94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 05 November 2018

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 3 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00095

Laura Girelli1*

Laura Girelli1* Fabio Alivernini2

Fabio Alivernini2 Fabio Lucidi3

Fabio Lucidi3 Mauro Cozzolino1

Mauro Cozzolino1 Giulia Savarese4

Giulia Savarese4 Maurizio Sibilio1

Maurizio Sibilio1 Sergio Salvatore5

Sergio Salvatore5Aim: The purpose of this study was to investigate the process that lead to academic adjustment of undergraduate students in the first year of higher education, by testing a predictive model based on self-determination theory with the inclusion of self-efficacy. The model posits that perceived autonomous forms of support from parents and teachers foster autonomous motivation and self-efficacy, which in turn predict academic adjustment.

Method: A two-wave prospective design was adopted. Freshman students at an Italian university (N = 388; 73.5% females, Mage = 21.38 years ± 4.84) completed measures of autonomous motivation, perceived autonomy support from parents and teachers, self-efficacy, and intention to drop out from university at the start of their academic year. Students' past performance and socioeconomic background were also measured. At the end of the first semester, information about number of course modules passed and credits attained for each student were obtained from the department office and matched with the data collected in the first wave by an identification number.

Results: Findings of structural equation modeling analysis supported the proposed model for first-year university students, after controlling for the influence of past performance and socioeconomic background. Specifically, autonomous motivation and self-efficacy predicted dropout intention and academic adjustment a few months later. Autonomous motivation and self-efficacy were encouraged by autonomy supportive behaviors provided by teachers and parents.

Conclusion: According to our findings, in order to promote higher degree of academic adjustment in freshman students, interventions should aim to encourage autonomous motivation and self-efficacy through autonomous supportive behavior from the university and the family contexts.

A large number of students in Europe leave university without completion (Vossensteyn et al., 2015), for that reason, one of the central goals of the Europe 2020 strategy, is to increase the number of students between 30 and 34 years holding a postsecondary education qualification up to 40%, by 2020 (Vossensteyn et al., 2015). Italy is very far from this objective. In 2009, for instance, in the member countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, the population aged 25–34 with tertiary education was around 37%, while in Italy it was only 20% (OECD, 2011). As the university enrollment rates in Italy is close to the European Union (EU) average, the low amount of degree attainment seems to be due to high rates of dropout (Eurydice, 2012; Anvur, 2016). Dropout rates in Italy are one of the highest amongst the OECD countries (58% against an average of 30%; OECD, 2011). Withdrawal is particularly high among freshmen students: nearly one third of undergraduate students leave university by the end of their first year (OECD, 2011; Anvur, 2016).

Research has shown that students' motivational resources and competence beliefs in their own capabilities have a central role in predicting academic adjustment outcomes such as academic performance and persistence (Gillet et al., 2012; Fan and Williams, 2018). A theoretical framework that has shown to be valid in studying the process leading to academic adjustment outcomes of students is self- determination theory (SDT, Deci and Ryan, 1985; Ryan and Deci, 2017). SDT distinguishes between two main types of motivation as two extreme points of a continuum: intrinsic motivation, also known as self-determined or autonomous motivation, and extrinsic motivation also called controlled motivation. Individuals driven by intrinsic motivation toward a particular activity, will perform that activity for the pleasure or interest for the activity itself, whereas individuals guided by non self-determined or controlled motivation will perform the activity because they feel pressured to do so by external forces (Deci and Ryan, 2000; Ryan and Deci, 2017). Several studies in various behavioral domains have shown that autonomous motivation has a positive effect on the implementation of a behavior and on the persistence with (Girelli et al., 2016; Hagger and Chatzisarantis, 2016; Galli et al., 2018). Although most studies did investigate the academic adjustment outcomes of students from different levels of schooling in a SDT perspective, little is known about first-year undergraduate students who face specific difficulties in the transition to university, especially in Italy where, with some exceptions, university admission is not based on a test and, within the degree courses, the curricula are very strict and they do not let the students choose which lectures to follow (Aina, 2013). Therefore, the present study aimed to develop a predictive model of first-year students' academic adjustment based on SDT. Furthermore, as previous studies have found that the rising demands and academic pressure of university make it essential for students to have strong beliefs in their own abilities (Usher and Pajares, 2008; Wright et al., 2013), it was also investigated whether first-year students' competence beliefs contributed to their academic adjustment. Finally, because both students' motivation and academic competence beliefs are found to be influenced by autonomy supportive behavior, we also examined whether support for autonomy provided by teachers and parents affected students' motivation and academic self-efficacy in first-year students (Gillet et al., 2012; Fan and Williams, 2018). The purpose of the present study therefore is to examine how perceived autonomy support, autonomous motivation and self-efficacy predict undergraduate university students' early academic adjustment. Understanding how these variables affect undergraduate students' academic adjustment, particularly within the first year, could help educational institutions to support students development in order to prevent dropout from university.

In the next sections, we first introduce SDT. Then, we provide a brief literature review concerning the relationship of students' academic adjustment outcomes to academic motivation and competence beliefs and the social context that can affect these two important factors. We will then describe our model in more details, outlining the purposes and hypothesis.

A central concept for self-determination theory is the quality of motivation of an individual toward a specific activity and particularly the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (Deci and Ryan, 1985; Ryan and Deci, 2017). A person who is intrinsically motivated implements a behavior for its own pleasure, interest and satisfaction, whereas a person who is extrinsically motivated engages in an activity to obtain something in return. SDT proposes three major types of extrinsic motivation, namely external motivation, introjected motivation, and identified motivation (Ryan and Deci, 2009, 2017). In each of them, behavior is implemented with the aim of attaining instrumental goals rather than for the pleasure or interest connected to the behavior itself, however these goals vary in respect to how much they have been internalized by the individual. Individuals who are externally regulated undertake an activity in order to obtain positive results, as for example a tangible reward, or to avoid negative consequences, as for example to be yelled. According to SDT, externally regulated activities are governed by external circumstances, and individuals will cease these activities when these circumstances no longer exist (Deci and Ryan, 1985; Ryan and Deci, 2017). For instance, students are externally regulated when they enroll at a university because their parents force them to do so. On the continuum of the process of the internalization of motivation, the following point is introjected regulation, in which the individual considers relevant the maintenance or improvement of her/his self-esteem and the avoidance of a sense of guilt (Deci and Ryan, 2000; Ryan and Deci, 2009). For instance, students that go to university because they would feel guilty if they did not, have an introjected regulation. When individuals have identified regulation, they attribute a value to the behavior and they feel that the activity is important and belongs to them (Deci and Ryan, 2000; Ryan and Deci, 2009). Thus, students might enroll to a university because this is a mean to have a better job. The highest level of self-determined motivation is intrinsic regulation. Individuals who are intrinsically regulated engage in an activity for the pleasure, interest and satisfaction derived from the participation itself (Deci and Ryan, 1985; Ryan and Deci, 2017). For instance, students may go to the university because they like the course subject. Studies that have applied SDT in the education have shown that self-determined motivation is associated with a higher degree of academic adjustment in all levels of schooling. Specifically, autonomous motives are associated with greater academic persistence and better academic performance (Turner et al., 2009; Alivernini and Lucidi, 2011; Gillet et al., 2012; Alivernini et al., 2016; Fan and Williams, 2018). In the university context, Turner et al. (2009) found that intrinsic motivation predicted academic performance in undergraduate students enrolled in psychology courses; Ratelle et al. (2007), in a study on first-year college students, found that students with high levels of self-determined motivations were more persistent than students with lower levels of self-determined motivation. Autonomous motivation was also associated with dropout intention in PhD students (Litalien and Guay, 2015). These findings indirectly suggest that undergraduate students who decided to attend university for self-determined reasons will develop a higher degree of academic adjustment and will be less likely to leave university. In fact, studies have shown that autonomous forms of motivation toward a behavior are associated with the implementation of and persistence with that behavior in various contexts and in several populations (Deci et al., 2013; Cerasoli et al., 2014; Girelli et al., 2016; Hagger and Chatzisarantis, 2016; Galli et al., 2018).

In addition to autonomous motivation, students' beliefs in their own abilities have a significant role in predicting positive academic adjustment outcomes (Bandura, 1993; Usher and Pajares, 2008; Wright et al., 2013; Stinebrickner and Stinebrickner, 2014; Fan and Williams, 2018). For instance, Quiroga et al. (2013) found that academic competence beliefs predicted dropout from school in grade 7 students. Perceived self-efficacy predicted performance and persistence in high school students (Alivernini and Lucidi, 2011). Furthermore, college students' perception of academic competence at the end of their first semester was associated with persistence in their next semester, even after controlling for students' perception of academic competence on the first day of college, gender, ethnicity, first-generation status, and past performance (Wright et al., 2013). Bandura (1997) defined self-efficacy as a student's belief in his or her capability to organize and perform a specific task. Self-efficacy influences goals and level of commitment to them, the degree of motivation and dedication to face obstacles, resilience to face adversities, and causal attributions for successes and failures (Usher and Pajares, 2008). Such factors are particularly important for the critical phase that freshman students live. These findings outlined that students who believe more in their competence to manage their academic activities are likely to have higher degree of academic adjustment than low self-efficacy students even when they face difficulties.

Self-determination theory in the realm of education proposes that the interpersonal context can foster autonomous motivation and competence beliefs of an individual, this happens when the significant figures provide support for the autonomy of the individual in his social context (Deci et al., 2013; Deci and Ryan, 2016). For example, when significant others give an individual the opportunity to choose among several options, they give them a reason to implement an activity, or they accept the point of view of the individual, and provide feedback on skills, it has been shown they promote autonomous motivation and perceived competence in the individual (Hardre and Reeve, 2003; Turner et al., 2009; Gillet et al., 2012, 2017; Guay et al., 2016). A great many studies find a positive relationship between autonomy-supportive behaviors provided by teachers and parents and students' self-determined motivation and competence beliefs in the educational context (Turner et al., 2009; Fan and Williams, 2018). These results have been obtained at different stages of education, such as elementary school (Ryan and Grolnick, 1986; Grolnick and Ryan, 1989), high school (Alivernini and Lucidi, 2011; Gillet et al., 2012; Fan and Williams, 2018), college (Black and Deci, 2000; Turner et al., 2009; Jang et al., 2016; Gillet et al., 2017; Pedersen, 2017), and postgraduate education (Overall et al., 2011; Litalien and Guay, 2015). In line with these studies, undergraduate students who feel more supported in their autonomy by both parents and teachers will be more likely to enroll in university for more autonomous reasons and will also develop greater confidence in their personal capabilities. The more students attend university for more autonomous reasons and have stronger beliefs in their own capabilities, the better their academic adjustment will be.

In prior research concerning students' dropout, the factors that are prevalently considered as undergraduate students' academic adjustment outcomes are academic persistence and performance. Academic performance has been traditionally defined as exam grades or as the average value of the final grades earned in courses over time, also known as grade point average (GPA; Richardson et al., 2012; Respondek et al., 2017). However, according to Vanthournout et al. (2012), freshman coaching programs usually have the aim to support students in persisting in their program and to pass modules and not to improve students' grades. Therefore, the number of course-modules that students have passed, and corresponding credit obtained, could be a good indicator of students' academic adjustment and an early-warning sign of dropout. Consequently, due to the difficulty of measuring student persistence in a relatively short time period, we conceptualized academic adjustment as number of attained credits at the end of the first semester. So far, there have been few attempts to consider the number of credits that students have obtained as an outcome variable. For example, Vanthournout et al. (2012) found that motivation has a moderate explanatory value regarding obtaining credits.

Although prior research exists on the impact of autonomous motivation and self-efficacy on academic success and persistence in the university context, we are not aware of any studies that considered the impact of a motivational model based on SDT, with the inclusion of self-efficacy, on academic adjustment in first-year students. Our study is the first investigation that integrates SDT and self-efficacy into a unified model to explain early academic adjustment in first-year students. We suggest that first-year students, who perceive their family and academic environment as more supportive of their autonomy at the beginning of their academic year, will be more autonomously motivated toward their studies and will perceive themselves as more competent in manage academic activities. In turn, they will be less likely to develop dropout intention and, consequently, they will experience a better academic adjustment at the end of the first semester. The question we ask is whether a motivational model with the inclusion of self-efficacy can predict early academic adjustment in first-year undergraduate students.

The purpose of this study was to investigate freshman students' early adjustment by testing a predictive model based on SDT and with the inclusion of self-efficacy. Based on the theoretical assumptions discussed above, we assume the following hypothesis:

a) Students who feel more supported in their autonomy by their teachers and their parents, would develop more autonomous forms of motivation and greater self-efficacy;

b) Students attending university for more autonomous reasons and having stronger beliefs in their own abilities would be less likely to develop dropout intention;

c) Students with less intention to dropout, will develop better academic adjustment;

d) Both autonomous motivation and self-efficacy mediated the effects of perceived autonomy support on intention to dropout.

We expect these hypotheses to be confirmed even after controlling for background variables that have consistently been shown to be related to academic adjustment outcomes: students' past performance and parental education level (Alivernini and Lucidi, 2011; Aina, 2013). Support for these hypotheses would extend the results of previous research and would provide further understanding of the processes which predict early academic adjustment of first-year university students. This study will advance our understanding of motivational and social cognitive processes clarifying why some students experience better academic adjustment than other students. Until now, there have been few attempts to analyze academic adjustment outcomes of university students through SDT, focusing on self-determined motivation and self-efficacy together. Furthermore, the present model could reveal the extent to which these two constructs are affected differently from the two social contexts in which the individual lives: the family and the university contexts. This could extend our knowledge of the determinants of motivation and self-efficacy beliefs proposed by SDT and social cognitive theory (SCT) as well as the consequences of these beliefs for students' behavior. Lastly, we test these hypotheses in first-year students for whom, due to the challenges and difficulties of entering university, motivation and self-efficacy beliefs may be more solicited.

At the start of the academic year (Time 1), an email was sent to all freshman students enrolled in an Italian University. They all were invited to fill out an online questionnaire lasting about 40 min. The questionnaire was made by Google forms. We subsequently used different reminder strategies to solicit students: a private message on the home page of their personal web portal (a portal provided to all students that delivers official communications to students), a direct invitation made personally to the class for several degree courses, an invitation to students' elected representatives to ask for their help in recruiting, and several invitations with the link to the online questionnaire posted on the social media group page of different degree courses. A total of 388 students completed the online questionnaire. Mean age of participants was 21.38 years (SD = 4.84) and 73.5% of them were female. At the end of the first semester (Time 2—about 4 months later), information about number of credits attained for each student who completed the questionnaire was collected from the department office and matched with the data collected at Time 1 by an identification number. Questionnaires were completed anonymously to preserve confidentiality and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Perceived autonomy support from parents was measured at Time 1 using an adapted version of the Perceived Autonomy Support Scale for Exercise Settings (PASSES, Hagger et al., 2007). An adapted version of the scale that considered parents as a source of autonomy support was already used in a previous study conducted in an Italian sample of adolescents (Girelli et al., 2016). The scale used in this study comprised 10 items (e.g., “I feel that my parents provide me with the opportunity to choose what to do in my life”) with responses made on seven-point Likert-type scales from does not correspond at all (1) to corresponds exactly (7). Higher scores represent a higher level of perceived autonomy support in the family context.

The short version of the Learning Climate Questionnaire (LCQ, Williams and Deci, 1996) was administered at Time 1 to assess students' perceptions of autonomy support provided by their teachers. The scale comprised 6 items that measure the degree to which students perceive their teachers as supporting their autonomy (e.g., “I feel that my teachers provides me choices and options about how to study a topic”), on 5-point Likert-type scales ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) Higher scores represent a higher level of perceived autonomy support in the university context.

Students' self-efficacy with regard to academic activities was measured at Time 1, using an adapted version of the Perceived Efficacy Scale for Self-Regulated Learning (Bandura, 1990), validated for Italian samples (Bandura et al., 1996). The scale consisted of 9 items measuring students' self-efficacy regarding planning and organizing different academic activities (e.g., “How well can you organize your academic activities?”), completing academic assignments within deadlines (e.g., “How well can you finish the program in time for an exam?”), and regulating their motivation for academic pursuits (“How well can you study when there are other interesting things to do”). We used a 7-point Likert-type scale that ranged from not able to do it at all (1) to able to do it at all (7). A higher score represents a higher level of self-efficacy.

Motivation for attending university was measured at Time 1 using the Academic Self-Regulation Questionnaire (A-SRQ, Ryan and Connell, 1989). The scale comprised 16 items that referred to several reasons why students decided to sign up for university, four items for each regulation style: intrinsic regulation (e.g., “… because I like the subject”), identified regulation (e.g., “… because it is important for my future”) introjected regulation (e.g., “…because it would make me feel proud of myself”), and external regulation (e.g., “…because it's what I'm supposed to do”). Students were asked to rate each item on seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from does not correspond at all (1) to corresponds exactly (7). A short version of the scale was validated in an Italian sample and showed good psychometric characteristics (Alivernini et al., 2008, 2017).

Intention to drop out from university studies was measured at Time 1 by four items (e.g., “I sometimes consider dropping out of university,”) with responses given on seven-point Likert-type scales ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7).

The measure of past performance used in this study was students' high-school final grade. At the beginning of their academic year (Time 1), students were asked to report their final grade in high-school. In the Italian educational system, the final grade—called the voto di maturità—ranges from 60 to 100.

At Time 1, students were asked to report the highest level of education successfully completed by their father and their mother; the highest level among them was the parental education level. It ranges from middle school diploma to graduation. A greater number corresponds to higher educational level.

Academic adjustment was operationalized through students' cumulative credit points attained. After the introduction of the European Credit Transfer System (ECTS, Souto-Inglesias and Baeza_Romero, 2018), it is recognized that attaining credits is becoming more important for students than GPA (Vanthournout et al., 2012). The number of attained credits for each study participant was obtained from the department office at the end of the first semester (Time 2). It represents students' total number of attained credits for each course-module that they have passed. A greater number of attained credits reflects higher academic adjustment, whereas fewer credits attained reflects lower academic adjustment.

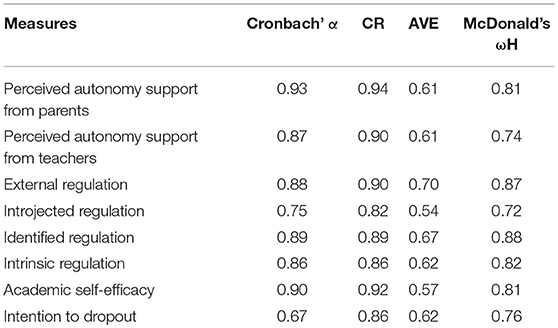

First, in order to estimate the internal consistency of the measures used in the study, we calculated the Cronbach's Alpha (α), the Composite Reliability (CR), the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) (Raykov, 1997), and the McDonald's Omega for all the scales (McDonald, 1999). The latter was computed using R project (R Core Tem, 2017). Second, the four subscales of the A-SRQ were collapsed into a single index of autonomous motivation, called Relative Autonomy Index (RAI, Vallerand and Ratelle, 2002). In order to compute the RAI, weights were assigned to each of the items according to their position on the continuum, following Grolnick and Ryan (1987) and Vallerand and Ratelle (2002) procedure. Therefore, items from the intrinsic motivation scale were assigned a weight of +2, identified regulation items a weight of +1, introjected regulation items a weight of−1 and external regulation items a weight of −2. All the resulting weighted item scores were then multiplied to produce a composite parceled item score for the indication of a latent RAI factor. As there were four items for each scale, four parceled RAI items were produced using this system. Therefore, each parceled item reflected a participant's degree of relative autonomy with high scores representing higher levels of autonomous motivation. These parcels were used as indicators of a single latent RAI factor according to the procedure used in previous studies (Hagger et al., 2006; Girelli et al., 2016; Galli et al., 2018).

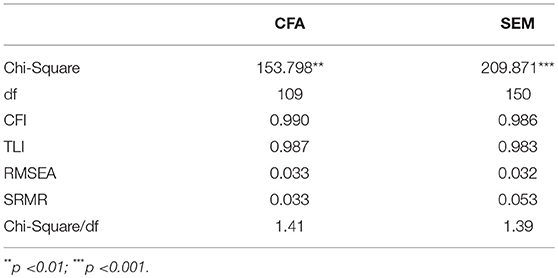

Data were analyzed by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with latent variables to test for the construct and discriminant validity of the study measures for each sample. The hypothesized relations among all the variables measured at Time 1—perceived autonomy support from parents and from teachers, self-efficacy, autonomous motivation and intention—and academic achievement recorded at Time 2, were tested in a Structural Equation Model (SEM) with Mplus program (Muthén and Muthén, 2012). Past performance and parental education level were included as control variables which predicted all other variables in the model (Hagger et al., 2015; Girelli et al., 2016). Goodness-of-fit of the proposed model with the data was evaluated using multiple goodness of fit recommended indexes: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Standardized Root Mean Squared Residuals (SRMR) and the Chi square/df ratio. Cut-off values of 0.90 or above for the CFI indicated acceptable models, although values >0.95 were preferable, values of 0.08 or less for the RMSEA and the SRMR, and values of 2 of less for the chi square/df ratio were deemed satisfactory for well-fitting models (Hu and Bentler, 1999; Tabachnick and Fidell, 2006). Finally, following Preacher and Hayes' procedure Preacher and Hayes (2008), hypothesized mediation effects of RAI and self-efficacy were tested by calculating indirect effects and 95% confidence intervals using a bootstrapped resampling method with 5,000 resamples. Mediation was confirmed by the presence of a statistically significant bootstrapped indirect effect.

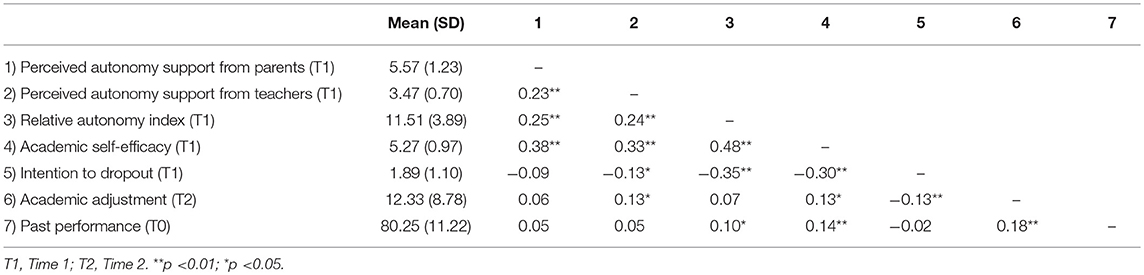

Three hundred and eighty-eight freshman students completed the questionnaire at Time 1 (Mage = 21.38 years; SD = 4.84; 73.5% female). From all the students who completed the questionnaire at Time 1, only 317 of them passed at least one module in the first semester; 71 students did not take or pass any exam. Cronbach's Alpha (α), Composite Reliability (CR), Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and McDonald's Omega (ωH) for all the scales used in the study are reported in Table 1. Zero-order correlations between age and academic achievement and all the key variables of the study were not statistically significant except for the statistically significant and negative correlation between age and perceived autonomy support from teachers: older students felt less supported by their teachers (r = −0.12, p < 0.05). Univariate analyses of variance of the effect of gender distribution on academic adjustment and on all the key variables of the study showed no significant gender difference on academic adjustment, intention to drop out and perceived autonomy support from teachers, and statistically significant gender effects on autonomous motivation [F(1, 386) = 14.328; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.03], self-efficacy [F(1, 386) = 14.181; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.03] and perceived autonomy support from parents [F(1, 386) = 6.347; p < 0.05; η2 = 0.01], with female students more autonomously motivated (M = 11.95; SD = 3.56), more confident in their capabilities (M = 5.38; SD = 0.92) and more likely to feel supported by their parents (M = 5.66; SD = 1.22) than male students (autonomous motivation: M = 10.27; SD = 4.47; self-efficacy: M = 4.96; SD = 1.05; perceived autonomy support from parents: M = 5.31; SD = 1.21). Univariate analyses of variance of the effect of parental education level on academic adjustment and on all the key variables of the study showed only a statistically significant effects of parents' level of education on academic adjustment [F(1, 386) = 7.701; p < 0.05; η2 = 0.01], with students having parents with a higher level of education, having higher academic adjustment (middle school diploma: M = 11.39; SD = 8.72; high-school diploma: M = 11.94; SD = 8.61; graduation: M = 14.67; SD = 8.96). Descriptive statistics and zero-order intercorrelations among all the key variables of the study are reported in Table 2.

Table 1. Cronbach's Alpha, Composite Reliability (CR), Average Variance Extracted (AVE), and McDonald's Omega for the measures used in the study.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations of the key variables of the study measured at Time 1, the academic adjustment recorded at Time 2 and the past performance at Time 0.

Goodness of fit indexes for the CFA and the SEM are given in Table 3. The fit of the models for the CFA and the SEM met the multiple criteria for adequate model fit. Overall, both for CFA and SEM models, factor loadings of each latent variable were statistically significant (p < 0.001) and above 0.45, which is above the minimum value (0.32) cited as the minimum acceptable criterion for a factor loading (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2006).

Table 3. Goodness of fit indexes of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM) for the tested model.

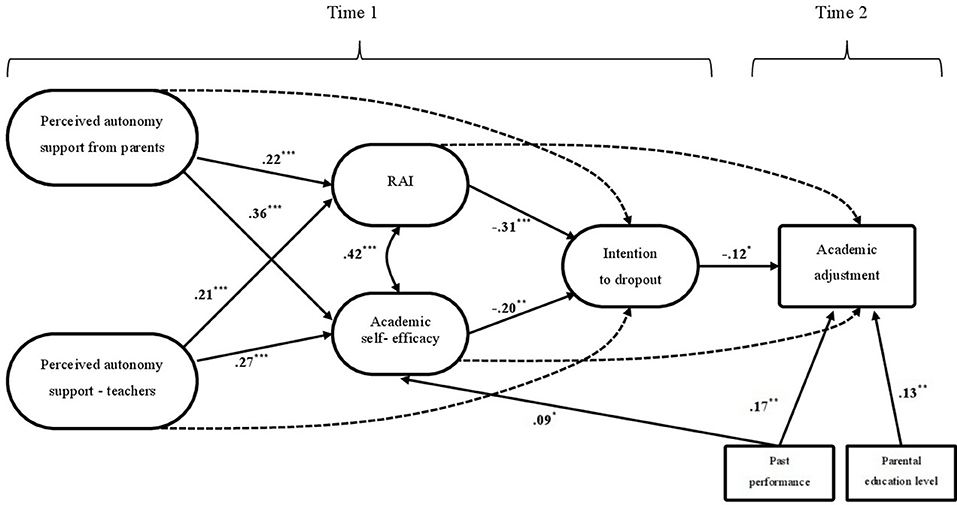

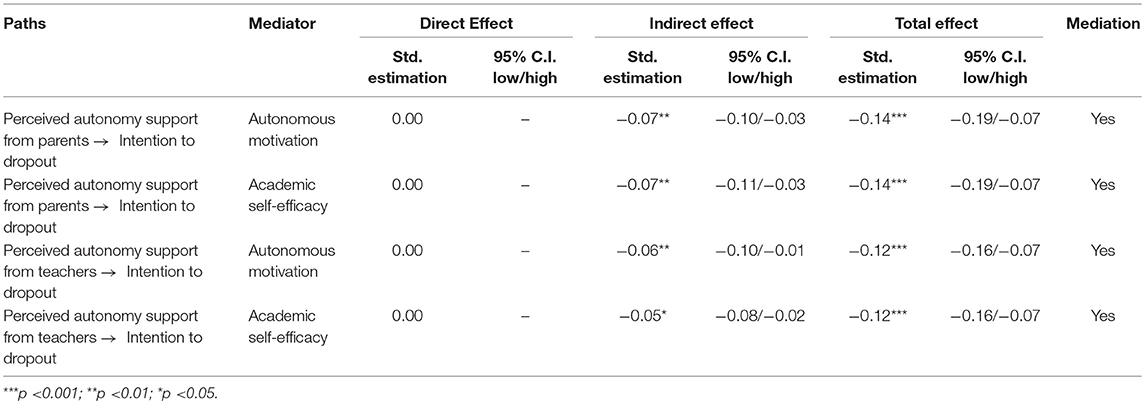

Standardized path coefficients for the free parameters in the path analyses are depicted in Figure 1. Standardized path coefficients for mediated effects are given in Table 4. Overall, the model indicated a very good fit with the data according to multiple criteria of model fit, after controlling for past performance and parental education level. Focusing on the hypothesized effects in the model, as expected, perceived autonomy support from both parents and teachers significantly predicted autonomous motivation and self-efficacy. In accordance with the hypothesis, both autonomous motivation and self-efficacy were significantly and negatively associated with intention to drop out. Furthermore, intention to drop out was a statistically significant and negative predictor of academic adjustment in the first semester, as hypothesized. Finally, in accordance with the hypothesis, all the tested bootstrapped indirect effects were statistically significant; therefore, both autonomous motivation and self-efficacy mediated the effects of perceived autonomy support from parents and from teachers on dropout intention. Findings are consistent with our hypothesis that there would be indirect effects of perceived autonomy support from parents and teachers on intention mediated by autonomous motivation and self-efficacy.

Figure 1. Standardized path coefficients for structural equation model of hypothesized relations among model constructs. RAI, Relative Autonomy Index; dashed lines indicate paths that were not statistically significant (p > 0.05) in the SEM analysis. Direct effects of past performance and parental education level on all variables in the model estimated but not depicted in diagram: past performance → perceived autonomy support (parents) (β = 0.068, p = 0.192); past performance → perceived autonomy support (teachers) (β = 0.056, p = 0.296); past performance → RAI (β = 0.072, p = 0.160); past performance → intention to dropout (β = 0.023, p = 0.652); parental education level → perceived autonomy support (parents) (β = 0.089, p = 0.086); parental education level → perceived autonomy support (teachers) (β = 0.011, p = 0.838); parental education level → RAI (β = −0.055, p = 0.284); parental education level → academic self-efficacy (β = −0.091, p = 0.056); parental education level → intention to dropout (β = −0.053, p = 0.297). ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

Table 4. Standardized path coefficients for mediated effects for the structural equation model for academic adjustment.

The main purpose of the present study was to test a predictive model of academic adjustment in first-year undergraduate students. The model was based on self-determination theory with the inclusion of self-efficacy. A prospective design was conducted with data obtained at two points in time: at the beginning of the academic year and at the end of the first semester. This design allowed us to investigate how motivational resources, self-efficacy beliefs, and the perception of students to be supported in their autonomy by teachers and parents could predict academic adjustment four months later, after controlling for past performance and parental education level, which are shown to be related to academic adjustment. Although previous research investigated the impact of autonomous motivation and self-efficacy on academic adjustment outcomes in the university context, any studies so far had considered the impact of a motivational model based on SDT, with the inclusion of self-efficacy, on academic adjustment. Our study is the first investigation that integrates SDT and self-efficacy into a unified model to explain early academic adjustment in first-year students.

Overall, the findings of the study provided good support for the model, therefore the hypothesized model is able to predict early academic adjustment in first-year university students. Specifically, findings supported all the hypothesized effects in the proposed model: (a) students who felt more supported in their autonomy by their parents and their teachers, developed more autonomous forms of motivation and greater academic self-efficacy; (b) students attending university for more autonomous reasons and having stronger beliefs in their own academic abilities, were less likely to develop dropout intention; (c) students with less intention to dropout were more likely to experience better academic adjustment; and (d) both autonomous motivation and academic self-efficacy mediated the effects of perceived autonomy support on intention to dropout.

Confirmation to the first hypothesis suggests that both sources of autonomy support can influence students' perceptions of self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation at university. This is consistent with an extant body of research indicating the influence of parents and teachers education's styles in supporting students' motivation and self-efficacy beliefs (Turner et al., 2009; Jang et al., 2016). Moreover, students attending university for more autonomous reasons and having stronger beliefs in their own academic abilities, were less likely to develop dropout intention; these results are aligned with previous studies showing significant relations between the immediate antecedents of behavior (intention) and autonomous forms of motivation and perceived competence in various domains (Hagger and Chatzisarantis, 2009, 2016). Such studies demonstrate that students are more likely to form future intentions to remain at university if their motives are self-determined and if they feel more confident in their own abilities. Finally, students with less intention to dropout at the start of the academic year, experience better academic adjustment at the end of the first semester. This is also consistent with previous findings indicating that students with low dropout intention might feel at the right place at university, and therefore they will show greater engagement in their studies (Respondek et al., 2017). A likely mechanism for this is that students with less intention to drop out will put major efforts into attaining as many credits as possible, in order to stay on track. The mediation hypothesis were also confirmed. In fact, the effects of perceived autonomy support from parents and teachers on intention to dropout were mediated by both autonomous motivation and academic self-efficacy. This suggests that students' perceptions that significant figures create an autonomy supporting environment for attending university is associated with their intention to enact that behavior (Girelli et al., 2016). This is consistent with previous research showing significant associations between perceived autonomy support from the environmental context and dropout intention (Fan and Williams, 2018).

The results of this study need to be interpreted in light of some limitations. First of all, we did not assess actual dropout but only self-reported intention to leave university and academic adjustment as an early-warning sign of dropout. Future research should consider testing this model on dropout behavior (Allen et al., 2008; Respondek et al., 2017). Second, we conducted this study in only one university including only students from the same department. The results may therefore not be generalizable to other students, even if in similar circumstances. Future research should thus reanalyze these interrelations with university students coming from different disciplines. Third, we did not measure socio-economic status, which is a variable that may have affected students persistence and academic achievement (Aina, 2013; Alivernini and Manganelli, 2015), but only parental education level. Future research should therefore consider including SES as a control variable. Despite those limitations, the present study is consistent with the idea that intrinsically motivated students and students with strong self-efficacy beliefs will be less likely to develop intention to drop out of university and will show higher degree of academic adjustment.

In order to fill a gap in the literature of SDT on undergraduate students, the present contribution aimed to test a model based on SDT, with the inclusion of self-efficacy. The study broadened prior research in SDT, who found that autonomous motivation predicted academic adjustment outcomes in university students (Turner et al., 2009; Gillet et al., 2017; Nowell, 2017). Congruent with SDT, students' increased autonomous motivation toward attending university led them to meet academic demands, as demonstrated by their greater academic adjustment. Further, in addition to autonomous motivation, students' increased beliefs in their own abilities to manage academic activities were associated with better academic adjustment outcomes. This is consistent with SDT who reported that academic competence beliefs predicted dropout from school in grade 7 students (Quiroga et al., 2013). Our findings also reinforce previous studies on the relevance of an autonomy supportive environment in fostering autonomous motivation and academic self-efficacy. Specifically, our results suggest that students who perceived greater support for autonomy by their teachers and their parents, showed higher level of autonomous motivation and perceived self-efficacy. This extends prior research in SDT who found that the perception of being supported by their significant figures enhances autonomous forms of motivation in university students (Turner et al., 2009; Jang et al., 2016). These results also extend previous studies in SCT adding the support for autonomy provided by the environment to the sources of academic self-efficacy.

According to our findings, in order to prevent first-year students from developing dropout intentions, and consequently leaving their course, interventions should aim to foster autonomous motivation and perceived self-efficacy. Our model suggests that this could be achieved by enhancing students' support in their autonomy by their teachers and their families. One possible application could be promoting training programs that encourage autonomy supportive behaviors in parents, as for example recognizing their children's feeling and perspective; providing choices and encouraging them; explaining the rationale behind requests (Turner et al., 2009; Pedersen et al., 2012). Alternative methods may also be implemented at the university level. Studies have identified several behaviors enacted by teachers in order to support students autonomy in the educational context, for example offering options about how to do an activity, providing explanatory rationales, especially when requesting to engage in uninteresting activities, taking the students' perspective, using a non-controlling language, allowing students to work at their own pace and teaching in students' preferred ways (Jang et al., 2016). Institutions could encourage these behaviors in teachers by developing training protocols. Cheon et al. (2012), for example, have developed a training program that provides explicit instructions and training materials to stimulate autonomy-supportive behaviors in teachers. Implementing actions and programs at university level is recommended to improve students' academic self-efficacy and motivation and, in turn, improve early academic adjustment.

One of the main contribution of the present study is that it extends research based on self-determination theory to the predictive effects of self-determined motivation and self-efficacy beliefs on academic adjustment outcomes by examining the number of credits attained at the end of the first semester as an early-warning sign of dropout. The role of autonomous motivation is particularly important for undergraduate students—as compared to high school students—as they are not obliged to pursue their studies and they can to a considerable extent choose which courses they take and with what faculty. Furthermore, self-efficacy with regard to mastering academic activities is central, especially among undergraduate students within the first year of university. Respondek et al. highlighted the challenges of this difficult transition: “Entry into university means greater academic demands, but also greater autonomy, less academic structure, increased pressure to excel, new social environments, and adaption to new roles or responsibilities” (Respondek et al., 2017, p. 3). These new demands can lead students to have less confidence in their capabilities (Perry, 2003). Another relevant result of this contribution is the importance of perceived autonomy support provided by parents and teachers in the social environment in which students are engaged. An extension of the present study would be to investigate the associations of perceived autonomy support from parents and teachers with other predictors for undergraduate students' academic adjustment, such as attitudes and perceived control (Hagger and Chatzisarantis, 2016; Respondek et al., 2017). Results of the current study underlined the predictive effect of self-efficacy beliefs on dropout intentions, in addition to autonomous forms of motivation, particularly within the first year. This suggests that students' perceptions of an autonomy-supportive environment created by parents and teachers are associated with students' motivation and competence beliefs with respect to academic activities. Moreover, students' motivation and beliefs in their own capabilities significantly predicted intention to drop out, which is considered the most proximal predictor of actual dropout (Bean, 1980; Respondek et al., 2017).

This study was exempt from an ethic committee approval due to the recommendations of the Italian Psychology Association: All participants were in no risk out of physical or emotional pressure, written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study and the results are disseminated only anonymously. None of the participants were patients, minors or persons with disabilities.

LG contributed conception and design of the study, performed the statistical analysis, drafted the work and contributed to all steps of the work. MC and GS revised the first draft of the manuscript. FA, FL, MS, and SS revised the paper, monitored all the process providing scientific, and theoretical contribution. All authors approve of the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Aina, C. (2013). Parental background and university dropout in Italy. High. Educ. 65, 437–456. doi: 10.1007/s10734-012-9554-z

Alivernini, F., and Lucidi, F. (2011). Relationship between social context, self-efficacy, motivation, academic achievement, and intention to drop out of high school: a longitudinal study. J. Educ. Res. 104, 241–252. doi: 10.1080/00220671003728062

Alivernini, F., Lucidi, F., and Manganelli, S. (2008). Assessment of academic motivation: a mixed methods study. Int. J. Mult. Res. Approach. 2, 71–82. doi: 10.5172/mra.455.2.1.71

Alivernini, F., and Manganelli, S. (2015). Country, school and students factors associated with extreme levels of science literacy across 25 countries. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 37, 1992–2012. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2015.1060648

Alivernini, F., Manganelli, S., Cavicchiolo, E., Girelli, L., Biasi, V., and Lucidi, F. (2017). Immigrant background and gender differences in primary students' motivations toward studying. J. Educ. Res. 111, 603–611. doi: 10.1080/00220671.2017.1349073

Alivernini, F., Manganelli, S., and Lucidi, F. (2016). The last shall be the first: competencies, equity and the power of resilience in the Italian school system. Learn. Individ. Differ. 51, 19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2016.08.010

Allen, J., Robbins, S. B., Casillas, A., and Oh, I.-S. (2008). Third-year college retention and transfer: effects of academic performance, motivation, and social connectedness. Res. High. Educ. 49, 647–664. doi: 10.1007/s11162-008-9098-3

Anvur (2016). Rapporto Biennale Sullo Stato del Sistema Universitario e Della Ricerca [Biennial Report on the State of the University System and Research]. Rome.

Bandura, A. (1990). Multidimensional Scales of Perceived Academic Efficacy. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University.

Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educ. Psychol. 28, 117–148. doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep2802_3

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co.

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., and Pastorelli, C. (1996). Multifaceted impact of self-efficacy beliefs on academic functioning. Child Dev. 67, 1206–1222.

Bean, J. P. (1980). Dropouts and turnover: the synthesis and test of a causal model of student attrition. Res. High. Educ. 12, 155–187. doi: 10.1007/BF00976194

Black, A. E., and Deci, E. L. (2000). The effects of instructors' autonomy support and students' autonomous motivation on learning organic chemistry: a self-determination theory perspective. Sci. Ed. 84, 740–756. doi: 10.1002/1098-237X(200011)84:6<740::AID-SCE4>3.0.CO;2-3

Cerasoli, C. P., Nicklin, J. M., and Ford, M. T. (2014). Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic incentives jointly predict performance: a 40-year meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 140, 980–1008. doi: 10.1037/a0035661

Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., and Moon, I. S. (2012). Experimentally based, longitudinally designed, teacher-focused intervention to help physical education teachers be more autonomy supportive toward their students. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 34, 365–396. doi: 10.1123/jsep.34.3.365

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: self-determination in personality. J. Res. Pers. 19:2. doi: 10.1016/0092-6566(85)90023-6

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2016). “Optimizing students' motivation in the era of testing and pressure: a Self-determination theory perspective,” in Building Autonomous Learners: Perspectives From Research and Practice Using self-Determination theory, eds W. C. Liu, J. C. K. Wang, and R. M. Ryan (Singapore: Springer), 9–29.

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., and Guay, F. (2013). “Self-determination theory and actualization of human potential,” in Theory Driving Research: New Wave Perspectives on Self Processes and Human Development, eds D. McInerney, H. Marsh, R. Craven, and F. Guay (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Press), 109–133.

Fan, W., and Williams, C. (2018). The mediating role of student motivation in the linking of perceived school climate and achievement in reading and mathematics. Front. Educ. 3:50. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00050

Galli, F., Chirico, A., Mallia, L., Girelli, L., De Laurentiis, M., Lucidi, F., et al. (2018). Active lifestyles in older adults: an integrated predictive model of physical activity and exercise. Oncotarget 9, 25402–25413. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25352

Gillet, N., Berjot, S., Vallerand, R. J., and Amoura, S. (2012). The role of autonomy support and motivation in the prediction of interest and dropout intentions in sport and education settings. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 34, 278–286. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2012.674754

Gillet, N., Morin, A. J. S., and Reeve, J. (2017). Stability, change, and implications of students' motivation profiles: a latent transition analysis. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 51, 222–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.08.006

Girelli, L., Hagger, M., Mallia, L., and Lucidi, F. (2016). From perceived autonomy support to intentional behaviour: testing an integrated model in three healthy-eating behaviours. Appetite 96, 280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.09.027

Grolnick, W. S., and Ryan, R. M. (1987). Autonomy in children's learning: an experimental and individual difference investigation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 52, 890–898. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.52.5.890

Grolnick, W. S., and Ryan, R. M. (1989). Parent styles associated with children's self-regulation and competence in school. J. Educ. Psychol. 81, 890–898. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.81.2.143

Guay, F., Lessard, V., and Dubois, P. (2016). “How can we create better learning contexts for children? Promoting students' autonomous motivation as a way to foster enhanced educational outcomes,” in Building Autonomous Learners: Perspectives from research and practice Using Self-Determination Theory, eds W. C. Liu., J. C. K. Wang, and R. M. Ryan (Singapore:Springer), 83–106.

Hagger, M. S., and Chatzisarantis, N. L. (2009). Integrating the theory of planned behaviour and self-determination theory in health behaviour: a meta-analysis. Br. J. Health Psychol. 14, 275–302. doi: 10.1348/135910708X373959

Hagger, M. S., and Chatzisarantis, N. L. (2016). The trans-contextual model of autonomous motivation in education: conceptual and empirical issues and meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 86, 360–407. doi: 10.3102/0034654315585005

Hagger, M. S., Chatzisarantis, N. L., and Harris, J. (2006). From psychological need satisfaction to intentional behavior: testing a motivational sequence in two behavioral contexts. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 32, 131–148. doi: 10.1177/0146167205279905

Hagger, M. S., Chatzisarantis, N. L. D., Hein, V., Pihu, M., Soós, I., and Karsai, I. (2007). The perceived autonomy support scale for exercise settings (PASSES): Development, validity, and cross-cultural invariance in young people. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 8, 632–653. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2006.09.001

Hagger, M. S., Sultan, S., Hardcastle, S. J., and Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2015). Perceived autonomy support and autonomous motivation toward mathematics activities in educational and out-of-school contexts is related to mathematics homework behavior and attainment. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 41, 111–123. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.12.002

Hardre, P. L., and Reeve, J. (2003). A motivational model of rural students' intentions to persist in, versus drop out of, high school. J. Educ. Psychol. 95, 347–356. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.95.2.347

Hu, L.-T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Jang, H., Reeve, J., and Halusic, M. (2016). A new autonomy-supportive way of teaching that increases conceptual learning: teaching in students' preferred ways. J. Exp. Educ. 84, 686–701. doi: 10.1080/00220973.2015.1083522

Litalien, D., and Guay, F. (2015). Dropout intentions in PhD studies: a comprehensive model based on interpersonal relationships and motivational resources. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 41, 218–231. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.03.004

McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test Theory: A Unified Treatment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Nowell, C. (2017). The influence of motivational orientation on the satisfaction of university students. Teach. High. Educ. 22, 855–866. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2017.1319811

Overall, N. C., Deane, K. L., and Peterson, E. R. (2011). Promoting doctoral students' research self-efficacy: combining academic guidance with autonomy support. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 30, 791–805. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2010.535508

Pedersen, D. E. (2017). Parental autonomy support and college student academic outcomes. J. Child Fam. Stud. 26, 2589–2601. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0750-4

Pedersen, T., Kristensson, P., and Friman, M. (2012). Counteracting the focusing illusion: Effects of defocusing on car users' predicted satisfaction with public transport. J. Environ. Psychol. 32, 30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2011.10.004

Perry, R. P. (2003). Perceived (academic) control and causal thinking in achievement settings. Can. Psychol. 44, 312–331. doi: 10.1037/h0086956

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Quiroga, C. V., Janosz, M., Bisset, S., and Morin, A. J. S. (2013). Early adolescent depression symptoms and school dropout: mediating processes involving self-reported academic competence and achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 105, 552–560. doi: 10.1037/a0031524

R Core Tem (2017). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Ratelle, C. F., Guay, F., Vallerand, R. J., Larose, S., and Senécal, C. (2007). Autonomous, controlled, and amotivated types of academic motivation: a person-oriented analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 734–746. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.734

Raykov, T. (1997). Estimation of composite reliability for congeneric measures. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 21, 173–184. doi: 10.1177/01466216970212006

Respondek, L., Seufert, T., Stupnisky, R., and Nett, U. E. (2017). Perceived academic control and academic emotions predict undergraduate university student success: examining effects on dropout intention and achievement. Front. Psychol. 8:243. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00243

Richardson, M., Abraham, C., and Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students' academic performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 138, 353–387. doi: 10.1037/a0026838

Ryan, R. M., and Connell, J. P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: examining reasons for acting in two domains. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57, 749–761

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2009). “Promoting self-determined school engagement: motivation, learning and well-being,” in Handbook of Motivation at School, eds K. R. Wentzel and A. Wigfield (New York, NY: Routledge), 171–195.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Ryan, R. M., and Grolnick, W. S. (1986). Origins and pawns in the classroom: self- report and projective assessments of individual differences in children's perceptions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 50, 550–558. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.50.3.550

Souto-Inglesias, A., and Baeza_Romero, M. T. (2018). A probabilistic approach to student workload: empirical distributions and ECTS. High. Educ. doi: 10.1007/s10734-018-0244-3. [Epub ahead of print].

Stinebrickner, R., and Stinebrickner, T. (2014). Academic performance and college dropout: using longitudinal expectations data to estimate a learning model. J. Labor Econ. 32, 601–644. doi: 10.1086/675308

Tabachnick, B. G., and Fidell, L. S. (2006). Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th Edn. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon, Inc.

Turner, E. A., Chandler, M., and Heffer, R. W. (2009). The Influence of parenting styles, achievement motivation, and self-efficacy on academic performance in college students. J. College Stud. Dev. 337–346. doi: 10.1353/csd.0.0073

Usher, E. L., and Pajares, F. (2008). Sources of self-efficacy in school: critical review of the literature and future directions. Rev. Educ. Res. 78, 751–796. doi: 10.3102/0034654308321456

Vallerand, R. J., and Ratelle, C. F. (2002). “Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: a hierarchical model.,” in Handbook of Self-determination Research (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press), 37–63.

Vanthournout, G., Gijbels, D., Coertjens, L., Donche, V., and Van Petegem, P. (2012). Students' persistence and academic success in a first-year professional bachelor program: the influence of students' learning strategies and academic motivation. Educ. Res. Int. 2012, 1–10. doi: 10.1155/2012/152747

Vossensteyn, H., Kottmann, A., Jongbloed, B., Kaiser, F., Cremonini, L., Stensaker, B., et al. (2015). Drop-out and Completion in Higher Education in Europe-Main Report, European Union.

Williams, G. C., and Deci, E. L. (1996). Internalization of biopsychosocial values by medical students: a test of self-determination theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70, 767–779.

Keywords: university dropout, autonomy-support, self-determination theory, academic adjustment, freshman, higher education, past performance

Citation: Girelli L, Alivernini F, Lucidi F, Cozzolino M, Savarese G, Sibilio M and Salvatore S (2018) Autonomy Supportive Contexts, Autonomous Motivation, and Self-Efficacy Predict Academic Adjustment of First-Year University Students. Front. Educ. 3:95. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00095

Received: 30 July 2018; Accepted: 18 October 2018;

Published: 05 November 2018.

Edited by:

Claudio Longobardi, Università Degli Studi di Torino, ItalyReviewed by:

Jesús Nicasio García Sánchez, Universidad de León, SpainCopyright © 2018 Girelli, Alivernini, Lucidi, Cozzolino, Savarese, Sibilio and Salvatore. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laura Girelli, bGdpcmVsbGlAdW5pc2EuaXQ=; bGF1cmEuZ2lyZWxsaUB1bmlyb21hMS5pdA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.