95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Educ. , 23 July 2020

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 5 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.00119

This article is part of the Research Topic Towards a Meaningful Instrumental Music Education. Methods, Perspectives, and Challenges View all 21 articles

For approximately the past 30 years, we have been witnessing a re-emergent interest in learner voice from researchers, teachers, policymakers, and students themselves. This widespread movement foreshadows the potential for a shift of paradigm from a unilateral top-down directivity to an inclusive and dialogical decision-making process in school systems. Youth voice is crucial to reimagine education from a global, multi-stakeholder perspective, which can foster student engagement and promote meaningful learning experiences. While the interest on the learner voice has burgeoned recently in the field of music education, the body of literature in this field is still relatively small, and its impact in the classroom and policies is limited. That said, a few research studies have been led to study specifically the learner voice in music, both in- and out-of-school contexts. However, so far, we have not encountered any systematic attempt to integrate these findings into a broader framework, depicting the diversity and the commonalities of the young learner voice in music education. To bridge this gap, we completed a systematic literature review of the research studies that capture the essence of young music learner voices, a corpus mostly comprised of narrative and storytelling studies. We carried out a thematic analysis to explore how young music learners describe their own musical experiences and meaning-making in informal and formal musical contexts. The results emerging from this systematic literature review are organized into a framework representing young learners' perspectives on what they like and dislike about their musical experience. We propose practical implications resulting from this analysis for innovative pedagogical approaches and policies in music education, where the learner voice is inclusively engaged in a dialogical decision-making process. Finally, we explore avenues for promoting a more significant inclusion of learner voice in music education and research.

In the past 30 years, researchers, teachers, policymakers, and students themselves have demonstrated a re-emergent interest in learner voice (Cook-Sather, 2006). This growing interest coincides with the endorsement of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child by the United Nations General Assembly in 1989 (Mockler and Groundwater-Smith, 2015). One of the four principles stated in that convention is “respect for the views of the child,” which implies that the voice of the child is not only listened to but also taken into consideration in the decision-making process—a proposition that closely parallels the definition of the learner voice that we adopted (below). The burgeoning of interest for the learner voice is manifested, for example, by the creation of organizations such as Student Voice (https://www.stuvoice.org/), and initiatives such as involving students in school councils as part of school improvement programs (Whitty and Wisby, 2007).

The learner voice would benefit both the learners and the learning environments in promoting the development of 21st-Century skills in a context that adapts to the reality and needs of the learners today (and tomorrow). In that direction, Mockler and Groundwater-Smith (2015) argue that engaging in a dialogue with young people is a prerogative “if we are to realize the democratic, pedagogical and social aims of education in the 21st century” (p. 5). The learner voice movement foreshadows the potential for a paradigm shift from a unilateral top-down directivity to an inclusive and dialogical decision-making process in learning environments (Rudduck, 2007), where the learners are not only democratically involved but also made responsible for their own learning. This process is based on two mechanisms: (1) “a practical agenda for change” where the traditional deciders (e.g., the teachers) have the opportunity to better understand the learner's point of view and (2) “an important shift in the status of students […] and in the teacher-student relationship” where the students play an active (rather than passive) role in a more collaborative and less hierarchical “partnership” with their teachers (Rudduck, 2007, p. 587). Taking into consideration, the young person's voice is a philosophical position based upon the belief that children and teenagers are true “beings” (and not just “becomings”), and that their ideas and perceptions are valuable (Bragg, 2010).

While the interest on the learner voice has burgeoned recently in the field of music education1, the body of literature in this field is still relatively small, and its impact in the classroom and policies is limited (Spruce, 2015). That said, a few research studies have been led to study specifically the learner voice in both in- and out-of-school contexts. However, no systematic attempt to integrate these findings into a broader framework, depicting the diversity and the commonalities of the young learner voice in diverse music education contexts, has been made thus far. Hence, we don't have access to a general picture of the musical learner voice of the 21st-century which would inform researchers, educators, and policymakers about the interests, values, and needs of these learners; a picture that could, in turn, allow these professionals to adopt better-informed practices and policies. Furthermore, at the moment, we don't know to what extent the learner voice is listened to (or not) and taken into consideration (or not) in the fields of music education and research, both in and out of school.

This literature review aims to present the actual picture of the state of knowledge of the learner voice in music and to offer insights for future initiatives in that domain. In order to achieve this objective, we reviewed the literature in music where the learner voice is quoted integrally, as we are primarily interested in the learner's (and not the researcher's) perspective of music. We then carried a thematic analysis (Kuckartz, 2014) on the integral quotes from music learners, in order to address the following research question: “What are young music learners saying about their musical experience?”

The link between the formal/informal notions and the learner voice might not be obvious at first glance, but it is underlying many aspects relevant to the learner voice in music education. This is a complex topic that will only be briefly addressed here as it is not central to our chapter2. Still, some elements of the formal/informal framework in music education can help to provide a better understanding of what learners express about their musical experience. First of all, it is worth noting that the formal/informal notions are not dichotomous; they fall on a continuum (Folkestad, 2006). Secondly, various components of the teaching and learning process can be qualified using the formal/informal framework (Folkestad, 2006). We will discuss two of them: context and source of learning. On one end of the spectrum, formal context would refer to learning that takes place within the wall of an institution (e.g., school band). On the other end of the spectrum, informal context would be learning that takes place out-of-school (e.g., a garage band; Folkestad, 2006). For its part, formal source of learning would be teacher-led while informal source of learning would be self- or peer-led (Green, 2002, 2008; Jenkins, 2011). These two dimensions are related, but a single learning experience is not always on the same position on the formal-informal continuum for both context and source of learning; informal source of learning can occur within a formal context and vice-versa. Finally, analysis of real-life learning situations reveals that the boundaries between the formal and the informal are rarely clear-cut; they are often blurred and subject to various points of view (Folkestad, 2006).

Throughout the world, including the United States, educational systems are based on adults' ideas about teaching and learning (Cook-Sather, 2002). In most schools today, only adults are responsible for the curriculum design (Biddulph, 2011). In fact, all dimensions of the learning environments (from the architectural design to the school report card) are, in most cases, determined, elaborated and reformed without consulting the ones that they are designed to serve (Cook-Sather, 2002). The inadequacy of this situation has been decried by several authors (namely by Cook-Sather, 2002; Mitra, 2014; Ozer, 2017) especially considering the context of the acceleration of social, environmental and technological changes, characterizing the 21st-century.

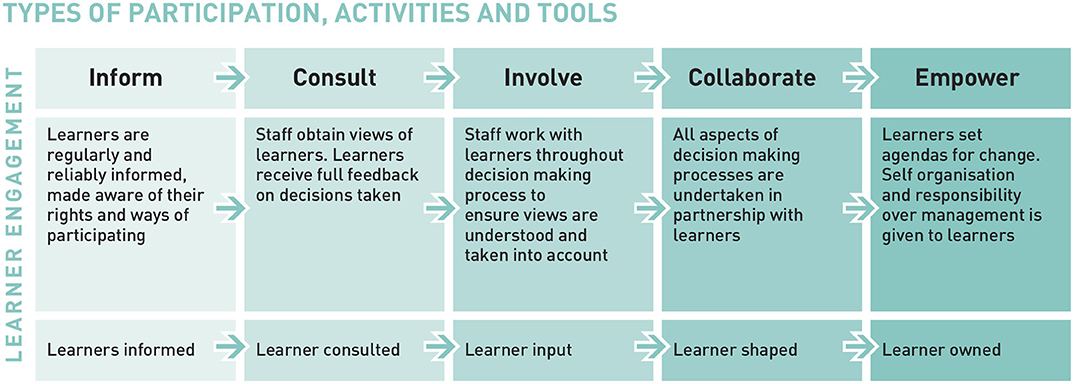

Listening to the learner voice implies rethinking established practices and authorities; decisions that were once taken by adults in silos are now discussed with the learners and, perhaps more importantly, their inputs can result in effective transformations. That being said, in the literature and in practice, diverse modalities have been labeled as “student voice” initiatives. As shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Levels of learner voice participation [partial figure] (Rudd et al., 2006, p. 13).

This model highlights how the learner voice can vary extensively in practice. On one end of the continuum, it could manifest itself in a non-participative, passive mechanism (Inform), which we could argue is not an authentic learner voice (more on this later) to, on the other end, self-determination (Empower). In view of the wide range of manifestations of the learner voice, how can this broad concept be defined?

In most cases, “student voice” refers to school environments. For example, Mitra describes the student voice as: “the many ways in which youth have opportunities to share in the school decisions that will shape their lives and the lives of their peers” (Mitra, 2008, p. 221). This definition, which is affirming the diversity of the student voice, is a good starting point for the discussion although it is restricted to the school context. However, as learning can occur in diverse settings, including community, education, and research, we argue that the “learner voice” can be heard and be part of the dialogue both in and out-of-school. Consequently to this postulate we propose the following definition of the learner voice: the process by which learners are listened to, consulted, included, take part, or take charge of the decision-making process or take action about their learning or their education in diverse contexts.

In July 2019, a Google Search with the query “Student voice” returned more than 2,000,000 results, while “Pupil voice” returned about 335,000 results and “Learner Voice” just above 80,000 results. Those requests, intentionally conducted without any domain specificity, offer a general insight of the popularity of the expression “Student voice” over “Learner Voice,” with a frequency that is approximately 25 times higher for the former. While conscious of the apparent consensus in favor of the expression “Student voice,” our preference for the expression “Learner voice” is not fortuitous and reflects our intention to broaden the contexts in which it can be part of the conversation. In the same fashion, as a learner doesn't, in fact, need to be a student to learn, there is absolutely no certitude that being a student effectively leads to learning (still, we acknowledge it does … in some instances). Hence, we prefer to use the expression “Learner Voice” throughout this chapter because it is concerned about what individuals who are engaged in learning, wherever it occurs—inside or outside the walls of an institution have to say about their learning. This position is also echoed in Walker and Logan (2008) who, after conceding that “student voice” and “pupil voice” are the most used expressions, prefer to use “learner voice” “to encourage debate on ‘who' the learner actually is, as today, the student (both adult and young), the teacher or even their parents are now often referred to as ‘learners' whose voices should be heard and acted upon” (p. 2). In this chapter, we focus on the young learner voice, “young” is broadly defined as under 18 years old, the age of majority in more than half of the countries of the world. However, we want to underline that, since learning can occur anywhere and at any age, the learner voice can be a useful concept in more diverse populations and settings, including, but not limited to, teachers, employees in a company or elderly learners.

Learner voice is crucial to reimagine education from a global, multi-stakeholder perspective. Not only listening to what young people have to say about their education, but also looking at how they can take on effective actions, can lead to improved teaching practices (Commeyras, 1995; Fielding and Bragg, 2003; Cook-Sather, 2009), and provide a sense of empowerment to the student and increase their motivation toward their education (Rudduck, 2007; Walker and Logan, 2008; Mitra, 2014). Even if this approach involves in-depth questioning of the actual modes of operation of our education systems, which can provoke resistance from stakeholders who find comfort in the policies that have prevailed for decades, learner voice initiatives can positively impact on the learner, their teachers/guides/facilitators, and their learning environment. Firstly, learner voice can foster student engagement and promote meaningful learning experiences (Walker and Logan, 2008). For example, it can lead learners to develop “greater sense of ownership over their learning, increased motivation, improved self-esteem, greater achievement, improved relationships with peers and educators and increased self-efficacy” (Walker and Logan, 2008, p. 2). Moreover, by taking an active role in decision-making and increasing their sense of agency, learners can experience a greater sense of responsibility and ability to communicate, which are crucial 21st-century skills (P21, P21). Less frequently discussed in the literature is the concept that teachers/guides/facilitators—which we will call “guides” from now on—can also benefit greatly from the learner voice. Effectively, listening to their voice, guides can build a new partnership with learners and, by receiving authentic feedback on their educational practice, develop more efficacious teaching skills or, in an ideal scenario, receive learners' confirmation that what they thought worked, actually worked effectively (Fielding and Bragg, 2003). Learner voice can also positively impact learning environments: when the learners are actively involved in the decision-making process, they tend to develop an increased sense of identity in their learning environment and build links with institutions outside their school, which benefits school reputation, image and dynamism (Fielding and Bragg, 2003).

Benefiting from the potential positive effects of the learner voice requires the implementation of best practices. Robinson and Taylor identified four “core values” of the learner voice:

1. A conception of communication as dialogue;

2. The requirement for participation and democratic inclusivity;

3. The recognition that power relations are unequal and problematic; and

4. The possibility of change and transformation (Robinson and Taylor, 2007, p. 8).

Following this model, authentic learner voice initiatives allow for two-way exchanges between teachers and students, are participatory and inclusive, challenge established power relations and allow for effective changes. That is to say that merely collecting students' feedback and not taking their ideas into consideration is not authentic learner voice.

Despite the growing interest in the learner voice observed in the scientific literature (Gonzalez et al., 2017), the literature centered on the learner voice in music remains scarce (Spruce, 2015). Although this area is still relatively fallow in music, we consider the importance of reviewing the literature to draw a picture of the actual state of knowledge about the learner voice in music. The following questions were addressed:

1. What can we learn from the actual research on the learner voice in music?

2. How can the actual state of knowledge about the learner voice in music inform teaching and learning practices, and guide further research in that field?

To address these questions, we completed a systematic literature review of the empirical research studies on the learner voice in music.

We consulted four databases (ERIC, RILM, Music Index, and Education Source) between the 11th and the 14th of June 2019. The research criteria were: (“student voice” OR “learner voice” [in: all fields]) AND music [in: subject]. Only peer-reviewed research studies were retained. At this stage, a total of 47 records were found; 39 records remained after excluding duplicates (see Table 1).

We conducted a second search, with similar criteria, with (“pupil voice” [in: all fields]) AND music [in: subject]. Table 2 presents search results in each database.

We then screened our results, using the following criteria:

a) The source is peer-reviewed, written in English and published after 2005;

b) The main theme of the research study is music;

c) The source comprises integral and significant quotations from young musicians about music.

We purposefully restrained our keywords to include only research studies that explicitly investigated the student/learner/pupil voice in music. As our intention was to draw a picture of the actual state of knowledge in this domain, we focused on the literature that has been published within the last 15 years.

Only 7 records matched our criteria: Countryman (2009); Howell (2011); Lowe (2012); Evans et al. (2015); Black (2017); Kokotsaki (2017) and Lowe (2018).

We coded all the excerpts where the learner voice was quoted integrally in the retained literature, using NVivo 12 software (Mac version). Quotes that were not standalone (i.e., those not meaningful when taken out of the source) were excluded. Only the young person quotations were analyzed, to avoid influences from original researcher interpretation. Our objective was to re-analyze the data and leave out, to the extent possible, the initial researcher perspective and stay as close as possible to the learners' words. Given the limited quantity of sources retained, we chose to analyze the literature in a two-step process. Firstly, we adopted a micro approach, analyzing each paper individually in order to bring to light the key elements that emerged from each source retained. Secondly, we adopted a macro approach, looking at the literature from a transversal and synthetic perspective, to identify the recurring themes in our corpus. That is to say that we searched for recurring themes throughout the sources retained and organized them into broad categories. This multi-stage process of categorization and coding is described in detail below. Thirdly, after our main analysis was completed, we read all sources in their entirety in order to identify the main methodological characteristics, population, context and research objective of each study (as presented in Table 3). These studies encompass a wide range of music-making practices, thus offering a multiperspective understanding of the learner voice in music.

After coding all the participants' quotations, we ran a word frequency request to get an initial overview of our data. The fifty most frequent words in all the participants' quotes are shown in Figure 2.

We grouped these words into main themes. The frequency of the first word on the list determines the position of the main theme (e.g., “like” appeared more frequently than “music” so “pleasure or well-being” appears before “music”). The words listed under each main theme appear in order of frequency of appearance. All the words that were not meaningful when taken out of context were regrouped under the category “ambiguous or less significant.” The themes (excluding “ambiguous or less significant” words) that can be derived from the music learners voice 50 most frequent words were, in order of importance, related to (1) pleasure or well-being; (2) music; (3) action; (4) learning environment; (5) people; (6) desire and (7) receptivity. See Table 4 for more details on this categorization.

After running the word frequency search, which offers a surface perspective on our data, we moved toward a more in-depth approach. We did an initial thematic analysis of our data, using an inductive categorization. That is to say that all the learner quotes were coded using an open structure, creating new categories for each emerging theme. The categorization tree was developed, structured and refined throughout the coding process. All quotes relating to music, either directly or indirectly, were coded in order to explore how young music learners describe their musical experiences.

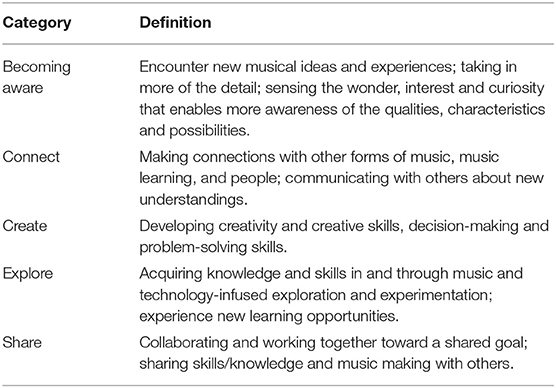

After reviewing the resulting categorization tree and our coded extracts, we realized that the O'Neill (2016) framework3 could provide a valuable, transversal perspective on our data. An adaptation of the five categories she proposed, effectively encompassed most recurring themes in our sources, thus providing an appropriate lens for a better understanding of the student voice in music. See Table 5 for the five categories from her model, along with their definitions.

Table 5. O'Neill (2016) categorization [adapted].

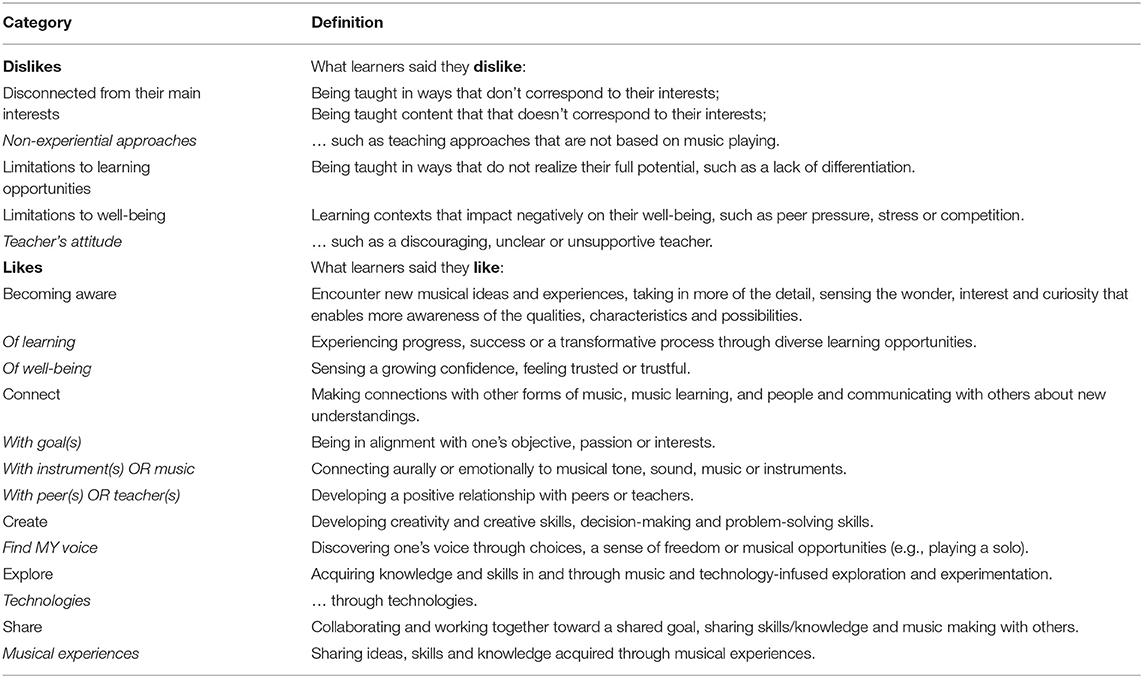

Using this basic, five items, categorization, we completed a second coding pass of all excerpts by recoding all the learners' quotes using a mixed coding approach (L'Écuyer, 1987). In other words, we used an initial categorization tree (i.e., O'Neill's framework) in conjunction with the possibility to create new nodes throughout the process, adding new categories and sub-categories when deemed relevant. During this categorization process, we realized that all the categories comprised in the O'Neill framework were related to what learners liked, so they were grouped under that parent category. We also encountered several quotes where learners explicitly described what they disliked, hence we created this second parent category. We also created a few sub-categories under the dislikes: disconnected from their main interests, non-experiential approaches, limitations to learning opportunities, limitations to well-being and teacher's attitude, and under the five categories from the initial O'Neill categorization: of learning, … opportunities, of well-being, with goal(s), with instrument(s) OR music, with peer(s) OR teacher(s), find MY voice and technologies). These subcategories offered a greater degree of precision for the salient themes encountered in our corpus. Our final categorization resulted in a dichotomous framework, opposing what the learners liked to what they disliked about music, music-making, and music-learning. Table 6 presents our final categorization tree along with the definition of each category.

Table 6. Final categorization based on O'Neill (2016).

The literature is initially analyzed from a micro perspective, discussing what stood out from each research paper. Then, all sources are discussed from a transversal perspective, synthesizing the views of young music learners about what contributes to and impacts on, their musical engagement and the meaningfulness of their musical experience.

We kept a journal while coding our sources. In the journal, we noted the themes that stood out from the learner voice for each paper. After coding was finished, we confronted our coding with the notes in our journal, attempting to grasp the salient elements in the discourse of the learners. Here, the frequency of occurrences of each theme was less important to us than how striking a peculiar quote was or what could be understood between the “lines” of the learner voice.

Black documented the lived experience of a secondary school jazz combo through interviews (N = 3). First of all, this study revealed that building confidence (coded under the category well-being) was an important and valuable consequence for the learners participating in a jazz ensemble. Learners also mentioned that they valued learning and sharing their learning with their peers. Also, the importance of relationships, horizontal decision-making and shared purpose were strongly emphasized by the participants. On a less positive note, the learner voice also implicitly suggested that traditional teacher-centered learning promotes teacher dependency, even when manifested in a less formal context: “You've never been taught to do this, so how can you expect to be able to do it? [laughs] You can't” (p. 351). This quote implicitly reveals the student's belief that learning always occurs through teaching—and that it cannot be self-directed. Hence, despite all the perceived benefits of participating in a jazz combo project, it might also have lesser desirable outputs such as involuntarily leading the learner to interiorize that one can't learn by himself.

Countryman studied the experiences of students involved in high school music programs. She interviewed 33 former high school students (aged 19–25), 1–6 years after their high school graduation. The salient theme emerging from her research is the high value learners placed on the social connections that initiated and created through music participation. The participants in this research seemed to be relatively engaged in their music learning, but the glue that held most of them together and kept them involved in their music program was their social relationships. Social connections were so essential for some that they explicitly insisted on the fact that, for them, friends are more important than music, for example:

“(JC [Researcher]: Why did you continue with the band all the way through high school?) Consistency, for one thing. I'd been doing it for so long ~and the stigma of walking away ~ if I walked away from it I'd be walking away from my friends. It was all about the friends, not about the music.” (p. 94)

“I was there because of my friends. I got the music because of it.” (p. 95)

“I liked being a part of a musical group. I liked the kind of music we played, and also just the people. I had a lot of friends in music that had been in the orchestra since junior high. So, you have your friends in the group and it's fun.” (p. 95)

An interesting explanation for this process of bonding through music-making from one learner is that it implies sharing emotions with others, as explained in the following excerpts: “I was so close with those people because you're displaying emotion every single day” (p. 105) and “There was the shared experience of going through this together” (p. 94). Still, for some learners, the social bonding that was prevalent between them and their peers was not necessarily present with their teacher: “the conductor was not part of the equation at all ~ not on the same playing field.”

Other elements that appeared to be highly valued by the participants of this research were the ideas of: finding their own voice, empowerment and ownership. While some high school music programs adopted a traditional teacher-directed model, other programmes were encouraging students' initiatives, such as choosing repertoire or self-leading rehearsals. In that direction, learners emphasized the importance of playing the music they wanted to play:

“Jazz night in Grade 11. we had the round tables and candles. that was my first occasion where I performed in a small combo that we totally did by ourselves. KN chose the song and we rehearsed all on our own – I absolutely loved it. That was my favorite situation of all time.” (p. 102)

Many of them also discussed how soloing was important to them, for example:

“It was just so fun. It wasn't just fun. it was more than that ~like the first time I ever had a solo people just went nuts. They said things like ‘I didn't know this was in you!' I didn't know this was in me! That's a good feeling to have.” (p. 101)

Finally, participants in this research valued music for its experiential nature, for example: “And I think you have a lot to talk about, because music ~ it's a lot more out of school ~ it's music! Unlike other courses, music is more of an experience” (p. 105).

Evans et al. studied the implementation of an informal music learning approach (Musical Futures) in three secondary schools in Wales. They conducted 4 focus group interviews with groups six to eight learners (aged 11–14). The learners involved in this project reported a positive experience overall. Quotes from learners show how they globally valued their informal learning experience, namely because it involved playing music that they liked: “It's just, like, all the bands we listen to—it's good being able to play what they can play” (p. 7) making choices and learning various skills. This positive value is also manifested by the sense of engagement many learners participating in this study expressed toward their music learning. For example, the following quote illustrates how young learners were engaged enough in music to form their own garage band: “We started off practicing at lunchtime in the practice rooms but that, couldn't get much done in the hour so we started doing it out of school then so/ [interrupted]. Learner 2: In a garage [laughs]. Learner 1: In a garage—the neighbors don't really like us” (p. 10).

However, despite a globally positive experience, the project was not without tension. One prominent cause of tension was the perceived differences in terms of musicianship between peers:

“It's a lot more difficult when umm, there's only one person in that group whose only got the weakest point and it's like everyone else is stronger at their own—that's when it gets a bit tricky, because that's when it seems to build a bit of an argument about it because we can't really swap because the whole group has found their strong point but there's always one person who still hasn't found their strongest point yet.” (p. 11)

Howell studied music-making and musical understanding among newly arrived immigrant and refugee children. More specifically, she interviewed three newly arrived children (aged 11–14) attending Melbourne English Language School in Australia who experienced composition (songwriting) activities. Participants in this research mainly described factually their learning experience. Yet, the learners described how they valued composing, for it meant creating their own music:

“The music we play… it comes from our heads, not from a book…” (p. 37)

“We think it up by ourselves. We do it by ourselves.” (p. 37)

These perceptions of ownership contributed to the participants' positive appreciation of their music-making experience.

Kokotsaki studied the pupil voice and attitudes to music during the transition to secondary school in six schools from the North East of England. Three of these schools where data collection took place were selected for the transition strategies they had in place and were labeled as “good practice” schools. The remaining three schools had no such strategies in place and were labeled as “need to improve” schools. Kokotsaki used a mixed method approach combining focus group interviews and the Attitudes to Music questionnaire. The qualitative data we re-analyzed here are based on 97 focus-group interviews, with 4–5 pupils in each group (the pupil's age is unspecified, but they are in Year 7, which usually corresponds to 11–12 years old).

The salient theme in this research is that learners place a high value on music, especially when it is taught from an informal approach, for example: “I love it when we do practical work but not when we do work (writing)” (p. 11). They seem to enjoy the experiential dimension of music: collaborating, playing, practicing and learning various instruments. However, learners seem to be often taught with formal teaching approaches, which are associated with what they dislike about their music lesson, such as sitting, writing, hard work and tests: “Our first teacher was better—now we're just doing piano and we used to get out the drums and the tambourine and all that; the teacher let us be our own musician” (p. 32). Directive teaching approaches centered on a single instrument and/or paper and pen activities appeared to be detrimental to learner's appreciation of their school music lessons.

Lowe studied the values and beliefs that students in their first year of secondary school attached to learning an instrument, and the impact of the instrumental lesson upon these values and beliefs. He conducted eight focus groups with 48 students (aged 12–13) from Australia. What stands out in this paper is the link between learners' appreciation (or not) of their teacher and the value they place on music. Positive teacher attitudes and competencies appear to be strongly correlated with musical engagement:

“I like to go to lessons because my teacher is really nice and he's an inspiration to us all. My saxophone teacher, he plays the instrument like really, really well so he always plays to me, like how he plays, like really, really good pieces so that I can know how I will sound maybe 1 day if I keep practicing and stuff—it's sort of like inspiring.” (p. 11)

However, in the opposite direction, perceptions of teacher incompetency or poor pedagogical approach leads learners to disengagement:

“In my first year in Year 6, the first year I was playing, we had a really bad teacher and he always just set lots of homework and he wouldn't do very much at all. He didn't bring his trumpet in so he didn't play it at all, he'd just tell us what to do. And there was about…there was five people offered the position of the trumpet. Everyone took it up and then by the end of the year there was only two left. Lots of people had just quit and dropped out and I was actually thinking about it until I asked in the office and they said we were getting a different teacher for next year. So that's the only reason I stayed.” (p. 15)

In this research study, Lowe examined students' feedback following participation in an alternative large-scale cooperative music ensemble festival in comparison to traditional competitive festivals. More precisely, the author defines a competition-festival as a school ensemble contest where the performances standards are rated externally. For its part, a cooperative festival is defined as a music ensemble event focused on enjoyment, cooperative and motivational outcomes and where the performances are unrated. This research was conducted in Australia. A total of 345 students completed a survey comprising 21 items and a section for comments. All of the students surveyed had just participated in a cooperative-festival and most of them had participated in a competition-festival in previous year. As the subject of this last research is very specific, discussing the impact of a singular, punctual event, it conveys less transferable data. Still, what can be perceived from the learners' voice in this study is that they appreciate being part of a large, good-sounding ensemble with friends and listening to high-achieving musicians as a source of inspiration.

As shown in Figure 3, all categories that pertained to the “dislikes” can be related to a mirror category within the “likes.” That is to say that overall, most learners were consequent; when considering an element as positive, they also described its opposite as negative. For example, learners quite eloquently described how they liked becoming aware of learning:

“Before I could only play the guitar, but when I came here I could play the drums, piano and guitar.” (in Kokotsaki, 2017, p. 13)

“I enjoy playing the piano, learning new music, singing.” (in Kokotsaki, 2016, p. 22)

“I'm happy to adapt now, and this is not even as a musician, this is just in general. I wouldn't say before the combo, I was particularly adaptable, I would just kinda do what I was gonna do, no matter what.” (in Black, 2017, p. 348)

“[…] learned loads of things. I've no idea how to read music [inaudible] but, like, I go on YouTube and I, umm, I search for things but then, I also make my own music as well.” (in Evans et al., 2015, p. 13)

As shown in the previous examples, learning in the music lesson can be highly varied. In addition to the expected (and recurrently mentioned throughout the retained sources) learning of instruments or new songs, some participants also mentioned learning to adapt to diverse situations and transferring this skill into their “normal” (non-musical) life. Other participants discussed acquiring the ability to be autonomous in their music learning and to learn songs by ear. An overarching perception, shared among the majority of participants, is that musical learning experiences are enjoyable and generate excitement:

“I think I haven't stopped learning things from first year up until now. I'll probably keep going until whatever stage … I mean, if combo hadn't taken place, that band probably wouldn't exist, so that's really cool [laughs].” (in Black, 2017, p. 352)

For many learners, experiential approaches seem to be correlated to the perceived value of their learning experiences.

“In English, you do a lot of writing and study techniques. In music, you still have lots to remember but you do this by practicing and experiencing them rather than writing them down.” (in Kokotsaki, 2016, p. 22)

“Music is one of the most interactive subjects.” (in Kokotsaki, 2017, p. 22)

Despite the wide variety of contexts studied in the sources we retained, there were very few apparent zones of conflict in the learner's discourse. Effectively, beyond their age or the context of the research they took part in, they were on the same page on the vast majority of topics they discussed. More precisely, in all the excerpts, two topics emerged as potential zones of disagreement: liking inclusivity vs. disliking wasting time and liking playing keyboards vs. disliking playing only the keyboard.

First of all, many participants evoked an appreciation for the inclusivity of their musical experience, where everyone was welcomed to participate and accepted as a whole, with their strengths and weaknesses. For example:

“Music's a haven for people that, even if they aren't accepted socially you know, they go to anything in music and they are accepted. That's why I loved that life. Everyone in music is interesting. Everyone in music got there their own way. There were a lot of trend setters, trend breakers; there were a lot of people who didn't care what other people thought.” (in Countryman, 2009, p. 104)

“'It is a lesson where everyone in the class can get involved, so when we come into the classroom we are all happy.” (in Kokotsaki, 2017, p. 11)

While some learners valued inclusive music learning contexts, others mentioned that they disliked “wasting” time. In such instances, one of the causes that was attributed to inefficient class time management was unequal levels of aptitudes within their group:

“Sometimes you'll be in a group lesson and then the people with you aren't as good as you are because they haven't been playing as long. And so, you have to go back to the beginning of it and go through it all again.” (in Lowe, 2012, p. 14)

Such comments were formulated by learners who perceived their own level in music as superior to those of some of their colleagues who, in their opinion, were slowing down the group. Another potential zone of conflict was related to keyboard use in class. Some learners described playing the piano as something positive that they would like to do more of during their classes: “We didn't have much time on the keyboards. Whenever we were on the keyboards, it was to prepare for a test” (in Kokotsaki, 2017). However, others included playing the piano among the elements that they disliked about their music lessons:

“It is nearly all the same; we have to listen and then play something on the piano.” (Kokotsaki, 2017, 2016, p. 29)

“We don't do composing a lot—all we do is play on the piano and sometimes we get in groups and do questions, it's boring.” (in Kokotsaki, 2017, p. 27)

The vast majority of the young music learners in the sources retained expressed that they like to learn music and to be actively engaged in their learning: they do want to play music, to create, to help each other, to realize projects, to be creative and to express themselves. However, what also stands out from the literature is that some current teaching approaches are not only unsupportive to help the learners to realize these powerful driving forces, but also seem to hinder them. For example, most music learners (a) don't like to be lectured and tested, they prefer to be active in a collaborative and non-stressful environment; (b) don't like to be directed in a top-down approach, they want to take part in the decision-making process, and (c) prefer not to specialize too quickly: they value learning various instruments and songs. A pedagogical approach based on these preferences would arguably promote learners' engagement as well as their development of 21st-Century skills. Hence, why are some music teachers still choosing to go against the grain and adopt a more formal approach (as shown in Lowe, 2012; Kokotsaki, 2017).

(We should) play the actual instrument rather than looking at a picture of an instrument.

(Participant in Kokotsaki, 2017, p. 29).

This literature review has shown that, despite the growing interest in the learner voice in education, research explicitly interested in the learner voice in the field of music is still limited. Given the relatively limited number of studies that have covered the subject so far, it is difficult to generalize any conclusions regarding the learner voice in music. Hence, we posit that more research is needed, with larger samplings, to provide a broader picture of the music learners' likes and dislikes in diverse contexts, both formal and informal. Documenting a greater number of music learner voices, more specifically exploring their zones of convergence or divergence and the factors underlying their views of music teaching and learning would represent a valuable contribution to the field. That being said, young people's voices are constantly evolving, and their perspectives, ideas and preferences will vary depending on the context in which they are collected. We therefore suggest that great care is taken in transposing the conclusions of one research study from one context to another, as such an approach might not always meet the needs and expectations of the participants.

Furthermore, we observed an important gap between the research methods implemented in the sources analyzed and the actual discourse on the learner voice. Effectively, while the research studies we reviewed were above all listening to the participants, most current learner voice theories agree on the idea that merely listening to the learners voice is not enough; authentic learner voice should promote empowerment and agencies of the participants (Rudd et al., 2006; Rudduck, 2007). This calls for a need to include the learners in sustainable ways throughout the process of decision-making, both in their educational settings and learner voice research.

Following what we have learned from the music learner voice, a few actions can already be implemented in music education. First of all, traditional one-to-one musical lessons centered on developing a specialization on a single instrument and sanctioned by a yearly exam seems to be alien to what most learners value. Effectively, while an inspiring teacher was valued by the learners, social connections with peers appeared to prevail for them. Secondly, we believe that it is crucial to be under the assumption that learners like to learn; music learners clearly expressed that they want to learn and that they do not like to “waste” time. However, they are also quite clear on how they prefer to learn. In a single word: experientially. They like to “learn by doing,” or more accurately, “learn by playing,” and not by “working.” They also like to be empowered and to make their own choice. Finally, learners like to teach. The learners expressed repeatedly that they value sharing what they have learned with their peers. Based on the important potential of learning-by-teaching as a means to consolidate learning (Duran, 2017; Koh et al., 2018), we believe that this approach should be more exploited in music teaching and learning.

If, as music teachers, our goal is to instill and nourish the love of music and music-making in our learners, top-down directive teaching approaches and formal testing might be counterproductive. If it hinders the engagement and motivation of the learner, what is the added value of a pedagogical approach tailored to meet the requirements of a final exam based on criterion that are disconnected to the learner's interests? Following our analysis, we propose a few innovative teaching and learning approaches in music education, where the learner voice is inclusively engaged in a dialogical decision-making process.

With these goals in mind, we suggest the following avenues for promoting a more significant inclusion of learner voice in music education and learner-centered approaches and practices:

• explore avenues to build and realize the full potential of social connections with peers

• ask learners what THEY would like to learn (instrument, repertoire, other musical and non-musical skills, such as recording or communication)

• ask learners HOW they think these learning goals should be approached

• include learners in designing lesson content, home practice goals, and long-term aims

• consult learners regularly about lesson content and method and ACT upon what they expressed, offering an authentic potential for changes and transformation

• include learners in discussing, implementing and evaluating these transformations

With these goals in mind, we suggest the following avenues for promoting a more significant inclusion of learner voice in music research:

• ask learners what THEY would like to investigate (research question and objectives)

• ask learners HOW they think these questions/objectives should be addressed (method)

• include learner in designing an experimentation (e.g., a specific program)

• consult learners more than once (e.g., at the beginning and at the end of a research project) and ACT upon what they expressed, offering an authentic potential for changes and transformation

• include learner in discussing, implementing and evaluating these transformations

In all the sources retained in this literature review, researchers listened to the learners' voice. We posit that this innovative approach conveys the potential to bring both significant and positive changes to music teaching and learning, as long as actions are taken following what leaners expressed. Effectively, coming back to our initial learner voice definition4, participants in these research studies were listened to and consulted. However, they were not included in the decision-making process and even less so invited to take action about their learning or their education. This is where the gap resides in current music research on the learner voice. Firstly, none of the research design included taking action in line with the ideas, perspectives or experiences expressed by the learners. Secondly, in all the literature reviewed, none included the learners in the research design, data collection, and analysis or dissemination of knowledge. That is to say that the learner voice was “listened to,” but that “the possibility for change and transformation” (Robinson and Taylor 4th core value) was more or less absent in those researches. This would represent an important step to take in the field of research on the learner voice in music. Similarly, extrapolating from the second limitation of this literature review, further research on the learner voice could place a special attention in providing access to all raw data (e.g., full verbatim and/or recording of the interviews). Such a practice would offer more visibility to the leaners voice and could potentially contribute to maximize its impact “on the ground.” In that direction, Kokotsaki (2017) stands out in our literature review for it provides, in the Appendix a multipage table featuring over 200 participants quotes associated with every “categories of description” she used for analyzing the interviews conducted. This is an interesting avenue for dissemination of knowledge if publishing whole raw data transcripts is not feasible. Using online resources for storing and sharing raw data would be another avenue to explore in learner voice research.

For example, in Black (2017) the participants described how participating in a jazz band combo influenced their musical and non-musical development, thus validating the positive impact of informal learning in a formal environment of jazz-learning experiences. While the learner voice was heard, it was when the researcher-teacher deemed it appropriate and about what he decided to discuss. Furthermore, apart from the research results, what the learners expressed did not result in changes and transformation of their music learning experience.

Hence, we argue that it is now time that music education take a step further and begin to listen also to the learners prospectively instead of just retrospectively. That is to say that listening to the learners' voice should occur BEFORE planning and implementing a data collection, WHILE the data collection is going on, and AFTER the data collection. Furthermore, it is equally important that actions be taken that are congruent with what learners have expressed. It may also be beneficial to include the learners in the research process and allow them to be agents of the transformation they promote.

The first limitation of this literature review is the small number of sources we analyzed. This testifies to the relatively scarce number of research studies explicitly focusing on “the learner/student/pupil voice” in music. This limitation, therefore, reveals a promising avenue for future research on this topic in music. The second limitation of this literature review is that we are using secondary sources to access the learner voice. As we are re-analyzing quotations from published papers, our results are undoubtfully tinted by the researchers' lenses. Effectively, the researcher made various decisions both during the data collection process and when choosing which quotes to include or not in their publications, based on their own perspectives and interests. Such decisions oriented the participant's discourse and the choice of the published quotations. This limitation brings to light an important question for further reflection in the field of learner voice research: how can we faithfully document and disseminate results in the learner voice?

Reading and analyzing this literature made us both sad and hopeful. It made us sad because we listened to so many frustrated voices who wanted to “play” and collaborate but were constrained by rigid structures and teaching approaches. It made us hopeful because whether in a creative classroom or not, music learners from all around the world expressed their desire to learn, teach, share, and create; all we have to do as music educators is to facilitate these noble inner drives.

J-PD did the literature review, wrote the first draft, and the final version of the manuscript. FD contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version. All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. ^For example, the 27th European Association for Music in Schools (EAS) and the 7th European ISME Regional Conference in Malmö (Sweden) organized their common conference on this theme (“The School I'd Like”) in May 2019.

2. ^For a more comprehensive discussion on the formal/informal framework in music education, the reader could refer to Folkestad (2006), Green (2002); Green, 2009, Jenkins (2011), Mak (2006), Schippers and Bartleet (2013) and Veblen (2018), among other.

3. ^This framework was developed for the Work on the waterfront intergenerational learning: Guidebook for educators. A cross-curricular arts and civic history program for elementary and secondary classrooms project. It was then reused by O'Neill and Dubé to analyse the data of their SSHRC funded project: Understanding young musicians' transformative music engagement: Integrating collaborative participatory learning into individual music learning contexts (https://www.music-engagement.com).

4. ^The process by which learners are listened to, consulted, included, take part, or take charge of the decision-making process or take action about their learning or their education in diverse contexts.

Biddulph, M. (2011). Articulating student voice and facilitating curriculum agency. Curr. J. 22, 381–399. doi: 10.1080/09585176.2011.601669

Black, P. (2017). On being and becoming a jazz musician: perceptions of young Scottish musicians. Lond. Rev. Educ. 15, 339–357. doi: 10.18546/LRE.15.3.02

Commeyras, M. (1995). What can we learn from students' questions? Theory Into Pract. 34, 101–106. doi: 10.1080/00405849509543666

Cook-Sather, A. (2002). Authorizing students' perspectives: toward trust, dialogue, and change in education. Educ. Res. 31, 3–14. doi: 10.3102/0013189X031004003

Cook-Sather, A. (2006). Sound, presence, and power: “Student voice” in educational research and reform. Curr. Inquiry 36, 359–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-873X.2006.00363.x

Cook-Sather, A. (2009). I am not afraid to listen”: prospective teachers learning from students. Theory Into Pract. 48, 176–183. doi: 10.1080/00405840902997261

Countryman, J. (2009). High school music programmes as potential sites for communities of practice–a Canadian study. Music Educ. Res. 11, 93–109. doi: 10.1080/14613800802699168

Duran, D. (2017). Learning-by-teaching. Evidence and implications as a pedagogical mechanism. Innov. Educ. Teaching Intern. 54, 476–484. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2016.1156011

Evans, S. E., Beauchamp, G., and John, V. (2015). Learners' experience and perceptions of informal learning in Key Stage 3 music: a collective case study, exploring the implementation of Musical Futures in three secondary schools in Wales. Music Educ. Res. 17, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/14613808.2014.950212

Fielding, M., and Bragg, S. (2003). Students as Researchers. Making a Difference. Cambridge: Pearson Publishing.

Folkestad, G. (2006). Formal and informal learning situations or practices vs formal and informal ways of learning. Br. J. Music Educ. 23, 135–145. doi: 10.1017/S0265051706006887

Gonzalez, T. E., Hernandez-Saca, D. I., and Artiles, A. J. (2017). In search of voice: theory and methods in K-12 student voice research in the US, 1990–2010. Educ. Rev. 69, 451–473. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2016.1231661

Green, L. (2002). How Popular Musicians Learn, A Way Ahead for Music Education. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

Green, L. (2008). Music, Informal Learning and the School : A New Classroom Pedagogy. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

Howell, G. (2011). Do they know they're composing?': music making and understanding among newly arrived immigrant and refugee children. Intern. J. Commun. Music 4, 47–58. doi: 10.1386/ijcm.4.1.47_1

Jenkins, P. (2011). Formal and informal music educational practices. Philos. Music Educ. Rev. 19, 179–197. doi: 10.2979/philmusieducrevi.19.2.179

Koh, A. W. L., Lee, S. C., and Lim, S. W. H. (2018). The learning benefits of teaching: a retrieval practice hypothesis. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 32, 401–410. doi: 10.1002/acp.3410

Kokotsaki, D. (2017). Pupil voice and attitudes to music during the transition to secondary school. Br. J. Music Educ. 34, 5–39. doi: 10.1017/S0265051716000279

Kuckartz, U. (2014). Qualitative Text Analysis: A Guide to Methods, Practice and Using Software. London: Sage Publications Ltd. doi: 10.4135/9781446288719

L'Écuyer, R. (1987). “L'analyse de contenu: notion et étapes,”. in Les Méthodes de la Recherche Qualitative, ed J. P. Deslauriers (Les Presses de l'Université du Québec), 49–65.

Lowe, G. (2012). Lessons for teachers: what lower secondary school students tell us about learning a musical instrument. Intern. J. Music Educ. 30, 227–243. doi: 10.1177/0255761411433717

Lowe, G. M. (2018). Competition versus cooperation: implications for music teachers following students feedback from participation in a large-scale cooperative music festival. Austr. J. Teacher Educ. 43, 78–94. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2018v43n5.6

Mak, P. (2006). Learning music in formal, non-formal and informal contexts. Available online at: https://research.hanze.nl/ws/files/12409231/mak14_1.pdf

Mitra, D. L. (2008). Balancing power in communities of practice: an examination of increasing student voice through school-based youth–adult partnerships. J. Educ. Change 9, 221–242. doi: 10.1007/s10833-007-9061-7

Mitra, D. L. (2014). Student Voice in School Reform: Building Youth-Adult Partnerships That Strengthen Schools and Empower Youth. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Mockler, N., and Groundwater-Smith, S. (2015). “Introduction: beyond legitimation and guardianship,” in Engaging With Student Voice in Research, Education and Community: Beyond Legitimation and Guardianship, eds N. Mockler and S. Groundwater-Smith (Springer International Publishing), 3–11. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-01985-7_1

O'Neill, S. A. (2016). Work on the Waterfront Intergenerational Learning: Guidebook for Educators. A Cross-Curricular Arts and Civic History Program for Elementary and Secondary Classrooms. MODAL Research Group.

Ozer, E. J. (2017). Youth-led participatory action research: overview and potential for enhancing adolescent development. Child Dev. Perspect. 11, 173–177. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12228

P21 (2019). Framework for 21st Century Learning. BattelleforKids. Available online at: https://www.battelleforkids.org/learning-hub/learning-hub-item/framework-for-21st-century-learning

Robinson, C., and Taylor, C. (2007). Theorizing student voice: values and perspectives. Improving Schools 10, 5–17. doi: 10.1177/1365480207073702

Rudduck, J. (2007). “Student voice, student engagement, and school reform,” in International Handbook of Student Experience in Elementary and Secondary School (Dordrecht: Springer), 587–610. doi: 10.1007/1-4020-3367-2_23

Schippers, H., and Bartleet, B.-L. (2013). The nine domains of community music: Exploring the crossroads of formal and informal music education. Int. J. Music Educ. 31, 454–471. doi: 10.1177/0255761413502441

Spruce, G. (2015). “Music education, social justice, and the “student voice,” in The Oxford Handbook of Social Justice in Music Education (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 287–301. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199356157.013.20

Veblen, K. K. (2018). “Adult music learning in formal, nonformal, and informal contexts,” in Special Needs, Community Music, and Adult Learning: An Oxford Handbook of Music Education, Vol. 4 (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 243–256.

Walker, L., and Logan, A. (2008). Learner Engagement: A Review of Learner Voice Initiatives Across the UK's Education Sectors. Futurelab. Available online at: https://www.nfer.ac.uk/publications/futl80/futl80.pdf

Whitty, G., and Wisby, E. (2007). Real Decision Making?: School Councils in Action (Research Report DCSF-RR001). Institute of Education, University of London. Available online at: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/6611/2/DCSF-RR001.pdf

Keywords: learner voice, student voice, music, teaching and learning, systematic literature review

Citation: Després J-P and Dubé F (2020) The Music Learner Voice: A Systematic Literature Review and Framework. Front. Educ. 5:119. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00119

Received: 26 November 2019; Accepted: 15 June 2020;

Published: 23 July 2020.

Edited by:

Dylan van der Schyff, University of Melbourne, AustraliaReviewed by:

Bryan Powell, Montclair State University, United StatesCopyright © 2020 Després and Dubé. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jean-Philippe Després, amVhbi1waGlsaXBwZS5kZXNwcmVzQG11cy51bGF2YWwuY2E=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.