95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 07 March 2019

Sec. Assessment, Testing and Applied Measurement

Volume 4 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00016

This article is part of the Research Topic Cultural Contexts and Priorities in Assessment View all 6 articles

How teachers conceive of the nature and purpose of assessment matters to the implementation of classroom assessment and the preparation of students for high-stakes external examinations or qualifications. It is highly likely that teacher beliefs arise from the historical, cultural, social, and policy contexts within which teachers operate. Hence, it may be that there is not a globally homogeneous construct of teacher conceptions of assessment. Instead, it is possible that a statistical model of teacher conceptions of assessment will always be a local expression. Thus, the objective of this study was to determine whether any of the published models of teacher assessment conceptions could be generalized across data sets from multiple jurisdictions. Research originating in New Zealand with the Teacher Conceptions of Assessment self-report inventory has been replicated in multiple locations and languages (i.e., English in New Zealand, Queensland, Hong Kong, and India; Greek in Cyprus; Arabic in Egypt; Spanish in Spain, Ecuador) and at different levels of instructional contexts (Primary, Secondary, Senior Secondary, and Teacher Education). This study conducts secondary data analyses in which eight previously published models of teacher conceptions of assessment were systematically compared across 11 available data sets. Nested multi-group confirmatory factor analysis (using Amos v25) was carried out to establish sequentially configural, metric, and scalar equivalence between models. Results indicate that only one model (i.e., India) had configural invariance across all 11 data sets and this did not achieve metric equivalence. These results indicate that while the inventory can be used cross-culturally after localized adaptations, there is indeed no single global model. Context, culture, and local factors shape teacher conceptions of assessment.

How teachers understand the purpose and function of assessment is closely related to how they implement it in their classroom practice. While using assessment for improving teaching and learning may be a sine qua non of being a teacher, the enactment of that belief depends on the socio-cultural context and policy framework within which teachers operate. Variation in those contexts is likely to change teacher conceptions of assessment meaning that while purposes (e.g., accountability or improvement) may be universal, their manifestation is unlikely to be so. This discrepancy creates significant problems for cross-cultural research that seeks to compare teachers working in different contexts. The lack of invariance in a statistical model is often used to indicate that the inventory eliciting responses is problematic. However, it might be due to the many variations in instructional contexts which do not lead to a universal statistical model. Building on this idea, the purpose of this paper is to examine teacher responses from 11 different jurisdictions to a common self-report inventory on the purposes and nature of assessment (i.e., the Teacher Conceptions of Assessment version 3 abridged).

When educational policy needs to be implemented by teachers, how teachers conceive of that policy controls the focus of their attention and their understanding of the same material as well as influencing their behavioral responses to the policy (Fives and Buehl, 2012). Educational policy around assessment often seeks to use evaluative processes to improve educational outcomes. However, the same policies usually expect evaluation to indicate the quality of teaching and student learning. These two purposes strongly influence teacher conceptions of assessment.

The term conceptions is used in this study to refer to the cognitive beliefs about and affective attitudes toward assessment that teachers espouse, presumably in response to the policy and practice environments in which they work. This is consistent with the notion that teacher conceptions of educational processes and policies will shape decision making so that it makes sense and contributes to successful functioning within a specific environment (Rieskamp and Reimer, 2007).

A significant thread of research into the varying conceptions of assessment teacher might have can be seen in the work Brown and his colleagues have conducted. Brown's (2002) doctoral dissertation examined the conceptions of assessment New Zealand primary school teachers had. That work developed a self-administered, self-report survey form that examined four inter-correlated purposes of assessment (i.e., improvement, irrelevance, school accountability, and student accountability) (Brown, 2003). He reported (Brown, 2004b) that teachers conceived of assessment as primarily about supporting improvement in teaching and student learning and was clearly not irrelevant to their instructional activities. They accepted that it was somewhat about making students accountable, but rejected it as something that should make teachers and schools accountable.

Subsequently replication studies have been conducted in multiple jurisdictions. Other researchers have reported interview, focus group, and survey studies using different frameworks than that used by Brown. Consequently, major reviews of the research into teacher conceptions of assessment (Barnes et al., 2015; Fulmer et al., 2015; Bonner, 2016; Brown, 2016) have made it clear that teachers are aware of and react to the strong tension between using assessment for improved outcomes and processes in classrooms, and assessment being used to hold teachers and schools accountable for outcomes by employers or funders. The more pressure teachers are under to raise assessment scores, the less likely they are to see assessment as a formative process in which they might discover and experiment with different practices (Brown and Harris, 2009). Conversely, where educational policies keep consequences associated with assessment relatively low, such as in New Zealand (Crooks, 2010), the endorsement of assessment as a formative tool to support improvement is much greater.

Thus, because policy frameworks globally are seeking to increase the possibility of using assessment for improved outcomes (Berry, 2011a) and because researchers are willing to use previously reported inventories, there has been increasing research into teacher conceptions of assessment using the New Zealand Teacher Conceptions of Assessment inventory (Brown, 2003). Following the same line of research, this paper exploits a series of replication studies conducted by Brown and his colleagues in a wide variety of contexts internationally. Statistical models fitted to each data set were sometimes similar, but non-identical. The purpose of the current project was to conduct a systematic invariance study to determine if there are any generalizable models across the jurisdictions. This analysis could help us understand how teachers' beliefs about assessment are shaped across different jurisdictions and could also provide some guidelines for those working in international instructional contexts.

Before examining data, it is important to describe the policy contexts in which the data were collected. The descriptions are correct for the time period in which the data were collected, but may no longer accurately describe the current realities. The contexts are grouped as to whether each jurisdiction is defined as being relatively low-stakes assessment environments (i.e., New Zealand, Queensland, Cyprus, and Catalonia) or examination-dominated (i.e., Hong Kong, Egypt, India, and Ecuador).

The following section includes a description of the low-stakes instructional contexts from which data were collected, including New Zealand, Queensland, Cyprus, and Catalonia.

At the time of this study, the New Zealand Ministry of Education required schools to use assessment for improving the learning outcomes of students and provide guiding information to managers, parents, and governments about the status of student learning (Ministry of Education, 1994). Learning outcomes in all subject areas (e.g., language, mathematics, science, etc.) were defined by eight curriculum levels broken into multiple strands. The national policy required school assessments to indicate student performance relative to the expected curriculum level outcomes for each year of schooling (Ministry of Education, 1993, 2007). A range of nationally standardized but voluntary-use assessment tools were available for teachers to administer as appropriate (Crooks, 2010). Additionally, the Ministry of Education provided professional development programmes that focused on teachers' use of formative assessment for learning.

New Zealand primary school teachers made extensive use of informal and formal assessment methods primarily to change the way they taught their students and as a complement to evaluate their own teaching programmes. In contrast, the secondary school assessment environment, despite being governed by the same policy framework as the primary school system, was dominated by The National Qualifications Framework (NQF). Officially, school qualifications assessment (i.e., National Certificate of Educational Achievement [NCEA] Level 1) begins in the third year of secondary schooling (students nominally aged 15) (Crooks, 2010). However, the importance of the school qualifications has meant considerable washback effects, with much adoption of qualifications assessment systems in the first 2 years of secondary schooling. Furthermore, approximately half of the content in each subject was evaluated through school-based teacher assessments of student performances (i.e., internal assessments). This means that teachers act as assessors as well as instructors throughout the three levels of the NCEA administered in New Zealand secondary schools.

At the time of the study, Queensland, similar to New Zealand, had an outcomes-based curriculum framework, limited use of mandatory national testing, and a highly-skilled teaching force. Primary school assessment policies (years 1–7) differed to that of secondary schooling (years 8–12). In general, years 1–10 were an “assessment-free zone” in that there were no common achievement standards or compulsory common assessments. There were formal tests of literacy and numeracy at years 3, 5, and 7 used for system-wide monitoring and reporting to the Federal Government. Because the tests were administered late in the school year (to maximize results for the year) and reporting happened at the start of the following school year, the impact of the tests on schools or teachers was relatively minimal.

Only in the final 2 years of senior secondary school (i.e., 11 and 12) is there a rigorous system of externally moderated school-based assessments indexed to state-wide standards. These in-school assessments for end of schooling certification are largely designed and implemented by secondary school teachers themselves, who also act as moderators. Most senior secondary-school teachers also teach classes in lower secondary. Therefore, it is highly likely that the role of being a teacher-assessor for the qualifications systems will influence teachers' assessment practices and beliefs, even for junior secondary classes in years 8–10.

Greek-Cypriot's education system aims for a gradual introduction and development of children's cognitive, value, psychokinetic and socialization domains (Cyprus Ministry of Education and Culture, 2002). The major function of assessment is a formative process within the teaching–learning cycle with the goal of improving outcomes for students and teacher practices. Assessments, while aiming to provide valid and reliable measurements, avoid selection or rejection of students through norm-referencing (Papanastasiou and Michaelides, 2019). This is achieved through the qualitative notes and observations teachers make, the use of student self-assessments, and a combination of standardized and teacher-developed tests (Cyprus Ministry of Education and Culture, 2002).

Consequently, the assessment function within the Cypriot education system is relatively low stakes (Michaelides, 2014). In primary school, assessments are mainly classroom-based with grades recorded by the teachers for each student primarily for internal monitoring of student progress achievement rather than for formal reporting. The Ministry of Education provides tests for a number of subjects, which teachers use alongside their own assessments. However, in Grades 7–9 (i.e., gymnasium), formal testing increases through teacher-designed tests and school-wide end-of-year exams in core subjects (Solomonidou and Michaelides, 2017). This practice continues into senior secondary Grades 10–12 in both the lyceums and technical schools. While the government does not mandate compulsory, large-scale assessments, senior students voluntarily participate in international exams or national competitions.

Grade 12 culminates in high stakes national examinations that certify high school graduation and generate scores for access to public universities and tertiary institutions in both Cyprus and Greece. Unsurprisingly, these end-of-high-school national exams are favorably evaluated by students and the public in general (Michaelides, 2008, 2014).

Catalonia is an autonomous community within Spain and data for this study were collected there. The Catalonian school system has 6 years of Primary School and 4 years of Secondary School (Ley de Ordenación General del Sistema Educativo, 1990). At the end of 10 years of compulsory schooling, students enroll in either basic vocational education, technical vocational education, or 2 year high schooling in preparation for university or superior vocational education. Assessment policy prioritizes low-stakes, school-based, continuous, formative, and holistic practices. Promotion decisions after Grade 6 and 10 are based on teaching staff consensus concerning students' holistic learning progress, without recourse to external evaluation. Assessments in vocational and technical education emphasize authentic and practical skills. However, at the end of post-compulsory university preparation, a university entrance examination is administered.

The following part describes the high-stakes instructional contexts from which data were collected, including Hong Kong, Egypt, India, and Ecuador. Teachers in these contexts face substantial challenges if called upon to implement policies that seek to modify or change the role of summative examination.

Since the end of the British rule in Hong Kong in 1997, the education system has systematically worked toward ensuring access for all students to 12 years of schooling (achieved in 2012). Like other jurisdictions influenced by the UK Assessment Reform Group, Hong Kong has discussed extensively the use of assessment for learning (Berry, 2011b), while at the same time maintaining a strong examination system and culture (Choi, 1999). Dependence on the validity of formal examinations has arisen from multiple factors, including the British public examinations and a strong sense that without examinations a meritocratic society would not be possible (Cheung, 2008). Unsurprisingly, the “assessment for learning” agenda, despite formal support from government agencies [Curriculum Development Council (CDC), 2001] has struggled to gain foothold against the hegemony of examinations; a case of soft vs. hard policy (Kennedy et al., 2011). Carless (2011), a strong advocate of assessment for learning, has accepted that summative testing is inevitable but has called for the formative and diagnostic use of summative testing.

Egypt education is dominated by examinations used to select students for access to further opportunities (Hargreaves, 2001; Gebril and Eid, 2017). At the time of this study, end-of-year exams were the only mechanism in public schools to move students from one educational stage to the next. Higher exam scores result in placement in better schools at the end of primary education (Grade 6), while higher scores in the Grade 9 final exam place students in higher-esteemed general secondary schools or technical/vocational schools. Finally, the end of secondary school exam determines the university and academic programme into which students can join. In addition to the benefits individual students experience through high exam scores, schools themselves gain rewards when their students appear in the lists of high-performing students. Thus, high achievement in general gains respect in, for, and from families and schools.

Comprehensive Assessment (CA) was introduced by the Ministry of Education to balance the overwhelming effect of summative examinations. The CA initiative expected teachers to embed assessment activities within instruction and make it an ongoing learning-oriented process making use of alternative assessment tools. Despite the potential of this approach, the CA policy was stopped because of many challenges including teachers' lack of assessment literacy and difficult work conditions in schools. Nonetheless, the Egyptian government is still seeking to modify instructional and assessment practices by removing all formal exams in primary schools before Grade 4 (Gebril, 2019).

Consistent with other federal systems, education in India is a state-level responsibility. The post-primary school system (NUEPA, 2014) consists of secondary (Class 9–10) and upper secondary (Class 11–12) schools. Teachers are largely highly qualified with many holding postgraduate or higher qualifications. However, classes are large with an average of 50 pupils per room. Unfortunately, enrolment beyond elementary schooling is not universal, with drop-out more pronounced among girls. Secondary school qualifications are generally administered by various central boards (e.g., Central Board of Secondary Examination, CBSE; Indian Secondary Certificate of Education, ISCE; Senior Secondary Certificate, SSC). Despite their unique flavors, central boards generally have similar evaluative processes making use of high-stakes summative examinations at the end of Classes 10 (end of secondary) and 12 (end of upper secondary).

Efforts to diversify student evaluation beyond examination performance have resulted in Central Boards developing assessment schemes for determining children's all-round development. For example, Continuous and Comprehensive Evaluation (CCE) developed by the CBSE is a school-based assessment scheme that exercises frequent and periodic assessments to supplement end-of-year final examinations (Ashita, 2013). Thus, although there is school-based assessment in Indian schools it is a form of summative assessment that combines coursework, mid-course tests, and final examinations to create an overall grade.

Ecuador is a multilingual and multicultural South American country with more than 16,000,000 inhabitants. Most people (>60%) live in urban areas. Recent Ecuadorian legislation (2011) provides schooling up to age 15; this is made up of 6 years primary and 4 years secondary schooling. The final 2 years are either in a general or vocational senior high school (OECD, 2016). In 2006, an immense renewal project was launched by the government that created many new schools and provided a high level of technological resources.

Schooling is generally characterized by strong traditional conventions examination and pedagogical practices. Teachers are regarded as having strong authority over the classroom. Promotion at the end of the year depends on gaining at least 70% on the end-of-year examination.

Practicing teachers were surveyed in all jurisdictions except the Catalonia study. Table 1 provides descriptive information concerning when data were collected, sample size, scales collected simultaneously with the TCoA, the sampling mechanism, the subjects taught, and the representativeness of the sample to the population of the jurisdiction. Data were collected between 2002 and 2017 and in most studies teachers responded to additional scales. The New Zealand and Queensland sampling was representative via the school, not the teacher. Sampling otherwise was convenience but was national in Cyprus, India, and Ecuador.

Testing of sample equivalence to the population was rare (New Zealand, Cyprus, and India) and was generally limited to teacher sex. Only five studies identified the subject taught by the teacher. Unsurprisingly, languages (English, Chinese, and Arabic), mathematics, and science accounted for the largest proportions of subjects taught.

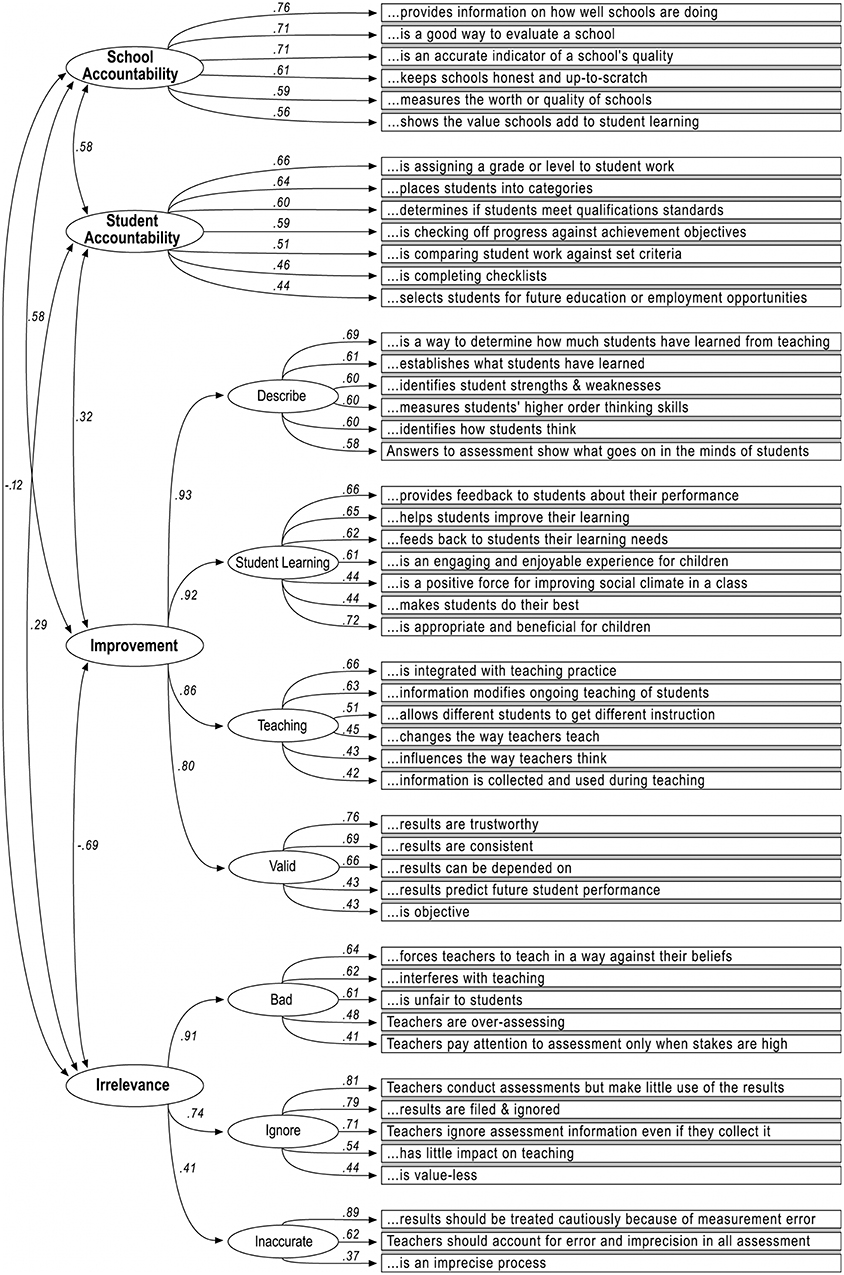

The Teacher Conceptions of Assessment inventory (TCoA-III) was developed iteratively in New Zealand with primary school teachers to investigate how they understand and use assessments (Brown, 2003). The TCoA inventory is a self-reported survey that allows teachers to indicate their level of agreement with statements related to the four main purposes of assessment. The inventory allows teachers to indicate whether and how much they agree that assessment is used for improved teaching and learning, assessment evaluates students, assessment evaluates schools and teachers, or assessment is irrelevant. The 50-item New Zealand model consisted of nine factors, seven of which were subordinate to improvement and irrelevance (Figure 1). The superordinate improvement and irrelevance factors were correlated with the two accountability factors (i.e., school and student). The structure and items of the full TCoA-III are available in a data codebook and dictionary (Brown, 2017). An abridged version of 27 items (TCoA-IIIA), which has the same structure as the full version, consists of three items per factor and was validated with a large sample of Queensland primary teachers (Brown, 2006). The items for the TCoA-IIIA are listed in Table 2.

Figure 1. TCoA-III Model with New Zealand Primary School Results. (Figure 1 from Brown (2004b) reprinted by permission of Taylor and Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com).

In all studies using the TCoA reported in this paper, participants indicated their level of agreement or disagreement on a bipolar ordinal rating scale. The Hong Kong study used a four-point balanced rating scale in which 1 = strongly agree, 2 = agree, 3 = disagree, and 4 = strongly disagree. In Cyprus, a balanced six-point agreement scale was used, coded: 1 = completely disagree, 2 = disagree to a large degree, 3 = disagree somewhat, 4 = agree somewhat, 5 = agree to a large degree, and 6 = completely agree. In all other jurisdictions (i.e., New Zealand, Queensland, Catalonia, Egypt, India, and Ecuador) a six-point, positively packed, agreement rating scale was used. This scale has two negative options (i.e., strongly disagree, mostly disagree) and four positive options (slightly agree, moderately agree, mostly agree, and strongly agree). Positive packing has been shown to increase variance when it is likely that participants are positively biased toward a phenomenon (Lam and Klockars, 1982; Brown, 2004a). Such a bias is likely when teachers are asked to evaluate the assessment policies and practices for the jurisdiction in which they work. Successful publication of the inventory (Brown, 2004b) led to a number of replication studies including New Zealand secondary teachers (Brown, 2011), Queensland primary and secondary teachers (Brown et al., 2011b), Hong Kong (Brown et al., 2009), Cyprus (Brown and Michaelides, 2011), Egypt (Gebril and Brown, 2014), Catalonia (Brown and Remesal, 2012), India secondary and senior secondary teachers (Brown et al., 2015), Ecuador (Brown and Remesal, 2017). Hence, data from 11 different sets of teachers from eight different jurisdictions are available for this study.

When the TCoA-III was administered in new jurisdictions, different configural models arose out of the data. In some cases the differences were small involving the addition of a few paths or trimming of items. For other jurisdictions, substantial changes were required to generate a valid model. These best-fit models for each jurisdiction are briefly described here. Note that all studies were conducted and published individually with ethical clearances obtained by each study's author team, usually by the author resident in the jurisdiction. The analyses reported in this paper are all based on secondary analysis of anonymized data; hence, no further ethical clearance was required.

The Queensland primary teacher model was identical to the New Zealand TCoA-IIIA model (Brown, 2006). However, in an effort to include the secondary teachers, two additional paths were required to obtain satisfactory fit (Brown et al., 2011b). Two paths were added; one from Student Accountability to Describe and a second from Student Learning to Inaccurate. Otherwise the hierarchical structure and the item to factor paths were all identical to the New Zealand model.

The New Zealand model did not fit, but by deleting two of the first-order factors and having the items load directly onto the second-order factor an acceptable model was recovered (Brown et al., 2009). Under Improvement the Describe factor and under Irrelevance the Inaccurate factor were eliminated. Nonetheless, the model was otherwise equivalent with the same items, same first-order factors, and the same hierarchical structure.

The New Zealand model was not admissible due to large negative error variances, suggesting that too many factors had been proposed (Brown and Michaelides, 2011). Instead by deleting three items, a hierarchical inter-correlated two-factor model was constructed. The two factors, labeled Positive and Negative, had three and two first-order factors. Overall, 20 of the 24 items aggregated into the same logically consistent factors as proposed in the New Zealand model. The Cyprus model was shown to be strongly equivalent with both groups of New Zealand teachers.

This study compared undergraduate students learning about educational assessment in Catalonia and New Zealand (Brown and Remesal, 2012). The New Zealand model was inadmissible due to large negative error variances. A model, based on an exploratory factor analysis of the New Zealand data, had all 27 items in five inter-correlated factors, of which three had hierarchical structure. One of the four factors of improvement (Valid) moved to School Accountability, while the Bad factor of Irrelevance moved out from under it to become one of the five main inter-correlated factors. This model had only configural invariance between Catalonia and New Zealand.

The Egypt study involved a large number of pre-service and in-service teachers split 60:40 in favor of pre-service teachers (Gebril and Brown, 2014). Again, the New Zealand model was inadmissible because of large negative error variance and a correlation r > 1.00 between two of the factors; this indicates too many factors had been specified. A hierarchical model of three inter-correlated factors retained all 27 items according to the original factors. The Student Accountability factor moved under the Improvement factor as a subordinate first-order factor instead of being a stand-alone factor. The items for Describe loaded directly onto Improvement. Hence, this model retained all items and all factors as per the New Zealand model, except for the changed location of one factor. The model had strong equivalence between pre-service and in-service teachers.

The India study involved a large sample of high school and senior high school teachers working in private schools (Brown et al., 2015). The New Zealand model was inadmissible because of large negative error variances. The study had used a set of items developed as part of the Chinese-Teacher Conceptions of Assessment inventory (Brown et al., 2011a). Three of those items along with two new items created a new factor. Of the 27 TCoA-IIIA items, three inter-correlated factors were made (i.e., 8 items from Improvement, 7 items from Irrelevant, and 6 items from School and Student Accountability and Improvement). Thus, 21 of the original 27 items were retained, but only Improvement and Irrelevant items were retained within their overall macro-construct.

The Ecuador study was conducted in Spanish and attempted to validate the TCoA-IIIA with Remesal's Qualitative Model of Conceptions of Assessment (Brown and Remesal, 2017). The hierarchical structure of the TCoA was inadmissible due to negative error variances and positive not definite covariance matrix. After removing three first-order factors beneath Improvement (except Teaching), merging the two accountability factors, and splitting the Irrelevance factor into Irrelevance and Caution, an acceptably fitting model consisting of 25 items organized in four factors with one subordinate factor was determined. The Teaching factor was predicted by both Improvement and Caution and the Irrelevance factor pointed to the three Student Accountability items, one item in Teaching and one item in Improvement.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is a sophisticated causal-correlational technique to detect and evaluate the quality of a theoretically informed model relative to the data set of responses. CFA explicitly specifies in advance the proposed paths among factors and items, normally limiting each item to only one factor and setting the loading to all other factors at zero (Hoyle, 1995; Klem, 2000; Byrne, 2001). Unlike correlational or regression analyses, CFA determines the estimates of all parameters (i.e., regressions from factors to items, the intercept of items at the factor, the covariance of factors, and the unexplained variances or residuals in the model) simultaneously, and provides statistical tests that reveal how close the model is to the data set (Klem, 2000). While the response options are ordinal, all estimations used maximum likelihood estimation because this estimator is appropriate for scales with five or more options (Finney and DiStefano, 2006; Rhemtulla et al., 2012).

The determination as to whether a statistical model accurately reflects the characteristics of the data requires inspection of multiple fit indices (Hu and Bentler, 1999; Fan and Sivo, 2005). Unfortunately, not all fit indices are stable under different model conditions (e.g., the χ2 test is very sensitive in large models, the CFI rejects complex models, the RMSEA rejects simple models; Fan and Sivo, 2007). Two levels of fit are generally discussed; “acceptable” fit can be imputed if RMSEA is < 0.08, SRMR is ≈ 0.06, gamma hat and CFI are > 0.90, and χ2/df is < 3.80; while, “good” fit can be imputed when RMSEA is < 0.05, SRMR < 0.06, gamma hat and CFI are > 0.95, and χ2/df is < 3.00 (Cheung and Rensvold, 2002; Hoyle and Duvall, 2004; Marsh et al., 2004; Fan and Sivo, 2007). If the model fits the data, then the model does not need to be rejected as an accurate simplification of the data.

Since each study had developed a variation on the original TCoA-IIIA statistical model, it was decided that each model should be tested in confirmatory factor analysis for equivalence. The invariance of a model across subgroups can be tested using a multiple-group CFA (MGCFA) approach with nested model comparisons (Vandenberg and Lance, 2000). Equivalence in a model between groups is accepted if the difference in model parameters between groups is so small that the difference is attributable to chance (Hoyle and Smith, 1994; Wu et al., 2007). If the model is statistically invariant between groups, then it can be argued that any differences in factor scores are attributable to characteristics of the groups rather than to any deficiencies of the statistical model or inventory. Furthermore, invariance indicates that the two groups are drawn from equivalent populations (Wu et al., 2007), making comparisons appropriate. The greater the difference in context for each population, the less likelihood participants will respond in an equivalent fashion, suggesting that context changes responding to and meaning of items across jurisdictions.

In order to make mean score comparisons between groups, a series of nested tests is conducted. First, the pattern of fixed and free factor loadings among and between factors and items has to be the same (i.e., configural invariance) for each group (Vandenberg and Lance, 2000; Cheung and Rensvold, 2002). The regression weights from factors to items should vary only by chance; equivalent regression weights (i.e., metric invariance) are indicated if the change in CFI compared to the previous model is small (i.e., ΔCFI ≤ 0.01) (Cheung and Rensvold, 2002). Third, the regression intercepts of items upon factors should vary only by chance; again equivalent intercepts (i.e., scalar invariance) is indicated if ΔCFI ≤ 0.01. Equivalence analysis stops if each subsequent test fails or if the model is shown to be improper for either group. Strictly, configural, metric, and scalar invariance are required to indicate invariance of measurement and permit group comparisons (Vandenberg and Lance, 2000).

When negative error variances and positive not-definite covariance matrices are discovered the model is not admissible for the group concerned. However, negative error variances can occur through chance processes; these can be corrected to a small positive value (e.g., 0.005) if twice the standard error exceeds the value of the negative error indicating that the 95% confidence interval crosses the zero line into positive territory (Chen et al., 2001).

Models that are not admissible in one or more groups cannot be used to compare groups. Likewise, those which do not meet conventional standards of fit cannot be used to compare groups. Finally, those that are not scalar equivalent cannot be used to compare groups. Each model reported here is tested in an 11-group confirmatory factor analysis seeking to establish degree of equivalence or admissibility. Further, because jurisdictions can be classified as low or high-stakes exam societies equivalence is tested within each group of countries.

Analyses were conducted with eight different jurisdictions, 11 data sets (two teacher levels were present in three jurisdictions), and ten different statistical models. Three of the models were from New Zealand (i.e., hierarchal nine inter-correlated factors, nine inter-correlated factors, and four inter-correlated factors), while the seven remaining models came from the seven other jurisdictions.

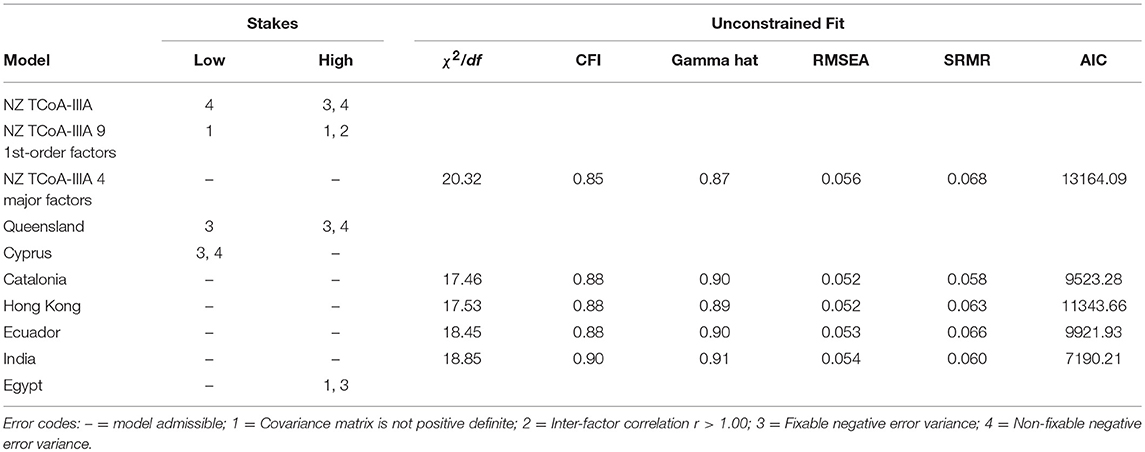

Each of the 10 models was tested with MGCFA on the 11 data sets (Table 3). Out of the 110 possible results, there were 20 instances of a not positive definite covariance matrix, 18 cases of factor inter-correlations being >1.00, 30 negative error variances that could be fixed because the 95% confidence interval crossed zero, 12 cases of non-fixable negative error variances, and one unspecified inadmissible solution. All but one model had at least one source of inadmissibility in at least one group, meaning that those models could not be deemed to be usable across all data sets. Ten cells were characterized by only fixable negative error variances; however, at least one other jurisdiction had a non-fixable error for that model, meaning that even if the error variance were fixed the model would still not be admissible for at least one group. Interestingly, one model was unidentifiable (i.e., the four factor NZ model) and only one model was admissible across all data sets (i.e., India model).

The India model had the fewest factors and items which may have contributed to its admissibility across jurisdictions. In an 11-group MGCFA, this model had acceptable levels of fit (χ2/df = 4.32, p = 0.04; RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.023 (0.023–0.024); CFI = 0.82; gamma hat = 0.91; SRMR = 0.058; AIC = 9829.79). This indicates that there was configural invariance; however, constraining regression weights to equivalence produced ΔCFI = 0.031. Consequently, this model is not invariant across the groups despite its admissibility and configural equivalence. Thus, none of these models work across all data sets clearly supporting the idea that context makes the statistical models different and non-comparable.

Each of the four jurisdictions within low and high-stakes conditions was tested with MGCFA on the statistical models originating within those jurisdictions. This means that the four low-stakes environments were tested with three New Zealand models and three additional models arising from those three other jurisdictions. As expected, restricting the number of datasets being compared did not change the problems identified with models per jurisdiction indicated in Table 3.

Extending this comparative logic, it was decided to forego jurisdictional information and merge all the data according to whether the country was classified as low or high-stakes. This produced a two-group comparison for low- or high-stakes conditions (Table 4). In this circumstance, after eliminating between country differences, five different models were admissible. However, those models had poor (i.e., New Zealand and Hong Kong) to acceptable (i.e., Catalonia, Ecuador, and India) levels of fit. Inspection of fit indices for these five models indicates that the India model had the best fit by large margins (i.e., ΔAIC = 2333.07; Burnham and Anderson, 2004). Invariance testing of the India model with the low vs. high-stakes groups failed to demonstrate metric equivalence (i.e., ΔCFI = 0.011) compared to the unconstrained configurally equivalent model.

Table 4. Model admissibility by overall stakes with unconstrained fit statistics for admissible models.

Data from a range of pre-service and in-service teachers has been obtained using the TCoA-IIIA inventory. This analysis has made use of data from eight different educational jurisdictions with 11 samples of teachers (i.e., primary, secondary, and senior secondary), and with 10 different statistical models. It is worth noting that except for a few jurisdictions, the obtained samples were largely obtained through convenience processes, reducing the generalizability of the results even to the jurisdiction from which the data were obtained. Thus, the published results may not be representative and this status may contribute to the inability to derive a universal model.

All models, except one, were inadmissible for a variety of reasons (i.e., covariance matrix not positive definite and inter-factor correlations >1.00). These most likely arise as a consequence of having too many factors specified in the statistical model. The India model, consisting of just three factors and 21 items, was admissible across all jurisdictions, with acceptable to good levels of fit. However, this model was only configurally invariant across the 11 data sets. Generally, when multiple groups are considered, measurement invariance usually fails (Marsh et al., 2018). Thus, the comparability of a model across such diverse contexts and populations is understandably unlikely.

It is also worth noting that the standards used in this study to evaluate equivalence in multi-group comparisons rely on conventional standards and approaches (Byrne, 2004). More recently, the use of permutation tests has been proposed as a superior method for testing metric and scalar invariance, because permutations can control Type I error rates better than the conventional approaches used in this study (Jorgensen et al., 2018; Kite et al., 2018). Combined with determination of effect sizes for metric and scalar equivalence tests (dMACS) (Nye and Drasgow, 2011), these are methodological approaches that may lead future analyses to identification of more universal results.

It is noteworthy that ignoring the specifics of individual jurisdictions by aggregating responses according to the assessment policy framework (i.e., low-stakes vs. high-stakes) led to five admissible models. Again, the India model was the best fitting with better fit than in the 11 data set analysis. However, even in this situation, no metric or weak equivalence between the two groups was achieved. This situation suggests that it may be that the notion of high vs. low-stakes is too coarse a framework for identifying patterns in teacher conceptions of assessment. It is possible that teachers' conceptions of teaching (Pratt, 1992), learning (Tait et al., 1998), or curriculum (Cheung, 2000) might be more effective in identifying commonalities in how teachers conceive of assessment across nations, levels, or regions. Clustering New Zealand primary school teachers on their mean scores for assessment, teaching, learning, curriculum, and self-efficacy revealed five clusters with very different patterns of scores (Brown, 2008). This approach focuses much more at the level of the individual than the system and may be productive in understanding conceptions of assessment.

It is possible to see in the various studies reported here that many of the items in the TCoA-IIIA do inter-correlate according to the original factor model. This suggests that the items do have strong within factor coherence. The India model aggregates 21 of the 27 TCoA-IIIA items into three major categories, two of which (i.e., Improvement and Irrelevance) are made up of items drawn only from the same major factors described in the original New Zealand TCoA-IIIA analyses. This set of 15 items gives some grounds for suggesting that there is a core set of items which constitute potentially universally generalizable items. There is also some suggestion that an accountability use of assessment factor could be constructed from the student and school accountability items. Future cross-cultural research could plausibly rely on those two scales in efforts to investigate how teacher conceive of assessment.

Thus, it seems the more complex a model is, the less likely it will be generalizable across contexts. The India model is just 3 inter-correlated factors and only 21 items, while most of the other models are hierarchical creating complex inter-connections among factors and thus indicating quite nuanced and complex ideas among teachers. The briefer India model also sacrifices some of the richness available in the larger instrument set. It seems likely that even small differences in environments can produce non-invariance in statistical models. For example, the New Zealand primary teacher model replicated itself with New Zealand secondary teachers (Brown, 2011), Queensland primary teachers (Brown, 2006), but not with Queensland secondary teachers (Brown et al., 2011b). Thus, the less informative and subtle a model is the more likely it will replicate. However, the researcher is likely to lose useful and important information within the new context.

The conclusion that has to be drawn here is that the original statistical model of the TCoA-IIIA inventory, developed in New Zealand and validated with Queensland primary teachers, is not universal or generalizable. This makes clear the importance of systematically evaluating research inventories when they are adopted as research tools in new contexts; a point made clear in a New Zealand-Louisiana comparative study (Brown et al., 2017). Hence, in most of the studies reported here, different models were necessary to capture the impact of the different ecology upon teacher conceptions of assessment and all but one of those models was non-invariant in other contexts. The various revised models of the TCoA-IIIA as published in the studies included here show that the make-up and inter-relationships of the proposed scales is entirely sensitive to ecological priorities and practices in the specific environment and even with the specific teacher group. This lack of equivalence appears across jurisdictions with different contextual frameworks. Moreover, even within societies, teachers at different levels of schooling vary with respect to the structure of their assessment conceptions

Hence, comparative research with the TCoA-IIIA inventory makes clear that how teachers conceive of assessment depends on the specificity of contexts in which teachers work. Nonetheless, it would appear, consistent with general reviews of this field (Barnes et al., 2015; Bonner, 2016), that the TCoA-IIIA items related to the improvement and irrelevance functions of assessment, especially captured in the India model, have substantial power as research tools in a wide variety of educational contexts.

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author. NZ primary data are available online at: https://doi.org/10.17608/k6.auckland.4264520.v1; NZ secondary data are available online at: https://doi.org/10.17608/k6.auckland.4284509.v1.

The original research into the TCoA was conducted with approval from the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee 2001/1596. The current paper uses secondary analysis of data made available to the authors.

GB devised TCoA, conducted analyses, and drafted the manuscript. AG and MM contributed data, verified analyses, reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Funding for APC fees received from University of Umeå Library.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The assistance of Joohyun Park, doctoral student at The University of Auckland, in running multiple iterations of the data analysis and preparing data tables is acknowledged.

Ashita, R. (2013). Beyond testing and grading: using assessment to improve teaching-learning. Res. J. Educ. Sci. 1, 2–7.

Barnes, N., Fives, H., and Dacey, C. M. (2015). “Teachers' beliefs about assessment,” in International Handbook of Research on Teacher Beliefs, eds H. Fives and M. Gregoire Gill (New York, NY: Routledge), 284–300.

Berry, R. (2011a). “Assessment reforms around the world,” in Assessment Reform in Education: Policy and Practice, eds R. Berry and B. Adamson (Dordrecht, NL: Springer), 89–102.

Berry, R. (2011b). Assessment trends in Hong Kong: seeking to establish formative assessment in an examination culture. Assess. Educ. Policy Princ. Pract. 18, 199–211. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2010.527701

Bonner, S. M. (2016). “Teachers' perceptions about assessment: competing narratives,” in Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment, eds G. T. L. Brown and L. R. Harris (New York, NY: Routledge), 21–39.

Brown, G. T., and Remesal, A. (2012). Prospective teachers' conceptions of assessment: a cross-cultural comparison. Span. J. Psychol. 15, 75–89. doi: 10.5209/rev_SJOP.2012.v15.n1.37286

Brown, G. T. L. (2002). Teachers' Conceptions of Assessment. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Auckland, Auckland. Available online at: http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/63

Brown, G. T. L. (2003). Teachers' Conceptions of Assessment Inventory-Abridged (TCoA Version 3A) [Measurement Instrument]. figshare. Auckland: University of Auckland. doi: 10.17608/k6.auckland.4284506.v1

Brown, G. T. L. (2004a). Measuring attitude with positively packed self-report ratings: comparison of agreement and frequency scales. Psychol. Rep. 94, 1015–1024. doi: 10.2466/pr0.94.3.1015-1024

Brown, G. T. L. (2004b). Teachers' conceptions of assessment: implications for policy and professional development. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 11, 301–318. doi: 10.1080/0969594042000304609

Brown, G. T. L. (2006). Teachers' conceptions of assessment: validation of an abridged instrument. Psychol. Rep. 99, 166–170. doi: 10.2466/pr0.99.1.166-170

Brown, G. T. L. (2008). Conceptions of Assessment: Understanding What Assessment Means to Teachers and Students. New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

Brown, G. T. L. (2011). Teachers' conceptions of assessment: comparing primary and secondary teachers in New Zealand. Assess. Matters 3, 45–70.

Brown, G. T. L. (2016). “Improvement and accountability functions of assessment: impact on teachers' thinking and action,” in Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory, ed A. M. Peters (Singapore: Springer), 1–6.

Brown, G. T. L. (2017). Codebook/Data Dictionary Teacher Conceptions of Assessment. figshare. Auckland: The University of Auckland. doi: 10.17608/k6.auckland.4284512.v3

Brown, G. T. L., Chaudhry, H., and Dhamija, R. (2015). The impact of an assessment policy upon teachers' self-reported assessment beliefs and practices: a quasi-experimental study of Indian teachers in private schools. Int. J. Educ. Res. 71, 50–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2015.03.001

Brown, G. T. L., and Harris, L. R. (2009). Unintended consequences of using tests to improve learning: how improvement-oriented resources engender heightened conceptions of assessment as school accountability. J. Multidiscip. Eval. 6, 68–91.

Brown, G. T. L., Harris, L. R., O'Quin, C., and Lane, K. E. (2017). Using multi-group confirmatory factor analysis to evaluate cross-cultural research: identifying and understanding non-invariance. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 40, 66–90. doi: 10.1080/1743727X.2015.1070823

Brown, G. T. L., Hui, S. K. F., Yu, F. W. M., and Kennedy, K. J. (2011a). Teachers' conceptions of assessment in Chinese contexts: a tripartite model of accountability, improvement, and irrelevance. Int. J. Educ. Res. 50, 307–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2011.10.003

Brown, G. T. L., Kennedy, K. J., Fok, P. K., Chan, J. K. S., and Yu, W. M. (2009). Assessment for improvement: understanding Hong Kong teachers' conceptions and practices of assessment. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 16, 347–363. doi: 10.1080/09695940903319737

Brown, G. T. L., Lake, R., and Matters, G. (2011b). Queensland teachers' conceptions of assessment: the impact of policy priorities on teacher attitudes. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.003

Brown, G. T. L., and Michaelides, M. (2011). Ecological rationality in teachers' conceptions of assessment across samples from Cyprus and New Zealand. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 26, 319–337. doi: 10.1007/s10212-010-0052-3

Brown, G. T. L., and Remesal, A. (2017). Teachers' conceptions of assessment: comparing two inventories with Ecuadorian teachers. Stud. Educ. Eval. 55, 68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.07.003

Burnham, K. P., and Anderson, D. R. (2004). Multimodel inference: understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociol. Methods Res. 33, 261–304. doi: 10.1177/0049124104268644

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural Equation Modeling With AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. Mahwah, NJ: LEA.

Byrne, B. M. (2004). Testing for multigroup invariance Using AMOS graphics: a road less traveled. Struct. Equat. Model. 11, 272–300. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem1102_8

Carless, D. (2011). From Testing to Productive Student Learning: Implementing Formative Assessment in Confucian-Heritage Settings. London: Routledge.

Chen, F., Bollen, K. A., Paxton, P., Curran, P. J., and Kirby, J. B. (2001). Improper solutions in structural equation models: causes, consequences, and strategies. Sociol. Methods Res. 29, 468–508. doi: 10.1177/0049124101029004003

Cheung, D. (2000). Measuring teachers' meta-orientations to curriculum: application of hierarchical confirmatory analysis. J. Exp. Educ. 68, 149–165. doi: 10.1080/00220970009598500

Cheung, G. W., and Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equat. Model. 9, 233–255. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Cheung, T. K.-Y. (2008). An assessment blueprint in curriculum reform. J. Qual. Sch. Educ. 5, 23–37.

Choi, C.-C. (1999). Public examinations in Hong Kong. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 6, 405–417.

Crooks, T. J. (2010). “Classroom assessment in policy context (New Zealand),” in The International Encyclopedia of Education, 3rd Edn, eds B. McGraw, P. Peterson, and E. L. Baker (Oxford: Elsevier), 443–448.

Curriculum Development Council (CDC) (2001). Learning to Learn: Lifelong Learning and Whole-Person Development. Hong Kong: CDC.

Cyprus Ministry of Education and Culture (2002). Elementary Education Curriculum Programs [Analytika Programmata Dimotikis ekpedefsis]. Nicosia: Ministry of Education and Culture.

Fan, X., and Sivo, S. A. (2005). Sensitivity of fit indexes to misspecified structural or measurement model components: rationale of two-index strategy revisited. Struct. Equat. Model. 12, 343–367. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem1203_1

Fan, X., and Sivo, S. A. (2007). Sensitivity of fit indices to model misspecification and model types. Multivar. Behav. Res. 42, 509–529. doi: 10.1080/00273170701382864

Finney, S. J., and DiStefano, C. (2006). “Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling,” in Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course, eds G. R. Hancock and R. D. Mueller (Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing), 269–314.

Fives, H., and Buehl, M. M. (2012). “Spring cleaning for the “messy” construct of teachers' beliefs: What are they? Which have been examined? What can they tell us?” in APA Educational Psychology Handbook: Individual Differences and Cultural and Contextual Factors, Vol. 2, eds K. R. Harris, S. Graham, and T. Urdan (Washington, DC: APA), 471–499.

Fulmer, G. W., Lee, I. C. H., and Tan, K. H. K. (2015). Multi-level model of contextual factors and teachers' assessment practices: an integrative review of research. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 22, 475–494. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2015.1017445

Gebril, A. (2019). “Assessment in primary schools in Egypt,” in Bloomsbury Education and Childhood Studies, ed M. Toprak (London: Bloomsbury).

Gebril, A., and Brown, G. T. L. (2014). The effect of high-stakes examination systems on teacher beliefs: Egyptian teachers' conceptions of assessment. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 21, 16–33. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2013.831030

Gebril, A., and Eid, M. (2017). Test preparation beliefs and practices: a teacher's perspective. Lang. Assess. Q. 14, 360–379. doi: 10.1080/15434303.2017.1353607

Hargreaves, E. (2001). Assessment in Egypt. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 8, 247–260. doi: 10.1080/09695940124261

Hoyle, R. H. (1995). “The structural equation modeling approach: basic concepts and fundamental issues,” in Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications, ed R. H. Hoyle (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 1–15.

Hoyle, R. H., and Duvall, J. L. (2004). “Determining the number of factors in exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis,” in The SAGE Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for Social Sciences, ed D. Kaplan (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 301–315.

Hoyle, R. H., and Smith, G. T. (1994). Formulating clinical research hypotheses as structural equation models - a conceptual overview. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 62, 429–440. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.62.3.429

Hu, L.-T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equat. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Jorgensen, T. D., Kite, B. A., Chen, P. Y., and Short, S. D. (2018). Permutation randomization methods for testing measurement equivalence and detecting differential item functioning in multiple-group confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol. Methods 23, 708–728. doi: 10.1037/met0000152

Kennedy, K. J., Chan, J. K. S., and Fok, P. K. (2011). Holding policy-makers to account: exploring ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ policy and the implications for curriculum reform. Lond. Rev. Educ. 9, 41–54. doi: 10.1080/14748460.2011.550433

Kite, B. A., Jorgensen, T. D., and Chen, P. Y. (2018). Random permutation testing applied to measurement invariance testing with ordered-categorical indicators. Struct. Equat. Model. 25, 573–587. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2017.1421467

Klem, L. (2000). “Structural equation modeling,” in Reading and Understanding More Multivariate Statistics, eds L. G. Grimm and P. R. Yarnold (Washington, DC: APA), 227–260.

Lam, T. C. M., and Klockars, A. J. (1982). Anchor point effects on the equivalence of questionnaire items. J. Educ. Meas. 19, 317–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3984.1982.tb00137.x

Ley de Ordenación General del Sistema Educativo (1990). Ley Orgánica 1/1990, de 3 de octubre, BOE n° 238, de 4 de octubre de 1990.

Marsh, H. W., Guo, J., Parker, P. D., Nagengast, B., Asparouhov, T., Muthén, B., et al. (2018). What to do when scalar invariance fails: the extended alignment method for multi-group factor analysis comparison of latent means across many groups. Psychol. Methods 23, 524–545. doi: 10.1037/met0000113

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K.-T., and Wen, Z. (2004). In search of golden rules: comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler's (1999) findings. Struct. Equat. Model. 11, 320–341. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2

Michaelides, M. P. (2008). “Test-takers perceptions of fairness in high-stakes examinations with score transformations,” in Paper Presented at the Biannual Meeting of the International Testing Commission (Liverpool).

Michaelides, M. P. (2014). Validity considerations ensuing from examinees' perceptions about high-stakes national examinations in Cyprus. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 21, 427–441. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2014.916655

Ministry of Education (1993). The New Zealand Curriculum Framework: Te Anga Marautanga o Aotearoa. Wellington, NZ: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education (2007). The New Zealand Curriculum for English-Medium Teaching and Learning in Years 1-13. Wellington, NZ: Learning Media.

NUEPA (2014). Secondary Education in India: Progress Toward Universalisation (Flash Statistics). New Delhi: National University of Educational Planning and Administration.

Nye, C. D., and Drasgow, F. (2011). Effect size indices for analyses of measurement equivalence: understanding the practical importance of differences between groups. J. Appl. Psychol. 96, 966–980. doi: 10.1037/a0022955

OECD (2016). Making Education Count for Development: Data Collection and Availability in Six PISA for Development Countries. Paris: OECD.

Papanastasiou, E., and Michaelides, M. P. (2019). “Issues of perceived fairness in admissions assessmentsin small countries: the case of the republic of Cyprus,” in Higher Education Admissions Practices: An International Perspective, eds M. E. Oliveri and C. Wendler (Cambridge University Press).

Pratt, D. D. (1992). Conceptions of teaching. Adult Educ. Q. 42, 203–220. doi: 10.1177/074171369204200401

Rhemtulla, M., Brosseau-Liard, P. E., and Savalei, V. (2012). When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychol. Methods 17, 354–373. doi: 10.1037/a0029315

Rieskamp, J., and Reimer, T. (2007). “Ecological rationality,” in Encyclopedia of Social Psychology, eds R. F. Baumeister and K. D. Vohs (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 273–275.

Solomonidou, G., and Michaelides, M. P. (2017). Students' conceptions of assessment purposes in a low stakes secondary-school context: a mixed methodology approach. Stud. Educ. Eval. 52, 35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2016.12.001

Tait, H., Entwistle, N. J., and McCune, V. (1998). “ASSIST: a reconceptualisation of the approaches to studying inventory,” in Improving Student Learning: Improving Students as Learners, ed C. Rust (Oxford: Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development), 262–271.

Vandenberg, R. J., and Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organ. Res. Methods 3, 4–70. doi: 10.1177/109442810031002

Keywords: teachers, cross-cultural comparison, conceptions of assessment, confirmatory factor analysis, invariance testing

Citation: Brown GTL, Gebril A and Michaelides MP (2019) Teachers' Conceptions of Assessment: A Global Phenomenon or a Global Localism. Front. Educ. 4:16. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00016

Received: 18 October 2018; Accepted: 15 February 2019;

Published: 07 March 2019.

Edited by:

Mustafa Asil, University of Otago, New ZealandReviewed by:

Anthony Joseph Nitko, University of Pittsburgh, United StatesCopyright © 2019 Brown, Gebril and Michaelides. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gavin T. L. Brown, Z2F2aW4uYnJvd25AdW11LnNl; Z3QuYnJvd25AYXVja2xhbmQuYWMubno=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.