95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 07 July 2020

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 5 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.00095

This article is part of the Research Topic School Achievement and Failure: Prevention and Intervention Strategies View all 14 articles

Over the last two decades there has been a growing interest in promoting a smooth transition to the first grade of primary school, given the potential long-term change this can have in preschool children at an academic and personal level. Research shows that psycho-educational interventions help improve children's academic and personal skills, lessening the effects of this challenging period. The effectiveness of transition-related interventions has been mainly focused on developed economies, such as Australia, the US, the UK, Italy, Hong Kong, etc. However, there is limited evidence regarding how this type of intervention could support stakeholders in developing economies, such as Latin America. The Latin American region displays some of the lowest rates of academic performance and highest rates of social inequality in the world, making this region a priority in the international research agenda. This study sought to explore the efficacy of an intervention programme to facilitate this transition in Mexico City. Findings provide evidence of the positive impact of the preschool transition-intervention programme on children's cognitive, social and fine motor skills, as well as in the frequency with which preschool teachers (PT) and the teaching assistants (TA) use transition practices that promote literacy in preparation for the first grade of primary school. Parents reported that the quality and closeness of the primary school were the main factors to consider when choosing the primary school that their child will attend. Parents reported that promoting academic skills in their child is essential to prepare them for this transition. Implications for policy and practice are discussed.

Research on the preschool transition to first grade has received a great deal of attention in the last two decades which has prompted international researchers to explore a number of variables involved in this challenging change in children starting primary school (Kagan and Tarrant, 2010; Haciibrahimoglu and Kargin, 2017). Going from preschool to first grade poses new challenges to children, which they have to face, including a new environment, relationships, teachers, and new rules—all of which have been found to have an important impact on their attitudes and roles (Fabian and Dunlop, 2005; Perry et al., 2014; Salmi and Kumpulainen, 2019; Urbina-Garcia, 2019). However, whilst there have been some efforts in exploring the effectiveness of transition-related interventions (mainly in developed economies such as Australia, the US, the UK, Italy, Hong Kong), it is still unknown how this type of intervention could support teachers, teaching assistants, children and parents in developing economies, such as Latin America, that have specific cultural and educational policy-related particularities. Moreover, the positive outcomes of intervention programmes have been widely documented (Schulting et al., 2005; Morrison et al., 2010; Ahtola et al., 2011), showing that interventions are positively associated with a better academic performance in first grade children. Nevertheless, such research is influenced by the socio-cultural context of developed economies, and thus, our understanding of the impact of these interventions in developing economies is limited. The international literature on interventions has provided a wealth of evidence for the positive impact on children, teachers and parents during this transition, which has ultimately helped children make the move successfully. For instance, Lee and Gogh (2012) undertook an action-research in Singapore with 14 children aged 5 and 6. Findings revealed a positive change in children's attitudes about first grade, as well as a decrease in parents' levels of anxiety triggered by this period of change. However, the limited number of children included in this study poses challenges in terms of data-generalization. Berlin et al. (2011) carried out a 4-week summer programme in the US to facilitate the transition to kindergarten based on a randomized control trial. Results revealed a better development of social skills for girls but, surprisingly, not for boys. Kindergarten teachers reported that this programme did not appear to have a significant impact on children's efficacy regarding academic demands. Nevertheless, authors reported a significant effect on the ability to adapt to the school routines of children participating in this programme. However, this study included only children at risk of academic failure, which does not allow for generalization of the data. Moreover, in the study by Berlin et al. (2011), the authors did not include a base-line assessment of the children's cognitive and social domains, which means the impact of such programmes in these areas cannot be identified.

In Hong Kong, Li et al. (2013) used a randomized control trial design including 143 families where a play-integrated preparatory programme was implemented. Results from the control and experimental groups indicated decreased levels of worry and increased levels of happiness, 6 weeks and 3 months after the intervention. Nevertheless, while the authors claimed that in order for children to have a smooth transition, children need to develop self-control skills so they can cope with stressful and anxious situations when transitioning, such skills were not assessed in the study. Furthermore, the authors claimed that the programme served this purpose, but no assessment of self-awareness, self-control or self-efficacy was carried out.

Hart (2012) implemented two different programmes to help children behaviorally at-risk in transitioning to kindergarten in US preschool centers and evaluated their efficacy. A focus (low intervention) and experimental group (high intervention) were created to implement a 4-week summer programme to support this transition. Results indicated fewer behavioral and academic problems for children in the high intervention programme than in the low intervention programme. The high intervention group showed better behavioral adaptation during the first year of kindergarten. Parents showed a major involvement in the high intervention group—arguably having a positive effect in helping children during this period. In line with this, the role of significant adults for children (i.e., parents, teachers and caregivers) has been highlighted in this transition. Giallo et al. (2010) reported that the implementation of transition programmes (i.e., aimed at providing transition practices, establishing home-school links and fostering children's development) resulted in a higher rate of parents' self-efficacy perception, which in turn, led to a greater involvement in their child's education. The authors also concluded that when parents are provided with information regarding this transition, they become more interested and tend to establish a more frequent and active home-school interaction. Parents' involvement in transition activities organized by schools has been associated with the acquisition of useful transition-related parental practices.

These intervention programmes included several activities worth noting. Lee and Gogh (2012) used an action-research design to promote cognitive and affective skills in children in Singapore. Activities included teaching children how to work with money, creating play opportunities to buy and sell using money and allowing children to buy their food in preparation to a visit to a primary school. The programme was assessed by using audio-recordings, observations and photographs of children engaged in the activities implemented. A US-based randomized test trial was used by Berlin et al. (2011) aimed at promoting children's social competence, pre-literacy and pre-numeracy skills, school routines, and parental involvement. The experimental group received the STARS programme while the control group did not receive the intervention, however, there is no description of the content of the STARS programme. Activities included weekly parent group meetings, a 4-days teacher training on family involvement and home visits. The programme was assessed by collecting data from parents, teachers and children with Likert type scales.

Another randomized control trial was conducted by Li et al. (2013) in Hong Kong aimed at promoting children's happiness and enhancing parents' psychological adjustment. The authors followed a 4-weeks play-integrated programme with an experimental and a control group. The intervention programme included activities to help the children become familiar with primary school life such as organizing their school bags and following school rules and regulations. Other activities focused on promoting children's problem-solving skills, emotional expression, interpersonal communication and coping with stress. Data from children and parents were collected with Likert type scales to assess the programme. In the US, Hart (2012) implemented a 4-weeks summer intervention programme with two different groups of at-risk pre-schoolers. Group 1 (high intervention) aimed at promoting children's behavioral, social-emotional, and academic functioning. This group received weekly parent transitional workshops (before, during and after the start of the kindergarten year) and monthly school consultations. Group 2 (low intervention) received parent transitional workshops only, without any intervention on children and no school consultations. Pedagogical activities for this study were adapted from various documents including the Florida State standards for maths, reading and science and the Florida Center for Reading Research. The programme was assessed in the fall and spring of the kindergarten year via teachers' and parents' self-report measures. Likert type scales were used to measure children's behavioral, social-emotional, and academic functioning.

A randomized control trial was conducted in Australia by Giallo et al. (2010), aimed at implementing an intervention programme to improve parent knowledge and confidence about the transition process, improve parent involvement in their child's education and improve child adjustment to starting school. The programme consisted of four sessions (1.5 to 2 h in duration each) to address practical and development issues relevant to children/parents (for a detailed description of the programme see Giallo et al., 2010). Classroom teachers received a 2 h professional training session prior to the intervention. The intervention programme was assessed by collecting data from teachers and parents with the use of Likert type scales. Taken together, these programmes show a variety of activities which have been implemented to support children and parents ahead of the transition to school. However and although few programmes have been implemented for several weeks (i.e., four), it is important to recognize that none of these programs have been designed to intervene for longer periods of time (i.e., more than 1 month) to maximize the impact of the intervention programme. Similarly, these programmes have emphasized the use of quantitative measures to assess parents whereby their lived experiences during the implementation of these programmes have not been recognized.

Some studies have suggested that parents can become aware of the importance of the transition process after participating in transition programmes (Schulting et al., 2005; Carida, 2011), which leads to a greater participation in school-related activities with their children. Interestingly, in some studies, parents have shown a greater interest in this process, and specifically with regard to their child's education (Dockett and Perry, 2007), whilst in others, this interest and awareness have been related to parents' quest for additional information about how best to support their child (Wildenger and McIntyre, 2011). Taken together, these findings provide compelling evidence about the effectiveness of interventions during this period of change, which provide and promote knowledge, awareness and practices for teachers and parents. These studies show how designing and implementing an intervention can lead to better support children, teachers and parents to successfully transit through this change and build a sense of community needed for this change. Notably, research shows that this change can be experienced in a smoother way if children, parents, teachers are included in intervention programmes. The constant exchange of information and constant interactions among adults in this process is a key element in this transition and is known as bridging (Malsch et al., 2011), which is one of the principles of the Ecological and Dynamic Model of Transitions proposed by Rimm-Kauffman et al. (2000) which is the model that underpins the present study. Following this theoretical model, the constant interaction and exchange of information among contexts was of utmost importance in this study to ensure developmentally and academically appropriate practices within the intervention to ease the transition.

Little is known about the way in which the context of developing economies shapes this transition to primary school, and how intervention programmes must be adapted to cultural practices, values, educational policies and curriculum. The novelty of this study is that this intervention considered various levels—namely: school, home, home-school, and school-school links (framed by the particularities of the culture of a developing economy including but not limited to high level of social inequality, low salaries for parents, limited resources for public schools, high levels of crime and violence in the city)—and included children, parents, and teachers, whilst previous research has focused only on teachers or parents separately in either preschool and/or primary school. Based on research conducted in developed economies, we know that children can greatly benefit from this type of intervention. Similarly, research on parents and teachers shows that adults can play a key role supporting pre-schoolers during this period of change. Research focused on interventions has provided a wealth of evidence regarding essential elements that need to be considered when designing and implementing an educational intervention. Worryingly, most of the research in this respect and its positive findings have been framed by the socio-cultural context of developed economies, whilst, to our knowledge, there is no research on preschool transition in developing economies, such as Latin America. This study aims to fill these gaps by designing and implementing an intervention programme to facilitate the transition to first grade with Latino families, with a view to exploring its efficacy within the Mexican cultural context. A number of transition activities reported in the international literature were carefully analyzed and adapted for the present study, considering the Mexican context.

This study followed a quasi-experimental design with a pre-test and post-test for preschool children and teachers. This study was carried out during one academic year in two preschool classrooms (one control and one experimental) from two different public schools -to avoid contaminating data- belonging to a government institution that provides social services to the children of government workers in Mexico City.

Each preschool classroom included 20 children (N = 40), with their respective classroom teacher and teaching assistant (N = 4). Children were in the final year of their preschool education ranging from 5 to 6 years old (M = 5.6). The two preschool teachers (PT) reported holding an undergraduate diploma in preschool education whilst both teaching assistants (TA) had vocational training. The researcher fully disclosed the main aims of the study to headteachers to obtain permission to recruit families of the preschool children involved. Forty families were contacted to explain the main aim of this study and accepted to participate in this project by signing a consent form. Most of parents were female (85%) reporting that their highest academic degree was undergraduate degree (80%) and vocational-training (20%). Parents' age ranged from 30 to 60 years old (M = 44.67).

We included two intact groups that had already been formed by the administrator of the schools at the beginning of the academic year, following the normal protocols of the Ministry of Education. Two public schools were recruited in order to have one control group in one school, and one experimental group in another. A Mann Whitney U test revealed no significant differences in either the scores of children's skills (i.e., cognitive, social, and fine motor) or teachers' early literacy practices at the beginning of the intervention.

Children's skills were assessed by using the Assessment and Evaluation Programming System for Infants and Children (AEPS; Bricker et al., 2002) which is a criterion-referenced test to measure children's skills in six different key developmental domains. However, only three main domains were included in this study due to their relevance in this transition process (Margetts and Kienig, 2013)—namely: cognitive, social, and fine motor skills. The AEPS instrument has reported to have sound psychometric properties, showing high internal consistency reflecting a strong relationship among domain scores and items, in addition to showing satisfactory inter-rater reliability (Noh, 2005). Additionally, the reliability and validity of the instrument have been furthered confirmed when used in other studies (Cadigan and Missall, 2007; Gao and Grisham-Brown, 2011; Lemire et al., 2014).

Children's skills were measured considering a 3-point scale: “0 = Does not show the skill”; “1 = Inconsistent use of the skill” and “2 = Consistent use of the skill.” Cognitive skills included “Identification of numbers/figures,” social skills included “Showing affect to others,” and fine motor skills included “Use of scissors by following geometrical shapes.”

PT and TA practices that promote literacy in preschool classrooms, which have been reported to aid in this transition (Berlin et al., 2011), were assessed with a self-report questionnaire adapted from the “Inventory of Early Literacy Practices” (Neuman et al., 2000) including 40 items. The adapted version of this questionnaire was assessed by one emeritus professor and two professors of educational psychology and their feedback was considered to produce a final version. Preschool teachers and TAs rated the extent to which they use these practices in their everyday routine to promote early literacy skills in pre-schoolers based on a 3-point rating scale: “0 = Does not use the practice”; “1 = Inconsistent use of the practice” and “2 = Consistent use of the practice.” Both instruments were piloted prior to the final administration by using a different group of participants.

Parents' views about the way in which they thought they could prepare their child for this transition were gathered with three open-ended questions developed by the author for the purpose of this study: (a) What factors will you consider for choosing the primary school to which your child will attend?; (b) In which way do you support your child in this transition?; and (c) What have you talked about with your child regarding the primary school? Parents' satisfaction with the intervention was rated with a single-item on a 5-point scale (1 = Very Dissatisfied to 5 = Very Satisfied). These questions were reviewed and assessed by the same external professors and feedback was considered.

Educational authorities granted permission and the researcher contacted headteachers and parents from both schools to fully explain the main aims of the study. Ethical approval was not required for the governmental institution providing the educational service. However, personal consent forms were obtained from parents and teachers/TAs. Children's consent was also obtained by the researcher. At the beginning of the academic year, a pre-test was carried out to assess children's skills and PT and TAs' practices, by using participant observation and direct testing (Taylor et al., 2015), the researcher assessed children's skills in both classrooms. Preschool teachers and TAs each completed a 40-item, self-report questionnaire, separately, in a room specifically designated by headteachers to avoid data-contamination. The post-test was carried out at the end of the academic year following the same procedure. At this point, parents' views and overall satisfaction with the programme were gathered. The intervention programme was implemented in the experimental group, whilst the control group received the usual pedagogical activities planned by the preschool teacher.

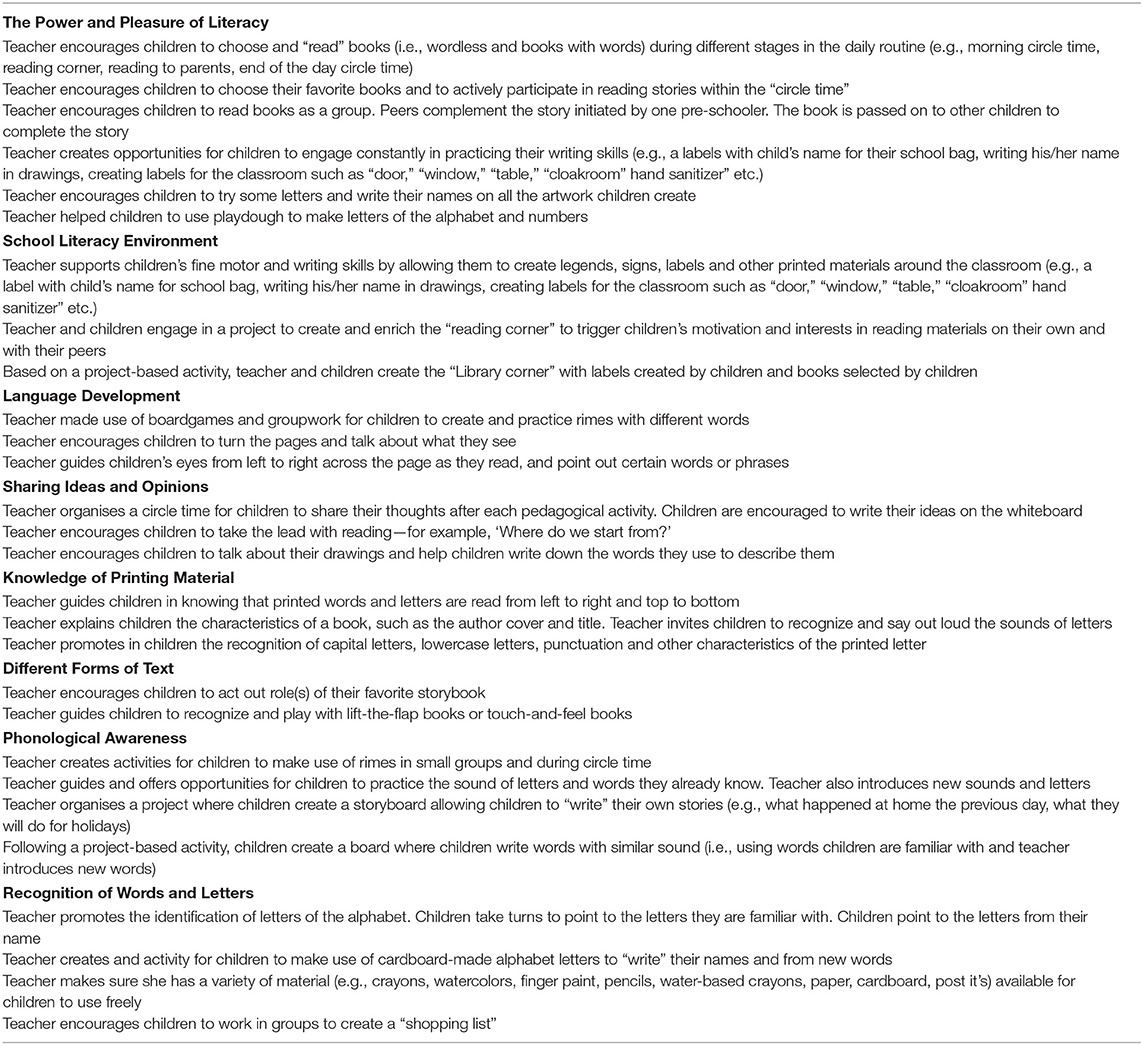

This evidence-informed transition programme included transition activities that have proven useful to enhance preschoolers' transition in previous studies (Claes, 2010; Peters, 2010; Hedegaard and Fleer, 2013), adapting them to the cultural particularities of the city and considering the internal educational policies of the preschool center. A group work was created for the researchers to work collaboratively (i.e., 3 days per week for 4 weeks) with PT and TAs, with the aim of choosing and defining the pedagogical activities (see Table 1) to be integrated in the program. The ample working experience of the PT and TAs and their knowledge of local policies, curriculum as well as pupils and parents, was paramount to define the activities to be implemented. Such experience and knowledge were further complemented by a synthesis of relevant literature and previous intervention programs provided by the researchers. The final version of the intervention programme was sent to a panel of three experts (i.e., professors of educational psychology and child development) in preschool and primary education. The final version of the program considered the feedback provided by the experts. The implementation of this programme was proactive and intensive, working alongside the PT and TAs in the classroom for 6 consecutive months with 3 sessions per week. All activities were mainly led by the PT and TAs, with minor interventions of the researcher. This intervention (see Appendix A) comprised of a range of activities to help: (a) develop cognitive skills through activities that promote early literacy; (b) promote children's social competence; (c) develop fine motor skills; (d) promote home-school links (e.g., involving families in this transition intervention); and e) promote school-school links (e.g., visits to the primary school). The intervention programme included:

Table 1. List of pedagogical activities implemented in classroom to aid the development of children's cognitive, social, and fine motor skills.

The researcher closely worked with the PT and TAs in a collaborative way, whereby emphasis was placed on planning the pedagogical activities (see Appendix A) that promote the cognitive, social and fine motor skills necessary for the transition (Brownell et al., 1997). The inclusion of these pedagogical activities was based on the preschool and first grade curriculum, as well as what the literature reported as effective transition activities.

The researcher contributed to PT and TAs knowledge of developmental aspects and children's skills during the activities that were included in the daily routine. PR and TAs did not receive any specific training per se considering a traditional approach. Rather than following a traditional teaching approach where the researchers are the “experts” and teachers are “passive learners,” we followed the principles of learning through modeling outlined by Loughran (2002) and principles of the scaffolding approach suggested by García and Ruiz-Higueras (2011). The researcher modeled the implementation of pedagogical activities—unknown to the teacher—that were included in the weekly-pedagogical plan of the PT. A 2 h group discussion including the researchers, PT and TAs was held weekly -at the end of each week for the duration of the intervention- to feed back on the advantages and difficulties encountered during the week. These discussions focused on helping PT and TAs reflect upon their own practice as well as discussing topics related to stages of child development, tailoring pedagogical activities and how different activities could be used to promote the development of children's cognitive, social and fine motor skills. These sessions helped improve the intervention for the following week. This approach was adopted given that it has been highlighted as essential in order to help teachers develop new skills and acquire new knowledge regarding child development (Loughran, 2002).

Working collaboratively, the researcher, the preschool teacher and TA re-designed the distribution of pedagogical material included in different areas in which the preschool classroom was divided as per curriculum guidelines. New pedagogical material was included in some areas, whilst there was also material that did not correspond to the aim of a given area, and thus was reallocated. Changes were carried out in areas such as the child's library, pretend play, free-play, science, Lego blocks and literacy. In all activities regarding the improvement of classroom-areas as well as the pedagogical activities proposed by the PT and the TA, children were actively involved. A traditional approach was always avoided (i.e., the teacher is the expert and leads all activities with minimal involvement of children). The inclusion of children as leaders in each activity and project (e.g., preparing lunch for school visits, Teddy's diary, labeling classroom furniture) was of utmost importance during this intervention. This aimed at promoting peer-to-peer and teacher-child interaction focused on supporting children develop their social skills.

The researcher, preschool teacher and TA designed a series of activities whereby parents attended the preschool classroom three times a week in order to interact with pre-schoolers. Activities included storytelling by parents and children, explaining to children different types of jobs parents have and talking about what parents' primary school was like.

An activities-book was developed by the researcher and the preschool teacher containing 20 different attractive activities focused on the development of early literacy skills appropriate for pre-schoolers. There were given to parents for them to complete during the Easter holidays, together with their child. Emphasis was placed on the need to carry out these activities alongside their child.

A project-based activity led by the PT and TAs resulted in the creation of a diary, which was taken home every day by a different child. The name “Teddy” was decided by preschoolers by participating in a poll. All the paraphernalia needed for this activity (i.e., tickets, names, posters, labels, and so forth) were created by preschoolers in an attempt to provide opportunities to practice and thus enhance their skills. In this diary, children recorded the activities he/she had done during his/her day after school. Parents were also asked to help their child “write” and produce drawings of the activities he/she had decided to include. Additionally, parents were also asked to help their child by writing the activities their child decided to tell his/her peers. The following day, there was a time allocated for reading the diary, which was facilitated by the main teacher, where preschoolers exchanged ideas regarding the activities shared by their peers.

Preschoolers, alongside the PT and TAs, visited the primary school at three different times throughout the intervention, ranging from a 1 to 2 h-visit, depending on the activities planned.

A) First visit. First grade teachers toured preschoolers around the premises of the primary school. Preschoolers were introduced to different first grade teachers by visiting their classrooms and meeting first grade students. Play-based activities were facilitated by one first grade teacher and carried out in the playground of the primary school.

B) Second visit. Preschoolers were taken on a tour around the premises of the primary school in addition to experiencing the “recess” with first graders. For this activity, the PT and the researcher planned and facilitated a project-based activity in the preschool classroom, prior to this visit, where the nutritionist was also involved to help preschoolers prepare their “lunch” for the visit.

C) Third visit. Preschoolers visited one first grade-classroom and carried out activities with the first grade teacher and first graders. First graders shared their chairs with preschoolers so they could be seated for the activities prepared by the teacher. The teacher facilitated an “ice-breaking” activity for preschoolers to feel welcomed, in addition to the central activity focused on the recognition of numbers, alphabet letters and the production of drawings. First graders also showed preschoolers the classroom materials, such as classroom rules, science experiments, books, maps, and so on. Preschoolers worked together with first graders who lent their coloring pencils, books, notebooks, and white sheets to preschoolers to carry out the activity. First graders gave preschoolers a “present” once the visit had finished, which had been prepared in advanced.

Three different first grade teachers visited the preschool classroom (i.e., experimental group) on three different occasions to share their experience with preschoolers transitioning to first grade. First grade teachers highlighted the main differences between the preschool and primary school. Preschoolers were encouraged to ask questions about the primary school, which were answered and clarified by first grade teachers. After every activity related to home-school and school-school bridging (Malsch et al., 2011), preschool teachers facilitated an activity whereby preschoolers were asked to draw what they “saw,” “heard,” and “lived” not only during the visits to the primary school, but also during the first grade teachers' visits. Preschoolers shared their drawings with their peers and their parents in an “open-door” activity organized by the preschool teacher.

Descriptive statistics were obtained from the children's and teachers' measures. A Wilcoxon signed rank two-tailed test was computed to determine differences between the paired ratings of children's and PT/TAs from pre/post-test. This non-parametric test was considered since it allows the identification of differences in a Likert-type scale measurement in pre-post designs, taking into account the magnitude and direction of differences (Haslam and McGarty, 2014). In order to obtain the magnitude and differences in scores obtained, all analyses were conducted at p < 0.05 significance level. A Mann-Whitney U-test was computed to compare the scores obtained in the pre-tests from the control and experimental groups for both, in order to establish a baseline before the intervention took place. A thematic analysis, as suggested by Braun and Clarke (2006), was carried out to analyze parents' answers.

Descriptive statistics were obtained to show the means and standard deviations of the control and experimental groups (Table 2), which revealed that pre-test means scores in both groups were similar prior to the intervention. Both groups of children's scores were assessed with a Mann-Whitney U-test (Table 3) in terms of equivalence before the intervention, since this test has been described as appropriate for use with small samples (Curtis and Marascuilo, 2004). The sum of the ranks for each group was calculated and then compared with that of the other group. A significant p-value (p < 0.05) indicates a significant difference between the two groups. Experimental and control groups did not differ in cognitive (M = 1.30, SD = 0.923; M = 1.05, SD = 0.999), social (M = 1.60, SD = 0.754; M = 1.45, SD = 0.826), and motor skills (M = 1.60, SD = 0.681; M = 1.55, SD = 0.759), respectively (p > 05). Therefore, both groups were similar in these skills before the intervention, suggesting that participants shared a similar development of cognitive, social and motor skills.

To analyze the effect of the intervention in the experimental group, a non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test (Coolican, 2009) was computed in both groups to explore statistical differences in scores (Table 4). The statistically significant difference was at the p < 0.05 level in all domains in the experimental group, as shown in Table 4. As can be observed, the experimental group increased cognitive (M = 1.75, SD = 0.444), W = 0.007, p < 0.05, social (M = 1.90, SD = 0.308), W = 0.034, p < 0.05, and motor skills (M = 1.85, SD = 0.366), W = 0.025, p < 0.05. However, the control group did not improve these skills on the cognitive (M = 1.20, SD = 0.951), W = 0.083, p = 0.05, social (M = 1.60, SD = 0.681), W = 0.083, p = 0.05, and motor measures (M = 1.55, SD = 0.759), W = 1.000, p = 0.05. As anticipated, statistically significant differences in the experimental group were found between the pre-test and post-test, suggesting that the intervention program did have an effect in the development of children's skills.

Preschool teachers and TAs were asked to rate the use of transition practices in preparation for the transition to first grade based on a 3-point Likert-type scale with 40-items. Descriptive statistics for teachers and TAs for both groups are shown in Table 5. Additionally, a non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test was computed in order to analyze the differences in the means scores after the period of intervention in both groups (Table 6). Results indicated statistically significant differences between the pre-test and post-test in the experimental group; Teacher (M = 1.73, SD = 0.506) W =0.000, p < 0.001; teaching assistant (M = 1.55, SD = 0.714) W = 0.000, p < 0.001, but no in the control group; teacher (M = 0.53, SD = 0.877) W = 1.000, p = 0.05; teaching assistant (M = 0.40, SD = 0.778) W = 0.157, p = 0.05, respectively. These results suggest that the preschool teacher and the teaching assistant of the experimental group reported a more frequent use of transition practices that promote literacy-related skills in children, compared to the control group.

Parents' perspectives were gathered by using three open-ended questions and analyzed following a thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006), which lead to the identification of key themes. Participants' answers were read thoroughly at least three times by the researcher to gain a full understanding of the way in which codes would emerge. Once codes and themes were identified, two external experts in preschool education independently reviewed the codes and themes generated by the main researcher to reach an agreement and thus enhance the trustworthiness of the results. A consensual agreement was reached for the final version of the five themes identified. Regarding the question related to the factors parents have considered in order to choose the primary school that their children will attend, two main themes emerged from participants' answers:

Parents mainly considered the quality of the primary school in terms of academic achievement. This is to say, they reported having asked schools directly and/or relied on what acquaintances told them regarding whether a primary school was good or bad, considering the academic level. Parents highlighted “…I mainly focus on whether the school has good reputation or not. If my neighbors say that they do not have smart students, then I will not choose it…” whilst others emphasized the information given by their family members “…my brother in law had his kids in that school and they obtained high grades. I will enroll my kid in that school because it has a good academic level.”

Parents emphasized that how close a school was to their workplace was an important factor to consider when choosing a primary school. Some parents mentioned: “I have found a primary school right on the back of the building where I work and that will be the school where my daughter will attend to because we can then get home together and quick.” Other parents pointed out that given that the city is very big, they cannot spend hours in a traffic jam to pick their children from primary school “I have heard about a good school close to my friend's house, however I am enrolling him in a school which is two blocks away from my workplace, otherwise it will take me 2 h to pick him up.” “This city is crazy and you cannot spend one and a half hours in the traffic jam. There is a school close to my house which is not a very good one, but what can I do?”

As for the second question regarding the way in which they support their child for this transition, one key theme emerged from parents' answers.

Parents reported that they were concerned about their children's lack of academic skills during the preschool-academic year, which will be essential once they enter primary school. As a result, one of the main ways in which they supported their children was by sending them to a “real school” because they teach children how to read and write. “I have enrolled my child in a good school where they focus on teaching children how to read and write.” Other parents also pointed out that they support their children by teaching them how to read and write, “…at home, I spend 2 h with my child teaching her the letters and numbers. We have even started to write words and his name.” Other parents thought that a good way to prepare their child was by sending him/her to language schools: “I am concerned about the primary school and therefore my child is learning English language in a private school so he can be prepared for the primary school.” Parents also thought that the current preschool center was not good enough and therefore, they send their child to private schools: “Well you know…in this school they [children] just play and do not learn anything. In April, my child will attend to a private school instead of this one so he can learn how to read and write.”

Finally, parents shared what they have been talking about with their child in order to prepare them for the primary school, focusing on two main themes:

Parents highlighted that the main issues they talked about when leaving preschool and entering primary school were the need to follow teachers' directions and obey the new rules: “I have told my boy that he will have to behave and do whatever his teacher will tell him. He cannot play anymore and must behave well.” Another parent mentioned: “…you know, my child likes playing and talking to her peers, however, she will not be able to do that anymore. She must focus on the academic tasks the teacher requires her to do. She must be very obedient.” Another parent highlighted the challenges that this change brings to her child: “My son is very mischievous and therefore he will struggle behaving in the new school. I am teaching him that he must follow the rules and obey his new teacher or he will have problems with me.”

Parents reported that they were aware of the differences between preschool and primary school and thus focused on the need for their child to complete everyday homework: “I have told my child that in the primary school she will have to finish every task required by her teacher. At home, she will not play until she finishes her homework.” Other parents highlighted that having “homework” from the primary school will also require them to spend additional time with their child: “In primary school my daughter will do lots of homework and I will have to spend more time helping her. I have told her that she must be fast to finish whatever she is asked to do.” Finally, parents also thought that learning a new language will help their child in this transition: “…his English language homework is making him aware of the importance of doing homework. I tell my son that he will have to do both homework(s) [English language and Primary school] if he wants to play Xbox.”

Twenty parents who participated in the preschool transition-intervention programme, completed the satisfaction survey at the end of the intervention. Mean scores were computed and revealed that, based on a 5-point scale, 95% (19) of parents felt very satisfied (M = 4.95 SD = 0.22) with the intervention programme.

Overall, findings provide evidence of the positive impact of the preschool transition-intervention programme on children's cognitive, social and fine motor skills, as well as in the frequency with which PTs and TAs use transition practices that promote literacy in preparation in the transition to first grade. Parents reported that the quality of the primary school and closeness of the school were the main factors to consider when choosing the primary school to which their child will attend. Parents reported that promoting academic skills in their child is essential to prepare them for this transition. Following rules and being obedient were the main topics on which parents focused when talking with their preschool child about the primary school, and they also reported being very satisfied with the implementation of the programme. This intervention was research-informed, being the first of its kind to be implemented in a Latin American context, since most of the preschool transition research has been carried out in developed economies such as Australia, Iceland, the UK, Italy, Greece and the US.

Results revealed that, after the intervention programme, there were statistically significant differences in children's skills in the experimental group, suggesting that children benefited from the various activities implemented throughout the intervention. However, caution must be taken when interpreting the results, since there could be a number of confounding variables influencing these results. Findings from this study confirm the usefulness of a range of activities which can be implemented in preschool classrooms to help pre-schoolers develop cognitive, social and fine-motor skills grounded in collaborative work between preschool teachers, teaching assistants and parents, which is indeed very much in line with some of the principles of the Ecological and Dynamic Model of Transition (Rimm-Kauffman et al., 2000). The results of this study seem to add evidence to the usefulness of one of the principles of the Ecological and Dynamic Model -that of promoting a constant interaction among contexts (i.e., preschool center, home, primary school). This could be observed when the activities implemented in our programme, promoted a constant interaction and exchange of information among the members of such contexts namely parents, teachers, children and headteachers. Such interaction seemed to have contributed to the development of a strong sense of community to support children during this change which has been observed in previous studies (Wildenger and McIntyre, 2011). Modeling key developmental aspects and transition practices (i.e., new knowledge for teachers), improving classroom-areas, implementing literacy-related activities and promoting visits to the primary school (considering the socio-cultural context and curriculum) seemed to be an effective strategy to support teachers and parents to acquire new knowledge and develop practices to support pre-schoolers during this transition. These results are consistent with previous studies (e.g., Berlin et al., 2011; Brotherson et al., 2015) which have shown significant effects of interventions in children's skills. Moreover, significant improvements in children's skills have also been observed in large-scale studies where a number of transition practices have also been implemented by teachers (Schulting et al., 2005). Whilst the lack of a randomized allocation of preschoolers in the experimental and control groups could represent a limitation in the present study, statistical analyses still revealed a positive impact in the development of children's skills. Nevertheless, other factors such as children's extra-curricular activities and the number of older siblings at home, were not controlled. Future studies should consider a randomized allocation of participants for both groups. Whilst results suggest that children in the experimental group developed more skills after the intervention, this study did not follow up on pre-schoolers during the first year of primary school, which could have allowed us to explore the long-term effects of this intervention. Future studies should focus on a more rigorous experimental and longitudinal design to be able to investigate the long-term impact of transition interventions. Furthermore, skills developed by children must be further analyzed to understand whether they contribute to a smooth transition to the first grade classroom.

This intervention helped preschool teachers and TAs significantly improve the use of transition practices. Whilst these transition practices were shown to be relevant for the support of the development of cognitive, social and fine motor skills in children, there is the need to focus on additional developmental domains (i.e., emotional). Although this intervention showed positive outcomes with teachers, other confounding variables (e.g., peer-to-peer support, exchange of ideas with other teachers) could have had an impact on teachers, which were not controlled and which need to be considered in future research.

Teachers seem to have promoted important parental involvement, which has also been observed in other studies as a result of interventions (Stormshak et al., 2002). Whilst family involvement was not measured in this study, it was clear that parents' engagement in classroom activities provided preschoolers with joyful experiences by seeing their parents coming to their classroom. Findings from family engagement activities in this study are similar to those found previous studies (Wildenger and McIntyre, 2011). This intervention helped the preschool teacher and TA carry out helpful activities (Stormshak et al., 2002; Dockett and Perry, 2007; Urbina-Garcia, 2019) to promote school-school links. However, future research is needed to explore the prevalence of such practices in teachers' repertoire. The constant teacher-parent interactions and visits to the primary school (i.e., “bridging”) led to a more frequent exchange of information among adults, which also allowed preschoolers to get to see—in a concrete way—what a primary school looked like.

Parents seemed to be aware of the differences between the preschool and primary school. However, they mainly focussed on their child's academic skills, leaving out other aspects (i.e., social, emotional). This is not surprising, since previous studies have shown that parents usually consider early literacy skills as essential to start first grade (Lee and Gogh, 2012), given that one of the key aspects of this transition is the change from a played-based to a more academic-led curriculum, which suggests a “curriculum discontinuity” (Turunen and Maatta, 2012; Alatalo et al., 2017). As a result, parents' main supporting strategies focused on helping their child learn how to read and write. Parents believed that enrolling their child in “actual schools,” where they will learn how to read, in addition to learning another language (i.e., English) was essential. Similarly, parents reported that the main issues they focussed on when talking to their child about their imminent entry to primary school were following new rules, carrying out classroom activities as required, doing homework and being obedient, which is consistent with previous findings (Chun, 2003; Fabian and Dunlop, 2007; Eskelä-Haapanen et al., 2017). Parents also reported how these “new challenges” would have an impact on their daily routine, since they would have to spend more hours with their child helping him/her with “homework,” which is consistent with other studies where a change in parents' routines has been importantly highlighted (Margetts and Kienig, 2013). Interestingly, parents' main criteria for choosing the primary school focused on the school's academic level and closeness to parents' workplace.

To summarize, this study has addressed an important gap in the literature whereby most of the preschool transition has been carried out in developed economies such as Australia, Iceland, the US and broadly in Europe, overlooking developing economies such as those found in Latin America. Worryingly, this region has shown some of the lowest academic performances based on international assessment exercises (OECD, 2018), and yet little is known as to the way in which the context, cultural practices, values, educational policies or curriculum, shape the preschool transition. This study represents one of the first attempts to explore a specific and adapted intervention programme to aid the preschool transition, including teachers, TAs, children and parents in a single intervention. This study adds to the international literature by providing empirical evidence regarding the implementation of a transition intervention programme in a developing economy, such as Mexico, contributing to what is already known from developed economies. Findings suggests that by implementing intervention programmes of this nature, significant improvement can be observed in preschoolers' skills, teachers' practices, and parents' involvement, which could facilitate preschoolers' transition to first grade. These findings must be replicated in order to broaden the extent to which these results can be generalized to other developing economies. We encourage the implementation of this type of intervention in similar contexts, with a view to gathering empirical evidence that could inform educational policies in near future.

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology. National Autonomous University of Mexico. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The budget for this study was administered by CONACYT- Mexico (National Council of Science and Technology). I would like to thank to all the participants for their valuable time invested in this study and to all Mexican citizens whose taxes, made possible this study.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ahtola, A., Silinskas, G., Poikonen, P.-L., Kontoniemi, M., Niemi, P., and Nurmi, J.-E. (2011). Transition to formal schooling: do transition practices matter for academic performance? Early Child. Res. Q. 26, 295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2010.12.002

Alatalo, T., Meier, J., and Frank, E. (2017). Information sharing on children's literacy learning in the transition from Swedish preschool to school. J. Res. Childh. Educ. 31, 240–254. doi: 10.1080/02568543.2016.1274926

Berlin, L. J., Dunning, R. D., and Dodge, K. A. (2011). Enhancing the transition to kindergarten: a randomized trial to test the efficacy of the “Stars” summer kindergarten orientation program. Early Child. Res. Q. 26, 247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2010.07.004

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bricker, Betty, and Pretti-Frontnczak, K. (2002). Assessment, Evaluation, and Programming System for Infants and Children (AEPS®), 2nd Edn. Administration Guide. (AEPS). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Brotherson, S. E., Hektner, J. M., Hill, B. D., and Saxena, D. (2015). “Targeting the transition to kindergarten: academic and social outcomes for children in the gearing up for kindergarten program,” in Conference Proceedings: of Learning Curves: Creating and Sustaining Gains from Early Childhood through Adulthood (Washington, DC: Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness).

Brownell, M. T., Yeager, E., Rennells, M. S., and Riley, T. (1997). Teachers working together: what teacher educators and researchers should know. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 20, 340–359. doi: 10.1177/088840649702000405

Cadigan, K., and Missall, K. N. (2007). Measuring expressive language growth in young children with autism spectrum disorders. Topics Early Child. Spec. Educ. 27, 110–118. doi: 10.1177/02711214070270020101

Carida, H. C. (2011). Planning and implementing an educational programme for the smooth transition from kindergarten to primary school: the Greek project in all-day kindergartens. Curric. J. 22, 77–92. doi: 10.1080/09585176.2011.550800

Chun, W. N. (2003). A study of children's difficulties in transition to school in Hong Kong. Early Child Dev. Care 173, 83–96. doi: 10.1080/0300443022000022440

Claes, B. (2010). Transition to kindergarten: the impact of preschool on kindergarten adjustment (Ph.D. dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest. Alfred University, Alfred, NY, United States.

Coolican, H. (2009). Research Methods and Statistics in Psychology, 5th Edn. London, UK: Hodder Education, An Hachette UK Company.

Curtis, D. A., and Marascuilo, L. A. (2004). Point estimates and confidence intervals for the parameters of the two-sample and matched pair combined test for ranks and normal scores. J. Exp. Educ. 60, 243–269. doi: 10.1080/00220973.1992.9943879

Dockett, S., and Perry, B. (2007). Transitions to School: Perceptions, Expectations, Experiences. Sydney: UNSW Press.

Eskelä-Haapanen, S., Lerkkanen, M. K., Rasku-Puttonen, H., and Poikkeus, A. M. (2017). Children's beliefs concerning school transition. Early Child Dev. Care 187, 1446–1459. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2016.1177041

Fabian, H., and Dunlop, A. W. (2007). “Outcomes of good practice in transition processes for children entering primary school,” Working Papers in Early Childhood Development, No. 42 (The Hague: Bernard van Leer Foundation).

Fabian, H., and Dunlop, W. (2005). “The importance of play in the transition to school,” in The Excellence of Play, 2nd Edn, ed J. R. Moyles (Berkshire: Open University Press/McGraw-Hill).

Gao, X., and Grisham-Brown, J. (2011). The use of authentic assessment to report accountability data on young children's language, literacy and pre-math competency. Int. Educ. Stud. 4, 41–53. doi: 10.5539/ies.v4n2p41

García, F. J., and Ruiz-Higueras, L., (eds.). (2011). “Modifying teachers' practices: the case of a European training course on modelling and applications,” in Trends in Teaching and Learning of Mathematical Modelling, eds F. Javier and L. Ruiz-Higueras (Dordrecht: Springer, 569–578.

Giallo, R., Treyvaud, K., Matthews, J., and Kienhuis, M. (2010). Making the transition to primary school: an evaluation for a transition program for parents. Austr. J. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 10, 1–17.

Haciibrahimoglu, B. Y., and Kargin, T. (2017). Determining the difficulties children with special needs experience during the transition to primary school. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 17, 1487–1524. doi: 10.12738/estp.2017.5.0135

Hart, K. C. (2012). Promoting successful transitions to kindergarten: an early intervention for behaviourally at risk children from head start presschools (Ph.D. dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest. State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, United States.

Haslam, S. A., and McGarty, C. (2014). Research Methods and Statistics in Psychology. London, UK: Sage.

Hedegaard, M., and Fleer, M. (2013). Play, Learning, and Children's Development: Everyday Life in Families and Transition to School. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Kagan, S. L., and Tarrant, K. (2010). Transitions for Young Children: Creating Connections across Early Childhood Systems. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing Co.

Lee, S., and Gogh, G. (2012). Action research to address the transition to kindergarten to primary school: children's authentic learning, construction play and pretend play. Early Child. Res. Pract. 14, 1–16.

Lemire, C., Dionne, C., and McKinnon, S. (2014). Validité de contenu du nouveau domaine de la littératie de l'AEPS®/EIS. Rev. Francoph. Défic. Intellect. 25, 116–130. doi: 10.7202/1028217ar

Li, H. C. W., Mak, Y. W., Chan, S. S., Chu, A. K., Lee, E. Y., and Lam, T. H. (2013). Effectiveness of a play-integrated primary one preparatory programme to enhance a smooth transition for children. J. Health Psychol. 18, 10–25. doi: 10.1177/1359105311434052

Loughran, J. J. (2002). Developing Reflective Practice: Learning About Teaching and Learning Through Modelling. Abingdon; Oxon New York, NY: Routledge.

Malsch, A. M., Green, B. L., and Kothari, B. H. (2011). Understanding parents' perspectives on the transition to kindergarten: what early childhood settings and schools can do for At-risk families. Best Pract. Mental Health 7, 47–66.

Margetts, K., and Kienig, A. (2013). International Perspectives on Transition to School: Reconceptualising Beliefs, Policy and Practice. Melbourne, VIC: Routledge.

Morrison, F. J., Ponitz, C. C., and McClelland, M. M. (2010). “Self-regulation and academic achievement in the transition to school,” in Child Development at the Intersection of Emotion and Cognition (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 203–224.

Neuman, S. B., Bredekamp, S., and Copple, C. (2000). Learning to Read and Write: Developmentally Appropriate Practice. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Noh, J. (2005). Examining the psychometric properties of the second edition of the assessment, evaluation, and programming system for three to six years: AEPS test, 2nd Edn. (Ph.D. thesis). University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, United States.

Perry, B., Dockett, S., and Petriwskyj, A. (2014). Transitions to School-International Research, Policy and Practice. New York, NY: Springer.

Peters, S. (2010). Literature Review: Transition from Early Childhood Education to School. Report to the Ministry of Education, New Zealand. Retrieved from: http://ece.manukau.ac.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/85841/956_ECELitReview.pdf

Rimm-Kauffman, S., Pianta, R., and Cox, M. (2000). Teachers' judgements problems in the transition to kindergarten. Early Child. Res. Q. 15, 147–166. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(00)00049-1

Salmi, S., and Kumpulainen, K. (2019). Children's experiencing of their transition from preschool to first grade: a visual narrative study. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 20, 58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2017.10.007

Schulting, A. B., Malone, P. S., and Dodge, K. A. (2005). The effect of school-based kindergarten transition policies and practices on child academic outcomes. Dev. Psychol. 41, 860–871. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.6.860

Stormshak, E. A., Kaminski, R. A., and Goodman, M. R. (2002). Enhancing the parenting skills of Head Start families during the transition to kindergarten. Prevent. Sci. 3, 223–234. doi: 10.1023/A:1019998601210

Taylor, S. J., Bogdan, R., and DeVault, M. (2015). Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: A Guidebook and Resource. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Turunen, A., and Maatta, K. (2012). What constitutes the pre-school curricula? Discourses of core curricula for pre-school education in Finland in 1972-2000. Eur. Early Childh. Educ. Res. J. 20, 205–2015. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2012.681135

Urbina-Garcia, A. (2019). Preschool transition in Mexico: exploring teachers' perceptions and practices. Teach. Teach. Educ. 85, 226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.06.012

Wildenger, L., and McIntyre, L. (2011). Family concerns and involvement during kindergarten transition. J. Child Fam. Stud. 20, 387–396. doi: 10.1007/s10826-010-9403-6

To plan, design and facilitate an intervention programme to promote children's cognitive, social and fine motor skills as well as teachers practices that promote children's early literacy skills with a view to facilitating children's transition to primary school

a) to promote children's cognitive, social and fine motor skills to facilitate children's transition to primary school

b) to promote school-school and home-school links to facilitate children's transition to primary school

This intervention followed a pre-post research design making use of a mixed-methods approach considering different activities

Collaborative work between PT, TAS and researchers leading to planning sessions for the intervention

Planning family involvement

Planning school visits

Planning pedagogical activities

Weekly monitoring meetings

in situ modeling by researchers

Promoting PT and TAS in situ reflections on practice

Weekly discussion meetings

Supporting the development of new material for students

The programme was evaluated following a pre-post research design. The effectiveness of the programme was assessed based on the outcomes in children's skills, teachers' practices and parent's perceptions after the intervention

Children's skills were evaluated with the AEPS (Bricker et al., 2002) to measure cognitive, social and fine motors skills

Teachers' practices that promote early literacy were evaluated by an adapted version of the “Inventory of Early Literacy Practices” (Neuman et al., 2000)

Parents' views were gathered with three open-ended questions.

Keywords: preschool transition, intervention programme, primary school transition, Mexican children, teachers' transition practices

Citation: Urbina-Garcia A (2020) An Intervention Programme to Facilitate the Preschool Transition in Mexico. Front. Educ. 5:95. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00095

Received: 10 February 2020; Accepted: 26 May 2020;

Published: 07 July 2020.

Edited by:

Edgar Galindo, University of Evora, PortugalReviewed by:

Óscar Conceição De Sousa, Universidade Lusófona, PortugalCopyright © 2020 Urbina-Garcia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Angel Urbina-Garcia, bS51cmJpbmEtZ2FyY2lhQGh1bGwuYWMudWs=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.