- Center for Teaching and Learning, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States

This paper presents a first iteration of the TCOOL project as a design experiment in the education of teachers for high poverty, urban schools. The TCOOL Project embodies a new vision for the professional education of teachers that engages schools and universities in deep partnership designed to support the preparation and on-going learning of teachers. Expansive learning theory as described by Engeström and his colleagues is used to probe the opportunities for learning about teaching that TCOOL provides to practitioners in schools and universities. We found that the expansive learning theory enabled us to see that, even in its pilot run, the learning processes manifested throughout by participants in the school and university included productive deviations from our original intentions. These have led to both practical and theoretical shifts in our change effort.

Introduction

In this self-study of teacher education practice, the theoretical framework of expansive learning is used to examine a design experiment (Brown, 1992; Cobb et al., 2003a) aimed at addressing the problem of redefining and reshaping teacher education so as to answer the question of what it would take to bring the university and school together as partners in the pre- and in-service education of teachers for high-poverty urban schools. The paper begins with a review of literature related to teachers' professional learning and to the design research and expansive learning frameworks that inform the study. It is followed by an overview of the TCOOL (Teachers Community of Ongoing Learners) project whose design serves as the basis for the study. Then, using Smith and Keith (1971) approach of event analysis for the study of project implementations. This is followed by an in-depth review of the 2-year pilot phase of TCOOL during which my partners in the school and university and I were engaged in trying to prepare an environment for the school and university to successfully come together. While still very much the beginning of a design experiment in teachers professional learning (Brown, 1992; Cobb et al., 2003b, 2009), the outcomes of this initial phase of our effort appear to hold promise for scaling TCOOL to other high poverty communities as an “adaptation” (Morel et al., 2019) of traditional processes of teachers' professional education—both pre- and in-service.

Teacher Education, Expansive Learning, and Design Experiments in Education

Much of American teacher education is stuck in an unproductive and dysfunctional pattern with vast numbers of new teachers feeling unprepared for teaching and shockingly large numbers of these new teachers (roughly 50%) leaving the profession within their first 5 years (Ingersoll, 2001) thus creating a constant influx of inexperienced teachers (Ingersoll et al., 2019). Worse still, many good and experienced teachers report feeling burned out, uninspired, and frustrated by the limited options they have to enhance their teaching and learning capacities within their profession, driving many to leave classroom teaching for administration positions or other careers that offer better pay, more opportunities for professional growth, and greater personal rewards (Ingersoll et al., 2018, 2019). Tinkering at the margins of university-based teacher education has not worked. The time has come for fundamental change in the way we prepare and support the teachers of America's fifty-five million school children. The need is particularly acute for those who work with the poorest children who are often more school dependent for their development and academic learning than are children who come from families where parents are better prepared and have more resources to be co-teachers outside of school (Ladson-Billings, 1994; Delpit, 1995, 2012; Kirkland, 2013).

To prepare and support teachers to optimize the learning and achievement of children of poverty, two significant shifts must happen. The first involves shifting understandings of teacher education from preservice preparation alone to shaping programs that encompass the whole of a teacher's professional life in the context of school-based reform (Rust, 2010). This means bringing the school into the preparation of teachers and the university into the professional life of teachers IN schools (Lieberman, 2011). The second shift involves shifting the current deficit model of low expectations for children and teachers in high-poverty urban schools toward one that positions both students and teachers as partners in knowledge building (see Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1989; Scardamalia and Bereiter, 2006; Engeström and Sannino, 2010; Engeström, 2016; Sannino et al., 2016). Achieving the transformation implicit in these shifts requires committed, dynamic, and enduring collaborations between local schools, professional communities, and colleges/universities to reconceptualize teacher education in ways that encourage professional learning through high levels of practice in schools. Such a process might be described as a design experiment (Cobb et al., 2003a) wherein the familiar practices of teacher education are used in new ways with the intent of developing an innovative approach to the preparation and support of teachers for urban schools, an approach whose ultimate parameters are devised in the process of the experiment. It is likely that the outcome of such a design experiment could be construed as an example of what Engeström and Sannino (2010) describe as expansive learning, wherein learners learn something that is not yet there. In other words, the learners construct a new object and concept for their collective activity and implement this new object and concept in practice” (2).

The theory of expansive learning as a vehicle for understanding specific processes of change has been used by Engeström and his colleagues to explore a variety of organizational transformations in a number of complex networks including a municipal home care in the city of Helsinki, services of the University of Helsinki libraries, teacher education for vocational schools (Engeström and Sannino, 2010; Engeström, 2016), the work and services of investment managers in a Scandinavian bank, curriculum redesign in a middle school, and a company that manufactures hi-tech security products (Engeström, 2016). These are work settings wherein participants recognize a problem of practice but do not perceive a path toward change. As Engeström and Sannino (2010) write,

The basic argument for such a focus on work settings is that traditional modes of learning deal with tasks in which the contents to be learned are well-known ahead of time by those who design, manage, and implement various programs of learning. When whole collective activity systems, such as work processes and organizations, need to redefine themselves, traditional modes of learning are not enough. Nobody knows exactly what needs to be learned. The design of the new activity and the acquisition of the knowledge and skills it requires are increasingly intertwined. In expansive learning activity, they merge (3).

As a framework for considering change efforts, “The theory of expansive learning puts the primacy on communities as learners, on transformation and creation of culture, on horizontal movement and hybridization, and on the formation of theoretical concepts” (Engeström and Sannino, 2010, 2).

Engeström et al. identify seven typical components of the process of expansive learning: (1) Questioning (2) Analysis (3) Modeling the new solution (4) Examining and testing the new model (5) Implementing the new model (6) Reflecting on the process (7) Consolidating and generalizing the new practice (Engeström and Sannino, 2010; Sannino et al., 2016). However, the process and its outcomes are never prescribed. Hence, designing for expansive learning, precisely because of uncertainty regarding the outcomes of efforts to move an organization or group toward it, requires attention to design theory and openness to the possibility of design experiments in educational research.

Design theory when applied to education most often refers to learning, and design experiments in educational research have emerged in recent years as an important approach for the study of curricular and pedagogical innovations aimed at improving learning among children and their teachers (Brown, 1992; Cobb et al., 2003a; The Design-Based Research Collective, 2003). Brown (1992), for example, describes her study of “reciprocal teaching” as a design experiment and Bereiter and Scardamalia (1989), Scardamalia and Bereiter (2006) engage in design-based research to describe their efforts at “intentional learning.” In these and other experiments such as those by Schoenfeld et al. (1993) in mathematics or Wiggins and McTighe (2005) on “backward design” of curriculum, the design effort focuses on curriculum and the design effort uses known resources in new ways that aim at fostering critical thinking and reflective learning among children and, ultimately, for their exercising autonomy around their learning. With each of these design experiments, there is a concomitant concern about enabling teachers to engage in and support innovative practices so that their classrooms and their schools evolve as learning communities.

Teachers who work with children in these ways are often themselves engaged in new learning, specifically a form of professional learning that has them adopting what Cochran-Smith and Lytle (1999, 2009) describe as an inquiry stance and, in the, process developing “knowledge-in-practice” and “knowledge-of-practice.” This work can be done individually (Hamilton and Pinnegar, 2015), and it can be done collaboratively in communities of practice (Wenger, 1998)—teachers and researchers together. Either way, practice is examined and appropriated with regard to its efficacy for learners. This is teacher education as professional education (Rust, 2010)—preservice and inservice—that can result in a learning organization such as that described by Engeström and Sannino (2010).

At the preservice level, learning to think of teaching as essentially becoming a part of a community of learners is difficult to achieve. In part this is because of what Lortie (1975) describes as “the apprenticeship of observation”—that tacit lens on the work of teaching developed over 12 or more years of schooling which positions teachers at the front of the room, telling education to their students. In part, this is because it is unlikely that either students of teaching or their teacher educators have experienced genuine collaborative, collegial learning that moves the learner to thinking with others, to reflecting, and to working together toward deep understandings. What is needed is a radical shift in teacher education that positions it as the ongoing professional learning of teachers which, like medical education, is situated as a genuine partnership between schools and universities and is aimed at professional learning across the professional lifespan of teachers and teacher educators (Rust, 2010; Rust et al., 2019)—a design experiment.

The TCOOL Design

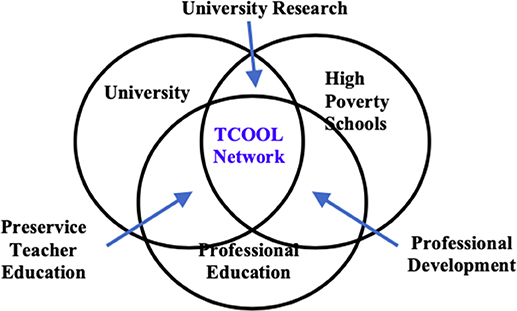

The design experiment that we have focused in on is TCOOL (Teachers Community of Ongoing Learners). Like all design experiments TCOOL involves connection between the field (practitioners) and the laboratory (researchers) (see Brown, 1992; McCandliss et al., 2003). This explicit and necessary “boundary crossing” (Cobb et al., 2003b) is critical to the desired outcome, the grand goal of creating a seamless path for professional learning among teachers. The grand design of TCOOL situates teacher education at the nexus of theory and practice. It draws community- and college/university-based assets into the local school, thus making the school a center for continuous learning for students and professional growth for teachers. The design situates the TCOOL project within the school in the larger context teacher education, that is, as nested in a university-based system. Our effort of the TCOOL project is to shift that system away from the traditional “use” of the school as a site for field experience toward genuine partnership in the preparation and support of teachers across their professional lives (Rust, 2010). In this shift, the school acts as a catalyst for change in the process of teacher education. It serves as core to generation of knowledge around teacher learning, as a hub for the study of practice by practitioners as well as researchers, and as a community resource (see Figure 1: TCOOL).

Figure 1. Developing a professional learning community: Teachers Community of Ongoing Learners (TCOOL).

TCOOL's focus is on working with high poverty urban schools and the higher ed institutions that work with them. These are schools where the percentage of students living below the poverty line far exceeds the city wide average. In New York City public schools, ~60% of families live below the poverty line, qualifying them for Title I status. In high poverty schools, this percentage is usually between 95 and 100%. In this design, high poverty urban schools come together with university programs that provide preservice teacher education and other education-related services and organizations that provide professional education related to a variety of school-based needs, for example, support to special education, technology training, arts education, etc. The school is at the center of the design. It is the place wherein preservice education, inservice education, research on practice, and the specific local context come together to inform and enhance the learning of children and their teachers.

The design of TCOOL is premised on the idea of teaching as a “learning profession” (Dewey, 1904, 1977; Lieberman, 1992; Darling-Hammond and Sykes, 1999) so its framework and intended outcomes differ from other teacher education programs in a number of important ways:

• In-situ Learning. It situates teacher education inside public schools and inside the classroom with current teachers working in collaboration with colleagues in colleges and universities, including faculty and professional staff. Like doctors in hospitals, preservice teachers are in the schools daily over a period of one to two school years working alongside and in concert with experienced teachers—far more time and focus than is normally required. In these ways, it is intended to eliminate the university-school divide that has so many new teachers feeling that their courses do not relate to their school placements. As well, it is intended to help teacher educators shape their programs in ways that resonate with the needs of the schools so as to support professional learning and inquiry with and among both preservice and experienced teachers (Brown, 1992; Cobb et al., 2009). Hence, new teachers' experience of learning to teach resides in the school as a laboratory for learning and it is hoped that, like new doctors, they will move into their first years of teaching knowing the breadth and depth of life in schools and classrooms and understanding and relying on research-informed practice (Lunenberg and Korthagen, 2009; Tal, 2019).

• Career-Long Focus. It changes the focus of teacher education from a narrow preservice activity to encompassing the career-long process of professional learning that is essential to supporting high-quality teaching over time and to preventing teacher burn-out. It recognizes both teacher induction AND teachers' long-term growth and professional satisfaction as an essential part of the work of the school (Little and McLaughlin, 1993; Putnam and Borko, 2000; Borko, 2004; Ulvik et al., 2017). It positions both pre-service and experienced teachers' engagement in research as a core professional value (Lieberman, 1992, 1994; Cochran-Smith and Lytle, 1999, 2009; Cobb et al., 2009) as well, it supports teacher educators' study of and refinement of their practice (Loughran, 2014; LaBoskey and Richert, 2015).

• Real-time, Continual Feedback. It is focused on actual day-to-day teaching—the single most important element in student learning (Hawley and Valli, 1999). In most teacher education programs, preservice students spend only a few weeks in classrooms as student teachers and the oversight of their work is generally episodic at best. Here, students are not only immersed in the schools over a period of 2 years, their teacher educators are also there regularly supporting them there and providing a model of collaborative engagement with school faculty (Rust et al., 2019).

• Iterative Learning Model. It supports an iterative process in which teachers inside the school study their practice and continually adjust it to meet the needs of their students with research assistance from their university/college-based partners. In this way, it enables both new and experienced teachers to bring theory and research into practice (Fish, 1980; Brown, 1992; Rust and Meyers, 2006; Cobb et al., 2009; Cochran-Smith and Lytle, 2009; Rust, 2009).

• Sustained Collaboration. It offers a level of sustained collaboration between urban public schools and their university/college partners, thereby fostering a long-term model of lifelong professional development that is intended to be highly enriching to current classroom teachers as well as to the research and policy communities (Anderson and Herr, 1999; Cobb et al., 2003b, 2009; Rust and Meyers, 2006; Rust, 2009).

And for High Poverty Urban Schools in particular:

• Teacher Retention. It will result in the retention of high-quality teachers in schools serving children of poverty.

As a partnership between higher education and public schools, TCOOL is intended to begin within a single school and expand over a 10-year period to include a network of schools (elementary, middle, and secondary) in the same geographic area that will function as research-informed communities of practice (Wenger, 1998; Wenger and Snyder, 2000). Within each school, the same collaborative elements will be in place: Each begins with a strong principal and teachers in a high poverty school choosing to collaborate with university-based preservice teacher education to make the school the educational analog of a teaching hospital. That is, each school will operate simultaneously as a site for coursework and fieldwork for student teachers and as the locus of professional learning for experienced teachers. The process of moving each school to becoming an inquiry-oriented site in which school and university collaborate in support of powerful professional learning is the prime intervention that is TCOOL. Hence, within each school, the project is designed to engage teachers in practitioner research that supports reflection on and refinement of practice.

When the model is expanded beyond a single school to a network of pre-k-12 schools in partnership with higher education and within a specific geographic area, it has the potential to become a dynamic and sustainable professional learning community focused on advancing student learning and achievement in high-needs urban schools. Implicit here is the idea that as the schools that are embraced in the TCOOL project are better aligned with one another and with their higher ed partner around professional learning, the community embraces “its” schools and university as “of the neighborhood” and will view them as assets to the community. Such networks of truly committed and engaged educators, students, and parents can foster a powerful conversation beyond the immediate area about what is being learned locally to support students' academic growth and, at the same time, contribute to the larger conversation about how to advance public education in high poverty communities nationally (DuFour et al., 2005).

Studying the Pilot of the TCOOL Design Experiment

Cobb et al. (2003a) contend that design experiments have “five crosscutting features” (9–11):

1. Their purpose is the development of a class of theories about both the process of learning and the means that are designed to support that learning.

2. The nature of the methodology is highly interventionist.

3. Design experiments always have two faces: prospective and reflective.

4. Design experiments are iterative—featuring cycles of invention and revision.

5. Design experiments tend to emphasize an intermediate theoretical scope (rather than grand theories of learning) that is located between a narrow account of a specific system (e.g., a particular school district a particular classroom) and a broad account that does not orient design to particular contingencies. Thus, they speak directly to the problems that practitioners address in the course of their work.

6. Design experiments are “conducted to develop theories, not merely to empirically tune ‘what works’” (Cobb et al., 2003a, 9). They do not produce statistical evidence or hard data about what has worked. Rather, they describe “attempts to support arguments constructed around the results of active innovation and intervention in classrooms” (Kelly, 2003, 3) and schools so, in their very format, or what Kelly (2003) describes as their “grammar,” is and is intended as generative and transformative. They get at the complexity of schools and classrooms.

Measuring the outcomes is messy work. As Brown (1992) wrote, “Components are rarely isolatable, the whole really is more than the sum of its parts. The learning effects are not even simple interactions but highly interdependent outcomes of a complex social and cognitive intervention” (166). To get at the overall and longterm impact, Brown (1992), Cobb et al. (2003a), The Design-Based Research Collective (2003), Engeström and Sannino (2010)—all recommend “thick descriptive datasets (and), systematic analysis of data” over time. Research tools include “ongoing records of the design process” (Cobb et al., 2003a)—data “on both learning and the means by which that learning was generated and supported” (12). As described by Brown (1992), Cobb et al. (2003a), and Engeström and Sannino (2010), these can include, for the overall management of the design experiment, agendas, and notes from all meetings of leaders and participants, interviews and surveys. For the conduct of the design experiment in classrooms: observational notes, student work, “patterns of social interaction; inscriptions, notations, and other tools; and responses to interviews, tests, or other forms of assessment” (Cobb et al., 2003a) as well as video and audio records. All are stored electronically for review not only by the research team to describe their learning and dissemination but for the field as a whole for growing knowledge about learning, teaching, and innovation.

The data gathered to guide the daily work of a design experiment are in many ways the same as those suggested for looking at the extent to which the process of invention and innovation brings the effort closer to the goal. The data capture those multiple small shifts that enable researchers, teachers, and administrators to know what seems to be working in the moment as well as to be able to step back, reflect, and, with an eye toward the grand goal, calibrate next steps. Like Wiggins and McTighe (2005) backward design, the research process requires a simultaneous embrace of the grand goal –what they describe as “big ideas” and “enduring understandings”—and attention to steps needed to move closer to those ideas and understandings that learners can carry with them and deepen over a lifetime. The backward design process is accomplished with an eye to the big ideas through planning as formative assessment. Each step relates to the question, “how do I know what my students are learning?”—a question of formative assessment that invites multiple forms of assessment so that learner and teacher can move beyond simple rote, short term assessments to high level, thoughtful assessments that engage learners in the pursuit of deep understanding. In this process, teachers themselves become researchers using the everyday tools of classroom assessment to guide them: observation notes, samples of student work, simple entrance and exit tickets, conversations with students, their own journals, anecdotal notes, running records for reading, photographs, video, and audio recordings. As described by the Design Research Collaborative in the 2003 special issue of Educational Researcher, “Such collaboration means that goals and design constraints are drawn from the local context as well as the researcher's agenda” (6) and often results in shifts in the design that can help to “refine the key components of an intervention” (6).

Method

In studying the pilot phase of TCOOL, we have drawn on similar methods using the data as formative to enable in-the-moment modifications of the project—essentially, this was a rapid-prototyping approach (Bossot, 2002; Ihrig and MacMillan, 2015): For the school, the data were drawn from weekly logs of lunchtime conversations kept by the project manager/mentor and shared online with the teachers, principal, and project director; e-mail notes between the project manager/mentor and project director; agendas and notes from monthly meetings run by the project director and project mentor with the teachers as well as from the two summer institutes; notes and videos from the teachers' presentations of their research in December and June each year; the teachers' research presentations; interviews conducted by the mentor; and feedback surveys given at the end of each semester. For the college, data are drawn from notes of meetings between the project director and the dean, department chairs, and college faculty and mentors; email with college mentors; notes from the project mentor's meetings with student teachers, classroom teachers, and the college mentor.

To give a sense of the process of the project, I have used Smith and Keith (1971) framework of event analysis, wherein the analysis of an innovation effort is developed by focusing on key events (and the activities that surround them) that occur sequentially over the span of the project. The material for this narrative is drawn from the data described above. Here, I have used the framework as a timeline documenting summer and semester activities during the 2 years of the TCOOL pilot and begin each phase with a description of what was going on in the school as well as a description of college-related activities. As a design experiment, the attention given here is to the unfolding narrative as a means of understanding what it takes to enable genuine partnership between a school and university. Hence, the narrative is not about proving what works. Rather, it is about tracing key elements of the TCOOL effort to enable theory building. The data enables the telling of the story of developing the design experiment.

Context

Drawing on her experience of having shaped urban-focused teacher education programs in New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia as well as studying international teacher education, specifically programs in Finland (Salberg, 2011) and Norway (Ulvik et al., 2017) where entry to teaching has the same cachet as entry to medicine does in this country, Rust conceptualized and articulated the general framework of TCOOL. In the Spring of 2016, she approached a major foundation that was shifting its focus toward teacher education. As a result of this initial conversation, she was introduced to the Deputy Chancellor of New York City Schools who felt the TCOOL model held great promise. He urged Rust to reach out to an experienced principal of an early childhood and elementary school serving children aged 3−10 (5th grade) in Brownsville in Brooklyn. The principal immediately saw the potential of the TCOOL collaboration to advance her school's teaching and learning needs. At the same time, Rust recruited and brought together a group of academics from local New York City institutions (NYU, CUNY Early Childhood Professional Development Institute, & Brooklyn College- CUNY) to collaborate with the school administration on a pilot vision and design.

The School

Riverdale Avenue Community School (PreK-Grade 5) is a prime example of a setting where the TCOOL strategy could make a real difference. An analysis of the official student demographics of its 357 students provides evidence of the high levels of poverty in this community: 93% of the students are eligible for free lunch; 28% have been identified with having learning distinctions; 8% are English Language Learners; and a shocking 27% are homeless or living in temporary housing.

Most of the teachers have master's degrees and from 5 to 30 years of teaching experience, making them potentially strong participants in developing a professional learning community. Many come from Brownsville or similar communities. Several had worked with the principal in her prior teaching setting.

Participants

Over the course of the pilot, the key participants remained the same. Throughout, the Project Director, Frances Rust, worked with both the school and the college. In the school, the key participants were the School Principal and the Project Manager/Mentor who entered the project in the Fall of 2017. In the University, the Dean was central.

Other school-based participants were lead teachers (1 each year) who met weekly with the principal and project manager/mentor and those teachers who opted to participate in monthly meetings with the project manager/mentor and me. Though the number changed yearly, the group of participants averaged 12–15. In the monthly meetings, we focused on their developing the skills of teacher action research. These meetings were supplemented and supported by weekly small group meetings with the Project Mentor. Two different university-based mentors worked with student teachers -one at the end of Year 1 the other at the beginning of Year 2. In the Spring of year 1 a group of 4 college students engaged in the initial stages of field work as participant observers came to the school and worked in 2nd, 3rd, and 4th grade classrooms. In the fall of year two, there were 2 student teachers working in 1st and 2nd grade classrooms.

Funding

Funding is always a concern in new project development—likely greater with this project because it did not operate under the aegis of a major university grant and the initial foundation interest did not hold. Hence, funding was a constant concern for the project director over the entire period of the pilot. As the project got underway and progressed, she was raising funds through private donations designated for the project through gifts to NYU-Metro Center. Between January 2017 and January 2019, $200,000 was raised—a sufficient sum to cover the major costs of the project related to personnel: an initial literacy-based enrichment program, salaries for the mentors, stipends of $1000 per semester for each of the 12–15 participating teachers as well as a small stipend each semester for a lead teacher/coordinator and for the principal, per diem stipends for teachers participating in the summer institutes, and a one-time only stipend to the student teacher supervisor from Brooklyn College. All other items anticipated in the project budget like additional school-based mentors, fellowships for student teachers that would enable them to be present weekly in the school for all of their field work during the 2 years of their education coursework, travel to conferences, equipment, graduate student engagement with the assessment process, etc. were put on hold pending a major grant. Since January 2019 when funds through donations to NYU for the TCOOL project were exhausted, the principal has enabled in-school participation in the project to continue by garnering resources to pay for the mentor to continue her work with the teachers through bi-weekly visits. As well, she has maintained the schedule that enables the teachers to meet with the mentor and so to continue their research.

Piloting the TCOOL Design Experiment

Getting Started

At the end of August of 2016 just before school opened, the Principal set up a meeting with the teachers at the school during which she introduced me and enabled me to describe the project and to enlist their participation in TCOOL. We were too late in the academic year and did not have enough funds to enable our preservice teacher education partner, Brooklyn College, to shift already determined student teaching placements to the school, so the project began with Rust spending at least a day a week in the school getting to know the school and teachers.

In January 2017, with the first infusion of funds, our first effort at collaboration between school and university began with the launch of a literacy-based enrichment program suggested by NYU Metro Center. The program, designed for middle and high school, supports children's creation and performance of poetry. While the 13 of the school's participating teachers attended TCOOL workshops with Rust and a NYU graduate student mentor during the school day, their regular classes received instruction by teachers from the enrichment program. In weeks where there were no professional learning sessions, two instructional coaches, Rust and the NYU graduate student mentor worked with the fifteen participating teachers to support individual teacher's efforts to engage their students in rich discussion and critical thinking about their learning.

This initial iteration did not work well. It occurred once a month, the participating college faculty shifted unpredictably so teachers did not get to know them, and the substitutes who came from te arts education program were not accustomed to working with elementary school children. The problems encountered led TCOOL's partners to reach a number of critical decisions:

1) First among these was to abandon the idea of “preparing” a school for working collaboratively with student teachers and simply dive right in. It was clear that the group of experienced teachers at the school, all with master's degrees, were eager to move away from the didactic workshop model of professional development toward one that would enable genuine analysis of real teaching in familiar classroom settings.

2) Second, feedback from the school's teachers enabled us to revise our understanding of a mentor's role from instructional support around a specific instructional intervention to instructional support that enables individual inquiry and facilitates collaboration among teachers around critical aspects of their work. We found teachers eager to talk about: teaching specific concepts, how routines are handled in their classrooms, how to develop support for a particular child, etc.

3) Third, we decided that engaging with teacher education writ large, that is, as the preparation and continual learning of teachers as the focus of our work together should always be at the core of our conversation when we enter into a new school. We originally thought to focus instructional interventions on areas such as Literacy and English as a New Language (ENL). We now understood that although literacy and language are critical, these issues can be addressed more fruitfully in the conversations around practice that would likely come with the inclusion of a student teaching program as core to the activity of the school itself.

4) Fourth, we recognized the need for an assessment framework that evaluates the approach of engaging partners at the school and university level in practitioner research to inform practice rather than statistical data (e.g., standardized test scores) which cannot get at the rich complexity of the individual setting. We had learned that in order for a new model of teacher education to be clearly articulated, the assessment framework should include links to classroom practice, accountability among the partners, and evaluation of implementation.

Developing a Plan of Action

With adequate new funding, we began in July of 2017 to develop a plan for TCOOL that was as close to enacting the vision of TCOOL as our thinking could approximate. Drawing on experience the prior Spring and recommendations from one of our higher education partners and with new funding, the principal and I together sought out and hired an experienced mentor who would be in the school 2 days each week to meet with teachers in small groups to support their action research, would liaise with the Brooklyn College student teacher supervisor, and would meet regularly with the principal and me, the project director, to help us gain insight about the daily operations of the program. In essence, she would function as the project manager and school-based mentor.

During the summer, the principal, project mentor, and director developed a general plan of operations:

• Teacher teams of 3–5 teachers would meet weekly with the project mentor around their research. In keeping with Rust's insistence on professional learning being part of the school day (hence understood as part of the teachers' work), these meetings were developed as lunch conversations focused around the teachers' action research. To facilitate, the principal shaped a schedule that enabled teachers to meet weekly at the same times and with the same small group of 3–5 colleagues. We also determined that teachers who opted to participate would receive $1,000 per semester. This acknowledged their participation in the lunch meetings, monthly action-research meetings with the project manager/mentor and me, and their development of an end of year presentation of their work.

• In the spring, these teams would be expanded to include student teachers.

• The project director would reach out to the college to develop a plan for integrating student teachers beginning in the Spring of 2018.

• Regular meetings of all the participating teachers, the project director, the project manager/mentor, and university mentor/supervisors would be held monthly. These meetings were intended to support the development of the teachers' research skills, to support on-going assessment, as well as to facilitate collaboration with the college.

• Day-to-day oversight of the collaboration between the school and the college would be coordinated by the project manager/mentor.

Living Into the Plan

Here, we describe the general conduct of the TCOOL project as it related to the school and the college. Our focus is on the effort to develop a collaborative atmosphere in the school and a genuine partnership between the school and the college—both sites being essential to the preparation of new teachers and professional learning of the 13–15 participating teachers who would be the preservice teachers' colleagues and classroom mentors in the school.

Beginning-Summer Into Fall, 2017

At the start of a 3-day summer institute mid-August of 2017, the project manager/mentor was introduced to the teachers. Together, she and I worked with 20 interested teachers and classroom assistants to introduce practitioner research and mentoring. By the end of August when teachers were back and readying for the year ahead, the principal sent out a request re participation in TCOOL. She provided an incentive by alerting teachers that their action research projects for TCOOL could also count for a district-wide initiative on teacher research. In response, 13 teachers (one of whom was new to teaching) indicated to the principal a willingness participate in the TCOOL project. This meant a commitment to a weekly meeting with the project manager/mentor and a small group of colleagues, monthly after school workshops with the project manager/mentor and project director, willingness to host a student teacher, the eventual presentation of their work to colleagues, and eventual write up of their research.

With this signal from the teachers, the principal began to shape a schedule that would enable teachers to come together in cohort groups of 3–5 at lunch time. Though it sounds simple on the surface, developing a schedule that will work week after week requires attention to a myriad details: coverage of classes by licensed staff; shifting “specials” such as art, music, computer; freeing space for the meetings; commitments from those not participating to honor the effort of their colleagues to engage in the project. Additionally, the principal had to look ahead on the calendar to position the after-school monthly meetings, and she had to set a regular meeting time with the project manager/mentor. While not an immediate concern in September, the principal and mentor were also aware of the need to make time to prepare within the school and with Brooklyn College for the entrance of student teachers in the spring.

Beginning in mid-September and throughout the Fall, the weekly lunch meetings of teachers and project-mentor got underway as did the monthly after school workshops. Lunch in this early childhood/elementary school began at 10:30 and was complete at 12:20 pm with classes rotating into the cafeteria in half hour slots followed by playground time so the small group meetings were scheduled for 50 min but, taking into account the need for participants to get there and get settled and then for teachers to leave for their classes, they turned out on a good day to be 45 min meetings. The project director and project manager/mentor were in weekly communication regarding these meetings in person, on the phone, and through email. The project manager/mentor developed notes from each lunch conversation that she then shared with the teachers, the principal, and the project director, and she and the project director met weekly to review these looking for trends to inform our planning and also as evidence of what was working. Prior to an end-of semester celebration in December with the TCOOL teachers wherein the teachers made 3-min presentations to one another about what they were doing with and learning from their research, the mentor collated notes from each teacher's lunch conversations so that each had that data at hand as they began to prepare for their presentations at the end of the school year. She also provided each teacher with a set of questions to guide their writing.

Though she could not attend the summer institute held at the school with the teachers, the dean of Brooklyn College was in conversation with the project director regarding plans for the college's participation in the project. The dean and the principal were able to meet at the school at the end of November to solidify plans for student teachers' field experience at the school beginning in January. It was decided that an initial group of student teachers would be 10 students participating in an elementary literacy course. Their college-based mentor would establish their schedules with the school through the principal's office, would visit weekly and would communicate on a regular basis with the project mentor.

Meanwhile, in the school, the principal, project mentor, and lead teachers were developing a “curriculum” for the teachers who would host student teachers in their classrooms. The principal wanted to be sure that she and the teachers who would host student teachers were aware of how to provide a supportive atmosphere for the new teachers. As this planning went forward, there was no one on the college side with whom they were able to communicate until the November meeting with the dean and later with the college-mentor once the Spring semester began.

Winter Into Spring, 2018

While school opened on January 3 and the weekly lunch meetings picked up again, student teachers did not come to the school until the second week of February. This was completely unexpected by the school team but seemed the normal operation of the teacher education program as classes did not commence until late January and field placements were apparently often scrambled over the holidays and required resetting. When four instead of the ten student teachers anticipated did come, each had a different schedule of times and days thus confusing classroom placements and requiring last minute shifts among teachers. Only one was prepared to take the time to participate in grade-level meetings and to join in her classroom teacher's TCOOL group. The college-mentor was unable to arrange her schedule to regularly be in the school on the same days as the project manager/mentor or when the project manager/mentor was not in her small group meetings so her liaison with the school became one of the lead teachers who had planned with the principal and the mentor; that conversation was essentially a check on attendance. Further complicating the issue was the fact that, irrespective of whether the cooperating teachers were participants in the TCOOL project, the coaching for mentoring that the principal, project manager/mentor, and planning team had wanted to provide was set to happen at the end of the school day, and it became too cumbersome for all to have yet another meeting.

As the Spring term progressed, the student teachers completed their field experience hours. By the time of the school's spring break at the end of March, they had stopped coming to the school. After Spring break the pressures of school district assessments would have made their presence difficult since they had not been there long enough to know the curriculum of their respective classrooms. However, the issue of how to work with the college's teacher education programs assumed a major place in our conversations at the school and with the dean who was able to relay to us difficulties that the students and mentors felt they had experienced at the school.

It was time for a reset regarding the student teacher side of TCOOL. With the encouragement of the dean, the project director visited the college in the late Spring, this time focusing on a 2-year graduate program of special education wherein the faculty could countenance placing students in the school for the entire four semesters of their program. As we developed a plan for placing two graduate students in the coming fall, we identified a college faculty member who was willing and able to be in the school a day a week in dialogue with the students, cooperating teachers, and project mentor. The project director carried the plan forward to the school and a conversation focused on the fall semester began.

At the beginning of June, the teachers participating in TCOOL were ready to present their action research projects in a whole school event. As she had done in December, the project manager/mentor created separate records for each of the teachers of their lunch conversations throughout the spring. By then, she had also been invited into many of their classrooms as a participant observer, and she had developed strong relationships with the teacher leaders to the extent that one elected to begin a research project on her own with the project manager/mentor's guidance.

The June event was a morning event attended by all of the teachers in the school and one of the major funders of the project who brought along a guest, a former principal from the Brownsville area. It was remarkable in that the responses to the TCOOL teachers' presentations by colleagues and particularly their questions explored the TCOOL teachers' thinking about their instructional shifts over the year as well as the action research process. Following the event, the project provided lunch for the TCOOL participants and for those who had worked with student teachers. The mentor and project director used this time as an opportunity for a focus group conversation on the project.

As the project manager/mentor and I reviewed the year of weekly meetings among teachers and with the principal, we were able to discern some lessons that would guide our planning for the next year within the school and relative to the college. Initially, the meetings were structured as “quick shares” wherein teachers would talk about what they were doing around their action research question. In November, we had remarked to one another that each of the cohort groups seemed to be developing their own distinct conversation. They seemed to have developed such trust with the project manager/mentor and one another that they were able to bring in issues from their classrooms for which they needed extra support and working these through together became part of their developing relationship. As the year went on teachers often came prepared with questions to ask the group, data to share, videos to watch together and next steps to think about together.

Summer Into Fall, 2018

We began the summer with several major planning sessions focused on (1) development of a website at NYU Metro Center wherein we could describe the project and sketches of the teachers' research projects (2) development of a full-scale assessment of the project thus far; and (3) developing a more robust relationship with Brooklyn College around student teaching. Once again, we planned for a 2-day summer institute early in August and hoped that those who had worked with us over the first year would continue. They did and new participants joined. The summer sessions were less of an introduction than the prior year as many of the participants had either participated in TCOOL or had been at the teachers' presentations.

In the fall, we retained 9 teachers from the prior year and gained 8 new participants. Additionally, the project manager/mentor was now working individually on action research with both the lower and upper elementary team leaders and requests for her to visit classrooms had come from sixteen teachers—not all participants in TCOOL.

While we retained the weekly lunch meetings and the monthly workshops, there were striking differences. We saw that the TCOOL teachers who had been with us during the first year were now really “into” their action research. They began to request specific foci for the monthly sessions. For example, they wanted to know more about a variety of note-taking strategies and when appropriate to use them. As well, they requested that writing time be planned into the meetings. The project manager/mentor and project director moved to shaping the 90-min monthly workshops; within each there was a short time for presentations and discussions of strategies, real time for writing, and time for a step-back reflection and look ahead.

As in December 2017, the TCOOL teachers came together for a celebration of their work. This time, the project manager/mentor videotaped and posted the videos to each of the participants and the project director made transcripts of the videos and shared these with the teachers to facilitate the their writeups later in the year.

Winter Into Spring, 2019

As the second semester began, we were set to move forward to into the spring when, early in January, we discovered that our funding was exhausted. At that moment when it looked as if the TCOOL project had come to an abrupt end, the principal and teachers opted to continue the lunch-time action research meetings and the principal stepped in with funding to continue the project mentor though not with the full 2-day presence that the mentor had provided.

Additionally, the principal and teachers opted to continuing with their commitment to engaging with student teachers. The school team had developed with the college mentor a framework of expectations for student teaching. Two master's students in special education came early in the new school year and their mentor was available when they were there. Difficulties arose, however, with one of the student teachers disagreeing with her cooperating teacher's instructional process. In part, this had to do with the state's mandated performance assessment that positions the student teacher as an active agent and decision-maker in the classroom. In this case, teaching to the test (the state's performance assessment) may have come too soon for trust and understanding between student teacher and cooperating teacher to have developed. While major efforts were made to ameliorate the situation, working with student teachers still seemed adjunct to the real work of the school.

In June, the TCOOL teachers once again presented to one another and their colleagues though this time their presentations were part of day of small group workshops and planning sessions developed by teachers across the school so the audience was not as robust as it had been the previous year. However, in comparison to the prior year, the teachers seemed more confident in their presentations and much more willing than in the past to bring their presentations into print—something we are about to do!

In their presentations, they made claims about their own growth as professionals:

• One teacher traced changes in her teaching to her initial focus on her writing instruction. She claimed that as she kept deepening of her understanding of how to better support her students, she could transfer her learnings to her math instruction, changing the way she teaches math and increasing student learning. She also began to talk more deeply about her practice with other teachers and to strategize with them. A surprise to us is that she has continued to engage with the project manager/mentor even now as she prepares her action research for publication.

• Two teachers who team teach did their first project separately—each focusing on a different child. In the second year, they chose to do an action research project together to change the way they taught writing. The focused on one strategy—fish bowl- to work on with their children. They began to video tape on their own so as to reflect upon, inform, and improve their instruction.

• Another teacher completely changed her instruction by looking at data from each child to inform her next steps in the teaching of reading. In her second year, she used this isame approach in her new role as an ESL teacher and is continuing with it. She, too, is preparing her study for publication.

• One of the lead teachers came into the project initially as part of a group but arranged for one-on-one meetings with the project manager/mentor. She ascribes her move into a genuine leadership role in the school to having had supportive opportunity to reflect on her interactions with other teachers so to improve her practice. She has gone from being a leader in the school to Assistant Principal and then Principal.

Though improvement in student learning was not an intended outcome of the TCOOL project at this early stage, the claims that each of these teachers made about improvement in their teaching were buttressed by the learning gains that they documented among their students.

Once we are able to secure the appropriate funding, the college is committed to trying again. The issue of funding is critical here because enabling preservice students to spend 2 years in the school as fellows requires funding for fellowships that will enable them to engage full-time with the school and with their coursework instead of having to additionally carry part-time jobs. To have a college-based mentor in the school also requires funding to secure course release.

Making Sense

Implied in the design of TCOOL (see Figure 1) is a steady state in schools and universities that suggests, though it does not specify, a set of moves among each of the key participants that will gradually move toward equilibrium. We now see that while this vision of a changed relationship between schools and universities may, in the long run, be apt in that it serves as an image to define our grand goal, it cannot encapsulate the complexities involved in this change process within and across each of the participating organizations (Brown, 1992; Cobb et al., 2003a). So, the telling of this story of the pilot and the act of reflecting on each step and drawing lessons to shape the next become critical to the effort of learning how to move closer to the goal. In other words, this is not a not a study that promises to define which tools at hand work best, though, traditional tools, such as field experience and inquiry-oriented practices, are definitely essential here. Nor is it aimed at defining specific outcomes. Rather, it is a study of learning about what the process of moving toward the goal of radically reshaping teacher education entails. It is about theory development (Cobb et al., 2003a). Our analysis then focuses on what we have learned that can carry us forward.

Lesson One: Boundary Crossing

Merging radically different systems that have traditionally existed in parallel universes (which describes the traditional school university relationship in teacher education) requires genuine boundary crossing. Cobb et al. (2003a) suggest that, “design experiments ideally result in greater understanding of a learning ecology—a complex system involving multiple elements of different types and levels—by designing its elements and by anticipating how these elements function together to support learning” (9). In other words, design experiments get at the complexity of educational settings. With the TCOOL pilot, this showed in a number of ways.

The first had to do with the design of TCOOL wherein we planned for collaboration between the college and the school earmarking the long-term presence of student teachers in the school as the essential “tell.” In achieving that collaboration, we planned for including student teachers in the school as new members in a vibrant learning community wherein the conversation of practice was alive and well-among the teachers and was increasingly shared in by the teacher education community. The learning ecology that we sought in those plans implicitly recognized the fact of the borders as systemic organizational differences between the school and the university. It is clear to us now that explicit recognition of boundaries is essential and that it should enable early and ongoing negotiation and planning.

In the TCOOL pilot how time is used and for what—how activity schedules are made—was and is an essential issue of boundary crossing for it is with the use of time and the organization of the calendar that the mores of an organization are often most clear. Whether the TCOOL concept will always work within the cyclical pattern of the school/academic year as it did during the pilot is unclear. It makes sense, for example, to use the summer for reflection-driven planning that positions future activity relative to set patterns regarding time and culture but this should involve discussion among all of the partners. For example, if summer is too late for planning for student teacher entry into the school in the fall, then a critical next step is developing the capacity to negotiate the barriers raised by the different organizational calendars to give time to the placement process. In TCOOL, this was done by the school and university the following year after the Spring of 2018 experience when the student teachers essentially began their field work at the school almost 5 weeks after school had opened. But the boundary issues around time in each organization are far more complex.

Time issues were obvious in the lack of synchrony between the student teachers' and college-based-mentor's schedules with those of the teachers and project manager/mentor. The efforts made by the dean and college faculty to resolve these initial discrepancies, though they may have seemed minimal or a “little too late” at the time, required substantial accommodation on the part of the college that was most obvious in their effort to plan with the school for the spring of 2019 and the designation of a new set of faculty and a new college-based-mentor.

In the school, the creation of a schedule to accommodate the weekly lunch meetings with the project manager/mentor was significant in that it required adjustments across the school to bring this professional development activity into the daily life of the teachers. As well, there were the often difficult accommodations that teachers who took on student teachers had to make as a novice entered their sphere of influence. And then there were the teachers who participated in the lunch conversation who, though they may have worked in the same building with one another and even on the same grade level or as a team, still had to overcome their tendency toward privatism (Lortie, 1975) in order to be able to develop their small learning communities.

Using the lens of expansive learning, we were also able to expand our own horizon on the time and participation needed to develop the model. As Sannino et al. (2016) note, “rather than aiming at transferable and scalable solutions, formative interventions (like this one) aim at generative solutions developing over lengthy periods of time both in the researched activities and in the research community” (599). In part, the time needed is about developing trust.

Lesson Two: Relational Trust

Unlike so many interventions in schools and experiments within education programs, TCOOL had/has no end point. Rather, it is a constantly negotiated and renegotiated set of activities that pertain at once to the moment of their happening and at the same time serve to shape action(s) beyond that moment; and, while in the moment, the vision of the grand goal may be forgotten, it can be drawn back to awareness in the interactions of the participants as they ask, “Why are we doing this?” Pioneering and staying with TCOOL even as the funds ran out, even as we could not bring in all the elements that the grand design suggests should be there—this requires what Bryk et al. (2010) describe as “relational trust,” that is, trust rooted in social respect and deeply influenced by a person's perception of another's integrity. Bryk describes this as the strongest indicator of school reform. Trust is what creates investment in an initiative, what gets stakeholders to buy-in to a change and do the work necessary to support it on the ground and in the moment. We saw such trust exhibited throughout the TCOOL pilot from the principal in her unwavering support, from the project manager/mentor who was faithful in her commitment of time and willingness to share her skill and knowledge and from the teachers who faithfully shared with one another in the weekly and monthly meetings. We saw it with the Dean who has continued her efforts to support the project and stands ready to help us move forward.

With TCOOL, we have learned, too, that trust is essential to a vibrant, focused learning community and it takes time to develop that trust. In our experience, a year enables beginning well. It gives the time needed to try to learn one another's language and meaning, and it enables building a reservoir of shared experiences as well as shared language and understandings. We saw this particularly in the action research groups where we saw a shift toward increased reflexivity among the teachers. We could not have forecast at the beginning of this work that the teachers would be asking for additional research tools in the Spring of 2018, or that they would willingly present their work to their peers and write about it. While we credit these moves to the conversation cycle initiated by the project mentor and used in the weekly cohort groups and to her development of a research guide that supported the teachers' development of their oral and written presentations, we understand that this happened because trust had been nurtured and developed. Continuing together over time requires trust, too, in order to figure out how to move through the institutional and organizational barriers that are inevitable.

Lesson 3: Resources

While the grand plan of TCOOL is that the partnership is genuinely shared by the school, university, and community, our analysis of the pilot phase makes it very clear that such partnership requires funding—initially to enable the conversation of practice to emerge and become situated and not just in the school. It is needed to enable the circle of participants in the school and the college to widen and for the activities of the project to expand.

At the school, without another school-based mentor or two or making the project manager/mentor's job full-time, we could not grow beyond 16 teachers participating. Because it would have required extra time and the appointment of a someone to liaise with the college supervisor, we could not do the preparation of teachers to serve as mentors to student teachers. We could not afford planning retreats that could bring school and university participants together. Hence, the major activities of the TCOOL pilot resided in the school and pertained to the embrace of practitioner research within small learning communities during the school day.

In the university, funding is needed to support fellowships for students to be able to do the whole of their field work (4 semesters) in the school thereby enabling them, perhaps, to complete their degrees in 4 or 5 years rather than the current average of 7 years because of their need to juggle work with school. It was lack of funding that precluded our effort to develop a committed group of student teachers. Funding is needed to facilitate college faculty engagement with the school. For example, we discussed with the university the possibility of bringing a course into the school so that student teachers and teachers in the school could participate in it. Similarly, we felt it would have helped student teachers to have their supervisor in the school with them each week.

Summary

It is clear, that the complexity of the school and universities as workplaces situated themselves in complex systems makes it almost impossible for leaders to track change day by day or even month by month. There must be dedicated times when participants come together, perhaps, in summer, wherein we take stock of what has happened and draw from that to shape next steps. This coming together is particularly important in terms of our commitment to radically reshape teacher education so as to prepare and support teachers to optimize the learning and achievement of children of poverty.

Our work together suggests flexibility and fluidity: Flexibility with regard to time; fluidity with regard to having strategic participants who have the time, experience, capacity, and trust to cross boundaries both within and outside of the partner organizations.

Whether the routines that were developed in the pilot, especially those like the lunch meetings that invited collaboration around practice and saw an expansion of teachers' capacities to adapt instruction to meet students' needs (in one way or another, the primary focus of the teachers' research), will hold in the same form as we move forward we cannot know. However, based on the teachers' and principal's embrace of the arrangement, it seems likely that the commitment to situate professional learning as part of the school day has become a key facet of the TCOOL design and will hold as such as others enter the collaboration.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have presented a first iteration of the TCOOL project as an example of expansive learning. We have used the lenses of expansive learning theory (Engeström and Sannino, 2010; Engeström, 2016; Sannino et al., 2016) and design theory (Brown, 1992; Cobb et al., 2003a, 2009; The Design-Based Research Collective, 2003) to probe the opportunities for learning about teaching that TCOOL provides to practitioners in schools and universities. Though TCOOL is not per se an instructional intervention like those programs studied by Sannino et al. (2016) in their study of Change cases, by Cobb et al. (2003a) in their overview of design experiments, or by Cobb et al. (2009) with regard to design experiments in mathematics, we found that the lenses provided by both theories have given us a glimpse of the meaning of the “qualitative transformation of all components” that Engeström and Sannino (2010) describe. For us, expansive learning was and is manifest in the collective movement of teachers and administrators toward a shared inquiry-oriented practice (Cochran-Smith and Lytle, 2009) in which the conversation of practice grew within the school as more teachers and teacher leaders participated, and it occurred between the school and the university as efforts to integrate these distinct organizations has persisted and deepened. It has disrupted the notion of stasis in either organization though whether and how the movement toward the equity implied in the participatory teacher education model of TCOOL will resolve is unclear.

In a sense, the TCOOL pilot has given us some “proof of concept” in that, by casting light on problems AND progress over the short time of 2 years, it has helped us to discern paths for future action around shifting the relationship between schools and universities vis-à-vis teacher education. This is a story of trying to figure out what it takes to get a school and a university to work together. Here, design theory (Brown, 1992; Cobb et al., 2003a, 2009; The Design-Based Research Collective, 2003) and expansive learning theories (Engeström and Sannino, 2010; Engeström, 2016; Sannino et al., 2016) have been especially helpful to interpreting the change process implicit in this effort, for, as both theories make clear, the end state, the outcome of a real-life experiment like TCOOL can only be envisioned in terms of the general equilibrium desired. How one gets from here to there, while planned for in general terms, must be open to revision, redirection, and surprise. Otherwise, we end up at the place where we began.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

FR is the author of this manuscript which was informed by data developed through field notes, emails, surveys, interviews, and conversations with participants in the school and college.

Funding

The author declares that this research was funded completely by small private donations—all given in support of the TCOOL project.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge Principal, Meghan Dunn, and the Project Manager/Mentor, Sabrina Silverstein, whose steadfast support and collaboration made this beginning of the TCOOL project possible. The author also wishes to acknowledge the special attention given to the project by April Bedford, Dean of Brooklyn College, and Sherry Cleary, Executive Director of the New York Early Childhood Professional Development Institute, City University of New York (CUNY). Acknowledgment is also due for the participation and effort made by the participating teachers at the Riverdale Avenue Community School, the Elementary and Special Education faculties of Brooklyn College, and the members of the TCOOL advisory board who have given their time and advice to the project.

References

Anderson, G. L., and Herr, K. (1999). The new paradigm wars: is there room for rigorous practitioner knowledge in schools and universities? Educ. Res. 28, 15–21. doi: 10.3102/0013189X028005012

Bereiter, C., and Scardamalia, M. (1989). “Intentional learning as a goal for instruction,” in Knowing, learning, and instruction: Essays in honor of Robert Glaser, ed L. B. Resnick (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.), pp. 361–392.

Borko, H. (2004). Professional development and teacher learning: mapping the terrain Educ. Res. 33, 3–15. doi: 10.3102/0013189X033008003

Bossot, M. (2002). “The creation and sharing of knowledge,” in The Strategic Management of Intellectual Capital and Organizational Knowledge, eds C. W. Choo and N. Bontis (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 65–77.

Brown, A. L. (1992). Design experiments: theoretical and methodological challenges in creating complex interventions in classroom settings. J. Learn. Sci. 2, 141–178. doi: 10.1207/s15327809jls0202_2

Bryk, A. S., Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Luppescu, S., and Easton, J. Q. (2010). Organizing Schools for Improvement. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226078014.001.0001

Cobb, P., Confrey, J., diSessa, A., Lehrer, R., and Shauble, L. (2003a). Design experiments in educational research. Educ. Res. 32, 9–13. doi: 10.3102/0013189X032001009

Cobb, P., McClain, K., de Silva Lamberg, T., and Dean, C. (2003b). Situating teachers' instructional practices in the institutional setting of the school district. Educ. Res. 32, 13–24. doi: 10.3102/0013189X032006013

Cobb, P., Zhao, Q., and Dean, C. (2009). Conducting design experiments to support teachers' learning: a reflection from the field. J. Learn. Sci. 18, 165–199. doi: 10.1080/10508400902797933

Cochran-Smith, M., and Lytle, S. L. (1999). Relationships of knowledge and practice: teacher learning in communities. Rev. Res. Educ. 24, 249–305. doi: 10.2307/1167272

Cochran-Smith, M., and Lytle, S. L. (2009). Inquiry as Stance: Practitioner Research for the Next Generation. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Darling-Hammond, L., and Sykes, G. (Eds.). (1999). Teaching as the Learning Profession: Handbook of Policy and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Delpit, L. D. (1995). Other People's Children: Cultural Conflict in the Classroom. New York, NY: New Press.

Delpit, L. D. (ed.) (2012). “Chapter 4: warm demanders: the importance of teachers in the lives of children of poverty,” in Multiplication is for White People Raising Expectations for Other People's Children (New York, NY: New Press), 71–88.

Dewey, J. (1904, 1977). “The relation of theory to practice in education,” in John Dewey: The middle works, 1899-1924, Vol. 3 (1903-1906), ed J. A. Boydston (Carbondale and Edwardsville, IL: Southern Illinois University Press), 249–272.

DuFour, R., Eaker, R., and DuFour, R. (2005). “Recurring themes of professional learning communities and the assumptions they challenge,” in On Common Ground: The Power of Professional Learning Communities, eds R. Barthm, R. DuFour, R. D. Four, R. Eaker, B. Rason-Watkins, et al. (Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press), 7–29.

Engeström, Y. (2016). Studies in Expansive Learning. Learning What is Not Yet There. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y., and Sannino, A. (2010). Studies of expansive learning: foundations, findings and future challenges. Educ. Res. Rev. 5, 1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2009.12.002

Fish, S. (1980). Is There a Text in this Class? The Authority of Interpretive Communities. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hamilton, M. L., and Pinnegar, S. (2015). Considering the role of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices in transforming urban classrooms. Study. Teach. Educ. 11, 180–190. doi: 10.1080/17425964.2015.1045775

Hawley, W., and Valli, L. (1999). “The essentials of effective professional development: a new consensus,” in Teaching as the Learning Profession: Handbook of Policy and Practice eds L. Darling-Hammond and G. Sykes (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 127–150.

Ihrig, M., and MacMillan, L. (2015). Managing your mission-critical knowledge. Harv. Bus. Rev. 93, 80–87.

Ingersoll, R., May, H., and Collins, G. (2019). Recruitment, employment, retention and the minority teacher shortage. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 27. doi: 10.14507/epaa.27.3714

Ingersoll, R. M. (2001). Teacher turnover and teacher shortages: an organizational analysis. Am. Educ. Res. J. 38, 499–534. doi: 10.3102/00028312038003499

Ingersoll, R. M., Merrill, E., Stuckey, D., and Collins, G. (2018). Seven Trends: The Transformation of the Teaching Force – Updated October 2018. CPRE Research Reports. Available online at: https://repository.upenn.edu/cpre_researchreports/108

Kirkland, D. E. (2013). A Search Past Silence. The Literacy of Young Black Men. New York, NY: Teachers College.

LaBoskey, V. K., and Richert, A. E. (2015). Self-study as a means for urban yeachers to transform academics. Study. Teach. Educ. 11, 164–179. doi: 10.1080/17425964.2015.1045774

Ladson-Billings, G. (1994). The Dreamkeepers: Successful Teachers of African-American Children. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Lieberman, A. (1992). The meaning of scholarly activity and the building of community. Educ. Res. 21, 5–12. doi: 10.3102/0013189X021006005

Lieberman, A. (1994). “Problems and possibilities of institutionalizing teacher research,” in Teacher Research and Educational Reform, eds S. Hollingsworth and H. Socket (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press), 204–220.

Lieberman, A. (2011). Laureates speak can teachers really be leaders? Kappa Delta Pi Rec. 47, 16–18. doi: 10.1080/00228958.2011.10516717

Little, J. W., and McLaughlin, M. W., (Eds.). (1993). Teachers Work: Individuals, Colleagues, and Contexts. New York, NY: Teachers College.

Loughran, J. (2014). Professionally developing as a teacher educator. J. Teach. Educ. 65, 271–283. doi: 10.1177/0022487114533386

Lunenberg, M., and Korthagen, F. (2009). Experience, theory, and practical wisdom in teaching and teacher education. Teach. Teach. Theor. Prac. 15, 225–240. doi: 10.1080/13540600902875316

McCandliss, B. D., Kalchman, M., and Bryant, P. (2003). Design experiments and laboratory approaches to learning: steps toward collaborative exchange. Educ. Res. 48, 14–16. doi: 10.3102/0013189X032001014

Morel, R. P., Coburn, C., Catterson, A. K., and Higgs, J. (2019). The multiple meanings of scale: implications for researchers and practitioners. Educ. Res. 48, 369–377. doi: 10.3102/0013189X19860531

Putnam, R. T., and Borko, H. (2000). What do new views of knowledge and thinking have to say about research on teacher learning? Educ. Res. 29, 4–15. doi: 10.3102/0013189X029001004

Rust, F., and Meyers, E. (2006). The bright side: teacher research in the context of educational reform and policymaking. Teach. Teach. Theor. Prac. 12, 69–86. doi: 10.1080/13450600500365452

Rust, F., Pupik-Dean, C., Colket, L., and Jacobs, C. (2019). “E-Portfolios: a tool for assessing teacher inquiry as a bridge between theory and practice in teacher education,” in Paper Presented at the International Study Association on Teachers and Teaching (Sibiu, Romania).

Sannino, A., Engeström, Y., and Lemos, M. (2016). Formative interventions for expansive learning and transformative agency. J. Learn. Sci. 25, 599–633. doi: 10.1080/10508406.2016.1204547

Scardamalia, M., and Bereiter, C. (2006). “Knowledge building: theory, pedagogy, and technology,” in Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences, ed K. Sawyer (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 97–118. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511816833.008