied opportunities for students to demonstrate personal and collaborative autonomy in their learning. However, the online learning environment cannot be static. Instructors need to be alert, responsive, and open to innovation to support online learners. This means that while there may be a plan or design for a course, especially one designed for asynchronous learning, the educator needs to check in, evaluate how things are going and be willing to change if the existing plan does not seem to be working. While we talk about being responsive and innovative in education, at times, we often do not enact these types of responsive practices in our teaching, no matter the format.

While continuous innovation and responsiveness can help to try and support students as they move through any class, we must also think about how changes impact and are received by our students. Communication is crucial to support students in online learning environments (Garrison, 2000; Falloon, 2011; Salmon, 2011). To truly be responsive, we need to engage in dialog with our students (in any format) to get a better sense of how things are progressing for them. If we modify a structure, we need to communicate our thinking to help foster learning and understanding. While this dialog is meant to keep students informed, it also reminds us of the importance of equalizing positions and fostering interactions between students and the instructor (Dewey, 1938; Lave and Wenger, 1991; Moore, 2012). While we know that sharing specific guidelines for assignments and learning activities will help ensure that teachers get quality work, it is also critical that students have voice and agency. Concerning our work, it reminds us that we need to allow pre-service teachers to have and learn to use their professional voices.

Moore (2012, 1993, 1989) reminds us that learner autonomy helps to promote self-directed learning and responsibility for learning goals. We came to see providing opportunities for autonomy also opened spaces for students to demonstrate creativity in ways that a more controlled or directed space had not. While Moore (2012, 1993, 1989) might suggest that greater autonomy increases transactional distance, we saw that, at least for our student teachers, greater autonomy spurred creativity that opened a space for professional sharing and dialog.

The autonomy that encourages creativity is not always easy for students. We know that autonomy implies increased choice; however, autonomous learners must take responsibility for their learning (Moore, 2012). Since most students are normalized to typically getting all directions and instruction from the “teacher,” self-directed learning can be very challenging for some. Students need to be self-motivated, engaged, and dedicated to learning without the direct presence of their peers or instructors to be successful in these environments. We learned that we needed to provide more scaffolds for students who were less comfortable with autonomous learning opportunities. Additionally, we noted that we needed to try and create more of these types of spaces for students in our courses so that they could come to be more comfortable with taking chances and risks while taking charge of their learning.

Implications for Practice

As we all prepare for more online learning opportunities, we must reflect on our previous experiences and look to expand our practices. When considering distance learning theory, dialog, flexibility, and learner autonomy all surface as a means for helping students self-regulate their learning. Through conversations, instructors can gage learner interest and understanding of content. Flexibility is necessary when designing learning environments; teachers will need to scaffold for learners with poor self-regulation, while also challenging learners who embrace independent learning opportunities. We feel that the 4R’s Professional Inquiry Model might provide a structure for others to reflect on their practices as well. The school shutdown experience created opportunities for us to learn about ways to integrate online learning opportunities into our teaching more effectively and be a bit more prepared for what is to come.

Educators must recognize the necessary changes in pedagogy as transitions are made from face-to-face to remote learning environments. Strategies to create community-building opportunities will help students feel connected with peers in the remote classroom environment. Additionally, students need practice with the digital tools used to foster learning; it cannot be assumed that digital natives come equipped with navigation skills. Equally important is the element of communication vital to the support of all learning environments; it has to be specific and frequent. Finally, collaboration both in the remote learning environment and among professional colleagues will encourage learning opportunities that lead to student success.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

MR and CL worked collaboratively to explore our practices using the 4 R’s and Moore’s theory of transactional distance. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Arason, S. (2019). The impact of digitisation on teaching and learning. Educ. Multidiscipl. J. 3, 102–115.

Black, L. (2013). “A history of scholarship,” in Handbook of Distance Education, ed. M. G. Moore (Abingdon: Routledge), 3–20.

Bogdan, R. C., and Biklen, S. K. (1998). Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods. Needham Heights, MA: Ally & Bacon.

Cuban, L. (1993). How Teachers Taught: Constancy and Change in American Classrooms, 1890-1990. New York: Teachers College Press.

Cuenca, A. (ed.) (2013). Supervising Student Teachers: Issues, Perspectives, And Future Directions. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.

Delen, E., and Liew, J. (2016). The use of interactive environments to promote self-regulation in online learning: a literature review. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 15, 24–33.

Diacopoulos, M. M., and Butler, B. M. (2020). What do we supervise for? A self-study of learning teacher candidate supervision. Study. Teach. Educ. 16, 66–83. doi: 10.1080/17425964.2019.1690985

Dintersmith, T. (2018). What School Could Be: Insights and Inspiration From Teachers Across America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Elfer, C. (2013). “Becoming a university supervisor: Troubles, travails, and opportunities,” in Supervising Student Teachers: Issues, Perspectives, and Future Directions, ed. A. Cuenca (Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media).

Falloon, G. (2011). Making the connection: moore’s theory of transactional distance and its relevance to the use of a virtual classroom in postgraduate online teacher education. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 43, 187–209. doi: 10.1080/15391523.2011.10782569

Farjeon, D., Smits, A., and Voogt, J. (2019). Technology integration of pre-service teachers explained by attitudes and beliefs, competency, access, and experience. Comp. Educ. 130, 81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2018.11.010

Feher, L., and Graziano, K. J. (2016). “Online student teaching: From planning to implementation,” in Online teaching in K-12: Models, Methods, And Best Practices For Teachers And Administrators, eds S. Bryans-Bongey and K. J. Graziano (Medford, NJ: Information Today, Inc.), 109–127.

Garrison, R. (2000). Theoretical challenges for distance education in the 21st century: a shift from structural to transactional issues. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 1, 1–17.

Glaser, B. G., and Strauss, A. L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine De Gruyter.

Gorsky, P., and Caspi, A. (2005). A critical analysis of transactional distance theory. Quart. Rev. Dist. Educ. 6, 1–11.

Graziano, K. J., and Feher, L. (2016). A dual placement approach to online student teaching. Contemp. Issues Technol. Teach. Educ. 16, 495–513.

Huang, X., Chandra, A., DePaolo, C., Cribbs, J., and Simmons, L. (2015). Measuring transactional distance in web-based learning environments: an initial instrument development. Open Learn 30, 106–126. doi: 10.1080/02680513.2015.1065720

Keengwe, J., and Kidd, T. T. (2010). Towards best practices in online learning and teaching in higher education. MERLOT J. Online Learn. Teach. 6, 533–541.

Kim, E., Park, H., and Jang, J. (2019). Development of a Class model for improving creative collaboration based on the online learning system (Moodle) in Korea. J. Open Innovat. 5:67. doi: 10.3390/joitmc5030067

Korhonen, A. M., Ruhalahti, S., and Veermans, M. (2019). The online learning process and scaffolding in student teachers’ personal learning environments. Educ. Inf. Technol. 24, 755–779. doi: 10.1007/s10639-018-9793-4

LaBoskey, V. K. (2004). “The methodology of self-study and its theoretical underpinnings,” in International Handbook of Self-Study Of Teaching and Teacher Education Practices, eds J. J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. LaBoskey, and T. Russell (Dordrecht: Springer), 817–869. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6545-3_21

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Liu, K., Miller, R., Dickmann, E., and Monday, K. (2018). Virtual supervision of student teachers as a catalyst of change for educational equity in rural areas. J. Form. Des. Learn. 2, 8–19. doi: 10.1007/s41686-018-0016-6

Martinez, S. L., and Stager, G. (2013). Invent to Learn. Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom. Torrance, CA: Constructing Modern Knowledge Press.

Moore, M. G. (1989). Three types of interaction. Am. J. Dist. Educ. 3, 1–7. doi: 10.1080/08923648909526659

Moore, M. G. (1993). “Theory of transactional distance,” in Theoretical Principles of Distance Education, ed. D. Keegan (New York, NY: Routledge), 22–38.

Moore, M. G. (2012). “The theory of transactional distance,” in Handbook of Distance Education, ed. M. G. Moore (New Jersey: L. Erlbaum Associates).

Rice, M. F., and Deschaine, M. E. (2020). Orienting toward teacher education for online environments for all students. Educ. Forum 84, 114–125. doi: 10.1080/00131725.2020.1702747

Ruggiero, D., and Mong, C. J. (2015). The teacher technology integration experience: practice and reflection in the classroom. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. 14, 161–178.

Ryan, M. (2017). Disrupting professional development structures in schools by inviting teachers to design their own learning: an elementary principal conducts practitioner action research. Plan. Chang. 48, 43–65.

Samaras, A. P. (2011). Self-study Teacher Research: Improving Your Practice Through Collaborative Inquiry. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

Samaras, A. P., and Freese, A. (2006). Self-study of Teaching Practices: A Primer. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Shannon, D. M. (2002). Effective teacher behaviors and Michael Moore’s theory of transactional distance. J. Educ. Lib. Inf. Sci. 43, 43–46. doi: 10.2307/40323986

Shearer, R. L. (2013). “Theory into practice in instructional design,” in Handbook of Distance Education, ed. M. G. Moore (Abingdon: Routledge), 251–267.

Keywords: Covid-19 pandemic, theory of transactional distance, online teaching, online student teaching, collective self study, teacher education, reflective teaching

Citation: Loose CC and Ryan MG (2020) Cultivating Teachers When the School Doors Are Shut: Two Teacher-Educators Reflect on Supervision, Instruction, Change and Opportunity During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Front. Educ. 5:582561. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.582561

Received: 12 July 2020; Accepted: 19 October 2020;

Published: 11 November 2020.

Edited by:

Leslie Michel Gauna, University of Houston–Clear Lake, United StatesReviewed by:

Balwant Singh, Partap College of Education, IndiaMaria Antonietta Impedovo, Aix-Marseille Université, France

Copyright © 2020 Loose and Ryan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michael G. Ryan, bXJ5YW5Ad2N1cGEuZWR1

Crystal C. Loose

Crystal C. Loose Michael G. Ryan

Michael G. Ryan