- 1Carnegie School of Education, Leeds Beckett University, Leeds, United Kingdom

- 2School of Education and Social Work, University of Dundee, Dundee, United Kingdom

This study explores the lived experiences of students who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, or queer (LGBTQ+) during their transitions into, and through, higher education. Existing literature presents tragic narratives of students with LGBTQ+ identities which position them as victims. This study conceptualizes transitions as complex, multiple, and multi-dimensional rather than linear. The objectives of the study were to explore: the lived experiences of students who identify as LGBTQ+ in higher education; the role that sexuality and/or gender identity play in their lives over the course of their studies and LGBTQ+ students' experiences of transitions into, and through, higher education. The study is longitudinal in design and draws on the experiences of five participants over the duration of a 3-years undergraduate course in a university in the UK. Methods used include semi-structured interviews, audio diaries and visual methods to explore participants' experiences of transitions. Data were coded and analyzed thematically. This study uniquely found that the participants experienced Multiple and Multi-dimensional Transitions during their time at university and that these transitions were largely positive in contrast to the mainly tragic narratives that are dominant within the previous literature. In addition, this is the first study to have explored the experiences of LGBTQ+ students using a longitudinal study design. As far as we are aware, no existing studies apply Multiple and Multi-dimensional Transitions Theory (MMT) to students in higher education who identify as LGBTQ+.

Introduction

Large-scale studies have demonstrated that there is an increasing prevalence of student mental ill health in higher education. In 2016, 49,265 undergraduate students in the UK disclosed a mental health condition compared with 8415 in 2008 [(Universities UK (UUK), 2016)]. In addition, large survey data from Vitae (2018) found that between 2011 and 2015 there was a 50% increase in students accessing well-being services in universities. However, claims about increasing student mental ill health should be treated cautiously as more students might be willing to disclose poor mental health as a result of attempts to destigmatise it in recent years by the UK government and universities [(Department for Education (DfE) Department of Health (DoH), 2017)].

Nevertheless, students who identify as LGBTQ+ have been found to experience an increased risk of developing depression and anxiety (Neves and Hillman, 2017). Going to university can be both exciting and stressful. Students are expected to navigate Multiple and Multi-dimensional Transitions across different domains (Jindal-Snape, 2016). These are multifaceted and unfold as students interact with academic, social and institutional contexts (Cole, 2017). Students who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans are at risk of experiencing multiple stressors which can result in negative mental health outcomes (Meyer, 2003; Hatchel et al., 2019).

The academic research on the experiences of LGBTQ+ students in higher education presents a bleak picture. Much of the literature positions LGBTQ+ students as victims, highlighting students' experiences of bullying, harassment and discrimination (for example, Ellis, 2009). Despite this dominant negative portrayal of LGBTQ+ students' experiences, more recent literature has emphasized university as a positive experience which provides students with an opportunity to explore their gender and sexual identities (Formby, 2015). Grimwood (2017) found that university students were more likely to speak up against homophobic, biphobic, and transphobic discrimination in universities than staff, which might indicate that they feel empowered to challenge injustices. To the best of our knowledge, there are no published studies that have explored the experiences of LGBTQ+ students in higher education using a longitudinal study design.

Although existing literature has focused on the experiences of LGBTQ+ students in higher education (Ellis, 2009; Taulke-Johnson, 2010; Tetreault et al., 2013; Formby, 2015), published studies have not explored how students navigate transitions both over time and within the same timeframe across different contexts using a longitudinal study design.

Choice of University

Research indicates that for students who identify as LGBTQ+, perceptions of safety, acceptance and tolerance (Formby, 2014) are important factors which influence university choice-making. Thus, they may choose specific localities which they perceive to be queer-friendly and accepting and they may avoid places which are perceived to be repressive or intolerant (Taulke-Johnson, 2008, 2010; Formby, 2015). These “push and pull” (Formby, 2015, p. 21) factors also reflect broader LGBTQ+ migration patterns (Cant, 1997; Valentine et al., 2003; Howes, 2011; Formby, 2012). For example, research from the UK (Formby, 2015) and the US (Stroup et al., 2014) suggests that discrimination based on sexual orientation is more widespread on rural campuses.

For many students, the prospect of disconnecting from families, friends and home communities to attend university can be daunting (Chow and Healey, 2008). However, research has found that students who identify as LGBTQ+ may desire to escape from heterosexist and homophobic home communities which have “strictly regulated boundaries of acceptable (i.e., heterosexual) behavior” (Taulke-Johnson, 2010, p. 256). Heterosexist communities strongly promote and regulate heterosexuality as a way of life. Strong heterosexist and transphobic discourses within these communities can result in homophobia and transphobia. These serve to both regulate the dominant discourses and to punish those who transgress from them. These environments were “stifling” and “claustrophobic” and “restricted their expression and living out of their gayness due to them continuously being on stage” (Taulke-Johnson, 2010, p. 260) and students are lured by environments which were perceived to be more liberal, open-minded and which offered freedom of expression (Brown, 2000; Binnie, 2004; Weeks, 2007) and in which individuals could be safely “out” (Epstein et al., 2003). They may perceive university environments to be queer-friendly due to perceptions of the level of education and maturity of other students (Taulke-Johnson, 2010). In their desire to escape from “the hetero-saturated nature of their home towns” and “small town heterosexism” (Taulke-Johnson, 2010, p. 258) which forces them to maintain their invisibility, LGBTQ+ students may choose to embrace queer environments where they can construct families of choice (Weeks et al., 2001) and queer social networks which offer an alternative to the heterosexist and often close-knit communities that they have been brought up in.

Student Accommodation

However, Taulke-Johnson (2010) found evidence that university accommodation can be intolerant, unwelcoming, hostile and homophobic. He found evidence of anti-gay sentiments being written on doors of rooms resulting in gay students modifying their behavior so that their “gayness” did not have a visible presence in the accommodation. The homophobic bullying resulted in feelings of isolation and psychological distress as well as feeling obliged to educate housemates in order to change their negative attitudes (Lough Dennell and Logan, 2012; Formby, 2015; Keenan, 2015). Additionally, Valentine et al. (2009) found evidence of inappropriate responses by institutions to homophobic behavior in student accommodation such as institutions moving the victims out of the accommodation rather than the perpetrators. Although some students would have preferred “gay-friendly” housing, others did not want to be segregated into “gay only” accommodation and they wanted their institutions to create safe, inclusive accommodation for all students (Valentine et al., 2009). According to Foucault (1977, p. 172), separate spaces “render visible those who are inside…provide a hold on their conduct…carry the effects of power right to them.” Separate housing is not an adequate solution because it creates an ‘othering' effect which leads to further marginalization and discrimination. It can make the process of ‘othering' visible and results in the creation of colonies of exclusion within mainstream environments (Valentine et al., 2009).

Further, literature from the UK and the US has specifically noted concerns about accommodation for students who identify as trans or as gender non-conforming. These were due to lack of gender-neutral bathrooms and shared bedrooms for these students (Beemyn, 2005; Pomerantz, 2010; Krum et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2013), and due to the negative attitudes and misunderstandings of housemates (Formby, 2015).

Curriculum

Addressing the issues through the curriculum helps to foster inclusive attitudes in all students, regardless of the subject one chooses to study. Keenan (2014) has emphasized the invisibility of LGBTQ+ issues in the higher education curriculum, supporting earlier research by Ellis (2009). This can result in marginalization and curriculum invisibility is worse for trans students who have reported a lack of trans experiences and trans history reflected in their curriculum (McKinney, 2005; Metro, 2014; NUS, 2014). Attempts to queer the higher education curriculum have not been universal and literature suggests that courses continue to be strongly heteronormative (Formby, 2015). Although some universities celebrate annual events such as Pride and include a commitment to LGBTQ+ equality in their policies, there is evidence in the literature that the higher education curriculum does not seriously address issues around LGBTQ+ equality. Students continue to be presented with the achievements of the “same old straight, white men” and the curriculum is “pale, male and stale” (student participants in Formby, 2015, p. 32). For example, there is evidence which suggests that LGBTQ+ issues are invisible in health-related courses (Formby, 2015), thus presenting students with only a partial perspective on their disciplines. This is surprising given the association between mental health and LGBTQ+ (Bradlow et al., 2017).

Campus Climate

Although one-off celebration and recognition events go some way toward addressing LGBTQ+ diversity and equality, and create a positive campus climate, all students need to understand their responsibilities in promoting inclusion, diversity and equality and LGBTQ+ inclusion is part of this broader agenda.

In the US homophobia on campus is endemic and there is evidence of physical violence and verbal harassment (Ellis, 2009). This has resulted in a “climate of fear” (Ellis, 2009, p. 727) in which students do not feel comfortable disclosing their sexual identity. Additionally, there is evidence of students negotiating their homosexuality by avoiding known lesbian and gay locations, disassociating from known LGBTQ+ people and “passing” off as straight (Ellis, 2009). Research by Rankin et al. (2010) found evidence of name calling, homophobic graffiti and physical abuse, all of which contributed to the creation of a hostile climate for LGBTQ+ students. Students who identified as trans reported higher rates of harassment and LGBTQ+ students of color tended to report race as a reason for experiencing harassment rather than their sexual and gender identity. Research in the UK also presents evidence of homophobia on university campuses (McDermott et al., 2008; Valentine et al., 2009; Keenan, 2014) and a negative campus climate has been related to students considering leaving their course (Tetreault et al., 2013).

Plummer (1995, p. 82) has described the “coming out” process as “the most momentous act in the life of any lesbian or gay person” which does not just occur once and has to be repeated when LGBTQ+ people meet new people in different contexts. This can result in anxiety due to a lack of certainty about others' response. It is difficult to “come out” to their peers at university, especially when they share social spaces with male peers who display anti-gay attitudes and if there is a strong heterosexist discourse in the social and academic spaces of the university. Intolerant, disapproving and hostile environments can force male students to negotiate their homosexual identities by adhering to upheld protocols of traditional masculine behavior (Taulke-Johnson, 2008). This is a form of concealment which Meyer (2003) identified as an effect of proximal stress. They may even frame comments and anti-gay behavior as banter to form friendships with heterosexual peers. However, this “banter” reinforces anti-queer discourses and compulsory heterosexuality (Keenan, 2015), and places pressure on individuals to keep their sexual and gender identities in check.

Aldridge and Somerville (2014) found that nearly a quarter of LGBTQ+ students thought that they would face discrimination from other students. This is an example of proximal stress (Meyer, 2003). Research has also found that fears relating to prejudice and discrimination impacted negatively on levels of “outness” in universities (Formby, 2012, 2013, 2015). This suggests that even where bullying, prejudice and discrimination are not experienced directly, fears around these can impact negatively on LGBTQ+ students' experiences of higher education and thus, campus climate can be influenced by overt or covert factors.

Research by Ellis (2009) reported the existence of homophobia on university campuses in the UK and this also replicates earlier findings in the US (Rankin, 2005). Ellis concluded that “[Lesbian, gay and bisexual] students do not particularly perceive a “climate of fear,” but [still] actively behave in ways that respond to such a climate” (Ellis, 2009, p. 733). Ellis found that students deliberately concealed their sexual orientation because they did not feel comfortable disclosing it. Valentine et al. (2009) found that trans students reported a higher proportion of negative treatment, including threat of physical violence, compared to those who identified as LGB and these findings have also been replicated in the US (Garvey and Rankin, 2015). The masculine culture which exists on some university campuses (NUS, 2012) may also make some LGBTQ+ students feel uncomfortable and cause them to conceal their identities (NUS, 2012).

Keenan (2014) found that despite institutional commitments to equality and diversity, the lived experiences of LGBTQ+ students suggests that these policies are often not borne out in practice. It is evident that abuse is still apparent on university campuses, although in the UK verbal abuse is more common than physical abuse (Keenan, 2014). Additionally, other research has found that homophobic language is sometimes explained away merely as “banter” but nevertheless this still pathologises students who identify as LGBTQ+.

Positive Transitions

Gay male students have been portrayed in the academic literature as victims (Taulke-Johnson, 2008) and accounts have documented the impact of homophobia, intolerance and harassment on their psychological well-being, academic achievement and physical health (Brown et al., 2004; Tucker and Potocky-Tripodi, 2006). These accounts situate queer students within a “Martyr-Target-Victim” model (Rofes, 2004, p. 41) and positive accounts are largely unreported and ignored (Taulke-Johnson, 2008). Accounts which portray the “tragic queer” (Rasmussen and Crowley, 2004, p. 428) with a “wounded identity” (Haver, 1997, p. 278) are only partial and they locate queer students within a pathologised framework. These accounts are largely unquestioned and remain unproblematised and label queer students as victims.

Therefore, although experiences of homophobia, harassment and discrimination are unfortunately a reality for some students, it is important to offer a more balanced perspective which reflects the lived experiences of the queer student population. An alternative narrative which presents non-victimized accounts of their experience offers a more nuanced, inclusive and comprehensive insight into queer students' experiences of higher education (Taulke-Johnson, 2008).

During their time at university queer students can experience fulfilling, enjoyable and empowering experiences. These might potentially include falling in love, developing sexual relationships, establishing new social networks and friendships, and having fun. For some LGBTQ+ students, university is a time when they can explore and develop their self-identities in safe, accepting environments (Taulke-Johnson, 2008). Taulke-Johnson's participants emphasized how they had been able to construct positive LGBTQ+ identities in accepting and liberal environments whilst studying at one UK university. These counter-narratives challenge the dominant discourses of homophobia, victimization and harassment which are well-documented in the literature (Greene and Banerjee, 2006; Kulkin, 2006; Peterson and Gerrity, 2006).

However, despite these positive narratives, university spaces once described as “threateningly straight” (Epstein et al., 2003, p. 138), are places where varying levels of “outness” or self-censorship (Formby, 2012, 2013) may exist. Even where LGBTQ+ students experience university spaces as liberal and accepting, the heterosexist and heteronormative discourse can result in them modifying their behavior so as not to transgress heterosexual norms (Taulke-Johnson, 2008).

Given that there is a paucity of research which present positive narratives of LGBTQ+ students in higher education, this was identified as a priority within the context of this study. Also, since, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have explored LGBTQ+ students' perspectives using a longitudinal study design, this was also a key contributing factor which influenced the design of this study.

Conceptual Frameworks

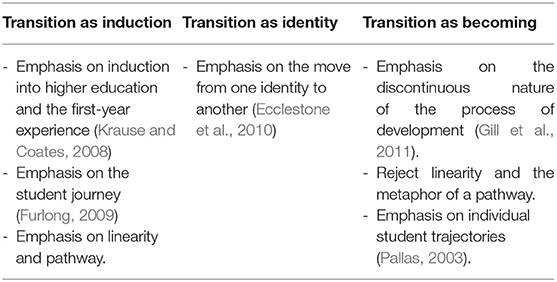

Not all transitions research presents the conceptualization of transitions to university, and not all conceptualization cover all aspects of transitions. Transitions research broadly categorizes higher education transitions into three perspectives; transition as induction, change in identity and becoming (Table 1).

We conceptualize transition to university as a dynamic ongoing process of educational, social and psychological adaptation due to changes in context, interpersonal relationships and identity, which can be both exciting and worrying (Jindal-Snape, 2016). This conceptualization can be further understood by using the Multiple and Multi-dimensional Transitions (MMT) Theory (Jindal-Snape, 2012) which acknowledges that higher education students experience multiple changes at the same time, such as moving to a new city, organizational culture, higher academic level. Not only will they adapt to these changes over time, their multiple transitions will trigger transitions for significant others, such as their families and professionals, highlighting the multi-dimensional nature of transitions. Rather than viewing transitions as linear and sequential, MMT theory assumes that multiple transitions occur synchronously. In addition, the theory suggests that transitions for individuals will also result in transitions for other people and institutions that they are connected to.

We can also understand transitions through Meyer's (2003) theory of Minority Stress which includes three elements: circumstances in the environment (general stressors); experiences in relation to a minority identity (distal stressors); and anticipations and expectations in relation to a minority identity (proximal stressors).

According to Meyer (2003), general stressors are situated within the wider environment. These environmental stressors may include experiences of social deprivation, financial pressures or stressors within relationships. These stressors may be experienced by individuals regardless of minority status. In contrast, minority stressors relate to an individual's identity and their association with a minority group (Meyer, 2003), such as the LGBTQ+ community. Thus, individuals who identify with non-normative gender identities and sexual orientations may experience minority stressors which also intersect with general stressors. According to Meyer (2003) minority stressors are categorized as either distal or proximal stressors.

Distal stressors include the direct experience of rejection, discrimination, prejudice and stigma based on the individual's minority stratus, in this case, LGBTQ+ students. Proximal stressors relate to an individual's perception and appraisal of situations. Students who identify as LGBTQ+ may anticipate rejection, prejudice and discrimination based on their previous experiences (distal stressors) of homophobic, biphobic and transphobic abuse and prejudice. Meyer's model identifies affiliation and social support with others who share the minority status as critical strategies which can “ameliorate” the effects of minority stress and he argued that, in some cases, a minority identity can become a source of strength if individuals use their minority identity as a vehicle to pursue opportunities for affiliation with others who share the minority status.

Transitions can expose individuals to various stressors. However, for individuals with a minority status, such as those who identify as LGBTQ+, exposure to proximal and distal stressors during transitions can result in negative transitions occurring. We therefore argue that there is an interaction between the two conceptual frameworks which supports their relevance in the present study. The first research question will draw on MMT theory to identify the types of transitions that participants experienced. The second research question addresses whether these transitions were positive or negative. The final research question explores the factors which influenced participants' transitions. To address this third question, we will explore the extent to which minority stress, and other factors, influenced participants' transitions.

Research Questions

This study addressed the following research questions.

- What transitions did the participants experience throughout the duration of their higher education studies?

- What were their transitions experiences and their impact on the participants?

- What factors influenced the participants' experiences of transitions?

Materials and Methods

This section outlines the research design, the ethical considerations associated with the study and the methods of data collection and data analysis.

In line with our conceptualization of transition as an ongoing process, we undertook a longitudinal study. We used multiple methods of data collection for crystallization of a complex and rich array of perspectives (Richardson and St. Pierre, 2005). To the best of our knowledge, a longitudinal study design has not been adopted with young people who identify as LGBTQ+ before. In addition, we did not source studies which utilized the breadth of research methods that we adopted in this study. Given the sensitivities involved in this research, we used a case study approach. This paper presents a cross-sectional analysis of the data to identify common themes across the cases. These themes included transitions, stress, resilience and coping mechanisms. The theme of “transitions” was then further sub-divided into types of transitions that were evident across the five case studies but not necessarily all evident in each single case study. Types of transitions included identity, social, academic, professional and psychological transitions.

Interviews

Longitudinal narrative interviews can illuminate changes across an aspect of a participant's life (West et al., 2014). Therefore, in-depth semi-structured interviews were used to explore the participants' experiences of transitions into, and through, higher education. Interviews were conducted at three points during the study; once in the first year of their studies, once during the second year and once during the final year. In each interview participants were asked the following questions:

- What social connections and/or personal relationships have you established and how are these going?

- How are you getting on with your academic studies?

- How are you getting on in your accommodation?

- How would you describe your mental health now and why?

- What challenges or successes have you experienced?

In addition, participants were given some ownership of the interviews through identifying pertinent foci for discussion that related to their on-going experiences based on the photographs they had taken and their recorded audio-diaries. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed.

Diaries

Audio and written diaries can enable participants to efficiently record their on-going experiences, thus facilitating data collection in real time as participants interact with the different contexts which influence their lives (Williamson et al., 2015); they offer unique insights by capturing critical events as they occur (Bernays et al., 2014). Diary methods can provide “a continuous thread of daily life” (Bernays et al., 2014, p. 629) and they can capture a “record of the ever changing present” (Elliot, 1997, p. 2). For this reason, this method was deemed to be particularly suitable for this longitudinal study. Participants were invited to submit longitudinal audio diaries between interviews. Many used the audio diary method as an opportunity to document and reflect on critical incidents which related to their transitions. No limit was placed on the number of diaries that participants could submit. Participants recorded their audio diaries on their mobile phones and uploaded these as MP3 files to a password protected electronic folder which only they and the researchers had access to.

Photo-Elicitation

To complement data collection through interviews and audio-diaries, photo-elicitation was used, which is becoming increasingly popular in qualitative research (Gibson et al., 2013). Participants were asked to construct meaning from photographs (Dunne et al., 2017) and it helped them express their emotions, feelings and insights (Lopez et al., 2005). The participant-generated photographs also provided opportunities for them to document their ongoing experiences making it particularly suitable for this longitudinal study. Participants were invited to submit photographs between interviews. They were informed that the photographs must not represent people (to ensure that people who had not consented were not in photographs) but should reflect their experiences of transitions. Time was allocated in each interview for participants to provide meaning to the photographs.

Participants

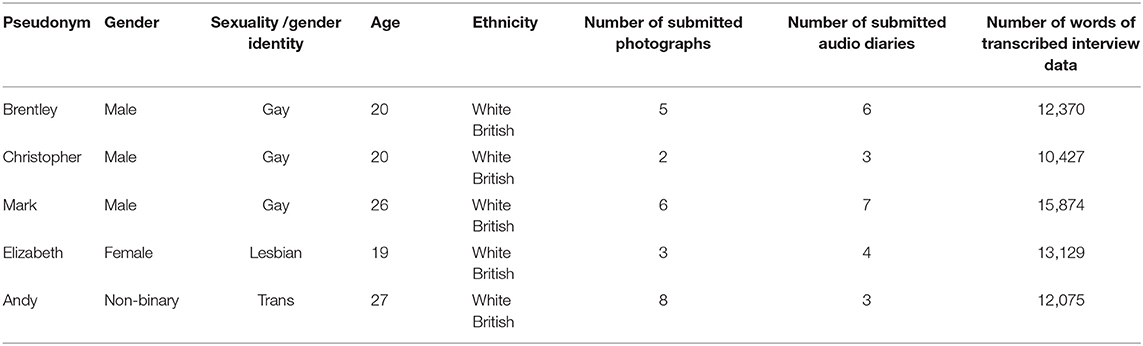

Participants who identified as LGBTQ+ and were in the first year of an undergraduate degree course were recruited. They were recruited from one university in England. The researchers did not know or teach the students. This reduced the power imbalance between the main researcher and the participants. An e-mail was circulated across three university departments to recruit participants to the study. This secured five participants who could demonstrate a sustained commitment to the study over a 3-years period. There was no attrition. Details of the participants are shown in Table 2. Pseudonyms have been used.

Ethical Considerations

Informed consent was sought using a participant information sheet and consent form. Participants were assured of their rights to confidentiality and anonymity. The research explored sensitive aspects of the participants' experiences of transitions including their mental and emotional health. Participants were pre-warned about the sensitive nature of the research and signposted to support services both within and beyond the institution. Ethical approval was obtained by the University's Research Ethics Committee.

Data Collection

Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed by the first author. Audio diaries were also transcribed by the first author. Participants submitted photographs to a secure electronic folder. These were discussed during the interviews. The participants' interpretations of the photographs were digitally recorded and transcribed during the interviews by the first author. All transcriptions were verbatim. Table 2 shows the amount of data that were collected during this study.

Data Analysis

This study used thematic analysis as the method of analysis. Case studies of each participant were produced from the raw data to illustrate the participants' experiences of transitions. The themes were drawn from the raw data for each participant. Braun and Clarke (2006) have argued that “thematic analysis should be the foundational method for qualitative analysis” (p. 78). The transcripts were analyzed using Braun and Clarke's (2006) six-step model to generate themes. This process was conducted by the first author and the themes were validated by the other authors. Once the themes were identified for each separate case, cross-sectional analysis was used to identify themes from across five case studies (Braun and Clarke, 2006). This process involved comparing the themes from across the cases and identifying the common themes which were evident in all cases.

Results and Discussion

The following section summarizes the findings arising from the cross-sectional analysis of the five case studies. Brief information is first provided about each participant to set the context.

Brentley

Brentley's initial transitions to university were not smooth. He had started a course the previous year in a different institution and had become heavily involved in the LGBTQ+ scene. He did not develop positive social connections with his peers in student accommodation. Brentley engaged in substance abuse as a result of his participation in the scene and this resulted in poor mental health. Brentley withdrew from his course and re-commenced his higher education the following year at a different university. His second attempt at higher education was much more positive. He excelled on his course and made good social connections due to making a deliberate choice to live with professionals rather than students. He challenged homophobia on campus when he experienced it and demanded changes to university policies and practices to address this.

Christopher

Christopher's initial transitions to university were positive. At the start of his degree he entered a relationship which provided him with positive self-worth. However, during his second year the relationship dissolved, and this had a negative effect on his academic, social and psychological transitions. Christopher accessed support from the university counseling service and eventually his mental health started to improve. With this support he was able to complete his course successfully.

Mark

Mark was a mature student in his late twenties. Prior to coming to university, he had experienced domestic abuse in a relationship, and he had also been raped. His first year of university was dominated by the rape trial and he sought support from the university counseling service. He was initially rejected by the service because he was informed that the service did not support male rape victims. He successfully challenged this and eventually he was able to gain access to counseling. His mental health improved as time progressed. He developed good social connections through his participation in the LGBTQ+ scene and he experienced positive academic transitions once his mental health started to improve.

Elizabeth

Elizabeth's transitions into student accommodation were not smooth due to experiencing micro-aggressions from peers. She moved out of student accommodation and moved in with her long-term partner who was also studying at a different institution in the same city. Following this, her transitions through university were generally positive. She excelled in her academic studies and it contributed to good self-efficacy. She developed a secure social network of friends and rejected the LGBTQ+ scene. She was undertaking a course of initial teacher education and was exposed to discrimination during one of her placements.

Andy

Andy was a mature student. Andy used they/them pronouns. They had experienced homophobia in the workplace prior to coming to university. At university they became an active member of the LGBTQ+ society and through this they experienced positive social transitions. Academic transitions for Andy were smooth. However, professional transitions were problematic. Like Elizabeth, Andy was training to be a teacher and experienced direct discrimination during one of their school placements. This resulted in Andy challenging university policies and practices in relation to LGBTQ+ inclusion.

Multiple and Multi-Dimensional Transitions and Support Systems

All five participants experienced transitions across several domains (Jindal-Snape, 2012). These included social, academic, psychological, professional, and identity transitions.

Apart from Andy, all had moved away from home to study and had to develop new social connections. They all successfully navigated their academic transitions, although for some this was easier than for others. Mark was frustrated about the slow pace of learning on his course. Christopher was able to cope with the academic demands of his course, but he was not motivated by the subject he had chosen to study. Elizabeth, Brentley and Andy all excelled on their courses, and consequently, their self-efficacy improved. They emphasized their academic competence by stating the grades they were achieving. Mark and Andy experienced psychological transitions by accessing support from the counseling service to enable them to overcome previous trauma. All had come to terms with their sexuality or gender identities prior to attending university but most chose not to primarily define their identities in this way. However, Brentley, Elizabeth and Christopher said that they partially concealed their sexuality, not because they felt obliged to do so, but because they did not consider this facet of their identity to be significant.

Navigating professional domains was particularly problematic for Elizabeth and Andy, who were both training to be teachers. However, they used their negative experiences to bring about positive changes at a structural level which resulted in a transition for their institution. The participants navigated these various transitions to varying degrees as they moved between academic, social, psychological, professional and other domains within the same timeframe. Participants' willingness to challenge structural discrimination (Mark) and homophobia (Christopher) also resulted in changes to university policies.

All participants drew on their peer networks to support them through the transitions that they experienced rather than accessing support from their parents. For example, Elizabeth and Christopher drew heavily on the support from their personal relationships and friendships. Elizabeth's transitions also resulted in transitions for her partner when she left her university accommodation to move in with her. Mark, Andy and Brentley gained their social capital from friendship groups, which they had established through shared housing (Brentley), through participation in the scene (Mark, Andy) or through participation in the LGBTQ+ student society (Andy). For all participants, their social connections were critical in supporting them to adapt to the changes that they experienced.

The social capital that the participants held was critical to their ability to adapt to new situations as it enabled them to provide psychosocial support (Lee and Madyun, 2008). Elizabeth drew on her social networks and personal relationship for this purpose when she experienced negative interactions with her peers in student accommodation. Rienties et al. (2015) emphasize how social capital can provide a sense of belonging to a social group. Rienties and Nolan (2014) highlighted the important role of social capital in reinforcing a sense of social identity. Rienties and Jindal-Snape (2016) stressed the role of social capital in providing solidarity and mutual support. The LGBTQ+ society and the scene provided Andy with solidarity, mutual support, a social identity a sense of belonging and social inclusion (Putnam, 2001). These factors played a role in supporting Andy to navigate multiple transitions. Mark's social capital was derived from the scene. Brentley's social capital was derived from his friendship group but also from online networks which facilitated social connectivity and access. Brentley's restricted access to social capital in his first university resulted in him withdrawing from the institution. Thus, limited social capital played a critical role in Brentley's initial negative transitions into higher education. Christopher's social capital was derived from his relationship with his partner, but his resilience was detrimentally affected when this relationship broke down.

Research demonstrates that being part of a group is important for successful transitions (Rienties and Jindal-Snape, 2016). However, so too is self-determination (Deci and Ryan, 1985; Rienties and Jindal-Snape, 2016). Students who are highly motivated with goals and aspirations are more likely to experience successful transitions at university (Rienties and Jindal-Snape, 2016). Self-determination was evident in several case studies. Brentley and Elizabeth were motivated to achieve good academic results. Mark was motivated to achieve a successful lucrative career as a result of his degree. Their self-determination enabled them to successfully navigate transitions. Self-determination was less evident in Christopher's case and this might explain why he struggled with his course following the breakdown of his relationship. Andy's motivation to advance equality and social justice was a form of self-determination which enabled them to successfully navigate transitions.

The data were consistent with MMT theory (Jindal-Snape, 2012). Transitions were not pre-determined or linear, but rhizomatic. They were an everyday occurrence rather than linear and sequential. The participants experienced synchronous transitions as they navigated different domains daily. Transitions were generally positive in that participants experienced university as largely positive.

Identity Transitions

Transition was not a process of moving from one identity to another (Ecclestone et al., 2010) but a process of exploring multiple identities, often within the same timeframe. Thus, participants weaved in and out of multiple identities (professional, academic, personal, relational and social identities) rather than moving from one identity to another (Jindal-Snape, 2016). For most, their sexuality was not critical to their sense of identity in that they did not use it to define themselves.

The participants also mitigated stress through the extent to which they allowed the LGBTQ+ label to define their identities. Identity transitions were a part of the participants' experiences of university. Although some embraced their LGBTQ+ identities (Andy), others invested in developing their academic (Brentley, Elizabeth) or social identities (Mark, Andy, Elizabeth). The participants were particularly keen to explore multiple identities. However, identity was also a push and pull factor which influenced other transitions as well as being experienced as a transition. Some participants emphasized that their LGBTQ+ identity was not their primary identity (Brentley, Elizabeth). This allowed them to navigate other transitions more smoothly. This was evident, for example, when Brentley rejected the scene and “all that jazz” (Brentley, interview 1) to focus on investing in his academic transitions. Elizabeth was also not invested heavily in her lesbian identity and this enabled her to focus on her academic and social identities. Identity is therefore an influencing factor which enabled some participants to successfully navigate other transitions.

My LGBT identity does not represent my whole identity. It is part of me. Before I came to university people saw me as a lesbian. But when I came to university, I decided that I could be whoever or whatever I wanted to be. I pushed back my LGBT identity a little and although I have developed friendships with other LGBT people, we don't just talk about being LGBT. We have other interests (Elizabeth, interview 1, October 2017).

I didn't accept my sexuality and gender at first but now I do. I can't deny who I am. However, my gender and sexuality are only fragments of me. They are not the whole me (Andy, interview 1, November 2017).

Coleman-Fountain (2014) discusses how young LGBT individuals often situate themselves within a post-gay paradigm. That is, they resist being defined by their sexuality or gender identity or even being defined by anything. They question the meaning of labels which trap them into a narrative of struggle and instead often choose to embrace a narrative of emancipation (Cohler and Hammack, 2007) in which sexuality or gender identity are not the prime aspect of a person's identity. It could be argued that repudiating labels is an attempt by individuals with minority identities to establish an identity as an “ordinary' person” (Coleman-Fountain, 2014). Brentley was keen to emphasize that being gay was only one part of his identity and he identified the importance of his identity as a runner, a student and a brother. Elizabeth was proud of her academic identity which was more significant to her than her identity as a lesbian. Mark spoke a lot about his social identity by emphasizing his friendships, but also about his identity as a professional within the workplace. Christopher emphasized his identity as a partner within a relationship rather than his identity as a gay man. Andy emphasized their social and professional identities rather than their non-binary identity. Therefore, it could be argued that these were direct attempts by the participants to emphasize the “ordinariness” of LGBTQ+ people (Richardson, 2004).

Literature demonstrates how some people claim identities through labels, but others resist them (Hammack and Cohler, 2011). Although none of the participants resisted defining themselves by their sexuality or gender identity, some did define themselves by identities that made them appear to be “ordinary,” thus refuting divisions based on non-normative identities (Hegna, 2007). Brentley repudiated the stereotypes that are typically associated with being gay, including flamboyancy, dramatization and other associations with “being camp”. He acknowledged that being gay meant that he was attracted to other males, but he rejected all the “baggage” that is stereotypically associated with being gay (see also Savin-Williams, 2005; Coleman-Fountain, 2014). For Brentley, these characteristics were not a valid form of masculinity (Coleman-Fountain, 2014) and he sought an authentic identity which extended beyond the boundaries of the caricatures that are dominant in the media and on the LGBTQ+ scene (Savin-Williams, 2005). Christopher, Mark and Elizabeth also acknowledged their sexuality, but they rejected the associated stereotypes and refused to be defined by either of these.

None of the participants denied the labels that related to their sexuality, but they questioned their meaning, particularly Brentley and Elizabeth. Apart from Andy, they turned their sexuality into a secondary characteristic and invested instead in what Appiah (2005) refers to as a narrative of the self. They rejected collective ascriptions. They acknowledged their non-heterosexual feelings but consciously refuted this as the primary aspect of their identity (Dilley, 2010). They refused to be unequally positioned in a hierarchy of sexuality and gender which is embedded with assumptions and stereotypes (Coleman-Fountain, 2014). Although research suggests that traditional labels (gay, lesbian, homosexual) may be perceived as too limiting (Galupo et al., 2016) and are often associated with stigmatization and negative stereotypes (White et al., 2018), most participants in this study did not reject these labels. However, they did not use the labels to describe a prime aspect of their identities.

Mark's decision to “own” the label when he was subjected to homophobic abuse was a strategy for not internalizing the effects of the distal stressor to which he was exposed. Owning the label was also evident in Brentley's account of his experience in the university gym when he witnessed homophobic language which was explained as banter, and Christopher's account of his experience on the bus when he was subjected to homophobic abuse. However, although these participants identified as gay, it was not the primary component of their identities but when they experienced inequality, they felt compelled to address it, thus demonstrating moral courage.

Within the context of this study, the way in which the participants negotiated their identities served to minimize the effects of minority stress (Meyer, 2003). Their sexuality and gender identities were only one component of their overall identity. They had already integrated these identities into their overall identities. When they experienced minority stress the effects of it were negated by investing in other aspects of their identity. Elizabeth experienced micro-aggressions in university accommodation but her identities as a partner, a friend and a student compensated for the stressors to which she was exposed. Brentley emphasized the importance of being a runner, a brother and a student as well as being gay. These multiple identities helped to mitigate the effects of minority stress. Christopher's identity as a partner within a relationship helped to minimize the effects of micro-aggressions to which he was exposed. Andy's prime identity was derived from being an active member of the LGBTQ+ student society, which helped to negate the effects of minority stress. Mark's identity as a mature student and an employee helped to mitigate the effects of homophobic abuse.

Thus, this study contributes to theory in that it has identified a wider range of coping mechanisms to mitigate minority stress than Meyer (2003) originally suggested in his model.

Social Transitions

Literature demonstrates that self-worth is influenced by the quality of our relationships with others and the extent to which we meet other people's expectations (Jindal-Snape and Miller, 2010). However, during transitions individuals may lose the relationships that have previously contributed to positive or negative self-worth and they may receive different feedback from new relationships which can have a positive or negative effect on self-concept (see the seminal works of Cooley, 1902; Rogers, 1961; Coopersmith, 1967). All participants described difficult experiences prior to coming to university which impacted negatively on their self-worth. However, their social transitions at university were largely positive in that they established new friendships and relationships which contributed positively to their self-worth and therefore their overall self-esteem.

Social transitions facilitated a sense of belonging for the participants. The importance of the LGBTQ+ scene in fostering a sense of belonging for individuals with non-normative identities is a theme in the literature (Holt, 2011). However, although Andy and Mark had embraced the scene, Christopher, Brentley and Elizabeth rejected it and sought their sense of belonging from other sources including friendship groups and relationships. Literature demonstrates that the scene is a paradoxical space which offers support and validation but also presents risks (Valentine et al., 2003; Formby, 2017). It can also be an exclusionary space (Formby, 2017). Brentley experienced the scene both as risky and a place of exclusion, thus resulting in him seeking a sense of belonging from other social networks. He also initially struggled to establish social connections in student halls which resulted in negative social transitions. However, he managed to build good friendships later when he moved into private housing.

Other students were acting like a bunch of buffoons, pushing each other down the stairs and pulling each other's pants down. I didn't fit in in student halls (Brentley, interview 1, October 2017)

I was going out, getting drunk and was hung over 3 days a week. I found a gray hair and that was caused by the scene. I had my drink spiked. It is all drama on the scene, people saying, “this person has been with this person” and so on. I could not establish meaningful relationships. The gay scene is like a “stale soup”. Every ingredient has touched everything, it is all homogenous and everything tastes the same. Occasionally you get the odd bit of Cajun spice (young new guys) who join which makes it taste better (Brentley, interview 2, October 2018)

For the last two years, I have deliberately chosen to live with people who have jobs rather than students. I have been able to build strong friendships with the people I live with. (Brentley, interview 3, June 2019).

Christopher and Elizabeth felt excluded on the scene because they did not identify with others and gained their sense of belonging from friendships, intimate relationships, online networks and academic study. Mark and Andy experienced a sense of inclusion and therefore belonging on the scene. Regardless of how their sense of belonging was met, experiencing belonging was critical to the participants' self-esteem. Collective self-esteem refers to an individual's evaluation of their own worthiness within a social group (Hahm et al., 2018). Andy gained this through participating in the LGBTQ+ society which provided a sense of belonging. Research demonstrates that community connectedness is associated with increased psychological and social well-being (Frost and Meyer, 2012). The data in this study also suggest that belonging is associated with self-esteem. Experiencing a sense of belonging in the institution (Elizabeth), within friendship groups (Brentley, Elizabeth), within the LGBTQ+ community (Mark, Andy) and within relationships (Christopher) supported the participants to experience a positive sense of self-worth.

Academic Transitions

All participants experienced smooth academic transitions during their time at university and these provided participants with positive self-worth.

I love learning. I am getting 70 s and 80 s in my assignments and I am beginning to see myself as an academic (Christopher, interview 1, November 2017)

I'm just in the coffee shop with my friends and we are discussing Foucault. I never thought I would be bright enough to do things like this. I feel like an academic (Christopher, audio diary, February 2018).

Positive academic transitions were particularly evident with Elizabeth who realized that she had good academic ability at university, despite describing herself as an “average” student during her time at school. Each participant successfully completed their degree course.

I was labeled as underachieving in sixth form and I felt defeated by it. I thought, what's the point? However, since coming to university I have been diagnosed with dyslexia. I now know that I'm not stupid. I love learning. I am getting 70 s and 80 s in my assignments (Elizabeth, interview 1, October 2017).

Professional Transitions

Transitions into professional roles were not smooth for Elizabeth or Andy. Both were studying on professional teacher training courses and both experienced negativity from colleagues in the workplace during their professional placements. Andy used this negative experience to implement changes to mentor training programmes at the university to ensure that workplace mentors understood their legal duties to prevent discrimination during employment. These two cases demonstrate that universities can meet their legal obligations in relation to ensuring equality for students on campus, but this can break down when students carry out part of their courses within workplace contexts. However, the university is still legally responsible for the entire student experience, even when students are studying away from the campus. Andy and Elizabeth's negative experiences of professional placements resulted in difficult transitions into their chosen profession but also resulted in positive changes to university policies and practices, thus reflecting the multi-dimensional nature of transitions.

Psychological Transitions

Social, professional and identity transitions can impact on psychological transitions. Therefore, transitions in one domain can impact, positively or negatively, on transitions in other domains. We use the term “psychological transitions” to mean the changes to the participants mental health as a result of other transitions. Some participants concealed their identities in the workplace, in their homes and communities to reduce the likelihood of experiencing distal stressors (Andy, Mark, Elizabeth), resulting in internalized homophobia and psychological distress. However, although concealment was a strategy used by some participants as a protective factor to mitigate stress, it resulted in negative psychological transitions. Negative social transitions resulted in Brentley developing poor mental health during his first year at university. Negative professional transitions in the workplace resulted in Andy developing mental ill health and requiring psychological intervention. Mark's negative experiences in a relationship resulted in him self-harming and requiring psychological support. Christopher's relationship break-up also resulted in mental ill health. Lack of agency or restricted agency impacted detrimentally on their identity transitions prior to coming to university. However, during their time at university, participants embraced their multiple identities which resulted in positive psychological transitions. Some participants experienced positive psychological transitions by accessing support from the counseling service to enable them to overcome previous trauma (Mark, Andy).

Stress

The participants in the study drew on their networks to mitigate the effects of stress. Networks included friends, relationships and family, although support from family networks was not a dominant theme in the narratives. The importance of social networks in alleviating stress is a consistent theme in the literature (Montgomery and McDowell, 2009; Rienties and Jindal-Snape, 2016). Mark and Andy mitigated the effects of stress not only through social networks but also through accessing psychological intervention. The role of psychological intervention in mitigating stress is also a consistent theme in the literature (Meyer, 2003).

Some strategies for mitigating stress were evident through the photo-elicitation. Regardless of the support they gained from others and its role in mitigating stress, the participants also mitigated stress through the extent to which they allowed the LGBTQ+ label to define their identity.

The strategies employed by the participants to mitigate the effects of stress were more varied than those strategies originally outlined in Meyer's (2003) model. Meyer's model of minority stress emphasizes social support as the key approach for mitigating stress. Although the participants did rely on social networks to mitigate stress, they also largely underplayed the significance of their LGBTQ+ identities by embracing other aspects of their identities. This helped to counteract the effects of minority stress.

Resilience

The participants presented themselves as courageous individuals who were prepared to challenge inequality to advance an agenda for social justice. Their courage in addressing discrimination to advance equality and social justice resulted in empowerment which enabled them to stay resilient (Christopher, Mark, Andy). Their ability to invest in their academic identities improved their self-esteem, which made them more resilient to minority stressors (Brentley, Elizabeth). In addition, their ability to negotiate their identities by presenting themselves as heterosexual (Brentley, Mark, Christopher) protected their self-worth which enabled them to be resilient.

In relation to external factors, the participants all developed social networks which enabled them to stay resilient. This demonstrates the relational nature of resilience (Jindal-Snape and Rienties, 2016). Most established friendships in their accommodation rather than on their course, although for others their capacity to do this was restricted due to not living in student accommodation (Andy). Some chose to participate in the “scene” (Andy, Mark) but others rejected the scene because they did not identify with the scene culture or the other people on the scene (Christopher, Elizabeth, Brentley). The scene was therefore not a consistent source of support for all participants and for Brentley it was a source of stress. Jindal-Snape and Rienties (2016) have highlighted how support networks can become risk factors if they break down. Brentley became increasingly dissatisfied with the scene and it contribute to him developing substance abuse, poor mental health and eventually to him withdrawing from his first university. Although he initially participated in the “scene” he eventually rejected it because it had a detrimental impact on his transition to university. In line with Pachankis et al. (2020) who present a case for intraminority stress, status-based competitive pressures within the LGBTQ+ community contributed, at least partially, to Brentley developing poor mental health. Some participants participated regularly in online networks by joining Grindr (Brentley, Mark). This is a gay dating app which allows people to connect and meet socially or for sex. For these participants, this online platform played a critical role in supporting their resilience because it enabled them to connect with other people who also identified as queer. Elizabeth had formed a strong social network offline and this supported her resilience, particularly when she encountered problems in university accommodation. Mark drew on the support from close friends in his hometown in addition to the friendships he had established in his accommodation and on the scene. None of the participants identified family as a strong source of support. This supports recent research by Gato et al. (2020) who found that LGBTQ+ young people tend not to identify their families as a source of social support, despite this being a dominant theme in the general literature on resilience (Roffey, 2017). For some, relationships with family members had become impaired due to the disclosure of their sexuality or gender identities (Christopher, Mark, Elizabeth). In addition, none of the participants established strong relationships with people on their courses. Friendships were mainly established through participation in the scene (Mark), friends of partners (Elizabeth), friendships established through the LGBTQ+ society (Andy) and friendships within accommodation (Brentley). In addition, although literature has identified the importance of student-staff relationships in supporting student resilience in higher education (Evans and Stevenson, 2011) this did not emerge as a protective factor in the data.

Course and institutional level protective and risk factors were also evident in the data. Out of all the participants, Elizabeth demonstrated the greatest engagement in her studies. Her love of studying her subject in university supported her resilience. Participants highlighted the fact that their taught modules did not include curriculum content on LGBTQ+ identities and experiences, even though this content could have been easily embedded into the curriculum. This aligns with existing literature (Formby, 2015, 2017). In addition, none of the participants were given the opportunity to complete an assessment task on LGBTQ+ identities and experiences, again supporting existing literature (Formby, 2015). This could have been easily embedded into Christopher's film making degree or Elizabeth's education degree. This absence of LGBTQ+ curriculum visibility did not help the participants to experience a sense of belonging at course level and it impacted detrimentally on their academic transitions. It contributed to Brentley withdrawing from his first degree course and it was a factor in explaining why Christopher was not fully invested in his course.

Institutional factors also served as protective and risk factors in relation to resilience. A negative campus climate was evident in some cases (for example Brentley's experience in the changing rooms). However, the participants largely had positive experiences within the institution which served as protective factors. Some participants had engaged in a peer mentoring programme (Christopher, Mark) which provided them with agency and Elizabeth had been given the opportunity by the student union to participate in community volunteering. These actions served as protective factors because they provided the participants with meaningful opportunities to make a positive contribution to their communities and they provided them with agency.

Coping Mechanisms

Meyer's (2003) model of minority stress identifies coping and social support as an important strategy to mitigate the effects of minority stress. Access to social support networks with others who share the same minority status can provide individuals with solidarity and a positive affirmation of identity. The present study found that although some participants formed collectives and joined social networks with others who also identified as LGBTQ (Mark, Andy), some participants rejected these collectives and networks and developed different coping mechanisms. Brentley and Elizabeth developed their sense of self-competence through experiencing successful academic transitions. They invested in their academic identities and this made them more resilient to the minority stressors which they were exposed to. Their improved self-competence increased their overall self-esteem which helped them to mitigate the effects of stress. The Equality Act 2010 also served as a coping mechanism and supported participants to challenge discrimination that they were exposed to on campus and in school prior to attending university (Brentley, Elizabeth). Some participants drew on social networks with friends who did not identify as LGBTQ+ (Brentley, Mark, Elizabeth). Support from participants' families was not a significant coping mechanism, although Elizabeth drew on support from her partner's family rather than her own family. Some participants drew on counseling services (Christopher, Mark, Andy) as a coping mechanism.

Limitations

There are several limitations to the study design and data collection process which must be explicitly highlighted. Although the sample size was small and therefore generalizations to other participants and institutions cannot be made, nonetheless the study provides rich data which could not have been captured through a quantitative study. It was never the intention to claim generalisability. Although we acknowledge that scholars working within the positivist paradigm would criticize the small sample and question the reliability of the findings, nevertheless we believe that this study makes an important contribution to qualitative research.

The sample was male dominated and three out of the five participants were gay. A representative sample would have demonstrated a better representation of different genders, sexual orientations and gender identities. Only one participant was included in the sample who identified as trans and most participants identified as “gay,” resulting in a minority of lesbian and bisexual participants. A more carefully selected sample would have included a more equal representation of gender identity and sexual orientation and this would have increased the reliability of the study. In addition, three of the participants were aged between 18 and 21 and only two participants over the age of 21 were included in the sample. No participants were over the age of 30 and therefore the study does not represent the experiences of older LGBTQ+ students who come to university to study undergraduate programmes. This compromises the reliability of the study. The sample was relatively homogenous in that it did not adequately represent intersectional identities, for example the intersectionality between race, disability and non-normative gender identities and sexualities. All participants were white British. In addition, the study focused exclusively on the experiences of undergraduate students. Postgraduate taught students and postgraduate research students were not included in the sample and therefore the study does not represent the full LGBTQ+ student body. Again, this compromises the generalisability of the findings.

Future Research

Future research should explore the transitions experiences of students with other minority identities which intersect with identities based on sexual orientation and gender. Transitions research could explore the intersections between social class, race, disability and sexual orientation and/or gender identities. In addition, future research should explore lesbian, bisexual and trans students' experiences of transitions. Finally, future research should explore the experiences of postgraduate students who identify as LGBTQ+.

Conclusion

All participants had positive and negative experiences of higher education. Higher education was a life phase in which the participants could explore and develop their personal and academic identities, come to terms with their sexual orientation or gender identity and contribute to the development of inclusion. Negative experiences were reported but largely the participants' experiences of transitions were positive.

Each participant experienced Multiple and Multi-dimensional Transitions which they navigated, often within the same timeframe. These included geographic transitions (moving away from home to a new city), social transitions (meeting and establishing friendships and relationships with new people), academic transitions (coping with the demands of academic study in higher education and adapting to new approaches to teaching, learning and assessment) and identity transitions (developing their identities as individuals who identified as LGBTQ+, developing a student identity and transitioning from student identities to professional identities for students studying on professional courses). As they progressed through their studies, they became more confident about their multiple identities and this had a positive impact on their overall sense of self.

The participants had both positive and negative experiences of transitions. Although some participants experienced both distal and proximal stressors due to their sexual orientation or gender identities, each was able to mitigate the effects of these stressors. Overall, all participants had a positive university experience and they navigated the multiple transitions successfully. All participants demonstrated a strong sense of agency and they were proud of their sexual orientation or gender identity. However, two participants actively decided to conceal their personal identities in specific contexts, thus feeling the need to negotiate their identities. Although they recognized that concealment of their identities should not have been necessary, they demonstrated a strong external locus on control, thus protecting their sense of self.

The participants demonstrated a strong sense of resilience which helped them to navigate each of the different transitions successfully. The themes of resilience, agency, locus of control and minority stress were common across all participants. There were variations between the participants in how they navigated the different transitions and the sources of support that they drew upon to foster their resilience. However, what emerged strongly in the data were largely positive narratives rather than victimized accounts which are prevalent in the existing literature.

The data suggest that the institution should ensure that a whole-institutional approach to LGBTQ+ inclusion is implemented, specifically to address aspects such as curriculum inclusivity and to further embed a positive campus climate. The institution should continue to ensure that students undertaking professional placements are not exposed to prejudice or discrimination by continuing to embed LGBTQ+ equality training into professional development courses for workplace mentors.

To our knowledge, this study is the first study to have studied LGBTQ+ students' Multiple and Multi-dimensional Transitions in a university context. It is the first study to our knowledge that has applied MMT theory in this context. In addition, we believe that this is the first study to adopt a longitudinal study design to explore the experiences of students in higher education who identify as LGBTQ+. It has made a unique contribution in highlighting that these students were not victims, they were active agents in their academic and life transitions. Further, the strategies employed by participants to mitigate stressors go beyond those suggested by Meyer (2003) in his minority stress model. This research supports understanding of how different transitions contribute to participants' experiences of minority stress, resilience and agency and what facilitates and hinders transitions experiences at university.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Dundee Research Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

JG collected and analyzed the data. JG wrote the first draft of this paper. SS wrote the section on minority stress, checked the references, and formatted the paper. DJ-S edited and wrote the second draft of the paper, and both finalized and approved it. All authors designed the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

JG wishes to express my thanks to my two doctoral supervisors, Prof. DJ-S and Dr. Linda Corlett who supported me in this work through their expert guidance. We also wish to extend our thanks to the participants for providing their consent to publish their quotations.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2020.00081/full#supplementary-material

References

Aldridge, D., and Somerville, C. (2014). Your Services Your Say: LGBT People's Experiences of Public Services in Scotland. Edinburgh: Stonewall Scotland.

Beemyn, B. G. (2005). Making campuses more inclusive of transgender students. J. Gay Lesbian Issues Educ. 3, 77–87. doi: 10.1300/J367v03n01_08

Bernays, S., Rhodes, T., and Terzic, K. J. (2014). Embodied accounts of HIV and hope: using audio diaries with interviews. Qual. Health Res. 24, 629–640. doi: 10.1177/1049732314528812

Bradlow, J., Bartram, F., Guasp, A., and Jadva, V. (2017). School Report: The experiences of Lesbian, Gay, bi and Trans Young People in Britain's Schools in 2017. London, UK: Stonewall.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brown, M. (2000). Closet Space: Geographies of Metaphor From The Body to The Globe. (London, UK: Routledge).

Brown, R. D., Clarke, B., Gortmaker, V., and Robinson-Keilig, R. (2004). Assessing the campus climate for gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender (GLBT). students using a multiple perspectives approach. J. College Stud. Dev. 45, 8–26. doi: 10.1353/csd.2004.0003

Chow, K., and Healey, M. (2008). Place attachment and place identity: first-year undergraduates making the transition from home to university. J. Environ. Psychol. 28, 362–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.02.011

Cohler, B. J., and Hammack, P. L. (2007). The psychological world of the gay teenager: social change, narrative, and normality. J. Youth Adolesc. 36, 47–59. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9110-1

Cole, J. S. (2017). Concluding comments about student transition to higher education. High. Educ. 73, 539–551. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0091-z

Coleman-Fountain, E. (2014). Understanding Narrative Identity Through Lesbian and Gay Youth. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York, NY: Plenum.

Department for Education (DfE) and Department of Health (DoH) (2017). Transforming Children and Young People's Mental Health Provision: a Green Paper. London, UK: DfE and DoH.

Dilley, P. (2010). New century, new identities: building on a typology of nonheterosexual college men. J. LGBT Youth 7, 186–199. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2010.488565

Dunne, L., Hallett, F., Kay, V., and Woolhouse, C. (2017). Visualizing Inclusion: Employing a Photo-Elicitation Methodology to Explore Views of Inclusive Education, Case Studies. Available onine at: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473995215 (accessed February 14, 2020).

Ecclestone, K., Biesta, G., and Hughes, M. (2010). “Transitions in the lifecourse: the role of identity, agency and structure,” in Transitions and Learning through the Lifecourse, eds. K. Ecclestone, G. Biesta, and M. Hughes (London: Routledge), 1–15.

Elliot, H. (1997). The use of diaries in sociological research on health experience. Sociol. Rev. Online 2, 38–48. doi: 10.5153/sro.38

Ellis, S. J. (2009). Diversity and inclusivity at university: a survey of the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT). students in the UK. High. Educ. 57, 723–739. doi: 10.1007/s10734-008-9172-y

Epstein, D., O'Flynn, S., and Telford, D. (2003). Silenced Sexualities in Schools and Universities. Stoke on Trent: Trentham Books.

Evans, C., and Stevenson, K. (2011). The experiences of international nursing students studying for a PhD in the UK: a qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 10:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-10-11

Formby, E. (2012). Solidarity But not Similarity? LGBT Communities in the Twenty-First Century. Sheffield: Sheffield Hallam University.

Formby, E. (2013). Understanding and responding to homophobia and bullying: contrasting staff and young people's views within community settings in England. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 10, 302–16. doi: 10.1007/s13178-013-0135-4

Formby, E. (2014). The impact of Homophobic and Transphobic Bullying On Education and Employment: A European Survey. Brussels: IGLYO.

Formby, E. (2017). How should we ‘care' for LGBT+ students within higher education? Pastoral Care Educ. 35, 205–220. doi: 10.1080/02643944.2017.1363811

Formby, E. (2015). #FreshersToFinals From freshers' Week to Finals: Understanding LGBT+ Perspectives on, and Experiences of, Higher Education. Sheffield: Sheffield Hallam University.

Frost, D. M., and Meyer, I. H. (2012). Measuring community connectedness among diverse sexual minority populations. J. Sex Res. 49, 36–49. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.565427

Furlong, A. (2009). Revisiting transitional metaphors: reproducing social inequalities under the conditions of late modernity. J. Educ. Work 22, 343–353. doi: 10.1080/13639080903453979

Galupo, M. P., Henise, S. B., and Mercer, N. L. (2016). “The labels don't work very well”: transgender individuals' conceptualizations of sexual orientation and sexual identity. Int. J. Transgender. 17, 93–104. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2016.1189373

Garvey, J. C., and Rankin, S. R. (2015). The influence of campus experiences on the level of outness among trans-spectrum and queer-spectrum students. J. Homosexual. 62, 374–393. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2014.977113

Gato, J., Leal, D., Moleiro, C., Fernandes, T., Nunes, D., Marinho, I., Pizmony-Levy, O., and Freeman, C. (2020). “The worst part was coming back home and feeling like crying”: experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans students in portuguese schools. Front. Psychol. 10:2936. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02936

Gibson, B. E., Mistry, B., Smith, B., Yoshida, K. K., Abbott, D., Lindsay, S., and Hamdani, Y. (2013). The integrated use of audio diaries, photography, and interviews in research with disabled young men. Int. J. Qual. Methods 12, 382–402. doi: 10.1177/160940691301200118

Gill, B. L., Koch, J., Dlugon, E., Andrew, S., and Salamonson, Y. (2011). A standardised orientation program for first year undergraduate students in the College of Health and Science at UWS. A practice report. Int. J. First Year High. Educ. 2, 63–69. doi: 10.5204/intjfyhe.v2i1.48

Greene, K., and Banerjee, S. C. (2006). Disease-related stigma: comparing predictors of AIDS and cancer stigma. J. Homosex. 50, 185–209. doi: 10.1300/J082v50n04_08

Grimwood, M. E. (2017). What do LGBTQ students say about their experience of university in the UK? Perspect. Policy Pract. High. Educ. 21, 140–143. doi: 10.1080/13603108.2016.1203367

Hahm, J., Ro, H., and Olson, E. D. (2018). Sense of belonging to a lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender event: the examination of affective bond and collective self-esteem. J. Travel Tour. Market. 35, 244–256. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2017.1357519

Hammack, P. L., and Cohler, B. J. (2011). Narrative, identity, and the politics of exclusion: social change and the gay and lesbian life course. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 8, 162–182. doi: 10.1007/s13178-011-0060-3

Hatchel, T., Valido, A., and De Pedro, K. T. (2019), Minority stress among transgender adolescents: the role of peer victimization, school belonging, ethnicity. J. Child Family Stud. 28, 2467–2476. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1168-3

Haver, W. (1997). “Queer research: or, how to practise invention to the brink of intelligibility,” in The Eight Technologies of Otherness, ed. S. Golding (London, UK: Routledge), 227–292.

Hegna, K. (2007). Coming out, coming into what? Identification and risks in the ‘coming out' story of a norwegian late adolescent gay man. Sexualities 10, 582–602. doi: 10.1177/1363460707083170

Holt, M. (2011). Gay men and ambivalence about “gay community”: from gay community attachment to personal communities. Cult. Health Sex. 13, 857–871. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.581390