- 1Department of Higher Education, University of Surrey, Guildford, United Kingdom

- 2Southampton Education School, University of Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom

- 3Learning and Teaching Enhancement Centre, Directorate for Student Achievement, Kingston University, Kingston upon Thames, United Kingdom

If little care is taken when establishing clear assessment requirements, there is the potential for spoon-feeding. However, in this conceptual article we argue that transparency in assessment is essential to providing equality of opportunity and promoting students’ self-regulatory capacity. We begin by showing how a research-informed inclusive pedagogy, the EAT Framework, can be used to improve assessment practices to ensure that the purposes, processes, and requirements of assessment are clear and explicit to students. The EAT Framework foregrounds how students' and teachers' conceptions of learning (i.e., whether one has a transactional or transformative conception of learning within a specific context) impact assessment practices. In this article, we highlight the importance of being explicit in promoting access to learning, and in referencing the EAT Framework, the importance of developing transformative rather than transactional approaches to being explicit. Firstly, we discuss how transparency in the assessment process could lead to “criteria compliance” (Torrance, 2007, p. 282) and learner instrumentalism if a transactional approach to transparency, involving high external regulation, is used. Importantly, we highlight how explicit assessment criteria can hinder learner autonomy if paired with an overreliance on criteria-focused ‘coaching’ from teachers. We then address how ‘being explicit with assessment’ does not constitute spoon-feeding when used to promote understanding of assessment practices, and the application of deeper approaches to learning as an integral component of an inclusive learning environment. We then provide evidence on how explicit assessment criteria allow students to self-assess as part of self-regulation, noting that explicit criteria may be more effective when drawing on a transformative approach to transparency, which acknowledges the importance of transparent and mutual student-teacher communications about assessment requirements. We conclude by providing recommendations to teachers and students about how explicit assessment criteria can be used to improve students' learning. Through an emphasis on transparency of process, clarity of roles, and explication of what constitutes quality within a specific discipline, underpinned by a transformative approach, students and teachers should be better equipped to self-manage their own learning and teaching.

Introduction

A fundamental goal of higher education has to be to support learners to manage their own learning for themselves both in the present, and in the future as part of sustainable learning practices (Boud, 2000; Boud and Soler, 2016); all aspects of the assessment process should support this (Evans, 2016). In order to increase the effectiveness of assessment in higher education, it has been proposed that assessment should be a learning opportunity that directs students' focus toward what should be learned and engages them in the learning process (Boud and Associates, 2010). Explicit introduction, induction, and appropriate on-going support for the contextual requirements and purposes of learning activities within higher education are therefore important in supporting students' self-regulatory development (Waring and Evans, 2015). However, while students can (arguably) escape from the effects of poor teaching practice, they cannot escape the effects of poorly designed assessment (Boud, 1995a). Assessment practices need to keep pace with twenty-first century learning requirements, and at the same time, be cognizant of the differing contexts, expectations, and needs of our increasingly diverse student body (Balloo, 2017; Balloo et al., 2017).

If little care is taken when establishing clear assessment requirements, there is the potential for “spoon-feeding,” yet the move toward transparency in assessment in higher education has largely been positively received (Carless, 2015), since explicit requirements are likely to facilitate fairness in marking practices by enhancing markers' abilities to be consistent in making accurate judgments of student work (Broadbent et al., 2018) and communicating reasons for a particular judgment (Sadler, 2005). Explicit assessment criteria can support students to consider what they are aiming for and how this can be achieved from the perspective of a marker (Nicol and MacFarlane-Dick, 2006), so their learning outcomes move beyond a purely cognitive product, to the development of metacognition (Frederiksen and Collins, 1989; Shephard, 2000; Swaffield, 2011) and assessment literacy (Price et al., 2012). In this article, we present a conceptual analysis of the value of explicit assessment criteria; we highlight the potential risk of spoon-feeding in promoting “criteria compliance” (Torrance, 2007, p. 282), and then we present approaches demonstrating that a careful use of transparency through explicit assessment criteria is crucial to promoting equality of opportunity and students' self-regulation.

Notions of “Explicit” Within Higher Education Assessment Practices

In exploring notions of “explicit” within higher education assessment practices, it is important to consider how students' and teachers' different conceptions of learning (Entwistle and Peterson, 2004) impact on how we enact notions of “explicit” in practice. Notions of being explicit have been covered extensively in the literature, and making assessment processes transparent has a strong history with significant work being undertaken by the Assessment Reform Group (Broadfoot et al., 1999), and notably by Black and Wiliam (1998) in their seminal work on assessment for learning. Hattie's “visible learning approach” (Hattie, 2012; Hattie and Yates, 2014) also emphasizes the importance of assessment being explicit. The key issue, however, remains on how being explicit is interpreted and this is where conceptions of learning are central in drawing on our epistemological and ontological assumptions about learning, and our own responsibility in the assessment learning process.

The term “explicit” is a loaded term in relation to how clear information is, and to whom, from an inclusive and critical pedagogy perspective (Waring and Evans, 2015). What is explicit in one context may not be in another; the same student may struggle to grasp meanings from one module to another, timing (in relation to the accumulation of experience and expertise) impacts understandings, and cultural differences implicit in environments and through individual differences impact student and teacher1 understandings of the learning and teaching context. In addressing student access to learning, a number of key themes emerge from the literature to include the nature and role of scaffolding to support learner understandings, and how this is extended to discussions concerning the accessibility of information, and pedagogical lessons that can be learned from this.

Transparency, clarity, and explicit instruction in assessment have critical roles to play in addressing the long standing and assiduous differentials in student learning outcomes across various student groups. In particular, we argue that assessments that are loosely constructed and lack clarity have the potential to disproportionately disadvantage certain groups of students, and notably, those who have often been referred to as “non-traditional,” including those who are first generation in higher education, mature learners, students from Black and Minority Ethnic (BME)2 backgrounds, and those from lower socio-economic personal histories (Newbold et al., 2010). Differential attainment based on socio-economic background and various demographic characteristics is a long standing concern in higher education internationally (HEFCE, 2015; Cahalan et al., 2017; ECU, 2017). Existing research has told us that many students from “non-traditional” backgrounds feel relatively unprepared for the university experience and lack the sense of entitlement held by their white, middle class counterparts (Thomas and Quinn, 2007; Reay et al., 2010). These students are often less conversant with academic language, cultures and traditions, and they lack the confidence to question and challenge normative assessment practices (Southall et al., 2016; Witkowsky et al., 2016). With increasing numbers of students engaging in higher education globally, and from increasingly diverse backgrounds, higher education has a significant responsibility to ensure all students have equal access to learning environments. As identified in the “Feedback Landscape” (Evans, 2013), a conceptual framework exploring the learning process and individual development from both student and lecturer perspectives through an assessment lens, there are a myriad of individual difference variables impacting a student's learning. The design of the learning environment may inadvertently advantage some students over others; in understanding the principles of universal design (initiated by Ron Mace at the North Carolina State University College of Design, USA, and initially applied to architecture and then more widely to inclusive pedagogies, Rogers-Shaw et al., 2017), it is important to provide adaptive (i.e., all learners can access the learning environment) rather than adapted (i.e., learning environments designed to suit a specific type of learner) learning environments (Choi et al., 2009).

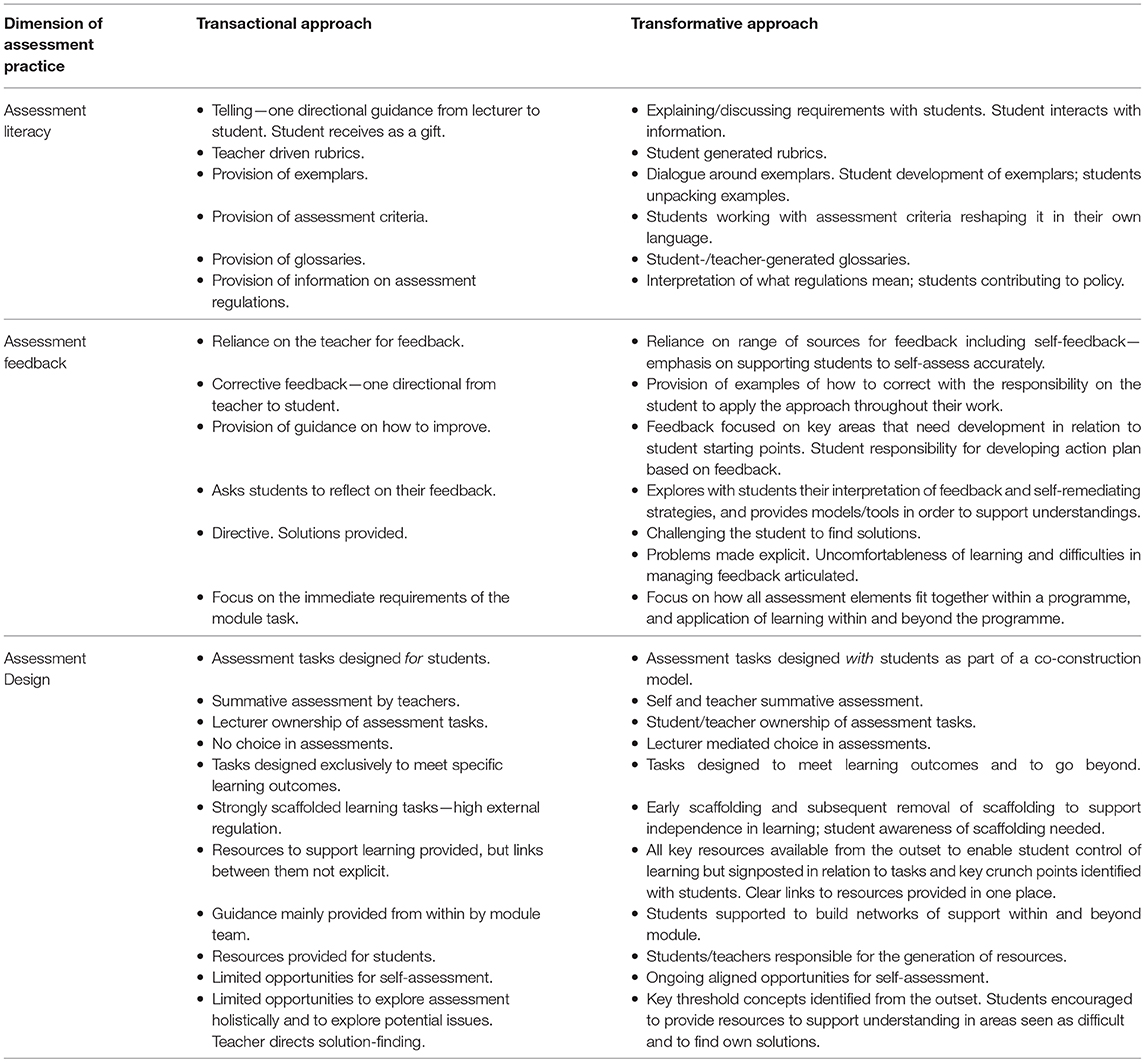

Evans' Assessment Tool (EAT) (Evans, 2016) is pertinent to discussions of transparency and inclusivity in assessment practices. Based on a comprehensive synthesis of the assessment feedback literature in higher education (Evans, 2013), the EAT Framework was developed to provide research-informed guidance at student, teacher, program, and institution level across three core dimensions of assessment practice: Assessment literacy, assessment feedback, and assessment design. The EAT Framework promotes a transformative approach to learning through enactment of its underpinning principles that promote student ownership and autonomy in learning as part of a self-regulated approach to learning. The framework emphasizes the development of student self-regulation, encompassing metacognitive, cognitive, and affective elements (Vermunt and Verloop, 1999). Conceptions of learning impact teaching and learning (Pedrosa-de-Jesus and da Silva Lopes, 2011), and especially the delivery and interpretation of assessment guidance. Being explicit about assessment, and how this is understood, will depend very much on whether one has a transactional or transformative conception of learning within a specific context; the former seeing learning as acquiring, gifting, acting on, and the latter seeing learning as focusing on abstraction of ideas, ownership, and adaptation of ideas to support understanding and application of learning (Säljö, 1979; Marton et al., 1993). Table 1, drawing on the core dimensions underpinning the EAT Framework, highlights the importance of student engagement in all decisions around assessment practices as part of developing agency, ownership, and importantly, “knower-ship” of the requirements of the discipline (Evans, 2018).

Table 1. Evans (2018) Transformative approaches to assessment practices using the EAT Framework compared to transactional approaches.

In the EAT Framework, the importance of being explicit in relation to higher education academic assessment practices is made within the context of promoting student self-regulation and independence in learning (e.g., consideration of the requirements of tasks and how they are assessed; the roles of all those involved in the assessment process, approaches used and tools available; and in addressing self-management of assessment through open dialogue about what is problematic and uncomfortable in learning). In this context, the moderators (individual and environmental) impacting student access to learning are paramount. What is seen as explicit to some, will not be to others, given learners' and teachers' similar and different frames of reference, experiences, and prior knowledge to mention just a few of the variables concerned in this complex equation. Table 1 illustrates how conceptions of learning impact dimensions of the assessment process using the EAT Framework, but also noting the importance of the interaction of context and the demands of the task where in certain circumstances, a transactional approach may be the most appropriate. This suggests the need for a flexible approach which acknowledges the need to “[abandon] the rigid explicit instruction versus minimal guidance dichotomy and [replace] it with a more flexible approach” (Kalyuga and Singh, 2016, p. 833) taking into account the requirements of the task, while being attuned to the needs of students (at the group and individual level). We will now discuss transactional approaches to being transparent with assessment practices, highlighting situations in which these approaches could risk spoon-feeding students.

At Risk of Spoon-Feeding? A Transactional Approach to Transparency in Assessment Practices

Transparency in assessment can lead to learner instrumentalism and students having an increased dependence on teachers, since it may be interpreted in a transactional way that sees assessment as something done to rather than with students (i.e., providing coaching, reading drafts, multiple opportunities for practice, etc.) (Torrance, 2007), with students taking very little ownership of the process. Sadler (2007) notes how criteria have the effect of breaking down assessments into “pea-sized bits to be swallowed one at a time” (p. 390), and that coaching has been utilized as a way to get students to address outcomes rather than actually learn. In this sense, explicit criteria and learning objectives run contrary to the spirit of higher education: “Many people learned many things long before the language of ‘learning goals’ was invented.” (Torrance, 2012, p. 331). From a student perspective, those who favor and/or have been inducted into transactional approaches to learning where external regulation of learning has been high, may want and need explicit guidance, whereas those more used to self-regulating their own learning, may value and also request explicit guidance to a lesser extent (Bell et al., 2013). In such contexts, a vicious circle can be set up where for some groups of students, the provision of more and more guidance may not ever be enough. For example, those with lower levels of self-regulation may be highly dependent on feedback (Çakir et al., 2016), but they may also be less able to use it well.

However, if students are not aware of the standards required of them, misunderstandings about “what constitutes good” can occur (Gibbs and Simpson, 2004). These misunderstandings will then require additional support from teachers to clarify the unclear expectations, which diverts attention away from actual learning and has the potential to disadvantage some student groups, as identified earlier. For example, where an assessment brief3 lacks clarity, the normative expectation held by teachers is that their students discuss with each other the requirements of the assessment. There are also situations (mostly those that require creative and original contributions) in which teachers need to draw on their tacit knowledge of what constitutes quality in that domain, so they are not able to explicitly state all of the criteria upfront and thus criteria may remain “fuzzy” to students (Sadler, 1987, 1989). Explicit criteria and learning outcomes alone may therefore not be able to convey teachers' tacit knowledge (O'Donovan et al., 2004), so students may be dependent on the teacher until they have enough understanding of how to interpret and access this knowledge (Sadler, 1989). There is clearly an argument for allowing teachers the flexibility to make qualitative human judgments, yet we argue that assessments requiring additional engagement between students and their teachers, or indeed between students themselves, to clarify expectations and requirements, are not innately inclusive. This culture is likely to further create exclusivity in students' opportunities to access assessment guidance; not all students will understand the manner in which this can adequately be obtained, particularly students from non-traditional backgrounds who are less willing to seek advice and guidance (Francis, 2008).

For many commentators, the riposte to the issue of differential attainment centers around the concept of the inclusive curriculum (Berry and Loke, 2011; Singh, 2011; Stevenson, 2012). An inclusive curriculum in higher education is one designed and delivered to engage students in learning that is accessible, relevant and meaningful to students from a wide range of backgrounds (Hockings, 2010). Following this logic, inclusive assessment should be accessible, applicable, expressive and clearly communicated. The principles of inclusive assessment have been expressed through the need to offer a varied diet of assessment types; the argument here being that a diverse “mix” of assessment methods will ensure that students with certain skills are not disadvantaged by specific forms of assessment. However, while giving choice in assessment method can have a positive effect on students who have clear understandings of their strengths and weaknesses by empowering them and allowing them to take responsibility for their learning, choice can also act to disempower and overwhelm students. Furthermore, an overemphasis on choice for choice's sake takes away from careful consideration of what the most appropriate assessment tasks are to enable a student to best meet required learning outcomes. We argue that the most inclusive assessment practices are ones that support and consciously scaffold students' learning through the underpinning of good assessment design.

Early assessment tasks may need to be more strongly scaffolded than later tasks, for example, in the provision of detailed explicit assessment criteria, to ensure equality of opportunity. However, if there is no gradual removal of this scaffolding as students gain more experience, this runs the risk of spoon-feeding, and increasing student dependence rather than independence in learning. Spoon-feeding in education can be defined as the process of teachers directly telling students everything they need to know about the requirements of a specific task, thus requiring little independent thought on their part (Smith, 2008). Epistemologically, spoon-feeding could be viewed as stemming from a representational model in which teachers merely transmit knowledge to passive students (Raelin, 2009) who have been socialized into a culture of dependence on them (Dehler and Welsh, 2014). “A complaint I hear from [university teachers] is that, undergraduate students require ‘spoon-feeding’ …. They say that their students demand it, and feel that they must unwillingly oblige. The metaphor of spoon-feeding doesn't match their idea of what a teacher should do, or how students should be going about their learning. They complain that students just want to be told exactly what to do, the facts, the right answers, instead of thinking things through for themselves.” (Smith, 2008, p. 715).

In the context of assessment, spoon-feeding may involve explicitly telling students what they need to do for an assignment, and how to meet the assessment criteria, without leaving it up to them to ascertain this for themselves. Addressing task criteria in the absence of understanding the domain being assessed has been termed by Torrance (2007) as “criteria compliance” (p. 282). Some students may use explicit criteria to focus on exactly what needs to be done to reach a desired level of achievement, rather than actually learning material fully (Panadero and Jonsson, 2013). Students' and teachers' conceptions of learning play a role in this; if teachers simply supply assessment requirements to students in a transactional manner, so they can passively “check boxes,” it is unlikely that students will engage with the criteria in a way that will develop their learning and self-regulation.

Nonetheless, explicit assessment criteria can directly pave the way for self-regulation to occur. Evidence has shown that explicit criteria have a positive effect on all phases of the self-regulation process4 (Panadero and Romero, 2014). For example, criterion-referencing5 is a common characteristic of self-assessment6 (Andrade and Du, 2007), which can be seen as a form of self-feedback (Andrade and Du, 2007; Winstone et al., 2017) encompassing the self-regulatory skills of self-monitoring and self-evaluation (Panadero et al., 2017). Self-assessment can foster self-efficacy, motivation to learn, and in turn, superior performance (Schunk, 2003; Andrade and Valtcheva, 2009). One way to facilitate self-assessment is through the use of rubrics7 (Panadero and Romero, 2014). A rubric, by definition, needs to make use of explicit assessment criteria (Jones et al., 2017) and Popham (1997) notes how a set of evaluative criteria is the most important aspect of a rubric, because mastery over these criteria will eventually result in skill mastery. The transparency provided by rubrics lays the groundwork for feedback to be interpreted; students' expectations are clarified, their attention is more closely focused on what their assessments require of them, they gain greater perceived control and confidence about their assessments, and their anxiety about completing the assessment is reduced (Andrade and Du, 2005; Andrade and Valtcheva, 2009; Panadero and Jonsson, 2013; Jonsson, 2014). Self-assessment affords students the opportunity to receive feedback that they are likely to perceive as low- or no-stakes when compared to teacher feedback (Chen et al., 2017). Furthermore, Panadero et al. (2013) found that rubrics reduced students' use of negative self-regulatory actions (i.e., self-regulatory approaches that are motivated by a desire to endorse performance avoidance goals, such as trying to avoid failing). Thus, a clear understanding of explicit standards and criteria serves as a crucial prerequisite to engaging in activities that enhance self-regulation (Andrade and Valtcheva, 2009).

However, the presence of explicit criteria alone does not mean they will automatically be used by students to self-regulate. Through focus group discussions with students, Andrade and Du (2007) reported evidence of tensions between what students thought was required of them in their self-assessment, and teachers' actual expectations of their work. For example, one student espoused that self-assessment was really just assessing what the teacher wanted, since they were the ones who set the assessment criteria. If students only use self-assessment to determine how to please the teacher and not internalize standards, it is hard to see how self-assessment might foster autonomy in students' future approaches to assessment. Similarly, Handley and Williams (2011) found that students did not understand how exemplar work related to explicit assessment criteria unless teachers directly showed them how this work mapped onto the criteria. Since rubrics make clear to students how their work will be evaluated and graded, there is a perceived fairness to using them (Reddy and Andrade, 2010), which is likely why students find them to be desirable, even in the absence of understanding the meaning of the criteria or how to apply them (Jonsson, 2014). A corollary of this is that students need to have explicit criteria in order to self-assess, but the manner in which these criteria are established can be done in a transactional or transformative way. For example, Fraile et al. (2017) claimed that involving students in the co-creation of criteria can counter any notion that self-assessment using rubrics could hinder their autonomy. Therefore, in order to avoid spoon-feeding, teachers should consider moving beyond the transactional approach of simply providing students with explicit criteria. A transformative approach acknowledges the roles of both teachers and students in assessment, which maximizes opportunities for enhancing students' self-regulatory capacities. Therefore, we need to carefully consider how we use assessment tools to support student independence rather than dependence in learning so that students take charge of these tools, make them their own, and use them appropriately. In doing so, students are able to demonstrate understanding of the requirements of learning.

Beyond Spoon-Feeding: A Transformative Approach to Transparency in Assessment Practices

Developing students' assessment literacies is one of the most effective ways to address differential attainment and improve students' learning (Price et al., 2012). Providing explicit assessment criteria and rubrics is important, but there is also an unequivocal requirement to explore the assessment with students in timetabled classroom sessions to ensure that students get the opportunity to speak to their teacher(s) and their peers to clarify misconceptions and solidify expectations (Bloxham and West, 2004). Classroom interventions where students can unpick assessment criteria and rubrics, then rewrite them in their own words, are particularly successful for students who are less confident to approach teachers in their office hours or after class. These interventions are also important for the ever-increasing numbers of students who commute to university (Thomas and Jones, 2017), and for those students whose face-to-face engagement with their peers and teachers may be more limited. Additional strategies include involving students in assessing previous work and articulating why they received the mark that they did, and peer marking formative work. Taras (2001), drawing on Sadler's work, carried out an innovative intervention in which students had the opportunity to propose their own criteria before comparing these to the actual criteria that had been set. Students' work was then returned without a grade and they needed to self-assess their work against agreed criteria based on the feedback they had received. Teachers believed these approaches allowed students who failed to understand why, and students felt that it made them more aware of what their assessment requirements actually were. Similarly, Evans and Waring (2011) suggested that students' engagement with assessment tasks could be deeper and more independent where clear assessment criteria had been determined through dialogue between students and teachers. They found that, during initial teacher education, student teachers valued clarity in assessment requirements, because it allowed them to plan their work effectively and complete it under tight time constraints. The important aspect here is shared understandings between teachers and students of what criteria mean within the specific context of a task. As Table 1 shows, a transformative approach emphasizes elements of practice that give students ownership over the assessment process; assessment is something done with rather than to students.

The provision of explicit guidance is aligned to Vygotskian notions of the zone of proximal development (ZPD) (Vygotsky, 1978), involving learning support from a knowledgeable “other” in order to make progress; this “other” could include peers, friends, networks, media, internet, journals, etc. The main issue with the ZPD is how to take learning to another level; as what and who can support the achievement of this are critical. Using the EAT Framework, instruction is centered on supporting students to be more proactive in attaining this support for themselves, but this does not preclude the role of the teacher in this endeavor (see also Nash and Winstone, 2017). A principal aim of “being explicit” is to enable students to focus on the elements of learning that are most important, rather than becoming embedded in the minutiae. The level of scaffolding is very much dependent on students' individual differences, timing (i.e., the stage of development of the learner within the learning process, such as novice or expert, Neubrand et al., 2016), the nature of the task (Arnold et al., 2014), and alignment of the level of complexity of information with the expertise of the learner (Vogel-Walcutt et al., 2011). From a pedagogical perspective, getting the level of scaffolding correct is crucial; this also includes the removal/fading of such support in order to support learners to be better able to transfer abilities from one context to another (Fang et al., 2016; Yuriev et al., 2017). We know that too much scaffolding can lead to student dependence rather than independence in learning (Koopman et al., 2011). Within learning contexts, there needs to be sufficient challenge (constructive friction) to support learning as opposed to destructive friction (where the learning context is too overwhelming) (Silén and Uhlin, 2008). Furthermore, as noted by Blasco (2015), some disruption or level of discomfort is often needed in order for students to be able to use explicit guidance, experiment, and then be able to integrate concepts and ideas into their own knowledge structures in order to be able to use within their own contexts.

A key part of scaffolding is supporting student access to information, networks and resources; fundamental to this is an understanding that individuals process information in different ways (Kozhevnikov et al., 2014). How information is presented impacts an individual's cognitive and emotional regulation in terms of the impact it has on their cognitive load (van Merriënboer and Sweller, 2005), which is also affected by the emotional meanings attached to specific verbal and visual representations. Cognitive load theory (CLT) is based on the assumption that our working memory capacity (i.e., our ability to temporally hold, while concurrently processing, information) is limited (Howard-Jones, 2010), and we therefore need to consider how we can either increase our working memory capacity, and/or reduce load to facilitate student access to information and subsequent recall. Key pedagogical lessons are the need to ensure information is presented in the most appropriate way for the requirements of the task and that any potentially distracting information is removed. Presenting information in visual and verbal forms aligned to visual and verbal processing systems drawing on dual coding theory has also been found to be successful in enhancing memory (Paivio, 2006). CLT especially reminds us of the importance of not overloading students with information at a time when they may not be in a position to process it (e.g., overloading with assessment information at the start of a module when this will not be a priority in relation to managing more immediate tasks).

The need for being explicit in clarifying students' “understanding of good” is a necessity, in that if we do not have a clear idea of what we are aiming for, it is hard to get there, albeit not impossible (Ramaprasad, 1983; Sadler, 2010). Evans (2016), in her pragmatic articulation of the assessment literature and extensive work in higher education practice using the EAT Framework as part of “feedback exchange” (Evans, 2013), argues for the importance of shared understandings between lecturers and students about not only “what constitutes good,” but about conceptions of learning in the first place, as this underpins how the notion of being explicit is enacted. The notion of feedback exchange is critical as part of this equation, as it extends the dialogue beyond the immediate teacher-student relationship to consider all the available information that students can access from a range of sources. The critical issue is with assessment design and training; providing affordances and supporting students in being able to maximize support from a range of sources within and beyond the immediate learning environment is imperative (Evans, 2013). The formative assessment literature is also germane to discussions about the importance of transparent and mutual student-teacher communications (Scott et al., 2014) in terms of ensuring that the two parties share common understandings about the nature of assessment tasks, what the learning process entails, and how evidence of learning is being assessed. Black and Wiliam (1998) initially emphasized that one of the key facets of formative assessment involved teachers sharing success criteria with their students. However, subsequent elucidation of the strategies involved in formative assessment now highlights the shared student and teacher roles in this process; alongside teachers having the responsibility to clarify criteria, students also have the responsibility to understand these criteria (Black and Wiliam, 2009). The main aim of formative assessment is now seen to be the development of self-regulation (Panadero et al., 2018). Thus, changing the goals of formative assessment practices can facilitate a move from transactional to transformative approaches.

Whether explicit guidance on assessment criteria and the assessment process gives students entry to the nature of knowledge within a discipline and its requirements is debatable. In trying to be explicit with a transformative approach, we are aiming to improve students' “knower-ship” of a subject or context(s), but this takes interaction between disciplinary insiders and students to come to shared understandings of what disciplines want their students to become, to know, and how they want students to construct knowledge (van Heerden et al., 2017). Richards and Pilcher (2014) highlight the importance of shared negotiation of meanings as part of teacher-student dialogue in their promotion of an “anti-glossary” approach. They argue that all terms are loaded (disciplinary, cultural, temporal and spatial inferences) and have different meanings for different actors, and for the same actors in different contexts, and over time; therefore, in order for a glossary of key terms to be usable, it does need to be deconstructed and reformulated through the medium of dialogue. Where teachers hold their own tacit knowledge of a domain that cannot easily be articulated as explicit assessment criteria, discussions between teachers and students about explicit criteria and standards can lead to the student forming their own tacit understanding of quality judgments (Yucel et al., 2014). Attention needs to be focused on making the implicit explicit (transparency in all higher education processes and disciplinary norms), and in attending to student dispositions (McCune and Entwistle, 2011), so that they are in a position to make the most of affordances within the learning environment. Going beyond the written to ensuring dialogic approaches to support shared understandings of what is required, is also highlighted by Papadopoulos et al. (2013) in their work with students on techniques in assessment to support students by being explicit, and also in Carless and Chan's (2017) work on the dialogic use of exemplars by teachers with students.

Conclusions

A key aim of higher education has to be to support learners to become more independent in their learning; ensuring them access to learning through being explicit is essential to this endeavor. The EAT Framework provides one example where, through a holistic approach, all aspects of assessment practice (promotion of assessment literacy, assessment feedback, and assessment design) are underpinned by the need to support students in managing learning for themselves. In this article, we have discussed the different ways in which explicit standards, criteria, tools, and processes can lead to differential impacts on students, with much depending on how “explicit” is enacted and received. However, we need to be mindful of individual differences in learners' contexts; we may endeavor to have all students and teachers working at a deeper and more transformative level, but this may not always be appropriate, so a flexible approach should be taken. We argue that a transactional approach to the use of explicit assessment criteria may run the risk of spoon-feeding students, so the ultimate goal of assessment in higher education should be to move to a transformative approach, striving for shared understandings between teachers and students of assessment requirements. Thus, the implications and recommendations of this article are also shared between teachers and students. If teachers strongly scaffold early tasks in an effort to be more inclusive, they need to have clear plans for how and when to fade this scaffolding once there is an expectation that students should make more of their own judgments; clarifying role expectations from the outset is a key part of this.

Interventions that give students opportunities to discuss and work with criteria are more likely to be effective in developing students' self-regulation than the mere provision of criteria alone (e.g., use of rubrics, deconstruction of assessment criteria, etc.). Engaging students in all decisions around assessment practices allows them to develop an understanding of what constitutes quality within their discipline, so students can become better equipped to self-manage their own learning; this emphasizes the importance of training in assessment for staff and students.

Implementing “explicit” in a robust way, therefore, requires learners and teachers to develop shared conceptions of learning that bring to attention what it is to learn in a meaningful way within a given context as part of a joint endeavor. Teachers' timetabled classroom sessions should give all students equal opportunities to develop their own understanding of explicit assessment criteria. As part of this, students need to be carefully inducted into their responsibility within assessment if they are to become more self-regulatory in their approach to assessments within and beyond a specific context (Evans, 2013; Nash and Winstone, 2017). The provision of explicit assessment criteria should be seen as the starting point to developing their own understanding of how to address these criteria. The fundamental point here, as advocated in the EAT Framework, is that if we see students as co-constructors of the curriculum, there is no reason why, if they are given appropriate training in assessment design, they cannot develop and design criteria for themselves. If this is achieved, a transformative approach to transparency in assessment is far from spoon-feeding.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the preparation, writing and revisions for this article.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Office for Students (OfS), England, and University of Southampton, University of Surrey, and Kingston University, through the Maximizing Student Success through the Development of Self-Regulation project award led by CE (grant number L16).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. ^For the sake of brevity and consistency, the term ‘teacher’ has been used throughout this article to refer to all types of teaching staff in higher education (i.e., educators, academics, lecturers, tutors, professors, etc.).

2. ^Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) is the terminology usually used in the UK to refer to individuals from a non-white background.

3. ^An assessment brief is a document that states the purpose of an assessment and provides a clear explanation of what is expected of students (Gilbert and Maguire, 2014).

4. ^Zimmerman's 2002 model of self-regulated learning proposes that there are three phases encompassing the following: a forethought phase, which occurs before learning and involves planning and goal setting; a performance phase, which takes place during learning and involves self-monitoring, through which students track their progress toward goals; and a self-reflection phase, which happens after learning and involves self-evaluation in which students judge their performance against a set of standards.

5. ^Criterion-referencing involves the use of clear assessment criteria to determine whether specific learning outcomes have been met (Torrance, 2007).

6. ^Self-assessment is the act of posing questions to oneself in order to make judgments about whether certain criteria and standards are being met (Boud, 1995b).

7. ^Rubrics are written documents that communicate the criteria of an assessment and the levels of quality expected (Andrade, 2000).

References

Andrade, H., and Du, Y. (2005). Student perspectives on rubric-referenced assessment. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 10, 1–11.

Andrade, H., and Du, Y. (2007). Student responses to criteria referenced self-assessment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 32, 159–181. doi: 10.1080/02602930600801928

Andrade, H., and Valtcheva, A. (2009). Promoting learning and achievement through self-assessment. Theory Pract. 48, 12–19. doi: 10.1080/00405840802577544

Arnold, J. C., Kremer, K., and Mayer, J. (2014). Understanding students' experiments—What kind of support do they need in inquiry tasks? Int. J. Sci. Educ. 36, 2719–2749. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2014.930209

Balloo, K. (2017). In-depth profiles of the expectations of undergraduate students commencing university: A Q methodological analysis. Stud. High. Educ. 1–12. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2017.1320373

Balloo, K., Pauli, R., and Worrell, M. (2017). Undergraduates' personal circumstances, expectations and reasons for attending university. Stud. High. Educ. 42, 1373–1384. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2015.1099623

Bell, A., Mladenovic, R., and Price, M. (2013). Students' perceptions of the usefulness of marking guides, grade descriptors and annotated exemplars. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 38, 769–788. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2012.714738

Berry, J., and Loke, G. (2011). Improving the Degree Attainment of Black and Minority Ethnic Students. York: Equality Challenge Unit (ECU)/Higher Education Academy (HEA). Available online at: http://www.ecu.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/external/improving-degree-attainment-bme.pdf

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 5, 7–74. doi: 10.1080/0969595980050102

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 21, 5–31. doi: 10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5

Blasco, M. (2015). Making the tacit explicit: rethinking culturally inclusive pedagogy in international student academic adaptation. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 23, 85–106. doi: 10.1080/14681366.2014.922120

Bloxham, S., and West, A. (2004). Understanding the rules of the game: Marking peer assessment as a medium for developing students' conceptions of assessment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 29, 721–733. doi: 10.1080/0260293042000227254

Boud, D. (1995a). “Assessment and learning: contradictory or complementary?,” in Assessment for Learning in Higher Education, ed. P. Knight (London: Kogan Page), 35–48.

Boud, D. (2000). Sustainable assessment: rethinking assessment for the learning society. Stud. Contin. Educ. 22, 151–167. doi: 10.1080/713695728

Boud, D., and Associates (2010). Assessment 2020: Seven Propositions for Assessment Reform in Higher Education. Sydney, NSW: Australian Learning and Teaching Council.

Boud, D., and Soler, R. (2016). Sustainable assessment revisited. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 41, 400–413. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1018133

Broadbent, J., Panadero, E., and Boud, D. (2018). Implementing summative assessment with a formative flavour: a case study in a large class. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 43, 307–322. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2017.1343455

Broadfoot, P., Daugherty, R., Gardner, J., Gipps, C., Harlen, W., James, M., et al. (1999). Assessment for Learning: Beyond the Black Box. Cambridge: Nuffield Foundation and University of Cambridge. Available online at: http://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/sites/default/files/files/beyond_blackbox.pdf

Cahalan, M., Perna, L. W., Yamashita, M., Ruiz, R., and Franklin, K. (2017). Indicators of Higher Education Equity in the United States: 2017 Trend Report. Washington, DC: Pell Institute for the Study of Higher Education, Council for Education Opportunity (COE) and Alliance for Higher Education and Democracy (AHEAD) of the University of Pennsylvania. Available online at: http://pellinstitute.org/downloads/publications-Indicators_of_Higher_Education_Equity_in_the_US_2017_Historical_Trend_Report.pdf

Çakir, R., Korkmaz, Ö., Bacanak, A., and Arslan, Ö. (2016). An exploration of the relationship between students' preferences for formative feedback and self-regulated learning skills. Malaysian Online J. Educ. Sci. 4, 14–30.

Carless, D. (2015). Exploring learning-oriented assessment processes. High. Educ. 69, 963–976. doi: 10.1007/s10734-014-9816-z

Carless, D., and Chan, K. K. H. (2017). Managing dialogic use of exemplars. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 42, 930–941. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2016.1211246

Chen, F., Lui, A. M., Andrade, H., Valle, C., and Mir, H. (2017). Criteria-referenced formative assessment in the arts. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 29, 297–314. doi: 10.1007/s11092-017-9259-z

Choi, I., Lee, S. J., and Kang, J. (2009). Implementing a case-based e-learning environment in a lecture-oriented anaesthesiology class: do learning styles matter in complex problem solving over time? Br. J. Educ. Technol. 40, 933–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2008.00884.x

Dehler, G. E., and Welsh, M. A. (2014). Against spoon-feeding. For learning. Reflections on students' claims to knowledge. J. Manag. Educ. 38, 875–893. doi: 10.1177/1052562913511436

ECU (2017). Equality in Higher Education: Students Statistical Report. London: Equality Challenge Unit (ECU). Available online at: http://hub.ecu.ac.uk/MembersArea/download-publication.aspx?fileName=Students_report_2017_November2017.pdf&login=Y

Entwistle, N. J., and Peterson, E. R. (2004). Conceptions of learning and knowledge in higher education: relationships with study behaviour and influences of learning environments. Int. J. Educ. Res. 41, 407–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2005.08.009

Evans, C. (2013). Making sense of assessment feedback in higher education. Rev. Educ. Res. 83, 70–120. doi: 10.3102/0034654312474350

Evans, C. (2016). Enhancing Assessment Feedback Practice in Higher Education: The EAT Framework. Southampton: University of Southampton. Available online at: https://eatframework.org.uk/

Evans, C. (2018). A Transformative Approach to Assessment Practices Using the EAT Framework Presentation. Small Scale Projects in Experimental Innovation. Catalyst A Funding Higher Education Funding Council for England (Southampton: HEFCE).

Evans, C., and Waring, M. (2011). Student teacher assessment feedback preferences: the influence of cognitive styles and gender. Learn. Individ. Differ. 21, 271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2010.11.011

Fang, S. C., Hsu, Y. S., and Hsu, W. H. (2016). Effects of explicit and implicit prompts on students' inquiry practices in computer-supported learning environments in high school earth science. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 38, 1699–1726. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2016.1213458

Fraile, J., Panadero, E., and Pardo, R. (2017). Co-creating rubrics: the effects on self-regulated learning, self-efficacy and performance of establishing assessment criteria with students. Stud. Educ. Eval. 53, 69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.03.003

Francis, R. A. (2008). An investigation into the receptivity of undergraduate students to assessment empowerment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 33, 547–557. doi: 10.1080/02602930701698991

Frederiksen, J. R., and Collins, A. (1989). A systems approach to educational testing. Educ. Res. 18, 27–32. doi: 10.3102/0013189X018009027

Gibbs, G., and Simpson, C. (2004). Conditions under which assessment supports students' learning. Learn. Teach. High. Educ. 1, 3–31. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2010.512631

Gilbert, F., and Maguire, G. (2014). Developing Academic Communication in Assignment Briefs to Enhance the Student Experience in Assessment. Available online at: https://assignmentbriefdesign.weebly.com/

Handley, K., and Williams, L. (2011). From copying to learning: using exemplars to engage students with assessment criteria and feedback. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 36, 95–108. doi: 10.1080/02602930903201669

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximizing Impact on Learning. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

Hattie, J., and Yates, G. (2014). Visible Learning and the Science of How We Learn. London: Routledge.

HEFCE (2015). Differences in Degree Outcomes: The Effect of Subject and Student Characteristics. Bristol: Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE). Available online at: http://www.hefce.ac.uk/media/HEFCE,2014/Content/Pubs/2015/201521/HEFCE2015_21.pdf

Hockings, C. (2010). Inclusive Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: a Synthesis of Research. York: Higher Education Academy (HEA) Available online at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/inclusive_teaching_and_learning_in_he_synthesis_200410_0.pdf

Jones, L., Allen, B., Dunn, P., and Brooker, L. (2017). Demystifying the rubric: a five-step pedagogy to improve student understanding and utilisation of marking criteria. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 36, 129–142. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2016.1177000

Jonsson, A. (2014). Rubrics as a way of providing transparency in assessment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 39, 840–852. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2013.875117

Kalyuga, S., and Singh, A.-M. (2016). Rethinking the boundaries of cognitive load theory in complex learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28, 831–852. doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9352-0

Koopman, M., Den Brok, P., Beijaard, D., and Teune, P. (2011). Learning processes of students in pre-vocational secondary education: relations between goal orientations, information processing strategies and development of conceptual knowledge. Learn. Individ. Differ. 21, 426–431. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2011.01.004

Kozhevnikov, M., Evans, C., and Kosslyn, S. M. (2014). Cognitive style as environmentally sensitive individual differences in cognition. Psychol. Sci. Public Interes. 15, 3–33. doi: 10.1177/1529100614525555

Marton, F., Dall'Alba, G., and Beaty, E. (1993). Conceptions of learning. Int. J. Educ. Res. 19, 277–300.

McCune, V., and Entwistle, N. (2011). Cultivating the disposition to understand in 21st century university education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 21, 303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2010.11.017

Nash, R. A., and Winstone, N. E. (2017). Responsibility-sharing in the giving and receiving of assessment feedback. Front. Psychol. 8:1519. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01519

Neubrand, C., Borzikowsky, C., and Harms, U. (2016). Adaptive prompts for learning evolution with worked examples-Highlighting the students between the “novices” and the “experts” in a classroom. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 11, 6774–6795.

Newbold, J. J., Mehta, S. S., and Forbus, P. (2010). A comparative study between non-traditional and traditional students in terms of their demographics, attitudes, behavior and educational performance. Int. J. Educ. Res. 5, 1–24.

Nicol, D., and MacFarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Stud. High. Educ. 31, 199–218. doi: 10.1080/03075070600572090

O'Donovan, B., Price, M., and Rust, C. (2004). Know what I mean? Enhancing student understanding of assessment standards and criteria. Teach. High. Educ. 9, 325–335. doi: 10.1080/1356251042000216642

Panadero, E., Alonso-Tapia, J., and Reche, E. (2013). Rubrics vs. self-assessment scripts effect on self-regulation, performance and self-efficacy in pre-service teachers. Stud. Educ. Eval. 39, 125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2013.04.001

Panadero, E., Andrade, H., and Brookhart, S. (2018). Fusing self-regulated learning and formative assessment: A roadmap of where we are, how we got here, and where we are going. Aust. Educ. Res. 45, 13–31. doi: 10.1007/s13384-018-0258-y

Panadero, E., and Jonsson, A. (2013). The use of scoring rubrics for formative assessment purposes revisited: a review. Educ. Res. Rev. 9, 129–144. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2013.01.002

Panadero, E., Jonsson, A., and Botella, J. (2017). Effects of self-assessment on self-regulated learning and self-efficacy: four meta-analyses. Educ. Res. Rev. 22, 74–98. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2017.08.004

Panadero, E., and Romero, M. (2014). To rubric or not to rubric? The effects of self-assessment on self-regulation, performance and self-efficacy. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 21, 133–148. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2013.877872

Papadopoulos, P. M., Demetriadis, S. N., and Weinberger, A. (2013). “Make it explicit!”: Improving collaboration through increase of script coercion. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 29, 383–398. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12014

Pedrosa-de-Jesus, M. H., and da Silva Lopes, B. (2011). The relationship between teaching and learning conceptions, preferred teaching approaches and questioning practices. Res. Pap. Educ. 26, 223–243. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2011.561980

Price, M., Rust, C., O'Donovan, B., Handley, K., and Bryant, R. (2012). Assessment Literacy: The Foundation for Improving Student Learning. Oxford: Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development.

Raelin, J. A. (2009). The practice turn-away: forty years of spoon-feeding in management education. Manag. Learn. 40, 401–410. doi: 10.1177/1350507609335850

Ramaprasad, A. (1983). On the definition of feedback. Behav. Sci. 28, 4–13. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830280103

Reay, D., Crozier, G., and Clayton, J. (2010). “Fitting in” or “standing out”: working-class students in UK higher education. Br. Educ. Res. J. 36, 107–124. doi: 10.1080/01411920902878925

Reddy, Y. M., and Andrade, H. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 35, 435–448. doi: 10.1080/02602930902862859

Richards, K., and Pilcher, N. (2014). Contextualising higher education assessment task words with an “anti -glossary” approach. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 27, 604–625. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2013.805443

Rogers-Shaw, C., Carr-Chellman, D. J., and Choi, J. (2017). Universal design for learning: guidelines for accessible online instruction. Adult Learn. 29:104515951773553. doi: 10.1177/1045159517735530

Sadler, D. R. (1987). Specifying and promulgating achievement standards. Oxford Rev. Educ. 13, 191–209.

Sadler, D. R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instr. Sci. 18, 119–144. doi: 10.1007/BF00117714

Sadler, D. R. (2005). Interpretations of criteria-based assessment and grading in higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 30, 175–194. doi: 10.1080/0260293042000264262

Sadler, D. R. (2007). Perils in the meticulous specification of goals and assessment criteria. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 14, 387–392. doi: 10.1080/09695940701592097

Sadler, D. R. (2010). Beyond feedback: developing student capability in complex appraisal. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 35, 535–550. doi: 10.1080/02602930903541015

Schunk, D. H. (2003). Self-efficacy for reading and writing: influence of modeling, goal setting, and self-evaluation. Read. Writ. Q. 19, 159–172. doi: 10.1080/10573560308219

Scott, D., Hughes, G., Evans, C., Burke, P. J., Walter, C., and Watson, D. (2014). Learning Transitions in Higher Education. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9781137322128

Shephard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educ. Res. 29, 4–14. doi: 10.3102/0013189X029007004

Silén, C., and Uhlin, L. (2008). Self-directed learning–a learning issue for students and faculty! Teach. High. Educ. 13, 461–475. doi: 10.1080/13562510802169756

Singh, G. (2011). Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) Students Participation in Higher Education: Improving Retention and Success–A Synthesis of Research Evidence. York: Higher Education Academy (HEA). Available online at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/bme_synthesis_final.pdf

Smith, H. (2008). Spoon-feeding: or how I learned to stop worrying and love the mess. Teach. High. Educ. 13, 715–718. doi: 10.1080/13562510802452616

Southall, J., Wason, H., and Avery, B. (2016). Non-traditional, commuter students and their transition to higher education-a synthesis of recent literature to enhance understanding of their needs. Student Engagem. Exp. J. 5, 1–15. doi: 10.7190/seej.v4i1.128

Stevenson, J. (2012). Black and Minority Ethnic Student Degree Retention and Attainment Introduction: The BME Degree Attainment Learning and Teaching Summit. York: Higher Education Academy (HEA). Available online at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/bme_summit_final_report.pdf

Swaffield, S. (2011). Getting to the heart of authentic assessment for learning. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 18, 433–449. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2011.582838

Taras, M. (2001). The use of tutor feedback and student self-assessment in summative assessment tasks: towards transparency for students and for tutors. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 26, 605–614. doi: 10.1080/02602930120093922

Thomas, L., and Jones, R. (2017). Student Engagement in the Context of Commuter Students. London: The Student Engagement Partnership (TSEP). Available online at: http://www.lizthomasassociates.co.uk/projects/2018/Commuter student engagement.pdf

Thomas, L., and Quinn, J. (2007). First Generation Entry into Higher Education. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Torrance, H. (2007). Assessment as learning? How the use of explicit learning objectives, assessment criteria and feedback in post-secondary education and training can come to dominate learning. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 14, 281–294. doi: 10.1080/09695940701591867

Torrance, H. (2012). Formative assessment at the crossroads: conformative, deformative and transformative assessment. Oxford Rev. Educ. 38, 323–342. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2012.689693

van Heerden, M., Clarence, S., and Bharuthram, S. (2017). What lies beneath: exploring the deeper purposes of feedback on student writing through considering disciplinary knowledge and knowers. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 42, 967–977. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2016.1212985

van Merriënboer, J. J. G., and Sweller, J. (2005). Cognitive load theory and complex learning: recent developments and future directions. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 17, 147–177. doi: 10.1007/s10648-005-3951-0

Vermunt, J. D., and Verloop, N. (1999). Congruence and friction between learning and teaching. Learn. Instr. 9, 257–280. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4752(98)00028-0

Vogel-Walcutt, J. J., Gebrim, J. B., Bowers, C., Carper, T. M., and Nicholson, D. (2011). Cognitive load theory vs. constructivist approaches: which best leads to efficient, deep learning? J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 27, 133–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2729.2010.00381.x

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Waring, M., and Evans, C. (2015). Understanding Pedagogy: Developing a Critical Approach to Teaching and Learning. Abingdon: Routledge.

Winstone, N. E., Nash, R. A., Parker, M., and Rowntree, J. (2017). Supporting learners' agentic engagement with feedback: A systematic review and a taxonomy of recipience processes. Educ. Psychol. 52, 17–37. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2016.1207538

Witkowsky, P., Mendez, S., Ogunbowo, O., Clayton, G., and Hernandez, N. (2016). Nontraditional student perceptions of collegiate inclusion. J. Contin. High. Educ. 64, 30–41. doi: 10.1080/07377363.2016.1130581

Yucel, R., Bird, F. L., Young, J., and Blanksby, T. (2014). The road to self-assessment: exemplar marking before peer review develops first-year students' capacity to judge the quality of a scientific report. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 39, 971–986. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2014.880400

Yuriev, E., Naidu, S., Schembri, L. S., and Short, J. L. (2017). Scaffolding the development of problem-solving skills in chemistry: guiding novice students out of dead ends and false starts. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 18, 486–504. doi: 10.1039/C7RP00009J

Keywords: assessment, feedback, criteria, higher education, inclusive curriculum, self-regulation, spoon-feeding, transparency

Citation: Balloo K, Evans C, Hughes A, Zhu X and Winstone N (2018) Transparency Isn't Spoon-Feeding: How a Transformative Approach to the Use of Explicit Assessment Criteria Can Support Student Self-Regulation. Front. Educ. 3:69. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00069

Received: 15 May 2018; Accepted: 09 August 2018;

Published: 03 September 2018.

Edited by:

Anders Jönsson, Kristianstad University, SwedenReviewed by:

Joanna Hong-Meng Tai, Deakin University, AustraliaCatarina Andersson, Umeå University, Sweden

Copyright © 2018 Balloo, Evans, Hughes, Zhu and Winstone. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kieran Balloo, ay5iYWxsb29Ac3VycmV5LmFjLnVr

Kieran Balloo

Kieran Balloo Carol Evans

Carol Evans Annie Hughes

Annie Hughes Xiaotong Zhu

Xiaotong Zhu Naomi Winstone

Naomi Winstone