- The Excluded Lives Research Group, Department of Education, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

The 1978 Warnock Report made the case in the United Kingdom for a number of actions that, it was argued, would make the integration and support of young people with Special Educational Needs more effective. These included: a cohesive multi-agency approach in assessment and determination of special educational need and subsequent provision; early intervention with no minimum age to start provision for children identified with special educational needs; better structural and organizational accountability; the appointment of a Special Educational Needs Coordinator in each school; parental input to be valued and considered alongside professional views in matters relating to the child; and a recommendation that special classes and units should be attached to and function within ordinary schools where possible. The 1981 Education Act introduced a number of regulations and rights which supported the development of these forms of practice. However, the introduction of competition between schools driven by measures of attainment by the 1988 Education Act introduced new incentives for schools. At the same time there was a discourse shift from integration, or fitting young people with special educational needs into a system, to inclusion or inclusive practice in which inclusive systems were to be designed and developed. In the aftermath of this wave of policy development, a nascent tension between policies designed to achieve excellence and those seeking to achieve inclusive practice emerged. Whilst the devolved parliaments in Scotland and Wales have continued to try to give priority to inclusion in education, in recent years these tensions in England have intensified and there is growing concern about the ways in which schools are managing the contradictions between these two policy streams. There is widespread public and political unrest about the variety of ways in which young people with special educational needs, who may be seen as a threat to school attainment profiles, are being excised from the system either through formal exclusion or other, more clandestine, means. This paper charts this move from attempts to meet need with provision as outlined by Warnock to the current situation where the motives which drive the formulation of provision are driven by what are ultimately economic objects. We argue that policy changes in England in particular have resulted in perverse incentives for schools to not meet the needs of special educational needs students and which can result in their exclusion from school. These acts of exclusion in England are then compared to educational policies of segregation in Northern Ireland and then exemplified with data. We illustrate the impact of perverse incentives on practices of inclusion and exclusion through an analysis of interview data of key stakeholders in England gathered in a recent comparative study of practices of school exclusion across the four United Kingdom jurisdictions.

Introduction

The development of policy and practice in the field of special educational needs (SEN) and subsequently, after 2014, Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND) education in the United Kingdom (UK) has a long and convoluted history. These developments have often been, and remain to be, highly contested (Kalambouka et al., 2007). The field has witnessed political struggles between single interest lobby groups, practitioners and their professional associations, economists and administrators, amongst others. The recent history of the legislation and official guidance bears testament to the continuing complexity of the field. Cole (1990) suggests that this history is littered with contradictions and tensions between incentives of social control and humanitarian progress.

The Warnock Report (Department of Education Science, 1978) was an important milestone in, rather than an initiator of, the transformation of practices of exclusion of particular subgroups of children and young people from what counts as the mainstream in education. The motives for these transformations are not always apparent. This paper will begin with a discussion of these transformations and then compare them with changes in another form of segregation—the religious divide in schooling in Northern Ireland (NI). The purpose of this comparison is to examine whether there are commonalities in the values which have underpinned different policy moves and practices. The general argument of the paper is that practices of bringing together and keeping apart are driven by the interplay of a complex set of incentives set up, often unintentionally, by policies emanating from different stakeholder groups and recontextualized in different local settings and institutions. For example, in recent years the devolved parliaments in Scotland and Wales have continued to attempt to give priority to inclusion in education whereas these tensions in England have intensified and there is growing concern about the ways in which schools are managing the contradictions between these two policy streams (Daniels et al., 2017). We will illustrate the impact on practitioner views through an analysis of data gathered in a recent study of practices of exclusion undertaken by the multi-disciplinary Excluded Lives Research Group (forthcoming) which was set up in the University of Oxford and has now expanded to include colleagues from the universities of Queen's Belfast, Cardiff, and Edinburgh.

A History of Special Educational Needs Policy in the UK

Norwich (2014) argues that the SEN system in the UK cannot be understood outside the wider context of school education and social policy. His use of the term “connective specialization” (Norwich, 1995) suggests that what is specialized about the field is interdependent on the general system (Norwich, 2014). Norwich identifies four key aspects of the general system of relevance to the ways in which SEN is constituted: the National Curriculum and assessment, school inspection, the governance of schools, and equality legislation (in particular, disability as a protected characteristic). We argue that this is an important contribution but the connections extend beyond the realms of the education system into wider social welfare and political systems. Of particular importance is the way in which notions of difference are recognized, valued and regulated.

Some time ago Oliver (1986) suggested that the industrial revolution in the UK was a key historical moment in the marking of difference in terms of disability. In little more than the last 100 years there have been significant changes in ways that minority groups have been identified and managed. In the early years of the twentieth century, the 1921 Education Act legislated that a minority group of children, then referred to as “handicapped,” had rights to be educated in segregated classes or schools. The 1929 Wood Report considered what were regarded as key barriers to the implementation of these rights and produced a set of recommendations for the overall structure and, to some extent, functioning of a segregated system of schooling. These recommendations included the development of a differentiated curriculum for children who were then described as “mentally defective.” Different forms of class and whole school segregation were introduced. Taken together, the 1921 Act and the Wood Report set up the arguments and regulations for a form of segregated education for those who were identified as being in need of provision which was different from that which was made available in the mainstream. Intelligence tests formed an important part of the technology of segregation although other factors were seen to be at play in the placement of particular children in special schools (Tomlinson, 1981a,b). However, this form of segregation into different types of school was not the only means of institutionalizing difference. It was not until the enactment of the Handicapped Children Education Act (HM Government, 1970) that all children were deemed educable and brought into the education system. In theory those with a measured IQ of <50 were classified as uneducable before this Act and provision was made within the health service.

In the same decade as the 1970 Act, the Warnock Report was commissioned and published in 1978. Mary Warnock's remit was to review educational provision in the UK for young people with SEN. This report was an important milestone in the transformation of the ways in which young people with SEN were identified and systems of provision were managed. Schools were urged to integrate children with SEN into existing classrooms with additional support. The recommended move was away from alternative provision to the allocation of additional support in mainstream settings albeit not always in mainstream classrooms. Special classes and units were to be attached to ordinary schools and if this was not possible then specialist and mainstream provision was to be more tightly linked than in the past. The Education Act (HM Government, 1981) announced the rights of children with SEN to access appropriate education provision.

The Warnock Report is often taken as the moment at which the question of the location of provision for children and young people with SEN in the UK was brought to the attention of a wide constituency of policy makers and practitioners. The international equivalent is the somewhat later Salamanca Statement (UNESCO., 1994). The general move has been from policies and practices of segregation in special provision, through a phase where debates were concerned with the integration of individual children into existing systems, and, subsequently, on to the consideration of ways in which systemic responsiveness to a broad diversity of needs could be built in the name of inclusion.

The meanings associated with the terms “segregation,” “integration,” and “inclusion” have witnessed considerable variation over time, culture and context. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (Organisation for Economic Co-operation Development (OECD)., 2000) provided startling empirical evidence of variation in interpretation in rates of incidence, even across normative categories of sensory impairment. Avramidis and Norwich (2002) identified different interpretations of the idea of inclusive education on the part of parents, children, practitioners, teachers and leaders. The field is marked by a profusion of documents that can easily confuse a lay reader or busy practitioner with regard to what is legally enforceable and what is either recommended or advisable. Parliamentary Acts introduce enforceable law. Sections of these are then articulated by enforceable regulations. In the 5 years following the publication of the Warnock Report another distinction emerged in practice, if not the policy world, as children with sensory and physical disabilities became more integrated into schools whilst segregation of children with learning difficulties and behavior problems increased (Swann, 1988).

One important move came with the Special Educational Needs and Disability Act in 2001 (Department for Education Skills, 2001a). This brought the full force of anti-discrimination legislation to bear on education, which had been specifically exempt from such scrutiny in the past. Statutory guidance was issued in Inclusive Schooling: Children with special educational needs (Department for Education Skills, 2001b) alongside the non-statutory guidance available in the SEN Toolkit (Department for Education Skills, 2001c). However, there was considerable skepticism from both official and academic perspectives about the effectiveness and efficiency of much of the guidance (Farrell, 2001). A considerable body of enforceable legislation and statutory and non-statutory guidance creates a complex set of requirements and suggestions, which allow for a very high degree of local, highly situated interpretation (Audit Commission, 2002; Office for Standards in Education, 2004; House of Commons Education Skills Committee, 2006). These interpretations often appear to arise as “trade offs” made between contesting policy agendas, as witnessed in attempts to improve standards as well as to advance the development of inclusive practice. As Ainscow et al. (2006) note “there has been a powerful tradition in the inclusion literature of skepticism about the capacity of policy to create inclusive systems, either because the policy itself is ambiguous and contradictory, or because it is ‘captured' by non-inclusive interests as it interacts with the system as a whole” (305).

This skepticism about the policy environment has been followed by concern about the practices that have arisen during this period. Warnock (2005) herself argued that the policy of inclusion and the associated practice of issuing statements needed to be reviewed. A House of Commons Select (House of Commons Education Skills Committee, 2006) noted significant concerns about the demands and tensions that had arisen in the field particularly in coping with rising numbers of children with autism and Social, Emotional, or Behavioral Difficulties (SEBD).

Research funded by the National Union of Teachers and conducted by MacBeath et al. (2006) interviewed teachers, children and parents at 20 schools in seven local authorities and concluded that current practice placed far too many demands on teachers and schools. They make particular reference to the need for schools and special schools to work together in order to meet the diversity of needs that may be present in any particular community. In many ways MacBeath et al. echo the earlier assertions made in the (Department for Education Skills, 2004) report Removing the Barriers to Achievement that integration with external children's services, earlier intervention, better teacher training and improved expectations would reduce educational difficulty. However, the House of Commons Education and Skills (House of Commons Education Skills Committee, 2006) suggested that the notion of “flexible continuum of provision” being available in all local authorities to meet the needs of all children was not embedded in much of the guidance (27). This suggestion is evidenced in the Croll and Moses (2000) study, which drew on interviews with special and mainstream head teachers and education officers to show that there was much support for inclusion as an ideal—but which was not evidenced in policy. They found evidence of significant concerns about feasibility, given the extent and severity of individual needs and structural constraints on the practices of mainstream schooling.

Almost 10 years later, the Lamb Inquiry (Lamb, 2009) noted a significant disparity between policy and practice and the consequences for young people and their families. The enquiry evidenced the effects of local or situated re-enactment of policy (Ball, 2003) which gave rise to significant variation between settings in the availability of special educational needs and disability (SEND) provision. The Lamb Inquiry (Lamb, 2009) paved the way for major changes in the system. Four broad categories of reform were suggested:

• Incorporating information about SEND in the broader education framework to reduce systemic segregation of SEND children and their typical peers;

• Communication and engagement with parents rather than standardized information;

• An increased focus on outcomes for disabled pupils and pupils with SEND;

• Tighter quality assurance and accountability for meeting streamlined requirements (8).

To a certain extent these recommendations influenced the revision of the Children and Families Act (HM Government, 2014) and subsequent amendments to the Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND) Code of Practice (Department for Education, 2015). These are the latest in a long line of modifications and adjustments to the vision for the education system set out in the Warnock Report of 1978. However, Norwich and Eaton (2015) noted the contradictions between aspiration and outcome following these changes. One of their specific concerns was with children who were thought to have Emotional and Behavioral Difficulties (EBD). They drew attention to the rhetoric of increased parental choice over school placement, and the absence of evaluation of inclusive admissions procedures in schools by the Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted), the school inspectorate body in England. The Conservative Party government in the 2000s believed there had been an over-identification of special educational needs at the expense of those with complex needs; however, Norwich (2014), argues that this change has also been partly driven by economic austerity policies and this has negatively affected young people with Moderate Learning Difficulty (MLD) and Behavioral, Emotional, and Social Difficulties (BESD).

Norwich and Eaton (2015) point to difficulties with interagency working that have been highlighted all too frequently since the publication of the Warnock Report. They point out that multi-agency groups are “unique structures, each with their own socio-political context, objectives, working processes, internal dynamics and external pressures” (124) and it “has often been assumed that these groups will ‘just work' once outcomes have been agreed” (124) despite little evidence that this is so. Norwich and Easton cite Townsley et al. (2004) who evidenced persistent barriers to inter-group friendships and communication as a result of these conflicting stakeholder agendas. They also observed the likelihood for the focus of inter-disciplinary meetings to be deflected away from improved outcomes for the young person and toward the multi-agency structure itself. Hodkinson and Burch (2017) went further in suggesting that the SEND Code of Practice (Department for Education, 2015) actually “contains, constrains and constructs privilege as well as dispossession through enforcing marginality and exclusion” (2).

In summary, the litany of guidance and legislation that has been enacted since the Warnock era has served to recognize needs associated with particular groups whilst also giving rise, through the messy processes of implementation, to the creation of different patterns of barriers and support. It may be that the move away from official recognition of some needs has led to unrecognized patterns of marginalization. For example, the reduction in the application of the descriptors MLD and BESD may well be associated with a reduction in the proportion of students with SEN included in the exclusion data from around 70% in 2012/13 (Department for Education, 2016) to 46.7% in 2016/17 (Department for Education, 2018). This may be amplified by a lack of capacity to match need, however it is conceptualized or described, with provision. The moves from the early twentieth century affirmation of segregation to the incorporation of all children in the education system in 1970 and the exhortation to integrate (individuals) and subsequently to create inclusive systems have been marked by difficulties in ensuring that underlying values were witnessed in practice and not nullified through contradictions with other aspects of the policy world. It is in this context that Slee (2018) has suggested that there has been a seismic shift in attitudes and values toward inclusive education including “a rejection of its principles and practices with a call for a return to separate schools for children with disabilities” (17).

Across the UK, policy reforms in education have been underpinned by dual-commitments to school accountability for the progress of their students, and the inclusion of students from disadvantaged backgrounds, with special educational needs and disabilities. However, these tensions in England in particular have intensified and there is growing concern about the ways in which schools are managing the contradictions between these two policy streams. Ball (2003) has drawn attention to the dilemma of promoting practices of inclusion, whilst also deciding between incentives of excellence through competition on the basis of maximizing mean examination performance. This may be all the more problematic when access to support for meeting additional needs is highly constrained (Marsh, 2015). School exclusion—both official and “hidden”—can be seen as part of a political economy of schooling through which institutions seek to manage students' disruptive behavior in the context of increasing levels of accountability, an emphasis on high stakes testing and the proliferation of “alternative” forms of provision to which “troublesome” students can be outsourced. Ball (2003) and Connell (2009) have shown how the performative professionalism that arises in the kind of competitive practices that are often found in systems with high levels of accountability, undermines the capacity of professionals to meet the needs of disadvantaged social groups. In such situations, students who do not submit to the rules (Lloyd, 2008) become “collateral casualties” (Bauman, 2004), who find themselves locked in a process in which they are evacuated to the social margins of schooling (Slee, 2012). However, a recent study by Machin and Sandi (2018) suggested that there is a need for a nuanced account of the relationship between competition and exclusion, as exclusion is not always a means of facilitating better performance for autonomous schools in published league tables. They suggested that increases in school exclusions may partly be a consequence of disciplinary behavior procedures that some schools elect to implement as well as increasing pressure by parents and other bodies to ensure the school environment is protected from potential disruption. Persistent causes of exclusion are socio-historical, diverse and complex and intersect with each other in various ways to produce disparities in the social contexts of different jurisdictions (Cole et al., 2003).

In contrast to the devolved education systems of Scotland, and to some degree NI and Wales, commitment to accountability appears to override practices of inclusion in England (Daniels et al., 2017). Moreover, policy discourse in England has tended to individualize reasons for exclusion rather than develop an understanding rooted in the wider context of education, social and health policy (Mills et al., 2015). The Children's Commissioner for(Children's Commissioner, 2013) has argued for a greater understanding of the ways that conflicting policy motives may in practice form “perverse incentives” for schools to exclude students. As Mills et al. (2015) argue this policy contradiction in practice has led to schools in England finding ways to “move on” young people who do not fit into the market image that they wish to project. There is therefore a contradiction in England between the implementation of policies designed for inclusion in the spirit of the Warnock Report, such as the Children and Families Act (2014) and the updated SEND Code of Practice (2015), and performativity and accountability measures that have resulted in perverse incentives for schools to not meet the needs of SEND students and which can result in their exclusion from school.

Segregated Systems of Schooling

With these thoughts in mind, we turn to an analysis by Gallagher and Duffy (2015) of the evolution of segregated systems of schooling in NI. Here the focus is on religious communities. We suggest that there are important parallels with some of the general trends in the post-Warnock SEN systems. We argue that there are interesting similarities in the social and political movements that have progressively transformed systems of schooling in NI and in provision for young people with recognized SEN and or SEND. These parallels are suggestive of broader movements in thinking about and responding to difference in education that can result in systemic intolerance for children with different or special needs.

Gallagher and Duffy (2015) identify four systems of provision in NI: Unitary; Segregated; Multicultural; Plural. In a unitary system of single schools which assumes common cultural identity they point to expectations of conformity to mainstream values. Here schooling is a means of assimilating minority differences into a common ground. Gallagher and Duffy suggest that this model is systemically intolerant as there is no provision or recognition of minority groups. A variety of school types exist in what they term segregated systems and particular groups are allocated to particular types of school. A situation not unlike that which obtained across the UK in the early part of the twentieth century for children considered to be handicapped. Gallagher and Duffy (2015) argue that this is a “different form of systemic intolerance in that minorities are recognized, but marginalized, and often receive significantly poorer access to resources or opportunities” (37). Their other two types of system show strong parallels with the different integration and inclusion movements in the post-Warnock era. For them multicultural systems involve the establishing of a single school system, “but within which there is some acknowledgment and recognition of the identities of communities other than the majority identity. Unlike unitary systems these models promote the principle of recognition and seek to protect the identity and rights of minority groups within the single school system” (Gallagher and Duffy, 2015, p. 37).

As in the multicultural system, plural systems “embody the principle of recognition, but realize it through institutional means, so that minorities are accorded the right to have their own schools and are normally accorded some degree of equal treatment” (Gallagher and Duffy, 2015, p. 37). Thus, unitary systems neither tolerate nor recognize difference whereas segregated systems recognize difference but do not tolerate it in mainstream settings. Multicultural systems champion tolerance and incorporate diversity in shared spaces whereas in plural systems recognition of difference almost overrides tolerance and returns to differences in the formulation of provision. Whilst the similarities are not precise the identification of the underlying principles of tolerance and recognition provides a helpful tool with which to unpick the entanglements of different policy initiatives.

If the balances between recognition of difference and consequently of need and tolerance of diversity is being undermined by austere economic conditions and practice driven motives of institutional competition based on narrowly defined criteria for resource in the form of student numbers and consequent income then what are the perceptions of key stakeholders in the system? In the terms outlined by Gallagher and Duffy, exclusion may be seen as an extreme form of intolerance which is arguably often associated with a lack of recognition of need. We now report some of the findings of a series of interviews conducted with key stakeholders concerning the growth of practices of school exclusion in England in order to illustrate the nascent tension between policies designed to achieve excellence and those seeking to achieve inclusive practice.

Methods

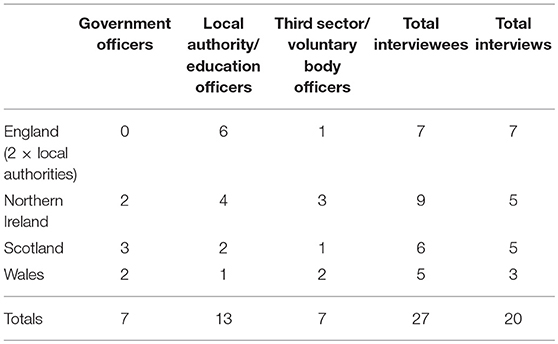

The data reported on here is a subset of data from the Excluded Lives project: Disparities in rates of permanent exclusion from school across the UK which sought to investigate the large increase in school exclusions in England over the past few years compared to the other three UK jurisdictions [Daniels et al., 2017; Excluded Lives Research Group (forthcoming)]. The project was funded by the John Fell Fund and received ethical clearance from the University of Oxford's Central University Research Ethics Committee. The study had three main aims, 1. To develop and trial a model of the practices and outcomes of exclusion in each of the four UK jurisdictions that can be used to elicit key stakeholder perspectives, 2. To elicit and analyse the perspectives of multiple stakeholders in each of the four jurisdictions on the practices of official and informal exclusion from school, and 3. To develop a theoretical account of the mutual shaping of policy and practice in the field of exclusion. The study design included an analysis of published national datasets on permanent and fixed period exclusions in the four UK jurisdictions, alongside documentary analysis of relevant legislation and national policy guidance, and semi-structured interviews with 27 key stakeholders from sites within the four UK jurisdictions between January and April 2018, see Table 1 below for further details.

Interviewees included senior policy makers and Government Officers, Local Authority (LA)/Education Officers concerned with education (overall), exclusion/inclusion, additional and/or alternative provision, child and adolescent mental health, special and/or additional needs and disability, and students Not in Education, Employment or Training (NEET); as well as senior officers, including three lawyers and a senior social worker, working for Third Sector/Voluntary Body organizations concerned with marginalized and disadvantaged children and young people. The interviewees were identified by existing contacts known by members of the research team, who acted as gatekeepers, and purposively selected participants in the four jurisdictions. Aside from the interviews conducted in NI, all interviews were carried out by two members of the research team, with one team member leading on all of the interviews to ensure consistency across the data collection. The second interviewers were members of the Research Group based in the different jurisdictions who were knowledgeable about the local contexts. At the beginning of each interview, the interviewees were presented with comparisons of the rates of permanent and fixed period exclusions in each jurisdiction over the past 5 years and asked to reflect on the figures for their jurisdiction. The following topics were then covered:

▪ Recent developments in policy and practice relating to exclusions at national and local level

▪ Positive aspects of policy and practice in the respondents jurisdiction/LA helping to prevent/reduce exclusions

▪ Support and provision available for “at risk” and excluded students

▪ Threats to current levels of support

▪ Accuracy of data on permanent and temporary exclusions

▪ LAs' ability to track excluded students

▪ Scale, nature and effects of unofficial exclusions.

Although the research did not focus directly on SEN students, there is a correlation between the likelihood of exclusion and SEN status, therefore the data is relevant to the current paper. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed with the informed written consent of the participants and lasted between 40 and 90 min. The findings presented below are from the English data only. The English sub-sample consisted of six LA practitioners from two different LAs (one northern—LA1, one southern—LA2), and a Third Sector representative based in London. All interviews were conducted with the interviewees in their place of work. The interview data were coded by one of the present authors (Tawell) following Braun and Clarke's (2006) six step guide to thematic analysis. Five key drivers behind the increase in number of school exclusions in England were identified: (1) policy changes; (2) school governance; (3) school culture and ethos; (4) accountability, performativity, and marketization; and (5) increasing demands, reduced capacity and financial pressures. Each theme is discussed below and illustrated with verbatim quotes.

Findings and Discussion

Theme 1: Policy Changes

When asked about what they believed may have led to the increase in school exclusion figures in England over recent years, the practitioners mentioned three related policy changes. The first was a perceived change in political discourse, with practitioners believing that in the current education climate, compared to the New Labor government period of 1997–2010, there is less emphasis on inclusion:

“…in the early 2000s we saw permanent exclusions and fixed terms drop… Reasons for that? I think maybe the political party at the time was encouraging inclusive practices” (LA1—Respondent 2)

The second policy change spoken about was the replacement of Independent Appeal Panels (IARs) with Independent Review Panels (IRPs) as part of the Education Act 2011, and the subsequent revisions made to the school exclusion statutory guidance in 2012. Respondents believed that the move from having IARs to IRPs marked a reduction in schools' accountability around exclusions.

“Nick Gibb [Education Minister]…came in with a clear intention to I guess reduce the accountability around exclusions. So, there was the Education Act 2011… and they removed the act to automatic reinstatement as part of the review process. They got rid of independent appeal panels. They introduced independent review panels, who had less of a role, and they could recommend reinstatement, but they couldn't order it. So that was an obviously very clear message to schools that the accountability around it was going to be relaxed. At the same time, there was the issue of academization [where schools were either forced or opted not to be under the control of LAs]. And what was the role of Local Authorities, so who's responsible for kids who get excluded became you know, quite muddied” (Third Sector Representative)

“…So, the exclusion process is, this is my view personally, the exclusion process is easier for schools now than it used to be. It's more difficult for Local Authorities to challenge schools, and it's more difficult for parents to have their voice heard. So, in the past, in previous versions of the exclusion guidance… [t]he parents had a right of appeal against the governors' discipline committee, now they don't. They have a right to review” (LA1—Respondent 1)

Both of the above quotes also indicate the reduced powers held by LAs, not only due to the revisions in the school exclusion statutory guidance, but also due to the changes in governance brought about by the Academies Programme. This will be returned to below under Theme 2: School governance.

Lastly, some respondents spoke about the difference in language used in the updated statutory guidance, which they believed was helping to validate schools' decisions to exclude:

“Although the new [school exclusion statutory] guidance was clearer in terms of what was guidance and what was law, what the previous guidance had, it had a lot more meat and the language it used was, all of it, those strategies, last resort, exhaustion, all those things, that went. Schools, they decided to pick up on some of the language in it that then made it almost in favor or to support their decision” (LA1—Respondent 2)

This point arguably overlaps with the first sub-theme and the identified move from an emphasis on inclusion to exclusion within current policy rhetoric.

The third policy change mentioned was the new SEND Code of Practice (Department for Education, 2015). Following claims by the Conservative party's Special Educational Needs Commission that “there was over-identification of special educational needs in schools” (Norwich, 2014, p. 418), Ofsted recommended that students not on the SEN register but classified as “School Action” should no longer be classified as having SEN. This recommendation was somewhat realized in the 2015 Code with the School Action and School Action Plus categories (students with lower levels of need) being replaced by SEN Support, which involves a “graduated approach to identifying and supporting pupils and students with SEN” (Department for Education, 2015, p. 14). A second change saw the replacement of Statements of SEN with Education Health and Care Plans (EHCP) for students with the highest level of needs.

The Third Sector Representative in the current study questioned whether this change could be linked to the recent rise in school exclusion numbers:

“What's happened to those hundreds of thousands of children with SEN, who had SEN five years ago and now don't? Now is that why we're suddenly seeing a big increase, because all of those children at School Action with low level needs have simply had their support removed and are now struggling with their learning and therefore getting into trouble through the disciplinary side?”

While some of the LA practitioners indicated that the change to the Code of Practice had resulted in a reduction of services, others (even within the same LA) believed that though the process had changed the support available remained the same:

“When the SEN Code of practice changed we then reduced our specialist teachers to give advice on behavior.” (LA1—Respondent 2)

“The process is different, but the support that was available is still there.” (LA1—Respondent 1)

Related to resources, one practitioner when speaking about a rise in students with SEN being excluded or at risk of exclusion in their LA, discussed how this may be due to an understanding that schools must demonstrate that they have invested in interventions to meet a student's needs before an EHCP assessment can be requested (there is in fact no legal basis behind this understanding):

“…we have had more young people with Education Health and Care Plans recommended for permanent exclusion and we've had more kids with other SEND that are less, not actually with Education Health and Care Plans, who've been excluded, so I think our SEND exclusions have gone up a little. Whether there's a direct correlation between that and the new code, because I do think the new SEN code in terms of its, the way it's written, in terms of empowering parents, I think is the absolute right way… whether there's an issue around the way that now schools have to put in the first so many thousand pounds…” (LA1—Respondent 2)

Therefore, the extent to which the new SEND Code of Practice has influenced the rise in school exclusion figures is debatable and warrants further exploration.

Theme 2: School Governance

The second identified theme related to the changing education landscape and the relationship between LAs and Academies. In LA1, two of the respondents considered that the LA had maintained a good relationship with their local Academies. However, the change in governance had meant that there was sometimes a delay in Academies reporting the needs of students to the LA, and a reduction in advice and assistance sought from their LA practitioners:

“We don't get contacted as early in the process as we used to.” (LA1—Respondent 1)

However, a third respondent from the same LA, believed that:

“…the whole academization programme has seriously undermined the relationship between the local authorities and schools and I think it's really unclear” (LA1—Respondent 3).

Unlike the first two respondents, Respondent 3 considered the relationship between the LA and its local Academies to be varied and noted that the LA had “recently begun to meet resistance from academies about attending hearings to support parents.” From a different angle, Respondent 3 also indicated that some maintained schools in their LA had been using the threat of academization as a bargaining tool to achieve their aims from the LA.

In LA2 respondents were much more aligned and firmer in their beliefs that the changes to school governance had affected exclusion practices:

“I also think the academy thing is one of the reasons [for the increase in school exclusion rates]” (LA2—Respondent 1)

When asked about whether they believed the freedom that Academies have was linked to the use of exclusion, LA2 Respondent 2 commented:

“Oh, without a doubt, it absolutely does and because also, it gives that message: ‘You do what you want to and it's not for the Local Authority to tell you how you should run things'. So, yes, and also I think it probably comes down to the individual ethos and the structure within a school and that does start at the top, doesn't it?” (LA2—Respondent 2)

Linked to the changing role of LA practitioners, was the sub-theme of responsibility:

“What should the Local Authority role be in that [exclusion process] and what do schools want? Because there's an element of want and what our responsibilities in terms of Ofsted because we are inspected and challenged and we carry responsibility for those children, yet we don't—we don't have the same authority that we once had. So, this is the big bubble of challenge.” (LA2—Respondent 2)

This relates back to the Third Sector Representative's earlier comment about who is responsible for excluded students becoming “quite muddied.” LAs are having to juggle their responsibility as a maintaining authority, while also developing their role as “facilitator” in the increasingly devolved system (Parish and Bryant, 2015). This is particularly relevant to school exclusions, as the LA retains responsibility over students who are permanently excluded. The extent to which the LA role is determined by the LA or Academies is also an area that needs further exploration, as this will ultimately determine the relationship and extent of collaboration between the two organizations. It can be argued that LAs, as the middle tier, are being squeezed by both school and system level factors (Daniels et al., 2018).

Relatedly, with LAs having less power to direct Academies over particular issues there has been concern that schools are opting out of systems in place to ensure vulnerable students receive an appropriate education (House of Commons Education Committee, 2018), such as In Year Fair Access Panels (IYFAP), and under increasing accountability pressures “game the system” by controlling their intakes (e.g., accepting fewer students with EHCPs; ibid). IYFAPs are designed to ensure that unplaced children, especially the most vulnerable or hard to place, are offered a school place quickly in order to minimize time spent outside education. Indeed, LA2, Respondent 2 stated how their number of referrals to the Education and Skills Funding Agency to direct schools to take students who required a school place had increased.

However, it cannot be claimed that only Academies have the desire to reduce the number of disruptive students in their schools. Talking more broadly, LA1 Respondent 3, noted how “schools want old school EBD [Emotional and Behavioral Difficulties] schools,” “they want to remove the problem from their school.”

Theme 3: School Culture and Ethos

The third theme revolved around school culture and ethos. When asked by the interviewer: “…are you sensing a difference in culture and sort of ethos?” LA1 Respondent 2 answered:

“Yes, I am. I think some of the behavior policies, if I read them, they're less conducive to kids who've got additional needs. They're more rigid… there's less movement within them.”

There was suggestion that the change in language, had also led to a change in culture and practice in school, and that messages instilled by government officials had played a part in this change:

“We've become less inclusive in our mainstreams.” (LA2—Respondent 1)

“It feels like there's a culture of much less tolerance of behaviors in schools than there used to be. We have anecdotal evidence from schools of things Ofsted inspectors said about how you will never be good or outstanding whilst you have those youngsters in school… I don't think Ofsted inspectors would give that message now, but the damage has been done.” (LA1—Respondent 3)

Both of these points link back to the change in political discourse discussed in Theme 1, and the performativity pressures placed on schools which will be further explored in Theme 4. Related to the above, LA1 Respondent 3 believed that the change in political discourse around inclusivity was illustrative of a much broader societal change in attitude:

“I think their [school staff] attitudes reflect the attitudes of society at large, so I think society is giving permission to those professionals who already hold those views, but possibility also influencing people who wouldn't have been going down that route, but are finding it really hard going because there are some really difficult kids out there who, in the past would have thought, ‘I've got to try and do more', and now—they can, ‘Well it's ok, I can just say it's their fault, it's the child's fault, get them away because my job is to get everybody to A*'.”

Many authors have spoken about the increasing individualization of problem behavior as highlighted by the phrase “it's the child's fault” in the above quotation, and the pressure of perverse incentives on teachers to move away from social and emotional aspects of learning and focus wholly on academic achievement.

Theme 4: Accountability, Performativity, and Marketization

As has already been touched upon, the accountability and performativity pressures that schools and teachers find themselves under in the current educational climate were also mentioned as a key factor that may be driving the rise in school exclusion figures in England. One particular accountability measure that was mentioned by many of the respondents was the Progress 8 benchmark, which is based on students' performance in eight qualifications, with English and Mathematics receiving double weighting:

“Our feeling is that it is because of how schools are judged, that it's about if kids aren't going to succeed in terms of the data, and Progress 8 is not going to help.” (LA1—Respondent 3)

There was a feeling amongst many of the respondents that there was a lack of desire from schools to invest in students who were unlikely to meet the Progress 8 benchmark:

“There's a real reluctance now for schools to put in an alternative package in Key Stage 4 [students aged 14–16]. Now, whether that is to do with… Progress 8, it's because of the qualifications they will take, yeah. And also the cost implication, and a permanent exclusion, even the other week I asked a headteacher if he would consider an alternative package for this young man, and his answer was financially it wasn't an efficient use of the school resources, so the answer was no.” (LA1—Respondent 2)

“So, a headteacher said to me, you know ‘It'll cost me £12,000 to put a full-time alternative package in', and bear in mind what you get to do is the AWPU [Age Weighted Pupil Unit], you know, age weighted pupil, I think, which is about £4,000 as well, so if you do the sums, yeah, and then secondary to the money, when the young person is at the alternative provider it's going to significantly impact on my Progress 8, and that's what schools are telling us.” (LA1—Respondent 2)

“Everybody has to concentrate on the pure part of the curriculum and teaching which is why we get the exclusions we get… Actually, there are cases where school staff would say ‘We'll take the hit, we'll take the fine'.” (LA2—Respondent 2)

This last quote draws attention to a related issue raised by the respondents, namely the narrowing of the curriculum:

“The curriculum has been made much more prescriptive, to get to the expected level, it's far more difficult and teachers who want to teach inclusively are finding it very difficult… which has knock on effects on behavior and engagement.” (LA 1—Respondent 1)

Moreover, when making decisions about whether or not to exclude, many of the respondents noted that the decision was not only based on whether or not the student under question would meet the Progress 8 benchmark, but whether or not they would also prevent their classmates from achieving due to their disruptive behavior. In the operation of a marketized system, schools must also prove to consumer parents that their schools provide a safe environment for their child to learn. Consequently, some of the respondents believed that schools were refusing students who may negatively affect the school's image:

“Parents like good behavior in schools. That's a big selling point. And we don't care about our neighbors next door.” (LA2—Respondent 1)

Theme 5: Increasing Demands, Reduced Capacity, and Financial Pressures

The final theme related to the conflict between increasing demands on the one hand and reduced capacity and financial pressures in both schools and LAs on the other. Of course there will inevitably be some differences in views expressed across LAs and the Third Sector because different policy and funding decisions are made by different LAs and in particular decisions that have been made as a response to cuts in LA funding. Turning first to the increasing demands, one of the most prevalent problems spoken about was mental health:

“So, social, emotional and mental health and Autism Spectrum Disorder are our two biggest pressure points at the moment.” (LA1—Respondent 1)

Despite the recognition of the problem, the view put forward by many of the LA practitioners was that they did not have the capacity to address it:

“I think because the demand seems to have increased, and yet whilst we're realigning and restructuring services, we haven't managed to keep pace with the increase in demand yet.” (LA1—Respondent 1)

Yet LA1 Respondent 1 did not think that staff restructuring was necessarily negative. Although in the short term she acknowledged that they were falling behind in case management, she believed in the longer term the restructuring could have a positive effect on ensuring that students' needs are met. Reflecting on her own new role, she noted how the restructuring had resulting in her having a position where she had oversight of many areas, which meant that she had a better understanding of “who to contact and who links with who.” Related to this point, there was a general recognition by the respondents of the importance of multi-agency/professional working. However, many believed that this type of working continues to be constrained by the silos that exist between different LA departments.

Additionally, when comparing the two LAs, even though the official figures showed that LA1 boasted higher rates of permanent and fixed period exclusions in 2016/17 than LA2, in general they were more positive about their current situation (although they saw themselves as “just so managing”; LA1—Respondent 1). Despite a reduction in staff across many areas, it seemed that they had retained more services and still saw their primary function as providing early intervention (even though as we have seen they were not being contacted as early in the process as they had been in the past to discuss students' needs).

In contrast, LA2 believed they were working in reactive mode:

“Teams have been cut so heavily, people are so busy doing the business of fire-fighting.” (LA2—Respondent 1)

“I think we've just been in a reactive phase because of the figures and the staffing situation we've had.” (LA2—Respondent 2)

“To be frank, we're in a position at the moment where schools are feeling the pinch financially, they are struggling with the reduction in all services across the board and support systems and increasingly turning to exclusion because I don't think they feel genuinely they have another option.” (LA2—Respondent 2)

The Third Sector Representative's description of the high needs block funding provides another example of the dual pressures of increasing demands, and reduced capacity:

“So what I've been writing this morning is about the high needs block, and that's the block of funding that Local Authorities hold to fund SEN and Alternative Provision (AP), and like all these systems, they have certain statutory duties. So they've got a job with the high needs block to keep kids in mainstream… When the kids get excluded or need to go to special school, the money gets taken out of the high needs block to pay for it and reduces the amount that the Local Authority can support the schools. So every graph is going up. The number of kids [who] are excluded is going up. The number of kids with EHC plans is going up. The number of kids in special school is going up. So as all these go up, the high needs block gets smaller and smaller, so the support that they can give to schools gets smaller and smaller. The behavior support team gets smaller and smaller. So then mainstream is even less able to keep them in, so more kids fall out, so we end up in a cycle, and that's where we are now, and it's going to burst.”

A recent report commissioned by the Department of Education (Parish and Bryant, 2015) similarly found that changes to funding formulas (e.g., high needs) and funding inequities between schools, coupled with an increasingly autonomous education system, have resulted in a breakdown in some areas of joined up services for vulnerable children and their families.

In the respondent accounts in the current study, there was discussion over how the number of students being permanent excluded in some areas was outstripping the number of places available at the local AP Academy/Pupil Referral Unit (PRU). This was found to result in one of two things, either those who were permanently excluded were failing to receive a spot and spending long periods of time out of education, or the permanently excluded students were allocated all of the places within the AP/PRU, meaning that no early intervention alternative packages could be offered by the provider. In addition to this, in some cases the LA practitioners described the allocation of provision as “ad hoc,” determined by what was available, rather than being needs-led, and affected by the geographical location of the provision in relation to the students' home.

As well as a reduction in early intervention support, some of the LA practitioners discussed how in the past they had been able to work with excluded students and their families over extended periods, and support students during their transition back into mainstream school, however, they no longer have the resources to be able to do this.

Lastly linking back to Theme 4, some of the respondents believed that as school budgets decrease, and services increasingly become “traded” (LA2, Respondent 1), schools are making the financial decision to exclude:

“Our argument is that schools are meant to make Alternative Provision for those children who struggle in the mainstream curriculum and the schools don't want to fund any form of Alternative Provision, they just want to get rid.” (LA 1—Respondent 3)

“As schools' budgets reduce, schools are beginning to just look down at themselves, they have less capacity and they're certainly not up for buying in extra things.” (Third Sector Representative)

The final quote below provides a summary example of the multiple pressures faced by schools and the impact this may be having on school exclusion practices:

“We had a change of curriculum, change of assessment, we had the change of Code of Practice. 2014 for teachers was pretty flipping stressful, and I think if teachers are stressed, they find it harder to manage stressed children.” (LA2—Respondent 1)

Teacher burn out, and recruitment and retention issues were also briefly mentioned in relation to the above point, however, these issues require further exploration before any conclusions can be drawn.

Conclusion

The 1978 Warnock Report made the case in the UK for a number of actions that, it was argued, would make the integration and support of young people with SEN more effective. These included: a cohesive multi-agency approach in assessment and determination of SEN and subsequent provision; early intervention with no minimum age to start provision for children identified with SEN; better structural and organizational accountability; the appointment of a SENCO in each school; parental input to be valued and considered alongside professional views in matters relating to the child; and a recommendation that special classes and units should be attached to and function within ordinary schools where possible. The 1981 Education Act introduced a number of regulations and rights which supported the development of these forms of practice. However, the introduction of competition between schools driven by measures of attainment by the 1988 Education Act introduced new incentives for schools that disadvantaged students with SEN. At the same time there was a discourse shift from integration, or fitting young people with special educational needs into a system, to inclusion or inclusive practice in which inclusive systems were to be designed and developed.

In the aftermath of this wave of policy development, a nascent tension between policies designed to achieve excellence and those seeking to achieve inclusive practice emerged. Whilst the devolved parliaments in Scotland and Wales have continued to try to give priority to inclusion in education, in recent years these tensions in England have intensified and there is growing concern about the ways in which schools are managing the contradictions between these two policy streams. There is widespread public and political unrest about the variety of ways in which young people with SEN, who may be seen as a threat to a school attainment profiles, are being excised from the system either through formal exclusion or other, more clandestine, means.

This paper has charted the move from attempts to meet need with provision as outlined by Warnock to the current situation where the motives which drive the formulation of provision are determined by what are ultimately economic objects. We have argued that policy changes in England in particular have resulted in perverse incentives for schools to not meet the needs of SEN students and which can result in their exclusion from school in ways that are comparable to educational policies of segregation in NI.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was acquired from the University of Oxford's Central University Research Ethics Committee (CUREC). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Author Contributions

HD, IT, and AT contributed conception and design of this article. HD wrote the first draft of the manuscript. IT and AT wrote sections of the manuscript. AT analyzed the data. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The research was funded by the John Fell Fund, grant number 162/092.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the work of Ted Cole and the Excluded Lives Group in collecting the data.

References

Ainscow, M., Booth, T., and Dyson, A. (2006). Inclusion and the standards agenda: negotiating policy pressures in England. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 10, 295–308. doi: 10.1080/13603110500430633

Avramidis, E., and Norwich, B. (2002). Teachers' attitudes towards integration/inclusion: a review of the literature. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 17, 129–147. doi: 10.1080/08856250210129056

Ball, S. (2003). The teacher's soul and the terrors of performativity. J. Educ. Policy 18, 215–228. doi: 10.1080/0268093022000043065

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Children's Commissioner (2013). “Always Someone Else's Problem”: Office of the Children's Commissioner's Report on Illegal Exclusions. London: CCfE.

Cole, T. (1990). The history of special education: social control or humanitarian progress? Br. J. Spec. Educ. 17,101–107.

Cole, T., Daniels, H., and Visser, J. (2003). Patterns of provision for pupils with behavioural difficulties in England. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 29, 187–205. doi: 10.1080/0305498032000080675

Connell, R. (2009). Good teachers on dangerous ground: towards a new view of teacher quality and professionalism. Crit. Stud. Educ. 50, 213–229. doi: 10.1080/17508480902998421

Croll, P., and Moses, D. (2000). Ideologies and utopias: education professionals' views of inclusion. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 15, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/088562500361664

Daniels, H., Thompson, I., and Tawell, A. (2017). Patterns and processes of school exclusions in England. Paper Presented at SERA Conference (Ayr).

Daniels, H., Thompson, I., and Tawell, A. (2018). Disparities, patterns and processes of school exclusions in England. Paper Presented at ECER Conference (Bolzano).

Department for Education (2015). Special Educational Needs and Disability Code of Practice: 0–25 Years. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/398815/SEND_Code_of_Practice_January_2015.pdf (accessed December 3, 2018).

Department for Education (2016). Permanent and Fixed-Period Exclusions in England: 2014 to 2015. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/permanent-and-fixed-period-exclusions-in-england-2014-to-2015 (accessed April 16, 2018).

Department for Education (2018). Permanent and Fixed-Period Exclusions in England: 2014 to 2015. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/permanent-and-fixed-period-exclusions-in-england-2016-to-2017 (accessed April 16, 2018).

Department for Education Skills (2001a). Special Educational Needs Code of Practice. Available online at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130322035715/https://www.education.gov.uk/publications/eOrderingDownload/DfES%200581%20200MIG2228.pdf (accessed December 3, 2018).

Department for Education and Skills (2001b). Inclusive Schooling: Children With Special Educational Needs. London: DfES.

Department for Education Skills (2004). Removing Barriers to Achievement: The Government's Strategy for SEN. Available online at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130404091106tf_/https://www.education.gov.uk/publications/RSG/publicationDetail/Page1/DfES%200117%202004 (accessed April 8, 2019).

Department of Education and Science (1978). The Report of the Committee of Enquiry into the Education of Handicapped Children and Young People. London: DES.

Excluded Lives Research Group (forthcoming) (2020). Disparities in Rates of Permanent Exclusion across the United Kingdom. Oxford: University of Oxford.

Farrell, P. (2001). Special education in the last twenty years: have things really got better? Br. J. Spec. Educ. 28, 3–9. doi: 10.1111/1467-8527.t01-1-00197

Gallagher, A. M., and Duffy, G. (2015). “Recognising difference while promoting cohesion: the role of collaborative networks in education,” in Tolerance and Diversity in Ireland North and South, eds I. Honahan and N. Rougier (Manchester: Manchester University Press), 33–54.

HM Government (1970). Education (Handicapped Children) Act. Available online at: http://www.educationengland.org.uk/documents/acts/1970-education-(handicapped-children)-act.pdf (accessed December, 3, 2018).

HM Government (1981). Education Act. Available online at: http://www.educationengland.org.uk/documents/acts/1981-education-act.pdf (accessed December, 3, 2018).

HM Government (2014). Children and Families Act. Available online at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/6/contents/enacted (accessed December 3, 2018).

Hodkinson, A., and Burch, L. (2017). The 2014 special educational needs and disability code of practice: old ideology into new policy contexts? J. Educ. Policy. 34, 155–173. doi: 10.1080/02680939.2017.1412501

House of Commons Education Committee (2018). Forgotten Children: Alternative Provision and the Scandal of Ever Increasing Exclusions. 5th Report of Session 2017-19. HC 342.

House of Commons Education and Skills Committee (2006). Special Educational Needs: Third Report of Session 2005–06, Vol. I. London: The Stationery Office.

Kalambouka, A., Farrell, P., Dyson, A., and Kaplan, I. (2007). The impact of placing students with special educational needs in mainstream schools on the achievement of their peers. Educ. Res. 49, 365–382. doi: 10.1080/00131880701717222

Lamb, B. (2009). The Lamb Inquiry. Special Educational Needs and Parental Confidence. Nottingham: Department for Children, Schools and Families.

Lloyd, C. (2008). Removing barriers to achievement: a strategy for inclusion or exclusion? Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 12, 221–236. doi: 10.1080/13603110600871413

MacBeath, J., Galton, M., Steward, S., MacBeath, A., and Page, C. (2006). The Costs of Inclusion. London: National Union of Teachers.

Machin, S., and Sandi, M. (2018). Autonomous Schools and Strategic Pupil Exclusion. CEP Discussion Papers dp1527. London: Centre for Economic Performance, LSE.

Marsh, A. J. (2015). Funding variations for pupils with special educational needs and disability in England. 2014 Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadersh. 45, 356–376. doi: 10.1177/1741143215595417

Mills, M., Riddell, S., and Hjörne, E. (2015). After exclusion what? Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 19, 561–567. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2014.961674

Norwich, B. (1995). Special needs education or education for all: connective specialisation and ideological impurity. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 23, 100–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8578.1996.tb00957.x

Norwich, B. (2014). Changing policy and legislation and its radical effects on inclusive and special education in England. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 41, 404–425. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12079

Norwich, B., and Eaton, A. (2015). The new special educational needs (SEN) legislation in England and implications for services for children and young people with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties. Emotional Behav. Difficulties 20, 117–132. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2014.989056

Office for Standards in Education (2004). Special Educational Needs and Disability: Towards Inclusive Schools. Manchester: Ofsted.

Oliver, M. (1986). Social policy and disability: some theoretical issues. Disabil. Handicap Soc. 1, 5–17.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2000). Special Needs: Statistics and Indicators. Paris: OECD.

Parish, N., and Bryant, B. (2015). Research on Funding for Young People With Special Educational Needs. Research Report 470. London: Department for Education.

Slee, R. (2012). How do we make inclusive education happen when exclusion is a political predisposition? Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 17, 895–907. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2011.602534

Slee, R. (2018). Paper Commissioned for the 2020 Global Education Monitoring Report, Inclusion and Education. Paris: UNESCO.

Swann, W. (1988). Trends in special school placement to 1986: measuring, assessing and explaining segregation. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 14, 139–161.

Tomlinson, S. (1981a). “The social construction of the ESN[M] child,” in Special Education: Policy, Practices and Social Issues, eds L. Barton and S. Tomlinson (London: Harper and Row), 194–213.

Tomlinson, S. (1981b). Educational Sub-Normality–A Study in Decision Making. Henley: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Townsley, R., Abbott, D., and Watson, D. (2004). Making a Difference: Exploring the Impact of Multi-Agency Working on Disabled Children with Complex Health Care Needs, Their Families and the Professionals Who Support Them. Bristol: Policy Press.

UNESCO. (1994). Final Report: World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality. Paris: UNESCO.

Keywords: special educational needs, inclusion, exclusion, Warnock, perverse incentives

Citation: Daniels H, Thompson I and Tawell A (2019) After Warnock: The Effects of Perverse Incentives in Policies in England for Students With Special Educational Needs. Front. Educ. 4:36. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00036

Received: 31 January 2019; Accepted: 09 April 2019;

Published: 24 April 2019.

Edited by:

Geoff Anthony Lindsay, University of Warwick, United KingdomReviewed by:

Lorella Terzi, University of Roehampton, United KingdomPhilip Harold Stringer, University College London, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2019 Daniels, Thompson and Tawell. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Harry Daniels, aGFycnkuZGFuaWVsc0BlZHVjYXRpb24ub3guYWMudWs=

Harry Daniels

Harry Daniels Ian Thompson

Ian Thompson Alice Tawell

Alice Tawell