94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 28 September 2020

Sec. Leadership in Education

Volume 5 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.00145

This article is part of the Research TopicAcademic Advising and Tutoring for Student Success in Higher Education: International PerspectivesView all 14 articles

The Higher Education Academy (2015) highlighted attainment alongside access, retention and progression as key areas of foci in order to fulfill the aspiration to provide all students with the opportunities and support required to succeed in Higher Education (HE). Although previous research into academic advising has focused on the impact upon student satisfaction and retention, the impact upon attainment is underexplored. This research aims to explore the extent of the relationship between advising and attainment and answers the call by bodies such as Advance HE (formerly the Higher Education Academy) to recognize that academic advising is vital to student success. This research provides a contribution to the body of knowledge around academic advising, in the form of a case study undertaken to identify the impact of academic advising on student attainment at Sheffield Hallam University. A focus group and questionnaire were employed to gather data from final year undergraduate students at Sheffield Hallam University. Findings indicate that the impact of academic advising on attainment is both explicit and implicit, with support in areas beyond academic studies having a significant impact on student experiences. In addition this research also questions the perceived meanings of attainment in HE and proposes that attainment should be viewed as holistic attainment whereby students are developed as a whole, better enabling them to deal with the HE environment and beyond rather than being limited to academic numerical attainment.

Advising and tutoring have long been seen as critical to student success, persistence and retention (Drake, 2011). However, the impact of academic advising on attainment, has often been overshadowed by a focus on the process and models of advising and student satisfaction rather than the wider impact that it can have (Light, 2001; Hemwall and Trachte, 2005; Propp and Rhodes, 2006; Campbell and Nutt, 2008).

Alongside this the Higher Education (HE) environment is changing. Societal shifts toward a consumer led society are resulting in some students behaving as consumers and equally, some universities perceiving students as consumers (Woodall et al., 2014). Impacts include the marketization and massification of HE (Molesworth et al., 2011; Tight, 2017) with universities focusing on student attainment The Higher Education Academy (2015) and employability (Kalfa and Taksa, 2015) in order to satisfy student aspirations and expectations. With this, many HE institutions (HEIs) are reviewing their approach and model of advising, viewing a personalized approach to learning and support as critical to the success of the student and overall strategy of the university. Sheffield Hallam University has undertaken a number of reviews of academic advising from 2015 to present with an increasing emphasis on the value of academic advising. As strategic emphasis grows, this case study aims to give an insight into the extent of the relationship between advising and attainment and identify the critical success factors in achieving high quality and effective advising.

A case study of the advising approach being implemented by Sheffield Business School at Sheffield Hallam University shall be utilized. This will facilitate an examination of the features of academic advising delivery and the impact upon student attainment. Research was undertaken with final year undergraduate students in Sheffield Business School in an attempt to understand the student perspective on the role of advising and attainment.

Academic Advising implies a singular purpose, to advise students on academic matters, yet descriptions of multiple definitions extend the role beyond this. Gordon et al. (2008, p524) define academic advising as:

“a series of intentional interactions with a curriculum, a pedagogy, and a set of student learning outcomes. Academic advising synthesizes and contextualizes students’ educational experiences within the frameworks of their aspirations, abilities and lives to extend learning beyond campus boundaries and timeframes.”

In essence good advising should help students understand the HE environment in which they are operating and aid identification of skills to enable them to manage their own learning and future aspirations. Cuseo (n.d.) supports these assertions by defining an academic advisor as the individual who:

“helps students become more self-aware of their distinctive interests, talents, values, and priorities; who enables students to see the ‘connection’ between their present academic experience and their future life plans; who helps students discover their potential, purpose, and passion; who broadens students’ perspectives with respect to their personal life choices, and sharpens their cognitive skills for making these choices, such as effective problem- solving, critical thinking, and reflective decision-making” (Cuseo (n.d.), p15).

What is clear is that high quality advising goes well beyond support related to academic issues and has the potential to build social and emotional wellbeing, future employability and the development of a collegial working environment (Small, 2013). Similarly, Drake (2011) highlights the importance of advisers in not only guiding students through their academic journey but also in supporting decisions about their future careers. What emerges in this approach is the notion of advisors as what Strayhorn (2015) terms cultural navigators. These are individuals who are able to assist socialization into the HE environment, aid with the navigation of the HE maze including developing the academic skills and knowledge to succeed and guiding them to make thoughtful decisions about future careers (Drake, 2011).

Previous research into advising and tutoring has focused on a number of different strands and foci. Some research compares staff commitment to the role (Stephen et al., 2008), whilst others compare the position of the tutor in relation to curriculum and professional support services and advisors (Earwaker, 1992; Wheeler and Birtle, 1993; Laycock and Wisdom, 2009). Others have taken a historical perspective and traced the progression from the Oxbridge Tutor (Ashwin, 2005) to Personal Development Tutor (Strivens, 2006). The commonality here is a focus on the process of advising rather than the impact. One of the first models to draw links between institutional features such as academic advising and student outcomes was Tinto’s (2007) model in which Tinto identified the relationship between the HEI and the student as a defining factor in student achievement. Habley (2004) clarifies this further by stating that academic advising is one area that institutions can utilize to formalize and integrate quality exchanges between students and the academic environment.

The formalization of academic advising manifests in a number of ways, from prescriptive advising in which the emphasis of responsibility falls on the advisor to developmental advising where there is a focus on the student’s needs as a whole (Earl, 1988). A middle ground can be seen with Glennen’s (1976) Proactive Advising in which Glennan sought to blend advising and counseling through the preemptive provision of information before students requested it whilst also developing relationships with students. Practice within the case study of Sheffield Business School has predominantly been a professional services model (Earwaker, 1992), with Academic and Professional Advising seen as external to the curriculum in line with Glennen’s’s (1976) Intrusive Advising model in which tutors initiate contact with students at critical points throughout their time at university. Perhaps reflective of the changing nature of HE, the 2017/2018 academic year saw development toward a more integrated approach with advising incorporated into the curriculum through a strand in employability focused modules at each level.

Attainment is defined as “cumulative achievements in HE and level of degree-class award” which are enabled through data driven practice, engendering high student expectations and promoting peer led learning (The Higher Education Academy, 2015). Similarly, Office for Students (2020) defines attainment as the HE outcomes achieved by students, such as the classes of degree awarded. Although in the advising literature, the term “student success” could be linked to attainment, it is often discussed in relation to retention and progression rather than academic attainment (Yorke and Longden, 2004). As such there is limited connection between the two concepts of advising and attainment, with only an inference of a connection in The Higher Education Academy report (2015, p1):

Students’ sense of belonging, partnership and inclusion are essential for achieving these aims, requiring a culture which promotes and enables the full and equitable participation of all students in HE.

So far the literature on advising has highlighted the importance of academic advising in facilitating exchanges between the academic environment and students and identified the role that good advising plays in relation to understanding the HE environment, facilitation of skill identification and future employability support but what are the impacts of these interactions on attainment? A review of the current literature highlights limited knowledge of the impact of advising on attainment. To date, the literature has focused on three key streams in relation to advising impact: student success, persistence and retention (Drake, 2011).

The empirical research of Hawthorne and Young (2010) found that satisfaction with advisors and support provided by the institution significantly influenced satisfaction with the educational environment and in turn impacted upon student intentions to persist and complete their educational qualifications. These findings were replicated in Shelton’s (2003) study whereby a direct correlation between perceived level of support and retention and success was recognized. Unpicking this further, Young-Jones et al. (2013) identified that the perceived level of institutional support was influenced by the frequency of student and advisor support which led to higher student self-efficacy and study skill utilization. The idea of self-efficacy development is an interesting one which places ownership strongly with the student and indeed, NACADA defines advising as “a decision-making process during which students themselves reach their own academic potential through a communication and information exchange with an academic advisor” (Drake, 2011, p5).

Having examined four decades of research on student persistence, Drake (2011) identifies three critical interventions which ultimately link to both persistence and retention: connecting students to the institution early in their HE journey, a rigorous first year academic advising program which enables learning communities and solid academic advising. Within this there is consensus that the component parts of these interventions including supporting skill identification and skill building, the development of student self-efficacy, educating and socializing the student into the HE environment and the broadening of employability horizons (see Cuseo, n.d.; Shelton, 2003; Gordon et al., 2008; Drake, 2011), all impact upon student success (Young-Jones et al., 2013) which could by extension include attainment but such links have yet to be fully explored.

Various authors who discuss attainment view this as “educational” attainment and also more broadly refer to academic achievement linked with the process of progressing through all schooling levels (Bahr, 2008; Novo and Calixto, 2009). Other authors also discuss the development of “intellectual attainment” empowering the learning through critical understanding (Canaan, 2010) and Ning and Downing (2012) refer to attainment in terms of academic performance in which the student learning experience and environment are critical to success. More contemporary literature explores student attainment as complex and multifaceted by looking at how it is shaped by different, often competing, agendas and vested interests (Steventon et al., 2016). Yet limited literature suggests “how” and indeed if, academic advising has an impact on student attainment. So, whilst there is no question as to the imperative value of good quality academic advising; instead this research has been borne out of the institutional need to examine whether there is a correlation between academic advising and attainment.

In recent years, Sheffield Hallam University has seen a number of iterations of academic advising as the value of advising has been increasingly recognized and the university has sought the most effective strategy. In 2015 the Sheffield Hallam University (SHU) Academic and Professional Advice Framework (2015) outlined three major strands to academic advising to be undertaken by academics in the role:

i. Pastoral support including social orientation.

ii. Academic advice including student academic development.

iii. Careers / placement support.

Yet, contrasting policies and practices were seen across the university generating inconsistencies in approaches. In Sheffield Business School (SBS), the focus of this study, the SBS Academic Advisor Role Guide (Sheffield Business School, 2017) outlined the focus of the role as supporting students with planning their personal development in relation to their academic and employability skills with the pastoral support of the SHU Academic and Professional Advice Framework (2015) notably absent. Following further review, the parameters of the academic advisor role at the time of the study had evolved once more to a focus on supporting students in relation to their academic studies (Sheffield Business School, 2017), with pastoral and employability support having been separated and assigned to professional services staff as Student Support Advisors and Employability Advisors. The exception to this model is that during the second year of student study, there is an additional focus on supporting students with their search for a work placement including the academic advisor acting as a referee and giving CV guidance.

Such an approach differs to the encompassing approach identified in the literature whereby academic advisor support, carried out by the academic, includes academic, pastoral, and employability support (see Cuseo (n.d.) and Gordon et al., 2008). This case study aims to understand the impact of the splitting up of the traditional advising role elements and explore whether there is a correlation between academic advising and attainment. The research was undertaken by two academics in the department of Service Sector Management and an independently recruited student Research Assistant (RA) from another faculty in the university as part of a university funded pedagogic project into the role of academic advising and attainment.

This study has focused on seven final year undergraduate students studying in the Service Sector Management Department within Sheffield Business School at Sheffield Hallam University. Final year students were chosen based on their length of time at the university and their experience of academic advising as recipients. Furthermore, the third year of university is typically the most academically intensive for them; focusing on final year students also allowed the study to consider academic attainment at earlier levels alongside their final classification.

The students were recruited through the university’s virtual learning environment platform to enable access to final year students across the department. Self-selecting sampling was applied for this project as the students identified themselves as willing to take part in the research (Matthews and Ross, 2010; Saunders and Lewis, 2012). This is a highly effective method of non-probability sampling due to the relevancy of the cases (individuals); the participants are committed to the research and overall, this method reduces the recruitment process (Veal, 2011). There are limitations which were taken into consideration, such as the inherent bias the participants may have, as they want to “voice” their views on the research topic which could lead to the sample not being a true representation of the research population. This study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by Sheffield Hallam University ethics panel. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study and for the publication of their verbatim quotations.

A focus group was selected as the main data collection method, to elicit a deeper understanding of the student’s perceptions of academic advisors, a common and familiar topic amongst the student group (Denscombe, 2010; Collis and Hussey, 2014). The main advantages of focus groups are: they are useful to obtain detailed information about personal and group feelings, perceptions and opinion; in addition they can save time compared to individual interviews, furthermore providing a broader range of information (Saunders and Lewis, 2012). That said a particular disadvantage of a focus group is the possibility that the members may not express their honest and personal opinions about the topic at hand (Matthews and Ross, 2010).

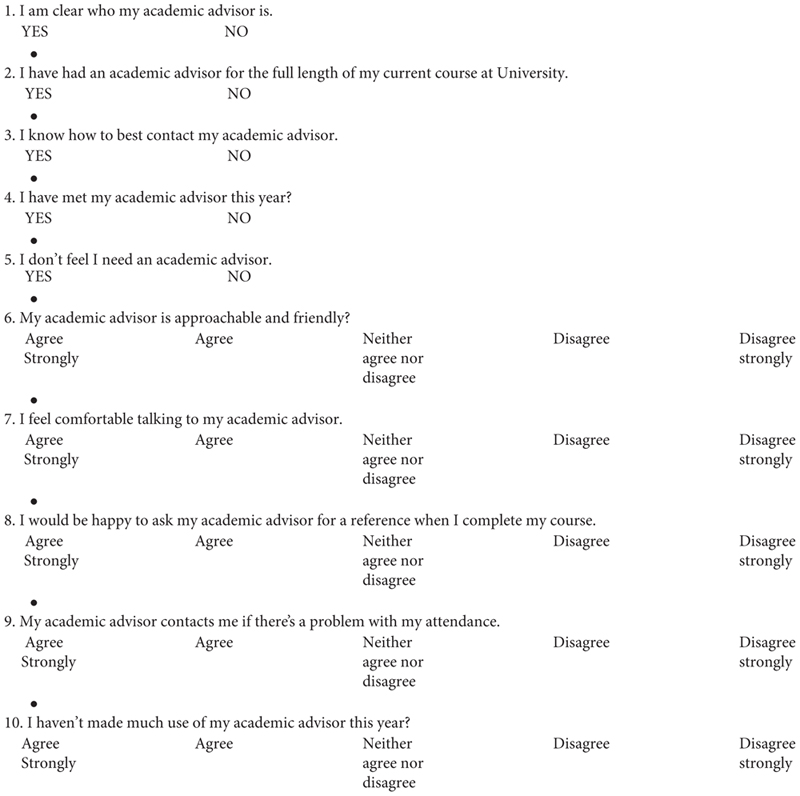

A set of focus group questions and prompts were created using the NUS (2015) as a basis. These were divided into four categories relating to the aims of this study. These categories were: (a) Frequency and Nature of Contact, (b) Academic Advice, (c) Support services, and (d) General questions. To complement the focus group, a simple 10 question survey was also administered to gain some general background to the frequency, nature and context of the support received (see Appendix 1, 2 for Survey and Focus Group Questions). This brief questionnaire was a meaningful tool in allowing us to gain a basic understanding of each participant’s experience with their academic advisor (Neuman, 2011). Furthermore, as this was completed privately by participants before the start of the focus group, it meant that students who may not have been as comfortable sharing their experiences in front of the group could still provide details of their experiences (Collis and Hussey, 2014) counterbalancing potential disadvantages of focus groups. The questionnaires were anonymized by asking students to provide their student ID as a means of identification during data analysis.

All research participants completed both the survey and focus group in a 2 h session held outside of course teaching. Seven students took part with a cross section of students from each of the four subject areas in the Service Sector Department (Food, Hospitality, Events, and Tourism). The session was held in a boardroom on the university campus to ensure privacy for the participants. To further encourage participants to openly discuss their experiences without the presence of an academic advisor from their department (who they may have had an academic advising relationship with), the session was run by a RA that had no affiliation with the department.

The facilitation of the group is critical to the success of focus groups, with the facilitator viewed more as a choreographer of the content (Matthews and Ross, 2010) encouraging the participants to “perform” by expressing their point of view to each other (Denscombe, 2010; Collis and Hussey, 2014). During the focus group, the RA verbally posed each question and participants were invited to discuss their views. Clarification on points was sought where necessary, and simple reinforcement and encouragement provided throughout to ensure the discussions remained focused on the topics (Matthews and Ross, 2010). The RA also encouraged students to engage and share their views if they displayed any signs of disengagement at any point. Occasionally, in cases where it was deemed appropriate for the study, the RA asked specific follow up questions after students had contributed a point in order to gain deeper meaning of the students experience, probing further but not leading the conversation which can often be viewed as a limitation of focus groups and the role of facilitators (Matthews and Ross, 2010; Collis and Hussey, 2014).

Following the focus group, the data was independently transcribed and anonymized prior to the academics leading the project receiving it to further protect the privacy of the participants involved. What follows is an overview of the research findings and discussion in relation to the student perceptions of the role of academic advising.

This study addressed the perceived relationship between academic advising and academic attainment in a group of third year students. In recent years there has been increased recognition of the importance of non-academic support provided by academic advisors to students, such as assistance with employability and the provision of social and emotional support (Small, 2013). The findings highlight the expectations students have of their advisors and the diversity in student academic advising experiences. Despite the model of advising followed in Sheffield Business School in which the focus of academic advising is on supporting students with their academic studies three key strands were identified from the data in relation to student perceptions of what the advising role encompasses: academic support, pastoral support, and employability support. This is in line with previous research into academic advising (see Cuseo, n.d.; Drake, 2011; Small, 2013) but it is through these strands and the stories told that we are able to unpick whether there is a relationship between advising and attainment which to date has not been fully explored.

As Habley (2004) stated, academic advising is one area in which the institution can enable quality exchanges between the students and the academic environment. Thomas and McFarlane (2018) go further to state that the true work of academic advisors is focused exclusively on student learning. With Sheffield Business School placing academic support at the heart of the academic advising role and professional services taking responsibility for pastoral and employability support; it is not surprising that academic support emerged as one of the main areas that students expected support. Participants defined such academic support as “assistance with understanding course material; and support with staff/student relationships” (All respondents). Within this, aspects of academic life discussed included course structure, predicted grades, performance on modules, academic goals for the semester, strengths and weaknesses, and aspirations for the future. In many ways this takes us back to NACADA’s definition of Academic Advising being “a series of interactions” that cover all aspects of university life (Drake, 2011).

Some students felt that the support they received from their academic advisor was tailored to them and their aspirations; whilst others argued that they felt support was “generic.” Students reporting the latter stated that their academic advisor met them in groups, rather than on a one to one basis. Although Battin (2014) indicated the potential for group advising seminars to be an effective and efficient method of advising the students who partook in this study appear to prefer the more traditional individual models of advising, particularly in the final year of study. Overall, there was an agreement amongst the participants that whether the support was tailored was based on the advisor’s temperament and interpersonal skills. Haley (2016) supports this by stating that to be an effective academic advisor, individuals must care about their students and have the ability to interact with them yet the massification of HE has created a pressure to enhance the “university offer.” For many HEI’s, including Sheffield Hallam University, this has resulted in the formalization of the advising role which includes the introduction of group as well as individual meetings (McFarlane, 2016).

With regards to attainment some students felt their academic advisor was sufficiently informed of their academic attainment such as grades and that advisors asked questions during sessions which gave them further insight into students’ achievements. However, some felt that there was a lack of consistency in support with a lack of follow up when attainment issues were raised in meetings. Collectively, based on their experience’s students felt that their academic advisor was not always the best point of contact to discuss “academic issues” due to the fact that they often lack sufficient knowledge about modules led by other members of staff. Similarly, when asked whether they felt that their advisor was helping them to reach their full potential at university there was a general agreement that academic advisors were not perceived as supporting in “uplifting grades, helping achievement in assessments, or supporting with course material.” The need for tangible rewards such as impact on grades needs to be understood in the context of a society of “want it and want it now” where instant gratification is preferred (Smith, 1987; Hall, 2011) and the increase in university fees has amplified student expectations (Budd, 2017).

Although McFarlane (2016) states that an essential part of advising is to keep the conversations going, the emphasis in this study appears to be on the academic advisor leading and initiating the conversations with students. Conversely, Young-Jones et al. (2013) place the responsibility on the students to keep the academic advising conversation going and those with stronger study skills and higher self-efficacy more likely to engage in, and see the tangible and intangible benefits of such activity. Indeed, several of the participants within this study did reflect beyond the tangible impacts of advising to acknowledge that the emotional guidance received from an academic advisor did support academic attainment and thus underpins the idea of seeing attainment from a more holistic perspective. Some students reported that their advisor played a key role in keeping them focused and helping them to remember their goal during periods of stress. By acting as a buffer against stress, some students reported coming away from meetings feeling “refreshed, inspired and motivated.” This supports NACADA’s definition of advising as “a decision-making process during which students themselves reach their own academic potential through a communication and information exchange with an academic advisor” (Drake, 2011, p5). Here, the student takes ownership of their own learning experience and the advisor facilitates “the students rational processes, environmental and interpersonal interactions, behavioral awareness and problem-solving” (Crookston, 1994, 2009).

Although the focus of the academic advisor role at Sheffield Hallam University is on supporting students with their academic studies, most students reported that they did not feel that their academic advisor was the best point of contact for “academic purposes” and that instead there was other greater value in the academic advising relationship. This supports Drake’s (2011) discussions that although academic advising has long been seen as critical to student success, persistence and retention; it goes beyond supporting academic studies and is about “building relationships with our students, locating places where they get disconnected, and helping them get reconnected” (Drake, 2011, p8).

In addition to academic support, pastoral support is seen to be an integral part to the students experience in HE (Cahill et al., 2014). Although the Sheffield Business School policy states that academic advisors are there to support students on academic and professional matters and that Student Support Advisors and associated services provide support on pastoral matters, the importance of pastoral support from the academic advisor was evidenced in the data collected. Quantitative data from the questionnaire showed that all students, regardless of whether they had a positive or negative relationship with their advisor, felt that having an academic advisor at university was important. When asked to discuss this further during the focus group, the students expressed that this importance was largely for pastoral reasons with one student summing this up by stating: “It might be worth changing the name from ‘Academic Advisor’ to ‘Academic and Welfare Advisor’.”

This supports the predominant view shared by the participants that the academic advisors were often a first point of contact for any personal issues they were facing. With students facing increasing pressures of balancing living, studying and working, universities are becoming a “melting pot” of critical incidents that often culminate in personal issues. Academic challenges, increased responsibilities and living away from home added to the fact that 75% of mental health problems are established by the age of 24 (Mental Health Foundation, 2018), has led to 1 in 5 young adults suffering from a mental illness and 20% of students being treated for a mental illness (Skyland Trail, 2018).

The majority of participants expressed satisfaction with the relationship they had with their academic advisor and reported various examples of the pastoral support which they received including support with motivation during stressful periods, helping achieve a work life balance and discussing personal and health related issues. One student reported that “I was in hospital and I had an exam, and my academic advisor was trying to get an extension for me.” whilst another reported further pastoral support “I approached her by email, and we were talking for 2 hours, about personal stuff.”

Despite institutional protocol being to refer students on to appropriate support services, there is evidence that many students are turning, and returning to academic advisors over the course of time in part due to the relationships of trust that they have built (Hybels and Weaver, 2009; Sims, 2013; Heikkila and McGill, 2015) and also in part due to the time lag between referral and the receipt of further support from wellbeing services (Buchan, 2018). What is not being disputed in this research is the value of the professional service in supporting students but that the simplicity of the referral system does not reflect the complexity of many student issues. The outcome of this is that the academics continue to undertake the three aspects of advising outlined in the literature including pastoral care (see Drake, 2011 and Small, 2013).

However, others felt disconnected with their advisors stating that “All he does is send me to other people!.” This raises a critical issue in the role of the advisor whereby there is a delicate balance between failing to build a relationship of trust which fosters the ongoing conversations that are so important (McFarlane, 2016) and stepping into a role in which advisors are not trained to do. Despite evidence of academics “bridging the gap” between support services, this is not a pre-requisite of the role and academic advisors need knowledge of centralized support services is key and to be sensitive when referring students on to other services so as not to be passing them on and remaining compassionate (Grant, 2006).

A further aspect relates to the way student feel acknowledged and integrated within university, especially in providing a smooth transition from pre-university life. This aligns with Straythorn’s (2015) concept of cultural navigators in which academic advisors play a key role in socializing students into the HE environment and creating a sense of belonging. This integrative approach should not be underestimated in terms of academic advising as students can often be ill-equipped to deal with the HE environment and the multiple demands of living away from home, managing workload and working. As such academic advising needs to reflect these individual needs (Thomas and Hixenbaugh, 2006). Not uncommon is the support that students require not only to operate in the university environment but also the professional environment whether that be undertaking work experience or attending an industry event. One student reflected upon the support given to them during their work placement:

“During my placement year, I was feeling quite homesick, and I mentioned this in a Skype group session with my academic advisor. And she asked me to move the laptop somewhere more private so she could talk to me about how I was feeling.- She helped me keep my goal in sight.”

The provision of such a responsive and supportive advising environment can do much to enhance the student experience. Through identifying and overcoming problems, advisors are able to help improve retention, progression and completion and in turn increase attainment.

In line with the literature, the data supports the role that academic advisors play in supporting student employability skills and guiding career decisions (see Cuseo, n.d.; Gordon et al., 2008 and Drake, 2011). The importance of this area of support is highlighted by Lynch and Lungrin (2018) who state that career opportunities after graduation remain one of the top concerns for students.

The participants of this study outlined employability support as encompassing guidance with writing job applications, succeeding in interviews and providing references. Students also felt that the academic advisor should be someone who can mentor them in professional skills through being an individual who has relevant industry work experience. Although mentoring has been proven to have a positive impact upon student success (see Foen Ng et al., 2012), just as with pastoral support, academic advisors are often not trained in this capacity and therefore such a student expectation is not always attainable. Academic advisors are, as we have seen, positioned as the face of the university and play a vital role in linking the student and the institution (Habley, 2004). However, they are not intended to be the end point of the support process and instead are the start in which they play a vital role in signposting students to other specialist services including employability support. Despite some students reporting expectations for employability support to be delivered by the academic advisor, many students reported great value in being directed to other support offers, as illustrated by this response:

My academic advisor referred me to the careers service which I knew about but I didn’t know some of the services that they offered, we did psychometric testing and assessment day simulations, I thought they just give you blanket advice on what to do in those situations, not actually run through them. And my academic advisor highlighted that to me.

Here, a knowledgeable academic advisor was able to effectively signpost a student to a further support service and generate a positive student experience which will hopefully lead to long term career success. Although retention and graduation rates are important, the Association of American Colleges and Universities (2007) suggested that the ultimate measure of success is the ability of students to thrive in professional environments, cementing the importance of employability support and signposting by the academic advisor.

What is clear is that the students in this study strongly value the academic advisor support with one student stating:

“You’ve got an ally on the course, someone that you can always go to, who you see regularly as well, even passing in the corridor you see them, and they’ll ask how you’re doing.”

In this sense, the results indicate a positive impact on student experience but from a student perspective the primary focus of advising was not about academic attainment in the sense of educational attainment as discussed earlier but rather “holistic attainment.” Within this study, rather than focusing narrowly on the relationship between attainment and advising (Movat, 2017), these findings move away from this concept and value the role academic advising offers in terms of support with a wider range of aspects related to university life and beyond, such as wellbeing, pastoral, and employability support.

The results of this case study are in line with Cahill et al. (2014) findings, that a wide range of support strategies, including pastoral, and employability, are valued by students. Positive experiences with such support are thought to encourage learning, decrease attrition rates and contribute to improved academic achievement (Ning and Downing, 2012) and in support of Bahr’s (2008) study, academic advisors are highlighted here as being critical to providing these positive learning experiences and environments (Bahr, 2008). In particular, it is evident that students value the advising relationship and the support provided has assisted them to be better able to manage in the university environment which in turn impacts on their ability to achieve academically. So, whilst this study has not found a clear impact between academic advising and attainment, academic advising does provide an indirect positive impact on attainment, supporting a more “holistic” view of attainment.

The findings indicate that the pastoral support given to students over the course of their time at university provides the scaffolding upon which retention, progression, completion and ultimately attainment of a degree classification is achieved. On the other hand, the employability support serves as a way to widen the student perspective beyond that of academic achievements, heightening aspirations and providing a goal to work toward. Relating this to relevant literature, we know that the setting of goals acts as a motivator with Locke et al. (1981) stating that they direct attention, mobilize effort, encourage persistence and facilitate strategy development and as such the practice could in turn increase attainment.

These findings could be likened to the principles of Maslow’s (1943) Hierarchy of Needs in which individuals’ require fulfillment of basic needs, in this case through pastoral support, in order to build a core foundation upon which higher order needs such as attainment and employment aspirations can be achieved. In this sense, the relationship between academic advising and attainment is both explicit and implicit with the latter being evidenced most by the students.

Central to successful advising is the quality of the relationship between students and advisors which is documented in the existing literature with Habley (1987) suggesting that quality academic advising is made up of three component parts: the informational, the conceptual and the relational with the latter said to make the difference between academic advising and quality academic advising:

“Communication skills and interpersonal approaches such as listening, interviewing, rapport-building, self-disclosure, and referral directly influence advisor-advisee interactions and are critical to establishing positive advising relationships” (Haley, 2016).

Further to this, Gordon-Starks (2015, p1) defines academic advising as “relationship-building” in which the academic advisor acts as a mentor, guide, and positive influence to their students. What is clear is that if relationships are to be positive then institutions need to take a person centered approach with the development of an effective advising relationship as a gateway to developing a wider learning experience (Higgins, 2016). Numerous studies have supported the value of empathy in that when students feel advisors are empathetic to their needs then authentic and trusting relationships are built (Hybels and Weaver, 2009; Sims, 2013; Heikkila and McGill, 2015). It is from these relationships of trust that students feel able to disclose their thoughts, feelings and any issues that they may be going through as shown in this research. Relationships between academics and students and the trust this often breeds has been a central theme throughout the data collected and in line with Yale (2017), the relationship between the student and academic advisor often embodies the relationship that the student has with the university as a whole and can ultimately have an indirect impact on attainment.

A further contribution is that attainment should be viewed more in line with academic advising definitions that focus on the holistic development of individuals. Key components of the academic advising role in this sense include connecting students with the HE environment, creating high impact learning experiences, developing social communication skills, enhancing behavioral awareness problem solving skills, encouraging lifelong learning, and developing employability (Cuseo (n.d.); Gordon et al., 2008 and Drake, 2011). As such attainment needs to be viewed less about academic achievement and more in terms of holistic attainment whereby the person is developed as a whole to better equip them to deal with university life and beyond. This was evident within this small group study, so whilst this may not be fully generalizable to other research studies, it is certainly significant within this study. As the Association of American Colleges and Universities (2007) suggests, graduate attainment is important, student success or in this case attainment, should be viewed by the student’s ability to thrive in professional, personal, and societal arenas. Further research into the relationship between advising and holistic attainment at each stage of the university experience and post-graduation would be valuable to build a bigger picture of the impact.

Academic advising remains an essential part of the new HE environment and this research further expands upon what constitutes “good advising” and supports Light’s (2001) view that it is “the single most underestimated characteristic of a successful college experience.” There needs to be greater recognition of the complexity of the role and impact that it can have on “holistic” attainment that goes beyond academic achievement (Bahr, 2008). In this context, academic advising requires continued institutional investment and should aim to develop student agency in order to allow them to reflect, review and manage their own learning experience and become autonomous learners and professionals.

Due to the nature of the data involving students and ethics procedures, data was destroyed following data analysis so is not available upon request.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Sheffield Hallam University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

CH and CW: literature review. CH and CW: discussion/findings/conclusion. NH: methodology/findings. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Academic and Professional Advice Framework (2015). Academic and Professional Advice Framework Sheffield Hallam University. Sheffield: Sheffield Hallam University.

Ashwin, P. (2005). Variation in students’ experiences of the ‘Oxford tutorial’. High. Educ. 50, 631–644. doi: 10.1007/s10734-004-6369-6

Association of American Colleges and Universities (2007). College Learning for the New Global Century. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Bahr, P. (2008). Cooling out in the community college: what is the effect of academic advising on students’ chances of success? Res. High. Educ. 49:8. doi: 10.1007/s11162-008-9100-0

Battin, J. (2014). Improving academic advising through student seminars: a case study. J. Crim. Justice Educ. 25:3. doi: 10.1080/10511253.2014.910242

Buchan, L. (2018). Students Wait up to Four Months for Mental Health Support at UK Universities. The Independent. Available online at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/students-mental-health-support-waiting-times-counselling-university-care-diagnosis-treatment-liberal-a8124111.html

Budd, R. (2017). Undergraduate orientations towards higher education in Germany and England: problematizing the notion of “student as customer”. High. Educ. 73:1. doi: 10.1007/s10734-015-9977-4

Cahill, J., Bowyer, J., and Murray, S. (2014). An exploration of undergraduate students’ views on the effectiveness of academic and pastoral support. Educ. Res. 56:4. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2014.965568

Campbell, S., and Nutt, C. (2008). Academic advising in the new global century: supporting student engagement and learning outcomes achievement. Peer Rev. 10, 4–7.

Canaan, J. E. (2010). “Introduction,” in Why Critical Pedagogy and Popular Education Matter Today, eds S. Amsler, J. E. Canaan, S. Cowden, S. Motta, and G. Singh (Birmingham: C-SAP), 5–10.

Collis, J., and Hussey, R. (2014). Business Research?: A Practical Guide for Undergraduate and Postgraduate Students 4th Edn. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.

Crookston, B. B. (1994). A developmental view of academic advising as teaching. NACADA J. 14, 5–9. doi: 10.12930/0271-9517-14.2.5

Crookston, B. B. (2009). A developmental view of academic advising as teaching. NACADA J. 29, 78–82. doi: 10.12930/0271-9517-29.1.78

Cuseo, J. (n.d.). Academic Advisement and Student Retention: Empirical Connections & Systemic Interventions. Available online at: http://www.uwc.edu/admin-istration/academic-affairs/esfy/cuseo/Academic%20Advisement%20and%20Student%20Retention.doc (accessed August 15, 2019).

Denscombe, M. (2010). Ground Rules for Social Research?: Guidelines for Good Practice, 2nd Edn. United Kingdom: McGraw-Hill/Open University Press.

Drake, J. (2011). The role of academic advising in student retention and persistence. About Campus. 16:3. doi: 10.1002/abc.20062

Earl, W. R. (1988). Intrusive advising of freshmen in academic difficulty. NACADA J. 8, 27–33. doi: 10.12930/0271-9517-8.2.27

Earwaker, J. (1992). Helping and Supporting Students Buckingham. London: SRHE and Open University Press.

Foen Ng, S., Confessore, G., and Abdullah, M. (2012). Learner autonomy coaching: enhancing learning and academic success. Int. J. Ment. Coach. Educ. 1:3. doi: 10.1108/20466851211279457

Gordon, V., Habley, W., and Grites, T. (2008). Academic Advising: A Comprehensive Handbook, 2nd Edn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Grant, A. (2006). “Personal tutoring: a system in crisis,” in Personal Tutoring in Higher Education, eds L. Thomas and P. Hixenbaugh (Stoke on Trent: Trentham Books), 11.

Gordon-Starks, D. (2015). Academic Advising is Relationship Building. NACADA Academic Advising Today. Available online at: https://nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Academic-Advising-Today/View-Articles/Academic-Advising-is-Relationship-Building.aspx (accessed August 14, 2020).

Habley, W. R. (1987). Academic Advising Conference: Outline and Notes. The ACT National Center for the Advancement of Educational Practices. Iowa City, IA: ACT.

Habley, W. R. (2004). The Status of Academic Advising: Findings from the ACT Sixth National Survey. Ph. D. Thesis, National Academic Advising Association, Manhatten, KS.

Haley, L. (2016). The Role of Emotional Intelligence in Quality Academic Advising. Manhattan, KS: NACADA.

Hall, J. (2011). Britain ‘Must Change Its Savings Culture’. [online]. The Daily Telegraph, Vol. 21. Available online at: http://shu.summon.serialssolutions.com/2.0.0/link/0/eLvHCXMwY2AwNtIz 0EUrEyxNLS3NLZMMk41SEi1MEoHNlBRD89RkYF2eaGSSBD5xA3GMAQ-ivHITYmBKzRNlkHNzDXH20IWVlvEpOTnxwI4D6Lw4SwtDQzEGFmBnO VWCQSEp1TA5DVgrpqYlp5lYAJFpcmpaomGqiXGagXmqhRkAv1gnRQ (accessed July 5, 2019).

Hawthorne, M., and Young, A. (2010). First-generation transfer students’ perceptions: implications for retention and success. J. College Orient. Trans. 17:2. doi: 10.24926/jcotr.v17i2.2722

Heikkila, M. R., and McGill, C. M. (2015). A Study of the Relational Component in An Academic Advisor Professional Development Program. Available online at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/46951044.pdf (accessed August 19, 2019).

Hemwall, M. K., and Trachte, K. C. (2005). Academic advising as learning: 10 organizing principles. NACADA J. 25, 74–83. doi: 10.12930/0271-9517-25.2.74

Higgins, E. (2016). The Undecided College Student: An Academic and Career Advising Challenge. Journal of College Student Development. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, doi: 10.1353/csd.2016.0088

Kalfa, S., and Taksa, L. (2015). Cultural capital in business higher education: reconsidering the graduate attributes movement and the focus on employability. Stud. High. Educ. 40, 580–595. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2013.842210

Laycock, M., and Wisdom, J. (2009). Personal Tutoring in Higher Education-where Now and where Next?: A Literature Review and Recommendations. London: Staff and Educational Development Association (SEDA).

Locke, E., Shaw, K., Saari, L., and Latham, G. (1981). Goal setting and task performance: 1969–1980. Psychol. Bull. 90, 125–152. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.90.1.125

Lynch, J., and Lungrin, T. (2018). Integrating academic and career advising toward student success. New Direct. High. Educ. 2018:184. doi: 10.1002/he.20304

Matthews, B., and Ross, L. (2010). Research Methods – A Practical Guide for the Social Sciences. Essex: Pearson Education Limited.

McFarlane, K. J. (2016). Tutoring the tutors: supporting effective personal tutoring. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 17, 77–88. doi: 10.1177/1469787415616720

Mental Health Foundation (2018). Mental Health Statistics: Children and Young People. Available online at: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/statistics/mental-health-statistics-children-and-young-people (accessed August 8, 2019).

Molesworth, M., Nixon, E., and Scullion, R. (2011). The Marketisation of Higher Education: The Student as Consumer. London: Routledge.

Movat, J. G. (2017). Closing the attainment gap – a realistic proposition or an elusive pipe-dream? J. Educ. Policy. 33, 299–321. doi: 10.1080/02680939.2017.1352033

Ning, H. K., and Downing, K. (2012). Influence of student learning on academic performance: the mediator and moderator effects of self-regulatin and motivation. Br. Educ. Res. J. 38, 219–237. doi: 10.1080/01411926.2010.538468

Novo, A., and Calixto, J. A. (2009). “Academic achievement and/or educational attainment – the role of teacher librarians in students’ future: main findings of a research in Portugal,” in Proceedings of the 38th IASL Annual Conference, (Pádua: At Abano Terme).

Neuman, W. (2011). Social Research Methods?: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 7th Edn. United Kingdom: Pearson.

NUS (2015). Academic Support Benchmarking Tool. Available online at: https://www.nusconnect.org.uk/resources/academic-support-benchmarking-tool (accessed July 15, 2019).

Office for Students (2020). Continuation and Attainment Gaps. Available online at: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/promoting-equal-opportunities/evaluation-and-effective-practice/continuation-and-attainment-gaps/ (accessed July 10, 2019).

Propp, K. M., and Rhodes, S. C. (2006). Informing, apprising, guiding, and mentoring: constructs underlying upperclassmen expectations for advising. NACADA J. 26, 46–55. doi: 10.12930/0271-9517-26.1.46

Saunders, M., and Lewis, P. (2012). Doing Research in Business and Management an Essential Guide to Planning Your Project. Harlow: Financial Times Prentice Hall.

Shelton, E. N. (2003). Faculty support and student retention. J. Nurs. Educ. 42, 68–76. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20030201-07

Sims, A. (2013). Academic advising for the 21st century: using principles of conflict resolution to promote student success and build relationships. Acad. Advis. Today. 36:1.

Skyland Trail (2018). Onset of Mental Illness: First Signs and Symptoms in Young Adults. Available online at: https://www.skylandtrail.org/About/Blog/ctl/ArticleView/mid/567/articleId/5706/Onset-of-Mental-Illness-First-Signs-and-Symptoms-in-Young-Adults (accessed June 25, 2019).

Small, F. (2013). Enhancing the role of personal tutor in professional undergraduate education. Inspiring Acad. Pract. 1, 1–11.

Smith, N. (1987). Of yuppies and housing: gentrification, social restructuring, and the urban dream. Environ. Plan. 5, 151–172. doi: 10.1068/d050151

Stephen, D. E., O’Connell, P., and Hall, M. (2008). ‘Going the extra mile’, ‘fire-fighting’, or laissez-faire? Re-evaluating personal tutoring relationships within mass higher education. Teach. High. Educ. 13, 449–460. doi: 10.1080/13562510802169749

Steventon, G., Cureton, D., and Clouder, L. (2016). Student Attainment in Higher Education. London: Routledge.

Strayhorn, T. L. (2015). Reframing academic advising for student success: from advisor to cultural navigator. J. Natl. Acad. Advis. Assoc. 35, 56–63. doi: 10.12930/nacada-14-199

Strivens, J. (2006). “Transforming Personal Tutors Into Personal Development Tutors at the University of Liverpool” The Centre for Recording Achievement (CRA) publication. York: Higher Education Academy.

The Higher Education Academy (2015). Framework for Student Access, Retention, Attainment and Progression in Higher Education. Available online at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/downloads/studentaccess-retention-attainment-progression-in-he.pdf (accessed June 30, 2019).

Thomas, C., and McFarlane, B. (2018). Playing the long game: surviving fads and creating lasting student success through academic advising. New Direct. High. Educ. 8:184. doi: 10.1002/he.20306

Thomas, L., and Hixenbaugh, P. (2006). Personal Tutoring in Higher Education. London: Institute of Education Press.

Tinto, V. (2007). Research and practice of student retention: what next? J. College Stud. Retent Res. Theor. Pract. 8, 1–19. doi: 10.2190/4ynu-4tmb-22dj-an4w

Veal, A. (2011). Research Methods for Leisure and Tourism?: A Practical Guide, 4th Edn. New Jersey: Financial Times Prentice Hall.

Wheeler, S., and Birtle, J. (1993). A Handbook for Personal Tutors. Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Woodall, T., Hiller, A., and Resnick, S. (2014). Making sense of higher education: students as consumers and the value of the university experience. Stud. High. Educ. 39, 48–67. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2011.648373

Yale, A. T. (2017). The personal tutor–student relationship: student expectations and experiences of personal tutoring in higher education. J High. Educ. 43, 533–544. doi: 10.1080/0309877x.2017.1377164

Yorke, M., and Longden, B. (2004). Retention and Student Success in Higher Education. London: McGraw-Hill Education.

Young-Jones, A., Burt, T., Dixon, S., and Hawthorne, M. (2013). Academic advising: does it really impact student success? Qual. Assur. Educ. 21:1. doi: 10.1108/09684881311293034

Every student at SHU is assigned an Academic Advisor, this is the person who is there to help you navigate the course and get the most out of your studies. We would appreciate if you could complete this to provide some general background to the frequency, nature and the context of the support you receive.

Please circle the appropriate responses;

How is your academic advice delivered?

Prompts – Group sessions, 1:1’s, meeting each semester.

How appropriate is the current format for meeting with your academic advisor?

Do you feel the frequency of contact is appropriate?

What kind of support have you asked your academic advisor provided?

Prompts – Pastoral support, signposting to university services, academic advice, professional advice.

Has the support you have received been timely and appropriate?

Prompts – Have you been able to meet with your advisor when needed?

Based on the support you have received, which advice have you valued the most?

How well informed is your academic advisor of your current academic performance?

How have the meetings and sessions with your advisor helped with your academic performance?

How has your academic advisor helped you make sense of your course?

To what extent has the support you have received helped you reach your full potential?

Has the information you have received from your academic advisor about support services been accurate?

Prompt – has this helped you navigate SHU as a large organization?

What do you feel are the specific positives about the academic advisor role?

What should SHU’s priorities be to improve the academic advisor role?

Keywords: advising, attainment, tutoring, success, achievement, higher education

Citation: Holland C, Westwood C and Hanif N (2020) Underestimating the Relationship Between Academic Advising and Attainment: A Case Study in Practice. Front. Educ. 5:145. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00145

Received: 01 February 2020; Accepted: 21 July 2020;

Published: 28 September 2020.

Edited by:

Emily Alice McIntosh, Middlesex University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Charlotte Stevens, The Open University, United KingdomCopyright © 2020 Holland, Westwood and Hanif. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Claire Holland, Yy5ob2xsYW5kQHNodS5hYy51aw==; Caroline Westwood, Yy53ZXN0d29vZEBzaHUuYWMudWs=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.