94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

METHODS article

Front. Educ. , 04 June 2020

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 5 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.00053

This article is part of the Research Topic The Home Language Goes to School: Heritage Languages in Classroom Learning Environments View all 6 articles

In the context of adult second language teaching, heritage language speakers have been recognized as a special group of language learners, whose experience with their home language, as well as their motivations for (re)learning it, differ drastically from those of an average learner of a second language. Current heritage language pedagogical approaches focus primarily on the development of communicative (or functional) abilities of the heritage learners and on critical exploration of bilingual practices and identities. However, structural accuracy remains a persistent issue for heritage speakers, who do not always reach higher levels of proficiency in their heritage language (as measured by standard language proficiency tests). In this paper, we use the example of heritage Russian instruction in American college classrooms to argue for the critical role of form-focused instruction in teaching a heritage language, and in particular in bringing heritage learners to greater proficiency. The argument for the importance of form-focused instruction is based on the results of extensive linguistic research combined with insights from the currently available pedagogically oriented research. We formulate and discuss instructional methods that help educators (1) develop heritage learners’ attention to grammatical form, (2) foster heritage learners’ understanding of grammatical concepts, and (3) increase the learners’ metalinguistic awareness. Given consistent parallels across different heritage languages, the methodologies developed for Russian learners can apply to other heritage language classrooms as well, with adjustments based on the sociolinguistic context of particular heritage languages.

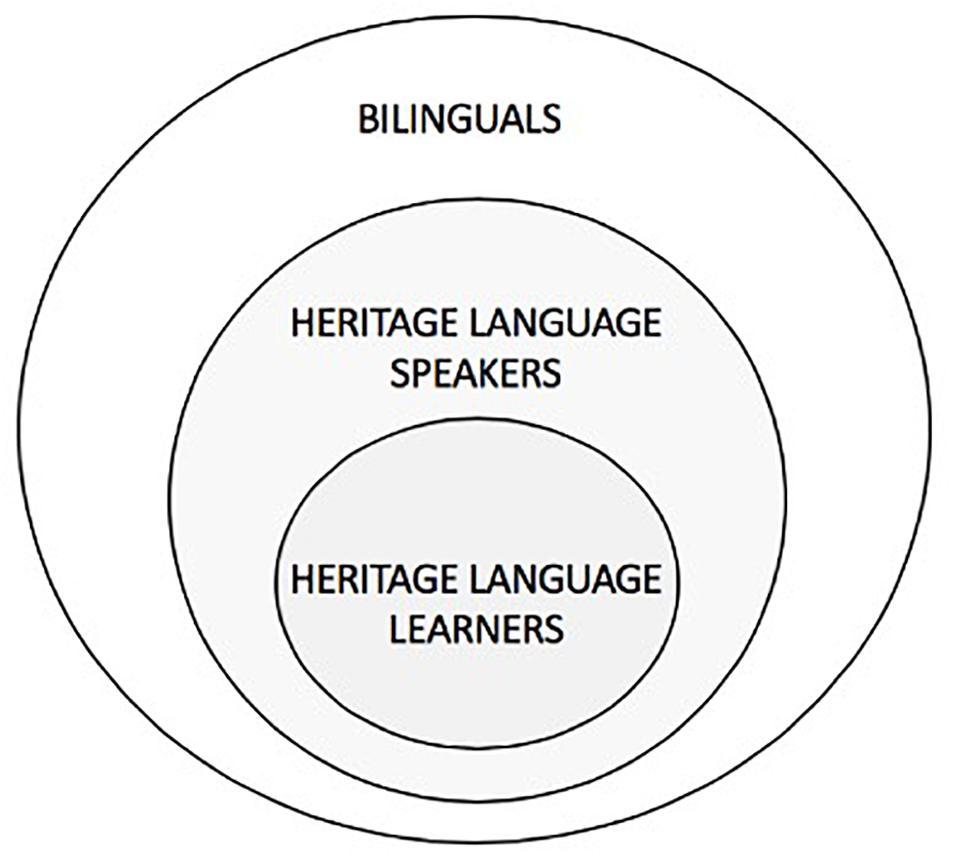

At the end of the 20th century a new type of language learner appeared in foreign/second (L2) language classrooms: heritage speakers of various immigrant languages. These students arrived in the host countries with their parents as young children or were born in immigrant or otherwise linguistically minoritized families. They all grew up speaking language(s) other than the dominant language of the society at home and became dominant in the language of their new society, which could be either their other first language for simultaneous bilinguals or their second language (for sequential bilinguals or early L2 learners). The schooling these bilingual speakers received in the host country, along with other social demands, prompted their switch to the societally dominant language, limiting their exposure to the home, or heritage, language (HL) and the contexts of its use. That, in turn, significantly changed the developmental trajectory of the HL in these bilinguals (Montrul, 2016). As young adults1 some of these HL speakers “wish[ed] to learn, re-learn, or improve their current level of linguistic proficiency in their family language” (Montrul, 2010, p. 3) and so, they found themselves in their high-school or college L2 classroom. In this article, we refer to those HL speakers who attempt a formal study of their HL as heritage language learners (HLLs). This is a self-selected and motivated group of learners who typically make a concerted effort to maintain their home language. We contend that it is important to recognize differences between HL speakers as a general group within a bilingual population and HLLs as a specific subset within that group; the relationships between these three groups are schematized in Figure 1.2

Figure 1. Relationship between bilinguals in general, heritage language speakers, and heritage language learners.

The number of HLLs in high-school- and college-level L2 classes has been steadily growing over the past 40 years, and the trend is likely to continue: in the United States, for instance, approximately 20% of the population speak a non-English language at home.3 While the number of HLLs in the mainstream L2 classrooms has been increasing, the field of language pedagogy has been slow to rise to the challenge of meeting the educational needs of these learners (Valdés, 2005). Yet, what has been clear to many, if not most, L2 educators from the very beginning is that the teaching of HLLs requires specialized pedagogical approaches since their knowledge of and experiences with the target language, as well as their motivations for (re)learning it, differ significantly from an average L2L (Kagan and Dillon, 2001; Potowski, 2015; Bayram et al., 2018; Carreira and Kagan, 2018; inter alia).

Russian as an HL in the United States provides a potent illustration of the way in which a new HL community has formed and developed, and how HLLs’ learning needs have been addressed in the language pedagogy field. The changes in the Russian language classroom demographics followed on the heels of changes in immigration trends. The latest and most populous wave of emigration from Russian-speaking countries, which began in the 1970s and peaked in the 1990s after the Soviet Union collapsed, deposited a large number of Russian-speaking emigres in the United States (Andrews, 1999; Zemskaja, 2001; Polinsky, 2010; Isurin, 2011; Dubinina and Polinsky, 2013; Laleko, 2013). The children of these Russian-speaking immigrants – heritage bilinguals – began to show up in Russian language classes in the early 1990s. Although according to the United States Census Bureau,4 Russian continues to be a widely spoken home language in the United States, “an analysis of the trajectory of linguistic development past immigration point reveals a steady decline in the use of Russian, even among newly arrived immigrants, alongside a rapid adoption of English, a pattern that is typical of the overall linguistic landscape in the United States” (Laleko, 2013, p. 89). Furthermore, as the wave of immigration from the former USSR subsided at the end of the 1990s, and the children of young immigrants of the 1980s and 90s grew up, the community is now raising second-generation HL speakers, i.e., children born to Russian-speaking families in the United States (Kagan, 2017). Such bilinguals may come to language classrooms from families where their parents, who may have arrived in the United States as teenagers, are unbalanced bilinguals themselves, dominant in English.

The field of Russian-language instruction has reacted to the shift in classroom demographics in the 1990s with relative agility, owing, on the one hand, to the work of colleagues in Spanish-language pedagogy (Valdés, 1998, 2005; Potowski and Carreira, 2004; Montrul, 2010; Potowski, 2014; Carreira, 2016), and on the other, to the visionary leadership of such Russian scholars as the late Olga Kagan (Kagan and Dillon, 2001, 2006; Kagan, 2005; Polinsky and Kagan, 2007; inter alia). In the last twenty or so years, many Russian-language educators have taught numbers of HLLs at all educational levels, from elementary school to college, sometimes developing their own materials and sometimes being aided by textbooks published for this learner population in the United States and in Israel (Kagan et al., 2006; Niznik et al., 2009; Kagan and Kudyma, 2015). These materials have been designed primarily for 1.5-generation speakers of Russian, i.e., those who left the Russian-speaking homeland in their late childhood. With the second generation of HLLs entering Russian classrooms, the most significant difference observed in the past few years from the perspective of Russian language teachers is a drastic reduction in literacy skills and monolingual grammatical intuitions among today’s Russian HLLs. And, thus, the changing profile of these heritage bilinguals – much as is the case with many other heritage groups in the United States – requires a rethinking of pedagogical approaches used in the classrooms populated by these learners.

New approaches rarely develop in a void, and a plausible place to start should be in the survey of current HL pedagogical approaches (with relevant insights from the field of L2 pedagogy), which we briefly review below.

The majority of current approaches widely used and discussed in HL instruction are rooted in the Proficiency movement of the 2000s, which serves as the general framework for teaching foreign languages in the United States overall (Liskin-Gasparro, 1984; American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, 1986; Carreira, 2016). The Proficiency movement, based on communicative approaches (also known as macro-approaches), downplays explicit grammar-based instruction and advocates for the creation of an immersive environment in the classroom, where communicative tasks are to be carried out exclusively in the target language and any pedagogical instruction to be conducted preferably in the target language. These approaches advocate engaging the learners with authentic texts and materials and practicing language through real-life tasks. They largely take a global approach to the language produced by learners, for example, teaching grammar on an ad hoc basis and filling the gaps in the structural knowledge as they arise in learners’ production of language. As a consequence, teachers are discouraged from paying attention to the details of grammar and subtle grammatical concepts, including those which are different from the dominant-language counterpart or absent from the bilingual’s dominant language.

Researchers and practitioners in the field of HL education have argued that such macro-approaches as content-based, genre-based, project-based, task-based, and experiential learning models, are most effective for HLLs because they build on these learners’ existing global linguistic competencies; ideally, they also enhance learners’ cultural awareness and bilingual identity, and foster involvement with the heritage community (Kagan and Dillon, 2009; Carreira, 2016).

In addition to the Proficiency-motivated macro approaches, other pedagogical frameworks that have recently been advocated specifically for HL classrooms build on the findings from sociolinguistic research on bilingualism and aim to empower HLLs so that they would play an agentive role in their own learning and linguistic development. These approaches include the plurilingualism framework and the critical pedagogies framework (Correa, 2011; Bayram et al., 2018), both of which call on language teachers to engage learners in critical investigations of bilingual competences and to embrace linguistic diversity as a tool for maximizing communication. Plurilingualism is a strategic position that views multiple languages of an individual or a society as interconnected and in constant interaction with each other, unlike multilingualism which views individual languages as independent entities. The plurilingualism framework encompasses and subsumes current sociolinguistic and pedagogical notions of trans-idiomatic practices (Jaquemet, 2005) and translanguaging (García, 2009; Creese and Blackledge, 2010). Critical pedagogies recognize the power dynamics inherent in multilingual contexts and focus on helping HLLs uncover and examine language ideologies toward minority and heritage languages in order to (re)claim the value of their HL identity and to legitimize bilingual practices in minority communities.

Most literature on the communicative and critical pedagogies described above does not address formal linguistic knowledge of HLLs. To be fair, the proponents of these approaches do not advocate for a complete abandonment of explicit grammar instruction (Carreira, 2016, p. 162; Bayram et al., 2018; Carreira and Kagan, 2018). These researchers raise the question as to when and how such instruction should be introduced in the learning process; yet, this question remains largely unanswered. As described in Kagan and Dillon (2001, 2009), Carreira (2016), and Carreira and Kagan (2018) among others, macro-approaches are supposed to engage students “in complex tasks at the onset of instruction rather than starting with grammar explanations and vocabulary lists, as is typically the case with L2 instruction” (Carreira and Kagan, 2018, p. 156).

Educators recognize the value of engaging learners in critical analyses of existing bilingual practices and unbalances inherent in bilingual/plurilingual competencies through authentic and meaningful tasks. At the same time, it is puzzling that despite the use authentic and meaningful tasks, HLLs often seem to be unable to move beyond the Intermediate level of language proficiency (as measured by the ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines scale) and struggle to express the complexity and the nuances of their rich identities in their home language. These observations suggest that current methodologies do not meet HLL’s needs in their entirety. Furthermore, the outcomes of macro-approaches have not been adequately evaluated due to lack of classroom-based research in the field of HL pedagogy. On the one hand, studies report that HLLs eagerly participate in language tasks and projects – after all, this is something they are used to in the naturalistic language setting at home. On the other hand, these learners treat communicative classrooms with performance orientation; in other words, they focus on carrying out a communicative task rather than on expressing nuanced meanings through accurate and appropriate use of grammatical and discourse structures, especially those that are grammatically or conceptually complex or rare in language (Torres, 2013; Carreira, 2016). Knowing standard monolingual grammar should certainly not be a means to an end; expanding and fine-tuning HLLs’ repertoire of linguistic means to express precise and nuanced meanings is exactly what will help them engage with their cultural heritage and bilingual community practices in a meaningful way.

Research from the field of L2 instruction has drawn similar conclusions: L2 learners in immersive instructional environments continue to encounter problems with grammatical forms, especially if their native language and the L2 mark meaning differently and if these differences in meaning are not perceived by the learners. The current thinking on L2 pedagogy, thus, posits that learners need to be provided with at least some form of explicit grammar instruction in order to develop structural accuracy (Brinton et al., 2003; McManus, 2015; Nishi and Shirai, 2016, inter alia). Form-focused activities have proven to increase structural accuracy for L2 learners of Russian; for example, Gor and Chernigovskaya (2005) report that learners were able to develop native-like processing strategies of Russian verbs after being exposed to structured grammar instruction and practice. Comer and deBenedette (2010, 2011), having compared different form-focused approaches (specifically, traditional grammar instruction followed by mechanical drills, and structured input/processing instruction), found that both types effectively facilitated the L2 acquisition of Russian structures.

Although research on the effectiveness of pedagogical strategies is new in the field of HL pedagogy, evidence has emerged that explicit grammar teaching produces positive outcomes for structural accuracy among HLLs (Potowski et al., 2009; Montrul and Bowles, 2010; Bowles, 2011). Conversely, poor command of standard grammar has been shown to negatively impact global proficiency ratings for HLLs (Swender et al., 2014).

Acknowledging the fact that the number of classroom-based and laboratory-based instructed heritage language acquisition studies (IHLA) is very small (Bowles and Torres, forthcoming), we, nonetheless, consider the insights gained from these studies, coupled with extensive linguistic research on HLs and their speakers available to date, to be helpful in forming a solid foundation for appropriate HL pedagogical approaches (Rothman et al., 2016; Bayram et al., 2018).

The special circumstances which shape HLLs’ linguistic profiles include, first and foremost, early naturalistic exposure to the home language (Pires and Rothman, 2009; Rothman, 2009; Pascual y Cabo and Rothman, 2012; Kupisch, 2013; Putnam and Sánchez, 2013; Montrul, 2016; Carreira and Kagan, 2018; Polinsky, 2018, inter alia). This exposure normally leads to fairly well-developed aural (auditory) skills and conversational proficiency in informal registers (Montrul, 2008, 2010, 2016; Carreira and Kagan, 2011). Nonetheless, the amount of linguistic input that HL speakers receive is reduced compared to the dominant language even in the best-case scenarios (Rothman, 2007; O’Grady et al., 2011); this input is also limited to topics related to the speaker’s immediate environment such as family, home life, food, etc (Montrul, 2010; He, 2014, 2016). From preschool on, HL speakers usually explore the world outside their immediate home environment through the dominant language, and as a result, rarely acquire the variety of genres in the home language that are usually available to an educated speaker in the homeland. Most importantly, the majority of HL-speaking children in the United States do not receive formal education in their home language (even the best-case scenarios of early bilingual education often fall short), and therefore, their linguistic development is further undermined by lack of literacy.

Limited input, both in terms of the amount of input and in terms of modality, creates unfavorable circumstances for HL development. As shown in research on HLs, functional linguistic material such as articles, particles, auxiliaries, or word inflections, all short linguistic segments characterized by low perceptual salience, are challenging to HL speakers. Lowered perceptibility, combined with reduced frequency of input, lack of literacy, and cross-linguistic influence from the dominant language, drives the restructuring of the grammatical system (Bayram et al., 2018; Polinsky, 2018). To illustrate that in relation to Russian, our test case in this paper, speakers of heritage Russian have difficulty with inflectional morphology, in particular morphology of case and agreement (Polinsky, 2006, 2008a,b, 2011, 2016a,b; Rodina and Westergaard, 2013; Ivanova-Sullivan, 2014; Laleko, 2018, 2019; Mitrofanova et al., 2018, among others). Problems with inflectional morphology in turn lead to difficulties with word order (Isurin and Ivanova-Sullivan, 2008; Sekerina and Trueswell, 2011; Ivanova-Sullivan, 2014). In addition, Russian HLLs have difficulty with certain types of complex sentences (Kisselev and Alsufieva, 2017), verbal aspect (Laleko, 2010, 2011, 2013, 2015; Mikhaylova, 2012, 2019), information structure (Isurin and Ivanova-Sullivan, 2008; Ivanova-Sullivan, 2014; Laleko and Dubinina, 2018; Kisselev, 2019), and pragmatic contrasts (Dubinina and Malamud, 2017). Many contrasts in all these aspects of language structure are based on the recognition of subtle grammatical distinctions, which may remain undetected by HL speakers.

All these considerations point to the need to enhance the attention to grammar in HLL classrooms, all the while keeping up the emphasis on authentic tasks. In the next section we offer a proposal on the ways to enhance form-focused instruction in HLL classrooms.

As the research reviewed above shows, HL speakers often fail to register less perceptible distinctions in grammatical forms and are also unfamiliar with less frequent features of their home language or those language properties that require a complex mapping between form and interpretation (Polinsky and Scontras, 2020). These aspects of language are unlikely to benefit from purely communicative pedagogies which downplay focus on form; the forms that are perceptually less salient will simply continue to be ignored in the input, and the uncommon forms or structures will not reach the needed frequency and saturation in the input without specific, pedagogical manipulation of this input. Therefore, we see the task of HL pedagogy in helping HLLs notice infrequent or perceptually non-salient linguistic structures in the input and reflect on meaning-form relationships. Such an approach allows HLLs to become linguistically aware users of their home language, all the while without sacrificing principles of communicative and critical pedagogies. In an attempt to answer the fully justified question raised by Carreira (2016) on when and how to implement focus-on-form activities, we suggest that language-focused instruction should be the driving force of the curriculum; and while keeping up the ultimate goal of growing HLLs’ functional ability in sight, we begin each instructional unit with a set of activities that develop (1) attention to grammatical form (noticing) and ability to recognize and analyze form-meaning mappings, (2) conceptual understanding of grammar, and (3) metalinguistic awareness. The development of these skills requires explicit focus on language structure.

Following Ellis (1994), who suggests that “explicit learning is a more conscious operation where the individual makes and tests hypotheses in a search for structure” (p.1), we propose that HL learners be taught to analyze linguistic structures by noticing the form.

Researchers have noted that traditional explicit explanations of grammar may be confusing to HLLs due to their lack of experience with grammatical activities and lack of metalanguage (e.g., Potowski et al., 2009, p. 563; Beaudrie et al., 2014, p. 163). Such an approach to form-focused learning also disregards HLLs’ existing language knowledge and intuitions. Additionally, in our experience, many traditional explicit explanations of grammar fail to foreground the functional purpose of grammatical structures, making language learners lose interest and stop paying attention to grammar.

To address this issue, we propose to engage HLLs in guided analysis of language that drives the discovery of linguistic patterns. As an example, we may start working on the Russian language structure “Dative + emotive state” by presenting the HLLs with a number of language samples illustrating the use of the structure providing the pattern for masculine nouns first, as illustrated by examples (1)–(3) which all have masculine singular nouns in the dative:5

Based on a set like this (which normally includes a lot more examples, enough to establish strong patterns), HLLs are asked to record initial observations about the patterns they see (notice) and to formulate a hypothesis regarding the meaning of the focus form (form-meaning mapping).

While Russian masculine nouns take the ending -u in the dative, the exponent of the dative is different for feminine nouns (Timberlake, 2004, p. 130ff.). Once the learners discover the masculine paradigm, they are offered contexts in which the same structure is used with feminine nouns, which would prompt them to refine the initial hypothesis, because the ending -u is no longer tenable as the dative case marker in the target structure. Once the learners have internalized the dative of feminine nouns in the singular, one can add plural forms of those, and other forms should be added until the entire dative-case paradigm is observed and registered.

These sorts of data-driven, hypothesis-building activities rely on HLLs’ existing intuitions and compel HLLs to notice subtle differences across forms, make form-meaning connections, and adjust their linguistic intuitions toward more native-like norms. These types of activity may be followed by an activity that allows for an explicit comparison of the relevant feature in the dominant and the heritage languages: are the features similar or different? For example, the Russian construction denoting a psychological state typically includes the experiencer in the dative case and a verbal or adjectival predicate denoting the emotion; this is different from the English structure deployed for expression of emotions, where the experiencer appears in the nominative case and the emotion predicate typically includes a participle or an adjective, e.g., Steven was bored, the professor was glad, the student was embarrassed. A direct comparison of the differences between Russian and English constructions expressing psychological states may segue smoothly into a discussion of how different languages encode emotions.

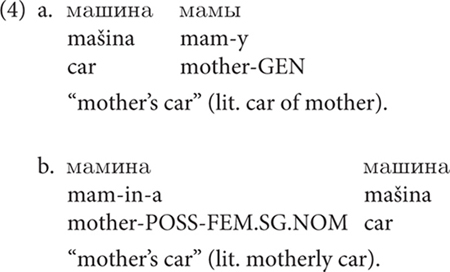

Activities that develop attention to form should also incorporate tasks that lead HLLs to discover that form and meaning do not always stand in one-to-one correspondence. Monolingual native speakers may have intuitive understanding of this fact, but for heritage bilinguals, this knowledge needs to be made explicit since they have a general tendency to lose optionality in linguistic expression (Polinsky, 2018). For example, in Russian, possession can be expressed in two ways, with the possessor in the genitive case (4a) and possessor expressed by an adjective (4b). Although English also has two ways of expressing possession (mother’s car vs. car of mother), the contrast between the two available forms is not the same, and Russian HLLs should be guided to explore the subtle stylistic and structural differences between possessors in the genitive case and possessive adjectives:

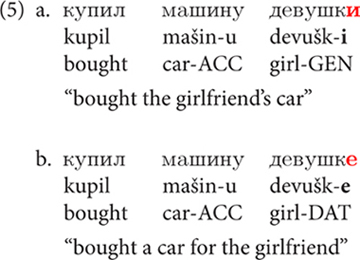

Finally, instructors should emphasize the subtlety of form-meaning mappings, especially if these mappings depend on elements that are short and unstressed (like case endings), which makes them easy to confuse in spelling and pronunciation. For instance, HLLs can be invited to analyze the endings of the word devuška “girl, girlfriend” in the examples below (5a, b), and provide activities where learners have to express intended meaning by choosing the appropriate ending.

Once the learners establish and confirm their hypotheses about linguistic patterns and engage in other forms of noticing activities, they can be introduced to linguistic terminology that describes the structures under analysis. As research on the role of explicit instruction suggests (e.g., McManus, 2015), the key to appropriate production of a grammatical form is conceptual understanding of a grammatical concept, especially when the concept is complex and elaborate, such as the Russian case system or Russian aspectual system. Providing learners with tools for describing how the language functions may significantly contribute to the formation and/or fine-tuning of their conceptual understanding of grammatical form.

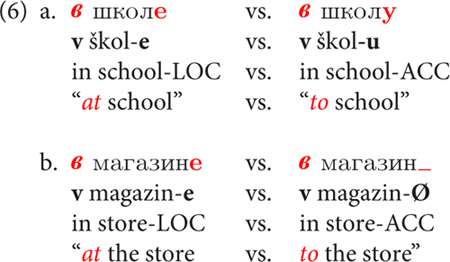

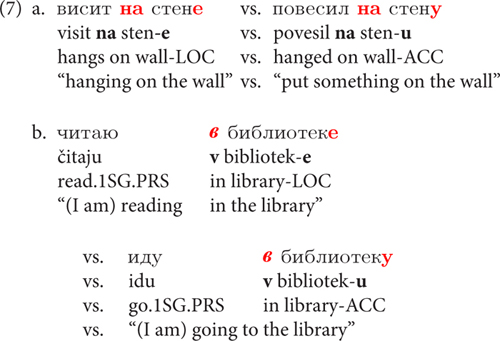

In order to be effective, the teaching of appropriate form-meaning connections should also involve conceptual learning based on comparisons between the HL and the HLL’s dominant language. For example, highlighting the difference between the ways in which Russian and English distinguish location and direction will draw learners’ attention to the significance of hard-to-perceive inflections to express this distinction in Russian:

Comparative analysis of structures should also involve specific form-meaning connections in HL without contrast with the dominant language. Continuing with the concept of directionality, Russian HLLs can be guided to analyze pairs of sentences that differ in the prepositional phrases that follow verbs of location and direction:6

Activities that follow the initial language analysis should include tasks that allow the HLLs to practice the new concepts and further operationalize their grammatical skills. Such activities can include finding the target form in a text, supplying missing elements, writing dictations, and producing speech samples (especially in writing) where the target form must be used.

The third proposed principle has to do with the development of metalinguistic awareness. SLA research shows that awareness and attention in L2 learning enhance the acquisition of functional elements associated with grammar (Jessner, 2006). HL speakers invariably outperform L2 learners in terms of metalinguistic awareness; in other words, they enjoy a higher starting point compared to L2 learners, and they bring this advantage to the classroom. It is therefore crucial to activate HLLs’ implicit knowledge of the linguistic system and to enhance this knowledge by building it from the bottom up. The types of activities described above contribute to the learners’ metalinguistic awareness, precisely because they engage students in explicit, conscious learning and make them reflect on the workings of their language.

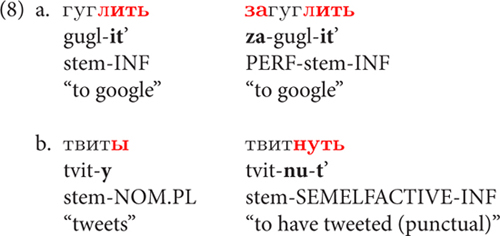

With respect to metalinguistic awareness, it is also important to remember that the normal mode of communication for HL speakers involves code-switching, code-mixing, and lexical borrowing. Therefore, the development of HLLs’ metalinguistic awareness should engage their awareness of both languages, the dominant language and their home language. To illustrate, Russian HLLs can be asked to borrow items from English (including those that have recently become accepted borrowings in the homeland, for instance, google, tweet, or post) and then apply the rules of Russian morphology to create different parts of speech from such borrowed roots (8).

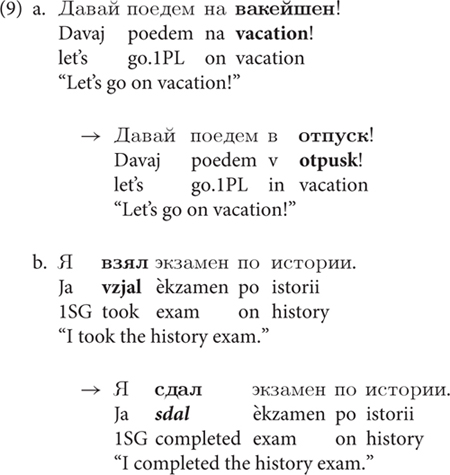

Heritage language learners should also be engaged in the analysis of code-mixing that characterizes the immigrant variety but is not sanctioned in the standard variety. To illustrate, HLLs can be asked to unpack code-switched items or borrowings from English and replace “Runglish” vocabulary items (9a) and structures (9b) with monolingual Russian, as in the examples below (9a,b):

The focus-on-form approach described above is perhaps best suited for learners at the lower end of HL proficiency (those who are usually performing in the Intermediate range on the ACTFL scale). However, higher-level HL speakers may still benefit from focus-on-form activities. For instance, Laleko and Polinsky (2013) argue that even higher proficiency learners struggle with semantic and discourse-pragmatic computation. The authors suggest that integrating knowledge across clausal, sentential, and contextual domains is a complex task that requires simultaneous processing of linguistic and non-linguistic material. Similarly, Swender et al. (2014) point out that HL learners at the ACTFL Advanced level do not receive a Superior rating mainly because they cannot produce well-organized extended discourse. Thus, explicit focus on these higher-level linguistic concepts would aid HL learners in achieving native-like proficiency.

All told, we do not wish to imply that only form-focused activities have a place in the HL classroom; a syllabus for a HL course should indeed be based on developing learners’ functional skills and all form-focus activities must show language in context of the function. What we strongly advocate for is the approach under which the teaching of grammar must be an integral part of HLLs’ communicative development from the very beginning.

The continued presence of a sizable number of HLLs in American classrooms demands that the field develops a well-articulated HL pedagogy to serve the specific needs of this group of learners. The field of instructed heritage language acquisition is in its infancy, and while we applaud and encourage classroom-based and laboratory-based pedagogical studies, we also contend that looking at linguistic research for guidance is a fruitful way to re-think pedagogical practices in a HL classroom. One of the most influential teaching philosophies endorsed by language education in the United States concerns having a learner-centered curriculum. This approach advocates that the learners themselves should be taken as “… the central reference point for decision-making regarding both the content and the form of language teaching” (Tudor, 1996, p. 23). Because of the unique circumstances under which HLLs acquire their first language, the notion of learner-centeredness is particularly useful for HL pedagogy as it directs educators to first determine what the students already know and what they need to know, and numerous linguistic studies available to date provide us with this information.

The existing linguistic research on Russian HLLs allows us to anticipate gaps in their knowledge and at the same time build on their strengths. In this paper, we have offered a set of principles underlying HL pedagogy that are rooted in the understanding of HLLs’ knowledge gaps and learning advantages. These principles call for exposing HLLs to form-focused instruction from the start of their (re-)learning process. In establishing our guiding principles, we rely on the observation that HL speakers have strong intuitions about their language, something that sets them apart from L2 learners; the goal of HL instruction is to rely on these intuitions and to make them stronger. Summarized briefly, the principles we propose include: (1) developing HLLs’ attention to grammatical form and building their ability to recognize and analyze form-meaning mappings, (2) fostering HLLs’ understanding of grammatical concepts (especially if some of them are lacking in the dominant language), and (3) enhancing HLLs’ metalinguistic awareness. Our proposed approach is based on the conception that HL (re-)learning should be a discovery process, where HLLs formulate hypotheses about their language and test these hypotheses by relying on their intuitions, on their general analytical abilities, and on the tools provided by the instructor. If applied regularly, this discovery process allows HLLs to enhance their metalinguistic awareness and focus on form as a way to convey meaning; at the same time, the proposed approach keeps the students more engaged and motivated than traditional grammar instruction.

Specific pedagogical techniques in HL classrooms should be different from both grammar instruction for native speakers in the homeland as well as for L2 learners in the United States classrooms, and have to include language-specific materials and strategies required by a given HL (for instance, the teaching of a different writing system, among other things). Nevertheless, the principles we have proposed here derive from the general understanding of HLLs’ language competence, and as such, are applicable to a wide range of heritage languages. Specific techniques should also take into consideration the well-documented wide variance in proficiency in heritage populations (which in our case should be taken as the level of language competency at the beginning of a given HL class). The average proficiency of HL speakers varies both within a particular HL community and across speakers of an individual HL; the variation across communities is often due to differences in sociolinguistic and demographic circumstances. For instance, Russian HL speakers in the United States have a more limited range of interlocutors and opportunities for uninterrupted input than Spanish HL speakers, who are more likely to be exposed to a distinct community-level variety in addition to the home language variety.7 The proficiency level of HLLs may limit the types of important discussions and tasks that are encouraged by macro-approaches and critical pedagogies in a language classroom. Therefore, targeted form-focused language practice is particularly important in order for a critical analysis of bilingual abilities, practices and identities to be successful and informative.

In closing, we would like to emphasize the growing need for pedagogy-oriented research conducted in the lab and in the classroom, and for theoretical and pedagogical research on HLs to find common ground (Rothman et al., 2016; Bayram et al., 2018). If the purpose of an HL speaker in taking a language course is to expand their linguistic repertoire, to be functionally more effective, to expand on the topics and genres available to them, then the role of the HL teacher is to provide opportunities to explore the topics, genres, and registers as well as linguistic structures that service them in different dialectal varieties of this language. This agenda calls for explicit attention to language, and that in turn underscores the need for an ongoing dialogue between language scientists who study HLs and understand their difference from the baseline, and language educators whose goal is to bring HLLs closer to the baseline. Cross-disciplinary research should cut across different heritage languages, comparing the same pedagogical approaches applied to different heritage/dominant language pairings. It is also critical to investigate how HL learners at different levels of proficiency react to pedagogical treatments. New and effective HL teaching approaches and methods will follow, and all the subfields invested in HL research stand to gain from these developments.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

This work was supported in part by the Brandeis University’s Theodore and Jane Norman Awards for Faculty Scholarship to Irina Dubinina. All errors are our responsibility.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We are grateful to Jason Merrill, Greg Scontras, and two reviewers for helpful comments on this manuscript.

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (1986). ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines. Yonkers, NY: American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages.

Andrews, D. (1999). Sociocultural Perspectives on Language Change in Diaspora: Soviet Immigrants in the United States (Impact: Studies in Language and Society). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Bayram, F., Prada, J., Pascualy Cabo, D., and Rothman, J. (2018). “Why should formal linguistic approaches to heritage language acquisition be linked to heritage language pedagogies?,” in Handbook of Research and Practice in Heritage Language Education, eds P. Trifonas and T. Aravossitas (Berlin: Springer), 187–206.

Beaudrie, S. M., Ducar, C., and Potowski, K. (2014). Heritage Language Teaching: Research and Practice. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

Bowles, M. A. (2011). Measuring implicit and explicit linguistic knowledge: what can heritage language learners contribute? Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 33, 247–271. doi: 10.1017/s0272263110000756

Bowles, M. A., and Torres, J. (forthcoming). “Instructed heritage language acquisition,” in Handbook of Heritage Languages, eds S. Montrul and M. Polinsky (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Brinton, D., Snow, M. A., and Wesche, M. B. (2003). Content-Based Second Language Instruction. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Carreira, M. (2016). “A general framework and supporting strategies for teaching mixed classes,” in Advances in Spanish as a Heritage Language, ed. D. Pascal y Cabo (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 159–176. doi: 10.1075/sibil.49.09car

Carreira, M., and Kagan, O. (2011). The results of the national heritage language survey: implications for teaching, curriculum design, and professional development. Foreign Lang. Ann. 44, 40–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2010.01118.x

Carreira, M., and Kagan, O. (2018). Heritage language education: a proposal for the next 50 years. Foreign Lang. Ann. 51, 152–168. doi: 10.1111/flan.12331

Comer, W. J., and deBenedette, L. (2010). Processing instruction and Russian: issues, materials, and preliminary experimental results. Slav. East Eur. J. 54, 118–146.

Comer, W. J., and deBenedette, L. (2011). Processing instruction and Russian: further evidence is IN. Foreign Lang. Ann. 44, 646–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2011.01155.x

Correa, M. (2011). Advocating for critical pedagogical approaches to teaching Spanish as a heritage language: some considerations. Foreign Lang. Ann. 44, 308–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2011.01132.x

Creese, A., and Blackledge, A. (2010). Translanguaging in the bilingual classroom: a pedagogy for learning and teaching? Mod. Lang. J. 94, 103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00986.x

Dubinina, I., and Malamud, S. (2017). Emergent communicative norm in a contact language: indirect requests in heritage Russian. Linguistics 55, 67–116.

Dubinina, I., and Polinsky, M. (2013). “Russian in the U.S,” in Slavic Languages in Migration, eds M. Moser and M. Polinsky (Vienna: Lit Verlag), 130–163.

García, O. (2009). Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Gor, K., and Chernigovskaya, T. (2005). “Formal instruction and the acquisition of verbal morphology,” in Investigations in Instructed Second Language Acquisition, Vol. 25, eds A. Housen and M. Pierrard (Berlin: Walter De Gruyter), 131–164.

He, A. W. (2014). “Identity construction throughout the life cycle,” in Handbook of Heritage and Community Languages in the United States: Research, Educational Practice, and Policy, eds T. Wiley, J. K. Peyton, D. Christian, S. Moore, and N. Liu (New York, NY: Routledge), 324–332.

He, A. W. (2016). “Heritage language learning and socialization,” in Language Socialization. Encyclopedia of Language and Education, Vol. 8, eds P. A. Duff and S. May (Dordrecht: Springer), 183–194. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-02255-0_14

Isurin, L. (2011). Russian Diaspora: Culture, Identity, and Language Change. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Isurin, L., and Ivanova-Sullivan, T. (2008). Lost in between: the case of Russian heritage speakers. Herit. Lang. J. 6, 72–103.

Ivanova-Sullivan, T. (2014). Theoretical and Experimental Aspects of Syntax-Discourse Interface in Heritage Grammars. Leiden: Brill.

Jaquemet, M. (2005). Transidiomatic practices: language and power in the age of globalization. Lang. Commun. 25, 257–277. doi: 10.1016/j.langcom.2005.05.001

Jessner, U. (2006). Linguistic Awareness in Multilinguals. English as a Third Language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Kagan, O. (2005). In support of a proficiency-based definition of heritage language learners: the case of Russian. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 8, 213–221. doi: 10.1080/13670050508668608

Kagan, O. (2017). Heritage Language Curricular Development for Russian Heritage Speakers: Foundations and Rationale [Webinar]. ACTR. Available online at: http://www.actr.org/heritagewebinar.html (accessed March 28, 2020).

Kagan, O., Akishina, T., and Robin, R. (2006). Russkij Dlja Russkix [Russian for Russians]. Bloomington: Slavica.

Kagan, O., and Dillon, K. (2001). A new perspective on teaching Russian: focus on the heritage learner. Slav. East Eur. J. 45, 507–518.

Kagan, O., and Dillon, K. (2006). Russian heritage learners: so what happens now? Slav. East Eur. J. 50, 83–96.

Kagan, O., and Dillon, K. (2009). “The professional development of teachers of heritage language learners: a matrix,” in Bridging Contexts, Making Connections: Selected Papers from the Fifth International Conference on Language Teacher Education [CARLA Working Paper Series], eds M. Anderson and A. Lazarato (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota), 155–175.

Kagan, O., and Kudyma, A. (2015). Uèimsja Pisat’ Po-Russki. Ekspress-Kurs Dlja Dvujazyènyx Vzroslyx [Learning to Write in Russian. Express-Course for Bilingual Adults]. Moscow: Zlatoust.

Kisselev, O. (2019). Word order patterns in the writing of heritage and second language learners of Russian. Russ. Lang. J. 69, 149–174.

Kisselev, O., and Alsufieva, A. (2017). The development of syntactic complexity in the writing of Russian language learners: a longitudinal corpus study. Russ. Lang. J. 67, 27–53.

Kupisch, T. (2013). A new term for a better distinction? A view from the higher end of the proficiency scale. Theor. Linguist. 39, 203–214.

Kupisch, T., and Rothman, J. (2018). Terminology matters! Why difference is not incompleteness and how early child bilinguals are heritage speakers. Int. J. Biling. 22, 564–582. doi: 10.28920/dhm49.3.152-153

Laleko, O. (2011). Restructuring of verbal aspect in heritage Russian: beyond lexicalization. Int. J. Lang. Stud. 5, 13–26.

Laleko, O. (2013). Assessing heritage language vitality: Russian in the United States. Herit. Lang. J. 10, 89–102.

Laleko, O. (2015). “From privative to equipollent: incipient changes in the aspectual system of heritage Russian,” in Slavic Grammar from a Formal Perspective, eds G. Zybatow, P. Biskup, M. Guhl, C. Hurtig, O. Mueller-Reichau, and M. Yastrebova (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang), 273–286.

Laleko, O. (2018). What is difficult about grammatical gender? Evidence from heritage Russian. J. Lang. Contact 11, 233–267.

Laleko, O. (2019). Resolving indeterminacy of gender agreement: comparing heritage speakers and L2 learners of Russian. Herit. Lang. J. 16, 151–182.

Laleko, O., and Dubinina, I. (2018). “Word order production in heritage Russian: perspectives from linguistics and pedagogy,” in Connecting Across Languages and Cultures: A Heritage Language Festschrift in Honor of Olga Kagan, eds S. Bauckus and S. Kresin (Bloomington: Slavica), 191–215.

Laleko, O., and Polinsky, M. (2013). Marking topic or marking case: a comparative investigation of heritage Japanese and heritage Korean. Herit. Lang. J. 10, 178–202.

Laleko, O. V. (2010). The Syntax-Pragmatics Interface in Language Loss: Covert Restructuring of Aspect in Heritage Russian. Doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Liskin-Gasparro, L. (1984). “The ACTFL proficiency guidelines: a historical perspective,” in Teaching for Proficiency: The Organizing Principle, ed. T. V. Higgs (Skokie, IL: National Textbook Co Littlewood), 11–42.

Lohndal, T., Rothman, J., Kupisch, T., and Westergaard, M. (2019). Heritage language acquisition: what it reveals and why it is important for formal linguistic theories. Lang. Linguist. Compass 13:e12357.

McManus, K. (2015). L1–L2 differences in the acquisition of form-meaning pairings: a comparison of English and German learners of French. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 71, 51–77.

Mikhaylova, A. (2012). Aspectual knowledge of high proficiency L2 and heritage speakers of Russian. Herit. Lang. J. 9, 50–69.

Mikhaylova, A. (2019). What we know about the acquisition of Russian aspect as a first, second, and heritage language: state of the art. Herit. Lang. J. 16, 183–210.

Mitrofanova, N., Rodina, Y., Urek, O., and Westergaard, M. (2018). Bilinguals’ sensitivity to grammatical gender cues in Russian: the role of cumulative input, proficiency, and dominance. Front. Psychol. 9:1894. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01894

Montrul, S. (2008). Second language acquisition welcomes the heritage language learner: opportunities of a new field. Sec. Lang. Res. 24, 487–506.

Montrul, S. (2010). Current issues in heritage language acquisition. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 30, 3–23. doi: 10.1017/s0267190510000103

Montrul, S., and Bowles, M. (2010). Is grammar instruction beneficial for heritage language learners? Dative case marking in Spanish. Herit. Lang. J. 1, 47–73.

Nishi, Y., and Shirai, Y. (2016). “The role of linguistic explanation in the acquisition of Japanese imperfective-te iru,” in Theory, Research and Pedagogy in Learning and Teaching Japanese Grammar, eds A. Benati and S. Yamashita (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 127–155. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-49892-2_6

Niznik, M., Vinokurova, A., Voroncova, I., Kagan, O., and Cherp, A. (2009). Russkij bez Granic [Russian without Borders]. Moscow: Russkij mir.

O’Grady, W., Lee, O. S., and Lee, J. H. (2011). Practical and theoretical issues in the study of heritage language acquisition. Herit. Lang. J. 8, 23–40.

Pascual y Cabo, D., and Rothman, J. (2012). The (IL) logical problem of heritage speaker bilingualism and incomplete acquisition. Appl. Linguist. 33, 450–455. doi: 10.1093/applin/ams037

Pires, A., and Rothman, J. (2009). Disentangling sources of incomplete acquisition: an explanation for competence divergence across heritage grammars. Int. J. Biling. 13, 211–238. doi: 10.1177/1367006909339806

Polinsky, M. (2008a). Gender under incomplete acquisition: heritage speakers’ knowledge of noun categorization. Herit. Lang. J. 6, 40–71.

Polinsky, M. (2008b). “Without aspect,” in Case and Grammatical Relations, eds G. Corbett and M. Noonan (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 263–282.

Polinsky, M. (2010). Russkij jazyk pervogo i vtorogo pokolenija emigrantov, zhivuschix v SShA. Slav. Helsingiensia 40, 336–352.

Polinsky, M. (2011). Reanalysis in adult heritage language: new evidence in support of attrition. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 33, 305–328. doi: 10.1017/s027226311000077x

Polinsky, M. (2016a). Bilingual children and adult heritage speakers: the range of comparison. Int. J. Biling. 22, 547–563. doi: 10.1177/1367006916656048

Polinsky, M., and Kagan, O. (2007). Heritage languages: in the ‘wild’ and in the classroom. Lang. Linguist. Compass 1, 368–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-818x.2007.00022.x

Polinsky, M., and Scontras, G. (2020). Understanding heritage languages. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 23, 4–20. doi: 10.1017/s1366728919000245

Potowski, K. (2014). “Spanish in the United States,” in Handbook of Heritage, Community, and Native American Languages in the United States, eds T. Wiley, J. K. Peyton, D. Christian, S. C. K. Moore, and N. Liu (London: Routledge), 104–114.

Potowski, K., and Carreira, M. (2004). Teacher development and National Standards for Spanish as a heritage language. Foreign Lang. Ann. 37, 427–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2004.tb02700.x

Potowski, K., Jegerski, J., and Morgan-Short, K. (2009). The effects of instruction on linguistic development in Spanish heritage language speakers. Lang. Learn. 59, 537–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9922.2009.00517.x

Putnam, M. T. (2020). Separating vs. shrinking. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 23, 41–42. doi: 10.1017/s1366728919000415

Putnam, M. T., and Sánchez, L. (2013). What’s so incomplete about incomplete acquisition? A prolegomenon to modeling heritage language grammars. Linguist. Approaches Biling. 3, 478–508. doi: 10.1075/lab.3.4.04put

Rivers, W., and Brecht, R. (2018). America’s languages: the future of language advocacy. Foreign Lang. Ann. 51, 24–34. doi: 10.1111/flan.12320

Rodina, Y., and Westergaard, Ì (2013). Two gender systems in one mind: the acquisition of grammatical gender in Norwegian-Russian bilinguals. Hamb. Stud. Linguist. Divers. 1, 95–126. doi: 10.1075/hsld.1.05rod

Rothman, J. (2007). Heritage speaker competence differences, language change, and input type: inflected infinitives in Heritage Brazilian Portuguese. Int. J. Biling. 11, 359–389. doi: 10.1177/13670069070110040201

Rothman, J. (2009). Understanding the nature and outcomes of early bilingualism: romance languages as heritage languages. Int. J. Biling. 13, 155–163. doi: 10.1177/1367006909339814

Rothman, J., and Treffers-Daller, J. (2014). A prolegomenon to the construct of the native speaker: heritage speaker bilinguals are natives too! Appl. Linguist. 35, 93–98. doi: 10.1093/applin/amt049

Rothman, J., Tsimpli, I. M., and Pascual y Cabo, D. (2016). “Formal linguistic approaches to heritage language acquisition,” in Advances in Spanish as a Heritage Language, ed. D. Pascual y Cabo (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 13–26. doi: 10.1075/sibil.49.02rot

Sekerina, I. A., and Trueswell, J. C. (2011). Processing of contrastiveness by heritage Russian bilinguals. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 14, 280–300. doi: 10.1017/s1366728910000337

Swender, E., Martin, C., Rivera-Martinez, M., and Kagan, O. (2014). Exploring oral proficiency profiles of heritage speakers of Russian and Spanish. Foreign Lang. Ann. 47, 423–446. doi: 10.1111/flan.12098

Torres, J. (2013). Heritage and Second Language Learners of Spanish: The Roles of Task Complexity and Inhibitory Control. Doctoral dissertation, Georgetown University, Washington, DC.

Tudor, I. (1996). Learner-Centeredness as Language Education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Valdés, G. (1998). The world outside and inside schools: language and immigrant children. Educ. Res. 27, 4–18. doi: 10.3102/0013189x027006004

Valdés, G. (2005). Bilingualism, heritage language learners, and SLA research: opportunities lost or seized? Mod. Lang. J. 89, 410–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2005.00314.x

Keywords: heritage language, heritage language learner, heritage language pedagogy, metalinguistic awareness, attention to grammatical form, structural complexity, language proficiency, Russian

Citation: Kisselev O, Dubinina I and Polinsky M (2020) Form-Focused Instruction in the Heritage Language Classroom: Toward Research-Informed Heritage Language Pedagogy. Front. Educ. 5:53. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00053

Received: 22 September 2019; Accepted: 17 April 2020;

Published: 04 June 2020.

Edited by:

Laura Dominguez, University of Southampton, United KingdomReviewed by:

Fatih Bayram, Arctic University of Norway, NorwayCopyright © 2020 Kisselev, Dubinina and Polinsky. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Olesya Kisselev, b2xlc3lhLmtpc3NlbGV2QHV0c2EuZWR1

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.