- Faculty of Education, Queen's University, Kingston, ON, Canada

Research has consistently demonstrated that teachers' assessment actions have a significant influence on students' learning experience and achievement. While much of the assessment research to date has investigated teachers' understandings of assessment purposes, their developing assessment literacy, or specific classroom assessment practices, few studies have explored teachers' differential responses to specific and common classroom assessment scenarios. Drawing on a contemporary view of assessment literacy, and providing empirical evidence for assessment literacy as a differential and situated professional competency, the purpose of this study is to explore teachers' approaches to assessment more closely by examining their differential responses to common classroom assessment scenarios. By drawing on data from 453 beginning teachers who were asked to consider their teaching context and identify their likely actions in response to common assessment scenarios, this paper makes a case for a situated and contextualized view of assessment work, providing an empirically-informed basis for reconceptualizing assessment literacy as negotiated, situated, and differential across teachers, scenarios, and contexts. Data from survey that presents teachers with assessment scenarios are analyzed through descriptive statistics and significance testing to observe similarities and differences by scenario and by participants' teaching division1 (i.e., elementary and secondary). The paper concludes by considering implications for assessment literacy theory and future related research.

At the start of their initial teacher education program, we invited nearly 500 teacher candidates to identify and reflect on three of their most memorable moments from their schooling experience. For well over half of these students, at least one of their memories related to assessment—experiences of failing tests and their abilities being misjudged, experiences of powerful feedback that set them in new directions, or experiences of unfairness and bias in assessment results and reporting. Assessment is a powerful and enduring force within classroom learning. How teachers approach assessment in their classrooms has been shown in the research to either motivate or demotivate their students' learning (Harlen, 2006; Hattie, 2008; Cauley and McMillan, 2010), engage or disengage students from school (Brookhart, 2008; Gilboy et al., 2015), and promote or hinder student growth (Black and Wiliam, 1998b; Gardner, 2006). Importantly for this study, teachers' classroom assessment actions can also expose their fundamental beliefs about teaching and learning (Xu and Brown, 2016; Looney et al., 2017; Herppich et al., 2018).

Across many parts of the world, the past 20 years has seen significant policy developments toward increased accountability mandates and standards-based curricula that have resulted in the proliferation of assessment practices and uses within schools (Herman, 2008; Bennett and Gitomer, 2009; Brookhart, 2011). This proliferation has not only contributed to a greater complexity in the variety of assessments teachers are expected to use but has also demanded ongoing communication of evidence about student learning to various stakeholders—students, parents, teachers, administrators, and the public. Moreover, classroom assessment continues to occupy an ever-expanding role in classrooms from providing initial diagnostic information to guide beginning instruction to dominant traditional summative purposes of assessment for grading. Increasingly, teachers are also called to leverage daily formative assessments (i.e., assessment for learning) to monitor and support learning, as well as use assessment as learning to enhance students' metacognitive and self-regulatory capacities. Unsurprisingly, many teachers report feeling underprepared for these many assessment demands, particularly as they enter the teaching profession (MacLellan, 2004; Volante and Fazio, 2007; Herppich et al., 2018).

Alongside these practical and policy developments, researchers have worked to understand ways to define the skills and knowledge teachers need within the current assessment climate, a field known as “assessment literacy” (Popham, 2013; Willis et al., 2013; Xu and Brown, 2016; DeLuca et al., 2018) Arguably, among the many topics that exist within assessment and measurement, “assessment literacy” has received comparatively little attention despite its importance to the realities of how assessment is taken up in schools. Our interest in this paper, and in this Special Issue, is to prioritize “assessment literacy” as a focal area of assessment theory, one that requires increased theoretical attention given the contemporary professional demands on teachers.

While assessment literacy was first understood as a technical process, a set of skills and knowledge that teachers needed to know to be “literate” in the area of assessment, current thinking in the field suggests that teachers instead use a diversity of assessment practices derived from the integration of various sources of knowledge shaped by their unique contexts and background experiences (Herppich et al., 2018). Understanding classroom assessment then requires looking beyond teachers' knowledge in assessment, and rather investigating teachers' approaches to assessments in relation to their classroom teaching and learning contexts. To date, the majority of studies in the field have worked to (a) delineate characteristics for teacher assessment literacy, standards for assessment practice, and teachers' conceptualizations of assessment (e.g., Brown, 2004; Coombs et al., 2018; Herppich et al., 2018), (b) investigate teachers' specific assessment practices in various contexts (e.g., Cizek et al., 1995; Cauley and McMillan, 2010), (c) explore the reliability and validity of teacher judgments related to formative and summative assessments (e.g., Brookhart, 2015; Brookhart et al., 2016), and (d) examine the alignment between teachers' assessment activities and system priorities and practices (e.g., Guskey, 2000; Alm and Colnerud, 2015). As the field of classroom assessment research continues to mature (McMillan, 2017), additional studies that explore the nuanced differences in teachers' conceptualizations and enactment of assessment based on context and background would serve to provide empirical credence for a more contemporary understanding of assessment literacy, one that views assessment as a negotiated set of integrated knowledges and that is enacted differentially across contexts and teachers (Willis et al., 2013).

Our intention in this paper is to explore the notion of a differential view of assessment literacy. Specifically, we are interested in how elementary (grades K−8) and secondary (grades 9–12) teachers might respond differently to common assessment scenarios given differences in their teaching contexts yet similarities in the broader policy environment and their pre-service education background. By drawing on data from 453 teachers' responses to five common classroom assessment scenarios, we begin to observe patterns in teachers' responses to the assessment scenarios, which provide initial evidence for differential approaches to assessment based on teaching context. In analyzing teachers' responses to assessment scenarios, our intention is to advance a broader theoretical argument in the field that aims to contribute toward an evolving definition of assessment literacy as a differential and negotiated competency.

The Evolution of Assessment Literacy

“Assessment literacy” is a broad term that has evolved in definition over the past three four decades. Assessment literacy was originally conceptualized as a practical professional skill and initially regarded as teachers' technical knowledge and skills in assessment, with a substantial emphasis on psychometric principles and test design (Stiggins, 1991). The 1990 Standards for Teacher Competency in Educational Assessment of Students [American Federation of Teachers (AFT) et al., 1990], which articulated a set of practices for teacher assessment practice, represented test-based and psychometric approaches to classroom assessment with implications for diagnostic and formative purposes. These Standards highlighted teachers' skills in (a) choosing and developing appropriate assessment methods for instructional purposes; (b) administering, scoring, and interpreting assessment results validly; (c) using assessment results to evaluate student learning, instructional effectiveness, school and curriculum improvement; (d) communicating assessment results to students, parents, and relevant stakeholders; and (e) identifying illegal, inappropriate, and unethical assessment practices. The Standards also provided the initial foundation for investigating teachers' assessment literacy, with a major focus on determining teachers' knowledge and skills in assessment through quantitative measures (e.g., Plake et al., 1993).

The largely psychometric and knowledge-driven view of assessment literacy was later expanded by scholars by drawing on contemporary shifts in classroom assessment and learning theories, which included more attention to formative assessment as well as social and theoretical aspects of assessment (Black and Wiliam, 1998a; Brookhart, 2011). Specifically, Brookhart (2011) reviewed the 1990 Standards and argued that these standards needed to respond to two current shifts: (a) a growing emphasis on formative assessment (i.e., assessment for learning), which had been shown to positively influence student learning (Black and Wiliam, 1998a; Assessment Reform Group, 2002; Earl, 2012); and (b) attention to the social, theoretical, and technical issues that teachers address in their assessment practices in relation to increasing student diversity. In addition to these recommendations, there were continued calls by other scholars to accommodate assessments to respond to cultural, linguistic, and ability-based diversity within classrooms (Klenowski, 2009; Siegel, 2014; Cowie, 2015).

In 2015, the Joint Committee for Standards on Educational Evaluation released the Classroom Assessment Standards for PreK-12 Teachers (Klinger et al., 2015). This updated set of standards propose 16 guidelines that reflected a contemporary conception of assessment literacy, where teachers exercise “the professional judgment required for fair and equitable classroom formative, benchmark, and summative assessments for all students” (p. 1). These standards guide teachers, students, and parents to leverage assessment results to not only support student learning but also screen and grade student achievement in relation to learning objectives. Accordingly, these 19 guidelines were categorized into three key assessment processes: foundations, use, and quality. Foundations characterize guidelines related to assessment purposes, designs, and preparation. Use comprises guidelines in terms of examining student work, providing instructional feedback, and reporting. Quality includes guidelines on fairness, diversity, bias, and reflection. Collectively, these Standards began to address critiques raised in relation to the 1990 Standards within a more contemporary conception of assessment literacy, which recognizes that teachers make assessment decisions based on an interplay of technical knowledge and skills as well as social and contextual elements.

The focus of previous conceptions of assessment literacy was on what teachers need to know and be able to do, as an individual characteristic, with respect to assessment knowledge and skill. Contemporary conceptions of assessment literacy recognize the importance and role of context in the capacity to develop and enact assessment knowledge and skills. Contemporary views of assessment literacy view it as a negotiated professional aspect of teachers' identities where teachers integrate their knowledge of assessment with their knowledge of pedagogy, content, and learning context (Adie, 2013; Scarino, 2013; Cowie et al., 2014; Xu and Brown, 2016; Looney et al., 2017). Willis et al. (2013, p. 242) effectively articulate this view as:

Assessment literacy is a dynamic context-dependent social practice that involves teachers articulating and negotiating classroom and cultural knowledges with one another and with learners, in the initiation, development and practice of assessment to achieve the learning goals of students.

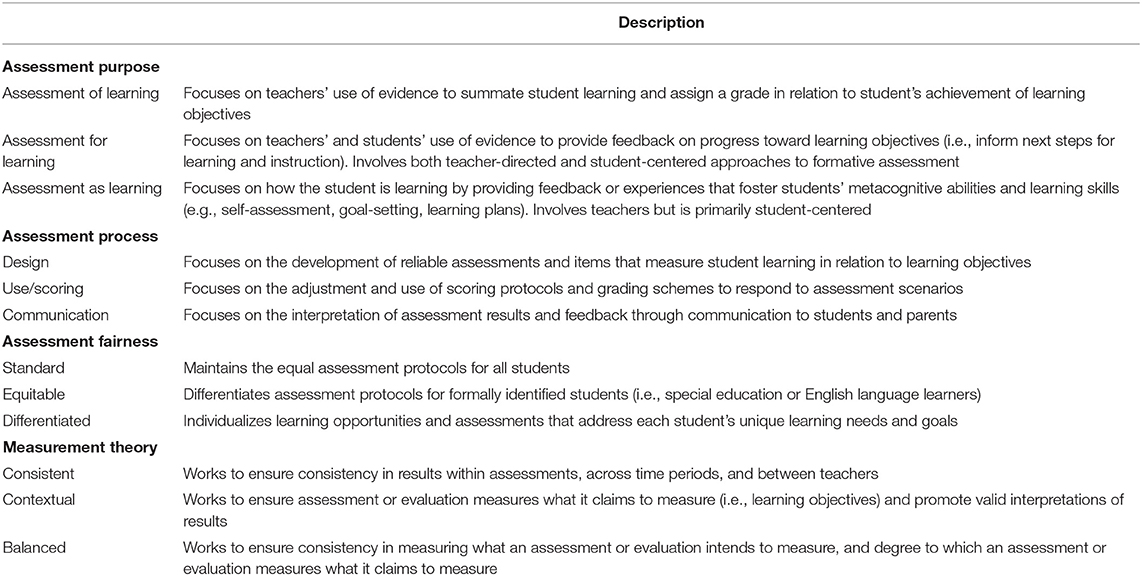

At the heart of this view of assessment is recognizing that the practice of assessment is shaped by multiple factors including teacher background, experience, professional learning, classroom context, student interactions and behaviors, curriculum, and class diversity (Looney et al., 2017), and that such factors will lead to differential experiences of assessment despite consistency in educational policies and training (Tierney, 2006). More precisely, these socio-cultural factors shape how teachers negotiate various domains of assessment practice. Following previous research (DeLuca et al., 2016a,b; Coombs et al., 2018), these assessment domains may include teachers' understandings of assessment purposes (i.e., assessment for learning, assessment as learning, and assessment of learning), assessment processes (i.e., assessment design, administration and scoring, and communication and use of results), conceptions of fairness (i.e., a standardized orientation, an equitable approach, and a fully individualized approach), and priorities with respect to assessment theory (i.e., validity or reliability). Thus, what is evident from current conceptions of assessment literacy is that the practice of assessment is not a simple one; rather, it appears that multiple socio-cultural factors influence teachers' negotiation of various assessment domains to create differential practices of assessment based on context and scenario.

Assessment Literacy Research

Drawing on a more contemporary view of assessment literacy, several scholars have taken up the challenge of researching teachers' priorities, knowledge, and approaches to assessment (e.g., Wolf et al., 1991; Delandshere and Jones, 1999; Brown, 2004; Remesal, 2011; Gunn and Gilmore, 2014; Xu and Brown, 2016; Coombs et al., 2018) or exploring teachers' enacted assessment practices (e.g., Siegel and Wissehr, 2011; Scarino, 2013; Willis and Adie, 2014; Cowie and Cooper, 2017). The majority of this research has involved understanding how teachers primarily use assessments—the purposes of their assessment practices—as related to assessment policies, theories, and dominant assessment cultures within school systems. For example, Wolf et al. (1991) distinguished between a culture of testing and a culture of assessment in regards to teachers' conceptions of assessment purposes. Within a testing culture, teachers are not just focused on instrument construction and application but also on the production and use of relative rankings of students. In contrast, within an assessment culture, teachers focus on the relationship between instruction and learning and places value on the long-term development of the student. Teacher identification with either a testing or assessment culture has been shown to have a direct impact upon their perceptions of intelligence, the relationship between teacher and learner, and the purpose of assessment instruments (Wolf et al., 1991).

Similarly, in a landmark article, Shepard (2000) mapped assessment orientations and practices to dominant historical paradigms within educational systems. Specifically, she argued that traditional paradigms of social efficiency curricula, behaviorist learning theory, and scientific measurement favor a summative testing approach to assessment, whereas a social constructivist paradigm makes provisions for a formative assessment orientation. Her argument acknowledges that previous paradigms continue to shape the actions of teachers and that contemporary conceptualizations of assessment are “likely to be at odds with prevailing beliefs” (p. 12) resulting in resistance to progressive approaches to classroom assessment.

More recently, Brown (2004) and his later work with colleagues (e.g., Harris and Brown, 2009; Hirschfeld and Brown, 2009; Brown et al., 2011) presented teachers' differential conceptions of assessment as defined by their agreement or disagreement with four purposes of assessment: (a) improvement of teaching and learning, (b) school accountability, (c) student accountability, and (d) treating assessment as irrelevant. Teachers who hold the conception that assessment improves teaching and learning would also be expected to believe that formative assessments produced valid and reliable information of student performance to support data-based instruction. Assessment as a means to hold schools accountable for student performance requires teachers to either emphasize the reporting of instructional quality within a school or changes in the quality of instruction over reporting periods. The school accountability purpose of assessment has become increasingly popular, particularly in the United States, over the past few decades with the shift in education toward a standards-based, accountability framework (Brown, 2004; Stobart, 2008; Popham, 2013). Similarly, student accountability, views the primary purpose of assessment to hold students accountable for their learning toward explicit learning targets. Brown's final conception of assessment recognizes orientations that devalue assessment as legitimate practices in classrooms. A teacher who supports this conception would most likely see assessment as a force of external accountability, disconnected from the relationship between teacher and student within the classroom (Brown, 2004).

In a later study, Brown and Remesal (2012) examined differences in the conceptions of assessments held by prospective and practicing teachers, constructing a three-conception model to explain teachers' orientations to assessment: (a) assessment improves, (b) assessment is negative, and (c) assessment shows the quality of schools and students. Interestingly, prospective teachers relied more heavily upon assessment instruments of unknown validity and reliability (i.e., observations) and did not associate improved learning with valid, dependable assessments.

Postareff et al. (2012) identified five purposes of assessment that were consolidated into two overall purpose of assessment held by classroom teachers: reproductive conceptions (i.e., measuring memorization of facts, how well students covered content, and the application of knowledge) and transformational conceptions (i.e., measuring deep understanding and measuring process and development of student thinking). A relationship between a reproductive conception of assessment and traditional assessment practices as well as a transformational conception of assessment and alternative assessment practices was also identified in this study.

Within these various conceptions of assessment, teachers enact diverse assessment practices within their classrooms. In a recent study, Alm and Colnerud (2015) examined 411 teachers grading practices, noting wide variability in how grades were constructed due to teacher's approaches to classroom assessment. For example, the way teachers developed assessments varied based on whether they used norm- or criterion-referenced grading, whether they added personal rules onto the grading policy, and whether they incorporated data from national examination into final grades. These factors, along teachers' beliefs of what constituted undependable data on student performance and how non-performance factors could be used to adjust grades, resulted in teachers enacting grading systems in fundamentally different ways.

In our own work, we have found that teachers hold significantly different approaches to assessment when considered across teaching division (DeLuca et al., 2016a) and career stage (Coombs et al., 2018) specifically, early career teachers tend to value more summative and standard assessment protocols while later career teachers endorse more formative and equitable assessment protocols. Much of the research into teachers enacted assessment practices has used a qualitative methodology involving observations and interviews, without the opportunity to consider how teachers would responds to similar and common assessment scenarios.

Our Study

In order to provide additional evidence on the differential and situated nature of assessment literacy, we invited 453 teachers to respond to a survey that presented teachers with five common classroom assessment scenarios. By survey responses, we aimed to better understand teachers' various approaches to classroom assessment with specific consideration for differences between elementary and secondary teachers.

The Teachers

Teachers who had completed their initial teacher education program at three Ontario-based universities were recruited for this study via alumni lists (i.e., convenience sample). All teachers were certified and at a similar stage of their teaching career (i.e., completed initial teacher education prior to entering starting teaching positions). All recent graduates at these institutions were sent an email invitation with link to complete the scenario-based survey and provided consent prior to completing the survey following approved research ethics protocols. The response rate for the survey was 71% (453 completed surveys out of 637 survey links that were accessed by potential participants). The 184 surveys that were accessed but not completed did not contain enough complete responses (i.e., sat least four of five scenarios) to determine if there were differences between respondents who completed the survey and those that did not. Of the respondents (i.e., 453 complete responses), the vast majority (87%) had secured work or were planning to work in the public-school system in Ontario. There was a near even split in gender at the secondary teaching division (grades 7–12), with a majority (81%) of females at the elementary teaching division (grades K−6). In total, 200 respondents represented the secondary teaching division and 253 represented the elementary division.

The Survey

An adapted version of the Approaches to Classroom Assessment Inventory (ACAI) was used in this research. The ACAI was previously developed based on an analysis of 15 contemporary assessment standards (i.e., 1990–present) from five geographic regions (see DeLuca et al., 2016b, for complete analysis of standards). From this analysis, we developed a set of themes to demarcate the construct of assessment literacy, and which aligned with the most recently published Classroom Assessment Standards from the Joint Committee for Standards on Educational Evaluation (2015). The following assessment literacy domains were integrated into the ACAI: (a) Assessment Purposes, (b) Assessment Processes, (c) Assessment Fairness, and (d) Measurement Theory. Each dimension had associated with it a set of three priority areas. For example, the three priorities associated with the assessment literacy theme of assessment purpose were: assessment of learning, assessment for learning, and assessment as learning. See Table 1 for complete list of assessment literacy domains with definitions of associated priority areas.

Scenario-based items were created for the ACAI that addressed the four assessment literacy domains. An expert-panel method was used to ensure the construct validity of the instrument followed by a pilot testing process (see DeLuca et al., 2016a for additional instrument development information). In total, 20 North American educational assessment experts followed an alignment methodology (Webb, 1997, 1999, 2005; DeLuca and Bellara, 2013) to provide feedback on the scenario items. Each expert rated (on a five-point scale) the items based on their alignment to the table of specifications and the related assessment literacy theme/priority. Based on expert feedback the scenarios were revised and amended until all items met the validation criteria (i.e., average alignment rating of 4 or more). After the alignment process, the ACAI scenarios were pilot tested with practicing teachers. The ACAI version used in this study included 20 items equally distributed across five classroom assessment scenarios with a second part that included a short collection of demographic data.

Teachers were administered an online survey that included five assessment scenarios and demographic questions. For each scenario, teachers were presented with 12 responses and asked to identify the likelihood of enacting each response using a six-point scale (1 = not at all likely; 6 = highly likely). Each dimension maintained three approach options that related to the recently published Joint Committee Classroom Assessment Standards (Klinger et al., 2015). In completing the survey, teachers were asked to consider their own teaching context when responding to each scenario (i.e., position the scenario in relation to the students they primarily taught or most recently taught).

Data Analysis

Only fully complete surveys were included in our analysis (n = 453). Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation) were calculated for responses to each action. Statistical comparisons by teaching division (primary, secondary) were conducted through the use of an independent samples t-test (α = 0.05). A Bonferroni correction was employed, with an adjusted alpha value of 0.0008 (α = 0.05/60 statistical tests) used for in this study (Peers, 1996). Cohen's d was calculated as a measure of effect size. All data analysis was completed using Statistical Program for the Social Sciences version 22 (SPSS v. 22). As our interest in this paper was to consider how teachers respond consistently and differently to the same assessment scenario, results were analyzed by scenario and by participant demographic background to determine contextual and situational differences between teachers and their approaches to assessment.

Scenario Responses

In analyzing teachers' responses, we provide overall response patterns by scenario, recognizing most likely and least likely responses in relation to various assessment approaches (see Table 1). Results are presented with consideration for both descriptive trends and significant results by teaching division (i.e., elementary and secondary). Complete results are presented in Appendices A–E with the text highlighting priority areas and differences between groups by scenario.

Scenario 1

You give your class a paper-pencil summative unit test with accommodations and modifications for identified learners. Sixteen of the 24 students fail.

In responding to this scenario, teachers prioritized an assessment for learning approach (M = 5.05, SD = 1.01), design approach (M = 4.67, SD = 1.00), and an equitable approach to fairness (M = 4.57, SD = 1.10). In practice, these responses would involve teachers re-teaching parts of the unit and giving students opportunities to apply their learning prior to re-testing the material. It also involves teachers recognizing that the test design may be flawed and that they might need to design a revised unit test to give students, in particular for those with exceptionalities. Importantly, significant differences across elementary and secondary teachers were noted for assessment for learning [t(452) = 3.68, p < 0.0008, d = 0.35], with elementary teachers favoring these approaches more than secondary teachers.

Among the least endorsed responses to this scenario were those that dealt with a summative and standardized approach to assessment. Across all teachers, the lowest scored response was to remove test questions that most students failed and re-calculate student scores without those questions (M = 2.99, SD = 1.38). Almost as low, was to record the test grade as each student's summative assessment for the unit but reduce the weight of the test in the final grade (M = 3.13, SD = 1.32). Interestingly, however, this response option showed a significant difference between elementary and secondary teachers, with secondary teachers more likely [t(452) = 4.72, p < 0.0008, d = 0.45] to endorse it. Finally, the third lowest response related to a standard approach to assessment fairness, which involved allowing all students to retake a similar test and averaging the two grades (M = 3.47, SD = 1.27).

Scenario 2

You discover that one of your students has plagiarized some of his assignment (e.g., an essay, lab report).

The results from this scenario suggest some important differences in how elementary and secondary teachers view and respond to plagiarism. Both groups of teachers highly endorsed a communicative approach (elementary M = 5.22, SD = 0.87; secondary M = 5.19, SD = 0.83) and a design approach (elementary M = 4.81, SD = 1.04; secondary M = 4.72, SD = 1.04). In practice, these approaches involve talking with students about the severity of plagiarism and negotiating potential next steps for their learning to ensure that the student learns and demonstrates their learning appropriately. Similar to the first scenario, teachers would also focus on the design of the assessment task and reflect on designing tasks that support more authentic work. Significant differences were observed in the third highest endorsed response. Secondary teachers (M = 4.97, SD = 0.94) were statistically more likely [t(363.42) = 4.67, p < 0.0008, d = 0.45] to respond to this scenario using a standard approach, which involves explaining to the student the policy on plagiarism and how it must be consistently applied to all students. Adherence to plagiarism policies for all students was further endorsed by secondary teachers in several other significant responses; specifically, those related to a consistent approach [t(452) = 4.30, p < 0.0008, d = 0.41], which involves consulting school policy on plagiarism and implement consequences consistent with the policy (elementary M = 4.04, SD = 1.18; secondary M = 4.52, SD = 1.19), and an assessment of learning approach [t(452) = 5.57, p < 0.0008, d = 0.52], which requires teachers to administer consequence in alignment with school policies (elementary M = 4.09, SD = 1.12; secondary M = 4.68, SD = 1.13).

Scenario 3

Out of 28 students in your class, 4 students are classified/identified with an exceptionality and have an Individual Education Plan (IEP) (i.e., each student requires accommodations but not a modified curriculum) as well as several other unidentified students with differentiated learning needs. You must decide how to accurately measure learning in your class.

The primary response for both elementary and secondary teachers to this scenario was an equitable approach (M = 5.11, SD = 0.97). In practice, teachers would aim to ensure students with identified learning exceptionalities were provided with accommodations on all assessment tasks, consistent with many school and jurisdictional policies on teaching learners with exceptionalities. Following this priority response, teachers endorsed a communication approach (M = 5.06, SD = 0.93), where teachers would explain to students and parents the purpose of accommodations and how they would be implemented and communicated on report cards.

Among the lowest scored responses were a contextualized approach in which teachers would develop different scoring rubrics for identified students (M = 3.94, SD = 1.25) and a standard approach in which teachers would grade students (without accommodations) based on the same assessments (M = 3.52, SD = 1.35). Interestingly, while not widely endorsed, elementary teachers (M = 4.32, SD = 1.07) tended to significantly prioritize a contextual approach (i.e., still within the “likely” response category) more than secondary teachers [M = 3.63, SD = 1.31; t(397.06) = 3.27, p < 0.0008, d = 0.58]. Furthermore, secondary teachers (M = 3.88, SD = 1.31) tended to significantly prioritize a standard approach more than elementary teachers [M = 3.06, SD = 1.25; t(452) = 6.78, p < 0.0008, d = 0.64]. The lowest ranked response reflected a consistent approach in which teachers would use the same scoring rubric for all students in their class, with secondary teachers statistically more likely to enact this response [elementary M = 2.98, SD = 1.25; secondary M = 3.90, 1.35; t(439.67) = 7.54, p < 0.0008, d = 0.71].

Scenario 4

You are planning a unit for your class.

The top three responses to this scenario suggest that teachers base their assessments on the taught curriculum content, enacted pedagogical activities, and co-constructed learning goals with students. Teachers were most likely to use a contextual response to this scenario in which they developed assessments based on the context and activities of their enacted lessons (M = 5.12, SD = 0.79). Teachers also endorsed a balanced approach in which they would develop assessments based on questions and activities that worked well with other students but adjusted them to the content and pedagogies used in their enacted lessons (M = 4.90, SD = 0.90). Using assessments to guide unit planning was highly endorsed by teachers. Again, standard and consistent approaches were the two lowest ranked responses to this scenario; however, secondary teachers (M = 4.15, SD = 1.24) responded with a standard response more than elementary teachers [M = 3.42, SD = 1.12; t(452) = 6.42, p < 0.0008, d = 0.62].

Scenario 5

A parent of one of your classified/identified students is concerned about an upcoming standardized test.

This assessment scenario requires teachers to consider their orientation to large-scale testing, assessment of students with exceptionalities, and their approach to communicating with parents. The priority response for both elementary and secondary teachers was an equitable approach (M = 5.26, SD = 0.91). Across both divisions, teachers would tell the parent that her child's IEP would be consulted prior to the test and that appropriate accommodations would be provided, congruent with the IEP. The next set of highly endorsed responses included a differentiated approach (M = 4.89, SD = 1.14), design approach (M = 4.80, SD = 1.06), and communicative approach (M = 4.53, SD = 1.14). These responses suggest that teachers aim to articulate the purpose, role, and influence of the standardize test on students' learning and grades. They are sensitive to the limitations of standardized assessments and equally demonstrate the value of classroom-level data to provide more nuanced information about student learning.

Among the lowest-endorsed responses was an assessment for learning approach, in which teachers would tell the parent that the standardized test would provide feedback on her child's learning toward educational standards and help guide teaching and learning (M = 4.07, SD = 1.28) and a balanced approached (M = 3.89, SD = 1.39). For this scenario, a balanced approach involved teachers telling the parent that standardized tests, in conjunction with report card grades, allow parents to draw more informed conclusions about their child's growth and achievement than either source can provide alone. A significant difference between elementary and secondary teachers was their endorsement of a standard response where teachers would tell the parent that all eligible students in the class must complete the standardized test [elementary M = 3.85, SD = 1.45; secondary M = 4.49, SD = 1.23; t(452) = 4.98, p < 0.0008, d = 0.48]. This significant difference might point to a difference in orientation toward the role of standardized testing between elementary and secondary teachers and may warrant further investigation.

Implications for Assessment Literacy

Much of the assessment research to date has investigated teachers' understandings of assessment purposes (e.g., Brown, 2004; Barnes et al., 2017), teachers' developing assessment literacy (Brown, 2004; DeLuca et al., 2016a; Coombs et al., 2018; Herppich et al., 2018), or specific classroom assessment practices (Cizek et al., 1995; Cauley and McMillan, 2010). Few studies have explored teachers' differential responses to specific and common classroom assessment scenarios to substantiate contemporary conceptions of assessment literacy as a situated and differential practice predicated on negotiated knowledges (Willis et al., 2013; Looney et al., 2017). Stemming from the assumption that teachers' assessment actions have significant influence on students' learning experience and achievement (Black and Wiliam, 1998b; Hattie, 2008; DeLuca et al., 2018), there is a need to understand how teachers are approaching assessment similarly or differently across grades, classrooms, and teaching contexts. In this study, we presented beginning teachers with five common classroom assessment scenarios and asked them to consider their own teaching context while identifying their likely response to the scenarios using a multi-dimensional framework to classroom assessment actions.

While, we recognize that this is a small-scale study reliant on one data source, we argue that it does provide additional evidence to further conceptualizations of assessment literacy as both situated and differential across teachers. What we see from this study is that in relation to classroom assessment scenarios, teachers have apparent consistency—a core value toward student learning that guides their assessment practice—but also significant instances of difference, which translate to differences in teacher actions in the classroom. For example, secondary teachers endorsed a standard approach to fairness significantly more than elementary teachers within scenarios 2, 3, 4, and 5. Differences in how teachers respond to common assessment scenarios is important as it suggests that students potentially experience assessment quite differently across teachers despite the presence of consistent policies and similar professional learning backgrounds (Coombs et al., 2018). While these differences may not be problematic, and may in fact be desirable in certain instances (e.g., there might be good justification for changing a response to an assessment scenario between elementary and secondary school contexts), they do support the notion of a differential and situated view of teachers' classroom assessment practices.

We recognize that differences observed between teachers might be due to a complexity of factors, including teaching division, class, and personal characteristics and dispositions, that interact as teachers negotiate assessment scenarios in context. What this amounts to, is the recognition that there are other factors shaping teachers' assessment actions in the classroom. In working toward an expanded view of assessment literacy that moves beyond strictly a psychological trait (i.e., cognitive learning of assessment knowledge and skills) to an always situated and differential professional responsibility resulting from teachers negotiating diverse factors at micro-levels (e.g., teachers' beliefs, knowledge, experience, conceptions, teacher diversity), meso-levels (i.e., classroom and school beliefs, polices, practices, student diversity), and macro-levels (i.e., system assessment policies, values, protocols) (Fulmer et al., 2015). Adopting a situated and differential view of assessment literacy where classroom assessment is shaped by a negotiation of personal and contextual factors holds important implications for how teachers are supported in their assessment practices. Firstly, like effective pedagogies, classroom assessment will not look the same in each classroom. While teachers may uphold strong assessment theory, the way in which that theory is negotiated amid the complex dynamics of classroom teaching, learning, and diversity and in relation to school and system cultures of assessment will yield differences in assessment practice. Second, as teachers' assessment practices are to some extent context-dependent (Fulmer et al., 2015), teachers may shift their practices as they work across different teaching contexts (i.e., grades, subjects, schools) or in relation to different students. Finally, what this expanded view of assessment literacy suggests, is that learning to assess is a complex process that involves negotiating evolving assessment knowledge alongside other evolving pedagogical knowledges, socio-cultural contexts of classroom teaching and learning, and system priorities, policies, and processes (Willis et al., 2013).

In considering research stemming from this and other recent assessment literacy studies, we suggest additional empirical investigations to explore the role of various influencing factors that shape teachers' decision-making processes within classroom assessment scenarios. In particular, future research should also address the limitations of the present study; namely, (a) that the sample was drawn from one educational jurisdiction, (b) that the data involved a self-report scale of intended actions rather than observed actions, and (c) that teachers in this study were all new to the profession. Future studies should consider both reported and enacted practices across a wide range of teachers and contexts with purposeful attention to the factors that shape their situated and differential approach to classroom assessment.

Data Availability

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of Queen's General Research Ethics Board with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Queen's General Research Ethics Board.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the intellectual development of this paper. The author order reflects the contributions made by each author to this paper.

Funding

Funding provided by Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, Grant# 430-2013-0489.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2019.00094/full#supplementary-material

Footnote

1. ^Depending on the national context, the term “teaching division” should be considered synonymous with school levels and/or educational levels, all of which are used to denote grades a teacher instructs.

References

Adie, L. (2013). The development of teacher assessment identity through participation in online moderation. Assess. Educ. 20, 91–106. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2011.650150

Alm, F., and Colnerud, G. (2015). Teachers' experiences of unfair grading. Educ. Assess. 20, 132–150. doi: 10.1080/10627197.2015.1028620

American Federation of Teachers (AFT) National Council on Measurement in Education (NCME) and National Education Association (NEA). (1990). Standards for teacher competence in educational assessment of students. Educ. Measure. 9, 30–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3992.1990.tb00391.x

Assessment Reform Group (2002). Assessment for Learning: 10 Principles. London: University of Cambridge.

Barnes, N., Fives, H., and Dacey, C. M. (2017). US teachers' conceptions of the purposes of assessment. Teach. Teach. Educ. 65, 107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.02.017

Bennett, R. E., and Gitomer, D. H. (2009). “Transforming K-12 assessment: Integrating accountability, testing, formative assessment and professional support,” in Educational Assessment in the 21st Century: Connecting Theory and Practice, eds C. Wyatt-Smith and J. J. Cumming (Dordrecht: Springer), 43–61. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-9964-9_3

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (1998a). Assessment and classroom learning. Assess. Educ. 5, 7–74. doi: 10.1080/0969595980050102

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (1998b). Inside the Black Box: Raising Standards Through Classroom Assessment. London: GL Assessment.

Brookhart, S. M. (2008). How to Give Effective Feedback to Your Students. Alexandria, VA: Association of Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Brookhart, S. M. (2011). Educational assessment knowledge and skills for teachers. Educ. Measure. 30, 3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3992.2010.00195.x

Brookhart, S. M. (2015). Graded achievement, tested achievement, and validity. Educ. Assess. 20, 268–296. doi: 10.1080/10627197.2015.1093928

Brookhart, S. M., Guskey, T. R., Bowers, A. J., McMillan, J. H., Smith, J. K., Smith, L. F., et al. (2016). A century of grading research: meaning and value in the most common educational measure. Rev. Educ. Res. 86, 803–848. doi: 10.3102/0034654316672069

Brown, G. T., Hui, S. K., Flora, W. M., and Kennedy, K. J. (2011). Teachers' conceptions of assessment in Chinese contexts: a tripartite model of accountability, improvement, and irrelevance. Int. J. Educ. Res. 50, 307–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2011.10.003

Brown, G. T., and Remesal, A. (2012). Prospective teachers' conceptions of assessment: a cross-cultural comparison. Span. J. Psychol. 15, 75–89. doi: 10.5209/rev_SJOP.2012.v15.n1.37286

Brown, G. T. L. (2004). Teachers' conceptions of assessment: implications for policy and professional development. Assess. Educ. 11, 301–318. doi: 10.1080/0969594042000304609

Cauley, K. M., and McMillan, J. H. (2010). Formative assessment techniques to support student motivation and achievement. Clear. House 83, 1–6. doi: 10.1080/00098650903267784

Cizek, G. J., Fitzgerald, S. M., and Rachor, R. A. (1995). Teachers' assessment practices: preparation, isolation, and the kitchen sink. Educ. Assess. 3, 159–179. doi: 10.1207/s15326977ea0302_3

Coombs, A. J., DeLuca, C., LaPointe-McEwan, D., and Chalas, A. (2018). Changing approaches to classroom assessment: an empirical study across teacher career stages. Teach. Teach. Educ. 71, 134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.12.010

Cowie, B. (2015). “Equity, ethics and engagement: principles for quality formative assessment in primary science classrooms,” in Sociocultural Studies and Implications for Science Education, eds C. Milne, K. Tobin, and D. DeGennaro (Dordrecht: Springer), 117–133. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-4240-6_6

Cowie, B., and Cooper, B. (2017). Exploring the challenge of developing student teacher data literacy. Assess. Educ. 24, 147–163. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2016.1225668

Cowie, B., Cooper, B., and Ussher, B. (2014). Developing an identity as a teacher-assessor: three student teacher case studies. Assess. Matters 7, 64–89. Available online at: https://www.nzcer.org.nz/nzcerpress/assessment-matters/articles/developing-identity-teacher-assessor-three-student-teacher

Delandshere, G., and Jones, J. H. (1999). Elementary teachers' beliefs about assessment in mathematics: a case of assessment paralysis. J. Curric. Superv. 14:216.

DeLuca, C., and Bellara, A. (2013). The current state of assessment education: aligning policy, standards, and teacher education curriculum. J. Teach. Educ. 64, 356–372. doi: 10.1177/0022487113488144

DeLuca, C., LaPointe-McEwan, D., and Luhanga, U. (2016a). Approaches to classroom assessment inventory: A new instrument to support teacher assessment literacy. Educ. Assess. 21, 248–266. doi: 10.1080/10627197.2016.1236677

DeLuca, C., LaPointe-McEwan, D., and Luhanga, U. (2016b). Teacher assessment literacy: a review of international standards and measures. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 28, 251–272. doi: 10.1007/s11092-015-9233-6

DeLuca, C., Valiquette, A., Coombs, A. J., LaPointe-McEwan, D., and Luhanga, U. (2018). Teachers' approaches to classroom assessment: a large-scale survey. Assess. Educ. 25, 355–375. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2016.1244514

Earl, L. M. (2012). Assessment as Learning: Using Classroom Assessment to Maximize Student Learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Fulmer, G. W., Lee, I. C. H., and Tan, K. H. K. (2015). Teachers' assessment practices: an integrative review of research. Assess. Educ. 22, 475–494. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2015.1017445

Gardner, J. (2006). “Assessment for learning: a compelling conceptualization,” in Assessment and Learning, ed. J. Gardner (London: Sage, 197–204.

Gilboy, M. B., Heinerichs, S., and Pazzaglia, G. (2015). Enhancing student engagement using the flipped classroom. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 47, 109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2014.08.008

Gunn, A. C., and Gilmore, A. (2014). Early childhood initial teacher education students' learning about assessment. Assess. Matters 7, 24–38. Available online at: https://www.nzcer.org.nz/nzcerpress/assessment-matters/articles/early-childhood-initial-teacher-education-students-learning

Guskey, T. R. (2000). Grading policies that work against standards…and how to fix them. NASSP Bull. 84, 20–29. doi: 10.1177/019263650008462003

Harlen, W. (2006). “On the relationship between assessment for formative and summative purposes,” in Assessment and Learning, ed. J. Gardner (Los Angeles, CA: Sage), 87–103. doi: 10.4135/9781446250808.n6

Harris, L. R., and Brown, G. T. L. (2009). The complexity of teachers' conceptions of assessment: tensions between the needs of schools and students. Assess. Educ. 16, 365–381. doi: 10.1080/09695940903319745

Hattie, J. (2008). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203887332

Herman, J. L. (2008). “Accountability and assessment: Is public interest in K-12 education being served?,” in The Future of Test-Based Educational Accountability, eds K. E. Ryan and L. A. Shepard (New York, NY: Routledge, 211–231.

Herppich, S., Praetoriusm, A., Forster, N., Glogger-Frey, I., Karst, K., Leutner, D., et al. (2018). Teachers' assessment competence: integrating knowledge-, process-, and product-oriented approaches into a competence-oriented conceptual model. Teach. Teach. Educ. 76, 181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.12.001

Hirschfeld, G. H., and Brown, G. T. (2009). Students' conceptions of assessment: factorial and structural invariance of the SCoA across sex, age, and ethnicity. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 25, 30–38. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759.25.1.30

Klenowski, V. (2009). Australian Indigenous students: addressing equity issues in assessment. Teach. Educ. 20, 77–93. doi: 10.1080/10476210802681741

Klinger, D. A., McDivitt, P. R., Howard, B. B., Munoz, M. A., Rogers, W. T., and Wylie, E. C. (2015). The Classroom Assessment Standards for PreK-12 Teachers. Kindle Direct Press.

Looney, A., Cumming, J., van Der Kleij, F., and Harris, K. (2017). Reconceptualising the role of teachers as assessors: teacher assessment identity. Assess. Educ. 25, 442–467. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2016.1268090

MacLellan, E. (2004). Initial knowledge states about assessment: novice teachers' conceptualizations. Teach. Teach. Educ. 20, 523–535. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2004.04.008

McMillan, J. H. (2017). Classroom Assessment: Principles and Practice That Enhance Student Learning and Motivation. New York, NY: Pearson.

Plake, B., Impara, J., and Fager, J. (1993). Assessment competencies of teachers: a national survey. Educ. Measure. 12, 10–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3992.1993.tb00548.x

Popham, W. J. (2013). Classroom Assessment: What Teachers Need to Know, 7th Edn. Boston, MA: Pearson.

Postareff, L., Virtanen, V., Katajavuori, N., and Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2012). Academics' conceptions of assessment and their assessment practices. Stud. Educ. Eval. 38, 84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2012.06.003

Remesal, A. (2011). Primary and secondary teachers' conceptions of assessment: a qualitative study. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 472–482. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.09.017

Scarino, A. (2013). Language assessment literacy as self-awareness: understanding the role of interpretation in assessment and in teacher learning. Lang. Test. 30, 309–327. doi: 10.1177/0265532213480128

Shepard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educ. Res. 29, 4–14. doi: 10.3102/0013189X029007004

Siegel, M. A. (2014). Developing preservice teachers' expertise in equitable assessment for English learners. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 25, 289–308. doi: 10.1007/s10972-013-9365-9

Siegel, M. A., and Wissehr, C. (2011). Preparing for the plunge: preservice teachers' assessment literacy. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 22, 371–391. doi: 10.1007/s10972-011-9231-6

Stobart, G. (2008). Testing Times: The Uses and Abuses of Assessment. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203930502

Tierney, R. D. (2006). Changing practices: influences on classroom assessment. Assess. Educ. 13, 239–264. doi: 10.1080/09695940601035387

Volante, L., and Fazio, X. (2007). Exploring teacher candidates' assessment literacy: implications for teacher education reform and professional development. Can. J. Educ. 30, 749–770. doi: 10.2307/20466661

Webb, N. L. (1997). Criteria for Alignment of Expectations and Assessments in Mathematics and Science Education. Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School Officers.

Webb, N. L. (1999). Alignment of Science and Mathematics Standards and Assessments in Four States. Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School Officers.

Webb, N. L. (2005). Webb Alignment Tool: Training Manual. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Center for Education Research. Retrieved from: http://www.wcer.wisc.edu/WAT/index.aspx (Retrieved March 27, 2017).

Willis, J., and Adie, L. (2014). Teachers using annotations to engage students in assessment conversations: recontextualising knowledge. Curric. J. 25, 495–515. doi: 10.1080/09585176.2014.968599

Willis, J., Adie, L., and Klenowski, V. (2013). Conceptualising teachers' assessment literacies in an era of curriculum and assessment reform. Austr. Educ. Res. 40, 241–256. doi: 10.1007/s13384-013-0089-9

Wolf, D., Bixby, J., Glenn, I. I. I. J, and Gardner, H. (1991). Chapter 2: to use their minds well: investigating new forms of student assessment. Rev. Res. Educ. 17, 31–74. doi: 10.3102/0091732X017001031

Keywords: assessment literacy, classroom assessment, approaches to assessment, educational assessment, teacher practice, assessment scenarios

Citation: DeLuca C, Coombs A, MacGregor S and Rasooli A (2019) Toward a Differential and Situated View of Assessment Literacy: Studying Teachers' Responses to Classroom Assessment Scenarios. Front. Educ. 4:94. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00094

Received: 27 April 2019; Accepted: 19 August 2019;

Published: 03 September 2019.

Edited by:

Sarah M. Bonner, Hunter College (CUNY), United StatesReviewed by:

Ana Remesal, University of Barcelona, SpainJana Groß Ophoff, University of Tübingen, Germany

Copyright © 2019 DeLuca, Coombs, MacGregor and Rasooli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christopher DeLuca, Y2RlbHVjYUBxdWVlbnN1LmNh

Christopher DeLuca

Christopher DeLuca Andrew Coombs

Andrew Coombs Stephen MacGregor

Stephen MacGregor Amirhossein Rasooli

Amirhossein Rasooli