- Department of Art, Design & Visual Studies, Boise State University, Boise, ID, United States

This paper reports the outcome of a basic study in an Art 100: Introduction to Art class of 150 in which an Open Educational Resourced text was introduced. The study was the result of a survey done at the end of the semester with a review of the grades of one section using the OER text when compared to a comparable section using a commercial text. Each section was taught by the same instructor in the same semester. The study examines the cost to students, as well as student outcomes, use, and perception of the OER text among those completing the course. The OER text was compiled from two primary open resources, along with material written by the instructor to bring it into line with the publisher text used for comparison in the study. Chapters of the OER text were posted on the course LMS as pdfs, along with reading quizzes and assessments corresponding to those in the comparison course created and accessed on the publisher's online site. By comparing the outcomes from each class through the University's metrics-gathering system, and by collecting the perceptions of the course through an end-of-semester survey it was determined that there was a positive result in outcomes in the section using the OER text and that students believed their text to be the equal of a published text. Additionally, they reported actually accessing and reading the OER text chapters as opposed to not purchasing a required text for a class in the past. Initial results indicate that an OER text in a Foundations Introduction to Art garners positive results for students. Because the use of an Open text in the discipline of Art Appreciation or Art History is quite uncommon at present, we believe this study to be a valuable contribution to the data.

Introduction and Review of Literature

The increasingly high cost of textbooks has been well-documented in the literature (Koch, 2006; Hilton and Wiley, 2011; Ally and Samaka, 2013) and presents an additional challenge to most students, but especially to those from lower-income demographics. Boise State University is a public institution in the capital city of Idaho, a small Northwestern state with a largely rural population. It has ~200 programs of study including 11 doctoral programs. In 2017-18 there were 25,540 students with 27% from out-of-state and international. The ethnicity of students is varied and while it is 73% white, the second most populous group is Hispanic/Latino at 13%, with Asian, African American, American Indian/Alaskan Native, and other groups also represented.

During the Fall semester 2017, students in two sections of Art 100: Introduction to Art were given the same instruction, assessments, assignments, and lecture by the same instructor. The study involved 296 students in total, 149 using the publisher's text and 147 using an OER text prepared especially for the course from a number of open resources.

Students in one section were assigned the publisher text while students in the second section were assigned the OER text which was deployed as pdfs on their Blackboard LMS. Students were informed of the study and given the opportunity to change sections if they preferred to use the other text; however, no student changed section. The goal in this initial study was to establish whether there was a significant difference in the outcomes between the two sections, and whether students preferred/did not prefer the OER text to a regular published text.

Boise State University is beginning to encourage the introduction of OER texts into its classes across the curriculum. According to data compiled by the state for AY18-19, BSU had OER texts in use in 111 sections across 8 classes including the one from Art 100 (Lashley, personal communication, 2019). English was the discipline recording the most significant use of OER after the Art 100 sections.

There were not many complete open educational texts in the Visual Arts available to choose from when developing the text for use at BSU. This may be due to a concentration of initial resources in OER texts aimed largely at STEM classes. In an overview of research from 2016 none are from OER resourced classes in the Fine Arts (Hilton, 2016). Art 100 at BSU is an undergraduate survey that fulfills one of the University requirements for the Humanities. In a given semester over 600 students will take Art 100 in sections taught both face-to-face and online. In previous years all sections used McGraw-Hill, Living with Art, by Mark Getlein, 11th ed. both paper and ebook. The cost of this text new from the bookstore was $90–$120. The online ebook version from Amazon is $103. Students were sometimes able to buy it used from other students, but to purchase the Connect access necessary for assessments still added $90 to their cost for the class. With an average enrollment of 150 students per section, this means that the adoption of OER to replace the textbook and assessments would save each section of Art100 at least $13,500.

Boise State has a significant cohort of students that are variously first generation, children of migrant parents, military who are dependent on GI funding which is unreliable in its immediate availability each semester, students with young families or other financial hardships, or low-income students generally. These populations find it extremely difficult to manage both tuition, fees, and texts each semester. In a study covering cohorts from 2006 to 2017, Boise State's Office of Institutional Research compiled data on the academic success rate as measured by first-semester GPA, academic standing, retention, and graduation rates among first-generation or low-income students (Office of Institutional Research, 2018). It should be noted that in Fall 2017, a higher percentage of students identified as neither first- generation nor low-income, but among those who did—both URM and non-URM (Under Represented Minorities) in those categories the First to Second Year Retention rate was 73.3% for URM and 82.7% for non-URM, a deviation of more than 11%. Students who identified as both low-income and first-generation were the lowest percentile among the 5-year graduation cohort from 2009 and 2009 at 16.3% (Belcheir, 2015).

The increasingly high cost of textbooks has been well-documented in the literature (Koch, 2006; Hilton and Wiley, 2011; Ally and Samaka, 2013; Hilton et al., 2014). Senack and Donoghue (2016) at Student PIRGs estimated that an average college student must spend $1,200 a year for textbook. Additionally, the study describes the rise in textbook costs since 2006 as 73%, four times the rate of inflation1. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics puts it at an even more significant 88% (2016). However, other sources have noted the actual reduction in the amount of money students are spending on textbooks each semester (Kestenbaum, 2014; National Association of College Stores, 2017-2018)2. This may suggest the use of non-publisher sources, but more troubling is the possibility that students simply aren't purchasing the text they need for the course because they can't afford it.

BSU tuition and fees are ~$24,000 a year without the cost of textbooks. In this environment many students enrolled in Art 100 are unable to complete the course and drop out, or become behind in the work by the time their student or GI aid arrives and are at a disadvantage in the class. An open-resourced text which would be available to all students at no cost on day one of the semester through our LMS (Blackboard) was introduced to establish its efficacy in mediating that disadvantage.

When on OER text is introduced into a class the cost differential in student outcomes is mitigated. A range of studies done on perceptions and outcomes using OER primarily in the STEM or business fields was compiled by Hilton (2016)3.

This is an initial study generated to determine the effectiveness of an OER text as compared to the published text that had been in use in previous years. More broadly, the study was intended to establish whether student perception of an OER text was significantly different from their expectation of a traditional text and whether this might affect learning outcomes. We anticipated that the cost factor would significantly predispose students toward the OER text, and we expected the outcome in grades for a majority of students to be the equivalent of those for the published text. While this was a small study with a narrow focus, the results were significant enough to support the continued use of the OER text. A broader study looking at more targeted populations is planned for 2020-21.

Research and Methods

With cost being the primary driver of the determination to implement an open- sourced text in the Introduction to Art, the remainder of the COUP framework (Cost, Outcome, Use, Perception) was included in the study to determine not just the practicality of moving to OER, but the impact it would have on student outcomes (Bliss et al., 2013; Clinton, 2018). Use and perception is integral to those educational outcomes since students who do not access a text will not have the same expectation of success as those who do. Students who perceive their text to be lesser would be expected to interact with it less frequently or not at all.

The initial proposal was to determine, in such a preliminary study, whether an open educational resourced text would significantly alter the outcome for students when compared to the published text used in another section (Hilton, 2016; Lawrence and Lester, 2018). The work that has been done can be categorized into (a) frameworks for OER evaluation and (b) empirical research and evaluation of OER (Fischer et al., 2015). In order to facilitate this evaluation and establish an equivalence for that evaluation, it was necessary to bring the OER text into as close a correspondence with the published text as possible. Quality had to be consistent across the platforms as well. Content, design, and illustrative materials needed to be, if not consistent, then equivalent (Wiley and Gurrell, 2009). Much effort was made to bring the OER material into a form that would be as effective as the ebook of the publisher. The illustrations came from original OER resources as well as Creative Commons, Wikipedia, and images of artwork used with the permission of galleries or artists themselves. The integral nature of images to this discipline makes obtaining reuse permission a particularly time-consuming element in the preparation of a text.

The study was designed to be completely invisible regarding individual student's identities and outcomes. The proposal was vetted by Boise State University's IRB or Office of Compliance and Ethics. It was determined that no student could be compromised by the information gathered in the study and that there was transparency in what students were being asked to contribute and to their understanding and willingness to participate in the study.

The two OER resources which were used were Saylor Academy: ARTH101: Art Appreciation and Techniques, and Lumen Learning: Boundless Art History. Other resources such as Khan Academy SmartHistory videos, museum websites, gallery websites, and Youtube videos were also integrated. To bring the OER text at BSU in line with the McGraw-Hill text, both media and techniques as well as an art history survey needed to be incorporated. Saylor had material that was consistent with the published text's chapters on media and techniques, and Boundless had art historical survey material that was adapted to the second half of the course. Additional writing was necessary to bring the OER material in line with the published text, in addition to resourced images that were licensed for reuse or in the public domain.

As noted, a number of contemporary artists, galleries, and museums were generous with permissions as well.

The second research category identified by Fischer et al. (2015) was that of empirical research and evaluation. To this end a Qualtrics questionnaire was devised that was given to all students in the OER section at the end of the semester asking them to evaluate the text and both their expectation regarding an OER text and their experience of its use. The results of that questionnaire was collected, analyzed and quantified, and is presented below. The variables that might otherwise affect outcomes were limited since the demographics of the student subjects, the instructor, the assessments and assignments in both sections were either exactly or largely the same (Hilton and Laman, 2012) (n = 14), and 5.1% were Seniors (n = 7). Additionally, 40.4% (n = 55) of respondents indicated that they were first-generation students, and 5.9% (n = 8) indicated that they were currently serving in the military or were veterans.

An analysis of differential student outcomes was performed by pulling grade information from the school's Student Information System (PeopleSoft) into R for data analysis. Only grades were included, with no personally identifiable information. Grades of students who withdrew from the class were not included in the analysis.

Results

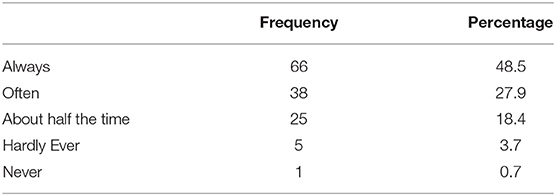

Textbook Purchasing

The survey first asked students several questions about their purchasing pattern involving textbooks in general. They were first asked about how often they purchased required texts for their courses. As shown in Table 1, most students indicated that they always or often purchased the textbook for their courses, with only a small percentage indicated that they hardly ever or never purchased the textbooks for their course. In another question, students were asked if they would “ever take a course but not buy the required textbook.” 50.7% (n = 69) of the students said Yes, 19.9% (n = 27) No, and 27.9% (n = 38) Maybe.

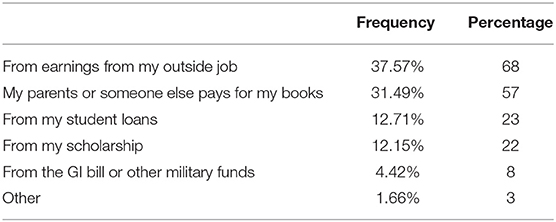

The next question asked students to select all of the ways that they paid for books required for their courses. Table 2 shows the results of this question. Students most frequently paid for textbooks from earning outside of their job, or from a parent or other party who paid for the textbook. Additionally, many students used money from their student loans or scholarships to pay for textbooks for their classes.

When asked about their perceptions of how much money they spend on textbooks each semester, most students responded that they responded a lot (52.9%, n = 72), with another 29.4% (n = 40) selecting that they spent a great deal. Only about 18% of students selected that they spent a moderate amount (10.4%, n = 14) or a little (7.4%, n = 10) on their textbooks for a given semester. They were also asked if paying $100 or more for a textbook would determine whether the student would take a course. 23.5% (n = 32) of the students said Yes, 18.4% (n = 25) of the students said No, and 58.1% (n = 79) of the students said If it isn't a course required for my major, maybe.

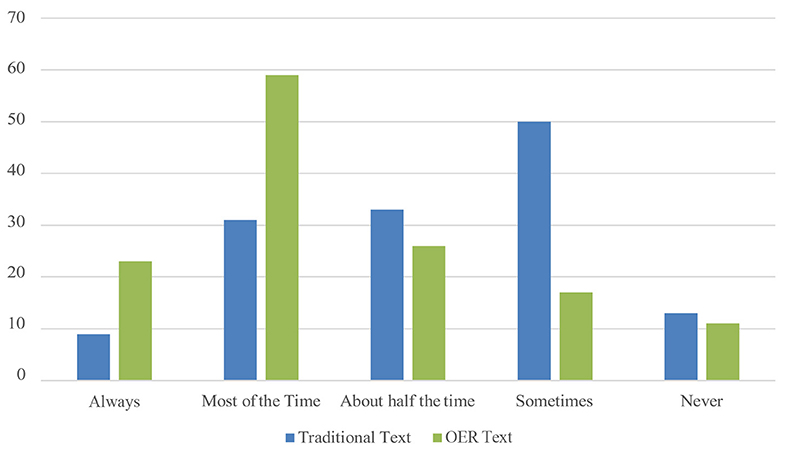

Students were next asked about their reading behavior regarding materials that were assigned to them in their typical courses, and how that compared with their behavior in the use of the OER text that was utilized for the Art History course.

Figure 1 displays a comparison between these two different settings. A Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks Test indicated that students read their OER text significantly more than traditional textbooks that they used for their courses (Z = −5.604, p < 0.001).

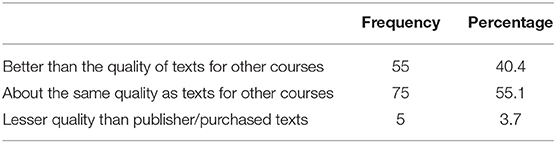

Quality

Students were next asked how the quality of the OER textbook of the course compared to the quality of a traditional textbook. The results are displayed in Table 3 below. Over 95% of the respondents felt that the quality of the OER textbook was the same, if not better than the quality of a traditional, publisher produced textbook.

Table 3. If you did do the OER reading for this course, how would you rate those readings compared to material from other texts from regular publishers that you have purchased?

Additionally, students were asked regarding their perceptions of the online format of the OER textbook that was utilized in the course, when compared to a traditional printed text. 64% (n = 87) indicated that they liked the online format of the OER textbook more, 14.7% (n = 20) indicated that they liked the online format less, and 14.7% (n = 20) had no preference. A group of 6 students (4.4%) indicted that they printed out the textbook and used it in a traditional manner.

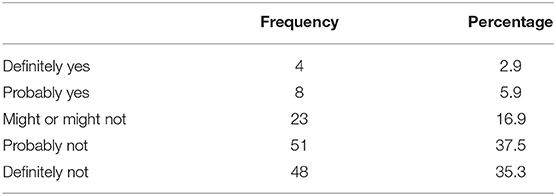

Additionally, students were asked if they felt that having a traditional textbook would have made the course more valuable to them. The results of this question are displayed in Table 4. Over 70% of the respondents indicated that a traditional textbook would not have made the class more valuable to them.

Table 4. Do you feel that having a traditional textbook would have made the class more valuable to you?

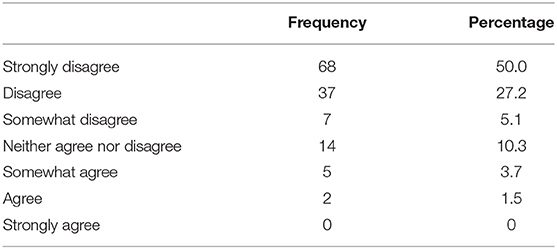

Respondents were next asked the extent to which they agreed with the statement “I would have preferred to purchase a traditional textbook for this course” (Table 5). Over 80% of the respondents disagreed to the statement, with 10% neither agreeing nor disagreeing, and 5% agreeing.

Table 5. Do you feel that having a traditional textbook would have made the class more valuable to you?

Grade Comparison

In addition to examining student responses to the survey, we also compared outcomes from the section of the Art 100 course that used the OER textbook with another section of the course, taught by the same instructor that used a traditional textbook (using McGraw Hill Connect). Grading in both sections was done with the same number, style, and content of assessments. This consisted of four multiple choice tests, two given as open book tests and two proctored in the Testing Center on campus. In addition, each section was assigned the same writing assessments which consisted of formal analysis of a given image—the same image in each section—and short reading quizzes which were designed to duplicate information available in either text model. The mean grade in the section that used a traditional section was 86.9%, which was slightly higher than the mean grade for the OER section (84.9%), however the results of a Welch Two Sample t-test indicate that the differences were not significant (t = 1.011, p = 0.3129). There is a significant body of research in other disciplines with similar outcomes regarding grades in OER classes when compared to those using traditional texts (Wiley et al., 2012; Bowen et al., 2013; Hilton, 2016).

Perception

The majority of students in the study—over 95%—indicated that the OER text was the equal of a traditional text; over 70% stated that having a traditional text would not have made the class more valuable to them, and 64% expressed that the delivery method online was preferable or made no difference to them. These results are in line with other studies that suggest OER resources to equally or more acceptable to students that published textbooks (California Open Educational Resources Council, 2016; Delimont et al., 2016; Ikahihifo et al., 2017; Colvard et al., 2018).

Discussion

Perhaps the most surprising outcome was that approximately 20% of students reported often or never purchasing a text for a course (similar in Jhangiani and Jhangiani, 2017). 83% reported spending a perceived “lot” or “great deal” on textbooks in a semester. When it is also taken into consideration that about 55% indicated that the money for textbooks came from an outside job, a student loan, or the GI Bill it was clear that other life choices were made over purchasing texts.

Given the choice, then, between an OER text of equal or superior efficacy and one costing $100+, most students preferred OER. This was not surprising. That they found the experience of using that text to be equal to that of other classes with purchased texts, and that their grade results were the equivalent and, in some cases, better than those of the group using the publisher's text, the case for continued use of the OER text in Art 100 classes at BSU is justified.

Conclusion

Results indicated that with the OER text student costs were obviously significantly lower, outcomes were basically the same against those of the published text, students' access to and interaction with the OER text was higher than that of the publisher's text, and most students had a favorable perception of their experience using the open-sourced text. The results underscore the potential advantage of open educational resources in the humanities as well as STEM subjects, and the easing of a significant financial burden on many students supports more research into and adoption of Open Educational Resourced materials.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Permission to conduct the questionnaire was granted by BSU IRB Office of Compliance. Written informed consent to participate in the questionnaire is inferred from questionnaire completion.

Author Contributions

The research and written text for this article was done exclusively by MJ. All computational work, data collation, and tables were created and managed by RN. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The study wishes to acknowledge the resources provided by the scholars at Saylor and Boundless. In addition, the Open Educational Resource team at BSU of Bob Casper, RN, Jonathan Lashley, Laurel Traynowicz, and the support of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation are noted with thanks and appreciation.

Footnotes

1. ^Retrieved from www.studentpirgs.org/textbooks (accessed March, 2019).

2. ^Retrieved from https://www.nacs.org/research/studentwatchfindings.aspx (accessed February, 2019).

3. ^retrieved from http://openedgroup.org/review (accessed November, 2018).

References

Ally, M., and Samaka, M. (2013). Open education resources and mobile technology to narrow the learning divide. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distribut. Learn. 14, 14–27. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v14i2.1530

Belcheir, M. (2015). Are Students Who Are Low-Income and/or First-Generation-in-College Less Likely to Experience Academic Success at Boise State? Office of Institutional Research; Boise State University.

Bliss, T., Robinson, T. J., Hilton, J., and Wiley, D. A. (2013). An OER COUP: college teacher and student perceptions of open educational resources. J. Interact. Media Educ. 5:4. doi: 10.5334/2013-04

Bowen, W. G., Chingos, M. M., Lack, K. A., and Nygren, T. I. (2013). Interactive learning online at public universities: evidence from a six-campus randomized trial. J. Policy Anal. Manage. 33, 94–111. doi: 10.1002/pam.21728

California Open Educational Resources Council (2016). OER Adoption Study: Using Open Educational Resources in the College Classroom. Permalink: http://tinyurl.com/WPOERAdoption040116, Printable PDF version with Appendices: http://tinyurl.com/WPOERPrintVersion2, Video Synopsis: https://youtu.be/vwVIrv0iSgE (accessed on April 1, 2016)

Clinton, V. (2018). Savings without sacrifice: a case report on open-source textbook adoption. Open Learn. J. Open Dist. eLearn. 33, 177–189. doi: 10.1080/02680513.2018.1486184

Colvard, N. B., Watson, C. E., and Park, H. (2018). The impact of open educational resources on various student success metrics. J. Teach. Learn. Higher Educ. 30, 262–276. Availabe online at: http://www.isetl.org/ijtlhe/

Delimont, N., Turtle, E., Bennett, A., Adhikari, K., and Lindshield, B. (2016). University students and faculty have positive perceptions of open/ alternative resources and their utilization in a textbook replacement initiative. Res. Learn. Technol. 24, 1–13. doi: 10.3402/rlt.v24.29920

Fischer, L., Hilton, J., Robinson, T. J., and Wiley, D. A. (2015). A multi-institutional study of the impact of open textbook adoption on the learning outcomes of post- secondary students. J. Comput. Higher Educ. 27, 159–172. doi: 10.1007/s12528-015-9101-x

Hilton, J. (2016). Open educational resources and college textbook choices: a review of research on efficacy and perceptions. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 64, 573–590. doi: 10.1007/s11423-016-9434-9

Hilton, J., and Laman, C. (2012). One college's use of an open psychology textbook. Open Learn. J. Open Dist. eLearn. 27, 265–272. doi: 10.1080/02680513.2012.716657

Hilton, J., Robinson, T., Wiley, D. A., and Ackerman, J. (2014). Cost-savings achieved in two semesters through the adoption of open educational resources. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distribut. Learn. 15, 67–84. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v15i2.1700

Hilton, J., and Wiley, D. A. (2011). Open-access textbooks and financial sustainability: a case study on flat world knowledge. Int. Rev. Res. Open Dist. Learn. 12, 18–26. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v12i5.960

Ikahihifo, T., Spring, K. J., Rosecrans, J., and Watson, J. (2017). Assessing the savings from open educational resources on student academic goals. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distribut. Learn. 18, 127–140. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v18i7.2754

Jhangiani, R., and Jhangiani, S. (2017). Investigating the perceptions, use, and impact of open textbooks: a survey of post-secondary students in British Columbia. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distribut. Learn. 18, 172–192. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v18i4.3012

Kestenbaum, D. (2014). How college students battled textbook publishers to a draw, in 3 graphs. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2014/10/09/354647112/how-college-students-battled-textbook-publishers-to-a-draw-in-3-graphs; (accessed April 2019).

Koch, T. (2006). Establishing rigour in qualitative research: the decision trail. J. Adv. Nurs. 53, 91–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03681.x

Lawrence, C. N., and Lester, J. A. (2018). Evaluating the effectiveness of adopting open educational resources in an introductory American government course. J. Political Sci. Educ. 14, 555–566. doi: 10.1080/15512169.2017.1422739

National Association of College Stores (2017-2018). Highlights From Student Watch Attitudes and Behaviors toward Course Materials 2017-18 Report. Retrieved from https://www.nacs.org/research/studentwatchfindings.aspx (accessed April, 2019).

Office of Institutional Research Boise State University. (2018). University Retention and Graduation Rates by Demographic Category: first-time, Full-time Freshmen Cohorts. Available online at: https://ir.boisestate.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/RR-2015-02-low-~income-and-first-generation.pdf

Senack, E., and Donoghue, R. (2016). Covering the Costs: Why We Can No Longer Afford to Ignore High Textbook Prices. The Student PIRGs. Retrieved from http://www.studentpirgs.org/textbooks (accessed March, 2019).

Wiley, D. A., and Gurrell, S. (2009). A decade of development. Open Learn. J. Open Dist. e-Learn. 24, 11–21. doi: 10.1080/02680510802627746

Keywords: open educational resources, open textbooks, online learning, introduction to art, art history, arts, ebook, open resource

Citation: Jones M and Nyland R (2020) A Case Study in Outcomes on Open-Source Textbook Adoption in an Introduction to Art Class. Front. Educ. 5:92. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00092

Received: 20 March 2020; Accepted: 25 May 2020;

Published: 02 July 2020.

Edited by:

Carrie Cuttler, Washington State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Katy Jordan, University of Cambridge, United KingdomSally Hamouda, Cairo University, Egypt

Copyright © 2020 Jones and Nyland. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Muffet Jones, muffetjones@boisestate.edu

Muffet Jones

Muffet Jones