94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 12 November 2018

Sec. Leadership in Education

Volume 3 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00094

This article is part of the Research TopicMinority Serving Institutions: Free Speech and Student Protest in the Era of TrumpView all 5 articles

This manuscript considers the political attitudes of Black students at Historically Black Colleges and Universities using a 2015 sample of first-year respondents. In response to this special issue's call to consider issues of student protest at Minority Serving Institutions, our manuscript offers empirical evidence on students' political dispositions at Historically Black Colleges and Universities. Indeed, understanding the civic dispositions and political ideologies of Black students at Historically Black Colleges and Universities is not only a timely topic, but also a necessary one if we are to understand the future political engagement of an increasingly diverse nation (Lefever, 2005; Williamson, 2008).

Historically Black Colleges and Universities have garnered substantial attention during Trump's presidency given the ambivalent relationship between HBCU leaders and the White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities (C-SPAN, 2018). HBCUs continue to operate under an increasingly hostile environment for students of color in the current presidency; most recently, the forty-fifth president of the United States has gone as far as de-humanizing immigrants by calling them “animals” (Castro Samayoa and Nicolazzo, 2017; Qiu, 2018). In the context of these precarious political moments, scholarship must also attend to the attitudes that students bring to their social consciousness and dispositions toward activism.

This manuscript considers the political attitudes of Black students at Historically Black Colleges and Universities using a 2015 sample of first-year respondents. Following this special issue's call to consider issues of student protest at Minority Serving Institutions, our manuscript offers empirical evidence on students' political dispositions at Historically Black Colleges and Universities. Indeed, understanding the civic dispositions and political ideologies of Black students at Historically Black Colleges and Universities is not only a timely topic, but also a necessary one if we are to understand the future political engagement of an increasingly diverse nation (Lefever, 2005; Williamson, 2008).

Our descriptive study is guided by the following research question: How do Black1 first-year students at Historically Black Colleges and Universities compare with Black students at non-HBCUs in their social agency? In the section below, we clarify the data sources that have guided our study and also describe how the questionnaire administered in our national dataset can be used to construct and operationalize a measurement for social agency. Following our description of results, we offer a discussion on the significance of these data for future avenues of research.

Our study is conceptualized by past scholarship framing Historically Black Colleges and Universities as incubators of social change (Gasman, 2005; Gasman and Tudico, 2008). The robust scholarship on students' experiences at HBCUs has previously discussed how they cultivate distinct forms of social capital (Palmer and Gasman, 2008), racial identities (Rucker and Gendrin, 2003), and student engagement in activism (Rosenthal, 1975; Franklin, 2003). Importantly, the scholarship on students' activism within HBCUs has engaged with the question from historical perspectives. In contrast, recent scholarship on Black students' social activism on college campuses has largely focused on their experiences within predominantly white institutions (Cohen and Synder, 2013; Jones and Reddick, 2017; Leath and Chavous, 2017). Indeed, some of these recent works have traced the contours of change in Black and Brown millenials' activism in response to the political shifts borne from Trump's inflammatory political rhetoric (Logan et al., 2017).

Further, scant attention has been paid to the pre-college dispositions that students bring to these campuses with respect to their attitudes around social issues, including political activism. Thus, even though past scholarship on HBCUs has robustly detailed how these institutions cultivate institutional contexts that can nourish students' sense of racial belonging, awareness, and activism, there is more to explore with respect to the profile of those students who choose to enroll within these institutions. In this context, our study seeks to offer a snapshot further contextualizing students' experiences by exploring how their dispositions may already differ prior to enrolling within an HBCU, with a particular emphasis on their social agency. As we document below, however, we do not believe that the data in this preliminary study are comprehensive of students' heterogeneity within HBCUs. In effect, our intent is to illustrate the future avenues that scholars of HBCUs and practitioners within these institutional contexts may choose to explore within a political moment of increasing racial hostility in this country (Qiu, 2018).

This manuscript uses data from the 2015 Freshman Survey (TFS) administered by the Higher Education Research Institute (HERI) at the University of California–Los Angeles (UCLA). TFS is part of the Cooperative Institutional Research Program (CIRP), a national longitudinal study of U.S. higher education dating back to its founding in 1966 by Alexander Astin at the American Council on Education. TFS is one of the surveys administered by HERI, specifically targeted for first-year students who respond to the survey prior to the start of their first term in college. TFS data, weighted to reflect the total population of first-time, full-time first-year students, is consistently used as a representative sample of students' attitudes, widely recognized through HERI's publication of annual national norm reports.

The 2015 TFS questionnaire consisted of 51 items documenting students' pre-college characteristics (e.g., sex, age, year of high school graduation, higher education institution's distance from their primary residence, advance placement courses), attitudes regarding social issues (e.g. level of agreement with statements like “racial discrimination is no longer a major problem in America”; “Abortion should be legal.”) and behaviors (e.g., hours per week spent studying, socializing with friends). Of note, the data that we have used for this manuscript does not trace the changes in students' social agency before or after Trump's presidency. This is, in effect, an important consideration for future iterations of this work; rather, our goal in this paper is to demonstrate the potential utility of these data to develop an institutional consciousness on students' dispositions toward social agency and activism.

Of interest for this manuscript, a total of 311 institutions participated in the survey, with 18 of these institutions categorized as Historically Black Colleges. In total, these institutions accounted for 5.7% of the total institutional sample. Historically, HBCUs have accounted for 3.7% of all institutions who have ever participated in the survey, with multiple HBCUs participating in samples as early as the first TFS, administered in 1966. As we note later, given the modest representation of HBCUs within institutions represented in TFS, the claims we make in this manuscript are not generalizable to HBCUs. Notwithstanding these limitations on generalizability, we also underscore that TFS is the only survey that enables researchers to articulate the potential discussion of political dispositions by its first-year students.

The social agency construct measures the extent to which students value political and social involvement as personal goals. It includes the following six survey items:

• Goal of keeping up to date with political affairs

• Goal of participating in a community action program

• Goal of influencing social values

• Goal of becoming a community leader;

• Goal of helping others who are in difficulty

• Goal of helping to promote racial understanding

Each of the items is measured on a four-point scale which asks students to indicate the importance to them personally of each of the goals. Response options include: 1 = Not Important, 2 = Somewhat Important, 3 = Very Important, and 4 = Essential.

The civic engagement construct measures the extent to which students are motivated and involved in civic, electoral, and political activities. It includes the following eight survey items:

• Demonstrated for a cause (e.g., boycott, rally, protest)

• Performed volunteer work

• Worked on a local, state, or national political campaign

• Helped raise money for a cause or campaign

• Publicly communicated your opinion about a cause (e.g., blog, email, petition)

• Goal of influencing social values

• Goal of keeping up to date with political affairs

The first five items measure the frequency with which students participated in a series of activities. Response options on this three-point scale include: 1 = Not at All, 2 = Occasionally, and 3 = Frequently. The final two items ask students to indicate the importance to them personally of each of the goals. Response options include: 1 = Not Important, 2 = Somewhat Important, 3 = Very Important, and 4 = Essential.

Our data come from a subset of the 2015 Freshman Survey consisting of Black respondents at Historically Black Colleges (n = 6,779) and compares these responses to those of Black respondents from non-HBCUs (n = 9,778).

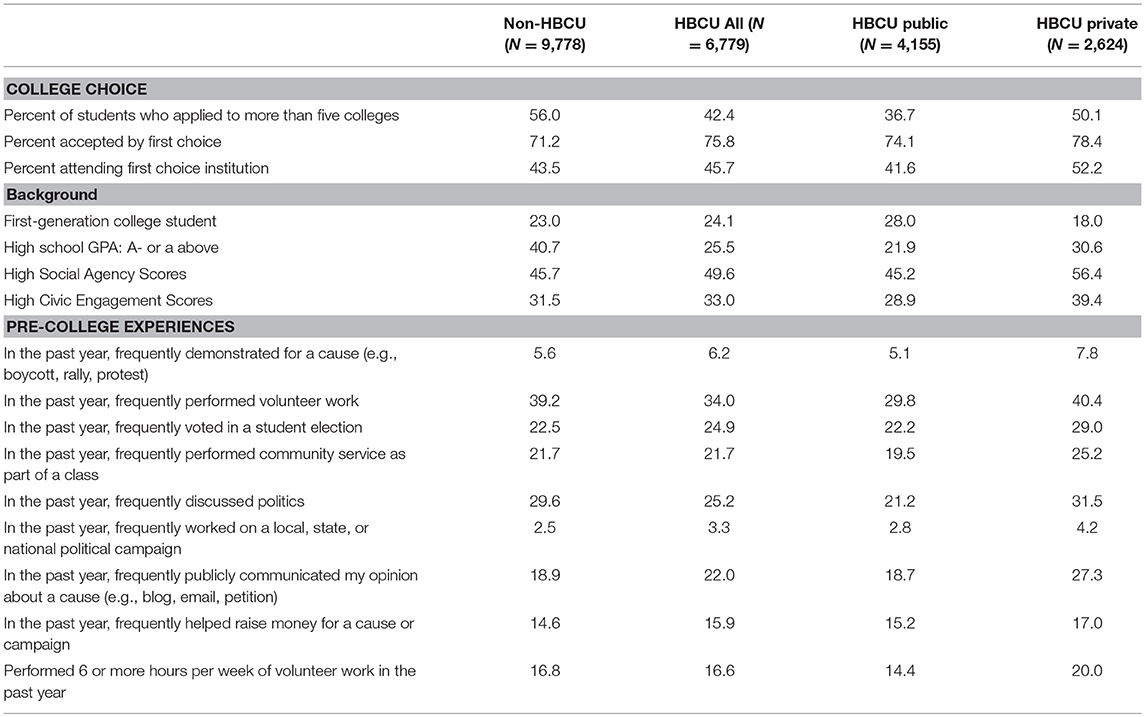

First-time, full-time, African American students at HBCUs reported higher levels of social agency and civic engagement than African American students at non-HBCUs. With 49.6 percent of respondents who attend HBCUs scoring in the highest level of social agency scores compared to 45.7 percent of their non-HBCU peers. The data reveal a similar trend for civic engagement with 33.0 percent of African American students at HBCUs scoring in the highest level on the civic engagement construct as compared with 31.5 percent of their non-HBCU peers. A summary of these findings can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Incoming first-year African American student's background characteristics and pre-college experiences.

Among African American students at HBCUs, students at private HBCUs scored higher on the social agency and civic engagement constructs. More than half (56.4 percent) of African American students at private HBCUs, scored in the top of the social agency construct as compared to 45.2 percent of African American students at public HBCUs, an 11.2 percentage point difference. There is a 10.5 percentage point difference in the number of African American students who scored in the highest levels of civic engagement with 39.4 percent of students at private HBCUs scoring in the highest level as compared to 28.9 percent of students at public HBCUs, where a high score consists of at least half a standard deviation above the mean for the total population.

African American students at non-HBCUs report more frequently performing volunteer work (39.2 percent) compared to their peers at HBCUs (34.0 percent). However, African American students at private HBCUs report more frequently performing volunteer work (40.4 percent) than their public HBCU peers (29.8 percent).

A larger portion of African American students at HBCUs report frequently publicly communicating their opinions about a cause−22 percent of African Americans at HBCUs vs. 18.9 percent of African Americans at non-HBCUs. Among African American students at private HBCUs, 27.3 percent report frequently communicating their opinions publicly compared to 18.7 percent at public HBCUs.

Notably, a larger percent of African American students at non-HBCUs reported frequently discussing politics (29.6 percent compared to 25.2 percent of African American students at HBCUs). Among African American students at HBCUs there is a 10.3 percentage point difference between private HBCU students who reported frequently discussing politics (31.5 percent) compared to their peers at public HBCUs (21.2 percent).

There are also differences between the distances from home that students attend college. Overall, a larger percentage of African American students at HBCUs attend college farther from home compared to their non-HBCU peers (32.0 percent attend college at least 101 miles from home as compared to 27.5 of non-HBCU students).

Further, among African American students at HBCUs, students at private HBCUs attend college further from home with 67.1 percent of students at private HBCUs attending school at least 101 miles from home compared with 47.9 students at public HBCUs.

There are also income differences between African American students at HBCUs and non-HBCUs. Twenty-two percent of African American students at HBCUs come from families who make $75,000 or more as compared with 30.6 percent of their peers at non-HBCUs.

Among students at HBCUs, 29 percent of African American students at private HBCUs came from families who make more than $75,000 per year as compared to 17.4 percent of their peers at public HBCUs.

The descriptive data suggest a political landscape at Historically Black Colleges that is more politically engaged than its non-HBCU counterparts. For example, 1 in 5 (20.3%) Black HBCU respondents claim there is a very good chance that they will participate in protests or demonstrations compared to 15.6% of their peers at non-HBCUs. Interestingly, the landscape within HBCUs shifts again when disaggregated by institutional control. At public HBCUs, 16.8% of Black respondents affirm this claim, whereas 1 in 4 Black students at private HBCUs (25.7%) believe there is a very good chance they will engage in protests.

We also make note of the variance in political leanings at HBCUs. For Black respondents at private HBCUs, 14.8% claim they are far right or conservative compared to 19.5% of their peers at public HBCUs. However, only 10.4% of Black respondents at non-HBCUs affiliate with far right or conservative ideologies.

Though the findings of this manuscript are limited to the subset of HBCUs participating in this national survey (17.8% of all HBCUs), we underscore the importance of enhancing campus administrators' knowledge of students' political dispositions and attitudes toward protesting. Overall, the data suggest that there are consistent findings with prior research investigating social conservatism at HBCUS (Harper and Gasman, 2008).

As a descriptive study, this manuscript outlined the opportunities for future research to undertake a more robust and critical examination of how Black students within HBCUs have distinct predispositions toward their social agency and engagement. Given that such few studies have considered the contemporary importance of HBCU students' social agency, the preliminary overview that we share in this manuscript is intended to offer suggestions on how other scholars may wish to conceptualize opportunities to better understand Black students' political dispositions within HBCUs. Furthermore, given that the survey results from TFS are available to campus officials within each participating institution, we encourage those HBCUs who consider partaking or have previously partaken in this national survey to consider disaggregating their data with an attention to the social agency and civic engagement constructs.

Future research may also wish to explore potential trends emerging from these data across multiple years, particularly for those who are interested in mapping the emerging trends from the shifting social zeitgeist on racial attitudes in the United States. Indeed, we recognize the value of offering insights that document the shifts in the attitudes of students during moments of particular political shifts as the ones experienced in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election.

Limitations of this work also suggest that beyond the descriptive nature of different student profiles between HBCUs and non-HBCUs, we should caution against claims that homogenize students' experiences within HBCUs. As others have noted, the multiple experiences of students at HBCUs need to be underscored (Williams, 2018). We suggest, further, that other scholars consider deep-dive case studies exploring student activism within these institutional types. The descriptive data that we have shared in this piece can serve as valuable points of departure detailing the possibilities of how students with particular dispositions toward social activism may anticipate finding a sense of belonging within HBCUs. Said differently: with the knowledge that students may have specific political dispositions within one's campus, institutional leaders have important data to consider how they cultivate spaces wherein students can further develop their social agency. Specifically, the constructs we have used to describe a landscape of Black students' civic dispositions focus on whether students spend their time invested in political campaigns through volunteering or fundraising, whether they publicly communicate their opinions, and whether they attend rallies and exercise their duties to vote. Institutions that intentionally cultivate opportunities for students to engage across these types of activities can be most effective when they understand the types of predispositions with which they arrive to their campuses. We further note, however, that future studies need to remain attentive to the potential intersection of students' identities. The landscape we describe through the results of this national survey suggest there are difference between students who attend public or private HBCUs or who choose to enroll at other institutions. Thus, rather than suggesting a uniform approach to students' political agency and civic engagement, our findings offer a timely reminder for both researchers and institutional practitioners alike to remain attuned to the needs that students articulate within their own institutional context. Asking questions to better understand students' interests and dispositions, as evidenced by their responses in this national survey, suggests that we have much to learn from our students.

As a whole, this work also suggests that HBCUs stand to benefit from a collective investment in participating in TFS to better understand their students' dispositions toward collective action and activism. Furthermore, the most recent activism (by scholars, administrators, and students) within HBCUs in the face of an increasingly hostile political environment (Williams, 2018) demonstrates the continued importance of HBCUs as clarion calls to advance more equitable opportunities within higher education. Our data suggest we need more research to understand the political attitudes within student environments at HBCUs.

Note that we use Black and African-American interchangeably for the purposes of this manuscript. For a thorough description on the conceptual distinctions of these terms, see Berlin (2010).

AC contributed to the conception of Research Question (RQ), introduction, literature review, and findings. HBZ and EBS contributed to the conception of the RQ, data collection, and analysis. MG contributed to the conception of RQ implications and conclusion.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Berlin, I. (2010). The Changing Definition of African-American. Smithsonian Magazine. Available online at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-changing-definition-of-african-american-4905887/

Castro Samayoa, A., and Nicolazzo, Z. (2017). Affect and/as collective resistance in a post-truth moment. Int. J. Qualitative Studies Educ. 30, 988–9993. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2017.1312595

Cohen, R., and Synder, D. (2013). Rebellion in Black and White: Southern Student Activism in the 1960s. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

C-SPAN (2018, February 27). President Trump on White House HBCU Initiative. Available online at: https://www.c-span.org/video/?441808-1/president-trump-remarks-white-house-hbcu-initiative.

Franklin, V. P. (2003). Patterns of student activism at historically Black universities in the United States and South Africa, 1960-1977. J. Afr. Am. Hist. 88, 204–217. doi: 10.2307/3559066

Gasman, M. (2005). Coffee table to classroom: a review of recent scholarship on historically Black colleges and universities. Educ. Res. 34, 32–39. doi: 10.3102/0013189X034007032

Gasman, M., and Tudico, C. (2008). Historically Black Colleges and Universities: Triumphs, Troubles, and Taboos. New York, NY: Palgrave.

Harper, S., and Gasman, M. (2008). Consequences of conservatism: Black male students and the politics of Historically Black colleges and universities. J. Negr. Educ. 77, 336–351. Available online at: https://www-jstor-org.proxy.bc.edu/stable/25608703

Jones, V., and Reddick, R. (2017). The heterogeneity of resistance: How Black students utilize engagement and activism to challenge PWI inequalities. J. Negr. Educ. 86, 2204–2219. doi: 10.7709/jnegroeducation.86.3.0204

Leath, S., and Chavous, T. (2017). “We really protested”: the influence of sociopolitical believes, political self-efficacy, and campus racial climate on civic engagement among Black college students attending predominantly White institutions. J. Negr. Educ. 86, 220–237. doi: 10.7709/jnegroeducation.86.3.0220

Lefever, H. (2005). Undaunted by the Fight: Spelman College and the Civil Rights Movement, 1957-1957. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

Logan, G., Lightfoot, B., and Contreras, A. (2017). Black and Brown millennial activism on a PWI campus in the era of Trump. J. Negr. Educ. 86, 252–268. doi: 10.7709/jnegroeducation.86.3.0252

Palmer, R., and Gasman, M. (2008). “It takes a village to raise a child”: The role of social capital in promoting academic success for African American men at a Black college. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 49, 52–70. doi: 10.1353/csd.2008.0002

Qiu, L. (2018, May 18). The Context Behind Trump's ‘Animal’ Comment. The New York Times. Available online at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/18/us/politics/fact-check-trump-animals-immigration-ms13-sanctuary-cities.html.

Rosenthal, J. (1975). Southern Black student activism: assimilation vs. nationalism. J. Negr. Educ. 44, 113–129.

Rucker, M. L., and Gendrin, D. M. (2003). The impact of ethnic identification on student learning in the HBCU classroom. J. Instruct. Psychol. 30, 207–215.

Williams, M. (2018). Tell Them We Are Rising: The Story of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (Documentary): Broadcast, PBS, Feb, 2018. Co-Director/Co-Producer.

Keywords: HBCU, student protest, first-year, the freshman survey, social agency

Citation: Castro Samayoa A, Stolzenberg EB, Zimmerman HB and Gasman M (2018) Understanding Black Students' Social Agency at Historically Black Colleges: Data From a National Survey. Front. Educ. 3:94. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00094

Received: 02 June 2018; Accepted: 16 October 2018;

Published: 12 November 2018.

Edited by:

Whitney Sherman Newcomb, Virginia Commonwealth University, United StatesReviewed by:

Irene H. Yoon, University of Utah, United StatesCopyright © 2018 Castro Samayoa, Stolzenberg, Zimmerman and Gasman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrés Castro Samayoa, YW5kcmVzLmNhc3Ryb3NhbWF5b2FAYmMuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.