- Centre for Inclusive Education, Department of Psychology and Human Development, UCL Institute of Education, London, United Kingdom

The Special Educational Needs Coordinator (SENCO) role in England has been formally established since 1994 to support inclusion. In 2009 it became mandatory for every new SENCO in a mainstream school in England to gain a postgraduate qualification in special educational needs coordination within 3 years of taking up a post, which includes a compulsory practitioner research component. This study examined 100 assignment abstracts from 50 SENCOs submitted as part of the postgraduate qualification delivered in one university in England between 2015 and 2017. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis in Nvivo and yielded 4 themes underpinning SENCO practice, namely diversity in SENCO practice, meaningful assessment, evidence informed practice, and evaluating impact. The findings are discussed in the light of developments in policy and practice in the education of pupils with special educational needs and/or disabilities since the Warnock Report in 1978.

Introduction

Estimating prevalence rates for children with special educational needs and/or disabilities (SEND) internationally is highly problematic due to the substantial cross country variation in defining, measuring and identifying SEND (World Health Organization World Bank, 2011). As an illustration of these challenges, the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, using data from 30 countries from across Europe in 2012–2013, found that SEND identification rates ranged from 1.11 to 17.47% with the total average for the 30 countries as 4.53% (European Agency for Special Needs Inclusive Education, 2017). In England, where national SEND data is recorded annually, the most recent statistical survey reported that 14.6% of all school pupils as of January 2018 were identified as receiving some form of additional support in school as a consequence of being identified with a SEND (Department for Education, 2018a). Moderate learning difficulties (21.6%) were recorded as the most common primary type of need overall, more males (14.7%) were in receipt of support than girls (8.2%) and pupils with SEND were more likely to be eligible for free school meals: 25.8% compared to 11.5% of all pupils in school.

Whatever the challenges might be of establishing robust comparative prevalence SEND data internationally, disability has been identified as one of the most influential factors in educational marginalization (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2010). In England, results in national examinations at age 16 show there was a difference of 27.1 points between the average Attainment 8 score for all young people (M = 49.5) and pupils with SEND (M = 22.4) (Department for Education, 2018b). Moreover, data from national and international large-scale longitudinal studies indicate that the transition to adulthood is a more precarious path for today's young people compared with previous generations (Schoon and Lyons-Amos, 2016) and for young adults with a disability, inequalities in post school education and employment outcomes continue to persist. In the United Kingdom, for example, there is a gap of 18.3 percentage points between the employment rate of young people with and without a disability aged 16–24 (Parkin et al., 2018). Across the countries of the European Union, young people with disabilities are twice as likely to be not in employment, education, or training (NEET) compared with their peers without a disability (Eurostat Statistics Explained, 2018). Recent data in labor market trends from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) reported that the average employment gap for disadvantaged groups is 24.9% (ranging from 50.3% in South Africa to 9.2% in Iceland) (OECD, 2018). Against such a backdrop of disparities in outcomes, it is essential that national and international policy continues to address the education of children with SEND.

Education of Children and Young People With Special Needs and/or Disabilities: National and International Policy Context

At the time of the publication of the Warnock Report in 1978, 4 years after the appointment of the Committee, the authors, cognisant that there might not be a review of such a scale in the UK for some time, stated that, “Our perspective therefore reaches to the end of the century and possibly beyond” (Warnock, 1978, p. 325). The Committee was aware that some of the recommendations came with potential shortcomings. “We have found ourselves on the horns of a dilemma,” was, for example, how they described the process of addressing the challenge of ensuring that the required resources were made available to children but in a way that did not “emphasize the idea of separateness” (Warnock, 1978, p. 45). The final recommendation was the allocation of a statement of SEN. This was the system of recording the profile of a child and the additional resources and/or provision required based on a multi-professional assessment that the Local Authority (LA) agreed to and was statutorily obliged to meet. The limitations and often negative consequences of this recommendation in the report and others such as the use of the term “special need,” a “special or modified” curriculum and a lack of attention to teaching and learning have been well-documented (Lewis and Vulliamy, 1980; Barton and Oliver, 1992; Visser, 2018). Moreover, subsequent legislation in England relating to SEND attempted to address many of these limitations with varying degrees of success (Farrell, 2001; Norwich and Eaton, 2015).

Despite the well-known limitations of elements of the Warnock Report, evident for many at the time and subsequently, it is possible to identify principles within the report that have contributed, in no small part, to the direction of progress regarding more inclusive approaches in education in the UK and beyond 40 years later. Four principles in the report are of particular significance. Firstly, the right of a child with SEND to an education as opposed to their education viewed as a form of charitable act. Secondly, the importance of early and effective identification and ongoing educational assessment of children. Thirdly, the recognition of parents as partners in the education of their child. Finally, the need for all teachers, including student teachers and school senior leaders, to take part in learning and development opportunities, including additional qualifications where appropriate, to be able to respond to the “diversity of school populations” as described in the report. Evidence that supports the longevity of these principles can be found nationally in UK policy related to education such as Excellence for All 1997, SEN Code of Practice 2001, SEND Code of Practice 2015 (Department for Education Employment, 1997; Department for Education Skills, 2001; Department for Education, 2015), policies which are pertinent only to some parts of the UK as there are differences in the educational policy context in Scotland. Internationally, many of these principles are fundamental to the 1994 UNESCO Salamanca Statement and more recently in the United States with the Every Student Succeeds Act 2015 (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 1994; US Department of Education, 2015).

The SENCO Role in English Schools

It is a statutory requirement for every mainstream school in England to appoint a special educational needs coordinator (SENCO) whose main duty is to have day-to-day responsibility for the operation of the SEND policy and the specific provision required to support pupils with SEND. The Code of Practice 2015 stipulates 11 specific duties of the SENCO role. Although the Warnock Report did recommend “that the head teacher should normally delegate day-to-day responsibility for making arrangements for children with special needs to a designated specialist teacher or head of department” (Warnock, 1978, p. 109), the SENCO role in England was first established as part of the 1994 SEN Code of Practice (Department for Education, 1994). In subsequent reviews of the Code of Practice (2001 and 2015), a fundamental development in the role of the SENCO has been in the transition from essentially a coordination role in 1994 to that of determining the strategic direction of SEND policy and provision in school, along with the head teacher and governing body. In the Code of Practice 2015, it was recommended that the SENCO be a member of the senior leadership team in order to support the SENCO's strategic responsibility. A second development was the introduction of legislation in 2008 which stated that anyone taking up the role of SENCO must be a qualified teacher and that any SENCO appointed after 1 September 2009 was required to gain the Masters-level National Award in SEN Coordination within 3 years of taking up the position. The Warnock Committee, in 1978, had also recognized the need for additional training for the SENCO role.

To date, the main focus of research concerned with SENCOs has focused on their role and in particular the disparity between how the role is described in policy and the reality in practice. Studies investigating the challenges encountered by SENCOs in undertaking their duties have identified a lack of time, resources, and influence and/or seniority as the principal challenges (Tissot, 2013; Qureshi, 2014; Pearson et al., 2015; Done et al., 2016). Moreover, although the requirement to complete the National Award in SEN Coordination has brought benefits, such as building confidence and allowing for opportunities to integrate theory and practice (Griffiths and Dubsky, 2012; Passy et al., 2017), the demands of a qualification when embarking on a new role, often in a new school, can be challenging. Research on the perspectives of SENCOs beyond their role is less evident but has been gathered, for example, on subjects such as engaging with parents and SENCO views on the most recent Code of Practice 2015 (Maher, 2016; Curran et al., 2017). There has been limited research attention given to their practice in supporting teaching and learning and wider school development.

The Study

The current study sought to investigate the practice of 50 SENCOs as identified through 100 assignment abstracts completed as part of the National Award in SEN Coordination programme delivered by one university in England between 2015 and 2017. The abstracts were a novel way to investigate SENCO practice in 50 settings. The purpose of the study was to identify any common principles that underpinned SENCO practice. Such a study is important for three reasons. It contributes to a greater understanding of the SENCO role at operational and strategic levels, 10 years after appointing a qualified SENCO was made mandatory in English schools. Secondly, the study speaks to how schools are prioritizing SEND in their settings and, thirdly, in doing so illuminates the impact of SEND and inclusion policy more broadly in schools since the Warnock Report in 1978.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedures

The 100 abstracts for the study were submitted by 50 newly appointed or aspiring SENCOs (F = 46, M = 4) as part of their assignment submission on the National Award for SEN Coordination taken at a university in England between 2015 and 2017. The majority of SENCOs (N = 40) taught in primary settings, nine in secondary and one in a further education setting.

As part of the assessment, the Award required SENCOs to submit two 5,000-word assignments. The first assignment had a focus on supporting the teaching and learning of pupils with SEN and/or disabilities and the second an emphasis on strategic leadership of SEND provision. Both assignments required students to adopt a practitioner enquiry approach which meant that SENCOs were able to investigate a subject that was relevant to and a priority for their setting. A structured abstract framework was provided for the SENCOs to complete and submit with their assignments. The project followed the British Educational Research Association's (BERA) guidelines and received ethics approval from UCL Institute of Education (British Educational Research Association (BERA), 2011). Informed written consent was obtained from all participants. Both authors teach on the National Award for SEN coordination programme at the university.

Data Analysis

The study used a thematic approach to analysis following (Braun and Clarke, 2006) six stages: familiarization with the data; generation of codes; searching and reviewing of themes; defining and naming themes and the production of a written account. An inductive approach to the process of coding data was adopted as the study was seeking to generate rather than test theory. Stage 1 involved both authors reading the abstracts to become more acquainted with the data. For stage 2, a provisional list of codes (N = 134) was created by the authors to begin the first level of coding. After the first analysis, the authors reduced the list of codes to one hundred. This list formed the coding framework for the abstracts (stage 3). The abstracts were coded using Nvivo. The next two stages, the searching and reviewing of codes and themes, entailed the analysis and identification of the relationship between the codes into organizing themes and finally four global themes (Attride-Stirling, 2001). The analysis and interpretation of the data was at the latent level, as the authors were seeking to identify the underlying ideas and concepts that characterized SENCO practice. These four themes were used to frame the writing of the findings in response to the research aims. An 89% inter-rater agreement was established on the examination of a 20% sample of the abstracts.

Results

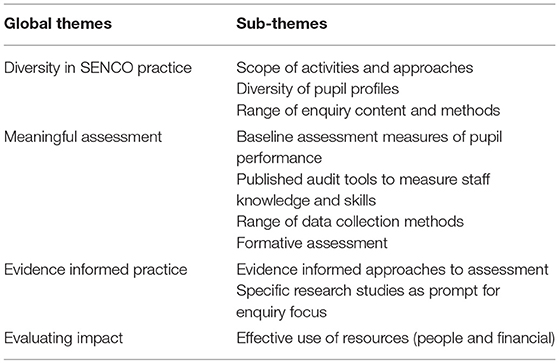

Four main themes underpinning the practice of SENCOs were evident from the abstracts: diversity in SENCO practice; meaningful assessment; evidence informed practice and evaluating impact. Each theme is addressed in turn.

Theme 1: Diversity in SENCO Practice

Diversity in practice was a fundamental principle that underpinned the practice of the SENCOs in the study. This diversity was evident not only in the scope of their activities but was also a reflection of the range of pupils and practitioners they advocated for and supported. Specifically, the abstract analysis showed diversity in the profiles of pupils, enquiry content and the methods deployed to ultimately improve the learning experiences and outcomes of pupils with SEN and/or disabilities.

Pupils from all 4 broad categories of need set out in the SEND Code of Practice 2015 were represented in the abstracts. Pupils who experienced differing literacy difficulties (N = 15/50) were the most common group of pupils reported, followed by pupils with speech, language and communication needs (SLCN) (N = 13/50), social, emotional and mental health needs (SEMH) (N = 9/50) and autism (N = 5/50). In some abstracts, SENCOs did not use a category label, but focused on cognitive skills such as working memory or learning “behaviors” including attitudes to learning and developing greater independence with learning. The analysis of the second assignment abstracts, which required SENCOs to conduct a practitioner research study on a wider school priority, showed that specific groups of pupils were also included such as, whole school approaches to “behavior for learning” with an emphasis on supporting pupils with SEMH needs.

Diversity of SENCO practice could also be seen from the number and range of activities and approaches adopted by SENCOs to address priorities in their settings. These activities fell into three main categories. The first category was working with or supporting other practitioners with small group teaching and learning activities. The subjects of these groups included, for example, literacy activities, language development social skills and SEMH. The majority of these groups were designed for a set period of weeks and sessions per week depending on the topic, aims, and profiles of the pupils concerned. For more than half of these groups, SENCOs and practitioners developed the programmes and materials based on the class curriculum and other available resources in school. The commercial programmes cited and adopted included Attention Autism (Watson et al., 2017), Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) (Bondy and Frost, 1994) and Colorful Semantics (Bryan A., 1997):

“The results showed that some children were beginning to make progress using Colorful Semantics independently and were able to have less adult input than in week one.”

Primary SENCO

The second category was leading and delivering inclusive education approaches outside the formal curriculum, such as implementing structured break time and lunch sessions, setting up a homework club and transition:

“The research will focus on between year transition due to the school's absence of guidelines on transition processes. Three-year trends have identified pupils with SEN and/or disabilities make slower progress in the autumn term compared to the spring and summer.”

Primary SENCO

Leading school wide learning and professional development for all practitioners was a third category. Different methods were used including the delivery of whole school INSET on topics such as the preparedness, deployment and practice of Teaching Assistants (TAs), differentiation, behavior for learning, High Quality Teaching (HQT) in the classroom for pupils with SEN and/or disabilities and specific categories of need such as autism. SENCOs also used coaching and mentoring approaches either in small groups or individually to support colleagues. Table 1 presents the themes underpinning SENCO practice.

Theme 2: Meaningful Assessment

Meaningful assessment practices were evident in the activities undertaken by SENCOs and were demonstrated in three ways. Firstly, baseline measures of pupil and staff knowledge and skills were taken prior to the implementation of interventions and plans to improve pupil and staff performance. A broad range of pupil assessment measures were taken using a number of published standardized and criterion-referenced tests, supplemented by existing school assessment data. The range of measures were used to create a more meaningful, holistic picture of pupils' strengths and needs. One SENCO explained how individual pupil needs:

“…were assessed using pre-and post-intervention baseline measurements which included the Single Word Spelling Test, initial teacher feedback and the Diagnostic Grammar, Punctuation and Spelling writing sample.”

Primary SENCO

The meaningful assessment and baselining of strategic school practice was also present in the SENCO abstracts, with one SENCO describing how a:

“…baseline of staff awareness was gathered through a training matrix, qualitative data from interviews with staff … data collected from observations.”

Secondary SENCO

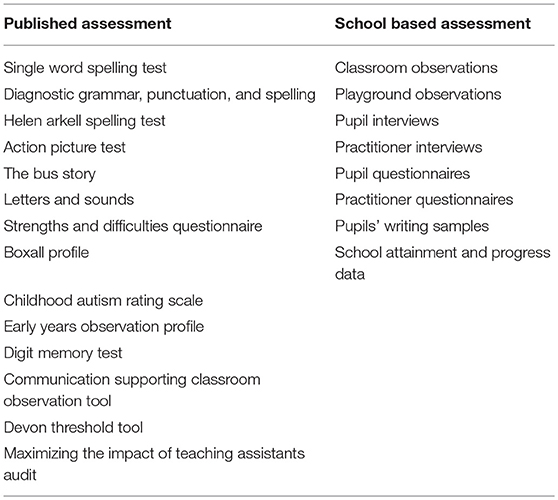

The most common area of need that was assessed using published assessments was Cognition and Learning, with the greatest focus on literacy difficulties. The literacy assessments used included the Helen Arkell Spelling Test (Caplan et al., 2012), Single Word Spelling Test (Sacre and Masterson, 2007), Action Picture Test (Renfrew, 2003) and The Bus Story (Renfrew, 1991). It was also common for SENCOs to use a range of widely available phonics screeners and high frequency word lists including Letters and Sounds (Department for Children Schools Families, 2007). In the area of emotional and behavioral well-being, pupils were assessed using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 1997) and the Boxall Profile (Bennathan and Boxall, 1998). The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (Schopler et al., 2002) and the Early Years Autism Observation Profile (Cumine et al., 2009) were used to assess the communication and interaction skills of pupils with autism. Barriers to learning not related to a specific category label such as working memory difficulties, identified through classroom observation, were measured using assessments including the Digit Memory Test (Turner and Ridsdale, 2004) and the Working Memory Rating Scale (Alloway et al., 2008). A range of evidence-informed published audit tools were used as a means of capturing existing practices. These included the Communication Supporting Classroom Observation Tool (Dockrell et al., 2012) the Devon Threshold Tool (Devon Safeguarding Children Board, 2016) and the auditing tools from Maximizing the Impact of Teaching Assistants project (Webster et al., 2015).

Secondly, a wide range of data collection methods were used to create a meaningful picture of pupil and staff knowledge and skills that was then analyzed to inform the changes required to improve pupil and school outcomes and practices. It was common for SENCOs to utilize a number of different methods. The methods used most frequently with teaching staff, support staff, and pupils were observations, questionnaires and interviews with findings supplemented with an analysis of school data. Observations of pupils and staff were undertaken in the classroom and in the playground, assessing the academic, social and emotional skills of pupils and knowledge, skills and expertise of staff. A number of the staff questionnaires focused on the deployment, preparedness and practice of the teaching assistant. Staff knowledge and skills and understanding of pupils' needs and performance were also assessed by means of interviews and questionnaires. Staff were interviewed to gain an insight into levels of confidence in identifying pupils' needs and tailoring provision for pupils. A range of data collection methods were used when focusing on the preparedness and practice of support staff. Interviews and questionnaires were undertaken with parents and included a focus on attitudes to reading and on use of spelling strategies. Pupils' views on their social and academic skills, including language, reading, spelling, and maths were determined through interviews and questionnaires.

Thirdly, formative assessment in the shape of the Code of Practice 2015 graduated response or “assess, plan, do, review cycle” was evident in the majority of the SENCO abstracts as a means of ensuring that the assessment process was dynamic and meaningful. Assessments such as those outlined earlier were undertaken as a baseline, and from this an intervention or plan to improve pupil and school performance and practice was planned, implemented and monitored by SENCOs during implementation. SENCOs reviewed the impact of the interventions and plans for strategic change by repeating baseline assessments post-intervention, before using the outcomes to plan the next steps in pupil provision and whole school development. This was evident in an abstract detailing the implementation of a 10-week reading intervention, in which interim monitoring was undertaken after five weeks, when a midway assessment was completed. Teaching Assistants' planning was monitored on a two-weekly cycle as well as a round of observations in the third week. Any weaknesses were addressed individually or during the weekly workshop meetings. A range of assessment and data collection methods were frequently employed to ensure that assessment processes were dynamic and responsive to the needs identified in relation to pupil need and staff development. Table 2 presents the range of assessment methods (published and school based) employed by SENCOs.

Theme 3: Evidence Informed Practice

The importance of adopting evidence informed practice was a third principle underpinning the practice of SENCOs in the study. Many of the assessment measures described in Theme 2 were examples of evidence informed approaches such as the Children's Autism Rating Scale, the Action Picture Test and the Digit Memory Test, all of which are used extensively clinically and in research. Another example of evidence informed practice were those abstracts where the origin or prompt for an assignment had been the publication of specific research studies that had resonance for a SENCO in terms of priorities in their settings. The most common subject was the deployment, preparedness and practice of TAs (N = 12):

“I used the Red Amber Green (RAG) self-assessment audit from the endowment foundation report (The Education Endowment Fund Foundation Guidance Report, 2013). Various forms of evidence fed into the RAG self-assessment; the recommendations checklist (quantitative), questionnaires regarding TA preparedness (qualitative), survey on preparedness to work with and mange TAs (quantitative) and observations (qualitative) from phase leaders focusing on effectiveness of TAs in lessons. The recommendations checklist enabled me to analyse the four key areas and gave observations and very clear focus.”

Primary SENCO

Another example was the use of research evidence on supporting the development of language in Key Stage 1:

“Using the Communication Supporting Observation Tool, an initial classroom audit was completed to ascertain opportunities provided for oral language development.”

Primary SENCO

Finally, SENCO practice was also influenced by a body of research findings that had developed over time. A common example was the research concerned with the principles associated with the provision of more effective professional development and learning opportunities in schools: little and often, based on practitioner need and pupil focused. This was evident from one Secondary SENCO undertaking Continuous Professional Development (CPD):

“to build partnerships between teachers, Learning Support Assistants (LSAs) and external agencies to create professional learning communities (PLC) as a learning version of a Team Around a Child where professionals from different organizations collaborate to produce child centred solutions in response to need or vulnerability.”

Secondary SENCO

Theme 4: Evaluating Impact

The final theme that emerged from the abstract analysis was the importance placed on evaluating impact with an emphasis on SENCOs making the best use of school resources (people and financial) to ensure better outcomes for pupils with SEN and/or disability. Most noticeably, this was evident in the focus on provision mapping1 and the monitoring and analysis of the impact of interventions for pupils (N = 13/50). Provision mapping was used to gain a broad overview of the efficacy of the interventions in place alongside auditing the effectiveness of specific interventions related to pupils in each of the four broad categories of need. One SENCO abstract highlighted the need to utilize time and resources effectively using provision mapping as a tool, explaining that the:

“assignment will audit the provision mapping in the school, assessing whether the programmes and interventions being used are evidence-based (and therefore an effective use of time/money) reviewing how provision mapping can be used as a more efficient and effective way to monitor progress and to identify patterns of need and areas for development of staff.”

Primary SENCO

This auditing process that was used to assess the effective use of school resources included audit measures devised by individual SENCOs alongside published audit tools, such as the nasen Provision Mapping Audit Tool, which was used to ensure that robust tracking systems for interventions were in place. Provision mapping was frequently used by SENCOs as, in their words, a vehicle to drive forward whole school changes.

Some examples of interventions for literacy that were monitored and evaluated included Colorful Semantics and evidence informed spelling interventions created by SENCOs for identified pupils. Maths interventions evaluated included Numbers Count and support for working memory. Social skills interventions were monitored for effectiveness in the classroom and the playground and the impact used to inform CPD needs and decisions regarding the ongoing use of particular interventions. The impact of Nurture Groups for pupils with SEMH needs was monitored and evaluated to assess staff skills and confidence as a means of identifying ongoing training needs.

Discussion

This study set out to investigate the practice of newly appointed SENCOs 40 years after the findings of the Warnock Report changed the landscape of SEND and inclusion in schools. The findings of this study revealed four key principles which underpinned SENCO practice and together demonstrated the breadth and complexity of the SENCO role. Firstly, as well as strategically supporting the education of pupils with diverse learning profiles and SEN and/or disabilities, SENCOs were collaborating with a range of staff at an individual, group and across a school to support the education of pupils with SEN and/or disabilities. Secondly, SENCOs employed a range of formative and summative assessment practices to support pupil learning but also to assess the professional learning and development needs of their colleagues to support pupil learning. Thirdly, SENCO practice was grounded in the use of evidence informed approaches. Finally, SENCOs were active in evaluating the impact of SEND, in particular, the deployment of school resources such as people, interventions and materials to meet the needs of pupils.

SENCO Practice: Warnock and Beyond

Despite the many criticisms of the Warnock Report, it is still possible to identify fundamental principles of the report that have influenced, nationally and internationally, the development of inclusive education and which were evident in the SENCO abstracts. Three specific principles from the report reflected in the abstracts were: support to be provided to more pupils with a range of SEN and/or disabilities; the effective assessment of SEND and the importance of multiple opportunities for practitioner learning and development, including that of senior leaders.

Firstly, recommended by Warnock, was a focus not only on the 2% of pupils educated in special schools at that time, but also on the 20% of pupils with a range of ongoing and potentially transitory difficulties in accessing the curriculum. The analysis of abstracts indicated that SENCOs were focusing on the needs of pupils across all categories of need at both SEND support level and those pupils with Education, Health and Care Plans. The greatest focus was on pupils with SLCN, literacy, SEMH and autism.

Secondly, the report identified four main requirements for effective assessment: the close involvement of parents; assessment should aim to uncover how a child learns to respond over a period of time and not just at one time point; the investigation of any aspect of performance that is of concern; family circumstances should be taken into account. All of these principles remain core to the current Code of Practice (2015) almost 40 years later and to a lesser or greater extent were evident in the abstracts. Developing strategies to assess a child's specific profile is a complex process but throughout the 50 abstracts that had a pupil focus, it was clear that SENCOs were working with an awareness of this complexity as shown by the nature and range of assessment data collected and analyzed. There was evidence of needing to go beyond a label and look at the barriers to learning in different contexts as well as the classroom, such as functioning during break times. What was less evident from the abstracts was the contribution of parent voice and taking the wider family circumstances into account, although one abstract did explore the use of the Devon Threshold Tool (Devon Safeguarding Children Board, 2016).

Finally, the Warnock Report recommended that parents should have a point of contact through a designated Named Person. The emphasis in policy of the importance of parents in the education of children with SEN and/or disabilities was strengthened by the Lamb Enquiry which set out to investigate more effective ways of including parents in supporting the education of pupils with SEN and/or disabilities and improving collaboration between school and home (Lamb, 2009). The recommendations of the Lamb Enquiry were embedded within the Code of Practice (2015) which placed parents at the heart of the decision-making process for children with SEN and/or disabilities. Overall, collaborating with parents as a focus for the work of SENCOs was little documented in the abstracts, apart from an abstract on the use of structured conversations with parents (Lendrum et al., 2015). The absence of parents in the abstracts does not mean that communication and collaboration were not a feature of the settings involved, but considering the policy focus, a greater emphasis in the abstracts might have been anticipated (Beveridge, 2004; Staples and Diliberto, 2010).

Limitations

There were three main limitations to the study. Firstly, this study is restricted to 50 students on a programme in one institution in England which limits the generalizability of the findings. Secondly, whilst the abstract analysis revealed that the practitioner enquiry undertaken by SENCOs was strongly informed by research evidence, it should be noted that the academic requirements of a Masters-level assignment will to some extent have influenced the role played by research evidence in SENCO enquiry projects. Finally, the focus is on the SENCOs perspectives which are not triangulated with other evidence such as the perspectives of other stakeholders (professionals, parents, children and young people); observation of practice or inspection reports.

The Way Forward

As a result of the findings of this study, the authors would make three recommendations for practice and research. Firstly, in order to effectively support the education of pupils with SEN and/or disabilities, school leaders need to allocate sufficient time not just for the SENCO role but for all practitioners in a setting. SENCOs require time, for example, to support the assessment of pupils, provide professional learning and development for colleagues, keep up to date with developments in SEND and lead and manage change in their settings. Class teachers and support practitioners need sufficient time to, for example, support formative and summative assessment, provide additional support as required and stay informed with evidence based practice. Secondly, SENCOs and school leadership teams should audit their practices in relation to parental support and engagement to ensure that parents of children with SEN and/or disability contribute fully to the education of their child. Finally, the breadth and complexity of SENCO responsibilities raises concerns not only about the retention of experienced, qualified SENCOs but also for their well-being. It is recommended therefore that SENCO well-being is protected through the introduction of professional supervision for all SENCOs.

Conclusion

The introductory chapter of the Warnock report concludes by stating that “Special education is a challenging and intellectually demanding field for those engaged in it” (Warnock, 1978, p 7). The findings from this study and the analysis of SENCO abstracts, 40 years on from the report, highlight some of the challenges faced daily by SENCOs in schools today and how additional study at postgraduate level can support SENCOs in engaging with an increasingly intellectually demanding field.

Data Availability

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript and/or the supplementary files.

Ethics Statement

The project followed the British Educational Research Association's (BERA) guidelines and received institutional ethics approval from the UCL Institute of Education Ethics Committee. SENCOs completed a written consent form to have their assignment abstracts included in the study.

Author Contributions

RE and CC have reviewed and approved the complete manuscript, contributed to all elements of the study, and in drafting the paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the SENCOs for participating in the study and Dr. Amelia Roberts, UCL Institute of Education, for her contributions to the study design and data collection.

Footnotes

1. ^Provision mapping is a way of evaluating the impact on pupils' progress of provision that is additional to and different from a school's curriculum offer to all pupils.

References

Alloway, T. P., Gathercole, S. E., and Kirkwood, H. (2008). Working Memory Rating Scale. London: Pearson Assessment.

Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). An analytical tool for qualitative research. Q. Res. 1, 385–405. doi: 10.1177/146879410100100307

Barton, L., and Oliver, M. (1992). “Special needs: personal trouble or public issue,” in Voicing Concerns: Sociological Perspectives on Contemporary Education Reforms, eds M. Arnott and L. Barton (Oxford: Symposium Books, 66–87.

Bennathan, M., and Boxall, M. (1998). The Boxall Profile: A Guide to Effective Intervention of Pupils with Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties. East Sutton: Association of Workers for Children Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties.

Beveridge, S. (2004). Pupil participation and the home–school relationship. Eur. J. Special Needs Educ. 19, 3–16 doi: 10.1080/0885625032000167115

Bondy, A., and Frost, L. (1994). The picture exchange communication system. Focus Autism Dev. Disabil. 9, 1–19. doi: 10.1177/108835769400900301

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Q. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101 doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

British Educational Research Association (BERA) (2011). Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. Available online at: https://www.bera.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/BERA-Ethical-Guidelines-2011.pdf?noredirect=

Bryan A. (1997). “Colourful semantics,” in Language Disorders in Children and Adults: Psycholinguistic Approaches to Therapy, eds S. Chiat, J. Law, and J. Marshall (London: Whurr, 143–161.

Caplan, M., Bark, C., and McLean, B. (2012). HAST-2: The Helen Arkell Spelling Test, Version 2. Surrey: Helen Arkell Dyslexia Centre.

Cumine, V., Dunlop, J., and Stevenson, G. (2009). Autism in the Early Years: A Practical Guide 2nd Edn. London: Routledge.

Curran, H., Mortimore, T., and Riddell, R. (2017). Special Educational Needs and Disabilities reforms 2014: SENCOs' perspectives of the first six months. Br. J. Special Educ. 44, 46–64. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12159

Department for Children Schools and Families (2007). Letters and Sounds: Principles and Practice of High Quality Phonics. London: Department for Children Schools and Families.

Department for Education (1994). Code of Practice on the Identification and Assessment of Special Educational Needs. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED385033.pdf

Department for Education (2015). SEND Code of Practice 0–25 Years. Available online at: www.gov.uk/government/publications/send-code-of-practice-0-to-25

Department for Education (2018a). Revised GCSE and Equivalent Results in England, 2016–2017. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/676596/SFR01_2018.pdf

Department for Education (2018b). Special Educational Needs in England. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/729208/SEN_2018_Text.pdf.

Department for Education Employment (1997). Excellence for All Children: Meeting Special Educational Needs. Available online at: http://www.educationengland.org.uk/documents/pdfs/1997-green-paper.pdf

Department for Education Skills (2001). Special Educational Needs Code of Practice. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/273877/special_educational_needs_code_of_practice.pdf

Devon Safeguarding Children Board (2016). Threshold Tool. Available online at: www.devonsafeguardingchildren.org/documents/2016/02/dscb-handy-threshold-tool.pdf/

Dockrell, J. E., Bakopoulou, I., Law, J., Spencer, S., and Lindsay, G. (2012). Communication Supporting Classroom Observation Tool. Available online at: https://www.thecommunicationtrust.org.uk/media/93866/tct_bcrp_csc_final.pdf

Done, L., Murphy, M., and Watt, M. (2016). Change management and the SENCO role: Developing key performance indicators in the strategic development of inclusivity. Support Learn. 31, 281–295. doi: 10.1111/1467-9604.12138

European Agency for Special Needs Inclusive Education (2017). European Agency Statistics on Inclusive Education: 2014 Dataset Cross-Country Report. Available online at: https://www.european-agency.org/data/key-messages-findings (accessed November 28, 2018).

Eurostat Statistics Explained (2018). Disability Statistics. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Disability_statistics (accessed January 2, 2018).

Farrell, P. (2001). Current issues in special needs: special education in the last twenty years: have things really got better? Br. J. Special Educ. 28, 3–9. doi: 10.1111/1467-8527.t01-1-00197

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 38, 581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Griffiths, D., and Dubsky, R. (2012). Evaluating the impact of the new National Award for SENCOs: transforming landscapes or gardening in a gale? Br. J. Special Educ. 39, 164–172. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12000

Lamb, B. (2009). Lamb Inquiry: Special educational needs and parental confidence. Report to the Secretary of State on the Lamb Inquiry review of SEN and disability information. Available online at: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/9042/1/Lamb%20Inquiry%20Review%20of%20SEN%20and%20Disability%20Information.pdf (accessed December 5, 2018).

Lendrum, A., Barlow, A., and Humphrey, N. (2015). Developing positive school–home relationships through structured conversations with parents of learners with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND). J. Res. Special Educ. Needs 15, 87–96. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12023

Lewis, I., and Vulliamy, G. (1980). Warnock or warlock? The sorcery of definitions: the limitations of the report on special education. Educ. Rev. 32, 3–10. doi: 10.1080/0013191800320101

Maher, A. (2016). Consultation, negotiation and compromise: the relationship between SENCOs, parents and pupils with SEN. Support Learn. 31, 4–12. doi: 10.1111/1467-9604.12110

Norwich, B., and Eaton, A. (2015). The new special educational needs (SEN) legislation in England and implications for services for children and young people with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties. Emot. Behav. Difficult. 20, 117–132. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2014.989056

OECD (2018). OECD Employment Outlook 2018. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available online at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/employment/oecd-employment-outlook-2018_empl_outlook-2018-en (accessed January 3, 2019).

Parkin, E., Kennedy, S., Bate, A., Long, R., Hubble, S., and Powell, A. (2018). Learning Disability: Policy and Services. Available online at: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN07058/SN07058.pdf

Passy, R., Georgeson, N., Schaefer, N., and Kaini, I. (2017). Evaluation of the Impact and Effectiveness of the National Award for Special Educational Needs Coordination. Available online at: https://afaeducation.org/media/1301/evaluation-of-the-impact-and-effectiveness-of-the-national-award-for-special-educational-needs-coordination.pdf

Pearson, S., Mitchell, R., and Rapti, M. (2015). “I will be ‘fighting’ even more for pupils with SEN”: SENCOs' role predictions in the changing English policy context. J. Res. Special Educ. Needs 15, 48–56. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12062

Qureshi, S. (2014). Herding cats or getting heard: The SENCO–teacher dynamic and its impact on teachers' classroom practice. Support Learn. 29, 217–229. doi: 10.1111/1467-9604.12060

Sacre, L., and Masterson, J. (2007). Single Word Spelling Test. National Foundation for Educational Research.

Schoon, I., and Lyons-Amos, M. (2016). Diverse pathways in becoming an adult: the role of structure, agency and context. Res. Soc. Stratification Mobil. 46, 11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2016.02.008

Schopler, E., Reichler, R. J., and Rochen Renner, B. (2002). The Childhood Autism Rating Scale. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Staples, K. E., and Diliberto, J. A. (2010). Guidelines for successful parent involvement: working with parents of students with disabilities. Teach. Except. Children 42, 58–63. doi: 10.1177/004005991004200607

Tissot, C. (2013). The role of SENCOs as leaders. Br. J. Special Educ. 40, 33–40. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12014

Turner, M., and Ridsdale, J. (2004). The Digit Memory Test. Available online at: https://www.dyslexia-international.org/content/Informal%20tests/Digitspan.pdf (accessed June 25, 2016).

United Nations Educational Scientific Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (1994). The Salamanca Statement and framework for action on special needs education: Adopted by the World Conference on Special Needs Education; Access and Quality. Available online at: www.unesco.org/education/pdf/SALAMA_E.PDF

United Nations Educational Scientific Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2010). Education for All. Global Monitoring Report. Available online at: http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/ED/pdf/Facts-Figures-gmr.pdf

US Department of Education (2015). “Every student succeeds act. S. 1177,” in Presented to the 114th Congress. Available online at: www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/1177

Visser, J. (2018). “A broad, balanced, relevant and differentiated curriculum?,” in Special Education in Britain After Warnock, eds J. Visser and G. Upton (London: Routledge, 1–12.

Warnock, M. (1978). Special Educational Needs: Report of the Committee of Enquiry into the Education of Handicapped Children and Young People. Available online at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20101007182820/http:/sen.ttrb.ac.uk/attachments/21739b8e-5245-4709-b433-c14b08365634.pdf

Watson, J., Davies, G., and Winterton, A. (2017). An evaluation of the Attention Autism approach with young children with autism. Good Autism Pract. 18, 79–93.

Webster, R., Russell, A., and Blatchford, P. (2015). Maximising the Impact of Teaching Assistants. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315695167

World Health Organization World Bank (2011). World Report on Disability. Available online at: https://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/report.pdf

Keywords: special educational needs, school, disability, SENCO, inclusion, warnock, practitioner enquiry

Citation: Esposito R and Carroll C (2019) Special Educational Needs Coordinators' Practice in England 40 Years on From the Warnock Report. Front. Educ. 4:75. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00075

Received: 19 March 2019; Accepted: 08 July 2019;

Published: 25 July 2019.

Edited by:

Geoff Anthony Lindsay, University of Warwick, United KingdomReviewed by:

Madeleine Sjöman, Jönköping University, SwedenElizabeth Fraser Selkirk Hannah, University of Dundee, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2019 Esposito and Carroll. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rosanne Esposito, ci5lc3Bvc2l0b0B1Y2wuYWMudWs=

Rosanne Esposito

Rosanne Esposito Catherine Carroll

Catherine Carroll