- 1The Open University, Institute of Educational Technology, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom

- 2Department of Higher Education, University of Surrey, Guildford, United Kingdom

The purpose of this article is to explore how Early Career Academics (ECAs) cope with their complex and multiple transitions when starting their new role. By focussing on the participants’ lived experiences in a professional development (PD) training program to discuss and share practice, we explored how ECAs developed and maintained social network relations. Using social network analysis (SNA) with web crawling of public websites, data was analyzed for 114 participants to determine with whom they shared practice outside PD (i.e., external connectors), the seniority of these connectors, and similarity to their job area. The results highlight that ECA networks were hierarchically flat, whereby their sharing practice network of 238 external connectors composed of their (spousal) partner and (male) colleagues at the same hierarchical level. The persons whom ECAs were least likely to discuss their practice with were people in senior management roles. The results of this study highlight that the creation of a community of practice for discussing and sharing of practice from PD programs appear to be insular. Activities within the organization and the formation of learning communities from PD may become lost as most of the sharing of practice/support comes from participants’ partners. Organizations may have to create spaces for sharing practice beyond the PD classroom to further organizational learning.

Introduction

Early Career Academics (ECAs) go through many transitions in their early stages of their career. While there are many definitions of ECAs, in this study we define ECAs as individuals who have a maximum of 4 years’ academic teaching and/or research experience following the completion of their Ph.D. While there are many routes that teachers and ECAs can take after completing a professional doctorate or Ph.D. to further their careers (Jindal-Snape and Ingram, 2013; Spurk et al., 2015), for those who want to stay in academia often a teacher-route, researcher-route, or combined teacher-researcher route is paved with substantial challenges (Adcroft et al., 2010; Uttl et al., 2017), uncertainties (Spurk et al., 2015), and risks (Kalyani et al., 2015; Mittelmeier et al., 2018). As highlighted by a recent report by the Wellcome Trust (2020), of the 4,267 surveyed academics 70% of respondents indicated to be stressed at work, and to experience mental health issues. Furthermore, less than a third of ECAs felt secure in pursuing a research career, and a substantial number of ECAs indicated a desire to leave academia. Obviously when ECAs are uncertain about their own roles, identities, and careers, this could have substantial negative impacts on supporting the transitions of students and pre-service teachers as well.

One potential solution to these complex issues are to provide appropriate professional development (PD) and support. Across the globe, ECAs follow a range of PD and training programs in order to help them to make a “successful” transition from ECA to obtaining tenure, or to continue their careers outside academia (Tynjälä, 2008; Jippes et al., 2013; Pataraia et al., 2013). On a macro level, several studies (e.g., Bartel, 2000; Almeida and Carneiro, 2009) have found positive return on investment effects of training. On a micro level, a large number of PD studies found that employees were satisfied with training activities (Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick, 2006; Stes et al., 2010), indicated to have learned to become more student-centered (Rienties et al., 2013), and gained confidence (Rienties and Hosein, 2015). However, limited empirical research is available about the underlying mechanisms how and with whom ECAs learn outside a PD program. Furthermore, given the focus of this special issue we were keen to explore how people around ECAs (e.g., fellow PD colleagues, colleagues in their department, family, friends) helped or perhaps hindered ECAs’ complex transition to become established teachers and/or academics.

This study is specifically focussed on whether and with whom ECAs engage, socially co-construct and share knowledge beyond the “PD training room” (Bevelander and Page, 2011; Roxå et al., 2011). Uptake of PD and “successful” transition may be dependent on the “external” (i.e., outside the PD training) network of participants (Akkerman and Bakker, 2011; Roxå et al., 2011; Van Waes et al., 2018; Thomas et al., 2019) and/or the organizational cultures within the participants’ organizational units or departments (Daly and Finnigan, 2010; Pataraia et al., 2013; Van Waes et al., 2018; Wellcome Trust, 2020). For example, our prior studies on ECAs outside the PD training network of participants (Rienties and Kinchin, 2014; Rienties and Hosein, 2015) indicated that although ECAs developed on average 4.00 social ties after 9 months within their PD program, they also maintained on average 3.63 external social ties outside the PD classroom to discuss the insights from the PD program.

Although identifying the potential impact of “externals” on the complex transition processes is notoriously complex and difficult (Jindal-Snape and Ingram, 2013; Froehlich et al., 2020; Thomas et al., 2020b), one potential methodology that holds some promise is the use of Social network analysis (SNA). An emerging body of research has indicated that SNA can provide transition researchers several analytical tools to make these (in)formal relations amongst participants and people outside the learning context “visible” (Jindal-Snape, 2016; Jindal-Snape and Rienties, 2016; Froehlich et al., 2020). A consistent finding of research using SNA is that formal and informal social network relations strongly influence with whom people learn (Thomas et al., 2019, 2020b; Froehlich et al., 2020), develop coping strategies (Daly and Finnigan, 2010; Daly et al., 2010; Moolenaar et al., 2012), establish new friendship relations (Rienties and Kinchin, 2014), and build (in)formal communities to effectively learn together (Froehlich et al., 2020; Thomas et al., 2020a). At the same time, people (sub)consciously develop strategic network relations with a range of people in order to maximize their network potential (Coleman, 1988; Burt, 1992; Lin, 2001; Roxå et al., 2011). For example, some people link strategically with powerful connectors (e.g., senior managers) within their organization (Lin, 2001), others primarily connect with similar people (e.g., colleagues in the same unit and/or on a similar hierarchical level) (Coleman, 1988; Rehm et al., 2014), while others may maintain relatively more ties with people outside their organization (Bresman, 2010).

These connections can also be linked with the Multiple and Multi-dimensional Transitions (MMT) model of Jindal-Snape (2010), which conceptualizes that in line with a Rubik’s cube analogy a change in one aspect (e.g., getting a ECA grant, failing probation) can lead to changes for the ECA in several aspects; changes for one person can lead to changes for the significant others (e.g., having to stay in the region after a successful ECA grant of the partner, having to consider to leave after failed probation of the partner) and vice versa. As argued in the MMT model (Jindal-Snape and Ingram, 2013; Jindal-Snape, 2016), while most transition research focuses on the individual transition only, a more holistic approach taking the wider network of relations into consideration is important to understand the complex multiple transitions that people go through.

Using principles of social capital theory in conjunction with MMT theory, the prime goal of this study is to understand with whom ECAs developed external social relations. While our first (explorative) studies (Rienties and Kinchin, 2014; Rienties and Hosein, 2015) have found that ECAs indeed maintained a range of internal and external social relations, using a larger sample of 114 participants in this follow-up large-scale study we are particularly interested in the characteristics of these “external connectors,” and how these external connectors might facilitate or hamper transition processes of ECAs. In particular, given recent findings that hierarchy and seniority of connectors might influence network formations (Edmondson, 2002; Rehm et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2020a), we specifically focussed on the frequency of contact, the hierarchical position, and type of job role of these external connectors. Therefore, the following research questions were formulated:

(1) With whom do ECAs maintain external relations in order to discuss and share experiences of their transitions from the PD program? What is the basis for their social network relations?

(2) To what extent do hierarchical levels and job roles of external connectors influence the type and frequency of contact?

(a) Are ECAs primarily maintaining strategic connections with senior academics/managers/teachers?, or

(b) Are ECAs primarily maintaining social relations with fellow peers on a similar discipline/hierarchical level/job role?

While a number of studies have conceptualized how professionals build, maintain, and reconstruct their networks (Wenger, 1998; Akkerman and Bakker, 2011; Pataraia et al., 2014), the unique contribution of our study is to measure empirically whether (or not) ECAs share their expertise and lessons-learned in the PD with external connectors, whom have substantial power to influence the strategic direction of an organization, or whether ECAs are primarily sharing with their colleagues on similar hierarchical positions. In this study, we employ a rather innovative approach to link SNA with web crawling techniques to unpack the “public” characteristics of each named external connector. By integrating these two approaches, we aim to unpack whether the boundary impact of PD is primarily shared on a horizontal level, or whether some of the innovative practices discussed in PD are also shared on a vertical level.

Social Network Theory, Multiple and Multi-Dimensional Transitions and Professional Development

A range of studies have highlighted the importance of social network formation for learning for ECAs (Pataraia et al., 2014; Rehm et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2020a). For example, Pataraia et al. (2014) investigated the informal networks of teaching academics using a SNA approach. They were interested in whom academics who were not part of a PD program spoke to about their teaching, the frequency of contact and the themes arising from this conversation. Pataraia et al. (2014) found that the personal networks were strongly localized to the academics’ departments and disciplines, and were dependent on whether the majority of the members knew each other well. Similarly, in a schooling context a range of studies have found that with whom an early-career teacher networks is essential for successful transition (Thomas et al., 2019, 2020a,b). For example, in a year-long study of 10 beginning teachers in Belgium (Thomas et al., 2020b) combining four SNA measurements with in-depths interviews with both beginning teachers and their colleagues indicated that many early-career teachers went through diverse complex transitions. Those who effectively managed their network relations and actively built and maintained networks with both experienced colleagues and others outside the school were more able to successfully make their transition (Thomas et al., 2020b).

A substantial body of research has highlighted that the social network around an individual employee influences his/her attitudes (Van Den Bossche and Segers, 2013; Rienties and Hosein, 2015; Thomas et al., 2020a), motivation (Daly et al., 2010), behavior (Jippes et al., 2013; Pataraia et al., 2013) and action (Thomas et al., 2020b). A social network consists of set of nodes (i.e., participants in a PD program) and the relations (or ties) between these nodes (Wassermann and Faust, 1994). In social network theory, the focus of analysis is on measuring and understanding the social interactions between entities (e.g., individuals, organizational units, companies), rather than focussing on individual behavior (Lee, 2010; Bevelander and Page, 2011).

Social Capital and Network Building

Social capital is a concept with probably the largest growth area in organizational network research (Borgatti and Cross, 2003), which is concerned with the value of resources that social network ties hold. Social capital can be defined as “resources embedded in a social structure which are accessed and/or mobilized in purposive action” Social capital is concerned with the value of resources that social network ties hold (Borgatti and Cross, 2003). Social capital can be defined as “resources embedded in a social structure which are accessed and/or mobilized in purposive action” (Lin, 2001). A review of the conceptualisation of social capital by Lee (2010) highlighted three conceptual issues: the use and accessibility of potential resources, social capital formation processes, and network orientations. For example, in a fine-grained analyses of 11 United Kingdom academics Pataraia et al. (2013) found that academics strategically manage their pool of network contacts to provide and receive professional and emotional support.

Generally there are four explanations why sources embedded in social networks will enhance the returns on an individual’s actions (Lin, 2001). The first explanation is that embedded resources facilitate information and knowledge flows between professionals, which consequently reduces transaction costs, such as sharing of ideas, new innovative practices, or lessons-learned (Moolenaar et al., 2012). In terms of information flows within organizations, in organizational behavior research and to a certain degree in educational research it is well-documented that professionals share information with people with whom they have a common identity, such as colleagues from their division/department (Moolenaar et al., 2012; Rienties and Hosein, 2015). In terms of information flows within organizations, in organizational behavior research and to a certain degree in educational research it is well-documented that professionals share information with people with whom they have a common identity, such as colleagues from their division/department (Daly and Finnigan, 2010; Daly et al., 2010; Thomas et al., 2020b). This is sometimes referred to as the proximity principle. Thus, when participants return to their daily practice after PD training, how knowledge and insights from the training are shared, translated, and embedded into the organization may depend on the formal and informal networks of their colleagues within the department, their respective identity/position (such as a manager), and relationships within the department.

Second, social ties have a substantial influence upon how employees deal with PD and organizational change (Daly et al., 2010; Moolenaar et al., 2010; Spurk et al., 2015; Van Waes et al., 2018). For example, if an academic wants to explore a new teaching approach (suggested during the PD) to further fine-tune a particular module or program, and (s)he has a strong connection with senior management, this academic may be more likely to be given support to develop this “innovation,” and would be allowed more risk-taking than someone who has no or weak relations to senior management. For example, Edmondson (2002) found that lower level management employees were more concerned about how senior management and their colleagues perceived them and their quality of work, and hence were less likely to take risks. Furthermore, in an online PD program for 249 managers of a global organization, Rehm et al. (2014) found that senior managers were more central in contributing to discourse in discussion forums, while participants who had a lower hierarchical rank were positioned mostly on the outer fringe of the network. Rehm et al. (2014) argues that the expertise and networks of senior managers could be used by lower level management employees to make their voices heard.

Third, social ties may be conceived as certification of social credentials, as it reflects teacher’s accessibility to resources through (powerful) social networks and relations, thus his or her social capital (Lin, 2001). If this academic’s innovation is successful and his/her colleagues and senior management (i.e., connectors) provide (in)formal recognition, others are more likely to adopt the same innovation, even when no social support is given. For example, in a study measuring the spread of a new medical approach amongst 727 medical specialists, Jippes et al. (2013) found that uptake and spread of this new approach was dependent on the centrality of the clinical supervisor (i.e., senior connector) and the connectivity of its members within the department.

Finally, social networks provide substantial psycho-social support (Moolenaar et al., 2010, 2012), a sense of belonging (Thomas et al., 2020b), and reinforces identity and recognition (Lin, 2001). Rienties and Hosein (2015) found that participants in an 18 months PD program used their network contacts for academic, professional, and emotional support. While participants connected with fellow-ECAs in the PD primarily for academic support (i.e., how to cope with the various tasks in the PD program), several ECAs looked for professional support from senior management, either during formal job appraisal sessions or informal meetings (Rienties and Hosein, 2015). In other words, how and with whom people build formal and informal social relations outside PD may have an influence how they can leverage the power of those external connectors to use and apply the concepts from the PD into their own practice and organizational unit.

Beyond the social capital theory often in social network theory a distinction is made between the strength of a tie and the structure of the social network. Strong ties support the transfer of tacit, complex knowledge, and joint problem solving (Daly et al., 2010). Coleman (1988) indicates that high, frequent and intensive levels of connectedness between people can encourage formation of trust and stable relations, which in turn enhances fine-grained knowledge sharing and performance (Moolenaar et al., 2012). In social network studies this is commonly referred to as homophily, whereby people will be attracted to work (formally/informally) together and develop ties when individuals are (perceived to be) similar in terms of surface-level attributes, such as same gender (Bevelander and Page, 2011), similar interests (Borgatti and Cross, 2003), similar hierarchical position (Rehm et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2020b), or following the same program/discipline. For example, in study amongst 106 academics, Roxå et al. (2011) found that most academics relied on a relatively small network of key, trusted network contacts to discuss their teaching practice. In particular, proximity of people might influence to whom ECAs might turn to if they have specific issues (Borgatti and Cross, 2003).

In contrast, research by Granovetter (1973) indicates that weak ties can allow (new) brokerage information that is not known within a strong dense network. For example, a colleague from university A may meet a network contact from university B from a different discipline only twice a year during a local network event. Nonetheless, substantial new and most importantly non-redundant information (e.g., new grant opportunities, job vacancies, teaching innovations) could be mutually exchanged, which would make these infrequent meetings extremely valuable. Burt (1992) argues that individuals will gain more from social networks if they are able to position themselves on either side of a “bridge,” which may provide non-redundant information from different parts of the social network. In line with Borgatti and Cross (2003), a combination of strong ties with a substantial number of weak ties in different social networks will allow people to benefit from the diversity of social capital connections, while maintaining sufficient close and strong links with network connections who can be trusted.

In line with theories of strong versus weak ties, Putnam (2001) distinguishes between bonding and bridging social capital. Bonding social capital provides solidarity, mutual reinforcement and support, as commonly found amongst people from the same disciplinary background, or working together in the same PD program (Bevelander and Page, 2011; Rienties and Hosein, 2015). In contrast, bridging social capital may provide linkages with different (non-redundant) parts of the social network, thereby facilitating social mobility and potentially new innovations (Burt, 1992; Putnam, 2001). In a PD context, this bridging capital could be developed when ECAs from different organizational units work together and over time build “interdisciplinary” social relations (Rienties and Kinchin, 2014). Finally, in line with social capital theory Lin (2001) argues that having access to a few but powerful (in terms of reputation, credentials, seniority) connectors may be more important than having many links with “powerless” connectors.

Multiple and Multi-Dimensional Transition

In the MMT model (Jindal-Snape, 2010, 2016; Jindal-Snape and Ingram, 2013) there is a further recognition that beyond the professional network significant others (e.g., friends, family, partner) can have a substantial impact on transitions of the ECA, as well as ECAs having an impact on their peers’ transitions. For example, in a study of international doctoral students Jindal-Snape and Ingram (2013) found that Ph.D. students were not only focused on their own transition needs but also of their family. In a study amongst 22 Chinese international students studying in New Zealand, Skryme (2016) found that the involvement in Christian religious groups helped several international students to transition to their new lives abroad, while at the same time providing new perspectives to the host-nationals in these Christian groups. In a recent longitudinal study of an interdisciplinary PD for 15 doctoral students from nine institutions in six European countries showed a complex development of knowledge transfer and knowledge integration over time between participants (Xue et al., 2020). Qualitative follow-up interviews showed that both the set-up and design of the online PD as well as the relative engagement by doctoral students explained why some developed strong knowledge integration while others did not (Xue et al., 2020).

Beyond the local impact of physical connections between ECAs and the local community, there are several studies using SNA and other methodologies who show that several people use social media for support in their transitional journeys. For example, in a study of extreme right-wing groups in Sweden, Törnberg and Törnberg (2020) found that network connections between individual were facilitated by Facebook and other social media outlets. Similarly, Rehm et al. (2020) explored how 2695 teachers used Twitter to discuss about a new educational policy called Education2032, with follow-up interviews of 22 teachers indicating that the discussions helped teachers to make sense of their own identity and the new policies.

In other words, beyond the formal networks arranged within a PD program as well as the formal networks within a particular school or department, informal network relations outside the boundaries of these formal networks could have a substantial impact on transitions of ECAs. In this quantitative study we aimed to explore how 114 ECAs developed relations with external connectors to help them transition into a role as an academic, or perhaps consider to work in a professional context.

Materials and Methods

Setting

Hundred and fourteen ECAs from four faculties (arts and social science, business and economics, engineering and physics, health and medical science) at a university ranked consistently in the top 10 percent of league tables in the United Kingdom participated in a 18 months PD program. Participants could only join this program if a substantial part of their tasks were related to teaching undergraduate and post-graduate students. Participants were selected based upon recommendations from senior management, mostly a head of a department. One element in the tenure of these ECAs is successful completion of this PD and becoming a Fellow of the UK Higher Education Academy (renamed recently to Advanced HE) normally within the first 3 years of joining the organization. With an estimated workload of 300 h, the majority of hours were self-study, as only ten face-to-face group meetings of 2–3 h with a professional coach were arranged. Previous studies (Rienties and Kinchin, 2014; Rienties and Hosein, 2015; Jones et al., 2017) have found that this PD program was considered to be valuable to participants in terms of enhancing their teaching and learning practice, network formation, and social support. Furthermore, qualitative follow-up analyses (Rienties and Hosein, 2015) indicated that PD participants primarily relied on their PD peers in terms of academic, professional, and emotional support to make sense of the program, as well as to learn from their peers how to critically reflect on their own teaching and learning practice.

Participants

The average age of the 114 participants was 36 (range 26–57) and 56% of the ECAs were male. Although there was a large age range, all participants were at similar stages of their academic career (i.e., post Ph.D., post Post-doc). No significant differences in terms of demographics or organizational backgrounds were found between the two consecutive implementations, so we merged the datasets. Participants were from 23 different departments, primarily from business (14%), engineering, hospitality and tourism (both 11%), mathematics (7%), psychology and biosciences (both 6%). Ten participants had no other department member following the program in their respective cohort. While according to Finkelstein et al. (2013) most American universities are still relatively homogenous, in our context a large cultural diversity of 27 different nationalities was present, typical for an international science community, within which the largest group of participants (49%) were from the United Kingdom. International participants primarily were from Latin-European and Confucian Asian countries (both 10%), followed by countries from Germanic and Eastern Europe (both 7%).

Instruments

A sequential mixed-method approach was used (Creswell, 2003; Froehlich, 2020). A closed-network analysis in conjunction with an open network approach was first used to determine the external connectors in the ECAs social networks. Secondly, using the results from the survey, an online document analysis was performed to determine the job profile and hierarchical positions of the external connectors.

Social Network Analysis of Friendship, Working, and Learning and Teaching Networks

We used the closed-network analysis (Daly et al., 2010; Bevelander and Page, 2011; Rienties and Kinchin, 2014) after participants had worked together for 9 months to measure the social networks within the PD program consisting of three social network questions (e.g., “I have learned from…”), whereby lists with names of the 54 and 60 participants of the two cohorts were provided. Secondly, and most importantly for this study, in order to measure and investigate the role of “external” connectors in PD, we asked participants in an open network approach the following: “In addition to members of the [PD] program, we are interested to know with whom you discuss your learning and teaching issues (e.g., how to prepare for a lecture, how to create an assessment, how to provide feedback). This could for example be with a colleague, a friend, family, or partner who is not following the [PD] program.” Participants were asked the name of each external connector, the frequency of contact (as proxy for strength of tie), the type of relation, and where each external connector works (e.g., same department, same institution, external institution, namely). A response rate of 88% was established for the open and closed SNA questions.

Job Profile and Hierarchical Position of External Connectors

In total 289 external connectors were mentioned by participants. Based upon the provided names and institutional details, the authors identified, through a document analysis approach, whether a public website profile for each connector was present using the Google search engine and the world largest professional network LinkedIn, a practice that is common in SNA (Davison et al., 2011; Rehm et al., 2020). For 251 (87%) connectors, a public website profile was indeed available. For 35 connectors no specific public website was available, of which nine network contacts referred to people from a wider group (e.g., “my colleagues in my department X”), and for seven contacts no specific name was provided (e.g., my wife, my mother).

In order to develop a coherent, reliable coding scheme of the job profile and hierarchical position of external connectors, both authors first independently coded a sample of 20 websites. Most connectors had a clearly identifiable job role and hierarchical function listed on their website, and the pilot sample coding led to nearly identical results between the two coders. Afterward, four separate rankings were established. First, both authors independently analyzed and constructed 56 functional roles based upon the information provided on these websites (e.g., graduate teaching assistant, tutor, lecturer, associate professor, professor). Second, based upon these functional roles, three separate aggregate rankings were generated, namely seniority in organization (0–7), seniority in management role (0–7), and seniority in teaching (0–8), where the higher number denoted more seniority. For 36 network contacts, a second role was identified (e.g., program director and director of lab) while for two network contacts a third role was coded (e.g., program director and director of lab and associate dean). Consensus about the categorisation of the hierarchical levels and job roles was reached after discussions between the two authors. After agreement of the coding structure, the remaining websites were coded by the second author. Finally, the final codings were discussed by both authors and where needed functional roles were realigned.

Data Analysis

The 114 ECAs participated voluntarily in the SNA and free-response exercise. Participants who were not present during the session(s) were contacted via email. The participants were guaranteed that the results would be completely anonymised and participation was voluntary. Social network data were analyzed on a network level using UCINET version 6.694. In terms of the structure of the network, we computed in-degree Freeman’s centrality of the nodes, as well as the number of ties a node was connected to. Strength of ties with external connectors was measured by frequency of contact (daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly, yearly). As previous research (Bevelander and Page, 2011; Kalyani et al., 2015) indicated that gender strongly influenced how people developed links over time, we included gender in our modeling. As we were primarily interested in the network relations with external connectors, all data was coded and organized in SPSS 22, and Pearson correlations and linear regression modeling were conducted.

Results

Social Network Connections Within and Outside PD

Two hundred and seventy nine “external” connectors (i.e., outside the PD program) were used by the 114 ECAs. Most of these external connectors were male (59%). In terms of frequency of contact, 39% of these connectors were contacted on a weekly basis, 38% on a monthly basis, 11% on a quarterly basis, and 3% were contacted once a year. 9% of these connectors were contacted on a daily basis by ECAs to discuss their teaching practice. In line with proximity theory, 166 (52%) external connectors were colleagues, 52 (16%) were supervisors/senior managers, 51 (16%) were friends, and 36 (13%) were partners. As participants could indicate multiple relations (e.g., friend, colleague, supervisor), these numbers do not add up to exactly 279. Hundred and thirty three (48%) external connectors worked at the same department, and 192 (69%) worked in the same discipline, but not necessarily in the same institute, in line with proximity and homophily principles. In total 114 (41%) of the external connectors did not work at the same institute at the PD participants, indicating potential “weak” ties and bridge building opportunities. This is an important finding as in most research on ECA success and transitions in particular few studies focus on these types of external relations.

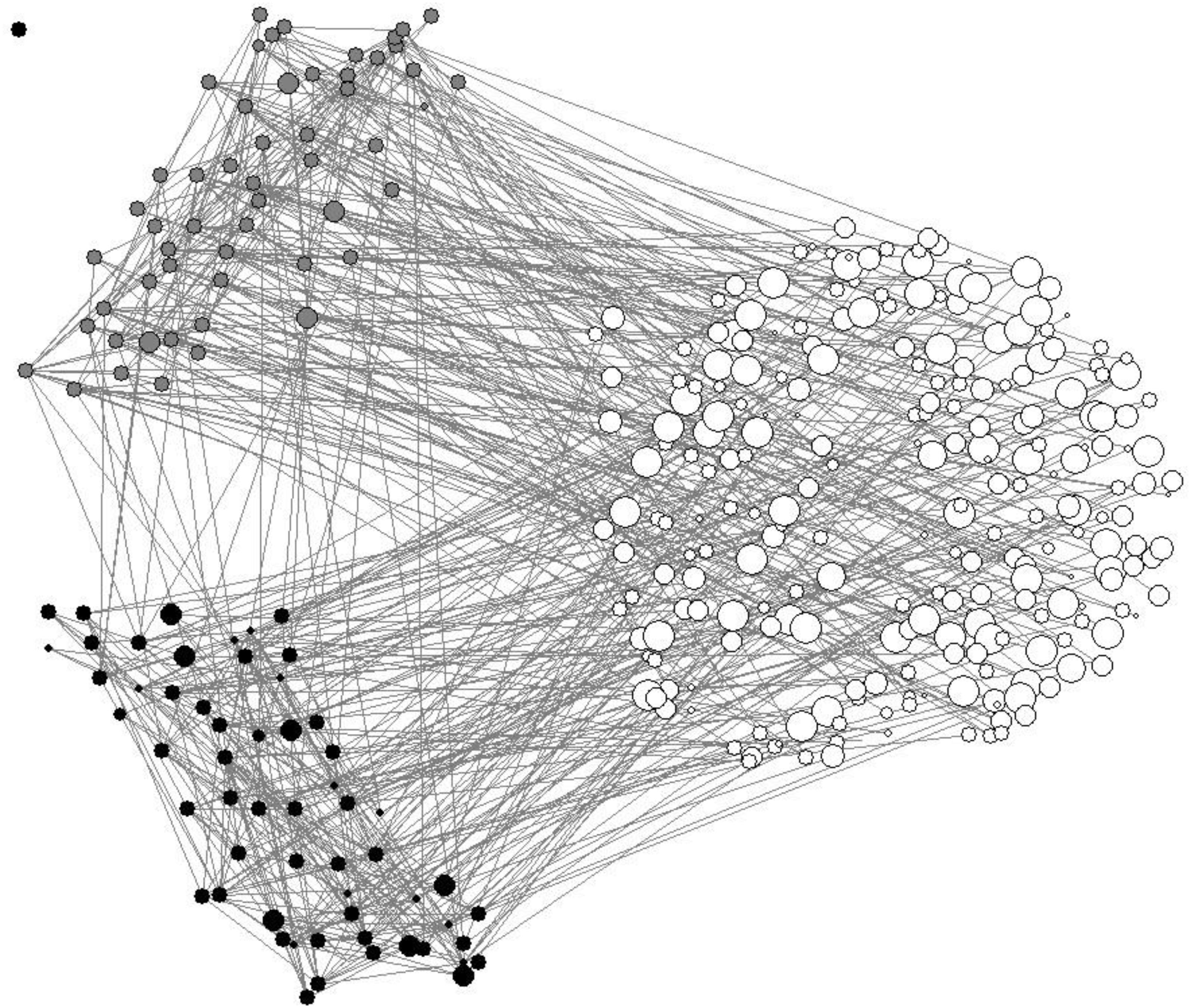

As illustrated in Figure 1, a complex web of network relations was present during the PD program. On the left of Figure 1, the two consecutive implementations of the PD are illustrated as gray and black nodes, whereby on average 4.84 (SD = 2.43) relations were developed and maintained within the PD per academic. Note that several participants from the second implementation learned from participants from the first implementation, as illustrated by the lines between the gray and black nodes. At the same time, a substantial number of links between the PD nodes and people outside the PD (white nodes) were developed. On average 3.17 (SD = 2.31) external connectors per ECA were used, indicating that PD participants extensively used connectors outside their PD. In terms of management expertise of these external connectors, a mix of seniority was present (as represented by the relative size of each node). Note that one participant from the second PD implementation did not have any connector to discuss his teaching practice with (and none of the 113 fellow participants indicated to have learned from him), and as a result he was not connected to the network (see the top left in Figure 1).

Figure 1. External and internal learning and teaching network (size nodes based upon management role).

To What Extent Do Hierarchical Roles of Connectors Influence Social Network Formations?

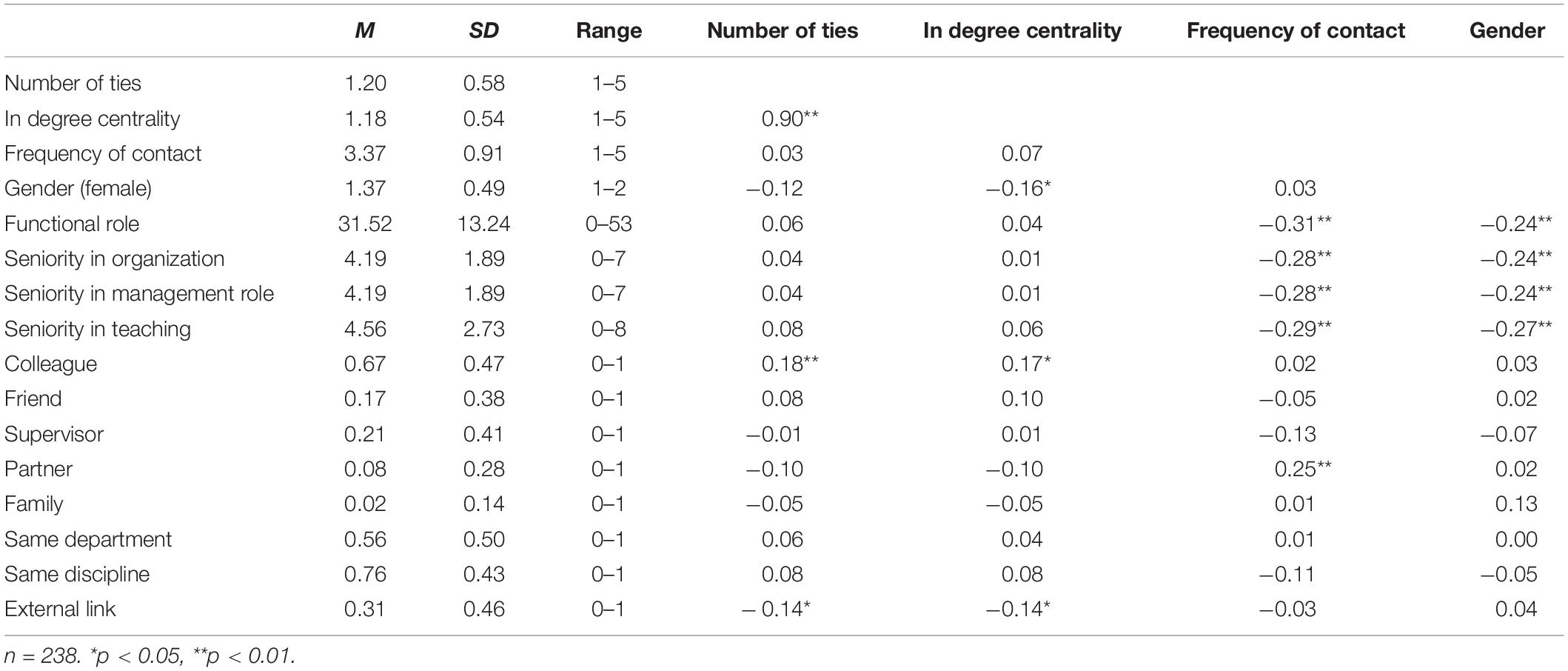

As a next step, we analyzed data for those external connectors whom we could identify a web presence with specific job role descriptors. This implied that 238 connectors were included in our follow-up analyses. In Table 1, the mean descriptives and correlations of the number of ties, centrality in the network, frequency of contact, gender (female), the four functional roles/seniority levels, and dummies for the type of relation (e.g., colleague, same discipline) are illustrated. While no significant correlations in terms of functional roles/seniority were found in terms of number of ties or centrality, there were moderately strong negative correlations between frequency of contact and the four hierarchical roles. In other words, ECAs in the PD program were more inclined to maintain frequent network relations with people on similar or lower hierarchical levels while frequency was less with more senior colleagues. As the rhos for the four hierarchical roles were rather similar, this seems to indicate that ECAs preferred to discuss their practice with ECAs in similar (or lower) positions.

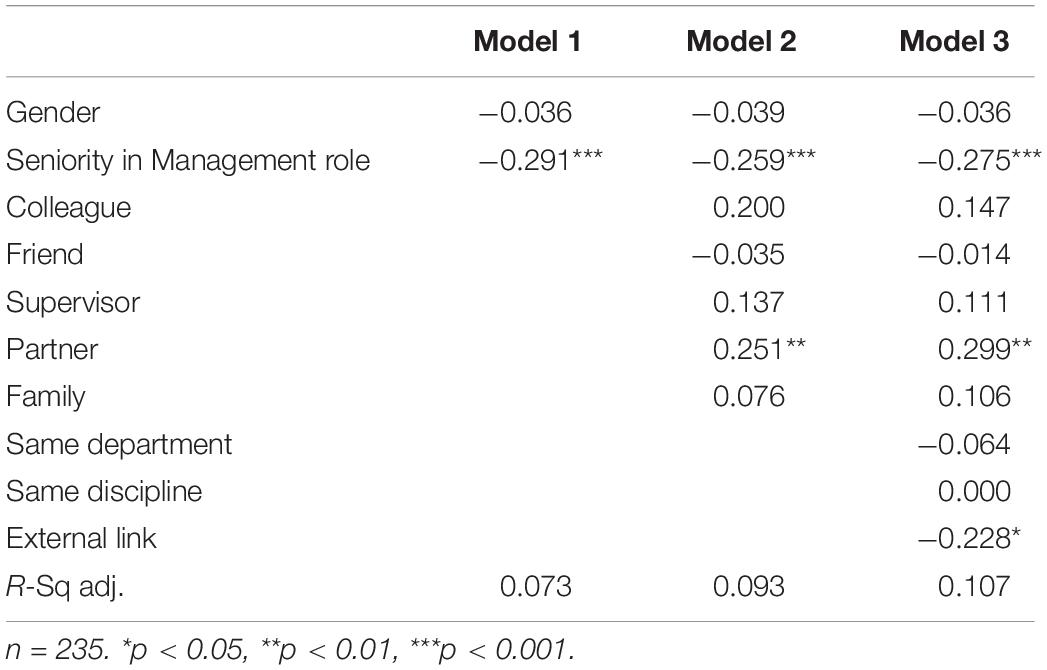

As a final step, using linear regression modeling in Table 2 we analyzed which of our variables predicted the strength of ties with external connectors, in this study approximated by frequency of contact. As the four functional role parameters were strongly correlated and overlapping, we used seniority in management role as a proxy for hierarchical position. In Model 1, strength of ties was primarily negatively predicted by seniority in management role. Adding the type of relation(s) in Model 2, seniority in management role remained the primary predictor, followed by whether (or not) a network contact was a partner. Although only 32% of PD participants indicated to discuss their teaching practice with their partner, if they did they mostly discussed their practice frequently. Finally, in Model 3 we added whether location of the connectors influenced frequency, whereby in addition to seniority in management role and partner dummy external links were significantly negatively predicting frequency of contact.

Discussion

As highlighted in both transition research (Jindal-Snape and Ingram, 2013; Jindal-Snape, 2016) as well as social network theories (Borgatti and Cross, 2003; Froehlich et al., 2020; Thomas et al., 2020a), many people go through multiple complex transitions when starting a new role. In this innovative study, we set out to explore the external social learning relationships of 114 early-career academics (ECAs) within a professional development (PD) program using an innovative combination of SNA with web crawling of external connectors’ websites. Our research indicates that our ECAs discussed and shared their teaching practice with 238 external connectors, including their colleagues, friends and their partner. However, these ECAs made only limited usage of senior management networks and expertise for their PD and their teaching practice in particular.

In line with principles of proximity and homophily (Coleman, 1988; Bresman, 2010; Daly et al., 2010; Rienties and Kinchin, 2014) and Research Question 2b, the PD participants shared their practice most widely with their colleagues both within and outside their departments/disciplines and suggest that these PD participants had a high level of connectedness with them. In line with principles of proximity and homophily (Coleman, 1988; Bresman, 2010; Daly et al., 2010; Rienties and Kinchin, 2014) and Research Question 2b, the PD participants shared their practice most widely with their colleagues both within and outside their departments/disciplines and suggest that these PD participants had a high level of connectedness with them. A negative correlation was found between gender and hierarchical roles, whereby male academics were more often present in senior management positions than female academics. Although similar results were found as Bevelander and Page (2011) and Kalyani et al. (2015) with regards to male staff being central to participant’s networks, this may be a reflection of the male to female staff ratio where the study took place rather than female participants being less likely to form social networks. Further, the information flow reported by participants in the PD program seemed to be hierarchically flat, that is, based upon the web crawl participants primarily shared information with people who they had a common identity (Daly and Finnigan, 2010; Daly et al., 2010; Rehm et al., 2014).

However, most ECAs had weak ties with respect to sharing practice with senior management and persons within their discipline/department (that is, no or negative correlations in the frequency of contact), participants may not then be able to act as brokers of these information flows to persons in their own department/discipline. This suggests that the value of PD training to a department may be lost as the sharing of new practices or ideas may have slow uptake. A consequence of this is that senior management may become distanced from the training that is provided and may make decisions based on the training they think they their personnel are receiving. In line with recommendations of Lane and Down (2010), departments and senior management in particular may need to “create a safe space for others to have their voice to harvest the wisdom of different and contrary perspectives to better anticipate what is unforeseen.” In other words, a joint effort is needed to allow participants to discuss and share their practice beyond the PD classroom to staff from all levels.

In line with recent studies on cross-boundary management (Bresman, 2010; Akkerman and Bakker, 2011; Thomas et al., 2020b), this study also found the sharing of practice extends beyond the organization and included persons in similar organizations (external links). The number of external links was small and there were weak ties with them which suggest that organizational learning between institutions is also insular. This makes intuitive sense, as connectors who were not working in the same location (e.g., a different university) will be less easy to contact than those colleagues who worked in the same building or on the same campus. Nonetheless, in line with Burt (1992) and Jindal-Snape and Ingram (2013) these external links may be important for potential new information or a trusted perspective of how teaching practices at their institute might be slightly different, therefore providing a potential benchmark for discussion. Indeed, this insularity may be appropriate for organizations with highly valuable information, however, in other organizations such as charities and universities with very similar roles, an openness to sharing practice can minimize the time and money spent on the duplication of methods and encourage innovations and optimisation of practice. There is also a possibility as these were ECAs; they were still maintaining weak ties with their old institutions until they were able to establish strong ties at their new institution.

A final, important but mostly ignored finding in the social network literature, but this is more acknowledged in the transition literature (Jindal-Snape, 2016), is the role of participants’ partners for support in PD. Notably, several participants had strong ties with their partners with respect to sharing their teaching and learning practice. This is perhaps not surprising as they probably have strong bonding social capital and partners are able to provide emotional support to PD participants as well as professional support if the partner works in a similar organization. However, the organizational learning or sharing of information are extended beyond that of the organization and is being shaped by the employee’s partner rather than through the collective knowledge of the organization. The strength of the tie may suggest that there is a lack of mentors at a middle or senior management level to help with this offloading of emotion. As organizations are unlikely to “prohibit” participants’ sharing with their partners and external connectors, it may be worthwhile that organizations to take a wider holistic perspective in being a social enterprise (Lane and Down, 2010). By recognizing the importance of external social network formation of its employees, in particular the role of partners and colleagues at lower hierarchical levels in providing academic, professional and emotional support, senior management needs to recognize that management support and measuring the impact of PD may be more complex.

Limitations

A crucial limitation of our findings is that both closed and open social network analyses of learning and teaching networks were self-survey instruments, whereby socially desirable behavior might influence the results. However, a large body of research (Borgatti and Cross, 2003; Daly and Finnigan, 2010; Daly et al., 2010) has found that SNA techniques provide a robust predictor for actual social networks and PD programs, in particular given the high response rates (88%) and similar findings across two consecutive implementations of this PD program. Nonetheless, the framing of the SNA question (focussed on teaching and learning) might have restricted respondents’ recall of their network, in particular with senior management.

A second limitation is the accuracy of the data gathering process of job roles and hierarchical positions of external connectors using publicly available websites. Not all professionals keep their job information 100% up to date on their website or LinkedIn profile, although the increased competition amongst academics for scarce (funding) resources (Adcroft et al., 2010) almost requires academics to maintain a public web presence, which might mitigate some of these concerns. A third limitation is that we did not follow-up with the external connectors what kind of information and advice they were sharing with PD participants. Due to recall issues of social network interactions (Neal, 2008), perhaps the intensity of contact and types of information and support exchanged might be different than reported by PD participants. Future research is needed to determine whether reported informal network links by PD participants indeed provide the academic, professional and emotional support.

A fourth and perhaps most important limitation was the lack of qualitative data to understand the complex longitudinal transition experiences, such as for example done by Thomas et al. (2020b) who followed beginning teachers for a year and conducted a range of interviews over time with ECAs and more experienced academics. We also recognize that ECAs are not a monotonous group and their transition journeys from the PD would not be similar and may be dependent on their own unique circumstances and attributes such as their age, gender, race, nationality and discipline. However, this analysis was beyond the scope of our paper. Although we conducted previous qualitative focus group discussions (Rienties and Hosein, 2015), which highlighted that ECAs used the PD and external networks primarily for academic, professional, and emotional support, further longitudinal research would be needed to explore the long-term impacts of external connectors on ECA transitions based on their own unique characteristics. However, our quantitative analyses do indicate a (perceived) importance of those external connectors for allowing ECAs to transition in their new role.

Conclusion

Higher Education Institutions use specialized PD training to up-skill their ECAs to ensure they are competitive. The strength, number and type of external connections that these ECAs have can determine the extent and level that new knowledge from PD training is shared within the organization. As there is limited research in exploring these external connectors, this study examined with whom and to what extent that ECAs shared their PD experiences outside the training room. The results suggest that ECAs shared their knowledge quite widely but mainly with people they had a common identity, for example colleagues at a similar stage in career. The results also indicate that these ties tended to be male colleagues. Further, the intensity of knowledge sharing was positively related to sharing of knowledge with their partners and negatively related to senior management personnel. Further research should look at the social networks of mid-career employees, whether they are more likely to maintain ties from their early-career PD training, as well as, from their previous institutions.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for thist study will not be made publicly available. This is highly sensitive data about whom people learn and trust, which is very difficult to anonymize.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

BR collected and analyzed all the initial SNA data and web crawling data. AH double coded and independently verified the web crawling data. BR and AH contributed to the writing of this manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

While no specific funding was provided for this project, we do acknowledge the consistent support from Department of Higher Education at University of Surrey for conducting this and related research.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful for the support and contributions from the 114 ECAs who supported this research, and dedicated their time to complete the various surveys and questionnaires.

References

Adcroft, A., Teckman, J., and Willis, J. (2010). Is higher education in the UK becoming more competitive? Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 23, 578–588. doi: 10.1108/09513551011069040

Akkerman, S. F., and Bakker, A. (2011). Boundary crossing and boundary objects. Rev. Educ. Res. 81, 132–169. doi: 10.3102/0034654311404435

Almeida, R., and Carneiro, P. (2009). The return to firm investments in human capital. Lab. Econ. 16, 97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2008.06.002

Bartel, A. P. (2000). Measuring the employer’s return on investments in training: evidence from the literature. Ind. Relat. J. Econ. Soc. 39, 502–524. doi: 10.1111/0019-8676.00178

Bevelander, D., and Page, M. J. (2011). Ms. trust: gender, networks and trust—implications for management and education. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 10, 623–642. doi: 10.5465/amle.2009.0138

Borgatti, S. P., and Cross, R. (2003). A relational view of information seeking and learning in social networks. Manag. Sci. 49, 432–445. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.49.4.432.14428

Bresman, H. (2010). External learning activities and team performance: a multimethod field study. Organ. Sci. 21, 81–96. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1080.0413

Burt, R. S. (1992). Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 94, S95–S120.

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. London: Sage Publications.

Daly, A. J., and Finnigan, K. S. (2010). A bridge between worlds: understanding network structure to understand change strategy. J. Educ. Change 11, 111–138. doi: 10.1007/s10833-009-9102-5

Daly, A. J., Moolenaar, N. M., Bolivar, J. M., and Burke, P. (2010). Relationships in reform: the role of teachers’ social networks. J. Educ. Admin. 48, 359–391. doi: 10.1108/09578231011041062

Davison, H. K., Maraist, C., and Bing, M. (2011). Friend or foe? The promise and pitfalls of using social networking sites for HR decisions. J. Bus. Psychol. 26, 153–159. doi: 10.1007/s10869-011-9215-8

Edmondson, A. C. (2002). The local and variegated nature of learning in organizations: a group-level perspective. Organ. Sci. 13, 128–146. doi: 10.1287/orsc.13.2.128.530

Finkelstein, M., Walker, E., and Chen, R. (2013). The American faculty in an age of globalization: predictors of internationalization of research content and professional networks. High. Educ. 66, 325–340. doi: 10.1007/s10734-012-9607-3

Froehlich, D. (2020). “Mapping Mixed Methods Approaches to Social Network Analysis in Learning and Education,” in Mixed Methods Approaches to Social Network Analysis, eds D. Froehlich, M. Rehm, and B. Rienties (London: Routledge), 13–24. doi: 10.4324/9780429056826-2

Froehlich, D., Rehm, M., and Rienties, B. (2020). Mixed Methods Approaches to Social Network Analysis. London: Routledge.

Jindal-Snape, D. (2010). Educational Transitions: Moving Stories from Around the World. Abingdon: Routledge.

Jindal-Snape, D., and Ingram, R. (2013). Understanding and supporting triple transitions of international doctoral students: ELT And SuReCom models. J. Perspect. Appl. Acad. Pract. 1, 17–24.

Jindal-Snape, D., and Rienties, B. (eds) (2016). Multi-Dimensional Transitions of International Students to Higher Education. London: Routledge.

Jippes, E., Steinert, Y., Pols, J., Achterkamp, M. C., Van Engelen, J. M. L., and Brand, P. L. P. (2013). How do social networks and faculty development courses affect clinical supervisors’ adoption of a medical education innovation? An exploratory study. Acad. Med. 88, 398–404. doi: 10.1097/acm.0b013e318280d9db

Jones, A., Lygo-Baker, S., Markless, S., Rienties, B., and Di Napoli, R. (2017). Conceptualizing impact in academic development: finding a way through. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 36, 116–128. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2016.1176997

Kalyani, R. R., Yeh, H. C., Clark, J. M., Weisfeldt, M. L., Choi, T., and Macdonald, S. M. (2015). Sex differences among career development awardees in the attainment of independent research funding in a department of medicine. J. Women’s Health 24, 933–939. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5331

Kirkpatrick, D. L., and Kirkpatrick, J. D. (2006). Evaluating Training Programs. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Lane, D. A., and Down, M. (2010). The art of managing for the future: leadership of turbulence. Manag. Decision 48, 512–527. doi: 10.1108/00251741011041328

Lee, M. (2010). Researching social capital in education: some conceptual considerations relating to the contribution of network analysis. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 31, 779–792. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2010.515111

Lin, N. (2001). “Theories of capital,” in Social Capital: Theory and Research, 4 Edn, eds N. Lin, K. S. Cook, and R. S. Burt (New Jersey: Transaction Publisher), 3–18.

Mittelmeier, J., Edwards, R., Davis, S. K., Nguyen, Q., Murphy, V., Brummer, L., et al. (2018). ‘A double-edged sword. This is powerful but it could be used destructively’: perspectives of early career researchers on learning analytics. Front. Learn. Res. 6:20–38.

Moolenaar, N. M., Daly, A. J., and Sleegers, P. J. C. (2010). Occupying the principal position: examining relationships between transformational leadership, social network position, and schools’ innovative climate. Educ. Admin. Q. 46, 623–670. doi: 10.1177/0013161x10378689

Moolenaar, N. M., Sleegers, P. J. C., and Daly, A. J. (2012). Teaming up: linking collaboration networks, collective efficacy, and student achievement. Teach. Teach. Educ. 28, 251–262. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2011.10.001

Neal, J. W. (2008). “Kracking” the missing data problem: applying krackhardt’s cognitive social structures to school-based social networks. Sociol. Educ. 81, 140–162. doi: 10.1177/003804070808100202

Pataraia, N., Falconer, I., Margaryan, A., Littlejohn, A., and Fincher, S. (2014). “Who do you talk to about your teaching?”; networking activities among university teachers. Front. Learn. Res. 2:4–14.

Pataraia, N., Margaryan, A., Falconer, I., and Littlejohn, A. (2013). How and what do academics learn through their personal networks. J. Further High. Educ. 39, 336–357. doi: 10.1080/0309877x.2013.831041

Putnam, R. D. (2001). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Rehm, M., Cornelissen, F., Notten, A., Daly, A., and Supovitz, J. (2020). “Power to the people?! Twitter discussions on (educational) policy processes,” in Mixed Methods Approaches to Social Network Analysis, eds D. Froehlich, M. Rehm, and B. Rienties (London: Routledge), 231–244. doi: 10.4324/9780429056826-20

Rehm, M., Gijselaers, W., and Segers, M. (2014). Effects of hierarchical levels on social network structures within communities of learning. Front. Learn. Res. 2:38–55.

Rienties, B., Brouwer, N., and Lygo-Baker, S. (2013). The effects of online professional development on higher education teachers’ beliefs and intentions towards learning facilitation and technology. Teach. Teach. Educ. 29, 122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2012.09.002

Rienties, B., and Hosein, A. (2015). Unpacking (in)formal learning in an academic development programme: a mixed-method social network perspective. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 20, 163–177. doi: 10.1080/1360144X.2015.1029928

Rienties, B., and Kinchin, I. M. (2014). Understanding (in)formal learning in an academic development programme: a social network perspective. Teach. Teach. Educ. 39, 123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2014.01.004

Roxå, T., Mårtensson, K., and Alveteg, M. (2011). Understanding and influencing teaching and learning cultures at university: a network approach. High. Educ. 62, 99–111. doi: 10.1007/s10734-010-9368-9

Skryme, G. (2016). ““It’s about the journey, it’s not about uni”: chinese international students learning outside the university,” in Multi-Dimensional Transitions of International Students to Higher Education, eds D. Jindal-Snape and B. Rienties (London: Routledge), 91–105.

Spurk, D., Kauffeld, S., Barthauer, L., and Heinemann, N. S. R. (2015). Fostering networking behavior, career planning and optimism, and subjective career success: an intervention study. J. Vocat. Behav. 87, 134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2014.12.007

Stes, A., Min-Leliveld, M., Gijbels, D., and Van Petegem, P. (2010). The impact of instructional development in higher education: the state-of-the-art of the research. Educ. Res. Rev. 5, 25–49. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2009.07.001

Thomas, L., Rienties, B., Tuytens, M., Devos, G., Kelchtermans, G., and Van Der Linde, R. (2020a). Unpacking the dynamics of collegial networks in relation to beginning teachers’ job attitudes. Res. Pap. Educ. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2020.1736614

Thomas, L., Tuytens, M., Devos, G., Kelchtermans, G., and Vanderlinde, R. (2020b). “Unpacking the collegial network structure of beginning teachers’ primary school teams: a mixed method social network study,” in Mixed Methods Approaches to Social Network Analysis, eds D. Froehlich, M. Rehm, and B. Rienties (London: Routledge), 139–158. doi: 10.4324/9780429056826-14

Thomas, L., Tuytens, M., Devos, G., Kelchtermans, G., and Vanderlinde, R. (2019). Beginning teachers’ professional support: a mixed methods social network study. Teach. Teach. Educ. 83, 134–147. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.04.008

Törnberg, P., and Törnberg, A. (2020). “Minding the gap between culture and connectivity: laying the foundations for a relational mixed methods social network analysis,” in Mixed Methods Approaches to Social Network Analysis, eds D. Froehlich, M. Rehm, and B. Rienties (London: Routledge), 58–71. doi: 10.4324/9780429056826-7

Uttl, B., White, C. A., and Gonzalez, D. W. (2017). Meta-analysis of faculty’s teaching effectiveness: student evaluation of teaching ratings and student learning are not related. Stud. Educ. Eval. 54, 22–42. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2016.08.007

Van Den Bossche, P., and Segers, M. (2013). Transfer of training: adding insight through social network analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 8, 37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2012.08.002

Van Waes, S., De Maeyer, S., Moolenaar, N. M., Van Petegem, P., and Van Den Bossche, P. (2018). Strengthening networks: a social network intervention among higher education teachers. Learn. Instruct. 53, 34–49. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2017.07.005

Wassermann, S., and Faust, K. (1994). Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Keywords: professional development, early-career, transition, social network analysis, web crawling

Citation: Rienties B and Hosein A (2020) Complex Transitions of Early Career Academics (ECA): A Mixed Method Study of With Whom ECA Develop and Maintain New Networks. Front. Educ. 5:137. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00137

Received: 02 March 2020; Accepted: 06 July 2020;

Published: 28 July 2020.

Edited by:

Ting-Chia Hsu, National Taiwan Normal University, TaiwanReviewed by:

Deepak Gopinath, University of the West of England, United KingdomCristina C. Vieira, University of Coimbra, Portugal

Copyright © 2020 Rienties and Hosein. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bart Rienties, YmFydC5yaWVudGllc0BvcGVuLmFjLnVr

Bart Rienties

Bart Rienties Anesa Hosein

Anesa Hosein